Abstract

Background.

Given changes in marijuana regulations, retail, and products and potential impact on marijuana use, we examined young adult perceptions of different modes of use, the proportion using via different modes (e.g., smoking, vaping, ingesting), and associations with use levels and stability of use over time.

Methods.

We analyzed baseline and one-year follow-up survey data (Fall 2018–2019) among 3,006 young adults (ages 18–34) across 6 metropolitan areas (Atlanta, Boston, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Oklahoma City, San Diego, Seattle). Measures included marijuana use, use frequency, mode of use, sociodemographics, other substance use, and social influences.

Results.

Overall, perceptions were as follows: least harmful/addictive: topicals, oral pills; most socially acceptable: joint/bowl, edibles/beverages; most harmful/addictive and least acceptable: wrapped or vaped with tobacco. Baseline past-month marijuana use prevalence was 39.2% (n=1,178). Most frequent use mode was smoking (joints/bowls/cigar papers; 54.0%), vaping (21.8%), via pipe/bong (15.1%), and ingesting (9.1%). Multinomial logistic regression indicated that, versus smoking, using via other modes correlated with living in states with legalized marijuana retail, and using via pipe/bong correlated with more frequent use (ps<.001). At follow-up, use mode most consistent was pipe/bong (53.3%), followed by smoking (49.3%), vaping (44.5%), and ingesting (32.9%). Past-month abstinence at follow-up was most common among those originally ingesting (34.3% abstinent), followed by smoking (23.6%), vaping (18.8%), and via pipe/bong (14.8%).

Conclusions.

Ongoing surveillance is needed to better understand marijuana use patterns over time across different segments of users (particularly by mode) and to inform interventions aimed at promoting abstinence and curbing chronic use in young adults.

Keywords: marijuana, mode of use, addictiveness, peer acceptability, abstinence, perceived risk

Introduction

The past decade has marked pivotal changes regarding marijuana, the most commonly used federally illegal drug in the US (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020). In 2019, past-month use prevalence was 11.5% in adults, a 66.7% increase since 2010 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020). Young adults (ages 18–25) represent the age group with the highest use, with 23.0% reporting past-month use in 2019 – reflecting a 4.5% increase in prevalence since 2010 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020). In 2019, past-year use prevalence and initiation rates also increased since 2010 by 15.0% and 26.5%, respectively (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020). While marijuana may help with some medical conditions, such as chronic pain, nausea, Parkinson’s disease, and seizure disorders (Bridgeman & Abazia, 2017; Leafly, 2020), marijuana use is related to negative effects, including on mental or physical health, as well as cognitive, academic or occupational performance, particularly in youth and young adults (Cohen et al., 2019; National Academies of Sciences, 2017; Patte et al., 2017) and is implicated in e-cigarette/vaping-associated lung injuries (EVALI) (Centers for Disease Control, 2019).

Marijuana can be used via multiple modes of administration: smoking or inhaling it in joints, bowls, pipes, waterpipes, and blunts; vaping it; consuming edible and drinkable products; and using topicals (e.g., ointments, lotions, lip balms), among others (Schauer et al., 2016). Different products, such as herbs, edibles, or oils may yield distinct “highs” depending on CBD and THC levels and strain (i.e., indica, sativa, hybrid; Loflin & Earleywine, 2014).

The current study draws from social cognitive theory (SCT; Bandura, 2004), which suggests that behavior, such as substance use, is determined by the interplay of one’s cognitions (including attitudes and beliefs), behaviors, and social environment. Among the key determinants of substance use are outcome expectancies, which include perceived risk – regarding both harm to health and addictiveness – as well as perceived social norms (Bandura, 2004). There has been limited research examining how different marijuana products and modes of use are perceived in relation to these critical factors. Regarding marijuana use more generally, young adults who are current marijuana users perceive greater peer acceptability of marijuana relative to nonusers (Koval et al., 2019). Some recent research indicates that young adults perceive edibles as less harmful than smoking marijuana (Reboussin et al., 2019), while other research indicates the opposite because of the potential for increased potency of edibles (Popova et al., 2017). Limited research has examined young adults’ perceptions of different modes of use across a range of dimensions, such as peer acceptability, harm, addictiveness, and likelihood of future use. However, research regarding the rapidly evolving tobacco market indicates that different tobacco products and inherent modes of use are associated with differing perceptions of harm, such that vaping nicotine or smoking tobacco via waterpipes/hookah is perceived as less harmful and addictive but more socially acceptable (Berg et al., 2015). Thus, perceptions of these modes of marijuana use and others, including ingesting or using topicals, likely differ from one another and from smoking marijuana via joints or bowls. Moreover, marijuana and tobacco co-use – particularly via vaping, waterpipe, and blunts – is common (Schauer et al., 2015; Schauer et al., 2016; Schauer et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2016) and may also be perceived differently.

A socioecological perspective (McLeroy et al., 1988) provides a lens for contextualizing marijuana use with respect to marijuana-related policies and legalization. Regarding macro-level factors, 2 main influences are marijuana policy context and – relatedly – the marijuana retail environment. Since 2012, 15 states and DC, including 4 states in 2020 alone, legalized marijuana for adults ≥21, and 36 states legalized medical marijuana (Berke & Gal, 2020). The existing literature indicates a mix of implications of both medical marijuana legislation (Carliner et al., 2017; Cerda et al., 2017; Hasin et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2017; Sarvet et al., 2018; Schinke, Schwinn et al., 2017) and marijuana retail legalization, particularly for young adults (Cerda et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2018; Kerr et al., 2018; Parnes et al., 2018; Rusby et al., 2018). For instance, whereas substantial research suggests that states with medical marijuana legalization have not seen an increase in marijuana use among adolescents or young adults (Johnson et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2018; Sarvet et al., 2018; Schinke et al., 2017), other findings suggest that medical marijuana laws lead to increases in such use among adolescents and adults (Carliner et al., 2017; Cerdá et al., 2017). Moreover, there is some evidence that states with legalized marijuana retail (relative to other states) have greater marijuana use rates among young adults (Jones et al., 2018; Kerr et al., 2018; Parnes et al., 2018; Rusby et al., 2018).

As policies have changed, the marijuana retail environment has expanded alongside robust marketing efforts (Berg et al., 2017; Cannabis Business Plan, 2018; Hudock, 2019; Pollochia, 2018). Perhaps as a result, a growing percent of marijuana sales are from newer products, such as edibles or topicals (Comnes, 2016; Marijuana Business Daily, 2016). Moreover, the next decade is expected to mark expansion of medical and retail marijuana legalization (Berke & Gal, 2020; Daniller, 2019), product diversity, and marketing in the US (Cannabis Business Plan, 2018; Hudock, 2019; Pollochia, 2018).

Within this context, recent shifts provide a critical period for examining who initiates and continues their use, particularly among young adults (Borodovsky et al., 2016; Borodovsky et al., 2017). Examining modes of use and their relevance for predicting continued use versus abstinence is critical for understanding young adults at greatest risk for continuing use. Studies examining marijuana use from adolescence to young adulthood – and spanning young adulthood – have generally found evidence for individuals who mature out of use, begin using later, or use chronically over time (Brook et al., 2011; Caldeira et al., 2012; Epstein et al., 2015; Kelly & Vuolo, 2018). Notably, less use over time predicts better educational, career, and family transitions/outcomes (Kelly & Vuolo, 2018), and many of the risk factors for use, including being male, being sexual or racial/ethnic minority, greater depressive symptoms, and social influences are also correlates of continued marijuana use over time (Bears Augustyn et al., 2019; Chen & Jacobson, 2012; Derefinko et al., 2016; Epstein et al., 2015; Evans-Polce et al., 2015; Kelly & Vuolo, 2018; Nelson et al., 2015; Tucker et al., 2019). However, no prior research has explicitly examined the role of modes of use in relation to use levels or continued use over time.

While the literature to date is rich, there is limited research regarding how different marijuana products are perceived or whether they may lead to more chronic use or addiction. Thus, this study examined: 1) perceptions of different modes of use of marijuana products; 2) profiles of use with regard to most frequent mode of use; and 3) the extent to which most frequent mode of use a) remains stable and b) predicts abstinence over a one-year period among young adults. This study used data from a sample of young adults (ages 18–34) drawn from 6 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs: Atlanta, Boston, Minneapolis, Oklahoma City, San Diego, Seattle), 2 of which had legalized marijuana retail policies in place during baseline in 2018 (San Diego, Seattle) and one of which implemented such a policy between baseline and one-year follow-up (Boston; Berg et al., 2020).

Methods

Study Design

The current study is an analysis of survey data among 3,006 young adults (aged 18–34) participating in a 2-year, 5-wave longitudinal cohort study, the Vape shop Advertising, Place characteristics and Effects Surveillance (VAPES) study. VAPES examines the vape retail environment and its impact on substance use, drawing participants from the 6 aforementioned MSAs, selected for their variation in state tobacco control and marijuana retail legislation. This study, detailed elsewhere (Berg et al., 2020), involved survey data collection launched in Fall 2018 with assessments every 6 months for 2 years during Fall and Spring. This study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board.

Participants & Recruitment

Potential participants were recruited via social media. Eligibility criteria were: 1) 18–34 years old; 2) living in one of the 6 MSAs; and 3) English speaking. Purposive sampling was used to ensure sufficient proportions of the sample represented past-month e-cigarette and cigarette users (roughly 1/3 each), both sexes, and racial/ethnic minorities.

Advertisements posted on Facebook and Reddit targeted individuals: 1) using keywords reflecting those within the eligible age range and MSAs (e.g., young adult, city name); 2) by identifying work groups or activities of interest that appeal to young adults (e.g., followers or group members of pages related to sports/athletics, entertainment, or tobacco-related interests); and 3) by including images of diverse young adults in various settings. Individuals who clicked on ads were directed to a webpage with a study description and consent form, screened for eligibility, and then administered the baseline survey. Subgroup enrollment was capped by MSA. Participants received an email 7 days after completing the baseline survey asking them to confirm their participation by clicking a “confirm” button included in an email. After confirming, participants were enrolled and emailed their first incentive ($10 e-gift card).

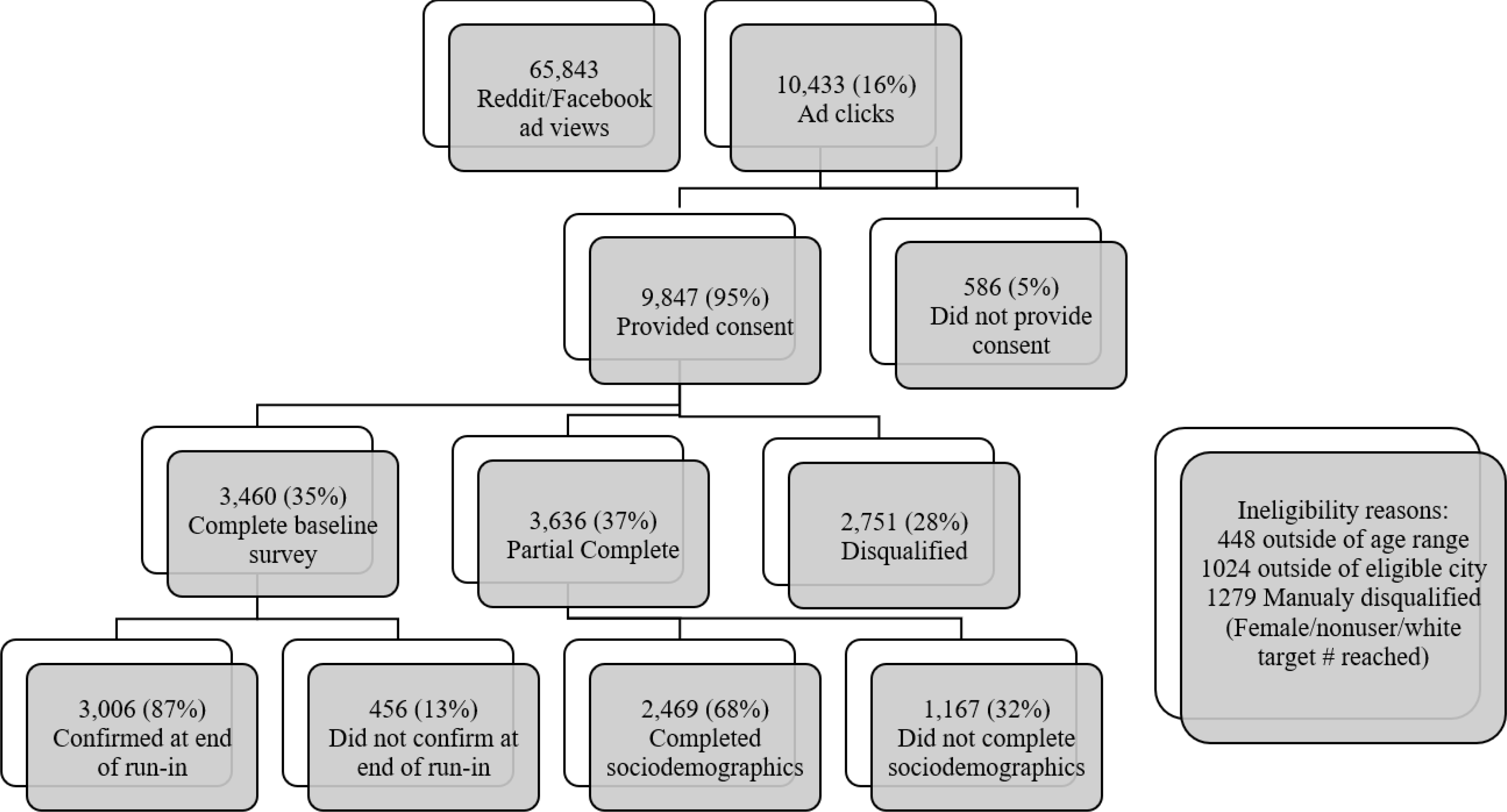

The duration of recruitment ranged from 87 to 104 days across MSAs. Overall, 65,843 Facebook/Reddit users viewed study ads, 10,433 clicked on ads, 9,847 consented, and 7,096 were eligible. Additionally, 2,751 were not allowed to advance to the baseline survey, with 1,427 ineligible and 1,279 not enrolled in order to reach recruitment targets of other demographics (Figure 1). The baseline survey was completed by 3,460 (48.8%; 51.2% partial completes, n=3,636); 3,006 (87%) confirmed participation. Those who did not fully complete the baseline survey differed from those who did complete the survey in that they were younger and more likely male, Black or other race, and past-month e-cigarette and cigarette users; those who did not (vs. did) confirm participation were more likely Black or other race and past-month e-cigarette and cigarette users (Berg et al., 2020).

Figure 1.

Participant recruitment flowchart

The current analyses focused on baseline survey data (n=3,006) and one-year follow-up survey data (79.0% response rate, n=2,375). Participants received a $20 e-gift card following the completion of the follow-up survey. Attrition analyses indicated that participants who completed the follow-up survey were more likely female, a current student, older, were more likely to have at least a bachelor’s degree, were more likely to reside in Atlanta and Boston, were less likely to reside in Oklahoma City and Seattle, were less likely to live in a state with legalized marijuana retail policies during baseline, and reported lower levels of past-month cigarette, e-cigarette, and marijuana use at baseline relative to individuals who did not complete the follow-up survey.

Measures

Outcomes: Perceptions & Likelihood of Future Use

In Fall 2019, one-year follow-up from baseline, we asked all participants, including marijuana users and non-users, to evaluate different modes of marijuana use (i.e., topical creams, ointments or balms; oral pills; bud in a joint or bowl; edibles or beverages; vaped e-liquids; vaped with tobacco/nicotine; in a waterpipe or bong; in a waterpipe or bong with tobacco; rolled in cigar papers without tobacco; rolled in cigar papers with tobacco) by asking them to rate on a 7-point scale (1=not at all to 7=extremely): 1) “How harmful to your health do you think the use of these marijuana products are?” 2) “How addictive do you think these marijuana products are?” 3) “How socially acceptable among your peers do you think the use of each of these marijuana products are?” and 4) “How likely are you to try or continue to use these marijuana products in the next year?” (Berg et al., 2015).

Outcomes: Marijuana Use & Modes of Use

At baseline and follow-up, participants were asked to report the number of days used in the past 30 days and number of times used per day with the option to refuse to answer (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018). Lifetime use was also assessed at baseline. Lifetime and past-month use were operationalized as dichotomous variables (yes/no). We also asked participants how they have ever used marijuana at baseline and how they use marijuana most of the time at baseline and follow-up, with response options of: smoked in a joint; smoked in a bowl; ingested with or without food (for example, edibles); drank it; vaped it with a vaporizer; vaped with tobacco mixed with it; smoked in a waterpipe or bong; smoked in a waterpipe with tobacco; rolled in cigar papers without tobacco; rolled in cigar papers with tobacco; or other (please specify; Fong et al., 2006). Participants were allowed to select only one mode that they used most frequently. Responses to these questions were recategorized as: smoked (including “smoked in a joint”, “smoked in a bowl”, “rolled in cigar papers with tobacco”, and “rolled in cigar papers without tobacco”); pipe/bong (including “smoked in a waterpipe or bong” and “smoked in a waterpipe with tobacco”); ingested (including “ingested with or without food” and “drank it”); vaped (including “vaped with a vaporizer” and “vaped with tobacco mixed with it”); and other (including tinctures, dabs, etc.). We account for tobacco use behaviors (see below) in our models to account for modes that included tobacco.

Correlates

Sociodemographics assessed included MSA of residence and whether it was in a state with or without legalized marijuana retail, age, sex, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, highest level of educational attainment, and employment status.

Tobacco use was assessed by asking participants to report number of days in the past 30 days they used: cigarettes, e-cigarettes, little cigars/cigarillos, large cigars, hookah/waterpipe, and smokeless tobacco (National Institutes of Health, 2020). Regarding social influences, participants were asked if a parental figure uses/used marijuana (yes/no) and any tobacco product (yes/no; Berg et al., 2015). Participants were also asked how many of their 5 closest friends use marijuana and the respective tobacco products (1–5; Berg et al., 2015). Friends’ tobacco use was operationalized as an index score (i.e., average number using each tobacco product). Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire – 2 item (PHQ-2; Kroenke et al., 2003), which assesses feeling down/depressed and little interest in doing things in the past 2 weeks (0=not at all to 3=nearly every day; summed scores of 0–6; Cronbach’s alpha=.87).

Data Analysis

Participant characteristics, perceptions of modes of use, and marijuana use characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. Chi-square and one-way ANOVA tests were used to explore differences in participant characteristics across MSAs in relation to perceptions of modes of use and to most frequent mode of marijuana use (i.e., smoked, pipe/bong, ingested, vaped) at baseline. Next, we conducted a multinomial logistic regression to examine potential correlates (i.e., marijuana retail legalization, sociodemographics, tobacco use, social influences, depressive symptoms) of most frequent mode of use (referent: smoked) at baseline. In addition, chi-square tests were conducted to examine associations between most frequent mode of marijuana use at baseline and one-year follow-up, including past-month abstinence at follow-up. Binary logistic regression was conducted to examine baseline mode of use and the aforementioned potential correlates in relation to past-month marijuana abstinence at one-year follow-up. Regression analyses were also conducted using multilevel modeling to account hierarchical structure of the data (i.e., young adults at the individual level nested in MSA; Aveyard et al., 2004; Aveyard et al., 2004; Bovaird & Shaw, 2012). However, all intra-class correlations were approximately .01, and findings were not significantly different. Analyses were conducted using SPSS v26.0 and alpha set at .05.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Supplementary Table 1 provides characteristics of the sample of 3,006 characterized across the MSAs (average age of 24.56, SD=4.72; 42.3% male; 31.6% sexual minority; 71.6% White; 11.4% Hispanic). At baseline, 71.6% (n=2151) reported lifetime marijuana use, and 39.2% (n=1178) reported past-month use. Bivariate analyses indicated that past-month users (vs. non-users) were more likely to live in states with legalized marijuana retail and to live in Seattle but not Atlanta; they were also younger, more likely to be sexual minorities, White, with less than a bachelor’s degree, employed part-time and not students, tobacco users, and children of users of tobacco but not marijuana, and reported more friends who use marijuana and tobacco and more depressive symptoms (ps<.001; not shown in tables).

Likelihood of Future Use and Perceptions at Follow-up

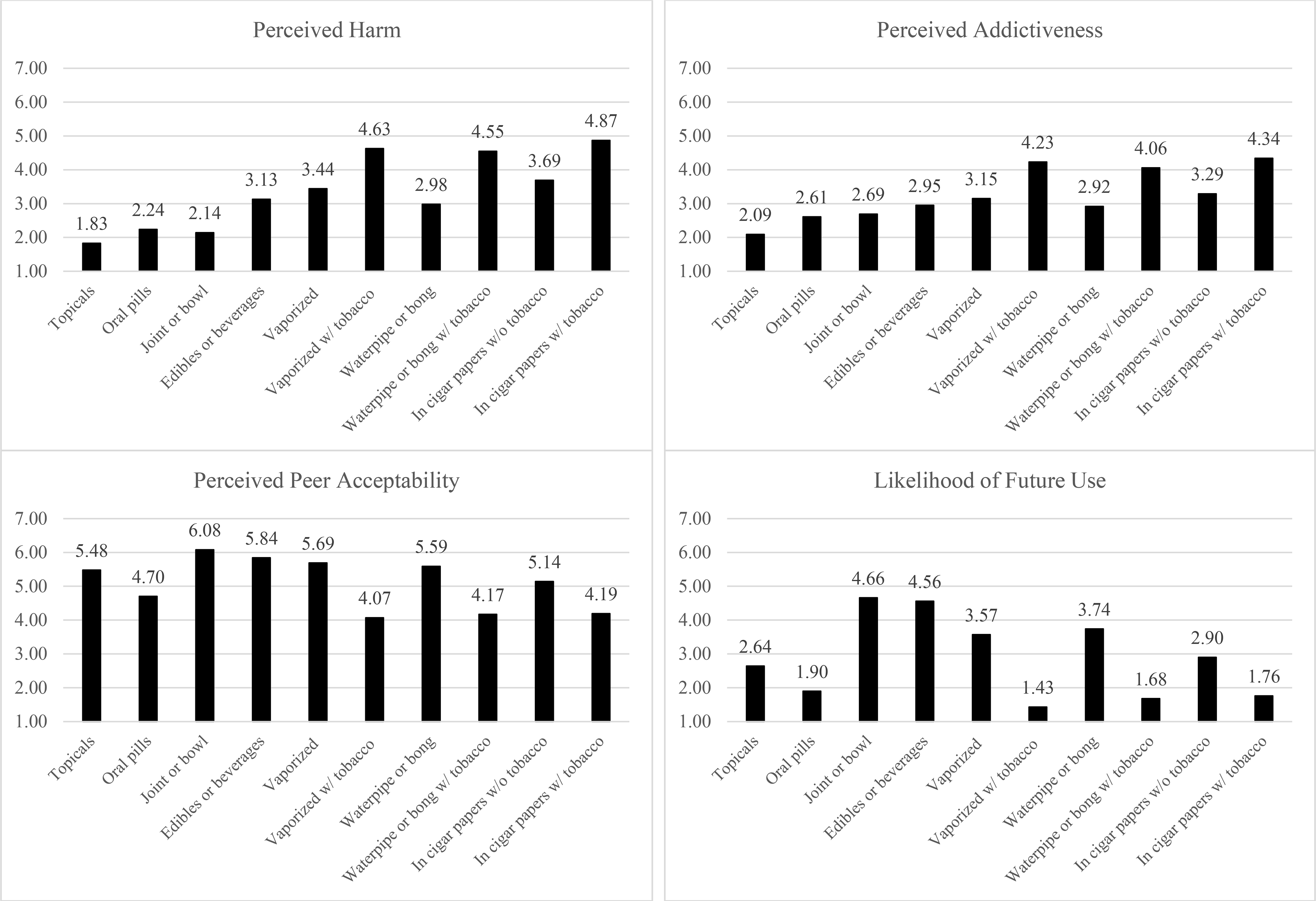

Mean scores indicated that on average, topicals were perceived as the least harmful and least addictive, with oral pills being second and joint/bowl being third for both measures (Figure 2). Participants perceived smoking marijuana in cigar papers with tobacco as the most harmful and addictive, with the other 2 forms reflecting co-use with tobacco (i.e., vaped, pipe/bong) also perceived as among the most harmful and addictive. Assessments of perceived harm and addiction of these 3 forms without tobacco were parallel with cigar papers perceived as most harmful, followed by vaping then pipe/bong.

Figure 2.

Perceived harm to health, addictiveness, and peer acceptability of different modes of use and self-reported likelihood of use at follow-up

With regard to peer acceptability and likelihood of use in the next year, the highest rated was joint/bowl, followed by edibles/beverages. Also highly rated for both peer acceptability and likelihood of future use were vaped or pipe/bong without tobacco. The modes rated lowest for both peer acceptability and likelihood of future use were vaped with tobacco, followed by pipe/bong with tobacco, and cigar papers with tobacco.

As anticipated, past-month users at follow-up when this assessment was conducted, reported less perceived harm and addictiveness, more perceived peer acceptability, and greater likelihood of future use across all modes (ps<.001; not shown in tables/figures). Also as expected, ratings of perceived harm and addictiveness were positively correlated with one another, ratings of perceived peer acceptability and likelihood of future use were positively correlated with one another, and perceived harm/addictiveness and peer acceptability/likelihood of use were negatively associated (ps<.001).

Separating users and nonusers, few differences across MSAs were identified. However, several significant findings (ps<.01) were noted among marijuana users and nonusers across retail legalization context. Among marijuana users, those in legalized versus not legalized retail states reported: 1) no differences in harm or addictiveness across modes; 2) greater peer acceptability across all modes; and 3) greater likelihood of future use of topicals, but no other differences. Among nonusers, those in legalized (vs. non-legalized) states reported: 1) greater harm of bud in a joint/bowl, bud in pipe/bong, oral pills, vaped with tobacco, and rolled with cigar papers with or without tobacco; 2) no differences in addictiveness; 3) greater peer acceptability of use via pipe/bong and topicals; and 4) greater likelihood of future use via topicals and oral pills, but no other differences.

Mode of Use at Baseline

Table 1 shows the descriptive and bivariate results of the 1,149 participants who reported past-month marijuana use via smoking in joints/bowls/cigar papers (n=621, 54.0%), using pipe/bong (n=173, 15.1%), ingesting it (n=105, 9.1%), or vaping it (n=250, 21.8%), excluding those who used marijuana most frequently via other modes (e.g., dabs, n=19).

Table 1.

Correlates of most frequent mode of use among past-month marijuana users at baseline, N=1,149*

| Total N= 1149 (100%) | Smoke N=621 (54.0%) | Pipe/bong N=173 (15.1%) | Ingest N=105 (9.1%) | Vape N=250 (21.8%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | p |

|

| ||||||

| MSA, N (%) | <.001 | |||||

| Atlanta | 172 (15.0) | 102 (16.4) | 28 (16.2) | 13 (12.4) | 29 (11.6) | |

| Boston | 224 (19.5) | 128 (20.6) | 27 (15.6) | 15 (14.3) | 54 (21.6) | |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul | 210 (18.3) | 140 (22.5) | 23 (15.0) | 16 (15.2) | 31 (12.4) | |

| Oklahoma City | 92 (8.0) | 59 (9.5) | 12 (6.9) | 7 (6.7) | 14 (5.6) | |

| San Diego | 188 (16.4) | 61 (9.8) | 32 (18.5) | 27 (25.7) | 68 (27.2) | |

| Seattle | 263 (22.9) | 131 (21.1) | 51 (29.5) | 27 (25.7) | 54 (21.6) | |

| Marijuana retail law, N (%) | <.001 | |||||

| Legalized | 451 (39.3) | 192 (30.9) | 83 (48.0) | 54 (51.4) | 128 (51.2) | |

| Not legalized | 698 (60.7) | 429 (69.1) | 90 (52.0) | 51 (48.6) | 122 (48.8) | |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Age, M (SD) | 24.19 (4.63) | 24.11 (4.63) | 22.80 (4.44) | 25.57 (4.61) | 24.75 (4.54) | <.001 |

| Male, N (%)** | 483 (42.0) | 239 (38.5) | 85 (49.1) | 34 (32.4) | 125 (50.0) | <.001 |

| Sexual minority, N (%) | 465 (40.5) | 272 (43.8) | 72 (41.6) | 31 (29.5) | 90 (36.0) | .017 |

| Race, N (%) | .011 | |||||

| White | 865 (75.3) | 457 (73.6) | 136 (78.6) | 85 (81.0) | 187 (74.8) | |

| Black | 54 (4.7) | 43 (6.9) | 4 (3.5) | 4 (3.8) | 5 (2.0) | |

| Asian | 86 (7.5) | 40 (6.5) | 14 (8.1) | 5 (4.8) | 27 (10.8) | |

| Other | 144 (12.5) | 81 (13.0) | 20 (11.6) | 21 (20.0) | 31 (12.4) | |

| Hispanic, N (%) | 140 (12.2) | 83 (13.4) | 25 (14.5) | 11 (10.5) | 21 (8.4) | .153 |

| Education ≥bachelor’s degree, N (%) | 793 (69.0) | 420 (67.6) | 108 (62.4) | 82 (78.1) | 183 (73.2) | .017 |

| Employment, N (%) | <.001 | |||||

| Student | 281 (24.5) | 144 (23.2) | 57 (32.9) | 20 (19.0) | 60 (24.0) | |

| Unemployed | 92 (80.1) | 47 (7.6) | 22 (12.7) | 10 (9.5) | 13 (5.2) | |

| Full-time | 430 (37.4) | 229 (36.9) | 38 (22.0) | 49 (46.7) | 114 (45.6) | |

| Part-time | 346 (30.1) | 201 (32.4) | 56 (32.4) | 26 (24.8) | 63 (25.2) | |

| Marijuana use characteristics | ||||||

| Number of days used, past 30 days, M (SD) | 13.32 (11.49) | 12.71 (11.25) | 18.91 (11.55) | 6.01 (7.76) | 14.04 (11.41) | <.001 |

| Times used per day, M (SD) | 2.60 (2.62) | 2.52 (2.49) | 3.67 (3.42) | 1.35 (.81) | 2.59 (2.55) | <.001 |

| Past-month tobacco use, N (%) | ||||||

| Cigarettes | 480 (41.8) | 291 (46.9) | 89 (51.4) | 17 (16.2) | 83 (35.6) | <.001 |

| E-cigarettes | 660 (57.4) | 362 (58.3) | 122 (70.1) | 36 (34.3) | 140 (56.0) | <.001 |

| Little cigars/cigarillos | 280 (24.4) | 174 (28.0) | 60 (34.7) | 7 (6.7) | 39 (15.6) | <.001 |

| Large cigars | 128 (11.1) | 75 (12.1) | 17 (9.8) | 5 (4.8) | 31 (12.4) | .135 |

| Hookah | 179 (15.6) | 99 (15.9) | 33 (19.1) | 9 (8.6) | 38 (15.2) | .132 |

| Smokeless tobacco | 52 (4.5) | 24 (3.9) | 12 (6.9) | 5 (4.8) | 11 (4.4) | .395 |

| Any tobacco | 839 (73.0) | 479 (77.1) | 144 (83.2) | 46 (43.8) | 170 (68.0) | <.001 |

| Psychosocial factors | ||||||

| Parental use of… N (%) | ||||||

| Marijuana | 323 (28.1) | 180 (29.0) | 53 (30.6) | 28 (26.7) | 62 (24.8) | .523 |

| Tobacco | 448 (39.0) | 271 (43.6) | 65 (37.6) | 28 (26.7) | 84 (33.6) | .001 |

| Number of friends using… M (SD) | ||||||

| Marijuana | 0.98 (0.12) | 0.99 (0.12) | 0.99 (0.11) | 0.97 (0.18) | 0.98 (0.13) | .711 |

| Tobacco | 0.14 (0.13) | 0.15 (0.14) | 0.16 (0.13) | 0.09 (0.10) | 0.13 (0.12) | <.001 |

| Depressive symptoms, M (SD) | 1.98 (1.75) | 2.00 (1.73) | 2.28 (1.81) | 1.61 (1.55) | 1.87 (1.81) | .012 |

Note: p-values indicate omnibus tests (per ANOVA and Chi-Square) across modes of use.

Excluding those who report “other” most frequent modes of use at baseline, N=19.

87 reported “other” sex.

Bivariate analyses indicated that differences in frequent modes of use at baseline existed across MSAs, with smoked being disproportionately represented in Minneapolis, vaping in San Diego, and pipe/bong in Seattle (p<.001); smoking was more frequent in the MSAs without legalized marijuana retail, whereas the other forms were more frequent in the MSAs in states with legalized marijuana retail (p<.001). Bivariate analyses also indicated differences in most frequent mode of use in relation to age, sex, sexual minority status, race, education level, and employment status (ps<.05; see Table 1 for specifics).

Regarding marijuana use characteristics, most frequent mode of use at baseline was associated with past-month marijuana use and use per day (ps<.001), with those using pipe/bong reporting the greatest number of days used and times used per day and those ingesting reporting the least. Most frequent mode of marijuana use was also associated with using any tobacco product (p<.001), with tobacco users being disproportionately represented among those most frequently using marijuana joints/bowls or pipes/bongs. Differences were also found for different tobacco products used, specifically for cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and little cigars/cigarillos (ps<.05). Most frequent mode of use was also associated with parental and friend tobacco product use (p<.001), but not parental or friend marijuana use. Mode of marijuana use was also associated with depressive symptoms (p=.012), with those using pipe/bong having the highest and those ingesting having the lowest.

Table 2 shows correlates of different modes of use at baseline per multinomial logistic regression. Living in states with legalized marijuana retail (p=.001), being younger (p=.001), being female (p=.049), and more frequent marijuana use (p<.001) increased odds of using marijuana via a pipe/bong relative to smoking. Living in states with legalized marijuana retail (p<.001), using less frequently (p<.001), being a tobacco nonuser (p=.001), and having fewer tobacco-using friends (p=.031) increased odds of ingesting versus smoking marijuana. Additionally, living in states with legalized marijuana retail (p<.001) and being female (p=.004) and White (vs. Black, p=.011) increased odds of vaping versus smoking marijuana.

Table 2.

Multinomial logistic regression examining correlates of most frequent mode of use among past-month marijuana users (referrent: smoked via joint) at baseline, N=1,149*

| Pipe/bong | Ingest | Vape | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | aOR | CI | p | aOR | CI | p | aOR | CI | p |

|

| |||||||||

| Legalized marijuana retail (ref: not legalized) | 1.86 | 1.29–2.70 | .001 | 2.40 | 1.51–3.82 | <.001 | 2.05 | 1.49–2.82 | <.001 |

| Sociodemographics | |||||||||

| Age | 0.93 | 0.89–0.97 | .001 | 1.09 | 1.04–1.15 | .001 | 1.03 | 1.00–1.07 | .098 |

| Male (ref: female)** | 0.69 | 0.48–1.00 | .049 | 1.12 | 0.69–1.80 | .657 | 0.62 | 0.45–0.86 | .004 |

| Sexual minority (ref: heterosexual) | 0.93 | 0.64–1.36 | .710 | 0.61 | 0.37–1.00 | .051 | 0.78 | 0.56–1.09 | .150 |

| Race (ref: White) | |||||||||

| Black | 0.29 | 0.09–0.99 | .051 | 0.38 | 0.11–1.33 | .130 | 0.25 | 0.09–0.73 | .011 |

| Asian | 1.18 | 0.59–2.33 | .645 | 0.59 | 0.21–1.62 | .304 | 1.42 | 0.81–2.47 | .220 |

| Other | 0.75 | 0.36–1.16 | .146 | 0.68 | 0.42–1.77 | .679 | 0.90 | 0.55–1.47 | .669 |

| Hispanic (ref: non-Hispanic) | 0.97 | 0.57–1.67 | .914 | 0.76 | 0.36–1.64 | .487 | 0.58 | 0.34–1.00 | .051 |

| Number of days of marijuana use, past 30 | 1.06 | 1.04–1.07 | <.001 | 0.93 | 0.90–0.95 | <.001 | 1.01 | .99–1.03 | .080 |

| Any tobacco use (ref: no) | 1.30 | 0.78–2.17 | .312 | 0.41 | 0.25–0.68 | .001 | 0.74 | 0.51–1.08 | .121 |

| Psychosocial factors | |||||||||

| Parental use of… | |||||||||

| Marijuana | 0.99 | 0.65–1.51 | .957 | 1.32 | 0.76–2.29 | .323 | 0.86 | 0.59–1.26 | .440 |

| Tobacco | 0.71 | 0.48–1.05 | .089 | 0.66 | 0.39–1.11 | .117 | 0.78 | 0.55–1.10 | .158 |

| Number of friends using… | |||||||||

| Marijuana | 1.01 | 0.86–1.18 | .933 | 0.99 | 0.83–1.18 | .883 | 0.95 | 0.84–1.08 | .443 |

| Tobacco | 0.84 | 0.40–1.74 | .637 | 0.51 | 0.28–0.94 | .031 | 0.66 | 0.40–1.09 | .102 |

| Depressive symptoms, M (SD) | 1.06 | 0.96–1.17 | .281 | 0.96 | 0.83–1.11 | .593 | 0.99 | 0.90–1.08 | .780 |

|

| |||||||||

| Nagelkerke R 2 | .239 | ||||||||

Excluding those who report “other” most frequent modes of use, N=19.

87 reported “other” sex.

ICC for null model=.042

Mode of Use & Abstinence at Follow-up

Table 3 shows the relationship between most frequent mode of use at baseline and at follow-up, including if participants reported no current use at follow-up. Among the 823 past-month marijuana users who completed the one-year follow-up survey, the mode of use that was most consistent was pipe/bong (53.3% consistently reported same mode), followed by smoking (49.3%), vaped (44.5%), and ingested (32.9%). Past-month abstinence at follow-up was most frequently reported among those originally reporting that they ingested marijuana (34.3% were abstinent), followed by those who smoked (23.6%), vaped (18.8%), and used pipe/bong (14.8%). Among those who most frequently used via pipe/bong, ingested, and vaped but switched, the greatest proportion switched to smoking.

Table 3.

Crosstabs of baseline most frequent mode of use at baseline and most frequent mode of use at one-year follow-up, N=823

| Total N=823 |

Follow-up

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoke | Pipe/bong | Ingest | Vape | No use | ||

|

| ||||||

| Baseline | Follow-up | N=292 (35.5%) | N=130 (15.8%) | N=66 (8.0%) | N=153 (18.6%) | N=182 (22.1%) |

|

| ||||||

| Baseline | ||||||

| Smoke | 440 (53.5%)* | 217 (49.3%) | 46 (10.5%) | 24 (5.5%) | 49 (11.1%) | 104 (23.6%) |

| Pipe/bong | 122 (14.8%)* | 22 (18.0%) | 65 (53.3%) | 3 (2.5%) | 14 (11.5%) | 18 (14.8%) |

| Ingest | 70 (8.5%)* | 17 (24.3%) | 1 (1.4%) | 23 (32.9%) | 5 (7.1%) | 24 (34.3%) |

| Vape | 191 (23.2%)* | 36 (18.8%) | 18 (9.4%) | 16 (8.4%) | 85 (44.5%) | 36 (18.8%) |

Chi-squared = 343.739, p < .001.

Column %; otherwise, % indicates row %.

Controlling for other correlates (e.g., sociodemographics, MSA, legalized versus not), most frequently using marijuana via ingesting relative to via pipe/bong at baseline increased odds of abstinence at follow-up (aOR=2.50, CI: 1.19–5.25, p=.015; Nagelkerke R-square=.068). When including number of days used at baseline, this association was no longer significant, but rather, fewer number of days of use at baseline increased odds of abstinence at follow-up (aOR=0.91, CI: 0.89–0.93, p<.001, Nagelkerke R-square=.201).

Discussion

This study was among the first to examine perceptions of different modes of marijuana use – and product types – with regard to perceived health risk, addictiveness, and peer acceptability and the extent to which use across these modes is stable and/or predicts abstinence at one-year follow-up. Noteworthy is that the mode of use reported as most likely in the future in this sample is via joint/bowl followed by edibles/beverages, likely due to the broad availability of bud relative to more novel products across the MSAs. Moreover, various modes of use, particularly topicals and oral pills, were perceived to have little health risks or risks for addiction, and the vast majority of modes are perceived to have little health risks and risks of addictiveness. One study from 2016 to 2018 indicated that the proportion of people perceiving smoking marijuana to bear risk increased over time; however, the proportion perceiving novel products, specifically edibles, to bear risk reduced over time (Reboussin et al., 2019). Data for this study are from Fall 2018 and Fall 2019, with data regarding perceptions being from 2019, as the EVALI epidemic was first emerging (Navon et al., 2019). Subsequently, sales of edibles increased in at least 4 states (Jackson, 2019), which may reflect increased risk perceptions. Thus, ongoing research is warranted regarding perceived risks of different marijuana products and modes of use over time.

In addition, modes of use perceived to have higher risk involved co-use with tobacco, which reflects other literature indicating that marijuana in general is perceived to be less harmful and addictive than tobacco, as well as more socially acceptable (Berg et al., 2015). While anti-tobacco campaigns have a long-standing history at the national, state, and local levels and have been embedded into the lives of young people (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012), there has been limited public health efforts to recognize the risks involved with marijuana use, which may contribute to young adults’ beliefs that marijuana use bears little risk (Payne et al., 2018).

We also found differences in perceptions of modes of use and most frequently used modes across marijuana retail legalization context. Among marijuana users, while no differences in harm or addictiveness across modes were found across legalization context, those in legalized (vs. not legalized) marijuana retail states indicated greater peer acceptability across all modes and greater likelihood of future use of topicals. Moreover, compared to smoking via joint/bowl, other modes of use, including via pipe/bong, ingested, and vaped, were more frequent in states with legalized marijuana retail. Among nonusers, while no differences in terms of perceived addictiveness were found across legalization contexts, those in states with legalized marijuana retail reported greater perceived harm of various modes, including via joint/bowl, pipe/bong, oral pills, vaped, and rolled with cigar papers, but greater peer acceptability of use via pipe/bong and topicals and greater likelihood of future use via topicals and oral pills. Collectively, these findings indicate that particular novel marijuana products and modes of use may be perceived as more socially normative and appealing among those in states with legalized marijuana retail, coinciding with existing literature (Pacula & Smart, 2017). These findings are likely due to exposure to such products and their marketing where they are commercially available.

Among past-month marijuana users, over half (54%) reported most frequently using via joint/bowl, with fewer reporting using via vaping (21.8%), pipe/bong (15.1%), or ingesting (9.1%). Across a one-year period, those using via pipe/bong were most consistent in their mode of use and in using marijuana in general (i.e., not reporting abstinence at one-year follow-up), likely also related to their greater levels of use. Those most frequently ingesting marijuana were the least consistent in their mode of use and were the most likely to report abstinence at one-year follow-up, which similarly may likely be related to their lower levels of use. Also notable, among those who switched their most frequent mode of use over time, the mode adopted was most likely via joint/bowl. In sum, while smoking via joint/bowl was most frequent, data suggest that use via pipe/bong is a particular indicator of ongoing use.

Regarding other sociodemographics, findings indicated that, compared to most frequently using via joint/bowl, being younger correlated with most frequently using via pipe/bong, which is concerning as this mode of use represents the highest risk subgroup in terms of use levels and future use. However, being older – as well as not using tobacco – was associated with most frequently ingesting marijuana, which represents a relatively low-risk subgroup in terms of level of use and future use. These findings may reflect the fact that people do naturally mature out of substance use behaviors (Brook et al., 2011; Caldeira et al., 2012; Epstein et al., 2015; Kelly & Vuolo, 2018); however, these findings also likely reflect that this young subgroup of marijuana users warrant particular intervention to reduce use and prevent/treat addiction. In addition, being White correlated with most frequently vaping marijuana versus smoking via joint/bowl, and being female was associated with most frequently using marijuana via pipe/bong and ingesting it. These findings are difficult to interpret but warrant future research.

These results have implications for research and practice. In research, ongoing surveillance is needed to document perceptions of marijuana products, modes of use, and their implications for chronic use, addiction, and mental and physical health in order to inform policy and intervention efforts. For example, current findings suggest that those who mainly ingest marijuana versus those who smoke it are likely to show different, less adverse outcomes over time. However, newer products are more available and only more recently used in some contexts, particularly states with legalized marijuana retail, so this hypothesis is premature and warrants ongoing research to inform policy that may dictate limits on dosages of retail marijuana or to inform public health campaigns that specify particular risks for using marijuana across different products/modes, as was relevant as EVALI cases emerged. Moreover, clinicians working with young people must assess marijuana use in order to address this increasing public health problem, and asking about modes of use of marijuana may provide insights into frequency of use and likelihood of future use, particularly in cases where individuals are likely to underreport their use levels and symptoms of addiction.

Limitations

This study is limited in generalizability to other young adults in the included MSAs or across the US. Rates of tobacco and marijuana use should not be interpreted as use prevalence rates, nor should other participant characteristics, given the purposive sampling design used in this study. For example, 23.0% of US young adults reported past-month marijuana use in 2019 (NIDA, 2020), a lower proportion than in this sample (39.2%). In addition, self-reported data has the potential for bias especially when participants may feel inclined to answer in a way they find socially acceptable (e.g., underreporting marijuana use), as well as recall bias. Finally, whereas the current study assessed frequency of marijuana use and continuation of use over time as indicators of high-risk marijuana use, our measures did not account for the problems associated with marijuana use or potentially hazardous use. Future research should examine modes of use in relation to problems associated with marijuana use and potentially hazardous use to provide additional insight into which modes of use represent highest risk.

Conclusion

Current findings indicate that most frequent mode of marijuana use is an indicator of overall level of risk – with those using marijuana via pipe/bong reporting the highest levels of use and greatest odds of continued use. Moreover, many novel marijuana products were perceived as bearing low health risks and risks for addiction. Finally, modes of use involving tobacco co-use were perceived as higher risk, suggesting the success of anti-tobacco campaigns in increasing perceived risks of tobacco use. However, the limited efforts to educate young people regarding marijuana use and its potential risks (e.g., addiction) represent a major concern, particularly as social norms related to marijuana use continue to evolve.

Supplementary Material

Funding Details

This work was supported by the US National Cancer Institute (R01CA215155-01A1; PI: Berg). Dr. Berg is also supported by other US National Cancer Institute funding (R01CA179422-01; PI: Berg; R01CA239178-01A1; MPIs: Berg, Levine), the US National Institutes of Health/Fogarty International Center (1R01TW010664-01; MPIs: Berg, Kegler), and the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences/Fogarty International Center (D43ES030927-01; MPIs: Berg, Marsit, Sturua).

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Data Availability Statement

Data not publicly available (available upon request).

References

- Aveyard P, Markham WA, & Cheng KK (2004). A methodological and substantive review of the evidence that schools cause pupils to smoke. Social Science & Medicine, 58(11), 2253–2265. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aveyard P, Markham WA, Lancashire E, Bullock A, Macarthur C, Cheng KK, & Daniels H (2004). The influence of school culture on smoking among pupils. Social Science & Medicine, 58(9), 1767–1780. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00396-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior, 31(2), 143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bears Augustyn M, Loughran T, Larroulet P, Fulco CJ, & Henry KL (2019). Intergenerational marijuana use: A life course examination of the relationship between parental trajectories of marijuana use and the onset of marijuana use by offspring. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 34, 818–829. doi: 10.1037/adb0000530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ, Duan X, Getachew B, Pulvers K, Crawford N, Sussman S, . . . Henriksen L (2020). Young adult e-cigarette use and retail exposure in 6 US metropolitan areas. Tobacco Regulatory Science, 7(1), 59–75. doi: 10.18001/TRS.7.1.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ, Henriksen LA, Cavazos-Rehg P, Schauer GL, & Freisthler B (2017). The development and testing of the marijuana retail surveillance tool (mrst): assessing marketing and point-of-sale practices among recreational marijuana retailers. Health Education Research, 32(6), 465–472. doi: 10.1093/her/cyx071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ, Stratton E, Schauer GL, Lewis M, Wang Y, Windle M, & Kegler M (2015). Perceived harm, addictiveness, and social acceptability of tobacco products and marijuana among young adults: marijuana, hookah, and electronic cigarettes win. Substance Use and Misuse, 50(1), 79–89. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.958857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke J, & Gal S (2020). All the states where marijuana is legal — and 5 more that just voted to legalize it. Business Insider. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/legal-marijuana-states-2018-1# [Google Scholar]

- Borodovsky JT, Crosier BS, Lee DC, Sargent JD, & Budney AJ (2016). Smoking, vaping, eating: Is legalization impacting the way people use cannabis? International Journal of Drug Policy, 30, 141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodovsky JT, Lee DC, Crosier BS, Gabrielli JL, Sargent JD, & Budney AJ (2017). U.S. cannabis legalization and use of vaping and edible products among youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 177, 299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.02.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovaird JA, & Shaw LH (2012). Multilevel structural equation modeling. In Handbook of developmental research methods (pp. 501–518). [Google Scholar]

- Bridgeman MB, & Abazia DT (2017). Medicinal cannabis: history, pharmacology, and implications for the acute care setting. P T, 42(3), 180–188. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28250701 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Lee JY, Brown EN, Finch SJ, & Brook DW (2011). Developmental trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood: personality and social role outcomes. Psychological Reports, 108(2), 339–357. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21675549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira KM, O’Grady KE, Vincent KB, & Arria AM (2012). Marijuana use trajectories during the post-college transition: Health outcomes in young adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 125(3), 267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannabis Business Plan. (2018). North America cannabis legal market size projections, 2018. Retrieved from https://cannabusinessplans.com/cannabis-legal-market-size-projections/

- Carliner H, Brown QL, Sarvet AL, & Hasin DS (2017). Cannabis use, attitudes, and legal status in the US: A review. Preventive Medicine, 104, 13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Outbreak of lung injury associated with the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). The guide to community preventive services. Retreived from http://www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html.

- Cerda M, Wall M, Feng T, Keyes KM, Sarvet A, Schulenberg J, . . . Hasin DS (2017). Association of state recreational marijuana laws with adolescent marijuana use. JAMA Pediatrics, 171(2), 142–149. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdá M, Wall M, Feng T, Keyes KM, Sarvet A, Schulenberg J, . . . Hasin DS (2017). Association of state recreational marijuana laws with adolescent marijuana use. JAMA Pediatrics, 171(2), 142–149. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, & Jacobson KC (2012). Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: gender and racial/ethnic differences. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(2), 154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen K, Weizman A, & Weinstein A (2019). Positive and negative effects of cannabis and cannabinoids on health. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comnes J (2016). Edibles and concentrates already make up a quarter of oregon’s cannabis sales. Willemette Week. Retrieved from http://www.wweek.com/news/2016/09/29/edibles-and-concentrates-already-make-up-a-quarter-of-oregons-cannabis-sales/ [Google Scholar]

- Daniller A (2019). Two-thirds of Americans support marijuana legalization. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/11/14/americans-support-marijuana-legalization/

- Derefinko KJ, Charnigo RJ, Peters JR, Adams ZW, Milich R, & Lynam DR (2016). Substance use trajectories from early adolescence through the transition to college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 77(6), 924–935. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27797694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M, Hill KG, Nevell AM, Guttmannova K, Bailey JA, Abbott RD, . . . Hawkins JD (2015). Trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence into adulthood: Environmental and individual correlates. Developmental Psychology, 51(11), 1650–1663. doi: 10.1037/dev0000054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Polce RJ, Vasilenko SA, & Lanza ST (2015). Changes in gender and racial/ethnic disparities in rates of cigarette use, regular heavy episodic drinking, and marijuana use: Ages 14 to 32. Addictive Behaviors, 41, 218–222. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong GT, Cummings KM, Borland R, Hastings G, Hyland A, Giovino GA, . . . Thompson ME (2006). The conceptual framework of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Project. Tobacco Control, 15 Suppl 3, iii3–11. doi:15/suppl_3/iii3 [pii] 10.1136/tc.2005.015438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Wall M, Keyes KM, Cerda M, Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, . . . Feng T (2015). Medical marijuana laws and adolescent marijuana use in the USA from 1991 to 2014: results from annual, repeated cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Psychiatry, 2(7), 601–608. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00217-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudock C (2019). U.S. legal cannabis market growth. New Frontier Data. Retrieved from https://newfrontierdata.com/cannabis-insights/u-s-legal-cannabis-market-growth/ [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M (2019). Sales of marijuana edibles up in at least four states in wake of vape health scare. Marijuana Business Daily. Retrieved from https://mjbizdaily.com/sales-of-marijuana-edibles-up-in-at-least-four-states-in-wake-of-vape-health-scare/ [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Hodgkin D, & Harris SK (2017). The design of medical marijuana laws and adolescent use and heavy use of marijuana: Analysis of 45 states from 1991 to 2011. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 170, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JK, Johnson RM, Hodgkin D, Jones AA, Matteucci AM, & Harris SK (2018). Heterogeneity of state medical marijuana laws and adolescent recent use of alcohol and marijuana: Analysis of 45 states, 1991–2011. Substance Abuse, 39(2), 247–254. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2017.1389801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J, Nicole Jones K, & Peil J (2018). The impact of the legalization of recreational marijuana on college students. Addictive Behaviors, 77, 255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BC, & Vuolo M (2018). Trajectories of marijuana use and the transition to adulthood. Social Science Research, 73, 175–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DCR, Bae H, & Koval AL (2018). Oregon recreational marijuana legalization: Changes in undergraduates’ marijuana use rates from 2008 to 2016. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 32(6), 670–678. doi: 10.1037/adb0000385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koval AL, Kerr DCR, & Bae H (2019). Perceived prevalence of peer marijuana use: changes among college students before and after Oregon recreational marijuana legalization. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 45(4), 392–399. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2019.1599381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (2003). The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 41(11), 1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leafly. (2020). Qualifying conditions for medical marijuana by state. Retrieved from https://www.leafly.com/news/health/qualifying-conditions-for-medical-marijuana-by-state

- Loflin M, & Earleywine M (2014). A new method of cannabis ingestion: the dangers of dabs? Addictive Behaviors, 39(10), 1430–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marijuana Business Daily. (2016, June). Chart of the week: Sales of marijuana concentrates, edibles surging in Colorado. Retrieved from http://mjbizdaily.com/chart-of-the-week-sales-of-marijuana-concentrates-edibles-surging-in-colorado/ [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, & Glanz K (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 351–377. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3068205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: The current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Retrieved from https://www.nap.edu/catalog/24625/the-health-effects-of-cannabis-and-cannabinoids-the-current-state [PubMed]

- National Institutes of Health. (2020). The Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health. Retrieved from https://pathstudyinfo.nih.gov/UI/FAQsResMobile.aspx

- Navon L, Jones CM, Ghinai I, King BA, Briss PA, Hacker KA, & Layden JE (2019). Risk factors for e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI) among adults who use e-cigarette, or vaping, products - Illinois, July-October 2019. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(45), 1034–1039. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6845e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SE, Van Ryzin MJ, & Dishion TJ (2015). Alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use trajectories from age 12 to 24 years: Demographic correlates and young adult substance use problems. Developmental Psychopathology, 27(1), 253–277. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIDA. (2020). Vaping & cannabis trends among young adults (19–22). Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/trends-statistics/infographics/vaping-cannabis-trends-among-young-adults-19-22

- Pacula RL, & Smart R (2017). Medical marijuana and marijuana legalization. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13, 397–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnes JE, Smith JK, & Conner BT (2018). Reefer madness or much ado about nothing? Cannabis legalization outcomes among young adults in the United States. International Journal of Drug Policy, 56, 116–120. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patte KA, Qian W, & Leatherdale ST (2017). Marijuana and alcohol use as predictors of academic achievement: A longitudinal analysis among youth in the COMPASS Study. Journal of School Health, 87(5), 310–318. doi: 10.1111/josh.12498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne JB, Getachew B, Shah J, & Berg CJ (2018). Marijuana use among young adults: Who quits and why? Health Behavior and Policy Review, 5(3), 77–90. doi: 10.14485/HBPR.5.3.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollochia T (2018). Legal Cannabis Industry Poised For Big Growth, In North America And Around The World. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/thomaspellechia/2018/03/01/double-digit-billions-puts-north-america-in-the-worldwide-cannabis-market-lead/#21f233136510 [Google Scholar]

- Popova L, McDonald EA, Sidhu S, Barry R, Richers Maruyama TA, Sheon NM, & Ling PM (2017). Perceived harms and benefits of tobacco, marijuana, and electronic vaporizers among young adults in Colorado: Implications for health education and research. Addiction, 112(10), 1821–1829. doi: 10.1111/add.13854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reboussin BA, Wagoner KG, Sutfin EL, Suerken C, Ross JC, Egan KL, . . . Johnson RM (2019). Trends in marijuana edible consumption and perceptions of harm in a cohort of young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 205, 107660. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusby JC, Westling E, Crowley R, & Light JM (2018). Legalization of recreational marijuana and community sales policy in Oregon: Impact on adolescent willingness and intent to use, parent use, and adolescent use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 32(1), 84–92. doi: 10.1037/adb0000327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarvet AL, Wall MM, Fink DS, Greene E, Le A, Boustead AE, . . . Hasin DS (2018). Medical marijuana laws and adolescent marijuana use in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 113(6), 1003–1016. doi: 10.1111/add.14136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer GL, Berg CJ, Kegler MC, Donovan DM, & Windle M (2015). Differences in tobacco product use among past month adult marijuana users and nonusers: Findings from the 2003–2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer GL, Hall CD, Berg CJ, Donovan DM, Windle M, & Kegler MC (2016). Differences in the relationship of marijuana and tobacco by frequency of use: A qualitative study with adults aged 18–34 years. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(3), 406–414. doi: 10.1037/adb0000172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer GL, King BA, Bunnell RE, Promoff G, & McAfee TA (2016). Toking, vaping, and eating for health or fun: marijuana use patterns in adults, U.S., 2014. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 50(1), 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer GL, Njai R, & Grant-Lenzy AM (2020). Modes of marijuana use - smoking, vaping, eating, and dabbing: Results from the 2016 BRFSS in 12 States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 209, 107900. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinke S, Schwinn T, Hopkins J, Gorroochurn P, & Wahlstrom L (2017). Is the legalization of marijuana associated with its use by adolescents? Substance Use and Misuse, 52(2), 256–258. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1223139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health. from Office of Applied Studies, Division of Population Surveys http://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP20-07-01-001, NSDUH Series H-55). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/release/2019-national-survey-drug-use-and-health-nsduh-releases [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Rodriguez A, Dunbar MS, Pedersen ER, Davis JP, Shih RA, & D’Amico EJ (2019). Cannabis and tobacco use and co-use: Trajectories and correlates from early adolescence to emerging adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 204, 107499. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Zhu H, & Swartz MS (2016). Trends in cannabis use disorders among racial/ethnic population groups in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 165, 181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data not publicly available (available upon request).