Abstract

Background

Recreational physical activity (RPA) is associated with improved survival after breast cancer (BC) in average-risk women, but evidence is limited for women who are at increased familial risk because of a BC family history or BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants (BRCA1/2 PVs).

Methods

We estimated associations of RPA (self-reported average hours per week within 3 years of BC diagnosis) with all-cause mortality and second BC events (recurrence or new primary) after first invasive BC in women in the Prospective Family Study Cohort (n = 4610, diagnosed 1993-2011, aged 22-79 years at diagnosis). We fitted Cox proportional hazards regression models adjusted for age at diagnosis, demographics, and lifestyle factors. We tested for multiplicative interactions (Wald test statistic for cross-product terms) and additive interactions (relative excess risk due to interaction) by age at diagnosis, body mass index, estrogen receptor status, stage at diagnosis, BRCA1/2 PVs, and familial risk score estimated from multigenerational pedigree data. Statistical tests were 2-sided.

Results

We observed 1212 deaths and 473 second BC events over a median follow-up from study enrollment of 11.0 and 10.5 years, respectively. After adjusting for covariates, RPA (any vs none) was associated with lower all-cause mortality of 16.1% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.4% to 27.9%) overall, 11.8% (95% CI = -3.6% to 24.9%) in women without BRCA1/2 PVs, and 47.5% (95% CI = 17.4% to 66.6%) in women with BRCA1/2 PVs (RPA*BRCA1/2 multiplicative interaction P = .005; relative excess risk due to interaction = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.01 to 1.74). RPA was not associated with risk of second BC events.

Conclusion

Findings support that RPA is associated with lower all-cause mortality in women with BC, particularly in women with BRCA1/2 PVs.

Breast cancer (BC) is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related death in women globally (1). Women diagnosed with BC are at risk of disease recurrence, second cancers, and premature death, underscoring the need for identifying modifiable factors that improve outcomes after diagnosis (2,3). There is extensive epidemiological evidence supporting that recreational physical activity (RPA) is associated with reduced BC risk (4-6) and improved outcomes after BC diagnosis in women at average risk of developing BC (7-10). Most of the evidence on RPA and outcomes after BC comes from studies of average-risk cohorts that were not selected for age at diagnosis or other BC-related risk factors and thus not powered to detect associations in women at increased familial or genetic risk, such as those with a BC family history or BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants (hereafter referred to as BRCA1/2 PVs). BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated BCs are usually diagnosed at a younger age and have different frequencies of certain histological and cell biological characteristics compared with sporadic breast tumors (11). The mortality risk associated with modifiable factors, such as RPA, might thus be different in high-risk populations compared with estimates from average-risk women. Therefore, studies of RPA and outcomes after BC in enriched cohorts are needed to provide accurate risk estimates and evidence-based guidance for women at increased familial or genetic risk of BC.

We previously studied 4153 women from 3 of the 6 study centers in the Breast Cancer Family Registry (BCFR), a cohort enriched for women with a BC family history and/or early onset BC (2), and found that women in the highest vs lowest quintile of prediagnosis RPA had 23.0% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.0% to 40.0%) lower all-cause mortality. This association was not modified on the multiplicative scale by BC family history, but we did not test for additive interaction, which is important for understanding the impact of RPA on absolute number of outcomes prevented (2). Our evaluation of effect modification by familial risk was also limited in that we excluded women with BRCA1/2 PVs and used a binary definition of BC family history (any first-degree relatives with BC vs none), which discounts the strong gradient in familial risk that varies based on genetics and number, age, and relationship (eg, first-degree) of affected relatives (12-16). It is estimated that individuals in the top 25% of familial risk are 20 times more likely to develop BC than those of the same age and sex in the bottom 25% of familial risk (17). We have previously used a continuous measure of familial risk to show that the association between RPA and BC risk is consistent across the continuum of familial risk (18). Here, we extend this research to study the role of RPA in all-cause mortality and second BC events (recurrence or new primary BC) in women with BC across the continuum of familial risk, including those with BRCA1/2 PVs.

Methods

Study Sample

We used data from the Prospective Family Study Cohort, which includes 31 640 women (n = 18 858 and 12 782 women unaffected and affected with BC at baseline, respectively) from 11 171 families in the BCFR (19) and the kConFab Follow-Up Study (20,21). The BCFR recruited families from 6 sites in Australia, Canada, and the United States (New York, Northern California, Philadelphia, and Utah), and kConFab recruited families in Australia and New Zealand. The Northern California site conducted population-based recruitment using cancer registries, and the New York, Philadelphia, and Utah sites of the BCFR, as well as kConFab, used clinic-based recruitment. The Australian and Canadian sites of the BCFR used both population-based and clinic-based recruitment strategies. Additional details on the sampling schemes are available elsewhere (12). We restricted the primary analysis to women with a first diagnosis of invasive BC within 2 years prior to study enrollment (n = 5735 women diagnosed 1993-2011) to reduce the effect of survivorship bias. We excluded women without a familial risk score either because they were aged 80 years or older at baseline (n = 34) or did not have sufficient pedigree data (n = 232). Additionally, we excluded women missing data on RPA (n = 656) or covariates (n = 177) or who had no follow-up time after baseline (n = 26). For second BC events analyses, we further excluded women with a bilateral mastectomy (n = 236) or second invasive BC event (n = 18) before baseline. The final sample sizes for our all-cause mortality and second BC events analyses were 4610 (374 women with BRCA1/2 PVs) and 4356 (316 women with BRCA1/2 PVs), respectively. The BCFR and kConFab were approved by the institutional review board at each participating study center; all participants provided written informed consent.

Baseline Data

The BCFR and kConFab used similar baseline questionnaires to collect information on sociodemographic, lifestyle, cancer treatment, and other factors. Both cohorts asked participants to report their average hours per week of moderate (eg, brisk walking) and strenuous (eg, running) RPA around the time of first invasive BC diagnosis, which we converted to total metabolic equivalents (MET) hours per week (22). Participants in the kConFab (n = 479) and case probands selected through population-based recruitment in the BCFR (n = 3486) were asked the RPA questions in reference to the 3 years prior to their first invasive BC diagnosis. The remaining 14.0% (n = 645) of participants (clinic-based recruits and family members of probands from the population-based sites) were asked the same RPA questions but in reference to the 3 years prior to study enrollment. Apart from the timing of the exposure period, the phrasing of the RPA questions was the same across sites. Women reported their height and weight for the time period at which RPA was measured, which we used to calculate body mass index (BMI). Multigenerational pedigree data were collected by baseline questionnaire to estimate remaining lifetime (from enrollment to age 80 years) familial risk of BC using the Breast Ovarian Analysis of Disease Incidence and Carrier Estimation Algorithm v3 (23,24).

Outcomes

We updated vital status through telephone contact, mailed questionnaires, and linkage with cancer registries and national death registries. We observed 1212 deaths (106 with BRCA1/2 PVs) over a median follow-up from study enrollment of 11.0 years (total follow-up = 50 873 person-years). We defined a second BC event as an invasive BC diagnosis at least 6 months after the first invasive diagnosis in the ipsilateral or contralateral breast, including a recurrence or new primary tumor. We observed 473 second BC events (53 with BRCA1/2 PVs) over a median follow-up from study enrollment of 10.5 years (total follow-up from study enrollment = 45 590 person-years). Of the BCs in the study sample, 96% were confirmed by pathology reports or cancer registry records. These records were also used to obtain information on tumor characteristics, including estrogen receptor (ER) status, progesterone receptor (PR) status, and stage at diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

We used multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression to examine associations of RPA with all-cause mortality and second BC events. We evaluated RPA as a dichotomous variable (any, none) and categorized by intensity level (none, moderate only, strenuous with or without moderate RPA). We also evaluated RPA levels based on whether the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans and the World Health Organization guidelines of 150-300 minutes per week of moderate RPA or 75-150 minutes per week of strenuous RPA were met or exceeded (25,26). Finally, we categorized total MET hours per week into quintiles based on the distribution in the study sample and evaluated linear trends using the Wald test statistic by modeling a continuous term that used the median value for each quintile. Follow-up time was calculated from date of first invasive BC diagnosis to date of death or last known contact in analyses of all-cause mortality, and from date of first invasive BC diagnosis to date of second invasive BC diagnosis, last known contact, or death in analyses of second BC events. Follow-up time was left truncated at the date of interview to avoid potential survival bias. Because some of the women with BC were related, we used a robust variance estimator to account for the family structure of the cohort. We evaluated Schoenfeld residuals to verify the proportional hazards assumption.

We fitted models adjusted for the following baseline covariates that were associated with the outcomes in our analysis: age group at diagnosis, study center, decade of birth year, race and ethnicity, education, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, postmenopausal hormone therapy, BMI, stage at diagnosis, and treatment of first invasive BC (chemotherapy, radiation, surgery). ER status, PR status, hormone therapy treatment for first invasive BC, year of first invasive BC diagnosis, prior tamoxifen use, and number of mammograms were not associated with the outcomes and were removed from models for parsimony. To explore whether associations were modified by underlying familial or genetic risk of BC, we tested for multiplicative interactions using the Wald test statistic for cross-product terms between RPA and familial risk score, as well as between RPA and BRCA1/2 PVs status (women without genetic test results [n = 1099] were categorized with women who tested negative [n = 3137]). We fitted models stratified by age at diagnosis to evaluate associations in younger women with few competing risks of death other than BC (27,28). We also tested for effect modification by BMI, ER status, and stage at diagnosis (subgroups selected a priori). We calculated the relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) to test for additive interactions.

Sensitivity Analyses

We evaluated associations in the following subsamples: women with a confirmed invasive BC from pathology report or cancer registry records (n = 4441); women with stage 1 or 2 BC (n = 3301); women unaffected with other cancers except nonmelanoma skin cancer (n = 3980); women without a bilateral oophorectomy (n = 4236); and women with a genetic test result for BRCA1/2 PVs (n = 3511). We also evaluated whether findings were robust to different inclusion and exclusion criteria: 1) including women diagnosed with BC within 5 years of baseline, 2) excluding women diagnosed after 2008 (allowing for at least 10 years of follow-up), and 3) excluding women diagnosed before 1995. For second BC events, we fitted models that censored at bilateral mastectomy after baseline (n = 239). We fitted models with cross-product terms to evaluate if associations differed between cohorts (kConFab vs BCFR) or exposure windows (3 years prior to first invasive BC diagnosis vs 3 years prior to study enrollment). All statistical tests were 2-sided, and P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Average level of RPA in the cohort was 22.1 (SD = 23.3) MET hours per week; 16.3% of the cohort reported no moderate or strenuous RPA around the time of first invasive BC diagnosis. Average age at first invasive BC diagnosis was 47.9 (SD = 10.2) years and average BMI was 26.2 (SD = 5.8) kg/m2. Weak, but statistically significant, negative correlations were found between higher RPA and age at first invasive BC diagnosis (Spearman ρ = -0.08; P < .001) and RPA and BMI (ρ = -0.13; P < .001). Characteristics of the all-cause mortality sample are presented in Table 1 by RPA quintiles; characteristics were similar in the second BC events sample. A comparison of women by BRCA1/2 PVs status is provided in Supplementary Table 1 (available online).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Prospective Family Study Cohort by quintiles of recreational physical activity (n = 4610)

| Characteristic | Q1 <4 MET-hrs/wk |

Q2 4-11 MET-hrs/wk |

Q3 12-20 MET-hrs/wk |

Q4 21-34 MET-hrs/wk |

Q5 >34 MET-hrs/wk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. of women | 857 | 910 | 1193 | 781 | 869 |

| Age at first invasive BC diagnosis, No. (%), y | |||||

| <40 | 158 (18.4) | 194 (21.3) | 245 (20.5) | 195 (25.0) | 264 (30.4) |

| 40-49 | 269 (31.4) | 316 (34.7) | 379 (31.8) | 238 (30.5) | 276 (31.8) |

| 50-59 | 304 (35.5) | 279 (30.7) | 408 (34.2) | 237 (30.3) | 227 (26.1) |

| ≥60 | 126 (14.7) | 121 (13.3) | 161 (13.5) | 111 (14.2) | 102 (11.7) |

| Year of birth, No. (%) | |||||

| <1950 | 435 (50.8) | 414 (45.5) | 580 (48.6) | 353 (45.2) | 332 (38.2) |

| 1950-1959 | 263 (30.7) | 292 (32.1) | 364 (30.5) | 242 (31.0) | 263 (30.3) |

| 1960-1969 | 133 (15.5) | 178 (19.6) | 206 (17.3) | 156 (20.0) | 224 (25.8) |

| ≥1970 | 26 (3.0) | 26 (2.9) | 43 (3.6) | 30 (3.8) | 50 (5.8) |

| Race and ethnicity, No. (%) | |||||

| Asian | 158 (18.4) | 107 (11.8) | 133 (11.1) | 68 (8.7) | 55 (6.3) |

| Hispanic | 104 (12.1) | 134 (14.7) | 134 (11.2) | 70 (9.0) | 131 (15.1) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 57 (6.7) | 41 (4.5) | 191 (16.0) | 109 (14.0) | 44 (5.1) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 514 (60.0) | 608 (66.8) | 708 (59.3) | 522 (66.8) | 613 (70.5) |

| Other | 24 (2.8) | 20 (2.2) | 27 (2.3) | 12 (1.5) | 26 (3.0) |

| Educational attainment, No. (%) | |||||

| High school graduate/GED or less | 374 (43.6) | 299 (32.9) | 355 (29.8) | 204 (26.1) | 219 (25.2) |

| Some college/vocational school | 304 (35.5) | 346 (38.0) | 466 (39.1) | 309 (39.6) | 304 (35.0) |

| Bachelor degree or higher | 179 (20.9) | 265 (29.1) | 372 (31.2) | 268 (34.3) | 346 (39.8) |

| Body mass index, No. (%) | |||||

| <25 kg/m2 | 395 (46.1) | 424 (46.6) | 568 (47.6) | 437 (56.0) | 532 (61.2) |

| 25 to <30 kg/m2 | 237 (27.7) | 266 (29.2) | 364 (30.5) | 214 (27.4) | 226 (26.0) |

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 225 (26.3) | 220 (24.2) | 261 (21.9) | 130 (16.6) | 111 (12.8) |

| Cigarette smoking status at baseline, No. (%) | |||||

| Never | 524 (61.1) | 550 (60.4) | 718 (60.2) | 425 (54.4) | 449 (51.7) |

| Former | 197 (23.0) | 241 (26.5) | 328 (27.5) | 236 (30.2) | 312 (35.9) |

| Current | 136 (15.9) | 119 (13.1) | 147 (12.3) | 120 (15.4) | 108 (12.4) |

| Alcohol consumption at baseline, No. (%) | |||||

| Never | 560 (65.3) | 530 (58.2) | 659 (55.2) | 383 (49.0) | 388 (44.6) |

| Former | 104 (12.1) | 122 (13.4) | 150 (12.6) | 104 (13.3) | 152 (17.5) |

| Current | 193 (22.5) | 258 (28.4) | 384 (32.2) | 294 (37.6) | 329 (37.9) |

| Postmenopausal hormone therapy at baseline, No. (%) | |||||

| Never | 607 (70.8) | 671 (73.7) | 830 (69.6) | 564 (72.2) | 640 (73.7) |

| Former | 246 (28.7) | 229 (25.2) | 347 (29.1) | 203 (26.0) | 214 (24.6) |

| Current | 4 (0.5) | 10 (1.1) | 16 (1.3) | 14 (1.8) | 15 (1.7) |

| Estrogen receptor status of first invasive BC, No. (%) | |||||

| Positivea | 519 (60.6) | 549 (60.3) | 726 (60.9) | 470 (60.2) | 500 (57.5) |

| Negative | 211 (24.6) | 196 (21.5) | 322 (27.0) | 196 (25.1) | 233 (26.8) |

| Missing | 127 (14.8) | 165 (18.1) | 145 (12.2) | 115 (14.7) | 136 (15.7) |

| Tumor stage at diagnosis of first invasive BC, No. (%) | |||||

| Stage 1 | 300 (35.0) | 327 (35.9) | 451 (37.8) | 305 (39.1) | 341 (39.2) |

| Stage 2 | 285 (33.3) | 317 (34.8) | 428 (35.9) | 255 (32.7) | 292 (33.6) |

| Stage 3-4 | 52 (6.1) | 50 (5.5) | 85 (7.1) | 62 (7.9) | 35 (4.0) |

| Unknown | 220 (25.7) | 216 (23.7) | 229 (19.2) | 159 (20.4) | 201 (23.1) |

| Chemotherapy for first invasive BC, No. (%) | |||||

| No | 281 (32.8) | 314 (34.5) | 387 (32.4) | 278 (35.6) | 294 (33.8) |

| Yes | 421 (49.1) | 476 (52.3) | 662 (55.5) | 400 (51.2) | 452 (52.0) |

| Unknown | 155 (18.1) | 120 (13.2) | 144 (12.1) | 103 (13.2) | 123 (14.2) |

| Radiation for first invasive BC, No. (%) | |||||

| No | 248 (28.9) | 266 (29.2) | 328 (27.5) | 201 (25.7) | 246 (28.3) |

| Yes | 455 (53.1) | 525 (57.7) | 724 (60.7) | 475 (60.8) | 499 (57.4) |

| Unknown | 154 (18.0) | 119 (13.1) | 141 (11.8) | 105 (13.4) | 124 (14.3) |

| Surgery for first invasive BC, No. (%) | |||||

| None | 28 (3.3) | 34 (3.7) | 34 (2.9) | 31 (4.0) | 28 (3.2) |

| Mastectomy | 359 (41.9) | 361 (39.7) | 490 (41.1) | 309 (39.6) | 325 (37.4) |

| Lumpectomy | 388 (45.3) | 465 (51.1) | 589 (49.4) | 396 (50.7) | 452 (52.0) |

| Unknown | 82 (9.6) | 50 (5.5) | 80 (6.7) | 45 (5.8) | 64 (7.4) |

| Number of first- and second-degree relatives with BC, No. (%) | |||||

| 0 | 406 (47.4) | 399 (43.9) | 560 (46.9) | 353 (45.2) | 380 (43.7) |

| 1 | 260 (30.3) | 280 (30.8) | 339 (28.4) | 226 (28.9) | 269 (31.0) |

| 2 | 116 (13.5) | 149 (16.4) | 184 (15.4) | 130 (16.7) | 139 (16.0) |

| ≥3 | 75 (8.8) | 82 (9.0) | 110 (9.2) | 72 (9.2) | 81 (9.3) |

| BRCA1 or BRCA2 PVs, No. (%) | |||||

| Nob | 790 (92.2) | 846 (93.0) | 1117 (93.6) | 709 (90.8) | 774 (89.1) |

| Yesc | 67 (7.8) | 64 (7.0) | 76 (6.4) | 72 (9.2) | 95 (10.9) |

| Remaining lifetime BC risk, mean (SD) | 17.3 (17.0) | 17.8 (16.9) | 17.1 (15.4) | 19.7 (19.3) | 21.6 (20.5) |

Includes 49 women categorized as borderline for estrogen receptor status. BC = breast cancer; GED = general education degree; MET = metabolic equivalents; PVs = pathogenic variants.

Includes 3137 women who tested negative for BRCA1 and BRCA2 PVs and 1099 women without a genetic test result.

Includes 204 women with a BRCA1 PV, 168 women with a BRCA2 PV, and 2 women with both a BRCA1 and BRCA2 PV.

Engaging in any RPA vs none was statistically significantly associated with 16.1% (95% CI = 2.4% to 27.9%) lower all-cause mortality, adjusting for covariates (Table 2). Engaging in only moderate RPA vs none statistically significantly lowered all-cause mortality by 17.8% (95% CI = 3.1% to 30.2%). Engaging in some RPA but less than recommended guidelines vs none lowered all-cause mortality by 17.2% (95% CI = 0.7% to 31.0%), and engaging in more RPA than the recommended guidelines vs none lowered all-cause mortality by 19.0% (95% CI = 2.4% to 32.7%). None of the other categorizations of RPA (compared with inactivity) were statistically significantly associated with all-cause mortality. RPA was not associated with risk of second BC events overall (Table 2) or in stratified analyses (data not shown).

Table 2.

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for associations of recreational physical activity and outcomes after first invasive breast cancer diagnosis in the Prospective Family Study Cohort

| Categorization of RPA | All-cause mortality (n = 4610) |

Second breast cancer event (n = 4356) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of women | No. of events | Person-years | HR (95% CI)a | No. of women | No. of events | Person-years | HR (95% CI)a | |

| RPA categorized as any vs none | ||||||||

| None | 750 | 226 | 7541 | 1.00 (Referent) | 720 | 67 | 6981 | 1.00 (Referent) |

| Any | 3860 | 986 | 43 331 | 0.84 (0.72 to 0.98) | 3636 | 406 | 38 609 | 1.05 (0.81 to 1.38) |

| RPA categorized by intensity level | ||||||||

| None | 750 | 226 | 7541 | 1.00 (Referent) | 720 | 67 | 6981 | 1.00 (Referent) |

| Moderate RPA only | 1737 | 446 | 20 025 | 0.82 (0.70 to 0.97) | 1646 | 193 | 18 007 | 1.17 (0.88 to 1.56) |

| Strenuous RPA | 2123b | 540 | 23 306 | 0.86 (0.73 to 1.02) | 1990c | 213 | 20 602 | 0.93 (0.69 to 1.24) |

| RPA categorized by national and international guidelinesd | ||||||||

| None | 750 | 226 | 7541 | 1.00 (Referent) | 720 | 67 | 6981 | 1.00 (Referent) |

| Some, but less than guidelinese | 1045 | 263 | 11 949 | 0.83 (0.69 to 0.99) | 992 | 108 | 10 764 | 1.12 (0.82 to 1.53) |

| Met guidelinesf | 1581 | 431 | 17 282 | 0.87 (0.73 to 1.03) | 1505 | 184 | 15 522 | 1.10 (0.82 to 1.47) |

| Exceeded guidelinesg | 1234 | 292 | 14 100 | 0.81 (0.67 to 0.98) | 1 to139 | 114 | 12 to323 | 0.92 (0.67 to 1.27) |

| RPA categorized by quintiles of total metabolic equivalents | ||||||||

| < 4 MET-hrs/wk | 857 | 250 | 8839 | 1.00 (Referent) | 821 | 79 | 8140 | 1.00 (Referent) |

| 4-11 MET-hrs/wk | 910 | 231 | 10 267 | 0.88 (0.73 to 1.06) | 865 | 92 | 9255 | 1.09 (0.81 to 1.49) |

| 12-20 MET-hrs/wk | 1193 | 325 | 12 959 | 0.92 (0.78 to 1.10) | 1133 | 135 | 11 653 | 1.05 (0.79 to 1.40) |

| 21-34 MET-hrs/wk | 781 | 210 | 8771 | 0.88 (0.73 to 1.07) | 738 | 84 | 7846 | 0.98 (0.71 to 1.34) |

| > 34 MET-hrs/wk | 869 | 196 | 10 036 | 0.83 (0.68 to 1.01) | 799 | 83 | 8696 | 0.94 (0.68 to 1.31) |

| Ptrendh across quintiles of MET-hrs/wk | .13 | .45 | ||||||

Hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval adjusted for age group at diagnosis (younger than 40, 40-49, 50-59, 60 years or older), study center (Australia, Canada, kConFab, New York, Northern California, Philadelphia, Utah), decade of birth year (<1950, 1950-1959, 1960-1969, ≥1970), race and ethnicity (Asian, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, other), education (high school graduate or less, some college, Bachelor degree or higher), cigarette smoking (never, former, current), alcohol consumption (never, former, current), postmenopausal hormone therapy use (never vs otherwise), body mass index (<25, 25 to <30, ≥30 kg/m2), stage at diagnosis (1, 2, 3 or 4, unknown), chemotherapy for first invasive breast cancer (yes vs otherwise) radiation treatment for first invasive breast cancer (yes vs otherwise), and surgery for first invasive breast cancer (mastectomy, lumpectomy, otherwise). CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; MET = metabolic equivalents; RPA = recreational physical activity.

Includes 106 women who engaged in only strenuous RPA and 2017 women who engaged in strenuous and moderate RPA.

Includes 100 women who engaged in only strenuous RPA and 1890 who engaged in strenuous and moderate RPA.

Based on the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (2018) and the World Health Organization’s 2020 Physical Activity Guidelines, which recommend adults engage in 150-300 minutes per week of moderate physical activity or 75-150 minutes per week of strenuous physical activity, or some combination.

Less than 150 minutes per week of moderate RPA and less than 75 minutes per week of strenuous RPA.

150-300 minutes per week of moderate RPA or 75-150 minutes per week of strenuous RPA.

>300 minutes per week of moderate or >150 minutes per week of strenuous RPA.

P value reported from 2-sided Wald test.

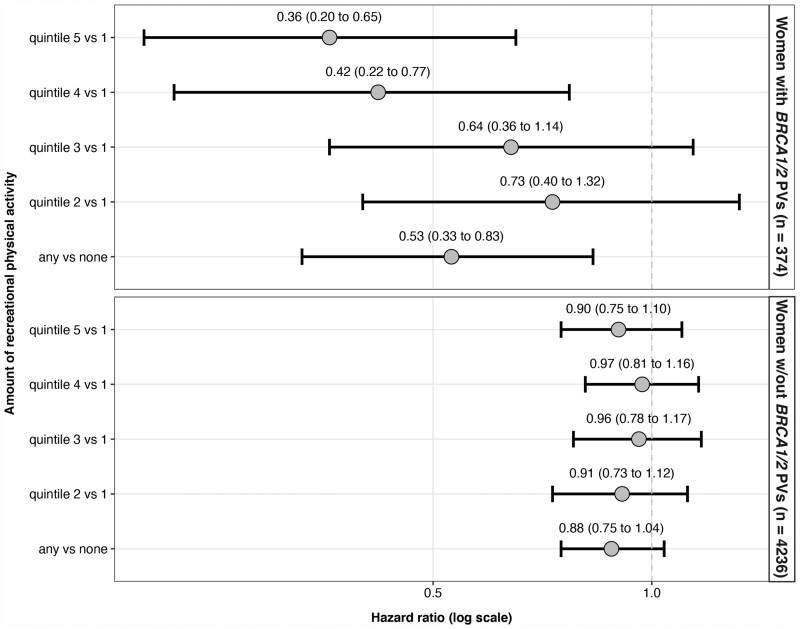

As shown in Figure 1, any RPA vs none was associated with 47.5% (95% CI = 17.4% to 66.6%) lower all-cause mortality in women with BRCA1/2 PVs and 11.8% (95% CI=-3.6% to 24.9%) lower all-cause mortality in women without BRCA1/2 PVs (RPA*BRCA1/2 multiplicative interaction P = .005). A statistically significant linear trend in lower all-cause mortality was seen across quintiles of RPA in women with BRCA1/2 PVs (Ptrend = .01) but not in women without BRCA1/2 PVs (Ptrend = .51). We also found statistical evidence of a positive additive interaction between RPA (any vs none) and BRCA1/2 PVs status (RERI = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.01 to 1.74).

Figure 1.

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association of recreational physical activity and all-cause mortality after first invasive breast cancer in women with and without BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants in the Prospective Family Study Cohort (n = 4610). Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (given within parentheses and depicted by error bars) are adjusted for age group at diagnosis (younger than 40, 40-49, 50-59, 60 years or older), study center (Australia, Canada, kConFab, New York, Northern California, Philadelphia, Utah), decade of birth year (<1950, 1950-1959, 1960-1969, ≥1970), race and ethnicity (Asian, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, other), education (high school graduate or less, some college, Bachelor degree or higher), cigarette smoking (never, former, current), alcohol consumption (never, former, current), postmenopausal hormone therapy use (never vs otherwise), body mass index (<25, 25 to <30, ≥30 kg/m2), stage at diagnosis (1, 2, 3 or 4, unknown), chemotherapy for first invasive breast cancer (yes vs otherwise), radiation treatment for first invasive breast cancer (yes vs otherwise), and surgery for first invasive breast cancer (mastectomy, lumpectomy, otherwise). Women without BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variants (PVs) include true negatives (n = 3137) and women without a genetic test result (n = 1099). The interaction term between recreational physical activity categorized as any vs none and BRCA1/2 PV status was statistically significant (2-sided Wald test P = .005). The interaction term between recreational physical activity categorized into quintiles of total metabolic equivalents hours per week (MET-hours/week) and BRCA1/2 PV status was also statistically significant (2-sided Wald test P = .007). CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio.

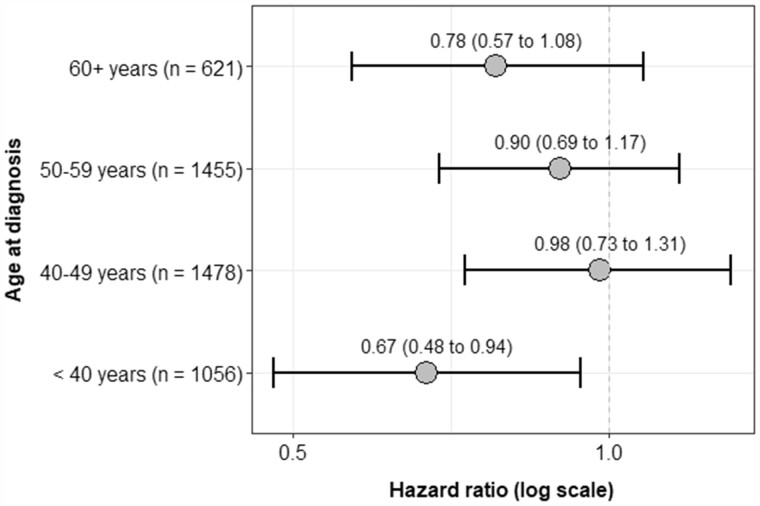

The RPA-mortality association was not modified on the multiplicative or additive scales by BMI, familial risk score, ER status, or stage at diagnosis, (P values > .05; see Supplementary Figure 1, available online). The association was also not modified on either scale by age group at diagnosis, although a statistically significant association between RPA (any vs none) and all-cause mortality was only found in women younger than age 40 years at diagnosis (hazard ratio = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.48 to 0.94; Figure 2). Results from sensitivity analyses were consistent with main findings, and associations did not differ by exposure window or cohort (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association of recreational physical activity, categorized as any vs none, and all-cause mortality after first invasive breast cancer by age group at diagnosis in the Prospective Family Study Cohort (n = 4610). Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (given within parentheses and depicted by error bars) are adjusted for study center (Australia, Canada, kConFab, New York, Northern California, Philadelphia, Utah), decade of birth year (<1950, 1950-1959, 1960-1969, ≥1970), race and ethnicity (Asian, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, other), education (high school graduate or less, some college, Bachelor degree or higher), cigarette smoking (never, former, current), alcohol consumption (never, former, current), postmenopausal hormone therapy use (never vs otherwise), body mass index (<25, 25 to <30, ≥30 kg/m2), stage at diagnosis (1, 2, 3 or 4, unknown), chemotherapy for first invasive breast cancer (yes vs otherwise), radiation treatment for first invasive breast cancer (yes vs otherwise), and surgery for first invasive breast cancer (mastectomy, lumpectomy, otherwise). The interaction term between recreational physical activity categorized as any vs none and age group at diagnosis was not statistically significant (2-sided Wald test P = .37). CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio.

Discussion

Using a prospective cohort enriched for women at higher-than-average familial risk of BC, we found that engaging in RPA around the time of first invasive BC diagnosis was associated with lower all-cause mortality. We found that even modest levels of RPA (eg, less than recommended guidelines) conferred some survival benefit compared with being inactive. These overall findings are consistent with previous studies of unenriched cohorts (10) and our previous BCFR analysis in which we excluded women with BRCA1/2 PVs and did not consider familial risk as a continuous measure (2). The reduction in mortality after BC associated with RPA is slightly lower in magnitude than the reduction in mortality associated with healthy dietary patterns [approximately 24% lower mortality (29)] or being nonobese [approximately 33% (30)] found in other studies.

We found that the association between RPA and all-cause mortality was stronger on both the multiplicative and additive scales in women with vs without BRCA1/2 PVs. In women with BRCA1/2 PVs, any RPA vs none lowered all-cause mortality by 47.5% on the relative scale and by 14.4% on the additive scale (comparing adjusted cumulative incidence curves after 10 years of follow-up). Women with BRCA1/2 PVs are often diagnosed with BC at a younger age and have different frequencies of certain histological and cell biological characteristics compared with sporadic breast tumors (11). When we stratified by age group at diagnosis, a statistically significant association between RPA and all-cause mortality was found in women diagnosed before age 40 years but not in the older age groups, suggesting that RPA is important for reducing mortality risk in women with early onset BC. However, more research is needed to determine if age differences explain BRCA1/2-specific findings.

Mechanisms through which RPA might improve survival after BC include regulation of body fat, glucose, insulin, and immune function (3,31). One hypothesis for the stronger association between RPA and all-cause mortality in women with vs without BRCA1/2 PVs is that RPA reduces mortality from other diseases that are more common in women with BRCA1/2 PVs, such as other cancers. Yet, findings were consistent when we excluded women diagnosed with other cancers. It is also possible that the differential relationship between RPA and all-cause mortality by PV status is explained by the fact that BRCA1 and BRCA2 have known roles in DNA repair mechanisms following double-stranded breaks (32). Thus, if DNA damage levels are modulated by RPA, such as through its impact on oxidative stress levels (33), it is plausible that RPA would disproportionately impact women with BRCA1/2 PVs. However, more work is needed to further understand the interplay between RPA and BRCA1/2 function.

RPA was not associated with second BC events in our analysis. By contrast, 2 population-based prospective studies, which ascertained second BC events through medical chart reviews, found a reduced risk of BC recurrence associated with higher levels of prediagnosis RPA (34,35). We were limited to self-reported BC events, which might be subject to undercounting, and the proportion of women with second BC events in our cohort (10.9%) was lower than the 2 previous population-based studies (11.4%-26.7%) (34,35). A study using nationally representative cancer registry data also reported a higher rate of second BC events (36.8% within 10 years) but only included women aged 65 years and older (36).

This prospective study has several strengths, including a large cohort enriched with women at higher-than-average BC risk, use of a continuous measure of familial risk, and stratification by BRCA1/2 PVs status. This study is limited by potential exposure misclassification because of self-reported data. However, exposure misclassification is likely to be nondifferential, given our prospective study design, and research suggests that recall bias is not likely to fully explain associations of RPA with BC (37). Further, although self-reported RPA may be overestimated (38), prior studies have validated the use of self-reported measures for rank ordering RPA levels within populations (39). Our analysis of physical activity was also limited in that nonrecreational types of activity (eg, occupational, household, transportation) were not considered. Additionally, 14.0% of the cohort reported their RPA for a time period that included both pre- and postdiagnosis, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions about the timing of RPA in relationship to BC outcomes. However, associations did not differ in sensitivity analyses stratified by exposure window or cohort (data not shown). Nevertheless, caution should be made when extrapolating study findings to clinical guidance on the exact amount of physical activity needed to reduce adverse outcomes. The lack of data on RPA after study enrollment, comorbidities, and cause of death are also limitations of this study, and it will be important for future studies to consider if RPA is associated with BC-specific mortality in women with BRCA1/2 PVs. We were limited by small numbers in some subgroups, which reduced statistical power to identify interactions. Further, because our study sample was restricted to women with BC, collider bias is possible if all common causes of BC and mortality were not accounted for in analyses. Yet, this type of bias usually moves risk estimates toward the null (40), suggesting that associations might be stronger than estimated.

In conclusion, this prospective study of an enriched cohort supports that RPA is associated with lower all-cause mortality after BC in women across the familial risk continuum. In particular, women with BRCA1/2 PVs might benefit from maintaining or increasing RPA, given that stronger associations were found on both the relative and absolute scales in these women.

Funding

The 6 sites of the Breast Cancer Family Registry were supported by grant U01 CA164920 from the USA National Cancer Institute. This work was also supported by grants to kConFab and the kConFab Follow-Up Study from Cancer Australia (grant numbers 809195, 1100868), the Australian National Breast Cancer Foundation (grant number IF 17 kConFab), the National Health and Medical Research Council (grant numbers 454508, 288704, 145684), the National Institute of Health USA (grant number 1R01CA159868), the Queensland Cancer Fund, the Cancer Councils of New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia, and the Cancer Foundation of Western Australia (grant numbers not applicable). KAP is a National Health and Medical Research Council Leadership Fellow (grant number 1195294).

Notes

Role of the funders: The study funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author disclosures: The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions: RDK and MBT: conceptualization and methodology. RDK: formal analysis, writing (original draft), visualization. MBT: supervision. EMJ, JAK, KAP, ILA, SSB, MBD, JLH, MBT: funding acquisition. YL: software. YL, SN, GG, PCW: data curation. All authors: writing (review & editing).

Acknowledgements: We thank the entire team of Breast Cancer Family Registry (BCFR) past and current investigators as well as the kConFab investigators. We also thank all the BCFR and kConFab research nurses and staff, the heads and staff of the Family Cancer Clinics, and the many families who contribute to the BCFR and kConFab for their contributions to this resource.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Keegan TH, Milne RL, Andrulis IL, et al. Past recreational physical activity, body size, and all-cause mortality following breast cancer diagnosis: results from the Breast Cancer Family Registry. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123(2):531–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sternfeld B, Weltzien E, Quesenberry CP, et al. Physical activity and risk of recurrence and mortality in breast cancer survivors: findings from the LACE study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(1):87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Friedenreich CM, Cust AE.. Physical activity and breast cancer risk: impact of timing, type and dose of activity and population subgroup effects. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42(8):636–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wu Y, Zhang D, Kang S.. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137(3):869–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clinton SK, Giovannucci EL, Hursting SD.. The World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research third expert report on diet, nutrition, physical activity, and cancer: impact and future directions. J Nutr. 2020;150(4):663–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Friedenreich CM, Stone CR, Cheung WY, et al. Physical activity and mortality in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020;4(1):pkz080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McTiernan A, Friedenreich CM, Katzmarzyk PT, et al. Physical activity in cancer prevention and survival: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(6):1252–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spei ME, Samoli E, Bravi F, et al. Physical activity in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis on overall and breast cancer survival. Breast. 2019;44:144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lahart IM, Metsios GS, Nevill AM, et al. Physical activity, risk of death and recurrence in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):635–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Klijn J, Meijers-Heijboer H.. Gene screening and prevention of hereditary breast cancer: a clinical view. Eur J Cancer Suppl. 2003;1(1):13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Terry MB, Phillips KA, Daly MB, et al. Cohort profile: the breast cancer prospective family study cohort (ProF-SC). Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(3):683–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hopper JL. Genetics for population and public health. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):8–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hopper JL, Dite GS, MacInnis RJ, et al. ; for the kConFab Investigators. Age-specific breast cancer risk by body mass index and familial risk: prospective family study cohort (ProF-SC). Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20(1):132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. MacInnis RJ, Knight JA, Chung WK, et al. Comparing five-year and lifetime risks of breast cancer in the prospective family study cohort. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(6):785–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Terry MB, Liao Y, Whittemore AS, et al. 10-year performance of four models of breast cancer risk: a validation study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(4):504–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hopper JL. Disease-specific prospective family study cohorts enriched for familial risk. Epidemiol Perspect Innov. 2011;8(1):2–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kehm RD, Genkinger JM, MacInnis RJ, et al. Recreational physical activity is associated with reduced breast cancer risk in adult women at high risk for breast cancer: a cohort study of women selected for familial and genetic risk. Cancer Res. 2020;80(1):116–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. John EM, Hopper JL, Beck JC, et al. ; for the Breast Cancer Family Registry. The Breast Cancer Family Registry: an infrastructure for cooperative multinational, interdisciplinary and translational studies of the genetic epidemiology of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6(4):R375–R389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mann GJ, Thorne H, Balleine RL, et al. ; for the Kathleen Cuningham Consortium for Research in Familial Breast Cancer. Analysis of cancer risk and BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation prevalence in the kConFab familial breast cancer resource. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8(1):R12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Phillips KA, Butow PN, Stewart AE, et al. ; for the kConFab Investigators. Predictors of participation in clinical and psychosocial follow-up of the kConFab breast cancer family cohort. Fam Cancer. 2005;4(2):105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ainsworth B, Haskell W, Herrmann S, et al. Compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(8):1575–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Antoniou A, Pharoah P, Smith P, et al. The BOADICEA model of genetic susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(8):1580–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Antoniou AC, Cunningham AP, Peto J, et al. The BOADICEA model of genetic susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancers: updates and extensions. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(8):1457–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1451–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Derks M, Bastiaannet E, van de Water W, et al. Impact of age on breast cancer mortality and competing causes of death at 10 years follow-up in the adjuvant TEAM trial. Eur J Cancer. 2018;99:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Howlader N, Mariotto AB, Woloshin S, et al. Providing clinicians and patients with actual prognosis: cancer in the context of competing causes of death. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2014;2014(49):255–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hou R, Wei J, Hu Y, et al. Healthy dietary patterns and risk and survival of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2019;30(8):835–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Protani M, Coory M, Martin JH.. Effect of obesity on survival of women with breast cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123(3):627–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hoffman‐Goetz L, Apter D, Demark‐Wahnefried W, et al. Possible mechanisms mediating an association between physical activity and breast cancer. Cancer. 1998;83(S3):621–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu Y, West SC.. Distinct functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in double-strand break repair. Breast Cancer Res. 2001;4(1):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. de Boer MC, Wörner EA, Verlaan D, et al. The mechanisms and effects of physical activity on breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2017;17(4):272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Friedenreich CM, Gregory J, Kopciuk KA, et al. Prospective cohort study of lifetime physical activity and breast cancer survival. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(8):1954–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schmidt ME, Chang‐Claude J, Vrieling A, et al. Association of pre‐diagnosis physical activity with recurrence and mortality among women with breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(6):1431–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cheng L, Swartz MD, Zhao H, et al. Hazard of recurrence among women after primary breast cancer treatment—a 10-year follow-up using data from SEER-Medicare. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(5):800–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maruti SS, Willett WC, Feskanich D, et al. Physical activity and premenopausal breast cancer: an examination of recall and selection bias. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(5):549–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, et al. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wolf AM, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23(5):991–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cespedes Feliciano EM, Prentice RL, Aragaki AK, et al. Methodological considerations for disentangling a risk factor’s influence on disease incidence versus postdiagnosis survival: the example of obesity and breast and colorectal cancer mortality in the Women’s Health Initiative. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(11):2281–2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.