Abstract

Background:

Stress cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) provides accurate assessment of both myocardial infarction (MI) and ischemia.

Objectives:

This study aimed to evaluate the incremental prognostic value of unrecognized myocardial infarction (UMI), detected during assessment of coronary artery disease (CAD) by stress CMR, beyond cardiac function and ischemia.

Methods:

In the multicenter SPINS (Stress CMR Perfusion Imaging in the United States) study, 2,349 consecutive patients (63 ± 11 years of age, 53% were male) with suspected CAD were assessed by stress CMR and followed over a median of 5.4 years. UMI was defined as the presence of late gadolinium enhancement consistent with MI in the absence of medical history of MI. This study investigated the association of UMI with all-cause mortality and nonfatal MI (death and/or MI), and major adverse cardiac events (MACE).

Results:

UMI was detected in 347 patients (14.8%) and clinically recognized myocardial infarction (RMI) in 358 patients (15.2%). Compared with patients with RMI, patients with UMI had a similar burden of cardiovascular risk factors, but significantly lower left ventricular ejection fraction (p < 0.001) and lower rates of guideline-directed medical therapies, including aspirin (p < 0.001), statin (p < 0.001), and beta-blockers (p = 0.002). During follow-up, 328 deaths and/or MIs and 528 MACE occurred. In univariate analysis, UMI and RMI were strongly associated with death and/or MI (UMI: hazard ratio [HR]: 2.15; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.63 to 2.83; p < 0.001; RMI: HR: 2.45; 95% CI: 1.89 to 3.18) and MACE. Compared with patients with RMI, patients with UMI presented an increased risk for heart failure hospitalization (UMI vs. RMI: HR: 2.60; 95% CI: 1.48 to 4.58; p < 0.001). In a multivariate model including ischemia and left ventricular ejection fraction, UMI and RMI maintained robust prognostic association with death and/or MI (UMI: HR: 1.82; 95% CI: 1.37 to 2.42; p < 0.001; RMI: HR: 1.54; 95% CI: 1.14 to 2.09) and MACE.

Conclusions:

In a multicenter cohort of patients with suspected CAD, presence of UMI or RMI portended an equally significant risk for death and/or MI, independently of the presence of ischemia. Compared with RMI patients, those with UMI were less likely to receive guideline-directed medical therapies and presented an increased risk for heart failure hospitalization that warrants further study. (Stress CMR Perfusion Imaging in the United States [SPINS]; NCT03192891).

Keywords: Coronary artery disease, Secondary prevention, Silent myocardial infarction, Stress cardiac magnetic resonance, Unrecognized myocardial infarction

Introduction

Approximately 9 million patients are annually evaluated in the United States for angina, the most prevalent manifestation of coronary artery disease (CAD). In addition to accurately identifying obstructive CAD (1,2), cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging has the unique ability to reliably identify even minute amounts (≥1 g) of subendocardial scar due to myocardial infarction (MI), more accurately than clinical history, electrocardiography (ECG), or other imaging modalities (3,4), thus making it a valuable tool for the detection of unrecognized (silent) myocardial infarction (UMI). Previous work has suggested that up to one-third of patients with suspected CAD has previously experienced a UMI (5,6), and those patients may represent a high-risk subgroup.

In the general population, UMI is associated with an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular (CV) death (7,8), MI (9), and heart failure (HF) hospitalization (10,11), at least comparable to that of recognized myocardial infarction (RMI) (12). However, the clinical characteristics, treatment, and long-term prognostic impact of UMI have not been well characterized in patients with suspected CAD, with current knowledge limited by inaccuracy of UMI detection by conventional methods, short follow-up duration, and single-center designs. Moreover, myocardial ischemia burden has been widely hypothesized to be the primary risk factor driving the unfavorable prognosis of patients with UMI (7, 8, 9, 10). However, no study has so far systematically examined whether UMI holds independent prognostic value beyond established prognosticators such as left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and myocardial ischemia in this clinical setting.

In this post hoc analysis of the multicenter SPINS (Stress CMR Perfusion Imaging in the United States) study, we sought to investigate in a cohort of consecutive patients with suspected CAD: 1) the clinical characteristics of patients with CMR-detected UMI; and 2) the long-term prognostic value of UMI for all-cause mortality and major adverse cardiac events (MACE), independently of established CV risk markers including myocardial function and ischemia.

Methods

Study population and design

The patient population and design of the retrospective, multicenter SPINS study of the SCMR (Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance) registry have been previously described (1). Inclusion criteria included: an age between 35 and 85 years; referral for evaluation of chest pain, dyspnea, abnormal ECG, or other clinical presentation that raised a suspicion of myocardial ischemia as determined by the treating clinician; and presence of ≥2 of the following coronary risk factors: age >50 years for men or >60 years for women; diabetes mellitus; hypertension; hypercholesterolemia; family history of premature CAD; body mass index ≥30 kg/m2; documented peripheral vascular disease; history of percutaneous coronary intervention or MI. Exclusion criteria included history of coronary artery bypass graft surgery, recent MI within 30 days preceding the index CMR study, severe-grade valvular heart disease, nonischemic cardiomyopathy with a LVEF <40%, infiltrative or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, constrictive pericarditis, active pregnancy, competing medical illnesses with expected survival <2 years, and known inability to participate in follow-up. Vasodilator stress included the use of intravenous infusion of adenosine, intravenous bolus of regadenoson, or dipyridamole.

Selection of enrolling centers and CMR methods

An enrolling center was required to have an active stress CMR imaging program ongoing for at least 10 years; contribute between 100 and 500 consecutive patients undergoing stress CMR between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2013, so that at least 4 years of clinical follow-up could be achieved at study conclusion; and have access to electronic medical records. Each center was also required to have all CMR scans interpreted by a Core Cardiology Training Statement level II/III reader, with at least 1 Core Cardiology Training Statement level III supervising reader. Enrolling centers must have performed CMR studies using either a 1.5-T or a 3-T scanner and pulse sequences for stress perfusion, cine, and late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) imaging of infarction. At each participating site, local institutional review board approval was obtained with a waiver of written informed consent. For quality assurance, each center randomly selected 10% of its CMR studies and submitted the images for blinded interpretation by the CMR core lab at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital to evaluate core lab versus center agreement.

Data collection and definition of UMI

Clinical variables included patient demographics and clinical characteristics at the time of the stress CMR. CMR variables included LV volumes and dimensions, stress perfusion and LGE using the American Heart Association 17-segment model. A stress perfusion defect was considered present if it was densest in the endocardium with a transmural gradient across the wall thickness, persisted beyond peak myocardial enhancement and for several R-R intervals, and conformed to a coronary arterial distribution. Inducible ischemia was defined as the presence of a stress perfusion defect, in absence of matching LGE, in ≥1 segment. RMI was defined by a history of MI corroborated by evidence on medical documentation. Site clinician investigators were instructed and trained to use all available clinical information including patient history, hospital and surveillance records, and imaging evidence in characterizing the timing and presentation of a MI. The adjudicating physician then established the absence or presence of MI history, based on the latest version of the universal definition of MI available at the time of enrollment. In keeping with previous studies (7,8), UMI was defined as absence of MI history on medical documentation, but presence of LGE involving the subendocardium in ≥1 segment in a coronary artery distribution thus conforming to an infarction pattern. A more stringent and specific definition of UMI by incorporating an ECG criterion of MI—assessed by presence of pathological Q waves in ≥2 contiguous leads—was also examined (8) in a supplemental analysis. Furthermore, ischemia and MI extent were assessed by the number of myocardial segments involved, based on the American Heart Association 17-segment model.

Study investigators were trained during the initiation period by group webinars and study documents on specific definitions of all key variables and all outcome variables and their standardized published definitions were posted on a web-based database. In the final 6 months of the study period, a data quality report was generated by the data-coordinating center in Boston and sent weekly to each site.

Study outcomes

All centers were instructed to systematically obtain follow-up data using the same rigorous approach, on all enrolled patients, for as long as possible and at least during 4 years after the index stress CMR. Clinical follow-up used both electronic medical records and direct patient contact with either a standardized checklist questionnaire or scripted telephone interview. Regardless of the results of the aforementioned follow-up procedures, the mortality status of all study participants was further verified by each site’s principal investigator via local death registries and the Social Security Death Index at the end of the study period.

The primary outcome was all-cause death or nonfatal MI during study follow-up. The secondary outcome was MACE defined by death, nonfatal MI, hospitalization for HF or unstable angina, and late (>6 months after the index CMR) unplanned coronary artery bypass graft surgery. For either study outcome, only the first event was counted when multiple events occurred in a subject. Successful follow-up was defined as achieving an assessment of all events for ≥4 years after the index CMR. For patients who discontinued follow-up or were lost to follow-up, follow-up was censored at the time of the last clinical contact. End of follow-up data collection and locking of database occurred on May 25, 2018.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical variables were compared using the chi-square test for categorical variables and Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, depending on the distribution. Cox proportional hazards were used to assess the association of UMI or RMI with outcomes. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated by plotting cumulative incidence of study outcomes by years of follow-up and compared using a log-rank test.

We constructed a multivariable clinical risk model with a stepwise forward Cox regression strategy, considering all covariates with <10% missing data and a p value of <0.10 on univariable screening. In a supplementary analysis, we constructed a second multivariable model including all the above-mentioned variables with the addition of aspirin, statin, and beta-blocker use. Furthermore, to exclude the possibility of any potential bias in patient follow-up beyond 4 years, all the above-mentioned statistical analyses were also performed within the 4-year time frame, censoring any subsequent events. Statistical analyses were performed with the use of SAS version 9.2, (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). A 2-tailed p value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Clinical and CMR characteristics in the study population

Clinical and CMR characteristics of the cohort are summarized in Table 1. Rates of RMI (15.2%) versus UMI (14.8%) were similar. Compared with patients with RMI, patients with UMI had similar burden of CV risk factors including age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, or family history of CAD. With respect to CMR parameters, patients with UMI presented with a significantly lower LVEF (p <0.001), a higher LV end-systolic volume index (p = 0.008) and more LV segments with LGE (p < 0.001). Rates of inducible ischemia were similar between the 2 groups (34.0% vs. 32.4%; p = 0.651).

TABLE 1.

Clinical and CMR Characteristics According to the Presence of MI

| Clinical Data | No MI (n = 1,644, 70.0%) |

UMI (n = 347, 14.8%) |

RMI (n = 358, 15.2%) |

p Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MI vs. no MI | UMI vs. RMI | ||||

| Age, yrs | 62.3 ± 11.3 | 62.9 ± 11.0 | 63.3 ± 11.4 | 0.097 | 0.778 |

| Female | 871 (53.0) | 112 (32.3) | 121 (33.8) | <0.001 | 0.668 |

| Hypertension | 1,248 (75.9) | 301 (86.7) | 294 (82.4) | <0.001 | 0.107 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 1,097 (66.9) | 251 (72.3) | 299 (83.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 431 (26.2) | 111 (32.0) | 122 (34.1) | 0.001 | 0.555 |

| Smoking | 498 (30.5) | 130 (37.9) | 129 (36.4) | 0.002 | 0.69 |

| Family history of CAD | 526 (33.1) | 116 (36.1) | 119 (35.4) | 0.232 | 0.847 |

| History of PCI | 205 (12.5) | 88 (25.4) | 245 (68.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| History of HF | 116 (7.1) | 75 (21.6) | 54 (15.1) | <0.001 | 0.026 |

| Medication | |||||

| Aspirin | 815 (49.8) | 219 (63.9) | 299 (84.0) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Statin | 906 (55.3) | 215 (62.3) | 294 (82.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Beta-blockers | 707 (43.2) | 218 (63.4) | 265 (74.2) | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| ACE inhibitors and/or ARBs | 760 (46.2) | 217 (62.5) | 224 (62.6) | <0.001 | 0.993 |

| Diuretics | 457 (30.0) | 137 (40.1) | 107 (30.0) | 0.001 | 0.005 |

| Stress CMR | |||||

| LVEF, % | 65.0 (57.4–71.0) | 55.7 (42.5–64.3) | 60.2 (48.1–68.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| RVEF, % | 57.0 (50.8–62.3) | 52.3 (42.1–60.7) | 57.3 (51.4–62.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| LVEDVi, ml/m2 | 60.9 (48.3–74.3) | 71.0 (58.5–93.5) | 69.4 (52.8–88.0) | <0.001 | 0.059 |

| LVESVi, ml/m2 | 20.8 (15.1–28.9) | 29.2 (20.6–50.1) | 27.0 (17.5–41.0) | <0.001 | 0.008 |

| Ischemia presence | 171 (10.4) | 118 (34.0) | 116 (32.4) | <0.001 | 0.651 |

| LGE presence | 0 (0.0) | 347 (100.0) | 225 (62.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| LGE segments | 0 (0–0) | 3 (1–5) | 2 (0–5) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Values are mean ± SD, n (%), or median (interquartile range) unless otherwise indicated. N = 2,349.

Abbreviations: ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker; CAD = coronary artery disease; CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance; HF = heart failure; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement; LVEDVi = left ventricular end-diastolic volume index; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESVi = left ventricular end-systolic volume index; MI = myocardial infarction; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; RMI = recognized myocardial infarction; RVEF = right ventricular ejection fraction; UMI = unrecognized myocardial infarction.

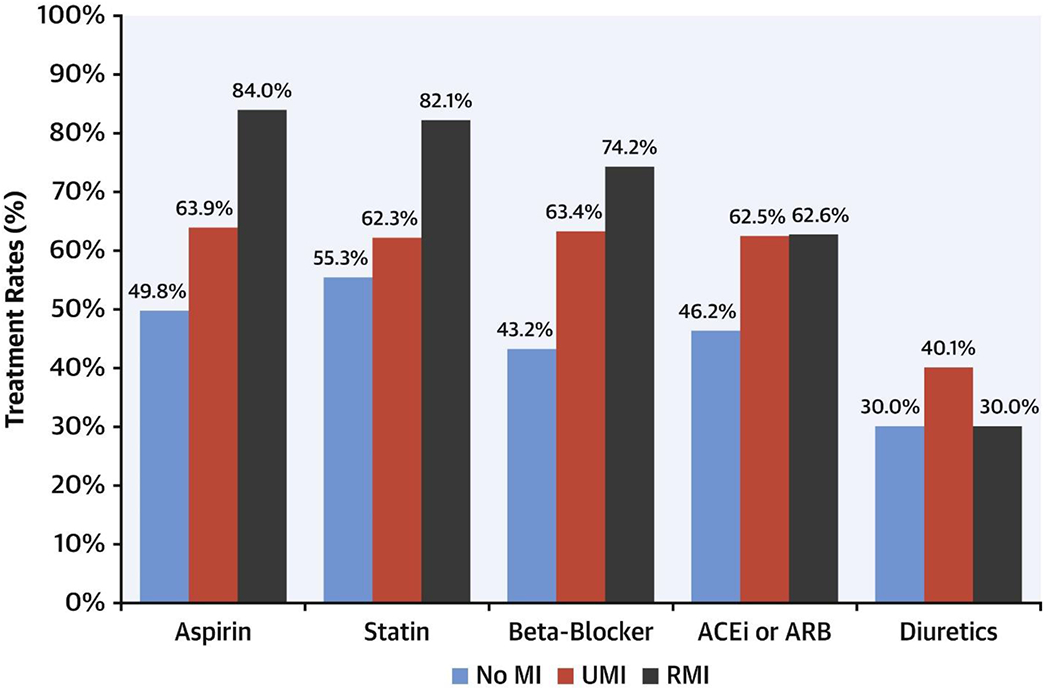

Figure 1 illustrates the use of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) at the time of the stress CMR. Compared with patients with RMI, patients with UMI were significantly less likely to be receiving aspirin (63% vs. 84%; p < 0.001) or statin treatment (62% vs. 82%; p < 0.001). Despite a lower LVEF, patients with UMI were also less likely to receive a beta-blocker (63% vs. 74%; p = 0.002), whereas angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and/or angiotensin receptor blocker treatment rates were similar. After excluding patients with documented CAD prior to the index CMR, only 55% and 52% of patients with UMI were receiving aspirin and statin treatment, respectively.

Figure 1.

Use of Cardiovascular Medications in the Study Population.

Treatment rates for aspirin, statin, beta-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) and/or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) and diuretics according to the presence or absence of myocardial infarction (MI)—unrecognized myocardial infarction (UMI) or recognized myocardial infarction (RMI). N = 2,349.

Univariate associations of UMI and RMI with outcomes

Successful follow-up of ≥4 years was achieved in 2,294 patients (97.7%), whereas median follow-up was 5.4 years (interquartile range: 4.6 to 6.8 years). We observed 328 deaths and/or MIs and 528 MACE until the end of follow-up, compared with 216 deaths and/or MIs and 379 MACE within the first 4 years.

The univariate associations of clinical and CMR characteristics with outcomes are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Presence of MI was significantly associated with death and/or MI and MACE, with no significant risk difference between UMI and RMI. Compared with absence of MI, presence of UMI or RMI was strongly associated with death and/or MI (UMI vs. no MI: hazard ratio [HR]: 2.15; 95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 1.63 to 2.83; RMI vs. no MI: HR: 2.45; 95% CI: 1.89 to 3.18; p < 0.001 for both) and MACE (Table 2, Supplemental Table 1). Compared with patients with no MI, patients with RMI without LGE (133 of 358 [37%]) presented a HR of 1.83 (95% CI: 1.20 to 2.81), p = 0.005 for death and/or MI and a HR of 2.05 (95% CI: 1.46 to 2.87), p < 0.001 for MACE (Supplemental Figure 1). HRs for every additional myocardial segment of UMI versus no MI and RMI versus no MI were 1.08 (95% CI: 1.05 to 1.11), p < 0.001 and 1.12 (95% CI: 1.08 to 1.16), p < 0.001 for death and/or MI, and 1.07 (95% CI: 1.04 to 1.10), p < 0.001 and 1.16 (95% CI: 1.12 to 1.19), p < 0.001 for MACE, respectively.

Table 2.

Univariate Associations of Clinical and CMR Characteristics With Death and/or MI and MACE

| Clinical Data | Death and/or MI | MACE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Age, per 5 yrs | 1.19 (1.13–1.25) | <0.001 | 1.10 (1.06–1.15) | <0.001 |

| Female | 0.74 (0.59–0.92) | 0.007 | 0.79 (0.66–0.94) | 0.007 |

| Hypertension | 1.31 (0.98–1.74) | 0.067 | 1.65 (1.29–2.10) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 0.85 (0.69–1.08) | 0.132 | 1.02 (0.85–1.24) | 0.804 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.45 (1.16–1.82) | 0.001 | 1.43 (1.20–1.72) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 1.46 (1.18–1.81) | 0.003 | 1.38 (1.16–1.65) | <0.001 |

| Family history of CAD | 0.83 (0.66–1.05) | 0.147 | 0.97 (0.81–1.17) | 0.776 |

| UMI vs. no MI | 2.15 (1.63–2.83) | <0.001 | 2.48 (2.00–3.06) | <0.001 |

| RMI vs. no MI | 2.45 (1.89–3.18) | <0.001 | 2.63 (2.14–3.25) | <0.001 |

| History of PCI | 1.55 (1.23–1.96) | <0.001 | 1.88 (1.57–2.26) | <0.001 |

| History of HF | 3.06 (2.36–3.97) | <0.001 | 2.57 (2.07–3.19) | <0.001 |

| Medications | ||||

| Aspirin | 1.32 (1.05–1.66) | 0.016 | 1.43 (1.20–1.72) | <0.001 |

| Statin | 1.11 (0.88–1.39) | 0.384 | 1.25 (1.05–1.50) | 0.015 |

| Beta-blockers | 1.37 (1.10–1.70) | 0.006 | 1.52 (1.27–1.81) | <0.001 |

| ACE inhibitors and/or ARBs | 1.21 (0.97–1.51) | 0.084 | 1.24 (1.05–1.48) | 0.014 |

| Diuretics | 1.42 (1.13–1.78) | 0.002 | 1.41 (1.18–1.69) | <0.001 |

| Stress CMR | ||||

| LVEF, per 5% | 0.89 (0.86–0.92) | <0.001 | 0.87 (0.85–0.90) | <0.001 |

| RVEF, per 5% | 0.92 (0.87–0.97) | 0.003 | 0.89 (0.85–0.93) | <0.001 |

| LVEDVi, per 10 ml/m2 | 1.11 (1.07–1.15) | <0.001 | 1.11 (1.08–1.14) | <0.001 |

| LVESVi, per 10 ml/m2 | 1.14 (1.10–1.17) | <0.001 | 1.14 (1.11–1.17) | <0.001 |

| Ischemia presence | 1.84 (1.43–2.35) | <0.001 | 2.42 (2.01–2.93) | <0.001 |

| LGE presence | 2.28 (1.82–2.84) | <0.001 | 2.50 (2.10–2.97) | <0.001 |

N = 2,349. Statistical analysis by Cox proportional hazards regression.

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; MACE = major adverse cardiac events; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Table 3.

Univariate Associations With Death and/or MI and MACE, According to the Presence of MI in the Entire Cohort and in Patients Without Ischemia on Stress CMR

| No MI | UMI | RMI | MI vs. no MI | UMI vs. RMI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Entire Cohort | (n = 1,644) | (n = 347) | (n = 358) | ||||

| Death and/or MI* | 170 (10.3) | 73 (21.0) | 85 (23.7) | 2.30 (1.85–2.86) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.64–1.21) | 0.43 |

| All-cause death† | 148 (9.0) | 61 (17.6) | 46 (12.8) | 1.72 (1.34–2.21) | <0.001 | 1.41 (0.96–2.08) | 0.077 |

| MI† | 24 (1.5) | 17 (4.9) | 46 (12.8) | 6.45 (4.02–10.3) | <0.001 | 0.39 (0.22–0.68) | <0.001 |

| MACE† | 268 (16.3) | 126 (36.3) | 134 (37.4) | 2.55 (2.15–3.03) | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.74–1.20) | 0.63 |

| CV death | 28 (1.7) | 26 (7.5) | 20 (5.6) | 3.95 (2.47–6.33) | <0.001 | 1.42 (0.79–2.54) | 0.24 |

| Hospitalization for HF | 49 (3.0) | 41 (11.8) | 18 (5.0) | 2.93 (2.00–4.30) | <0.001 | 2.60 (1.48–4.58) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalization for UA | 63 (3.8) | 27 (7.8) | 49 (13.7) | 3.02 (2.15–4.23) | <0.001 | 0.58 (0.36–0.93) | 0.023 |

| Late unplanned CABG | 19 (1.2) | 14 (4.0) | 18 (5.0) | 3.92 (2.21–6.93) | <0.001 | 0.78 (0.38–1.58) | 0.485 |

| VT and/or VF | 13 (0.8) | 6 (1.7) | 14 (3.9) | 3.66 (1.81–7.41) | <0.001 | 0.43 (0.16–1.14) | 0.081 |

|

| |||||||

| No ischemia on stress CMR | (n = 1,473) | (n = 229) | (n = 242) | ||||

| Death and/or MI* | 148 (10.1) | 42 (18.3) | 52 (21.5) | 2.11 (1.63–2.74) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.57–1.30) | 0.473 |

| All-cause death† | 133 (9.0) | 38 (16.6) | 32 (13.2) | 1.69 (1.26–2.26) | <0.001 | 1.32 (0.82–2.11) | 0.254 |

| MI† | 17 (1.1) | 7 (3.1) | 25 (10.3) | 6.30 (3.50–11.35) | <0.001 | 0.31 (0.13–0.71) | 0.003 |

| MACE† | 219 (14.9) | 73 (31.9) | 77 (31.8) | 2.36 (1.91–2.91) | <0.001 | 1.01 (0.73–1.40) | 0.95 |

| CV death | 24 (1.6) | 11 (4.8) | 14 (5.8) | 3.39 (1.94–5.94) | <0.001 | 0.89 (0.40–1.96) | 0.771 |

| Hospitalization for HF | 37 (2.5) | 24 (10.5) | 9 (3.7) | 2.89 (1.79–4.65) | <0.001 | 3.39 (1.52–7.54) | 0.002 |

| Hospitalization for UA | 46 (3.1) | 15 (6.6) | 25 (10.3) | 2.88 (1.88–4.40) | <0.001 | 0.64 (0.34–1.21) | 0.168 |

| Late unplanned CABG | 13 (0.9) | 5 (2.2) | 9 (3.7) | 2.97 (1.40–6.33) | 0.003 | 0.51 (0.16–1.65) | 0.252 |

| VT and/or VF | 11 (0.8) | 3 (1.3) | 8 (3.3) | 3.18 (1.37–7.38) | <0.007 | 0.39 (0.10–1.48) | 0.166 |

Values are n or n (%), unless otherwise indicated. N = 2,349; no ischemia on stress CMR, n = 1,944. HRs are unadjusted. Statistical analysis by log-rank test.

Only p values for the primary outcome are confirmatory.

There was no multiplicity adjustment for the testing of these outcomes.

These findings remained robust within the 4-year study time frame (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3), after exclusion of patients with UMI and pathological ECG Q waves (Supplemental Table 4), and in patients with and without documented CAD prior to the index CMR (Supplemental Table 4).

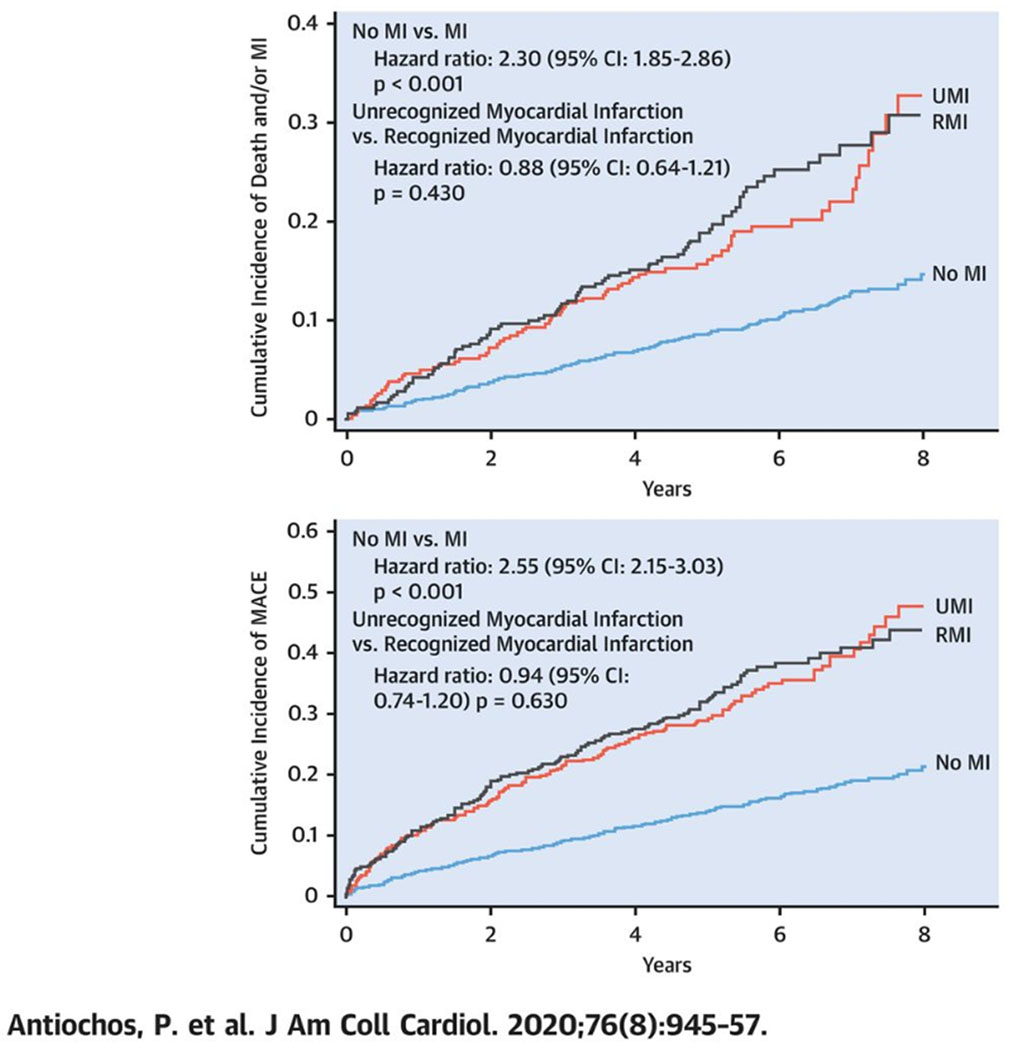

In Kaplan-Meier analysis, patients with MI (UMI or RMI) experienced a comparable, substantial decrease in event-free survival compared with those without any MI, both for death and/or MI (p < 0.001 for MI vs. no MI; p = 0.430 for UMI vs. RMI) and MACE (p < 0.001 for MI vs. no MI; p = 0.630 for UMI vs. RMI) (Central Illustration). Those findings remained robust within 4 years of follow-up (Supplemental Figure 2).

Central Illustration.

Time-to-Event Curves for Death and/or MI and MACE.

Time-to-event curves for death and/or myocardial infarction (MI) (top) and major adverse cardiac events (MACE) (bottom). Event-free survival for patients with recognized myocardial infarction (RMI), unrecognized myocardial infarction (UMI), and neither form of MI are shown in black, red, and blue respectively. Statistical analysis using log-rank test for “no MI versus MI” and “unrecognized MI versus recognized MI.” CI = confidence interval.

Multivariable associations of UMI and RMI with outcomes

Using a stepwise forward Cox regression strategy by considering all covariates with <10% missing data and a p value of <0.1 on univariable screening, we constructed a multivariate model including age, smoking, diabetes mellitus, LVEF, ischemia, and MI (RMI or UMI). In multivariate analysis, presence of MI was a significant predictor of both death and/or MI and MACE without significant difference between UMI versus RMI (UMI vs. RMI: HR: 0.84; 95% CI: 0.61 to 1.17; p = 0.307 for death and/or MI; HR: 0.86; 95% CI: 0.67 to 1.11; p=0.255 for MACE) (Table 4). Compared with absence of MI, RMI was a strong predictor for death and/or MI (RMI vs. no MI: HR: 1.54; 95% CI: 1.14 to 2.09; p < 0.001), similar to UMI (UMI vs. no MI: HR: 1.82; 95% CI: 1.37 to 2.42; p < 0.001) (Supplemental Table 5).

Table 4.

Multivariable Associations With Death and/or MI and MACE, According to the Presence of MI in the Entire Cohort and in Patients Without Ischemia on Stress CMR

| Death and/or MI | MACE | Death and/or MI | MACE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | ||

| Entire cohort | |||||||||

| MI vs. no MI | 1.69 (1.32–2.15) | <0.001 | 1.78 (1.46–2.16) | <0.001 | UMI vs. RMI | 0.84 (0.61–1.17) | 0.307 | 0.86 (0.67–1.11) | 0.255 |

| Age, per 5 yrs | 1.19 (1.13–1.26) | <0.001 | 1.12 (1.07–1.17) | <0.001 | Age, per 5 yrs | 1.10 (1.02–1.83) | 0.019 | 1.03 (0.97–1.10) | 0.302 |

| Diabetes | 1.45 (1.15–1.83) | 0.002 | 1.38 (1.15–1.67) | <0.001 | Diabetes | 1.31 (0.93–1.83) | 0.122 | 1.17 (0.89–1.53) | 0.253 |

| Smoking | 1.38 (1.09–1.75) | 0.007 | 1.32 (1.09–1.59) | 0.004 | Smoking | 1.39 (1.00–1.94) | 0.052 | 1.35 (1.04–1.75) | 0.027 |

| LVEF, per 5% | 0.92 (0.89–0.96) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.89–0.94) | <0.001 | LVEF, per 5% | 0.92 (0.88–0.97) | 0.002 | 0.93 (0.89–0.96) | <0.001 |

| Ischemia | 1.30 (0.99–1.70) | 0.062 | 1.66 (1.35–2.05) | <0.001 | Ischemia | 1.30 (0.92–1.84) | 0.131 | 1.53 (1.17–1.99) | 0.002 |

|

| |||||||||

| No ischemia on stress CMR | |||||||||

| MI vs. no MI | 1.69 (1.28–2.22) | <0.001 | 1.89 (1.51–2.36) | <0.001 | UMI vs. RMI | 0.83 (0.53–1.29) | 0.409 | 0.94 (0.67–1.33) | 0.738 |

| Age, per 5 yrs | 1.24 (1.16–1.32) | <0.001 | 1.16 (1.10–1.22) | <0.001 | Age, per 5 yrs | 1.14 (1.03–1.26) | 0.012 | 1.06 (0.98–1.14) | 0.152 |

| Diabetes | 1.61 (1.23–2.11) | 0.001 | 1.51 (1.21–1.89) | <0.001 | Diabetes | 1.27 (0.80–2.00) | 0.307 | 1.21 (0.84–1.74) | 0.303 |

| Smoking | 1.30 (0.98–1.72) | 0.065 | 1.35 (1.07–1.69) | 0.01 | Smoking | 1.34 (0.86–2.09) | 0.201 | 1.39 (0.98–1.98) | 0.064 |

| LVEF, per 5% | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) | 0.002 | 0.90 (0.87–0.94) | <0.001 | LVEF, per 5% | 0.93 (0.87–1.00) | 0.062 | 0.94 (0.89–0.99) | 0.03 |

We furthermore assessed the incremental prognostic value of UMI extent, adjusted for ischemic burden and age, smoking, diabetes mellitus, and LVEF. In our multivariate model, UMI extent maintained robust adjusted prognostic association with death and/or MI (HR: 1.07; 95% CI: 1.04 to 1.10; p < 0.001) and MACE (HR: 1.05; 95% CI: 1.02 to 1.08; p = 0.001), as did RMI extent (HR: 1.07; 95% CI: 1.03 to 1.12; p < 0.001 for death and/or MI; HR: 1.10; 95% CI: 1.07 to 1.14; p < 0.001 for MACE). Adding an interaction term between ischemia and UMI in the multivariable model did not show a significant interaction between the 2 (ischemia × UMI: p-interaction = 0.976 for death and/or MI, p-interaction = 0.112 for MACE).

These results remained consistent within the 4-year study time frame (Supplemental Tables 6 and 7), after exclusion of patients with UMI and pathological ECG Q waves (Supplemental Table 8), in patients with and without documented CAD prior to the index CMR (Supplemental Table 9), and after further adjustment for aspirin, statin, and beta-blocker use (Supplemental Table 10). Finally, controlling for site of enrollment by adding an interaction term between site and UMI did not modify the robust prognostic value of UMI for death and/or MI (site × UMI p-for-interaction = 0.73) and MACE (site × UMI p-for-interaction = 0.11).

Prognostic value of UMI in patients without inducible ischemia on stress CMR

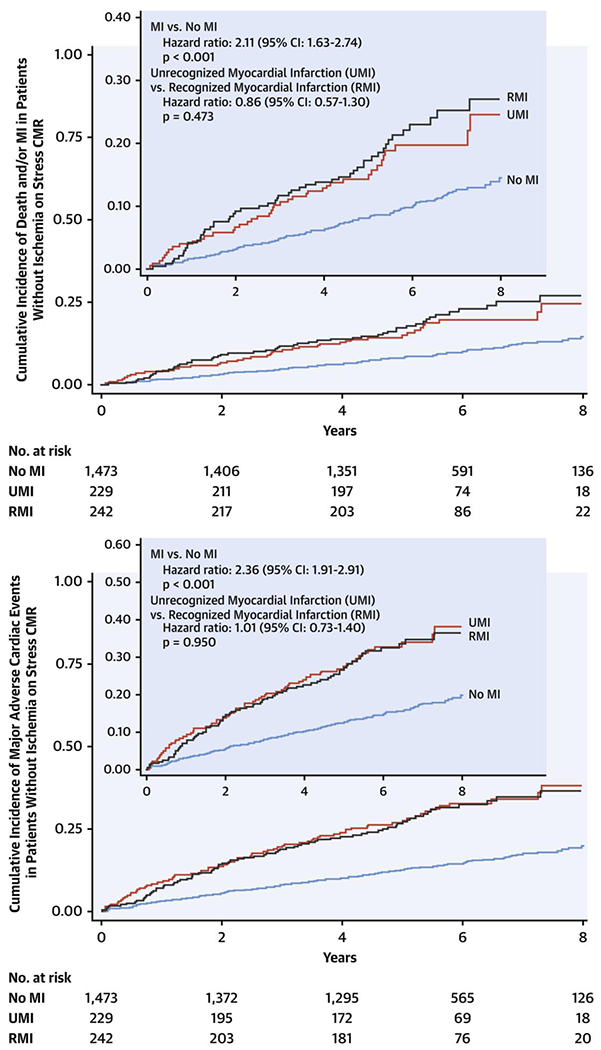

To explore the prognostic association of RMI and UMI with outcomes beyond myocardial ischemia, we further examined the subgroup of patients without inducible ischemia on stress CMR (n = 1,944). Event-free survival rates in patients with UMI were comparable to those in patients with RMI for death and/or MI (UMI vs. RMI: HR: 0.86; 95% CI: 0.57 to 1.30; p = 0.473) and MACE (UMI vs. RMI: HR: 1.01; 95% CI: 0.73 to 1.40; p = 0.950) on Kaplan-Meier curves, by the end of follow-up (Table 3, Figure 2) and at 4 years (Supplemental Table 2, Supplemental Figure 3). Presence of MI, whether clinically recognized or not, portended a significantly higher risk for death and/or MI and MACE compared with absence of MI, regardless of the presence of ischemia on stress CMR (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Time-to-Event Curves for Death and/or MI and MACE in Patients Without Ischemia on Stress CMR

Time-to-event curves for death and/or MI (top) and major adverse cardiac events (MACE) (bottom) in patients without ischemia on stress cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR). Event-free survival for patients with RMI, UMI, and neither form of MI are shown in black, red, and blue respectively. Statistical analysis using log-rank test for “no MI versus MI” and “UMI versus RMI.” CI = confidence interval; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

In multivariate analysis, in patients without ischemia on stress CMR, presence of MI remained strongly associated with death and/or MI and MACE, without significant difference between RMI and UMI, through the end of follow-up (Table 4) and at 4 years (Supplemental Tables 6 and 7). UMI maintained robust association with death and/or MI (UMI vs. no MI: HR: 1.56; 95% CI: 1.07 to 2.26; p = 0.019) and MACE, as did RMI (RMI vs. no MI: HR: 1.80; 95% CI: 1.29 to 2.51; p < 0.001 for death and/or MI). Accounting for myocardial extent of MI in our multivariate model, the number of involved MI segments maintained robust adjusted prognostic association for death and/or MI (UMI vs. no MI: HR: 1.04; 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.08; p = 0.033; RMI vs. no MI: HR: 1.06; 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.12; p = 0.041) and MACE (UMI vs. no MI: HR: 1.05; 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.08; p = 0.004; RMI vs. no MI: HR: 1.10; 95% CI: 1.05 to 1.15; p < 0.001), respectively.

Differential risk of RMI and UMI on MI and hospitalization for HF

Presence of MI (either UMI or RMI) carried a significantly worse prognosis for all-cause and CV mortality, nonfatal MI, hospitalization for unstable angina, or hospitalization for HF, independently of the presence of ischemia on stress CMR through the end of follow-up (Table 3, Supplemental Table 1) as well as at 4 years (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). Patients with RMI were more likely to experience nonfatal MIs and hospitalizations for unstable angina than patients with UMI (UMI vs. RMI: HR: 0.39; 95% CI: 0.22 to 0.68; p < 0.001 for nonfatal MI) (Table 3, Supplemental Figure 4), whereas patients with UMI were more likely to experience HF hospitalization (UMI vs. RMI: HR: 2.60; 95% CI: 1.48 to 4.58; p < 0.001) (Table 3, Supplemental Figure 4). These differences persisted after multivariate adjustment—including for ischemia, LVEF, number of LGE segments and CV risk factors, after excluding patients with ischemia from the analysis (Table 3) as well as within the 4-year study time frame (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3).

Discussion

In the multicenter SPINS cohort of patients with suspected CAD, our main findings indicate the following: 1) although UMI—as detected by CMR—is prevalent (15%) in this clinical setting, UMI patients are significantly less likely to be treated with secondary prevention GDMT than patients with RMI are; 2) UMI is strongly associated with death and/or MI and MACE, independently of the presence of ischemia; and 3) patients with UMI have a comparable long-term prognosis for death and/or MI and MACE to patients with RMI, but are at higher risk for HF hospitalization.

Prevalence and characteristics of patients with UMI

The prevalence of CMR-detected UMI has been reported to vary between 0.2% and 30% in the general population (8,13) and 19% and 27% in patients with suspected CAD (6). In our study, the prevalence of UMI was equal to that of RMI at 15% and UMI accounted for about one-half of the total number of MIs.

Prior studies have indicated that traditional coronary risk factors fail to differentiate UMI from RMI (14). Among patients with UMI—as identified by ECG—versus those with RMI, the prevalence of diabetes and hypertension in the Rotterdam, ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities), and Framingham Heart studies was not markedly different (10,15). Our study provided confirmational findings in this regard, as we observed equal prevalence of common risk factors between patients with UMI and those with RMI.

About one-third of patients with RMI had absence of LGE on stress CMR. RMIs with no myocardial scar by CMR could be explained by resorption of a small infarct after successful percutaneous coronary intervention, reversible pathology such as myocarditis mimicking MI, clinical misdiagnosis, or inaccuracy in patient history (16). Still, similar to previous studies (7,8,16), those patients had a significantly worse prognosis than did patients without clinical history of MI.

Under-recognition and undertreatment of UMI

More than one-third of patients with UMI did not receive aspirin or statin treatment at the time of stress CMR and after exclusion of patients with documented CAD prior to the index CMR (i.e., who already had an indication for GDMT as secondary prevention), only 55% and 52% of those with UMI were receiving aspirin and statin, respectively.

From a public health perspective, clinical trials and societies’ guidelines have so far focused either on nonfatal MI or subclinical atherosclerosis—detected either by coronary angiography or coronary computed tomographic angiography—to identify secondary prevention populations and recommend treatment. However, none of those approaches directly addresses UMI in patients with suspected CAD. Stress CMR in patients with suspected CAD has the ability to identify this high-risk subgroup that should benefit from intensive secondary preventive therapies, even in the absence of myocardial ischemia (7,12). Whether early preventive interventions following detection of UMI by CMR could reduce the associated long-term risks should be assessed in prospective trials.

UMI by CMR as a surrogate endpoint in clinical trials should also be considered because previous studies have suggested that expanded primary prevention in vulnerable CV groups may lead to reductions in UMI incidence. Given that modifiable CV risk factors—especially hypertension and diabetes mellitus—are strongly associated with UMI in the long term (9,16), intense modification of these risk factors in high-risk patients may reduce the development of UMI. CMR may have a role as both a baseline screening tool (17), as well as a noninvasive follow-up strategy in studies of UMI prevention in high CV risk populations.

UMI and long-term prognosis

In keeping with previous studies (6, 7, 8,12,15), patients with UMI, compared with patients without MI, had significantly higher rates for death and/or MI and MACE, as well as for every individual component of those outcomes. We observed a 2-fold rate for all-cause mortality, 4-fold rate for CV death, 4-fold rate for HF hospitalization, and 3-fold rate for nonfatal MI, and those rates remained practically unchanged after exclusion of patients with CMR-detected ischemia. Those findings indicate that the prognostic value of UMI is independent of the presence of underlying ischemia and may have important implications in our understanding of UMI pathophysiology, since undetected, silent ischemia is currently considered to be the prime driver of adverse outcomes in UMI (8,18,19).

Multicenter observational and randomized trials have demonstrated that stress CMR is at least noninferior to other stress imaging modalities or coronary angiography with fractional flow reserve for risk stratification of patients with stable CAD (2,20). Due to its superior spatial resolution, CMR can further identify the subset of patients with subclinical myocardial scar whose condition could be missed by clinical history, ECG, echocardiography, or nuclear perfusion imaging (3,4,6). Stress CMR may therefore present a comparative advantage for the identification of patients with suspected UMI where clinical assessment alone is insufficient or doubtful. This could include patients with diabetes or atypical anginal symptoms, equivocal ECG abnormalities, borderline or unexplained troponin elevation, or uncertainty about wall motion abnormalities on echocardiography.

UMI and its predisposition to HF hospitalization

We observed that patients with UMI and RMI had different predispositions to HF and nonfatal MI, independent of the presence of ischemia. Compared with patients with RMI, patients with UMI were more than twice as likely to be hospitalized for HF (11.8% vs. 5.0%; p < 0.001 for UMI vs. RMI) and those differences persisted after multivariable adjustment and after excluding patients with CMR-detected ischemia. Although the relationship between UMI and risk for HF is well established (10,19), myocardial ischemia has always been considered to be the main underlying mechanism for this association (10,19). Our study is the first to demonstrate that the effect of UMI on HF persists even in the absence of CMR-detected ischemia. Indeed, compared with RMI, UMI may be more associated with a lower epicardial plaque burden (lower coronary artery calcium), but more small-vessel involvement, myocardial fibrosis, and atrial fibrillation (7,8,21).

In comparison, patients with RMI had significantly higher rates of incident nonfatal MI and unstable angina. UMI and RMI groups included similar proportions of patients with ischemia, although the rates of previous percutaneous coronary intervention and CV preventive treatment in the RMI group were much higher (p < 0.001 for both). In addition, a previous CMR study by Barbier et al. (22) demonstrated that UMI was not associated with significant atherosclerosis in the rest of the body, whereas RMI was. The observations that patients with UMI and RMI experience increased risks for HF hospitalization and recurrent nonfatal MI, respectively, remain hypothesis generating and will need to be further studied in future trials.

Study limitations

First, we only had access to and reviewed ECGs in patients suspected to have UMI and not in the entire cohort. However, limited sensitivity and specificity have been reported in studies relying on ECG to identify UMI (8,11,18) and our results remained unchanged after accounting for pathological Q waves in patients with UMI. Second, due to infarct contraction and resorption, LGE imaging can miss small endocardial UMI after acute infarct healing, thus reducing its sensitivity. Black blood LGE (23) and 3-dimensional LGE (24) have both been shown to increase the sensitivity of detecting small MIs. At the time of our study, these techniques were not available to any of our participating sites, and future studies should address any improvement in CMR yield for myocardial scar detection in this regard. Given that invasive coronary angiography was not performed in all patients in our cohort, the true diagnostic accuracy of stress CMR for CAD could not be determined. However, prior clinical studies have established high diagnostic accuracy of stress CMR in settings similar to those of our study (2,20). Finally, given the retrospective design of this study, we could not capture all the direct therapeutic and management decisions following CMR, including subsequent changes to medical regimen.

Conclusions

In a multicenter cohort of patients with suspected CAD, UMI was highly prevalent and carried significant risk toward patient mortality and nonfatal MI, incremental to the prognostic value of ischemia and LVEF. Patients with UMI were significantly less likely to be on GDMT prior to CMR and experienced a long-term prognosis comparable to that of patients with RMI. Compared with RMI, UMI carried a disproportionately increased risk for HF hospitalization that warrants further study.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CI

confidence interval

- CMR

cardiac magnetic resonance

- CV

cardiovascular

- ECG

electrocardiography

- GDMT

guideline-directed medical therapy

- HF

heart failure

- HR

hazard ratio

- LGE

late gadolinium enhancement

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- MACE

major adverse cardiac events

- MI

myocardial infarction

- UMI

unrecognized myocardial infarction

- RMI

recognized myocardial infarction

References

- 1.Kwong RY, Ge Y, Steel K, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance stress perfusion imaging for evaluation of patients with chest pain. J Am Coll Cardiol, 74 (2019), pp. 1741–1755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagel E, Greenwood JP, McCann GP, et al. , for the MR-INFORM Investigators. Magnetic resonance perfusion or fractional flow reserve in coronary disease. N Engl J Med, 380 (2019), pp. 2418–2428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner A, Mahrholdt H, Holly TA, et al. Contrast-enhanced MRI and routine single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) perfusion imaging for detection of subendocardial myocardial infarcts: an imaging study. Lancet, 361 (2003), pp. 374–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu E, Ortiz JT, Tejedor P, et al. Infarct size by contrast enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance is a stronger predictor of outcomes than left ventricular ejection fraction or end-systolic volume index: prospective cohort study. Heart, 94 (2008), pp. 730–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim HW, Klem I, Shah DJ, et al. Unrecognized non-Q-wave myocardial infarction: prevalence and prognostic significance in patients with suspected coronary disease. PLoS Med, 6 (2009), Article e1000057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwong RY, Chan AK, Brown KA, et al. Impact of unrecognized myocardial scar detected by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging on event-free survival in patients presenting with signs or symptoms of coronary artery disease. Circulation, 113 (2006), pp. 2733–2743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acharya T, Aspelund T, Jonasson TF, et al. Association of unrecognized myocardial infarction with long-term outcomes in community-dwelling older adults: the ICELAND MI study. JAMA Cardiol, 3 (2018), pp. 1101–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schelbert EB, Cao JJ, Sigurdsson S, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of unrecognized myocardial infarction determined by cardiac magnetic resonance in older adults. JAMA, 308 (2012), pp. 890–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwong RY, Sattar H, Wu H, et al. Incidence and prognostic implication of unrecognized myocardial scar characterized by cardiac magnetic resonance in diabetic patients without clinical evidence of myocardial infarction. Circulation, 118 (2008), pp. 1011–1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qureshi WT, Zhang ZM, Chang PP, et al. Silent myocardial infarction and long-term risk of heart failure: the ARIC study. J Am Coll Cardiol, 71 (2018), pp. 1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leening MJ, Elias-Smale SE, Felix JF, et al. Unrecognised myocardial infarction and long-term risk of heart failure in the elderly: the Rotterdam study. Heart, 96 (2010), pp. 1458–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pride YB, Piccirillo BJ, Gibson CM. Prevalence, consequences, and implications for clinical trials of unrecognized myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol, 111 (2013), pp. 914–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbier CE, Nylander R, Themudo R, et al. Prevalence of unrecognized myocardial infarction detected with magnetic resonance imaging and its relationship to cerebral ischemic lesions in both sexes. J Am Coll Cardiol, 58 (2011), pp. 1372–1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turkbey EB, Nacif MS, Guo M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of myocardial scar in a US cohort JAMA, 314 (2015), pp. 1945–1954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dehghan A, Leening MJ, Solouki AM, et al. Comparison of prognosis in unrecognized versus recognized myocardial infarction in men versus women >55 years of age (from the Rotterdam study). Am J Cardiol, 113 (2014), pp. 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McAreavey D, Vidal JS, Aspelund T, et al. Midlife cardiovascular risk factors and late-life unrecognized and recognized myocardial infarction detect by cardiac magnetic resonance: ICELAND-MI, the AGES-Reykjavik study J Am Heart Assoc, 5 (2016), Article e002420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoon YE, Kitagawa K, Kato S, et al. Prognostic value of unrecognised myocardial infarction detected by late gadolinium-enhanced MRI in diabetic patients with normal global and regional left ventricular systolic function. Eur Radiol, 23 (2013), pp. 2101–2108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheifer SE, Gersh BJ, Yanez ND 3rd, Ades PA, Burke GL, Manolio TA. Prevalence, predisposing factors, and prognosis of clinically unrecognized myocardial infarction in the elderly J Am Coll Cardiol, 35 (2000), pp. 119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soliman EZ. Silent myocardial infarction and risk of heart failure: current evidence and gaps in knowledge. Trends Cardiovasc Med, 29 (2019), pp. 239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenwood JP, Ripley DP, Berry C, et al. , for the CE-MARC 2 Investigators. Effect of care guided by cardiovascular magnetic resonance, myocardial perfusion scintigraphy, or NICE guidelines on subsequent unnecessary angiography rates: the CE-MARC 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 316 (2016), pp. 1051–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohrn AM, Schirmer H, von Hanno T, et al. Small and large vessel disease in persons with unrecognized compared to recognized myocardial infarction: the Tromso study 2007–2008. Int J Cardiol, 253 (2018), pp. 14–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barbier CE, Bjerner T, Hansen T, et al. Clinically unrecognized myocardial infarction detected at MR imaging may not be associated with atherosclerosis. Radiology, 245 (2007), pp. 103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellman P, Xue H, Olivieri LJ, et al. Dark blood late enhancement imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson, 18 (2016), p. 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lintingre P-F, Nivet H, Clément-Guinaudeau S, et al.High-resolution late gadolinium enhancement magnetic resonance for the diagnosis of myocardial infarction with nonobstructed coronary arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol Img, 13 (2020), pp. 1135–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.