Abstract

Human cooperation is often claimed to be special and requiring explanations based on gene–culture coevolution favouring a desire to copy common social behaviours. If this is true, then individuals should be motivated to both observe and copy common social behaviours. Previous economic experiments, using the public goods game, have suggested individuals' desire to sacrifice for the common good and to copy common social behaviours. However, previous experiments have often not shown examples of success. Here we test, on 489 participants, whether individuals are more motivated to learn about, and more likely to copy, either common or successful behaviours. Using the same social dilemma and standard instructions, we find that individuals were primarily motivated to learn from successful rather than common behaviours. Consequently, social learning disfavoured costly cooperation, even when individuals could observe a stable, pro-social level of cooperation. Our results call into question explanations for human cooperation based on cultural evolution and/or a desire to conform with common social behaviours. Instead, our results indicate that participants were motivated by personal gain, but initially confused, despite receiving standard instructions. When individuals could learn from success, they learned to cooperate less, suggesting that human cooperation is maybe not so special after all.

Keywords: human cooperation, social learning, cultural evolution, conformity, public goods game

1. Introduction

Humans often appear to cooperate in ways that cannot be explained by genetical evolution alone [1–3]. For example, individuals may tip a waiter in a restaurant they will never visit again, honestly report their taxable income, spend time recycling rubbish, pay more for environmentally friendly products, donate food to food banks and blood to blood banks, even though they will never learn who benefited and in extreme cases even risk their lives to heroically save strangers [4–10]. Likewise, in laboratory experiments, many individuals appear willing to share financial windfalls and to trust, reward or punish strangers at personal cost even when there are no apparent benefits (phenomena often described as ‘strong reciprocity’) [11–16].

A proposed explanation for such cooperation is that humans have also evolved culturally—through the behavioural, rather than genetical, copying of traits—to cooperate even in anonymous one-shot encounters with strangers [17–26]. The theoretical mechanisms for such cultural evolution often rely on the hypothesis that humans learn by observing others (social learning) and desire to conform with or copy common social behaviours, which can be indicative of local social norms [18,20,22,24,26,27]. If people desire to copy common behaviours, this could theoretically help fuel a self-reinforcing gene–culture coevolutionary ‘ratchet for both the importance of social norms and the intensity of prosociality’ [20]. For example, it is argued that humans have evolved a psychological preference for ‘avoiding behaviours that deviate from the common pattern’ and that such preferences are ‘probably either the products of purely cultural evolution (driven by cultural group selection), or coevolved products of genes responding to the novel social environments created by cultural group selection’ [18].

Experiments using social dilemmas, such as the public goods game, have provided evidence consistent with a human desire to conform with common social behaviours and thus ‘not deviate from the common pattern’. In the public goods game, individuals can make monetary contributions to a group fund. Financially speaking, the group does best if everyone contributes fully, but individuals do best by contributing nothing, hence the social dilemma [28–32]. Many studies have shown that individuals tend to contribute partially and that most will condition their cooperation to local levels (either perfectly or imperfectly) [2,33–42]. This has led some to conclude that human cooperation is best described by a pro-social norm of ‘conditional cooperation’, which prescribes that one ought to play fair and ‘contribute at least as much as others' average contribution’ [39].

However, many experiments have only provided information on which behaviours are common and not the relative success of different behaviours [33,36,43–45]. Consequently, individuals in these experiments could not copy successful behaviours and may have only copied the common behaviour because they were unsure how to maximize income [33,36,46,47]. Outside the laboratory, in real-world scenarios that economic games aim to model and understand, individuals may be able to observe both common and successful behaviours and so could choose to learn from and/or copy either. If individuals are primarily motivated to copy successful, rather than common, social behaviours, then this will tend to undermine cooperation in situations with no personal benefit [48–50].

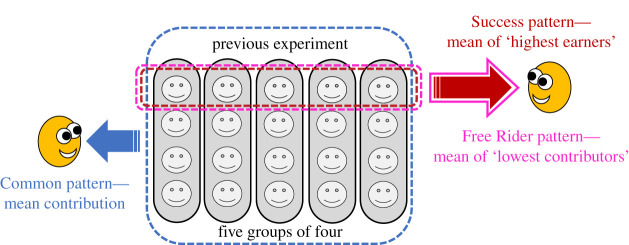

We experimentally tested if individuals preferred to learn about and/or copy either common or successful behaviours in a social dilemma (figure 1). We used two approaches. Either we controlled what type of information individuals saw, and measured how the responded, or we measured preferences directly by letting some individuals choose which type of information they would see. If individuals preferred to copy common behaviours, then they would condition their cooperation on our examples of common behaviour (‘Common pattern’, figure 1). By contrast, if individuals were uncertain on how to maximize income and preferred to learn from success, they would choose to learn from our examples of success (‘Success pattern’, figure 1).

Figure 1.

Components of social information. Participants played a repeated public goods game but saw no information about their own earnings nor about the behaviour of their groupmates. Instead, we showed them information in-between each round about behaviours in a previous experiment. The Common pattern was the overall mean contribution from the corresponding round of the previous experiment. The Success pattern was the mean contribution of the five highest earners (one from each of group) from the corresponding round. The Free Rider pattern was the same examples, but the highest earners were merely described as the ‘lowest contributors’, removing information on success. (Online version is in colour.)

To enable comparisons with previous studies [33,36,39], we used a linear public goods game, with the same payoffs and instructions and a similar pool of participants (students in Switzerland) [36]. This meant that the participants knew how to be successful if they understood the instructions, as has often been assumed in prior studies [36]. However, in contrast to many previous studies, we never showed individuals information about their own group [33,34,36,48,49,51]. Instead, we only showed our current participants information about the behaviour of a larger pool of individuals in a previous experiment (social information, figure 1). This prevented any within-group interactions and importantly prevented social learning from changing the social information itself [50,52–56].

2. Methods

(a) . Participants and software

The experiment was conducted entirely in z-Tree [57]. We recruited our 489 mostly student participants (262 female, 217 male, 1 other, 9 declined to answer) from the University of Lausanne HEC-LABEX participant pool using the ORSEE software [58] and excluded all participants from our previous experiments [58]. Participants received a show-up fee of 10 Swiss Francs (CHF). All earnings were rounded up to the nearest CHF, and the mean average payment including the show-up fee was 23.3 CHF, ranging from 18 CHF to 28 CHF, with a median and a mode of 23 CHF.

(b) . The public goods game

Other studies have investigated social learning in non-cooperative games [59]. However, because we are testing theories on the evolution of cooperation, we thought it more relevant to study a cooperative game. The game was repeated for six rounds in constant groups. We gave our participants full standard instructions on the game. We used the same game parameters, instructions and control questions (translated into French) as a prior study that concluded individuals preferred to condition their contributions upon the average group contribution [36]. Groups had four participants, each endowed with 20 monetary units (MU, 20 MU = 1 CHF). All contributions to the group fund were multiplied by 1.6 before being shared out equally. Therefore, the marginal per capita return (MPCR) was 1.6/4 = 0.4. This meant that the group income-maximizing decision was to contribute fully, but the individual payoff-maximizing decision was to contribute nothing (0 MU), regardless of what one's groupmates contributed. Consequently, within each group and within each round, the lowest contributors were always the highest earners.

(c) . Previous experiment

Showing individuals information from their own small group confounds social learning with within-group interactions such as reciprocity [60], signalling [61–63] and revenge [64,65], etc. [33,34,36,48,49,51]. We therefore only showed our participants information about how 20 participants behaved during the corresponding round of a previous experiment (figure 1). This previous experiment also involved groups of four individuals deciding how much to contribute (0–20 MU) to a public good with an MPCR of 0.4.

We wanted multiple rounds of ‘model’ data so that we could observe more learning and short-term cultural evolution. However, contributions normally decline in public goods games [32]. If individuals observe declining levels of cooperation, it is hard to test if individuals are learning from success or trying to match a declining group average [36,50]. Our solution was to show participants data from one of our own previous experiments that used peer punishment to stabilize mean contributions [66]. This meant that if contributions declined in this current study, this could not be attributed to individuals attempting to match, even imperfectly, the Common pattern [33,36,39]. By contrast, declining contributions would be expected if individuals learned from either the Success pattern or the Free Rider pattern.

Although punishment is often part of gene–culture coevolutionary theories, it is important to realize that our use of punishment is not a key feature of this experiment (in fact, our original plan was to show data from an experiment with a ‘no-information’ treatment, but we subsequently found the punishment data to be slightly more stable [50,66]). Our participants in this study were not aware that punishment was a feature of the previous experiment. Examples of highest earners were taken from each round of the public good decision stage of the experiment, before any potential punishment in the subsequent punishment stage. Telling our participants about the punishment stage would have needlessly complicated this study for little or no benefit. We were investigating a behavioural preference for learning from either common or successful behaviours; therefore, the definition of success (highest earners from public good stage) we used was consistent with the situation our current participants faced (contributing 0–20 MU to a public good without punishment).

Specifically, we told our participants they would learn about the contributions of individuals ‘who faced the same decision as you face today’. By this, we meant that both our participants and the participants in the previous experiment had to make the same basic decision, of how much to contribute (0–20 MU) to a public good. HEC-LABEX ethics committee approved our experiment, and we obtained written consent from all participants prior to starting [67].

(d) . Experimental treatments

In total, we had five treatments, and participants were randomly assigned to one treatment only. Three ‘dynamic’ treatments controlled which forms of social information groups observed, and participants knew that they and everyone else in their group would receive the same information. These dynamic treatments allowed us to infer from changes in behaviour if individuals were learning from success. In addition, we conducted two ‘choice’ treatments, where individuals chose to observe either the Common or the Success pattern.

In all three dynamic treatments, we allowed individuals to infer the most common behaviour in each round by showing them the overall average contribution of all 20 individuals to the public good in the corresponding round of the previous experiment (Common pattern, figure 1) [68,69]. Showing the average contribution is consistent with studies of conditional cooperation, which suggest that individuals condition their cooperation on local levels of cooperation [33,36,70]. If it is true that individuals desire to ‘not deviate from the common pattern’ [18] and/or if individuals are adhering to a pro-social norm of conditional cooperation [39], then this social information provides a salient coordination point to anchor their contributions upon. In our baseline treatment, this was the only information (Shown Common pattern, N = 112).

Our other two dynamic treatments showed the Common pattern along with some additional information. In the Shown Common + Success treatment (N = 128), we showed the Common pattern and also allowed individuals to infer the successful strategy, by showing them the average contribution of the five individuals who were each the highest earner in their group in that particular round (Success pattern, figure 1). We aggregated the behaviour of the five successful individuals into one value to make the level of information comparable with the Common pattern (one example for each). Here, individuals could ignore the extra information and still coordinate on the Common pattern, or learn, if needed, from the Success pattern to increase their own payoff. If individuals have a preference for learning from success, then contributions will decline compared to the baseline treatment (Shown Common pattern), which contained no information on relative success.

However, the effect of showing the Success pattern could affect contributions for other reasons. Not only does it contain an additional coordination point, but it also contains information on the lowest contributors (Free Riders). Such information may reduce contributions among individuals trying to condition their cooperation to local levels [36,49]. To control for the impact of these other factors, we also included a control treatment that showed identical values to those in the Shown Common + Success treatment but described the ‘highest earners’ as the ‘lowest contributors’ (Free Rider pattern, figure 1). This different framing provided a control treatment (Shown Common + Free Riders, N = 128), which allowed us to eliminate other factors when evaluating the impact of learning about success.

Our cumulative information design allowed us to directly test if individuals preferred to copy successful or common behaviours in the Shown Common + Success treatment. The other two dynamic treatments can be thought of as controls, which allowed us to know the baseline behaviour in the Shown Common pattern treatment and to control for all the changes due to factors other than learning from success in the Shown Common + Free Riders treatment.

The key instructions were as follows (fuller copy in the electronic supplementary material):

‘There will be six rounds of decision making. First, you and the other members of your group will make a decision, then after each round of decision making, you will receive only some information from another experiment.

More precisely, we will show you and the other members of your group the same information.

-

(1)

The average decision, in the corresponding round, of all 20 participants in the other experiment (we will show you the average decision, rounded to the nearest number);

-

(2)

The average decision, per round, of the individuals with the [highest earnings/lowest contribution] in each group. So, there were 5 groups and we will take the decision of the person who made the [most money/lowest contribution] in each group, and show you the average of these 5 decisions (rounded to the nearest number)’. [Shown Common + Success/Shown Common + Free Riders treatments]

To directly measure the preferences and desire of individuals for social information, we also randomly assigned some groups, in the same sessions as above, to a choice treatment: either a forced choice test (Forced Choice Test, N = 61) or an optional but costly choice test (Costly Choice Test, N = 60). In both of these treatments, participants made their choice between seeing either the Common pattern alone or the Success Pattern alone. They made their choice in the opening round, and it applied to all the remaining rounds.

The Forced Choice Test measured the relative preferences for the two forms of social information but risked obscuring preferences because even individuals who were ambivalent or had no desire for social information were still forced to make a choice (analogous to compulsory voting with no option to abstain). To complement this approach, we also used the Costly Choice treatment, where individuals had to pay 1 MU to make their choice, or they could choose to not pay and not receive any information (to abstain). This allowed us to measure the desire for the two forms of social information more generally.

(e) . Statistical analyses

We analysed the data using R-Studio and the z-Tree package [71]. All statistical tests were two-tailed.

3. Results

(a) . Deviating from the Common pattern

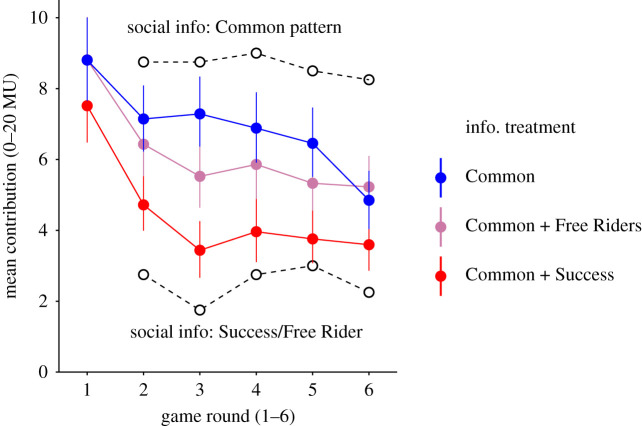

We found that when we included examples of successful behaviours, this led to less cooperation (lower contributions; figure 2 and electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Specifically, we found that contributions declined faster when participants could observe both the Common and the Success patterns rather than just the Common pattern (generalized linear mixed model with binomial logit-link function with random intercept for each participant (GLMM): Contribution ∼ Treatment × Period, estimated difference in coefficient of the decline = −0.05 ± 0.018, z = −2.741, p = 0.006; electronic supplementary material, table S1). Showing the Success pattern led to significantly lower levels of contributions in every round (rounds 2–6, the differences in round 1, before social information, were not significant; electronic supplementary material, table S2).

Figure 2.

Deviating from the Common pattern. Shown are the mean contributions per treatment per round of the game (filled circles, solid lines) plus 95% non-parametric bootstrapped confidence intervals. Also shown are the mean values of social information that we showed before rounds 2–6 (empty grey circles, dashed lines). Being shown examples of the ‘highest earners’ along with the Common pattern (Shown Common + Success Treatment) led to a significantly greater decline in contributions than when shown just the Common pattern or the identical information framed as the ‘lowest contributors’ (Common + Free Riders). (Online version is in colour.)

We confirmed that the decline in contributions in our Shown Common + Success treatment was not merely due to individuals responding to the knowledge of Free Riders. Specifically, contributions declined faster when participants were told they were observing the highest earners (Shown Common + Success) rather than when they saw the same pattern but were told they were observing the lowest contributors (Shown Common + Free Riders) (figure 2; GLMM: Contribution ∼ Treatment × Period, estimated difference in coefficient of the decline = −0.04 ± 0.018, z = −2.219, p = 0.026; electronic supplementary material, table S1). Being informed about success rather than the lowest contributors led to significantly lower levels of cooperation in every round (electronic supplementary material, table S2). For histograms of all contribution decisions, see electronic supplementary material, figures S2–S4.

(b) . Copying others’ success

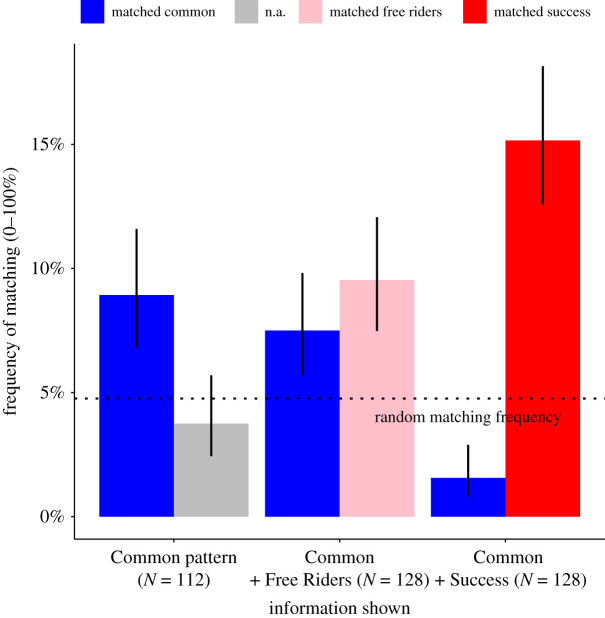

The cultural evolution of behaviour requires that individuals learn from or copy one another (social transmission) [72]. Copying can be defined in various ways. To keep things simple, we first recorded how often participants' contributions exactly matched the previous social information we had shown them (figure 3). Some matching is to be expected by chance, which will inflate estimates of copying, but we can still use this strict and objective test to compare relative rates of matching across treatments.

Figure 3.

Copying success and not the Common pattern. We estimated how often individuals copied the social information by recording how often their contributions matched the previous social information (blue = matched Common pattern; grey = matched Success pattern by chance (n.a.), pink = matched Free Rider pattern, red = matched Success pattern, along with 95% binomial confidence intervals). We also show an expected frequency of chance matching, calculated as 1/21 (because contributions could range from 0 to 20 MU). The Common pattern was shown in all three treatments, but the Success pattern was not shown in the Shown Common pattern treatment (grey) and was framed as the ‘lowest contributors’ rather than the ‘highest earners’ in the Shown Common + Free Riders treatment (pink). Individuals preferred to match success over the Common pattern. (Online version is in colour.)

When comparing treatments, we found a clear preference for matching the Success pattern over the Common pattern (figure 3). Individuals shown both the Common and the Success patterns matched the Common pattern only 2% of the time, significantly less often than the 9% of matching by those in the Shown Common pattern treatment (GLMM aggregating data by participant: Times matched Common pattern ∼ treatment, t = −4.4, p < 0.001, d.f. = 238; electronic supplementary material, table S3). Instead, individuals in the Shown Common + Success treatment showed a clear and significant preference for matching the Success pattern, doing so 15% of the time. This was significantly more than they copied the Common pattern (GLMM controlling for participant within Shown Common + Success treatment: matching frequency ∼ type of information, z = −7.2, p < 0.001, d.f. = 126; electronic supplementary material, table S4) and significantly more than those shown the identical examples but framed as lowest contributors (GLMM: times matched Success pattern ∼ treatment, t = −2.8, p = 0.005, d.f. = 254; electronic supplementary material, table S5).

By contrast, individuals shown the same examples of success but framed as the lowest contributors (Shown Common + Free Riders) showed no preference (GLMM controlling for participant within Shown Common + Free Riders treatment: matching frequency ∼ type of information, z = 1.3, p = 0.186, d.f. = 126; electronic supplementary material, table S6). These results confirm that individuals were copying success where possible and not merely conditionally cooperating with potential Free Riders.

(c) . Learning from others’ success

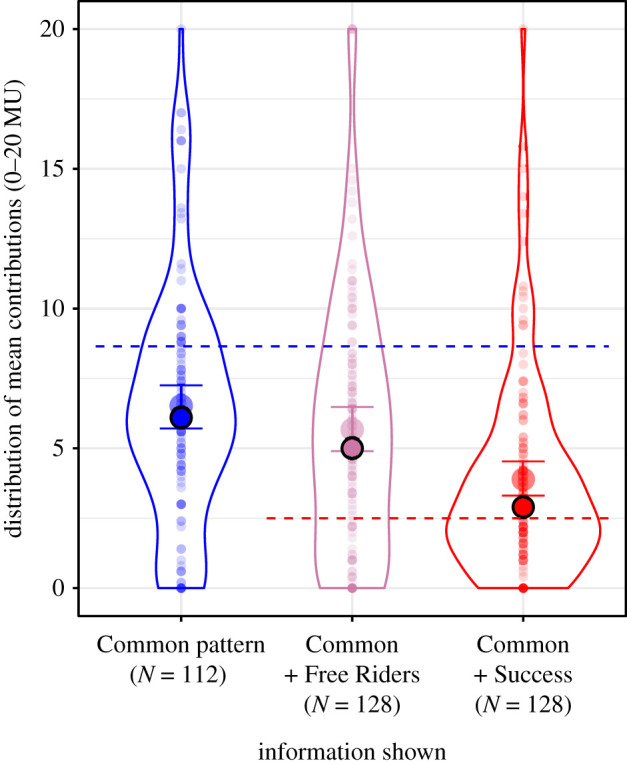

Social learning and cultural transmission can also occur in less exact ways, especially in a repeated scenario with non-constant examples. Therefore, we also analysed how each individual behaved in total, across all the rounds with social information. We calculated each individual's mean average contribution (ignoring the first round) (figure 4; electronic supplementary material, figure S5). We analysed the medians of these mean contributions (which were not normally distributed) and found that they significantly depended on treatment (Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2 = 28.8, d.f. = 2, p < 0.001, N = 368). In line with the above results, contributions in the Shown Common +Success treatment were significantly lower, by 3.2 MU, than in the Shown Common pattern treatment (median mean contribution for Shown Common pattern = 6.1 MU (30%) and for Shown Common + Success = 2.9 MU (15%); Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2 = 29.9, d.f. = 1, p < 0.001, N = 240, Cohen's d = 0.66).

Figure 4.

Learning from others' success. We calculated each individual's mean contribution over the five rounds with social information, and the corresponding mean value of information shown. Shown are the distributions, mean (large semi-transparent points) and median (large, solid, black-rimmed points) of these individual mean contributions, depending on treatment. Dashed lines are the mean values of the social information shown: Common pattern (blue, shown in all three treatments) or success/free rider pattern (red). The median/mean contribution deviated from the Common pattern (blue) when individuals could learn from success. Median/mean contributions were closest to the Success pattern (red). (Online version is in colour.)

Again, our control treatment confirmed that lower contributions were due to individuals learning from others' success and not merely responding to the knowledge of Free Riders. Contributions were significantly lower, by 2.1 MU, for those shown the Success pattern rather than the Free Rider pattern (figure 4; median mean contribution for Shown Common + Success = 2.9 MU (15%), and for Shown Common + Free Riders = 5.0 MU (25%); Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2 = 10.6, d.f. = 1, p = 0.001, N = 256, Cohen's d = 0.43; electronic supplementary material, figure S5). By contrast, there was no significant difference between those in the Shown Common pattern or Shown Common + Free Riders treatments (averaging across all rounds with social information, figure 4; Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2 = 3.0, d.f. = 1, p = 0.082, N = 240, Cohen's d = 0.19).

We can use these relative differences to conservatively estimate how much of the reduction in contributions when shown the Success pattern was due to learning about success versus other factors, such as responding to a competing coordination point or to the knowledge of relatively low contributors in the population. Approximately one-third of the reduction that occurred in the Common + Success treatment (−3.2 MU) also occurred in the ‘Free Riders’ treatment (−1.1 MU/−3.2 MU = 0.34), suggesting that the remaining two-thirds of reductions were due to learning about success (2.1/3.2 = 0.66) (figure 4).

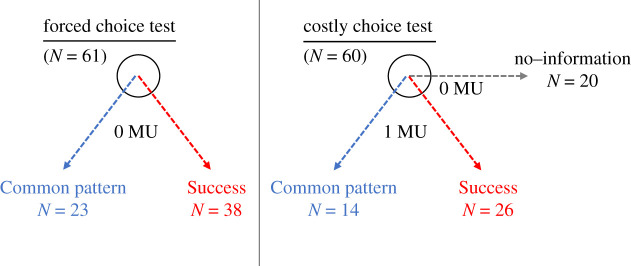

(d) . Choosing to see success

The above results tested how behaviour changed in response to being shown various forms of social information. For some additional groups, instead of controlling what behaviours individuals saw, we let each individual choose. This allowed us to directly test if individuals cared more about observing either common or successful behaviours (figure 5). Among individuals forced to choose between being shown either the Common pattern or the Success pattern, most individuals, nearly two-thirds, chose to see the Success pattern (forced choice test, N = 61, 38 chose Success pattern and 23 chose the Common pattern).

Figure 5.

Choosing to see success and not the Common pattern. We let some participants choose which social information to be shown, either the Common pattern or the Success pattern, for the rest of the experiment. In the forced choice test, they had to make this choice to proceed, even if they had no desire to see social information. In the costly choice test, they could pay 1 MU, one time, for this information, or they could choose to not pay and receive no information. The most popular choice in both tests was to be shown the Success pattern. (Online version is in colour.)

When social information was costly, the Success pattern was still the most popular choice, with 26/60 individuals agreeing to pay 1 MU to be shown the Success pattern (Costly Choice Test, N = 60). One-third of individuals declined to pay for access to social information (N = 20/60), and only 14 chose to see the Common pattern.

Combining both choice tests together, we find a significant preference to be shown the Success pattern (binomial sign test excluding those 20 individuals who chose not to pay for any information, two-tailed p-value on 64 choices for Success pattern in 101 trials = 0.009; figure 5). Although we cannot rule out that in each treatment, there was an equal preference between seeing either the Common or the Success pattern (binomial sign tests: Forced Choice test, two-tailed p-value on 38 successes in 61 trials = 0.072; Costly Choice test, two-tailed p-value on 26 successes in 40 trials = 0.081), we can rule out a significant preference to see Common pattern. Overall, 1.7 participants chose to see the Success pattern for every participant who chose to see the Common pattern (64/37 = 1.73).

4. Discussion

We found that overall, our participants, when facing a social dilemma, preferred to learn about, and copy, examples of successful behaviour, even though this meant deviating from the Common pattern (figures 3–5). Consequently, when individuals could observe examples of success, social learning did not stabilize cooperation (figure 2), even though there was a commonly known and stable example of pro-social behaviour (the Common pattern, figure 1). However, it may still be that individuals rely on copying common behaviours when examples of success are rare or opaque, which could favour the gene–cultural coevolution of cooperation in some circumstances, such as when costs are low [17].

Our results suggest that previous studies, which used similar participant pools (students at Swiss/western universities), but did not include examples of success, may have led to over-estimates of norm conformity and altruistic cooperation [33,35,36,73]. While it may appear obvious that individuals sometimes copy other individuals and conform, especially in domains such as fashion and language [74,75], it is not so clear that individuals copy costly behaviours [51,69,76]. Instead, individuals may use different cognition in cooperative contexts and prefer to copy more successful social behaviours even if they deviate from the Common pattern [77–79]. For example, if one observes a prestigious, successful individual, one may be motivated to imitate their exercise, clothing and diet [80,81], but not necessarily whether they donate to charities or not. Alternatively, individuals may appear to conform with the average level of tax compliance, but actually prefer to copy tax avoidance behaviours if such behaviours are associated with being successful [5,82–84].

One could use a range of different instructions to test if our results generalize to different set-ups or different cultures [85,86]. Here, we simply replicated ‘standard’ instructions and used a common participant pool, to enable comparisons with many prior key studies [1,33,36]. One may argue that our participants were not interested in social information because they had already internalized, over many years, the local social norm for social dilemmas corresponding to the anonymous public goods game [3,26]. However, this would not explain why our participants chose to learn about success, and why they contributed less when they saw examples of success, although psychology may differ when observing in-group and out-group members [87].

Alternatively, it is possible our participants were not interested in the overall average contribution of 20 participants and instead would have preferred to see the median or mode; however, this would contradict the results of previous studies that used the local mean [33,36,70]. Instead, we would argue that the overall average of 20 participants from the same participant pool would act as an attractive coordination point for any conditional cooperators, and often be seen as indicative of a local social norm, i.e. it would describe normal behaviour in such a situation (ergo the descriptive social norm [68]); however, we did not directly ask our participants how they interpreted the social information.

Our experimental design used stable social information from a previous experiment. This means the decline in contributions cannot be explained by a process of ‘imperfect conditional cooperation’ whereby individuals repeatedly undercut the previous group average [2,33,36,39]. Our interpretation is that participants were not motivated to conform to the Common pattern and were interested in learning from success. This indicates that many participants were either unsure or confused, despite having had standard instructions. While the use of success-based learning in contexts where the costs are unclear is consistent with many theories, including some gene–culture coevolutionary theories, this interpretation would invalidate the claim that public goods games show evidence of uniquely human cooperation demanding unique evolutionary explanations.

5. Conclusion

Even if humans do desire to conform with the ‘Common pattern’, it seems this desire was less motivating, in our participants, than their desire to learn from success. Therefore, cultural evolution models should not assume that because individuals conform in one domain, they will also conform in social dilemmas [77,88–92]. And policy makers should not overly rely on people's desire to conform with the Common pattern unless they can prevent people from seeing examples of success [84,93,94].

Supplementary Material

Ethics

HEC-LABEX ethics committee approved our experiment, and we obtained written consent from all participants prior to starting [67].

Data accessibility

Data can be found at https://osf.io/b6msn/ [67].

Authors' contributions

M.N.B.-C.: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; V.D'A.: formal analysis, investigation, project administration, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. Both authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was part funded by an HEC Research Fund grant awarded to M.N.B.-C. from the Faculty of Business and Economics of the University of Lausanne and part by Prof. Laurent Lehmann's independent research budget at the University of Lausanne.

References

- 1.Fehr E, Gachter S. 2002. Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature 415, 137-140. ( 10.1038/415137a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fehr E, Fischbacher U. 2003. The nature of human altruism. Nature 425, 785-791. ( 10.1038/nature02043) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henrich J, et al. 2005. “Economic man” in cross-cultural perspective: behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies. Behav. Brain Sci. 28, 795-815; discussion 815–855. ( 10.1017/S0140525X05000142) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynn M, Brewster ZW. 2020. The tipping behavior and motives of US travelers abroad: affected by host nations' tipping norms? J. Travel Res. 59, 993-1007. ( 10.1177/0047287519875820) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frey BS, Torgler B. 2007. Tax morale and conditional cooperation. J. Comp. Econ. 35, 136-159. ( 10.1016/j.jce.2006.10.006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czajkowski M, Zagorska K, Hanley N. 2019. Social norm nudging and preferences for household recycling. Resour. Energy Econ. 58, 101110. ( 10.1016/j.reseneeco.2019.07.004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang TT, Mukhopadhyay A, Patrick VM. 2017. Getting consumers to recycle NOW! When and why cuteness appeals influence prosocial and sustainable behavior. J. Public Policy Mark. 36, 269-283. ( 10.1509/jppm.16.089) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tarasuk V, Eakin JA. 2005. Food assistance through “surplus” food: insights from an ethnographic study of food bank work. Agric. Hum. Values 22, 177-186. ( 10.1007/s10460-004-8277-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lacetera N, Macis M, Slonim R. 2013. Economic rewards to motivate blood donations. Science 340, 927-928. ( 10.1126/science.1232280) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rand DG, Epstein ZG. 2014. Risking your life without a second thought: intuitive decision-making and extreme altruism. PLoS ONE 9, e109587. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0109687) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engel C. 2011. Dictator games: a meta study. Exp. Econ. 14, 583-610. ( 10.1007/s10683-011-9283-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berg J, Dickhaut J, Mccabe K. 1995. Trust, reciprocity, and social-history. Games Econ. Behav. 10, 122-142. ( 10.1006/game.1995.1027) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guth W, Schmittberger R, Schwarze B. 1982. An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 3, 367-388. ( 10.1016/0167-2681(82)90011-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gintis H, Bowles S, Boyd R, Fehr E. 2003. Explaining altruistic behavior in humans. Evol. Hum. Behav. 24, 153-172. ( 10.1016/S1090-5138(02)00157-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fehr E, Henrich J. 2003. Is strong reciprocity a maladaptation? On the evolutionary foundations of human altruism. In Genetic and cultural evolution of cooperation (ed. Hammerstein P), pp. 55-82. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raihani NJ, Bshary R. 2015. Why humans might help strangers. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 9, 39. ( 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00039) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henrich J, Boyd R. 2001. Why people punish defectors: weak conformist transmission can stabilize costly enforcement of norms in cooperative dilemmas. J. Theor. Biol. 208, 79-89. ( 10.1006/jtbi.2000.2202) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henrich J. 2004. Cultural group selection, coevolutionary processes and large-scale cooperation. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 53, 3-35. ( 10.1016/S0167-2681(03)00094-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rustagi D, Engel S, Kosfeld M. 2010. Conditional cooperation and costly monitoring explain success in forest commons management. Science 330, 961-965. ( 10.1126/science.1193649) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chudek M, Henrich J. 2011. Culture-gene coevolution, norm-psychology and the emergence of human prosociality. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15, 218-226. ( 10.1016/j.tics.2011.03.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richerson PJ, Henrich J. 2012. Tribal social instincts and the cultural evolution of institutions to solve collective action problems. Cliodynamics 3, 38-80. ( 10.21237/C7CLIO3112453) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richerson P, et al. 2016. Cultural group selection plays an essential role in explaining human cooperation: a sketch of the evidence. Behav. Brain Sci. 39, e30. ( 10.1017/S0140525X1400106X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Purzycki BG, Apicella C, Atkinson QD, Cohen E, McNamara RA, Willard AK, Xygalatas D, Norenzayan A, Henrich J. 2016. Moralistic gods, supernatural punishment and the expansion of human sociality. Nature 530, 327-330. ( 10.1038/nature16980) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Apicella C, Silk JB. 2019. The evolution of human cooperation. Curr. Biol. 29, R447-R450. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2019.03.036) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Handley C, Mathew S. 2020. Human large-scale cooperation as a product of competition between cultural groups. Nat. Commun. 11, 702. ( 10.1038/s41467-020-14416-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henrich J, Muthukrishna M. 2021. The origins and psychology of human cooperation. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 72, 207-240. ( 10.1146/annurev-psych-081920-042106) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith D. 2020. Cultural group selection and human cooperation: a conceptual and empirical review. Evol. Hum. Sci. 2, e2. ( 10.1017/ehs.2020.2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isaac RM, Walker JM. 1988. Communication and free-riding behavior: the voluntary contribution mechanism. Econ. Inq. 26, 585-608. ( 10.1111/j.1465-7295.1988.tb01519.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isaac RM, Walker JM. 1988. Group-size effects in public-goods provision: the voluntary contributions mechanism. Q. J. Econ. 103, 179-199. ( 10.2307/1882648) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ledyard J. 1995. Public goods: a survey of experimental research. In Handbook of experimental economics (eds Kagel JH, Roth AE), pp. 253-279. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaudhuri A. 2011. Sustaining cooperation in laboratory public goods experiments: a selective survey of the literature. Exp. Econ. 14, 47-83. ( 10.1007/s10683-010-9257-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burton-Chellew MN, West SA. 2021. Payoff-based learning best explains the rate of decline in cooperation across 237 public-goods games. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 1330-1338. ( 10.1038/s41562-021-01107-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fischbacher U, Gachter S, Fehr E. 2001. Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Econ. Lett. 71, 397-404. ( 10.1016/S0165-1765(01)00394-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carpenter JP. 2004. When in Rome: conformity and the provision of public goods. J. Socio-Econ. 33, 395-408. ( 10.1016/j.socec.2004.04.009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gachter S, Thoni C. 2005. Social learning and voluntary cooperation among like-minded people. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 3, 303-314. ( 10.1162/jeea.2005.3.2-3.303) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fischbacher U, Gächter S, Preferences S. 2010. Social preferences, beliefs, and the dynamics of free riding in public goods experiments. Am. Econ. Rev. 100, 541-556. ( 10.1257/aer.100.1.541) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Apicella CL, Marlowe FW, Fowler JH, Christakis NA. 2012. Social networks and cooperation in hunter-gatherers. Nature 481, 497-U109. ( 10.1038/nature10736) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith KM, Larroucau T, Mabulla IA, Apicella CL. 2018. Hunter-gatherers maintain assortativity in cooperation despite high levels of residential change and mixing. Curr. Biol. 28, 3152-3157.e4. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.064) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fehr E, Schurtenberger I. 2018. Normative foundations of human cooperation. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 458-468. ( 10.1038/s41562-018-0385-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burton-Chellew MN, West SA. 2013. Prosocial preferences do not explain human cooperation in public-goods games. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 216-221. ( 10.1073/pnas.1210960110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burton-Chellew MN, Nax HH, West SA. 2015. Payoff based learning explains the decline in cooperation in human public goods games. Proc. R. Soc. B 282, 20142678. ( 10.1098/rspb.2014.2678) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burton-Chellew MN, El Mouden C, West SA. 2016. Conditional cooperation and confusion in public-goods experiments. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 1291-1296. ( 10.1073/pnas.1509740113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fowler JH, Christakis NA. 2010. Cooperative behavior cascades in human social networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 5334-5338. ( 10.1073/pnas.0913149107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frey BS, Meier S. 2004. Pro-social behavior in a natural setting. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 54, 65-88. ( 10.1016/j.jebo.2003.10.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nook EC, Ong DC, Morelli SA, Mitchell JP, Zaki J. 2016. Prosocial conformity: prosocial norms generalize across behavior and empathy. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 42, 1045-1062. ( 10.1177/0146167216649932) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kocher MG, Cherry T, Kroll S, Netzer RJ, Sutter M. 2008. Conditional cooperation on three continents. Econ. Lett. 101, 175-178. ( 10.1016/j.econlet.2008.07.015) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herrmann B, Thoni C. 2009. Measuring conditional cooperation: a replication study in Russia. Exp. Econ. 12, 87-92. ( 10.1007/s10683-008-9197-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Molleman L, van den Berg P, Weissing FJ. 2014. Consistent individual differences in human social learning strategies. Nat. Commun. 5, 1-9. ( 10.1038/ncomms4570) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van den Berg P, Molleman L, Weissing FJ. 2015. Focus on the success of others leads to selfish behavior. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 2912-2917. ( 10.1073/pnas.1417203112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burton-Chellew MN, El Mouden C, West SA. 2017. Social learning and the demise of costly cooperation in humans. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 20170067. ( 10.1098/rspb.2017.0067) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lamba S. 2014. Social learning in cooperative dilemmas. Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20140417. ( 10.1098/rspb.2014.0417) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bardsley N, Sausgruber R. 2005. Conformity and reciprocity in public good provision. J. Econ. Psychol. 26, 664-681. ( 10.1016/j.joep.2005.02.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schroeder KB, Pepper GV, Nettle D. 2014. Local norms of cheating and the cultural evolution of crime and punishment: a study of two urban neighborhoods. PeerJ 2, e450. ( 10.7717/peerj.450) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schotter A, Sopher B. 2003. Social learning and coordination conventions in intergenerational games: an experimental study. J. Political Econ. 111, 498-529. ( 10.1086/374187) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chaudhuri A, Graziano S, Maitra P. 2006. Social learning and norms in a public goods experiment with inter-generational advice. Rev. Econ. Stud. 73, 357-380. ( 10.1111/j.1467-937X.2006.0379.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li X, Molleman L, van Dolder D. 2021. Do descriptive social norms drive peer punishment? Conditional punishment strategies and their impact on cooperation. Evol. Hum. Behav. 42, 469-479. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2021.04.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fischbacher U. 2007, z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp. Econ. 10, 171-178. ( 10.1007/s10683-006-9159-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Greiner B. 2015. Subject pool recruitment procedures: organizing experiments with ORSEE. J. Econ. Sci. Assoc. 1, 114-125. ( 10.1007/s40881-015-0004-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McElreath R, Bell AV, Efferson C, Lubell M, Richerson PJ, Waring T. 2008. Beyond existence and aiming outside the laboratory: estimating frequency-dependent and pay-off-biased social learning strategies. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 363, 3515-3528. ( 10.1098/rstb.2008.0131) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Trivers RL. 1971. Evolution of reciprocal altruism. Q. Rev. Biol. 46, 35-57. ( 10.1086/406755) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barclay P. 2006. Reputational benefits for altruistic punishment. Evol. Hum. Behav. 27, 325-344. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2006.01.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barclay P, Willer R. 2007. Partner choice creates competitive altruism in humans. Proc. R. Soc. B 274, 749-753. ( 10.1098/rspb.2006.0209) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burton-Chellew MN, El Mouden C, West SA. 2017. Evidence for strategic cooperation in humans. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 0170689. ( 10.1098/rspb.2017.0689) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nikiforakis N. 2008. Punishment and counter-punishment in public good games: can we really govern ourselves? J. Public Econ. 92, 91-112. ( 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2007.04.008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Strobel A, Zimmermann J, Schmitz A, Reuter M, Lis S, Windmann S, Kirsch P. 2011. Beyond revenge: neural and genetic bases of altruistic punishment. Neuroimage 54, 671-680. ( 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.051) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burton-Chellew MN, Guérin C. 2021. Decoupling cooperation and punishment in humans shows that punishment is not an altruistic trait. Proc. R. Soc. B 288, 20211611. ( 10.1098/rspb.2021.1611) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burton-Chellew MN, D'Amico V. 2021. Data and files for: A preference to learn from successful rather than common behaviours in human social dilemmas. See https://osf.io/b6msn/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Hertz U. 2021. Learning how to behave: cognitive learning processes account for asymmetries in adaptation to social norms. Proc. R. Soc. B 288, 20210293. ( 10.1098/rspb.2021.0293) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Raihani NJ, McAuliffe K. 2014. Dictator game giving: the importance of descriptive versus injunctive norms. PLoS ONE 9, e113826. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0113826) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thoni C, Volk S. 2018. Conditional cooperation: review and refinement. Econ. Lett. 171, 37-40. ( 10.1016/j.econlet.2018.06.022) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kirchkamp O. 2019. Importing z-Tree data into R. J. Behav. Exp. Finance 22, 1-2. ( 10.1016/j.jbef.2018.11.008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Singh M, et al. 2021. Beyond social learning. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 376, 20200050. ( 10.1098/rstb.2020.0050) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gunnthorsdottir A, Houser D, McCabe K. 2007. Disposition, history and contributions in public goods experiments. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 62, 304-315. ( 10.1016/j.jebo.2005.03.008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Allott S. 1974. Alcuin of York, c. A.D. 732 to 804: his life and letters. York, UK: William Sessions Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Acerbi A, Ghirlanda S, Enquist M. 2012. The logic of fashion cycles. PLoS ONE 7, e32541. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0032541) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Agerstrom J, Carlsson R, Nicklasson L, Guntell L. 2016. Using descriptive social norms to increase charitable giving: the power of local norms. J. Econ. Psychol. 52, 147-153. ( 10.1016/j.joep.2015.12.007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lehmann L, Foster KR, Borenstein E, Feldman MW. 2008. Social and individual learning of helping in humans and other species. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 664-671. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2008.07.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Andre JB, Morin O. 2011. Questioning the cultural evolution of altruism. J. Evol. Biol. 24, 2531-2542. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02398.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.El Mouden C, André JB, Morin O, Nettle D. 2014. Cultural transmission and the evolution of human behaviour: a general approach based on the Price equation. J. Evol. Biol. 27, 231-241. ( 10.1111/jeb.12296) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Henrich J, Gil-White FJ. 2001. The evolution of prestige: freely conferred deference as a mechanism for enhancing the benefits of cultural transmission. Evol. Hum. Behav. 22, 165-196. ( 10.1016/S1090-5138(00)00071-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Henrich J, Chudek M, Boyd R. 2015. The big man mechanism: how prestige fosters cooperation and creates prosocial leaders. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 370, 20150013. ( 10.1098/rstb.2015.0013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cullis JG, Lewis A. 1997. Why people pay taxes: from a conventional economic model to a model of social convention. J. Econ. Psychol. 18, 305-321. ( 10.1016/S0167-4870(97)00010-X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Myles G, Naylor R. 1996. A model of tax evasion with group conformity and social customs. Eur. J. Political Econ. 12, 49-66. ( 10.1016/0176-2680(95)00037-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Traxler C. 2010. Social norms and conditional cooperative taxpayers. Eur. J. Political Econ. 26, 89-103. ( 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2009.11.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Glowacki L, Molleman L. 2017. Subsistence styles shape human social learning strategies. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1, 1-5. ( 10.1038/s41562-017-0098) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Molleman L, Gachter S. 2018. Societal background influences social learning in cooperative decision making. Evol. Hum. Behav. 39, 547-555. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2018.05.007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.De Cremer D, Van Vugt M. 1999. Social identification effects in social dilemmas: a transformation of motives. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 29, 871-893. () [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Heintz C. 2005. The ecological rationality of strategic cognition. Behav. Brain Sci. 28, 825. ( 10.1017/S0140525X05320140) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brosnan SF, Salwiczek L, Bshary R. 2010. The interplay of cognition and cooperation. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 2699-2710. ( 10.1098/rstb.2010.0154) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Barclay P, Krupp DB. 2016. The burden of proof for a cultural group selection account. Behav. Brain Sci. 39, e33. ( 10.1017/S0140525X15000060) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Morin O. 2016. Reasons to be fussy about cultural evolution. Biol. Philos. 31, 447-458. ( 10.1007/s10539-016-9516-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McAuliffe WHB, Burton-Chellew MN, McCullough ME. 2019. Cooperation and learning in unfamiliar situations. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 28, 436-440. ( 10.1177/0963721419848673) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gachter S, Renner E. 2018. Leaders as role models and 'belief managers' in social dilemmas. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 154, 321-334. ( 10.1016/j.jebo.2018.08.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Berger J. 2021. Social tipping interventions can promote the diffusion or decay of sustainable consumption norms in the field. Evidence from a quasi-experimental intervention study. Sustainability 13, 3529. ( 10.3390/su13063529) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Burton-Chellew MN, D'Amico V. 2021. Data and files for: A preference to learn from successful rather than common behaviours in human social dilemmas. See https://osf.io/b6msn/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data can be found at https://osf.io/b6msn/ [67].