Abstract

People with COVID-19 might have sustained postinfection sequelae. Known by a variety of names, including long COVID or long-haul COVID, and listed in the ICD-10 classification as post-COVID-19 condition since September, 2020, this occurrence is variable in its expression and its impact. The absence of a globally standardised and agreed-upon definition hampers progress in characterisation of its epidemiology and the development of candidate treatments. In a WHO-led Delphi process, we engaged with an international panel of 265 patients, clinicians, researchers, and WHO staff to develop a consensus definition for this condition. 14 domains and 45 items were evaluated in two rounds of the Delphi process to create a final consensus definition for adults: post-COVID-19 condition occurs in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, usually 3 months from the onset, with symptoms that last for at least 2 months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis. Common symptoms include, but are not limited to, fatigue, shortness of breath, and cognitive dysfunction, and generally have an impact on everyday functioning. Symptoms might be new onset following initial recovery from an acute COVID-19 episode or persist from the initial illness. Symptoms might also fluctuate or relapse over time. A separate definition might be applicable for children. Although the consensus definition is likely to change as knowledge increases, this common framework provides a foundation for ongoing and future studies of epidemiology, risk factors, clinical characteristics, and therapy.

Introduction

As of Dec 3, 2021, more than 263 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 and more than 5·2 million deaths have been reported to WHO, although estimates of 2020 greatly surpass these figures.1 However, the natural history, clinical course, and long-term consequences of this new disease are still not completely understood.2

Most patients with COVID-19 return to their baseline state of health after acute infection with SARS-CoV-2, but a proportion report ongoing health problems. The number of people affected with late sequelae after the acute COVID-19 episode remains unknown. Persistent symptoms are reported to be more prevalent in women, and risk of persistent symptoms is reported to be linearly related to age.3, 4 These effects appear to occur irrespective of the initial severity of infection, and are often linked to multiple organ systems. One study found that up to 70% of individuals at low risk of mortality from COVID-19 have impairment in one or more organs (ie, heart, lungs, kidneys, liver, pancreas, or spleen) 4 months after initial COVID-19 symptoms.5

In September, 2020, and in response to requests from Member States, the WHO Classification and Terminologies unit created International Classification of Diseases 10 (ICD-10) and ICD-11 codes for post-COVID-19 condition.6 Over the course of the pandemic, several definitions of post-COVID-19 condition have been proposed, including long COVID or long-haul COVID (appendix p 3). Absence of both a single terminology and a clinical case definition have been repeatedly signalled as drawbacks to advance on epidemiological reporting, research, policy making, and clinical management of affected patients. Standardisation of nomenclature and clinical case definition is required to facilitate global discussion and streamline research methods, management strategies, and policies. The objective of this Review is to establish the domains and variables for inclusion into a standardised clinical case definition for post-COVID-19 condition.

Methods

Study design and participants

This Review is a prospective, Delphi consensus-seeking exercise and mixed, iterative survey of internal and external experts, patients, and other stakeholders (the research protocol is available as a preprint).7 The Delphi method is a structured communication technique originally developed as a systematic, interactive, forecasting method that relies on a panel of experts.8, 9 It has been widely used for research and has certain advantages over other structured forecasting approaches.10, 11

The primary users of the clinical case definition for the post-COVID-19 condition will include patients, relatives and caregivers, clinicians, researchers, advocacy groups, policy makers, health and disability insurance providers, and media. We therefore aimed to have a diverse representation of participants, including clinicians with expertise in a variety of disciplines such as quality improvement and research, patients who have had COVID-19 and its mid-term and longer-term effects, researchers, policy makers, and others from countries representing all WHO regions and World Bank income levels. There were no specific exclusion criteria for participants. A statement explaining implied consent was on the title page of the survey, with consent to participate in the survey implied by answering and returning the surveys. Participants could withdraw at any time.

Study procedures

Participants were identified from internal WHO stakeholder lists and through active engagement with WHO networks. Participant list sources included clinician and patient researchers who had attended a previous WHO global webinar on post-COVID-19 condition, members of the WHO COVID-19 Clinical Characterization and Management research working group, members of the WHO COVID-19 Clinical Network, members of the LongCovidSOS patient group, and clinicians and patients nominated by WHO officers.

Participants were invited via an online recruitment letter soliciting participation and engagement, along with an explanation of study objectives, instructions, and outputs. The survey contained listed options regarding domains and variables to consider in the definition, which were initially kept as broad and comprehensive as possible. The domains and variables were followed by a series of questions relating to these variables with eventual values or thresholds related to each. Survey responses were anonymous and tabulated by groups only. Registration of panelists and the actual Delphi questionnaire (appendix pp 4–37) were accessible on the DelphiManager website.12

All questions were evaluated on a nine-point Likert scale, from 1 (least important) to 9 (most important) and participants were asked to choose the level of importance for each variable in the definition. Whenever there was a value in the DelphiManager rating column that was something other than the Likert scale values of 1–9, the system coded as −9, the value allocated when an outcome had not been rated; or 10, the value allocated to the “Unable to rate” option.

The first round of the Delphi exercise lasted 14 days, and participants were sent two reminders to complete the online survey. Participants had the opportunity to add comments for each item and to add new domains or variables. After review of the data from the first round, the WHO working group created a second round questionnaire, removing items that received low scores, clarifying terms and uncertainties in wording, and adding a new domain suggested by participants. The second round was done 5 weeks later, used a modified questionnaire based on iterative feedback and consensus during round one, and lasted 8 days, again with two reminders. In round two, participants from round one were provided with the number and percentage of respondents having chosen that answer, and a reminder of their individual answer in round one. In round two, participants had the opportunity to add comments for each item.

Statistical plan

The optimal sample size for a Delphi exercise is not well defined; however, there is general acceptance that 12–18 participants should be included in each group.13 We sought views from a diverse sample of stakeholder groups and WHO regions (African region, region of the Americas, Eastern Mediterranean region, European region, South-East Asia region, and Western Pacific region). We defined five stakeholder groups: patients, patient-researchers, external experts, WHO staff, and others (advocacy groups, policy makers, health and disability insurance, and media). Considering that participants could be included in more than one category and that response rates might vary by group, we sent out participation invitations to a broad group of individuals identified through WHO resources. Although we sought a minimum number of participants per group, no maximum was established.

Primary and secondary endpoints

The primary objective was to achieve consensus on the importance of the variables and values included in the definition. Consensus was achieved on a question if 70% or more of the responses fell within 7–9 on the nine-point Likert scale (appendix p 2). Disagreement was considered to occur if 35% or more of the responses fell within both of the two extreme ranges of possible options on the Likert scale (1–3 and 7–9). All other combinations of panel answers were considered as partial agreement. For each question, consensus proportions were considered on the basis of the number or percentage of respondents (excluding the category “Not my area of expertise”). Therefore, the denominator for the consensus included only participants with knowledge and expertise for that specific question. Participant responses, including baseline and demographic characteristics, were analysed with basic statistics such as mean (SD), median (IQR), and range. Responses on all other domains were analysed in proportions and illustrated with histograms.

Results

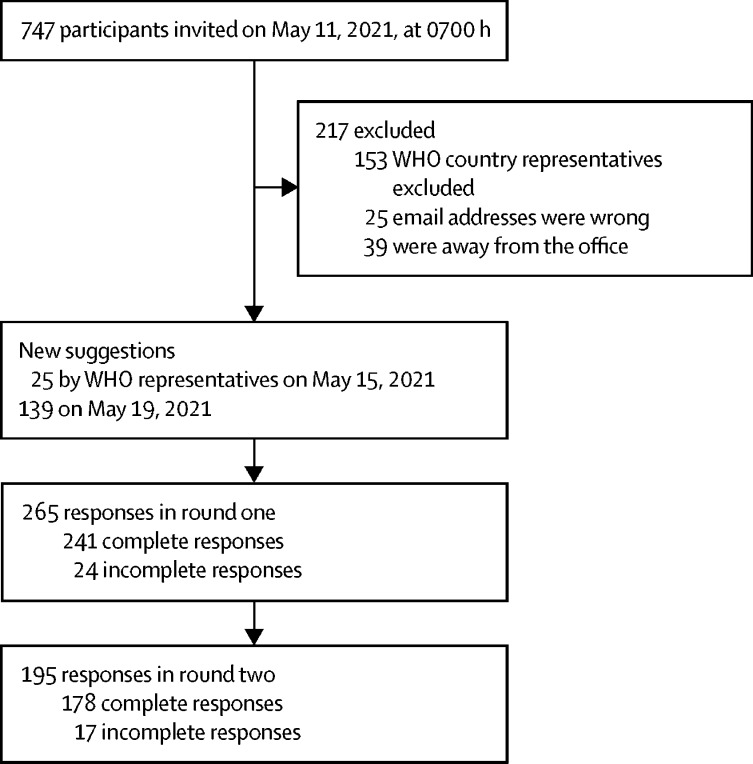

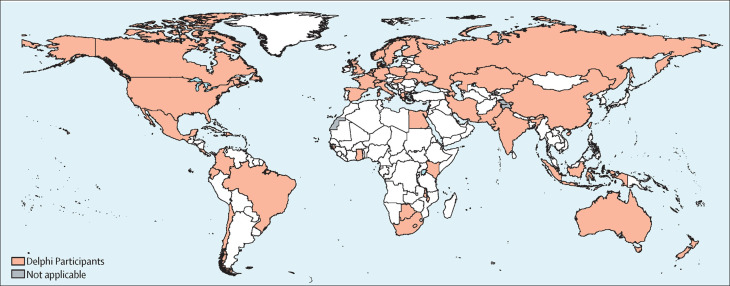

On May 11, 2021, 747 invitations were sent by email. There were 265 respondents in round one (demographics in table ), with 241 complete responses and 24 incomplete responses by May 24, 2021. In round two there were 195 respondents, with 178 complete responses and 17 incomplete responses by June 21, 2021 (figure 1 ). In round one, there were 61 (23%) patients, 18 (7%) patient-researchers, 138 (52%) external experts, 33 (12%) WHO staff, and 15 (6%) were in the “Other” category. There were 115 (43%) female participants, 147 (55%) male participants, one (<1%) non-binary participant, and two (1%) who preferred not to say in round one, with ages ranging from 20 years to 90 years or older, but most participants were in their 40s. Responses were received from participants in countries representing all WHO regions and World Bank income groups (figure 2 ). The subset of participants in round two did not differ from round one (table).

Table.

Demographic characteristics of participants

| Round one (N=265) | Round two (N=195) | |

|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder group | ||

| Patient | 61 (23%) | 47 (24%) |

| Patient-researcher | 18 (7%) | 13 (7%) |

| External experts | 138 (52%) | 103 (53%) |

| WHO staff | 33 (12%) | 22 (11%) |

| Other* | 15 (6%) | 10 (5%) |

| Gender | ||

| Woman | 115 (43%) | 86 (44%) |

| Man | 147 (55%) | 107 (55%) |

| Non-binary | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) |

| Age, years | ||

| 20–29 | 16 (6%) | 11 (6%) |

| 30–39 | 53 (20%) | 42 (22%) |

| 40–49 | 86 (32%) | 63 (32%) |

| 50–59 | 73 (28%) | 52 (27%) |

| 60–69 | 32 (12%) | 22 (11%) |

| 70–79 | 4 (2%) | 4 (2%) |

| 90 or older | 1 (<1%) | 1 (1%) |

| WHO region | ||

| African | 9 (3%) | 8 (4%) |

| Americas | 53 (20%) | 36 (18%) |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 7 (3%) | 4 (2%) |

| European | 94 (35%) | 70 (36%) |

| South-East Asia | 10 (4%) | 8 (4%) |

| Western Pacific | 19 (7%) | 18 (9%) |

| Country not specified | 73 (28%) | 51 (26%) |

| World Bank income group | ||

| High income | 140 (53%) | 110 (56%) |

| Upper middle income | 37 (14%) | 22 (11%) |

| Lower middle income | 13 (5%) | 10 (5%) |

| Low income | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) |

| Country not specified | 73 (28%) | 51 (26%) |

Data are n (%).

Included journalists and policy makers.

Figure 1.

STROBE flowchart of participation in the two Delphi rounds

Figure 2.

Distribution of participants worldwide

Distribution of participants in May and June, 2021.

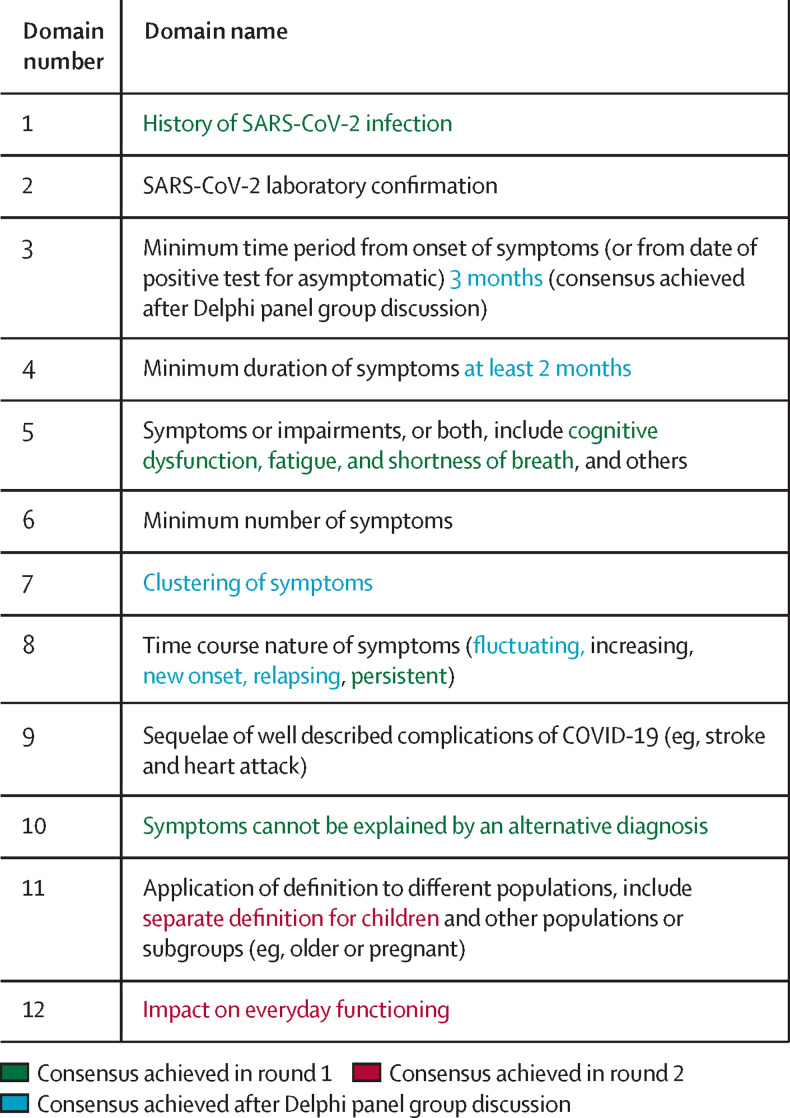

After the first round of responses, three of the 14 domains were excluded and a new domain added on the basis of participant comments; thus there were a total of 12 domains in round two (figure 3 ). Similarly, on the basis of the comments and after further discussion of the working group on results that reached borderline significance based on predefined thresholds, the domains were expanded with variables, such as new symptoms, for 45 items (appendix pp 38–42). During subsequent revision, two domains that did not fully reach prespecified thresholds were included in the clinical case definition after panel discussion—namely, “a minimum time period (in months) from the onset of COVID-19 to the presence of symptoms” and “duration of symptoms”. Similarly, the “new onset” nature of symptoms was expanded to incorporate relapsing and fluctuating through patient–panel feedback. A clinical case definition was built and further expanded with those domains, thresholds, and values, and wording was trimmed in a dedicated quantitative and qualitative discussion with patients and patient-researchers (panel ). Post-COVID-19 condition occurs in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, usually 3 months from the onset of COVID-19 and with symptoms that last for at least 2 months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis. Common symptoms include fatigue, shortness of breath, and cognitive dysfunction, but also others (appendix pp 38–42), and generally have an impact on everyday functioning. Symptoms might be new onset after initial recovery from an acute COVID-19 episode or persist from the initial illness. Symptoms might also fluctuate or relapse over time. A separate definition might be applicable for children.

Figure 3.

Domains that achieved consensus by participants in each Delphi stage

Panel. A definition of the post-COVID-19 condition.

Post-COVID-19 condition occurs in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, usually 3 months from the onset of COVID-19 with symptoms that last for at least 2 months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis. Common symptoms include fatigue, shortness of breath, and cognitive dysfunction (other symptoms are listed in the appendix [p 4] and published literature14), and generally have an impact on everyday functioning. Symptoms might be new onset after initial recovery from an acute COVID-19 episode or persist from the initial illness. Symptoms might also fluctuate or relapse over time.

A separate definition might be applicable for children.

Notes

There is no minimum number of symptoms required for the diagnosis; symptoms involving different organs systems and clusters have been described.

Definitions

-

•

Fluctuate: a change from time to time in quantity or quality

-

•

Relapse: return of disease manifestations after period of improvement

-

•

Cluster: two or more symptoms that are related to each other and that occur together; they are composed of a stable groups of symptoms, are relatively independent of other clusters, and might reveal specific underlying dimensions of symptoms15

Discussion

By means of a Delphi process involving two rounds, we identified domains and variables to be included in a clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition—the name proposed by WHO ICD-10 diagnosis code U09 in September, 2020. A definition based on these domains was created.

This clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition is intended to be applied in the community and health-care setting to optimise recognition and care of individuals with post-COVID-19 condition; it is not meant to replace other terms but be used in a more standardised way. This definition was obtained by a robust, protocol-based methodology (Delphi consensus), engaging a diverse group of representative patients, caretakers, and other stakeholders from many areas. This definition is compatible and consistent with previous suggestions available elsewhere (appendix p 3), but is likely to change as new evidence emerges and our understanding of the consequences of COVID-19 continues to evolve. To date, there have been several attempts to define different COVID-19-related topics and outcomes,15, 16, 17, 18 but existing definitions do not take into account presentations in low and middle-income countries and often miss domains that are relevant to various groups of stakeholders. To our knowledge, ours is the first Delphi exercise to define post-COVID-19 condition with these stakeholder inputs.

Strengths of this study include a robust protocol-based Delphi method and inclusiveness and representation of participants from five diverse stakeholder groups, from countries representing all WHO regions and World Bank income groups. We aimed to surpass current controversies on the naming of the condition (eg, chronic COVID-19 syndrome, late sequelae of COVID-19, long COVID, long haul COVID, long-term COVID-19, post COVID syndrome, post-acute COVID-19, and post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection [or PASC]) by using the WHO terminology of post-COVID-19 condition. We acknowledge patients' activism done under the different names for this condition.19, 20

Our study has several limitations. English language was selected for practicality issues, but subsequent Delphi exercises should include other languages. Response rates in both rounds could have been greater, which is not unexpected, given its conduct during a pandemic. Best practices for enhancing response rates were integrated throughout,21 including introductory messages and reminder emails. Responses from the African and Eastern Mediterranean regions were especially sought and obtained, but their overall proportions were lower than from other regions. Additionally, participants older than 70 years are under-represented. Wording of some domains and addition of new items and values were modified from round one to round two. Our protocol called for only two rounds of consensus-building. Items addressing the timing and duration of symptoms did not reach prespecified criteria for consensus, and should be interpreted in the light of this limitation. Overall, as several pathophysiological mechanisms are in place and interplay during and after acute infection,22 and different trajectories for recovery after COVID-19 exist,23 producing a single, universal definition that might work well for clinical, research, policy and advocacy grounds, and for all care levels and severities might be overly ambitious. The definition presented in this Review (panel) might be considered a description based on opinion of those individuals participating, and difficult to operationalise in practice. Not only timing and duration, but the symptoms are susceptible to subjectivity and bias of participants. We strongly support that this is open discussion in an organised way and integration of emerging evidence, such as prospective cohort trials, should help to advance this field.

As mentioned, this proposal of a clinical case definition is probably temporary, as new data continue to emerge. Initial reports describing post-COVID-19 condition were from small patient samples with an inherently short follow-up, and are likely to be subject to bias,24 which will be unravelled in ongoing meta-analyses.25 New research is exploring the use of electronic health records from representative samples of patients identified in primary care and elsewhere.26 The use of comparator samples of individuals fully recovered after acute infection is envisaged. By use of cluster analysis and other mathematical tools to establish specific symptoms and their minimum number, they all could be formally identified and eventually clustered for different phenotypes. Notably, time thresholds from onset of infection or the duration of these symptoms possibly will be established.27, 28

Conclusion

COVID-19 will remain a challenge for the foreseeable future.29 Many pending answers surrounding COVID-19 and its sequelae remain, with new questions constantly being formulated.30, 31, 32 This global definition of post-COVID-19 condition will help to advance both advocacy and research, but will probably change as new evidence emerges and our understanding of the consequences of COVID-19 continues to evolve.

Search strategy and selection criteria

References for this Review were identified through searches of PubMed for articles published from Jan 1, 2020, to Aug 30, 2021, with the terms “COVID-19”, “post-COVID-19 condition”, “chronic COVID-19 syndrome”, “late sequelae of COVID-19”, “long COVID”, “long haul COVID”, “long-term COVID-19”, “post COVID syndrome”, “post-acute COVID-19”, and “post-acute sequelae of SARSCoV-2 infection (PASC)”. Cross-referencing of relevant published articles were also identified through searches in the authors' personal files and several WHO Expert Panels. Articles resulting from these searches and relevant references cited in those articles were reviewed. Articles published in English, but also abstracts in non-English languages, were included.

For more on the WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard see https://covid19.who.int/

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This study was funded internally by WHO. There were no payments to participants. We thank all participants, and particularly the patients and patient-researchers with post-COVID-19 condition who contributed their time and expertise to this Delphi exercise. We also thank Paula Williamson (University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK) for providing free access to the DelphiManager software and Bridget Griffith for her technical support in organising data from DelphiManager. JBS was a Senior Consultant from November, 2020, to July, 2021, at the COVID-19 Clinical Management Team, WHO Health Emergency Programme (World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland).

Contributors

JBS, JCM, JVD, and SM wrote the research protocol. PR, JCM, and JVD accessed and verified all data. PR analysed the data. JBS and JCM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing and approved the final version.

WHO Clinical Case Definition Working Group on Post-COVID-19 Condition

Switzerland Maya Allan, Lisa Askie, Carine Alsokhn, Janet V Diaz, Tarun Dua, Wouter de Groote, Robert Jakob, Marta Lado, Jacobus Preller, Pryanka Relan, Nicoline Schiess, Archana Seahwag, Joan B Soriano. UK Nisreen A Alwan. USA Hannah E Davis. Canada John Marshall, Srinivas Murthy.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.WHO World health statistics. 2021. https://www.who.int/data/gho/publications/world-health-statistics

- 2.The Royal Society Long Covid: what is it, and what is needed? Oct 23, 2020. https://royalsociety.org/-/media/policy/projects/set-c/set-c-long-covid.pdf

- 3.Thompson EJ, Williams DM, Walker AJ, et al. Risk factors for long COVID: analyses of 10 longitudinal studies and electronic health records in the UK. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.06.24.21259277. published online Jan 1. (preprint). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitaker M, Elliott J, Chadeau-Hyam M, et al. Persistent symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection in a random community sample of 508,707 people. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.06.28.21259452. published online Jan 1. (preprint). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dennis A, Wamil M, Alberts J, et al. Multiorgan impairment in low-risk individuals with post-COVID-19 syndrome: a prospective, community-based study. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO Emergency use ICD codes for COVID-19 disease outbreak. https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases/emergency-use-icd-codes-for-covid-19-disease-outbreak

- 7.Diaz JV, Soriano JB. A Delphi consensus to advance on a clinical case definition for post covid-19 condition: a WHO protocol. Protoc Exch. 2021 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.pex-1480/v1. published online June 25. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalkey N, Helmer O. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Manage Sci. 1963;9:458–467. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown BB. Delphi process: a methodology used for the elicitation of opinions of experts. 1968. https://www.rand.org/pubs/papers/P3925.html

- 10.Green KC, Armstrong JS, Graefe A. Methods to elicit forecasts from groups: Delphi and prediction markets compared. 2007. https://repository.upenn.edu/marketing_papers/157/

- 11.Rowe G, Wright G. The Delphi technique as a forecasting tool: issues and analysis. Int J Forecast. 1999;15:353–375. [Google Scholar]

- 12.COMET Initiative Delphi Manager. https://www.comet-initiative.org/delphimanager/

- 13.Murphy E, Black N, Lamping D, et al. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development: a review. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2:i–iv. 1-88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinMed. 2021;38 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barber C. The problem of ‘long haul’ COVID. Sci Am. Dec 29, 2020 https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-problem-of-long-haul-covid/?print=true [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shanbehzadeh M, Kazemi-Arpanahi H, Mazhab-Jafari K, Haghiri H. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) surveillance system: development of COVID-19 minimum data set and interoperable reporting framework. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9:203. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_456_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nasa P, Azoulay E, Khanna AK, et al. Expert consensus statements for the management of COVID-19-related acute respiratory failure using a Delphi method. Crit Care. 2021;25:106. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03491-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schell CO, Khalid K, Wharton-Smith A, et al. Essential emergency and critical care: a consensus among global clinical experts. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alwan NA, Burgess RA, Ashworth S, et al. Scientific consensus on the COVID-19 pandemic: we need to act now. Lancet. 2020;396:e71–e72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32153-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinMed. 2021;38 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burns KE, Duffett M, Kho ME, et al. A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. CMAJ. 2008;179:245–252. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Lancet Respiratory Medicine COVID-19 pathophysiology: looking beyond acute disease. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:545. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00242-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakurai A, Sasaki T, Kato S, et al. Natural history of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:885–886. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2013020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rando HM, Bennett TD, Byrd JB, et al. Challenges in defining long COVID: striking differences across literature, electronic health records, and patient-reported information. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.03.20.21253896. published online March 26. (preprint). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iqbal FM, Lam K, Sounderajah V, Clarke JM, Ashrafian H, Darzi A. Characteristics and predictors of acute and chronic post-COVID syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinMed. 2021;36 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soriano JB, Waterer G, Peñalvo JL, Rello J. Nefer, Sinuhe and clinical research assessing post COVID-19 condition. Eur Respir J. 2021;57 doi: 10.1183/13993003.04423-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun C, Hong S, Song M, Li H, Wang Z. Predicting COVID-19 disease progression and patient outcomes based on temporal deep learning. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2021;21:45. doi: 10.1186/s12911-020-01359-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Lancet Digital Health Artificial intelligence for COVID-19: saviour or saboteur? Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3:e1. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30295-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muller JE, Nathan DG. COVID-19, nuclear war, and global warming: lessons for our vulnerable world. Lancet. 2020;395:1967–1968. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31379-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norton A, Olliaro P, Sigfrid L, et al. Long COVID: tackling a multifaceted condition requires a multidisciplinary approach. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:601–602. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00043-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lerner AM, Robinson DA, Yang L, et al. Toward understanding COVID-19 recovery: National Institutes of Health Workshop on Postacute COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:999–1003. doi: 10.7326/M21-1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diaz JV, Herridge M, Bertagnolio S, et al. Towards a universal understanding of post COVID-19 condition. Bull World Health Organ. 2021;99:901–903. doi: 10.2471/BLT.21.286249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.