Abstract

Family members provide significant amounts of unpaid care to aging, chronically ill, and disabled persons in their homes. They often do this with little education or support and commonly report feeling overwhelmed and stressed. Providing education and support to family caregivers has demonstrated benefit on the health and well-being of the caregiver and care-receiver. However, because “caregiver” is not a reimbursable category in health care, caregiver interventions need to be delivered in a cost-efficient way. Technology-delivered and self-administered intervention models are increasingly being recommended as a pragmatic way to support aging families in our communities. This paper outlines the redevelopment of two behavioral interventions to an exclusively online delivery. This case-study analysis presents a model for community-engaged intervention research practices, which have the potential to create interventions that are more sustainable and more likely to be implemented than those designed and tested with more traditional research methodology.

Keywords: family caregivers, behavioral interventions, online/mobile delivery, community-engaged research

Approximately 53 million, or one in five, Americans provide unpaid financial, medical, social, and instrumental support to aging, chronically ill, and disabled family members (NAC & AARP, 2020). On average, caregivers spend 24 hours per week providing care, with the role lasting 4 years (NAC & AARP, 2020). Informal, family-delivered support is key to keeping aging persons and those with disability in their homes and community. Without family caregivers, the economic costs to provide long term supports and services to an aging population would increase exponentially. We estimate the annual economic value of unpaid family caregiving to be more than $800 billion (i.e., 53 million family caregivers, providing an average of 24 hours of care per week, at a value of $12.32 per hour, the average rate paid to a certified nursing assistant); this estimated value rivals US government expenses to Medicare ($750 billion in 2018) or Medicaid ($597 billion in 2018) (CMS, 2015). As our population ages (Roberts, Ogunwole, Blakeslee, & Rabe, 2018) and as our society increasingly values the delivery of home- and community-based health care for aging and disabled persons (Weissert, Cready, & Pawelak, 2005), our reliance on the care and services provided by unpaid family caregivers is essential to the overall health and economic prosperity of our country.

While family caregivers may find great value and meaning in providing care and support to their loved ones (Doris, Cheng, & Wang, 2018; Kramer, 1997), many also report feeling unprepared, unsupported, and strained by the caregiving role (Kim & Schulz, 2008; Neena & Reid, 2002; Schulz, O’Brien, Bookwala, & Fleissner, 1995). Family caregiving often comes at a cost to personal health and well-being (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003), with one in four reporting worsening health and increased stress due to their caregiving role (NAC & AARP), 2020). Caregiver burden can also have negative effects on patient outcomes, including increased risk for mortality and institutionalization (Lwi, Ford, Casey, Miller, & Levenson, 2017; Whitlatch, Feinberg, & Stevens, 1999). Family caregivers have been dubbed both the “invisible health care workers” and “hidden patients” within our communities (Applebaum, 2015; Roche & Palmer, 2009).

As part of a person- and family-centered health care model, there is increasing recognition of the importance of supporting and educating family caregivers as a way to reduce their feelings of stress and burden (Harvath et al., 2020). Reducing caregiver stress is associated with positive outcomes for both the care recipient and the family caregiver (Young et al., 2020). A number of promising behavioral interventions have been developed over the past several decades (see Benjamin Rose’s database for evidence-based caregiver interventions, https://bpc.caregiver.org). Interventions often use in-person counseling, peer facilitation, and/or support groups to provide education, skill-building, or to address the psycho-emotional needs of family caregivers. While caregivers often benefit from these interventions when tested in controlled research settings, many of the existing interventions have not been implemented in community settings due to having limited accessibility, being too resource-intensive, and because caregiving remains a largely non-reimbursable category in traditional health care financing (National Academies of Science, 2016).

Self-administered interventions using mobile technologies have emerged as a promising way to deliver support and education to family caregivers that is both cost-efficient and able to reach a wide range of diverse family caregivers, including those who are geographically or situationally isolated (Chi & Demiris, 2015; Lindeman, Kim, Gladstone, & Apesoa-Varano, 2020). While not all older adults have the technology, skills, or interests in engaging with online and virtual self-help tools, the notion that older adults cannot or will not use technology should be considered outdated. Estimates show that a majority of older adults (age 65+) currently have access to computers and high-speed internet within their homes (Anderson, 2019). Access to and comfort using online technology will continue to increase, as mobile delivery becomes more prevalent through telehealth initiatives and with the aging of the next generations who have grown up in the age of internet technology. While online delivery cannot replace the personal connection of in-person therapy or the camaraderie that emerges from a traditional support group, the benefits of being able to support family caregivers where they are and when they are available are substantial (i.e., family caregivers may not have respite to attend an in-person support group meeting or may only find time to participate at 3am). Furthermore, the cost-efficient nature of online delivery outweighs the antiquated notion that older adults cannot or will not use computers or internet delivered interventions (Parker, Jessel, Richardson, & Reid, 2013).

Thanks, in part, to recent priorities and special interests from research funders such as National Institute on Aging (e.g., Milestone 13.I, NIA National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Care & Caregivers), many of the existing family caregiver interventions are now being redeveloped with an aim to be self-administered using online and mobile technologies (Onken & Shoham, 2015). As outlined in the stage-model for the development and evaluation of behavioral interventions (Onken, Carroll, Shoham, Cuthbert, & Riddle, 2014), although interventions may demonstrate efficacy in a controlled research setting, prior to demonstrating effectiveness at a community level there is often a need for redesign and/or redevelopment (Chambers, 2019). Implementation scholars are increasingly using community engagement (Ahmed & Palermo, 2010; Wallerstein & Duran, 2010) as a way to ensure greater translation and scalability of research-based interventions to practice.

Community-engaged methods emphasize a partnership between academic researchers and community-based stakeholders (Mikesell, Bromley, & Khodyakov, 2013). Stakeholders typically include anyone who has an interest in and/or is affected by the outcome of a project. For example, in a study aiming to develop an intervention for persons with spinal cord injury, a stakeholder might include the person with spinal cord injury, clinicians or therapists who work with individuals with spinal cord injury, clinic or hospital administrators, and/or family members of the person with spinal cord injury. Stakeholder roles may range from community informed (community as advisor), community involved (community as collaborator), and community directed (community as leader). Community engagement represents “a shift away from an expert model of delivering university knowledge to the public and toward a more collaborative model in which community partners play a significant role in creating and sharing knowledge to the mutual benefit of institutions and society” (Weerts & Sandmann, 2008, pg 74). This philosophical shift helps ensure that an intervention is accessible and scalable to real-world settings, while meeting the needs of diverse people in those communities, thereby increasing the likelihood of eventual and widespread implementation and dissemination at the community level. Despite its value, there exists little consensus on how to do community-engaged intervention research (Cargo & Mercer, 2008).

The purpose of this case-study analysis is to provide an overview of the community engagement strategies we used during the redevelopment of two caregiver-focused interventions for online delivery. The two interventions featured here are called SupportGroove and Time for Living and Caring, TLC. The details of each intervention can be found in previous research publications (Lund et al., 2014; Terrill et al., 2018). In this manuscript, we (the investigators and intervention developers) focus on describing the community-engaged methods that each research team adopted when we redeveloped the interventions as self-administered and technology-delivered interventions.

Method

Intervention Description

SupportGroove

SupportGroove is a dyadic behavioral intervention to support persons with chronic neurological conditions and their family caregivers (specifically, spouses or partners). Originally developed as a self-administered pen-and-paper intervention for couples coping with stroke, the 8-week intervention protocol included an in-person training session at an outpatient clinic, after which couples completed the intervention on their own, at home, using a printed activity booklet describing activities and a tracking calendar to write down the completion of activities. The positive psychology-based activities were completed first as individuals and then as a couple, and included common exercises associated with improved well-being, such as expressing gratitude, practicing acts of kindness, fostering relationships, savoring, and finding meaning (Bolier et al., 2013). Weekly phone calls from a research assistant reminded participants to complete activities and send in the tracking sheets by mail.

Time for Living and Caring (TLC)

Time for Living and Caring (TLC) is an intervention for family caregivers, intended to help them use respite. Respite, defined as an intentional time-away or break from caregiving responsibilities, has been identified as the most needed and desired support for family caregivers, yet the benefits of respite have been mixed in previous research (Zarit, Bangerter, Liu, & Rovine, 2017). The TLC intervention uses goal-setting and goal-review techniques to help family caregivers plan and achieve a more consistent and fulfilling respite, thereby hopefully reducing caregiver burden and maintaining overall health and well-being. Originally designed, the TLC intervention relied on trained facilitators and up to 15–20 home visits or phone calls with each family caregiver.

While initial pilot work for SupportGroove and TLC showed the promise and importance of each intervention (Lund et al., 2014; Terrill et al., 2018), we realized that the use of trained facilitators to achieve high levels of standardized delivery and treatment fidelity (critically important in intervention research) minimized the potential for these interventions to be implemented or disseminated to community practice. That is, the interventions as originally designed were not sustainable or practical in real-world settings. SupportGroove and TLC needed to be redeveloped.

Community-Engaged Methods for Intervention Development

During the redevelopment phase, SupportGroove and TLC shared the same end-goal: to create a version of the existing intervention that maintained the primary mechanisms and features of the original intervention model, but that could become fully self-administered using online technologies, reducing a reliance on traditional research-trained facilitators and in-person sessions. While both teams adopted a similar commitment to community-engaged methods as a way to re-imagine the essential features and functions of the interventions, each team employed slightly different community engagement practices, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition and Description of Community-Engaged Methods Used to ReDevelop TLC and Support Groove as Technology-Delivered Interventions

| FEASIBILITY |

Needs Assessment A process often used by organizations to determine priorities and to allocate resources. It is considered an early and essential stage in developing services for persons or population. |

SupportGroove conducted a mixed-method needs assessment during the initial pilot test of the original pen-and-paper intervention. It included surveys and interviews with 34 dyads (family caregiver + care-recipient), plus key stakeholder groups (31 care-recipients, 16 family caregivers, five clinicians). The goal was to establish need and best approach for an intervention supporting care-recipients and family caregivers after traditional rehabilitation services. Findings showed accessibility-related barriers to participating and a preference for online tools to facilitate intervention delivery. |

|

Community Engagement Studios Small-group, facilitated discussions that bring researchers, community members, and stakeholders into a discussion about research (Joosten et al., 2015) |

TLC contracted with the “Community Collaboration & Engagement Team” at their university to recruit participants and to facilitate two studios. One was with current and former family caregivers (n=12). The other was with respite service providers from the community (n=8). Each group highlighted diverse interests representing a range of racial-ethnic and socioeconomic statuses. Researchers worked with facilitators ahead of time to outline the questions we wanted to know, but remained observers during the studio itself. The goal was to receive immediate feedback about the feasibility of online respite planning tools. Stakeholder feedback was incorporated into the grant proposal used to fund the redevelopment costs of the TLC intervention. | |

| DEVELOPMENT & DESIGN |

Design-Box Technique used in the gaming industry to generate ideas and pitches for new products. It is an iterative conversation that focuses on four “walls” or constraints to the development of new products: 1) technology, 2) audience, 3) aesthetics, and the 4) question or problem to be solved. (Altizer Jr et al., 2017) |

The SupportGroove team (including researchers and technical designers) hosted four Design-Box meetings with key stakeholders including four content experts (clinicians and therapists specializing in adaptive equipment and technology) and nine intended end-users (individuals with physical and/or cognitive disability, family caregivers). The goal was to identify the needs and key elements of the app-version of the SupportGroove intervention. The collaborative and iterative conversations allowed the design team to incorporate stakeholder feedback into the features and functionality of the prototype app. |

|

Community Advisory Board (CAB) CABs serve in an advisory role to researchers, often providing insight about the implementation of research protocols in diverse communities. The composition of a CAB should reflect the diverse needs and interests of a project’s target demographics, and provide key stakeholders who are invested in the research being conducted (Newman et al., 2011) |

The TLC team created a 12-person CAB, comprised of community leaders representing diverse population subgroups, current and former family caregivers, service providers currently working with family caregivers, and a representative from the design team. The CAB met 10 times over the course of the 18-month development period, each time providing specific feedback to the researchers and design team. The “Community Collaboration and Engagement Team” at their university arranged and facilitated each meeting, provided detailed summary notes of the discussions, and compensated each consultant for their time. |

Following best practices for intervention research (Bartholomew et al., 2006), both teams needed to first confirm the feasibility and potential usability of an online intervention with the end-user population. SupportGroove collected feasibility data through a formal “needs assessment,” using a mixed-method design (i.e., survey + follow-up interviews), which was embedded in the pilot test of the original pen-and-paper version of the intervention. The initial idea to translate SupportGroove into an “app” came directly from this feedback, illustrating that community stakeholders can sometimes directly shape and direct research priorities. Conversely, the TLC research team began knowing that they wanted to create a technology-delivered form of their intervention. To affirm the feasibility of an online approach, the TLC team participated in a series of “community engagement studios” to explicitly hear from two groups of stakeholders about their interests in an online tool and to elicit specific ideas to make it most usable and useful for family caregivers in the community. Insight from the studios became an important part of a grant proposal that funded the redevelopment of the TLC intervention into a “virtual coach.” Grant reviewers praised the use of the community engagement studios as novel and important preliminary work underlying the proposal.

Next, as funding was secured to create technology-delivered versions of each intervention, we continued to involve community stakeholders as collaborators and consultants during the design process. TLC created a “Community Advisory Board” that met 10 times over the course of the design and build process and served as paid consultants/advisors to the research and design team. Each of the 10 sessions focused on specific features, text, or imagery that would be used in the final intervention tools. SupportGroove used a “Design Box” strategy to ensure that the technology being created would match the needs and interests of the people it intended to serve (Terrill et al., 2019). In both methods, stakeholders became key participants in an iterative design process used to develop the online tools and resources. Stakeholders were particularly influential in suggesting features and language that would enhance the usability for diverse populations, including those who were not as comfortable with online tools.

Finally, we conducted user-testing, which is a necessary step in the development of technology-delivered interventions. Both teams employed user-testers that reflected the demographic characteristics of the interventions’ intended audiences, in addition to the random young adults who commonly do user-testing for new apps. SupportGroove employed a split design, where we got significant feedback from five dyads, fixed those issues, and then repeated the user-testing with another five dyads. The software and design teams commented that many of the common usability and accessibility issues that come up during user-testing had already been addressed, likely because of the involvement of stakeholders during the initial stages of prototyping and development. As an example, SupportGroove stakeholders pinpointed accessibility issues in a very early prototype, which helped identify design solutions that were more optimal than universal design principles. These included the use of larger-than-standard text, single-click navigation, and minimal scrolling for individuals using eye-gaze technology. The TLC Community Advisory Board insisted on having pop-up animated instructions to visually show users how to use functions, rather than text-based instructions.

Results

Our stakeholder informed methodology re-affirmed the importance of making family caregiver interventions as accessible and flexible as possible, while also providing evidence that older adults are likely capable and interested in using technology-delivered interventions. Nearly every stakeholder participant (>95%) rated themselves as ‘very confident’ in using email, completing online surveys, and downloading content. The majority (79%) preferred to complete weekly online or e-surveys, as opposed to mail or telephone surveys. And, 70% indicated it would be difficult to attend in-person support programs, due to various caregiving-related barriers such as not having time, not having back-up care for the care-recipient, lack of transportation, or living too far away. Similarly, stakeholders emphasized the need for flexibility, allowing family caregivers to access interventions on their own time, rather than only at prescheduled or prescribed meeting times. Such comments and insights made us realize that online delivery might actually be an ideal or preferred solution to address the needs of a caregiver population, rather than a consolation for not being able to provide one-on-one facilitated support.

Our use of community-engaged methods added time and expense to the intervention development (i.e., stakeholders are commonly paid as consultants); however, the input received from stakeholders helped create new resources - such as interactive online features, videos, informational webpages, and branded aesthetics - that would not have emerged had we followed a more traditional investigator-led development process. Some of the specific suggestions we received from stakeholders are summarized in Table 2, as we believe they may serve as important considerations for others who want to redevelop traditional interventions for online delivery. See also tips from Newell (2011) for universal design principles recommended for online interventions serving aging populations.

Table 2.

Insight Gained from Stakeholders: Universal Recommendations for the Development and Testing of Online Intervention Tools

| Features and Functionality of Online Tools |

Universal design principles are a good basis, but stakeholder input should ultimately inform design elements, especially when needing to accommodate special considerations of target population, such as functional limitations. Specific recommendations include:

|

| Language Used in Online Tools |

Simple, non-jargon language is preferable. Specific recommendations include:

|

| Research Design to Test Efficacy of Online Tools |

We were surprised that our stakeholders also provided us with ideas on how to design the research studies to evaluate the efficacy of each intervention. For example, our stakeholders suggested:

|

The online versions of TLC and SupportGroove were initially developed as interactive webpages accessible through common web browsers, rather than as an “app” compatible with Apple, Windows, or Android operating systems. This allowed us to focus on creating the essential interactive features of the interventions, so they could be tested for efficacy, without having to prematurely invest in the programming required for each operating system or to for the frequent updates required to maintain “apps” within each operating system. If initial efficacy is established within a web-based application, future activities can then focus on the creation of an “app” that has possible commercialization potential and can be distributed through the app stores associated with each operating system.

Discussion

This manuscript provides a case-study of the community-engaged methods that we used to redevelop two behavioral interventions – TLC and SupportGroove – for online delivery. The needs and context of the end-user need to be considered, in order to ensure that an intervention is optimally delivered through an online tool. By including stakeholders throughout the redevelopment process, we received advice about which features and functionality to include in the digital tools, as well as language and imagery that should be used to reach the widest, most diverse audience. These types of insight were invaluable, though not surprising. This is precisely the type of knowledge we had hoped to gain by committing to community-engaged methods. In addition, we received guidance from our stakeholders about how to design and conduct research to test the feasibility and efficacy of each intervention. This type of information was not expected, yet proved to be an invaluable benefit to using community-engaged methodologies during the redevelopment of the two interventions. The feedback we received from stakeholders during the redevelopment of our interventions will likely lead to interventions that are more widely accepted and can be implemented and disseminated in community settings.

The Value of Community-Engaged Methods for Intervention Research

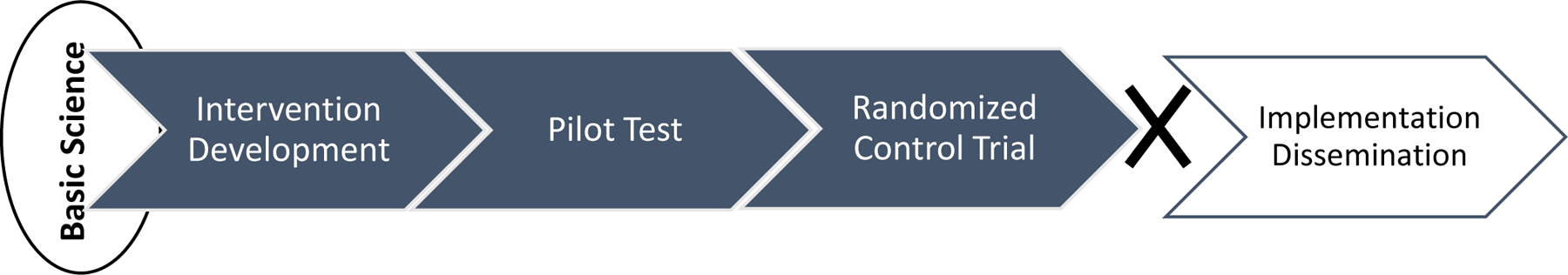

As show in Figure 1A, the traditional investigator-driven model of intervention research involves a linear set of steps that may not end in full implementation or dissemination of the intervention. Guided primarily by hypotheses and the empirical evidence derived from basic science, an investigator develops an intervention model, pilot tests it, and then conducts a randomized control trial to evaluate its efficacy, usually under a highly-controlled research setting where issues of treatment fidelity and standardization of intervention protocols are a priority. Results typically produce good science that is able to identify the causal mechanisms underlying an intervention’s effect, but may fall short before the intervention can be implemented or disseminated into practice and policy. Under this model, an intervention is designed and tested in a vacuum, relying mostly on the expertise and previous scholarship of the investigators.

Figure 1A. Investigator-Driven Intervention Research.

Figure 1B provides an alternate schema depicting a community-engaged approach to intervention research, such as what we used to redevelop TLC and SupportGroove into a self-administered, online-delivered intervention. This model emphasizes 1) a cyclical set of stages that identify, define, and clarify the features of an intervention through a series of five stages which may be followed sequentially or repeated through trial and error at each stage [see NIH Stage Model for more info, (Onken et al., 2014)], and 2) the direct and iterative process of allowing input and feedback from community stakeholders to inform each stage of the process. Like the investigator-driven model, this model is influenced by the results of basic science. Unlike the traditional model, it splits efficacy and effectiveness into three separate stages (2, 3, 4), where levels of research-imposed standardization are gradually relaxed to better reflect the nuances of real-world circumstances. The graded stages of efficacy and effectiveness allow for intervention modification, redevelopment, and refinement to occur between each stage. The arrows in the figure represent that, at each stage, community stakeholders provide feedback regarding their needs, preferences, values, and interests, hopefully culminating in the most potent and implementable intervention that can be given back to the community it is intended to serve. Community-engagement may be one way to decrease the digital divide seen in many communities, since it allows for the incorporation of diverse community perspectives, such as from those who are resistant to using online tools or who do not have access to reliable online technologies, to be considered during the initial design and creation stages.

Figure 1B. Community-Engaged Stage Model of Intervention Research.

This figure draws on the NIH Stage-Model for Behavioral Interventions (Onken et al., 2014).

TLC and SupportGroove were originally developed under the assumptions of Figure 1A. Through our initial pilot work, we came to the conclusion that we created interventions that were worthwhile and needed, yet reflected our interests and needs as a researcher more so than the needs and constraints of the family caregivers we were trying to support. As such, they would never have been implemented in real world settings as originally designed. They focused too heavily on the use of trained facilitators to achieve treatment fidelity.

As TLC and SupportGroove were redeveloped to be more fully self-administered and technology-delivered, our methodology began to reflect the processes depicted in Figure 1B. By doing so, we embraced the centrality and importance of community-engagement and benefited from the invaluable insight we gained when listening to our community stakeholders regarding the features of our interventions, as well as their feedback regarding the research methods that ought to be used to evaluate efficacy and effectiveness of these interventions. Adopting a community-engaged approach to the redevelopment of these two interventions allowed us to conceptually divorce ourselves from the traditional one-size-fits-all notion of intervention research, in favor of more pragmatic approaches that still have high levels of fidelity, yet are customizable, adaptable, and tailored to the general needs of the target population as well as the diverse characteristics of individual participants.

It takes time to do community-engaged research, especially to cultivate meaningful and authentic relationships with stakeholders and to iteratively adapt their feedback throughout the process. The redevelopment of traditional interventions into self-administered and technology-delivered models also takes time, as designers and software developers create, user-test, and refine digital tools before researchers can use them in formal studies to test their efficacy or effectiveness. Based on our experiences in redesigning the SupportGroove and TLC interventions for online delivery, we strongly recommend that intervention scholars adopt the Community-Engaged Stage Model approach as seen in Figure 1B. During the time that technical designers create and prototype new intervention resources, researchers can engage with community stakeholders.

Although standardized rubrics and scoring methods have been developed to measure how community-engaged a research project is (Goodman et al., 2017), there is no consensus on the right or wrong way to do community engagement or how community-engaged a project should be. Based on the enhanced results we experienced when using community-engaged methodology in the redevelopment of TLC and SupportGroove, we encourage other intervention scholars to embrace the utility and power of community engagement in their intervention research practices. To support those who want to use community-engagement, many universities are creating supports and resources through NIH-funded “Clinical and Translational Science Awards” (CTSA - https://ncats.nih.gov/ctsa). Additional “tool kit” resources, such as those from Scripps Translational Science Institute, may also provide more information for interested scholars who want to adopt community engaged intervention practices.

Acknowledgements

We thank the many community stakeholders who participated in the development of the SupportGroove and Time for Living and Caring interventions and research studies. Funding for these studies were provided by National Institute on Aging (R01AG061946 – Utz), the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research (R03HD091432 – Terrill), and the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation (PSR #440547 – Terrill).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest Statement

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest or other benefits associated with the publication of this research.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the authors by request.

References

- Ahmed SM, & Palermo A-GS (2010). Community Engagement in Research: Frameworks for Education and Peer Review. American Journal of Public Health, 100(8), 1380–1387. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altizer R, Zagal JP, Johnson E, Wong B, Anderson R, Botkin J, & Rothwell E (2017). Design Box Case Study: Facilitating Interdisciplinary Collaboration and Participatory Design in Game Developm. Paper presented at the Extended Abstracts Publication of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M (2019). Mobile technology and home broadband. In Pew Research Center: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum A (2015). Isolated, invisible, and in-need: There should be no “I” in caregiver. Palliative & supportive care, 13(3), 415–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Schaalma HC, Markham CC, … Mullen PDC (2006). Planning health promotion programs: an intervention mapping approach: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Bolier L, Haverman M, Westerhof GJ, Riper H, Smit F, & Bohlmeijer E (2013). Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1–20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cargo M, & Mercer SL (2008). The value and challenges of participatory research: strengthening its practice. Annual Review of Public Health, 29(1), 325–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.091307.083824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS). (2015). National Health Expenditures Fact Sheet.

- Chambers DA (2019). Sharpening our focus on designing for dissemination: Lessons from the SPRINT program and potential next steps for the field. Translational Behavioral Medicine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi N-C, & Demiris G (2015). A systematic review of telehealth tools and interventions to support family caregivers. Journal of Telemedicine & Telecare, 21(1), 37–44. doi: 10.1177/1357633X14562734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doris S, Cheng S-T, & Wang J (2018). Unravelling positive aspects of caregiving in dementia: An integrative review of research literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 79, 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman MS, Thompson VLS, Arroyo Johnson C, Gennarelli R, Drake BF, Bajwa P, … Bowen D (2017). Evaluating community engagement in research: quantitative measure development. Journal of community psychology, 45(1), 17–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvath TA, Mongoven JM, Bidwell JT, Cothran FA, Sexson KE, Mason DJ, & Buckwalter K (2020). Research Priorities in Family Caregiving: Process and Outcomes of a Conference on Family-Centered Care Across the Trajectory of Serious Illness. Gerontologist, 60, S5–S13. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joosten YA, Israel TL, Williams NA, Boone LR, Schlundt DG, Mouton CP, … Wilkins CH (2015). Community engagement studios: a structured approach to obtaining meaningful input from stakeholders to inform research. Academic Medicine, 90(12), 1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, & Schulz R (2008). Family caregivers’ strains: Comparative analysis of cancer caregiving with dementia, diabetes, and frail elderly caregiving. Journal of Aging and Health, 20(5), 483–503. doi: 10.1177/0898264308317533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer BJ (1997). Gain in the Caregiving Experience: Where are We? What Next? The Gerontological Society of America, 37(2), 218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeman DA, Kim KK, Gladstone C, & Apesoa-Varano EC (2020). Technology and Caregiving: Emerging Interventions and Directions for Research. Gerontologist, 60, S41–S49. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund DA, Utz RL, Caserta MS, Wright SD, Llanque SM, Lindfelt C, … Montoro-Rodriguez J (2014). Time for living and caring: An intervention to make respite more effective for caregivers. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 79(2), 157–178. doi: 10.2190/AG.79.2.d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lwi SJ, Ford BQ, Casey JJ, Miller BL, & Levenson RW (2017). Poor caregiver mental health predicts mortality of patients with neurodegenerative disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(28), 7319–7324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikesell L, Bromley E, & Khodyakov D (2013). Ethical community-engaged research: a literature review. American journal of public health, 103(12), e7–e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiver (NAC) & American Association for Retired Persons (AARP).(2020). Caregiving in the US, 2020. NAC & AARP: Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Science, E., Medicine. (2016). Families Caring for an Aging America. In. Washington, D.C.: National Academies. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Aging (NIA). National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease. https://aspe.hhs.gov/national-plans-address-alzheimers-disease

- Neena LC, & Reid RC (2002). Burden and Well-Being Among Caregivers: Examining the Distinction. The Gerontologist, 42(6), 772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell AF (2011). Design and the digital divide: insights from 40 years in computer support for older and disabled people. Synthesis Lectures on Assistive, Rehabilitative, and Health-Preserving Technologies, 1(1), 1–195. [Google Scholar]

- Newman SD, Andrews JO, Magwood GS, Jenkins C, Cox MJ, & Williamson DC (2011). Peer reviewed: community advisory boards in community-based participatory research: a synthesis of best processes. Preventing chronic disease, 8(3). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken LS, Carroll KM, Shoham V, Cuthbert BN, & Riddle M (2014). Reenvisioning Clinical Science: Unifying the Discipline to Improve the Public Health. Clin Psychol Sci, 2(1), 22–34. doi: 10.1177/2167702613497932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken LS, & Shoham V (2015). Technology and the stage model of behavioral intervention development.

- Marsch LA, Lord SE, & Dallery J (Eds.). (2015). Behavioral healthcare and technology: Using science-based innovations to transform practice. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parker SJ, Jessel S, Richardson JE, & Reid MC (2013). Older adults are mobile too! Identifying the barriers and facilitators to older adults’ use of mHealth for pain management. BMC geriatrics, 13(1), 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, & Sörensen S (2003). Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychology and aging, 18(2), 250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AW, Ogunwole SU, Blakeslee L, & Rabe MA (2018). The population 65 years and older in the United States: 2016: US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US: …. [Google Scholar]

- Roche V, & Palmer BF (2009). The hidden patient: addressing the caregiver. The American journal of the medical sciences, 337(3), 199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scripps Translational Science Center. Community Engaged Research Toolbox. https://www.scripps.edu/_files/pdfs/science-medicine/translational-institute/community-engagement/training-and-tools/Community_Engaged_Research_Toolbox.pdf

- Schulz R, O’Brien A, Bookwala J, & Fleissner K (1995). Psychiatric and Physical Morbidity Effects of dementia Caregiving: Prevelence, Correlates, and Causes. The Gerontologist, 35(6), 771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrill AL, MacKenzie JJ, Reblin M, Einerson J, Ferraro J, & Altizer R (2019). A Collaboration Between Game Developers and Rehabilitation Researchers to Develop a Web-Based App for Persons With Physical Disabilities: Case Study. JMIR Rehabilitation and Assistive Technologies, 6(2), e13511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrill AL, Reblin M, MacKenzie JJ, Cardell B, Einerson J, Berg CA, … Richards L (2018). Development of a novel positive psychology-based intervention for couples post-stroke. Rehabilitation Psychology, 63(1), 43–54. doi: 10.1037/rep0000181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, & Duran B (2010). Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health, 100 Suppl 1, S40–46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerts DJ, & Sandmann LR (2008). Building a two-way street: Challenges and opportunities for community engagement at research universities. The Review of Higher Education, 32(1), 73–106. [Google Scholar]

- Weissert WG, Cready CM, & Pawelak JE (2005). The past and future of home-and community-based long-term care. The Milbank Quarterly, 83(4). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch CJ, Feinberg LF, & Stevens EJ (1999). Predictors of institutionalization for persons with Alzheimer’s disease and the impact on family caregivers. Journal of Mental Health and Aging, 5(3), 275–288. [Google Scholar]

- Young HM, Bell JF, Whitney RL, Ridberg RA, Reed SC, & Vitaliano PP (2020). Social Determinants of Health: Underreported Heterogeneity in Systematic Reviews of Caregiver Interventions. Gerontologist, 60, S14–S28. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Bangerter LR, Liu Y, & Rovine MJ (2017). Exploring the benefits of respite services to family caregivers: methodological issues and current findings. Aging Ment Health, 21(3), 224–231. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1128881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the authors by request.