Abstract

Alternariol (AOH) and ochratoxin A (OTA), two mycotoxins found in many foods worldwide, exhibit cytotoxicity and embryotoxicity, triggering apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in several mammalian cells and mouse embryos. The absorption rate of AOH from dietary foodstuff is low, meaning that the amount of AOH obtained from the diet rarely approaches the cytotoxic threshold. Thus, the potential harm of dietary consumption of AOH is generally neglected. However, previous findings from our group and others led us to question whether a low dosage of AOH could aggravate the cytotoxicity of other mycotoxins. In the present study, we examined how low dosages of AOH affected OTA-triggered apoptosis and embryotoxicity and investigated the underlying regulatory mechanism in mouse blastocysts. Our results revealed that non-cytotoxic concentrations of AOH (1 and 2 μM) could enhance OTA (8 μM)-triggered apoptotic processes and embryotoxicity in mouse blastocysts. We also found that AOH can enhance OTA-evoked intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and that this could be prevented by pretreatment with the potent ROS scavenger, N-acetylcysteine. Finally, we observed that this ROS generation acts as a key inducer of caspase-dependent apoptotic processes and subsequent impairments of embryo implantation and pre- and post-implantation embryonic development. In sum, our results show that non-cytotoxic dosages of AOH can aggravate OTA-triggered apoptosis and embryotoxicity through ROS- and caspase-dependent signaling pathways.

Keywords: alternariol, apoptosis, ochratoxin A, oxidative stress, embryonic development

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Alternariol (AOH) is a major secondary metabolite produced by the genus Alternaria. This mycotoxin may be found in various foods, such as fruits, vegetables, cereals and their related manufactured foods (e.g. juice, wine and cereal-based infant food) [1–4]. The concentrations of AOH found in various foods are within 0.65– 54 μg/kg [5, 6]. In Italy, 56% of 45 food samples were positive for contamination with AOH, which was found at levels of 270.7 μg/kg in fresh, 428.4 μg/kg in dried, and 1110.8 μg/kg in ground samples [7, 8]. Thus, both humans and livestock are chronically exposed to AOH via their daily food intake [9]. Previous studies have demonstrated that AOH has cytotoxic activity in several cell lines, triggering intracellular ROS generation and causing various deleterious effects, including DNA damage, cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest [10–18]. Importantly, recent investigations showed that AOH exerts hazardous effects on porcine oocyte maturation and initial embryonic development in vitro [19]. Moreover, we recently reported that AOH (5 μM in vitro and 3 mg/kg/day in vivo) triggers ROS-mediated apoptosis predominantly in the inner cell mass (ICM) of blastocysts, leading to impairment of pre- and post-implantation embryonic development both in vitro and in vivo [20]. Thus, AOH has a high potential to be an embryotoxic risk factor and teratogen.

Ochratoxin A (OTA), a major metabolite produced by Aspergillus and Penicillium, is a mycotoxin that is commonly found as a contaminant of various foods, including beans, grains, cereals and spices, and their manufactured food products [21]. OTA has also been found in coffee, grape juice, wine, beer and bread [22]. Because OTA is found in so many common consumables, it is very difficult to avoid being exposed to this mycotoxin [23, 24]. A hazardous effects analysis found that OTA has nephrotoxic and hepatotoxic activities and can cause neurodegenerative disease [25]. OTA has also been demonstrated to be a potent carcinogen that can induce various tumors, such as kidney, mammary gland and liver cancers [26–28]. Importantly, our previous investigation found that OTA could trigger apoptosis in the mouse blastocysts via ROS- and mitochondrion-dependent pathways to cause deleterious effects on pre- and post-implantation embryonic development [29]. Moreover, OTA also significantly impaired mouse oocyte maturation, decreased fertilization rates, and inhibited subsequent embryonic development in vitro and in vivo [30]. These studies emphasized that OTA is a potent teratogen that can impair normal embryonic development.

Apoptosis is an important regulatory mechanism through which redundant or abnormal cells are removed during normal embryonic development [31, 32]. The induction of apoptosis in a pre-implantation-stage embryo (from zygote to blastocyst stage) could cause various deleterious effects on embryogenesis and/or subsequent embryonic development [33–36]. Our previous studies showed that OTA triggers apoptosis-mediated impairments in mouse oocyte maturation and/or blastocyst embryonic development via reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and promotes mitochondrion-dependent apoptotic signaling processes to cause deleterious effects on subsequent embryonic development [29, 30]. In the present study, we investigated whether non-embryotoxic dosages of the apoptosis-inducing teratogen, AOH, could aggravate OTA-triggered injury effects on embryonic development, and further examined the potential underlying regulatory mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and reagents

Ochratoxin A, alternariol, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG), bovine serum albumin (BSA), polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), propidium iodide (PI), bisbenzimidine, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (H2DCF-DA), N-acetylcysteine (NAC), human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), sodium pyruvate, Z-IETD-FMK, Z-LEHD-FMK and Z-DEVD-FMK were acquired from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). The TUNEL in situ cell death detection kit (product number: 11684817910) was purchased from Roche (Mannheim, Germany). CMRL-1066 medium was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). TRIzol reagent and the reverse transcriptase kit were from Takara Biomedicals (Tokyo, Japan).

Collection of mouse embryos

ICR mice were obtained from the National Laboratory Animal Center (Taiwan, ROC). All study processes in animals were approved by the Animal Research Ethics Board of Chung Yuan Christian University (Taiwan, ROC). ICR mice were given food and water ad libitum and housed in standard 28 cm × 16 cm × 11 cm (height) polypropylene cages with wire-grid tops under a 12 h/12 h night–day regimen, following the Guide to The Care and Use of Experimental Animals (Canadian Council on Animal Care, Ottawa, 1993; ISBN: 0-919087-18-3). For in vitro and in vivo experiments, 6–8 mice were used in each mycotoxin-treated group.

For induction of superovulation in mice, 6- to 8-week-old nulliparous female ICR mice were injected with 5 IU PMSG. Forty-eight hours later, the PMSG-injected mice were further injected with 5 IU hCG and female ICR mice were each housed with a single fertile ICR male mouse (one pair per cage) overnight for mating. The next day morning, vaginal plugs were checked; plug-positive female mice were defined as being at Day 0 of gestation and separated for further embryo collection. Cervical dislocation was carried out to sacrifice mice for embryo collection. On the afternoon of gestation Day 3, morulae were collected by flushing of uterine tubes. Blastocysts were obtained by flushing of the uterine horn on Day 4. CMRL-1066 medium containing 1 mM glutamine and 1 mM sodium pyruvate was used as the flushing solution for the collection of morulae and blastocysts. Pools of embryos collected from different females were randomly allocated to the various experimental groups.

Assessment of morula developmental potential in vitro

Measurement of morula developmental potential in vitro was carried out according to our previously reported protocol [33]. Briefly, morulae were treated in vitro with culture medium containing various concentrations of AOH and/or OTA as indicated or 0.5% DMSO (vehicle control) at 37°C for 24 h. The embryos were transferred to mycotoxin-free culture medium and further cultured for an additional 24 h at 37°C. Embryos incubated with 0.5% DMSO exhibited no significant difference relative to the phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)- or medium-treated (pure control) embryo groups, strongly demonstrating that 0.5% DMSO does not exert hazardous effects (data not shown). Thus, in our experiments, 0.5% DMSO-treated embryos were used in the vehicle control groups, which are indicated in the study figures as being treated with 0 μM mycotoxin (AOH and/or OTA). Blastocyst numbers were counted and developmental percentages were calculated under phase-contrast microscopy (Olympus BX51, Tokyo, Japan).

TUNEL analysis of apoptotic cells in embryos

Embryos were treated with various concentrations of AOH and/or OTA as indicated. AOH and/or OTA were dissolved in DMSO at a final concentration of up to 0.5% (v/v) for 24 h. The terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay was used to measure apoptotic cell numbers. In brief, embryos were washed three times in embryo culture medium and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 2 h. The embryos were then permeabilized and labeled following the protocol provided with the utilized TUNEL assay kit. Briefly, each group of embryos was incubated with 20 μl TUNEL reaction mixture (2 μl enzyme solution and 18 μl labeling solution containing fluorescein-conjugated nucleotides) for 30 min at 37°C, washed three times with PBS containing 0.3% (w/v) BSA and further incubated with converted POD solution (20 μl) for 30 min at 37°C. Each group of embryos was then incubated with 20 μl 3,3′-diaminobenzidine substrate solution for 2 min, and apoptotic cells were visualized using fluorescence microscopy. Black spots representing apoptotic (TUNEL-positive) cells were counted under light microscopy.

Measurement of cell proliferation

Blastocysts were incubated with or without the indicated concentrations of AOH and/or OTA for 24 h and washed three times with mycotoxin-free culture medium. Dual differential staining to facilitate counting of cell numbers in the ICM and trophectoderm (TE) was performed according to a previously reported protocol [37]. In brief, embryos were incubated with 0.4% pronase in M2-BSA medium (M2 containing 0.1% BSA) to remove the zona pellucida, and the denuded blastocysts were treated with 1 mM trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid in BSA-free M2 medium containing 0.1% PVP at 4°C for 30 min [38]. The embryos were then washed three times with M2 medium and further incubated with anti-dinitrophenol-BSA complex antibody (30 μg/ml in M2-BSA) at room temperature for 30 min. Following three washes with M2-BSA, the embryos were incubated with M2 supplemented with 10% whole guinea pig serum (as a complement source), bisbenzimide (20 μg/ml) and PI (10 μg/ml) at room temperature for 30 min. The cell numbers of the ICM and TE were estimated by counting nuclei under fluorescence microscopy. In the differential staining, nuclei of ICM cells (which take up bisbenzimidine but exclude PI) emitted blue fluorescence while TE cells (which take up both PI and bisbenzimide) emitted orange–red fluorescence.

Assessment of embryonic development in vitro

The status of in vitro blastocyst development was monitored based on morphological analyses and previous reports [33]. In brief, blastocysts were cultured in fibronectin-coated dishes and incubated with culture medium (1 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 50 IU/ml penicillin and 50 mg/ml streptomycin in CMRL-1066 medium) supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated human placental cord serum for 8 days. At the same time each day, embryonic development status was assessed and recorded by photography under phase-contrast microscopy. After continuous recording for 8 days, morphological scores of development status in each group were classified according to previously established methods [33] as attachment only, ICM (+), ICM (++) or ICM (+++). Attachment-only status was defined as embryo implantation (binding) with no further development. ICM (+), ICM (++) and ICM (+++) were defined according to shape, ranging from compact and rounded ICM (+++) to a few scattered cells (+) over the trophoblastic layer [33, 39, 40].

Embryo transfer assay

The embryo transfer assay was performed as described in our previous reports [33, 35]. Forty ICR female mice were used as recipient (dams) for the embryo transfer assay. In brief, pseudopregnant recipient mice were prepared for embryo transfer by mating ICR females (white skin color) with vasectomized males (C57BL/6 J; black skin color). To assess the implantation of mycotoxin-treated or control blastocysts into the uteri of dams and their subsequent post-implantation developmental status, blastocysts were cultured in medium containing various concentrations of AOH and/or OTA, or 0.5% DMSO (control group). After incubation for 24 h, embryos were washed three times with medium, and 16 embryos were transferred to each pseudopregnant recipient mouse. Eight mycotoxin-treated day-5 embryos were transferred into the left uterine horn, and eight control embryos were transferred into the right uterine horn of each recipient mouse. All recipient mice were sacrificed on Day 13 post-transfer (Day 18 post-coitus), and embryonic developmental status (number of implantation sites and placental and fetal weights) was assessed. Embryo resorption sites (white appearance), which are formed by implanted embryos that did not further develop into healthy fetuses and were subsequently resorbed, were counted.

The ratio of survival or implantation followed by resorption was calculated as the number of surviving or resorbed fetuses, respectively, per the number of total transferred embryos. The percentage of implantation, resorption or survival represents the number of implantations, resorbed fetuses or surviving fetuses per the number of transferred embryos × 100. Weights of surviving fetuses and placenta were measured and recorded immediately after dissection.

Assessment of intracellular ROS generation

Intracellular ROS generation was measured by staining with the ROS-detecting, cell membrane-permeable fluorescence dye, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA; 20 μM) [41]. H2DCF-DA (representing the reduced state) has low fluorescence; it penetrates into the cell cytosol, where intracellular esterases cleave it to form the oxidized H2DCF− (DCF), which is highly fluorescent. Blastocysts were pre-incubated with H2DCF-DA (20 μM) for 30 min, washed three times with PBS and treated with or without AOH (0.5, 1, or 2 μM) plus 8 μM OTA or 0.5% DMSO alone (control) for a further 24 h. The fluorescence intensity of intracellular ROS in each group was observed and measured under fluorescence microscopy. The fluorescence intensity was quantitatively analyzed using the Image J software.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of experimental data was performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons. Data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) and P < 0.05 was taken as representing a significant difference.

Results

Non-cytotoxic concentrations of AOH aggravate OTA-triggered embryotoxicity in mouse blastocysts

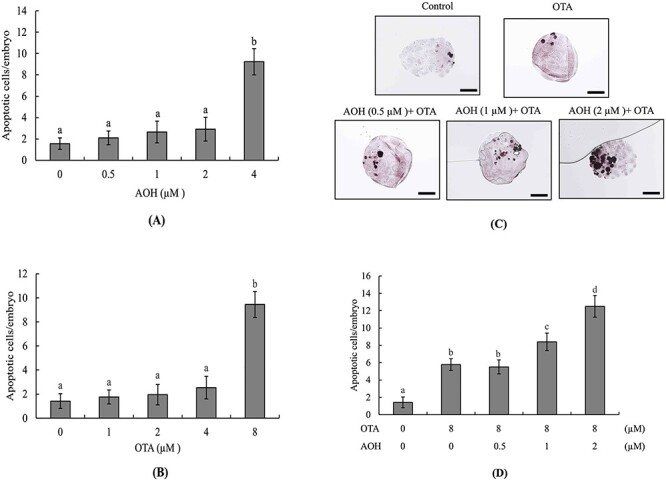

To analyze the effects of AOH and OTA on mouse embryos, we first treated blastocysts with AOH (0–4 μM) or OTA (0–8 μM) for 24 h and measured apoptotic cells by TUNEL assay. The results revealed that treatment with 4 μM AOH or 8 μM OTA could effectively induce cell apoptosis (Fig. 1A and B). To assess whether a non-cytotoxic concentration of AOH could aggravate OTA-induced embryonic toxicity, blastocysts were treated with AOH (0, 0.5, 1, or 2 μM) plus 8 μM OTA for 24 h. Our results revealed that treatment with 1 or 2 μM AOH plus 8 μM OTA significantly increased cell apoptosis compared with OTA alone (Fig. 1C and D). To further determine the impact of AOH plus OTA on cell proliferation, differential staining was used to facilitate cell counting of the ICM and TE of each blastocyst. Embryos co-treated with 1 or 2 μM AOH plus 8 μM OTA had significantly fewer ICM cells and total cell numbers, and those treated with 2 μM AOH plus 8 μM OTA had slightly fewer TE cells, compared to the vehicle (control) group or the group treated with 8 μM OTA alone (Fig. 1E). Our results therefore suggested that 1 or 2 μM AOH plus 8 μM OTA induced a major hazardous effect on ICM cells and a minor hazardous effect on TE cells. The significantly lower ICM and total cell numbers in groups treated with 1 or 2 μM AOH plus 8 μM OTA are consistent with the idea that non-cytotoxic concentrations of AOH enhance the ability of OTA to cause deleterious effects on blastocysts by inducing apoptosis of ICM cells (majorly) and TE cells (to a smaller degree) and possibly triggering cell cycle arrest and/or inhibiting proliferation in mouse blastocyst-stage embryos.

Figure 1.

Effects of combined treatment with AOH plus OTA on mouse blastocysts. Mouse blastocysts were exposed to various concentrations of AOH and/or OTA as indicated for 24 h. Vehicle (0.5% DMSO)-treated mice were used as a control group. Cell apoptosis was detected by TUNEL staining. Apoptosis-positive cells were observed as black spots under light microscopy and counted per blastocyst. (A) Apoptotic cells in AOH (0.5, 1, 2, and 4 μM)-treated groups were counted and the numbers of apoptotic cells per blastocyst were determined. (B) Apoptotic cells in OTA (1, 2, 4, and 8 μM)-treated groups were counted and the numbers of apoptotic cells per blastocyst were determined. (C and D) Apoptosis-positive cells in groups treated with AOH (0–2 μM) plus 8 μM OTA were detected (C) and counted (D). (E and F) Cells of the ICM and TE of blastocysts were subjected to differential staining (E) and counted (F). Data were obtained from 240 blastocysts per group. Values are presented as means ± SD of eight determinations. Different symbols indicate significant differences at P < 0.05. Scale bar = 20 μm.

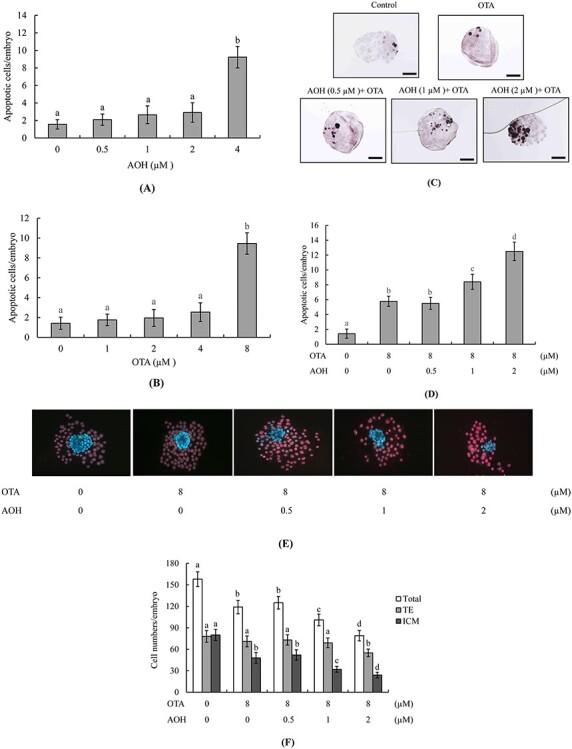

Non-cytotoxic concentrations of AOH aggravate the deleterious effects of OTA on in vitro embryonic development

To further investigate whether AOH can enhance the ability of OTA to negatively impact the developmental potential of embryos, we analyzed the ratio at which morulae developed to blastocyst-stage embryos. The morula-to-blastocyst developmental ratios of groups treated with 1 or 2 μM AOH plus 8 μM OTA were significantly lower than that of the group treated with OTA alone (Fig. 2A). To further investigate the effects of AOH plus OTA on embryo post-implantation potential in vitro, blastocysts were incubated with AOH (0, 0.5, 1, or 2 μM) plus 8 μM OTA for 24 h and then cultured on fibronectin-coated dishes for 7 days. The developmental characteristics of each embryo were assessed and recorded daily. Our results revealed that the embryo implantation potential (the proportion of blastocysts that attached to the fibronectin-coated culture dish) was significantly lower in the groups treated with 1 or 2 μM AOH plus 8 μM OTA compared to those treated with OTA alone or the vehicle (control) group (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

In vitro development of mouse embryos treated with AOH plus OTA. (A) Mouse morulae were treated with or without AOH (0.5, 1 or 2 μM) plus 8 μM OTA for 24 h and cultured for an additional 24 h. Morulae treated with 0.5% DMSO were used as the control (vehicle) group. Blastocyst percentages were calculated. (B, C) Mouse blastocysts were incubated with or without AOH (0.5, 1 or 2 μM) plus 8 μM OTA for 24 h, and then cultured in fibronectin-coated dishes for 7 days. After 24 h, blastocysts attached to dishes were defined as implanted and percentages were calculated (B). After 7 days in culture, morphological assessment was performed and the embryo outgrowth status was classified as attachment only, ICM+, ICM++ or ICM+++, as described in the Materials and Methods section (C). Values are presented as means ± SD of six determinations. Data were obtained from 160 blastocysts per group. Different symbols indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

We used the embryonic development morphology index to further assess the post-implantation status of embryos on fibronectin-coated culture dishes. Our results clearly showed that embryos treated with 1 or 2 μM AOH plus 8 μM OTA had lower development scores than those treated with OTA alone (Fig. 2C). These findings collectively demonstrated that non-cytotoxic concentrations of AOH aggravated the OTA-induced decrease in post-implantation development potential to cause deleterious effects on embryo implantation and post-implantation potential.

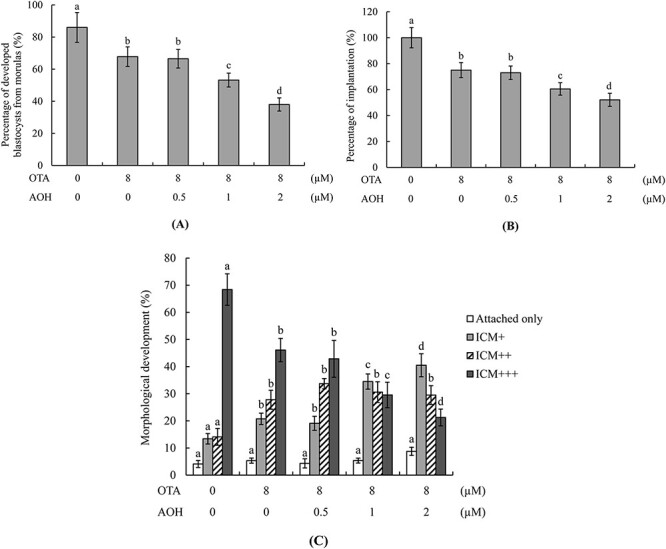

Effect of AOH plus OTA on embryonic development potential in vivo

Embryo transfer assays were further used to analyze embryonic development potential in vivo. Blastocysts were treated with 0–2 μM AOH and/or 8 μM OTA or vehicle (control) for 24 h and transferred to the uteri of pseudopregnant recipient mice. At 13 days post-transfer (Day 18 post-coitus) embryonic development status in the uterus was assessed. The results revealed that groups treated with 1 or 2 μM AOH plus 8 μM OTA showed lower implantation ratios and higher embryo resorption rates than those treated with 8 μM OTA alone (Fig. 3A). The measurement of placental weights revealed that this parameter was significantly lower in the group treated with 2 μM AOH plus 8 μM OTA compared with those treated with either toxin alone or with 0–1 μM AOH plus 8 μM OTA (Fig. 3B). Our group and others previously reported that about 35–40% of fetuses weigh >600 mg at Day 18 of pregnancy in mouse embryo transfer assays, and the average weight of a Day-18 fetus is ~600 ± 12 mg [33, 42–46]. Fetal weight is accepted as an important indicator and parameter for assessing fetal developmental status in various pregnancy periods. Based on the abovementioned reports, we applied the average fetal weight of the untreated control group as a key standard index and indicator for monitoring the fetal developmental status in the AOH and/or OTA-treated groups. The fetal weights of groups treated with 1 or 2 μM AOH plus 8 μM OTA were markedly lower than that of the group treated with 8 μM OTA alone (Fig. 3C). Overall, we observed a significantly lower proportion of fetuses weighing >600 mg in the groups treated with 1 or 2 μM AOH plus 8 μM OTA compared to that treated with 8 μM OTA alone (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Effects of AOH plus OTA on the in vivo implantation, resorption, fetal survival and fetal weights of mouse blastocysts. (A) Mouse blastocysts were exposed to AOH (0, 0.5, 1 or 2 μM) plus 8 μM OTA or with vehicle only (0.5% DMSO as control group) for 24 h. Embryo implantation, fetal resorption, and fetal survival were analyzed via embryo transfer assay, as described in the Materials and Methods section. The implantation percentage represents the number of implanted embryos in uteri per the number of transferred embryos × 100. The percentage of resorption or survival signifies the number of resorbed or surviving fetuses per the number of transferred embryos × 100. (B) Average placental weights from 40 pseudopregnant recipient mice (dams). (C) Day 13 post-transfer surviving fetuses (Day 18 fetuses) from embryo transfer of 320 total blastocysts across 40 recipients were analyzed. Fetal weight distributions were measured and analyzed. Different symbols indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

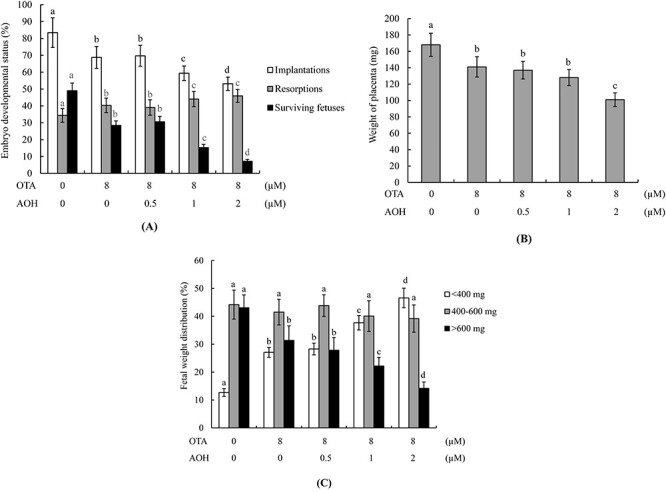

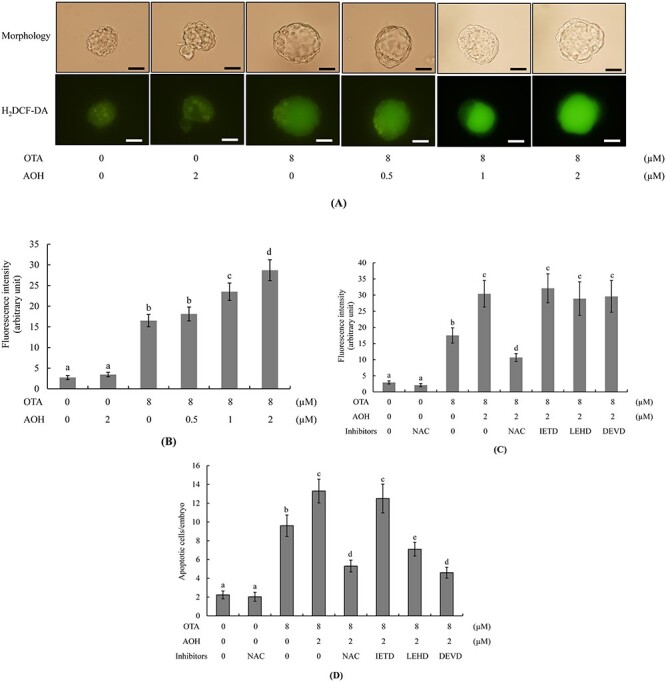

Role of ROS generation in AOH-aggravated OTA-triggered impairment of embryonic development

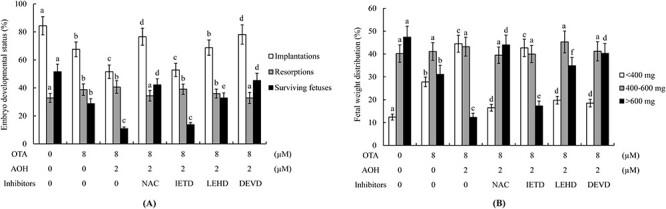

Our previous studies demonstrated that ROS generation is an important mediator of the abilities of AOH or OTA to exert deleterious effects on embryonic development [20, 29]. Here, we further investigated whether oxidative stress generation is involved in AOH aggravated OTA-induced apoptosis and subsequent impairment of embryonic development. The intracellular ROS levels of groups treated with 1 or 2 μM AOH plus 8 μM OTA were significantly higher than that in the group treated with 8 μM OTA alone (Fig. 4A and B). Pre-incubation with NAC, a well-known ROS scavenger, effectively prevented this ROS generation (Fig. 4C). The cell apoptosis of blastocysts treated with 1 or 2 μM AOH plus 8 μM OTA or 8 μM OTA alone was effectively prevented by pretreatment with NAC or Z-LEHD-FMK (LEHD), specific inhibitors of caspase-9, or Z-DEVD-FMK (DEVD), specific inhibitors of caspase-3, but no such rescue effect was observed with the Z-IETD-FMK (IETD), a specific inhibitor of caspase-8 (Fig. 4D). Embryo transfer assay experiments showed that pretreatment with NAC or specific inhibitors of caspase-9 or caspase-3, but not caspase-8, effectively prevented the ability of 1 or 2 μM AOH plus 8 μM OTA or 8 μM OTA alone to decrease implantation and fetal survival, increase the resorption rate (Fig. 5A) or decrease the fetal weight (Fig. 5B) at 13 days post-transfer. In contrast, the specific inhibitor of caspase-8 had no such rescue effect (Fig. 5A and B). These results suggest that ROS-dependent processes involving caspase-9 and -3 can regulate AOH-aggravated OTA-triggered apoptosis and impairment of embryonic development, and that ROS is an important upstream regulator of caspase-9 and caspase-3 activation and downstream apoptotic cascades in this context.

Figure 4.

Effects of NAC and caspase inhibitors on the developmental status of AOH plus OTA-treated embryos. Mouse blastocysts were pre-incubated with 5 mM NAC, 300 μM Z-IETD-FMK (IETD), 300 μM Z-LEHD-FMK (LEHD) or 300 μM Z-DEVD-FMK (DEVD) for 30 min or left untreated, followed by treatment with or without AOH (0.5, 1 or 2 μM) plus 8 μM OTA or 0.5% DMSO alone (control) for a further 24 h. (A and C) ROS generation was measured by staining with 20 μM H2DCF-DA fluorescence dye. (B and C) The fluorescence intensity of intracellular ROS in each group was quantitatively analyzed using the Image J software. (D) Assessment of apoptosis via TUNEL staining. Mean numbers of apoptotic (TUNEL-positive) cells per blastocyst were calculated. Values are presented as means ± SD of five determinations. Data were obtained from 150 blastocysts per group. Different symbols indicate significant differences at P < 0.05. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Figure 5.

Effects of NAC and caspase inhibitors on post-implantation developmental status of AOH/OTA-treated embryos subjected to embryo transfer. Mouse blastocysts were pre-incubated with 5 mM NAC, 300 μM Z-IETD-FMK (IETD), 300 μM Z-LEHD-FMK (LEHD) or 300 μM Z-DEVD-FMK (DEVD) for 30 min or left untreated, followed by treatment with or without AOH (0.5, 1 or 2 μM) plus 8 μM OTA or 0.5% DMSO alone (control) for a further 24 h. (A) Embryo implantation, fetal resorption, and fetal survival were analyzed via an embryo transfer assay as described in the Materials and Methods section. (B) Weight distribution of surviving fetuses on Day 18 (Day 13 post-transfer) was measured. Values are presented as means ± SD of five determinations. Data were obtained from 240 blastocysts per group. Different symbols indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

Discussion

The developmental processes of early-stage embryos are very complex and precisely orchestrated, especially in pre-implantation and implantation embryos. At these embryonic stages, various external teratogens, including chemical, physical and biological factors, have high potential to cause hazardous impacts and disturb normal embryonic development, even leading to abortion. It is thus important to detect and investigate various potential teratogens that can impact embryogenesis, such as the mycotoxins that may contaminate common daily-intake foods. We previously reported that OTA triggers cell apoptosis specifically in the ICM, with no cytotoxic effect on the TE of mouse blastocysts, and that it exerts its embryotoxic effects through ROS- and mitochondrion-dependent pathways to impair embryonic development and viability in vitro and in vivo [29, 30, 34]. We also demonstrated that AOH induces apoptosis predominantly in the ICM and to a minor extent in TE of mouse blastocysts to cause deleterious effects on cell viability and subsequent pre- and post-implantation embryonic development in vitro and in vivo [20]. Mechanistically, we reported that intracellular ROS generation acts as a critical upstream regulator of caspase-9 and caspase-3 activation and related apoptotic processes, leading to impairments of early-stage embryogenesis in OTA-treated embryos [29, 34]. Daily-intake foods have high potential to be contaminated with multiple exotoxins and/or secondary metabolites of microorganisms. For this reason, we herein studied for the first time whether a sub-cytotoxic dosage of AOH could aggravate OTA-induced apoptotic processes and embryotoxicity, and further examined some regulatory mechanisms in mouse blastocysts. Our results revealed that ROS act as important upstream mediators of AOH-aggravated OTA-induced deleterious effects on embryonic development.

Accumulating evidence indicates that cells exposed to risk factors that trigger intracellular ROS generation at levels exceeding the buffering ability of the endogenous ROS protection system or redox buffering system can trigger various injury effects on cell fate. Excess intracellular ROS has been reported to harm critical biomolecules, including DNA, lipids and proteins, and cause damage to cell membranes [47]. Several studies showed that AOH can induce ROS via AOH metabolic processes and/or products in various mammalian cell lines [13, 15, 17]. We very recently reported that intracellular ROS levels in AOH-treated blastocysts trigger hazardous effects on early-stage mouse embryonic development, and that intravenous injection of pregnant mice with AOH was associated with significantly higher ROS contents in liver cell extracts of 1-day-old newborn mice [20]. These previous study results emphasize that AOH is a potent ROS inducer in mammalian cells and early-stage embryos.

Our prior investigation also revealed that OTA can induce intracellular ROS generation to trigger apoptosis, leading to serious hazardous impacts on early-stage embryonic development, and that NAC pretreatment can significantly, but not fully, prevent OTA-induced ROS generation and deleterious effects in mouse blastocysts [29]. This incomplete inhibition suggested that OTA may trigger apoptotic processes via one or more additional pathways beyond intracellular ROS generation, such as through chemical covalent modification of nucleic acids to form the DNA adducts. Several types of AOH-triggered DNA damage have been reported, including single-stranded breaks, double-stranded breaks, and oxidative DNA damage [3]. AOH has also been reported to interact with DNA topoisomerase to inhibit the enzyme activity of topoisomerase I and II [17, 48]. Given this, it is not unexpected that the antioxidant failed to fully block AOH plus OTA-triggered ROS generation and apoptosis in mouse blastocyst-stage embryos (Fig. 4D and E). The present study shows for the first time that a non-ROS-inducing dosage of AOH can synergistically evoke ROS generation in OTA-treated embryos, potentially explaining why a non-embryotoxic dosage of AOH can aggravate OTA-induced apoptosis and embryonic impairments in mouse blastocyst-stage embryos. Although additional investigations will be required to analyze this possibility in detail, our present work provides important new insights into the negative impacts of AOH plus OTA on early embryonic development.

Two major apoptotic signaling cascades have been identified: intrinsic and extrinsic. The extrinsic pathway is triggered through the specific binding of an extracellular ligand to membrane death receptors. This activates cytosolic caspase-8 to turn on downstream apoptotic cascades. The intrinsic pathway, in contrast, is triggered through the generation of reactive free radicals or ROS, which damage cell structures, such as membranes and/or DNA. These damages activate a mitochondrion-dependent apoptotic cascade that includes the induction of cytochrome c release, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, activation of caspase-9 and development of subsequent apoptotic events. Our previous studies demonstrated that OTA and AOH trigger ROS generation to induce intrinsic apoptotic signaling events leading to mitochondrion-dependent apoptotic processes in mouse blastocyst cells [20, 29]. In the current study, our results demonstrate that AOH-aggravated OTA-triggered apoptosis occurs through intrinsic apoptosis cascades, involving in ROS generation and the activations of caspase-9 and caspase-3, with no involvement of caspase-8 (representing extrinsic apoptosis) (Fig. 4D). Our results further show that this intrinsic apoptotic signaling leads to impairment of embryonic development, and that ROS is an important upstream regulator of caspase-9 and caspase-3 activation and downstream apoptotic cascades in this context (Fig. 5).

Blastocyst-stage embryos are primarily comprised of TE and ICM cells. The TE plays important roles in the implantation of the embryo in the uterus and thereafter collaborates with inner lining cells of the uterus to form the placenta [49, 50]. ICM cells largely develop to form the fetus, and make some contribution to embryo implantation [51]. Several studies have demonstrated that factors leading to loss or impairment of TE cell lineages can exert hazardous effects on embryo implantation potential, promoting abortion [33, 37, 52–54]. The loss and/or impairment of ICM cells can also cause major injury to post-implantation fetal development [33, 53–56]. We previously reported that OTA triggered apoptosis in ICM cells, but not TE cells, whereas AOH triggered apoptosis in ICM cells and (minorly) in TE cells [29]. In this study, we further demonstrated that a non-embryotoxic dosage of AOH plus an embryotoxic dose of OTA aggravated cell death predominantly in the ICM and minorly in the TE (Fig. 1E). These results reveal that TE cells have higher tolerance than ICM cells for ROS-caused apoptosis and damage, and point out that different differentiation fates of embryo cells (such as TE and ICM) have different tolerances and thresholds for ROS-triggered injury effects. The contribution of ICM cells to embryo implantation could reasonably explain why AOH aggravates OTA-induced impairments not only for post-implantation embryonic and fetal development, but also for embryo implantation and placenta development in vitro and in vivo (Figs 2 and 3).

Conclusion

Our present results for the first time demonstrate that non-embryotoxic dosages of AOH can aggravate OTA-induced apoptotic processes and deleterious effects in mouse blastocyst-stage embryos. Apoptotic cells are detected predominantly in the ICM and to a minor extent in the TE of mouse blastocysts, and these changes decrease cell viability and the potential for embryonic implantation and development both in vitro and in vivo. Our further results showed that this aggravating effect of AOH on the OTA-induced impairments of embryonic development occur via increased ROS generation: AOH plus OTA triggers intracellular ROS generation to activate caspase-9 and caspase-3, causing hazardous impacts on pre- and post-implantation embryonic development in mouse blastocysts. These finding importantly show that the mycotoxins, AOH and OTA, have synergistic embryotoxic properties and should be viewed as important potential embryotoxic agents.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Author contributions

Wen-Hsiung Chan conceived and designed the experiments. Chien-Hsun Huang, Fu-Ting Wang, Yan-Der Hsuuw and Fu-Jen Huang performed the experiments. All authors analyzed and interpreted the data. Wen-Hsiung Chan wrote the paper. All authors contributed to the final approval of manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, ROC (MOST 109-2311-B-033-001 and MOST 110-2314-B-715-012-).

Contributor Information

Chien-Hsun Huang, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Taoyuan General Hospital, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taoyuan City 33004, Taiwan.

Fu-Ting Wang, Rehabilitation and Technical Aid Center, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei City 11217, Taiwan.

Yan-Der Hsuuw, Department of Tropical Agriculture and International Cooperation, National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, Pingtung 91201, Taiwan.

Fu-Jen Huang, Department of Tropical Agriculture and International Cooperation, National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, Pingtung 91201, Taiwan; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, An-An Women and Children Clinic & ART Center, Kaohsiung City 80752, Taiwan.

Wen-Hsiung Chan, Department of Bioscience Technology and Center for Nanotechnology, Chung Yuan Christian University, Chung Li District, Taoyuan City 32023, Taiwan.

References

- 1. EFSA, Arcella D, Eskola M et al. Scientific report on the dietary exposure assessment to Alternaria toxins in the European population. EFSA J 2016;14:4654–86. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ackermann Y, Curtui V, Dietrich R et al. Widespread occurrence of low levels of alternariol in apple and tomato products, as determined by comparative immunochemical assessment using monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies. J Agric Food Chem 2011;59:6360–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Solhaug A, Eriksen GS, Holme JA. Mechanisms of action and toxicity of the mycotoxin Alternariol: a review. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2016;119:533–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. López P, Venema D, de Rijk T et al. Occurrence of Alternaria toxins in food products in the Netherlands. Food Control 2016;60:196–204. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hickert S, Bergmann M, Ersen S et al. Survey of Alternaria toxin contamination in food from the German market, using a rapid HPLC-MS/MS approach. Mycotoxin Res 2016;32:7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gotthardt M, Asam S, Gunkel K et al. Quantitation of six Alternaria toxins in infant foods applying stable isotope Labeled standards. Front Microbiol 2019;10:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gambacorta L, Magista D, Perrone G et al. Co-occurrence of toxigenic moulds, aflatoxins, ochratoxin a, fusarium and Alternaria mycotoxins in fresh sweet peppers (Capsicum annuum) and their processed products. World Mycotoxin J 2018;11:159–73. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Puntscher H, Kutt ML, Skrinjar P et al. Tracking emerging mycotoxins in food: development of an LC-MS/MS method for free and modified Alternaria toxins. Anal Bioanal Chem 2018;410:4481–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Escrivá L, Oueslati S, Font G, Manyes L. Alternaria mycotoxins in food and feed: an overview. J Food Qual 2017;2017:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schreck I, Deigendesch U, Burkhardt B et al. The Alternaria mycotoxins alternariol and alternariol methyl ether induce cytochrome P450 1A1 and apoptosis in murine hepatoma cells dependent on the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Arch Toxicol 2012;86:625–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bensassi F, Gallerne C, el Dein OS et al. Mechanism of Alternariol monomethyl ether-induced mitochondrial apoptosis in human colon carcinoma cells. Toxicology 2011;290:230–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fernandez-Blanco C, Juan-Garcia A, Juan C et al. Alternariol induce toxicity via cell death and mitochondrial damage on Caco-2 cells. Food Chem Toxicol 2016;88:32–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Solhaug A, Vines LL, Ivanova L et al. Mechanisms involved in alternariol-induced cell cycle arrest. Mutat Res 2012;738-739:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wollenhaupt K, Schneider F, Tiemann U. Influence of alternariol (AOH) on regulator proteins of cap-dependent translation in porcine endometrial cells. Toxicol Lett 2008;182:57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fernandez-Blanco C, Font G, Ruiz MJ. Oxidative stress of alternariol in Caco-2 cells. Toxicol Lett 2014;229:458–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vila-Donat P, Fernandez-Blanco C, Sagratini G et al. Effects of soyasaponin I and soyasaponins-rich extract on the alternariol-induced cytotoxicity on Caco-2 cells. Food Chem Toxicol 2015;77:44–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tiessen C, Fehr M, Schwarz C et al. Modulation of the cellular redox status by the Alternaria toxins alternariol and alternariol monomethyl ether. Toxicol Lett 2013;216:23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bensassi F, Gallerne C, Sharaf El Dein O et al. Cell death induced by the Alternaria mycotoxin Alternariol. Toxicol in Vitro 2012;26:915–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schoevers EJ, Santos RR, Roelen BAJ. Alternariol disturbs oocyte maturation and preimplantation development. Mycotoxin Res 2020;36:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huang CH, Wang FT, Chan WH. Alternariol exerts embryotoxic and immunotoxic effects on mouse blastocysts through ROS-mediated apoptotic processes. Toxicol Res 2021;10:719–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. CAST . Mycotoxins: risks in plant, animal, and human systems. council of agricultural science and technology, task force rep. no. 139. Ames, IA: CAST, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22. IPCS . Safety evaluation of certain mycotoxins in food. WHO Food Addit Ser 2001;47:103–415. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Walker R. Risk assessment of ochratoxin: current views of the European scientific committee on food, the JECFA and the codex committee on food additives and contaminants. Adv Exp Med Biol 2002;504:249–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pfohl-Leszkowicz A, Manderville RA. Ochratoxin a: an overview on toxicity and carcinogenicity in animals and humans. Mol Nutr Food Res 2007;51:61–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang X, Boesch-Saadatmandi C, Lou Y et al. Ochratoxin a induces apoptosis in neuronal cells. Genes Nutr 2009;4:41–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kanisawa M, Suzuki S. Induction of renal and hepatic tumors in mice by ochratoxin a, a mycotoxin. Gann 1978;69:599–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kanisawa M. Pathogenesis of human cancer development due to environmental factors. Gan No Rinsho 1984;30:1445–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boorman G. NTP Technical Report on the Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Ochratoxin A (CAS No. 303-47-9) in F344/N Rats (Gavage Studies). NTP TR 358, NIH Publication No. 89–2813 . US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health, Research Triangle Park, NC. 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hsuuw YD, Chan WH, Yu JS. Ochratoxin a inhibits mouse embryonic development by activating a mitochondrion-dependent apoptotic signaling pathway. Int J Mol Sci 2013;14:935–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huang FJ, Chan WH. Effects of ochratoxin a on mouse oocyte maturation and fertilization, and apoptosis during fetal development. Environ Toxicol 2016;31:724–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hardy K. Cell death in the mammalian blastocyst. Mol Hum Reprod 1997;3:919–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hardy K, Stark J, Winston RM. Maintenance of the inner cell mass in human blastocysts from fragmented embryos. Biol Reprod 2003;68:1165–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huang CH, Wang FT, Chan WH. Enniatin B1 exerts embryotoxic effects on mouse blastocysts and induces oxidative stress and immunotoxicity during embryo development. Environ Toxicol 2019;34:48–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huang CH, Wang FT, Chan WH. Prevention of ochratoxin A-induced oxidative stress-mediated apoptotic processes and impairment of embryonic development in mouse blastocysts by liquiritigenin. Environ Toxicol 2019;34:573–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Huang CH, Huang ZW, Ho FM et al. Berberine impairs embryonic development in vitro and in vivo through oxidative stress-mediated apoptotic processes. Environ Toxicol 2018;33:280–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Huang CH, Chan WH. Rhein induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in mouse blastocysts and has immunotoxic effects during embryonic development. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pampfer S, de Hertogh R, Vanderheyden I et al. Decreased inner cell mass proportion in blastocysts from diabetic rats. Diabetes 1990;39:471–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hardy K, Handyside AH, Winston RM. The human blastocyst: cell number, death and allocation during late preimplantation development in vitro. Development 1989;107:597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pampfer S, Wuu YD, Vanderheyden I et al. In vitro study of the carry-over effect associated with early diabetic embryopathy in the rat. Diabetologia 1994;37:855–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Huang LH, Shiao NH, Hsuuw YD et al. Protective effects of resveratrol on ethanol-induced apoptosis in embryonic stem cells and disruption of embryonic development in mouse blastocysts. Toxicology 2007;242:109–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Diaz G, Liu S, Isola R et al. Mitochondrial localization of reactive oxygen species by dihydrofluorescein probes. Histochem Cell Biol 2003;120:319–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huang FJ, Hsuuw YD, Lan KC et al. Adverse effects of retinoic acid on embryo development and the selective expression of retinoic acid receptors in mouse blastocysts. Hum Reprod 2006;21:202–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chan WH. Impact of genistein on maturation of mouse oocytes, fertilization, and fetal development. Reprod Toxicol 2009;28:52–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chan WH, Shiao NH. Cytotoxic effect of CdSe quantum dots on mouse embryonic development. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2008;29:259–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chan WH, Shiao NH. Effect of citrinin on mouse embryonic development in vitro and in vivo. Reprod Toxicol 2007;24:120–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chan WH. Ginkgolide B induces apoptosis and developmental injury in mouse embryonic stem cells and blastocysts. Hum Reprod 2006;21:2985–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Orrenius S. Reactive oxygen species in mitochondria-mediated cell death. Drug Metab Rev 2007;39:443–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fehr M, Pahlke G, Fritz J et al. Alternariol acts as a topoisomerase poison, preferentially affecting the IIalpha isoform. Mol Nutr Food Res 2009;53:441–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cross JC. How to make a placenta: mechanisms of trophoblast cell differentiation in mice-a review. Placenta 2005;26:S3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kunath T, Strumpf D, Rossant J. Early trophoblast determination and stem cell maintenance in the mouse-a review. Placenta 2004;25:S32–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pedersen RA, Wu K, Balakier H. Origin of the inner cell mass in mouse embryos: cell lineage analysis by microinjection. Dev Biol 1986;117:581–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kelly SM, Robaire B, Hales BF. Paternal cyclophosphamide treatment causes postimplantation loss via inner cell mass-specific cell death. Teratology 1992;45:313–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chan WH. Cytotoxic effects of dillapiole on embryonic development of mouse blastocysts in vitro and in vivo. Int J Mol Sci 2014;15:10751–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Huang FJ, Chin TY, Chan WH. Resveratrol protects against methylglyoxal-induced apoptosis and disruption of embryonic development in mouse blastocysts. Environ Toxicol 2013;28:431–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lane M, Gardner DK. Differential regulation of mouse embryo development and viability by amino acids. J Reprod Fertil 1997;109:153–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cross JC, Werb Z, Fisher SJ. Implantation and the placenta: key pieces of the development puzzle. Science 1994;266:1508–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]