Abstract

This study charts the use of the National Institutes of Health’s diversity supplements, grant enhancement awards designed to provide research opportunities to individuals from underrepresented racial or ethnic groups, since the program’s inception in 1989.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) and US Congress have cited the lack of diversity in the biomedical workforce as a serious concern.1,2 In 2020, only 2% and 5% of NIH R01 grants were awarded to Black and Latinx scientists, respectively.3 To help address this issue, in 1989, the NIH introduced diversity supplements,1 which award additional funding to existing grants whereby a principal investigator can provide research opportunities, training, and mentorship to an individual underrepresented in research at any career stage.2 Diversity supplements are offered by every NIH institute and are available for most research and program or project center grants.2

Despite the potential of diversity supplements to bolster diversity in biomedicine, there is little information to understand the extent to which these supplements have been used and whether use has changed over time.

Methods

To investigate recent trends in their use, we analyzed diversity supplements administered by NIH institutes from 2005 through 2020. We examined supplements associated with R01 grants because R01 grants have been eligible for diversity supplements since the program’s introduction and are the most common NIH investigator-initiated research project mechanism.

We determined the number of diversity supplements by fiscal year, the administering NIH institute, and the principal investigator via the public NIH RePORTER tool. We calculated the annual growth rate for the number of diversity supplements. Supplements were included in the fiscal year in which they were awarded. Analyses were performed using R version 4.1.1 and RStudio. The Yale Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt.

Results

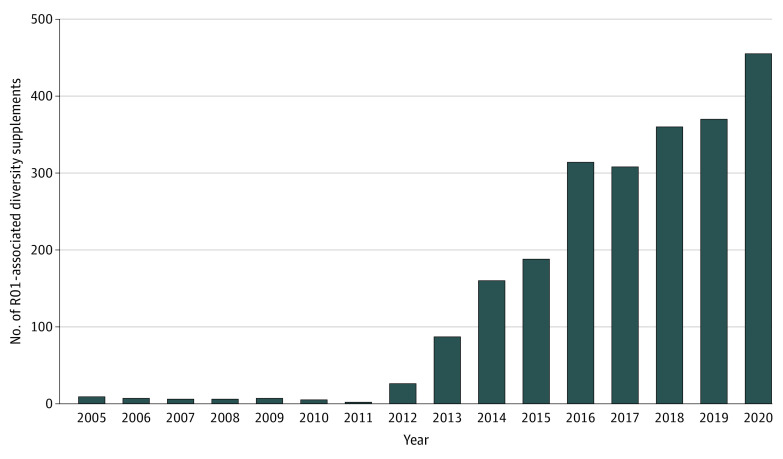

From 2005 through 2010, few diversity supplements were awarded (Figure 1). From 2011 through 2020, the number of new R01-associated diversity supplements grew from 2 to 455, representing an annual growth rate of 82.8%. From 2005 through 2020, NIH institutes funded 93 285 R01 grants, of which 2145 (2.3%) received at least 1 diversity supplement and 149 (0.16%) received 2 or more supplements. Since 2005, there have been 2084 principal investigators who received R01-associated diversity supplements; 67 (3.2%) received 2 supplements for distinct R01 grants, 8 (0.38%) received 3, and 1 (0.05%) received 4.

Figure 1. Number of New R01-Associated Diversity Supplements by Fiscal Year.

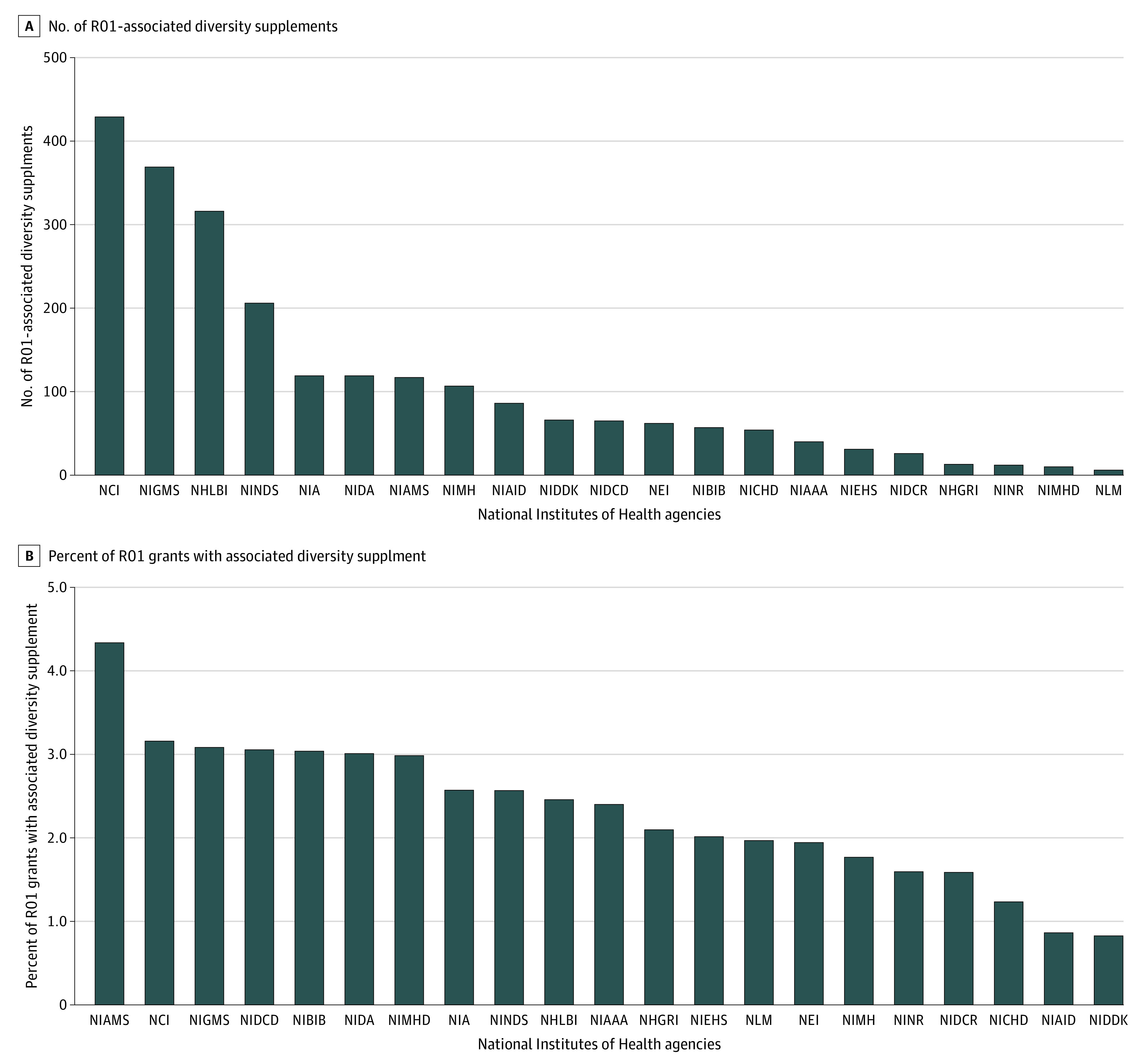

Since 2005, the National Cancer Institute awarded 429 diversity supplements (R01 grants with at least 1 supplement, 3.2%), the highest number of any NIH institute (Figure 2A). The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases administered the highest percentage of R01 grants with a diversity supplement, 4.3% with 117 supplements. The National Library of Medicine awarded 6 grants with diversity supplements (R01 grants with at least 1 supplement, 2.0%), the lowest number. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases administered the lowest percentage (0.83%) with 66 supplements (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Number and Percentage of New R01-Associated Diversity Supplements by Administering National Institutes of Health Agency (2005-2020).

NCI indicates National Cancer Institute; NEI, National Eye Institute; NHGRI, National Human Genome Research Institute; NHLBI, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; NIA, National Institute on Aging; NIAAA, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; NIAID, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; NIAMS, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; NIBIB, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; NICHD, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; NIDA, National Institute on Drug Abuse; NIDCD, National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders; NIDCR, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; NIDDK, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; NIEHS, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; NIGMS, National Institute of General Medical Sciences; NIMH, National Institute of Mental Health; NIMHD, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; NINDS, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; NINR, National Institute of Nursing Research; NLM, National Library of Medicine.

Discussion

Between 2005 and 2020, the number of diversity supplements increased, with variation across NIH institutes. This growth coincided with a period of heightened awareness concerning a lack of diversity in the biomedical workforce as demonstrated by a 2011 study by Ginther et al4 highlighting racial disparities in NIH funding, a 2012 report from the NIH5 investigating diversity in the biomedical research workforce, and the appointment of the NIH’s inaugural chief officer for Scientific Workforce Diversity in 2014.

Nevertheless, in 2020 only 4.5% of active R01 grants had ever received a diversity supplement. This suggests that diversity supplements remain an infrequently awarded tool to promote diversity in the biomedical workforce.

This study is limited by the unavailability of data from NIH institutes detailing the number of applications received for, budget reserved for, duration of, and career stage of recipients of diversity supplements. Although more than 70% of diversity supplements listed in the NIH RePORTER database are associated with R01 grants, some institutes may have awarded diversity supplements to grant types not accounted for in this study.2

Diversity supplements have the potential to increase representation of historically underrepresented groups in research. Yet many researchers report limited knowledge about the diversity supplement program.6 Future opportunities for programmatic growth include increasing diversity supplement program awareness and expanding NIH funding.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Associate Editor.

References

- 1.National Institutes of Health . Initiatives for underrepresented minorities in biomedical research. Published April 21, 1989. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/historical/1989_04_21_Vol_18_No_14.pdf

- 2.National Institutes of Health . Research supplements to promote diversity in health-related research. Posted May 29, 2020. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/pa-20-222.html

- 3.National Institutes of Health . Racial disparities in NIH funding. Updated May 25, 2021. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://diversity.nih.gov/building-evidence/racial-disparities-nih-funding

- 4.Ginther DK, Schaffer WT, Schnell J, et al. Race, ethnicity, and NIH research awards. Science. 2011;333(6045):1015-1019. doi: 10.1126/science.1196783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Advisory Committee to the Director Working Group on Diversity in the Biomedical Research Workforce . Draft report of the Advisory Committee to the Director Working Group on Diversity in the Biomedical Research Workforce. National Institutes of Health. Published June 13, 2012. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://acd.od.nih.gov/documents/reports/DiversityBiomedicalResearchWorkforceReport.pdf

- 6.Preis SR, Sarfaty SC, Tepperberg S, Torres A, Walkey A; 2019-2020 BUMC Mid-Career Faculty Leadership Program Project Group . NIH diversity supplements and research faculty diversity. Presented at Boston University; May 22, 2020; Boston, Massachusetts. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://www.bumc.bu.edu/facdev-medicine/files/2020/05/NIH-Diversity-Supplement-Presentation.pdf