Abstract

This cross-sectional study provides preliminary findings from one of the first functional brain imaging studies in children with chronic kidney disease (CKD). The sample included 21 children with CKD (14.4 +/− 3.0 years) and 11 healthy controls (14.5 +/− 3.4 years). Using fMRI during a visual-spatial working memory task, findings revealed that the CKD group and healthy controls invoked similar brain regions for encoding and retrieval phases of the task, but significant group differences were noted in the activation patterns for both components of the task. For the encoding phase, the CKD group showed lower activation in the posterior cingulate, anterior cingulate, precuneus, and middle occipital gyrus than the Control group, but more activation in the superior temporal gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, and the insula. For the retrieval phase, the CKD group showed under-activation for brain systems involving the posterior cingulate, medial frontal gyrus, occipital lobe, and middle temporal gyrus, and greater activation than the healthy controls in the postcentral gyrus. Few group differences were noted with respect to disease severity. These preliminary findings support evidence showing a neurological basis to the cognitive difficulties evident in pediatric CKD, and lay the foundation for future studies to explore the neural underpinnings for neurocognitive (dys)function in this population.

Keywords: fMRI, Pediatric Chronic Kidney Disease, Brain-Behavior Relationships in Pediatric CKD

Neurocognitive functioning in pediatric patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) has been studied for well over 30 years, with a consensus evolving that a variety of neurocognitive difficulties persist in this population across a wide age range and severity level.1 Neurocognitive difficulties have been documented even in mild to moderate CKD.2–3 Factors suspected to contribute include estimated glomerular filtration rate, proteinuria, high blood pressure, blood pressure variability, and low levels of bicarbonate.4 Overall intellectual functioning is typically thought to fall within the low average range, with specific neurocognitive difficulties in attention regulation, working memory, and set-shifting capabilities.1,4,5

With the presence of neurocognitive deficits and dysfunction in pediatric CKD, even after controlling for sociodemographic and CKD-related covariates, there is a need to better understand the neurological underpinnings to this cognitive presentation. In the adult literature, a burgeoning number of studies have addressed this issue, with well over 30 studies documenting brain impairments in adults with CKD.6 These studies have included both structural neuroimaging studies and several functional imaging studies. For the structural neuroimaging studies, the primary technique used was MRI, with several studies using CT. Findings indicated the presence of white matter injury, cerebral small vessel disease, silent infarcts, generalized vascular damage, and cerebral microbleeds.6 For the functional neuroimaging studies, the primary techniques used were SPECT, transcranial Doppler ultrasonography, and regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) using 133Xe inhalation, with findings revealing lower cerebral blood flow in the left middle temporal gyrus and right parahippocampal gyrus, very similar to a pattern seen in adults with major depression.6

In contrast, the neuroimaging corpus for pediatric CKD comprises approximately 15 studies, with nearly every study utilizing structural imaging techniques. Collectively, these studies have shown similar structural findings to those found in adults including focal and multifocal white matter injury in the internal capsule,7 cerebral atrophy, enlarged ventricles, enlarged cortical sulci, brain infarcts, and gray matter involvement,8 including gray matter in the cerebellum region.9 In one of the first pediatric studies to provide cognitive correlates of neuroimaging findings, Hartung et al.8 used MRI to show that children and young adults with CKD evidenced lower whole brain volume and lower cortical and left parietal gray matter volumes than controls, but these findings were not maintained in adjusted analysis, and neurocognitive performance was not related to targeted region of interest volumes in those with CKD. Most recently, using MRI Solomon et al.9 showed that cerebellar gray matter volume was significantly smaller in children with CKD versus controls, while volume of cerebral gray matter was larger in CKD. In contrast to Hartung et al., Solomon et al. found smaller gray matter volume in the cerebellum regions to be significantly related to disease severity and to the cognitive finding of poorer verbal fluency.

While the structural imaging studies have begun to shed light on the neurological contributions to the neurocognitive presentation of children with CKD, to date there have been precious few functional imaging studies. In the first functional study to date, Liu et al.10 examined the effects of kidney disease on brain function in children and young adults (ages 9 to 25 years) with CKD using MRI arterial spin labeling to assess cerebral blood flow (CBF). In comparison to healthy controls, findings showed the children and young adults with CKD to have higher global CBF than controls, with white matter CBF having a small but significant correlation with blood pressure. These findings implicate the potential for disrupted cerebrovascular autoregulation and involvement of the default mode network (DMN)—an important set of neural connections comprised of the medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate, and angular gyrus which has been linked to wakeful resting state and social working memory. A significant correlation of large magnitude also was noted in the children and young adults with CKD between the precuneus and ratings of executive function. Similarly, using functional MRI to assess resting state, Herrington et al.11 (this issue) examined the functional connectivity in children and young adults with CKD with mild to moderate CKD in comparison to healthy controls. Using seed-based multiple regression, decreased connectivity was observed in the anterior cingulate region of the DMN. Decreased connectivity within dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, paracingulate gyrus, and frontal pole were significantly correlated with disease severity. These finding suggest the disruption of attention regulation in the presence of CKD.

Taken together, these findings show the importance of using neuroimaging procedures to identify potential neurological underpinnings to the cognitive deficits and dysfunctions that have been demonstrated in children and adolescents with CKD. While there are a number of structural brain imaging studies, there are only a few emergent functional imaging studies with children, and no functional imaging studies that have focused on neurocognitive outcomes other than attention. To address this gap in the pediatric CKD literature, this pilot cross-sectional investigation was conducted to examine the activation patterns of relevant brain regions during a visual-spatial working memory task when compared to healthy controls. It is suspected that children and adolescents with CKD will show differential neural signatures in both the encoding and retrieval aspects of working memory when compared to healthy controls. Specifically, it is expected that the percent blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal change over the encoding and retrieval periods will be significantly lower in the ventral lateral and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and right posterior parietal cortex in CKD patients versus healthy controls. A secondary analysis will explore the impact of disease severity on these neural signatures during both working memory components, with greater disease severity expected to result in less brain activation in the targeted brain regions.

Methods

Participants

Twenty participants with CKD, 5 participants with transplant who were at least 2 years post-transplant, and 14 control participants were recruited for this study. The patients with CKD were recruited from a pediatric nephrology clinic in a large medical center in the southeastern USA and controls were enrolled from the catchment area surrounding the medical center via word of mouth, IRB approved public advertisements and primary care clinics. Exclusion criteria included: hospitalization within one-week, acute illness, claustrophobia, permanent metal devices (e.g., braces, shunts), current pregnancy or breastfeeding, and history of traumatic brain injury or other major neurological problems that would interfere with working memory performance (e.g., seizure disorder). Of the 39 study participants, 32 were included in the fMRI analysis. Three control participants and four participants with CKD were excluded. Of these cases, data from one control and one patient with moderate CKD were excluded because they had orthodontics that obstructed the MRI signal. One control’s data were excluded because pre-processing resulted in misregistration of the brain. Data from one control and 3 patients with CKD were excluded because excessive head motion made it difficult to interpret the images.

Measures

Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale:

Prior to their participation in the fMRI procedures, parents completed the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale-II12 in order to gain an estimate of overall level of functioning and, in conjunction with inclusion/exclusion criteria, to rule out intellectual disability. The VABS-II is completed by the parent/caregiver and for most participants was completed while their child was in the MRI scanner. Ratings from the VABS-II provide an overall estimate of functioning and includes questions addressing social skills, communication skills, and activities of daily living. An overall Adaptive Behavior Composite is generated. The VABS-II has excellent reliability and validity.

Working Memory Task:

The task is a delayed-response visual memory task using a CIGAL display. CIGAL is a computer program used to provide stimuli for fMRI tasks and to gather data on participant behavior (e.g., responses to stimuli and reaction time). Ten trials are collected per run, and 4 trials of data are collected for each patient during one MRI session for a total of 40 responses. During each trial, a participant is shown 4 red squares, each for 1 second, each in a different location. After a pause, a green square appears, and the participant is asked to indicate by a button press whether the green square is in the same location as one of the previous 4 red squares or in a different location. This encoding period lasts 4 seconds, followed by a delay of 17 seconds, then the retrieval period. The timing of the presentation and response in this design allows the hemodynamic response correlating with each phase of working memory to be isolated. This task was previously used to map the visuospatial working memory network in children13 and to assess visuospatial working memory in females with Turner syndrome.14

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging:

Data Acquisition.

Functional images were obtained using a 3.0 Tesla Siemens Magnetom Allegra syngo MR 2004A. Functional images were acquired using gradient echo EPI (24 oblique slices, with near-isotropic voxels of 3.79*3.79*3.8mm, FOV 24 cm; image matrix = 642 TE: 30 ms; TR: 1500 ms; flip angle 80). Each functional imaging run began with four discarded RF excitations to allow for steady-state equilibrium. Preceding functional image acquisition, structural images were acquired using full brain MP RAGE, T1 weighted (1 mm3 isotropic voxels, acquisition matrix 192 × 256) and T2 weighted (1 mm3 isotropic voxels, acquisition matrix 256 × 256). High-resolution 3D full-brain images were acquired to aid in normalization and co-registration. All participants viewed the working memory task through LCD projector or goggles. Responses to the stimuli were given using a button box.

Assessing Usability of fMRI Data.

Quality analysis (QA) was conducted using tools developed by the Biomedical Informatics Research Network (BIRN).15 QA assessed number of volumes able to be reconstructed (fewer volumes indicating greater motion by the participant during the scan), signal-to-noise ratio, and motion in the x, y, and z planes. Head motion was assessed based on center of mass measurements in three orthogonal planes. Following QA, sets of functional data showing motion in the z-plane exceeding 5 mm were excluded from both the fMRI Software Library (FSL) and Eventstats analyses. In Eventstats, each behavioral response to the task was analyzed as a separate event. Any event showing more than 3 mm motion in any plane was excluded from the Eventstats analysis.

Preparing fMRI Data for Analysis.

Brain extraction, image registration, motion correction, and t-comparisons were conducted using the FSL FEAT tool, version 5.92.16 Brain extraction eliminates the imaging data representing participants’ skulls, skin, and eyes, so that the data representing the brain remain. In image registration, functional images are registered to a standard image—that is, all the images from different participants’ differently sized and shaped brains are aligned to a standard brain using identifiable spatial markers so that participants can be compared to each other. Although the standard brain template was developed based on adults’ brains, it has been found to be usable in fMRI studies for children as young as 7 years old.17–18 Images were co-registered first to each participant’s high resolution structural scan and then to the MNI 152 person 2-mm template using a 12-parameter affine transformation. Functional analyses were overlaid on the participants’ average high resolution structural scans in MNI space.

Head motion was corrected using the MCFLIRT tool, which began with the middle image in a time series and looked for an identity transformation between that volume and the next, then used that transformation to estimate the transformation between the next two volumes. These repeated identity transformations were used to average across volumes and create a new template image. The first and last volumes in the z-plane were doubled to capture as much data as possible. Corrections for the interleaved slice acquisition over the 1.5 seconds (TR) were made using a slice time correction algorithm. Images were spatially smoothed with a 5mm full width at half maximum Gaussian kernel to improve signal-to-noise ratio. High pass temporal filtering was used to cut off periods longer than 66 seconds.

Data Analysis

Preliminary data analyses examined differences between the CKD and control groups on chronological age, sex, and VABS-II Adaptive Behavior Composite. If any of these variables showed group differences, then that variable was used as a covariate in the FSL whole-brain analysis of BOLD percent signal change. Task accuracy (fraction of correct responses) and reaction time in patients with CKD and controls were compared using t-tests to determine if there were any significant differences between these variables on the working memory task.

For the fMRI analyses, we used tools from the FMRIB (Oxford University Centre for Functional MRI of the Brain) Software Library (FSL) (FMRIB’s Software Library, www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl). We used FEAT (FMRI Expert Analysis Tool) Version 5.92 [FSL 4.1.8] to submit functional data from individual runs to multiple regression analysis. The following pre-statistics processing was applied: motion correction using MCFLIRT,19 slice-time corrected, skull stripped using the FSL Brain Extraction Tool (BET), spatial smoothing using a Gaussian kernel of FWHM 5mm; grand-mean intensity normalization of the entire 4D dataset by a single multiplicative factor, using a high pass temporal filter of 100 s. Functional data were registered to a standard stereotaxic space (Montreal Neurological Institute, MNI).16 Head motion was detected by center of mass measurements. No subject had greater than a 5-mm deviation in the center-of-mass in any plane. Each imaging run began with four discarded RF excitations to allow for steady-state equilibrium.

Statistical analyses proceeded in three stages. First-level statistical analysis was performed using FMRIB’s improved linear model. We set up a statistical model for the working memory task. The working memory models comprised 2 regressors (i.e., encoding and retrieval phases of the working memory task). The hemodynamic response function was modeled with a double-gamma function (phase, 0 s). The temporal derivative of this time course was also included in the model for each regressor. To assess BOLD response changes related to the stimuli, we calculated the following contrasts: (1) Encoding-Retrieval and (2) Retrieval-Encoding. At the second-level analysis, we combined data across runs, for each subject, using a fixed-effects model. At the third-level analysis, we combined data across subjects using a mixed-effects model. Z-statistic (Gaussianized T/F) images were thresholded using clusters determined by z > 2.3 and corrected cluster-significance threshold of p = 0.05. For the prefrontal cortex (PFC) activation and between group comparisons, z-statistic images were set at p = 0.05 (uncorrected) to be also consistent with the previous results. All coordinates in the manuscript are reported in MNI space.

For the question pertaining to severity of CKD, one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted using the statistical software SPSS in order to determine whether there were statistically significant differences among all three groups—patients with severe CKD, patients with moderate CKD, and control participants—in either the encode or retrieve phase of the task.

Eventstats Analysis.

Region-of-interest (ROI) analyses were performed using custom MATLAB software developed by the Duke-UNC Brain Imaging and Analysis Center (Duke-UNC BIAC, Durham, NC). We masked each ROI region with statistically significant voxels (z > 2.3) in Encode activation. Epochs beginning 18 image volumes before the retrieval stimulus and continuing for 14 image volumes after the target event were extracted from the raw functional imaging data and averaged together over all runs to get a mean time course of raw MR signal. The average MR signal values were then converted to percent signal change relative to a pre_S1 baseline, defined as three time points preceding S1. Average percent signal change at each time point in the event epoch was calculated within each region of interest. The BOLD signal over time for each voxel was correlated with an empirically determined hemodynamic response waveform.14 Eventstats ROI results were analyzed in SPSS using one-way ANOVAs to compare average percent signal change in each region of interest across the two groups (patients and controls) over the entire course of the task. Individual participants’ peak amplitudes were also used to assess group differences in the encoding and retrieval phases of the task.

Post-hoc analyses

Due to the number of different tests being performed for this study, probability thresholds for the whole-brain analyses were adjusted post-hoc using the Holm-Bonferroni method. This procedure was performed by hand and the resulting lower p-values used to assess whether the findings can be deemed significant.

Ethics

The study was IRB approved and all participants and/or guardians provided informed consent and as appropriate informed assent prior to study participation.

Results

Sample Characteristics:

The characteristics of the final sample included in the study comprised 32 children and adolescents, ages 9 to 19 years old, and can be seen in Table 1. The CKD sample included 21 individuals with an average age of 14.4 (SD 3.0) years, 57% White (race was self-reported by parent), and 57% male. Etiology of CKD included systemic diseases resulting in kidney damage, urinary obstruction, hereditary or congenital nephropathies, and primary glomerulopathies. The CKD sample was stratified across mild-moderate CKD (i.e., estimated GFR > 30 to 90 ml/min/1.73m2; n = 10) or severe CKD (i.e., estimated GFR < 30 ml/min/1.73m2, dialysis or transplant dependent; n = 11). Estimated GFR (eGFR) was calculated using a modified version of the Schwartz formula.20 The final sample also included 11 healthy controls matched on chronological age and sex. This group was 14.5 years of age (SD 3.4), 82% White, and 45% male. There were no significant differences in age, sex, maternal education, or Vineland ABC scores between the participants who were retained in the study versus those who were not.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N = 32).

| Characteristic | Mild-Moderate (n = 10) | Severe (n = 11) | Total CKD (n = 21) | Control (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age in Years (SD) | 13.2 (3.1) | 15.5 (2.6) | 14.4 (3.0) | 14.5 (3.4) |

|

| ||||

| Vineland ABC Standard Score (SD) | 102 (16) | 93 (16) | 97 (16) | 107 (14) |

|

| ||||

| Male % (n) | 50 (5) | 63 (7) | 57 (12) | 55 (6) |

|

| ||||

| Race/Ethnicity % (n) | ||||

| Caucasian | 60 (6) | 55 (6) | 57 (12) | 82 (9) |

| African American | 30 (3) | 45 (5) | 38 (8) | 0 |

| Asian | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 (2) |

| Hispanic | 10 (1) | 0 | 5 (1) | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Maternal Education % (n) | ||||

| < HS Degree | 0 | 9.1 (1) | 4.8 (1) | 0 |

| HS Graduate/GED | 10.0 (1) | 27.3 (3) | 19.0 (4) | 0 |

| Some College | 41.0 (4) | 36.4 (4) | 38.1 (8) | 0 |

| College Graduate | 30.0 (3) | 18.2 (2) | 23.8 (5) | 18.2 (2) |

| Professional Degree | 20.0 (2) | 9.1 (1) | 14.3 (3) | 81.8 (9) |

Note. Vineland ABC is reported in age-based standard scores and has a mean = 100, SD = 15, with higher scores reflecting more intact functioning.

Based on one-way ANOVAs, no significant differences were found among the CKD and control groups in terms of chronological age, sex, or Vineland ABC score, suggesting that the CKD and control groups were similar in composition on these dimensions. Subsequently, these data were not covaried in the data analyses. The groups were significantly different on maternal education, in favor of the healthy controls, and this variable was adjusted in subsequent analyses.

CKD versus Controls - Accuracy and Reaction Time for Working Memory Task:

On the working memory task, participants completed four sets of presentations, resulting in 40 answers and associated reaction times. No significant differences in accuracy were found between the CKD patients and Controls (p = 0.17), nor were any differences in accuracy observed between the three groups (p = 0.19). Average reaction time was significantly faster for the control group compared with CKD patients (1725 ms vs. 2424 ms, p = 0.003). Further, control participants also responded more rapidly than either moderate or severe CKD groups, with the difference between controls and patients with severe CKD being more marked (p = 0.001). The two patient severity groups did not differ significantly from each other in terms of reaction time.

CKD versus Controls – fMRI Findings on Working Memory Task:

Encoding Period.

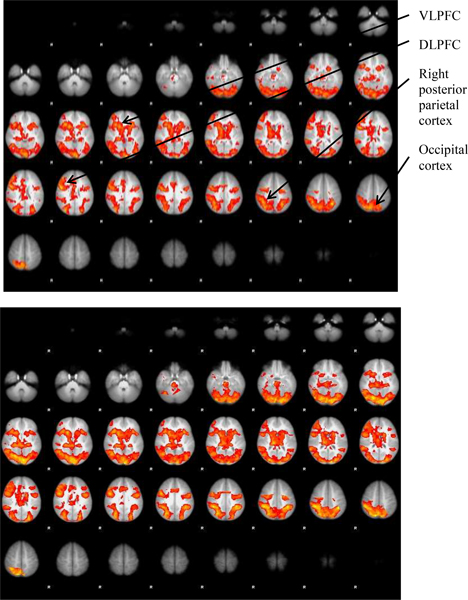

During the encoding period of the working memory task, both groups showed activation in brain areas associated with visuospatial working memory: the prefrontal cortex, premotor cortex, parietal regions, and occipital regions. Figure 1 illustrates significant activation, defined as BOLD signal change of z > 2.3 (p = 0.02), during the time periods representing the hemodynamic response to the object locations during the encoding period of the working memory task for both groups.

Figure 1.

Horizontal sections showing mean activation above z = 2.3 for control participants (above) and CKD patients (below) during the encoding phase.

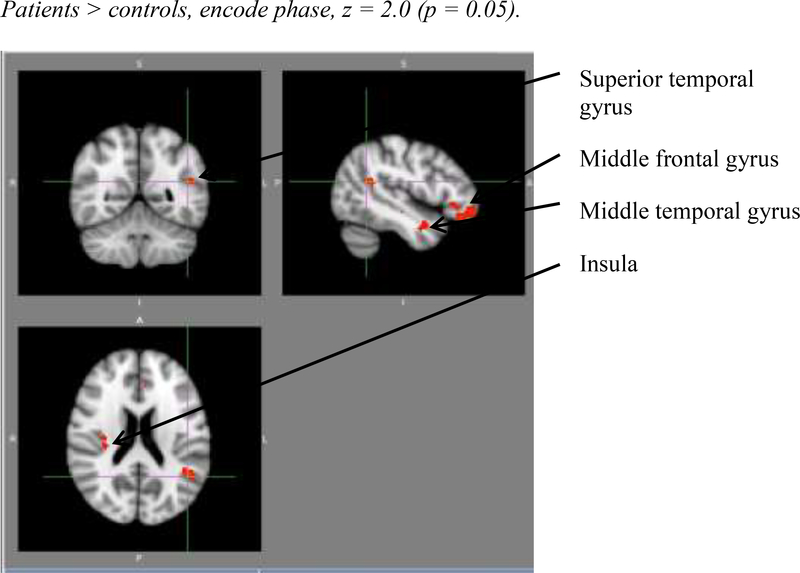

Despite the overall accuracy of the groups in performing the working memory task, Figures 2 and 3 show the comparative activation patterns for both groups during the encoding phase. In Figure 2, the control group showed significantly higher activation in the posterior cingulate, anterior cingulate, precuneus, and middle occipital gyrus than the CKD group. In contrast, Figure 3 illustrates where the CKD group had significantly more activation than controls; specifically, in the superior temporal gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, and the insula.

Figure 2.

Horizontal sections showing the comparative activation patterns for both groups during the encoding phase where Controls > CKD (encode phase, z = 2.0, p = 0.05).

Figure 3.

Horizontal sections showing the comparative activation patterns for both groups during the encoding phase where CKD > Controls (encode phase, z = 2.0, p < .05).

Additionally, over the time course of the encoding phase of the task, a significant difference between control participants and patients with CKD was found in the superior parietal lobule, bilaterally (p < 0.001) and in favor of controls, as illustrated in Figure 4. When the portions of the superior parietal lobule in the left and right hemispheres were considered separately, trends were evident toward lower mean percent signal change in the patients with CKD, but the difference was not interpreted as significant based on post-hoc tests. Figure 5 illustrates the mean percent signal change over time in the patient and control groups in the superior occipital gyrus. Mean percent signal change was higher among controls than patients in the encode phase (p = 0.03) and average percent signal change over the course of the task was higher for controls than for patients with CKD (p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Group comparisons of the time course of mean percent signal change in the superior parietal lobule during the encoding phase.

Figure 5.

Group comparisons of the time course of mean percent signal change in the superior occipital gyrus during the encoding phase.

Trends toward differences between the control participants and patients with CKD were found in other regions. Patients with CKD showed lower mean percent signal change during the encode phase in Brodmann Area 7 (p = 0.005), which is part of the posterior parietal cortex adjacent to the superior parietal lobule, suggesting that the difference in activation between groups extended from the superior parietal lobule to additional parietal regions. Patients with CKD also had lower peak percent signal change than control participants during the encode phase in the precentral gyrus (p = 0.03), superior occipital gyrus (p = 0.03), superior parietal lobule (p = 0.04), and Brodmann Area 7 (p = 0.03). None of these differences, however, survived comparison for multiple comparisons.

Secondary Analysis of Severity and Encoding: 3-Group Comparison.

The three-group comparisons revealed a number of significant differences. In the superior parietal lobule, patients with Severe CKD had significantly lower average percent signal change (p = 0.001) and peak signal change (p = 0.001) compared with controls. Patients with Moderate CKD also showed lower signal change than control participants in this region (p = 0.007 for average percent signal change, p = 0.02 for peak signal change). In the adjacent region, Brodmann Area 7, peak signal change was significantly lower among both patients with Severe CKD (p < 0.001) and Moderate (p < 0.001) CKD compared with control participants. Patients with Severe CKD also had lower peak signal change in the encode phase compared with control participants in the superior frontal gyrus (p = 0.03), middle frontal gyrus (p = 0.02), insula (p = 0.02), superior occipital gyrus (p = 0.02), angular gyrus (p < 0.01), and precentral gyrus (p < 0.01), but these differences did not retain significance once adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Retrieval Period.

During the retrieval phase, Figures 6 shows significant activation, defined as BOLD signal change of z > 2.3 (p = 0.02), during the time periods representing the hemodynamic response to the retrieval of object locations during the working memory task for both CKD patients and controls, and as with the encoding phase, the same brain regions are showing activity for the retrieval of task information.

Figure 6.

Horizontal sections showing mean activation above z = 2.3 for control participants (above) and CKD patients (below) during the retrieval phase.

Figures 7 and 8 show the comparative activation patterns for both groups during the retrieval phase. In Figure 7, the control group showed significantly higher activation during the retrieval phase than the CKD Group in the posterior cingulate, medial frontal gyrus, occipital lobe, and the middle temporal gyrus. In contrast, Figure 8 illustrates where the CKD Group had more activation than controls during the retrieval phase. Here, the CKD Group showed significantly more activation during the retrieval portion of working memory in one brain region—the postcentral gyrus.

Figure 7.

Horizontal sections showing the comparative activation patterns for both groups during the retrieval phase where Controls > CKD (retrieval phase, z = 2.0, p < .05).

Figure 8.

Horizontal sections showing the comparative activation patterns for both groups during the retrieval phase where CKD > controls (retrieval phase, z = 2.0, p < .05).

With respect to percent signal change over the time course of the task, no comparisons between patients and controls were deemed significant for the retrieval period. However, as in the encoding phase, patients with CKD displayed trends for lower average percent signal change than control participants in the superior parietal lobule (p = 0.009) and in Brodmann Area 7 (p = 0.004). Patients with CKD also had lower average percent signal change during the retrieval period in the lingual gyrus (p = 0.03), posterior cingulate (p = 0.02), and precuneus (p < 0.05)—all regions associated with visual-spatial processing and/or visual working memory. None of these findings survived correction for multiple comparisons.

Secondary Analysis of Severity and Retrieval: 3-Group Comparison.

The three-group comparisons revealed a number of significant differences between groups during the retrieval phase of the working memory task. Notably, patients with moderate CKD showed lower activation of left hemispheric frontal regions during the retrieval period. Patients with moderate CKD had lower average percent signal change compared with healthy controls in the left middle and medial frontal gyri (p = 0.04 for each) and the left posterior cingulate (p = 0.02), and they had lower average percent signal change than patients with severe CKD in the left superior (p < 0.01), middle (p < 0.01), and inferior (p = 0.03) frontal gyri. Patients with moderate CKD also had lower average percent signal change than patients with severe CKD in the right posterior cingulate (p = 0.03), signifying a nonsignificant trend toward lower activation in part of the attention system; however, none of these differences found in the retrieval period maintained significance once adjustments for multiple comparisons were asserted.

Discussion

Given the growing literature documenting neurocognitive difficulties experienced by children and adolescents with CKD, brain imaging studies provide an avenue to explore neurological mechanism(s) that may underly these difficulties. To date, a number of brain imaging studies have shown various structural abnormalities in this population, but the use of functional imaging studies with the CKD population remains nascent, with only two studies published to date.10–11 The collective findings from those two studies point to the Default Mode Network as different in CKD than in controls and perhaps contributing to the attention dysfunction that can be seen in pediatric CKD. This study expands this literature by using fMRI to study brain functions underlying working memory. This cross-sectional investigation was conducted to examine the activation patterns of relevant brain regions in children and adolescents with CKD when engaged in the encoding and retrieval periods of a visual-spatial working memory task when compared to healthy controls. In line with the hypotheses proposed for this study, several key findings emerged.

First, fMRI findings revealed that children and adolescents with CKD and healthy controls invoke the same functional brain regions during the task of working memory. This similarity was present on both the encoding and retrieval phases of the task, and was consistent with what has been documented in the literature with respect to the brain regions involved in working memory.13 In particular, during the encoding and retrieval components of working memory, both groups utilized functioning systems involving the prefrontal cortex, premotor cortex, parietal regions, and occipital regions. As such, it appears that children with CKD do not employ a different neural system for engaging in working memory than healthy controls.

Second, despite the observations that the CKD and controls performed similarly on their accuracy of the working memory task and that they engage the same functional brain system for working memory, there were significant group differences noted in the activation patterns for both components of the task. Specifically, for the encoding phase, the CKD group showed lower activation in the posterior cingulate, anterior cingulate, precuneus, and middle occipital gyrus than the control group. These areas have been associated with attention regulation and may provide clues as to the attentional slippages that have been reported in this population.1 In contrast, the CKD group demonstrated significantly more activation than controls in the superior temporal gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, and the insula, perhaps suggesting enlistment of additional brain regions to perform this type of cognitive task and, perhaps, general inefficiency in information processing

For the Retrieval phase of the working memory task a similar pattern was demonstrated, i.e., under activation for brain systems involving the posterior cingulate, medial frontal gyrus, occipital lobe, and the middle temporal gyrus. This is a wide-ranging network that likely reflects significant inefficiency in retrieving specific information following a disruption or delay. Further, the CKD group demonstrated more activation than the control group in solely the postcentral gyrus. This latter finding is curious in that this brain region is in the primary somatosensory cortex and primarily responsible for functions such as the location of touch on the body, changes in body temperature, voluntary movement of the hands, taste perceptions, and tongue movements. While this initial finding may simply reflect the individual’s ability to encode the location of an object, the over activation on the part of the CKD Group is noteworthy. It is likely that the association fibers that link this brain region to the parietal lobe have overstimulated or flooded this region in an effort to retrieve the necessary visual-spatial information (i.e., location of the object) to respond accurately to this task. One potential behavioral indicator may be the slower reaction time to produce a response in the CKD group.

Third, over the time course of the working memory task, other differences in blood flow were also apparent, particularly on the encoding phase of the working memory task. Here, specific differences between the CKD and control groups were apparent in a number of brain regions including the superior parietal lobe, the superior occipital gyrus, the precentral gyrus, superior occipital gyrus, superior parietal lobule, and Brodmann Area 7. Specifically, for the superior parietal lobe and the superior occipital gyrus, key areas for processing visual-spatial information, the percent signal change over time in these regions was higher among the control group than the CKD group indicating increased activity in these focused regions for the encoding portion of the working memory task. This was not the case for the CKD Group. For the precentral gyrus, superior occipital gyrus, superior parietal lobule, and Brodmann Area 7, the percent signal change over time was lower among the control group compared to the CKD Group. While these brain regions are important to visual working memory, and visual-spatial processing more generally, this implies less efficiency in the neural activation required for the initial encoding of information into short-term memory and potentially great difficulties in its retrieval at a later point in time.

In contrast, there were not many group differences uncovered for the retrieval component of working memory. While there were several trends for lower average percent signal change for the CKD Group as compared to the controls in the superior parietal lobe, Brodmann Area 7, lingual gyrus, posterior cingulate, and precuneus, brain regions that are important for visual processing, attention, and working memory, none of these differences survived the correction for multiple comparisons. In that regard, there were no differences between groups in the percent signal change over the time course of the task suggesting little in the way of different neural signatures for the retrieval component of working memory.

Finally, in an exploratory fashion, our functional imaging paradigm also examined group differences pertaining to CKD disease severity. While some differences were noted between the two severity groups versus the control group, there were no significant differences present between the two severity CKD groups on any of the measures on the encoding or retrieval components of the working memory task. Several trends were apparent between the mild-moderate versus the severe CKD groupings, including the expected lower average percent signal change for the severe CKD Group in the left superior, middle, and inferior frontal gyri, and right posterior cingulate when compared to the Mild-Moderate Group, but none survived correction for multiple comparisons. Although not significant after correction, the relatively lower blood flow to left frontal regions raises ongoing future research questions. For example, this finding could suggest preferential allocation of available resources (i.e., healthy oxygenated blood) to right hemispheric regions during retrieval of visual-spatial information, possibly representing relatively more efficient distribution of limited resources in patients with mild to moderate CKD than in patients with severe CKD. These general findings also have been seen in adults with ESKD not yet receiving dialysis,24 as well as in adults on hemodialysis, in whom a mild reduction in blood flow was noted following treatment.25 Further, similar brain activation patterns for working memory have been observed in adults at-risk for hypertension26 as well as adults with Type 1 Diabetes.27,28

From a mechanistic perspective, many of these fMRI findings on working memory, and the recognition of available structural MRI findings,6–8 can be linked to white matter integrity and dysfunction. For example, Klingberg and colleagues have accumulated evidence tying white matter maturation in certain regions with gray matter maturation in nearby regions and with improvements in working memory over the same age span.13,21–23 Increasing activation of frontal and intraparietal regions has been correlated with increasing working memory capacity in children and adolescents.21 Increasing activation in the superior frontal sulcus and inferior parietal lobe has been correlated with increasing myelination of nearby frontoparietal regions over the ages of 8 to 18 years.23 Over this same age span, development of working memory capacity has been positively associated with increasing myelination in the left frontal lobe, including a region between the superior frontal and parietal cortices.22 These studies indicate that improvements in working memory over the course childhood and adolescence are subserved by the simultaneous development of myelination and gray matter in a superior frontal-intraparietal network,13 and that such brain development may be impaired in children and adolescents with CKD, as possibly reflected in these preliminary fMRI findings. Additionally, while we could not analyze these findings, it was observed that more patients with CKD (3) than controls (1) were excluded from the analyses due to excessive head movement, a finding that might lend credence to the presence of subtle difficulties with attention regulation and restlessness—additional factors that could influence working memory functions as well. This observation should receive follow-up on subsequent investigations as the brain functioning of these subjects, if they could be accurately scanned, may contribute to even greater group differences than uncovered in this study.

This study provides initial preliminary findings on functional brain imaging for children and adolescents with CKD. As such, it is one of the first studies to use fMRI to examine the underlying brain functioning that accompanies complex cognitive functions, i.e., working memory. This study adds to the growing neuroimaging literature in pediatric CKD with findings generally showing that the underlying neurological systems contributing to a cognitive function like working memory may be significantly different from healthy controls and may contribute to differences if not deficits in cognitive functioning. While we believe that this work complements findings from structural brain imaging studies and extends emergent findings from the few functioning neuroimaging studies, this study has a number of limitations that require mention. First, the study is hampered by a small sample size which may have lessened the power to detect group differences across the various brain regions. This may be particularly true for those findings that were initially significant, but did not survive correction for multiple comparisons. Second, while we did control for a number of a priori variables (i.e., chronological age, sex) and by our exclusion criteria (e.g., seizures, traumatic brain injuries), pediatric CKD is quite complex, and a number of other factors could have affected the fMRI signal. For example, how did medication(s), presence of hypertension, anemia, proteinuria, or other factors (e.g., prematurity) affect the fMRI findings? We did attempt to address the issue of disease severity, although the plethora of concomitant issues tied to progressing illness (e.g., more medications) will be an ongoing challenge in such studies. Having a larger sample would permit a more thorough examination of the impact of these factors on fMRI signal, particularly with respect to exploring possible moderators and mediators. Third, the study is cross-sectional. It is unclear how fMRI patterns would change over time from a longitudinal perspective, particularly with some of the findings of both over activation and under-activation being uncovered between the CKD and control groups.

In summary, this study presents seminal findings pertaining to the underlying neural processes involved in working memory for children and adolescents with CKD. It is the first to use fMRI to study working memory in this population, and indeed demonstrated some significant group differences in the expected direction, e.g., less cognitive efficiency and less brain activation on the encoding and retrieval components of working memory, but the results are far from definitive. Indeed, although these primary findings shed light on the underlying neurological differences that might be contributing to the neurocognitive challenges that can be seen in pediatric CKD, they also need to be interpreted as preliminary. More data are needed to address these questions more fully. It also will be important for future studies to extend such questions to other neurocognitive functions (e.g., executive functions, attention, language). Additionally, further longitudinal research utilizing concurrent and targeted cognitive and neuroimaging evaluations is warranted to better understand the impact of CKD progression on brain development and neurocognitive outcomes. Additional neuroimaging studies will improve our understanding of the mechanisms underlying neurocognitive dysfunction in CKD and will permit evaluation of CKD treatments, including transplant, dialysis, and treatments for hypertension and acidosis, with regard to their effects on cognitive function.29

Acknowledgments

Financial Support for this Work: Publication of this article was supported, in part, by The Chronic Kidney Disease in Children prospective cohort study (CKiD) with clinical coordinating centers (Principal Investigators) at Children’s Mercy Hospital and the University of Missouri – Kansas City (Bradley Warady, MD) and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (Susan Furth, MD, PhD), central laboratory (Principal Investigator) at the Department of Pediatrics, University of Rochester Medical Center (George Schwartz, MD), and data coordinating center (Principal Investigator) at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (Alvaro Muñoz, PhD). The CKiD is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, with additional funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (U01 DK066143, U01 DK066174, U01 DK082194, U01 DK066116). The CKiD website is located at http://www.statepi.jhsph.edu. Additionally, the study primary data collection was supported in part by the Renal Research Institute.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure and Conflict of Interest Statements: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Waverly Harrell, School of Education, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

Debbie S. Gipson, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Nephrology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Aysenil Belger, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Mina Matsuda-Abedini, Division of Nephrology, The Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Bruce Bjornson, Division of Neurology, B.C. Children’s’ Hospital, Vancouver, BC Canada

Stephen R. Hooper, Department of Allied Health Sciences, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, NC, USA

References

- 1.Chen K, Didsbury M, van Zwieten A, Howell M, Kim S, Tong A, Howard K, Nassar N, Barton B, Lah S, Lorenzo J, Strippoli G, Palmer S, Teixeira-Pinto A, Mackie F, McTaggart S, Walker A, Kara T, Craig JC, Wong G. Neurocognitive and educational outcomes in children and adolescents with CKD. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018;13:387–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hooper SR, Gerson AC, Butler RW, Gipson DS, Mendley SR, Lande MB, Shinnar S, Wentz A, Matheson M, Cox C, Furth SL, Warady BA. Neurocognitive functioning of children and adolescents with mild-to-moderate chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;6:1824–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hooper SR, Gerson AC, Johnson RJ, Mendley SR, Shinnar S, Lande M, Matheson MB, Gipson D, Morgenstern B, Warady BA, Furth SL. Neurocognitive, social-behavioral, and adaptive functioning in preschool children with mild to moderate kidney disease. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2016;7:231–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hooper SR, Johnson RJ, Gerson AC, Lande MB, Shinnar S, Harshman LA, Kogon AJ, Matheson M, Bartosh S, Carlson J, Warady BA, Furth SL Overview of the findings and advances in the neurocognitive and psychosocial functioning of mild to moderate pediatric CKD: Perspectives from The Chronic Kidney Disease in Children (CKiD) Cohort Study. Ped Nephrol in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gipson DS, Hooper SR, Duquette PJ, Wetherington CE, Stellwagen KK, Jenkins TL, et al. Memory and executive functions in pediatric chronic kidney disease. Child Neuropsychology 2004;12:391–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moodalbail DG, Reiser KA, Detre JA, Schultz RT, Herrington JD, Davatzikos C, Doshi JJ, Erus G, Liu HS, Radcliffe J, Furth SL, Hooper SR. Systematic review of structural and functional neuroimaging findings in children and adults with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:1429–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuda-Abedini M, Fitzpatrick K, Harrell WR, Gipson DS, Hooper SR, Belger A, Poskitt K, Miller SP, Bjornson BH. Brain abnormalities in children and adolescents with chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Res. 2018;84(3):387–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartung EA, Erus G, Jawad AF, Laney N, Doshi JJ, Hooper SR, Radcliffe J, Davatzikos C, Furth SL. Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings in Children and Young Adults With CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;72(3):349–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon MA, van der Plas E, Langbehn KE, Novak M, Schultz JL, Koscik TR, Conrad AL, Brophy PD, Furth SL, Nopoulos PC, Harshman LA. Early pediatric chronic kidney disease is associated with brain volumetric gray matter abnormalities. Pediatr Res. 2021;89(3):526–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu HS, Hartung EA, Jawad AF, Ware JB, Laney N, Port AM, Gur RC, Hooper SR, Radcliffe J, Furth SL, Detre JA. Regional Cerebral Blood Flow in Children and Young Adults with Chronic Kidney Disease. Radiology. 2018;288(3):849–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrington JD, Hartung EA, Laney L, Hooper SR, Furth SL. Decreased neural connectivity in the default mode network among youth and young adults with Chronic Kidney Disease. Seminars in Nephrology, this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV, Balla DA. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (2nd ed.). 2005. San Antonio, TX: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klingberg T Development of a superior frontal-intraparietal network for visuo-spatial working memory. Neuropsychologia 2006;44:2171–7217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart SJ, Davenport ML, Hooper SR, Belger A. Visuospatial executive function in Turner syndrome: functional MRI and neurocognitive findings. Brain 2006;129:1125–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keator DB, Grethe JS, Marcus D, Ozyurt B, Gadde S, Murphy S, et al. (in press). A national human neuroimaging collaboratory enabled by the Biomedical Informatics Research Network (BIRN; ). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE J, Johansen-Berg H, et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 2004;23:208–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burgund ED, Kang HC, Kelly JE, Buckner RL, Snyder AZ, Petersen SE, Schlaggar BL. The feasibility of a common stereotactic space for children and adults in fMRI studies of development. Neuroimage 2002;17):184–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang HC, Burgund ED, Lugar HM, Petersen SE, Schlaggar BL. Comparison of functional activation foci in children and adults using a common stereotactic space. Neuroimage 2003;19:16–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage 2002;17:825–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz GJ, Work DF. Measurement and estimation of GFR in children and adolescents. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:1832–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klingberg T, Forssberg H, & Westerberg H Training of working memory in children with ADHD. J Clin Exp Neuropsychology 2002;24:781–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagy Z, Westerberg H, Klingberg T. Maturation of white matter is associated with the development of cognitive functions during childhood. J Cogn Neurosci 2004;16:1227–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olesen PJ, Nagy Z, Westerberg H, Klingberg T. Combined analysis of DTI and fMRI data reveals a joint maturation of white and grey matter in a fronto-parietal network. Brain research. Cognitive Brain Research 2003;18:48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen P, Hu R, Gao L, Wu B, Peng M, Jiang Q, Wu X, Xu H. Abnormal degree centrality in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients with cognitive impairment: a resting-state functional MRI study. Brain Imaging and Behavior 2020; 10.1007/s11682-020-00317-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tryc AB, Alwan G, Bokemeyer M, Goldbecker A, Hecker H, Haubitz M, Weissenborn K. Cerebral metabolic alterations and cognitive dysfunction in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011;26:2635–2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haley AP, Gunstad J, Cohen RA, et al. Neural correlates of visuospatial working memory in healthy young adults at risk for hypertension. Brain Imag Behav 2008;2:192–199. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geisa B Gallardo-Moreno, González-Garrido Andrés A., Gudayol-Ferré Esteban, Guàrdia-Olmos Joan. Type 1 diabetes modifies brain activation in young patients while performing visuospatial working memory tasks. J Diabetes Res 2015; 10.1155/2015/703512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Embury CM, Wiesman AI, Proskovec AL, Heinrichs-Graham E, McDermott TJ, Lord GH, Brau KL, Drincic AT, Desouza CV, Wilson TW. Altered brain dynamics in patients with Type 1 Diabetes during working memory processing. Diabetes 2018;67:1140–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harshman LA, Hooper SR. The brain in pediatric chronic kidney disease-the intersection of cognition, neuroimaging, and clinical biomarkers. Pediatr Nephrol 2020;35:2221–2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]