Summary

Background

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has revealed the vulnerability of immunisation systems worldwide, although the scale of these disruptions has not been described at a global level. This study aims to assess the impact of COVID-19 on routine immunisation using triangulated data from global, country-based, and individual-reported sources obtained during the pandemic period.

Methods

This report synthesised data from 170 countries and territories. Data sources included administered vaccine-dose data from January to December, 2019, and January to December, 2020, WHO regional office reports, and a WHO-led pulse survey administered in April, 2020, and June, 2020. Results were expressed as frequencies and proportions of respondents or reporting countries. Data on vaccine doses administered were weighted by the population of surviving infants per country.

Findings

A decline in the number of administered doses of diphtheria–pertussis–tetanus-containing vaccine (DTP3) and first dose of measles-containing vaccine (MCV1) in the first half of 2020 was noted. The lowest number of vaccine doses administered was observed in April, 2020, when 33% fewer DTP3 doses were administered globally, ranging from 9% in the WHO African region to 57% in the South-East Asia region. Recovery of vaccinations began by June, 2020, and continued into late 2020. WHO regional offices reported substantial disruption to routine vaccination sessions in April, 2020, related to interrupted vaccination demand and supply, including reduced availability of the health workforce. Pulse survey analysis revealed that 45 (69%) of 65 countries showed disruption in outreach services compared with 27 (44%) of 62 countries with disrupted fixed-post immunisation services.

Interpretation

The marked magnitude and global scale of immunisation disruption evokes the dangers of vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks in the future. Trends indicating partial resumption of services highlight the urgent need for ongoing assessment of recovery, catch-up vaccination strategy implementation for vulnerable populations, and ensuring vaccine coverage equity and health system resilience.

Funding

US Agency for International Development.

Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has scarcely left any corner of the world untouched, with millions of lives lost as a direct result of the virus. Equally important are the indirect effects of the pandemic. Disruptions of routine health services are likely to increase morbidity and mortality, leaving women and children particularly vulnerable. Systems for routine childhood immunisation have been greatly impacted globally, and in May, 2020, WHO announced there were at least 80 million children younger than 1 year of age who were at risk of missing life-saving vaccinations.1 Pandemic-related disturbances have jeopardised previous gains in immunisation services, with major implications on vaccine-preventable disease eradication and elimination efforts. Immense challenges abound in obtaining accurate and systematic measurements of these changes in immunisation status globally.

Estimates of vaccination coverage in 2020 suggested that 23 million children missed out on basic vaccines through routine immunisation services, which is 3·7 million more than in 2019.2 Modelled estimates of disruptions to routine childhood immunisation coverage in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic had suggested even higher numbers of more than 8 million children who missed out on their third dose of diphtheria–pertussis–tetanus-containing vaccine (DTP3) and first dose of measles-containing vaccine (MCV1).3 Although knowledge of these immunity gaps is crucial for nations to plan on addressing the situation, an accurate assessment of global vaccine disruptions would provide a clearer picture. Although immunisation programmes were severely affected in 2020, the full impact of disruption and ensuing consequences are not yet fully known, given that reporting delays and completeness, and limited data on catch-up activities, have affected routine monitoring of coverage. The analysis presented here is a compilation of several data sources collected through partner collaborations from March to December, 2020, aimed to assess the extent and main factors of global disruptions in immunisation, and trends toward recovery from these disruptions.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted many systems around the world. Immunisation services remain vulnerable, as many components of the service provision chain have been interrupted. Independent reports from different regions and countries have indicated partial or complete suspension of vaccination clinics, resulting in potentially large numbers of unvaccinated children who remain susceptible to infections. Although immunisation programmes are known to have been severely affected in 2020, the full extent of disruption and ensuing consequences are not fully studied.

Added value of this study

This report presents a comprehensive set of assessments of the impact of COVID-19 on routine immunisation, and uses three separate global data sources that included detailed reports from WHO regional offices representing their member states, self-reported data from the WHO-led pulse surveys from early 2020, and objective data from countries on administered vaccine doses delivered in 2019 and 2020. Together the datasets provide compelling evidence of a precipitous drop in immunisation services during the first half of 2020, and associated factors, followed by partial recovery in the ensuing months. Attributable reasons for the decline include vaccination demand factors, such as public fear and transport restrictions, and vaccination supply factors, including supply-chain disruptions and reduced availability of the health workforce. The greatest decline in immunisation was observed in April, 2020, when 33% fewer vaccines (third dose of diphtheria–pertussis–tetanus-containing vaccine) were administered globally, ranging from 9% in the WHO African region to 57% in the South-East Asia region. Countries experienced greater disruption in outreach services than fixed-post immunisation services, indicating that vulnerable populations were probably more affected. Taken together, this analysis highlights historic disruption to vaccination services across the world, and examines the indirect effects of COVID-19 on health systems and delivery.

Implications of all the available evidence

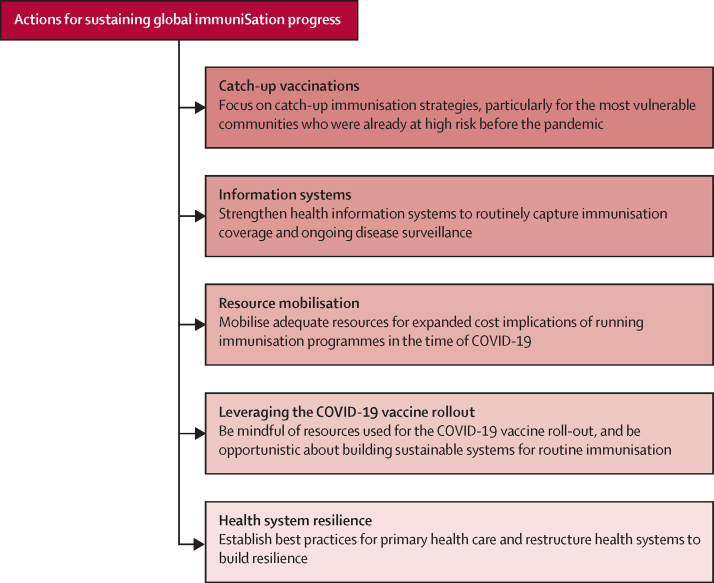

The magnitude and global scale of disruption of immunisation services provides a window into the potential dangers of vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks in the future, and greater morbidity and mortality from these indirect effects of the pandemic. To stem these disruptions and work towards a more equitable world, urgent actions are proposed to address catch-up vaccinations particularly for vulnerable communities, strengthen health information systems to routinely capture immunisation coverage and ongoing disease surveillance, find synergies with the COVID-19 vaccine rollout, mobilise resources for sustaining immunisation services, and restructure health systems to build resilience.

Methods

Regional data from WHO regional offices

WHO regional offices collected information from their respective member states to understand the status of routine immunisation within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Data-collection instruments and methods differed by region, ranging from web-based surveys, spreadsheets, and free-text reports based on phone calls or other communications. Routine immunisation sessions were characterised as disrupted if there were indications that either fixed-post or outreach immunisation operations were partially or completely suspended as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Descriptive statistics were performed and results were expressed as frequencies and proportions of reporting countries.

Data on administered doses of selected vaccines

WHO regional offices collected data on number of vaccine doses administered in 2019 (collected before the pandemic) and 2020 from countries and aggregated these data by month at the national level, with the caveat that not all countries share these data, and completeness of reporting is unknown. Using these data, we assessed the relative difference in the third dose of DTP and first dose of MCV, comparing the number of reported doses administered in 2020 to that in 2019 by country. The mean relative difference was calculated at the regional and global level, weighted by the population of surviving infants in each country.4 Analysis was restricted to countries for which 2020 and 2019 data were available.

Pulse surveys on immunisation activities

Two web-based pulse surveys were done during April 14–24, 2020,5 and June 5–20, 2020,6 to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on routine immunisation services. The surveys were developed by WHO; UNICEF; Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance; Sabin Vaccine Institute's Boost Community; the Johns Hopkins International Vaccine Access Center; and the Global Immunisation Division at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveys were distributed through WHO, UNICEF, National Immunisation Technical Advisory Groups (NITAGs), Boost, Gavi, The Geneva Learning Foundation (TGLF) networks, and TechNet—a network of immunisation professionals, mostly from low-income and middle-income countries. Distribution of the second pulse survey did not occur through the TGLF network, because the timing of this pulse survey and the TGLF network communications did not coincide. The surveys were available in English and French. Responses were collected from Ministries of Health, NITAGs, and country offices of WHO, UNICEF, and Gavi, as well as local health facilities and non-governmental organisations. Notable differences in the second survey compared to the first survey included a distinction between the level of disruption to fixed-post services versus outreach services, and the capture of additional information on vaccination demand and vaccine misinformation. Data sources and methods are presented in detail in the appendix.

Country-specific data are not presented individually in this report because the aim of this report was to present a global picture of the state of routine immunisations. Regional data analyses were done using SAS version 9.4, and the administrative and pulse survey data were analysed using R version 3.6.1.

The analyses were based on secondary data reported directly to the WHO from countries or regions, with no human participant-related data, and hence ethics approvals from institutional review boards were not applicable.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

Information on routine immunisation services was available from a total of 170 countries and territories across the different data sources (table 1).

Table 1.

Number of countries for each data source by month

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulse survey* | |||||||||||||

| AFR | .. | .. | .. | 36 | .. | 34 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | |

| AMR* | .. | .. | .. | 22 | .. | 10 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | |

| EMR† | .. | .. | .. | 14 | .. | 14 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | |

| EUR | .. | .. | .. | 17 | .. | 11 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | |

| SEAR | .. | .. | .. | 8 | .. | 8 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | |

| WPR | .. | .. | .. | 10 | .. | 5 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | |

| WHO regional office reports | |||||||||||||

| AFR | .. | .. | .. | 30 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | |

| AMR‡ | .. | .. | .. | 30 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | |

| EMR | .. | .. | .. | 9 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | |

| EUR | .. | .. | .. | 43 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | |

| SEAR | .. | .. | .. | 11 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | |

| WPR | .. | .. | .. | 0 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | |

| Administrative vaccination data | |||||||||||||

| AFR | |||||||||||||

| DTP3 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 44 | 41 | |

| MCV1 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 44 | 41 | |

| AMR† | |||||||||||||

| DTP3 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 24 | |

| MCV1 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 24 | |

| EMR | |||||||||||||

| DTP3 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| MCV1 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| EUR§ | |||||||||||||

| DTP3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| MCV1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SEAR | |||||||||||||

| DTP3 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| MCV1 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| WPR | |||||||||||||

| DTP3 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| MCV1 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

The number of countries for which data on routine immunisation services were available from the pulse surveys, WHO regional office reports, and administrative vaccination data are included. 170 countries and territories had data from at least one source. The total number of member states in each WHO region was 194 globally, 47 in AFR, 35 in AMR, 21 in EMR, 53 in EUR, 11 in SEAR, and 27 in WPR. The months are from 2020 in the case of the pulse surveys and WHO regional office reports, and from both 2019 and 2020 in the case of the administrative vaccination data. AMR=region of the Americas. AFR=African region. DTP3=third dose of diphtheria–pertussis–tetanus-containing vaccine. EMR=Eastern Mediterranean region. EUR=European region. MCV1=first dose of measles-containing vaccine. SEAR=South-East Asia region. WPR=Western Pacific region.

Includes two non-WHO member states for the purpose of analysis.

Includes one non-WHO member state for the purpose of analysis.

Includes three non-WHO member states for the purpose of analysis.

The WHO European regional office did not have a mechanism to collect these data.

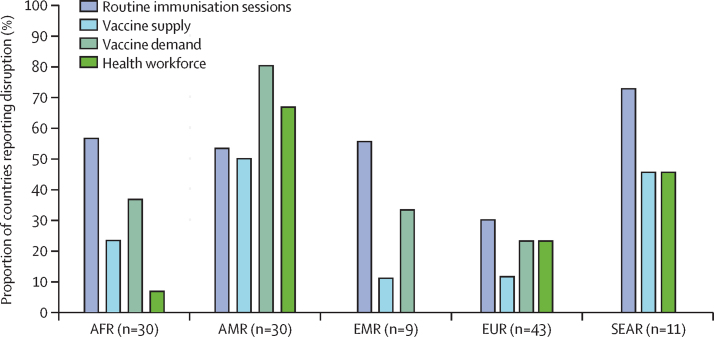

The status of routine immunisation services in April, 2020, was available for 123 countries across five WHO regions. Substantial pandemic-related disruption in immunisation was observed across all WHO regions, with responses indicating varying amounts of interruption to routine immunisation sessions, health workforce availability, vaccine supply, and demand for immunisation services in April, 2020 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion of countries reporting pandemic-related disruption to routine immunisation sessions, health workforce availability, vaccine supply, and demand for immunisation services in April, 2020

Analysis of data collected by WHO regional offices from their respective member states. Indicators not included in regional data-collection instruments might be underestimated. Vaccine demand was not systematically collected for AFR, EMR, EUR, and SEAR. Vaccine supply was not systematically collected for EMR. Health workforce availability was not systematically collected for EMR and EUR. Results for these indicators for these regions may be an underestimate. Data were sourced from WHO regional office reports. WPR was not represented because the data were not available. N represented the total number of countries in the respective region. AMR=region of the Americas. AFR=African region. EMR=Eastern Mediterranean region. EUR=European region. SEAR=South-East Asia region. WPR=Western Pacific region.

In the WHO African region, data were available for 30 of 47 member states. Of those, there were signs of disruption to routine immunisation sessions in 17 (57%) member states, with fixed-post services partially suspended in two countries, and outreach services partially or completely suspended in 17 countries. Reports for seven (23%) of 30 countries indicated challenges with vaccine supply, and 11 (37%) of 30 countries indicated challenges with vaccine demand because of fear of COVID-19 exposure, transportation barriers, and misinformation.

In the WHO region of the Americas, data were available for 27 of the 35 member states and three territories. Disruption to routine immunisation sessions was reported by 16 (53%) of those 30 countries and territories, with complete suspension of immunisation services reported in at least three countries. A reduction in demand for vaccination services was observed in 24 (80%) of 30 countries, and 15 (50%) of 30 countries reported challenges with obtaining vaccine supplies. For 20 (67%) of 30 countries and territories, limitations in availability of health workforce were noted, attributed to staff illness, confinement policies, and diversion to COVID-19-related activities.

Of the 21 member states in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean region, nine had data available. In at least five (55%) of those nine countries, there were signs of disruption to routine immunisation sessions, perceived reductions in demand for vaccination services in at least three (33%) of nine countries, and vaccine supply challenges among at least one (11%) of nine countries.

In the WHO European region, 43 of 53 member states had data available, and of those 13 (30%) had data suggesting disruption to routine immunisation sessions. In at least ten (23%) of 43 countries, there were indications of reduced demand for immunisation services, and reduced availability of the health workforce. At least five (12%) of 43 countries reported challenges with vaccine supply.

Disruption to routine immunisation sessions was noted in eight of the 11 member states in the WHO South-East Asian region. Although specific information on demand for vaccination services was not available, there were indications of vaccine supply issues and reduction in health workforce availability in five (45%) of 11 countries.

In the WHO Western Pacific region, disruptions to routine immunisation services and suspension of immunisation outreach activities were reported in some member states.7 Disruptions were attributed to decreased availability of immunisation workforce because of reassignment to pandemic response activities, severe travel restrictions, and reductions in vaccine supplies.7

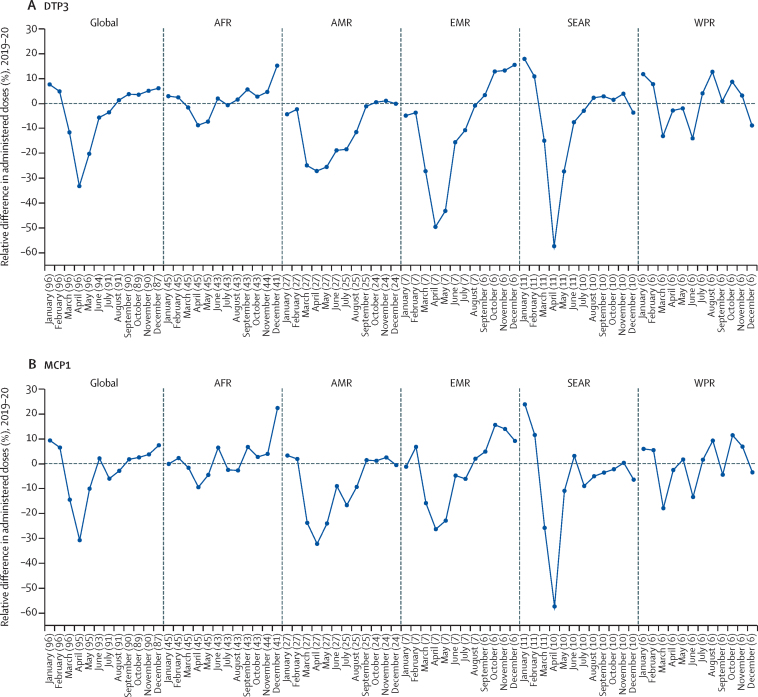

Paired 2019–20 monthly data were available from January to December for selected countries from all WHO regions with the exception of Europe. Across all WHO regions for which data were available, there was a marked decline in the number of DTP3 and MCV1 doses administered in the first half of 2020 compared with 2019, with a monthly weighted mean relative difference as great as 33% globally for DTP3 (figure 2). Most countries in the WHO regions reached their lowest number of administered vaccines doses between April and May, 2020, and early signs of recovery were observed by June, 2020. A drastic decline was observed in the South-East Asia region and the Eastern Mediterranean region, where an average of 57% and 50% fewer doses of DTP3, respectively, were administered in April, 2020, than in April, 2019. A smaller degree of decline of 9% was observed in the African region.

Figure 2.

Weighted mean relative difference in DTP3 and MCV1 administered from January, 2020, to December, 2020, compared globally with 2019 and by WHO Region

Mean relative difference in DTP3 (A) and MCV1 (B) administered in 2020 compared with 2019, weighted by surviving infants. Analysis of administrative data of vaccine doses given, and data from the UN Population Division for surviving infants by country or region. Numbers in parentheses indicate number of countries with available data for the respective month. AMR=region of the Americas. AFR=African region. EMR=Eastern Mediterranean region. EUR=European region. SEAR=South-East Asia region. WPR=Western Pacific region. DTP3=third dose of diphtheria–pertussis–tetanus-containing vaccine. MCV1=first dose of measles-containing vaccine.

For the first pulse survey done in April, 2020, 801 responses were recorded from individuals working at the national and subnational level from 107 countries and territories. Results revealed the widespread impact of the COVID-19 pandemic across the globe. For 68 (64%) of 107 countries represented in the survey, available data indicated that routine immunisation services had been disrupted or completely suspended during the early months of the pandemic.

The second pulse survey from June, 2020, generated 260 national and subnational level respondents from 82 countries and territories. A total of 67 unique countries and territories had national-level respondents; however, the number with available data varied by question. In 52 (85%) of 61 countries, vaccination services at the national level were perceived to be lower in March, 2020, and April, 2020, than in January, 2020, and February, 2020. By May, 2020, vaccination services appeared to improve in only 11 (18%) of 61 countries compared with those seen in the previous month. Fixed-post vaccination services were described as disrupted or completely suspended in 27 (44%) of 62 countries (table 2). Outreach services were operating as usual in only 11 (17%) of 65 countries, whereas they were perceived to be disrupted or completely suspended in 45 (69%) of 65 countries. In the remaining nine (14%) of 65 countries, outreach services were not considered applicable. The leading causes of disruption of immunisation services as reported by national and subnational respondents were absence of personal protective equipment for health-care workers (49%), decreased availability of health-care workers (43%), and travel restrictions (40%). Approximately a quarter (24%) of respondents indicated insufficient vaccines or vaccine-related supplies.

Table 2.

Countries indicating disruption to routine immunisation services in May, 2020, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic

| Global | AFR | AMR | EMR | EUR | SEAR | WPR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed-post immunisation services | |||||||

| No disruption | 35 (56%) | 15 (56%) | 1 (25%) | 8 (67%) | 6 (75%) | 2 (29%) | 3 (75%) |

| Disrupted | 26 (42%) | 12 (44%) | 3 (75%) | 3 (25%) | 2 (25%) | 5 (71%) | 1 (25%) |

| Suspended | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Total | 62 (100%) | 27 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 12 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 4 (100%) |

| Outreach services | |||||||

| No disruption | 11 (17%) | 3 (10%) | 1 (25%) | 1 (8%) | 2 (22%) | 2 (29%) | 2 (50%) |

| Disrupted | 38 (58%) | 21 (72%) | 3 (75%) | 6 (50%) | 4 (44%) | 3 (43%) | 1 (25%) |

| Suspended | 7 (11%) | 4 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (17%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (14%) | 0 (0%) |

| Not applicable | 9 (14%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (25%) | 3 (33%) | 1 (14%) | 1 (25%) |

| Total | 65 (100%) | 29 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 12 (100%) | 9 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 4 (100%) |

| Vaccine demand | |||||||

| No disruption | 17 (27%) | 3 (11%) | 1 (25%) | 3 (27%) | 4 (44%) | 4 (67%) | 2 (50%) |

| Disrupted | 45 (73%) | 25 (89%) | 3 (75%) | 8 (73%) | 5 (56%) | 2 (33%) | 2 (50%) |

| Total | 62 (100%) | 28 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 11 (100%) | 9 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 4 (100%) |

Data are from the second pulse survey. The number and proportion of countries (represented by national-level respondents to the pulse survey) that reported disruption to the supply of (fixed-post and outreach immunisation services) and demand for vaccines are shown. A single status for disruption in a country was calculated on the basis of the majority of responses from those working at the national level from that country. Additional countries with subnational respondents only are not represented here. The number of countries with available data from national-level respondents varied by question. The total number of member states in each WHO region was 194 globally, 47 in AFR, 35 in AMR, 21 in EMR, 53 in EUR, 11 in SEAR, and 27 in WPR. AMR=region of the Americas. AFR=African region. EMR=Eastern Mediterranean region. EUR=European region. SEAR=South-East Asia region. WPR=Western Pacific region.

Catch-up vaccination plans for people who missed their vaccination because of the pandemic were reported by 77% of respondents. Recovery activities included enhanced outreach services (64%), expanded fixed-post services (59%), periodic intensification of routine immunisation8 or child health days (40%), and supplementary immunisation activity (28%). 74% of respondents indicated that mechanisms were in place to track rumours and misinformation, primarily using mainstream media, digital media, and community reporting. By June, 2020, 67 (26%) of the 260 respondents noted that guidance documents on safe immunisation practices in the context of COVID-19 were available across 25 countries in 12 languages, with their main source of information drawn from the National Ministries of Health, WHO, and UNICEF.

Discussion

This report reflects the deep impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on routine immunisation services worldwide during the first year of the pandemic and adds qualitative information on the many factors affecting routine vaccination. Gleaned from three separate global data sources, comprising reports from WHO regional offices, administered vaccine doses from 2019 and 2020, and a two-part pulse survey from early 2020, this distillation of data representing 170 countries and territories revealed a precipitous drop in immunisation services during the first half of 2020. The consistency of the findings on decreased vaccination services across data sources and regions highlights the global pervasiveness of pandemic-related disruption of essential health services.9, 10, 11

Amid COVID-19 mitigation measures, systems and strategies that rely on mobility have been disproportionately affected. Outreach services are commonly used in many low-income and middle-income countries, and entail regular visits to deliver routine vaccination services to communities, particularly those with poor access to health facilities. A consistent finding from both WHO regional data sources and the pulse surveys is the greater disruption seen in outreach services than fixed-post vaccinations across regions or countries where the two approaches of routine immunisation services were reported separately. Disparities in disruption merit deep consideration of coverage inequities heightened by the pandemic, given that vulnerable communities predominantly served by outreach services, and often also more reliant on mass supplementary immunisation activities, are more likely to experience service disruptions and are also the last to recover, leaving these populations at higher risk of vaccine-preventable diseases for years to come.12

Although these data indicate a partial resumption of services, the urgency for efficient catch-up immunisation approaches needs emphasis. Most countries have endeavoured to get coverage back to baseline, but identifying vulnerable children who have been missed during these disruptions, and providing targeted catch-up services within these areas with poor or no coverage, will be crucial for full recovery. Although some high-income countries did intensify existing health system approaches to accelerate catch-up vaccination,13, 14 governments and communities will still need innovative and impactful strategies to ensure that people who missed vaccines catch up and to return vaccination coverage to levels attained before the COVID-19 pandemic, and even higher levels.

Chief among novel approaches to recover and rebuild, is a need to shift the thinking from equity of coverage to equity of resilience. As an illustration, similar vaccination coverage in two individual communities might belie true health equality if one community is more vulnerable to disruption and less able to recover from serious health system incursions. Health system resilience is measured by the ability of a health system to effectively respond to crises, and to sustain core activities to maintain the health of its population during the crises and beyond.15, 16

Immunisation gaps leading to accumulation of children who are unvaccinated and susceptible to vaccine-preventable diseases, can lead to a higher burden of disease than previously, and excess deaths.17 Two diseases that the world has been aspiring to eradicate or eliminate are of particular concern: polio and measles infections might stage a comeback as immunisation campaigns and routine services were paused during the pandemic crises.18, 19, 20 The persistence of polio in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and the increase in circulating vaccine-derived polio virus, has been a warning call for intensifying efforts for control despite the coronavirus pandemic.21, 22 From 2017 onwards, measles vaccine coverage was strained by inequitable distribution and rising vaccine hesitancy, leading to the highest-ever reported number of measles deaths in 2019 within the past two decades.23 Experiences from past epidemics, such as the west African Ebola disease outbreak in 2014–15, when suspension of vaccination programmes and decrease in vaccination coverage resulted in more deaths because of measles than of Ebola, holds poignant lessons for maintaining vaccinations during severe crises.24, 25 A risk–benefit analysis of reopening immunisation clinics during the pandemic for countries in Africa found that for every death attributable to COVID-19 disease acquired at the immunisation clinic, 84 deaths from vaccine-preventable diseases could be prevented, providing justification for prioritisation of immunisation services.26

As countries learned to adapt to the pandemic risk by adopting safe practices for infection control and prevention, including procuring personal protective equipment and retraining the health workforce, partial recovery from immunisation disruption was enabled. However, these adaptations were accompanied by strikingly higher costs to immunisation programmes in low-income and middle-income countries.27 An analysis in Tanzania and Indonesia indicated that the cost of delivering immunisation through outreach services could increase by up to 129% of baseline costs, with due consideration given to changes to the health workforce and increased physical distancing measures.28 The economic impact of these pandemic risk-mitigation measures is yet to materialise fully, because how countries can sustain these added costs remains uncertain, and programmes remain vulnerable to declines in health system financing.

The data presented here reveal trends suggestive of early glimpses of resumption of vaccination services across the globe. WHO disseminated interim guidelines for maintaining immunisation activities as early as March, 2020,29 followed by national guidelines developed in several countries of WHO regions.30, 31 Adopting a systems-thinking approach that integrates a holistic understanding of COVID-19 disease trends, pandemic mitigation measures, and childhood immunisation could facilitate recovery.32 Innovative methods were used by countries to boost efforts to resume immunisation services safely.33 Having an appointment-based system to avoid overcrowding, using social media and modified service hours, and offering immunisation services in strategic places such as marketplaces, pharmacies, social or cultural centres, drive-through immunisation services, along with large-scale training of health-care workers using webinars were strategies that were in place by June, 2020.7 Vaccine misinformation is a challenge, particularly in the era of the pandemic, and can form major barriers for routine vaccination.34 Recognising the global nature of the crisis, world agencies have stepped forward to respond to the impact of the pandemic on immunisation programmes. Gavi's adaptation of its 5.0 strategy for 2021–25 by extending targeted support to countries in need is expected to forestall the backsliding of the immunisation programme performance of these countries because of COVID-19.35

Caution is needed while interpreting the data presented in this report because of several limitations. Data sources represented different points in time, and are likely to reflect varying pandemic severity. In comparison with other data sources, the data on administered vaccine doses were the most objective; however, data availability varied by country, month, and vaccine antigen. From a data-quality standpoint, the data on 2019 monthly administered doses were likely to be more complete than the monthly data from 2020, given that 2019 data were obtained after finalisation of data collection, whereas the 2020 data were collected in real time, pending verification of the completeness of subnational reporting. Data collected by WHO regional offices differed in structure and format. Data might be misinterpreted when abstracted from free text, or underestimated in instances in which indicators were not included as part of the data-collection instruments of the regions. Additionally, the availability of data and information varied for member states, with no data available for several countries; thus, the reported results do not reflect the full scope of the situation in each region. Data from the pulse surveys were limited by the biases attributable to self-reporting and self-selection of respondents, and the absence of ratification by official national sources. There was uneven representation from countries, as illustrated by a comparably greater number of respondents from African countries than other WHO regions resulting in potential skewing of results. Overall, the pulse survey was designed to obtain a snapshot of the global impact of COVID-19 on immunisation services at the early stages of the pandemic, without intention to replace regional or national immunisation data-collection efforts.

This report provides a comprehensive view of global disruptions in routine immunisation. Findings suggestive of resumption of immunisation services underscore the need to accelerate these steps to achieve the target of complete recovery. In this light, there are several actions that can help propel progress forward (figure 3). First, prioritisation and implementation of catch-up vaccination strategies is crucial. Special emphasis is to be given to those communities that were at higher risk before the pandemic, such as communities with children who are not immunised or defined as zero dose36 (operationally defined as children 12 months or older who have not received the first dose of a DTP vaccine) with several risk factors for poor health outcomes, as they will be the most vulnerable to outbreaks. Second, strengthening information systems, particularly routine administrative systems, will provide a platform for access to timely data to inform response to immunisation disruptions and to identify and vaccinate missed children. Third, paying close attention to potential cost implications of implementing COVID-19 mitigation plans with immunisation programmes and mobilisation of additional resources would be needed to sustain early gains of immunisation services resumption. Fourth, countries and global agencies need to be particularly mindful during the COVID-19 vaccine rollout to maintain essential immunisation services despite the inevitable repurposing of human and financial resources, and be opportunistic in introducing or enhancing digital immunisation platforms to support childhood immunisation delivery and real-time monitoring. Finally, incorporating health-system resilience features when restructuring the health programmes and establishing best practices to ensure strong primary health care would more efficiently address future pandemics and benefit societal health.37

Figure 3.

Urgent actions for sustaining immunisation activities globally

There is a clear path to sustaining the hard-won gains of vaccines once the threat of the COVID-19 pandemic begins to recede; the challenges and strategies to achieve this mission are outlined in the global vision document, Immunisation Agenda 2030.38 Governments, institutions, the private sector, communities, and global agencies have the responsibility to work together to achieve this mission.

Data sharing

All data used in this study are available either in the manuscript and appendix, in publications referenced in the study, or through secondary data sources described in the manuscript. As data collection efforts took place early in the pandemic, some country-level data were not collected under the WHO policy on data sharing for member states, hence only aggregated data are available at regional levels.

Declaration of interests

AS, KC, CP, and CW are sponsored in part by the US Agency for International Development. The rest of the authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of WHO regional immunisation advisors and monitoring and evaluation focal points who worked tirelessly to collect and compile much of the data presented here. The authors also thank Tim Trueman from UNICEF for analysis support of the pulse survey data. This study was made possible partially by the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and MOMENTUM Country and Global Leadership, led by Jhpiego and partners. The content of the Article does not necessarily reflect the views of those at the WHO, USAID, or the US Government.

Contributors

MCD-H, AL, MG-D, AS, IM, and SVS developed the conceptual framework. MCD-H, IM, CP, and KC developed the data collection instruments and reporting structure from countries. CP, KC, and JW extracted, cleaned, and catalogued data, did the data analysis, and developed graphs. AS, KC, and CP wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MCD-H, SVS, CW, HWR, IM, MG-D, KLO'B, and AL provided critical review, meaningful comments, and revisions. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Anita Shet, Email: ashet1@jhu.edu.

Ann Lindstrand, Email: lindstranda@who.int.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.WHO At least 80 million children under one at risk of diseases such as diphtheria, measles and polio as COVID-19 disrupts routine vaccination efforts, warn Gavi, WHO and UNICEF. May 22, 2020. https://www.who.int/news/item/22-05-2020-at-least-80-million-children-under-one-at-risk-of-diseases-such-as-diphtheria-measles-and-polio-as-covid-19-disrupts-routine-vaccination-efforts-warn-gavi-who-and-unicef

- 2.WHO UNICEF immunization coverage estimates, 2020 revision. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/immunization/immunization-coverage/wuenic_notes.pdf?sfvrsn=88ff590d_6

- 3.Causey K, Fullman N, Sorensen RJD, et al. Estimating global and regional disruptions to routine childhood vaccine coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: a modelling study. Lancet. 2021;398:522–534. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01337-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown DW, Burton AH, Gacic-Dobo M, Karimov R. An introduction to the grade of confidence used to characterize uncertainty around the WHO and UNICEF estimates of national immunization coverage. Open Pub Health J. 2003;6:73–76. [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO Global Immunization News (GIN) March–April, 2020. Understanding the disruption to programmes through rapid polling. https://www.who.int/immunization/GIN_March-April_2020.pdf

- 6.WHO Global Immunization News (GIN) June 2020. Immunization and COVID-19. Second pulse poll to help understand disruptions to vaccination and how to respond. https://www.who.int/immunization/GIN_June_2020.pdf

- 7.WHO Meeting of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization, October 2020. Conclusions and recommendations. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2020;95:585–607. [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO Periodic intensification of routine immunization: lessons learned and implications for action. https://www.who.int/immunization/programmes_systems/policies_strategies/piri_020909.pdf

- 9.WHO Pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Interim report. Aug 27, 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-EHS_continuity-survey-2020.1

- 10.Global Financing Facility New findings confirm global disruptions in essential health services for women and children from COVID-19. Sept 18, 2020. https://www.globalfinancingfacility.org/new-findings-confirm-global-disruptions-essential-health-services-women-and-children-covid-19

- 11.Lassi ZS, Naseem R, Salam RA, Siddiqui F, Das JK. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on immunization campaigns and programs: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:988. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18030988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bigouette JP, Wilkinson AL, Tallis G, Burns CC, Wassilak SGF, Vertefeuille JF. Progress toward polio eradication worldwide. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1129–1135. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7034a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Middeldorp M, van Lier A, van der Maas N, et al. Short term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on incidence of vaccine preventable diseases and participation in routine infant vaccinations in the Netherlands in the period March–September 2020. Vaccine. 2021;39:1039–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacDonald NE, Comeau JL, Dubé È, Bucci LM. COVID-19 and missed routine immunizations: designing for effective catch-up in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2020;111:469–472. doi: 10.17269/s41997-020-00385-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kruk ME, Ling EJ, Bitton A, et al. Building resilient health systems: a proposal for a resilience index. BMJ. 2017;357 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tumusiime P, Karamagi H, Titi-Ofei R, et al. Building health system resilience in the context of primary health care revitalization for attainment of UHC: proceedings from the Fifth Health Sector Directors' Policy and Planning Meeting for the WHO African Region. BMC Proc. 2020;14(suppl 19):16. doi: 10.1186/s12919-020-00203-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberton T, Carter ED, Chou VB, et al. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e901–e908. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30229-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Din M, Asghar M, Ali M. Delays in polio vaccination programs due to COVID-19 in Pakistan: a major threat to Pakistan's long war against polio virus. Pub Health. 2020;189:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhong Y, Clapham HE, Aishworiya R, et al. Childhood vaccinations: hidden impact of COVID-19 on children in Singapore. Vaccine. 2021;39:780–785. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts L. Why measles deaths are surging and coronavirus could make it worse. Nature. 2020;580:446–447. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Din M, Ali H, Khan M, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on polio vaccination in Pakistan: a concise overview. Rev Med Virol. 2020;31 doi: 10.1002/rmv.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmad S, Babar MS, Ahmadi A, Essar MY, Khawaja UA, Lucero-Prisno DE. Polio amidst COVID-19 in Pakistan: what are the efforts being made and challenges at hand? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;104:446–448. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mapping routine measles vaccination in low- and middle-income countries. Nature. 2021;589:415–419. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03043-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi S, Metcalf CJ, Ferrari MJ, et al. Reduced vaccination and the risk of measles and other childhood infections post-Ebola. Science. 2015;347:1240–1242. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brolin Ribacke KJ, Saulnier DD, Eriksson A, von Schreeb J. Effects of the west Africa ebola virus disease on health-care utilization: a systematic review. Front Public Health. 2016;4:222. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abbas K, Procter SR, van Zandvoort K, et al. Routine childhood immunisation during the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa: a benefit-risk analysis of health benefits versus excess risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e1264–e1272. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30308-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Portnoy A, Resch S. Estimating the additional cost for maintaining facility-based routine immunization programs in the context of COVID-19. 2020. http://immunizationeconomics.org/recent-activity/2020/7/23/covid-19-increases-cost-to-deliver-immunization

- 28.Moi F, Banks C, Boonstoppel L. The cost of routine immunization outreach in the context of COVID-19: estimates from Tanzania and Indonesia. July 20, 2020. https://thinkwell.global/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Cost-of-outreach-vaccination-in-the-context-of-COVID-19-20-July-2020.pdf

- 29.WHO Guiding principles for immunization activities during the COVID-19 pandemic: interim guidance. March 26, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331590

- 30.WHO How WHO is supporting ongoing vaccination efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic. July 14, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/how-who-is-supporting-ongoing-vaccination-efforts-during-the-covid-19-pandemic

- 31.Masresha BG, Luce R, Jr, Shibeshi ME, et al. The performance of routine immunization in selected African countries during the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37(suppl 1):12. doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.37.1.26107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adamu AA, Jalo RI, Habonimana D, Wiysonge CS. COVID-19 and routine childhood immunization in Africa: leveraging systems thinking and implementation science to improve immunization system performance. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;98:161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dixit SM, Sarr M, Gueye DM, et al. Addressing disruptions in childhood routine immunisation services during the COVID-19 pandemic: perspectives and lessons learned from Liberia, Nepal, and Senegal. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.03.18.21252686. published online March 23. (preprint). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dror AA, Eisenbach N, Taiber S, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35:775–779. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gavi. the Vaccine Alliance Strategy and implications of Covid-19: Gavi 4.0 progress, challenges and risks and update on Gavi 5.0 operationalisation. Report to the board. June 24–25, 2020. https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/board/minutes/2020/24-june/03%20-%20Strategy%20and%20implications%20of%20COVID-19.pdf

- 36.Fulkar J. The zero-dose child: explained. April, 2021. https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/zero-dose-child-explained

- 37.Blanchet K, Alwan A, Antoine C, et al. Protecting essential health services in low-income and middle-income countries and humanitarian settings while responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.WHO Immunization agenda 2030. A global strategy to leave no one behind. http://www.immunizationagenda2030.org/ [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are available either in the manuscript and appendix, in publications referenced in the study, or through secondary data sources described in the manuscript. As data collection efforts took place early in the pandemic, some country-level data were not collected under the WHO policy on data sharing for member states, hence only aggregated data are available at regional levels.