Abstract

BACKGROUND

Healthcare workers were prioritized for COVID-19 vaccination roll-out because of the high occupational risk. Vaccine trials excluded individuals who were trying to conceive and those who are pregnant and lactating, necessitating vaccine decision-making in the absence of data specific to this population.

OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to determine the initial attitudes about COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy-capable healthcare workers by reproductive status and occupational exposure.

STUDY DESIGN

We performed a structured survey distributed via social media of US-based healthcare workers involved in patient care since March 2020 who were pregnancy-capable (biologic female sex without history of sterilization or hysterectomy) from January 8, 2021 to January 31, 2021. Participants were asked about their desire to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and their perceived safety of the COVID-19 vaccine using 5-point Likert items with 1 corresponding to “I strongly don't want the vaccine” or “very unsafe for me” and 5 corresponding to “I strongly want the vaccine” or “very safe for me.” We categorized participants into the following 2 groups: (1) reproductive intent (preventing pregnancy vs attempting pregnancy, currently pregnant, or currently lactating), and (2) perceived COVID-19 occupational risk (high vs low). We used descriptive statistics to characterize the respondents and their attitudes about the vaccine. Comparisons between reproductive and COVID-19 risk groups were conducted using Mann-Whitney U tests.

RESULTS

Our survey included 11,405 pregnancy-capable healthcare workers: 51.3% were preventing pregnancy (n=5846) and 48.7% (n=5559) were attempting pregnancy, currently pregnant, and/or lactating. Most respondents (n=8394, 73.6%) had received a vaccine dose at the time of survey completion. Most participants strongly desired vaccination (75.3%) and very few were strongly averse (1.5%). Although the distribution of responses was significantly different between respondents preventing pregnancy and those attempting conception or were pregnant and/or lactating and also between respondents with a high occupational risk and those with a lower occupational risk of COVID-19, the effect sizes were small and the distribution was the same for each group (median, 5; interquartile range, 4–5).

CONCLUSION

Most of the healthcare workers desired vaccination. Negative feelings toward vaccination were uncommon but were significantly higher among those attempting pregnancy and those who are pregnant and lactating and also among those with a lower perceived occupational risk of contracting COVID-19, although the effect size was small. Understanding healthcare workers’ attitudes toward vaccination may help guide interventions to improve vaccine education and uptake in the general population.

Key words: COVID-19, immunization, immunization in pregnancy, SARS-CoV-2, social media, vaccination campaign, vaccine acceptance, vaccine hesitancy, vaccine misinformation

AJOG MFM at a Glance.

Why was this study conducted?

This study aimed to understand vaccine attitudes among pregnancy-capable healthcare workers toward the COVID-19 vaccination.

Key findings

Pregnancy-capable healthcare workers had positive feelings overall in terms of COVID-19 vaccine desirability and safety. The desirability and perceived safety of COVID-19 vaccines among those trying to conceive and those who are pregnant and/or lactating were different from those preventing pregnancy. Respondents with a high perceived occupational risk of contracting COVID-19 perceived the COVID-19 vaccine to be safer than those with a lower perceived occupational risk.

What does this add to what is known?

Vaccine attitude differences among healthcare workers are related to reproductive status and perceived occupational risk, highlighting the importance of targeted vaccine education and counseling in this population.

Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic created a strain on the healthcare system and healthcare workers faced unique burdens of occupational exposures.1 The US Food and Drug Administration granted emergency use authorization (EUA) for the Pfizer/BioNTech (BNT162b2) vaccination based on phase 3 clinical trial data in December 2020,2 and healthcare workers were prioritized for vaccine administration.3 Pregnancy and lactation were exclusion criteria for clinical trial participants,4 and misperceptions that the COVID-19 vaccines could negatively affect fertility spread on social media.5

Because pregnancy is a risk factor for severe disease and increased mortality,6, 7, 8 and theoretical risks of vaccination are low regardless of reproductive status, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended that pregnant and lactating healthcare workers should be offered the vaccination shortly after EUA.9 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine published guidance on the theoretical risks and benefits of vaccination in pregnant and lactating individuals, encouraged shared decision-making, patient autonomy, and access to vaccination, and stated that there were no data to support a negative impact on fertility.10, 11, 12, 13

We aimed to assess the attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination among pregnancy-capable healthcare workers shortly following emergency authorization when limited pregnancy-specific data were available. We hypothesized that the attitudes of healthcare workers preventing pregnancy would differ from those planning to conceive, those who are currently pregnant or those who are lactating because of a lack of data in this population. We also hypothesized that attitudes toward vaccination would be influenced by the perceived risk of occupational exposure to COVID-19.

Materials and Methods

Respondents

We designed a cross-sectional, structured, web-based survey. The survey was written by the research team and piloted by research staff who met the inclusion criteria and were not excluded based on the exclusion criteria. Individuals were eligible if they were pregnancy-capable, a healthcare worker in the United States, had interacted with patients in any capacity since March 2020, and ≥18 years. We defined healthcare workers as anyone employed in a healthcare field who participated in patient contact. Pregnancy-capable was defined as an individual of biologic female sex who had not undergone a sterilization procedure or hysterectomy. Individuals who reported biologic male sex or intersex, were >50 years, did not work in healthcare, had no patient interaction since March 2020, or practiced outside the United States were excluded.

Procedures

Following the screening questions, respondents provided brief demographic and reproductive characteristics and information about their role in healthcare including the area(s) they worked in (inpatient, outpatient, intensive care unit, emergency department, urgent care, labor and delivery, etc.) and the proportion of time spent working with patients both in-person and using telemedicine. Using 5-point Likert item questions, we asked respondents “What best describes your feelings about receiving the vaccine?” with responses ranging from “strongly don't want it” (1) to “strongly want it” (5), and “When considering how safe the vaccine is for you, do you feel it is…” with responses ranging from “very unsafe” (1) to “very safe” (5). For the vaccine safety question, we included an option for “I am unsure about the vaccine's safety” in addition to the five-point Likert item responses, which we collapsed with the middle response, “neither safe nor unsafe” (3) for analysis. We also asked respondents “When considering your risk of contracting COVID-19 at work, do you consider your risk to be…” with response options ranging from “very high risk” (1) to “very low risk” (5). At the end of the survey, respondents were asked to enter a unique, anonymous identifier so that duplicate responses could be removed before analysis.

Recruitment and enrollment

Respondent recruitment was conducted via social media channels (Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook) to obtain a diverse sample of healthcare worker roles, geographies, practice settings, and ages. The original posting with a link to the survey was shared through the department social media accounts; respondents were encouraged to share the link with their colleagues and repost the original recruitment post (ie, snowball sampling). Individuals reviewed a consent information sheet before beginning the survey. Our institution's Human Research Protection Office deemed this study exempt (institutional review board identification number: 202012141) before any recruitment activities.

Data analysis

Data collection and management were conducted using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system.14 , 15 We categorized respondents into 2 reproductive groups, namely those who are (1) preventing pregnancy and (2) attempting pregnancy, currently pregnant, and/or currently lactating. In addition, we categorized respondents into 2 contracting COVID-19 risk groups based on their perception of contracting COVID-19 at work, namely those who are at (1) high risk (those who answered “very high risk” or “somewhat high risk”) and (2) low risk (those who answered “neither high or low risk,” “somewhat low risk,” or “very low risk”). We used descriptive statistics to characterize the respondents and their attitudes about the vaccine. Because of the nonnormal distribution of responses, comparisons between reproductive groups and contracting COVID-19 risk groups were conducted using Mann-Whitney U tests and η2 was calculated to determine effect size. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 27 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Results

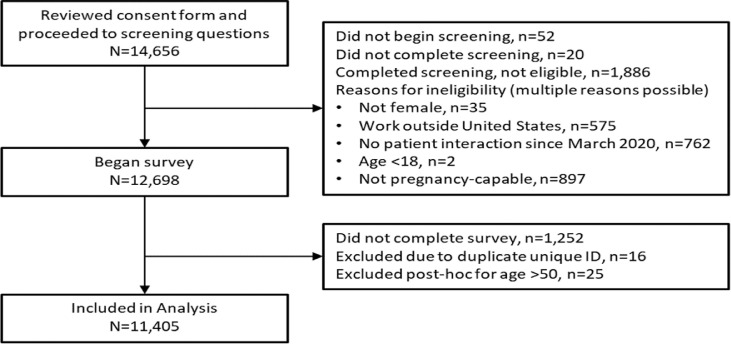

The survey was active from January 8, 2021 to January 31, 2021, and the full enrollment flow is shown in Figure 1 . A total of 11,405 unique respondents were included in our analysis; 51.3% were preventing pregnancy (n=5846) and the remaining 48.7% (n=5559) were attempting pregnancy, currently pregnant, and/or lactating. In the latter group, 955 (17.2%) were attempting pregnancy, 2196 (39.5%) were currently pregnant, 2250 (40.5%) were lactating, 67 (1.2%) were attempting pregnancy and lactating, and 91 (1.6%) were currently pregnant and lactating. The median age of respondents was 32 years, 81.9% were White, and approximately one-third (34.8%) were nurses (Table ). Most (91.8%) respondents said their workplace offered the COVID-19 vaccine, and 73.6% had received it at the time of survey completion. Among the respondents who felt neutral or negatively about desiring the vaccine, individuals who were Black, multiracial, or who declined to provide their race were overrepresented, reflecting the trends seen in the general population (data not shown). We observed similar patterns among respondents who had neutral or negative feelings regarding the vaccine's safety; Hispanic patients were also overrepresented among respondents in this group (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Enrollment flow of interested subjects to final respondents included in the analysis

Perez. COVID-19 vaccine attitudes in healthcare workers. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021.

Table.

Respondent characteristics of pregnancy-capable healthcare workers who worked with patients during the COVID-19 pandemic

| Characteristic | N=11,405 |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 32 (29–35) |

| Race | |

| African-American | 122 (1.1) |

| White | 10,157 (89.1) |

| Asian | 528 (4.6) |

| Native American or American Indian | 53 (0.5) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 20 (0.2) |

| Other or multiracial | 485 (4.3) |

| Refused | 40 (0.4) |

| Hispanic | 790 (6.9) |

| Region | |

| Pacific or Alaska or Hawaii | 1703 (14.9) |

| Mountain west | 478 (4.2) |

| Southwest | 1049 (9.2) |

| Midwest | 3585 (31.4) |

| Southeast | 2489 (21.8) |

| Northeast | 2091 (18.3) |

| Refused | 10 (0.1) |

| Had COVID-19 | |

| Yes, positive test | 992 (8.7) |

| Had symptoms (never tested or test was negative) | 1690 (14.8) |

| No | 8723 (76.5) |

| Household member with COVID-19 | |

| Yes, positive test | 1111 (9.7) |

| Had symptoms (never tested or test was negative) | 1104 (9.7) |

| No | 9190 (80.6) |

| Healthcare role | |

| Nurse (RN/BSN) | 3965 (34.8) |

| Advanced Practice Practitioner (NP or PA) | 1640 (14.4) |

| Physician | 1262 (11.1) |

| Othera | 4538 (39.7) |

| Workplace offering COVID-19 vaccine | 10,469 (91.8) |

| Received COVID-19 vaccine | 8394 (73.6) |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) and number (percentage); percentages may not add to 100 because of rounding.

BSN, Bachelor of Science in Nursing; NP, nurse practioner; PA, physician assistant; RN, registered nurse.

The other group comprised over 40 roles; each comprised <10% of respondents.

Perez. COVID-19 vaccine attitudes in healthcare workers. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021.

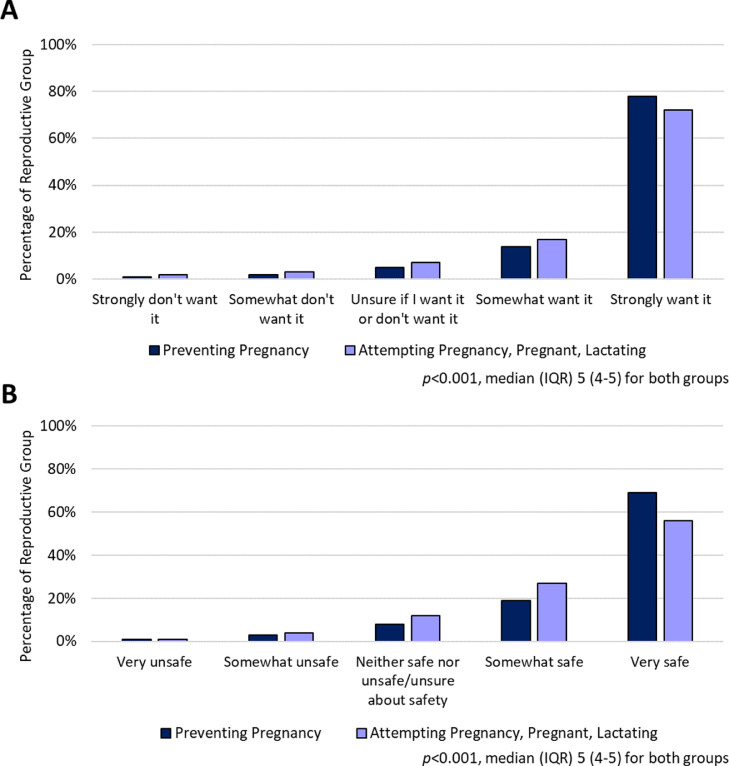

Most participants strongly desired vaccination (75.3%) and very few were strongly averse (1.5%). Although the distribution was significantly different among reproductive groups (Figure 2 , A), the effect size was small, and the median and interquartile range were the same (P<.001; η2=0.005; median, 5, interquartile range, 4–5). When we asked respondents about the safety of the vaccine (Figure 2, B), we observed similar results (P<.001; η2=0.018; median, 5; interquartile range, 4–5).

Figure 2.

Vaccine attitudes by participants' reproductive status

Distribution of responses to questions about the desire to receive the vaccine (A) and perceived vaccine safety (B) between respondents preventing pregnancy and those who are attempting pregnancy, are currently pregnant, and/or lactating.

IQR, interquartile range.

Perez. COVID-19 vaccine attitudes in healthcare workers. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021.

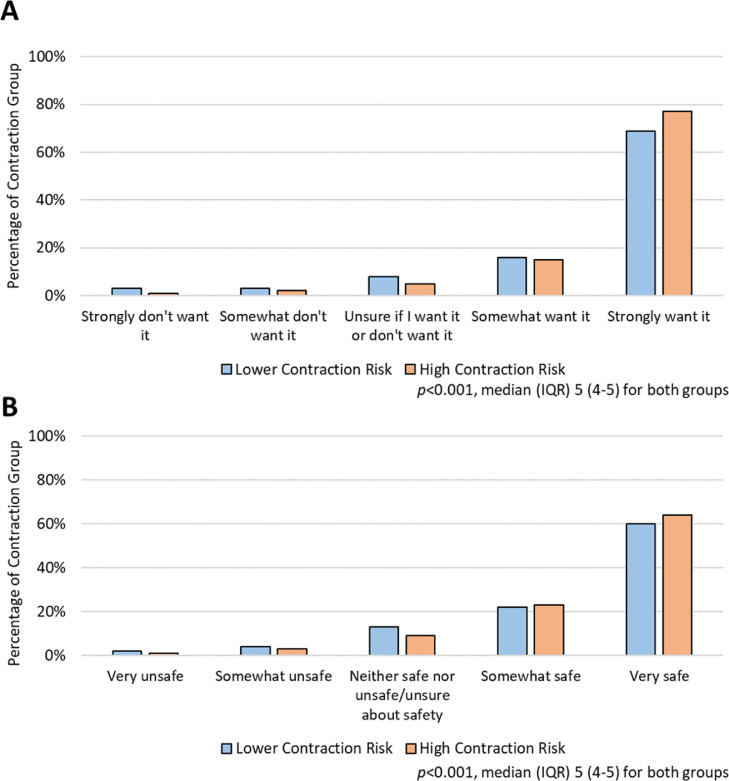

Three-quarters of the respondents (74.6%) believed that they were at high risk of contracting COVID-19 at work. When we examined the responses on vaccination desire stratified by high vs lower occupational risk of contracting COVID-19 (Figure 3 , A), there was a significant difference in the distribution, but the effect size was small (P<.001; η2=0.009). The same pattern was observed for the perceived safety of vaccination stratified by occupational risk (P<.001; η2=0.002) (Figure 3, B). For each group, the median (interquartile range) of the distribution was 5 (4–5).

Figure 3.

Vaccine attitudes by participants' perceived occupational exposure risk.

Distribution of responses to questions about the desire to receive the vaccine (A) and perceived vaccine safety (B) between respondents who considered themselves at high risk of occupational COVID-19 exposure and those at lower occupational risk.

IQR, interquartile range.

Perez. COVID-19 vaccine attitudes in healthcare workers. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021.

Among the participants who were unvaccinated at the time of the survey (n=2075), 68.1% were attempting conception, were pregnant, or lactating, 39.3% strongly desired vaccination, and 28.4% thought the vaccination was very safe.

Discussion

Principal findings

Most pregnancy-capable healthcare workers in our January 2021 survey strongly desired vaccination. Negative feelings toward vaccination were not common but were higher among healthcare workers attempting conception and those who were pregnant or lactating than among those preventing pregnancy. Participants with a higher perceived occupational exposure risk to COVID-19 more strongly desired vaccination than those with a lower perceived occupational risk.

Results

Our findings describing the impact of reproductive status and occupational risk of healthcare workers on vaccine attitudes adds to the data on vaccine attitudes in both general and healthcare worker populations. Surveys assessing attitudes about receiving a COVID-19 vaccine report increased hesitancy among women than among men, including among healthcare workers.16, 17, 18 Differences in reproductive status may account for some of these sex differences: several recently published surveys of reproductive-aged females, including healthcare workers, show that individuals who are trying to conceive and those who are pregnant or lactating are less likely to accept vaccination and are more likely to delay or decline vaccination.19, 20, 21

Our findings demonstrate that the reproductive status of healthcare workers could influence vaccine attitudes, suggesting that medical knowledge does not fully combat vaccine hesitancy. Sutton et al19 found that women who accepted vaccination reported that seeing healthcare workers receiving COVID-19 vaccines factored into their decision to accept vaccination. Although vaccine attitudes may be similar between healthcare workers and nonhealthcare workers, the general population may be guided by the decisions of healthcare workers. Overall, our population of pregnancy-capable healthcare workers had positive feelings toward vaccination and considered it safe. Although participants attempting conception and those who are pregnant and/or lactating were not as strongly convinced of safety, possibly because individuals with these reproductive statuses were not included in clinical trial, the effect sizes were small. There was also a relationship between occupational exposure risk and vaccine desire and perceived safety, but the small effect sizes indicate that the finding may not be clinically relevant.

Clinical implications

Pregnant and lactating individuals are excluded from vaccine clinical trials in an attempt to protect the pregnant or lactating person and fetus or infant from unanticipated adverse events. However, during a pandemic in which pregnant individuals are a high-risk group for severe disease, these exclusions have the opposite effect. Exclusion leaves pregnancy-capable populations without data to make informed decisions, delaying important data pertaining to efficacy and safety. At the time of manuscript writing, <1 in 4 pregnant people were vaccinated against COVID-19 despite retrospective data showing safety, efficacy, and vaccine-generated antibody passage through umbilical cord blood and breastmilk.22, 23, 24, 25 Although the data are reassuring, had it been available when the vaccines were first released, its impact would have been more substantial. Targeted education to reproductive-aged populations is needed to battle vaccine misinformation related to fertility. Vaccine hesitancy and decline leave patients at risk for COVID-19 and a lack of data creates opportunities for antivaccine misinformation.

Research implications

We identified reproductive status as a possible driver behind the established differences in vaccine attitudes among female sex individuals, even among healthcare workers who may have higher health literacy. Further investigation should focus on understanding vaccine hesitancy, countering vaccine misinformation, and strategies for education and counseling to address vaccine attitudes among those trying to conceive and those who are pregnant and lactating.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study include a large sample size, particularly in the context of survey studies about COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.17, 18, 19 , 21 , 26 , 27 Our respondents represented varied geographies and roles in healthcare. We included respondents with a wide range of reproductive statuses, including those who are trying to conceive and those who are lactating in addition to a large comparison group that was preventing pregnancy. Furthermore, the respondents comprised a group at high risk for occupational exposure and provided responses during a time point when data regarding vaccination safety in pregnancy were lacking, but pregnancy clearly had been linked to severe COVID-19 disease course.

There are limitations to our study. The nature of a web-based, social-media recruitment strategy leaves us unable to calculate a response rate. However, our completion rate among eligible respondents was >90%. A web-based recruitment and survey strategy requires internet access, and social media snowball recruitment may increase responsiveness within particular social networks and online communities, limiting the generalizability of our results. White, non-Hispanic respondents were overrepresented in our sample, and our recruitment strategies did not have the same reach in communities of color. This may bias our results, because communities of color have higher rates of COVID-19 cases and mortality28 and typically report lower vaccine acceptance in surveys.17 , 18 Individuals with strong feelings about vaccination could be more likely to participate, and most of our respondents had already been vaccinated at the time of the survey, leading to selection bias. Our survey was created during a novel pandemic and vaccination roll-out, therefore it is not a validated survey instrument.

Conclusions

Our results show that the reproductive status of pregnancy-capable healthcare providers has a small but significant effect on the desire for vaccination and the perceived safety of the vaccination. A higher perceived occupational risk of exposure to COVID-19 also had a small but significant effect on the desire for vaccination among healthcare workers. Given that vaccine attitudes differ significantly, even among a medically literate, high-risk group of people, further exploration of vaccine attitudes and acceptance in this population is needed.

Footnotes

M.J.P. reports receiving funds from Bayer Pharmaceuticals for serving on the Speaker Bureau (2019). The other authors report no conflict of interest.

This study did not receive any funding.

Cite this article as: Perez MJ, Paul R, Raghuraman N, et al. Characterizing initial COVID-19 vaccine attitudes among pregnancy-capable healthcare workers. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021;XX:x.ex–x.ex.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100557.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Video COVID-19 vaccine in healthcare workers

Perez. COVID-19 vaccine attitudes in healthcare workers. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021.

References

- 1.Ripp J, Peccoralo L, Charney D. Attending to the emotional well-being of the health care workforce in a New York City Health System during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Med. 2020;95:1136–1139. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfizer and BioNTech . 2020. Pfizer and BioNTech conclude Phase 3 study of COVID-19 vaccine candidate, meeting all primary efficacy endpoints.https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer-and-biontech-conclude-phase-3-study-covid-19-vaccine Available at: Accessed March 16, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mbaeyi S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; 2020. COVID-19 vaccine prioritization: work group considerations.https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2020-07/COVID-07-Mbaeyi-508.pdf Available at: Accessed March 16, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.A phase 1/2/3, placebo-controlled, randomized, observer-blind, dose-finding study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, immunogenicity, and efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 RNA vaccine candidates against COVID-19 inhealthy individuals. New York: Pfizer/BioNTech; 2020.https://cdn.pfizer.com/pfizercom/2020-11/C4591001_Clinical_Protocol_Nov2020.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2021.

- 5.Wu KJ. The New York Times; 2020. No, there isn't evidence that Pfizer's vaccine causes infertility.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/10/technology/pfizer-vaccine-infertility-disinformation.html Available at. Accessed February 2, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delahoy MJ, Whitaker M, O'Halloran A, et al. Characteristics and maternal and birth outcomes of hospitalized pregnant women with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 - COVID-NET, 13 states, March 1-August 22, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1347–1354. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6938e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panagiotakopoulous L, Myers TR, Gee J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection among hospitalized pregnant women: reasons for admission and pregnancy characteristics - eight U.S. Health Care Centers, March 1-May 30, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1355–1359. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6938e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zambrano LD, Ellington S, Strid P, et al. Update: characteristics of symptomatic women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status - United States, January 22-October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1641–1647. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6944e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleland K, Peipert JF, Westhoff C, Spear S, Trussell J. Family planning as a cost-saving preventive health service. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:e37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1104373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . 2020. COVID-19 vaccination considerations for Obstetric-Gynecologic care.https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2020/12/vaccinating-pregnant-and-lactating-patients-against-covid-19 Available at: Accessed August 3, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine . 2020. Statement: SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in pregnancy.https://s3.amazonaws.com/cdn.smfm.org/media/2591/SMFM_Vaccine_Statement_12-1-20_(final).pdf Available at: Accessed August 3, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Society for Reproductive Medicine . 2020. American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) patient management and clinical recommendations during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic Update No. 11.https://www.asrm.org/globalassets/asrm/asrm-content/news-and-publications/covid-19/covidtaskforceupdate11.pdf Available at: Accessed August 3, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reeves MF, Zhao Q, Secura GM, Peipert JF. Risk of unintended pregnancy based on intended compared to actual contraceptive use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.01.162. 71.e1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95 doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang K, Wong ELY, Ho KF, et al. Intention of nurses to accept coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination and change of intention to accept seasonal influenza vaccination during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey. Vaccine. 2020;38:7049–7056. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreps S, Prasad S, Brownstein JS, et al. Factors associated with US adults’ likelihood of accepting COVID-19 vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ciardi F, Menon V, Jensen JL, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare workers of an inner-city hospital in New York. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9:516. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutton D, D'Alton M, Zhang Y, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant, breastfeeding, and nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021;3 doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turocy J, Robles A, Reshef E, D'Alton M, Forman EJ, Williams Z. 2021. A survey of fertility patients’ attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccine.https://www.fertstertdialog.com/posts/a-survey-of-fertility-patients-attitudes-towards-the-covid-19-vaccine Available at: Accessed February 2, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Townsel C, Moniz MH, Wagner AL, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among reproductive-aged female tier 1A healthcare workers in a United States Medical Center. J Perinatol. 2021;41:2549–2551. doi: 10.1038/s41372-021-01173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beharier O, Plitman Mayo R, Raz T, et al. Efficient maternal to neonatal transfer of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. J Clin Invest. 2021;131 doi: 10.1172/JCI150319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray KJ, Bordt EA, Atyeo C, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine response in pregnant and lactating women: a cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.023. 303.e1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly JC, Carter EB, Raghuraman N, et al. Anti-severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 antibodies induced in breast milk after Pfizer-BioNTech/BNT162b2 vaccination. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:101–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Razzaghi H, Meghani M, Pingali C, et al. COVID-19 vaccination coverage among pregnant women during pregnancy - eight integrated health care organizations, United States, December 14, 2020-May 8, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:895–899. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7024e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biswas N, Mustapha T, Khubchandani J, Price JH. The nature and extent of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in healthcare workers. J Commun Health. 2021;46:1244–1251. doi: 10.1007/s10900-021-00984-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwarzinger M, Watson V, Arwidson P, Alla F, Luchini S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a representative working-age population in France: a survey experiment based on vaccine characteristics. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6:e210–e221. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00012-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bibbins-Domingo K. This time must be different: disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:233–234. doi: 10.7326/M20-2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video COVID-19 vaccine in healthcare workers

Perez. COVID-19 vaccine attitudes in healthcare workers. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021.