Abstract

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection identified as a definitive human carcinogen is increasingly being recognized for its role in carcinogenesis of human cancers. Up to 38%–80% of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) in oropharyngeal location (OPSCC) and nearly all cervical cancers contain the HPV genome which is implicated in causing cancer through its oncoproteins E6 and E7. Given by the biologically distinct HPV-related OPSCC and a more favorable prognosis compared to HPV-negative tumors, clinical trials on de-escalation treatment strategies for these patients have been studied. It is therefore raised the questions for the patient stratification if treatment de-escalation is feasible. Moreover, understanding the crosstalk of HPV-mediated malignancy and immunity with clinical insights from the proportional response rate to immune checkpoint blockade treatments in patients with HNSCC is of importance to substantially improve the treatment efficacy. This review discusses the biology of HPV-related HNSCC as well as successful clinically findings with promising candidates in the pipeline for future directions. With the advent of various sequencing technologies, further biomolecules associated with HPV-related HNSCC progression are currently being identified to be used as potential biomarkers or targets for clinical decisions throughout the continuum of cancer care.

Keywords: Human papillomavirus (HPV) integration; Molecular diagnostics, Oropharyngeal cancer, De-Escalation treatment, Immunotherapy

Introduction

High-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) infection leads to the development of human cancers in a variety of anatomical squamous tissue sites, including the head and neck regions. The incidence of HPV-related head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), especially oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC), has increased in the United States and Europe (Chaturvedi et al. 2013; Tinhofer et al. 2015; Wittekindt et al. 2019; Zamani et al. 2020). In some regions, HPV-related OPSCC accounts for 38%–80% of OPSCCs and 30% of HNSCCs (Boscolo-Rizzo et al. 2013; Chaturvedi et al. 2013; de Martel et al. 2020; Leemans et al. 2018) (Table 1). In particular, patients with HPV-related OPSCC have a better prognosis than those with HPV-negative OPSCC (Leemans et al. 2018). The proportion of comparatively younger patients is high among patients with HPV-related OPSCC (Leemans et al. 2018). Moreover, HPV-related OPSCCs are more sensitive to chemoradiotherapy and immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) treatments than HPV-unrelated tumors (Leemans et al. 2018). With the accumulated understanding of the new entity of HPV-related OPSCC, a new staging system in the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) has been established toward a deintensified treatment protocol to reduce long-term associated morbidity for patients with HPV-related OPSCC. However, recent phase III clinical trials (RTOG 1016 and De-ESCALaTE) have shown that a number of patients with HPV-related OPSCC who received deintensified treatment had an inferior outcome compared to those who received standard care (Gillison et al. 2019b; Mehanna et al. 2019). Moreover, patients with HPV-related HNSCC at multiple sites, defined as one HPV-positive primary OPSCC and a second primary of any head and neck site, demonstrated distinct characteristics (i.e., a lower T and N stage) compared to patients with one primary tumor (Joseph et al. 2013; Strober et al. 2020). These observations lead to a further discussion on the feasibility of the current design of the de-escalation treatment protocol in clinical trials and highlight the necessity to refine the stratification strategy for patients with HPV-related HNSCC, in particular for OPSCC (Ventz et al. 2019).

Table 1.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) status in relation to oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC).

| Time interval of collected data | Samples | Men/women | Median Age | HPV genotypes | Detection method | HPV + rate | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | ||||||||

| 2012–2018 | 49 | 29/20 | 53 | 16, 18, 52 | HPV 16/18 RNA ISH | 28.6% | Yang et al. (2020) | |

| 2007–2019 | 152 | 127/25 | NA | 11, 16, 18, 33, 53, 58 | HPV genotyping | 65.1% | Xu et al. (2020c) | |

| 2014–2019 | 257 | 221/36 | 60 | NA | HPV Genotyping | 18.3% | Xu et al. (2020b) | |

| 1999–2013 | 300 | 273/27 | 54 | 16, 33, 35, 56, 58, 68 | HPV Genotyping and/or p16 IHC | 25.0% | Chen et al. (2020) | |

| USA | ||||||||

| 2010–2014 | 1168 | 926/242 | 61 | NA | HPV 16/18 DNA ISH and/or p16 IHC | 52.8% | White et al. (2020) | |

| 2010–2016 | 45,940 | 38,0381/7902 | 60 | 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 36, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 26, 53, 66, 67, 69, 70, 73, 82, 85 | HPV 16/18 DNA ISH and/or p16 IHC | 67.5% | Rotsides et al. (2020) | |

| 1996–2013 | 115 | 101/14 | 56 | NA | p16 IHC | 90.4% | Altenhofen et al. (2020) | |

| NA | 381 | 332/49 | NA | NA | HPV RNA | 79.8% | Liu et al. (2020) | |

| 2002–2013 | 611 | 517/94 | NA | NA | HPV ISH and p16 IHC | 89.0% | Elhalawani et al. (2020) | |

| 2007–2018 | 88 | 69/19 | 73 | 16, 18, 33, 35 | PCR amplification of HPV gene loci or p16 IHC | 70.5% | Dickstein et al. (2020) | |

| UK | ||||||||

| 2010–2016 | 273 | 207/66 | 59 | NA | p16 IHC | 73.3% | De Felice et al. (2020) | |

| Canada | ||||||||

| 2005–2017 | 2039 | 1668/371 | NA | NA | p16-IHC | 48.7% | Huang et al. (2020) | |

| 1997–2015 | 372 | 0/372a | NA | NA | p16-IHC | 56.8% | Gazzaz et al. (2019) | |

| 1998–2004 | 525 | 381/144 | NA | NA | p16-IHC, HPV DNA ISH | 73.5% | Hall et al. (2019) | |

| Australia | ||||||||

| 2016–2017 | 650 | 284/366 | 52 | 16 | HPV16 DNA | 1.8% | Tang et al. (2020) | |

| 2018–2019 | 910 | 315/595 | 37 | 13, 16, 18, 32 | HPV DNA | 35.3% | Jamieson et al. (2020) | |

| Australia and New Zealand | ||||||||

| NA | 189 | NA | NA | 16, 18 | P16 IHC and HPVRNA ISH | 88.1% | Young et al. (2020a, 2020b) | |

| Netherlands | ||||||||

| 2009–2016 | 216 | 143/73 | NA | NA | p16 IHC and HPV DNA | 31.9% | Chargi et al. (2020) | |

| 1995–2015 | 168 | 135/33 | NA | NA | p16 IHC and/or HPV DNA | 50.0% | Molony et al. (2020) | |

| Brazil | ||||||||

| 1999–2010 | 346 | 308/38 | 55 | 16 | HPV16 and p16 IHC | 6.1% | Buexm et al. (2020) | |

| 2017–2019 | 91 | 78/13 | 61 | NA | p16 IHC | 20.9% | Girardi et al. (2020) | |

| 1984–2014 | 215 | 190/25 | 56 | 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73, 82 | HPV DNA detection and/or p16 IHC | 59.1% | De Cicco et al. (2020) | |

| Germany | ||||||||

| 2000–2017 | 102 | 82/20 | 57.5 | 16, 18, 33, 59 | HPV genotyping and p16 IHC | 40.2% | Weiss et al. (2020) | |

| 2000–2011 | 141 | 103/38 | NA | 16 | HPV DNA and p16 IHC | 34.0% | Huebbers et al. (2019) | |

| 2000–2014 | 323 | 245/78 | 58.87 | NA | HPV DNA and p16 IHC | 19.8% | Grønhøj et al. (2019a) | |

| 2000–2017 | 730 | NA | NA | NA | HPV DNA and p16 IHC | 27.1% | Wittekindt et al. (2019) | |

| 2007–2016 | 92 | 77/15 | NA | 16, 18 | HPV Genotyping and p16 IHC | 71.4% | Freitag et al. (2020) | |

| Denmark | ||||||||

| 2000–2017 | 2169 | 1564/605 | 58 | 16, 18, 33, 25, 59, 26, 31, 45, 56, 11, 58 | HPV DNA detection and p16 IHC | 55.0% | Zamani et al. (2020) | |

| 2000–2014 | 417 | 0/417 | 61.2 | NA | HPV DNA and p16 IHC | 48.7% | Christensen et al. (2019) | |

| 2000–2014 | 993 | 720/273 | 59.50 | NA | HPV DNA and p16 IHC | 56.9% | Grønhøj et al. (2019a) | |

| 2000–2014 | 1499 | NA | NA | NA | HPV DNA and p16 IHC | 55.0% | Grønhøj et al. (2019b) | |

| 2000–2014 | 1243 | 903/340 | 60.2 | NA | HPV DNA and p16 IHC | 63.4% | Rasmussen et al. (2019) | |

| Korea | ||||||||

| NA | 60 | 50/10 | 59 | NA | HPV DNA detection and p16 IHC | 80.0% | Suh et al. (2020) | |

| 2004–2013 | 113 | 101/12 | NA | NA | HPV Genotyping and p16 IHC | 69.9% | Kwon et al. (2020) | |

| Austria | ||||||||

| 2014–2019 | 62 | 48/14 | NA | 16, 18, 33, 40, 62, 68 | HPV Genotyping or p16 IHC | 100% | Kofler et al. (2020) | |

| South Glasgow | ||||||||

| 2010–2017 | 272 | NA | NA | 16. 18. 33. 39. 58 | HPV Genotyping | 44.0% | Zubair et al. (2020) | |

| Finland | ||||||||

| 2000–2016 | 157 | 110/47 | 59.5 | NA | p16 IHC | 9.8% | Sievert et al. (2020) | |

| Spain | ||||||||

| 2017–2019 | 54 | 43/11 | 62 | NA | p16 IHC and HPV DNA | 18.5% | Viros Porcuna et al. (2020) | |

| Cameroon | ||||||||

| 2014–2015 | 101 | 31/70 | 42 | 32, 68, 82 | p16 IHC and HPV RNA ISH | 5.0% | Rettig et al. (2019) | |

| Sweden | ||||||||

| 2000–2018 | 195 | 123/72 | 67 | NA | HPV DNA and p16 IHC | 15.9% | Hammarstedt et al. (2020) | |

| Croatia | ||||||||

| 2002–2015 | 99 | 82/17 | 60 | NA | HPV DNA and HPV E6 mRNA | 40.4% | Božinović et al. (2019) | |

| Thailand | ||||||||

| 2010–2016 | 110 | 95/15 | 59 | 16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 70, 73, 82 | p16 IHC and HPV DNA ISH | 14.5% | Nopmaneepaisarn et al. (2019) | |

| Italy | ||||||||

| 2010–2017 | 59 | 43/16 | 66 | NA | HPV DNA | 41.2% | Ravanelli et al. (2020) |

Studies included in this table meet the following criteria: OPSCC patients; HPV DNA or RNA positive or p16 positive; studies published between January 2019 and October 2020

aThis study included women with OPSCC only

IHC: immunohistochemical staining; ISH: in situ hybridization

HPV-driven oncogenic processes are characterized by HPV oncoproteins E6 and E7, which induce p53 and retinoblastoma (Rb) degradation, consequently leading to a deregulation of the cell cycle and an inhibition of apoptosis (Wittekindt et al. 2018). A plethora of data have been recently accumulated for different incidences of gene mutations and chromosomal aberrations between HPV-related and HPV-unrelated HNSCCs (Pickering et al. 2013; The Cancer Genome Atlas Network 2015). For example, TP53 mutations are found in approximately 60%–70% of HNSCCs, and different gain-of-function p53 mutants are related to oncogenesis, especially in HPV-unrelated HNSCC (Zhou et al. 2016). We recently developed a prognostic scoring system including five covariates (age, pT, pN, perineural invasion, and EAp53 score) for HPV-independent HNSCC patients via The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)-based tumor genomic analysis (Qian et al. 2019). In addition to TP53 mutation, the exclusivity of CDKN2A and TERT driver mutations has also been identified in HPV-related HNSCC (Zapatka et al. 2020). Recurrent deletions and truncating mutations of TNF receptor-associated factor 3 (TRAF3), which is involved in innate and acquired antiviral immune responses, were found to be associated with HPV-related HNSCC (The Cancer Genome Atlas Network 2015). Furthermore, recent omics studies on HPV virus-host protein interactions have identified several potential and multiple oncogenesis pathways that can be promoted by HPV interactions, similar to recurrent mutations in cancer (Eckhardt et al. 2018). Moreover, an increase in mutations related to a higher expression of apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing catalytic polypeptide (APOBEC) was found in HPV-related HNSCC compared to HPV-negative tumors (Zapatka et al. 2020). Notably, it is hypothesized that a pathogenetic process is needed for the development of HPV-related cancers (Cui et al. 2019). A recent study demonstrated that genotypes of KRAS mutations and a loss of PTEN with both HPV E6/E7 dependence and independence lead to precipitous cervical cancer development, while HPV E6/E7 alone leads to only carcinoma in situ in a mouse model (Böttinger et al. 2020). A comprehensive understanding of how these mutations are involved in the carcinogenesis of HPV-related cancers remains to be established.

Another important consideration is antiviral defenses and host–pathogen interactions that help us understand HPV-induced immune evasions in HPV-related cancers (Zhou et al. 2019). E6 and/or E7 seropositivity has been found in the majority of HPV DNA-positive HNSCC patients and is associated with longer recurrence-free survival (Smith et al. 2010; Lang Kuhs et al. 2017). A genome-wide association study on the association between OPSCC and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) loci demonstrated that the class II haplotype DRB1*1301-DQA1*0103-DQB1*0603 was associated with a strongly reduced risk of HPV-related OPSCC compared to HPV-negative tumors (Lesseur et al. 2016).

However, the down-regulation of antigen-processing machinery components against HPV oncoproteins (i.e., HPV16 E7 or E5) has been reported in cervical cancer and HNSCC (Albers et al. 2005). HPV16 E7 can also suppress stimulator interferon gene (STING) complex-induced type I interferon (IFN-I) activation, by which effector T cell expansion is limited (Luo et al. 2020). Moreover, higher membranous PD-L1 expression at the tonsils and high levels of PD-1 expression within the majority of CD8 + tumor-infiltrating leukocytes (TILs) indicate adaptive immune resistance in HPV-related HNSCC (Lyford-Pike et al. 2013). In addition, the immune features within the tumor microenvironment (TME) of HPV-related HNSCC can be differentiated from HPV-negative tumors (Cillo et al. 2020). HPV-related OPSCC patients with HPV16-specific type-I T cells and type-I-oriented TME have a better prognosis than patients lacking HPV immunity (Welters et al. 2018). Enriched germinal center B cells in TILs of HPV-related HNSCC indicate their role through germinal center reactions during virus-driven progression (Cillo et al. 2020). B cells in nongerminal center states are more prominent in HPV-negative tumors (Cillo et al. 2020). Recently, HPV-specific B cell responses, including antigen-specific activated and germinal center B cells and plasma cells, were identified in the TME of samples from HPV-related HNSCC (Wieland et al. 2020). These findings demonstrate more heterogeneous immunity in HPV-driven tumors, which has the potential to refine the risk group.

A fundamental understanding of the heterogeneity, plasticity and cellular mechanisms of HPV-related HNSCC biology offers an opportunity to uncover therapeutic windows and to separate the small subset of patients with HPV-related cancer at high risk, from whom a de-escalation approach would be appropriate. Here, we review the current knowledge regarding HPV-related HNSCC and the challenges of targeting these cancers. We also discuss potential applications for biomarker-based stratification strategies, which are due to spatial and temporal varieties of conditions, including the broader TME and the underlying pathways of antitumor response and tumor resistance.

The Epidemiology of HPV Oral Infections and HNSCC

Worldwide, more than 830,000 cases of HNSCC are diagnosed each year, with approximately 430,000 deaths (Bray et al. 2018). The incidence of HPV-related HNSCC is increasing, i.e., by 2.5% per year for OPSCC in the United States (Mifsud et al. 2017; Mourad et al. 2017). In China, the estimated age-standardized incidence rate of HNSCC was 2.7 per 100,000 and 2.22/100,000 person-years by the standard population of China in 2000 (ASRIC and ASRMC) for OPSCC (Liu et al. 2018). As seen in recent studies in China, the rates of HR-HPV infection in HNSCC are 7.5% in a case control study and 26.4% in southern Chinese population (Chor et al. 2016; Ni et al. 2019). HPV-related HNSCCs have been found in the oral cavity, oropharynx, pharynx, larynx and salivary glands, with the highest prevalence for OPSCCs (Qian et al. 2016; Wiegand et al. 2018). Table 1 illustrates recent reports of HPV-related OPSCCs in different regions. Squamous cell carcinoma of unknown primary in the head and neck (SCCUPHN) present with neck lymph node metastasis with no evidence of a primary tumor accounts for 4%–5% of HNSCCs (Ren et al. 2019; Schroeder et al. 2020). The prevalence of HPV positivity in SCCUPHN was 49% as reviewed by a recent meta-analysis (Ren et al. 2019). In a prospective study, SCCUPHN, defined as the metastasis of SCC to a neck node, was likely to be HPV-driven OPSCC because of the similarities in risk factor profile and survival with HPV-driven OPSCC (Schroeder et al. 2020). Additionally, the rate of a secondary primary tumor in HNSCC with unknown HPV status is reported to be ~ 14%, and the highest is 36% (Chuang et al. 2008). Patients who develop multiple primary tumors of HPV-related HNSCC (one primary HPV-related OPSCC with a second primary tumor of any head and neck site) were recently reported at a rate of 0.95%–2.64% depending on different datasets (Strober et al. 2020). Notably, those patients tend to be younger and have no neck adenopathy compared to patients with one primary HPV-related tumor (Strober et al. 2020).

The prevalence of HPV-related OPSCC varies in different age groups. In earlier reports, patients with HPV-related OPSCC tended to be demographically younger. However, an increase in the proportion of patients of older age over time leads to the median age being older (Smith et al. 2004; Fakhry et al. 2020). Among recent studies from different regions, the median age varies from 37 to 73 years with the different time intervals of collected data (Table 1).

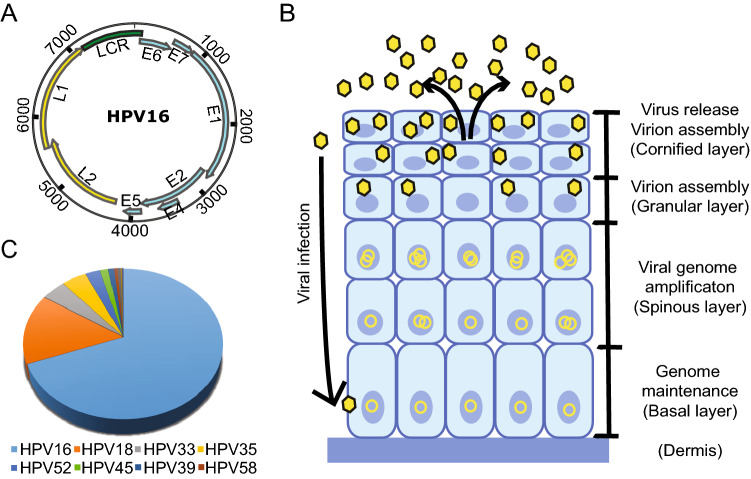

To date, HR-HPV genotypes 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59 are categorized as Group 1 carcinogens, 68 as Group 2A and 26, 30, 34, 53, 66, 67, 69, 70, 73, 82, 85, 97 as Group 2B carcinogen (Bouvard et al. 2009). HPV infections with HR-subtypes (HPV 16, 18, 26, 30, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 67, 68 and 69) have been identified in HNSCC (Fig. 1, Table 1) (Castellsagué et al. 2016; Tumban 2019). A recent analysis of 3,680 samples from 29 countries shows that HPV 16, 33, 35 and 18 are responsible for the majority of HPV-related OPSCCs (Castellsagué et al. 2016). Overall, HPV 16 is predominant and accounts for 90%–97% of HPV-related OPSCCs (Gillison et al. 2015). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected individuals have a risk of developing HPV-HIV coinfection, and the incidence of age-standardized HPV-related HNSCC increased from 6.8 to 11.4 per 100,000 person-years from 1996 to 2009 in North America (Beachler et al. 2014; Dsouza et al. 2014).

Fig. 1.

A The HPV genomic structure (use HPV 16 as an example). The ORFs encoding the early (blue) and late (yellow) genes are marked. B The life cycle of HPV starts with viral infection at the basal cells through trauma and the viral genomes are maintained at low copy number level in undifferentiated cell. Upon cell differentiation, the viral genomes become amplified and virion assembly ensues, resulting in the release of viruses in the cornified layer. C The contribution of different high-risk HPV genotypes to head and neck squamous carcinoma (Tumban 2019).

HPV Genome and Expression

The genetic information of HPVs is carried by their circular, double-stranded DNA genome, which has a size of approximately 8,000 base pairs (Zheng and Baker 2006). According to the genome data compiled in the Papillomavirus Episteme database (https://pave.niaid.nih.gov/), there are more than 225 distinct genotypes of HPVs, which are classified according to the DNA sequence of the L1 gene. To be recognized as a new genotype, the L1 region sequence has to be more than 10% different from its closest member. Despite the sequence variation, the HPV genome structure is similar for all genotypes and is organized into three regions (Fig. 1). The early gene region contains several overlapping open reading frames (ORFs) denoted E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, E7 and E8 (E5 and E8 not present in all genotypes) that code for nonstructural and regulatory proteins involved in various processes of the virus life cycle, such as viral replication and transactivation of gene expression. Currently, 12–15 genotypes of HPVs are considered oncogenic for certain types of cancers, with the early proteins E6 and E7 playing key roles in oncogenesis and thus are two multifunctional viral oncoproteins (Zheng and Wang 2011; Roman and Munger 2013; Vande Pol and Klingelhutz 2013; Wang et al. 2014). The late gene region encodes structural proteins L1 and L2, the major and minor capsid proteins. In addition, a noncoding region (NCR) or upstream regulation region (URR) between the late and early regions contains a viral replication Ori (Wang et al. 2017) and binding sites for various viral and host transcription and regulation factors, such as viral E1 and E2, the functions of which are essential in viral DNA replication and amplification.

The transcription of viral genes and viral genome replication are tightly regulated throughout the life cycle of papillomaviruses in a host cell differentiation manner. The virus infects basal layer cells through epithelial layer trauma. In undifferentiated basal cells, the expression of most viral early proteins from viral early promoter-derived RNA transcripts is maintained at low levels to avoid triggering immune responses. As cell differentiation occurs, viral DNA replication and activation of the viral late promoter lead to the expression of viral late genes and the production of infectious virus particles in the granular and cornified layers of the epithelium (Fig. 1B). Although epigenetic modifications, including chromatin remodeling and DNA methylation on both viral and host genomes, play important roles in the control of viral gene expression, with numerous studies being explored for their function at various stages of the viral life cycle, the posttranscriptional regulation, such as RNA splicing, polyadenylation, stability, export and translation, is essential for the expression of each viral protein. Our understanding of these regulations remains minimal. In high-risk HPV16 and HPV18, viral E6 and E7 are expressed as a single bicistronic E6/E7 RNA undergoing extensive RNA splicing (Tang et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2011; Ajiro et al. 2016). While viral E6 is expressed from the unspliced E6 RNA coding region, viral E7 protein can be expressed only from spliced E6*I RNA (Zheng et al. 2004; Tang et al. 2006; Ajiro et al. 2012; Brant et al. 2019). To date, we know very little how viral E1 and E2 are expressed in the context of the entire viral genome during high-risk HPV infection. Papillomaviral E4 is encoded from the viral early region, but it is a viral late protein translated from a viral late transcript derived from a late promoter residing in the E7 coding region (Wang et al. 2011; Xue et al. 2017). By alternative splicing, this late transcript also translates viral L2 and L1 for viral capsid formation (Zheng and Baker 2006). Viral L1 and L2 form the basis for HPV vaccines in preventing HPV infection and the development of HPV-induced cancers (Zhou et al. 1991; Kirnbauer et al. 1992; Schiller et al. 2012). Further elucidation of the molecular mechanisms that control viral DNA replication, transcription and posttranscriptional regulation may provide novel targets for combating HPV and treating HPV-associated cancers. For more detailed discussion on epigenetic regulation of HPV genome transcription, please refer to a recent review by Burley et al. (Burley et al. 2020).

HPV Integration and HNSCC

The integration of HR-HPV DNA into the host genome has been considered an important biological step in the development of carcinogenesis in invasive cervical cancer and HNSCC (Mesri et al. 2014; Zapatka et al. 2020). Initial studies demonstrated that transcriptionally active integrated and/or episomal viral DNA in HNSCC cell lines was independent of viral copy number and integration sites (Akagi et al. 2014; Olthof et al. 2015). HPV integration can lead to host genomic instability, such as deletions, inversions, and chromosomal translocations (Akagi et al. 2014). A number of viral integration sites in the host genome were found in intergenic regions as well as cancer-associated genes such as TP63, ETS2, RUNX1, FOXA1 and ERBB2 (Olthof et al. 2014, 2015; Walline et al. 2016; Koneva et al. 2018). Moreover, viral integration into cellular genes was commonly identified in recurrent HPV16-positive OPSCC patients, and these cellular genes are related to cancer-associated signaling pathways or mechanisms (Walline et al. 2016). Integrated viral DNA copies could be in tandem. Viral DNA integration through the disruption of the viral E2 region leads to increased transcription of viral E6 and E7. Tumors with HPV DNA integration differ from HPV integration-negative tumors by different patterns of DNA methylation and gene expression profiles (Parfenov et al. 2014). Recently, Zapatka et al. found that HPV 16 and HPV 18 integration events in cervical cancer and HNSCC were associated with local variations and genomic rearrangements based on the Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes Consortium (Zapatka et al. 2020).

HPV integration inducing genome instability is hypothesized to be a secondary genetic event in the carcinogenesis of HPV-associated HNSCC. HPV infection is associated with increased expression of the APOBEC genes APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B but exclusively with known driver genes such as TP53, CDKN2A and TERT (Kondo et al. 2017; Zapatka et al. 2020). These findings suggest a possible role of APOBECs in HPV-induced carcinogenesis, i.e., the activity of APOBECs as C-to-U RNA editing enzymes contributes to alterations in host genome expression, and APOBEC3A increases tumorigenesis in vivo (Burns et al. 2013; Wallace and Münger 2018; Law et al. 2020). In addition, as part of the immune defense system, APOBEC3A can sensitize cancer cells to cisplatin treatment by activating base excision repair and mediating the repair of cisplatin interstrand crosslinks (Conner et al. 2020). These results suggest a role of impaired antiviral defense in driving the carcinogenesis of HPV-related HNSCC. HPV16 insertions also lead to the amplification of the PIM1 serine/threonine kinase gene in HNSCC cell lines (Broutian et al. 2020). The inhibition of PIM family kinases successfully decreased cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo in an HNSCC model (Broutian et al. 2020).

Notably, viral integration can be found in both tumors that respond to treatment and recurrent tumors with more complex integration patterns in host genes (Walline et al. 2016). By analyzing viral-host fusion transcripts, Koneva et al. showed that the HPV-positive but HPV integration-negative subgroup had better survival than the HPV integration-positive subgroup and HPV-unrelated HNSCC (Koneva et al. 2018). Moreover, HPV-positive but HPV integration-negative tumors had enhanced tumor infiltrates of immune cells and upregulated immune-related genes. Consistently, another study indicated that HPV-related HNSCC can be subdivided into an immune cell enrichment phenotype and a phenotype with higher proliferation (Koneva et al. 2018). Thus, the enhanced immune profile in patients with HPV-positive but HPV integration-negative tumors may be attributed to better survival for these patients. However, potential mechanisms for HPV integration-induced oncogenesis of HNSCC remain elusive.

Genetic and Epigenetic Alterations

Recent landmark sequencing studies have demonstrated gene expression profiles and somatic mutations such as TP53, CDKN2A, PTEN, PIK3CA, EGFR, HRAS, FBXW7 and NOTCH1 in diverse anatomical sites of HNSCC (Agrawal et al. 2011; Stransky et al. 2011; Pickering et al. 2013; The Cancer Genome Atlas Network 2015). Importantly, diversity in the number of mutations and gene profiles was seen in patients with a history of tobacco use and between HPV-related and HPV-unrelated tumors. The mutation rate of HPV-related tumors was almost half that of HPV-unrelated tumors (Stransky et al. 2011). Thus, two etiologies may result in the alteration of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes that have tumorigenic effects involved in multistep biological processes.

HPV-related HNSCC harbors mutations in the oncogene PIK3CA encoding PI3K catalytic p110 subunit alpha, a loss of TRAF3 and the amplification of E2F1 (The Cancer Genome Atlas Network 2015). A recent comprehensive analysis on oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) identified secondary genetic alterations, including PIK3CA, ZNF750 and EP300 as candidate cancer driver genes (Gillison et al. 2019a). APOBEC cytosine deaminase editing was associated with genomic mutation burden in HPV-related OSCC (Gillison et al. 2019a). APOBEC-mediated cytosine deamination leading to PIK3CA mutations is involved in the tumorigenesis of HPV-driven tumors (Henderson et al. 2014; Gillison et al. 2019a). As we discussed above, virus-host interactions, as seen by the interaction between HPV integration with APOBEC and others, may shape genomic alterations and facilitate tumorigenesis.

Notably, PIK3CA mutations (2.6% to 19%) lead to the activation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR1 signaling pathway necessary for the viral life cycle (Lui et al. 2013; Surviladze et al. 2013). HPV oncoproteins E6 and E7 also increase PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling (Pim et al. 2005; Contreras-Paredes et al. 2009). Moreover, both HPV-related and HPV-unrelated HNSCCs harbor PIK3CA mutations, and higher expression of PIK3CA in primary tumors is associated with tumor recurrence and chemo- and radioresistance (García-Escudero et al. 2018; Marquard and Jücker 2020). Thus, inhibitors targeting the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway have been developed for cancer therapies (Marquard and Jücker 2020). However, the clinical response rates remain modest in these studies and warrant further investigation (Marquard and Jücker 2020). Studies in patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models demonstrate that EGFR, AKT1 and CSMD1 copy number aberrations are related to the effect of PI3-kinase inhibition regardless of the status of PIK3CA mutation (Ruicci et al. 2019a). The knockdown of the TAM family receptor tyrosine kinases TYRO3 and AXL and the inhibition of MAPK signaling can resensitize resistance induced by alpelisib, a PI3K inhibitor (Ruicci et al. 2020). Adaptive resistance to PI3K inhibition is also seen in mTORC2-mediated Akt reactivation following PI3K inhibition. The knockdown of RICTOR, a subunit of mTORC2, can sensitize HNSCC cells to PI3K inhibition in vitro (Ruicci et al. 2019b).

TRAF3 functions as a tumor suppressor negatively to regulate NF-κB pathway activation in HPV-related HNSCC (Zhang et al. 2018). TRAF3 is involved in the innate and acquired antiviral immune responses (The Cancer Genome Atlas Network 2015). The re-expression of TRAF3 can enhance TP53 and RB tumor suppressor proteins and decrease HPV E6 oncoprotein in HPV + HNSCC cell lines (Zhang et al. 2018). Thus, regulating TRAF3 and aberrantly activating the alternative NF-kB pathway warrant further investigation as therapeutic targets in cancer treatment.

Another interesting aspect of HPV-induced HNSCC oncogenesis is epigenetic alterations, including DNA methylation and histone modifications (Kostareli et al. 2013; Hatano et al. 2017; Papillon-Cavanagh et al. 2017; Guo et al. 2020; Mac and Moody 2020). For example, higher DNA methylation levels are more common in HPV-related OPSCC than in HPV-unrelated tumors and normal tissues (Ren et al. 2018). Furthermore, candidates for DNA differentially methylated regions (DMRs) can discriminate HPV-related OPSCC from normal controls with good receiver operating characteristic (ROC) performances (Ren et al. 2018). Moreover, these changes are involved in different stages of the HPV life cycle in HPV-related OPSCC and other HPV-related malignancies (Boscolo-Rizzo et al. 2017; Mac and Moody 2020). HPV oncoproteins E6 and E7 may confer histone methylation and acetylation on targeted genes (Boscolo-Rizzo et al. 2017; Gaździcka et al. 2020). Histone methylation, such as elevated trimethylation at lysine 27 of histone H3 (H3K27me3), in HPV-related HNSCC is associated with tumorigenesis (Lindsay et al. 2017). Targeting zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), a histone methyltransferase, can reduce H3K27me3 and has the potential to sensitize cells to chemotherapy (Lindsay et al. 2017). Evidence also suggests that histone acetylation and deacetylation may deregulate the transcription of various genes in malignancy development in HNSCC (reviewed in (Boscolo-Rizzo et al. 2017; Gaździcka et al. 2020). Recently, Liu et al. demonstrated that HR-HPV oncogenes induce the long noncoding RNA (IncRNA), Inc-FANCI-2, mediated by E7 and E6, which is independent of p53/E6AP and pRb/E2F in cervical carcinogenesis (Liu et al. 2021). The differential regulation of lncRNAs between HPV-related and HPV-unrelated HNSCCs has also been demonstrated (Nohata et al. 2016; Haque et al. 2018; Song et al. 2019; Kopczyńska et al. 2020). However, their role in the oncogenesis of HNSCC remains elusive. In conclusion, epigenetic alterations might be useful in identifying subgroups of tumors, predicting clinical outcomes and providing potential targets (Kostareli et al. 2013, 2016; Ren et al. 2018; Shen et al. 2020).

In particular, research on single-cell molecular profiling can provide spatial and temporal characteristics of HNSCC in regard to intratumor heterogeneity (Puram et al. 2017; Qi et al. 2019). Tumor genetic heterogeneity determined by mutant-allele tumor heterogeneity is associated with worse outcome of patients with HNSCC (Mroz et al. 2013). Furthermore, a single-cell transcriptomic analysis identified subtypes as atypical, mesenchymal, basal, and classic phenotypes of OSCC (Puram et al. 2017). Recently, Cillo et al. identified a differential spectrum of immune lineages (helper CD4+ T cells and B cells) between HPV– and HPV+ HNSCCs by single-cell transcriptional profiling (Cillo et al. 2020). Thus, with the advantage of single-cell technologies, a more profound understanding of genetic, epigenetic and transcriptional differences for both HPV-related and HPV-unrelated tumors would be possible (Qi et al. 2019).

Impact of HPV Infection on Immune Checkpoint Blockade

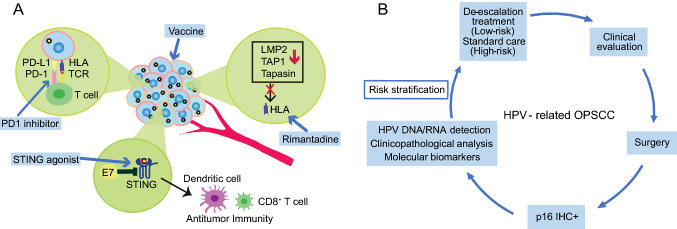

A wide exploration of the tumor-escape mechanisms of HNSCC leads to immunological approaches against tumors, including cancer vaccination and ICB treatment (Fig. 2A) (Albers et al. 2010; Xu et al. 2020a). The anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies nivolumab and pembrolizumab have been successfully established as first-line or second-line treatments for patients with recurrent/metastatic (R/M) HNSCC (Ferris et al. 2018; Cramer et al. 2019). The anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody atezolizumab has also shown its effect in patients with previously treated, advanced HNSCC in a phase I trial (Colevas et al. 2018). However, the overall response rates for both anti-PD1 and anti-PD-L1 treatments are only approximately 20% (Colevas et al. 2018; Qian et al. 2020). Virally mediated tumors such as HPV-related HNSCC demonstrate HPV-specific T cell immunity, and there is significant interest in developing a combination therapy to improve ICB treatment efficacy (Bhatt et al. 2020).

Fig. 2.

A Immune escape of HPV-related head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and potential approaches to improve immunotherapeutic effects against HPV-related tumor. HLA: human leukocyte antigen; TCR: T-cell receptor; PD-1: programmed cell death protein 1; PDL-1: programmed death-ligand 1; LMP2: low molecular weight protein 2; TAP1: antigen processing subunit 1; STING: stimulator of interferon genes. B The platform of risk stratification for HPV-related HNSCC. IHC: immunohistochemical staining.

High PD-1 expression was significantly associated with HPV-positive HNSCC in an analysis of a TCGA dataset (Lyu et al. 2019). PDL1 expression in HPV-related HNSCC ranges from ~49.2% to ~75% according to a report (Outh-Gauer et al. 2020). Increased PD1 expression on T cells is correlated with HR-HPV infection in the pathogenesis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasias (CINs) (Yang et al. 2013, 2017). Additionally, a higher HPV 16 viral load is correlated with high CD8 + and PD-1 + TIL expression in anal squamous cell cancer (ASCC) (Balermpas et al. 2017). PDL1 expression is significantly enhanced in relation to HPV positivity (i.e., HPV16 E7 oncoprotein) in CINs and cervical cancer compared to normal cervical epithelia (Yang et al. 2013; Mezache et al. 2015). Taken together, these findings suggest that PD1/PDL1 pathways may be activated by HR-HPV (i.e., E5, E6 and E7 oncoproteins) for HPV-related cancers. HPV E6/E7-induced master regulators (ENO1, PRDM1, OVOL1, and MNT) are positively correlated with PD-L1 and TGFB1 expressions in cervical cancer (Qin et al. 2017). The activation of the PD1/PDL1 pathway by HR-HPV can further inhibit Th1 cytokine IFN-c and IL-12 expressions and upregulate TH2-type cytokine and IL-10 expressions, consequently leading to immunosuppression and CIN progression (Wakabayashi et al. 2019; Zhou et al. 2019). Remarkably, the reactivity of nonviral tumor antigen-specific T cells, including mutated neoantigen or cancer germline antigen, together with HPV oncoprotein-reactive T cells was observed in HPV-associated metastatic cervical cancer patients with complete regression after tumor-infiltrating adoptive T cell therapy (Stevanović et al. 2017). Thus, it would be interesting to understand the crosstalk of HPV-mediated immunosuppression and immune checkpoint activities for further development of therapeutic strategies.

Efforts to define HPV-related HNSCC responses to ICB treatments were initially assessed based on recent clinical trials (Bauml et al. 2017; Ferris et al. 2018; Burtness et al. 2019). In CheckMate 141, a better median overall survival among patients receiving nivolumab treatment was found to be associated with HPV-positive tumors with PDL1-positive expression (Ferris et al. 2018). In KEYNOTE-012, the response rate to pembrolizumab treatment varied among HNSCC patients with PD-L1 positivity, with a higher response rate in HPV-positive tumors than in HPV-negative tumors (Seiwert et al. 2016). A recent meta-analysis demonstrated an improved response rate to ICB treatment among patients with HPV-positive HNSCC and a higher OS in patients with PDL1-positive HNSCC (Galvis et al. 2020). However, the treatment efficacy of atezolizumab in a phase I trial was found independent of HPV status and PD-L1 expression level (Colevas et al. 2018). Because of the limited size of each study, the findings should be interpreted with caution.

The development of combination therapy by employing different immune priming approaches has the potential to improve effective immune responses in HPV-related cancer patients who receive immunotherapy. For example, targeting HPV16/18 E6/E7 by a DNA vaccine with an IL12 adjuvant is able to generate durable HPV16/18 antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells and tumor immune responses in patients with p16 + locally advanced HNSCC (Aggarwal et al. 2019). One patient who developed metastatic disease received anti-PD1 nivolumab treatment and had a complete response (Aggarwal et al. 2019). This phase I/IIa clinical trial, in line with other vaccination strategies targeted to HR-HPV E6/E7 oncoproteins, demonstrates a complementary approach to improve immunotherapy outcomes (Aggarwal et al. 2019; Massarelli et al. 2019; Xu et al. 2020a). The NLRX1 signaling pathway was found to be associated with HPV16 E7-mediated IFN-I suppression and TIL infiltration in HNSCC (Luo et al. 2020). NLRX1 depletion leads to a turnover of HPV16 E7, potentiating STING/IFN-I suppression and consequently improving tumor control (Luo et al. 2020). Clinical trials (NCT02675439, NCT03172936, and NCT03010176) utilizing a combination of a STING agonist plus anti-CTLA-4 or anti-PD1 ICB treatments are underway (Luo et al. 2020). In addition, it has been demonstrated that HPV E5 mediates resistance to anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy, which is due to acquired loss of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) expression (Sharma et al. 2017; Miyauchi et al. 2020). Rimantadine, an FDA-approved antiviral drug to treat influenza that was recently found to induce an antitumor response, could increase MHC expression in HPV E5-expressing HNSCC (Miyauchi et al. 2020) (Fig. 2A). However, rimantadine in combination with radiation and PD-L1 checkpoint blockade treatment did not show a synergistic effect (Miyauchi et al. 2020). E2-derived CD8 T cell epitopes were found in patients with HPV-related HNSCC (Krishna et al. 2018). Wieland et al. demonstrated that the E2 protein is a major target of the humoral immune response in the TME of HPV-related HNSCC (Wieland et al. 2020). Thus, a combination of HPV E2, E6 and E7 as targets needs to be explored for future immunotherapeutic approaches. Alternatively, innovations in nanotechnology will likely synergize with immunotherapy to elicit a robust treatment response in HNSCC (Xu et al. 2020a). For example, the PC7A nanovaccine, an ultra-pH -sensitive nanoparticle synergistic with anti-PD1 antibodies, can improve antitumor immunity and survival in HPV-E6/E7 TC-1 tumors (Luo et al. 2017). Another example is an HR-HPV nanovaccine formulated with CL 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethyl-ammonium-propane (DOTAP), and long HR-HPV peptides can successfully boost Ag-specific CD8 T cell responses, induce complete tumor regression through a type I IFN response in HPV-E6/E7 TC-1 tumor models and synergize with an anti-PD1 checkpoint inhibitor (Gandhapudi et al. 2019). It should be noted that chemoradiotherapy decreases HPV-specific T cell responses and increases PD-1 expression on CD4 + T cells in patients with HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer (Parikh et al. 2014). Accordingly, a future analysis of patients with HPV-related HNSCC who have and have not responded to ICB treatment would provide additional insights for targeted immunotherapy as well as deintensified treatments.

Patient Stratification for the Deintensified Treatments

To formulate a diagnosis for HPV-related HNSCC, methods based on p16 immunohistochemical (IHC) staining, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)-based HR-HPV DNA or RNA testing, and HPV DNA or RNA in situ hybridization (ISH) have been established. In 2018, the College of American Pathologists (CAP) and American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) released guidelines that HR-HPV testing should be performed for OPSCC and cervical nodal metastases of unknown primary tumors (Fakhry et al. 2018; Lewis et al. 2018). Protein p16 IHC staining was recommended prior to other HPV testing with a cutoff of 70% nuclear and cytoplasmic positivity (Fig. 2B). For HPV-related tumors, the HR-HPV E7 oncoprotein increases expression of histone lysine demethylase 6B (KDM6B) and induces pRb degradation, thereby leading to H3K27-specific demethylation (derepression) of p16 promoter to enhance high level of p16 expression for proliferation of the cancer cells lacking the G1 checkpoint due to viral E7-induced loss of pRb (McLaughlin-Drubin et al. 2013; Pal and Kundu 2019). However, Albers et al. demonstrated that a subgroup of HNSCC with HPV-DNA+/p16− had poor survival compared to subgroups with HPV-DNA+/p16+ and HPV-DNA−/p16+, which suggests a biologically different subtype independent of HPV status (Albers et al. 2017). A recent survival analysis further revealed that 60.6% of p16+ HPV-DNA− OPSCCs did not resemble HPV16-driven but HPV-negative tumors (Wagner et al. 2020). Moreover, gene signatures such as TP53 mutations are indistinguishable between tumors with HPV DNA+RNA− and those with HPV DNA− (Wichmann et al. 2015). As indicated above, some patients who received deintensified treatments failed to show an improvement in clinical trials. Thus, pathology-based HPV testing beyond p16 IHC staining remains to be established. HPV RNA ISH, by which viral E6/E7 mRNA has been detected, showed a better survival prediction and a higher specificity than p16 IHC staining (Lewis 2020). Additionally, the sensitivity of HPV RNA ISH is higher than that of HPV DNA ISH (91% vs. 65%) (Kerr et al. 2015). The performance of HPV RNA ISH testing in stratifying OPSCC patients is worth further validation (Lewis 2020).

While current HPV-specific testing warrants further improvement, a better understanding of the biology of HPV-related HNSCC is necessary for us to identify new biomarkers correlated with disease outcomes and to predict treatment response signatures, especially for immunotherapy. For example, the latency effect of tobacco smoking exposure appears more profound in HPV-related HNSCC individuals who start smoking before sexual activity when compared to those who start after (Madathil et al. 2020). High levels of TILs that reflect the immune response can stratify HPV-related OPSCC patients into high-risk and low-risk groups for survival (Ward et al. 2014). Interestingly, a prognostic model was further developed, including three covariates (TIL levels, heavy smoking, and T-stage) in which low TIL levels, heavy smoking, and late T-stage were related to poor outcome for HPV-related OPSCC (Ward et al. 2014). HPV integration status based on RNA-seq data can differentiate survival between HPV integration-positive and HPV-negative HNSCC patients (Koneva et al. 2018). Most importantly, a set of immune-related gene signatures enriched in HPV-positive but HPV integration-negative tumors are distinguishable from those in HPV integration-positive tumors (Koneva et al. 2018). The lower E2F target gene expression predicted by reduced E7 levels is associated with disease recurrence through patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models for HPV-related HNSCC (Facompre et al. 2020). HPV + tumors have been related to an inflamed/mesenchymal phenotype. By analyzing RNA-sequencing data from TCGA, studies show that HPV+ HNSCC exhibited an upregulation of MHC-I- and MHC-II-related genes, which may be induced by IFN-gamma, a strong Th1 response and higher expression of the T cell “exhaustion markers” LAG3, PD1, TIGIT, and TIM3 with coordinately expressed CD39 compared to HPV− tumors at the transcription level (Gameiro et al. 2018, 2019; Ruicci et al. 2019b). However, histopathologic intratumor immune cell heterogeneity is also seen within HPV-related HNSCC. Two subtypes of HPV-related HNSCC have been identified, with an inflamed/mesenchymal phenotype enriched in CD8+ T cell infiltration leading to better survival than a classic phenotype characterized by keratinization and higher proliferation (Keck et al. 2015). In addition, cancer stem cells (CSC), a subpopulation within the bulk tumor entity of HNSCC, have shown their characteristics such as less antigen expression, processing, and presentation to induce the immunogenicity and immunosuppression (Qian et al. 2020). Further, studies demonstrate that HNSCC patients with the HPV+/CSClow phenotype had better outcomes than HPV−/CSChigh group (Reid et al. 2019). Given the paucity of molecular biomarkers, combined insights into genetic, epigenetic and transcriptional alterations can provide robust candidate biomarkers to stratify patients further and to predict treatment outcomes.

Conclusions

The molecular landscapes of HNSCC have largely been defined during the past decade. The intratumor heterogeneity (e.g., genetic, epigenetic and histopathologic) of HPV-related HNSCC has been identified as contributing to the pathophysiology of the disease. This variability contributes to the range of treatment responses observed for both established clinical practice and clinical trials. The clinical translation of these findings may help for dynamic risk restratification of HPV-related HNSCC patients with new molecular biomarkers. The management of HPV-related HNSCC is changing, and substantial research focusing on discovery approaches to cancer diagnostics and prognostic evaluations is required (Bigelow et al. 2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Medical and the Health Science Project of Zhejiang Province (2019KY327) and Guangji Talents Foundation Award (E) of Zhejiang Cancer Hospital.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Haoru Dong and Xinhua Shu contributed equally to this work.

References

- Aggarwal C, Cohen RB, Morrow MP, Kraynyak KA, Sylvester AJ, Knoblock DM, Bauml JM, Weinstein GS, Lin A, Boyer J, Sakata L, Tan S, Anton A, Dickerson K, Mangrolia D, Vang R, Dallas M, Oyola S, Duff S, Esser M, Kumar R, Weiner D, Csiki I, Bagarazzi ML. Immunotherapy targeting HPV16/18 generates potent immune responses in HPV-associated head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:110–124. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal N, Frederick MJ, Pickering CR, Bettegowda C, Chang K, Li RJ, Fakhry C, Xie TX, Zhang J, Wang J, Zhang N, El-Naggar AK, Jasser SA, Weinstein JN, Treviño L, Drummond JA, Muzny DM, Wu Y, Wood LD, Hruban RH, Westra WH, Koch WM, Califano JA, Gibbs RA, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE, Papadopoulos N, Wheeler DA, Kinzler KW, Myers JN. Exome sequencing of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma reveals inactivating mutations in NOTCH1. Science. 2011;333:1154–1157. doi: 10.1126/science.1206923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajiro M, Jia R, Zhang L, Liu X, Zheng ZM. Intron definition and a branch site adenosine at nt 385 control RNA splicing of HPV16 E6*I and E7 expression. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajiro M, Tang S, Doorbar J, Zheng ZM. Serine/Arginine-rich splicing factor 3 and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 regulate alternative RNA splicing and gene expression of human papillomavirus 18 through two functionally distinguishable cis elements. J Virol. 2016;90:9138–9152. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00965-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akagi K, Li J, Broutian TR, Padilla-Nash H, Xiao W, Jiang B, Rocco JW, Teknos TN, Kumar B, Wangsa D, He D, Ried T, Symer DE, Gillison ML. Genome-wide analysis of HPV integration in human cancers reveals recurrent, focal genomic instability. Genome Res. 2014;24:185–199. doi: 10.1101/gr.164806.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albers A, Abe K, Hunt J, Wang J, Lopez-Albaitero A, Schaefer C, Gooding W, Whiteside TL, Ferrone S, DeLeo A, Ferris RL. Antitumor activity of human papillomavirus type 16 E7-specific T cells against virally infected squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11146–11155. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albers AE, Qian X, Kaufmann AM, Coordes A. Meta analysis: HPV and p16 pattern determines survival in patients with HNSCC and identifies potential new biologic subtype. Sci Rep. 2017;7:16715. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16918-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albers AE, Strauss L, Liao T, Hoffmann TK, Kaufmann AM. T cell-tumor interaction directs the development of immunotherapies in head and neck cancer. Clin Dev Immunol. 2010;2010:236378. doi: 10.1155/2010/236378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altenhofen B, DeWees TA, Ahn JW, Yeat NC, Goddu S, Chen I, Lewis JS, Jr, Thorstad WL, Chole RA. Human papilloma virus load and PD-1/PD-L1, CD8(+) and FOXP3 in anal cancer patients treated with chemoradiotherapy: Rationale for immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1288331. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1288331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balermpas P, Martin D, Wieland U, Rave-Frank M, Strebhardt K, Rödel C, Fokas E, Rödel F (2017) Human papilloma virus load and PD-1/PD-L1, CD8(+) and FOXP3 in anal cancer patients treated with chemoradiotherapy: rationale for immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 6:e1288331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bauml J, Seiwert TY, Pfister DG, Worden F, Liu SV, Gilbert J, Saba NF, Weiss J, Wirth L, Sukari A, Kang H, Gibson MK, Massarelli E, Powell S, Meister A, Shu X, Cheng JD, Haddad R. Pembrolizumab for platinum- and cetuximab-refractory head and neck cancer: results from a single-arm, phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1542–1549. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beachler DC, Abraham AG, Silverberg MJ, Jing Y, Fakhry C, Gill MJ, Dubrow R, Kitahata MM, Klein MB, Burchell AN, Korthuis PT, Moore RD, D'Souza G. Incidence and risk factors of HPV-related and HPV-unrelated Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma in HIV-infected individuals. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:1169–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt KH, Neller MA, Srihari S, Crooks P, Lekieffre L, Aftab BT, Liu H, Smith C, Kenny L, Porceddu S, Khanna R. Profiling HPV-16-specific T cell responses reveals broad antigen reactivities in oropharyngeal cancer patients. J Exp Med. 2020;217:e20200389. doi: 10.1084/jem.20200389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow EO, Seiwert TY, Fakhry C. Deintensification of treatment for human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal cancer: Current state and future directions. Oral Oncol. 2020;105:104652. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscolo-Rizzo P, Del Mistro A, Bussu F, Lupato V, Baboci L, Almadori G. New insights into human papillomavirus-associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2013;33:77–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscolo-Rizzo P, Furlan C, Lupato V, Polesel J, Fratta E. Novel insights into epigenetic drivers of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: role of HPV and lifestyle factors. Clin Epigenetics. 2017;9:124. doi: 10.1186/s13148-017-0424-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böttinger P, Schreiber K, Hyjek E, Krausz T, Spiotto MT, Steiner M, Idel C, Booras H, Beck-Engeser G, Riederer J, Willimsky G, Wolf SP, Karrison T, Jensen E, Weichselbaum RR, Nakamura Y, Yew PY, Lambert PF, Kurita T, Kiyotani K, Leisegang M, Schreiber H. Cooperation of genes in HPV16 E6/E7-dependent cervicovaginal carcinogenesis trackable by endoscopy and independent of exogenous estrogens or carcinogens. Carcinogenesis. 2020;41:1605–1615. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgaa027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Freeman C, Galichet L, Cogliano V. A review of human carcinogens–Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:321–322. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Božinović K, Sabol I, Rakušić Z, Jakovčević A, Šekerija M, Lukinović J, Prgomet D, Grce M. HPV-driven oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer in Croatia - Demography and survival. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0211577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brant AC, Majerciak V, Moreira MAM, Zheng ZM. HPV18 utilizes two alternative branch sites for E6*I splicing to produce E7 protein. Virol Sin. 2019;34:211–221. doi: 10.1007/s12250-019-00098-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broutian TR, Jiang B, Li J, Akagi K, Gui S, Zhou Z, Xiao W, Symer DE, Gillison ML. Human papillomavirus insertions identify the PIM family of serine/threonine kinases as targetable driver genes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2020;476:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buexm LA, Soares-Lima SC, Brennan P, Fernandes PV. Hpv impact on oropharyngeal cancer patients treated at the largest cancer center from Brazil. Cancer Lett. 2020;477:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burley M, Roberts S, Parish JL. Epigenetic regulation of human papillomavirus transcription in the productive virus life cycle. Semin Immunopathol. 2020;42:159–171. doi: 10.1007/s00281-019-00773-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns MB, Temiz NA, Harris RS. Evidence for APOBEC3B mutagenesis in multiple human cancers. Nat Genet. 2013;45:977–983. doi: 10.1038/ng.2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtness B, Harrington KJ, Greil R, Soulières D, Tahara M, De Castro G, Psyrri A, Jr, Basté N, Neupane P, Bratland Å, Fuereder T, Hughes BGM, Mesía R, Ngamphaiboon N, Rordorf T, Wan Ishak WZ, Hong RL, González Mendoza R, Roy A, Zhang Y, Gumuscu B, Cheng JD, Jin F, Rischin D. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;394:1915–1928. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellsagué X, Alemany L, Quer M, Halec G, Quirós B, Tous S, Clavero O, Alòs L, Biegner T, Szafarowski T, Alejo M, Holzinger D, Cadena E, Claros E, Hall G, Laco J, Poljak M, Benevolo M, Kasamatsu E, Mehanna H, Ndiaye C, Guimerà N, Lloveras B, León X, Ruiz-Cabezas JC, Alvarado-Cabrero I, Kang CS, Oh JK, Garcia-Rojo M, Iljazovic E, Ajayi OF, Duarte F, Nessa A, Tinoco L, Duran-Padilla MA, Pirog EC, Viarheichyk H, Morales H, Costes V, Félix A, Germar MJ, Mena M, Ruacan A, Jain A, Mehrotra R, Goodman MT, Lombardi LE, Ferrera A, Malami S, Albanesi EI, Dabed P, Molina C, López-Revilla R, Mandys V, González ME, Velasco J, Bravo IG, Quint W, Pawlita M, Muñoz N, de Sanjosé S, Xavier Bosch F. HPV Involvement in Head and Neck Cancers: Comprehensive Assessment of Biomarkers in 3680 Patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108:403. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chargi N, Bril SI, Swartz JE, Wegner I, Willems SM, de Bree R. Skeletal muscle mass is an imaging biomarker for decreased survival in patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2020;101:104519. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.104519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Lortet-Tieulent J, Curado MP, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Rosenberg PS, Bray F, Gillison ML. Worldwide trends in incidence rates for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4550–4559. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TC, Wu CT, Ko JY, Yang TL, Lou PJ, Wang CP, Chang YL. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcome of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in an endemic betel quid region. Sci Rep. 2020;10:526. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57177-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chor JS, Vlantis AC, Chow TL, Fung SC, Ng FY, Lau CH, Chan AB, Ho LC, Kwong WH, Fung MN, Lam EW, Mak KL, Lam HC, Kok AS, Ho WC, Yeung AC, Chan PK. The role of human papillomavirus in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a case control study on a southern Chinese population. J Med Virol. 2016;88:877–887. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen JT, Grønhøj C, Zamani M, Brask J, Kjær EKR, Lajer H, von Buchwald C. Association between oropharyngeal cancers with known HPV and p16 status and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a Danish population-based study. Acta Oncol. 2019;58:267–272. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2018.1546059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang SC, Scelo G, Tonita JM, Tamaro S, Jonasson JG, Kliewer EV, Hemminki K, Weiderpass E, Pukkala E, Tracey E, Friis S, Pompe-Kirn V, Brewster DH, Martos C, Chia KS, Boffetta P, Brennan P, Hashibe M. Risk of second primary cancer among patients with head and neck cancers: a pooled analysis of 13 cancer registries. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2390–2396. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillo AR, Kürten CHL, Tabib T, Qi Z, Onkar S, Wang T, Liu A, Duvvuri U, Kim S, Soose RJ, Oesterreich S, Chen W, Lafyatis R, Bruno TC, Ferris RL, Vignali DAA. Immune Landscape of Viral- and Carcinogen-Driven Head and Neck Cancer. Immunity. 2020;52:183–199.e189. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colevas AD, Bahleda R, Braiteh F, Balmanoukian A, Brana I, Chau NG, Sarkar I, Molinero L, Grossman W, Kabbinavar F, Fassò M, O'Hear C, Powderly J. Safety and clinical activity of atezolizumab in head and neck cancer: results from a phase I trial. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:2247–2253. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KL, Shaik AN, Ekinci E, Kim S, Ruterbusch JJ, Cote ML, Patrick SM. HPV induction of APOBEC3 enzymes mediate overall survival and response to cisplatin in head and neck cancer. DNA Repair (amst) 2020;87:102802. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2020.102802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Paredes A, De la Cruz-Hernández E, Martínez-Ramírez I, Dueñas-González A, Lizano M. E6 variants of human papillomavirus 18 differentially modulate the protein kinase B/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (akt/PI3K) signaling pathway. Virology. 2009;383:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer JD, Burtness B, Ferris RL. Immunotherapy for head and neck cancer: Recent advances and future directions. Oral Oncol. 2019;99:104460. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.104460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui T, Enroth S, Ameur A, Gustavsson I, Lindquist D, Gyllensten U. Invasive cervical tumors with high and low HPV titer represent molecular subgroups with different disease etiology. Carcinogenesis. 2019;40:269–278. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgy183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cicco R, de Melo MR, Nicolau UR, Pinto CAL, Villa LL, Kowalski LP. Impact of human papillomavirus status on survival and recurrence in a geographic region with a low prevalence of HPV-related cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Head Neck. 2020;42:93–102. doi: 10.1002/hed.25985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Felice F, Bird T, Michaelidou A, Thavaraj S, Odell E, Sandison A, Hall G, Morgan P, Lyons A, Cascarini L, Fry A, Oakley R, Simo R, Jeannon JP, Lei M, Guerrero Urbano T. Radical (chemo) radiotherapy in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: comparison of TNM 7th and 8th staging systems. Radiother Oncol. 2020;145:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Martel C, Georges D, Bray F, Ferlay J, Clifford GM. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: a worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e180–e190. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30488-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickstein DR, Egerman MA, Bui AH, Doucette JT, Sharma S, Liu J, Gupta V, Miles BA, Genden E, Westra WH, Misiukiewicz K, Posner MR, Bakst RL. A new face of the HPV epidemic: oropharyngeal cancer in the elderly. Oral Oncol. 2020;109:104687. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dsouza G, Carey TE, William WN, Jr, Nguyen ML, Ko EC, Jt R, Pai SI, Gupta V, Walline HM, Lee JJ, Wolf GT, Shin DM, Grandis JR, Ferris RL. Epidemiology of head and neck squamous cell cancer among HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65:603–610. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt M, Zhang W, Gross AM, Von Dollen J, Johnson JR, Franks-Skiba KE, Swaney DL, Johnson TL, Jang GM, Shah PS, Brand TM, Archambault J, Kreisberg JF, Grandis JR, Ideker T, Krogan NJ. Multiple routes to oncogenesis are promoted by the human papillomavirus-host protein network. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1474–1489. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhalawani H, Mohamed ASR, Elgohari B, Lin TA, Sikora AG, Lai SY, Abusaif A, Phan J, Morrison WH, Gunn GB, Rosenthal DI, Garden AS, Fuller CD, Sandulache VC. Tobacco exposure as a major modifier of oncologic outcomes in human papillomavirus (HPV) associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:912. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07427-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facompre ND, Rajagopalan P, Sahu V, Pearson AT, Montone KT, James CD, Gleber-Netto FO, Weinstein GS, Jalaly J, Lin A, Rustgi AK, Nakagawa H, Califano JA, Pickering CR, White EA, Windle BE, Morgan IM, Cohen RB, Gimotty PA, Basu D. Identifying predictors of HPV-related head and neck squamous cell carcinoma progression and survival through patient-derived models. Int J Cancer. 2020;147:3236–3249. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhry C, Lacchetti C, Rooper LM, Jordan RC, Rischin D, Sturgis EM, Bell D, Lingen MW, Harichand-Herdt S, Thibo J, Zevallos J, Perez-Ordonez B. Human papillomavirus testing in head and neck carcinomas: ASCO clinical practice guideline endorsement of the college of american pathologists guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:3152–3161. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhry C, Waterboer T, Westra WH, Rooper LM, Windon M, Troy T, Koch W, Gourin CG, Bender N, Yavvari S, Kiess AP, Miles BA, Ryan WR, Ha PK, Eisele DW, D'Souza G (2020) Distinct biomarker and behavioral profiles of human papillomavirus-related oropharynx cancer patients by age. Oral Oncol 101:104522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ferris RL, Blumenschein G, Jr, Fayette J, Guigay J, Colevas AD, Licitra L, Harrington KJ, Kasper S, Vokes EE, Even C, Worden F, Saba NF, Docampo LCI, Haddad R, Rordorf T, Kiyota N, Tahara M, Lynch M, Jayaprakash V, Li L, Gillison ML. Nivolumab vs investigator's choice in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: 2-year long-term survival update of CheckMate 141 with analyses by tumor PD-L1 expression. Oral Oncol. 2018;81:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag J, Wald T, Kuhnt T, Gradistanac T, Kolb M, Dietz A, Wiegand S, Wichmann G. Extracapsular extension of neck nodes and absence of human papillomavirus 16-DNA are predictors of impaired survival in p16-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2020;126:1856–1872. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvis MM, Borges GA, Oliveira TB, Toledo IP, Castilho RM, Guerra ENS, Kowalski LP, Squarize CH. Immunotherapy improves efficacy and safety of patients with HPV positive and negative head and neck cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2020;150:102966. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.102966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gameiro SF, Ghasemi F, Barrett JW, Koropatnick J, Nichols AC, Mymryk JS, Maleki Vareki S. Treatment-naïve HPV+ head and neck cancers display a T-cell-inflamed phenotype distinct from their HPV- counterparts that has implications for immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1498439. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1498439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gameiro SF, Ghasemi F, Barrett JW, Nichols AC, Mymryk JS. High level expression of MHC-II in HPV+ head and neck cancers suggests that tumor epithelial cells serve an important role as accessory antigen presenting cells. Cancers (basel) 2019;11:1129. doi: 10.3390/cancers11081129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhapudi SK, Ward M, Bush JPC, Bedu-Addo F, Conn G, Woodward JG. Antigen priming with enantiospecific cationic lipid nanoparticles induces potent antitumor CTL responses through novel induction of a type I IFN response. J Immunol. 2019;202:3524–3536. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1801634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Escudero R, Segrelles C, Dueñas M, Pombo M, Ballestín C, Alonso-Riaño M, Nenclares P, Álvarez-Rodríguez R, Sánchez-Aniceto G, Ruíz-Alonso A, López-Cedrún JL, Paramio JM, Lorz C. Overexpression of PIK3CA in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma is associated with poor outcome and activation of the YAP pathway. Oral Oncol. 2018;79:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaździcka J, Gołąbek K, Strzelczyk JK, Ostrowska Z. Epigenetic modifications in head and neck cancer. Biochem Genet. 2020;58:213–244. doi: 10.1007/s10528-019-09941-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaz MJ, Jeffery C, O'Connell D, Harris J, Seikaly H, Biron V. Association of human papillomavirus related squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx and cervix. Papillomavirus Res. 2019;8:100188. doi: 10.1016/j.pvr.2019.100188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillison ML, Akagi K, Xiao W, Jiang B, Pickard RKL, Li J, Swanson BJ, Agrawal AD, Zucker M, Stache-Crain B, Emde AK, Geiger HM, Robine N, Coombes KR, Symer DE. Human papillomavirus and the landscape of secondary genetic alterations in oral cancers. Genome Res. 2019;29:1–17. doi: 10.1101/gr.241141.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Fakhry C. Epidemiology of human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3235–3242. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillison ML, Trotti AM, Harris J, Eisbruch A, Harari PM, Adelstein DJ, Jordan RCK, Zhao W, Sturgis EM, Burtness B, Ridge JA, Ringash J, Galvin J, Yao M, Koyfman SA, Blakaj DM, Razaq MA, Colevas AD, Beitler JJ, Jones CU, Dunlap NE, Seaward SA, Spencer S, Galloway TJ, Phan J, Dignam JJ, Le QT. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab or cisplatin in human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer (NRG Oncology RTOG 1016): a randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2019;393:40–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32779-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardi FM, Wagner VP, Martins MD, Abentroth AL, Hauth LA. Prevalence of p16 expression in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in southern Brazil. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2020.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grønhøj C, Jensen JS, Wagner S, Dehlendorff C, Friborg J, Andersen E, Wittekindt C, Würdemann N, Sharma SJ, Gattenlöhner S, Klussmann JP, von Buchwald C. Impact on survival of tobacco smoking for cases with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma and known human papillomavirus and p16-status: a multicenter retrospective study. Oncotarget. 2019;10:4655–4663. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.27079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grønhøj C, Kronberg Jakobsen K, Kjær E, Friborg J, von Buchwald C. Comorbidity in HPV+ and HPV- oropharyngeal cancer patients: a population-based, case-control study. Oral Oncol. 2019;96:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T, Zambo KDA, Zamuner FT, Ou T, Hopkins C, Kelley DZ, Wulf HA, Winkler E, Erbe R, Danilova L, Considine M, Sidransky D, Favorov A, Florea L, Fertig EJ, Gaykalova DA. Chromatin structure regulates cancer-specific alternative splicing events in primary HPV-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Epigenetics. 2020;15:959–971. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2020.1741757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SF, Griffiths RJ, O'Sullivan B, Liu FF. The addition of chemotherapy to radiotherapy did not reduce the rate of distant metastases in low-risk HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer in a real-world setting. Head Neck. 2019;41:2271–2276. doi: 10.1002/hed.25679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarstedt L, Holzhauser S, Zupancic M, Kapoulitsa F, Ursu RG, Ramqvist T, Haeggblom L, Näsman A, Dalianis T, Marklund L. The value of p16 and HPV DNA in non-tonsillar, non-base of tongue oropharyngeal cancer. Acta Otolaryngol. 2020;141:89–94. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2020.1813906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque SU, Niu L, Kuhnell D, Hendershot J, Biesiada J, Niu W, Hagan MC, Kelsey KT, Casper KA, Wise-Draper TM, Medvedovic M, Langevin SM. Differential expression and prognostic value of long non-coding RNA in HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2018;40:1555–1564. doi: 10.1002/hed.25136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatano T, Sano D, Takahashi H, Hyakusoku H, Isono Y, Shimada S, Sawakuma K, Takada K, Oikawa R, Watanabe Y, Yamamoto H, Itoh F, Myers JN, Oridate N. Identification of human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 DNA integration and the ensuing patterns of methylation in HPV-associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:1571–1580. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson S, Chakravarthy A, Su X, Boshoff C, Fenton TR. APOBEC-mediated cytosine deamination links PIK3CA helical domain mutations to human papillomavirus-driven tumor development. Cell Rep. 2014;7:1833–1841. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SH, O'Sullivan B, Su J, Ringash J, Bratman SV, Kim J, Hosni A, Bayley A, Cho J, Giuliani M, Hope A, Spreafico A, Hansen AR, Siu LL, Gilbert R, Irish JC, Goldstein D, de Almeida J, Tong L, Xu W, Waldron J. Hypofractionated radiotherapy alone with 2.4 Gy per fraction for head and neck cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic: the Princess Margaret experience and proposal. Cancer. 2020;126:3426–3437. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebbers CU, Verhees F, Poluschkin L, Olthof NC, Kolligs J, Siefer OG, Henfling M, Ramaekers FCS, Preuss SF, Beutner D, Seehawer J, Drebber U, Korkmaz Y, Lam WL, Vucic EA, Kremer B, Klussmann JP, Speel EM. Upregulation of AKR1C1 and AKR1C3 expression in OPSCC with integrated HPV16 and HPV-negative tumors is an indicator of poor prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:2465–2477. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson LM, Antonsson A, Garvey G, Ju X, Smith M, Logan RM, Johnson NW, Hedges J, Sethi S, Dunbar T, Leane C, Hill I, Brown A, Roder D, De Souza M, Canfell K. Prevalence of oral human papillomavirus infection among australian indigenous adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e204951. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.4951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph AW, Ogawa T, Bishop JA, Lyford-Pike S, Chang X, Phelps TH, Westra WH, Pai SI. Molecular etiology of second primary tumors in contralateral tonsils of human papillomavirus-associated index tonsillar carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:244–248. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck MK, Zuo Z, Khattri A, Stricker TP, Brown CD, Imanguli M, Rieke D, Endhardt K, Fang P, Brägelmann J, DeBoer R, El-Dinali M, Aktolga S, Lei Z, Tan P, Rozen SG, Salgia R, Weichselbaum RR, Lingen MW, Story MD, Ang KK, Cohen EE, White KP, Vokes EE, Seiwert TY. Integrative analysis of head and neck cancer identifies two biologically distinct HPV and three non-HPV subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:870–881. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DA, Arora KS, Mahadevan KK, Hornick JL, Krane JF, Rivera MN, Ting DT, Deshpande V, Faquin WC. Performance of a branch chain RNA In Situ hybridization assay for the detection of high-risk human papillomavirus in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:1643–1652. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirnbauer R, Booy F, Cheng N, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Papillomavirus L1 major capsid protein self-assembles into virus-like particles that are highly immunogenic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:12180–12184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofler B, Borena W, Dudas J, Innerhofer V, Dejaco D, Steinbichler TB, Widmann G, von Laer D, Riechelmann H. Post-treatment HPV surface brushings and risk of relapse in oropharyngeal carcinoma. Cancers (basel) 2020;12:1069. doi: 10.3390/cancers12051069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo S, Wakae K, Wakisaka N, Nakanishi Y, Ishikawa K, Komori T, Moriyama-Kita M, Endo K, Murono S, Wang Z, Kitamura K, Nishiyama T, Yamaguchi K, Shigenobu S, Muramatsu M, Yoshizaki T. APOBEC3A associates with human papillomavirus genome integration in oropharyngeal cancers. Oncogene. 2017;36:1687–1697. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koneva LA, Zhang Y, Virani S, Hall PB, McHugh JB, Chepeha DB, Wolf GT, Carey TE, Rozek LS, Sartor MA. HPV integration in HNSCC correlates with survival outcomes, immune response signatures, and candidate drivers. Mol Cancer Res. 2018;16:90–102. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-17-0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopczyńska M, Kolenda T, Guglas K, Sobocińska J, Teresiak A, Bliźniak R, Mackiewicz A, Mackiewicz J, Lamperska K. PRINS lncRNA Is a new biomarker candidate for HPV infection and prognosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Diagnostics (basel) 2020;10:762. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10100762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostareli E, Hielscher T, Zucknick M, Baboci L, Wichmann G, Holzinger D, Mücke O, Pawlita M, Del Mistro A, Boscolo-Rizzo P, Da Mosto MC, Tirelli G, Plinkert P, Dietz A, Plass C, Weichenhan D, Hess J. Gene promoter methylation signature predicts survival of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients. Epigenetics. 2016;11:61–73. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2015.1137414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostareli E, Holzinger D, Bogatyrova O, Hielscher T, Wichmann G, Keck M, Lahrmann B, Grabe N, Flechtenmacher C, Schmidt CR, Seiwert T, Dyckhoff G, Dietz A, Höfler D, Pawlita M, Benner A, Bosch FX, Plinkert P, Plass C, Weichenhan D, Hess J. HPV-related methylation signature predicts survival in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2488–2501. doi: 10.1172/JCI67010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna S, Ulrich P, Wilson E, Parikh F, Narang P, Yang S, Read AK, Kim-Schulze S, Park JG, Posner M, Wilson Sayres MA, Sikora A, Anderson KS. Human papilloma virus specific immunogenicity and dysfunction of CD8(+) T cells in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2018;78:6159–6170. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon S, Ahn SH, Jeong WJ, Jung YH, Bae YJ, Paik JH, Chung JH, Kim H. Estrogen receptor α as a predictive biomarker for survival in human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2020;18:240. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02396-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang Kuhs KA, Kreimer AR, Trivedi S, Holzinger D, Pawlita M, Pfeiffer RM, Gibson SP, Schmitt NC, Hildesheim A, Waterboer T, Ferris RL. Human papillomavirus 16 E6 antibodies are sensitive for human papillomavirus-driven oropharyngeal cancer and are associated with recurrence. Cancer. 2017;123:4382–4390. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]