Abstract

The duplicated CCAAT box is required for γ gene expression. We report here that the transcriptional factor NF-Y is recruited to the duplicated CCAAT box in vivo. A mutation of the duplicated CCAAT box that severely disrupts the NF-Y binding also reduces the accessibility level of the γ gene promoter, affects the assembly of basal transcriptional machinery, and increases the recruitment of GATA-1 to the locus control region (LCR) and the proximal promoter and the recruitment of transcription cofactor CBP/p300 to the LCR. These findings suggest that recruitment of NF-Y to the duplicated CCAAT box plays a role in the chromatin opening of the γ gene promoter as well as in the communication between the γ gene promoter and the LCR.

The human β-globin locus consists of five genes, ɛ, Gγ, Aγ, δ, and β, which exhibit erythroid- and development-specific expression. The ɛ-globin gene is expressed in the early embryonic stage and then silenced around week 8 of gestation; the Gγ- and Aγ-globin genes are transcribed in the fetus; and the β-globin gene is expressed in the adult. The high-level transcription of the individual genes at the appropriate developmental stage is dependent on the β-globin locus control region (LCR) (reviewed in reference 11). The β-globin LCR is located 5 to 25 kb 5′ to the ɛ gene and contains five major DNase I-hypersensitive sites designated 5′HS1 to 5′HS5 (8, 35). Several regulatory cis elements have been identified in these HSs (reviewed in reference 31). Recently it has been proposed that the entire β-globin locus is separated into three independent but interactive subdomains: the LCR domain, the ɛγ domain, and the δβ domain (13). It is speculated that the chromatin opening of each domain requires domain-specific chromatin-remodeling complexes, which are recruited by sequence-specific activators (1). The molecular mechanism of the chromatin remodeling of the β locus remains unclear, and the general model of communications between these subdomains remains to be established.

Several transcription factor-binding motifs exist within the proximal γ gene promoter. A duplicated CCAAT box is a unique feature of the γ-globin genes, although a single CCAAT box is present in the promoters of all other β-locus genes. CCAAT box motifs are present in a very large number of promoters. A number of proteins may bind to the CCAAT motif, such as CTF/NF1 (CCAAT transcription factor/nuclear factor 1), C/EBP (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein), NF-Y/CBF (CCAAT-binding factor, also called CP1), CDP (CCAAT displacement protein), NF-E3/COUP-TFII, and GATA-1 (reviewed in reference 20). The last five of these bind to the duplicated CCAAT box region of the γ promoter in vitro. NF-Y/CBF requires a high degree of conservation of the CCAAT sequence and is considered to be the major protein recognizing the CCAAT box (reviewed in reference 20). NF-Y is a complex composed of three subunits: NF-YA (CBF-B), NF-YB (CBF-A), and NF-YC (CBF-C) (20). It has been suggested that NF-Y can facilitate the recruitment of coactivators to modulate transcriptional activity in Xenopus (18).

In this study, we used chromatin immunoprecipitation assays to determine whether NF-Y binds to the γ CCAAT box in vivo and to investigate how the duplicated CCAAT box participates in gene regulation. Our results show that NF-Y is one of the factors that specifically binds to the duplicated CCAAT boxes in vivo. Furthermore, our results suggest that NF-Y recruitment to the duplicated CCAAT box region may facilitate the recruitment of the basal transcription machinery. NF-Y binding to the CAAT box also appears to participate in the communication between the γ gene promoter and the LCR complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Constructs and RNA and DNA analysis.

Construct μLCR(−382)Aγ, which contains a μLCR-linked human Aγ gene from −382 (StuI) to +1950 (HindIII), has been described previously (32). Plasmid μLCR(−382)Aγ(mCCAAT) was constructed by replacing the duplicated CCAAT box sequence ACCAAT with the sequence AGATCT (a BglII site) through PCR-based mutagenesis. Total RNA isolation, genomic DNA preparation, RNase protection assay, and copy number measurement were described previously (32).

Cell culture and stable transfection.

The human myeloid cell line HL-60 was maintained and cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Cellgro) containing 10% fetal calf serum. The human erythroleukemia cell line K562 and the murine erythroleukemia cell line MEL were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Cellgro) containing 10% FCS and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Life Technologies). The cells were grown in a humidified incubator at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. For stable transfection assays, 10 μg of plasmid μLCR(−382)Aγ or μLCR(−382)Aγ(mCCAAT) was cotransfected into 107 log-phase K562 or MEL cells with 1 μg of Geneticin-resistant gene (neo gene)-containing plasmid by using the Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad). The cells were cultured in Geneticin-free medium for 24 h and transferred to 96-well dishes. They were then selected with 900 μg of G418 per ml for 7 to 10 days. Each cell pool contained more than 50 individual G418-resistant clones. For induction of globin gene expression, MEL cells were treated with 10 μmol of hemin per liter and 3 mmol of N,N′-hexamethylene bisacetamide (HMBA) and K562 cells were treated with 50 μmol of hemin per liter for 3 days. Nuclei were isolated for the restriction enzyme accessibility assay. Genomic DNA and total RNA were isolated for the Southern blot assay and the RNase protection assay, respectively.

Western blot assays.

Whole-cell extracts were prepared from K562 cells. Western blot assays were performed using the ECL Western blot analysis system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Anti-NF-YA antibody and the secondary antibody, donkey anti-goat immunoglobulin G (IgG) (horseradish peroxidase conjugate), were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The Benchmark prestained protein ladder was from GIBCO-BRL Life Technologies.

Restriction enzyme accessibility.

Nuclei were isolated as described by Stamatoyannopoulos et al. (33). For each construct, at least three independent stably transfected cell pools were analyzed. Cultured cells (3 × 107) were washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline and centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min. The pellets were resuspended to a final cell density of 2 × 107 to 4 × 107 per ml in ice-cold RSB (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2). Cell membranes were disrupted by adding 10% NP-40 solution dropwise to a final concentration of 0.25%. The resulting nuclei were pelleted at 400 × g for 10 min and resuspended in RSB. An aliquot (50 units of optical density at 260 nm) of nuclear suspension was subjected to EcoNI digestion in 50 μl of digestion buffer at 37°C. The reaction was ended by adding proteinase K solution, and the mixture was incubated at 55°C for 3 h. DNA was prepared by a standard procedure and completely digested with restriction enzymes (EcoRI for MEL cells; EcoRV, ClaI, and BspHI for K562 cells). Southern blotting was performed with a BamHI-EcoRI Aγ probe. The results were quantified with a PhosphorImager.

ChIP assay.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as described previously (7, 26) with minor modifications. A 150-ml volume of hemin-induced K562 or MEL cells (3 × 108) was fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Soluble chromatin complex in 25 ml of 1 × radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer was produced by sonication, which generated DNA fragments averaging 300 to 500 bp. All polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. A 1-ml volume of soluble chromatin and various amounts of antibody (5 μl of anti-RNA polymerase II or anti-NF-E2/p45 antibody, 10 μl of anti-NF-YA antibody, or 15 μl each of anti-TBP, anti-CBP/p300, or anti-GATA-1 antibody) were used in each immunoprecipitation. The DNA concentration was determined with a TK100 fluorometer (Hoefer Scientific Instruments). About 2 ng of immunoprecipitated DNA was used as template in each reaction in a total volume of 20 μl. About 1/10,000 to 1/20,000 of the genomic DNA isolated from 1 ml of soluble chromatin (about 2 to 5 ng) was used as the input template per reaction. Quantitative PCR was performed with the appropriate primer pairs (product size between 150 and 280 bp, 25 to 27 cycles for single-pair PCR, 28 to 29 cycles for duplex PCR). A PhosphorImager and Image Quant software were used for quantification. At least three independent experiments were performed for each antibody.

Primers.

The following primer pairs were designed and used in this work.

(i) Human primers.

The human primers used were as follows: human Aγ promoter region, 5′γT (TGGCTAAACTCCACCCATGGGTTG) and 3′γT (CCAGAAGCGAGTGTGTGGAACTGCT); human ɛ promoter region, 5′ɛT (TGGAGAACAGGGGGCCAGAACTTCG) and 3′ɛT (ATGATGCCAGGCCTGAGAGCTTGC); human β promoter region, 5′βT (TTGGCCAATCTACTCCCAGGAGCAGG) and 3′βT (GAGGTTGCTAGTGAACACAGTTGTG); and human HS2 core region, 5′hHS2 (CCCATAGTCCAAGCATGAGCAGTTC), 3′hHS2 (CTCTAGGCTGAGAACATCTGGGCAC), 5′hHS3 (CCAGCCTATAACCCATCTGGGCCCTG) and 3′hHS3 (GAACCTCTGATAGACACATCTGGCAC).

(ii) Mouse primers.

The mouse primers used were as follows: mouse ɛy gene promoter region, 5′EyT (TGCTGACCCTCCCATGACCTGGCTCC) and 3′EyT (GAGGTTGCTGGTGATCACAGGAGTGT); mouse βmajor gene promoter region, 5′βmaj (AGCCTGATTCCGTAGAGCCACAC) and 3′βmaj (ACAACTATGTCAGAAGCAAATGTG); mouse HS2 core region, 5′mHS2 (TTCAGCCTTGTGAGCCAGCATCAGGC) and 3′mHS2 (CTAGGTTATGTCACACAGCAAGGCAG); and mouse HS3 core region, 5′mHS3 (CAGCAAACCCTAGGCCTCCTAGGGAC) and 3′mHS3 (CTCAGAGTCACAGACTCCACCCTGAG).

RESULTS

The duplicated CCAAT box is necessary for γ gene expression.

To examine the role of the duplicated CCAAT box on γ gene expression, we replaced the sequence CCAAT of both the distal and the proximal CCAAT boxes with the sequence GATCT, which is expected to disrupt CCAAT box function. Gel shift experiments using K562 and MEL cell nuclear extracts and DNA probes containing the proximal γ promoter region (−15 to −196) showed that the CCAAT-to-GATCT mutation abolished the binding of CCAAT box-related proteins (data not shown). This mutation was subsequently introduced into the construct μLCR(−382)Aγ (32). This construct was used because it is associated with high γ gene expression in established erythroid cell lines and in adult transgenic mice (30, 32). By introducing the γCCAAT box mutation into the μLCR(−382)Aγ construct, we expected to readily detect and quantitate any negative effects of the mutation on Aγ gene expression.

Two erythroid cell lines were used; K562 cells, expressing the γ and ɛ gene but not the β genes, and MEL cells, expressing only adult murine globins. These cell lines were stably transfected with either the control plasmid μLCR(−382)Aγ or the mutant μLCR(−382)Aγ(mCCAAT). As shown in Table 1, the expression of the mutant CCAAT Aγ gene in the K562 cells ranged from 26 to 41% of that of the control Aγ genes, with a mean value of 33.8% ± 6.8% (P < 0.002). The mean Aγ expression in the 22 MEL cell pools containing the γCCAAT mutant was about 13% of that of the control (P < 0.0003) (Table 2). These results indicated that the duplicated CCAAT box is necessary for the expression of Aγ gene in both established cell lines.

TABLE 1.

The CCAAT-to-GATCT mutation of the duplicated CCAAT box reduces the expression of Aγ gene in stably transfected K562 cells

| Construct | Expt no. | Cell pool | Copy no. | Transfected Aγ mRNA level as % of endogenous γ mRNA/copy | % of control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μLCR(−382)Aγ(mCCAAT) | 1 | 1 | 5.5 | 5.7 | 33.7 |

| 2 | 6.7 | 5.8 | 34.3 | ||

| 2 | 3 | 4.2 | 6.3 | 37.8 | |

| 4 | 5.7 | 4.4 | 26.3 | ||

| 3 | 5 | 2.2 | 6.9 | 40.8 | |

| 6 | 3.2 | 5.3 | 31.7 | ||

| 7 | 2.9 | 5.4 | 32.3 | ||

| Mean | 5.7 ± 0.8 | 33.8 ± 6.8 | |||

| μLCR(−382)Aγ (control) | Mean of 8 pools | 16.8 ± 6.4 |

TABLE 2.

The CCAAT-to-GATCT mutation of the duplicated CCAAT box severely reduces the expression of the Aγ gene in stably transfected MEL cells

| Construct | Expt no. | Cell pool | Copy no. | Aγ mRNA level as % of murine α mRNA/copy | % of control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μLCR(−382)Aγ(mCCAAT) | 1 | 1 | 7.7 | 2.1 | 16.0 |

| 2 | 2 | 11.4 | 1.4 | 10.8 | |

| 3 | 13.9 | 0.9 | 7.0 | ||

| 3 | 4a | 4.1 | 2.9 | 22.5 | |

| 5 | 11.2 | 1.0 | 7.5 | ||

| 4 | 6 | 15.9 | 0.6 | 4.9 | |

| 7 | 9.7 | 0.9 | 7.0 | ||

| 5 | 8 | 7.3 | 1.1 | 8.7 | |

| 9 | 7.1 | 1.7 | 12.8 | ||

| 6 | 10a | 19.0 | 0.4 | 2.8 | |

| 11 | 12.1 | 0.6 | 4.5 | ||

| 7 | 12 | 4.9 | 3.3 | 25.6 | |

| 13 | 4.8 | 2.2 | 17.3 | ||

| 14 | 6.4 | 1.6 | 12.4 | ||

| 8 | 15 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 21.0 | |

| 16 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 14.1 | ||

| 9 | 17 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 24.5 | |

| 18 | 3.3 | 2.2 | 16.8 | ||

| 10 | 19 | 3.9 | 2.4 | 18.1 | |

| 20 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 23.0 | ||

| 11 | 21 | 3.5 | 0.9 | 7.0 | |

| 22 | 4.3 | 1.0 | 8.0 | ||

| Mean | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 13.3 ± 11 | |||

| μLCR(−382)Aγ (control) | Mean of 21 pools | 13 ± 4.2 |

These cell pools were used to perform the ChIP assays.

The duplicated CCAAT box is required for chromatin remodeling of the γ gene promoter.

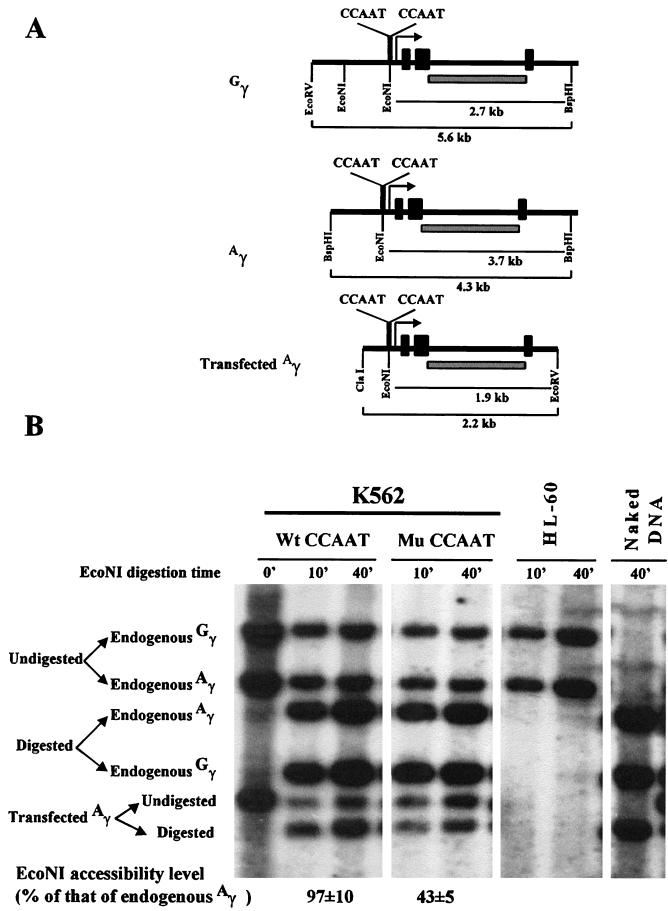

To examine whether the CCAAT box mutation affected the chromatin structure of the γ gene promoter, we performed restriction enzyme accessibility assays. We took advantage of the existence of a unique restriction enzyme site, EcoNI site, located between the proximal and distal CCAAT boxes (Fig. 1A). EcoNI digestion of nuclei from stably transfected K562 cells was used to assess the accessibility of the chromatin of the γ promoter region. Genomic DNA was isolated from the EcoNI-treated or untreated nuclei and completely digested with BspHI, ClaI, and EcoRV. Southern blot hybridization was performed with the probes shown in Fig. 1A. As shown in Fig. 1B, digestion of nuclei of K562 cells stably transfected with the wild-type plasmid μLCR(−382)Aγ produced three new bands, resulting from the digestion of endogenous Gγ and Aγ genes and the transfected Aγ gene. The digested proportion of each gene was calculated by comparing the amount of digested DNA to that of total (digested plus undigested) DNA. The relative EcoNI accessibility of the transfected Aγ gene was calculated by computing the ratio of the digested proportion of the transfected Aγ gene to that of the endogenous Aγ gene.

FIG. 1.

The CCAAT-to-GATCT mutation of the duplicated CCAAT box significantly reduces the EcoNI accessibility to the γ gene promoter in stably transfected K562 cells. (A) Schematic representation of the structure of the endogenous Gγ and Aγ genes and the stably transfected μLCRAγ constructs. The locations of EcoNI, EcoRV, ClaI, and BspHI sites and the fragments derived from each gene are shown. The location, in each gene, of the probe used for Southern blot hybridization is shown by a hatched bar. A bent arrow indicates the transcription initiation site. Solid rectangles indicate the exons. (B) A representative experiment of the EcoNI accessibility assay. Nuclei isolated from K562 cells stably transfected with μLCR(−382)Aγ (indicated as Wt CCAAT) or μLCR(−382)Aγ(mutCCAAT) (indicated as Mu CCAAT) were subjected to EcoNI accessibility assays. As described in Materials and Methods, genomic DNA was isolated from the EcoNI-treated or untreated nuclei and completely digested with BspHI, ClaI, and EcoRV. Southern blot hybridization was performed with the probe shown in panel A.

The EcoNI accessibility of the promoter of the μLCR(−382)Aγ gene was identical to that of the endogenous Aγ gene (97% ± 10%) (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the EcoNI accessibility of the promoter of the μLCR(−382)Aγ(mCCAAT) gene was 43% ± 5% of that of the endogenous Aγ gene. The positive control, showing complete digestion of the endogenous and transfected γ genes, was EcoNI-digested naked genomic DNA from the stably transfected K562 cells (Fig. 1B). As a negative control, we used nuclei from a human myeloid cell line, HL-60; as shown in Fig. 1B, the silenced γ genes of this cell line were totally inaccessible to EcoNI. These findings showed that the mutation of the duplicated CCAAT box altered the chromatin structure of the γ promoter. Similar results were obtained with stably transfected MEL cells (data not shown).

NF-Y binds in vivo to the γ gene promoter through the duplicated CCAAT box.

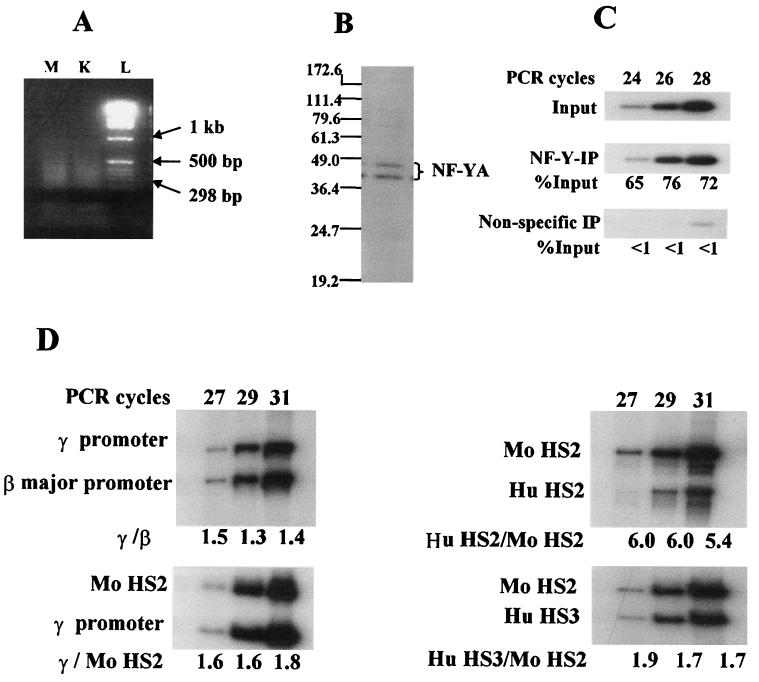

Gel shift assays have previously shown that NF-Y binds to all globin gene promoters through the CCAAT box (19). To determine whether NF-Y binds to the γ gene promoter in vivo, we performed ChIP assays using anti-NF-YA antibodies. Western blot assays showed that the antibodies specifically detected the two isoforms (2) of NF-YA (Fig. 2B). Figure 2 shows the optimization of the ChIP assay system. As described in Materials and Methods, the chromatin was sheared by sonication to generate DNA fragments less than 500 bp long (Fig. 2A). When 2 ng of anti-NF-YA antibody-immunoprecipitated DNA and 4 ng of input DNA were used as templates, the PCR-amplified γ promoter signals increased linearly with the increase of PCR cycles from 24 to 28 and the signals from the specific immunoprecipitated DNA templates were proportional to those from the input DNA templates (Fig. 2C). Similarly, in the duplex PCRs, when 4 ng of input DNA was used as templates, the signals amplified with the various combined primer pairs increased linearly with the increase of PCR cycles from 27 to 31 as shown by the constancy of the ratio of the signal to the internal control (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 2.

Optimization of the ChIP assay. (A) Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel of input DNA isolated from the sonicated chromatin. M, chromatin of MEL cells; K, chromatin of K562 cells; L, DNA ladder. (B) Western blotting using the anti-NF-YA antibody. Note that the antibody detects the two 41- to 45-kDa isoforms of NF-YA. (C) PCR linearity determination with the γ promoter-amplifying primers. About 2 ng of anti-NF-YA antibody-immunoprecipitated DNA and about 4 ng of input DNA were used as templates. NF-Y-IP: anti-NF-YA-antibody immunoprecipitation; Non-specific-IP: nonspecific IgG immunoprecipitation. (D) Linearity determination in duplex PCR with the following primer combinations: γ promoter-amplifying primers plus β major promoter-amplifying primers; mouse HS2 region (Mo HS2)-amplifying primers plus γ promoter-amplifying primers; mouse HS2 region (Mo HS2)-amplifying primers plus human HS2 region (Hu HS2)-amplifying primers; mouse HS2 region (Mo HS2)-amplifying primers plus human HS3 region (Hu HS3)-amplifying primers. Note the constancy of the ratios of the signal over the internal control.

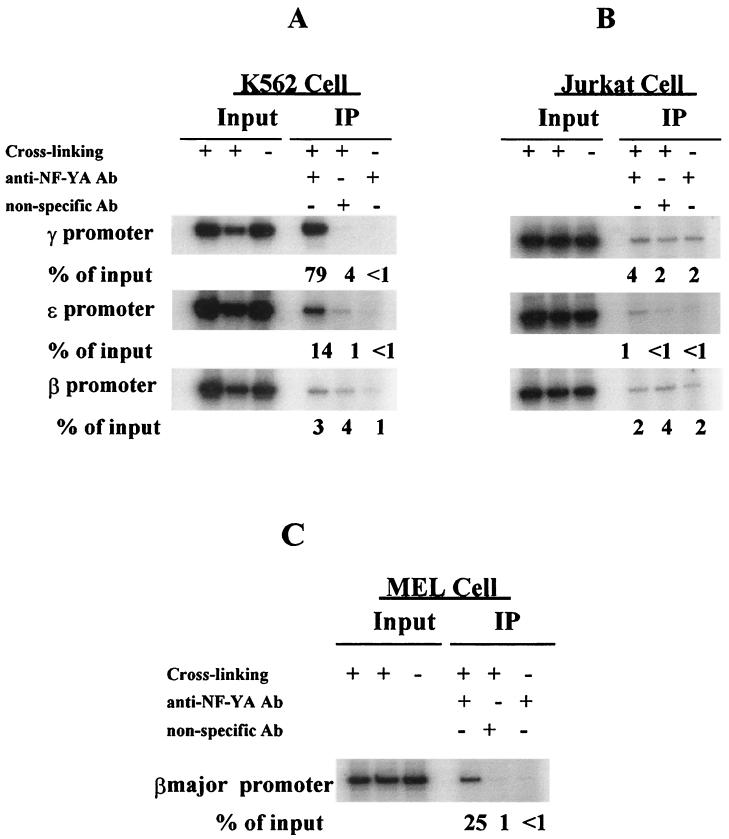

Using this ChIP assay system, we examined the recruitment of NF-Y to the endogenous ɛ, γ, or β promoter of K562 cells and Jurkat cells (a lymphocyte T-cell line) and the βmajor promoter of MEL cells. Representative results are shown in Fig. 3. In K562 cells in which the ɛ and γ genes are transcribed while the β gene is transcriptionally silent, NF-Y bound to the γ and ɛ promoters (Fig. 3A) but not to the β promoter. In Jurkat cells, in which all the globin genes are silent, there was no significant binding of NF-Y to any of the globin gene promoters examined (Fig. 3B). In MEL cells, NF-Y was recruited to the βmajor promoter (Fig. 3C). These results suggested that NF-Y binds to β-like globin gene promoters in vivo and that the recruitment of NF-Y to the β-like globin genes occurs in an erythroid cell-specific fashion. The binding of NF-YA to the γ promoter was at least fivefold stronger that that to the ɛ promoter (Fig. 3A). This increase in binding to the γ versus the ɛ promoter (observed in four additional experiments) may occur because there are two endogenous γ genes each containing two CAAT boxes while there is only one CAAT box in the single ɛ gene promoter.

FIG. 3.

NF-Y binds to the γ gene promoter in vivo. ChIP assays were performed with NF-Y-specific polyclonal antibodies. Cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde before soluble chromatin complex was produced. Input DNA (about 5 ng) and antibody-bound DNA (about 2 ng) were amplified by PCR and quantified with a PhosphorImager and Image Quant software. Un-cross-linked chromatin and nonspecific antibody (normal goat IgG) were used as control for background determination. Immunoprecipitated (IP) DNA levels were expressed as a percentage of the corresponding input DNA, respectively. (A) NF-Y specifically binds to the promoters of the γ and ɛ genes but not of the β gene of K562 cells. (B) NF-Y does not bind to the promoters of the endogenous β-like globin genes of Jurkat cells. (C) NF-Y binds to the βmajor gene promoter of MEL cells.

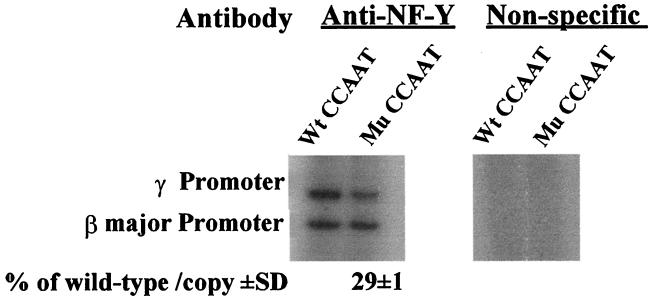

To test in vivo whether NF-Y binds to the γ gene promoter through the duplicated CCAAT boxes, we examined whether the CCAAT-to-GATCT mutation of the duplicated CCAAT box impairs the recruitment of NF-YA to the γ promoter. Because it is difficult to discriminate the transfected γ promoter from the endogenous γ promoter in K562 cells, we used MEL cell pools, which were stably transfected with the wild-type or the CCAAT box-mutated construct (Table 2). MEL cells stably transfected with either μLCR(−382)Aγ (wild type) or the μLCR(−382)Aγ(mCCAAT) construct were subjected to ChIP assays as described in Materials and Methods. Duplex PCR was performed, and the recruitment of NF-Y to the endogenous βmajor promoter was used as internal control. The relative recruitment level of NF-Y to the CCAAT box-mutated γ promoter was expressed as a percentage of its recruitment level to the wild-type γ promoter and was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Nonspecific antibody (normal IgG) was used as a negative control and for background determination. These experiments revealed that the reduction of γ gene transcription by the CCAAT-to-GATCT mutation was associated with reduction in the binding of NF-YA to the γ gene promoter. The results of a representative experiment using pool 4 (Table 2) are shown in Fig. 4. The level of γ mRNA in this pool was 22.5% of that in the control MEL cells transfected with the wild-type γ gene construct. The recruitment level of the mutant γ promoter by NF-Y was only 29% of that of the wild-type γ promoter. These results suggest that an intact CCAAT box is required for NY-Y binding to the γ promoter in vivo.

FIG. 4.

The CCAAT-to-GATCT mutation of the duplicated CCAAT box severely disrupts the recruitment of NF-Y to the γ gene promoter in stably transfected MEL cells. MEL cells stably transfected with either μLCR(−382)Aγ (wild type) or the μLCR(−382)Aγ(mCCAAT) construct were subjected to ChIP assays (as described in Materials and Methods). MEL cell pool 4 of Table 2, which contains the CCAAT box-mutated construct, was used. The recruitment level of NF-Y to the transfected γ gene promoter was assessed by duplex PCR in which the recruitment of NF-Y to the endogenous β major promoter was used as the internal control. The relative recruitment level of NF-Y to the mutated γ promoter was expressed as a percentage of its recruitment level of the wild-type γ promoter, which was calculated by the formula (γm-ChIP/γm-copy) / (γw-ChIP/γw-copy) × (βw-ChIP/βm-ChIP), where γm-ChIP is the intensity of the anti-NF-Y ChIP band of the mutant γ promoter, γm-copy is the copy number of the mutant γ promoter in the MEL cell pool, γw is the wild-type γ promoter, and βw-ChIP and βm-ChIP are the intensities of the anti-NF-Y ChIP band of the endogenous βmajor promoter of the MEL cell pool containing the wild-type or the CCAAT-box mutated γ construct, respectively. Non-specific antibody (normal IgG) was used as the negative control and for background determination. The mean value (percentage of wild type/copy ± standard deviation [SD]) of three independent experiments is shown.

Disruption of the γ gene CCAAT box affects the recruitment of the basal transcriptional machinery.

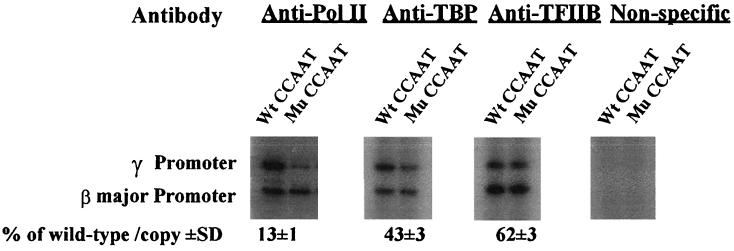

To investigate the relationship between NF-Y and the basal transcription machinery in vivo, we examined whether the mutation of the duplicated CCAAT box affects the recruitment of three components of the basal transcription machinery: RNA polymerase II (Pol II), TFIID (TATA-binding protein [TBP]), and TFIIB. The recruitment of RNA Pol II is correlated with the transcription level, and it is known that the binding of TFIID (TBP) is a key step in the assembly of preinitiation complex and that TFIIB is a bridge between TFIID and RNA Pol II (27). As shown in Fig. 5, disruption of the γ CCAAT box reduced the recruitment of Pol II and TBP to 13% ± 1% and 43% ± 3% of that of the control, respectively. The recruitment of TFIIB was reduced to 62% ± 3% of that of the control. These results suggested that disruption of the duplicated CCAAT box negatively affects the recruitment of the basal transcriptional machinery to the Aγ gene promoter in vivo. Since, as shown above, NF-Y is the transcriptional factor binding to the γ CCAAT box, these results indirectly suggest that binding of NF-Y to the CCAAT box may facilitate the recruitment of the basal transcriptional machinery to the γ gene promoter.

FIG. 5.

The CCAAT-to-GATCT mutation of the duplicated CCAAT box reduces the recruitment of the basal transcription machinery to the γ gene promoter in stably transfected MEL cells. MEL cell pool 4 of Table 2 was subjected to ChIP assays with antibodies against RNA Pol II, TFIID (TBP), and TFIIB. The relative recruitment level of a factor to the CCAAT box-mutated γ promoter was expressed as a percentage of its recruitment level to the wild-type γ promoter and was calculated as described in the legend of Fig. 4. The mean values (percentage of wild type/copy ± standard deviation [SD]) of three independent experiments are shown.

Disruption of the duplicated CCAAT box region may affect communication between the LCR and the proximal γ gene promoter.

It has been shown that the interaction between the β-globin LCR and the proximal promoter elements plays a crucial role in the regulation of β-like globin genes (13). It has also been suggested that the formation of the LCR complex may be influenced by the proximal promoter of the globin genes (17, 28). NF-E2 and GATA-1 have been considered to be key components of the LCR complex (4), and the activity of a CBP/p300-containing coactivator, which is mediated by NF-E2, has been shown to contribute to LCR function (10). We therefore used the ChIP assay to test whether the CCAAT box mutation affects the binding of transcriptional factors in the LCR and in the proximal γ promoter region.

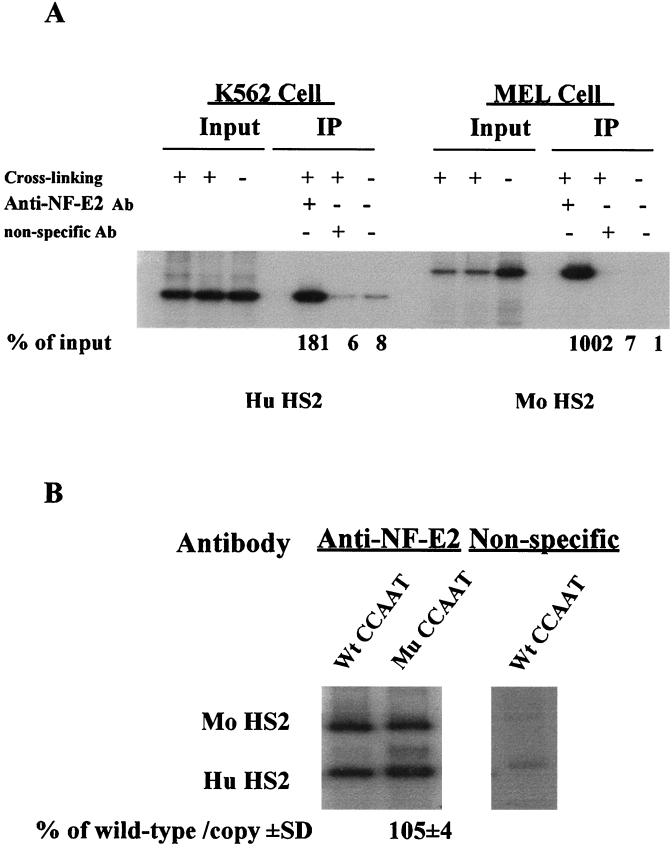

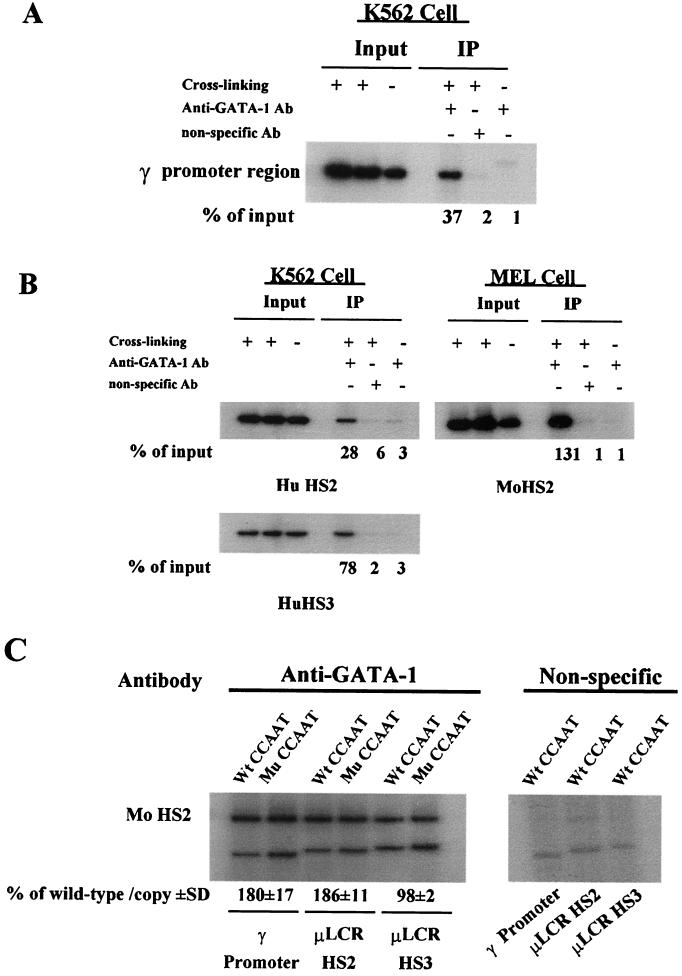

We first used an antibody against NF-E2/p45 to detect the recruitment of NF-E2 to the HS2 core region. In agreement with the results of Forsberg et al. (9), we found that NF-E2 was recruited to the HS2 core region of the endogenous LCR in both K562 and MEL cells (Fig. 6A). However, mutation of the duplicated CCAAT box had no apparent effect on the recruitment of NF-E2 to the transfected HS2 core region in stably transfected MEL cells (Fig. 6B). We subsequently used a GATA-1-specific antibody to examine the recruitment of GATA-1 to the core regions of HS2 and HS3 of the endogenous LCR and to the γ promoter region. As shown in Fig. 7A and B, GATA-1 was recruited to the core regions of the endogenous HS2 and HS3 and the proximal γ gene promoter region in K562 cells. GATA-1 was also recruited to the HS2 core region of the endogenous LCR in MEL cells (Fig. 7B). The mutation of the duplicated CCAAT increased the binding of GATA-1 to the transfected γ gene promoter to 179% ± 17% of the control and the binding to the HS2 region to 186% ± 11% of the control (Fig. 7C). The recruitment of GATA-1 to the transfected HS3 region was not significantly affected by the mutation of the duplicated CCAAT box (Fig. 7C).

FIG. 6.

In vivo binding of NF-E2 to HS2 of the endogenous LCR and the μLCR of the mutant CCAAT construct. (A) In vivo recruitment of NF-E2 to the HS2 core region of the endogenous LCR in K562 and MEL cells. ChIP assays were performed using NF-E2/p45-specific antibody as described in Materials and Methods and in the legend to Fig. 2. The level of the immunoprecipitated (IP) DNA was expressed as a percentage of the corresponding input DNA. (B) The CCAAT box mutation does not affect the binding of NF-E2 to the HS2 core region of the transfected μLCR in stably transfected MEL cells. MEL cell pool 4 of Table 2 was subjected to ChIP assays with antibodies against NF-E2/p45. The relative recruitment level of NF-E2 to the μLCR HS2 core region of the CCAAT box-mutated γ construct was expressed as percentage of the recruitment level to the μLCR HS2 core region of the wild-type γ construct. The recruitment of NF-E2 to the HS2 core region of the endogenous mouse LCR was used as an internal control. The relative recruitment level was calculated as described in the legend to Fig. 4. The mean value (percentage of wild type/copy ± standard deviation [SD]) of three independent experiments is shown.

FIG. 7.

In vivo binding of GATA-1 to the γ gene promoter and to the core regions of HS2 and HS3 of the endogenous and transfected LCR. ChIP assays were performed with GATA-1-specific antibody. (A) Recruitment of GATA-1 to the endogenous γ gene promoter of K562 cells. (B) Recruitment of GATA-1 to the HS2 and HS3 core regions of the endogenous LCR of K562 cells and to the HS2 core region of MEL cells. (C) The mutation of the duplicated CCAAT box significantly increases the recruitment of GATA-1 to the μLCR HS2 core region and the γ gene promoter but does not affect the recruitment of GATA-1 to the μLCR HS3 core region. MEL cell pool 4 of Table 2 was used. The relative recruitment levels were calculated as described in the legend to Fig. 4. The recruitment of GATA-1 to the HS2 core region of the endogenous mouse LCR was used as an internal control. The mean values (percentage of wild type/copy ± standard deviation [SD]) of three independent experiments are shown.

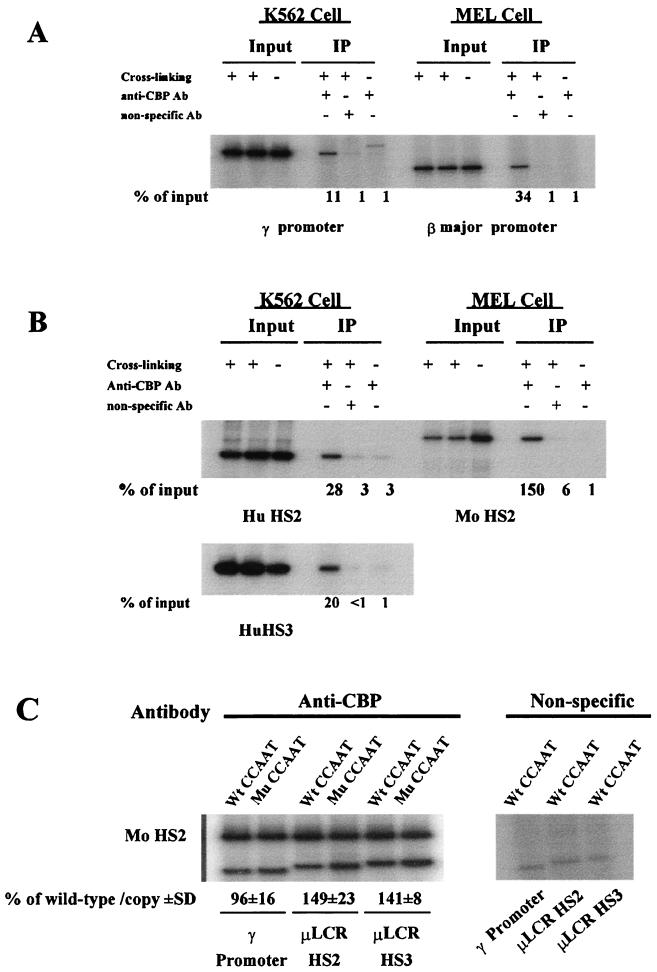

Since formaldehyde can also cross-link tightly interacting proteins, the ChIP assay can also detect the recruitment of the cofactor CBP/p300 to the LCR complex and the proximal γ promoter complex. An antibody against CBP/p300 was used. As shown in Fig. 8A and B, CBP/p300 was recruited to the core regions of the endogenous HS2 and HS3 and the proximal promoter region of the endogenous γ gene of K562 cells. CBP/p300 was also recruited to the endogenous HS2 core region of the LCR in MEL cells (Fig. 8B). The mutation of the duplicated CCAAT box had no apparent effect on the recruitment of CBP/p300 to the transfected γ gene promoter region in the stably transfected MEL cells (Fig. 8C) but increased the recruitment of CBP/p300 to the core regions of HS2 and HS3 to 149% ± 23% and 141% ± 8%, respectively, of that of the control (Fig. 8C).

FIG. 8.

Recruitment of CBP/p300 to the γ and β gene promoters and to the core regions of HS2 and HS3 of the endogenous and transfected LCR. (A) Recruitment of CBP/p300 to the endogenous γ gene promoter region of K562 cells and the β major gene promoter of MEL cells. (B) Recruitment of CBP/p300 to the HS2 and HS3 core region of the endogenous LCR of K562 cells and to the HS2 core region of MEL cells. (C) The mutation of the duplicated CCAAT box does not apparently affect the recruitment of CBP/p300 to the γ gene promoter region but significantly increases the recruitment of CBP/p300 to the HS2 and HS3 core region of the μLCR in stably transfected MEL cells. MEL cell pool 4 of Table 2 was used. The relative recruitment levels were calculated as described in the legend to Fig. 4. The recruitment of CBP/p300 to the HS2 core region of the endogenous mouse LCR was used as an internal control. The mean values (percentage of wild type/copy ± standard deviation [SD]) of three independent experiments are shown.

DISCUSSION

NF-Y binding to the duplicated CCCAT box is required for γ gene expression. In this study we used a γ gene construct that is truncated to position −382 of the Aγ promoter and is characterized by high expression in fetal and adult cells of transgenic mice. High γ gene expression is also characteristic of erythroid cell lines transfected with this construct. Transfection of cell lines or production of transgenic lines carrying −382 Aγ genes with mutated proximal γ gene promoter elements provides a convenient assay to assess the contribution of such elements on γ gene regulation. Thus, if an element is necessary for γ gene expression, its mutation in the context of the −382 Aγ gene results in a decline of γ gene expression, allowing a quantitative measurement of the effects of the mutation. We used this system to investigate the developmental role of the duplicated CCAAT box. Our data showed that a mutation of the duplicated CCAAT box that abolishes protein binding to this regulatory motif severely reduces γ gene expression in stably transfected K562 and MEL cells. Furthermore, we demonstrated that NF-Y is recruited to both the endogenous and exogenous γ gene promoters through the CCAAT boxes and that a CCAAT-to-GATCT mutation of the duplicated CCAAT box disrupts the NF-Y binding. Taken together, these results suggest that recruitment of NF-Y to the duplicated CCAAT box is required for γ gene expression. This conclusion is in agreement with the findings of Liberati et al. (19).

If, as indicated by the in vitro assays, NF-Y binding to the CCAAT box is strictly sequence specific, the CCAAT box mutation should have completely disrupted the recruitment of NF-Y. However, the in vivo binding of NF-Y was not totally abolished after the mutation of both CCAAT boxes. It has been suggested that the histone-like structure of NF-YB–NF-YC plays a role in NF-Y binding to a nucleosome template through their association with core histones and that in some cases the location of CCAAT box might affect the NF-Y binding affinity (23). It is therefore possible that in addition to the CCAAT motif itself, the topological conformation of the CCAAT region may contribute to NF-Y binding in vivo so that some degree of binding takes place even when the CCAAT box is mutated.

NF-Y recruitment contributes to the formation of an open chromatin structure of the γ gene promoter.

NF-Y is a heterotrimer consisting of NF-YA, NF-YB, and NF-YC; the last two proteins show similarity to histones H2B and H2A, respectively. It has been reported that the NF-Y trimer is able to interact with coactivators (18) and is capable of preventing the formation of nucleosomes in vitro (23). It has also been reported that NF-Y directly interacts with TFIID in vitro (2). Using restriction enzyme accessibility assays, we have shown that the local chromatin structure, or at least the local DNA-protein architecture in the γ promoter region, changed to a more inaccessible status after mutation of the duplicated CCAAT boxes. The decreased chromatin accessibility does not appear to represent a nonspecific effect of γ promoter mutations, because we have found that CACCC box deletions or TATA box mutations fail to affect γ promoter accessibility (or γ promoter activity) in primitive erythroid cells (Z. Duan et al., unpublished data).

The ChIP assays suggested that the disruption of NF-Y recruitment interferes with the assembly of the basal transcriptional machinery. These results raise the possibility that NF-Y plays a role in the formation of transcriptionally active chromatin structure and the assembly of basal transcriptional machinery in vivo. This suggestion is in agreement with the findings from studies with Xenopus (18), which showed that NF-Y could preset chromatin and facilitate the recruitment of coactivators to modulate transcriptional activity in vivo. Binding of other proteins in addition to NF-YA is expected to contribute to the accessibility of the γ promoter. In other studies we have found that CACCC box deletions, in contrast to their lack of effects in primitive cells, reduce γ promoter activity and γ promoter accessibility in definitive erythroid cells (Duan et al., unpublished); such results point to a contribution by the γ CACCC box to γ promoter accessibility in definitive cells. Furthermore, several studies indicate that EKLF binding on the β gene CACCC box is required for the opening of the chromatin of the β globin gene promoter (1).

The binding of GATA-1 to the γ gene promoter region increased after the mutation of the duplicated CCAAT box. Three typical GATA-1 motifs are present in the proximal promoter: one in −220 γ and two around −175 γ. In addition, gel shift assays have shown that GATA-1 binds weakly to the duplicated CCAAT box region (3, 15, 21). A suggestion that GATA-1 binding to the duplicated CCAAT box region functions as γ gene repressor (3, 21) was not supported by later experiments (29). It is possible that NF-Y and GATA-1 bind competitively to the duplicated CCAAT box region and that the mutation of the two CCAAT motifs, by severely impairing the binding of NF-Y, increases the probability of binding of GATA-1 to this region. Since both NF-Y and GATA-1 can interact with the cofactor CBP/p300 (4, 20), the increased binding of GATA-1 may explain why the level of CBP/p300 recruitment to the proximal γ gene promoter remained unchanged despite the decreased binding of NF-Y on the mutated γ CCAAT boxes.

The recruitment of NF-Y to the duplicated CCAAT box may influence the assembly of the LCR complex.

The mechanism whereby the LCR activates the downstream globin gene remains a matter of speculation. It has been proposed that the HSs composing the LCR interact with each other to form a complex, called the holocomplex (36), which interacts with the downstream globin genes by looping out the intergenic sequences (11). Two other models, a tracking model and a facilitating model, have also been proposed (5, 34). Indirect evidence in support of the formation of an LCR holocomplex include data from deletions of the core elements of HSs of the LCR (6, 24). Presumably the LCR complex is formed through the recruitment of sequence-specific factors and cofactors which interact with each other to produce a developmentally specific conformation of the LCR. The mechanism whereby this complex interacts with the downstream globin gene promoters is also speculative. Presumably, transcriptional factors and cofactors binding in the motifs of the LCR and in the globin gene promoters participate in these promoter-LCR interactions. Several factors and cofactors such as GATA-1 (33), NF-E2 (10, 33), EKLF (12), and CBP/p300 (10) have been suggested as components of the LCR complex (reviewed in reference 25). CBP/p300 is important to both primitive and definitive hematopoiesis (4) and can be recruited to the LCR through protein-protein interactions with LCR-binding and sequence-specific factors. For instance, CBP/p300 can be recruited to the HS2 core region through the NF-E2 binding site (10). Also, GATA-1 (16) and EKLF (37) interact with CBP/p300 in vitro. In agreement with these studies, our data showed that NF-E2, GATA-1, and CBP/p300 are indeed recruited to the β globin LCR in vivo.

Experimental evidence has also been accumulating in support of the notion that there is communication between the LCR and the globin gene promoter in vivo. Using a protein position identification with nuclease tail (pin*point) assay, Lee et al. demonstrated that a TATA box, but not a CACCC box, mutation in the β promoter affects the recruitment of EKLF to HS2 and that both mutations reduce the recruitment of EKLF to HS3 (17). There is also evidence for communications between the ɛ gene promoter and HS2. Mutation of GATA-1 or CACCC site in the ɛ promoter resulted in reduced accessibility at HS2, and HS2-dependent promoter remodeling was diminished when the ɛ gene TATA box was mutated (22). Our results add to this evidence by showing that a γ CCAAT mutation can affect the in vivo recruitment of GATA-1 and CBP/p300 to HS2 and HS3. It is difficult to explain the specific quantitative changes we observed in factor binding to the LCR. It is likely that when the CCAAT box is mutated, there is a decreased probability of interaction between the γ promoter and the LCR. The LCR may adapt to different conformations when it interacts or fails to interact with the γ promoter, and this may be reflected in the quantitative changes in the binding of GATA-1 and CBP/p300 we have observed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Zhonghua Hu and Hemei Han for expert technical assistance.

These studies were supported by NIH grants HL20899 and DK45365.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong J A, Bieker J J, Emerson B M. A SWI/SNF-related chromatin remodeling complex, E-RC1, is required for tissue-specific transcriptional regulation by EKLF in vitro. Cell. 1998;95:93–104. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81785-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellorini M, Lee D K, Dantonel J C, Zemzoumi K, Roeder R G, Tora L, Mantovani R. CCAAT binding NF-Y-TBP interactions: NF-YB and NF-YC require short domains adjacent to their histone fold motifs for association with TBP basic residues. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2174–2181. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.11.2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry M, Grosveld F, Dillon N. A single point mutation is the cause of the Greek form of hereditary persistence of fetal haemoglobin. Nature. 1992;358:499–502. doi: 10.1038/358499a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blobel G A. CREB-binding protein and p300: molecular integrators of hematopoietic transcription. Blood. 2000;95:745–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bulger M, Goudine M. Looping versus linking: toward a model for long-distance gene activation. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2465–2477. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bungert J, Dave U, Lim K-C, Lieuw K H, Shavit J A, Liu Q, Engel J D. Synergistic regulation of human β-globin gene switching by locus control region elements HS3 and HS4. Genes Dev. 1995;9:3083–3096. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.24.3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen H, Lin R J, Xie W, Wilpitz D, Evans R M. Regulation of hormone-induced histone hyperacetylation and gene activation via acetylation of an acetylase. Cell. 1999;98:675–686. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forrester W C, Thompson C, Elder J T, Groudine M. A developmentally stable chromatin structure in the human β-globin gene cluster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1359–1363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.5.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forsberg E C, Downs K M, Bresnick E H. Direct interaction of NF-E2 with hypersensitive site 2 of the β-globin locus control region in living cells. Blood. 2000;96:334–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forsberg E C, Johnson K, Zaboikina T N, Mosser E A, Bresnick E H. Requirement of an E1A-sensitive coactivator for long-range transactivation by the β-globin locus control region. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26850–26859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraser P, Grosveld F. Locus control regions, chromatin activation and transcription. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:361–365. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gillemans N, Tewari R, Lindeboom F, Rottier R, de Wit T, Wijgerde M, Grosveld F, Philipsen S. Altered DNA-binding specificity mutants of EKLF and Sp1 show that EKLF is an activator of the β-globin locus control region in vivo. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2863–2873. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gribnau J, Diderich K, Pruzina S, Calzolari R, Fraser P. Intergenic transcription and developmental remodeling of chromatin subdomains in the human β-globin locus. Mol Cell. 2000;5:377–386. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80432-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grosveld F, Antoniou M, Berry M, de Boer E, Dillon N, Ellis J, Fraser P, Hurst J, Imam A, Meijer D, Philipson S, Pruzina S, Strouboulis J, Whyatt D. Regulation of human globin gene switching. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1993;58:7–13. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1993.058.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gumucio D L, Rood K L, Gray T A, Riordan M F, Sartor C I, Collins F S. Nuclear proteins that bind the human γ-globin gene promoter: alterations in binding produced by point mutations associated with hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:5310–5322. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.12.5310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hung H L, Lau J, Kim A Y, Weiss M J, Blobel G A. CREB-binding protein acetylates hematopoietic transcription factor GATA-1 at functionally important sites. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3496–3505. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J S, Lee C H, Chung J H. The β-globin promoter is important for recruitment of erythroid Kruppel-like factor to the locus control region in erythroid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10051–10055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Q, Herrler M, Landsberger N, Kaludov N, Ogryzko V V, Nakatani Y, Wolffe A P. Xenopus NF-Y pre-sets chromatin to potentiate p300 and acetylation-responsive transcription from the Xenopus hsp70 promoter in vivo. EMBO J. 1998;17:6300–6315. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liberati C, Ronchi A, Lievens P, Ottolenghi S, Mantovani R. NF-Y organizes the γ-globin CCAAT boxes region J. Biol Chem. 1998;273:16880–16889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mantovani R. The molecular biology of the CCAAT-binding factor NF-Y. Gene. 1999;239:15–27. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mantovani R, Malgaretti N, Nicolis S, Ronchi A, Giglioni B, Ottolenghi S. The effects of HPFH mutations in the human γ-globin promoter on binding of ubiquitous and erythroid specific nuclear factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:7783–7797. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.16.7783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDowell J C, Dean A. Structural and functional cross talk between a distant enhancer and the ɛ-globin gene promoter shows interdependence of the two elements in chromatin. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7600–7609. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motta M C, Caretti G, Badaracco G F, Mantovani R. Interactions of the CCAAT-binding trimer NF-Y with nucleosomes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1326–1333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navas P A, Peterson K R, Li Q, Skarpidi E, Rohde A, Shaw S E, Clegg C H, Asano H, Stamatoyannopoulos G. Developmental specificity of the interaction between the locus control region and embryonic or fetal globin genes in transgenic mice with an HS3 core deletion. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4188–4196. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orkin S H. Transcription factors that regulate lineage decisions. In: Stamatoyannopoulos G, Majerus P W, Perlmutter R M, Varmus H, editors. Molecular basis of blood diseases. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: The W. B. Saunders Publishing Co.; 2000. pp. 80–102. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orlando V, Strutt H, Paro R. Analysis of chromatin structure by in vivo formaldehyde cross-linking. Methods. 1997;11:205–214. doi: 10.1006/meth.1996.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pugh B F. Mechanisms of transcription complex assembly. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:303–311. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reitman M, Lee E, Westphal H, Felsenfeld G. An enhancer/locus control region is not sufficient to open chromatin. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3990–3998. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ronchi A, Berry M, Raguz S, Imam A, Yannoutsos N, Ottolenghi S, Grosveld F, Dillon N. Role of the duplicated CCAAT box region in γ-globin gene regulation and hereditary persistence of fetal haemoglobin. EMBO J. 1996;15:143–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skarpidi E, Vassilopoulos G, Stamatoyannopoulos G, Li Q. Comparison of expression of human globin genes transferred into mouse erythroleukemia cells and in transgenic mice. Blood. 1998;92:3416–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stamatoyannopoulos G, Grosveld F. Hemoglobin switching. In: Stamatoyannopoulos G, Majerus P W, Perlmutter R M, Varmus H, editors. Molecular basis of blood diseases. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: The W. B. Saunders Publishing Co.; 2001. pp. 135–182. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stamatoyannopoulos G, Josephson B, Zhang J W, Li Q. Developmental regulation of human γ-globin genes in transgenic mice. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7636–7644. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stamatoyannopoulos J A, Goodwin A, Joyce T, Lowrey C H. NF-E2 and GATA binding motifs are required for the formation of DNase I hypersensitive site 4 of the human β-globin locus control region. EMBO J. 1995;14:106–116. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb06980.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tuan D, Kong S, Hu K. Transcription of the hypersensitive site HS2 enhancer in erythroid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11219–11223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tuan D, Solomon W, Li Q, London I M. The “β-like-globin” gene domain in human erythroid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:6384–6388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.19.6384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wijgerde M, Grosveld F, Fraser P. Transcription complex stability and chromatin dynamics in vivo. Nature. 1995;377:209–213. doi: 10.1038/377209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang W, Bieker J J. Acetylation and modulation of erythroid Kruppel-like factor (EKLF) activity by interaction with histone acetyltransferases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9855–9860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]