Abstract

Few studies have used a multidimensional acculturation framework, i.e., cultural practices, identity, and values, to investigate links with alcohol or drug use of Latinx immigrants to the U.S. This cross-sectional study tested links between measures of acculturation (language-based Hispanicism and Americanism, cultural identity, familism), acculturative stress, and alcohol or drug use, controlling for age and gender. 391 adult (18–44 years old) Latinx immigrants (69% women) completed measures on past 6-month behavior in Spanish or English. Results showed that Americanism was related to alcohol use severity, heavy episodic drinking, drug use severity, and any drug use. Acculturative stress was related to alcohol use severity, drug use severity, and any drug use, but not heavy episodic drinking. Familism was inversely related to drug use severity and any drug use, but not alcohol use severity or heavy episodic drinking. Cultural identity and Hispanicism were not related to alcohol or drug use. Consistent with previous research, a language-based measure of acculturation to the U.S. (Americanism) and acculturative stress were related to alcohol and drug use. Incremental validity of a multidimensional acculturation approach was limited. Intervention adaptations for Latinx immigrants should address stress reduction and mitigating adoption of receiving cultural practices.

Keywords: Latinx/Hispanic, immigrants, alcohol, drugs, acculturation, acculturative stress

Latinx people, a heterogeneous group from many cultures, histories, and national origins, grew 23% since 2010, and is now the largest (~ 62 million, 18.5%) U.S. ethnic minority (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). Most (79%) Latinx people are U.S. citizens, and about a third (33%) immigrants; the majority (78%) of immigrants lived in the U.S. for 10+ years (Noe-Bustamante, 2019). Research is needed to inform health care and improve the health of this growing yet underserved group, in particular alcohol and drug causes serious health consequences, including death. Recent estimates (SAMHSA, 2020) show 31% of Latinx young adults (18 – 25 years old) reported past-month heavy episodic drinking (5+ drinks for men/4+ for women) compared to 40% of non-Latinx white counterparts, but Latinx adults (26+ years old) had similar rates (26% to 25%) to non-Latinx whites. Past-year alcohol use disorder rates were similar for young adults (9% Latinx, 11% non-Latinx white) and adults (4% Latinx, 5% non-Latinx white). Past-month illicit drug use rates were lower for Latinx young adults (22% Latinx, 26% non-Latinx white) and adults (9% Latinx, 12% non-Latinx white), but past-year drug use disorder rates were similar for young adults (4% Latinx, 5% non-Latinx white) and adults (1% Latinx, 2% non-Latinx white).

Although Latinx adults do not drink or use drugs at higher rates than non-Latinx whites, they have greater related consequences and health problems, including intimate partner violence (Caetano & Galvan, 2001; Morales-Aleman et al., 2014), liver cirrhosis mortality (Flores et al., 2008), criminal justice involvement (Iguchi et al., 2002), treatment barriers (Campbell & Alexander, 2002; Guerrero et al., 2013; Marsh et al., 2009), injuries and arrests from intoxicated driving (e.g., Valdez et al., 2018; Vaeth et al., 2017). Although U.S. Latinx immigrants are heterogeneous, understanding shared culturally-based factors, e.g., acculturation and acculturative stress, may lead to effective programming to modify sociocultural determinants of alcohol or drug use and prevent disparate consequences.

Acculturation refers to changes from contact with a culturally dissimilar society, often for those living apart from where they were born (Berry, 2006). Acculturation was originally conceptualized on a single dimension, i.e., immigrants acquired the values, practices, and beliefs of the receiving culture, and discarded their heritage cultural values, practices, and beliefs. Biculturalism, with independent dimensions of acquiring the receiving-culture (acculturation or Americanism in this study) and retaining the heritage culture (enculturation or Hispanicism), supplanted the unidimensional concept (Berry, 1988; Berry, 2003). Potentially low or high scores on either dimension led to four descriptive categories: assimilation (adopting the receiving culture while discarding the heritage culture), separation (rejecting the receiving culture and retaining the heritage culture), integration (adopting the receiving culture and retaining the heritage culture), and marginalization (rejecting both heritage and receiving cultures). A multidimensional acculturation framework suggested a person may be stable or changing along multiple dimensions: cultural practices including language or media preferences; cultural values such as familism; and cultural identifications with an ethnicity (Schwartz et al., 2010; Phinney, 1996; Shore, 2002; Triandis, 1995).

Acculturative stress is a distinct, but related construct, referring to culturally-based stressors including discrimination, context of reception, and bicultural stress (Cervantes et al., 2012; Salas-Wright & Schwartz, 2019). Discrimination is being excluded, attacked, and/or viewed suspiciously due to ethnicity (e.g., Greene et al. 2006). Context of reception refers to the opportunity structure that immigrants encounter (e.g., Portes & Rumbaut, 2014). Bicultural stress is the conflict between expectations and demands imposed by two cultures (e.g., Romero & Roberts, 2003). Acculturative stressors likely co-occur in U.S. Latinx immigrants; the accumulation of multiple stressors is likely more hurtful than any single stressor (Córdova & Cervantes, 2010; Ennis et al., 2011; Salas-Wright & Schwartz, 2019).

Acculturation and acculturative stress have theoretical links to alcohol or drug use. Acculturation may lead to adopting permissive attitudes or normative beliefs about drinking or drug use; retaining heritage practices and cultural identity may have the opposite effect (e.g., Caetano, 1987). In a meta-analysis of 88 samples of 68,282 Latinx adults (Lui & Zamboanga, 2018), acculturation was not linked to drinking frequency or volume (rs = .01, .02), but was positively related to drinking intensity (r = .09), heavy episodic drinking (r = .05), and hazardous drinking (r = .06). Acculturative stress may lead to maladaptive coping with alcohol or drug use to emotionally disengage when stress appears insurmountable (e.g., Carver, 1989; Crocket et al., 2007). Further, acculturative stress may disrupt protective aspects of family functioning. Familism refers to the importance of one’s family or placing family needs above individual needs. Familism creates a sense of obligation of family care and consideration when making decisions, and is believed to protect against unhealthy behaviors, including alcohol or drug use (De la Rosa et al., 2005). Acculturative stress in Latinx adults has been linked to substance use disorders (Ehlers et al., 2009), drinking problems (Lee et al., 2013), hazardous drinking (Jankowski et al., 2020), and alcohol use (Sanchez et al., 2015); and to alcohol and polysubstance use in Latinx adolescents (Goldbach et al., 2016; Berger-Cardoso et al., 2016), although acculturative stress failed to differentiate drinking patterns of Latinx clients in treatment in one study (Arciniega et al., 1996).

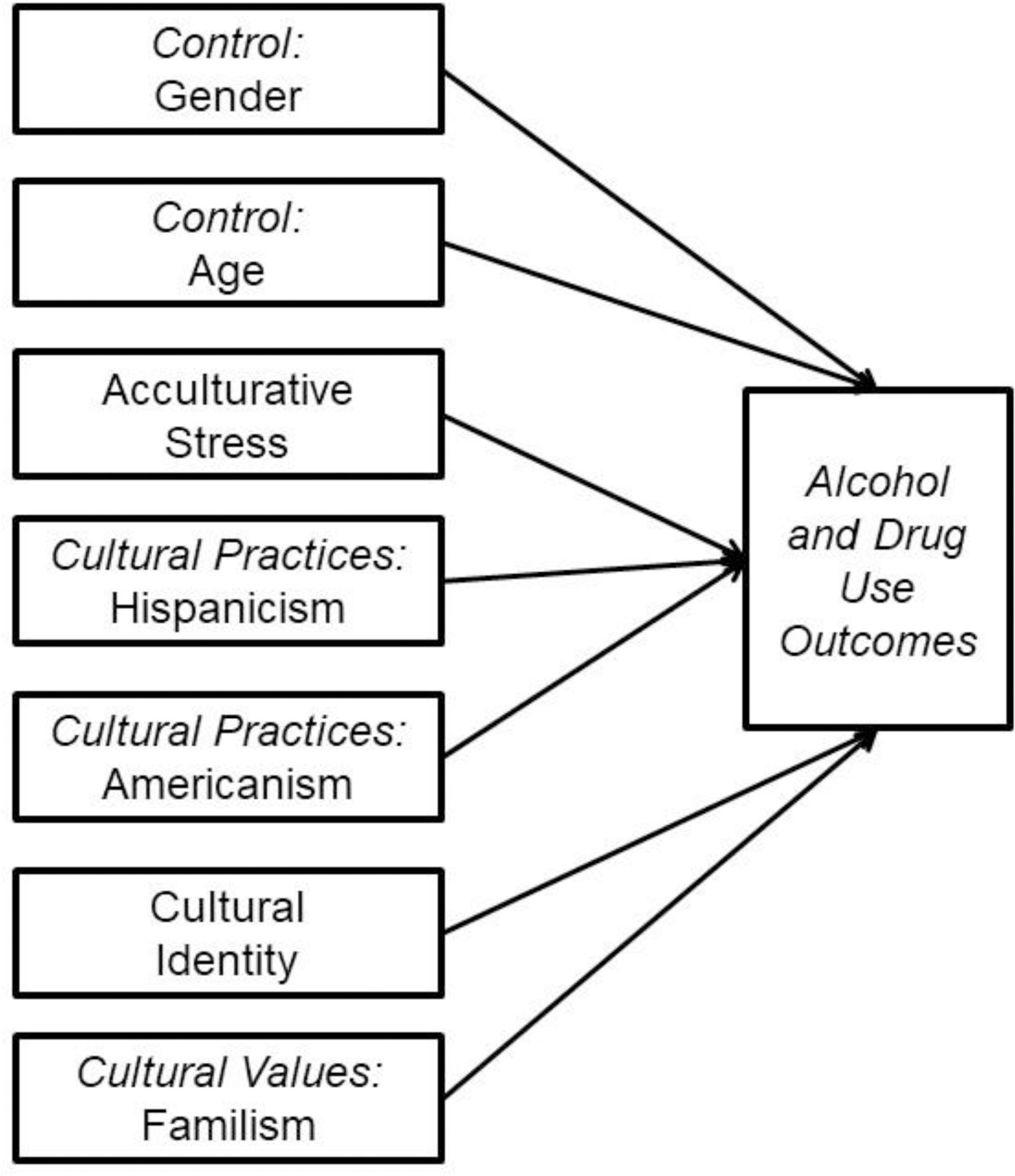

Although acculturation and acculturative stress separately relate to alcohol or drug use of U.S. Latinx immigrants, few studies used a multidimensional approach to acculturation or examined combined effects of both constructs. Investigating multiple dimensions can provide nuanced understanding of constructs that may change in different ways or at different rates, build on successfully moving from a unidimensional to a bidimensional approach, and integrate generally separate literatures on cultural practices, values, and identity (Schwartz et al., 2010; Yoon et al., 2020). Greater understanding of acculturation and acculturative stress may inform novel or adapted interventions to reduce or prevent alcohol and drug use and related harms for U.S. Latinx immigrants. This study will expand on past work by testing links between four acculturation measures [cultural practices (Hispanicism and Americanism), identity, and values] and acculturative stress with alcohol and drug use in adult Latinx immigrants, controlling for age and gender. Controls were selected due to consistent findings for adults, i.e., age is inversely related to alcohol and drug use, and women use alcohol and drugs less than men. We hypothesized that acculturative stress and Americanism (acculturation) will be positively related to alcohol and drug use, but Hispanicism (enculturation), familism, and cultural identity will be inversely related to alcohol and drug use.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 391 adult Latinx immigrants in North Carolina completing the baseline assessment of a community-based study of acculturation and health [SER (Salud, Estres, y Resiliencia)] between May 2018 and December 2019. Power analysis in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2002) showed this N resulted in >80% power to find medium-size (.5) relationships between latent slopes over time for primary analyses. 701 participants were screened using eligibility criteria: (a) identify as Hispanic or Latino/Latina/Latinx; (b) emigrate from a Spanish-speaking country in Latin America or the Caribbean; (c) living in the U.S. for at least 1 year; and (d) 18 to 44 years old. The Duke University Institutional Review Board approved all activities. Participants received $50 for the assessment. Table 1 shows participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N = 391).

| Characteristic | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 33.86 | 6.94 |

| Years in US | 13.49 | 7.04 |

| Age of immigration | 19.94 | 8.50 |

| Education | 11.45 | 4.00 |

| Acculturative Stress | 23.32 | 14.13 |

| Hispanicism | 3.42 | 0.35 |

| Americanism | 2.54 | 0.85 |

| Cultural Identity | 3.03 | 0.59 |

| Familism | 3.49 | 0.46 |

| Alcohol Use Severity | 3.81 | 5.05 |

| Drug Use Severity | 0.18 | 0.87 |

|

|

||

| n | % | |

|

|

||

| Women | 269 | 69% |

| Employed | 289 | 74% |

| Married/Has Partner | 280 | 72% |

| Spanish Preferred | 324 | 83% |

| Heavy Episodic Drinking | 143 | 37% |

| Any Drug Use | 28 | 7% |

Note. Hispanicism = enculturation; Americanism = acculturation.

Measures

All measures were in English and Spanish and administered by bilingual (Spanish and English) and bicultural staff.

Control variables were age (years) and gender, coded as woman = 1 (vs man = 0).

Acculturative Stress.

The Hispanic Stress Inventory-2 Immigrant Version (Cervantes et al., 2016) has 90 items to measure 10 facets of acculturative stress: Parental, Occupation and Economic, Marital, Discrimination, Immigration-Related, Marital Acculturation Gap, Health, Language-Related, Pre-Migration, and Family-Related. Participants first endorse whether an event happened in the past six months (frequency), then if an event happened the participant rates how worried or tense (appraisal) on a 5-point Likert scale (1 not at all to 5 extremely). We used the total frequency scale to count stressful events, resulting in a potential range of 0 – 90 with higher scores meaning more acculturative stress; internal consistency was strong, Cronbach’s α = .93.

Acculturation.

We assessed four acculturation dimensions: cultural practices (Hispanicism and Americanism), cultural identity, and cultural values (familism).

Hispanicism and Americanism.

The Bidimensional Acculturation Scale (Marın & Gamba, 1996) has 24 items on two dimensions, affinity with culture of origin practices (Hispanicism/enculturation) and affinity with U.S. cultural practices (Americanism/acculturation). The 12 items in each cultural domain are based on language preference in conversation, entertainment, etc. Items have a 4-point Likert scale, 1 almost never to 4 almost always. Both scales were averaged, resulting in a potential range of 1 to 4 with the mid-point of 2.5 as a cutoff for high values. Hispanicism and Americanism subscales had acceptable internal consistency, αs = .70 and .96, respectively.

Cultural Identity.

The Multigroup Ethnic Identification Measure (Phinney, 1992) has 12 items on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. This measure assesses heritage culture identification, i.e., how much one (a) has considered the subjective meaning of one’s race/ethnicity and, (b) feels positively about one’s racial/ethnic group. Example items are, “I have a clear sense of my ethnic background and what it means for me,” and “I participate in cultural practices of my own group, such as special food, music, and customs.” Items were averaged into a single cultural identity measure, with a possible range from 1 to 5; higher scores meant greater identification with Latinx/Hispanic culture. Participants responded regarding Latinx/Hispanic ethnic identity, although they may have multiple ethnic/racial identities. The scale had strong internal consistency, α = .90. Although this measure can be scored with two subscales, exploration and affirmation, Phinney and Ong (2007) recommended a single factor.

Familism.

The 15-item Familism Scale (Sabogal et al., 1987) has items on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree. This measure assesses familial obligations, e.g., “One should make great sacrifices in order to guarantee a good education for his/her children;” family support, e.g., “One can count on help from his/her relatives to solve most problems;” and family as referents, e.g., “Much of what a son or daughter does should be done to please the parents.” Items were averaged into unidimensional familism, with a potential range of 1 to 5 such that higher scores meant greater familism, which had acceptable internal consistency, α = .76.

Alcohol Use.

The US-AUDIT, a revised version of the widely used alcohol screening measure, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 2014; Babor et al., 2017) assessed alcohol use. This version changed the wording of some items for the U.S., e.g., using five drinks (men) and four (women) to correspond with heavy episodic drinking using U.S. standard drinks. Participants saw a standard drink chart (tabla de bebidas estandar) with 12oz. beer can, a 5oz. wine glass, and a 1.5oz shot glass. This measure has 10 items about alcohol use, alcohol use disorder symptoms, and alcohol-related problems in the past six months. The first three item responses are scaled from 0 – 6, and the last seven from 0 – 4, resulting in a possible range from 0 – 46 for the total score. For alcohol use severity, the cutoff for excess drinking is 7 (women)/8 (men). For analysis, we used a continuous score to represent alcohol use severity, and a dichotomous heavy episodic drinking variable, created from the response to one question “How often do you have X (5 men/4 women) or more drinks on one occasion?” Possible responses ranged from 0 never, 1 less than monthly to 6 daily; heavy episodic drinking was coded as 0 = never vs. 1 = any other response. Internal consistency reliability of the total score was acceptable, Cronbach’s α = .82.

Drug Use.

To assess drug use, we used a 10-item screening measure, the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10; Skinner, 1982). Participants responded about non-medical use of drugs, not alcohol, using either yes or no for the previous six months. Example drugs were cannabis (marijuana, hashish), solvents (e.g., paint thinner), tranquilizers (e.g., Valium), barbiturates, cocaine, stimulants (e.g., speed), hallucinogens (e.g., LSD) or narcotics (e.g., heroin), and could include prescribed or over-the-counter drugs. For analysis, we used a continuous total score to represent drug use severity, and a dichotomous any drug use variable, created from the response to one question, “Have you used drugs other than those required for medical reasons?” For drug use severity, the cutoff for moderate misuse is three. Internal consistency of the total score was acceptable, α = .84.

Analysis Plan

Path analysis in Mplus 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) tested hypotheses, which produced standardized coefficients (β) to compare strength of association across predictors and outcomes with different ranges (see Figure). Maximum likelihood estimation allowed inclusion of all cases regardless of missing outcomes, although missing data was <3% and unlikely to bias estimates (Graham, 2009). All analyses controlled for gender and age. We defined alcohol and drug use in two ways as a partial check on robustness of findings. Negative binomial analyses were used for alcohol and drug use severity because both were skewed, and logistic analysis for dichotomous heavy episodic drinking and drug use.

Figure.

Hypothesized conceptual model for each path analysis. Alcohol use outcomes were alcohol use severity and heavy episodic drinking; drug use outcomes were drug use severity and any drug use.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The majority (69%) were women (Table 1). Most were employed (74%) and preferred Spanish (83%). The average years of education, M = 11.45, was almost equivalent to a high school. On average, participants had been in the U.S. for just over a decade, M = 13.49, and arrived in early adulthood, M = 19.00 years. Overall, based on the possible scale ranges, participants had high Hispanicism, M = 3.42, Latinx/Hispanic cultural identity, M = 3.03, and familism, M = 3.49, mid-range Americanism, M = 2.54, and low acculturative stress, M = 23.32. About 2/3 (65%) had elevations on at least one acculturative stress facet, and the mean total appraisal T-score was 55.44, just above average based on developer norms (Cervantes et al., 2016). On average, alcohol use severity, M = 3.81, and drug use severity, M = 0.18, scores were low (Babor et al., 2016; Skinner, 1982), although over a third (37%) reported heavy episodic drinking and under a tenth (7%) had used illicit drugs.

Control Variables

Gender was inversely related, i.e., woman lower than men, to alcohol use severity, β = −.30, heavy episodic drinking, β = −.15, drug use severity, β = −.25, and any drug use, β = −.33. Age was inversely related to alcohol use severity, β = −.54, heavy episodic drinking, β = −.12, drug use severity, β = −.49, and any drug use, β = −.24.

Alcohol Use

Acculturative stress was related to alcohol use severity, β = .30, but not heavy episodic drinking, β = .12. Americanism was related to alcohol use severity, β = .60, and heavy episodic drinking, β = .29. Hispanicism, cultural identity, and familism were not related to either alcohol use severity or heavy episodic drinking. Table 2 shows results for alcohol use.

Table 2.

Relationships of Multidimensional Acculturation and Acculturation Stress with Alcohol Use.

| Alcohol Use Severity |

Heavy Episodic Drinking |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | b | SE | β | 95% CI | p | b | SE | β | 95% CI | p | ||

| Woman | −0.02 | 0.01 | −.30 | −0.04 | 0.00 | .041 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −.15 | −0.07 | −0.01 | .015 |

| Age, years | −0.61 | 0.15 | −.54 | −0.90 | −0.32 | <.001 | −0.49 | 0.24 | −.12 | −0.96 | −0.02 | .042 |

| Acculturative Stress | 0.02 | 0.01 | .51 | 0.01 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.02 | 0.01 | .12 | 0.00 | 0.03 | .052 |

| Hispanicism | 0.04 | 0.21 | .03 | −0.36 | 0.45 | .836 | 0.18 | 0.35 | .03 | −0.51 | 0.86 | .617 |

| Americanism | 0.37 | 0.10 | .60 | 0.17 | 0.57 | <.001 | 0.66 | 0.16 | .29 | 0.35 | 0.97 | <.001 |

| Cultural Identity | 0.04 | 0.13 | .05 | −0.22 | 0.30 | .764 | −0.08 | 0.20 | −.02 | −0.47 | 0.31 | .694 |

| Familism | 0.07 | 0.15 | .06 | −0.23 | 0.36 | .654 | −0.02 | 0.25 | .00 | −0.52 | 0.48 | .941 |

Note. Significant relationships are in bold. Hispanicism = enculturation; Americanism = acculturation.

Drug Use

Acculturative stress was related to drug use severity, β = .27, and any drug use, β = .20. Americanism was related to drug use severity, β = .57, and any drug use, β = .42. Familism was inversely related to drug use severity, β = −.24, and any drug use, β = −.25. Hispanicism and cultural identity were not related to either. Table 3 shows the full results for drug use.

Table 3.

Relationships of Multidimensional Acculturation and Acculturation Stress with Drug Use.

| Drug Use Severity |

Any Drug Use |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | b | SE | β | 95% CI | p | b | SE | β | 95% CI | p | ||

| Woman | −0.08 | 0.04 | −.25 | −0.15 | −0.01 | .025 | −0.13 | 0.04 | −.33 | −0.20 | −0.05 | .001 |

| Age, years | −2.32 | 0.56 | −.49 | −3.42 | −1.23 | <.001 | −1.42 | 0.49 | −.24 | −2.38 | −0.45 | .004 |

| Acculturative Stress | 0.04 | 0.02 | .27 | 0.01 | 0.08 | .021 | 0.04 | 0.02 | .20 | 0.01 | 0.07 | .022 |

| Hispanicism | −0.94 | 0.77 | −.15 | −2.45 | 0.56 | .219 | −0.48 | 0.66 | −.06 | −1.77 | 0.81 | .466 |

| Americanism | 1.47 | 0.43 | .57 | 0.63 | 2.30 | .001 | 1.35 | 0.41 | .42 | 0.54 | 2.16 | .001 |

| Cultural Identity | 0.61 | 0.44 | .17 | −0.26 | 1.48 | .172 | 0.52 | 0.43 | .11 | −0.32 | 1.36 | .225 |

| Familism | −1.16 | 0.58 | −.24 | −2.29 | −0.02 | .046 | −1.49 | 0.54 | −.25 | −2.54 | −0.44 | .005 |

Note. Significant relationships are in bold. Hispanicism = enculturation; Americanism = acculturation.

Discussion

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to use a multidimensional acculturation approach to test relationships between cultural practices (Americanism and Hispanicism), cultural identity, and cultural values (familism) and alcohol and drug use of Latinx adult immigrants. Participants had low alcohol and drug use severity, although many reported heavy episodic drinking. Consistent with previous research (e.g., Lui & Zamboanga, 2018; Ehlers et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2013; Jankowski et al., 2020; Sanchez et al., 2015), language-based acculturation (Americanism) and acculturative stress were related to alcohol and drug use. The incremental predictive validity of a multidimensional acculturation approach was limited. Familism was inversely related to drug use, but not alcohol. Language-based enculturation (Hispanicism) and cultural identity were not related to alcohol or drug use.

Acculturative stress was positively associated with alcohol use severity, drug use severity, and any drug use, but not with heavy episodic drinking. These results are generally consistent with the notion that culturally-based stressors increase alcohol or drug use (e.g., Ehlers et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2013; Jankowski et al., 2020; Sanchez et al., 2015). Maladaptive coping (avoidance), i.e., use of mood altering substances may be a common response to acculturative stress. Future studies with tailored behavioral interventions might conceptualize alcohol or drug use as an avoidant coping strategy, or teach proactive coping to reduce or mitigate the effects of culturally-based stressors, such as a module to teach coping skills for racism or discrimination and challenging stereotypes embedded into alcohol or drug use prevention for Latinx adolescents (e.g., Burrow-Sanchez et al., 2011). Although acculturative stress has traditionally been studied as a single measure, future studies could examine differential sources of culturally-based stressors.

Americanism had positive associations with alcohol and drug use. This finding is consistent with past studies, including a meta-analysis by Lui & Zamboanga (2018) that assessed acculturation using language-based measures of cultural practices to show that Latinx immigrants who are exposed to American activities have greater alcohol or drug use. This relationship was evident beyond the effects of acculturative stress, implying the link is not solely due to contact with American culture leading to greater discrimination. Future research could test what features of exposure to and adoption of American cultural practices confer risk, e.g., greater Americanism may be associated with permissive attitudes toward alcohol and drugs (e.g., Borsari & Carey, 2003; Ward & Guo, 2020). Alternatively, immigrants may feel more conflicted emotionally when they adopt American values. Future research should test whether social norms about alcohol or drug use mediate the relationship between Americanism and alcohol or drug use, and how immigrants perceive and make decisions about adoption of receiving culture practices using qualitative research. Understanding these links may inform adapted interventions based on normative feedback interventions for college students (e.g., Saxton et al., 2021).

Familism was inversely related to drug use, but not alcohol use. Findings partially supported the multidimensional acculturation approach (e.g., Schwartz et al., 2010) as both cultural practices and cultural values had independent links to drug use. It is possible that participants holding strong values related to family were able to counter the disrupting effects of acculturative stress on family functioning, which protected against drug use. Familism may also provide protective benefits apart from mitigating stress by encouraging views against drug use. The lack of a relationship with alcohol could suggest alcohol has less negative connotations than drugs, or that the familism measure, assessing many values of traditional family structures, may have missed broader but important social values. Future research could investigate familism measures for immigrants who may be apart from their blood kin.

Contrary to hypotheses, we found no relationships between Hispanicism or cultural identity and alcohol or drug use. These null findings did not support the theory that these protect Latinx immigrants against alcohol or drug use by slowing the adoption of permissive attitudes (e.g., Caetano, 1987). This may be due to low variation and/or ceiling effects with means close to the upper limit of both scales as expected in recent Latinx immigrants. Alternatively, the lack of relationships between Hispanicism and positive cultural identity and alcohol and drug use may have been influenced by context, i.e., a recent immigrant receiving environment where enculturation and positive cultural identity may not be as protective as established communities. Larger samples with greater cultural identity or Hispanicism ranges might study these potential contextual relationships in a variety of communities.

Additional limitations should be noted. Self-report measures were susceptible to participant error or bias; calendar-based or biological measures might reduce bias. he drug use measure was limited from lacking frequency or quantity items and binary responses, and low drug use in the sample may have reduced our ability to find significant associations. We assessed four acculturation variables and acculturative stress, but other constructs, e.g., machismo, might be related to alcohol or drug use. Cross-sectional data prevented making causal inferences. Recruiting in one region without probability-sampling limited generalizability, and the numbers of Latinx heritage or nationality groups were too small to examine subgroup variation. Probability sampling of U.S. Latinx immigrants may be difficult, but future studies should replicate findings with diverse samples from multiple areas.

Despite limitations, results linked culturally important variables to alcohol and drug use in U.S. Latinx adult immigrants. Studies are needed with diverse Latinx samples (e.g., greater variation in age and nativity) and longitudinal designs with many possible mediators and moderators. However, both acculturative stress and acculturation, or adoption of American cultural practices, were related to alcohol and drug use. These cultural variables are likely useful for intervention development, specifically coping with or mitigating stressors like discrimination and racism, countering risky beliefs linked to U.S. culture or to reduce emotional conflicts about adopting American practices or values, may increase intervention effectiveness.

Acknowledgements:

This research was funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health R01MD012249 (Rosa M. Gonzalez-Guarda, Principal Investigator). Partial financial support for Qing Li is from University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus School of Medicine 2021 Slay Community Scholars. The authors are solely responsible for this article’s content and do not necessarily represent the official views official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Brian E. McCabe, Department of Special Education, Rehabilitation, and Counseling, Auburn University. Auburn, AL..

Harley Stenzel, Department of Special Education, Rehabilitation, and Counseling, Auburn University. Auburn, AL..

Qing Li, Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA..

Richard C. Cervantes, Behavioral Assessment Inc., Los Angeles, CA..

Rosa M. Gonzalez-Guarda, School of Nursing, Duke University, Durham, NC..

References

- Arciniega LT, Arroyo JA, Miller WR, & Tonigan JS (1996). Alcohol, drug use and consequences among Hispanics seeking treatment for alcohol-related problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 57(6), 613–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, & Robaina K. (2017). USAUDIT, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, adapted for use in the United States: A guide for primary care practitioners. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. http://www.ct.gov/dmhas/lib/dmhas/publications/USAUDITGuide_2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Berger Cardoso J Goldbach JT, Cervantes RC & Swank P. (2016). Stress and Multiple Substance Use Behaviors Among Hispanic Adolescents. Prevention Science, 17(2), 208–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, & Kim U. (1988). Acculturation and mental health. Health and Cross-Cultural Psychology: Towards Application, 207–236.

- Berry JW (2003). Conceptual approaches to acculturation. Acculturation: Advances in Theory, Measurement, and applied research, 17–37.

- Berry JW (2006). Acculturative stress. In Wong PTP & Wong LCJ (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping (pp. 287–298). Dallas, TX: Spring. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, & Carey KB (2003). Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64(3), 331–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrow-Sanchez JJ, Martinez CR Jr, Hops H, & Wrona M. (2011). Cultural accommodation of substance abuse treatment for Latino adolescents. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 10, 202–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R. (1987). Acculturation, drinking and social settings among U.S. Hispanics. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 19, 215–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, & Galvan FH (2001) Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among Latinos in the United States. In: Aguirre-Molina M, Molina CW, Zambrana RE, editors. Health Issues in the Latino Community. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Cano ÁM, Sánchez M, De La Rosa M, Rojas P., et al. (2020). Alcohol use severity among Hispanic emerging adults: Examining the roles of bicultural self-efficacy and acculturation. Addictive Behaviors 108, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano ÁM, Vaughan EL, de Dios MA, Castro Y, Roncancio AM, Ojeda L. (2015) Alcohol use severity among Hispanic emerging adults in higher education: Understanding the effect of cultural congruity. Substance Use & Misuse, 50(11), 1412–1420,. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, & Weintraub JK (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 267–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Planning and implementing screening and brief intervention for risky alcohol use: A step-by-step guide for primary care practices. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes RC, Fisher DG, Córdova D Jr., & Napper LE (2012). The Hispanic stress inventory—adolescent version: a culturally informed psychosocial assessment.Psychological Assessment, 24,187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes RC, Fisher DG, Padilla AM, & Napper LE (2016). The Hispanic Stress Inventory Version 2: Improving the assessment of acculturation stress. Psychological Assessment, 28(5), 509–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Córdova D, & Cervantes RC (2010). Intergroup and within-group perceived discrimination among US-born and foreign-born Latino youth. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 32,259–274 [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Iturbide MI, Torres Stone RA, McGinley M, Rafaelli M, & Carlo G. (2007). Acculturative stress, social support, and coping: Relations to psycho-logical adjustment among Mexican American college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13, 347–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Rosa MR, Holleran LK, Rugh D, & MacMaster SA (2005). Substance abuse among US Latinos: A review of the literature. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Gilder DA, Criado JR, & Caetano R. (2009). Acculturation stress, anxiety disorders, and alcohol dependence in a select population of young adult Mexican Americans. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 3, 227–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis SR, Ríos-Vargas M, & Albert NG (2011). The Hispanic population: 2010 (census brief C1020BR-04). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Flores YN, Yee HF Jr, Leng M, Escarce JJ, Bastani R, Salmerón J, & Morales LS (2008). Risk factors for chronic liver disease in Blacks, Mexican Americans, and Whites in the United States: results from NHANES IV, 1999–2004. The American journal of gastroenterology, 103, 2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach JT, Berger Cardoso J, Cervantes RC, & Duan L. (2016). The Relation Between Stress and Alcohol Use Among Hispanic Adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Graham JW (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 549–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Pahl K, & Way N. (2006). Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology,42,218–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero EG (2013). Enhancing access and duration in substance abuse treatment: The role of Medicaid payment acceptance and cultural competence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 32, 555–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski PJ, Meca A, Lui P, & Zamboanga BL (2020). Religiousness and acculturation as moderators of the association linking acculturative stress to levels of hazardous alcohol use in college students. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 12, 88–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, Colby SN, Rohsenow DJ, López SR, Hernández L, & Caetano R. (2013). Acculturation stress and drinking problems among urban heavy drinking Latinos in the northeast. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 12:4, 308–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui PP & Zamboanga BL (2018). A critical review and meta-analysis of the associations between acculturation and alcohol use among young Hispanic Americans. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 42:10, 1841–1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, & Gamba RJ (1996). A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: The Bidimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (BAS). Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 18, 297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Aleman MM, & Sutton MY (2014) Hispanics/Latinos and the HIV continuum of care in the Southern USA: a qualitative review of the literature, 2002–2013, AIDS Care, 26, 1592–1604, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2002). How to use a Monte Carlo study to decide on sample size and determine power. Structural equation modeling, 9, 599–620. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2017). Mplus User’s Guide. Eighth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Noe-Bustamante L. (2019). Key facts about U.S. Hispanics and their diverse heritage. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/09/16/key-facts-about-u-s-hispanics/

- Phinney JS (1996). When we talk about U.S. ethnic groups, what do we mean? American Psychologist, 51, 918–927. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, & Ong AD (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of counseling Psychology, 54, 271. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, & Rumbaut RG (2014). Immigrant America: a portrait. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, & Roberts RE (2003). Stress within a bicultural context for adolescents of Mexican descent. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 9,171–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marín G, Otero-Sabogal R, Marín BV, & Perez-Stable EJ (1987). Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t? Hispanic journal of behavioral sciences, 9, 397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, & Schwartz SJ (2019). The Study and Prevention of Alcohol and Other Drug Misuse Among Migrants: Toward a Transnational Theory of Cultural Stress. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(2), 346–369. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez M, Dillon FR, Concha M, & De La Rosa M. (2015). The Impact of Religious Coping on the Acculturative Stress and Alcohol Use of Recent Latino Immigrants. J Relig Health, 54(6), 1986–2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton J, Rodda SN, Booth N, Merkouris SS, & Dowling NA (2021). The efficacy of Personalized Normative Feedback interventions across addictions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one, 16(4), e0248262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Unger JB, Szapocznik J, (2010). Rethinking the concept of acculturation implications for theory and research. American Psychologist, 65:4, 237–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Weisskirch RS, Zamboanga BL, Castillo LG,Ham LS, Huynh QL,…Cano MA (2011). Dimensionsof acculturation: Associations with health risk behaviors amongcollege students from immigrant families. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 27–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Tomaso CC, Kondo KK, et al. (2014). Association of acculturation with drinking games among Hispanic college students. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 40:5, 359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore B. (2002). Taking culture seriously. Human Development, 45, 226–228. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA (1982). The drug abuse screening test. Addictive behaviors, 7, 363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA (2020). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2019 (NSDUH-2019-DS0001). Retrieved from https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/

- Triandis HC (1995). Individualism and collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau (2021). Quick Facts. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

- Valdez AL, Flores M, Ruiz J, Oren E, Carvajal S, & Garcia DO (2018) Gender and Cultural Adaptations for Diversity: A Systematic Review of Alcohol and Substance Abuse Interventions for Latino Males, Substance Use & Misuse, 53, 1608–1623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaeth PA, Caetano R, & Rodriguez LA (2012). The Hispanic Americans Baseline Alcohol Survey (HABLAS): the association between acculturation, birthplace and alcohol consumption across Hispanic national groups. Addictive Behaviors, 37(9), 1029–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward RM, & Guo Y. (2020). Examining the relationship between social norms, alcohol-induced blackouts, and intentions to blackout among college students. Alcohol, 86, 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon E, Cabirou L, Galvin S, Hill L, Daskaova P, Bhang C, Ahmad Mustaffa A, Dao A, Thomas K, Baltazar B. (2020) A meta analysis of acculturation and enculturation: Bilinear, multidimensional, and context-dependent processes. The Counseling Psychologist 48:3, 342–376. [Google Scholar]