Abstract

Objectives:

The purpose of this systematic review was to answer the focus question: “Could the gray values (GVs) from CBCT (cone beam computed tomography) be converted to Hounsfield units (HUs) in multidetector computed tomography (MDCT)?”

Methods:

The included studies try to answer the research question according to the PICO strategy. Studies were gathered by searching several electronic databases and partial grey literature up to January 2021 without language or time restrictions. The methodological assessment of the studies was performed using The Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT) for in vitro studies and the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) for in vivo studies. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE system) instrument was applied to assess the level of evidence across the studies.

Results:

2710 articles were obtained in Phase 1, and 623 citations remained after removing duplicates. Only three studies were included in this review using a two-phase selection process and after applying the eligibility criteria. All studies were methodologically acceptable, although in general terms with low risks of bias. There are some included studies with quite low and limited evidence estimations and recommendation forces; evidencing the need for clinical studies with diagnostic capacity to support its use.

Conclusions:

This systematic review demonstrated that the GVs from CBCT cannot be converted to HUs due to the lack of clinical studies with diagnostic capacity to support its use. However, it is evidenced that three conversion steps (equipment calibration, prediction equation models, and a standard formula (converting GVs to HUs)) are needed to obtain pseudo Hounsfield values instead of only obtaining them from a regression or directly from the software.

Keywords: Bone density, Cone-beam computed tomography, systematic review, diagnostic imaging, Hounsfield unit, Multidetector Computed Tomography

Introduction

In dentistry, there are several reasons to justify the demand for valid tools to assess bone mineral density (BMD). It is important for preoperative planning of implants and temporary anchorage device placements,1–3 so that height, width, and the distance to other anatomical structures such as the sinus region or the mandibular canal can be assessed. Quality and quantity of the receptor bone are required due to its influence on primary stability and success of implants and orthodontic temporary anchorage devices.3,4 Furthermore, identifying the bone degenerative processes of the jaws, temporomandibular joints,5 and systemic conditions help the clinicians in the diagnosis and treatment planning of patients. The reference standard for evaluating BMD is multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) using the Hounsfield Unit (HU), which is the coefficient of X-ray attenuation for bone (absolute density).6,7 Nowadays, cone-beam CT (CBCT) is increasingly compared to MDCT in dentistry to assess mineralized tissues because it provides adequate image quality. In addition, CBCT is associated with lower radiation exposure doses, lower costs, good spatial resolutions, gray density ranges and contrasts, as well as a good pixel/noise ratio compared to MDCT.8 However, due to the associated artifacts, the lack of standardization of CBCT scanners and the acquisition parameters, it is uncertain that gray values (GVs) could accurately represent HUs.9

HUs are defined as linear transformations of measured X-ray attenuation coefficients of a material with reference to water. Some studies have mentioned the possibility of obtaining HUs through CBCT because HUs can be calculated using a conversion equation, for example a prediction equation model and standard conversion formula.10–17 This way, the standard conversion formula used to calculate HUs for any material is (HU material = material -

Nevertheless, other studies do not support the ability of converting GVs to HUs due to the CBCT acquisition mode, stating that the BMD obtained through CBCT does not correlate to MDCT.9,18–21 There are crucial differences between MDCT and CBCT, which complicates the use of quantitative GVs that are inherently associated with this technique (i.e., the limited field size, relatively high amount of scattered radiation and limitations of currently applied reconstruction algorithms).22 There is contradictory information about whether CBCT can be used for BMD similar to HUs in MDCT.9 Thus, obtaining HUs from gray levels or voxel values is controversial using CBCT and is insufficiently studied.9,22 Therefore, the objective of this systematic review was to answer a focused question: “Could the GVs from CBCT be converted to HUs in MDCT?”

Methods

This systematic review was done according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: PRISMA Statement.23

Study design

This study involved in vitro (phantoms or dry bones) and in vivo (patients) studies that evaluate GVs from CBCT and HUs from MDCT according to different conversion formulas. The included studies should help answer the research question according to the PICO (population, intervention, comparison, and outcome) strategy as follows:

Population: CBCT and MDCT images; Intervention: GVs from CBCT; Comparison: HUs from MDCT; Outcome: Prediction equation models to convert GVs from CBCT to HUs.24

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies in which the primary objective was to assess reliability of CBCT voxel GV measurements using HUs derived from MDCT were included. It was essential that the eligible studies demonstrated the statistical prediction equation model and linear regression for the conversion formula. Also, the MDCT should be taken at the same region of interest (ROI) as the CBCT scans. No language or time restrictions were applied.

The following studies were excluded: studies that used other imaging technique devices (micro-CT, Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance); reviews, personal opinions, conference abstracts and letters; experiments in animal models; and studies without reference standards. An additional eligibility criterion was added in Phase 2 in which the studies that did not present a conversion formula were not eligible.

Search strategy

Electronic search strategies were applied in PubMed, Cochrane, EMBASE, LILACS and Ovid MEDLINE databases up to May 2020. No date or language restrictions were applied. (Supplementary Material 1). Also, journals related to the topic, gray literature (clinical trials.gov and google scholar) and the references of included studies were screened to identify any missed publications. Search results were collected, and duplicate references were removed. The search was updated in all databases until 10 January 2021, and no additional studies were found for inclusion in this review.

Study selection

A two-phase selection process was developed according to inclusion criteria. In Phase 1, two authors independently selected articles by title and abstract. In Phase 2, the same authors reviewed the full text of all potential articles to apply the eligibility criteria. Disagreements were resolved by consensus with a third author. The final selection was always based on the full text of the publication and discussion between evaluators.

Data collection process

One author extracted the required data from the included articles and a second author reviewed all the retrieved information. The key features were crosschecked, with a one-week interval, by the same authors. Again, disagreements between them were resolved by consensus with the third author. Using a standardized template, the descriptive characteristics of included studies and their key features such as author, year, and country; sample characteristics (scanned structure, index text-CBCT, reference standard-MDCT); ROI; the intervention characteristics (method of conversion of GVs to HUs) and the specific results related to our research question were recorded.

Risk of bias (RoB) in individual studies

The RoB of selected studies was evaluated using the Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT)25 for in vitro studies. The Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2)26 evaluated the in vivo studies. Previously, an author with experience in RoB tools trained the evaluators in two rounds. In both rounds, randomized articles were independently analysed and a favourable level of agreement value of 0.9 was reached. The authors applied the tools for the rest of the studies independently and, if any disagreement was found, items were discussed between co-authors

The OHAT evaluates randomization, allocation concealment, experimental condition, blinding, incomplete data, exposure characterization, outcome assessment, reporting and other biases related to the methodological structure. OHAT scores were definitely low RoB (++), probably low RoB (+), probably high RoB (-/NR), definitely high RoB (--). QUADAS-2 assesses patient selection, index test, reference standard, flow and timing, as well as concerns regarding applicability. Guiding questions within every domain were scored as yes, no or unclear and topic conclusions and applicability were registered as low, high or unclear RoB.

Summary measurements

The capacity of CBCT scans to identify BMD according to conversion formulas was considered as the primary outcome. Any type of outcome measurement was considered in this review (categorical and continuous variables). No meta-analysis was performed due to heterogeneity of the data.

Level of evidence

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE system) instrument evaluates the quality of evidence.27–30 Two authors rated the quality of the evidence as well as the strength of the recommendations according to the following aspects: study design, RoB, consistency, directness, precision, publication bias and other aspects reported by studies included in this systematic review.29,30 The quality of the evidence was characterized as high, moderate, low or very low. The GRADE was assessed using tools from their website http://gradeproorg.

Results

Study selection

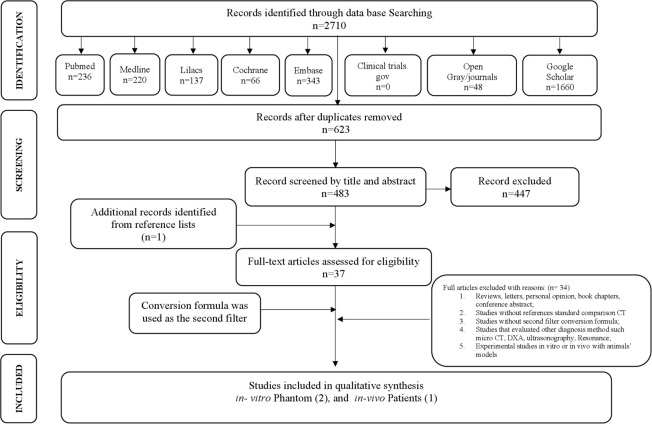

In Phase 1, 2710 articles were obtained by title and abstract. After removing duplicates, 623 citations remained. Following a detailed evaluation of abstracts, 483 articles were selected for Phase 2. A manual search was performed on Google Scholar and Gray literature. One study was identified from the reference lists and was included in this review. Finally, after full-text reading, 37 articles were assessed for eligibility and 34 studies were excluded due to multiple reasons specified in Supplementary Material 2. Therefore, three studies were finally included for qualitative synthesis. The PRISMA flow diagram detailing the process of identification, inclusion and exclusion of the studies is shown in Figure 1.23

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of the Literature

Study characteristics

The three included studies evaluated whether the GVs could be compared to HUs according to prediction equation models and conversion formulas.14,17,31 In total, this systematic review assessed 77 scans, in vitro studies were done using phantoms14,31 and in vivo using patient scans.17 In vitro studies described different types of phantoms, ROIs and methods of conversion and in vivo studies included 61 patients with CBCT scans and attenuation coefficients from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) (Table 1).14,17,31 In an attempt to gather missing information and to retrieve the formula methodologies, we tried to contact the corresponding authors of the included articles but were not successful.

Table 1.

In vitro and in vivo studies

| Study Characteristics | Results | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Year and Country | Sample | Index test | References Standard- Gold Standard | ROI | Method of convertion GV to HU | Results | Main Conclusion |

| Mah et al., 2010 USA |

In vitro 3D dental phantom with eight different materials |

11 CBCT scanners - 11 settingss: Asahi Alphard 3030; Hitachi CB MercuRay; I-CAT Classic; I-CAT Next Generation; Iluma ; Morita Accuitomo FPD; Morita Veraview Epochs; NewTom VG; Planmeca ProMax 3D; Galileos and Scanora 3D. | Aquilon 64 slice CT: 120 kV, 300 mA. Briliance 64 CT: 120 kV, 300 mA | Central region within each of 8 materials in the 3D phantom. |

|

R2 = 0.999 Highest correlation at effective bean energy 63 keV | HU can be derived from the GV from CBCT scanners using linear attenuation coefficients as an intermediate step. |

| Magill et al., 2018 USA |

In vitro cylindrical standardized phantom - five different materials: air, polyethylene, acrylic, water and bone-equivalents. |

3 CBCT Scanners: CS9300 - Matrix: 557 × 557, Pixel Size (μm): 300, Slice Thickness (mm): 0.3, 90 kVp; 3D Accuitomo - Matrix: 512 × 512, Pixel Size (μm): 250, Slice Thickness (mm): 1.0, 90 kVp; ProMax 3D Mid - Matrix: 500 × 500, Pixel Size (μm): 400, Slice Thickness (mm): 0.4, 90 kVp. | Phantom specifications for materials in the CT number accuracy module published by the ACR at 120 kVp. | For each image set, ROIs were drawn in the five phantom materials in consecutive axial slices. |

|

All material HU values for the modified technique fell within 2.4 σ, for the manufacturer-reported HU values ranged from 2.6 to 13.5 σ | The study was able to formulate a valid conversion technique that can provide HU readings for three CBCT units. |

| Reeves et al., 2012 USA | In vivo n = 61 patient scans | Asahi Alphard 3030 (31 scans): 80kV, 5mA, 17 s, three exposure mode (200 × 178 mm FOV, 0.39 mm vs / 154 × 154 mm FOV, 0.3 mm vs / 102 × 102 mm FOV, 0.2 mm vs ). ProMaxTM 3D (30 scans) - five settings: 80kV- 84 kV / 8 mA - 14mA / 18 s / 0.32 mm vs - 0.16 mm vs / 80 × 80 mm FOV. | Linear attenuation coefficients derived from NIST tables of X-ray mass attenuation coefficients and mass energy absorption coefficients for the elemental components in each material. | Average grey levels within a square, 10 × 10 pixel, for five five materials. ROI with the highest grey levels was chosen. |

|

ProMax 3D 60keV: R2 = 0.9982 ProMax 3D 70keV: R2 = 0.9987 ProMax 3D 80keV: R2 = 0.997 |

A method for deriving Hounsfield units from grey levels in CBCT. |

kV, tube voltage; mA, milliampere; R2, coefficient of determination; HU, Hounsfield unit; GV, grey values; kVp, peak kilovoltage; ACR, American College of Radiology; ROI, region of interest; σ, standard deviation; s, scan time; FOV, field of view; keV, effective energy kilovoltage.

Results of individual studies and synthesis of results

In vitro studies

The in vitro studies converted CBCT gray values into HUs using a calculated linear attenuation coefficient.14 They were derived from a linear regression model to obtain the best linear fit (effective energy “63 keV”), a result of plotting attenuation coefficients of eight materials provided by NIST and two MDCT scanners against the GVs of these materials obtained from 11 CBCT scanners. They found a linear relationship between GVs and CT numbers for each of the materials (R2 = 0.9999). This linear regression model was used to obtain attenuation coefficients and calculate HUs. The calculated attenuation coefficients were transformed into HUs according to a standard formula.

A half value layer (HVL) was used for each X-ray tube to determine the average beam energy for each scanner (46.7 to 51.7 keV) and obtain the best R2 value.31 A linear regression model was fit, and the resulting values of linear attenuation coefficients were converted to CT numbers using the standard conversion formula. This study shows the consistency of the water value (0 to 1 HU) for all three CBCT scanners.

In vivo study

The in vivo study17 used the same conversion methodology (GVs to HUs) as the in vitro study.14 They found the difference between the calculated and actual HUs to be less than 3%, whereas the relationship between GVs and HUs was defined as linear. The Asahi Alphard 3030 (Belmont Takara, Kyoto, Japan) CBCT scan showed calculated HUs for outer bone equivalent material at 1465.9 HUs and inner bone equivalent material at 254.7 HUs using 70 keV; while the Planmeca ProMaxTM 3D (Planmeca, Helsinki, Finland) CBCT scan showed calculated HUs for outer bone equivalent material at 124.2 HUs and inner bone equivalent material at 251.9 HUs at the same keV. To get those results, linear regression studies were developed for different keVs (Table 2). At 70 keV, the linear regression equation was , showing a strong correlation (R2 = 0.9987). Then, the standard conversion formula was applied. Table 2 shows the specific formula applied for each selected study.

Table 2.

Regression and conversion formulas

| Author, Year | Effective energy | Conversion Formulas |

|---|---|---|

| Mah, et al, 2010 | 63 keV | ; |

| Magill, et al, 2018 | 46.7 kVp 48.4 kVp 51.7 kVp | ; |

| Reeves, et al, 2012 | 70 keV | ; |

Summary of evidence

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry,32 quantitative CT,33 micro-CT34 and MDCT35 are methods used to evaluate BMD in which HUs are used as the reference standard. Some studies have mentioned the possibility of obtaining HUs through CBCTs, due to a possible linear relationship between GVs and the attenuation coefficients of CBCT scanners. This leads to the possibility of converting GVs from CBCTs to CT numbers and then in HUs with a standard conversion formula.14–17 However, other studies concluded that the HUs derived from CBCTs are not identical.9,18–22 As the literature is scarce and controversial on this subject to date, only one systematic review has been published regarding the capability of CBCTs to identify low-BMD patients, suggesting the potential of CBCT for this purpose.35

Variability of CBCT scanners

One of the disadvantages of most CBCT machines is a lack of standardization. Like snowflakes and fingerprints, no two CBCT models are the same, demonstrating essential differences in terms of exposure, hardware and reconstruction.20 One study14 used 12 different CBCT and 2 MDCT scanners. Whereas another study31 used three different CBCT scanners and CT numbers from the American College of Radiology and another study17 used 2 CBCT scanners and CT numbers from NIST. In another study,36 the researchers found that the HUs values obtained from CBCTs differed between scanner models, settings and types of software used. Therefore, the GV corrections are typically only applicable for each device model.

Tube voltage

The optimal tube voltage for CBCT imaging of the hard tissues was investigated and found to be between 70 and 120 kVs.37 Different studies showed that the x-tube voltage affects the GVs from CBCT machines; thus, various kVp and mA values were used in the selected studies.14,31 They found that the highest available voltage (i.e., 110 kV) resulted in the highest image quality. Reduction of the mA to a minimally acceptable value followed by reduction of the exposure time affects the reconstructed voxel size for several CBCT models in a pre-set manner. Fast-scan protocols showed equal or slightly better image quality compared to the standard-scan mode. The number of studies assessing the impact of voxel size variation on the diagnostic outcome in CBCT imaging in dentistry is low.38

Size of the field of view (FOV)

The GVs determined in CBCT images are influenced by the FOV size.39 The GVs in CBCTs and MDCTs with the same FOV size were different for all materials and CBCTs showed lower GVs in most of the comparisons. In one study,11 the researchers observed the highest density variability in the smallest FOV scans, whereas large FOV scans had more consistent density values. Another study14 used a small and large water container in which to place the phantom to provide some level of soft tissue. The acrylic/water volume around the object influenced the GVs, since the greater the mass, the smaller the GVs. One study21 found that just as the size of FOV is important, the placement of the ROI in the center of the FOV is also important because it minimizes the variability of results in the measurements.

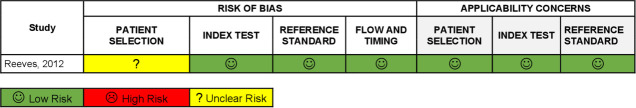

RoB assessment

For the OHAT, the in vitro studies14,31 showed direct evidence of low RoB for all evaluated scopes. The selection of study participants and confounding-modifying variables were not applicable for the in vitro studies (Table 3). The in vivo studies were assessed using QUADAS-2.17 Regarding participant selection, the in vivo study did not clearly report whether randomization was consecutive, or case–control design was not used or whether appropriate exclusions were done. The index and the standard test results showed a low risk for introducing bias and applicability in this domain. Time intervals for both tests were adequate, as well as processing of the results. Study flow charts were reproduced for better understanding of the process and all studies have a low RoB for index tests, reference standards, flow-timing domains and applicability concerns (Figure 2).

Table 3.

In vitro studies risk of bias - OHAT tool

| Randomization | Allocation concealment | Experimental condition | Blinding during study | Incomplete data | Exposure characterization | Outcome assessment | Reporting | Other bias | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study, year | 1.Was the exposure level adequately randomized? | 2.Was allocation to study groups adequately concealed? | 3.Did selection of study participants result in appropriate comparison groups? | 4.Did the study design or analysis account for important confounding and modifying variables? | 5.Were experimental conditions identical across study groups? | 6.Were the researchers blinded to the study? | 7.Were outcome data complete without attrition or exclusion from analysis? | 8.Can we have confidence in the exposure characterization? | 9.Can we be confident in the outcome assessment? | 10.Have all measured results been reported? (“methods” and “results” section of the paper) | 11.Were there no other potential threats to internal validity? |

| Mah et al, 2010 | ++ | ++ | na | na | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Magill et al, 2018 | ++ | ++ | na | na | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

Low risk of bias (++), probably low risk of bias (+), probably high risk of bias (-/NR), definitely high risk of bias (--).

Figure 2.

QUADAS-2 Summary

Level of evidence

Regarding the GRADE tool, the sensitivity and specificity columns were eliminated since these data were not provided (Table 4). GRADE evaluation was assessed for all studies according to guidelines for test accuracy.29,30 However, the studies showed a low RoB and direct evidence from the data. Heterogeneity and imprecise results were obtained since the CBCT and MDCT equipment had independent configurations that made it difficult to compare them. The fact that only one study was done with humans and the others were done with individualized phantoms, influenced an overall very low estimation of the evidence with a limited recommendation force.

Table 4.

Summary of GRADE criteria

| RESULTS | Studies number | Factors that may decrease certainty of evidence | Test accuracy CoE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Sample size, scans) | |||||||

| Risk of biasa | Indirect Evidenceb | Inconsistencyc | Imprecisiond | Publication biase | |||

| In vivo | 1 (61 patients, 61 CBCT scans and attenuation coefficients from Form NIST) | Not serious | Not serious | Very serious | Very serious | publication bias was strongly suspected | ⨁◯◯◯ |

| studies | very strong association | VERY LOW | |||||

| In vitro studies | 2 (2 phantoms, 14 CBCT and 2 MSCT scans) | Not serious | Not serious | Very serious | Very serious | publication bias was strongly suspected | ⨁◯◯◯ |

| very strong association | VERY LOW | ||||||

| Comments | a The evidence was not downgraded because no study had a serious concern regarding risk of bias. | b All studies directly answered the research question. | c Evidence was downgraded due to high results of heterogeneity. Not comparable as they used different tomographic equipment with variable 3D acquisition protocols. | d No Confidence Intervals were reported. Small sample sizes did not clearly show the associated effect. | e There is a possibility that larger future studies could modify results. No upward factors were identified | Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the information. | |

Discussion

There are some benefits for obtaining BMD from CBCT scans, and one of them is to perform an accurate assessment of bone quality for implant surgery since poor bone quality is one of the reasons for implant failure rate increases. In orthodontics, BMD is the one of the references used for placement of miniscrews.40 Maxillofacial surgeons use GVs for differential diagnosis even though HUs should be the tool chosen for this purpose. Studies have found that using GVs for differentiating lesions should be taken with caution because they could show scattered values.41,42 The inability to identify osteonecrosis lesion borders compels surgeons to perform block resections to ensure complete removal of necrotic tissue.42 The capacity to identify and demarcate osteonecrosis lesion borders by analyzing BMD could change the surgical procedure. Nowadays, the assessment of airways to treat obstructive sleep apnea syndrome is where orthodontic research is heading.43–46 Calculated HUs could help to determine airway boundaries for a more accurate airway volume and how they change with treatment such as rapid maxillary expansion, miniscrew anchorage rapid palatal expansion or surgical-assisted rapid maxillary expansion. These are some of the reasons that justify the value of obtaining HUs from CBCTs. Although converted GVs cannot be taken as definitive HU values, a study22 proposed it may be more appropriate to call these values pseudo Hounsfield units.

This systematic review investigated the limited available evidence regarding the capability of converting GVs from CBCTs to HUs in MDCTs. One of the things that caught our attention is that from the 2710 articles initially found, only three articles were included in our study. This denotes the lack of solid scientific evidence related to the subject, and results in the limited understanding of professionals regarding adequate use of CBCTs. Nonetheless, as we have described previously, its clinical use is wide and could be beneficial in various branches of dentistry. There is contradictory information about whether CBCTs can be used for BMD like HUs in MDCTs.9 Thus, obtaining HUs from gray values or voxel values is controversial using CBCTs and is insufficiently studied. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review concerning the capability of converting GVs from CBCTs to HUs.

To calculate HUs, it is necessary to calibrate the scanner against the X-ray absorption of air and water. Also, to determine adequate kilovoltage energy, it is important to calibrate the CBCT. For this reason, linear regressions were performed in all studies to find the best linear fit as ‘‘effective energy’’ or “average beam”. Before the in vivo study,17 an in vitro study14 was done using a phantom and several other materials with well-known attenuation values to find the best effective energy. The two previous studies used the same technique to find the keV. One study31 used HVL for each X-ray tube to determine the average beam energy instead of the best R2 value. The HVL reduces the intensity of an X-ray beam entering that material by one half. The accuracy of the water value is especially important for obtaining HUs values. When looking precisely at tables, we note that the accuracy of water values was inconsistent and widely variable especially in these two studies.14,17 Only one study31 showed more consistent water values because the conversion method was able to produce a water value of 0 HU with a standard deviation of one for three CBCT scanners, and the linear attenuation coefficients from the determined average effective energy were specific to each CBCT X-ray tube.

This systematic review excluded 30 articles that compared GVs with HUs. The reason was that only three studies (two in vitro studies14,31 and one in vivo study)17 showed correlation, prediction equation models and conversion formulas. Most articles were excluded because they only reported correlation/prediction equation models without conversion formulas. Some studies20,22 found that correlation and regression are not enough to convert GVs to HUs. Also, it is important to understand that correlation coefficients (R) and coefficients of determination (R2) are different. R is the degree of relationship between two variables and R2 measures how well the predicted values match the observed values. It depends on the distance between the points and the 1:1 line. The closer the data to the 1:1 line, the higher the coefficient of determination. The literature shows high values of R and R2 above 0.95, which could make us think CBCT GVs have the potential to be used as HUs. However, simulated scatter plots indicate that although high R2 values exist, a deviation of 20% and a numerical value deviation of 500 GVs appeared. This demonstrates the large variability between actual and expected GVs even for high R-values. Some studies14,17 demonstrated linear relationships between GVs and attenuation coefficients at some ‘‘effective’’ energy. Attenuation coefficients were obtained from the linear regression equation and CT numbers in HU were derived using the standard equation. One study31 used HVL to determine the average beam energy. At the extrapolated average energy, linear attenuation coefficients were derived for converting mean pixel values in GV to linear attenuation coefficient values. The resulting linear attenuation coefficient values were converted to CT numbers (HU) using the standard formula. General results have demonstrated that the GVs taken from CBCTs can be used to derive HUs in a clinical environment. However, there is no consistent scientific evidence to support the routine use of CBCTs in BMD evaluations and more studies are needed to demonstrate the diagnostic capacity.

This systematic review indicates in general terms a low RoB because significant methodological differences were found such as the use of different CBCT and MDCT scanners, in vitro versus in vivo studies, and conversion methods. On the other hand, before developing a prediction equation model, previous biostatistical steps are required such as: adequate selection of the sample size, data normality tests, reliability tests or data reproduction, internal validity, external validity47 and finally correlation tests/regression for the predictive equation model. However, these steps were not mentioned in the selected articles.

Limitations

The main limitation of this review was that none of the selected studies reported sensitivity and specificity values to determine the diagnostic capacity. The included studies only show models of correlation/prediction equations to improve diagnostic performance, and we believe that this is not sufficient to determine the diagnostic efficacy. Additionally, this regression analysis has some limitations when used to assess agreement and repeatability. Perhaps, the most important limitation is that showing association does not show repeatability or agreement. The repeatability in a clinical setting is of utmost importance since similar repetitive measurements of the same subjects result in high agreement values. This allows us to conclude that even though the selected studies carried out in in vitro show high R-values, the absence of internal and external validity tests makes their extrapolation to a clinical setting impossible. In addition, in vitro studies were done using phantoms, which did not have clinical parameters such as soft tissue. All included studies used the mass attenuation coefficients from Form X on the NIST website, and the website describes an error of interpolation that conditions the mass attenuation values calculating the attenuation coefficients that are subject to a degree of uncertainty because of this factor.14 Therefore, phantom radiodensity values, applied to patients, have limited value in assessing whether these CBCT values accurately represent the MDCT radiodensity values of patients.

On the other hand, the lack of CBCT standardization and calibration made it difficult to compare the relative values of the HUs obtained from different CBCT scanners making it impossible to extrapolate the data. The results obtained from these conversion methods are unique to each CBCT machine. In addition, the reliability of obtaining GVs from the same subjects on the same day in in vivo studies has not been demonstrated due to the obvious ethical implications involving radiation safety concerns.48

It requires training and more knowledge of radiological and statistical concepts to understand the process of calibrations and conversions of the CBCT machine, which are limiting factors when considering the clinician’ s routine. Clinicians may not understand the full implications of taking GVs from the software and using them to convert to HUs. Although as mentioned above, it is likely that with its correct application, this method can be used to assess how well the CBCT and radiodensity values can represent the radiodensity values of MDCT in patients. Thus, if studies are conducted in patients with validation, training, test data sets, and if 95% prediction intervals are provided, the use of regression analysis might be appropriate.

Future directions

Much work remains to be done, and future research should be directed towards conducting clinical studies that allow better use of the gray scale and provide more robust conclusions. CBCT and MDCT radiodensity measurements of tissues in patients should be used to assess how accurately GVs represent HUs. Remember that before making a predictive model for the conversion from GVs to HUs, the tomographic equipment must be calibrated, in addition to carrying out previous statistical steps of internal and external validity so that the predictive model is clinically applicable. On the other hand, it should help to avoid overfitting or misfitting the data, and for this, cross-validation methods are commonly used. The major obstacle in conducting studies in humans is the excess radiation that would occur if the subject were scanned with a CBCT and a MDCT at the same appointment, so the acquisition of the sample can be complicated. Perhaps, the evolution of CBCT scanners and prediction methods may be a viable alternative in the future.

Conclusion

This systematic review has demonstrated that the GVs from CBCTs cannot be converted to HUs due to the lack of clinical studies of diagnostic capacity to support its use. However, it is evidenced that three conversion steps (equipment calibration, correlation, prediction equation models and standard formula) are needed to obtain pseudo Hounsfield values instead of only getting them from prediction equation models or directly from the software.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: EML, contributed to conception design, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, drafted and critically analysed the manuscript. HAO also contributed to conception design, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, drafted and critically analysed the manuscript. VJA and LDC helped with the research and corrected the writing. DK corrected the writing and made methodological quality assessment of the studies drafted and critically analysed the manuscript. PPC contributed to analysis, interpretation and critically analysed the manuscript. LM, contributed to analysis, interpretation and critically analysed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article. There was no funding for this research project.

Contributor Information

Anderson Holguin, Email: anderson.holguin.r@upch.pe.

Karla Diaz, Email: karlat.diaz@upsjb.pe.

Jose Vidalon, Email: jose.vidalon@upch.pe.

Carlos Linan, Email: carlos.linan.d@upch.pe.

Camila Pacheco-Pereira, Email: cppereir@ualberta.ca.

Manuel Oscar Lagravere Vich, Email: manuel@ualberta.ca.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shapurian T, Damoulis PD, Reiser GM, Griffin TJ, Rand WM. Quantitative evaluation of bone density using the Hounsfield index. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2006; 21: 290–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aranyarachkul P, Caruso J, Gantes B, Schulz E, Riggs M, Dus I, et al. Bone density assessments of dental implant sites: 2. Quantitative cone-beam computerized tomography. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2005; 20: 416–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nucera R, Lo Giudice A, Bellocchio AM, Spinuzza P, Caprioglio A, Perillo L, et al. Bone and cortical bone thickness of mandibular buccal shelf for mini-screw insertion in adults. Angle Orthod 2017; 87: 745–51. doi: 10.2319/011117-34.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turkyilmaz I, Tözüm TF, Tumer C. Bone density assessments of oral implant sites using computerized tomography. J Oral Rehabil 2007; 34: 267–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2006.01689.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.dos Anjos Pontual ML, Freire JSL, Barbosa JMN, Frazão MAG, dos Anjos Pontual A. Evaluation of bone changes in the temporomandibular joint using cone beam CT. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2012; 41: 24–9. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/17815139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shahlaie M, Gantes B, Schulz E, Riggs M, Crigger M. Bone density assessments of dental implant sites: 1. Quantitative computed tomography. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2003; 18: 224–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shapurian T, Damoulis PD, Reiser GM, Griffin TJ, Rand WM. Quantitative evaluation of bone density using the Hounsfield index. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2006; 21: 290–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arisan V, Karabuda ZC, Avsever H, Özdemir T. Conventional multi-slice computed tomography (CT) and cone-beam CT (CBCT) for computer-assisted implant placement. Part I: relationship of radiographic gray density and implant stability. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2013; 15: 893–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2011.00436.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silva IMdeCC, Freitas DQde, Ambrosano GMB, Bóscolo FN, Almeida SM. Bone density: comparative evaluation of Hounsfield units in multislice and cone-beam computed tomography. Braz Oral Res 2012; 26: 550–6. doi: 10.1590/S1806-83242012000600011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee S, Gantes B, Riggs M, Crigger M. Bone density assessments of dental implant sites: 3. bone quality evaluation during osteotomy and implant placement. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2007; 22: 208–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katsumata A, Hirukawa A, Okumura S, Naitoh M, Fujishita M, Ariji E, et al. Relationship between density variability and imaging volume size in cone-beam computerized tomographic scanning of the maxillofacial region: an in vitro study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009; 107: 420–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.05.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naitoh M, Aimiya H, Hirukawa A, Ariji E. Morphometric analysis of mandibular trabecular bone using cone beam computed tomography: an in vitro study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2010; 25: 1093–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.González-García R, Monje F. The reliability of cone-beam computed tomography to assess bone density at dental implant recipient sites: a histomorphometric analysis by micro-CT. Clin Oral Implants Res 2013; 24: 871–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2011.02390.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mah P, Reeves TE, McDavid WD. Deriving Hounsfield units using grey levels in cone beam computed tomography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2010; 39: 323–35. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/19603304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lagravère MO, Fang Y, Carey J, Toogood RW, Packota GV, Major PW. Density conversion factor determined using a cone-beam computed tomography unit NewTom QR-DVT 9000. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2006; 35: 407–9. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/55276404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsa A, Ibrahim N, Hassan B, Motroni A, van der Stelt P, Wismeijer D. Reliability of voxel gray values in cone beam computed tomography for preoperative implant planning assessment. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2012; 27: 1438–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reeves TE, Mah P, McDavid WD. Deriving Hounsfield units using grey levels in cone beam CT: a clinical application. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2012; 41: 500–8. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/31640433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cassetta M, Stefanelli LV, Di Carlo S, Pompa G, Barbato E. The accuracy of CBCT in measuring jaws bone density. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2012; 16: 1425–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chindasombatjaroen J, Kakimoto N, Shimamoto H, Murakami S, Furukawa S. Correlation between pixel values in a cone-beam computed tomographic scanner and the computed tomographic values in a multidetector row computed tomographic scanner. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2011; 35: 662–5. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31822d9725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pauwels R, Jacobs R, Singer SR, Mupparapu M. CBCT-based bone quality assessment: are Hounsfield units applicable? Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2015; 44: 20140238. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20140238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nackaerts O, Maes F, Yan H, Couto Souza P, Pauwels R, Jacobs R. Analysis of intensity variability in multislice and cone beam computed tomography. Clin Oral Implants Res 2011; 22: 873–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2010.02076.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pauwels R, Nackaerts O, Bellaiche N, Stamatakis H, Tsiklakis K, Walker A, et al. Variability of dental cone beam CT grey values for density estimations. Br J Radiol 2013; 86: 20120135. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20120135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P, .PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 2010; 8: 336–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munn Z, Stern C, Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Jordan Z. What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018; 18: 5. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0468-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Office of Health Assessment and Translation (OHAT) Handbook for conducting a literature-based health assessment using OHAT approach for systematic review and evidence integration: National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. 2019. Available from: https://ntp.niehs.nih. gov/ntp/ohat/pubs/handbookmarch2019_508.pdf [accessed 10 June 2020].

- 26.Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 2011; 155: 529–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schünemann H, Brozek J, Oxman A. editors.GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendation. Version 3.2 [updated March 2009].. ; 2009. Available from: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html [Accessed 6 September 2020].

- 28.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. Grade guidelines: 3. rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011; 64: 401–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schünemann HJ, Mustafa RA, Brozek J, Steingart KR, Leeflang M, Murad MH, et al. Grade guidelines: 21 Part 1. study design, risk of bias, and indirectness in rating the certainty across a body of evidence for test accuracy. J Clin Epidemiol 2020; 122: 129–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schünemann HJ, Mustafa RA, Brozek J, Steingart KR, Leeflang M, Murad MH, et al. Grade guidelines: 21 Part 2. test accuracy: inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias, and other domains for rating the certainty of evidence and presenting it in evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 2020; 122: 142–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magill D, Beckmann N, Felice MA, Yoo T, Luo M, Mupparapu M. Investigation of dental cone-beam CT pixel data and a modified method for conversion to Hounsfield unit (HU. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2018; 47: 20170321. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20170321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gulsahi A, Paksoy CS, Yazicioglu N, Arpak N, Kucuk NO, Terzioglu H. Assessment of bone density differences between conventional and bone-condensing techniques using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry and radiography. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007; 104: 692–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burghardt AJ, Link TM, Majumdar S. High-Resolution computed tomography for clinical imaging of bone microarchitecture. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011; 469: 2179–93. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1766-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turkyilmaz I, Ozan O, Yilmaz B, Ersoy AE. Determination of bone quality of 372 implant recipient sites using Hounsfield unit from computerized tomography: a clinical study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2008; 10: 080411085817500–???. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2008.00085.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guerra ENS, Almeida FT, Bezerra FV, Figueiredo PTDS, Silva MAG, De Luca Canto G, et al. Capability of CBCT to identify patients with low bone mineral density: a systematic review. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2017; 46: 20160475. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20160475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lagravère MO, Carey J, Ben-Zvi M, Packota GV, Major PW. Effect of object location on the density measurement and Hounsfield conversion in a NewTom 3g cone beam computed tomography unit. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2008; 37: 305–8. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/65993482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nemtoi A, Czink C, Haba D, Gahleitner A. Cone beam CT: a current overview of devices. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2013; 42: 20120443. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20120443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spin-Neto R, Gotfredsen E, Wenzel A. Impact of voxel size variation on CBCT-based diagnostic outcome in dentistry: a systematic review. J Digit Imaging 2013; 26: 813–20. doi: 10.1007/s10278-012-9562-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodrigues AF, Campos MJ, Chaoubah A, Fraga MR, Farinazzo Vitral RW. Use of gray values in CBCT and MSCT images for determination of density. Implant Dent 2015; 24: 155–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee RJ, Moon W, Hong C. Effects of monocortical and bicortical mini-implant anchorage on bone-borne palatal expansion using finite element analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2017; 151: 887–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.10.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ata-Ali J, Diago-Vilalta J-V, Melo M, Bagán L, Soldini M-C, Di-Nardo C, et al. What is the frequency of anatomical variations and pathological findings in maxillary sinuses among patients subjected to maxillofacial cone beam computed tomography? A systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2017; 22: e400–9. doi: 10.4317/medoral.21456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaêta-Araujo H, Vanderhaeghen O, Vasconcelos KdeF, Coucke W, Coropciuc R, Politis C, et al. Osteomyelitis, osteoradionecrosis, or medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws? can CBCT enhance radiographic diagnosis? Oral Dis 2021; 27: 312–9. doi: 10.1111/odi.13534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsui WK, Yang Y, McGrath C, Leung YY. Improvement in quality of life after skeletal advancement surgery in patients with moderate-to-severe obstructive sleep apnoea: a longitudinal study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2020; 49: 333–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2019.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vale F, Albergaria M, Carrilho E, Francisco I, Guimarães A, Caramelo F, et al. Efficacy of rapid maxillary expansion in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Evid Based Dent Pract 2017; 17: 159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2017.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Q, Tang H, Liu X, Luo Q, Jiang Z, Martin D, et al. Comparison of dimensions and volume of upper airway before and after mini-implant assisted rapid maxillary expansion. Angle Orthod 2020; 90: 432–41. doi: 10.2319/080919-522.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buck LM, Dalci O, Darendeliler MA, Papadopoulou AK. Effect of surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion on upper airway volume: a systematic review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016; 74: 1025–43. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2015.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986; 1: 307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Isfeld D, Lagravere M, Leon-Salazar V, Flores-Mir C. Novel methodologies and technologies to assess mid-palatal suture maturation: a systematic review. Head Face Med 2017; 13: 13.13.. doi: 10.1186/s13005-017-0144-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.