Abstract

The iron-containing Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) have attracted a great deal of attention in the areas of gas separation, catalytic conversion, and drug delivery, due to their high surface area and activity, as well as the non-toxicity of iron. In this study, Fe-based MOFs using BDC ligands, MIL-101(Fe), MIL-53(Fe) and Amino-MIL-101(Fe) are synthesized by a solvothermal method and characterized by conventional methods such as BET, SEM, and TGA. Afterwards, the synthesized MOFs are investigated from the point of view of the adsorbing capability of carbon dioxide at different pressures and temperatures, and also their resistance to water and solvent. The results showed that Amino-MIL-101(Fe) achieved more CO2 adsorption than MIL-101(Fe) and MIL-53(Fe), equal to 13 mmol g−1 at 4 MP. Although MIL-53(Fe) has the best temperature resistance, around 350 °C, Amino-MIL-101(Fe) is more stable against water and ethanol and its surface area is increased from 670 to 915 m2 g−1 after washing with ethanol. The adsorption study reveals that CO2 is adsorbed not only by a physical adsorption mechanism, but also by chemisorption of acidic carbon dioxide by basic NH2 agent in the structure of Amino-MIL-101(Fe).

The adsorption isotherm of MIL-101(Fe)-NH2 was independent of temperature and the heat of adsorption was considered equal to the activation energy of CO2 chemisorption by NH2 agent.

Introduction

In order to optimize energy consumption, adsorbing and separating CO2 using solid porous adsorbents has attracted a great deal of attention. For this purpose, zeolites, activated carbons, silicates, and MOFs have been investigated, which has led to the use of some of these adsorbents, especially zeolites, in industry. Meanwhile, MOFs with high porosity and adsorption capacity have appeared as one of the distinct candidates, and they have been used as adsorbents for various gas systems, including CO2. Therefore, the development of MOF adsorbents with high CO2 adsorption capacity is strongly required.1,2 If the heat of adsorption is very high, like for zeolites, or an energetic chemical reaction occurs between the parts of the MOF ligands, the unsaturated coordinator, or an open metal site and CO2, the CO2 release and recovery are difficult or even impossible in some cases. In the case of the moderate heat of adsorption and greater sensitivity to pressure variations, MOFs can be suggested as a good option for use in PSA processes.3 The MOFs that have attracted the most attention during the past decade include Cu-BTC (HKUST-1), MIL-100, MIL-101, MIL-53, MOF-74/CPO-27, UiO-66, and ZIF-8.4

Due to the presence of water vapor in the outlet gas from the chimney and in the natural gas stream in sweetening processes, one of the important criteria which has to be considered in choosing the appropriate MOF to adsorb CO2 is its water resistance. From the standpoint of water resistance, MOFs can be divided into four categories:4

Thermodynamically stable: stability after prolonged exposure to aqueous solution.

High kinetic stability: stability after being exposed to high humidity.

Low kinetic stability: stability after exposure to low humidity.

Unstable: quickly exposed to any moisture.

Although many of the early developed MOF adsorbents have been capable to adsorb very high amounts of CO2, the later studies have shown that their water resistance is very low and exposed to damage of the structure. At first view, for example, Mg-MOF-74 from the MOF-74 series (CPO-27) with CO2 adsorption up to 120 ml g−1 (about 3.5 mmol g−1) at a low pressure of 0.1 atm is the best choice for adsorbing CO2, and has been focused by scientific researchers for several years.5,6 Despite all these positive characteristics, according to the later studies, it is found out that the Mg-MOF-74 would lose much of its surface area (BET) when it is exposed to moisture. Furthermore, PXRD results indicate a deterioration of adsorbent structure after exposure to moisture. Other MOFs including MOF-5 (IRMOF-1), Cu-BTC (HKUST-1), MOF-199, MOF-14, MOF-177, MOF-505, MOF-508, etc. have also been found that they are unstable, and their structure is damaged when exposed to water. Hence, it is necessary to propose ways to improve the stability of MOFs against water for CO2 adsorption purposes.4,7–9

Adsorption of gas by porous materials is usually accomplished by: (a) differences in size and/or shape known as molecular sieve effect or esteric separation; (b) because of the differences in the interactions between the adsorbate molecule and the adsorbent surface, known as the thermodynamic equilibrium effect; (c) because of the different diffusion intensity known as the kinetic effect or partial molecular sieve action, and (d) because of the quantum effect.

While esteric separation is common in zeolites and molecular sieves, when the adsorbent pore size is large enough to allow all gas components to pass through, the interaction between the adsorbate and the adsorbent surface will be significant in determining the adsorption quantity of each component. Furthermore, the interaction strength is determined by the adsorbent surface specifications and the properties of the adsorbate, including polarizability, magnetic susceptibility, permanent dipole moment, quadrupole moment, etc.10

According to previous studies, the use of carboxylate ligands such as 1,4-benzenedicarboxylates, BDC, with high-valence metal cations such as Zr4+, Cr3+, Al3+, Fe3+, etc., improve water-resistant of MOFs.11 On the other hand, strong polarizing groups such as carboxylic acid plays an important role in adsorbing CO2, which poses a quadrupole moment. Moreover, the higher valence of the metals mentioned above leads to an increase in the electrical difference between the adsorbent surface and the CO2 molecule and consequently more CO2 adsorption. For CO2 adsorption, the pore diameter of sorbent must be larger than kinetic diameter of CO2 molecule, i.e. 3.3 Å. The CO2 gas is adsorbed due to the difference in interactions between the adsorbate and the adsorbent surfaces; and therefore, as described above, the mechanism of adsorption is thermodynamic equilibrium.10

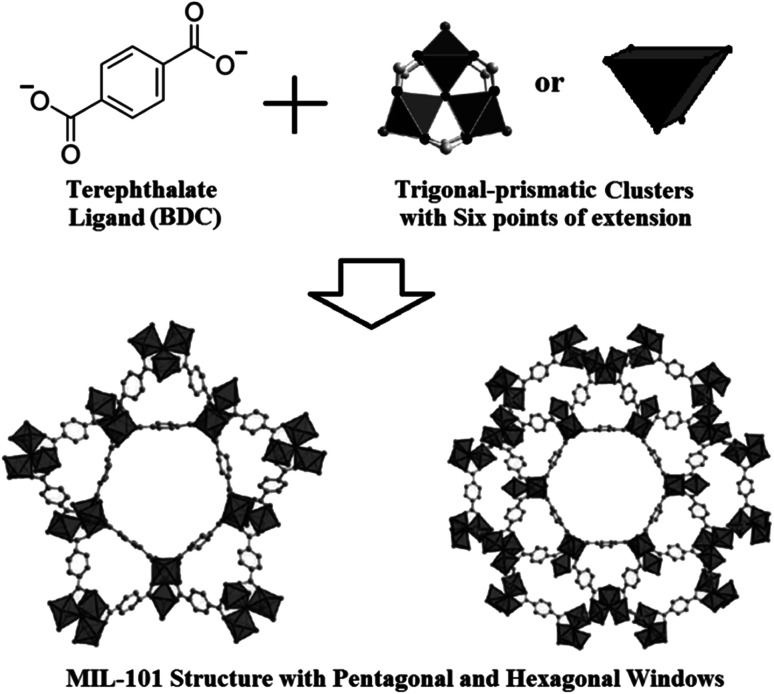

MIL-101(Cr) firstly presented by Material Institute Lavoisier (MIL), is constructed from trigonal-prismatic chromium clusters {Cr3(O)(F)(H2O)2} as a Secondary Building Units (SBUs) with six points of extension and 1,4-benzenedicarboxylates (BDC) organic ligand resulting in a highly porous 3-dimensional structure with two domains of pore sizes, i.e. 18 and 23 Å attributed to two pentagonal and hexagonal windows in the structure (Fig. 1).12,13 MIL-101(Cr) with high BET surface area reported between 2500–4200 m2 g−1 can adsorb 15–20 mmol g−1 of CO2 at ambient temperature and 2 MPa.14–16 As mentioned above, MIL-101(Cr) due to using high-valence metal cation Cr3+ and carboxylate ligand in its structure achieves an excellent resistance against water and can be categorized in the thermodynamically stable MOFs group.4,12,16 Although early studies which have been carried out by Ferey17 has reported that MIL-101 can only be obtained with Cr3+ ions, the synthesis method of MIL-101(Fe) has been presented in the later researches too.18–20

Fig. 1. MIL-101 structure constructed from its preliminary building units including terephthalate ligand and trigonal-prismatic metal clusters.12.

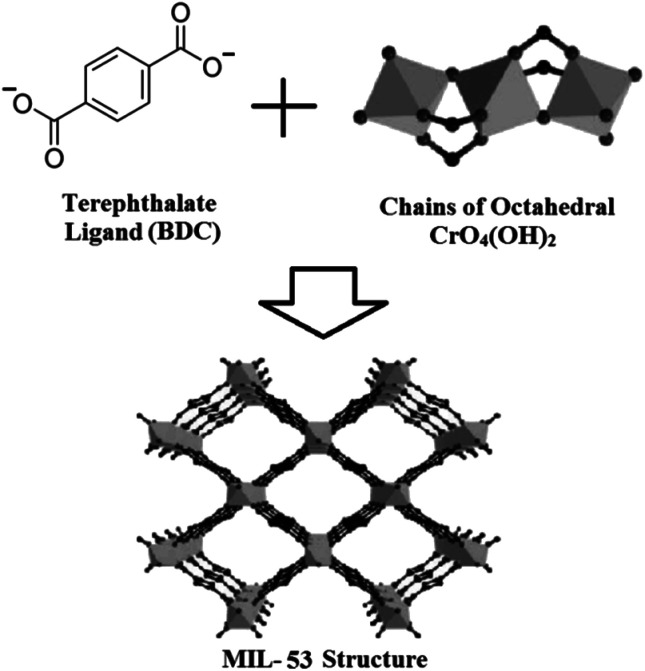

MIL-53(Cr) is another MOF from MIL family constructed from a connection of infinite chains of octahedral CrO4(OH)2 with organic linker BDC which poses a flexible structure with a pore diameter of 4 to 8.5 Å (Fig. 2).21 MIL-53 synthesized by Cr and Al as metal center are capable to adsorb 8 and 10 mmol g−1 of CO2 gas at ambient temperature and 2 MPa, respectively.22,23 Moreover, MIL-53(Cr) as well as MIL-53(Al) are stable after being exposed to high humidity and can be considered in the high kinetic stability group.4 Furthermore, the reported BET surface areas for MIL-53(Cr) and MIL-53(Al) are equal to 1337 and 1284 m2 g−1, respectively.24,25

Fig. 2. MIL-53 structure constructed from its preliminary building units including terephthalate ligand and octahedral CrO4(OH)2 chains.21.

Chemical modification of high surface area solids by forming covalent bonds or weaker van der Waals and hydrogen bonds between the adsorbent and the two major organic (such as amines) and inorganic groups (such as alkali or alkaline earth metal oxides) can improve the adsorption and selectivity of CO2 by solid adsorbents.26 There are two general strategies for improving adsorbent performance in CO2 adsorption:27

Prefunctionalization (also called direct modification or in situ synthesis).

Postsynthetic modification (PSM).

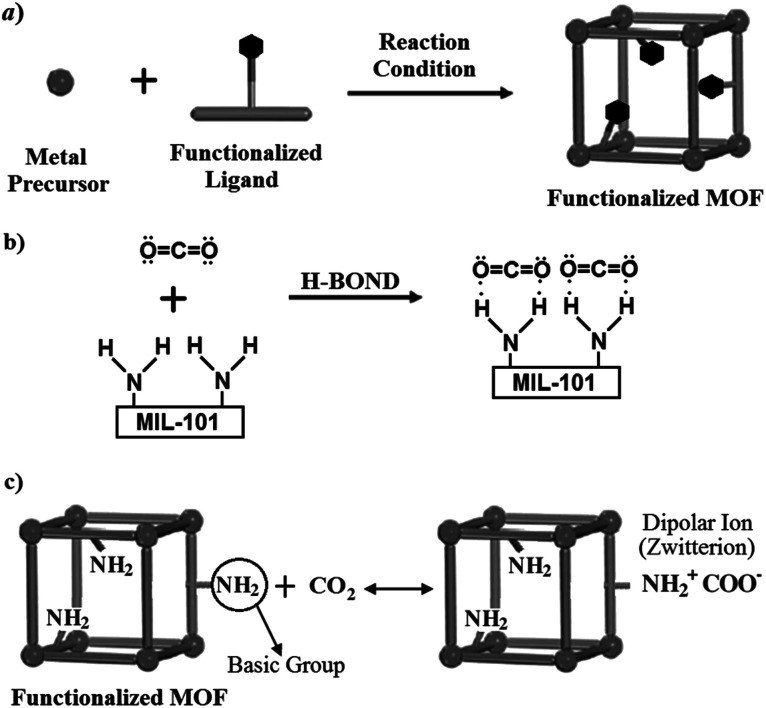

In the prefunctionalization method, schematically shown in Fig. 3(a), a ligand or organic linker already having the desired functional group is used to form the adsorbent. Using this method, adsorbents with different functional groups such as –NH2, –CH3, –Br and other relatively simple groups have been fabricated.27 Amino-MIL-101(Cr) (MIL-101-NH2) has a similar structure to MIL-101(Cr), which has been prefunctionalized by amino group. The charge difference between the metal cation and the organic anion in the MOF will give rise to an electric field. The interaction between the electric field of MOF and the quadrupole moment of CO2 causes the adsorption of CO2 by the MOF surface. In addition to the above-mentioned mechanism, hydrogen bonding is another mechanism in CO2 adsorption. Similarly, as shown in Fig. 3(b), the oxygen electron pair in the CO2 molecule can form a hydrogen bonding with hydrogen atoms in –NH2 functional group.28 Furthermore, NH2 is a basic group and can form a dipolar ion (zwitterion) in the vicinity of acidic CO2 molecules (see Fig. 3(c)).29

Fig. 3. (a) Schematic shape of prefunctionalization (direct modification or in situ synthesis) method;27 (b) hydrogen bonding between CO2 molecule and –NH2 functional group;28 (c) dipolar ion (zwitterion) formation by the acidic CO2 and basic NH2 groups.29.

BET surface area for MIL-101(Cr)–NH2 is equal to 1675 m2 g−1 which is smaller than that of unfunctionalized MIL-101(Cr) due to the occupation of the framework pores by amino groups. The amount of CO2 adsorption for MIL-101(Cr)–NH2 is reported equal to 12 mmol g−1 at ambient temperature and 2 MPa, which this value is smaller than previously mentioned value for unfunctionalized MIL-101(Cr), i.e. 15–20 mmol g−1. Therefore, although functionalizing the MOF by amino agent can improve the CO2 adsorption by mechanisms such as formation of hydrogen bond and dipolar ionic reaction, it can simultaneously can decrease CO2 adsorption capacity in MIL-101(Cr)–NH2 because of pores occupation by amino groups.30 It is reported that MIL-101(Al)–NH2 poses higher surface area and CO2 adsorption capacity in comparison to MIL-101(Cr)–NH2. MIL-101(Al)–NH2 with BET surface area equal to 2100 m2 g−1 is capable to adsorb about 14 mmol g−1 of CO2 at ambient temperature and 2 MPa.31

Although MOFs constructed from Cr and Al as metal center and BDC ligand have been considered and investigated in many studies, less attention has been paid to MILs synthesized using Ferrite precursors and BDC ligand, especially in terms of CO2 adsorption.26–41 It is known that the metal type will have a significant effect on the electric field intensity and consequently, CO2 adsorption. Similar to Cr3+ and Al3+ which are effective on resistance of MOF against water, Fe3+ as a high-valence metal cation is expected to give the same result when it is applied as the metal center in the MOF structure. Furthermore, one of the most important purposes of research on the development of MOFs is their industrial applications. Therefore, using nontoxic metal ions is of great interest. While chromium is strongly toxic and harmful environmentally, iron is a nontoxic and non-harmful metal. Therefore, Fe-BDC MOFs including MIL-101(Fe), MIL-53(Fe) and Amino-MIL-101(Fe) are considered in the current study. They have been synthesized solvothermally and characterized by PXRD, TGA, and SEM methods. Afterwards, the results of CO2 adsorption have been presented as isotherm diagrams in a wide range of pressures. The adsorption tests have been performed in three temperatures, 18, 25 and 30 °C, to predict the heat of adsorption for each of these MOFs. Moreover, the resistance of synthesized sorbents have been investigated against water and ethanol.

Experimental section

MIL-101(Fe) has been prepared as described by Taylor-Pashow et al.18 with some modifications. Afterwards, 2703 mg of hexahydrated iron chloride (FeCl3·6H2O) and 831 mg of terephthalic acid (H2BDC) have been added and dissolved in 60 ml of N,N′-dimethylformamide (DMF) with a molar ratio of 2 : 1 : 667 under sonication and stirring for minimum 30 min. The resulting clear solution has then been heated at 110 °C for 24 h in a Teflon-lined stainless steel bomb. The resulting product has been filtered and dried at room temperature during the night to achieve an orange colored fine powder.

MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 has been synthesized according to the method presented by Ferey et al.17 with some modifications. 2703 mg of FeCl3·6H2O and 906 mg of H2BDC-NH2 (Amino-BDC) have been dissolved in 60 ml of DMF with a molar ratio of 2 : 1 : 667 for 30 min and then heated at 110 °C for 24 h in a Teflon-lined stainless steel bomb. The resulting dark brown fine powder obtained after filtration has been dried at room temperature during the night, and then it was washed two times for 3 h in 60 °C pure ethanol to remove impurities including remaining Amino-BDC crystals.

MIL-53(Fe) has been synthesized as described by Ferey et al.42 a mixture of 2703 mg of FeCl3·6H2O and 1661 mg of H2BDC has been dissolved in 51 ml of DMF with a molar ratio of 1 : 1 : 280 for 30 min and then heated at 150 °C for 15 h in a Teflon-lined stainless steel bomb. The fine yellow powder obtained by filtration has been dried at room temperature during night.

Characterization

The resulting Fe-BDC materials have been characterized with powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) method.43 PXRD has been obtained by using a Low Angle X-ray Diffraction Machine SAXS Model X'Pert PRO MPD PANalytical, Netherlands. The standard Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method has been applied for the calculation of the surface area.44 The total pore volume has been calculated from the amount of adsorbed N2 at P/P0 = 0.99. BET surface area, pore volume and medium pore size of the synthesized Fe-BDC materials have been determined by N2 physisorption at 77 K using Micromeritics ASAP 3020 automated system. Thermogravimetry Analysis (TGA) data have been obtained by using a TGA instrument, Mettler, Swiss. For this purpose, samples have been heated at a rate of 10 °C min−1 from 25 to 700 °C under purging by nitrogen gas stream. The morphological structure of the adsorbents has been obtained by using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM; TESCAN, Mira III) operated at 15.00 kV.

Adsorption isotherms

For determining the adsorption isotherms, the volumetric method is considered. In this method, after purging the system by a vacuum pump, the system is filled by the high purity adsorbate gas up to a certain pressure and then, the valve of adsorption chamber will be opened. As the gas adsorbs, the pressure of the adsorption chamber gradually decreases. By measuring and recording this pressure loss over time, the rate of the gas adsorption at equilibrium pressure can be calculated using an appropriate thermodynamic model.45

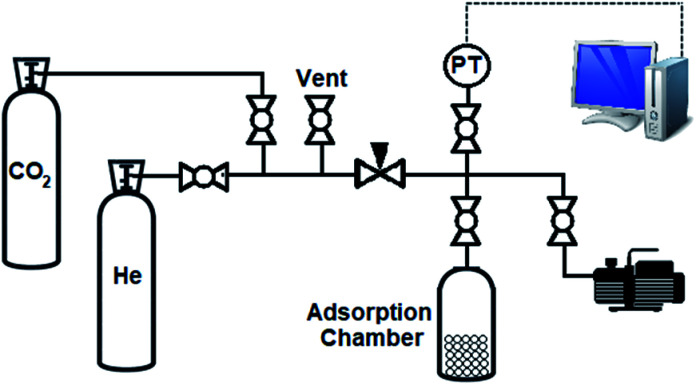

The schematic diagram of the CO2 adsorption test setup is shown in Fig. 4. The setup consists of a CO2 and He cylindrical gas chambers connected to the setup by the relevant valves. A regulating valve is used for fine controlling and adjusting the pressure. The pressure of CO2 gas is measured and transmitted to a PC by means of a pressure transmitter (PT). The trend of pressure changes with time is recorded in this PC using a data acquisition system. The volume of each part of the setup is determined by an individual apparatus. Because of decreasing the volume of adsorption chamber after inserting the adsorbent materials, the dead volume is estimated using helium gas. In addition to the adsorption capacity, adsorption isotherm of an adsorbent for a certain adsorbate gas can be determined using this setup. Before starting each adsorption test, the samples are activated by heating the samples for 3 h under high vacuum level.

Fig. 4. Schematic diagram of CO2 adsorption test setup.

Adsorption isotherms describe the relationship between the amount of adsorbed component on the adsorbent and the remaining material concentration. Several equations have been presented to fit and model the experimental adsorption data. Some of these equations such as Freundlich,46 Langmuir,47 and Tempkin48 equations have two parameters and the others Sips,49 Redlich–Peterson,50 and Toth51 equations have three parameters. Therefore, for fitting the data resulted in this study, a two-parameter model and a three-parameter model have been investigated.

Results and discussion

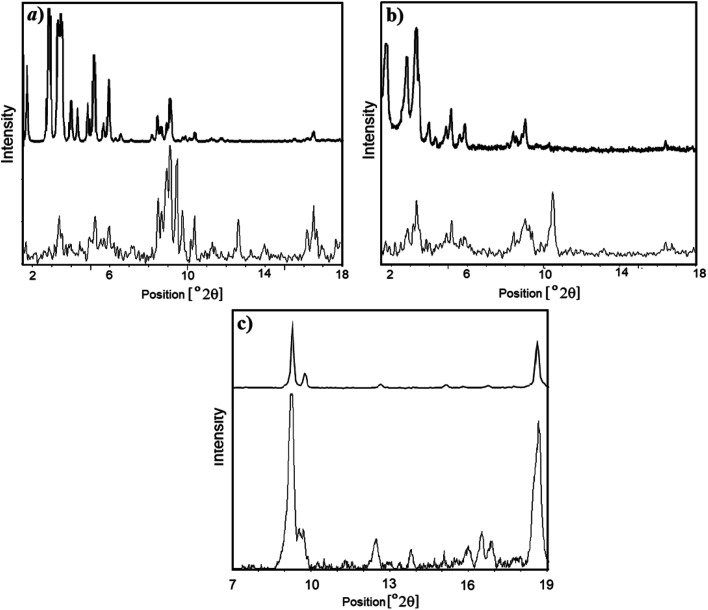

As presented in Fig. 5(a), XRD patterns of MIL-101(Fe) has a good agreement with Ferey et al. data.17 Furthermore, XRD patterns of Synthesized MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 and MIL-53(Fe) materials are in accordance with the literature,17,52 as seen in Fig. 5(b) and (c).

Fig. 5. (a) Powder XRD pattern of (a) synthesized MIL-101(Fe) (bottom) and MIL-101(Cr) synthesized by Ferey et al. (top);17 (b) synthesized MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 (bottom) and MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 synthesized by Ferey et al. (top);17 (c) synthesized MIL-53(Fe) (bottom) and MIL-53(Fe) synthesized by Ferey et al. (top).52.

As indicated in Table 1, the achieved BET surface area for synthesized MIL-101(Fe) is equal to 125 m2 g−1. The pore volume and medium pore size of MIL-101(Fe) have been equal to 0.05 cm3 g−1 and 17 Å respectively. Furthermore, average crystal size for this sample has been estimated equal to 500 Å by BET method. BET surface area for as-synthesized MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 has been equal to 670 m2 g−1. As described above, the BET surface area of MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 enhanced up to 915 m2 g−1 by washing in hot ethanol (60 °C, 3 h, 2 times). The pore volume and medium pore size of MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 have been equal to 0.4 cm3 g−1 and 24 Å respectively. The average crystal size for this sample has been estimated equal to 65 Å by BET method. Moreover, BET surface area for MIL-53(Fe) has been equal to 25 m2 g−1. The pore volume, medium pore size, and the average crystal size of MIL-53(Fe) have been equal to 0.01 cm3 g−1, 17 Å and 2400 Å respectively.

The morphology characteristics of synthesized Fe-BDCs achieved by BET method.

| BET surface area, m2 g−1 | Pore volume, cm3 g−1 | Medium pore size, Å | Average crystal size, Å | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIL-101(Fe) | 125 | 0.05 | 17 | 500 |

| MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 | 915 | 0.4 | 24 | 65 |

| MIL-53(Fe) | 25 | 0.01 | 17 | 2400 |

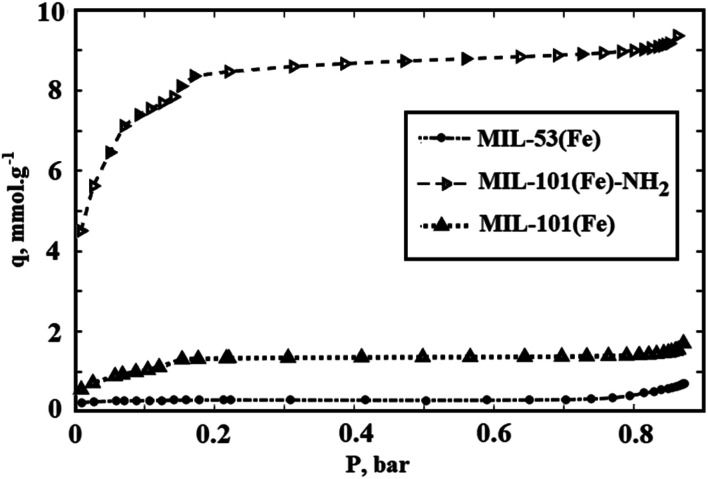

Contrary to the achieved values of pore diameters, for MIL-101(Fe) and MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 which correspond to the values predicted by the simulation (18 to 23 Å), the diameter obtained for MIL-53(Fe) does not correspond to the actual reported values. The low value surface area estimated by BET method for MIL-53(Fe) can be attributed to its small pore diameter (4 to 8.5 Å) which is close to the nitrogen molecular diameter (3.6 Å) and prevents the nitrogen molecules from passing through the MIL-53 micropores.53 The same reason can explain the inconsistency between the predicted and actual pore diameter of MIL-53(Fe). The resulted nitrogen adsorption isotherms at 77 K for MIL-101(Fe), MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 and MIL-53(Fe) are presented in Fig. 6. The amount of nitrogen adsorption by MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 is considerably more than the adsorbed nitrogen by two other MOFs at 77 K. The achieved nitrogen isotherms can be considered as type-I according to the IUPAC classification.54

Fig. 6. Nitrogen adsorption isotherms at 77 K for MIL-101(Fe), MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 and MIL-53(Fe).

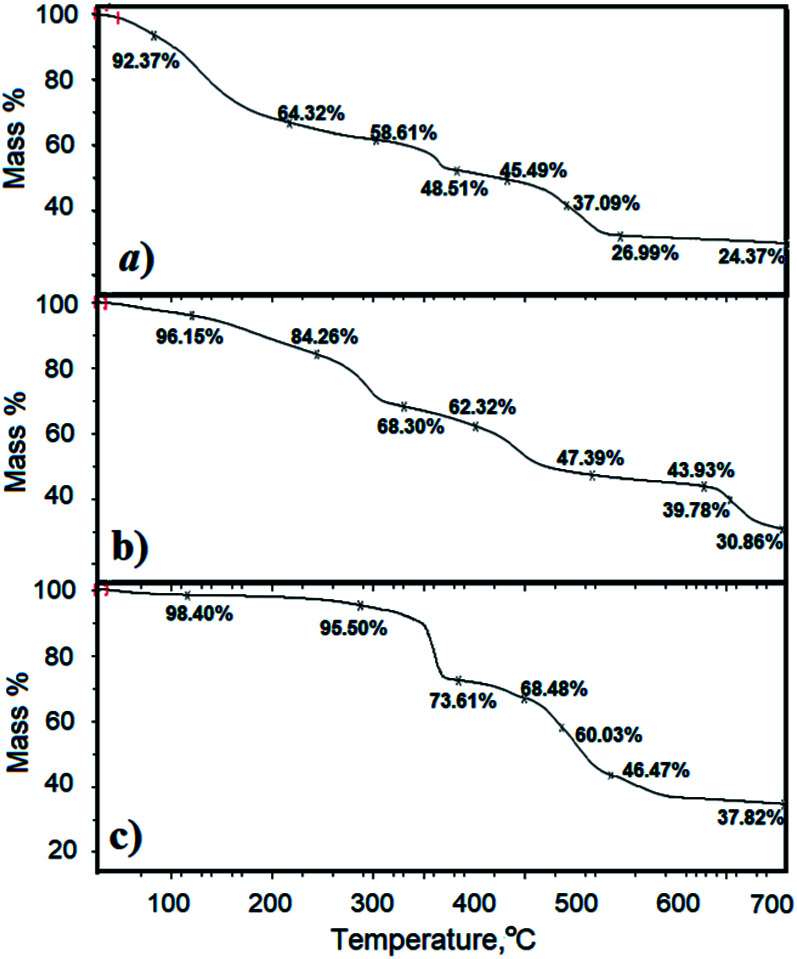

TGA curves for MIL-101(Fe), MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 and MIL-53(Fe) are presented in Fig. 7(a)–(c) respectively. As indicated in this figure, MIL-101(Fe) is unstable after about 100 °C. MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 is a bit more stable and is stable up to about 120 °C. Conversely, adsorbent MIL-53(Fe) in comparison with the other two adsorbents is more thermally stable, and it is stable up to 300 °C.

Fig. 7. GTA curves for (a) MIL-101(Fe); (b) MIL-101(Fe)–NH2; (c) MIL-53(Fe).

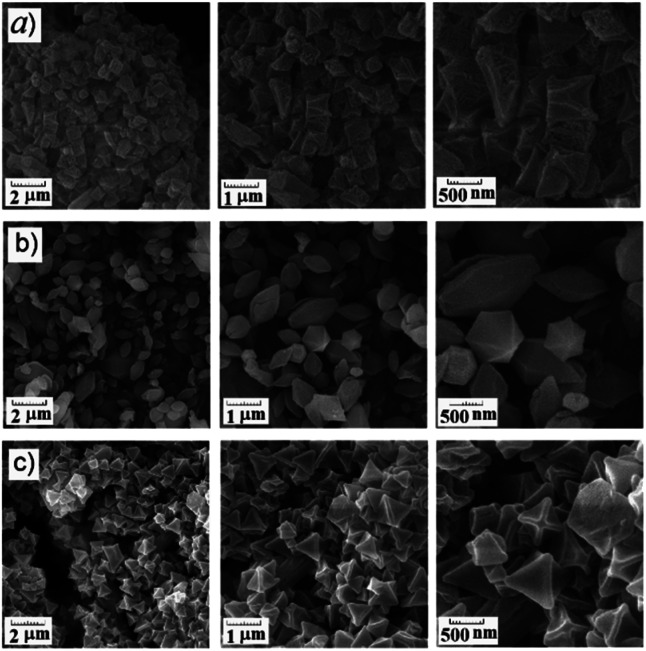

FESEM results at scales of 2 μm, 1 μm and 500 nm for MIL-101(Fe), MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 and MIL-53(Fe) are presented in Fig. 8(a)–(c) respectively. As shown in this figure, the crystals of MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 particles are much more obvious than two other sorbents, i.e. MIL-101(Fe) and MIL-53(Fe). The FESEM result for MIL-101(Fe) shows more agglomeration of crystal particles.

Fig. 8. FESEM results at scales of 2 μm (left side), 1 μm (middle) and 500 nm (right side) for (a) MIL-101(Fe); (b) MIL-101(Fe)–NH2; (c) MIL-53(Fe).

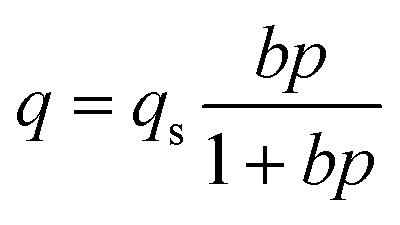

The experimental isotherms of carbon dioxide achieved in this study are fitted to two well-known isotherm models including:

Two-parameter Langmuir adsorption isotherm model47

|

1 |

in which, P is gas pressure at equilibrium condition with adsorbed phase (bar), q stands for the adsorption amount per mass of adsorbent (mmol g−1), qs is the maximum capacity of adsorbent (mmol g−1), and b is the affinity coefficient (bar−1). qs and b are parameters of the Langmuir isotherm equation and presented in Table 2 for experimental adsorption data of each synthesized MOF, i.e. MIL-101(Fe), MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 and MIL-53(Fe). As illustrated in Fig. 9, CO2 adsorption isotherm for MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 has an inflection point in pressure around 15 bar. Therefore, two different fittings are applied for achieving more accurate results including model (A) referring to pressures below 15 bar and model (B) referring to pressures more than 15 bar.

Parameters of Langmuir and Redlich–Peterson isotherm models used to fit and model the experimental adsorption data of synthesized MOFs.

| Langmuir model | Redlich–Peterson | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | q s | R 2 | c | q m | n | R 2 | |

| MIL-101(Fe) | 0.01170 | 28.92 | 0.995 | 25 950 | 0.5169 | 0.2167 | 0.998 |

| MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 (A) | 0.10430 | 7.337 | 0.972 | 20 500 | 0.9493 | 0.4181 | 0.995 |

| MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 (B) | 0.00007 | 4711 | 0.986 | 82 590 | 0.1695 | −0.1726 | 0.990 |

| MIL-53(Fe) | 0.00530 | 49.88 | 0.979 | 33 820 | 0.4416 | 0.1962 | 0.975 |

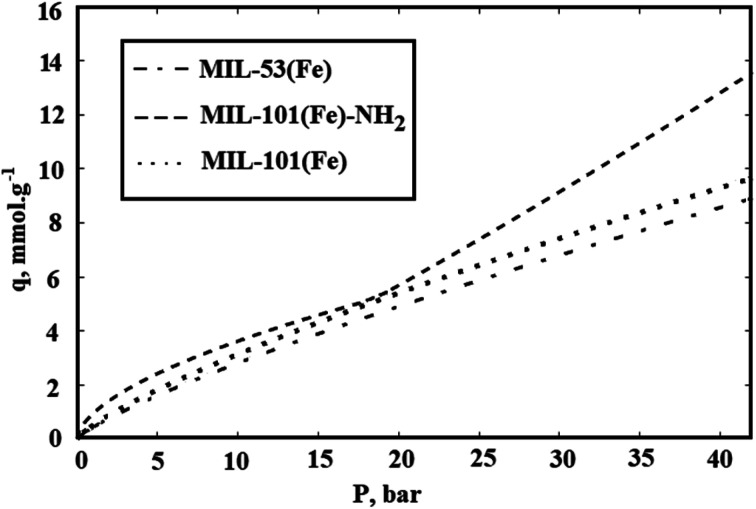

Fig. 9. CO2 adsorption isotherms for synthesized MIL-101(Fe), MIL-101(Fe)–NH2, and MIL-53(Fe).

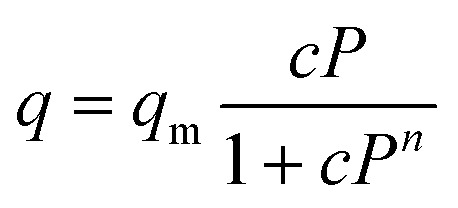

Three-parameter Redlich–Peterson (R–P) model50

|

2 |

where n is the dimensionless adsorbent parameter. qm and c are also parameters of the R–P isotherm model which are presented in Table 2 for each adsorbent in this study. Regarding to the reported R-squared in Table 2, the CO2 adsorption data fitted by Redlich–Peterson model are more precise rather than Langmuir isotherm model, unless for MIL-53(Fe) in which Langmuir model has shown better fitness. Other mentioned isotherm models are resulted in less accurate data or they are not applicable for these set of data.

In Fig. 9, the CO2 adsorption isotherms for synthesized Fe-BDCs, i.e. MIL-101(Fe), MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 and MIL-53(Fe) in 25 °C which are resulted by using R–P model are shown. As presented in Fig. 9, the maximum CO2 adsorption amount in 25 °C by MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 is about 13 mmol g−1 at 4 MP. Moreover, the amount of CO2 adsorption by MIL-101(Fe) and MIL-53(Fe) are equal to 9.3 and 8.6 mmol g−1 respectively.

As mentioned before, the surface area and the amount of CO2 adsorption by MIL-101(Cr) which is synthesized by chromium precursor is more than the surface area and CO2 adsorption capacity by functionalized MIL-101(Cr)–NH2. In addition, lower surface area for Amino-MIL-101(Cr) rather than MIL-101(Cr) has been attributed to the occupation of pores by NH2 agent.55,56 But the achieved results in this report show that the functionalized MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 synthesized by iron precursor can adsorb more CO2 rather than unfunctionalized MIL-101(Fe).

The synthesis of MIL-101(Fe) is kinetically, and the formation and growth of its structure is more difficult rather than Cr-based one. Therefore, it was previously reported that it is not possible to synthesize this MOF.17,31 From this point of view, the resulted MIL-101(Fe) has lower crystallinity and thermal and chemical stability. Furthermore, no further processing is performed for solvent and non-reacted precursors' extraction on MIL-101(Fe). Therefore, contrary to the Cr-based MIL, MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 adsorbed more CO2 rather than MIL-101(Fe).

On the other hand, the amount of CO2 adsorption by MIL-53(Fe) is less than two other synthesized Fe-BDCs which can be raised from its lower surface area rather than MIL-101(Fe) and MIL-101(Fe)–NH2. Although the reported BET surface area of MIL-53(Fe) is about 20 percent of surface area of MIL-101(Fe) and 3 percent of MIL-101(Fe)–NH2, its CO2 adsorption is not considerably lower than the adsorption by MIL-101(Fe) and MIL-101(Fe)–NH2. This disagreement between CO2 adsorption and surface area data can be attributed to the unconfident surface area data determined using N2.

As described before, increasing the interaction between the electric field of MOF and the quadrupole moment of CO2 by NH2 functional group and furthermore, the hydrogen bonding are the reasons of the higher CO2 adsorption by MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 rather than MIL-101(Fe). In addition to these mechanism, chemical reaction between amine group and CO2 molecules can affect the adsorption of CO2 MIL-101(Fe)–NH2, especially in the higher pressures and the inflection point in the CO2 isotherm of MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 can be referred to chemisorption mechanism.

For investigation of the stability of the samples during the process of CO2 adsorption, the performance of CO2 adsorption was tested after five adsorption cycles for three synthesized adsorbents, i.e. MIL-101(Fe) and MIL-101(Fe)–NH2, and MIL-53(Fe). No significant loss in the CO2 adsorption capacity was observed after each adsorption test which revealed the stability of Fe-BDCs during the process of CO2 adsorption.

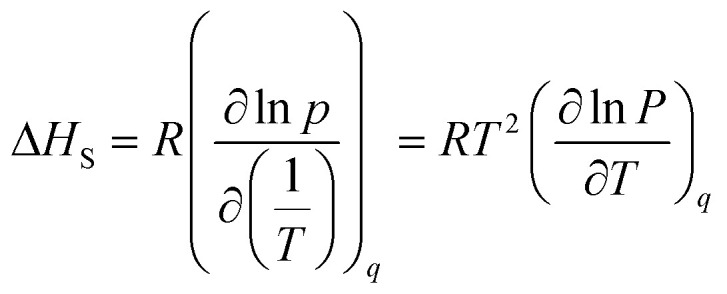

Heat of adsorption

The heat of adsorption indicates the strength of the interaction between the adsorbate molecules and the adsorbent surface. This parameter can be estimated by determining the gas adsorption at different temperatures called isosteric heat of adsorption.57,58 Isosteric heat (ΔHS) has been obtained by differentiating an adsorption isotherm at a constant adsorbate loading, q, which is similar to the well-known Clausius–Clapeyron equation:59,60

|

3 |

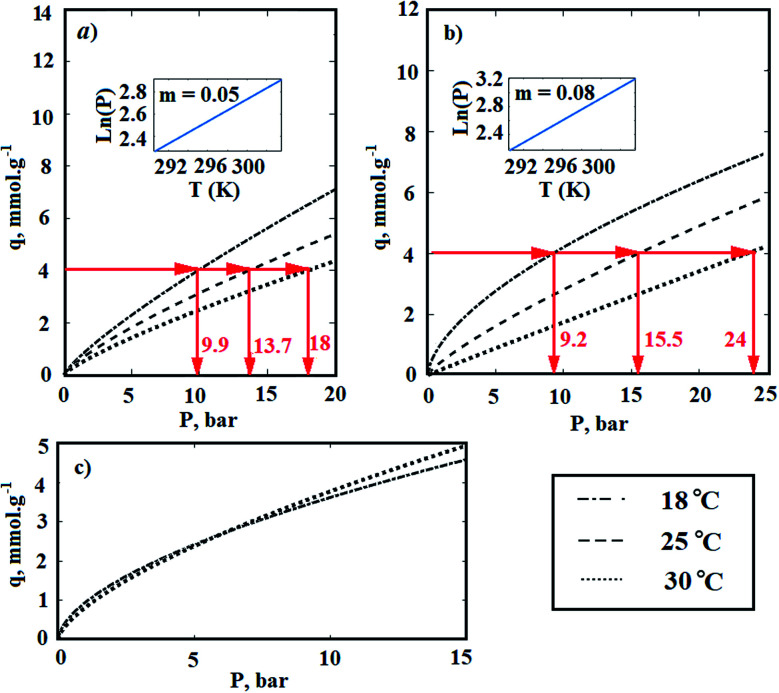

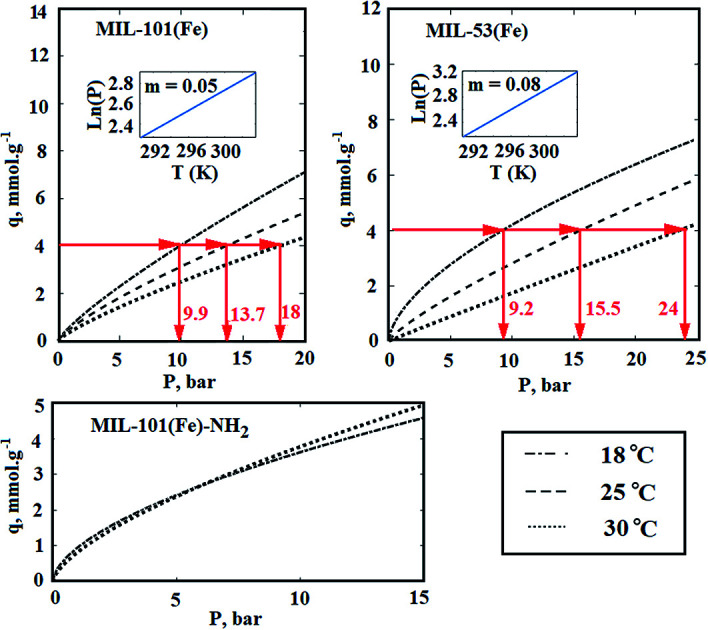

wherein R is the global gas constant (kJ mol−1 K−1), T is the absolute temperature (K), and P is the equilibrium pressure of the adsorption (bar). In order to calculate the heat of adsorption, the adsorption tests was performed in two other temperatures. For this purpose, the temperature of laboratory was uniformly adjusted in 18 and 30 °C respectively. Furthermore, the temperature of the adsorption chamber was recorded and controlled by an electrical jacketing system which was equipped with a temperature indicator and controller (TIC). In Fig. 10, the effect of temperature on the adsorption of CO2 by Fe-BDC sorbents is shown. According to Fig. 10(a), by plotting ln(P) vs. temperature and applying eqn (3), the amount of isosteric heat for MIL-101(Fe) has been achieved equal to 36.6 kJ mol−1. In the same way, the amount of isosteric heat for MIL-53(Fe) has been achieved equal to 58.7 kJ mol−1.

Fig. 10. The effect of temperature on the adsorption of CO2 by (a) MIL-101(Fe); (b) MIL-53(Fe); (c) MIL-101(Fe)–NH2.

Chemical adsorption, also known as chemisorption, is achieved by electron sharing between the adsorbent sites and adsorbate to form a covalent or ionic bond. Therefore, kinetically adsorption of CO2 needs an activation energy to reach equilibrium status. Although chemisorption of a certain vapor by the structural materials is a well-known phenomenon, a few data are available on it.61–65 As indicated in Fig. 10(c), the adsorption isotherm of MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 is independent to temperature. Therefore, if the activation energy of CO2 chemisorption by –NH2 agent is supposed to be supplied by released heat of physical adsorption, the amount of adsorption heat will be considered equal to the activation energy for primary alkanolamines. Since the activation energy for primary alkanolamine is equal to 46.7 kJ mol−1,2 the heat of adsorption can be supposed equal to 46.7 kJ mol−1.

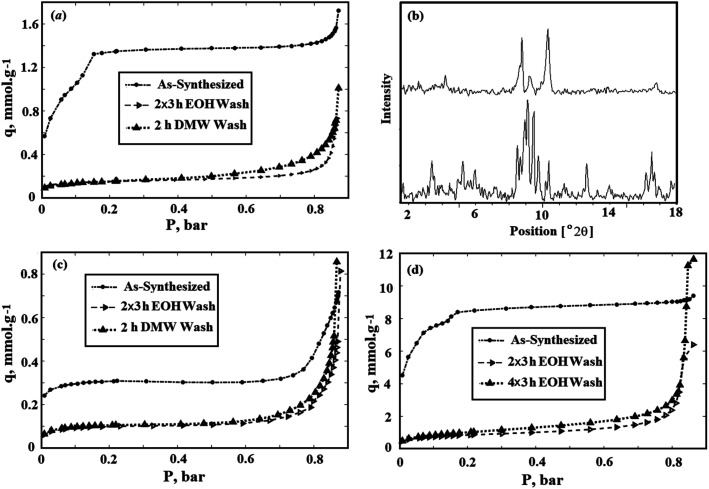

Water and solvent resistance

The resistance of synthesized sorbent has been investigated against water and ethanol. The surface area of MIL-101(Fe) after 2 h washing with DM water is significantly decreased from 125 to 14 m2 g−1. The same descent has been observed when it has been washed by ethanol (from 125 to 12 m2 g−1). The nitrogen adsorption isotherm of as-synthesized MIL-101(Fe) at 77 K is compared with the nitrogen isotherm of this sorbent after exposure to DM water and ethanol in Fig. 11(a). As is shown in this figure, the type of nitrogen isotherms for MIL-101(Fe) was changed from type-I to type-II after washing with DM water and ethanol. While the filling of the micropores occurs at low relative pressures and therefore, micropores lead to Type I isotherms, the nonporous or macroporous adsorbents yield Type II isotherms.66 Regarding to the sharp decline in the surface area of MIL-101(Fe) after exposure to DM water and ethanol, the destruction of adsorbent structure can be concluded. For more evidence, powder XRD pattern of as-synthesized MIL-101(Fe) has been compared with the XRD pattern of this sorbent after exposure to ethanol in Fig. 11(b) which it confirmed the mentioned results. Further investigations, such as washing sorbent with chloroform and DMF or heating it in the vacuum oven, were also performed, and no considerable positive effect on the surface area of MIL-101(Fe) was revealed. Therefore, as explained in Experimental section, no additional washing is performed after synthesis of MIL-101(Fe).

Fig. 11. (a) Comparison of nitrogen adsorption isotherms at 77 K for as-synthesized MIL-101(Fe) and MIL-101(Fe) washed with ethanol and DM water; (b) XRD pattern of as-synthesized MIL-101(Fe) (bottom) and MIL-101(Fe) after washing with ethanol (top); (c) comparison of nitrogen adsorption isotherms at 77 K for as-synthesized MIL-53(Fe) and MIL-53(Fe) washed with ethanol and DM water; (d) comparison of nitrogen adsorption isotherms at 77 K for as-synthesized MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 and MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 after washing with ethanol for 6 and 12 h.

Although, MIL-53(Fe) has shown more resistance against water in comparison to MIL-101(Fe), they also cannot be supposed as thermodynamically resistance against water, as discussed in the Introduction section. The surface area of MIL-53(Fe) after 2 h washing with DM water is decreased from 25 to 8 m2 g−1. The same result has been achieved when MIL-53(Fe) has been washed by ethanol and the surface area is decreased from 25 to 7 m2 g−1. The nitrogen adsorption isotherm of as-synthesized MIL-53(Fe) at 77 K is compared with its isotherm after exposure to DM water and ethanol in Fig. 11(c).

As mentioned before, washing the synthesized MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 with pure ethanol during 3 h for two times increased the BET surface area from 670 to 915 m2 g−1. Moreover, spending more time for washing will have reverse effect and decrease the BET surface area of this sorbent. Furthermore, the surface area of MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 has not considerable change after it has been washed 2 h with DM water. Therefore, among three synthesized sorbents, MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 has the best stability against water and ethanol.

For more investigation of the ethanol effect on the MIL-101(Fe)–NH2, the nitrogen adsorption isotherms at 77 K are presented for three different samples, as seen in Fig. 11(d). The first one is as-synthesized MOF without any further washing which its BET surface area was achieved equal to 670 m2 g−1. The second sample was washed two times for 3 h (totally 6 h) in 60 °C pure ethanol. As mentioned above, the BET surface area for this sample was achieved equal to 915 m2 g−1. Finally, the third sample was washed four times for 3 h (totally 12 h) in 60 °C pure ethanol. The BET surface area for this sample was obtained less than the second sample, and it was equal to 81 m2 g−1. As depicted in this figure, the type of nitrogen isotherms for MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 was changed from type-I to type-II after washing with pure ethanol. It seems that the macropores in the MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 structure has been increased by washing the sorbent with hot ethanol due to the extraction of the unreacted materials from its structure.

The relative crystallinity of MOFs can be reduced by the presence of the disordered unreacted precursors and solvent in the sorbent structure.21,67 As discussed above, no suitable method was found for extracting unreacted precursors and solvent, i.e. FeCl3, BDC and DMF, in MIL-101(Fe) and MIL-53(Fe) and also washing MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 for more than 2 h had a negative effect on the BET surface area. Therefore, the resulted degree of crystallinity for the synthesized Fe-BDCs was comparatively lower than degree of crystallinity for similar MOFs synthesized by Cr and Al as metal center.

The material properties such as hardness, density, melting point, transparency, and diffusion can be significantly affected by the degree of crystallinity.68 Although less stability of Fe-BDCs against water and solvents can be attributed to their lower degree of crystallinity, the achieved performance of CO2 adsorption was not considerably affected by it and relatively acceptable adsorption was achieved (see Fig. 9). Using different metal centers and solvents affects the properties such as hardness and stability, degree of crystallinity, etc.69–71 Differences between the synthesis conditions of MIL-101 and MIL-53 synthesized by Cr and Al compared to MIL-101 and MIL-53 synthesized by Fe, such as the reaction temperature (220 °C versus 110 °C) and solvent (water vs. DMF), may leads to the formation of more stable materials with lower energy levels. On the other hand, the higher stability of MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 against polar solvents, e.g. water and ethanol, can be attributed to the existence of amino agent in MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 structure and the formation of the hydrogen bond between them.

Conclusions

MIL-101(Fe), MIL-53(Fe) and Amino-MIL-101(Fe) were synthesized solvothermally using BDC ligands and Fe-based precursors. Characterization of the synthesized MOFs were performed by BET, SEM, and TGA methods. While the temperature resistance of MIL-53(Fe) was about 350 °C, the temperature resistances of MIL-101(Fe) and MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 were lower and near 100 °C and therefore, desorption of gas in high temperatures was not possible for these two sorbents. Adsorption tests for synthesized Fe-BDCs were performed by means of prepared volumetric setup. The achieved CO2 adsorption for MIL-101(Fe), MIL-53(Fe) and Amino-MIL-101(Fe) at 4 MP and 25 °C were equal to 9.3, 8.6 and 13 mmol g−1, respectively. Furthermore, the results showed that Amino-MIL-101(Fe) was more stable against water and ethanol, and its surface area increased from 670 to 915 m2 g−1 after being washed by ethanol. The heat of adsorption for synthesized MOFs was estimated by Clausius–Clapeyron equation. The achieved heat of adsorption for MIL-101(Fe), MIL-53(Fe) and MIL-101(Fe)–NH2 were equal to 36.6, 58.7, and 46.7 kJ mol−1 respectively. The achieved results revealed that in addition to physical adsorption of CO2 by Amino-MIL-101(Fe), chemisorption of carbon dioxide by NH2 agent in the structure of sorbent has also significant effect on the mechanism of adsorption.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Nomenclatures

- atm

Atmosphere

- BDC

1,4-Benzenedicarboxylate (terephthalate), fomula: C6H4-1,4-(CO2H)2

- BET

Brunauer–Emmett–Teller

- DM

Demineralized

- DMF

N,N-Dimethylformamide

- FESEM

Field emission scanning electron microscopy

- MIL

Material institute Lavoisier

- MOF

Metal organic framework

- R–P

Redlich–Peterson

- PSA

Pressure swing adsorption

- PXRD

Powder X-ray diffraction

- PT

Pressure transmitter

- SBUs

Secondary building units

- TGA

Thermal gravimetric analysis

- TIC

Temperature indicator and controller

- PSM

Postsynthetic modification

Supplementary Material

References

- Yan Q. Lin Y. Kong C. Chen L. Remarkable CO2/CH4 selectivity and CO2 adsorption capacity exhibited by polyamine-decorated metal–organic framework adsorbents. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:6873–6875. doi: 10.1039/C3CC43352H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. C. Tan C. A Review of CO2 Capture by Absorption and Adsorption. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2012;12:745–769. doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2012.05.0132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J. G., Nanotechnology for the Energy Challenge, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co, 2nd edn, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Burtch N. C. Jasuja H. Walton K. S. Water Stability and Adsorption in Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:10575–10612. doi: 10.1021/cr5002589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caskey S. R. Wong-Foy A. G. Matzger A. J. Dramatic Tuning of Carbon Dioxide Uptake via Metal Substitution in a Coordination Polymer with Cylindrical Pores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10870–10871. doi: 10.1021/ja8036096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britt D. Furukawa H. Wang B. Glover T. G. Yaghi O. M. Highly efficient separation of carbon dioxide by a metal-organic framework replete with open metal sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106(49):20637–20640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909718106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenecker P. M. Carson C. G. Jasuja H. Flemming C. J. J. Walton K. S. Effect of Water Adsorption on Retention of Structure and Surface Area of Metal–Organic Frameworks. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012;51:6513–6519. doi: 10.1021/ie202325p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan K. Zuluaga S. Gong Q. Gao Y. Nijem N. Li J. Thonhauser T. Chabal Y. J. Competitive co-adsorption of CO2 with H2O, NH3, SO2, NO, NO2, N2, Competitive co-adsorption of CO2 with H2O, NH3, SO2, NO, NO2, N2, O2, and CH4 in M-MOF-74 (M= Mg, Co, Ni): the role of hydrogen bonding. Chem. Mater. 2015;27(6):2203–2217. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b00315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeCoste J. B. Peterson G. W. Schindler B. J. Killops K. L. Browe M. A. Mahle J. J. The effect of water adsorption on the structure of the carboxylate containing metal–organic frameworks Cu-BTC, Mg-MOF-74, and UiO-66. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2013;38:11922–11932. doi: 10.1039/C3TA12497E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. Kuppler R. J. Zhou H. Selective gas adsorption and separation in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:1477–1504. doi: 10.1039/B802426J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. Liu X. Demir N. K. Chenbc J. P. Li K. Applications of water stable metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:5107–5134. doi: 10.1039/C6CS00362A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferey G. Mellot-Draznieks C. Serre C. Millange F. Dutour J. Surble S. Margiolaki I. A Chromium Terephthalate-Based Solid with Unusually Large Pore Volumes and Surface Area. Science. 2005;309:2040–2042. doi: 10.1126/science.1116275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q. Ning L. Zheng S. Tao M. Shi Y. He Y. Adsorption of Carbon Dioxide by MIL-101(Cr): Regeneration Conditions and Influence of Flue Gas Contaminants. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:2916. doi: 10.1038/srep02916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 1–6

- Taheri A. Ganji Babakhani E. Towfighi Darian J. A MIL-101(Cr) and Graphene Oxide Composite for Methane-Rich Stream Treatment. Energy Fuels. 2017;31(8):8792–8802. doi: 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b00917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn P. Bourrelly S. Serre C. Vimont A. Daturi M. Hamon L. Weireld G. D. Chang J. S. Hong D. Y. Hwang Y. K. Jhung S. H. Ferey G. High Uptakes of CO2 and CH4 in Mesoporous Metals Organic Frameworks MIL-100 and MIL-101. Langmuir. 2008;24:7245–7250. doi: 10.1021/la800227x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong D. Y. Hwang Y. K. Serre C. Ferey G. Chang J. S. Porous Chromium Terephthalate MIL-101 with Coordinatively Unsaturated Sites: Surface Functionalization, Encapsulation, Sorption and Catalysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009;19:1537–1552. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200801130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer S. Serre C. Devic T. Horcajada P. Marrot J. Ferey G. Stock N. High-Throughput Assisted Rationalization of the Formation of Metal Organic Frameworks in the Iron(III) Aminoterephthalate Solvothermal System. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47(17):7569–7576. doi: 10.1021/ic800538r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Pashow K. M. L. Rocca J. D. Xie Z. Tran S. Lin W. Postsynthetic Modifications of Iron-Carboxylate Nanoscale Metal-Organic Frameworks for Imaging and Drug Delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:14261–14263. doi: 10.1021/ja906198y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skobelev I. Y. Sorokin A. B. Kovalenko K. A. Fedin V. P. Kholdeeva O. A. Solvent-free allylic oxidation of alkenes with O2 mediated by Fe- and Cr-MIL-101. J. Catal. 2013;298:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2012.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. Li X. Liu B. Zhao Q. Chen G. Hexagonal microspindle of NH2-MIL-101(Fe) metal–organic frameworks with visible-lightinduced photocatalytic activity for the degradation of toluene. RSC Adv. 2016;6:4289–4295. doi: 10.1039/C5RA23154J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serre C. Millange F. Thouvenot C. Nogues M. Marsolier G. Loüer D. Ferey G. Very Large Breathing Effect in the First Nanoporous Chromium(III)-Based Solids: MIL-53 or CrIII(OH).{O2C-C6H4-CO2}.{HO2C-C6H4-CO2H}x·H2Oy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:13519–13526. doi: 10.1021/ja0276974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip L. Llewellyn L. Devic T. Ghoufi A. Clet G. Guillerm V. Pirngruber G. D. Maurin G. Serre C. Driver G. van Beek W. Jolimaıtre E. Vimont A. Daturi M. Ferey G. Co-adsorption and Separation of CO2-CH4 Mixtures in the Highly Flexible MIL-53(Cr) MOF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17490–17499. doi: 10.1021/ja907556q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourebrahimi S. Kazemeini M. Ganji Babakhani E. Taheri A. Removal of the CO2 from flue gas utilizing hybrid composite adsorbent MIL-53(Al)/GNP metal-organic framework. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2015;218:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2015.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han L. Zhang J. Mao Y. Zhou W. Xu W. Sun Y. Facile and green synthesis of MIL-53(Cr) and its excellent adsorptive desulfurization performance. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019;58(34):15489–15496. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.9b02223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra P. Uppara H. P. Mandal B. Gumma S. Adsorption and Separation of Carbon Dioxide Using MIL-53(Al) Metal-Organic Framework. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014;53(51):19747–19753. doi: 10.1021/ie5006146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. Lin H. Wang H. Suo Y. Li B. Kong C. Chen L. Enhanced selective CO2 adsorption on polyamine/MIL-101(Cr) composites. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2014;2:14658–14665. doi: 10.1039/C4TA01174K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. M. Postsynthetic Methods for the Functionalization of Metal_Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:970–1000. doi: 10.1021/cr200179u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal V., Functional Nanomaterials and Nanotechnologies: Applications for Energy & Environment, Central West Publishing, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Pereza E. Olivares-Marin M. Arencibiac A. Sanzc R. Calleja G. Maroto-Valer M. CO2 adsorption performance of amino-functionalized SBA-15 under post-combustion conditions. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control. 2013;17:366–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ijggc.2013.05.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. Kong C. Chen L. Direct synthesis of amine-functionalized MIL-101(Cr) nanoparticles and application for CO2 capture. RSC Adv. 2012;2:6417–6419. doi: 10.1039/C2RA20641B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serra-Crespo P. Ramos-Fernandez E. V. Gascon J. Kapteijn F. Synthesis and Characterization of an Amino Functionalized MIL-101(Al): Separation and Catalytic Properties. Chem. Mater. 2011;23(10):2565–2572. doi: 10.1021/cm103644b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abid H. Rada Z. H. Shang J. Wang S. Synthesis, Characterization, and CO2 Adsorption of three Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): MIL-53, MIL-96, and Amino-MIL-53. Polyhedron. 2016;120:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2016.06.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taheri A. Ganji Babakhani E. Towfighi J. Methyl mercaptan removal from natural gas using MIL-53(Al) J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2017;38:272–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jngse.2016.12.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang D. Keenan L. L. Burrows A. D. Edler K. J. Synthesis and post-synthetic modification of MIL-101(Cr)-NH2 via a tandem diazotisation process. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:12053–12055. doi: 10.1039/C2CC36344E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira R. B. Scheetz P. M. Formiga A. L. B. Synthesis of amine-tagged metal–organic frameworks isostructural to MIL-101(Cr) RSC Adv. 2013;3:10181–10184. doi: 10.1039/C3RA23443F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernt S. Guillerm V. Serre C. Stock N. Direct covalent post-synthetic chemical modification of Cr-MIL-101 using nitrating acid. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:2838–2840. doi: 10.1039/C0CC04526H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Y. K. Hong D. Y. Chang J. S. Jhung S. H. Seo Y. K. Kim J. Vimont A. Daturi M. Serre C. Ferey G. Amine grafting on coordinatively unsaturated metal centers of MOFs: consequences for catalysis and metal encapsulation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:4144–4148. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. C. Yan Q. J. Kong C. L. Chen L. Polyethyleneimine Incorporated Metal-Organic Frameworks Adsorbent for Highly Selective CO2 Capture. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1859–1866. doi: 10.1038/srep01859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janiak C. Vieth J. K. MOFs, MILs and more: concepts, properties and applications for porous coordination networks (PCNs) New J. Chem. 2010;34:2366–2388. doi: 10.1039/C0NJ00275E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. Kong C. Chen L. Direct synthesis of amine-functionalized MIL-101(Cr) nanoparticles and application for CO2 capture. RSC Adv. 2012;2:6417–6419. doi: 10.1039/C2RA20641B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamon L. Llewellyn P. L. Devic T. Ghoufi A. Clet G. Guillerm V. Pirngruber G. D. Maurin G. Serre C. Driver G. van Beek W. Jolimaître E. Vimont A. Daturi M. Ferey G. Co-adsorption and Separation of CO2–CH4 Mixtures in the Highly Flexible MIL-53(Cr) MOF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17490–17499. doi: 10.1021/ja907556q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn P. L. Horcajada P. Maurin G. Devic T. Rosenbach N. Bourrelly S. Serre C. Vincent D. Loera-Serna S. Filinchuk Y. Ferey G. Complex Adsorption of Short Linear Alkanes in the Flexible Metal-Organic-Framework MIL-53(Fe) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:13002–13008. doi: 10.1021/ja902740r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford J. I. Louer D. Powder diffraction. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1996;59:131–234. doi: 10.1088/0034-4885/59/2/002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brunauer S. Emmett P. H. Teller E. Adsorption of gases in multimolecular layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938;60(2):309–319. doi: 10.1021/ja01269a023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scarlett B., Lowell S. and Shields J. E., Powder Surface Area and Porosity, Chapman and Hall, London, 2nd edn, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- Freundlich H. M. F. Over the adsorption in solution. J. Phys. Chem. 1906;57:385–470. [Google Scholar]

- Langmuir I. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918;40:1361–1403. doi: 10.1021/ja02242a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tempkin M. I. Pyzhev V. Kinetics of ammonia synthesis on promoted iron catalysts. Acta Physiochim., URSS. 1940;12:217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Sips R. On the structure of a catalyst surface. J. Chem. Phys. 1948;16:490–495. doi: 10.1063/1.1746922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Redlich O. J. Peterson D. L. A useful adsorption isotherm. J. Phys. Chem. 1959;63:1024–1026. doi: 10.1021/j150576a611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toth J. State equations of the solid gas interface layer. Acta Chim. Acad. Hung. 1971;69:311–317. [Google Scholar]

- Horcajada P. Serre C. Maurin G. Ramsahye N. A. Balas F. Vallet-Regí M. Sebban M. Taulelle F. Férey G. Flexible Porous Metal-Organic Frameworks for a Controlled Drug Delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6774–6780. doi: 10.1021/ja710973k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu T. A. Le G. H. Dao C. D. Dang L. Q. Nguyen K. T. Nguyen Q. K. Dang P. T. Tran H. T. K. Duong Q. T. Nguyena T. V. Leed G. D. Arsenic removal from aqueous solutions by adsorption using novel MIL-53(Fe) as a highly efficient adsorbent. RSC Adv. 2015;5(7):5261–5268. doi: 10.1039/C4RA12326C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thommes M. Kaneko K. Neimark A. V. Olivier J. P. Rodriguez-Reinoso F. Rouquerol J. Sing K. S. W. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report) Pure Appl. Chem. 2015;87:1051–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Abid H. Rada Z. H. Shang J. Wang S. Synthesis, Characterization, and CO2 Adsorption of three Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): MIL-53, MIL-96, and Amino-MIL-53. Polyhedron. 2016;120:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2016.06.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Q. Lin Y. Kong C. Chen L. Remarkable CO2/CH4 selectivity and CO2 adsorption capacity exhibited by polyamine-decorated metal–organic framework adsorbents. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:6873–6875. doi: 10.1039/C3CC43352H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Builes S. Sandler S. I. Xiong R. Isosteric Heats of Gas and Liquid Adsorption. Langmuir. 2013;29:10416–10422. doi: 10.1021/la401035p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sircar S. Mohr R. Ristic C. Rao M. B. Isosteric Heat of Adsorption: Theory and Experiment. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1999;103:6539–6546. doi: 10.1021/jp9903817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marathe R. P. Farooq S. Srinivasan M. P. Modeling Gas Adsorption and Transport in Small-Pore Titanium Silicates. Langmuir. 2005;21(10):4532–4546. doi: 10.1021/la046938d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourebrahimi S. Kazemeini M. Ganji Babakhani E. Taheri A. Removal of the CO2 from flue gas utilizing hybrid composite adsorbent MIL-53(Al)/GNP metal-organic framework. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2015;218:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2015.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal B. R., Nuclear safety in light water reactors, Elsevier, 1st edn, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Mihaylov M. Chakarova K. Andonova S. Drenchev N. Ivanova E. Sabetghadam A. Seoane B. Gascon J. Kapteijn F. Hadjiivanov K. Adsorption Forms of CO2 on MIL-53(Al) and NH2-MIL-53(Al) As Revealed by FTIR Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016;120:23584–23595. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b07492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Zambrano K. S. Duarte L. L. Maia D. A. S. Vilarrasa-García E. Bastos-Neto M. Rodríguez-Castellón E. de Azevedo D. C. S. CO2 Capture with Mesoporous Silicas Modified with Amines by Double Functionalization: Assessment of Adsorption/Desorption Cycles. Materials. 2018;11(887):1–19. doi: 10.3390/ma11060887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaig R. W. Osborn Popp T. M. Fracaroli A. M. Kapustin E. A. Kalmutzki M. J. Altamimi R. M. Fathieh F. Reimer J. A. Yaghi O. M. The Chemistry of CO2 Capture in an Amine-Functionalized Metal–Organic Framework under Dry and Humid Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:12125–12128. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b06382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn M. W. Jelic J. Berger E. Reuter K. Jentys A. Lercher J. A. Role of Amine Functionality for CO2 Chemisorption on Silica. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2016;120:1988–1995. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b10012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muttakin M. Mitra S. Thu K. Ito K. Baran Saha B. Theoretical framework to evaluate minimum desorption temperature for IUPAC classified adsorption isotherms. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer. 2018;122:795–805. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.01.107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loiseau T. Serre C. Huguenard C. Fink G. Taulelle F. Henry M. Bataille T. Ferey G. A rationale for the large breathing of the porous aluminum terephthalate (MIL-53) upon hydration. Chem.–Eur. J. 2004;10:1373–1382. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava A., Introduction to Plastics Engineering, Elsevier Inc., 2018 [Google Scholar]

- Masoomi M. Y. Morsali A. Dhakshinamoorthy A. Garcia H. Mixed-Metal MOFs: Unique Opportunities in Metal-organic Framework Functionality and Design. Angew. Chem. 2019;131(43):15330–15347. doi: 10.1002/ange.201902229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. Henke S. Cheetham A. K. Research Update: Mechanical properties of metal-organic frameworks – Influence of structure and chemical bonding. APL Mater. 2014;2:123902. doi: 10.1063/1.4904966. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; , 1–9

- Soni S. Kumar Bajpai P. Arora C. A Review on Metal-organic Framework: Synthesis, Properties and Application. Characterization and Application of Nanomaterials. 2019;2:1–20. [Google Scholar]