Abstract

Advanced technologies for controlled delivery of light to targeted locations in biological tissues are essential to neuroscience research that applies optogenetics in animal models. Fully implantable, miniaturized devices with wireless control and power harvesting strategies offer an appealing set of attributes in this context, particularly for studies that are incompatible with conventional fiberoptic approaches or battery-powered head stages. Limited programmable control and narrow options in illumination profiles constrain the use of existing devices. The results reported here overcome these drawbacks via two platforms, both with real-time user programmability over multiple independent light sources in head mounted and back mounted designs. Engineering studies of the optoelectronic and thermal properties of these systems define their capabilities and key design considerations. Neuroscience applications demonstrate that induction of interbrain neuronal synchrony in medial prefrontal cortex shapes social interaction within groups of mice, highlighting the power of real-time subject-specific programmability of the wireless optogenetics platforms introduced here.

Introduction

Understanding the functional organization of the central nervous system is a major goal in modern neuroscience research 1. In vivo optogenetics facilitates this goal by modulating neuronal activity using light stimulation of genetically targeted excitatory or inhibitory opsins 2,3,4. However, the most common approach—using optical fibers to deliver light from external sources 5,6—results in steric constraints that can interfere with animals’ natural movements and impede the investigation of neural circuits underlying complex behaviors 7,8,9. Recently developed, battery-free wireless devices that incorporate microscale light emitting diodes (μ-ILEDs) and radiofrequency (RF) strategies for wireless power delivery enable fully implantable, tether-free optogenetics studies 7,8,10,11. The most advanced system variants provide control over optical intensity, pulse duration, and stimulation frequency, with some level of multimodal operation 10; yet, they rely on passive modulation of the RF source or deterministic pre-loaded programs in microcontrollers. These control mechanisms limit real-time modification of stimulation protocols during the course of an experiment. Moreover, the geometrical designs of current wireless platforms allow for only single or dual-probe placement with fixed spacing 8,9,10, restricting flexible targeting in the brain and periphery. Finally, while subdermal mounting on the head of the animal is straightforward, the location imposes severe constraints on the area available for circuit components and receiver antennas.

These collective limitations are significant for many experimental protocols, including those that require control capabilities for independent modulation of neuronal activity patterns across regions 12,13,14,15 and/or real-time programmability of light delivery to interrogate the causal relationships between neuronal activity and behavioral phenotypes 16,17,18,19. Also, independent wireless control over multiple individual animals within the same physical space could create unique opportunities to investigate social behavior 20,21. The overall capabilities of the technology introduced here address these requirements, with potential for low cost production using advanced manufacturing processes, adapted from the flexible printed circuit board industry, suggesting a strong potential for widespread adoption across the neuroscience community.

Head Mounted and Back Mounted Multilateral Optogenetic Devices

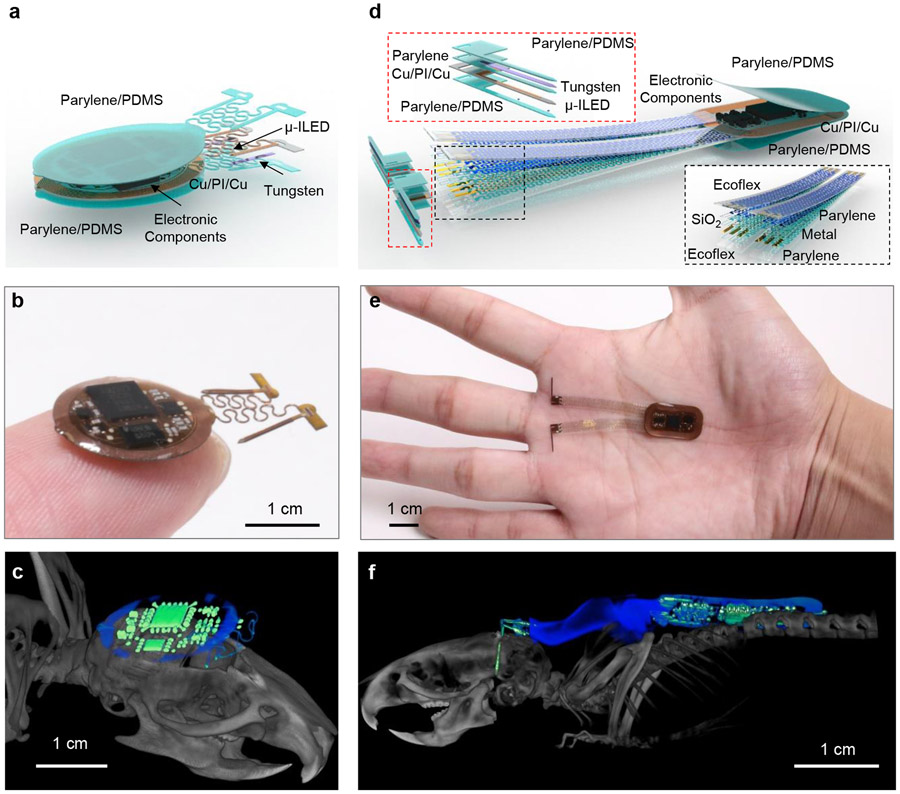

The devices described here include both head mounted (HM) and back mounted (BM) designs (Fig. 1, Extended Data Fig. 1a). The devices are wirelessly powered using magnetic inductive coupling provided by a primary dual-loop RF transmission antenna driven at 13.56 MHz and wrapped around the experimental enclosure (~ 30 x 30 cm2). The user interface controls the near field communication (NFC) protocol that allows independent wireless communication to each device through the same transmission antenna in real-time. Figure 1a shows an expanded schematic illustration of the HM device (10 x 12 mm2, ~1.2 mm thick). The small size allows implantation directly over the top of the skull, underneath the skin, in animal models as small as mice. The device contains laser ablated receiver antenna with soldered electronic components to provide power and active control. μ-ILEDs affixed at the tip ends of the penetrating probes provide localized illumination for stimulation or inhibition. Bilateral probes connected to the electronics platform via independent serpentine traces provide large degrees of freedom in positioning during the surgical processes. Parylene (~14 μm)/polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS; ~ 30 μm at probes and serpentine traces, and ~ 200–800 μm elsewhere) bilayer encapsulates the device and provide soft contact with surrounding tissues. The advanced HM device platform (Fig.1b) incorporates an analog filter, an NFC system-on-a-chip (SoC), and a micro-controller for dynamically programmable operation (Extended Data Fig. 1b) of two independent channels. Simplified versions of these devices (Supplementary Fig. S1) selectively support voltage regulation (Extended Data Fig. 1c) for experiments that only require synchronized bilateral stimulation at fixed intensity. Details of the implantation procedures are in Supplementary Fig. S2 and Fig. S3.

Figure 1: Device layout and implantation.

a, Layered schematic illustration of a head mounted, subdermal device (HM) for optogenetic research in untethered animals with dynamically programmable operation. b, Photograph of this HM device. c, CT image of a HM device in a mouse model (b). d, Layered schematic illustration of similar device with a back mounted, subdermal (BM) design. e, Photograph of this BM device. f, CT image of a BM device in a mouse model (e).

The lateral dimensions of HM devices cannot exceed the top surface of the skull of the animal (~ 100 mm2 for mice), restricting advanced embodiments with larger sizes and power requirements. A solution that largely circumvents these considerations utilizes the broad space on the back of the animal. Here, BM subdermal implants can include relatively large receiver coils (11 x 19 mm2) and complex electronics encapsulated in parylene/PDMS bilayer, similar to that used in the HM devices. The penetrating probes connect to the electronic platform through thin (~390 nm) serpentine metallic traces encapsulated in soft elastomers (~200 μm) to yield mechanics compatible with the implantation procedures and natural motions of the animal, without adverse effects (Fig. 1d). An example device illustrating this design offers dynamically programmable operation (Extended Data Fig. 1b) with four independent μ-ILEDs (Fig. 1e). The layouts can be further extended to μ-ILED arrays that integrate injectable probes or compliant substrates at additional interface locations, including peripheral nerves, heart, spinal cord, and others. Detailed surgical procedures for mice and rats appear in supplementary Fig. S4 and Fig. S5. Microscale computed tomography (CT) images of mice with the HM or BM implants are in Fig. 1c and Fig.1f. Studies indicate chronic stability in operation for >9 weeks, the longest tested period. Additional information on the device fabrication is in supplementary Fig. S6-S8 and the Methods section.

Mechanical Characterization for Multilateral Optogenetic Devices

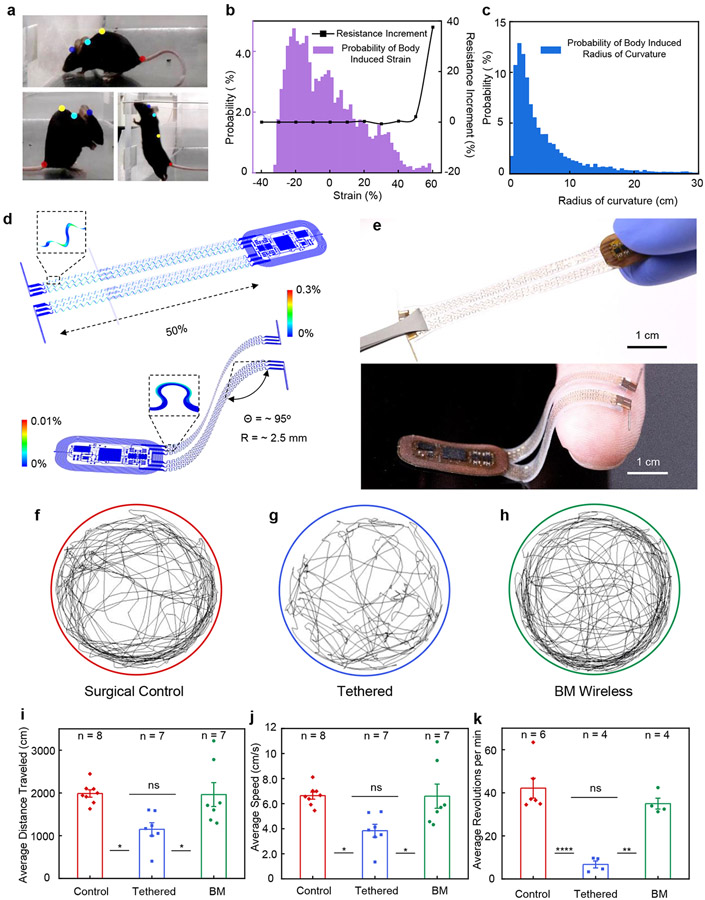

The electrical connections between the electronics and the probes for BM devices must support a wide range of continuous motion across the back and neck regions during natural movement. Video graphic analyses using DeepLabCut 22 yield quantitative estimates of the range of deformations associated with natural mouse motion at the head, neck, back, and tail regions (Fig. 2a and methods), thereby defining compliance requirements in the interconnect structures. Specifically, changes in distance from head-to-neck and neck-to-back determine the magnitudes of compression and elongation. Variations in the circumradius of the head-neck-back triangle determine the levels of bending. The probability distribution in Fig. 2b shows ranges of ~30% for compression and ~60% for elongation. Figure 2c highlights the corresponding probability distribution for bending ranging from ~1 cm to ~30 cm.

Figure 2: Characterization of mechanical properties and effects on animal locomotor behavior.

a, Photograph of the curvature of the body of a mouse and changes in this curvature during natural movements. The colored dots mark points on the head, neck, back, and tail of the mouse for characterizing these changes as the mouse moves in an enclosure. b, Probability distribution of tensile strains (i.e. compressing and stretching) associated with routine activities, and benchtop tests of changes in resistance of the stretchable interconnects used for the BM device platform after 10,000 cycles of stretching/compressing (black line) at 1 Hz. c, Corresponding probability distribution of bending deformations (i.e. radius of curvature), d, FEA simulations of a stretched and bent BM device. e, Photographs of a stretched and bent device. f-h, Results of motion tracking (5 min in a circular arena) of freely moving mice (surgical control), mice implanted with bilateral optical fibers (tethered), and mice implanted with BM devices (BM wireless). i, Average distance traveled over 5 minutes in the circular arena (ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparisons test; Control vs. Tethered, P = 0.01; Tethered vs. BM Wireless, P = 0.02; Control vs. BM Wireless, P = 0.99). j, Average movement speed over 5 minutes in the circular arena (ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparisons test; Control vs. Tethered, P = 0.02; Tethered vs. BM Wireless, P = 0.02; Control vs. BM Wireless, P = 0.99). k, Average revolutions per minute when running on a wheel over a 60 minute period (ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparisons test; Control vs. Tethered, P < 0.0001; Tethered vs. BM Wireless, P = 0.0014; Control vs. BM Wireless, P = 0.40). All data are represented as mean +/− SEM. * P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001, ns: not significant.

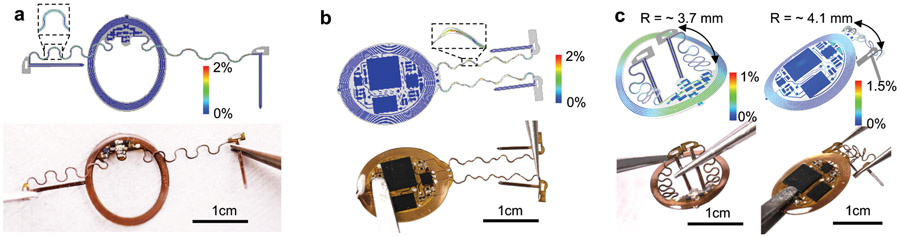

The designs of the interconnects of the BM devices support repetitive deformations across these ranges. Finite element analysis (FEA) and experimental results showed that the constituent materials of the interconnects remain in an elastic response regime for uniaxial stretching of up to 50% and for 95° bending at a radius of curvature of 2.5 mm (Fig. 2d-e). The equivalent strains in the metals remain less than their yield strains (~0.3%) 23, as were the strains in the polymers. Systematic experimental studies using cyclic tests (10,000 cycles, 1 Hz) at different stretching levels define transition threshold from elastic to plastic deformation. In the elastic region, the electrical resistance of the interconnects remained nearly unchanged. Plastic deformations lead to notable increases in resistance. The results, highlighted in Fig. 2b (black line), define an elastic range that extended to a stretch of ~50% (resistance change <3%), consistent with FEA results (Fig. 2d). Unlike for the BM devices, the serpentine traces in the HM devices can be plastically deformed to target positions during implantation because they remain fixed in these positions by anchoring to the skull with dental cement (Supplementary Fig. S2-S3). Extended Data Figure 2 shows typical mechanical deformations for the HM devices during and after implantation, all of which lead to material strains that remain well below their fracture points 24.

For both classes of devices, the impact on locomotor behaviors was negligible. Natural behavior patterns of mice implanted with HM devices were similar to those of mice without implantation (Extended Data Fig. 3), consistent with previous studies 25. Figures 2f-h present representative single mouse movement tracks over a five-minute period in an open-field environment. Reductions in the average distance traveled (Fig. 2i; ANOVA; F = 6.607; P = 0.0066) and average speed during movements (Fig. 2j; ANOVA; F = 6.418; P = 0.0074) occurred for mice implanted with and tethered by optical fibers. Meanwhile, mice implanted with BM devices exhibit near identical travel distances (NS; P = 0.99) and movement speeds (NS; P = 0.99) compared to surgical controls. Additional tests examined mobility across the groups (n = 4-6) using a running wheel experiment. Mice implanted with BM devices exhibit similar average revolutions per minute as controls over a 60-minute period (NS; P = 0.40), while tethered mice ran less than control and BM groups (Fig. 2k, ANOVA; F = 23.12; P = 0.0001). Collectively, these experiments demonstrate that the BM devices do not restrict animal’s natural movement and maintain function during routine activity.

Biocompatibility Characterization for Multilateral Optogenetic Devices

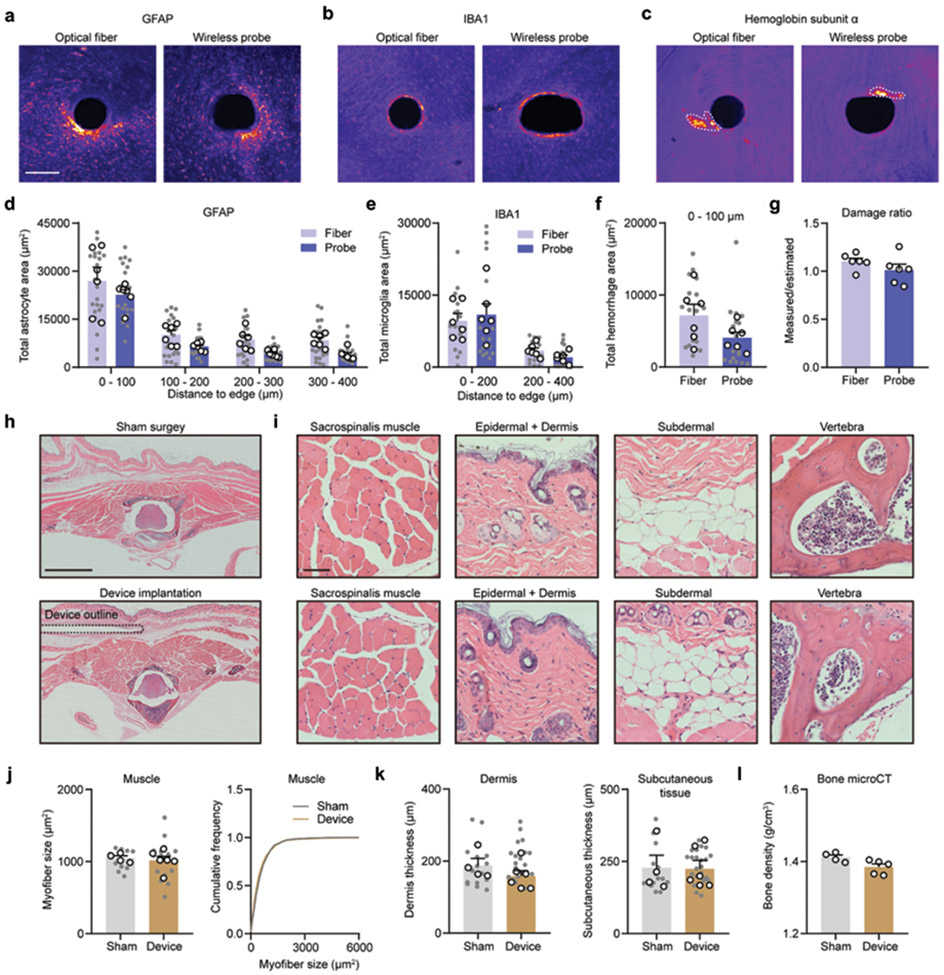

Additional experiments assessed the biocompatibility of the implantable device components, including the injectable probes with tungsten stiffeners and BM subdermal implants. Immunohistochemical markers of glial cells and hemoglobin yielded insights into implantation-associated gliosis and hemorrhage. Mice implanted with wireless probes or 200 μm diameter optical fibers showed similar astrocytic and microglial activation (Extended Data Fig. 4a-4e). No differences in hemoglobin immunoreactivity between conditions was observed (Extended Data Fig. 4f). The wireless probes did not induce significant damage to the brain tissue, as the ratio of measured damage and estimated damage is ~1 (Extended Data Fig. 4g). These data suggest that the biocompatibility of wireless probes with encapsulated tungsten is similar to optical fiber.

To determine whether BM implants induce erosion of proximal tissue or spinal impact, BM implanted and sham surgery control mice were compared 40 days after implantation (Extended Data Fig. 4h). No significant differences in morphology of surrounding muscles and skins, evidenced by H&E staining, were observed in implanted mice compared to controls (Extended Data Fig. 4i-4k). MicroCT imaging results confirmed no significant changes in bone density associated with the implants (Extended Data Fig. 4l).

Dynamically Programmable Multichannel Operation

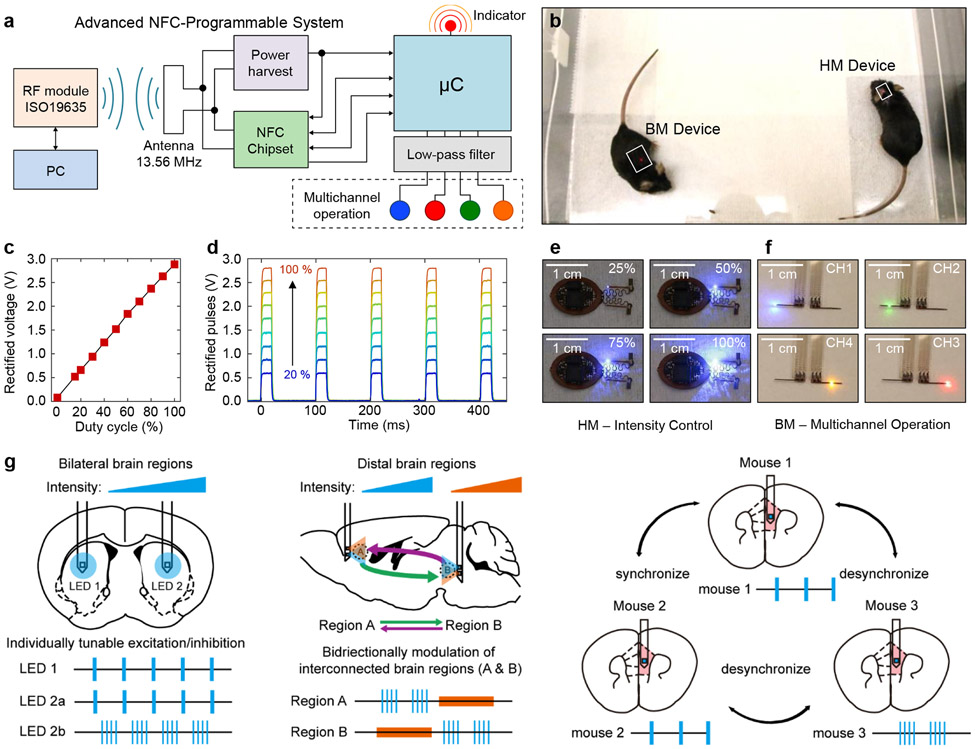

The technology introduced here supports bidirectional wireless communication, qualitatively expanding device functionality beyond that possible with previously reported technologies. The result provides full and continuous real-time wireless control over all of relevant optogenetics stimulation parameters, including intensity, frequency, and duty cycle. Additional capabilities include nearly arbitrary implementation of multichannel operation: unilateral or bilateral stimulation, and control over multiple devices within the same enclosed space. The elements that enable these capabilities include an NFC read/write random access memory (M24LR04E, ST-Microelectronics) and an 8-bit microcontroller (ATtiny84, Atmel Corp.). Extended Data Figure 1 shows the generic electronic diagram. The user addresses the microcontroller firmware using a personal computer running a customized graphical user interface (GUI) that interfaces with the RF power and communication module, supporting the ISO15693 NFC protocol (LRM2500-A, Feig Electronics). Upon a wireless command, the microcontroller reads operational parameters from the NFC memory—period, duty cycle, intensity, and mode of operation—which are then updated into the firmware to operate up to four channels independently (Fig. 3a). Figure 3b shows mice implanted with HM and BM devices inside a cage.

Figure 3: Designs, operational features, and use cases for dynamically programmable NFC electronics.

a, Block diagram of an NFC-enabled platform for independent, programmable control over operational parameters. Microcontroller firmware coupled with this electronics module allows multichannel selection and control over the period (T), duty cycle (DC) and intensity of the μ-ILEDs. b, head mounted (HM) and back mounted (BM) devices implemented with this dynamically programmable NFC electronics, operating after implantation in mice. c, Filter output voltage as a function of duty cycle of the intensity-encoding carrier waveform (Extended Data Fig. 5b). d, Time dependence of output waveforms with a period of 100 ms and duty cycle of 20% at various peak voltage magnitudes. The carrier frequency is 2 kHz, and the duty cycle varies from 20 to 100%. e, Sequence of photographs of a HM device operated at different duty cycles of the carrier waveform, to control the intensity of one of the two μ-ILEDs. f, Sequence of photographs of a BM device showing multi-channel operation. g, Schematic illustrations of several potential applications of this technology in optogenetic studies of brain processes in animal models, including tunable modulation of bilateral brain regions (left), bidirectional modulation of distal regions (middle), and multi-brain synchrony manipulation (right).

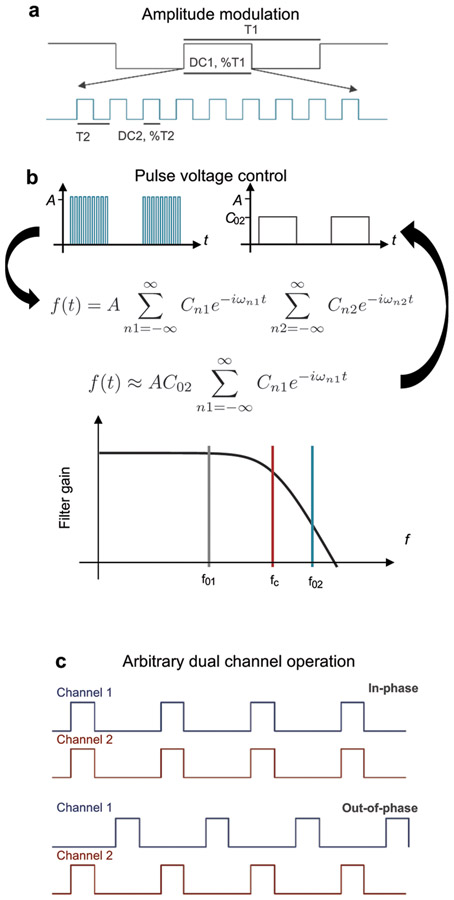

Each channel in the microcontroller supports an amplitude modulated digital signal (AM-DS) at its general purpose input/output (GPIO), which controls dynamics for optical stimulation and the optical intensity of the corresponding μ-ILED. Extended Data Figure 5a shows schematic illustrations of time traces of the AM-DS. Here, a low frequency signal (signal: period, T1; duty cycle, DC1) modulates a high frequency signal (carrier: period, T2; duty cycle, DC2). The former encodes the pulse duration and frequency of the stimulation, while the latter encodes voltage control. These parameters are extracted using a second-order passive low-pass filter that performs digital to analog conversion in the time domain. Consider an arbitrary AM-DS, as depicted in Extended Data Fig. 5a, where the time dependent amplitude A(t) can be described in a Fourier series as

where A0 is the amplitude, i is the imaginary unit, n1,2, Cn1,2 and ωn1,2 (= 2πn1fn1, 2πn2fn2) are the indices, coefficients and frequency harmonics of the signal (1) and carrier (2), respectively. The fundamental frequencies are f01 = 1/T1 and f02 = 1/T2. A low-pass filter with cut-off frequency, fc, larger than the signal (fc > f01) but smaller than the carrier (fc < f02), filters out the fundamental and higher harmonics of the carrier, while its direct current (dc) component and the low order harmonics of the signal remain, as graphically illustrated in Extended Data Fig. 5b. For a square wave, the dc component is equal to the duty cycle, C02 = DC2. Thus, the AM-DS becomes a filtered low frequency signal (with number of harmonics nf smaller than fc) whose amplitude is determined by DC2:

The microcontroller firmware, running at 1 MHz, supports signals with periods between 1 and 65000 ms and duty cycles between 1 and 100%; and carriers with periods between 0.5 and 65 ms and duty cycles between 15 and 100%. The cut-off frequency of the second order passive filter is designed to 700 Hz and the carrier frequency implemented in the AM-DS is 2 kHz. Figure 3c shows the analog voltage waveform of a filtered AM-DS, where the period and duty cycle of the signal were P1 = 100 ms (10 Hz) and DC1 = 20 %, respectively. Figure 3d and supplementary Fig. S9 show the corresponding voltage traces at different voltage levels, and the pre- and post-filtered voltage traces, respectively. These results illustrate that individual channels can be driven at different voltage levels, as observed in the intensity of the blinking μ-ILED. Figure 3e displays images of an HM device with a blue μ-ILED operating at different optical intensities (also see Movie S1). Dynamic control over frequency and pulse duration is shown in Movies S2 and S3. Figure 3f presents images of a BM device with four different μ-ILEDs individually activated wirelessly in an experimental enclosure (also see Movie S5).

This dynamic programmable NFC system offers accurate real-time wireless control over frequency (+/− 1.5% accuracy) with pulse width as short as 3 ms (Supplementary Fig. S10a). The pulse limit can be further reduced to 234 μs at the expense of removing the intensity control capability. In this manner, the low frequency component of the AM-DS involves a 1 ms temporal window that allows a single low duty cycle oscillation of the high frequency component (1 kHz), see supplementary Fig. S10b. This mode of operation also enables programable burst stimulation where the low frequency component determines the burst cycles and the high frequency component dictates the illumination dynamics.

The optogenetic device firmware allows selection across different μ-ILEDs with wide-ranging control over patterns of illumination. For example, in the HM device, four illumination configurations are possible with two independent μ-ILED channels: single channel (unilateral) or dual channel in-phase or 180° out-of-phase (bilateral), as graphically depicted in Extended Data Fig. 5c and demonstrated in Movie S4. With arbitrary pulse width and frequency selection, the out-of-phase mode operation also supports variable delay operation, i.e. controlling the bilateral stimulation time delay as described in Extended Data Fig. 5c. The increased available area for electronic components and harvesting power in the BM device enables operation of four independent μ-ILEDs. Movies S5 and Movie S6 show example unilateral and bilateral out-of-phase modes of operation. Sixteen modes of operation are possible: four unilateral, six out-of-phase and six in-phase bilateral. Another feature of this technology is device addressing capabilities. Each NFC chip is hardware encoded with a 64-bit unique identifier (UID) code that individually address a targeted device upon each command. The RF NFC reader can discover up to 256 devices simultaneously and communicate with any device with a known UID. Movie S7 and S8 shows HM and BM devices simultaneously operating, but individually controlled.

This technology expands possibilities for advanced stimulation protocols in optogenetics. Several examples are schematized in Fig. 3g. The simplest case (Supplementary Fig. S1) is synchronized excitation or inhibition of bilateral or distal brain regions. Additional possibilities (Fig. 1b) follow from regulation of neuronal activity by controlling the stimulation dynamics of μ-ILED channels independently within the same subject. Individually tunable excitation and inhibition lines provide further controls over stimulation modes, frequencies, and pulse durations, with real-time user control (Fig. 3g, left). With μ-ILEDs of different wavelengths tailored to corresponding opsins, studies of the interactions of different brain regions in a behavioral context might exploit desynchronized patterns of optogenetic excitation or inhibition. Moreover, additional power and space provided by BM devices (Fig. 1e) allow for bidirectional modulation of interconnected brain regions, where independent, dynamic control over at least four μ-ILEDs is important (Fig. 3g, middle). Finally, the capacity for real-time reprogramming and independent control over multiple devices enables the studies of behaviors that involve multiple animals, each with individualized stimulation parameters (Fig. 3g right). Additional options follow from full use of the GPIO of the microcontroller for operation of up to eight channels. See Supplementary Fig. S11 and Methods for hardware implementation and customized software operation of control system for behavior experiments.

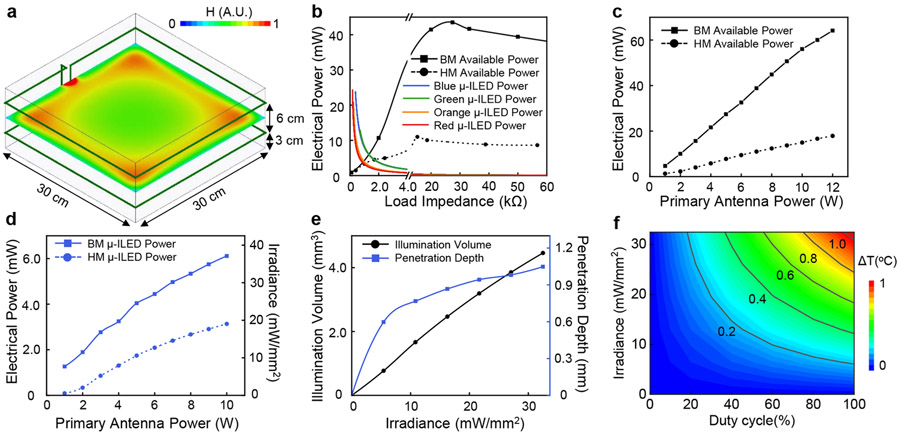

Optical and Thermal Characterization of the μ-ILEDs

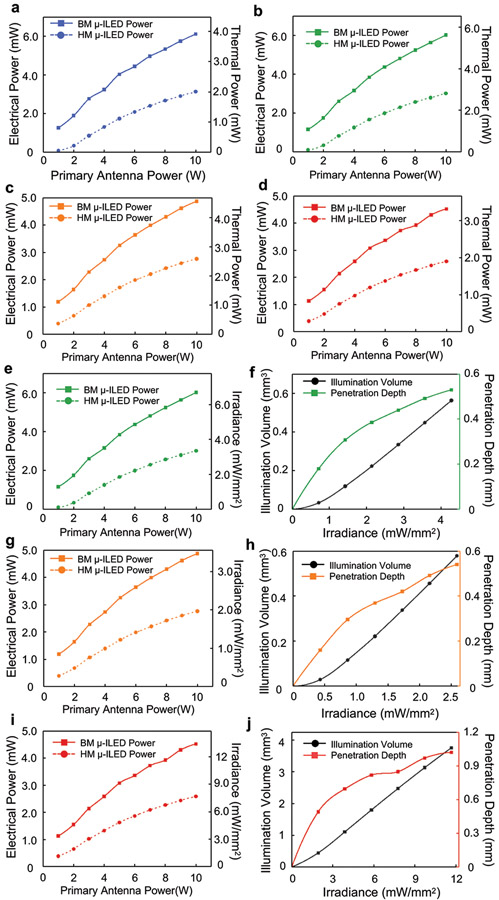

This section discusses the illumination intensity and excitation volume for given operational parameters, as well as the associated thermal loads on the adjacent tissue. Supplementary Fig. S12 summarizes current to voltage (IV) measurements (Supplementary Fig. S12a) and electrical to optical power conversion characteristics (Supplementary Fig. S12b) for each μ-ILED. The energy conversion efficiency of the μ-ILEDs determines the thermal power generated (Supplementary Fig. S12c). The efficiency of the blue (460 nm), green (535 nm), orange (590 nm) and red (630 nm) μ-ILEDs are 36.1%, 6.6%, 6.4% and 26.7%, respectively. These parameters, together with the electrical power wirelessly harvested by the device, define the illumination intensities. Present studies consider RF power applied through an antenna on a standard 30 cm (w) x 30 cm (l) x 12 cm (h) experimental cage, in a double loop configuration at heights of 3 and 9 cm from the base (Fig. 4a). Simulated results for the magnetic field intensity distribution at the plane in the middle between the double loop antenna (Fig. 4a) reveal a spatially inhomogeneous magnetic field. Active voltage regulation implemented in the devices yielded constant power delivery to μ-ILEDs throughout the experimental enclosure.

Figure 4: Characterization of optical and thermal properties.

a, Simulated magnetic field intensity distribution at the central plane of a 30 cm (l) x 30 cm (w) x 15 cm (h) cage surrounded by a double-loop antenna at the heights of 3 cm and 9 cm. b, Electrical power supplied to HM and BM coils, and different μ-ILEDs (460 nm, 535 nm, 595 nm, 630 nm) as a function of internal working impedance at 8W of RF power applied to the transmission antenna. c, Maximum harvested power as a function of RF power applied to the transmission antenna for HM and BM coils. d, Maximum electrical and optical power for a single blue μ-ILED (460 nm) as a function of RF power applied to the transmission antenna for HM and BM devices. e, Illumination volume and penetration depth as a function of blue μ-ILED’s (460 nm) output irradiance (cutoff intensity 0.1 mW/mm2). f, Temperature change at the interface between μ-ILED and brain tissue as a function of operational irradiance of blue μ-ILED (460 nm) and its duty cycle at 20 Hz frequency.

HM and BM devices have different power harvesting capabilities due to differences in the sizes of the receiver coils. The IV characteristics of the μ-ILEDs (Supplementary Fig. S12a) define relationships between their electrical power and their internal impedance during operation (Fig.4b μ-ILED). The maximum power to the μ-ILED results when its impedance finds equilibrium with that of the receiver coil, as observed as the intersection between power-impedance characteristics curves in Fig. 4b. The power from the receiver coil also depends on the RF power applied to the transmission antenna. Figure 4c summarizes the maximum electrical power that can be harvested by HM and BM devices as a function of power to the transmission antenna. The maximum electrical power and corresponding optical irradiance that each blue μ-ILED can reach with respect to the power to the transmission antenna for HM and BM devices appears in Fig. 4d. Corresponding thermal powers are in Extended Data Fig. 6a. Similar information for other μ-ILEDs are in Extended Data Fig. 6b-6e, 6g, 6i. The power not consumed by the μ-ILEDs can be exploited for the control electronics and for future applications in biosensing or for novel illumination schemes that rely on arrays of μ-ILEDs.

The optical and thermal power levels described above (Supplementary Table S1) serve as the basis for numerical simulations of the illumination and temperature profiles through adjacent biological tissues, as detailed in the Methods. The transport of light through the brain depends on wavelength-dependent scattering and absorption coefficients, input power, as well as spatial and angular emission profiles. Supplementary Fig. S13-S14 show the optical emission and penetration profiles for all wavelengths. Dynamic voltage control further enables users to program the μ-ILED optical power and thus the illumination volume and penetration depth. Figure 4e shows this capability as a function of input optical power of a blue μ-ILED. Examples for other μ-ILEDs are in Extended Data Fig. 6f, 6h, 6j.

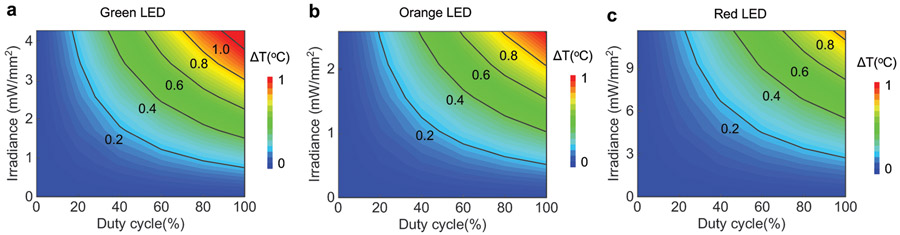

Numerical simulations of the temperature distributions in the surrounding brain tissue rely on the thermal power dissipation in the μ-ILED (Supplementary Table S1), the optical absorption and the thermal properties of the device and the surrounding biological tissue. Peak temperatures occur at the surface above the μ-ILED that directly contacts the brain tissue. Figure 4f shows this temperature increment for a range of irradiances and duty cycles, for a typical stimulation frequency of 20 Hz with a blue μ-ILED (additional wavelengths in Extended Data Fig. 7). The results presented here provide guidelines for choosing μ-ILED power and duty cycle for safe operation (See Methods and Supplementary Fig. S15 for details on simulation model and results).

Applications of Bilateral Stimulation and Subject-specific Programmability for Wireless Control of Place Preference and Social Behavior

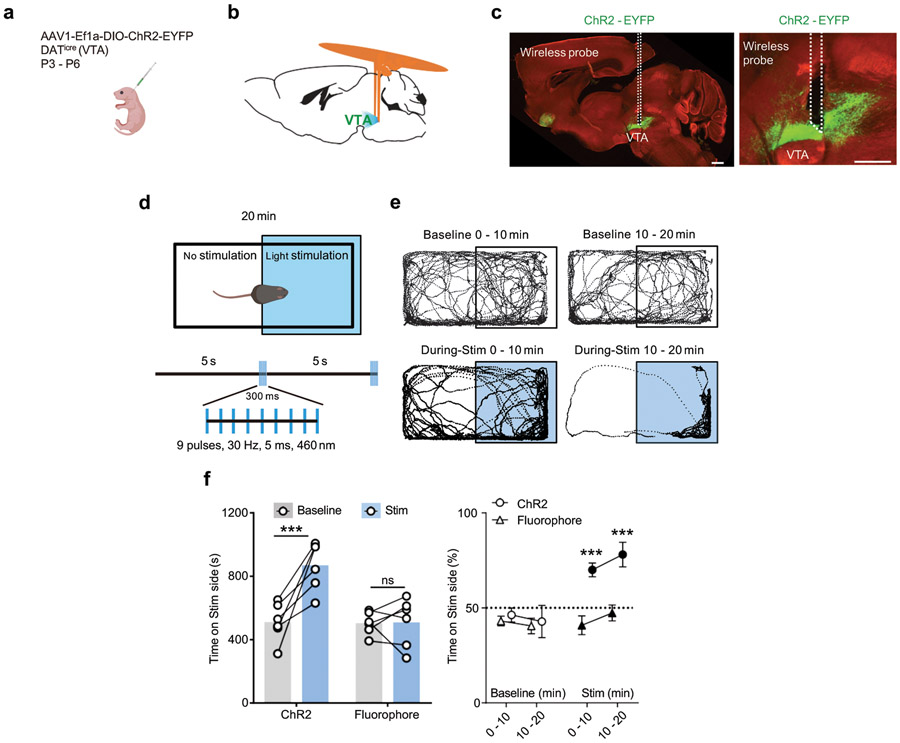

Next, we evaluate the function of the newly developed devices in a series of behavioral assays. Demonstrations of the functionality for the bilateral devices involve experiments on a group of midbrain dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), a brain region linked to the processing of reward 26,27. The bilateral design enables surgical implantation of μ-ILEDs into the two hemispheres of the brain in a single surgical operation. Stimulation probes with μ-ILEDs were positioned posterior to bilateral VTA, in DATicre animals, neonatally transduced with Cre-dependent ChR2-EYFP adeno-associated viral vector (AAV) in midbrain DA neurons (Extended Data Fig. 8a-8b). Probe placement and the expression of ChR2-EYFP were verified by histology after behavioral experiments (Extended Data Fig. 8c).

The first test uses a well-established paradigm of reward-based behavior, termed real-time place preference (RTPP). In this paradigm, burst excitation of DA neurons in the VTA and consequent dopamine release promote the animal’s preference for the side of the enclosure associated with optogenetic stimulation 8,28 (Extended Data Fig. 8d). Consistent with previous reports 8,28, burst wireless photostimulation (Stim) significantly increases the time animals spent on the stimulated side, in contrast to the absence of place preference in the baseline condition before stimulation (Extended Data Fig. 8e and 8f). Wireless photostimulation shows no effect on preference in control animals expressing a static fluorophore (Extended Data Fig. 8f). Further tests include the use of bilateral devices in a social interaction paradigm that involves a choice between a novel same-sex conspecific and an inanimate object, since the activation of VTA DA neurons promotes social behavior 20 (Fig. 5a). Compared to the baseline and fluorophore controls, time spent in the social interaction zone (14 x 26 cm) increases during light stimulation in ChR2-expressing animals, while interaction with the inanimate object remained unchanged (Fig. 5b-c).

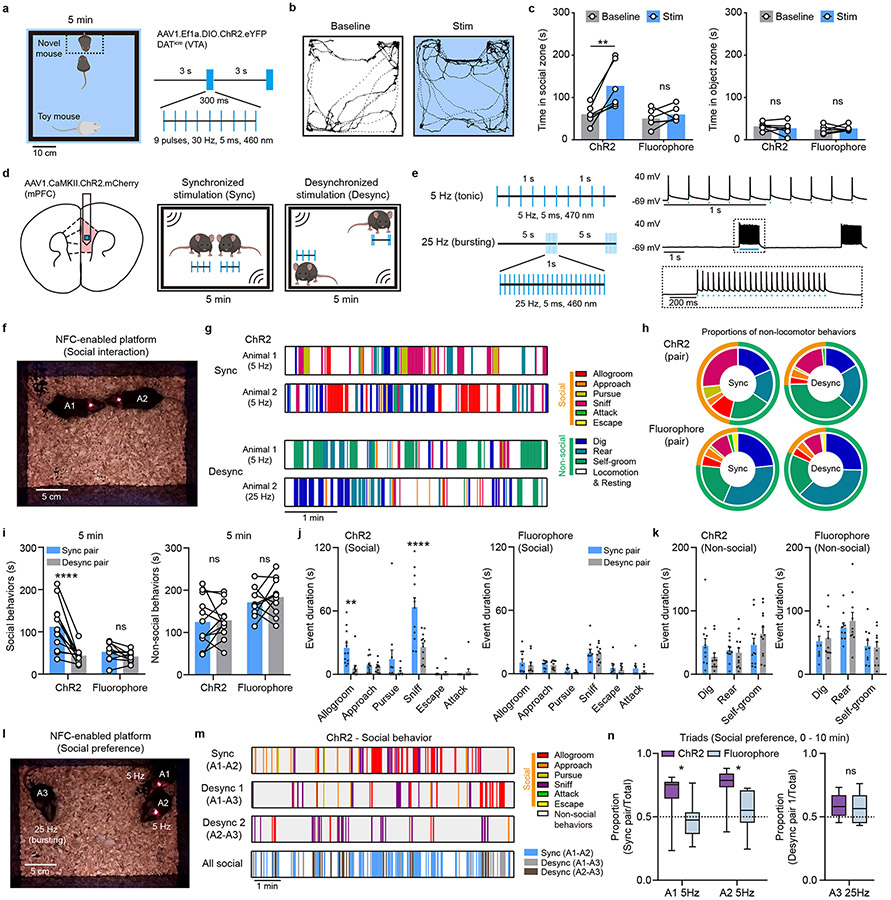

Figure 5: Bilateral stimulation and subject-specific programmability for wireless optogenetic control of social behavior.

a, Left: schematic of the arena for the social preference task and the stimulation area. Right: burst pattern of wireless light stimulation (460 nm). b, Example traces show position tracks in baseline and bilateral stimulation conditions from one animal. c, Left: summary data for total time spent in the social interaction zone in baseline and stimulation conditions. Two-way ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (Baseline vs Stim), ChR2, P = 0.0016, Fluorophore, P = 0.7763. Right: total time spent in the object interaction zone. Two-way ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (Baseline vs Stim), ChR2, P = 0.6208, Fluorophore, P = 0.8363. n = 6 animals/group. d, Left: schematic of virus transduction and probe implantation in mPFC. Right: the arena and experimental design for free social interaction assay. e, Left: stimulation patterns used to induce synchronized and desynchronized activity. Right: example traces from a current clamp recording of a ChR2.mCherry+ mPFC pyramidal neuron during optogenetic activation with blue light, as noted. f, Photograph of two mice interacting during synchronized wireless light stimulation. g, Behavioral sequences recorded in individual mice receiving synchronized or desynchronized stimulation during free social interaction. h, Proportion of time spent engaging in non-locomotor behaviors in mice expressing ChR2 or fluorophore controls, receiving synchronized or desynchronized stimulation. Proportion of time spent engaging in social behavior: ChR2 sync, 46.5%, ChR2 desync, 25.9%, fluorophore sync, 23.5%, fluorophore desync, 18.4%. n = 10-12 pairs/group. i, Left: summary data show the total time spent in social interaction in paired mice during synchronized and desynchronized stimulation. Two-way ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (Sync pair vs Desync pair), ChR2, P < 0.0001, Fluorophore, P = 0.6198. Right: total time spent engaging in non-social behaviors, exclusive of locomotion. Two-way ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (Sync pair vs Desync pair), ChR2, P = 0.9526, Fluorophore, P = 0.6608. n = 12 pairs/group. j, Left: summary data for social event durations for paired ChR2-expressing mice during synchronized and desynchronized stimulation. Right: same but for fluorophore control mouse pairs. Two-way ANOVA, Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (Sync pair vs Desync pair), ChR2: Allogroom, P = 0.0027, Approach, P = 0.9517, Sniff, P < 0.0001, Pursue, P = 0.0939, Escape, P = 0.9517. Attack, P = 0.9517. Fluorophore: Allogroom, P = 0.8903, Approach, P = 0.9541. Sniff, P = 0.9641, Pursue, P = 0.8996, Escape, P = 0.9092. Attack, P = 0.788. n = 12 pairs for ChR2 and 10 pairs for Fluorophore. k, Left: summary data for non-social event durations for paired ChR2-expressing mice during synchronized and desynchronized stimulation. Right: same but for fluorophore control mouse pairs. Two-way ANOVA, Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (Sync pair vs Desync pair), ChR2: Dig, P = 0.1941, Rear, P = 0.6816, Self-groom, P = 0.1941. Fluorophore: Dig, P = 0.822, Rear, P = 0.5568, Self-groom, P = 0.822. n = 12 pairs for ChR2 and 10 pairs for Fluorophore. l, Photograph of three mice receiving 5 Hz or 25 Hz stimulation in the social interaction arena, forming three synchronized or desynchronized pairs. m, Example social behavior sequences in synchronized or desynchronized pairs during free social interaction. n, Left, the proportion of social interactions for a focal animal in a triad with the synchronously stimulated one, over the total social interaction time, in animals receiving 5 Hz optogenetic stimulation. Two-way ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, ChR2 vs fluorophore, A1, P = 0.0145, A2, P = 0.0198. One sample t test, ChR2 vs random chance (0.5), A1, P = 0.0066, A2, P = 0.0003. Right, the proportion of social interactions for the focal animal receiving 25 Hz stimulation in a triad, desynchronized from both other present conspecifics, over the total social interaction time. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, ChR2 vs Fluorophore, P = 0.7207. N = 8-10 experiments/group. Data represent mean +/− SEM in bar graphs; box and whisker plots show quantiles and median. * P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

For a direct evaluation of the unique properties of the new generation wireless optogenetic devices—subject-specific programming and real-time adjustment—we tested the intriguing hypothesis emerging from recent imaging studies 29,30, which suggests that interbrain neuronal activity synchrony in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) may be sufficient to drive social interactions and social preference within groups of animals. This study would be challenging to carry out with traditional optical fibers, or large overhead devices, because tangling fibers would affect the animals’ natural social grooming and other emergent behaviors.

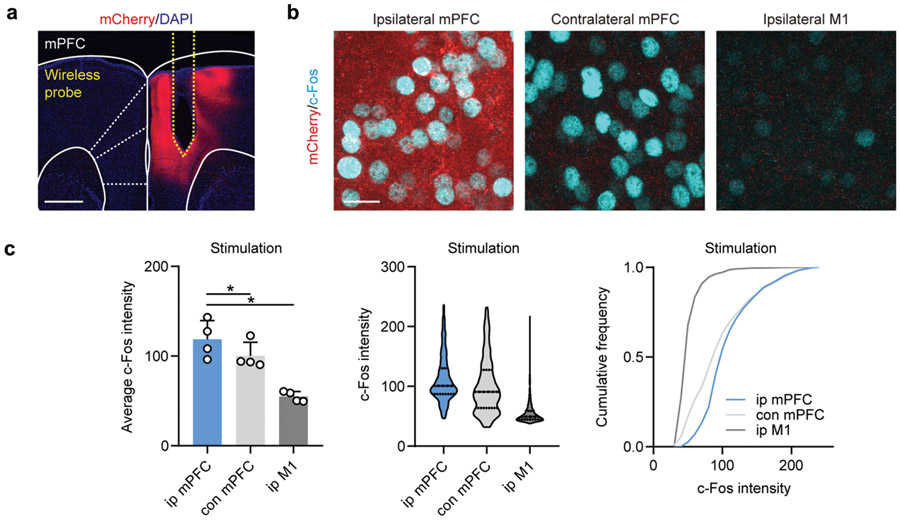

To directly manipulate interbrain activity across subjects, mice were virally transduced with AAV1.CaMKII.ChR2.mCherry in mPFC pyramidal neurons, followed by subsequent implantation of wireless optogenetic devices targeting mPFC (Fig. 5d). Synchronized (Sync) interbrain activity was generated using the same stimulation pattern for two mice (5 Hz, tonic stimulation), while distinct stimulation patterns (5 Hz tonic vs 25 Hz bursting) were used to induce desynchronized (Desync) activity across animals (Fig. 5e, and movie S9). We selected 5 Hz stimulation to induce synchronization, based on prior work reporting interbrain synchrony in the theta range as relevant for emergent interactive behaviors 31,32. The ability of mPFC pyramidal neurons to follow selected stimulation patterns was validated using current clamp recordings of mPFC neurons in an acute slice preparation, with temporally matched light stimulation using 470 nm whole field LED illumination (Fig. 5e). We also validated increased excitability in vivo using c-Fos immunofluorescent labeling (Extended Data Fig. 9a-9c). Mice receiving in vivo stimulation were allowed to interact with each other freely in an open-field arena (18 cm x 25 cm) (Fig. 5f, movie S10), with social and non-social behaviors scored for each subject or pair (Fig. 5g, see Methods for details). The proportion of social behavior in ChR2-expressing mice during synchronized optogenetic stimulation was 46.5% (n = 12 pairs), compared to 25.9% during desynchronized stimulation. In fluorophore expressing control mice (n = 10 pairs), the proportion of social behavior was 23.5% for Syn pairs and 18.4% for Desyn pairs (Fig. 5h). Figure 5h-j exclude locomotion from analysis to highlight the rarer behavioral events.

For ChR2-expressing mouse pairs, synchronized stimulation increased the amount of time spent engaged in social interaction compared to desynchronized stimulation, while the total social interaction time was not significantly different between two stimulation conditions for fluorophore control mice (Fig. 5i). Among social behaviors, the affiliative actions of social grooming and sniffing were significantly increased during synchronized stimulation, contributing to the overall greater amount of social interaction time for ChR2-expressing mouse pairs (Fig. 5j). No significant differences were observed in scored non-social behaviors across all conditions (Fig. 5i, k). Thus, in the context of dyadic social interactions, synchronized stimulation enhances social interaction but not non-social behaviors.

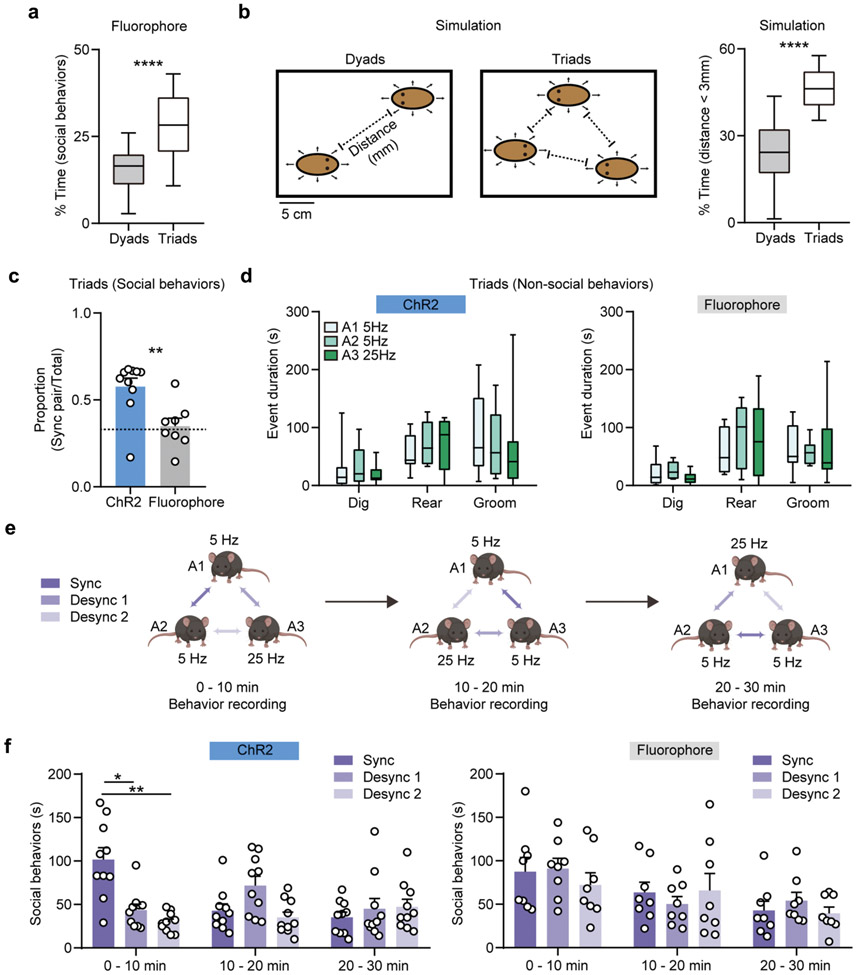

To further evaluate whether interbrain synchrony may shape social preference in more complex social contexts, we leveraged the individualized programmability of NFC-based wireless devices during dynamic social interactions involving three mice at the same time. Two animals were stimulated (tonically) at 5 Hz to form a synchronized pair, while another animal was receiving stimulus-number-matched 25 Hz bursting stimulation, in order to form an imposed desynchronized pairing with the other two mice (Fig. 5l, and movie S11). In the fluorophore control mice, we first observed that individuals spent more time engaged in social behaviors in triads, compared to dyads (Extended Data Fig. 10a). This increase in social interaction in more complex contexts likely reflects both an increase in the amount of time required to process social stimuli associated with multiple individuals and as a probabilistic function of increased density occurring with three mice rather than two in the same size arena. Evaluating the latter assumption, we simulated the conditions involving interacting dyads and triads in a virtual experimental space (18 x 25 cm open field). Our modeling result showed that individuals spent more time in proximity to another subject in triads compared to dyads (Extended Data Fig. 10b), consistent with experimental observations (Extended Data Fig. 10a). We next assessed the distribution of social interaction among the three possible pairs within the triad and found that, for ChR2-expressing triads, more social interactions were observed within the synchronized pair (Fig. 5m, Extended Data Fig. 10c). Focal animals, considered individually, spent more time with their synchronized pair than fluorophore controls, or than would be dictated by chance. Animals who could only partake in desynchronized pairs did not distinguish between interaction partners and did not deviate from chance (Fig. 5n). The social interaction events were more evenly distributed across animal pairs in fluorophore controls, and no salient preference were observed for individuals (Fig. 5n, Extended Data Fig. 10c). Non-social behaviors were similar for mice receiving different stimulation patterns in all conditions (Extended Data Fig. 10d).

To determine whether these arbitrarily imposed pairings are stable, we tested whether the optogenetically established social preference can be switched by changing stimulation patterns across pairs, in three 10 min long intervals. At the end of each interval, synchronized stimulation was arbitrarily re-assigned to another pair (Extended Data Fig. 10e). During the first period, as described, social preference was established in the synchronized pair, but no new pair preference could be induced during the following session. No significant preference was observed in any fluorophore control pairs (Extended Data Fig. 10f). Altogether, these data demonstrate the advantages of NFC-based wireless devices in the study of social behaviors, supporting the hypothesis that imposed interbrain synchrony shapes social interaction and social preference in mice.

Discussion

Real-time control over optical stimulation patterns is essential for many existing and emerging types of optogenetic studies in free-moving animals, particularly important for difficult to reach brain regions or complex behavioral tasks. The technology presented here employs well-developed NFC power transfer infrastructure and communication protocols, that, when aligned with commercial low-cost electronic components and scalable manufacturing techniques, yields a robust and flexible platform. Recent developments in application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) offer the opportunity to further integrate this customized multi component electronic system into a single specialized chip. This approach would share most of the digital and analog operations this platform supports in the context of user configurable optogenetics protocols, in a miniaturized form factor for minimally invasive in vivo applications 33,34.

In vivo optogenetic experiments illustrate powerful application opportunities for the new devices in behavioral neuroscience research 30. Our wireless optogenetic platform provides a unique opportunity in unconstrained naturalistic behavior, especially in the context of social interactions involving multiple free-moving subjects in the same environment. Programmability features enabled by the NFC platform support real-time manipulation of interbrain dynamics in a multi-brain framework experiment. Emerging evidence from multiple human 35,36,37 and several rodent and bat 29,38 studies suggest that interbrain neural synchrony arising during ongoing social interactions are associated with shared social variables among individuals. We were able to leverage the new NFC-based wireless optogenetic platform to directly test the hypothesis that interbrain synchrony specifically shapes social interactions in pairs or groups of mice. We observed paired mice display more social behaviors when they were receiving synchronized optogenetic stimulation of mPFC pyramidal neurons at 5 Hz, within the range of the theta band frequency (4-7 Hz) previously reported for interbrain synchronization 30,31,32. Moreover, within a group context, social preference arises within pairs that receive synchronized stimulation, but not between individuals with distinct stimulation pattern (5 Hz tonic vs 25 Hz burst). Our results suggest that imposed interbrain synchronization of neural process can causally shape ongoing social interaction and demonstrate the utility of our system to disentangle complex social phenomena.

Among other applications, next generation wireless neural devices with added functionalities will continue to deepen our understanding of social behaviors in the multi-brain level framework, potentially providing valuable mechanistic insights into atypical social behaviors (e.g., as in autism). A natural extension of this technology available with the current hardware is the implementation of closed-loop in vivo behavioral studies. External events, such as sensor readouts or real-time video feeds, can be used to conditionally TTL-trigger the modification of optogenetic stimulation/inhibition protocols in real-time, dramatically expanding the space of applications for this technology. In addition, future possibilities enabled by the current advancements include multimodal functionality in sensing and other diverse applications.

Methods

Fabrication of the flexible circuit and probe

Patterned laser ablation (ProtoLaser U4, LPKF Laser & Electronics) of a flexible substrate of a copper-polyimide-copper laminate (18, 75 and 18 μm; Dupont, Pyralux) defined the circuit interconnects, the bonding pads for the electronic components and the geometry of the probe. Flexible printed circuit board with customized designs offered by commercial companies (e.g. PCBWay) would also work. Conductive pastes (Leitsilber 200 Silver Paint) filled laser-plated via holes through the substrate to electrically connect circuits on the top and bottom sides. Hot air soldering using low temperature solder (Indium Corporation) bonded packaged components and μ-ILEDs (TR2227, CREE, for emission at 460 nm and 535 nm; TCE12, III-V Compounds, for emission at 590 nm and 630 nm) to the respective pads. Chemical vapor deposition (Specialty Coating Systems™ Inc.) formed conformal coatings of parylene (14 μm) to encapsulate the devices. Laser cut tungsten stiffeners (50 μm; Sigma-Aldrich) were bonded onto the back sides of the probes with a thin layer of epoxy (DEVCON) to provide enhanced mechanical rigidity for controlled implantation into the brain. A second layer of parylene (14 μm) and a dip-coated layer of poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS; Sylgard™ 184, Dow Inc.) completed the formation of a soft encapsulation structure. The BM devices required extra assembly steps before dip coating with PDMS, as described subsequently.

Fabrication of mechanically compliant interconnects for back subdermal devices

Fabrication began with spin coating a layer of poly(methylmethacrylate) (3000 rpm, 30s; PMMA A8, MicroChem Corp) on a silicon wafer substrate. Chemical vapor deposition formed a film of parylene (5 μm) over the PMMA. Electron beam evaporation (AJA International Inc.) yielded a multilayer stack of Ti (20 nm)/Cu (300 nm)/Ti (20 nm)/Au (50 nm), from bottom to top. Photolithography (MLA 150, Heidelberg Instrument) and wet chemical etching defined patterns in this metallic stack in the serpentine geometries of the interconnection traces. Chemical vapor deposition formed a second film of parylene (5 μm) on these patterned metal traces. Sputter deposition (AJA International Inc.), photolithography and reactive ion etching (RIE; Samco Inc.) patterned a layer of SiO2 (60 nm) as an etch mask. RIE of the exposed parylene to define geometries that matched those of the serpentines, with exposed contact pads for electric connections. The entire structure was transferred from the substrate to water soluble tape (AQUASOL) upon dissolving the PMMA by immersion in acetone. Sputter deposition formed a uniform layer of SiO2 (30 nm) on the system while on the tape. Exposing the SiO2 and a thin layer of silicone elastomer (Ecoflex 00-30, Smooth-On Inc.) to ultraviolet induced ozone (UVO Cleaner Model 144AX; Jelight Company Inc.) created surface hydroxyl termination on both surfaces. Physically laminating the two and then baking at 70 °C for 10 min in a convection oven (Isotemp Microbiological Incubator, Fisherbrand) created a strong adhesive bond. Immersion in warm water dissolved the tape to complete the fabrication process. Several companies can support fabrication steps. For example, Special Coating Systems™ Inc. offers chemical vapor deposition of parylene. Thinfilms Inc. offers sputter deposition that yields thin metal multilayers and SiO2. In addition, most research universities offer micro-fabrication services toward science community. In this case, photolithography, wet chemical etching, and RIE can be made to order.

Assembly of back mounted subdermal devices

Laser ablation of a film of polyimide (75 μm; Argon Masking Inc.) created shadow masks that covered the parylene-encapsulated probes and flexible circuits and left the contact pads for electric connections exposed to allow removal of parylene in these regions by reactive ion etching. Hot air soldering with a low temperature solder electrically bonded the probes, interconnection serpentines, and flexible circuits. Dip coating with epoxy and PDMS further mechanically secured the joints and encapsulated the probes and flexible circuit. The final step involved encapsulation of the serpentine interconnects with a dip coated layer of a low modulus silicone (Ecoflex, 00-30).

Electronic device components

An RF harvesting module, built with a matching capacitor, high-speed Schottky diodes in a half-cycle regulation configuration, and a smoothing capacitor, supplied power to the system. The 0201 package configuration for these and other components minimized the overall size. A linear voltage regulator (NCP161, ON Semiconductors, 1x1 mm2) ensured a constant voltage supply. A low power, 8-bit microcontroller, (4x4 mm2, ATtiny84, Atmel) operating with preprogrammed firmware served as the control system. A dynamic NFC-accessible EEPROM (2x3 mm2, M24LR04E-R, ST) provided external data storage and access by a microcontroller on a write-in-progress event basis to update the device operation. Finally, control of intensity from the μ-ILEDs was implemented with a passive second order low pass filter coupled with a high impedance, ultra-low power operational amplifier (1.5x1.5 mm2, TLV8542, Texas Instruments).

Optical intensity measurement

An integrating sphere (OceanOptics FOIS-1) calibrated with a standard diffusive light source (OceanOptics HL-3 plus) enabled accurate measurements of optical output for all of the μ-ILEDs examined here. A semiconductor device analyzer (Keysight S1500A) supplied current to the μ-ILEDs, from 100 μA to 2 mA with a 100 μA interval, through a probe station (SIGNATONE 1160) during optical measurement. Corresponding software (OceanView) generated an output as irradiance flux over the wavelength spectrum from 350 to 1000 nm. A MATLAB integration script yielded the total optical output power at each current value.

Mechanical modeling

The commercial software ABAQUS (ABAQUS Analysis User’s Manual 2016) was used to design and optimize the shapes of the serpentine structures and material layouts of the interconnects in multilateral optogenetic devices to improve their mechanical performance and facilitate surgical implantation. For the HM devices, PDMS, parylene, copper, PI, and tungsten layers were modeled by composite shell elements (S4R). For the BM devices, the Ecoflex substrate was modeled by solid hexahedron elements (C3D8R), while other layers were modeled by composite shell elements (S4R), similar to the HM devices. Convergence tests of the mesh size were performed to ensure accuracy. The elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio values used in the simulations were 119 GPa and 0.34 for Cu; 2.1 GPa and 0.34 for parylene; 2.5 GPa and 0.34 for PI; 79 GPa and 0.42 for Au; 110 GPa and 0.34 for Ti; 60 kPa and 0.49 for Ecoflex.

Electromagnetic modeling

The commercial software Ansys HFSS (Ansys HFSS 13 User’s guide) was used to design and optimize the configuration of the double loop antenna to achieve relatively large, uniform magnetic fields in the cages for behavior experiments. The adaptive mesh (tetrahedron elements) together with a spherical surface (1000 mm in radius) as the radiation boundary, was adopted to ensure computational accuracy. The relative permittivity, relative permeability and conductivity of copper used for the simulations were 1, 0.999991 and 5.8×107 S·m−1 respectively.

Optical and thermal modeling

The light distribution and temperature change caused by continuous operation of implanted μ-ILEDs was simulated to quantify key functional parameters (i.e. penetration depth, illumination volume, temperature change) that describe the physiological interaction with the brain. Finite element analysis (FEA) was implemented with the commercial software COMSOL 5.2a (Equation Based Modeling User’s guide) for propagation of light emitted by blue, green, orange, and red μ-ILEDs with wavelengths λ = 460, 535, 590 and 630 nm, respectively, into mouse brain tissue, according to the Helmholtz equation,

| (1) |

where ϕ represents the light fluence rate in the brain, c is the diffusion coefficient, μa is absorption coefficient, and f is the source term. The isotropic diffusion coefficient can be written as 39.

| (2) |

where is the reduced scattering coefficient. The absorption and reduced scattering coefficients of the fresh brain, implanted probe materials, and μ-ILEDs are given in supplementary Table S2 and S3.

Similarly for the heat transfer analysis, finite element analysis was also implemented with the commercial software COMSOL 5.2a (Heat-Transfer Modeling User’s Guide) to compute the temperature change (ΔT) caused by the light emitted from the μLEDs, heat generated by thermal power of μ-ILEDs, brain’s metabolism, and blood perfusion to account for the physiological heat transfer phenomenon in the brain. The Pennes’ bio-heat equation describes the heat-transfer problem as 40,41.

| (3) |

where T is temperature, t is time; k, ρ, and Cp are the thermal conductivity, mass density and heat capacity of the brain, and ρb and Cb are the mass density and specific heat capacity of the blood, respectively. ωb denotes the blood perfusion rate 40 and Tb is the arterial blood temperature 40. Qmet is the heat source from metabolism in the brain, Qthe is the heat generated by thermal power of μ-ILEDs, and ϕ corresponds to the light fluence rate of the μLEDs calculated in the optical simulation. The thermal properties of the implanted probe and bio-heat input parameters used in the simulation are given in supplementary Table S4 and S5.

The brain tissue, implanted probe geometry, and the μ-ILEDs were modeled using 4-node tetrahedral elements. Convergence tests of the mesh size were performed to ensure accuracy. The total number of elements in the models was approximately 905,000.

In vivo studies:

Animals.

All experiments used young adult male wild-type C57BL/6J mice (6-12 weeks old and 20-30 g at start of experiments; Jackson Labs), maintained at ~25 °C and humidity ranged of 30% to 70%. Mice were maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 9:00 PM, reverse light cycle) and fed ad libitum. Mice were group housed (two to four per cage) prior to surgery, after which mice were individually housed in a climate-controlled vivarium. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health standards and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) of the US Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense (MRICD), Northwestern University and Washington University.

Surgical procedures.

Animals were anesthetized using isoflurane and their head and back fur was shaved. Mice were then mounted in a stereotactic frame with a heating pad, and an incision was made down the center of the scalp to expose the skull. Burr holes for implantation of the optogenetic probes were drilled in the skull using a variable speed surgical drill. Using the attachment flag, the optogenetic probes were stereotactically lowered into the designated brain region at a rate of ~100 μm/s until appropriately positioned. The probes were then affixed to the skull using cyanoacrylate to prevent further movement. For the BM devices, a second ~10 mm incision was made midway down and across the back. The subcutaneous fascia between the scalp and back incision were separated, and the wireless device was then pulled from the scalp incision posteriorly until it rested above the spine. Serpentine wires connecting the two optogenetic probes to the thin and flexible wireless antenna traveled subcutaneously through the neck to connect the two components. The incisions were sutured closed and animals were monitored and allowed to recover for several hours before transfer back to the cage area facility for appropriate post-surgical monitoring.

DATiCre neonates (P3-6) were transduced with AAV1.EF1a.DIO.hChR2(H134R).eYFP (3.55x1013 GC/ml), (Addgene viral prep # 20297/20298-AAV1, Dr. Karl Deisseroth) or AAV8-CAG-FLEX-GFP (3.1x1012 GC/ml, UNC vector core, Dr. Ed Boyden). Six weeks after virus transduction, wireless probes were positioned posterior to the VTA (referenced from bregma: − 3.1 mm anteroposterior, ± 1.5 mm medio-lateral and − 4.7 mm dorsoventral). C57BL/6 Mice (~P60) were transduced with AAV1.CaMKIIa.hChR2(H134R).mCherry (1.2x1013 GC/ml, Addgene viral prep # 26975-AAV1, Dr. Karl Deisseroth). Two weeks after virus transduction, wireless probes were positioned anterior to the mPFC (referenced from bregma: + 2.2 mm anteroposterior, + 0.5 mm medio-lateral and − 1.5 – 2.0 mm dorsoventral). Mice recovered for at least 5 days before behavioral experiments.

Histology

For hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, standard protocols were followed. Four μm thick issue sections adhered to slides were dewaxed and cleared with xylene, hydrated through incubation in a series of decreasing concentrations of alcohols (100-70%), stained with filtered hematoxylin, treated with an alkaline solution, and counterstained with eosin. Subsequently, sections were dehydrated in several changes of alcohol, cleared, and coverslipped. Sections were imaged using an Olympus VS120 microscope in brighfield mode. Colored bright field images of back tissue sections were automatically acquired and stitched by using automated slide scanner and a 40x objective.

For immunofluorescent c-Fos labeling, 50-80 μm thick sections were incubated with primary antibody with rabbit anti-c-Fos in 0.5% triton X-100 PBS overnight at 4°C (1:10000; Cat. No. 226003, Synaptic Systems, Goettingen, Germany). For evaluation of biocompatibility, rabbit anti-GFAP (1:1000, ab7260, abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), rabbit anti-IBA1 (1:1000, ab178846, abcam), and rabbit anti-Hemoglobin subunit alpha (1:500, ab92492, abcam) were used. On the following day, tissues were rinsed three times with PBS, reacted with anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 secondary antibody (1:500, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) for 2hrs at RT, rinsed again for three times in PBS. Sections were mounted on Superfrost Plus slides (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA), air dried, and cover slipped under glycerol:TBS (9:1) with Hoechst 33342 (2.5 μg/ml, Thermo Fisher Scientific). For c-Fos quantification, ~30 μm stacks with 2 μm-step size were acquired with a Leica SP5 confocal microscope for the following regions including ipsilateral mPFC, contralateral mPFC, and ipsilateral M1. All imaging parameters were constant across all samples and each channel was imaged sequentially with a 40x objective. Analysis was carried out in FIJI 42 using autothresholding and particle analysis scripts. The same analysis parameters were applied across all regions of interest.

Electrophysiology

Coronal brain slice preparation was modified from previously published procedures 43,44,45. Animals were deeply anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane, followed by a transcardial perfusion with ice-cold, oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM) 127 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2.0 CaCl2, 1.0 MgCl2, and 25 glucose (osmolarity 310 mOsm/L). After perfusion, the brain was rapidly removed, and immersed in ice-cold ACSF equilibrated with 95%O2/5%CO2. Tissue was blocked and transferred to a slicing chamber containing ice-cold ACSF, supported by a small block of 4% agar (Sigma-Aldrich). Bilateral 250 μm-thick mPFC slices were cut on a Leica VT1000s (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) in a rostro-caudal direction and transferred into a holding chamber with ACSF, equilibrated with 95%O2/5%CO2. Slices were incubated at 34°C for 30 min prior to electrophysiological recording. Slices were transferred to a recording chamber perfused with oxygenated ACSF at a flow rate of 2–4 ml/min at room temperature.

Current clamp whole-cell recordings were obtained from neurons visualized under infrared DIC contrast video microscopy using patch pipettes of ~2–5 MΩ resistance. mPFC neurons expressing ChR2 were identified by the expression of mCherry. To activate ChR2-expressing pyramidal neurons in the mPFC, tonic light pulses at 5 Hz or bursting light pulses at 25 Hz (1s-long burst every 5s) were delivered at the recording site using whole-field illumination through a 60X water-immersion objective (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a PE4000 CoolLED illumination system (CoolLED Ltd., Andover, UK). Recording electrodes contained the following (in mM): 135 K-gluconate, 4 KCl, 10 HEPES, 10 Na-phosphocreatine, 4 MgATP, 0.4 Na2GTP, and 1 EGTA (pH 7.2, 295 mOsm/L). Recordings were made using 700B amplifiers (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA); data were sampled at 10 kHz and filtered at 4 kHz with a MATLAB-based acquisition script (MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Experimental setup for behavioral studies.

A host computer supports a customized graphical user interface (GUI), developed in MATLAB, and connected to the RF power module and NFC reader that operates the ISO15693 NFC communication protocol (LRM2500-A, FEIG Electronics). The computer connects to the RF power module via RS232 serial communication (a RS232 to USB converter was used in order to compensate the lack of physical RS232 ports in modern computers). The power module (Neurolux Inc.) drives a dual loop antenna that wraps around the experimental enclosure. An antenna tuner (Neurolux Inc.) provides impedance matching between the RF power module and the antenna to efficiently transmit power and communication signaling. The customized GUI controls the information flow via write/read commands to the NFC optogenetic devices via the NFC reader. Up to four devices can be addressed independently using their unique device identifier codes. A straightforward modification to the GUI can support additional devices. The write/read commands allow modification of illumination parameters, activation/deactivation of the μ-ILEDs, or activation of two devices simultaneously. In addition, this interface permits control of the RF module such as the power output. Although not implemented here, further on-demand activation of a target device via external signal controls such as TTL represents a natural extension of this system.

Real-time place preference

Mice were placed in a custom two-compartment conditioning apparatus (61 x 30.5 x 30.5 cm) as described previously 8,28. Mice underwent a 20 min trial where entry into one compartment triggered a burst of wirelessly powered photostimulation of 300 ms at 30 Hz (5 ms pulse width). Burst stimulations were delivered every 5 s while a mouse remained in the stimulation-paired chamber. Departure from the stimulation-paired side and entry into the other chamber side resulted in the cessation of photostimulation. The stimulation side was decorated with vertical grating pattern and the no-stimulation side with horizontal gratings. Mice were excluded from the study if they showed preference for either side in the baseline condition without photostimulation. The video recorded in each session was analyzed by Toxtrac 46. Time spent in each side was quantified as a measurement of place preference. Data were analyzed blind to conditions.

Social preference with DA stimulation

Mice underwent the social interaction test during a 5 min episode. A same-sex novel mouse was placed in a plastic mesh cage (10 x 6 cm) on one side of the open field (44 x 44 cm). A mouse-shaped object was placed on the opposite side. The experimental mouse was allowed to freely explore the open field for 2 min before a novel mouse and object were placed into the arena. Videos analyzed by Toxtrac 46 were used to measure the amount of time the experimental mouse spent in the ‘interaction zone’ (14 x 26 cm around the center of mesh cage or object). One day following a baseline session without stimulation, burst light stimulation (300 ms burst every 3 s, 9 pulses at 30 Hz in each burst, 5 ms pulse width) was delivered during the test period, and the interaction times with the new mouse and the inanimate object were measured. Data were analyzed blind to conditions.

Social interaction and preference with interbrain synchrony

In paired mice social interaction experiments, two male mice implanted with wireless optogenetic devices were placed in an open-field arena (18 x 25 cm) for free social interaction. For paired mice social interaction experiments, pairs were receiving synchronized or desynchronized stimulation for 5 min period. During synchronized session, two mice were simultaneously stimulated at 5 Hz (5 ms pulse width). During desynchronized session, one mouse was stimulated at 5 Hz, while the other mouse was receiving bursting optogenetic stimulation (1 s burst every 5 s, 25 pulses at 25 Hz in each burst, 5 ms pulse width). The order of synchronized and desynchronized sessions was randomized for pairs. All animals were habituated to the open-field arena for 5 min before testing. For triple-mice social preference, each experiment was consisted of three sequential sessions (10 min for each). During each session, two mice were simultaneously stimulated at 5 Hz and the third mouse received bursting stimulation at 25 Hz. At the end of each session, stimulation patterns and the synchronized pair were reassigned.

The videos recorded at 25 fps were analyzed by Behavioral Observation Research Interactive Software (BORIS) 47. Behaviors were manually scored for individual animals or pairs, as noted in the results and figures. Investigators were not blinded to the stimulation patterns displayed by the indicator LEDs. Behavioral events were converted into binary vectors for each type of behavior using 1 sec bins to generate behavioral sequences. A total of nine social and non-social behaviors were quantified. Social behaviors included allo-grooming, approach, pursue, sniff, attack, and escape. Non-social behaviors included self-grooming, digging, and rearing. Total time spent engaged in social interaction and non-social behaviors were calculated for comparisons among conditions.

Simulation of subject proximity

Mice were modeled as ellipses with a 60 mm major and 30 mm minor axis. Their movement was simulated in a 250 by 180 mm arena. For each movement, each object’s speed was sampled from a Gaussian distribution with a mean of 0.09 mm/ms and standard deviation of 0.06 mm/ms, matching the distribution of reported mouse speeds 48. Movement duration was chosen to be on average 1/5th of body length, fixed at 133.33 ms. The simulated objects were initially placed equidistantly across the arena width, at half the arena height. The first movement direction was sampled from a uniform distribution over 0, 2pi. Each subsequent movement was sampled from a Gaussian distribution centered at the object's previous heading direction with a standard deviation of pi/4. If the object encountered a wall, its movement direction was then sampled from a uniform distribution over 0, 2pi. Objects were not allowed to overlap. Objects were considered interacting if their perimeters were < 3 mm from each other.

MicroCT imaging

Animals were anaesthetized with isoflurane and placed inside a preclinical microPET/CT imaging system (Mediso nanoScan scanner). Data were acquired with ‘medium’ magnification, 33 μm focal spot, 1 × 1 binning, with 720 projection views over a full circle, with a 300 ms exposure time. Three images were acquired, using 35 kVp, 50 kVp and 70 kVp (where kVp is peak kilovoltage). The projection data was reconstructed with a voxel size of 34 μm using filtered (Butterworth filter) back-projection software from Mediso Nucline (v2.01). Throughout imaging, respiratory signals were monitored using a digital system developed by Mediso (Mediso-USA). Advanced imaging studies used five 25-30 g C57BL/6 mice (C57BL/6NCrl) and three 250-300 g Sprague Dawley rats from Charles River. In mice, the ventral tegmental area was targeted for probe placement (referenced from bregma: −3.3 mm anteroposterior, ±0.5 mm medio-lateral and −4.4 mm dorsoventral). In the rats, the probes were placed −5.0 mm anteroposterior, ±2.4 mm medio-lateral and −5.0 mm dorsoventral. Data were analyzed with Amira (v2020.2, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Bone density was calculated from Mean (Hu) acquired with 50 kVp.

Mobility studies:

Stereotaxic surgery

Mice were anesthetized in an induction chamber (3% isoflurane) and then placed in a stereotaxic frame (Kopf) where they were maintained at 1-2% isoflurane. All surgeries were performed using aseptic conditions. Meloxicam (0.5 mg mL−1, subcutaneous injection) and lidocaine (0.25-0.5%, intradermal injection) were given as preoperative analgesia. After a stable plane of anesthesia was reached, a midline incision was made to expose the skull. Two burr holes were drilled at the site of viral injection (all groups) and probe placement (for tethered and wireless subjects). Surgical controls only received viral injections; no probes were implanted. All mice were injected bilaterally with 200 nL per side of AAV-CaMKIIα-hChR2-EYFP (UNC Vector Core, Dr. Karl Deisseroth) at a rate of 100 nL min−1 via microsyringe pump (UMP3; WPI) and controller (Micro4; WPI). After 5 minutes, the injection needles (10 μL NanoFil with 33 ga needles; WPI) were raised 300 μm and left in place for an additional 3 minutes to allow for diffusion of the virus throughout the tissue. Mice were then implanted bilaterally with fiber optic ferrules (1.25 mm, stainless steel; Thorlabs) that contained the implanted optical multimode fibers (200 μm, 0.22 NA; Thor Labs) or wireless μLED optogenetic probes using a stereotaxic holder (PH-300, ASI Scientific) and affixed with dental cement (fibers) or cyanoacrylate (wireless). Mice were allowed to recover for 2.5 weeks before acclimation to tethering and/or handling began. All animals gained weight post-surgery and readily built nests in their new cages.

Open field test

To perform the open-field analysis for sham and head mounted device implanted mice, we utilized a 42 L × 42 W × 20 H cm open arena. Animals were placed in the center of the arena and allowed to freely explore the open-field enclosure for 15 min, under low light conditions (50 lux), while they were recorded with an overheard camera. Digital recordings were collected and analyzed using Anymaze video tracking software, measuring the total distance, average speed, in addition to the time and distance travelled in both the inner and outer zones. The center zone was defined as a square comprising 50% of the arena.

The novel open field tests for sham, fiber implanted, and back mounted device implanted mice were carried out during the more active dark cycle (9:00 AM-9:00 PM) between 10:00 AM and 11:00 AM in a sound-attenuated lab maintained at 23°C. All tests were performed in a 908-cm2 (34 cm diameter) circular cage that was novel for the animals to encourage exploratory activity and maximize movement. For fiber optogenetic probe tethering, a 1x2 step-index multimode fiber optic coupler (105 μm, 0.22 NA; Thor Labs) was connected to a low torque hybrid rotary joint (0.22 NA; Doric Lenses Inc.) and to the bilateral implanted ferrules in the mouse skull. No extra connections were required for mice implanted with wireless probes or the surgical controls. All mice were gently handled for three days before behavioral tests to acclimate the subjects to the experimenter and to reduce stress. Additionally, fiber-implanted mice were habituated to fiber optic tethering in their home cages for 3 days before behavioral experiments to prevent acute stress from interfering with their behavior on test days. For testing, mice (n = 6-8 per group) were placed in the center of the open field and allowed to roam freely for 1 hr. Movements were video-recorded and motion analysis was performed offline using Ethovision ® 11 software. Distance traveled, velocity, and number of stops and starts were calculated in 1 and 5 minute bins for the duration of the recording and statistically compared amongs groups using an ANOVA.

Running wheel

Similar to the open field tests, these experiments were carried out during the more active dark cycle to promote higher activity. Animals were placed in a circular cage containing a Med-Associates Low-Profile Running Wheel that measures revolutions per minute of running activity. All animals had access to running wheel enrichment devices in their home cages to acclimate them to the device prior to recording. Animals were run for three consecutive days to further promote consistent activity and minimize potential negative effects from acute tethering of the fiber optic group. Data reported are from the third day of recording using time bins from 5 to 65 minutes.

Positional tracking of the mice

Tracking the position of four body parts of a mouse during natural behaviors provided estimates for the requirements on mechanical deformations of soft interconnects mounted subdermally on the back. The procedure used a mouse in a transparent chamber (30 cm x 30 cm), recorded from one side for one hour (Raspberry Pi, 25 frames per second). Tracking information was determined using DeepLabCut 22. Manually marking four body parts (head, neck, back, and tail) in 200 representative frames generated a training set for a convolutional neural network designed to locate these four body parts on a frame-by-frame basis. A subset of frames (~9000) with the animal’s major axis oriented perpendicular to the camera were used to compute the deformation of the body regions. Estimates of mechanical compression and stretching used the combined distance from head to neck and neck to back. The bending curvature was represented as the radius of the arc formed by the points of head, neck, and back. All data points were compared to the medians of the data set (referenced as the non-deformed state) to indicate the level of device deformation during natural activity.

Statistical analyses

Group statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 software (GraphPad, LaJolla, CA). For N sizes, the number of animals is provided. No statistical methods were used to pre-determine sample sizes but our sample sizes are similar to those reported in previous publications 8,29,49. All samples were randomly assigned to experimental groups. Data from failed devices were excluded from the analysis. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM, or individual plots. Data distribution was assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested. For two-group comparisons, statistical significance was determined by two-tailed Student’s t-tests. For multiple group comparisons, analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were used, followed by post hoc analyses. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on experimental design and reagents is available in the Nature Research Life Sciences Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Data availability

Raw data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The data analyzed during the current study are available https://github.com/A-VazquezGuardado/Real-time_control_Optogenetics

Code and software availability

All computer code and customized software generated during and/or used in the current study is available https://github.com/A-VazquezGuardado/Real-time_control_Optogenetics.

Extended Data

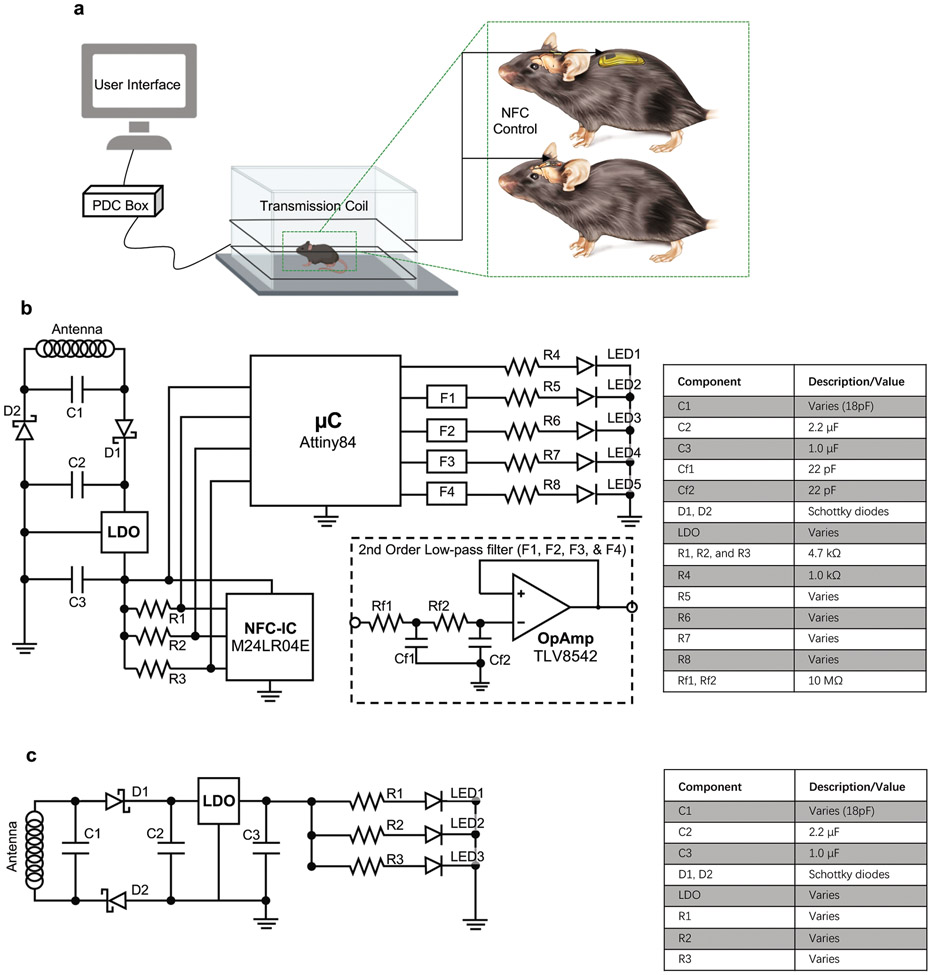

Extended Data Figure 1. Electrical circuit implemented in the NFC-enabled platform.

a, Experimental platform includes implanted device, transmission antenna, power distribution (PDC) box, and PC with user interface. The device is wirelessly programmed through a PC in a real time manner through near field communication (NFC) control over the stimulation parameters. b, The NFC corresponds to an RF addressable memory chip supporting ISO15693 protocol. The microcontroller interfaces to the NFC memory via I2C communication protocol. Up to four channels are supported by the microcontroller’s firmware, independently controlled by the end user. Each channel is filtered using a second order low–pass passive filter whose output is coupled by a high impedance voltage follower that drives the μ-ILED. The number of channels to be used depends on the type of implant: two for head mounted or four for back mounted. c, Simple voltage regulation circuit that implements a low dropout regulator (LDO) that passes current directly to the μ-ILEDs and resistor after rectification. The component bill of materials is also shown.

Extended Data Figure 2. Mechanical deformations for head mounted devices.

a, b, FEA simulations and photographs of 30% stretching of different head mounted devices. c, FEA simulations and photographs of head mounted devices deformed into various configurations after implantation.

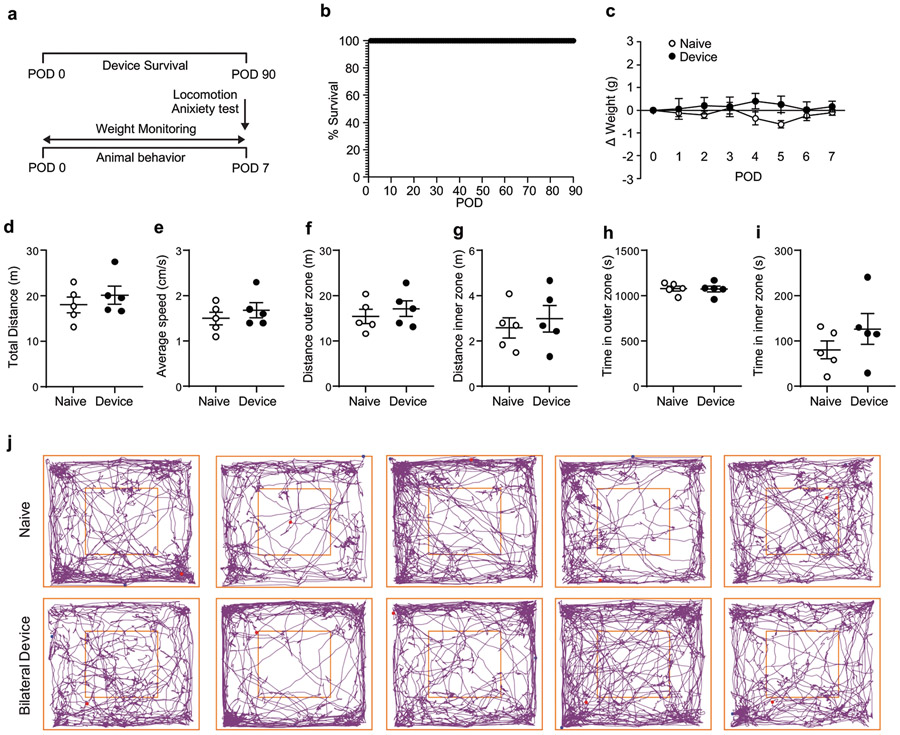

Extended Data Figure 3. Device longevity and behavioral outcomes for head mounted devices.

a, Cartoon representation of the timeline for monitoring device longevity and animal postoperative behavior. b, Routine testing of head mounted devices for 90 days (n=5 animals). c, Normalized weight assessment for 7 postoperative days (POD) after implantation of head mounted device (two-way ANOVA Sidak’s multiple comparison test; POD1 P = 0.9998, POD2 P = 0.9491, POD3 P > 0.9999, POD4 P = 0.3731, POD5 P = 0.2038, POD6 P = 0.9966, POD7 P = 0.9966; n=5 naïve & n=5 device animals). d, Total distance traveled (P = 0.6905), e, Average speed (P = 0.5952), f, Distance in the outer zone (P = 0.6905), g, Distance in the inner zone (P > 0.9999), h, Time in the outer zone (P > 0.9999), i, Time in the inner zone (P = 0.5476). (d-i), Locomotion effects of implantation were assessed using the open field test and a variety of parameters were measured (two-tailed unpaired t-test, Mann Whitney test; n=5 naïve & n=5 device animals). j, Graphical representation of individual animal behavior, implanted animals (top row) versus naïve controls (bottom row) in the open field test. Outer and inner squares represent the two zones. All data are represented as mean +/− SEM.

Extended Data Figure 4. Biocompatibility of injectable probes and back mounted implants.