Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: acute lymphoblastic leukemia, CDK4/6 inhibitors, CDKN2A, inherited variants, predispose

Objective

Genetic alterations in CDKN2A tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 9p21 confer a predisposition to childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Genome-wide association studies have identified missense variants in CDKN2A associated with the development of ALL. This study systematically evaluated the effects of CDKN2A coding variants on ALL risk.

Methods

We genotyped the CDKN2A coding region in 308 childhood ALL cases enrolled in CCCG-ALL-2015 clinical trials by Sanger Sequencing. Cell growth assay, cell cycle assay, MTT-based cell toxicity assay, and western blot were performed to assess the CDKN2A coding variants on ALL predisposition.

Results

We identified 10 novel exonic germline variants, including 6 missense mutations (p.A21V, p.G45A and p.V115L of p16INK4A; p.T31R, p.R90G, and p.R129L of p14ARF) and 1 nonsense mutation and 1 heterozygous termination codon mutation in exon 2 (p16INK4A p.S129X). Functional studies indicate that five novel variants resulted in reduced tumor suppressor activity of p16INK4A, and increased the susceptibility to the leukemic transformation of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Compared to other variants, p.H142R contributes higher sensitivity to CDK4/6 inhibitors.

Conclusion

These findings provide direct insight into the influence of inherited genetic variants at the CDKN2A coding region on the development of ALL and the precise clinical application of CDK4/6 inhibitors.

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common childhood cancer [1,2]. Studies in the past decade have shown that inherited genetic variants (germline) are strongly associated with the predisposition to ALL in children. In particular, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified susceptibility loci for B-cell ALL (B-ALL) in several genes, including ARID5B, IKZF1, CEBPE, PIP4K2A-BMI1, GATA3, CDKN2A/2B, LHPP, ELK3, BAK1, IGF2BP1, USP7, IKZF3, ERG, TP63, and SP4 [3–5]. Most of these variants are intronic and may not be directly functional; however, more recently, a coding variant in CDKN2A/2B has been reported to account for influencing susceptibility to ALL in children [6].

CDKN2A/2B locus on 9p21 encodes for p16INK4A/p14ARF and p15INK4B, respectively. Both p16INK4A and p15INK4B specifically inhibit cyclin/Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) complexes that block cell division during the G1/S phase of the cell cycle, whereas p14ARF prevents degradation of p53 by interacting with the MDM2 protein [7–9]. Recently, the Sherr group has reported N-terminally truncated smArf, a distinct polypeptide encoded by Arf mRNA, localizes to mitochondria and triggers autophagy and mitophagy [10]. Thus, CDKN2A/2B is an important regulator of cell growth regulation and apoptosis, and loss of cell proliferation control and regulation of the cell cycle are known to be critical to cancer development [11–13]. Recent studies have reported the frequency of CDKN2A/2B deletion to be more than 30% in pediatric B-ALL, with relevance to ALL susceptibility and poor prognosis [7,8,13]. Sherborne et al. have demonstrated that common variation at 9p21.3 (rs3731217, intron 1 of CDKN2A) influences ALL risk (odds ratio = 0.71, P = 3.01 × 10−11), irrespective of cell lineage [14]. Xu et al. have functionally identified that CDKN2A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs3731249 (p.A148T, coding sequence of p16INK4A) significantly accelerates Ba/F3 cells leukemic transformation by BCR-ABL1, indicating that the reduced tumor suppressor function of p16INK4A p.A148T variant [6]. However, questions remain whether other coding variants within CDKN2A gene might also contribute to ALL leukemogenesis.

In the present study, we genotyped CDKN2A exons in our CCCG-ALL-2015 study cohort to screen other exonic CDKN2A SNPs associated with ALL pathogenesis, experimentally explored the effects of exonic CDKN2A SNPs on leukemic transformation and their response to CDK4/6 inhibitors (palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib), and characterized the underlying mechanisms.

Results

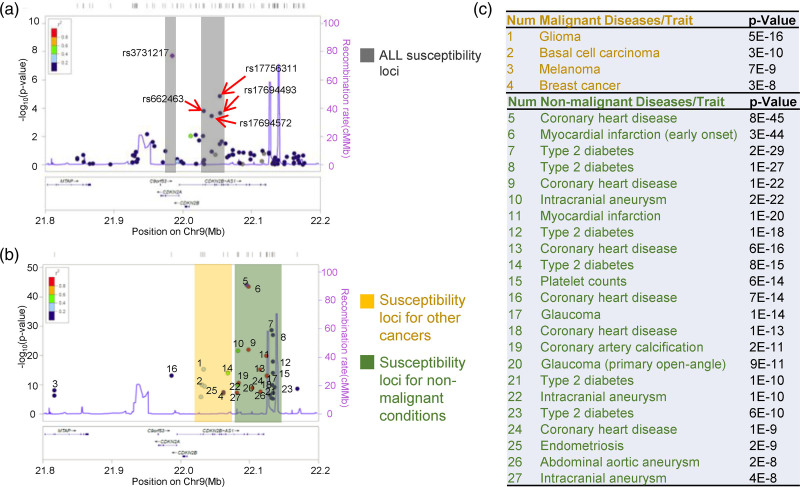

Distinctive genomic regions at CDKN2A/2B loci associated with cancer and noncancer diseases/traits

To systemically explore the role of CDKN2A/2B loci in disease susceptibility, we retrieved all the GWAS hits from NHGRI-EBI Catalog and other ALL hits from Yang’s and Houlston’s groups [6,14–17]. Totally 510 disease/traits associated SNPs records were collected (Supplementary Table 1, Supplemental digital content 1, http://links.lww.com/FPC/B407). Then, we performed regional association analysis and plotted the SNPs P value against ±1.6 mb flanked CDKN2A/2B loci by using Locus zoom (http://locuszoom.org/) [18]. Among 27 diseases/traits analyzed, distinctive cancer and noncancer susceptibility SNPs pattern were observed (Fig. 1). The cancer-associated (leukemia, melanoma, breast cancer, glioma, and basal cell carcinoma) SNPs were found to locate in proximal upstream of the CDKN2A/2B promoter region (chr9:22090000-22140000), while noncancer-associated SNPs were located distal upstream of the CDKN2A/2B promoter region (chr9:22030000-22080000), suggesting that different genomic regions in CDKN2A/2B-AS1 loci responsible for distinctive diseases susceptibility. In regard to ALL, the susceptibility SNPs were resided in the cancer-associated genomic region, with rs3731217 top-ranked association in the CDKN2A intronic region, indicating the important role of CDKN2A in ALL development.

Fig. 1.

GWAS Catalog associations for CDKN2A/2B loci plotted across Ch9:21.8–22.2 MB. Association results [−log10(P value)] for ALL susceptibility loci (a), susceptibility loci of other cancers, and susceptibility loci of nonmalignant conditions (b) are depicted with regards to the physical location of SNPs. (c) Lists of SNPs plotted in (b). SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

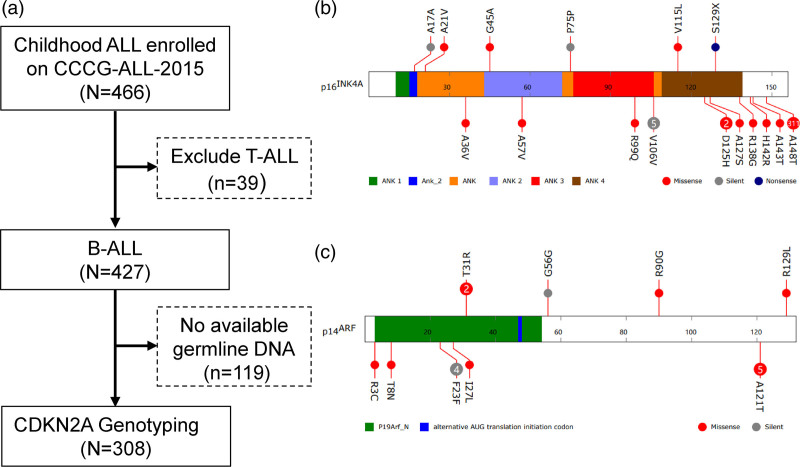

Genotyping of CDKN2A in Chinese children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

To further probe the role of CDKN2A exonic variations in childhood ALL susceptibility, we next sequenced the coding region of the CDKN2A in germline DNA from 308 childhood B-ALL cases enrolled onto CCCG-ALL-2015 clinical trials (ChiCTR-IPR-14005706) in Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center (GWCMC, Table 1 and Fig. 2a). We did not observe germline insertions or deletions at the CDKN2A locus, but identified ten novel germline exonic variants, including six missense mutations (p.A21V, p.G45A, and p.V115L of p16INK4A coding sequence; p.T31R, p.R90G, and p.R129L in p14ARF coding sequence) and one heterozygous termination codon mutation in exon 2 (p.S129X), resulting in the production of truncated p16INK4A (Fig. 2b and c and Supplementary Figure 1, Supplemental digital content 2, http://links.lww.com/FPC/B408). The frequency of ALL patients in our Han Chinese cohort harboring the CDKN2A germline mutation was 3.6% (11/308), and we did not identify p16INK4A p.A148T variant, which occurred frequently in European descents (12.9%, 311/2407) [6]. Integrating the variants reported by Xu et al. [6], we noticed that most p16INK4A variants are located in C-terminus, followed by ANK domains (Fig. 2). Up to date, only the leukemic transformation potential of p16INK4A p.A148T has been experimentally validated, while the function of other twelve exonic p16INK4A variants has not been demonstrated by any model.

Table 1.

Characteristics of enrolled patients from CCCG-ALL-2015 cohort

| Characteristics | Group | No. patients (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ≥1, <10 | 291 (94.5) |

| <1, ≥10 | 17 (5.5) | |

| Gender | Female | 120 (39.0) |

| Male | 188 (61.0) | |

| FAB subtype | L1 | 66 (21.4) |

| L2 | 179 (58.1) | |

| L3 | 62 (20.1) | |

| Not determined | 1 (0.3) | |

| WBC (×109/L) | <50 | 257 (83.4) |

| ≥50 | 51 (16.6) | |

| Liver | Not detected | 115 (37.3) |

| <2 cm | 27 (8.8) | |

| ≥2, <5 cm | 139 (45.1) | |

| ≥5 cm | 27 (8.8) | |

| Spleen | Not detected | 172 (55.8) |

| <2 cm | 28 (9.1) | |

| ≥2, <5 cm | 84 (27.3) | |

| ≥5 cm | 24 (7.8) | |

| NCI Risk | Standard | 246 (79.9) |

| High | 62 (20.1) | |

| Risk stratified by CCCG-ALL-2015 | Low | 160 (51.9) |

| Intermediate | 146 (47.4) | |

| High | 2 (0.6) | |

| MRD19 | <0.01% | 107 (34.7) |

| ≥0.01% | 177 (57.5) | |

| MRD46 | <0.01% | 256 (83.1) |

| ≥0.01% | 52 (16.9) | |

| Relapse | No | 289 (93.8) |

| Yes | 19 (6.2) |

Fig. 2.

Germline coding variants of CDKN2A in children with ALL. (a) Flowchart of CDKN2A genotyping. CDKN2A Exon variants were identified by Sanger sequencing in 308 ALL cases enrolled onto CCCG-ALL-2015 in Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center (GWCMC). (b) and (c), Exonic variants are classified as silent, missense or nonsense, and are mapped to two distinct open reading frames at this locus: p16INK4A (b) and p14ARF (c) for ALL cases from GWCMC (upper) and cases previously reported (lower) [6]. Functional domains are indicated by color based on Pfam annotation. Each circle represents a unique individual carrying the indicated variant (heterozygous or homozygous), except for variants recurring in more than two individuals for which the number in the circle indicates the exact frequency of the observed variant.

Leukemic transformation potential of inherited p16INK4A variations

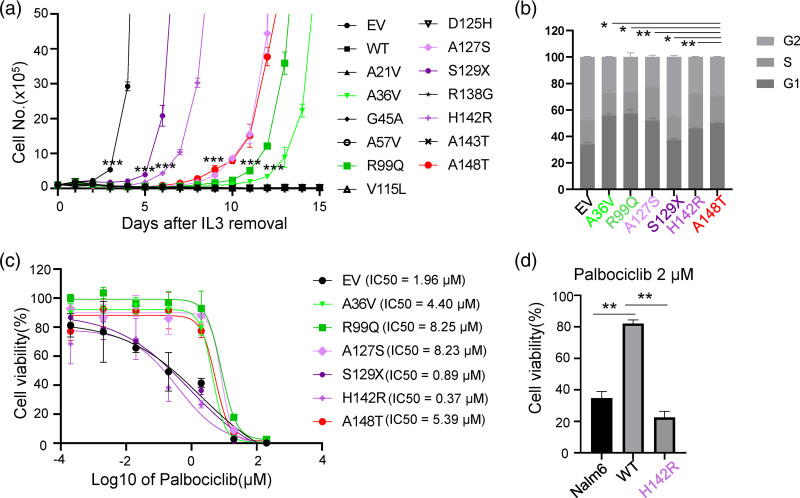

Building upon the analysis above, we next experimentally evaluated the effects of these exonic p16INK4A variations on ALL leukemogenesis. To comprehensively evaluate the effects of these variants on leukemic transformation function, we used a mouse pro-B cell, Ba/F3 cells as our study model due to its inherently defective p16Ink4a, which significantly enhances the development of ALL induced by Bcr-Abl1 oncogenic fusion. Thus, we compared the effect of wildtype versus p16INK4A variants (p.A21V, p.A36V, p.G45A, p.A57V, p.R99Q, p.V115L, p.D125H, p.A127S, p.S129X, p.R138G, p.H142R, p.A143T, and p.A148T) on BCR–ABL1-induced leukemic transformation in vitro (Supplementary Figure 2, Supplemental digital content 2, http://links.lww.com/FPC/B408). As shown in Fig. 3a, ectopic expression of wild-type p16INK4A significantly suppressed leukemic transformation induced by BCR-ABL1, while p.A148T significantly accelerated the leukemic transformation, consistent with the previous report [6]. Except for p.A148T variant, another four p16INK4A missense variants (the leukemic transformation potential: p.H142R < p.A148T = p.A127S < p.R99Q < p.A36V) were capable of potentiating Ba/F3 cells IL3-independent growth by BCR-ABL1, suggesting that the likely reduced tumor suppressor function (Fig. 3a). The p16INK4A p.S129X resulted in a premature truncation and almost completely disrupted the function of the gene (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Functional characterization of p16INK4A coding variants. (a) Cytokine-independent growth of Ba/F3 cells co-expressing wildtype, variant p16INK4A, or empty vector and leukemia oncogenic BCR–ABL1 fusion gene. Cell proliferation in the absence of cytokine IL3 was measured daily as an indicator of leukemic transformation. T-test was used to compare the cell numbers of the indicated cells with Ba/F3 cells expressing wildtype p16INK4A. (b) Cell cycle analysis of transformed Ba/f3 cells, expressing indicated variant p16INK4A or empty vector. Ba/F3 cells were fixed with 66% Ethanol and then stained with propidium iodine and RNase, followed by Flow cytometric and Flowjo analysis. (c) Cytotoxicity of Palbociclib towards Ba/F3 cells. Ba/F3 cells expressing the indicated vectors were treated with increasing concentrations of Palbociclib for 48 h before assessing viability using a CCK8 assay. (d) Cytotoxicity of Palbociclib towards Nalm6 cells. Nalm6 cells expressing empty vector, p16INK4A, or p16INK4A p.H142R, were treated with 2 μM Palbociclib for 72 h and then analyzed by CCK8 assay. All experiments were repeated twice in triplicate, and data represent the mean of three replicates ± SEM. Asterisks represent statistical significance (*P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001). WT, wild type; EV, empty vector.

The p16INK4A is a critical cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor and cell cycle entry regulator. To test the impact of these functional p16INK4A variants, we applied propidium iodide staining to evaluate the cell cycle distribution of BCR-ABL1-transformed Ba/F3 cells with different p16INK4A variants expression. Though we could not compare our results with the wild type p16INK4A due to its incapability of leukemic transformation, we observed an increase of S phase (25.9% ± 5.2%) in Ba/F3 cells with the p.H142R variant p16INK4A as compared to 20.0% ± 4.9% S phase in Ba/F3 cells with p.A148T variant (P = 0.006), in consistent with the great transforming potential of p.H142R over p.A148T. The S phase percentage in Ba/F3 cells with p16INK4A p.A127S was also higher than that in Ba/F3 cells with p16INK4A p.A148T (P = 0.002). In the meanwhile, the S phase percentage in Ba/F3 cells ectopically overexpressed p16INK4A p.R99Q and p16INK4A p.A36V was lower than p16INK4A p.A148T (Fig. 3b), which was in line with their leukemic transformation potentials.

CDK4/6 inhibitors, which block the transition from the G1 to S phase of the cell cycle by interfering with Rb phosphorylation and E2F release, have shown potent antitumor activity and manageable toxicity in ALL patients in vitro [19–21]. Interestingly, a few clinical trials involving CDK4/6 inhibitors in relapsed/refractory ALL have been in progress (Supplementary Table 2, Supplemental digital content 1, http://links.lww.com/FPC/B407). The findings above prompted us to ask whether BCR-ABL1-induced leukemic Ba/F3 cells with p16INK4A variants responded to CDK4/6 inhibitors. To test the cytotoxic effects of CDK4/6 inhibition, BCR-ABL1-transformed Ba/F3 cells were treated with increased concentrations of palbociclib. As shown in Fig. 3c, BCR-ABL1-transformed Ba/F3 cells underwent apoptosis upon Palbociclib treatment in a dose-dependent fashion. As compared to Ba/F3 cells with p16INK4A p.A148T, co-transduction of p16INK4A p.H142R significantly potentiated response to palbociclib, in consistence with the leukemic transformation and cell cycle distribution results. Similar effects were also observed in another two CDK4/6 inhibitors, abemaciclib and ribociclib (Supplementary Figure 3, Supplemental digital content 2, http://links.lww.com/FPC/B408). To further confirm p16INK4A mutation in human B-ALL cells, we established Nalm6 cells ectopically overexpressing p16INK4A variants by lentiviral transfection and tested the effect of mutations on the response to CDK4/6 inhibitors. In accordance with the results for Ba/F3 cells, p16INK4A p.H142R were more sensitive than p16INK4A wild-type (Fig. 3d). Taken together, these results point to the exonic p16INK4A variants may potentiate ALL development and drug response to CDK4/6 inhibitors due to reduced tumor suppressor function.

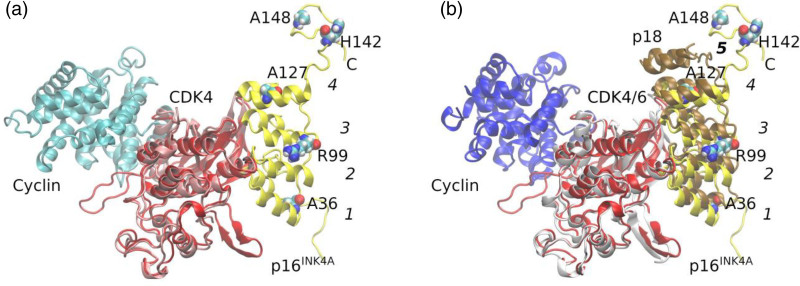

Structural basis of dysfunction of inherited p16INK4A variants

To address the impact of the variant protein, we performed immunoblotting assays to test the effects of p16INK4A variants on CDK4/6-RB-E2F2 signaling pathway. Unexpectedly, we could not identify too many effects of the p.H142R and p.A148T variants on this signaling pathway as evidenced by unaltered phosphorylation level of CDK4 and Rb protein. (Supplementary Figure 4, Supplemental digital content 2, http://links.lww.com/FPC/B408). p16INK4A is the prototype of a family of CDK inhibitors, specific for CDK4/6. Most observations suggest that p16INK4A binds next to the ATP-binding site of CDK4/6, opposite where the activating cyclin subunit binds [22–24]. p16INK4A prevents cyclin binding indirectly by causing structural changes that propagate to the cyclin-binding site [24]. p16INK4A consists of four ankyrin repeats, consisting of ~30 amino acids. These ankyrin repeats stack to give an extended concave surface, binding to the N lobe of CKD4/6 [24]. Tumor-derived missense mutations in p16INK4A affect its structural integrity, as has been demonstrated by studies of its stability and aggregation state [25,26]. To elucidate the structural basis of the effects of the inherited p16INK4A variants, structures were generated by homology modeling methods. p.A36V, p.R99Q, and p.A127S, which locate at ANK_1, ANK_3, and ANK_4, respectively, affect the binding of p16INK4A with CDK4 (Fig. 4). To this end, we could not reveal the causes of p.H142R and p.H148T with this model, since both variants are located to the C terminal, suggesting that some other hidden mechanisms existed.

Fig. 4.

The p16INK4A/CDK4 complex model and the superimposition with the crystal structure of CDK4/CyclinD. (a) p16INK4A and CDK4 from homology modeling were shown in yellow and red, respectively. Cyclin D in cyan and CDK4 in pink was from the crystal structure (PDB ID: 6P8G). The two complexes were superimposed according to the CDK4 proteins. Ankyrin domains in p16INK4A were numbered from 1 to 4 with starting from N terminus. p16INK4A variants, resulting in leukemic transformation were shown as Van der Waals spheres. p.A36V, p.R99Q, and p.A127S, are in ANK_1, ANK_3, and ANK_4 domains, respectively, and p.H142R and p.A148T in C-terminus of p16INK4A. (b) p16INK4A and CDK4 from homology modeling were shown in yellow and red, respectively. p18 in brown, CDK6 in gray, and Cyclin in blue were from crystal structure (PDB ID: 1G3N). The two complexes were superimposed according to the alignment of CDK4 and CDK6 proteins. Ankyrin domains in p18 were numbered from 1 to 5 with starting from N terminus. p.H142R and p.A148T are in C-terminus of p16INK4A, which equivalent to the Ank_5 domain of p18.

Discussion

CDKN2A/2B is a well-established tumor suppressor gene, encoding p16INK4A, p15INK5B, and p14ARF. Loss of CDKN2A/2B function caused by genomic deletion, hypermethylation, and mutations are multi-dimensionally associated with cancer development, for example, cancer susceptibility carcinogenesis, prognosis, and treatment response [27–29]. In regard to cancer susceptibility, inherited CDKN2A/2B variants confer susceptibility not only to ALL, but also to glioma, basal cell carcinoma, and melanoma [30–33]. Though over 90% of diseases/traits-associated CDKN2A/2B variants are located in noncoding (intronic and/or intergenic) regions, a few studies have revealed that CDKN2A exonic variants also confer susceptibility to childhood ALL [5,6,34]. In this study, we report that the genomic region of CDKN2A/2B is responsible for cancer susceptibility, and systemically examine the role of inherited CDKN2A exonic variants in ALL development and their potentials.

Zhang et al. have identified a repressive element proximal to the ARF promoter, which is responsible for mediating p16INK4A expression, suggesting that certain crucial genomic regions for CDKN2A/2B transcription [35]. To better decipher the pattern of diseases/traits-associated CDKN2A/2B SNPs, we utilized online tools to assess whether specific genomic regions affect different diseases/traits and found that the genomic region (chr9: 22090000-22140000) in CDKN2A/2B loci might be responsible for cancer susceptibility, while the distal region was more enriched for noncancer diseases/traits (e.g. coronary heart disease, diabetes, myocardial infarction, etc.) (Fig. 1), suggesting a distinct functional role of CDKN2A/2B loci. It is perhaps that there is variability in the long-distance chromatin interactions and co-regulatory elements among these two genomic regions.

The p16INK4A is a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor and regulates cell cycle entry via the Rb-E2F signaling [36]. p16INK4A is suppressed during normal hematopoiesis, while it is activated by different oncogenic stimuli, for example, BCR-ABL1 fusion and PDGFRB-fusion [37–39]. Once activation, the impact of p16INK4A on CDK4/6 would lead to cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase (senescence) in order to eliminate oncogene-stressed cells. Bi- or monoallelic CDKN2A/2B deletions were found in 64% of BCR–ABL1 positive ALL cases and in 32–72% of ALL cases without the BCR-ABL1 translocation [37]. All these points to the role of defective p16INK4A, p14ARF, and p15INK4B in leukemogenesis. Through CDKN2A/2B targeted sequencing, Xu et al. has identified that the inherited p16INK4A p.A148T variant (rs3731249) is also strongly associated with ALL [6]. Functional assays have demonstrated that the p16INK4A p.A148T variant is preferentially retained in B-ALL leukemic cells compared to its wild-type [5,6,34], suggesting the role of exonic SNPs in B-ALL risk. Except for rs3731249 (p16INK4A p.A148T), we here systemically examined the impact of other p16INK4A variants on ALL leukemogenesis and identified another five variants (p.A36V, p.R99Q, p.A127S, p.S129X, and p.H142R) with leukemogenic potential (Fig. 3a). All these five variants could induce cell cycle entry from G1 to S phase, with most prominently in p.H142R variant. Leukemic transformed Ba/F3 cells with p.H142R were well responded to CDK4/6 inhibitors (palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib) (Fig. 3c, and Supplementary Figure 3, Supplemental digital content 2, http://links.lww.com/FPC/B408), suggesting clinical translation potentials. Meanwhile, these data also indicated that patients with these variants may be susceptible to experience CDK4/6 inhibitor adverse drug reactions. The structural analysis revealed that p.A36V, p.R99Q, and p.A127S in ANK domains weakened the binding of p16INK4A with CDK4, but could not explain the effect of p.H142R and p.A148T, since both of these two variants located in the C-terminus, which is not involved in the interaction (Fig. 4).

Conclusion

The systemic analysis of diseases/traits-associated CDKN2A/2B SNPs revealed distinctive genomic hotspots responsible for cancers or noncancer diseases. In the meanwhile, we systemically evaluated the impacts of inherited p16INK4A exonic variants and identified four missense (p.A36V, p.R99Q, p.A127S, and p.H142R) and one nonsense (p.S129X) variants conferring ALL susceptibility. Among these five variants, p16INK4A p.H142R demonstrated the greatest potential of ALL leukemogenesis and CDK4/6 inhibitor clinical translation. Our findings pinpoint the function of CDKN2A/2B loci in ALL leukemogenesis and targeted therapy.

Materials and methods

Patients

The patients were prospectively enrolled in the CCCG-2015-ALL clinical trial, which was approved by the institutional review board of the Guangzhou Women and Children Medical Center (GWCMC) (2018022205). Details of the enrollment criteria and study design have been described previously [40]. All the investigated pediatric ALL patients were treated in the GWCMC. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the GWCMC (IRB No.2018022205, 2017102307, 2015020936, and 2019-04700), registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR-IPR-14005706), and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from the patients or their legal guardians.

Cell culture

HEK293T cells (ATCC, Rockefeller, Maryland, USA) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and penicillin/streptomycin. Ba/F3 cells (gift from Dr Omar Abdel-Wahab at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, USA) were maintained in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 ng/mL IL3, and penicillin/streptomycin. Nalm6 cells (ATCC) were maintained in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, and penicillin/streptomycin.

Virus transduction

BCR-ABL1 p185 cDNA was amplified from MSCV–BCR–ABL1–Luc2 construct, a gift from Dr. Charles Sherr at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital, and cloned into Lenti-MCS-Blast lentiviral empty vector [41]. Full-length p16INK4A was amplified and cloned into the cL20c-IRES-GFP lentiviral vector, and mutations were generated using the Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, Massachusetts, USA). Lentiviral supernatants were produced by transient transfection of HEK-293T cells using calcium phosphate. For transduction, Ba/F3 cells were co-transduced with lentiviral supernatants expressing BCR-ABL1 and p16INK4A, followed by Blasticidin selection and fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

Cytokine-independent growth assay in Ba/F3 cells

Cells were expanded after being washed three times and then plated at a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL in non–IL3-containing medium. Viable cell counts were obtained using Trypan blue staining on TC20 Automated Cell Counter (Bio-Rad, Shanghai, China).

Cytotoxicity assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 25 000 cells per 100 μL per well with either vehicle or increasing concentrations (0.0002, 0.002, 0.02, 0.2, 2, 20, and 200 µM) of drugs for 48–72 h. Cell viability was assessed by adding CCK8 (Cell Counting Kit-8, Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Procedures to determine the effects of certain conditions on cell proliferation were performed in three independent experiments.

CDKN2A genotyping

Germline genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples obtained during clinical remission for children with ALL. CDKN2A exons were genotyped in the samples by Sanger Sequencing using primers listed in Supplementary Table 4, Supplemental digital content 1, http://links.lww.com/FPC/B407.

Western blotting

Preparation of cellular protein lysates was performed by using the Cell signaling Lysis buffer (9803; Cell Signaling Technology, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s extraction protocol. Protein quantitation was done using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Shanghai, China). A total of 30 μg of protein was denatured in Leammli buffer at 95°C for 5 min and western immunoblotting was performed using the Bio-Rad system 4–15% Precast Progein Gels. The transfer was performed using the Trans-Blot turbo system (Bio-Rad) onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The immunoblotting was performed with the primary antibody and secondary anti-rabbit antibodies mentioned in Supplementary Table 5, Supplemental digital content 1, http://links.lww.com/FPC/B407. Images were acquired by using the Bio-Rad imaging chemidoc MP system. ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA) was used to performed densitometry analyses of western blots. Results of each band were normalized to the beta-actin/Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase levels in the same blot.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were harvested and fixed in 70% ethanol for 30 min at 4°C and washed with phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 1% FBS. The cells were treated with 100 µg/mL RNase A (Sigma Aldrich, Shanghai, China) for 1 h at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator and stained using 50 µg/mL propidium iodide (Sigma Aldrich) for 30 min at room temperature. The DNA content of the cells was analyzed using FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA) and FlowJo v. 10 software (FlowJo, Ashland, Oregon, USA).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism and/or R (version 3.2.5, https://www.R-project.org); all tests were two-sided. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant, P < 0.05, *; P < 0.01, **, P < 0.001, ***, and P < 0.0001, ****. Regional association plots were created by Locus zoom (http://locuszoom.org/) [18].

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research grants from St. Baldrick’s Foundation International Scholar (581580), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2015A030313460), and Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center Internal Program (IP-2018-001, 5001-1600006, and 5001-1600008). M.Q. is supported by the Program for Professor of Special Appointment (Eastern Scholar) at Shanghai Institutions of Higher Learning and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81973997). C.L. is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32000392). The authors thank the patients in this study, and they kindly give us a chance to work on this interesting research. We would also like to thank Xujie Zhao for English language editing.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.pharmacogeneticsandgenomics.com.

References

- 1.Hunger SP, Mullighan CG. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1541–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terwilliger T, Abdul-Hay M. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a comprehensive review and 2017 update. Blood Cancer J 2017; 7:e577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloom M, Maciaszek JL, Clark ME, Pui CH, Nichols KE. Recent advances in genetic predisposition to pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Expert Rev Hematol 2020; 13:55–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moriyama T, Relling MV, Yang JJ. Inherited genetic variation in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2015; 125:3988–3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vijayakrishnan J, Kumar R, Henrion MY, Moorman AV, Rachakonda PS, Hosen I, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies risk loci for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia at 10q26.13 and 12q23.1. Leukemia 2017; 31:573–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu H, Zhang H, Yang W, Yadav R, Morrison AC, Qian M, et al. Inherited coding variants at the CDKN2A locus influence susceptibility to acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children. Nat Commun 2015; 6:7553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertin R, Acquaviva C, Mirebeau D, Guidal-Giroux C, Vilmer E, Cavé H. CDKN2A, CDKN2B, and MTAP gene dosage permits precise characterization of mono- and bi-allelic 9p21 deletions in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2003; 37:44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iacobucci I, Ferrari A, Lonetti A, Papayannidis C, Paoloni F, Trino S, et al. CDKN2A/B alterations impair prognosis in adult BCR-ABL1-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17:7413–7423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kettunen E, Savukoski S, Salmenkivi K, Böhling T, Vanhala E, Kuosma E, et al. CDKN2A copy number and p16 expression in malignant pleural mesothelioma in relation to asbestos exposure. BMC Cancer 2019; 19:507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Oosterwijk JG, Li C, Yang X, Opferman JT, Sherr CJ. Small mitochondrial Arf (smArf) protein corrects p53-independent developmental defects of Arf tumor suppressor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017; 114:7420–7425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayward NK, Wilmott JS, Waddell N, Johansson PA, Field MA, Nones K, et al. Whole-genome landscapes of major melanoma subtypes. Nature 2017; 545:175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monzon J, Liu L, Brill H, Goldstein AM, Tucker MA, From L, et al. CDKN2A mutations in multiple primary melanomas. N Engl J Med 1998; 338:879–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kathiravan M, Singh M, Bhatia P, Trehan A, Varma N, Sachdeva MS, et al. Deletion of CDKN2A/B is associated with inferior relapse free survival in pediatric B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2019; 60:433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherborne AL, Hosking FJ, Prasad RB, Kumar R, Koehler R, Vijayakrishnan J, et al. Variation in CDKN2A at 9p21.3 influences childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia risk. Nat Genet 2010; 42:492–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu H, Yang W, Perez-Andreu V, Devidas M, Fan Y, Cheng C, et al. Novel susceptibility variants at 10p12.31-12.2 for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in ethnically diverse populations. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013; 105:733–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hungate EA, Vora SR, Gamazon ER, Moriyama T, Best T, Hulur I, et al. A variant at 9p21.3 functionally implicates CDKN2B in paediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia aetiology. Nat Commun 2016; 7:10635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buniello A, MacArthur JAL, Cerezo M, Harris LW, Hayhurst J, Malangone C, et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Res 2019; 47:D1005–D1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, Teslovich TM, Chines PS, Gliedt TP, et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics 2010; 26:2336–2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pikman Y, Alexe G, Roti G, Conway AS, Furman A, Lee ES, et al. Synergistic drug combinations with a CDK4/6 inhibitor in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23:1012–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park JH, Park H, Kim KH, Kim JS, Choi IS, Roh EY, et al. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a patient treated with letrozole and palbociclib. J Breast Cancer 2020; 23:100–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bortolozzi R, Mattiuzzo E, Trentin L, Accordi B, Basso G, Viola G. Ribociclib, a Cdk4/Cdk6 kinase inhibitor, enhances glucocorticoid sensitivity in B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-All). Biochem Pharmacol 2018; 153:230–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guiley KZ, Stevenson JW, Lou K, Barkovich KJ, Kumarasamy V, Wijeratne TU, et al. p27 allosterically activates cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and antagonizes palbociclib inhibition. Science 2019; 366:eaaw2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russo AA, Tong L, Lee JO, Jeffrey PD, Pavletich NP. Pavletich. Structural basis for inhibition of the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk6 by the tumour suppressor p16INKa. Nature 1998; 395:237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Day PJ, Cleasby A, Tickle IJ, O’Reilly M, Coyle JE, Holding FP, et al. Crystal structure of human CDK4 in complex with a D-type cyclin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106:4166–4170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams RT, Barnhill LM, Kuo HH, Lin WD, Batova A, Yu AL, Diccianni MB. Chimeras of p14ARF and p16: functional hybrids with the ability to arrest growth. PLoS One 2014; 9:e88219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen YW, Chu HC, Lin Z-S, Shiah WJ, Chou CP, Klimstra DS, Lewis BC. p16 Stimulates CDC42-dependent migration of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. PLoS One 2013; 8:e69389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gutierrez-Camino A, Martin-Guerrero I, Garcia de Andoin N, Sastre A, Carbone Bañeres A, Astigarraga I, et al. Confirmation of involvement of new variants at CDKN2A/B in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia susceptibility in the Spanish population. PLoS One 2017; 12:e0177421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuster K, Venkateswaran N, Rabellino A, Girard L, Peña-Llopis S, Scaglioni PP. Nullifying the CDKN2AB locus promotes mutant K-ras lung tumorigenesis. Mol Cancer Res 2014; 12:912–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sievers P, Hielscher T, Schrimpf D, Stichel D, Reuss DE, Berghoff AS, et al. CDKN2A/B homozygous deletion is associated with early recurrence in meningiomas. Acta Neuropathol 2020; 140:409–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan AK, Han SJ, Choy W, Beleford D, Aghi MK, Berger MS, et al. Familial melanoma-astrocytoma syndrome: synchronous diffuse astrocytoma and pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma in a patient with germline CDKN2A/B deletion and a significant family history. Clin Neuropathol 2017; 36:213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qi X, Wan Y, Zhan Q, Yang S, Wang Y, Cai X. Effect of CDKN2A/B rs4977756 polymorphism on glioma risk: a meta-analysis of 16 studies including 24077 participants. Mamm Genome 2016; 27:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reinhardt A, Stichel D, Schrimpf D, Sahm F, Korshunov A, Reuss DE, et al. Anaplastic astrocytoma with piloid features, a novel molecular class of IDH wildtype glioma with recurrent MAPK pathway, CDKN2A/B and ATRX alterations. Acta Neuropathol 2018; 136:273–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eshkoor SA, Ismail P, Rahman SA, Oshkour SA. p16 gene expression in basal cell carcinoma. Arch Med Res 2008; 39:668–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walsh KM, de Smith AJ, Hansen HM, Smirnov IV, Gonseth S, Endicott AA, et al. A Heritable missense polymorphism in CDKN2A confers strong risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and is preferentially selected during clonal evolution. Cancer Res 2015; 75:4884–4894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y, Hyle J, Wright S, Shao Y, Zhao X, Zhang H, et al. A cis-element within the ARF locus mediates repression of p16INK4A expression via long-range chromatin interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019; 116:26644–26652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krug U, Ganser A, Koeffler HP. Tumor suppressor genes in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Oncogene 2002; 21:3475–3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams RT, Sherr CJ. The INK4-ARF (CDKN2A/B) locus in hematopoiesis and BCR-ABL-induced leukemias. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 2008; 73:461–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu JY, Souroullas GP, Diekman BO, Krishnamurthy J, Hall BM, Sorrentino JA, et al. Cells exhibiting strong p16 INK4a promoter activation in vivo display features of senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019; 116:2603–2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chien WW, Catallo R, Chebel A, Baranger L, Thomas X, Béné MC, et al. The p16(INK4A)/pRb pathway and telomerase activity define a subgroup of Ph+ adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia associated with inferior outcome. Leuk Res 2015; 39:453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen S, Chen X, Cai J, Yu J, Gao J, Hu S, et al. Effect of dasatinib vs imatinib in the treatment of pediatric Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2020; 6:358–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams RT, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. Arf gene loss enhances oncogenicity and limits imatinib response in mouse models of Bcr-Abl-induced acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103:6688–6693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.