Abstract

Purpose: GATA3 is a transcription factor essential for mammary luminal epithelial cell differentiation. Expression of GATA3 is absent or significantly reduced in basal-like breast cancers. Gata3 loss-of-function impairs cell proliferation, making it difficult to investigate the role of GATA3 deficiency in vivo. We previously demonstrated that CDK inhibitor p18INK4c (p18) is a downstream target of GATA3 and restrains mammary epithelial cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Whether and how loss-of-function of GATA3 results in basal-like breast cancers remains elusive.

Methods: We generated mutant mouse strains with heterozygous germline deletion of Gata3 in p18 deficient backgrounds and developed a Gata3 depleted mammary tumor model system to determine the role of Gata3 loss in controlling cell proliferation and aberrant differentiation in mammary tumor development and progression.

Results: Haploid loss of Gata3 reduced mammary epithelial cell proliferation with induction of p18, impaired luminal differentiation, and promoted basal differentiation in mammary glands. p18 deficiency induced luminal type mammary tumors and rescued the proliferative defect caused by haploid loss of Gata3. Haploid loss of Gata3 accelerated p18 deficient mammary tumor development and changed the properties of these tumors, resulting in their malignant and luminal-to-basal transformation. Expression of Gata3 negatively correlated with basal differentiation markers in MMTV-PyMT mammary tumor cells. Depletion of Gata3 in luminal tumor cells also reduced cell proliferation with induction of p18 and promoted basal differentiation. We confirmed that expression of GATA3 and basal markers are inversely correlated in human basal-like breast cancers.

Conclusions: This study provides the first genetic evidence demonstrating that loss-of-function of GATA3 directly induces basal-like breast cancer. Our finding suggests that basal-like breast cancer may also originate from luminal type cancer.

Keywords: Gata3 loss, p18INK4c, mammary tumor, basal differentiation

Introduction

Aberrant cell differentiation has long been linked to tumorigenesis and poor differentiation, and is strongly associated with worse cancer prognosis. The molecular mechanism of how altered differentiation is linked to tumorigenesis, particularly tumor development in solid organs, is poorly understood. This study uses a well-defined in vivo cell differentiation system, the mammary gland, to determine how altered differentiation contributes to breast cancer.

Mammary epithelia are mainly composed of luminal and basal cells that are maintained by luminal and basal progenitors, respectively, and are believed to originate from a common mammary stem cell (MaSC) 1-5. Although little is known about the mechanisms controlling basal cell lineage differentiation, luminal cell fate determination is mainly controlled by a network of transcription factors including GATA3, ELF5, FOXA1, STAT3, and STAT5A, and deficiency or reduction of these transcription factors impairs luminal cell differentiation and mammary gland development 1, 2, 6. Clinically, breast cancer comprises three main subtypes including human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) positive, hormone receptor [estrogen receptor (ER) and/or progesterone receptor (PGR)]-positive, and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) which lacks expression of ER, PGR, and HER2 7, 8. Molecularly, breast cancer is categorized into five intrinsic subtypes: basal-like (BL), HER2-enriched, luminal A, luminal B, and normal-like, each with unique biological and prognostic features 8-10. Basal-like breast cancer (BLBC) accounts for approximately 70% of TNBCs and is a leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide. The high mortality rate of BLBCs can be attributed to the aggressive, metastatic capacity of these tumors and the limited number of effective therapeutic options 7, 8. BLBCs are heterogeneous and contain several distinct cell types including cells that express luminal biomarkers 11-13. It was recently suggested that BRCA1 deficient BLBCs may originate from luminal progenitors 14-17. Yet, two elusive questions remain: how BLBCs develop and whether loss-of-function of transcription factors essential for luminal cell differentiation contributes to basal differentiation during mammary tumorigenesis and progression.

GATA3 has dual roles in both normal and tumor development. It plays a critical role in the development of the nervous system, mammary gland, parathyroid glands, kidney, inner ear, skin, and lymphoid cell lineage 18-23. Germline mutations of GATA3 in humans are associated with the congenital hypoparathyroidism-deafness-renal disease (HDR) syndrome 24, 25. Somatic mutations of GATA3 have been detected in ~15% of breast cancers and is one of the top three genes mutated in >10% of all breast cancers. Interestingly, most breast cancers with GATA3 mutation are luminal type cancers that retain GATA3 expression 8, 26, and high GATA3 expression predicts better survival 1, 27. However, GATA3 is often silenced by DNA methylation 28, 29 and its expression is lost or significantly reduced in BLBCs 8, 27, 30, 31. It has not been determined if loss-of-function of GATA3 induces BLBCs.

Gata3 is required for mammary luminal epithelial differentiation and mammary gland development 19, 20. Germline or epithelium-specific deletion of Gata3 in mice causes early lethality or severe growth defects 18-20, 32, making it difficult to study its loss-of-function in mammary tumorigenesis, also suggesting that overcoming growth defects is a necessary step for the development of tumors initiated by GATA3 reduction or loss. Overexpression of GATA3 suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in cancer cell lines 33, 34 and loss of Gata3 in transgenic mice stimulates mammary luminal tumor progression 35, 36. However, due to the inability to tolerate Gata3 loss in differentiated luminal tumors in transgenic mice35, it remains elusive whether and how Gata3 loss-of-function alters the fate of luminal cells and induces aberrant differentiation, stimulating mammary tumor progression.

Not until recently has the function of GATA3 in regulating cell proliferation been reported. Loss of Gata3 results in impaired cell cycle entry and proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) 37, though the discrepant finding that deletion of Gata3 enhances self-renewal of HSCs without affecting the cell cycle has also been observed 38. We, and others, demonstrated that loss of Gata3 impairs T cell proliferation 39-41 and reduces the proliferation of mammary luminal epithelial cells 27 and T cells 40, 41 with induction of cell cycle inhibitor, p18Ink4c (p18). p18 is a member of the INK4 family that inhibits CDK4 and CDK6, whose activation by mitogen-induced D-type cyclins lead to phosphorylation and functional inactivation of RB, p107, and p130. Loss-of-function of the INK4-cyclin D/CDK4/6-RB pathway is a common event in variety of cancers including breast cancer 42 and p18 expression is significantly lower in human luminal breast cancers 8, consistent with our finding that loss of p18 in mice induces luminal mammary tumors 27. Importantly, depletion of both Rb and p107 in mice also results in luminal type tumors 43. These observations suggest a role of the p18-Rb pathway in controlling luminal tumorigenesis.

Prompted by the finding that p18 is a downstream target of GATA3 and restrains mammary epithelial cell (MEC) proliferation and tumorigenesis 27, we hypothesize that p18 deficiency may rescue GATA3 deficiency impaired MEC proliferation, allowing us to determine the role of Gata3 loss in controlling cell fate during mammary tumorigenesis. In the present study, we generated mutant mouse strains with heterozygous germline deletion of Gata3 in p18 deficient backgrounds and developed a Gata3 depleted mouse mammary tumor model system to determine the function and mechanism of Gata3 loss in controlling cell proliferation and aberrant differentiation in mammary tumor development and progression.

Methods

Mice, histopathology, and immunohistochemistry

The generation of p18-/-, p18+/-, Gata3+/-, p18+/-;Gata3+/-, and p18-/-;Gata3+/- mice was previously described 17, 27, 41, 44. NOD-Prkdcem26Cd52Il2rgem26Cd22/Nju (NCG) and FVB/NJGpt-Tg(MMTV-PyMT)/Gpt were purchased from GemPharmatech (Nanjing, China). The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Miami and Shenzhen University approved all animal procedures. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry (IHC) were performed as previously described 17, 27, 44. The primary antibodies used were: E-cadherin (E-Cad) (BD Biosciences), Ck5 (Covance), Ck8 (American Research Products), Ck14 (Thermal Scientific), eGFP (GeneTex), GATA3 (Santa Cruz), SMA (Cell Signaling), and Ki67 (Abcam). Immunocomplexes were detected using the Vectastain ABC alkaline phosphatase kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Vector Laboratories), or using FITC- or rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch). IHC results were quantified using H-score as previously described 45, 46.

Normal mammary and tumor cell preparation, FACS analysis, colony-formation assay, cell culture, and knockdown of GATA3

Tumor-free mammary glands were isolated from mice at the indicated ages and genotypes, the tissue was processed, mammary cell suspensions were prepared, and FACS analysis and colony-formation assays were performed as previously described 3, 5, 27. Mammary tumors were dissected from female mice and tumor cell suspensions were prepared as previously described 17, 27, 44. Primary mammary tumor cells isolated from female MMTV-PYMT mice were cultured in either MEC medium [10% FBS (Gibco), 10 ng/ml EGF, 1 μg/ml hydrocortisone] or MM+ medium [2% FCS (Gibco), 1% BSA]. T47D cells were cultured per ATCC recommendations. For knockdown of Gata3 in MMTV-PYMT tumor cells, cells were infected with psi-LVRU6GP-control, psi-LVRU6GP-Gata3-a, or psi-LVRU6GP-Gata3-c (GeneCopoeia, Guangzhou, China), then selected with puromycin. eGFP positive cells were the cells successfully infected with psi-LVRU6GP virus. For knockdown of GATA3 in human tumor cells, cells were infected with pGIPZ-empty, pGIPZ-shGATA3-E9, and pGIPZ-shGATA3-A12 as previously described 44.

Transplantation model of mammary tumors

For the transplantation of primary MMTV-PyMT mammary tumor cells,1 x 106 cells infected with psi-LVRU6GP-control or psi-LVRU6GP-Gata3-c and selected with puromycin were inoculated into the left and right inguinal mammary fat pads (MFPs) of 6-week-old female NCG mice, respectively. Eight weeks after transplantation, animals were euthanized and mammary tumors were dissected for histopathological, immunohistochemical, and biochemical analyses. For the transplantation of primary p18mt (p18+/- and p18-/- ) and p18mt;Gata3+/- (p18+/-;Gata3+/- and p18-/-;Gata3+/- ) mammary tumor cells, cells were inoculated into the left and right inguinal MFPs of female NCG mice, respectively, along with subcutaneous implantation of estrogen pellets. Eight weeks after transplantation, animals were euthanized and tumors were analyzed by histopathology and immunohistochemistry.

Western blot and qRT-PCR

Tissue and cell lysates were prepared as previously reported 44. Primary antibodies used were as follows: HSP90, GAPDH (Ambion), E-Cad (Cell Signaling), GATA3 (HG3-31, Santa Cruz). For qRT-PCR, total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol and cDNA was generated using the Omniscript RT Kit (Qiagen). qRT-PCR was performed as reported 44. Primers used are listed in Table S1.

Meta-analysis of gene expression data sets

The correlation of GATA3 mRNA and protein expression with molecular subtypes or major subtypes was analyzed in TCGA or in Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) breast cancer samples 47, 48. The human breast cancer gene expression miner v4.6 dataset with 11,359 samples (http://bcgenex.ico.unicancer.fr/BC-GEM/GEM-requete.php) 48 was analyzed for correlation of expression of GATA3 with genes associated with basal differentiation.

Statistical analysis

The survival rate was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Mantel-Cox log-rank tests were applied to compare the survival difference and obtained p values. All data are presented as the mean ±SD for at least three repeated individual experiments for each group. Quantitative results were analyzed by two-tailed Student's t-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

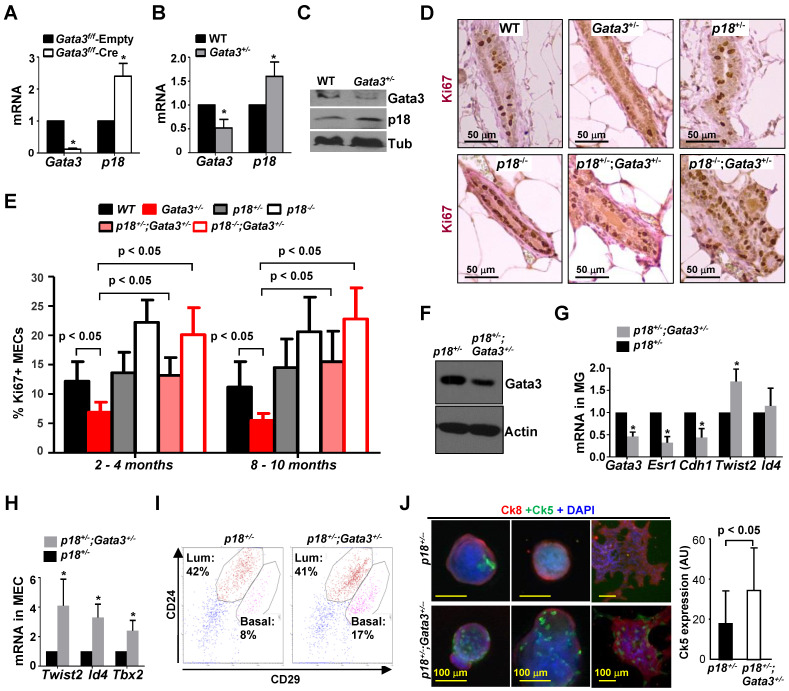

Deficiency of Gata3 reduces MEC proliferation with induction of p18

We previously demonstrated that deletion of Gata3 in mouse mammary gland in vivo promotes the expression of p18 27. To confirm the role of Gata3 in regulating p18 in MECs, we infected Gata3f/f MECs with pMX-Cre and found that deletion of Gata3, as expected, drastically enhanced p18 expression (Figure 1A). We previously detected expression of Gata3 in both luminal and MaSC-enriched basal epithelial cells, though GATA3 levels in the former is more abundant than in the latter. However, Gata3 is hardly detectable in stromal cells 27, suggesting it may function in both luminal and MaSC-enriched basal cells. To determine the effect of Gata3 deficiency in regulating all mammary cell lineages in an unbiased manner, we generated heterozygous germline Gata3+/- mutant mice by crossing Gata3f/+ mice with BALB/c-CMV-cre mice, a germline “Cre-deleter” strain, as we previously described 41. We confirmed reduced Gata3 mRNA and protein levels in Gata3+/- mammary glands as well as in thymocytes and splenocytes 41. We detected increased p18 expression in Gata3+/- mammary glands when compared with WT counterparts (Figure 1B, C, Figure S1A). MEC proliferation, as evidenced by Ki67 staining, in Gata3+/- mice relative to WT animals was significantly reduced (6.9% ± 1.7% vs. 12.2% ± 3.3%, p < 0.05 at 2-4 months of age, 5.5% ± 1.2% vs. 11.2% ± 4.3%, p < 0.05 at 8-10 months of age; Figure 1D, E, and Figure S1B). Consistent with our previous finding derived from Gata3f/f;WAP-cre mice 27, these results indicate that haploid loss of Gata3 caused by heterozygous germline deletion of Gata3 also reduces MEC proliferation that is associated with induction of p18, further confirming that p18 is a downstream target of Gata3 in restraining MEC proliferation.

Figure 1.

Gata3 deficiency promotes basal differentiation and reduces proliferation in MECs, and p18 deficiency rescues proliferative defects caused by Gata3 heterozygosity. (A) MECs isolated from 3-month-old female Gata3f/f mice were infected with pMX-Cre (Cre) and pMX-Empty (Empty) then selected with puromycin for 3 days. mRNA was extracted and analyzed. (B, C) RNA and protein lysates extracted from WT and Gata3+/- MECs were analyzed by qRT-PCR (B) and western blot (C). Data in (A) and (B) represent the mean ± SD from triplicates of two independent primary cell lines of each genotype. The asterisk (*) denotes a statistical significance between WT and Gata3+/- or Cre and Empty samples as determined by T-test. (D) Representative mammary tissues from 8-10-month-old mice were analyzed by immunohistochemistry with Ki67. (E) The percentages of Ki67-positive cells were calculated from cells situated in clear duct/gland structures from 2-4 month and 8-10-month-old mice, respectively. Results represent the mean ± SD of three animals per group. (F-H) Tumor-free mammary glands (MG, F, G) and mammary epithelial cells (MEC, H) from 2-4-month-old mice were analyzed by western blot (F) and qRT-PCR (G, H). Data are expressed as the mean ± SD from triplicates of each of three separate mice (G) or of four different lines of MECs (H). The asterisk (*) denotes a statistical significance from p18+/-;Gata3+/- and p18+/- samples determined by T-test. (I) Representative mammary cells from 2-4-month-old mice were analyzed by flow cytometry. (J) Freshly isolated mammary cells from 2-4-month-old mice were cultured in Matrigel-coated 24 well plates. Nine days after culture, the colonies were immunostained with Ck8 and Ck5 (left panel). Ck5 expression in colonies was quantified by ImageJ software (right panel). The assay was performed in triplicate for each animal. The bar graphs represent the mean ± SD of two animals per group.

p18 deficiency rescues proliferative defects of Gata3 deficient MECs and haploid loss of Gata3 promotes basal differentiation

Identification of p18 as a downstream target of Gata3 in restraining mammary epithelial cell proliferation prompted us to hypothesize that p18 deficiency may rescue mammary growth defects caused by Gata3 deletion, allowing us to investigate the role of Gata3 loss-of-function in controlling cell fate during mammary tumor development and progression. We crossed p18-/- mice with Gata3 mutants and generated p18-/-;Gata3+/- and p18+/-;Gata3+/- mice in Balb/c-B6 mixed background. We found that Ki67 positive MECs from p18-/-;Gata3+/- mice were comparable with those from p18-/- mice (20.1% ± 4.6% vs. 22.2% ± 3.8% at 2-4 months, 22.8% ± 5.3% vs. 20.6% ± 5.9% at 8-10 months), and p18+/-;Gata3+/- comparable with p18+/- (13.2% ± 3.0% vs. 13.6% ± 3.5% at 2-4 months, 15.5% ± 5.2% vs. 14.5% ± 4.9% at 8-10 months). However, the number of Ki67 positive MECs in both p18-/-;Gata3+/- and p18+/-;Gata3+/- mice were significantly more than in Gata3+/- animals (20.1% ± 4.6% in p18-/-;Gata3+/- and 13.2% ± 3.0% in p18+/-;Gata3+/- vs. 6.9% ± 1.7% in Gata3+/- at 2-4 months, 22.8% ± 5.3% in p18-/-;Gata3+/- and 15.5% ± 5.2% in p18+/-;Gata3+/- vs. 5.5% ± 1.2% in Gata3+/- at 8-10 months. (Figure 1D, E, and Figure S1A). These results suggest that haploid or complete loss of p18 rescues the proliferative defect induced by haploid loss of Gata3 in MECs, and p18 deficiency is required for Gata3 deficient MEC proliferation. We then confirmed decreased Gata3 expression in p18+/-;Gata3+/- mammary tissues relative to p18+/- tissues, and determined the differentiation changes in Gata3 deficient MECs (Fig. 1F, G). We found that the expression of Esr1 (encoding ERα) and Cdh1 - genes associated with luminal differentiation - in Gata3+/- and p18+/-;Gata3+/- mammary glands was reduced relative to WT and p18+/- glands (Fig. 1G and data not shown), confirming that Gata3 deficiency impairs luminal differentiation 19, 20. Notably, the expression of Twist2, Id4 and Tbx2 - transcription factors associated with basal differentiation 44, 49, 50 - was enhanced in Gata3+/- and p18+/-;Gata3+/- mammary glands and MECs relative to WT and p18+/- counterparts (Fig. 1G, H, and data not shown). We did not detect significant changes in luminal progenitor (LP) -enriched luminal populations in p18+/-;Gata3+/- MECs by FACS analysis (CD24+CD29low, Fig. 1I) compared to p18+/- MECs, suggesting that haploid loss of Gata3 is insufficient to impact this population. However, MaSC-enriched basal populations in p18+/-;Gata3+/- MECs were clearly increased (CD24+CD29high, Fig. 1I) relative to p18+/- MECs. We performed colony formation assays and found that p18+/-;Gata3+/- MECs produced significantly more basal colonies than p18+/- (Fig. 1J, Figure S1C), further supporting a function of Gata3 in suppressing basal colony formation. In sum, these results indicate that haploid loss of Gata3 promotes basal differentiation in MECs.

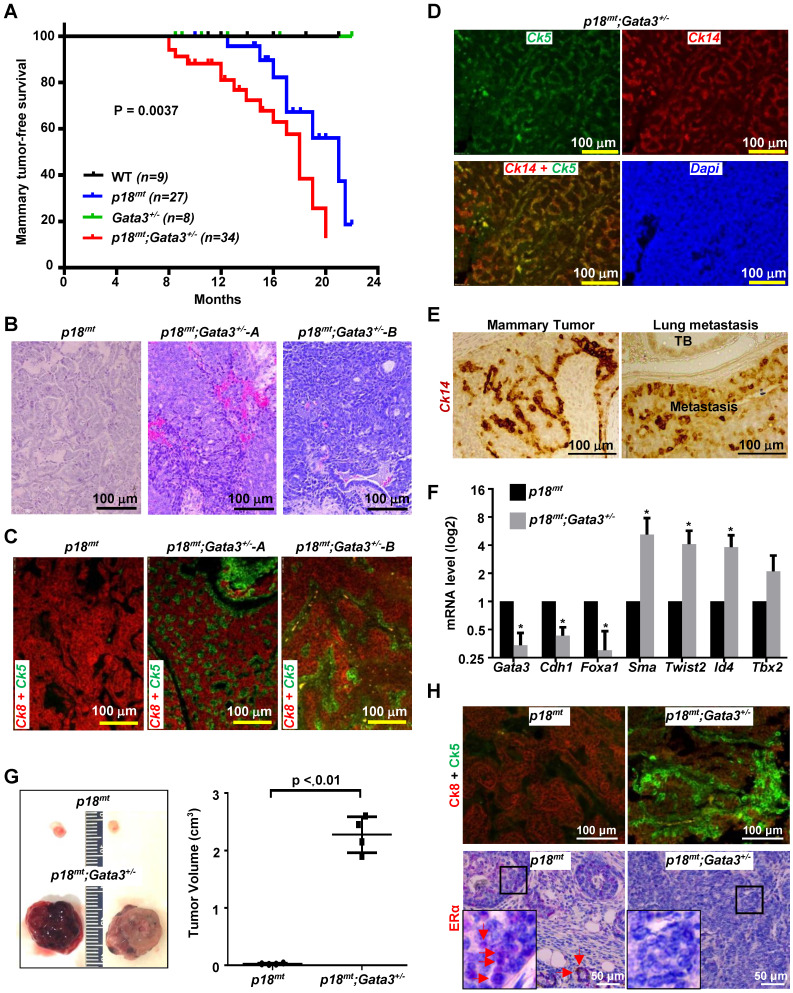

Haploid loss of Gata3 in p18 deficient mice convert luminal type tumors into basal-like tumors

We followed tumor development in WT and mutant mice with Balb/c-B6 mixed background. Because both p18+/- and p18-/- mice spontaneously develop luminal type mammary tumors 17, 27, and either haploid or complete loss of p18 rescues the proliferative defect of Gata3+/- MECs, we combined p18-/- and p18+/- mice as the p18mt group, and p18-/-;Gata3+/- and p18+/-;Gata3+/- mice as the p18mt;Gata3+/- group. Starting from as early as 8 months, p18mt;Gata3+/- mice (n = 34) developed mammary tumors whereas p18mt mice (n = 27) developed mammary tumors after 12.5 months. However, no WT (n = 9) nor Gata3+/- (n = 8) mice did within the same time period. The mammary tumor-free survival was reduced from a mean age of 21 months in p18mt mice to 18 months in p18mt;Gata3+/- mice (Figure 2A). These results demonstrate that overcoming growth defects, e.g., deficiency of p18, is required for Gata3 deficient MEC transformation and tumor development and that haploid loss of Gata3 in p18 deficient mice accelerates mammary tumorigenesis.

Figure 2.

Gata3 heterozygosity in p18 deficient mice induces basal-like mammary tumors. (A) Mammary tumor-free survival of mice in Balb/c-B6 mixed background. Mammary tumor-free median survival was 18 months in p18mt;Gata3+/- mice and 21 months in p18mt mice. The p18mt mouse group includes eight p18+/- and nineteen p18-/- mice, and the p18mt;Gata3+/- mouse group includes ten p18+/-;Gata3+/- and twenty-four p18-/-;Gata3+/- mice. (B-D) Representative H&E (B), and IF staining (C, D) of primary mammary tumors developed in mice with the indicated genotypes. (E) A representative p18mt;Gata3+/- spontaneous mammary tumor and lung metastatic lesion were analyzed by IHC with an antibody against Ck14. TB, Terminal Bronchiole. (F) RNA extracted from representative mammary tumors of the indicated genotype were analyzed. Results represent the mean ± SD of three tumors from individual animal per group. The asterisk (*) denotes a statistical significance from p18mt;Gata3+/- and p18mt samples determined by T-test. (G) Primary p18mt;Gata3+/- (5 x 105) and p18mt (5 x 106) mammary tumor cells were transplanted into the left and right inguinal MFPs of female NCG mice, respectively. Gross appearance and volume of mammary tumors regenerated in 8 weeks were analyzed. Data are represented as mean ± SD for tumors in each group (n = 4). (H) Mammary tumors formed by transplantation of p18mt;Gata3+/- and p18mt tumor cells in (G) were immunostained with antibodies against Ck5, Ck8, and ERα. The boxed areas were enlarged in the insets. Representative ERα-positive tumor cells and luminal epithelial cells in tumor-free glands are indicated by red arrows. Note that ERα-positive cells were mainly detected in p18mt tumors, but barely observed in p18mt;Gata3+/- tumors whereas Ck5-positive cells were mainly detected in p18mt;Gata3+/- tumors and hardly found in p18mt tumors.

Further characterization of mammary tumors revealed that 75% (n = 8) of p18mt mammary tumors were, as we previously reported 27, well-differentiated, ER and Ck8 positive, luminal type tumors (Table 1, Figure 2B-E). On the other hand, 82% (n = 17) of p18mt;Gata3+/- mammary tumors were highly heterogeneous, poorly-differentiated, ER negative, Ck5, Ck14 or SMA positive basal-like tumors (Table 1, Figure 2B-E). Relative to p18mt mammary tumors, p18mt;Gata3+/- tumors exhibited reduced expression of genes associated with luminal differentiation and enhanced expression of genes associated with basal differentiation (Figure 2F). Importantly, 29% (5 of 17) of p18mt;Gata3+/- and none (0 of 8) of p18mt mammary tumors metastasized to the lung, and all lung metastases were positive for mammary basal marker, Ck14 (Fig. 2E). These data indicate that haploid loss of Gata3 by heterozygous germline deletion of Gata3, although insufficient to induce mammary tumors alone, significantly changes the properties of mammary tumors induced by p18 deficiency, resulting in their malignant and luminal-to-basal-like transformation.

Table 1.

Spontaneous mammary tumor development in p18 and Gata3 mutant mice a

| Genotype | Tumor | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mammary tumor | Luminal Marker+ tumor d | Basal Marker+ tumor e | |

| WT | 0/9 | ||

| p18mt b | 8/27 (30%) | 6/8 (75%) | 2/8 (25%) |

| Gata3 +/- | 0/8 | ||

| p18mt;Gata3+/- c | 17/34 (50%)f | 3/17 (18%)g | 14/17 (82%)g, h |

a All mice were in Balb/c-B6 mixed background and were at 8-22 months of age.

b This group contains eight p18+/- and nineteen p18-/- mice.

c This group contains ten p18+/-;Gata3+/- and twenty four p18-/-;Gata3+/- mice.

d ER was detected in >2% tumor cells and Ck8 or E-Cad were detected in >50% tumor cells by IHC or IF.

e At least one of the basal markers (Ck5, Ck14, and Sma) was positively detected in >2% tumor cells by IHC or IF, as we previously reported (Bai, Oncogene, 2013; Cancer Res., 2014).

f No significance from p18mt;Gata3+/- and p18mt tumors by a two-tailed Fisher's exact test (p=0.124).

g Significance from p18mt;Gata3+/- and p18mt tumors by a two-tailed Fisher's exact test (p=0.010).

h Five mammary tumors metastasized to lung and/or liver.

We transplanted primary tumor cells into MFPs of mice and found that all mice that received 5 x 106 p18mt tumor cell transplants produced small tumors (26 ± 11 mm3 in size) in 8 weeks. Regenerated p18mt mammary tumors, like primary p18mt tumors, were well differentiated, positive for Ck8 and ERα, and negative or nearly undetectable for Ck5 and Ck14. In the same time period, all mice that received 5 x 105 p18mt;Gata3+/- tumor cell transplants, 1/10 the number of cells in comparison with p18mt transplants, developed large mammary tumors (2,275 ± 312 mm3). Pathological and IHC analysis revealed that, like primary p18mt;Gata3+/- mammary tumors, regenerated p18mt;Gata3+/- mammary tumors were poorly differentiated, positive for Ck5 and Ck14, and negative for ERα. (Figure 2G, H, and data not shown). These results confirm that in mammary tumor cells, Gata3 deficiency not only enhances the potential for tumor initiation but also promotes luminal-to-basal differentiation.

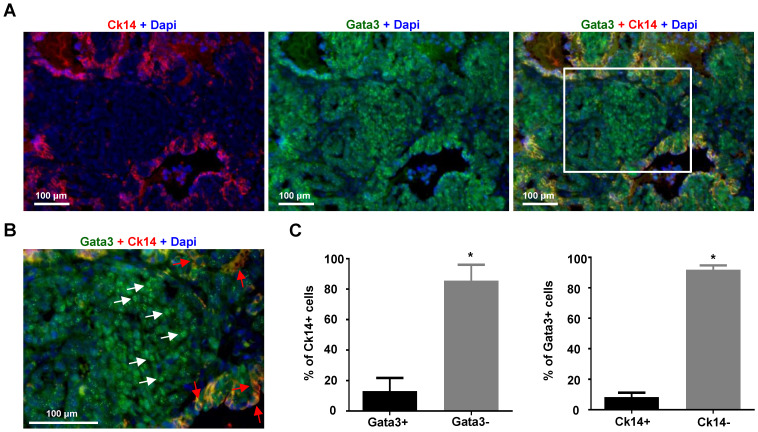

Expression of Gata3 negatively correlates with basal differentiation markers in mammary tumor cells

To determine whether loss of expression of GATA3 is associated with basal differentiation in established mammary tumors, we took advantage of MMTV-PyMT mice which develop spontaneous mammary tumors that have been well characterized as luminal B type tumors with a small number of Ck14 positive basal cells 35, 49, 51, 52. We carefully analyzed MMTV-PyMT mammary tumors which developed in 8-14 weeks. We found that ~86% of Ck14 positive cells did not express nuclear GATA3 and only ~13% of Ck14 positive cells co-expressed Gata3 (Figure 3A-C). Consistently, ~92% of Gata3 positive cells were negative for Ck14 and ~8% Gata3 positive cells were Ck14 positive. Importantly, in nearly all Ck14 and Gata3 double positive cells, Gata3 lost its nuclear localization, indicative of loss of Gata3 transactivation activity (Figure 3B, C). These results suggest that expression of Gata3 is negatively correlated with the basal marker CK14 in mammary tumor cells.

Figure 3.

The expression of Gata3 is negatively correlated with Ck14 in MMTV-PyMT mammary tumor cells. (A) Representative immunofluorescent staining of primary MMTV-PyMT mammary tumors with antibodies against Gata3 and Ck14. (B) Enlarged view of the boxed area in (A). Gata3 (white arrows) and Ck14 (red arrows) positive cells are indicated. (C) Quantification of Gata3 and Ck14 positive cells. The percentages of Ck14+ or Ck14- and Gata3+ or Gata3- cells were calculated from Gata3+Dapi+ and Ck14+Dapi+ cells, respectively. The results represent the mean ± SD of three individual tumors. At least 500 Ck14+ and Gata3+ cells were counted for each tumor. The asterisk (*) denotes a statistical significance from two group samples determined by T-test.

Generation of a Gata3 positive luminal type tumor model system

Due to slow proliferation in vitro, terminal differentiation status in nature (see below), as well as long latency for tumor initiation and exogenous estrogen dependent tumor growth in vivo, widely used human luminal type breast cancer cell lines such as MCF7 and T47D are not appropriate for investigating luminal tumor cell reprogramming in tumorigenesis and progression. To build a murine model system for investigating the role of Gata3 in controlling basal differentiation in luminal tumor cells, we screened 19 spontaneous mammary tumors developed in PyMT mice by western blot and IHC. We noticed that the tumors expressed distinct levels of Gata3 (Figure S2A). We chose 10 individual tumors with various levels of Gata3 and cultured them for further characterization. We found that after two weeks in culture, more than 90% of cells derived from tumors with high levels of Gata3 (e.g., B tumor cell line) belonged to a CD24+CD29low population in two different culture media whereas cells derived from tumors with low levels of Gata3 (e.g., C tumor cell line) contained a CD24-CD29low population in FBS high medium (MEC medium) or a mixture of CD24-CD29low and CD24+CD29low populations in FBS low medium (MM+ medium). After 6 weeks of culture in either FBS high or low medium, more than 90% of cells with high levels of GATA3 retained their CD24+CD29low feature, however, nearly all cells with low levels of Gata3 were CD24-CD29low (Figure S2B). These results suggest that in our cell culture system, primary tumor cells with high levels of Gata3 maintained their CD24+CD29low feature which is, as previously reported 3, 27, 53, a characteristic of luminal tumor cells by FACS analysis. Importantly, this CD24+CD29low feature is a typical characteristic of primary and regenerated MMTV-PyMT mammary tumor cells 35. We confirmed that after long term culture (at least 6 months), tumor cells derived from cells with high levels of Gata3 maintained their expression of Gata3 and E-Cad (encoded by Cdh1) (Figure S2C, and data not shown). We then transplanted these tumor cells (e.g., B tumor cell line) into MFPs of NCG mice. We confirmed that the newly regenerated tumors expressed comparable levels of Gata3 and E-Cad as the primary mammary tumor and that individual regenerated tumors also expressed comparable levels of Gata3 and E-Cad, indicating that the system is stable in maintaining Gata3 expression in cells and regenerated tumors (Figure S2D, E). In sum, we successfully developed a murine luminal type mammary tumor system in which mammary tumor cells express high levels of Gata3 and are capable of generating Gata3 positive luminal tumors once transplanted into the MFPs of mice.

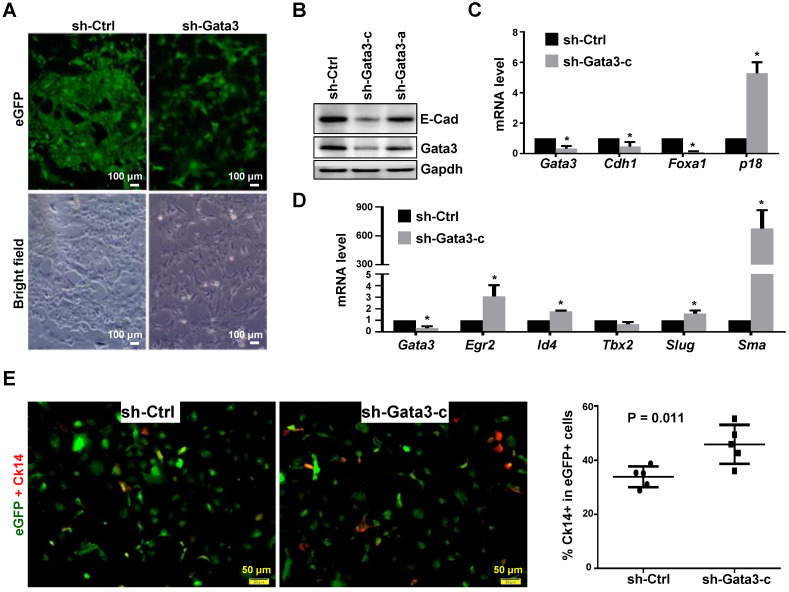

Depletion of Gata3 in luminal tumor cells promotes basal-like differentiation, induces p18, and reduces cell proliferation

To determine whether and how depletion of GATA3 in established mammary tumor cells promotes basal differentiation and impacts tumor progression, we took advantage of the newly established Gata3 positive murine luminal type tumor model system. We knocked down Gata3 in Gata3 positive luminal tumor cells and noticed that Gata3 knockdown (KD) cells displayed an elongated and spiky appearance with isolated and spreading features, while control cells exhibited a typical cobblestone morphology and maintained close contact with neighboring cells (Figure 4A, B). KD of Gata3 induced the expression of p18 and reduced cell proliferation (Figure 4C, and data not shown), which is consistent with our previous finding that p18 is a downstream target of GATA3 constraining luminal cell proliferation. In addition to the reduced expression of luminal differentiation markers such as E-cad and Foxa1, depletion of Gata3 significantly enhanced the expression of basal differentiation markers and transcription factors, such as Sma, Egr2, Slug, and Id4 (Figure 4C, D). We determined basal-like differentiation by Ck14 staining and found that the percentage of Ck14 positive cells in the Gata3-depleted group was significantly higher than in the control group (Figure 4E, Figure S3). We knocked down GATA3 in the human luminal breast cancer cell line, T47D, and again found that the expression of genes associated with luminal differentiation, such as CDH1 and ESR1, was significantly downregulated. However, the expression of genes associated with basal differentiation such as TWIST2, EGR2, and SMA, was not drastically upregulated (Figure S4). The reason the expression of basal genes in T47D cells was not clearly enhanced is likely because T47D cells are in terminal differentiation status after long-term and multi-passage culture. It was indeed demonstrated that T47D cells are terminally differentiated and resistant to further differentiation 54. Together, these results indicate that depletion of Gata3 in luminal tumor cells reduces luminal differentiation but stimulates basal-like differentiation in vitro.

Figure 4.

Depletion of Gata3 in luminal tumor cells promotes basal-like differentiation in vitro. (A, B) Luminal mammary tumor cells from MMTV-PyMT mice were infected with psi-LVRU6GP-control (sh-Ctrl) or psi-LVRU6GP-Gata3 targeting different sequences of mouse Gata3 (sh-Gata3-a and sh-Gata3-c), selected with puromycin, and analyzed by phase-contrast and fluorescence microscope (A) or western blot (B). Note that sh-Ctrl cells exhibited cobblestone morphology and close-contact with neighboring cells at cell junctions whereas sh-Gata3 cells displayed an elongated and spiky appearance and were isolated. (C, D) MMTV-PyMT luminal tumor cells infected with sh-Ctrl and sh-Gata3-c were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Data represent the mean ± SD from triplicates of primary tumor cells of each group. The asterisk (*) denotes a statistical significance from sh-Ctrl and sh-Gata3-c samples determined by student's t-test. (E) Representative immunofluorescent staining analysis of the MMTV-PyMT luminal tumor cells infected with sh-Ctrl and sh-Gata3-c. Cells were immunostained with antibodies against eGFP (green) and Ck14 (red). Percentage of Ck14 positive cells in the eGFP positive cell population was calculated. Data represent the mean ± SD from more than 500 eGFP positive cells in five randomly selected fields for each group of the two independent experiments.

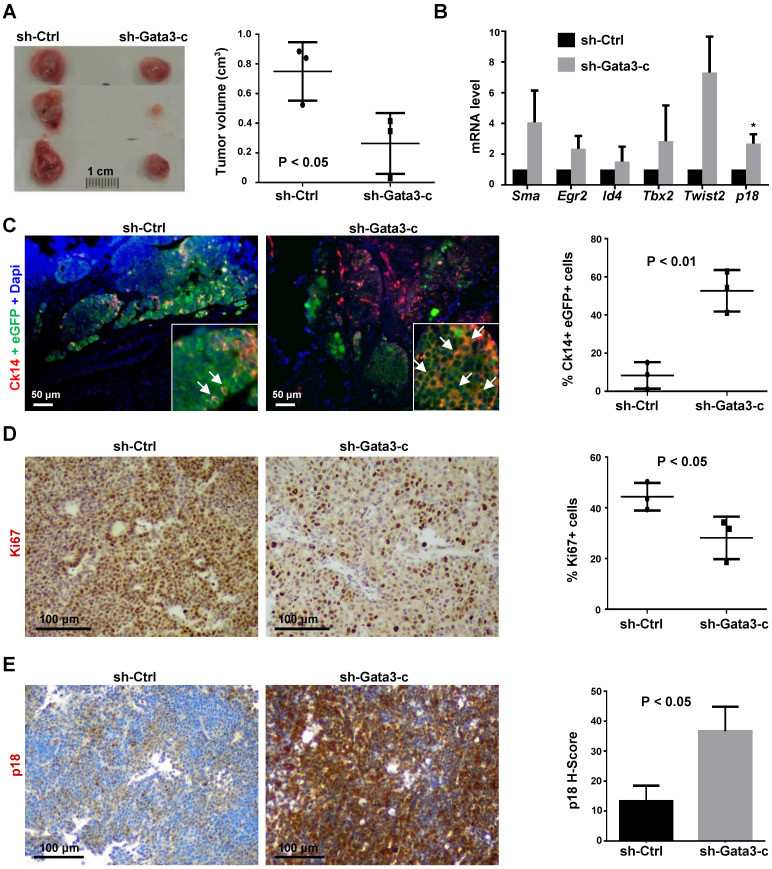

We then transplanted MMTV-PyMT luminal tumor cells into MFPs of NCG mice and unexpectedly found that Gata3 depleted cells resulted in a significantly smaller tumor than control cells (Figure 5A). Consistent with the data derived from in vitro analyses, tumors generated from Gata3 depleted cells also expressed higher levels of p18 mRNA and genes associated with basal differentiation (Figure 5B). The percentage of Ck14 positive cells in Gata3 depleted tumor cells was significantly higher than in control tumor cells (Figure 5C, Figure S5), confirming that depletion of Gata3 promotes basal-like differentiation in luminal tumor cells in vivo.

Figure 5.

Depletion of Gata3 converts luminal type mammary tumors into basal-like tumors. (A) MMTV-PyMT luminal tumor cells infected with sh-Ctrl and sh-Gata3-c were transplanted into the mammary fat pads (MFPs) of female NCG mice. Gross appearance of tumors formed 8 weeks after transplantation is shown (left panel) and tumor volumes are plotted (right panel). Data represent the average tumor volumes ±SD of three tumors from individual animals per group. (B) mRNA levels of the indicated genes in regenerated tumor tissues were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Results represent the mean ± SD of three tumors from individual animals per group. The asterisk (*) denotes a statistical significance from sh-Ctrl and sh-Gata3-c samples determined by student's t-test. (C, D, E) Mammary tumors formed by transplantation of MMTV-PyMT luminal tumor cells stably expressing sh-Ctrl or sh-Gata3-c were immunostained with antibodies against eGFP and Ck14 (C), Ki67 (D), or p18 (E). The percentages of Ck14-positive cells were calculated from eGFP-positive cells, and the results represent the mean ± SD of two individual tumors per group. Ck14 and eGFP double positive cells are indicated by white arrows (C). The percentages of Ki67-positive cells were quantitated in five randomly selected fields in sections, and the results represent the mean ± SD of three animals per group (D). The H-scores for p18 were calculated. The results represent the mean ± SD of three individual tumors per group (E).

IHC analysis revealed that Gata3 depleted tumors displayed significantly less Ki67 and more p18 positive cells than control tumors (Figure 5D, E, Figure S6), indicating that Gata3 depleted tumor cells proliferate slower than control cells in vivo. The observation that Gata3 depletion in luminal tumor cells induces p18 with reduction of cell proliferation and tumor growth is consistent with our previous finding that p18 is a downstream target of GATA3 restraining luminal cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. These results also suggest that induction of p18 and reduction of cell proliferation by depletion of Gata3 in luminal tumor cells are responsible for decreased tumor growth, even though Gata3 deficiency promotes luminal-to-basal differentiation.

GATA3 and basal marker expression levels are inversely related in human basal-like breast cancers

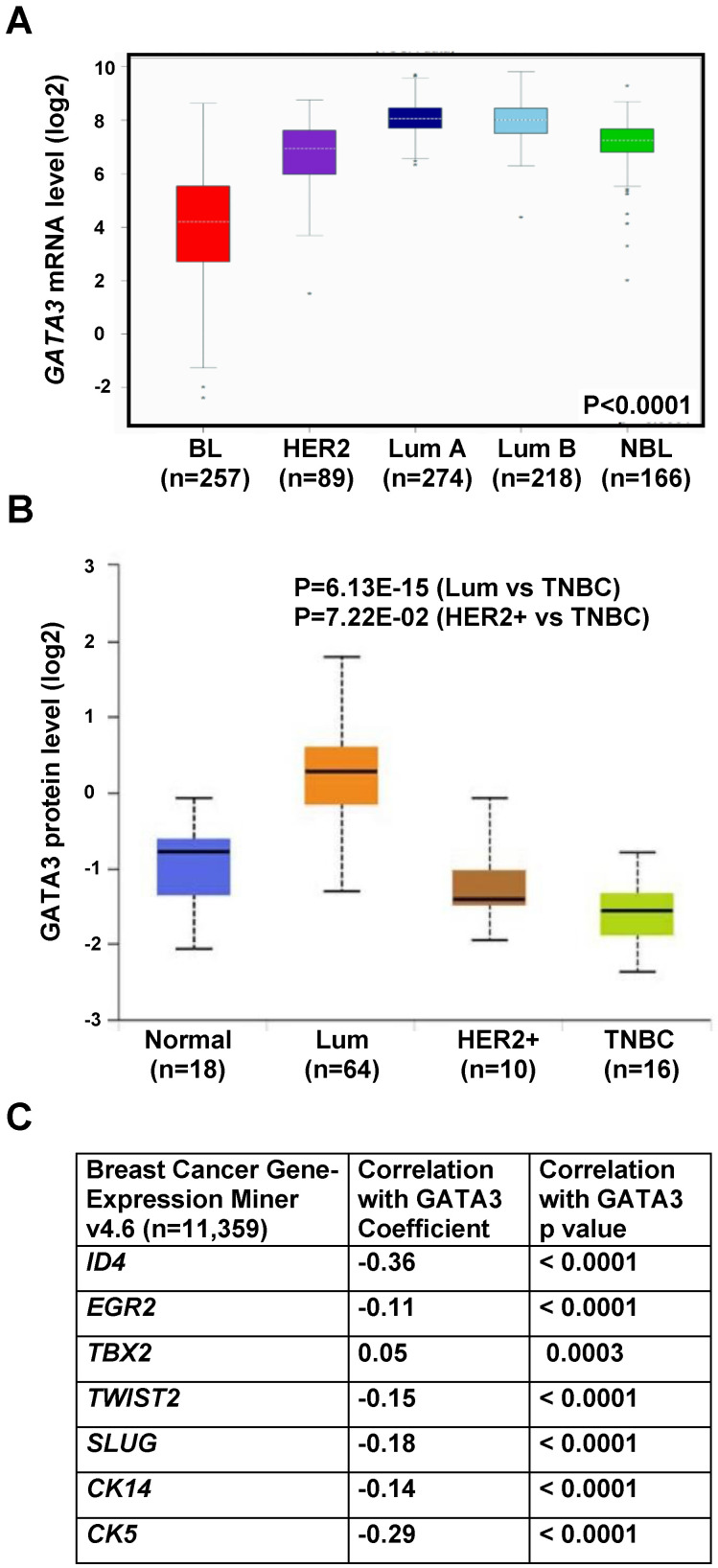

To determine whether our murine tumors model human breast cancers, we queried GATA3 expression in TCGA breast cancer patient sample sets 48. We found that GATA3 mRNA was highly correlated with breast tumor intrinsic subtypes. Specifically, GATA3 mRNA was significantly low in basal-like tumors and high in luminal A and B tumors (Figure 6A), which is consistent with our previous analysis in the NKI breast cancer patient sample dataset 27. Since basal-like breast cancer accounts for approximately 70% of TNBCs, we then analyzed GATA3 protein levels in the Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) breast cancer patient sample set and GATA3 mRNA levels in TCGA breast cancer patient samples 47, 48 according to major clinical subclass. We found that GATA3 expression was significantly low in TNBC and high in luminal tumors (Figure 6B and Figure S7B). Correlation analysis revealed a significant inverse correlation between mRNA expression of GATA3 with ID4, TWIST2, SLUG, CK14 and CK5, all genes associated with basal differentiation (Figure 6C and Figure S7A). These clinical findings, consistent with our results in mice, further confirm that loss of GATA3 promotes basal-like cancer development and progression.

Figure 6.

Correlation analysis of GATA3 with basal markers and subtypes in human breast cancers. (A) Analysis of GATA3 mRNA expression in TCGA breast cancer patient samples according to molecular tumor subtype. (B) Analysis of GATA3 protein levels in the Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) breast cancer dataset according to major subclass (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html). (C) Correlation analysis of mRNA expression of GATA3 and basal markers in human breast cancer gene expression miner v4.6 dataset (http://bcgenex.ico.unicancer.fr/BC-GEM/GEM-requete.php).

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrate that haploid loss of Gata3 reduces MEC proliferation with induction of p18, impairs luminal differentiation, but promotes basal differentiation in mammary development. p18 deficiency rescues the proliferative defect caused by haploid loss of Gata3 and induces luminal type mammary tumors. Haploid loss of Gata3 by heterozygous germline deletion of Gata3, although insufficient to induce mammary tumors alone, changes the properties of mammary tumors induced by p18 deficiency, resulting in their malignant and luminal-to-basal-like transformation. By investigating MMTV-PyMT mouse mammary tumors, we found that expression of Gata3 negatively correlates with basal differentiation markers in tumor cells. We generated a Gata3 positive luminal type tumor model system and discovered that depletion of Gata3 in luminal tumor cells reduces cell proliferation with induction of p18, but promotes basal-like differentiation. We further confirmed that GATA3 and basal marker expression levels are inversely correlated in human basal-like breast cancers. This study provides the first genetic evidence demonstrating that loss-of-function of GATA3 induces basal-like breast cancer. Furthermore, our finding suggests that basal-like breast cancer may also originate from luminal type cancers.

A challenge in investigating the function of GATA3 in vivo is that depletion of Gata3 in mice results in early lethality, proliferative defects, or apoptosis 18-21, 32, preventing the determination of its loss-of-function role in controlling cell fate in tumor development and progression. We and other groups identified a few tumor suppressors, p18 and caspase 14 27, 36, 40, as well as oncogenes, cyclin D and c-Myc 39, 55, as critical targets of GATA3 in controlling mammary or lymphoid cell proliferation. Of the identified candidates, knockdown of p18 or overexpression of cyclin D has been reported to rescue proliferative defects induced by GATA3 knockdown in T cells or breast cancer cells in vitro 40, 41, 55. However, whether these candidates play a critical role in vivo in facilitating GATA3 defective cell proliferation and differentiation in tumorigenesis remains to be investigated. We previously reported that p18 is a downstream target of GATA3 and restrains luminal progenitor cell proliferation 27, the findings presented in this paper provide genetic evidence suggesting that loss-of-function of Gata3 results in accumulation of p18 in luminal progenitor cells, blocking them from entering an active cell cycle and undergoing subsequent aberrant basal differentiation. Loss of p18 stimulates proliferation of luminal progenitor cells and initiates luminal tumorigenesis with minimal impairment of luminal lineage differentiation in the presence of functional Gata3. Our results demonstrating that p18 depletion rescues the proliferative defects induced by haploid loss of Gata3 and that p18;Gata3 double mutant mice develop basal-like mammary tumors suggest that depletion of p18 is required for proliferation of GATA3 defective cells and for development of GATA3 deficient basal-like mammary tumors.

Consistent with the findings derived from mice, in human breast cancers, loss of p18 and amplification or overexpression of cyclin D and CDK4 are frequently detected in luminal type tumors whereas loss of GATA3 expression and loss or mutation of Rb are key features of BLBCs 8, 27-31. In addition to the results from mice showing that loss of p18 alone or loss of both Rb and p107 induces GATA3-positive luminal tumors 27, 43, these findings suggest that loss-of-function of the p18-cyclin D/CDK4-Rb pathway induces luminal tumorigenesis, and loss of Gata3 converts the p18-cyclin D/CDK4-Rb pathway deficient luminal type tumors into basal-like tumors. Interestingly, though loss-of-function of the p18-cyclin D/CDK4-Rb pathway is a common event in both luminal and basal-like breast cancers, loss of or mutation of Rb per se is mainly detected in BLBCs, which also explains why clinically defined luminal type tumors, but not basal-like tumors, are more sensitive to CDK4 inhibitors since CDK4 promotes cell proliferation dependent on functional RB.

The function of GATA3 in suppressing breast tumor development, metastasis, and EMT has been well studied by overexpressing GATA3 in cell line models 33, 34, 56, 57. Two independent groups investigated the role of loss-of-function of Gata3 in mammary tumor development and progression in MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice 35, 36. Heterozygous germline mutation of Gata3 in MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice accelerates mammary tumor onset 36 and loss of Gata3 marks malignant progression in MMTV-PyMT mammary tumors 35. However, due to growth defects induced by long-term loss of Gata3 and apoptosis caused by acute loss of Gata3 in differentiated tumor cells 27, 35, 40, it remains elusive if Gata3 loss promotes basal differentiation in breast cancer development and progression. In the present study, we found that haploid loss of Gata3 by heterozygous germline deletion impaired luminal but activated basal differentiation in mammary epithelial and cancerous cells. Depletion of Gata3 in MMTV-PyMT luminal tumor cells further confirmed the activation of basal and impairment of luminal differentiation. These results provide compelling genetic evidence suggesting that in addition to inactivation of luminal differentiation, loss of Gata3 promotes basal-like differentiation in mammary and tumor development and progression.

It has long been suggested that BLBCs originate from mammary basal epithelial cells. Recently, a few groups demonstrated that BRCA1 mutant BLBCs may originate from aberrant luminal progenitor cells 14-16. In our previous study, we discovered that p18 deficiency stimulates luminal progenitor cell proliferation and induces luminal mammary tumors, and that germline deletion of Brca1 impairs luminal but activates basal differentiation of p18 deficient luminal progenitor cells, eventually leading to development of BLBC 17, 27. These findings confirm that the aberrantly differentiated luminal epithelial cells are the origin of BLBCs developed in mice carrying heterozygous germline mutation of Brca1. In the present study, we utilized a similar mouse model system to investigate the role of haploid loss of Gata3 in mammary cell differentiation. To avoid aberrant differentiation caused by artificially choosing distinct cre transgenic mice and directing Gata3 deletion in specific cell lineages in conditional Gata3f/f mice, we analyzed mice harboring heterozygous germline deletion of Gata3 which enables us to investigate the role of haploid of Gata3 in all cell linages in an unbiased manner. We demonstrated that heterozygous germline deletion of Gata3 also impairs luminal but activates basal differentiation of p18 deficient luminal progenitor cells, which eventually lead to development of BLBCs. Furthermore, we discovered that depletion of Gata3 in MMTV-PyMT luminal tumor cells promotes basal differentiation and leads to development of BLBCs. These findings not only confirm the function of Gata3 loss in promoting basal-like differentiation in mammary epithelial and cancerous cells, but also suggest the luminal cell origin of non-BRCA1 mutant BLBCs.

Conclusions

This study provides the first genetic evidence demonstrating that loss-of-function of GATA3 directly induces basal-like breast cancer. Furthermore, our finding suggests that basal-like breast cancer may also originate from luminal type cancers.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and table.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Program (2019B030301009), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81972637), High-level university phase 2 construction funding from Shenzhen University (860-00000210), Natural Science Foundation of Shenzhen City (JCYJ20190808115603580 and JCYJ20190808165803558), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2019A1515011343 and 2021A1515011145), DOD Idea Expansion Award (W81XWH-13-1-0282), and research funds from Shenzhen University. We thank Dr. I-Cheng Ho for providing Gata3f/f mice, Emely Pimentel and Alexandria Scott for technical support, the FACS core facility at University of Miami and Shenzhen University for cell sorting, and the DVR core facility for animal husbandry.

Author Contributions

FB, CZ, and XHP designed the research studies. FB, CZ, XL, HLC, SL, JM and XHP conducted experiments and analyzed data. WGZ provided administrative and material support; FB, CZ and XHP wrote the manuscript. FB and XHP provided financial support, XHP supervised the project. All authors made comments on the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Miami and Shenzhen University approved all animal procedures.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- p18

p18INK4c

- MaSC

mammary stem cell

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- ER

estrogen receptor

- PGR

progesterone receptor

- TNBC

triple-negative breast cancer

- BLBC

basal-like breast cancer

- HDR

hypoparathyroidism-deafness-renal disease

- HSC

hematopoietic stem cell

- MEC

mammary epithelial cell

- NCG

NOD-Prkdcem26Cd52Il2rgem26Cd22/Nju

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- E-Cad

E-cadherin

- KD

knockdown

- MFP

mammary fat pad

- LP

luminal progenitor

References

- 1.Visvader JE, Stingl J. Mammary stem cells and the differentiation hierarchy: current status and perspectives. Genes Dev. 2014;28:1143–58. doi: 10.1101/gad.242511.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu NY, Nolan E, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE. Stem Cells and the Differentiation Hierarchy in Mammary Gland Development. Physiological reviews. 2020;100:489–523. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00040.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shackleton M, Vaillant F, Simpson KJ, Stingl J, Smyth GK, Asselin-Labat ML. et al. Generation of a functional mammary gland from a single stem cell. Nature. 2006;439:84–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rios AC, Fu NY, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE. In situ identification of bipotent stem cells in the mammary gland. Nature. 2014;506:322–7. doi: 10.1038/nature12948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stingl J, Eirew P, Ricketson I, Shackleton M, Vaillant F, Choi D. et al. Purification and unique properties of mammary epithelial stem cells. Nature. 2006;439:993–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel PM, Muller WJ. Transcription factor regulatory networks in mammary epithelial development and tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2010;29:2753–9. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Althuis MD, Fergenbaum JH, Garcia-Closas M, Brinton LA, Madigan MP, Sherman ME. Etiology of hormone receptor-defined breast cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1558–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koboldt DC, Fulton RS, McLellan MD, Schmidt H, Kalicki-Veizer J, McMichael JF. et al. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;487:330–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA. et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–52. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H. et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10869–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haupt B, Ro JY, Schwartz MR. Basal-like breast carcinoma: a phenotypically distinct entity. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:130–3. doi: 10.5858/134.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim MJ, Ro JY, Ahn SH, Kim HH, Kim SB, Gong G. Clinicopathologic significance of the basal-like subtype of breast cancer: a comparison with hormone receptor and Her2/neu-overexpressing phenotypes. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1217–26. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Livasy CA, Karaca G, Nanda R, Tretiakova MS, Olopade OI, Moore DT. et al. Phenotypic evaluation of the basal-like subtype of invasive breast carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:264–71. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim E, Vaillant F, Wu D, Forrest NC, Pal B, Hart AH. et al. Aberrant luminal progenitors as the candidate target population for basal tumor development in BRCA1 mutation carriers. Nat Med. 2009;15:907–13. doi: 10.1038/nm.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Proia TA, Keller PJ, Gupta PB, Klebba I, Jones AD, Sedic M. et al. Genetic predisposition directs breast cancer phenotype by dictating progenitor cell fate. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:149–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molyneux G, Geyer FC, Magnay FA, McCarthy A, Kendrick H, Natrajan R. et al. BRCA1 basal-like breast cancers originate from luminal epithelial progenitors and not from basal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:403–17. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bai F, Smith MD, Chan HL, Pei XH. Germline mutation of Brca1 alters the fate of mammary luminal cells and causes luminal-to-basal mammary tumor transformation. Oncogene. 2013;32:2715–25. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandolfi PP, Roth ME, Karis A, Leonard MW, Dzierzak E, Grosveld FG. et al. Targeted disruption of the GATA3 gene causes severe abnormalities in the nervous system and in fetal liver haematopoiesis. Nat Genet. 1995;11:40–4. doi: 10.1038/ng0995-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asselin-Labat ML, Sutherland KD, Barker H, Thomas R, Shackleton M, Forrest NC. et al. Gata-3 is an essential regulator of mammary-gland morphogenesis and luminal-cell differentiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:201–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kouros-Mehr H, Slorach EM, Sternlicht MD, Werb Z. GATA-3 maintains the differentiation of the luminal cell fate in the mammary gland. Cell. 2006;127:1041–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grigorieva IV, Mirczuk S, Gaynor KU, Nesbit MA, Grigorieva EF, Wei Q. et al. Gata3-deficient mice develop parathyroid abnormalities due to dysregulation of the parathyroid-specific transcription factor Gcm2. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2144–55. doi: 10.1172/JCI42021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurek D, Garinis GA, van Doorninck JH, van der Wees J, Grosveld FG. Transcriptome and phenotypic analysis reveals Gata3-dependent signalling pathways in murine hair follicles. Development. 2007;134:261–72. doi: 10.1242/dev.02721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho IC, Tai TS, Pai SY. GATA3 and the T-cell lineage: essential functions before and after T-helper-2-cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:125–35. doi: 10.1038/nri2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Esch H, Groenen P, Nesbit MA, Schuffenhauer S, Lichtner P, Vanderlinden G. et al. GATA3 haplo-insufficiency causes human HDR syndrome. Nature. 2000;406:419–22. doi: 10.1038/35019088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ali A, Christie PT, Grigorieva IV, Harding B, Van Esch H, Ahmed SF. et al. Functional characterization of GATA3 mutations causing the hypoparathyroidism-deafness-renal (HDR) dysplasia syndrome: insight into mechanisms of DNA binding by the GATA3 transcription factor. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:265–75. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Usary J, Llaca V, Karaca G, Presswala S, Karaca M, He X. et al. Mutation of GATA3 in human breast tumors. Oncogene. 2004;23:7669–78. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pei XH, Bai F, Smith MD, Usary J, Fan C, Pai SY. et al. CDK inhibitor p18(INK4c) is a downstream target of GATA3 and restrains mammary luminal progenitor cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:389–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stone A, Zotenko E, Locke WJ, Korbie D, Millar EK, Pidsley R. et al. DNA methylation of oestrogen-regulated enhancers defines endocrine sensitivity in breast cancer. Nature communications. 2015;6:7758.. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8758. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdel-Hafiz HA. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Tamoxifen Resistance in Luminal Breast Cancer. Diseases. 2017. 5. doi: 10.3390/diseases5030016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Yoon NK, Maresh EL, Shen D, Elshimali Y, Apple S, Horvath S. et al. Higher levels of GATA3 predict better survival in women with breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1794–801. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asch-Kendrick R, Cimino-Mathews A. The role of GATA3 in breast carcinomas: a review. Hum Pathol. 2016;48:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lim KC, Lakshmanan G, Crawford SE, Gu Y, Grosveld F, Engel JD. Gata3 loss leads to embryonic lethality due to noradrenaline deficiency of the sympathetic nervous system. Nat Genet. 2000;25:209–12. doi: 10.1038/76080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chou J, Lin JH, Brenot A, Kim JW, Provot S, Werb Z. GATA3 suppresses metastasis and modulates the tumour microenvironment by regulating microRNA-29b expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:201–13. doi: 10.1038/ncb2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan W, Cao QJ, Arenas RB, Bentley B, Shao R. GATA3 inhibits breast cancer metastasis through the reversal of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14042–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.105262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kouros-Mehr H, Bechis SK, Slorach EM, Littlepage LE, Egeblad M, Ewald AJ. et al. GATA-3 links tumor differentiation and dissemination in a luminal breast cancer model. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:141–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asselin-Labat ML, Sutherland KD, Vaillant F, Gyorki DE, Wu D, Holroyd S. et al. Gata-3 negatively regulates the tumor-initiating capacity of mammary luminal progenitor cells and targets the putative tumor suppressor caspase-14. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:4609–22. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05766-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ku CJ, Hosoya T, Maillard I, Engel JD. GATA-3 regulates hematopoietic stem cell maintenance and cell-cycle entry. Blood. 2012;119:2242–51. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-366070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frelin C, Herrington R, Janmohamed S, Barbara M, Tran G, Paige CJ. et al. GATA-3 regulates the self-renewal of long-term hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:1037–44. doi: 10.1038/ni.2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Misumi I, Gu AD, Curtis TA, Su L, Whitmire JK. et al. GATA-3 controls the maintenance and proliferation of T cells downstream of TCR and cytokine signaling. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:714–22. doi: 10.1038/ni.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hosokawa H, Tanaka T, Kato M, Shinoda K, Tohyama H, Hanazawa A. et al. Gata3/Ruvbl2 complex regulates T helper 2 cell proliferation via repression of Cdkn2c expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:18626–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311100110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu S, Lam Chan H, Bai F, Ma J, Scott A, Robbins DJ. et al. Gata3 restrains B cell proliferation and cooperates with p18INK4c to repress B cell lymphomagenesis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:64007–20. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pei XH, Xiong Y. Biochemical and cellular mechanisms of mammalian CDK inhibitors: a few unresolved issues. Oncogene. 2005;24:2787–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang Z, Deng T, Jones R, Li H, Herschkowitz JI, Liu JC. et al. Rb deletion in mouse mammary progenitors induces luminal-B or basal-like/EMT tumor subtypes depending on p53 status. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3296–309. doi: 10.1172/JCI41490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bai F, Chan HL, Scott A, Smith MD, Fan C, Herschkowitz JI. et al. BRCA1 Suppresses Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Stem Cell Dedifferentiation during Mammary and Tumor Development. Cancer Res. 2014;74:6161–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goulding H, Pinder S, Cannon P, Pearson D, Nicholson R, Snead D. et al. A new immunohistochemical antibody for the assessment of estrogen receptor status on routine formalin-fixed tissue samples. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:291–4. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang C, Bai F, Zhang LH, Scott A, Li E, Pei XH. Estrogen promotes estrogen receptor negative BRCA1-deficient tumor initiation and progression. Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20:74.. doi: 10.1186/s13058-018-0996-9. doi: 10.1186/s13058-018-0996-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen F, Chandrashekar DS, Varambally S, Creighton CJ. Pan-cancer molecular subtypes revealed by mass-spectrometry-based proteomic characterization of more than 500 human cancers. Nature communications. 2019;10:5679.. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13528-0. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13528-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jezequel P, Gouraud W, Ben Azzouz F, Guerin-Charbonnel C, Juin PP, Lasla H, et al. bc-GenExMiner 4.5: new mining module computes breast cancer differential gene expression analyses. Database: the journal of biological databases and curation. 2021; 2021. doi: 10.1093/database/baab007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Lim E, Wu D, Pal B, Bouras T, Asselin-Labat ML, Vaillant F. et al. Transcriptome analyses of mouse and human mammary cell subpopulations reveal multiple conserved genes and pathways. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R21.. doi: 10.1186/bcr2560. doi: 10.1186/bcr2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guo W, Keckesova Z, Donaher JL, Shibue T, Tischler V, Reinhardt F. et al. Slug and Sox9 cooperatively determine the mammary stem cell state. Cell. 2012;148:1015–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin EY, Jones JG, Li P, Zhu L, Whitney KD, Muller WJ. et al. Progression to malignancy in the polyoma middle T oncoprotein mouse breast cancer model provides a reliable model for human diseases. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2113–26. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63568-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takai K, Drain AP, Lawson DA, Littlepage LE, Karpuj M, Kessenbrock K. et al. Discoidin domain receptor 1 (DDR1) ablation promotes tissue fibrosis and hypoxia to induce aggressive basal-like breast cancers. Genes Dev. 2018;32:244–57. doi: 10.1101/gad.301366.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Asselin-Labat ML, Shackleton M, Stingl J, Vaillant F, Forrest NC, Eaves CJ. et al. Steroid hormone receptor status of mouse mammary stem cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1011–4. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brown KA, Aakre ME, Gorska AE, Price JO, Eltom SE, Pietenpol JA. et al. Induction by transforming growth factor-beta1 of epithelial to mesenchymal transition is a rare event in vitro. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:R215–31. doi: 10.1186/bcr778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shan L, Li X, Liu L, Ding X, Wang Q, Zheng Y. et al. GATA3 cooperates with PARP1 to regulate CCND1 transcription through modulating histone H1 incorporation. Oncogene. 2013;33:3205–16. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dydensborg AB, Rose AA, Wilson BJ, Grote D, Paquet M, Giguere V. et al. GATA3 inhibits breast cancer growth and pulmonary breast cancer metastasis. Oncogene. 2009;28:2634–42. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chou J, Provot S, Werb Z. GATA3 in development and cancer differentiation: cells GATA have it! J Cell Physiol. 2010;222:42–9. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and table.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.