Abstract

Background

The time course and longitudinal impact of the COVID -19 pandemic on surgical education(SE) and learner well-being (LWB)is unknown.

Material and methods

Check-in surveys were distributed to Surgery Program Directors and Department Chairs, including general surgery and surgical specialties, in the summer and winter of 2020 and compared to a survey from spring 2020. Statistical associations for items with self-reported ACGME Stage and the survey period were assessed using categorical analysis.

Results

Stage 3 institutions were reported in spring (30%), summer (4%) [p < 0.0001] and increased in the winter (18%). Severe disruption (SD) was stage dependent (Stage 3; 45% (83/184) vs. Stages 1 and 2; 26% (206/801)[p < 0.0001]). This lessened in the winter (23%) vs. spring (32%) p = 0.02. LWB severe disruption was similar in spring 27%, summer 22%, winter 25% and was associated with Stage 3.

Conclusions

Steps taken during the pandemic reduced SD but did not improve LWB. Systemic efforts are needed to protect learners and combat isolation pervasive in a pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, ACGME emergency declaration, Surgical educational programs, Learner well-being, Learner wellness

The first case of COVID-19 in the United States occurred on January 21, 2020 and it was followed by widespread infections throughout the country eventually leading to over 500,000 deaths. Many publications have detailed how the pandemic disrupted our health care delivery system, surgical training, and the responses of hospitals. The majority of these reports represent single institution experiences or survey results obtained primarily during the first few months of the pandemic in the spring of 2020.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

In March of 2020, the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Division of Education appointed a Special Committee of the ACS Academy of Master Surgeon Educators (Special Committee) to address education related challenges associated with the pandemic. Recently, we reported the pandemic's impact on surgical learner education and well-being as assessed by Program Directors (PD), Chairs and ACS Academy members through a survey administrated to all surgical specialties April–June 2020.8

Anticipating that the impact of the pandemic would evolve over time, the original research plan envisioned two follow-up “Check-In” Surveys. The purpose of this study is to compare the findings of the initial survey with the Check-In Surveys. The specific aims were to identify:

-

•

The frequency of ACGME Emergency Declaration (Stage 3) and the overall and stage-specific impact on educational programs and trainee well-being.

-

•

The frequency and degree of educational program recovery following disruption.

-

•

Impact of the availability of high quality personal protective equipment (PPE) on surgical education and trainee well-being.

-

•

Lessons that may help education leaders prepare for and manage challenges during future pandemics or disasters of this magnitude.

Methods

The study was determined to be exempt by the American Institutes for Research Institutional Review Board, Washington, DC. Check-In Surveys were distributed to PDs and Chairs of general surgery and surgical specialties using email distribution lists obtained through the surgical specialty organizations. The summer Check-In Survey included seven items and the winter Check-In Survey included eight items, with the addition of an item relating to PPE. The Special Committee initially surveyed surgical educator leaders in the spring of 2020: April 24-May 29, 2020 (general surgery and related specialties) and May 4-June 26, 2020 (surgical specialties), n = 447.9 Check-In Surveys were then distributed in the summer of 2020 (July 14-September 3, 2020, n = 353) and the winter of 2020–21 (December 7, 2020–January 11, 2021, n = 224). 10

Both closed- and open-ended questions were used to gather quantitative and qualitative information regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical education and trainee wellness. The data were collected anonymously. The questions included descriptive information such as geographic region and self-reported ACGME Stage (1, 2, and 3)11 , 12 and direction in which the stage was moving (improving, stable or worsening). Assessment of impact on surgical trainee education, well-being and the recovery of educational programs was measured by responses to 5-point Likert-type questions and open-ended questions.

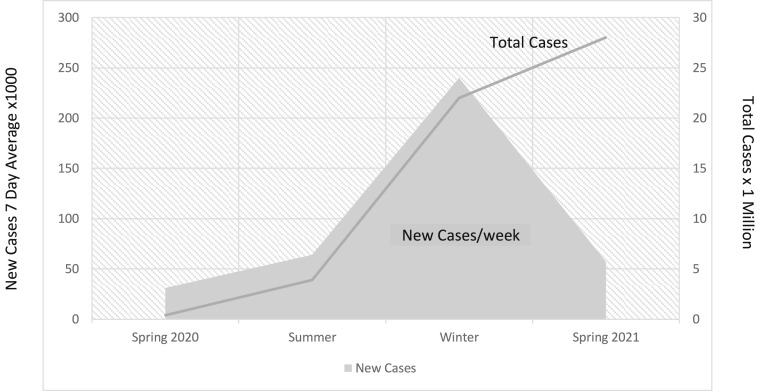

In order to assess the severity of the pandemic, information about the incidence of COVID-19 infection was obtained from the US COVID ATLAS presented as cumulative cases and cases per week at the close of each survey period.13 (Fig. 1 ). Information about the number of COVID-19 vaccines administered in the United States was obtained from a publicly available source.14

Fig. 1.

Cumulative cases and 7-Day average of new COVID-19 Infections13 The total number of COVID-19 cases and 7-day average, respectively, at the end of each survey period was reported by the US COVID Atlas as follows: spring – June 26, 2020–2,450,318 and 34,623; summer - July 14- September 3, 2020 6,070,879 and 40,337; Winter -December 7- January 11, 2021–22,249,686 and 242,989.13

The ACGME 2018–2019 Data Book15 and the Society of Surgical Chairs (SSC) membership list were used as references to determine the response rates (PD, n = 1836 and SSC, n = 187) In the spring of 2020, the total number of potential respondents was 2196 and included Academy members (n = 173). The total number of potential respondents for the Check-In Surveys was 2023 and did not include Academy members who were not PDs or Department Chairs.

Data collected via the online survey were exported for statistical analyses using SAS v9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC). For each period, data provided a cross-sectional analysis of ACGME Stage by respondent and by institution, and for a subset of key items and sub-items that assessed overall impact (6 sub-items). Responses were described using a five-level ordinal Likert-type scale, ranging from extreme impact (5) to no impact (1), except for the 4-item discrete ACGME Stage change and PPE status questions. Responses were dichotomized for analysis as severe impact (5 or 4 on the Likert-type scale) or moderate or lower impact (3,2,1 on the Likert-type scale). ACGME Stage, as previously described, was ultimately dichotomized as Stage 1 plus Stage 2 vs. Stage 3. Chi-Square analysis was used to assess the impact by Stage across all time periods. The location of the primary teaching institution was reported according to United States census regions and divisions; Northeast (NE) South (S), Midwest (MW) and Western (W).

To evaluate the association of the survey period, spring 2020 was used as a reference and analytic item odds ratios (OR) were generated using logistic regression to compare summer and winter 2020–21 with spring 2020. Further, we evaluated the analytic items OR with Stage 3 (ACGME Emergency Declaration) vs. Stage 1 and 2. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

In addition to quantitative questions, open-ended questions were used to gather information on institutional efforts to “innovate in surgical education” and to “support the wellness of learners” during the pandemic. Open-ended responses were coded and analyzed by two experienced qualitative researchers, and themes were identified.

Results

COVID-19 cases by survey period

The total number of COVID-19 cases and 7-day average, respectively, at the end of each survey period was reported by the US COVID Atlas as: i) spring – June 26, 2020–2,450,318 and 34,623; (ii) summer – July 14-September 3, 2020–6,070,879 and 40,337; (iii) winter – December 7-January 11, 2021–22,249,686 and 242,989.13 Fig. 1 shows the increasing cumulative case numbers by month and weekly average during the survey periods.

Status of COVID-19 vaccine administration

Wide distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine to health care workers had not taken place during the survey periods. The last check-in survey closed January 11, 2021 and as of January 12, 2021, no person in the United States had been fully vaccinated and 9,327,138 (2.84%) had received the first dose.14 Hence for the time periods of survey distribution, COVID-19 vaccination is not likely to be a confounding factor.

Response rate

The survey response rate decreased over time: spring 2020 21.4% (472/2196),8 summer 2020 17.3% (350/2023) and winter 2020–21 10.4% (212/2023).

Respondents’ educational role by survey period

PDs comprised 64% (253/394) of respondents in spring 2020.8 More PDs participated in the summer 2020 (76%; 267/350) [OR 1.8 (1.32–2.50) p = 0.003] and winter surveys (73%; 154/212) [OR 1.2 (1.01–1.44) p = 0.04]. Regional responses were equivalent in each period (NE 24–28%, S 30–34%, MW 25–27%, W12-15%).

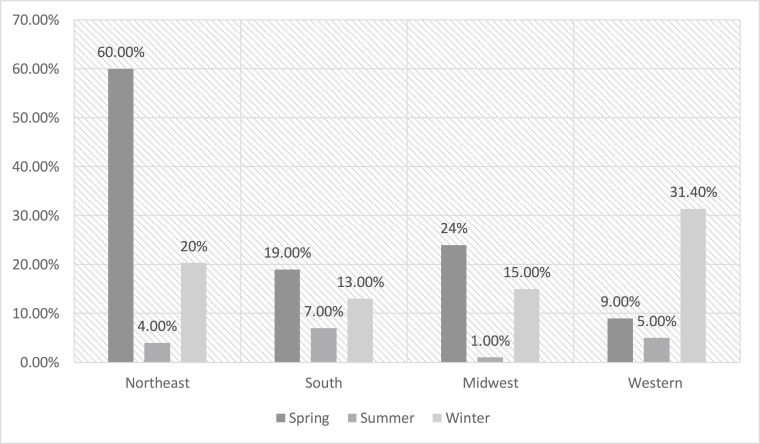

ACGME stage by survey period

ACGME Emergency Declaration (Stage 3) was highest in the spring (30%) and decreased in the summer (4%) [OR = 0.11(0.07–0.19) p < 0.0001] but increased again in the winter (18%), although remained less frequent than in the spring survey [OR = 0.73(0.60–0.88) p = 0.013). (Table 1 ). The regional percentage of ACGME Stage 3 institutions is shown in Fig. 2 .

Table 1.

Survey Periods are described for General Surgery and Surgical Specialty respondents according to ACGME Stage, region, and role in surgical education. Survey distribution dates occurred separately in the Spring (Period 1) for General Surgery (4/24–5/29/2020), Surgical Specialty (5/4–6/26 2020) and Clerkship Directors, however, were distributed simultaneously in the Period 2 - Summer (7/14–9/3/2020) and Period 3 - Winter (12/7/2020–1/11/2021). ACGME Stage designations 1–3 are described and extrapolated throughout, although ACGME Stage changed to a dichotomous designation in Periods 2 and 3.11

| Survey Parameter | Period 1 Spring | Period 2 Summer | Period 3 Winter | Period 1 vs Period 2 OR (95% CI)/p-value | Period 1 vs Period 3 OR (95% CI)/p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role | |||||

| Program Director | 64% (253/394) | 76% (267/350) | 73% (154/212) | 1.8 (1.32,2.50)/0.0003 | 1.2 (1.01,1.44)/0.04 |

| Chair | 36% (141/394) | 22% (76/350) | 17% (35/212) | ||

| Clerkship Director |

0% |

2% (7/350) |

11% (23/212) |

||

| ACGME Stage | |||||

| Stage 1 and 2 | 70% (331/472) | 96% (337/353) | 82% (183/224) |

Stage 3 vs Stage 1 and 2 0.11 (0.07, 0.19)/<.0001 |

Stage 3 vs Stage 1 and 2 0.73 (0.60, 0.88)/0.013 |

| Stage 3 |

30% (141/472) |

4%% (16/353) |

18% (41/224) |

||

| Stage 3 by Region | |||||

| Northeast | 60% (73/121) | 4% (4/97) | 20% (12/59) |

Stage 3 vs Stage 1 and 2 0.028 (0.01, 0.08)/<.0001 |

Stage 3 vs Stage 1 and 2 0.41 (0.28, 0.59)/<.0001 |

| South | 19%% (26/140) | 7% (9/121) | 13% (9/70) | 0.35 (0.16, 0.79)/0.011 | 0.80 (0.53, 1.21)/0.30 |

| Midwest | 24% (29/121) | 1% (1/92) | 15% (9/60) | 0.04 (0.01, 0.26)/0.011 | 0.75 (0.50, 1.13)/0.17 |

| Western | 9% (6/65) | 4% (2/42) | 31% (11/34) | 0.49 (0.09, 2.56)/0.40 | 2.12 (1.22, 3.68)/0.007 |

Fig. 2.

ACGME Stage 3 (Emergency Declaration) by region comparing surveys in the spring, summer, and winter of 2020.

In the summer 2020 survey, 15% (51/350) reported ACGME Stage worsening compared to 44% (97/221) in the winter [OR = 4.59(3.08–6.83) p < 0.0001]. The increase of the reported ACGME Stage level from summer to winter occurred across all regions: NE 51% [11.5 (4.73–28.07) p < 0.0001]; S 38% [2.55 (1.31–4.96) p = 0.006]; MW 37% [6.05 (2.45–14.71)p < 0.0001]; W 58% [3.33 (0.29–8.59) p = 0.013]. (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Directional change in ACGME Stage of the primary institution comparing Winter (Period 3) to Summer (Period 2). Respondents indicated that educational program parameters worsened during the exponential wave of COVID-19 which occurred in Period 3 – Winter (12/7/2020–1/11/2021) compared to the flattening of the incidence of COVID-19 infections in Period 2 – Summer (7/14–9/3/2020) that varied by region, likely reflecting the frequency of infection.

| Education Program Parameters | Period 2 Summer | Period 3 Winter | Period 3 vs. Period 2 OR (95% CI)/p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Respondents | |||

| Worsening | 15% (51/350) | 44% (97/221) | 4.59 (3.08, 6.83)/< .0001 |

| Improving/Stable/Unsure |

85% (299/350) |

56% (124/221) |

|

| Worsening by Stage | |||

| Stage 1 and 2 | 15% (50/334) | 42% (76/180) | 4.15 (2.72, 6.32)/<.0001 |

| Stage 3 |

6% (1/16) |

51% (21/41) |

15.7 (1.90, 130.4)/0.011 |

| Worsening by Region | |||

| Northeast | 8% (8/97) | 51% (29/57) | 11.5 (4.73, 28.07)/<.0001 |

| South | 19% (23/112) | 38% (26/69) | 2.55 (1.31, 4.96)/0.006 |

| Midwest | 9% (8/91) | 37% (22/60) | 6.05 (2.45, 14.71)/<.0001 |

| Western | 29% (12/42) | 57% (20/35) | 3.33 (0.29, 8.59)/0.013 |

Impact on educational programs by survey period

Across all three periods, severe disruption of educational programs was reported by 29% (289/985) of respondents. There was no difference between spring 2020 (32%) and summer 2020 (31%) [OR = 0.96 (0.70–1.30) p = 0.78]. However, there was a significant decrease in severity of impact on education programs when comparing the surveys in the spring (32%) and winter (23%) [OR = 0.80 (0.67–0.97) p = 0.02]. Across all periods, the severity of disruption was more in Stage 3: 45% (75/184) vs. Stage 1 and 2: 26% (206/801) [p < 0.0001]. (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Frequency of reported severe impact on educational programs and substantial recovery (4 or 5 on Likert-Type question) of educational programs. Across all time-periods, ACGME Stage was associated with reported severe impact on education programs (Stage 1–2; 26% and Stage 3; 45%, Chi-square analysis p < 0.0001). The frequency of reported severe impact lessened comparing Period 3 to Period 1 (p = 0.02). Substantial recovery of educational programs tended to occur more commonly in ACGME Stage 1–2 programs (45%) than those reporting Stage 3 (37%) and was modest occurring in equivalent proportions across all regions without improvement over time, where Period 1 – Spring (4/24–5/29 and 5/4–6/26 2020); Period 2 – Summer (7/14–9/3/2020); and Period 3 – Winter (12/7/2020–1/11/2021).

The current ACGME system for assessing educational impact is dichotomous - Emergency Declaration or not, and is equivalent to Stage 3 in the older version).1

| Survey Parameter | Period 1 Spring | Period 2 Summer | Period 3 Winter | All Periods | Period 2 vs Period 1 OR (95% CI)/p-value | Period 3 vs Period 1 OR (95% CI)/p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe Impact on Education Program | ||||||

| Across all ACGME Stages | 32% (130/411) | 31% (108/352) | 23.0% (51/222) | 29.3% (289/985) | 0.96 (0.70, 1.30)/0.78 | 0.80 (0.67, 0.97)/0.02 |

| Stages 1 and 2 | 25% (71/283) | 29% (98/336) | 20% (37/182) | 26% (206/801) | 1.23 (0.86, 1.76)/0.26 | 0.87 (0.70, 1.09)/0.23 |

| Stage 3 | 46% 59/128 |

62% (10/16) | 35% (14/40) | 45% (83/184) | 1.95 (0.67, 5.68)/0.22 | 0.79 (0.55, 1.15)/0.21 |

| Substantial Recovery of Educational Programs by Stage |

Period 3 vs Period 2 OR (95% CI)/p-value |

|||||

| Across all Stages | 44% (155/350) | 43% (97/223) | 44% (252/573) | 0.97 (0.69, 1.36)/0.85 | ||

| Total Stages 1 and 2 45% (231/516) |

44% (148/334) | 46% (83/182) | 1.05 (0.73, 1.52)/0.78 | |||

| Total Stage 3 37% (21/57) |

43% (7/16) | 34% (14/41) | 0.67 (0.21, 2.17)/0.50 | |||

| Substantial Recovery of Educational Programs by Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 52.% (51/98) | 46% (27/59) | 0.78 (0.41, 1.49)/0.45 | |||

| South | 39% (46/119) | 47% (33/70) | 1.42 (0.78, 2.57)/0.25 | |||

| Midwest | 42% (38/91) | 36% (21/59) | 0.77 (0.39, 1.52)/0.45 | |||

| Western | 48% (20/42) | 46% (16/35) | 0.93 (0.38, 2.28)/0.87 | |||

Although 44% (252/573) of previously impacted education programs reported substantial recovery between the first survey and the Check-In Surveys, the plurality of participants (56%) indicated that their educational programs did not fully recover. Substantial recovery tended to be more frequent in Stage 1 and 2 (45%; 231/516) compared to Stage 3 (37%; 21/57), did not differ between the summer (44%; 148/334) and winter (46%; 83/182) [OR 1.05 (0.69–1.36 p = 0.85) and was consistent across all regions (Table 3).

Findings of the qualitative analysis included a common shift to virtual education platforms which was noted to be both convenient and accessible, however this change was associated with a lack of interaction and engagement by learners who were frequently dissatisfied. Many participants expressed concern about fewer surgical case numbers, the effect of “pausing” teaching in the operating room and what the impact may be on the development of competence and readiness for graduation. This was more often cited in the summer than the winter survey. Finally, there was concern about deployment to non-surgical areas which was reported more frequently in the spring (Appendix 1 e-component).

Impact on trainee well-being by survey period

Severe impact on trainee well-being was similar across all three surveys: spring 2020 (27%; 110/406) vs. summer 2020 (22%; 78/351) [OR 0.77 (0.55–1.07) p = 0.12]; spring 2020 vs. winter 2020–21 (25%; 55/223) [OR 0.93 (0.78–1.13) p = 0.51]. There was no improvement in the reported frequency of severe impact on learner well-being comparing Period 2 to Period 1 or Period 3 to Period 1.Across all survey periods, the severity of impact was associated with increasing stage: Stage 1–2 [21% (168/769)] vs. Stage 3 [41% (75/184)] [p < 0.0001]. (Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Frequency of severe impact on learner well-being by ACGME Stage. Across all time-periods, severe impact on learner well-being was greater in Stage 3 respondents (41%) compared to Stages 1 and 2 (21%) [Chi-square analysis, p < 0.0001]. In each time-period ACGME Stage was associated with reported more severe disruption on learner well-being. Comparing Period 2 to Period 1, and Period 3 to Period 1, there was no improvement in the reported frequency of severe impact on learner well-being, where Period 1 – Spring (4/24–5/29 and 5/4–6/26 2020); Period 2 – Summer (7/14–9/3/2020); Period 3 – Winter (12/7/2020–1/11/2021).

The current ACGME system for assessing educational impact is dichotomous - Emergency Declaration or not, and is equivalent to Stage 3 in the older version).11

| Survey Parameter: Severe Impact on Learner Well-Being | Period 1 Spring | Period 2 Summer | Period 3 Winter | All Periods | Period 2 vs Period 1 OR (95% CI)/p-value | Period 3 vs Period 1 OR (95% CI)/p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All ACGME Stages | 27.% (110/406) | 22.% (78/351) | 24.% (55/223) | 0.77 (0.55, 1.07)/0.12 | 0.93 (0.78, 1.13)/0.51 | |

| Stages 1 and 2 | 20.% (57/279) | 22.% (74/335) | 20.% (37/182) | 21%a (168/796) | 1.10 (0.75, 1.63)/0.62 | 1.00 (0.79, 1.26)/0.98 |

| Stage 3 | 42% (53/127) | 25% (4/16) | 44% (18/41) | 41%a (75/184) | 0.47 (0.14, 1.52)/0.21 | 1.05 (0.73, 1.49)/0.81 |

Specific themes identified in the qualitative assessment included isolation (noted by a large number of participants), anxiety, general fear of COVID, missing family and fear for their safety, resentment for a poorly perceived institutional response, and concerns about PPE. Many described PPE fatigue which include trying to find PPE, the time burden of donning and doffing, and difficult to decipher, continually changing PPE rules. Themes that arose for institutional responses to support wellness are shown in Table 5 . For specific comments see Appendix 1 e-component.

Table 5.

Institutional responses to enhance trainee well-being.

| Institution Response |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Availability of PPE and impact on educational programs and trainee well-being

In the winter survey, PPE was reported as readily available and of high quality by 82% of respondents and did not vary by region: NE 79.7% (47/59); S 80% (56/70); MW 83.3% (50/60); W 88.6% (31/35) p = 0.69. Overall, only 18% (40/224) of programs reported PPE as not high quality and not readily available. However, if this was the case, severe impact on educational programs tended to be more frequently reported compared to those with access to high quality, readily available PPE (30% vs. 21% [OR 0.64 (0.30–1.37) p = 0.25]. Similarly, the impact on learner well-being tended to be reported more often as severe (33% vs. 23% [OR 0.59 (0.28–1.25) p = 0.17]. These trends did not reach statistical significance (Table 6 ).

Table 6.

PPE availability in Period 3 by ACGME Stage and Region. Most respondents indicated that High Quality (HQ)/PPE was readily available. Availability was tended to be reduced in ACGME Stage 3 and did not vary by Region. Readily available PPE did not prevent disruption of educational programs or learner well-being, which was reported respectively in this group as 21% and 23%. Lack of HQ PPE availability was very uncommon but was associated with a slight trend toward a more frequent severe impact on educational programs (30% vs 20%, p = 0.25) and was associated with a greater frequency of disruption of learner well-being (33% vs 23%, p = 0.17), although respondent sample size was small.

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) availability and of high quality (HQ) in the Winter (Period 3) by Survey Parameter (Stage, Region, Severe Impact) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Survey Parameter | Yes | No | OR (95% CI)/p-value |

| ACGME Stage | |||

| All Stages (1–3) | 82% (184/224) | 18% (40/224) | |

| Stage 1/2 | 84% (154/183) | 16% (29/183) | Odds ratio of having available/HQ PPE if “Stage 3” |

| Stage 3 |

73% (30/41) |

27% (11/41) |

0.51 (0.23, 1.14)/0.10 |

| Region | |||

| All Regions | 82% (184/224) | 18% (40/224) | p = 0.69 |

| Northeast | 80% (47/59) | 20% (12/59) | 1.25 (0.41, 2.32)/0.43 |

| a South | 80% (56/70) | 20% (14.70) | a South used as reference |

| Midwest | 83% (50/60) | 17% (10/60) | 1.25 (0.51, 3.06)/0.98 |

| Western |

89% (31/35) |

11% (4/35) |

1.94 (0.59, 6.40)/0.29 |

| Severe Impact on | Odds ratio of having available/HQ PPE if “Severe Impact” | ||

| Education | 21% (39/182) | 30% (12/40) | 0.64 (0.30, 1.37)/0.25 |

| Learner Well-Being | 23% (42/184) | 33% (13/39) | 0.59 (0.28, 1.25)/0.17 |

Discussion

The specific aims of this study were to longitudinally assess the opinions of educators on surgical education and trainee wellness as they related to ACGME Emergency Declaration, patterns of recovery of these parameters, the impact of PPE availability and lessons that may be applicable to similar disasters.

ACGME stage

In the spring of 2020, 30% of programs responding to the surveys ACGME Stage 3, consistent with the regional distribution reported by the ACGME.8 , 12 (Fig. 2) Surprisingly, three quarters of Stage 1 (business as usual) programs reported severe impact on clinical volumes with more than a 70% decrease in non-emergency surgery.8 It appears that lower Stage institutions in areas without COVID-19 outbreaks had a substantial reduction in operative volume due to national and state regulations designed to reduce the incidence of infection and to preserve PPE and hospital beds. The unintended consequence of these actions was that surgical training was negatively impacted across a number of programs.

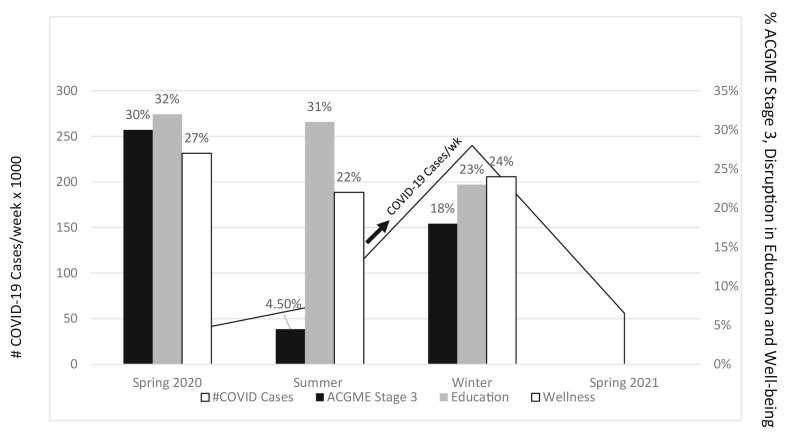

In the summer, the proportion of ACGME Stage 3 institutions decreased to 4% from nearly one third in the spring. (Fig. 3 ). This is consistent with a general flattening of the infection curve over the summer months but also reflects improved diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19. In the winter, the number of Stage 3 institutions increased to 18% (Fig. 3). This is consistent with a “second-wave” increase in infection rate (Fig. 1). However, the number of Stage 3 programs was significantly lower than in the spring despite an exponential increase in cases. It is likely that better institutional preparation in the later phases of the pandemic including improved understanding of diagnosis and outpatient treatment of COVID-19 patients reduced the number of hospitalized patients and, in turn, reduced the impact on non-emergency surgery. As a result, hospitals reported a gradual return of elective case volumes. According to the participants’ comments, surgical volumes had largely normalized by the winter 2020–21, if not earlier.

Fig. 3.

Relationship of the number of COVID-19 cases per week,13 the % ACGME Stage 3 (Emergency Declaration), % Severe Disruption of Education Programs and Trainee Wellness over three survey periods in 2020 (spring, summer, winter). Compared to the spring, there was a significant decrease in the proportion of Stage 3 institutions as the pandemic continued across the summer and winter months. The frequency of severe disruption on education programs lessened in the winter despite an exponential increase in COVID-19 cases. The reported frequency of severe impact on trainee well-being did not improve over the three survey periods.

Education program impact

In the spring, nearly one-third of all participants reported severe challenges in surgical educational programs, with some activities suspended. Nearly all had switched to a virtual format.8 The disruption of education was more frequent with advancing ACGME Stage. However, disruption in education did occur (but to a lesser extent) in training programs sponsored by hospitals at a lower ACGME Stage, likely reflecting the impact of national and state regulations.

With the marked decrease in the proportion of Stage 3 institutions reported in the summer and only 15% of respondents reported worsening of ACGME status, one would have expected that the severity of impact on educational programs would have been less in the summer than spring. However, this was not the case. Severe disruption on education was nearly identical in both periods (Fig. 3). This finding eludes a simple interpretation but likely reflects the continued impact of social distancing and a degree of dissatisfaction with the changes in education format and platforms.

Surgical education is also inextricably linked to the volume of surgery. The American Board of Surgery and related specialty boards recognized this early on in the pandemic and decided to accept a 10% decrease in time requirements and case requirements for board applicants. 16 Although clinical volume was not specifically addressed in the Check-In Surveys, there are many reports that document a concern for decreased volumes across all surgical specialties.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 Further, comments from the participants in the summer 2020 Check-In Survey reflect the disruption of surgical caseloads that carried over from the spring (”10 weeks without elective GYN Surgery”; “many are concerned about their ability to get all necessary OR cases”; “uncertainty and frustration with decreased surgical volume”). This is also supported by the findings of a survey of residents conducted in July 2020.7 The results showed that the majority of respondents (84%) reported a reduction of at least 50% in non-emergency case volume and 19% reported a decrease in emergency case volume.

It is possible that the decreases in surgical volume seen in the spring of 2020 and the slow return of non-emergency surgery in the summer are responsible for the lack of improvement in the surgical education programs despite the marked reduction of Stage 3 hospitals. Recovery of surgical educational programs seems to lag behind resolution of an institutional emergency declaration.

In the winter, the proportion of respondents who indicated a severe impact on educational programs was significantly less than in the spring and is consistent with fewer ACGME Stage 3 institutions at that time. (Fig. 3). Adaptations in educational programs earlier in the pandemic maintained delivery of curricular content. This combined with institutional adoption of advances in COVID-19 diagnosis and treatment allowing for the return of non-emergency surgery likely lessened the disruption of clinical education in lower ACGME Stage hospitals. Programs still in ACGME Stage 3 had fewer surgical cases and the Check-In Survey comments reflected these lower volumes. The following is a representative quote from the winter survey: “some patients are choosing to not have surgery so overall we are doing ∼85% of our normal volume and more cases cancelled when preop screening for COVID-19 comes back positive and cases are then rescheduled for 6–8 weeks later”.

Substantial recovery of educational programs was reported by less than one-half of the participants (Table 3). Incomplete recovery of educational programs was more common in ACGME Stage 3 institutions (Table 3) likely explained by logistical delays in re-establishing essential elective surgical services caused by the interaction of multiple factors including lack of widespread COVID-19 testing and readily available and high quality PPE, a backlog of surgical cases, and patients deciding to postpone surgery. Education leaders could deliver the educational curriculum through virtual formats and provide content, however, could not control the volume of surgical cases essential for the training of surgical residents.

The most effective strategy to prevent educational disruption in this pandemic was for institutions to proactively take the necessary steps to ameliorate conditions that necessitate an emergency declaration rather than trying to resuscitate a severely disrupted program. These steps included provision of the educational curriculum through virtual platforms and ensuring the volume of essential surgery needed for training by following national guidelines on the resumption of elective surgery.24

Impact on trainee well-being

Although we did not survey learners, severe impact on learner wellness was reported by nearly a quarter of the respondents in all survey periods and was ACGME Stage dependent. Despite wide adoption of coping assistance and increased sensitivity toward learners, trainee well-being was threatened throughout the pandemic. This is reflected in a survey of residents that showed the pandemic had a negative impact on physical health (47%), physical safety (53%) and mental health (70%).7 It was noted that the main negative factors associated with trainee wellness were lack of institutional sensitivity to the needs of trainees, inadequate COVID-19 testing, and poor access to PPE.7

Over 80% of the participants in the Check-In Survey indicated that high quality PPE was readily available. However, when it was not, there tended to be greater disruption on trainee well-being and educational programs. A common theme of many published surveys on the impact of COVID-19 on learner health is the deleterious effect of shortages of PPE. However, providing PPE alone is insufficient to prevent disruption of trainee well-being during a pandemic. Respondent comments illustrate the pervasive effect of isolation and loneliness on well-being across all periods. This is a theme that emerged from the qualitative data with comments like, “… nothing is being done”. Frustration was evident in many of the participants comments such as “Resources are offered but not sure how deep such support truly goes”. Further research related to trainee well-being will be necessary for us to design and implement more effective wellness programs for surgical trainees. Ideally, these investigations should include additional feedback from surgical trainees’ regarding their well-being to determine what wellness initiatives are most effective and to collect their perspectives and opinions that may differ from the surgical education leaders.

Factors associated with the impact of COVID-19 pandemic

Considering the contextual framework of the pandemic over three time periods provides insight into the complex interrelationship of novel viral outbreaks and the necessary public health response of the federal government and states to control and manage its spread. During this pandemic, the disruption on health care,related educational programs and learner well-being was driven by several interrelated factors including the number of new COVID-19 cases, nationwide guidelines to postpone elective non-essential and non-urgent care including surgical procedures, state shelter-at-home lockdown measures, availability of COVID-19 testing, availability of PPE, and improved methods of prevention (social distancing and masks) and treatment of COVID-19 and ultimately development of effective vaccines. Table 7 shows the relationship between the severity of impact on surgical education and learner well-being and the incidence of COVID-19 infection and other factors that impacted delivery of surgical care. The greatest disruption was observed in spring 2020 when there were relatively few cases nationally and a disproportionately high incidence in the NE. However, disruption was observed across the country in many areas with few cases. We observed that educational programs improved as the pandemic became more severe, but the recovery of programs is slower than one might expect. This is likely due to several factors including a back log of cases and the necessary requirement of COVID-19 testing in order to access non-emergency surgical care. Of concern was the sustained disruption of trainee well-being. Based on these observations, in future pandemics education leaders will not only need respond to a new disease threat but will need to make adjustments required by public health regulations that can disrupt services and education.

Table 7.

Summary of factors associated with the severe disruption of surgical education and trainee well-being during the three phases of the COVID-19 pandemic assessed in this study. (a) Florida, Texas, Arizona, Mississippi, and New Mexico.

| Parameter | Spring 2020 (March–June 26, 2020) | Summer 2020 (June 27-September 3, 2020) | Winter 2020 (September 4, 2020–January 11, 2021) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe Impact on Educational Programs across all ACGME Stages | 32% (130/411) | 31% (108/352) | 23.0% (51/222) |

| Severe Impact on Trainee Well-Being across all ACGME Stages | 27.% (110/406) | 22.% (78/351) | 24.% (55/223) |

| Total COVID-19 Cases | 2,450,318 | 6,070,879 | 22,249,686 |

| 7-day Average COVID-19 Cases |

34,623 | 40,337 | 242,989 |

| CMS Guidelines to Postpone-Cancel Non-emergency Surgery | March 18, 2020 | No New Guidelines | No New Guidelines |

| CMS Guidelines to Reopen Access to Non-emergency Surgery | April 19, 2020 Limited to States with few or declining cases June 8, 2020 Facilities to check with State and Local Officials |

No New Guidelines | Joint Statement on Maintaining Essential Surgery25 |

| State Actions on Non-emergency Surgery | Mid-April 2020 36 States suspend non urgent procedures 14 States cancellation up to providers |

Some States loosened restriction on non-emergency surgery Five states reimposed restrictions on Non-emergency surgery (a) |

Provider based postponements or cancelations continued on a regional basis depending on COVID -19 Incidence |

| Shelter-at-Home Orders | 42 States and District of Columbia mandatory orders Eight jurisdictions had mandatory orders extend beyond May 3126 |

All State Shelter-at Home orders expired or were superseded or rescinded by July 17, 202027 | No new orders |

| Reduction in Non-Emergency Surgery28 | 70% Reduction8 | 10–20% Reduction | 0–20% Reduction With Regional postponement or cancelation24 |

| % Population Fully Vaccinated | Zero | Zero | Zero |

Limitations

The findings reported here in must be interpreted with caution. First, the surveys could be subject to response bias with those having a more negative experience during the COVID-19 pandemic being more likely to complete the survey. Second, over the three time periods the number of respondents decreased which may indicate survey fatigue. In a number of the analyses the respondent numbers were small. Finally, we did not survey the surgical trainees as this has been a focus of other studies.7 , 29 Thus, the observations are from the point of view of surgical education leaders which may be different than the perceptions and opinions of trainees. However, we believe the findings are pertinent and outweigh the limitations based upon the uniqueness of the study in covering three phases of the pandemic. Future studies should include additional feedback from learners to better understand the impact of the pandemic on their education and personal wellness. This is important to address any individual or institutional challenges that persist and to help in the preparation prepare for future disasters and crises.

Conclusions

The disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical education did not occur at a single point in time but rather over many months and was associated with several interrelated factors (Table 7). As the pandemic evolved, so too did institutional responses. Important findings and lessons emerged.

-

1.

ACGME Emergency Declaration (Stage 3) is correlated with disruption of education programs and trainee well-being.

-

2.

During the course of the pandemic, the number of ACGME Emergency Declarations decreased. This in turn reduced the impact on surgical education programs. Once disrupted, educational programs had variable recovery.

-

3.

Taking proactive steps to avoid an ACGME emergency declaration reduces the degree of educational disruption, and as such ongoing prospective assessment of institutional status is essential. In Stage 1 or Stage 2 situations, early application of education innovations (e.g., virtual conferences) and access to COVID-19 screening and treatments may be helpful in reinstating non-emergency surgery, which may prevent the need for an emergency declaration.

-

4.

Reduction of ACGME Stage in and of itself did not improve trainee well-being. More research is needed on the causes of and threats to learner well-being in a pandemic situation. At a minimum, institutional attention to safety precautions such as availability of PPE and support for residents should be considered essential. Future prioritization of trainees for vaccinations as well as dedicated time for wellness programs to combat isolation should be afforded.

Funding

No extramural funding was used to support this project.

Declaration of competing interest

None of the authors of the paper entitled “Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Surgical Trainee Education and Wellness Spring 2020-Winter 2020: A Path Forward” has a conflict of interest relevant to the manuscript. Dr. Ellison receives royalties for unrelated original contributions from McGraw Hill Medical and Wolters- Kluwer.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the following Academy Survey Subcommittee Members for their consultation and discussion: Haile T. Debas MD, FACS, FRCS(C) and Timothy J. Eberlein MD, PhD, FACS. In addition, we wish to acknowledge Susan Newman, MPH and Linda K. Lupi,MBA without whom we could not have completed the project. We also wish to thank the following organizations which gave us permission to circulate the survey to their members, and their membership who completed the survey: Academic Orthopaedic Consortium, American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, American Council of Academic Plastic Surgeons, Association of Program Directors in Colon & Rectal Surgery, Association of Program Directors in Surgery, Association of Program Directors in Vascular Surgery, Association of Pediatric Surgery Training Program Directors, Association of University Professors in Ophthalmology, The Council of University Chairs of Obstetrics and Gynecology & Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Otolaryngology Program Directors Association, Society of Academic Urologists, Society of Neurological Surgeons, Society of Surgical Chairs, Surgical Oncology Fellowship Committee for SSO, and Thoracic Surgery Directors Association.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2021.05.018.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Manson D.K., Shen S., Lavelle M.P., et al. Reorganizing a medicine residency program in response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in New York. Acad Med. Nov. 2020;95(11):1670–1673. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000003548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coons B.E., Tam S.F., Okochi S. Rapid development of resident-led procedural response teams to support patient care during the coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic: a surgical workforce activation team. JAMA Surg. Apr 30 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nassar A.H., Zern N.K., McIntyre L.K., et al. Emergency restructuring of a general surgery residency program during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: the University of Washington experience. JAMA Surg. Jul 1 2020;155(7):624–627. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nobel T.B., Marin M., Divino C.M. Lessons in flexibility from a general surgery program at the epicenter of the pandemic in New York City. Surgery. Jul 2020;168(1):11–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2020.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He K., Stolarski A., Whang E., Kristo G. Addressing general surgery residents' concerns in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020 Jul - Aug 2020;77(4):735–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adesoye T., Davis C.H., Del Calvo H., et al. Optimization of surgical resident safety and education during the COVID-19 Pandemic - lessons learned. J Surg Educ. Jul 1 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman J.R., Abdelsattar J.M., Glocker R.J. COVID-19 Pandemic and the lived experience of surgical residents, fellows, and early-career surgeons in the American College of Surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. Oct 16 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellison E.C., Spanknebel K., Stain S.C., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical training and learner well-being: report of a survey of general surgery and other surgical specialty educators. J Am Coll Surg. Dec 2020;231(6):613–626. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.08.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Survey 1( Spring 2020) Survey Link https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/ACSAcademyCovid19Education accessed March 6, 2021.

- 10.Period 2 (Summer 2020 ) and Survey 3(winter 2020-21) Survey Link https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/ACSAcademyCOVID19CheckIn accessed March 12, 2021..

- 11.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. “(Archived) three stages of GME during the COVID-19 pandemic “ACGME response to coronavirus (COVID-19).” Available at: https://acgme.org/COVID-19/-Archived-Three-Stages-of-GME-During-the-COVID-19-Pandemic Accessed August 2, 2020..

- 12.Nasca T.J. ACGME's Early Adaptation to the COVID-19 Pandemic: principles and L lessons learned. J Grad Ed. 2020:375–378. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-20-00302.1. https://www.jgme.org/doi/pdf/10.4300/JGME-D-20-00302.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US COVID ATLAS . The Center for Spatial data Science @UChicago funded in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation https://theuscovidatlas.org/map accessed March 4, 2021.

- 14.Our World in data/covid-19-data/Google https://www.google.com/search?q=number+of+covid-19+vaccines+administered+in+us&rlz=1C1JZAP_enUS851US851&oq=number+of+COVID-19+Vaccines+&aqs=chrome.3.69i57j0l5j0i390l2.14951j0j15&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 accessed February 28, 2021..

- 15.ACGME Data Resource Book https://www.acgme.org/About-Us/Publications-and-Resources/Graduate-Medical-Education-Data-Resource-Book Table A.4 page 17-19. Accessed March 6, 2021.

- 16.The American Board of Surgery . Modifications to Training March 26, 2020 www.absurgery.org/default.jsp?news_covid19_trainingreq accessed May 15, 2015..

- 17.Stuart B. Health Affairs; October 8, 2020. How the COVID-19 Pandemic Has Affected the Provision of Elective Services: The Challenges Ahead.https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20201006.263687/full/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daly R. Health Care Finance Management Organization; July 30,2020. Elective Surgery Volume Near Normal in Late July , Analysis Finds.https://www.hfma.org/topics/news/2020/07/elective-surgery-volume-near-normal-in-late-july--analysis-finds.html [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons . COVID-19 Surgical Volume Impact Survey. https://www.aaos.org/globalassets/about/covid-19/research/covid-19-surgical-volume-impact-survey.pdf accessed March 12, 2021.

- 20.Lee, Y, Kirubarajan, A, Patro N, etalImpact of hospital lockdown secondary to COVID-19 and past pandemics on surgical practice: a living rapid systematic review. Am J Surg. 2020;222:67-85. doi 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Hervochon R., Atallah S., Levivien S. Impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on ENT surgical volume, European Annals of Otorhinolaryngology. Head and Neck Diseases. 2020;137:269–271. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2020.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maxwell Y. February 2, 2021. As Cardiac Surgery Volumes Fell in Early COVID-19 , Deaths Climbed.https://www.tctmd.com/news/cardiac-surgery-volumes-fell-early-covid-19-deaths-climbed [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eyewire News . 2020. AORN Releases Survey Results Exploring OR's Return to Pre-COVID-19 Surgical Volumes.https://eyewire.news/articles/aorn-releases-survey-results-exploring-ors-return-to-pre-covid-19-surgical-volumes/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Becker's Hospital Review https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/patient-flow/110-hospitals-postponing-elective-surgeries-by-state.html accessed March 4, 2021..

- 25.Joint Statement : Roadmap for Maintaining Essential Surgery during COVID-19 Pandemic ( Nov. 23, 2020 American College of Surgeons, American Society of Anesthesiologists , Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses, American Hospital Association. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/nov2020-roadmap accessed March 11, 2021.

- 26.Moreland A., Herlihy C., Tynan M.A., et al. 2020. CDC Morbidity and Mortality Report . Timing of State and Territorial Stay at Home Orders and Changes in Population Movement – United States.https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6935a2.htm March 1-May 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.State “Shelter-in-place” and “ Stay at home orders” https://www.finra.org/rules-guidance/key-topics/covid-19/shelter-in-place accessed May 15, 2021.

- 28.Meredith J.W., High K.P., Freischlag J.A. Preserving elective surgeries in the COVID-19 pandemic and the future. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;324(17):1725–1726. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdelsattar J.M., Coleman J.R., Nagler A., et al. Julia R., Coleman M.D. MPH. Lived experiences of surgical residents during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative assessment. J Surg Educ. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.04.020. [published online ahead of print, 2021 May 6]. ;S1931-7204(21)00116-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.