Abstract

In recent years, human flourishing and its relationship to mental health have attracted significant attention in a wide range of fields. As an interdisciplinary, mixed-methods team with strong roots in critical medical anthropology and critical public health, we are intrigued by the possibility that a focus on flourishing may reinvigorate health research, policy, and clinical care in transformative ways. Yet current proposals to this effect, we contend, must be met with caution. In particular, we call attention to the troubling disconnect between current research on flourishing, on one hand, and the voluminous body of scholarship demonstrating the detrimental impact of structural inequities on health, on the other. We illuminate this blind spot in two ways. We begin with a critical assessment of leading conceptions of flourishing in positive psychology, which are compared to current approaches in the critical social sciences of health. In the second half of the paper, we support our argument by presenting original findings from a mixed-methods study with a diverse sample of interviewees in the Midwestern U.S. city of Cleveland, Ohio (n=167). Our interviewees’ rich narrative accounts, which we analyze both quantitatively and qualitatively, highlight important ways in which everyday understandings of flourishing diverge from prevailing scholarly accounts. Given these gaps and blind spots, now is an opportune time for robust interdisciplinary discussion about the implicit values and presumptions underpinning leading approaches to flourishing and their wide-ranging implications for research, policy, and clinical care in mental health fields and beyond.

Keywords: Flourishing, Well-being, Structural determinants of health, Social determinants of health, Qualitative research, Mixed-methods research

1. Introduction

One year into the COVID-19 pandemic, the New York Times published a series of articles on “flourishing” and its presumed inverse, “languishing,” that tapped a nerve among readers. One article—which garnered well over 1,300 reader comments—defined flourishing as “the peak of well-being,” contrasting it with depression (“the valley of ill-being”) and languishing (“the neglected middle child of mental health”) (Grant, 2021, citing Keyes, 2002). Related articles followed, including a “flourishing quiz” (New York Times, 2021, citing VanderWeele, 2017) and an article outlining “simple activities” that “can lead to marked improvement in overall well-being” (Blum, 2021). This New York Times series and lively response speak not only to a strong popular sense that the COVID-19 pandemic has impeded people's ability to flourish, but also to a burgeoning interest in flourishing in the scholarly, clinical, and policy realms (Agenor, Conner, & Aroian, 2017; Bethell, Gombojav, & Whitaker, 2019; Hewitt, 2019; Marmot, 2017; Mattingly, 2014; Parens and Johnston, 2019; Prah Ruger, 2020; VanderWeele, McNeely, & Koh, 2019, 2021; Willen et al., 2021).

So strong is this interest that a vast amount of research investment is now being channeled toward the topic of flourishing, in mental health fields and beyond (Institute for the Study of Religion, Baylor University, 2021; Templeton World Charity Foundation, 2021a, 2021b). Some even suggest that a strategic focus on the topic might “open a national conversation that reframes and reimagines traditional concepts of health,” including “a more useful way to address policy and societal goals than current options” (VanderWeele et al., 2019).

As an interdisciplinary research team with strong roots in critical medical anthropology and critical public health, we argue that the idea of reorienting health research, policy, and clinical care around the goal of promoting human flourishing is intriguing—but that current proposals to this effect must be met with caution. Before bold efforts to promote flourishing can be justified, we first must ask: Whose definitions of flourishing provide the roadmap? What assumptions undergird these definitions? Whose flourishing are they designed to support? Another key question follows: Do scholarly definitions of flourishing resonate with everyday, real world usages of the term, or are any essential dimensions overlooked, or left out? Above all, we must ask: Are prevailing conceptions of flourishing well-suited to the task of confronting the most urgent problems in current health research, policy, and clinical care—or, alternatively, might they risk leading us astray?

These questions are both timely and urgent for multiple reasons, but one reason stands out in particular. As we elaborate below, leading approaches define flourishing largely in terms of individual psychological characteristics, with the implication that efforts to promote flourishing should concentrate on individual-level, psychological interventions. Absent from most approaches is any substantive attention to the broader structures and dynamics—historical, political, sociocultural, environmental, and ideological—that shape and constrain individual and collective chances of flourishing in the first place.

From a critical public health standpoint, this inattention to structure, power, and history constitutes a serious blind spot. Specifically, it signals a troubling disconnect between current research on flourishing, on one hand, and the voluminous body of scholarship demonstrating the detrimental, and intersectional, impact of structural inequities on health, on the other. In recent decades, a powerful evidence base has illuminated the many pathways through which historical and present-day forms of inequity and injustice harm individual and population health (Burke et al., 2011, Geronimus, Hicken, Keene, & Bound, 2006, Krieger, 2011, Link and Phelan, 1995, Phelan & Link, 2015, Yearby, 2020). We now know in great detail how mental and physical health are harmed by inequities in access to the social and structural determinants of good health (e.g., food, housing, education, jobs), and how racism and other forms of institutional, interpersonal, and internalized discrimination can compound the detrimental impact of structural injustices, often in intersectional ways (Bailey et al., 2017, Benfer et al., 2015, Benfer, Mohapatra, Wiley, & Yearby, 2020, Boyd, 2018, Hicken, Kravitz-Wirz, Durkee, & Jackson, 2018, Krieger, 2011, Lee, Wildeman, Wang, Matusko, & Jackson, 2014, Ortiz & Johannes, 2018, Subica & Link, 2022, Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012, Williams & Wyatt, 2015, Yearby et al., 2020). Given the overwhelming evidence that inequity and injustice harm health, why aren't we paying equally careful attention to the ways in which upstream structural factors can thwart individual and collective opportunities to flourish?

With this overarching question in mind, this paper aims to lay the groundwork for broader interdisciplinary dialogue around what flourishing means, how we should study it, and how it can best be promoted, especially in relation to mental health. We begin by reviewing the current landscape of research on flourishing and health, where approaches from positive psychology predominate, then compare leading approaches to an alternative set of perspectives from medical anthropology, disability studies, bioethics, and related fields.

In the second half, we present findings from an original, mixed-methods study that reveals important divergences between prevailing analytic (or what anthropologists call “etic”) perspectives on flourishing and everyday vernacular (or “emic”) understandings. Our empirical findings, drawn from interviews with a diverse sample of people (n=167) in the Midwestern U.S. city of Cleveland, Ohio, highlight the importance of investigating how flourishing is both understood and pursued in real-life contexts. Our interviewees' first-person perspectives reveal, in rich and vivid detail, how everyday understandings of flourishing are complex, dynamic, and relational—and, as such, are poorly captured by prevailing indexes (such as Diener et al., 2010; Huppert & So, 2013; Keyes, 2002; Ryan & Deci, 2001; Ryff, 1989; Ryff & Singer, 2008; Seligman, 2010; VanderWeele, 2017). In addition, our interviewees' narrative accounts shed both quantitative and qualitative light on the powerful role of structural, material, and political circumstances in shaping people's opportunities to flourish, especially among those whose lives are constrained by disadvantage (see also Cele, et al., 2021).

Overall, these research findings bolster our argument that now is an opportune time for robust interdisciplinary dialogue about the implicit values and assumptions underpinning leading approaches to flourishing; the gaps that separate “emic” and “etic” understandings; and the implications of these insights for researchers, clinicians, funders, and policymakers in mental health and beyond. The New York Times series mentioned earlier offers a convenient opportunity to pose these vital questions: Whose vision of flourishing undergirds popular articles like these? Who is most likely to benefit from the “simple activities” to promote flourishing they propose (Blum, 2021; see also VanderWeele, 2020)? Whose flourishing, in contrast, can only be advanced through different kinds of action—for instance, actions to confront and combat the root causes of health inequities?

By asking questions like these, and by subjecting leading definitions of flourishing to critical scrutiny, our aim is not to advance a singular, alternative set of “right answers,” but rather to sharpen our collective understanding by seeking “better questions to ask” (Fassin and Das, 2021: 7). Before tackling these questions, it is first worth asking: Why does the concept of flourishing hold appeal across disciplines and domains?

2. Flourishing's appeal

For researchers, clinicians, and policymakers, the appeal of this concept is clear. Flourishing bears strong positive associations. It has a familiar ring in everyday parlance, at least in English, and it evokes a holistic sense of things going well—of moving steadily forward on a stable path. From a health sciences standpoint, the notion of flourishing resonates with assets-based alternatives to the sort of deficit models that have drawn criticism, either for failing to acknowledge (and leverage) individual or community strengths, or for the graver misstep of blaming sufferers for their own misfortune (Brooks & Kendall, 2013; Chen et al., 2019; Keyes, 2002; Lee et al., 2021).

Above all, flourishing holds considerable appeal as an alternative to biomedicalized conceptions of health, whose limitations are especially evident in the present moment of global pandemic (Benfer et al., 2020; Bowleg, 2020; Holmes et al., 2020; Jackson & Lee Williams, 2021; Metzl, Maybank, & De Maio, 2020; Pfefferbaum & North, 2020; Team & Manderson, 2020). While current efforts to promote flourishing hew toward psychological interventions, the concept could, at least in principle, be reinterpreted in a manner that helps reinvigorate the holistic WHO definition of health (as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (World Health Organization, 1946))—a definition whose role in critical public health and related fields has been pivotal (Braveman et al., 2011; CSDH, 2008; Kickbusch, 2015; Kohrt and Mendenhall, 2015), but extraordinarily difficult to translate into policy and practice.

In short, flourishing has garnered interest in a wide range of mental health and related fields as a nimble and useful “boundary object”—a concept that is “plastic enough to adapt to local needs and constraints … yet robust enough to maintain a common identity across sites” (Star and Griesemer, 1989: 393; see also Willen, 2022). Yet this very plasticity, and the presumption of consensus it entails, conceal significant differences—differences, we argue, that matter a great deal and thus merit careful scrutiny.

To this end, we follow anthropologists Fassin and Das, who argue that, “Scrutinizing the terms” we use and “exploring their meanings and histories” can be a powerful way to “refresh our perspective on the most serious issues of our time” (Fassin & Das, 2021: 6). As the next section shows, such an exercise can help clarify where our concepts “may not express what we try to think”—or, as importantly, where they may be failing us.

3. Rethinking flourishing

In the increasingly lively and interdisciplinary landscape of research on flourishing and health, approaches from positive psychology predominate. As noted earlier, flourishing is framed in positive psychology as an individual, psychological matter and conceptualized, in top-down fashion, as an abstract and presumably universal research construct that can best be assessed in quantitative terms. Although positive psychologists have invested a tremendous amount of effort in operationalizing the concept, “no internationally recognized gold-standard measurement tool for flourishing exists” (Hone, Jarden, & Schofield, 2014: 1033). For this reason, among others, Agenor and colleagues contend that the concept is still “immature” (Agenor et al., 2017).

Efforts to define flourishing in positive psychology, and to distinguish it from similar and related terms, have posed ongoing conceptual challenges. In a frequently cited article, Hone and colleagues (2014) compare four leading approaches to flourishing,1 each involving a quantitative index comprising five or more factors. In Table 1 , we update their original chart to include two additional indexes. In the original comparison, only three factors—“positive relationships,” “meaning and purpose,” and “engagement” or “positive affect”—were common across the set. In our updated comparison, a mere two factors—“positive relationships” and “meaning and purpose”—figure in all six. Three additional factors—“self-acceptance/“self-esteem,” “engagement” (or “flow”), and “positive emotion” (or “happiness”)—appear in four of the six.

Table 1.

Six approaches to flourishing in positivepsychology.

| KEYES 2002 | HUPPERT & SO 2013 | DIENER et al., 2010 | SELIGMAN 2011 | RYFF & SINGER 2008 | VANDERWEELE 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive relationships | Positive relationships | Positive relationships | Positive relationships | Positive relationships | Close social relationships |

| Purpose in life | Meaning | Purpose and meaning | Meaning and purpose | Purpose in life | Meaning and purpose |

| Positive affect (interested) | Engagement | Engagement | Engagement | ||

| Self-acceptance | Self-esteem | Self-acceptance and self-esteem | Self-acceptance | ||

| Positive affect (happy) | Positive emotion | Positive emotion | Happiness and life satisfaction | ||

| Competence | Competence | Accomplishment/Competence | |||

| Optimism | Optimism | ||||

| Social contribution | Social contribution | ||||

| Social integration | |||||

| Social growth | |||||

| Social acceptance | |||||

| Social coherence | |||||

| Environmental mastery | Environmental mastery | ||||

| Personal growth | Personal growth | ||||

| Autonomy | Autonomy | ||||

| Life satisfaction | |||||

| Emotional stability | |||||

| Vitality | |||||

| Resilience | Physical and mental health | ||||

| Character and virtue | |||||

| OPTIONAL: Financial and material stability | |||||

Table 1 is an update and adaptation of Hone, Jarden, Schofield, & Duncan, 2014: 65.

Given these wide variations, it is perhaps unsurprising that analyses based on these leading models yield different results. In fact, a nationally representative study designed by Hone and colleagues revealed strikingly low levels of correspondence among them (Hone, Jarden, Schofield, & Duncan, 2014). The authors surveyed 10,000 adults in New Zealand with the goal of replicating the four models in their comparison. Depending which model was used, rates of flourishing spanned a stunning range—from about one-quarter (24%, using Huppert and So's model) to nearly twice that number (47% using Seligman's).

4. A welter of definitions

Yet inconsistencies among leading conceptions of flourishing are not the only source of conceptual confusion. Another involves slippage between flourishing and other terms such as “resilience,” “functioning,” and especially “well-being” (Ryff, 1989; Ryan & Deci, 2001; Ryff & Singer, 2008; Lee et al., 2021; Diener and Michalos, 2009; Seligman, 2011; Plough, 2015; Plough, 2020; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018). This overall terminological slipperiness is evident in Table 2 , where we consolidate a range of definitions from multiple health fields. Our aim here is not to present a systematic review, but rather to highlight the terminological slippage both among positive psychology approaches and between those approaches and another family of approaches: those in medical anthropology, disability studies, bioethics, and other critical social sciences of health.

Table 2.

Definitions of flourishing across health-related disciplines.

| Author | Discipline | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Keyes 2002 | Positive psychology | “Adults with complete mental health are flourishing in life with high levels of well-being. To be flourishing, then, is to be filled with positive emotion and to be functioning well psychologically and socially." |

| Seligman 2011 | Positive psychology | “I now think that the topic of positive psychology is well-being, that the gold-standard for measuring well-being is flourishing, and that the goal of positive psychology is to increase flourishing." |

| Huppert & So 2013 | Positive psychology | “Flourishing refers to the experience of life going well. It is a combination of feeling good and functioning effectively. Flourishing is synonymous with a high level of mental wellbeing, and it epitomises mental health (Huppert 2009a, b; Keyes 2002; Ryff and Singer 1998)." |

| Vanderweele 2017 | Positive psychology | “Flourishing itself might be understood as a state in which all aspects of a person's life are good. We might also refer to such a state as complete human well-being, which is again arguably a broader concept than psychological well-being." |

| Ryff & Singer 2008; Ryff 2014 |

Positive psychology |

Flourishing, understood as “eudaimonic well-being,” involves “striving toward excellence based on one's unique potential” or “striving to achieve the best that is within us.” |

| Garland-Thomson 2019 | Bioethics/Disability studies | “Flourish is a verb … To flourish is to do something. … to ‘grow or develop … In a vigorous way’ within ‘a particularly congenial environment.’” |

| Roberts 2019 | Bioethics/Critical legal theory | “… for individuals to flourish, they must be situated in societies that promote their flourishing. … It is not an accident that the assumed understanding of human flourishing has been determined by what improves the well-being of those who are the most privileged in society and in a way that legitimizes their privileged position. … [I]t has elided structural inequalities that advantage them and disadvantage others.” |

| Jennings 2019 | Bioethics | “Contemporary notions of flourishing … call for the creation of an associational environment of rights, equality, dignity, and respect in which each person has the social supports and opportunities necessary to develop many capabilities and to realize many pathways of self-development and meaningful self-identity.” |

| Willen et al., 2021 | Anthropology/Public health | “We define the pursuit of flourishing as an active process of striving to live in keeping with one's defining values, commitments and vision for the future, as individuals and in the context of one's family and the communities to which one belongs. Flourishing is not simply a psychological state, but an active pursuit informed by cultural expectations and social relationships, and influenced by the social, political and economic structures that shape people's lives.” |

The top half of the chart presents definitions from positive psychology, and the bottom half presents definitions from the critical social sciences of health.

In the first group, Seligman (who recently declared his shift in interest from “happiness” to “flourishing”) contends that “the topic of positive psychology is well-being,” and “the gold-standard for measuring well-being is flourishing” (Seligman, 2011: 13). Keyes also suggests an equivalence among flourishing, “complete mental health,” and “high levels of well-being. To be flourishing,” he continues, “is to be filled with positive emotion and to be functioning well psychologically and socially” (Keyes, 2002: 210). VanderWeele takes an even more expansive view of both flourishing and well-being— and often uses them interchangeably. In his view, flourishing is “a state in which all aspects of a person's life are good” (VanderWeele, 2017: 8149; see also Lee et al., 2021).

A divergent approach in positive psychology is rooted in the influential work of Ryff, who conceptualizes flourishing explicitly in relation to Aristotle's notion of eudaimonia, a term that is variably translated as “flourishing,” “the good life,” or—however misleadingly—happiness (Mattingly, 2014; Ryff, 1989; Ryff & Singer, 2008). Ryff's conception of “eudaimonic well-being,” which she uses interchangeably with flourishing, involves “striving toward excellence based on one's unique potential” (Ryff and Singer, 2008: 14). This formulation resonates in important ways with approaches introduced in the second half of Table 2. It also resonates with the contemporary rereading of Aristotle proposed in the introduction to this series, which argues that the ability to reach one's potential depends not just on internal factors, but also on the structural, material, political, social, and ideological environments in which we live (Willen, 2022). As a result, Ryff's approach is somewhat less susceptible to some of the blind spots to which we now turn.

5. Flourishing in critical perspective

From a critical social science perspective, positive psychology approaches to flourishing display a number of troubling blind spots, some epistemological and others methodological, as the second half of Table 2 suggests.

First, since people's capacity to flourish depends heavily on the circumstances in which they live (Garland-Thomson, 2019; Jennings, 2019; Mattingly, 2014; Parens and Johnston, 2019; Roberts, 2019), any account of flourishing that limits itself to the psychological domain will necessarily fall short. Formal political, economic, legal, and educational systems and structures all matter, as do entrenched patterns of injustice and legacies of structural racism and historical trauma. As bioethicist and critical legal theorist Dorothy Roberts explains, “for individuals to flourish, they must be situated in societies that promote their flourishing” (Roberts, 2019: 201). Bioethicist and disability theorist Rosemary Garland-Thomson makes a similar point, noting that, “Hostile environments thwart flourishing; congenial environments promote it” (Garland-Thomson, 2019: 24).

But who has the good fortune of living in environments that promote flourishing, and who ends up inhabiting hostile ones? This question points to a second and related blind spot involving the role of power and (in)justice in shaping not just who has a chance to flourish but also, for that matter, how flourishing itself is defined in policy conversations. As Roberts points out, “It is not an accident that the assumed understanding of human flourishing has been determined by what improves the well-being of those who are the most privileged in society and in a way that legitimizes their privileged position … [This assumption] has elided structural inequalities that advantage them and disadvantage others” (Roberts, 2019: 203).

Third, indexes that conceptualize flourishing in static terms (i.e., as a condition or state) fail to capture the dynamic and contextually-specific ways it is imagined, pursued, and experienced in everyday settings—including possibilities of flourishing in one domain, but not others. As Garland-Thomson puts it, “Flourish is a verb, and as such expresses action. To flourish is to do something” (Garland-Thomson, 2019: 21). Understood in this way, flourishing is an active pursuit that involves choice-making and action, under conditions of constraint, over time. And this “active pursuit” is no solo endeavor; rather, it is “informed by cultural expectations and social relationships” (Willen et al., 2021; see also Cele et al., 2021).

Finally, the pursuit of flourishing may be informed by shared values and expectations, but it is also a deeply personal matter shaped by individual efforts to live in keeping with those values and life commitments that are “so deep” to who people are that they “would not know themselves” without them (Mattingly, 2014: 12; see also Willen, 2019: 14-16). For this reason, among others, critical social scientists of health, and medical anthropologists in particular, see value in using qualitative methods to investigate what flourishing means in everyday, “emic” terms.

This view of flourishing—as an active, dynamic pursuit that is deeply informed both by people's sociopolitical position and by the environments in which they live—resonates not only across the critical social science perspectives collected here, but also in the rich narratives of our interviewees, to whom we now turn.

6. Methods

In an effort to learn “how closely … theoretical conceptualisations of flourishing reflect laypeople's real world understanding of what it is to be flourishing” (Hone, Jarden, Schofield, & Duncan, 2014: 72), we asked a diverse sample of 167 residents of Greater Cleveland, Ohio, to share their perspectives on flourishing in a series of open-ended, semi-structured interviews conducted in 2018–19. The interviews were part of a larger study, ARCHES | the AmeRicans' Conceptions of Health Equity Study, that was designed to explore everyday conceptions of “health-related deservingness” (Willen, 2012, Willen & Cook, 2016; Geeraert, 2021; Holmes et al., 2021; Huschke, 2014; Viladrich, 2019)—i.e., how people think about what they and others deserve in the health domain—and how such views and values can shift over time (Walsh et al., 2022, Willen, Williamson, & Walsh, 2021). Interview questions spanned a range of topics, including interviewees' reflections on what flourishing and health mean in their own lives and communities; whether they feel they get their “fair share” of society's resources; and whether they feel they matter in society (see Appendix A for the full interview guide).

We designed the study in partnership with a local health and equity initiative that has been recognized nationally as a well-coordinated, thoughtful strategy for tackling health inequities and promoting health equity, Health Improvement Partnership–Cuyahoga (HIP-Cuyahoga) (Halko and Brown, 2016). The existence of this local initiative was a key factor in selecting Greater Cleveland as fieldsite for this research, as was two of the three lead researchers' deep familiarity with the city and its broader metropolitan area. As an urban center, Cleveland is similar in key respects to many other American cities. Yet it also exhibits some of the country's greatest disparities in health outcomes by race-ethnicity and class, including bellwether indicators such as life expectancy, infant mortality, and childhood lead exposure (Healthy Northeast Ohio, 2021). These inequities reflect a deep and troubling legacy of laws, policies, and informal practices that explicitly treat certain groups in the city as more deserving than others of society's attention, investment, and concern (Reece et al., 2015)—and, as we heard from our interviewees, that continue to have palpable effects today.

For the larger project, we attended committee and subcommittee meetings and public events of the health and equity initiative as participant observers. One of us (CCW) also served on HIP-Cuyahoga's subcommittee on eliminating structural racism. Just under one-third of interviewees were recruited through the initiative itself (n=53), and others were recruited through its community partners; via snowball sampling; and through outreach in community venues. Outreach and recruitment efforts included social media posts as well as flyers in public locations such as stores and public libraries. Interviews were conducted by a trained team of nine interviewers in interviewees' locations of choice, which included homes, offices, and public locations such as coffee shops, restaurants, and public libraries. Interview locations spanned both the city proper and the broader metropolitan area. Our team consisted of five anthropologists (including one graduate student), a political scientist, an urban sociologist, a public health and law scholar, and a public health professional. Interviews lasted approximately 1½ hours, and participants completed a demographic survey on an iPad after their interview. Interviewees received a US$25 gift card as a token of appreciation. The study was approved by the IRB at the University of Connecticut.

As Table 3 illustrates, these recruitment strategies yielded a diverse sample of local residents that included public health professionals (n=21), clinicians (n=21), metro-wide decisionmakers (n=21), and community leaders (n=24), as well as community members (n=80). Most of the community members we interviewed had not participated in the equity initiative (71 of 80), and as a group they approximate the demographics of the county. The full sample included people from a wide range of backgrounds, occupations, and social positions, among them students and retirees, artists and civil servants, clinicians, elected leaders, business owners, community activists, and people experiencing unemployment and homelessness.

Table 3.

Interview sample, with comparison toCuyahogaCounty.

| Cuyahoga County |

Community Member Sample |

Full Sample |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | ||

| Interview Type | |||||

| Decision-Makers | – | – | – | 21 | 13% |

| Community Leaders | – | – | – | 24 | 14% |

| Public Health Professionals | – | – | – | 21 | 13% |

| Clinicians | – | – | – | 21 | 13% |

| Community Members | – | – | – | 80 | 48% |

| 167 | 100% | ||||

| Health Equity Initiative Participant | |||||

| Yes | – | 9 | 11% | 53 | 32% |

| No | – | 71 | 89% | 114 | 68% |

| 80 | 100% | 167 | 100% | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male, 18+ | 47% | 32 | 40% | 70 | 42% |

| Female, 18+ | 53% | 47 | 59% | 96 | 57% |

| Other, 18+ | – | 1 | 1% | 1 | 1% |

| 100% | 80 | 100% | 167 | 100% | |

| Age | |||||

| 20–34 | 26% | 16 | 21% | 27 | 16% |

| 35–54 | 34% | 31 | 40% | 78 | 48% |

| 55–64 | 19% | 19 | 24% | 35 | 21% |

| 65+ | 22% | 12 | 15% | 24 | 15% |

| 100% | 78 | 100% | 164 | 100% | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| NH White | 60% | 42 | 53% | 89 | 53% |

| NH Black | 29% | 23 | 29% | 51 | 31% |

| NH Asian | 3% | 3 | 4% | 6 | 4% |

| Hispanic/Latino | 5% | 3 | 4% | 8 | 5% |

| Other/Multiracial | 3% | 9 | 11% | 13 | 8% |

| 100% | 80 | 100% | 167 | 100% | |

| Education | |||||

| Less than HS | 11% | 5 | 6% | 5 | 3% |

| HS | 28% | 8 | 10% | 8 | 5% |

| Some college | 29% | 24 | 30% | 28 | 17% |

| BA | 18% | 25 | 31% | 34 | 20% |

| Graduate degree | 13% | 18 | 23% | 92 | 55% |

| 100% | 80 | 100% | 167 | 100% | |

| HH Income | |||||

| Less than $50,000 | 54% | 33 | 46% | 39 | 26% |

| $50,000-$99,999 | 27% | 23 | 32% | 40 | 26% |

| $100,000-$149,999 | 11% | 10 | 14% | 33 | 22% |

| $150,000+ | 8% | 6 | 8% | 39 | 26% |

| 100% | 72 | 100% | 151 | 100% | |

| Party | |||||

| Democrat | 24% | 27 | 34% | 84 | 50% |

| Republican | 16% | 20 | 25% | 28 | 17% |

| Independent | 59% | 21 | 26% | 40 | 24% |

| Other | 0% | 12 | 15% | 15 | 9% |

| 100% | 80 | 100% | 167 | 100% | |

Source: Demographic data: 2010–2016 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau. Partisanship data: Cuyahoga County Board of Elections, Registered Voters Data, accessed 2018.

We developed the interview guide (Appendix A) in consultation with our racially and economically diverse Advisory Board. Given our interest in reaching a wide range of interviewees from a divergent set of backgrounds and social positions, the task of developing a viable interview guide posed unique challenges. Initially we were unsure whether the term “flourishing” would resonate meaningfully with interviewees of different levels of education, socioeconomic statuses, and racial/ethnic backgrounds, or whether members of these various groups would comfortably use the term in responding to our questions. A preliminary set of pilot interviews (n=11) allowed us to test an early version of the interview guide, identify challenges, and adapt as necessary. A key finding from this early work was the insight that “flourishing” did, indeed, resonate with interviewees of different backgrounds, even as specific understandings of the term varied.

In each interview, we sought to develop rapport and gain insight into interviewees' lifeworlds and lived experience by first inviting them to reflect on their personal biographies and key social relationships before turning to our questions about flourishing. Instead of approaching the topic in abstract terms, we asked a series of open-ended questions that took the interviewee's life experience as an anchor point, beginning with the question, “Would you describe yourself as someone who's flourishing at this point in your life? Why or why not?” After inviting interviewees to reflect on their own life through this lens, we then turned to our general questions about the top three things people need, in general, to flourish. Subsequent interview questions engaged interviewees' perspectives on their own health and what is needed to be healthy; locally salient health disparities; and broader questions of health, equity, and resource distribution. While interviews varied in length and level of detail, most interviewees seemed to appreciate the opportunity to reflect on the themes we raised through the lens of their own biographies and lived experience.

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed for analysis using Dedoose, an online mixed-methods data analysis platform (v. 8.0.35). Members of the team met regularly, often at the end of long days of multiple interviews, to share preliminary insights and impressions. After all interviews were transcribed, formal coding and data analysis proceeded in five stages: (1) writing of analytic memos for each interview; (2) index coding to divide transcripts into salient sections for deeper analysis (Deterding and Waters, 2018); (3) inductive review and iterative generation of an analytic codebook by a team of coders; (4) preliminary coding followed by discussions to achieve consensus and resolve coding discrepancies; and (5) coding of relevant interview segments. Since interviewees’ open-ended responses tended to engage multiple themes, multiple codes were applied to all participant responses. Post-interview demographic survey responses facilitated analysis of findings by participant demographics.

7. Findings

Using this ground-up research strategy, we were able to elicit everyday perspectives on flourishing from our broad sample of interviewees. As the rich interview findings reported below demonstrate, a mixed-methods research approach can illuminate the meanings and connotations of flourishing in everyday conversational contexts, and it can reveal meaningful gaps and divergences between emic and etic understandings. Overall, our findings show that psychological considerations may figure in vernacular perspectives on flourishing, but they tell just part of a deeper and more complex story that has significant implications in both the clinical and policy domains.

In our quantitative analysis, we focus on community member perspectives since this subsample (n=80) better approximates the broader county demographics than our overall sample (n=167), in which people with higher education and higher incomes are overrepresented. We begin with this quantitative analysis before turning to our interviewees’ vivid and detailed narrative reflections.

7.1. “Would you describe yourself as flourishing?”

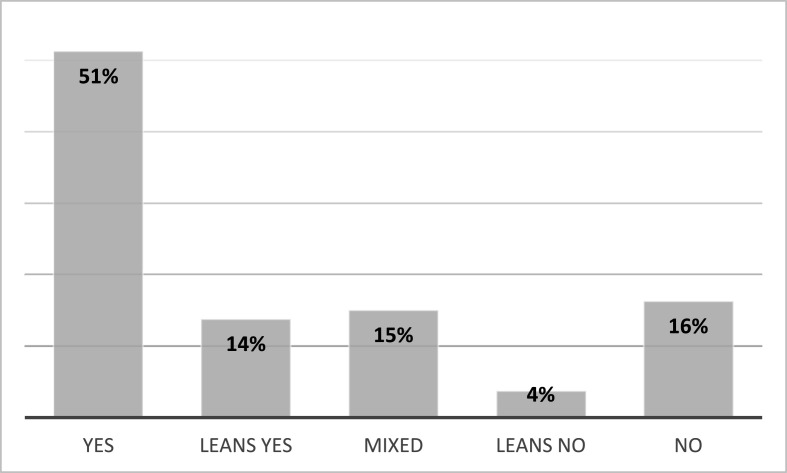

Rather than assessing interviewees’ sense of flourishing using an existing quantitative measure, we posed the open-ended question, “Would you describe yourself as flourishing?”, then coded narrative responses using a five-point scale (yes, leans yes, mixed, leans no, no). In all, interviewees’ responses leaned heavily in the positive direction. As shown in Fig. 1 , a full 51% of interviewees (41/80) described themselves affirmatively as flourishing, while 16% (13/80) told us they were not flourishing.

Fig. 1.

Community members' self-assessments of flourishing.

For many, however, self-assessments of flourishing were either mixed (15%; 12/80) or leaning in one direction or the other (an additional 18%; 14/80). All told, one third of interviewees (33%; 26/80) described themselves as neither flourishing nor the opposite, but as falling somewhere in the middle. Contra existing indexes, which provide a unitary numeric scale of flourishing, these interviewees did not necessarily see themselves as low flourishing, moderate flourishing, or high flourishing. Rather, many saw themselves as flourishing in some domains and not in others, as we elaborate in our narrative analysis below.

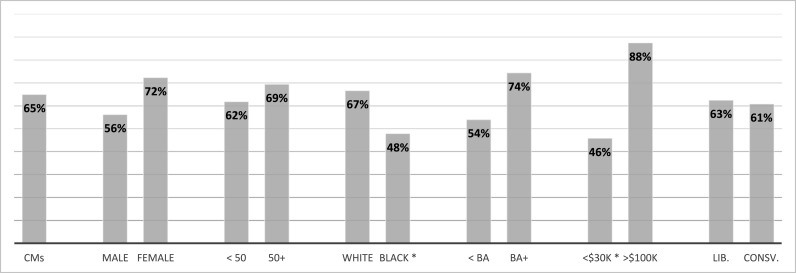

Fig. 2 examines the proportion of community members who said they were flourishing or leaned in that direction (“yes” or “leans yes” in our coding scheme) by demographic group. Women and those who were older, white, highly educated, and higher income were more likely to report flourishing. The differences by race and socioeconomic status were particularly stark. Less than half of Black interviewees reported flourishing (48%; 11/23) as compared to more than two-thirds of white interviewees (67%; 28/42). In terms of income, 88% of those with a family income over US$100,000 reported flourishing (14/16), compared with less than half of those with family earnings less than US$30,000 per year (46%; 11/24). Similarly, nearly three-quarters of those with a BA reported flourishing (74%; 32/43), as compared to just over half of those with less than a BA (54%, 20/37)—a 20 percentage point gap. Black and low-income interviewees reported lower levels of flourishing by a statistically significant margin in two-sided tests of proportions. The difference by education level also nears statistical significance (p=0.06). Differences by race and income remain statistically significant in multivariate analysis (Appendix B), providing strong evidence that flourishing is shaped by material and structural factors.

Fig. 2.

Percent Flourishing (Yes/Leans Yes) by Demographic Group

Statistically significant differences in two-sided tests of proportion are indicated with an asterisk (p < 0.05). "CMs" refers to community members in our sample.

7.2. “What do people need, in general, to flourish?”

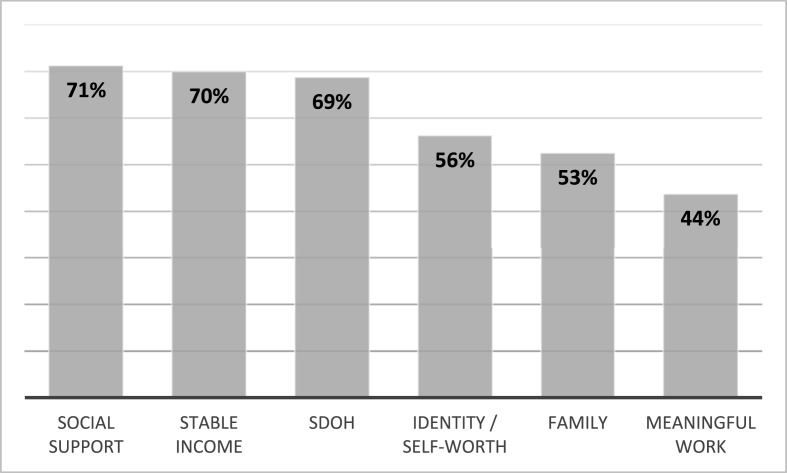

In addition to asking interviewees to explain whether or not they viewed themselves as flourishing, we also asked them to reflect in broader terms on the top three things people need, in general, to flourish. In analyzing their responses, we were especially interested in exploring comparisons to the flourishing indexes described above and in Table 1.

On this count, two of the three factors most commonly mentioned by our interviewees—a stable income and the social determinants of health (SDoH)—focused explicitly on structural and material considerations. We defined SDoH (generally understood to encompass the political and social circumstances in which people live, work, play, and pray (CSDH, 2008; Yearby, 2020)) to include access to food, housing, transportation, and education; neighborhood and physical environment; sense of safety; government institutions; exposure to the police/justice system; discrimination; and structural oppression.

Fig. 3 displays the factors most frequently identified by the community members in our sample. Five factors were mentioned by over half: social support (71%; 57/80), having a stable source of income (70%; 56/80), SDoH (69%; 55/80), a sense of identity and self-worth (56%; 45/80), and family (53%; 42/80). A sixth prevalent factor, as we discuss below, was meaningful work (44%; 35/80).

Fig. 3.

Top Factors Affecting Flourishing

Top factors identified by interviewees as important for flourishing, by percent of interviewees who mentioned each one.

How do these findings correspond to prevailing flourishing indexes? Since we used an inductive coding strategy, some factors identified in Fig. 3 resonate with, but do not correspond directly to, elements of the six indexes outlined in Table 1. Those six indexes involve considerable variation, but two factors remain constant: “close” or “positive relationships,” and “meaning and purpose.” In addition, “self-acceptance”/“self-esteem,” “engagement” (absorption or “flow”), and “positive emotion” appear in four of the six. Among our community member sample, factors related to “close relationships” were mentioned by a substantial majority, and factors related to “self-acceptance” were mentioned by just over half. Other factors common to the indexes, however, were less evident in interviewees’ understandings of flourishing.

“Close” or “positive relationships” are variably defined in different indexes but tend to involve experiences of warmth, trust, satisfaction, or contentment, or a sense of feeling respected, cared for, or loved. This cluster of sentiments is captured in our analysis using two different codes. “Social support” captured interviewees' sense of feeling valued, appreciated, needed, or loved by non-family members (i.e., friends, mentors, colleagues, neighbors, or community members), and the “family” code was applied when similar sentiments were mentioned in relation to family members, including intimate partners. More than two-thirds of community members (71%) identified social support from people outside of one's family as a key factor affecting flourishing, 53% mentioned family, and many mentioned both.

Likewise, more than half of community members (56%) spoke of a strong sense of identity or self-worth as central to flourishing. In our coding scheme, this code corresponded roughly to “self-acceptance” and “self-esteem” (typically defined as generally feeling “very positive” about oneself) in four of the indexes described above.

Our sample was less likely to point to “meaning and purpose” as central to flourishing. Among community members, only 28% (22/80) explicitly mentioned a sense of purpose, although some mentioned potentially related factors. Just under half of community members (44%) identified meaningful work as essential for flourishing, and just over a third (34%; 27/80) pointed to the importance of religion or spirituality. The remaining two factors included in several flourishing indexes—“engagement” and “positive emotion”—had no clear equivalent in our inductive coding scheme because they did not emerge in participants' discussions of flourishing.

In sum, of the top six factors identified by our diverse sample of Midwestern Americans, four correspond in some respects to existing indexes of flourishing. The other two—a stable income and SDoH, each mentioned by well over two-thirds of community members (71% and 69% respectively)—are almost completely absent from existing indexes. Notably, these factors are entirely absent from the indexes in Table 1, save for one that mentions a correlate of “stable income” (“financial security”)—but only as an optional, add-on component (VanderWeele, 2017).

7.3. Narrative perspectives on flourishing

Not only does this mixed-methods strategy help identify notable differences between “etic” and “emic” conceptions of flourishing, but it also sheds much-needed light on the texture and nuance of individual people's everyday understandings and self-assessments.

In the open-ended narratives presented below, we learn how our interlocutors think both with and about flourishing. We hear them refine their definitions in the flow of thought and speech, and parse its applicability—for instance by noting its presence in some areas of life and absence from others. In addition, we hear how flourishing can be reckoned relationally, for instance when people compare themselves to others, or to themselves at another point in time.

Our interviewees’ reflections support our overall claim about the central importance of structural and material factors in everyday perspectives on what flourishing means and on who does, or does not, have a fair shot at a flourishing life. People whose lives are constrained by social disadvantage raise these points with particular clarity and force. Their narrative perspectives further bolster the claim that the blind spots identified here are not just epistemologically important, but also deeply relevant for real people in everyday settings—and, by implication, for both clinical and policy-oriented efforts to promote flourishing.

7.3.1. Flourish: A verb and a metaphor

For most of our interviewees, flourishing is a verb—it refers to something dynamic, aspirational, and frequently elusive. Many described the pursuit of flourishing as a process of searching and striving, either in general or in relation to specific goals that must be articulated before they can be pursued.

For instance, a Black Latina college student in her 20s expressed gratitude at having the chance to study at a four-year college, which is now helping her figure out how “to achieve my end goal.” She elaborated: “my definition of flourishing would be feeling that active progress, that active change towards something bigger.” Others similarly described flourishing in terms of learning, growing, and undergoing personal change. A white woman in her 50s told us, “I've floundered before [laughs]. But … I think as long as you continue to grow in your life, no matter what capacity that's in, then you're flourishing.” Similarly, a Black professional woman in her 50s, characterized flourishing as “always reinventing myself.”

In addition to a consistent emphasis on flourishing as a verb, some interviewees evoked dynamic metaphors, including metaphors of a journey with a long time horizon, or with ups and downs. For a white professional woman in her 60s, “it's a wave, and sometimes you go through peaks and valleys, and so you kind of have to try to ride the wave, and readjust, and stay creative as you go through the waves.”

An Asian American woman in her 20s who was in recovery from an eating disorder offered a very different metaphor. She explained, “when I think of flourishing and thriving, I don't necessarily think of … a huge beautiful garden where it has all these flowers …. To me it's like that one patch of soil that I was able to grow my one flower. And that to me is flourishing. Period. Like it doesn't have to be a whole thing. … the fact that I'm alive, and I'm grateful, is what makes me feel like I'm thriving.”

Growth as a result of overcoming adversity was a common theme for other interviewees as well. A Black professional in her 50s, for instance, explained that she can flourish now having worked through earlier life struggles, including growing up in a financially unstable single-parent home and extricating herself from an unsuccessful first marriage. Now, she finds meaning and purpose in the opportunity to cultivate relationships: “relationships are what's most important to me. Not my professional career. … At my church I am one of three facilitators of a teen girls group … Never thought that I would really like it. I kind of started out doing it because there was a need. But oh my gosh. I love it! … What can I pour into others, and what can others pour into me? And how can I help somebody grow, and … how can they help me grow?” Many interviewees spoke in similar ways about the degree to which flourishing depends not only on the presence or absence of relationships, but also on relational dynamics of interdependence and mutual obligation (see also Cele, et al., 2021).

For some of our interviewees, the pursuit of flourishing has an aspirational quality—a recognition of what's been accomplished, paired with a hopeful sense that more effort, and likely more satisfaction, lie ahead. For others, the dynamic nature of flourishing has a darker cast, evoking reflection on unmet goals, past experiences that prove difficult to overcome, or a sense that one's dreams lie out of reach, often for reasons beyond one's control.

7.3.2. “Yes, and no”: When self-assessments are mixed

A majority of community members we interviewed made it clear that they either were flourishing (51%) or were not (16%), but a full third (33%) offered a mixed assessment. Our qualitative methodology enabled us to interpret these mixed assessments and recognize that most were flourishing in some respects, but not others. For some, a mixed assessment reflected a sense of being midway on their life journey, still working toward key goals. When we asked a Latino student in his 20s whether he is flourishing, for instance, he said, “yes, and no. I think yes, in the sense that I've accomplished many things and I've gotten to where I am now …. But also, no” because “there's still a lot more things that I want to achieve.”

For others, mixed assessments involved uncertainty about what flourishing would look like later in life. For example, a white man in his late 50s said, “You've asked a very good question. I mean, at my age, whether I still am flourishing, you know …. I'm really beginning to feel old [laughs]. So, can I flourish when I'm old? I don't know.” Another white man—a university faculty member in his late 40s—raised similar questions: “I think I'm doing pretty well …. If anything I'm reaching a point where I feel really stuck because all of the early goals have been achieved. And so now I'm … on the edge of receiving tenure, I'm approaching age 50. It's actually one of the things I'm addressing in therapy right now … What does aging look like for me?” His life circumstances raise other questions as well, tapping into the relational dimension noted earlier: “As a gay man who does not have contact with his family of origin, does not have children—which is normally this time of life where people become hyper focused on their families and their kids—given that I don't have that, what does aging look like for me?”

Others noted a disjuncture between how they see themselves and how others see them, or between different domains of life. A white woman in her 50s, for instance, explained that, “the world would see me as flourishing and thriving. I, myself, personally feel a lot of lack, and when I say that it doesn't mean Maslow's hierarchy of needs …. Yes, I have food, I have shelter, I have healthcare.” What's missing, for her, are “personal opportunities to do other things. Whether it's go back to school and get my master's, my doctorate, or travel somewhere by myself to do something good. I feel like I'm a little bit, I'm stuck.” In her experience, “I'm highly productive and successful, but there's very little recognition because I'm a middle-aged overweight woman. If I was a, between thirty and forty-year-old white man, it's the greatest thing in the world.”

A professionally successful Black woman in her 40s noted a similar disjuncture: “in a way I guess I am flourishing, but I always think about where I am now, and where I would like to be … So, in my mind I'm not flourishing. But if you were to ask someone else that may be on the outside looking in, maybe they would say yes.” She went on to explain that “what you're taught, at least in my culture, my little world that I grew up in—[is] that you have to be twice as good …. So, I'm always looking to ‘what else do I need to do?’”

Others pointed to a different kind of disjuncture: between the financial and the spiritual or existential domains. For example, a Latina woman in her 50s explained that she is flourishing spiritually but not financially: “my bank, my checking account don't look like it this moment, but my spirit, my mental awareness, my energy, yeah.” A white man in his 30s also pointed to finances as a major obstacle: “when I look at my life, and I see the fruits of my life, and when I see the blessings that I have … I can see that I'm flourishing. But … I'm still lacking of some type of … fulfillment.” When we asked what would need to change for him to feel fulfilled, he circled back to finances: “I'd need to make some more money and … pay off all of my debt.”

Overall, these nuanced perspectives reveal mixed experiences of flourishing—in one area of life but not another, outwardly but not inwardly, or in relation to the progression of the life course—that are vitally important, but poorly captured, if at all, by existing aggregate indexes.

7.4. How structure matters

Once again, our interview findings also highlight the vital importance of structural and material factors for individual and collective capacities to flourish. Below, we concentrate on two such factors: (1) income and other SDoH, and (2) the toxic role of racism in impeding opportunities to flourish, even for people of color who experience social advantage in other domains.

7.4.1. A steady income and other social determinants of health

A full 70% of the community members we interviewed pointed to a stable income as a key factor influencing one's capacity to flourish. For one Black man in his 60s, what's most needed to flourish is, “A job with a living wage! … In my mind, if you can't make at least 15 dollars an hour? You poor! … It impacts everything you do, okay? If you working and you can just pay your utilities … you can barely put food on the table, and you can't do anything else? You're poor!”

In addition to a steady (and livable) income, interviewees also were quick to point to other SDoH as bearing heavily on whether or not one can flourish. A few interviewees mentioned just a single factor (for instance, education), but 44% of community members mentioned more than one, and a quarter mentioned three or more.

We can hear how tightly structural and material considerations are entwined in the narrative of a Latina woman in her 50s. For her, flourishing starts with having “a healthy home,”

Because your home is your sanctuary …. But if you have a home that's falling apart, … that's infested with roaches, and mold, and, and lead, and … water coming in, and then after you've worked so hard, and then you come home and you just want to rest, and then you're like oh I don't have food, and, … it's raining; oh now we got to put you know, buckets here …. there we go, mice again. … you cannot rest … So now your health is going out of whack. You get depressed, mental issues. Violence, because you're angry …. because Ah! Why do I have to live life like this? And Ah! Why can't I pay for this? Why can't I get—why can't the landlord fix this? … So you're not being a good mom because you're angry. So you didn't even want to talk to your kids … you didn't want to cook … So then you're eating unhealthy. So you're creating all these negative environments. So it's mental health, stress, …so you cannot give 100% at home. So if you cannot give 100% at home, you cannot give 100% to work, and you cannot give 100% to social life, and you have no friends, because you're so angry nobody wants to talk to you. So for me, it's very important that you have a healthy home.

Three-quarters (75%) of low income and over two-thirds (69%) of high income interviewees mentioned one or more SDoH as having a significant impact on the ability to flourish. Again, the overwhelming importance of these factors in interviewees’ narratives stands in stark contrast to their almost total absence from leading flourishing indexes.

Lack of access to the SDoH can impede flourishing in a wide range of ways. Many interviewees described how their own capacity to flourish was harmed by exposure to serious mental or physical illness, substance dependence, incarceration, debt, prolonged unemployment, homelessness, or the death of a close relative. Often forms of adversity co-occurred, especially among people already experiencing one or more forms of social disadvantage. For instance, a Black man in his 30s who had experienced mental illness, incarceration, homelessness, and substance dependence described himself in vivid terms as “a dying rose bush, in the middle of the summer, in the middle of the desert, in Pasadena, California.” He pointed to his “rough background” as impeding his ability to flourish: “either jail, the grave, or just … lost. A lost cause …. That's honestly the path I was on growing up.” Now, he explained, he is “nowhere near … where I need to be, in life.”

7.4.2. Racism as obstacle to flourishing

Another key theme was the negative impact of racism in all its forms (structural, institutional, interpersonal, internalized (Yearby et al., 2020))—even among people with high incomes and postgraduate degrees. Multivariate analysis presented in Appendix B underscores this finding: Even holding other factors like income constant, Black interviewees reported lower levels of flourishing.

For example, a successful Black woman in her 40s holding a position of professional leadership said, “I think I'm better [off] than most African Americans …. There's always a limiting factor at work, or in society period. But on paper I'm thriving. But it's such a … heavy lift every day.” She described a conversation about the interpersonal racism she has grown accustomed to experiencing at work:

I count backwards when someone disrespects me … I try to take my mind off of it …. You have to have strategies all day long. So you don't offend anybody. But someone's offending you all day long. … it's exhausting. … It's like chess …. I have to be thoughtful ... what is the impact for people who don't have a voice and I'm at the table? So that's a very heavy weight to carry. … for many of my friends, and people who are … in a position to have some kind of … It's daunting, it's a heavy lift, and … you're stressed out all the time ….. because you're carrying the weight of … I have to speak for people without a voice.

Another interviewee, a Black professional in his 60s, raised similar themes, speaking with pride about his own professional successes while flagging major gaps between Black and white people in his social circles. “It's interesting,” he said,

because socially I interact with a lot of folks. And I would say that 99% of my non-African American friends are flourishing and thriving. I mean, at the top level of whatever you consider success. Whether it's income, … where they live—you know, all of that. My African American friends, equally as educated … aren't thriving. Aren't thriving. We just struggle with simple things, you know, where we live, and career opportunities …. When I bring my two groups of friends together? All of my white friends are amazed at how well educated, and the kinds of jobs, and things—but you can just see there's just a total difference. I mean, there's a difference between, you know, owning a house that's $140,000, and they're owning homes that are a million dollars, and putting [away] another half a million, like it's just so simple and easy. And you look and you're like ‘wait a minute? What happened here, what happened here?’ It could be choice, it could be decision, but I just think it's been opportunity.

Another, much younger Black professional (in his 30s) went beyond observing such differences to explain that the sweetness of his own success is diminished by the structural disadvantage faced by others in his community: “I find it hard to flourish and thrive in the face of, like, agony and misery of my folks … There's an intrinsic responsibility that I feel to others.” He offered an analogy: It's like you “arrive at a status of spiking the football at the 50-yard line and say ‘I feel great. This is amazing! I'm thriving!’ You look around and you see actually you are contributing to the same inequity that you're looking to face on a daily basis.”

The accounts of these successful Black professionals provide especially clear evidence of the degree to which structure, power, and historical injustice affect the capacity to flourish. While all suggest that their achievements mean that they should be flourishing, racism and discrimination nonetheless impede both their own capacity to flourish and that of people who share their racial background and life circumstances. For them, flourishing is clearly an active pursuit—and despite clear advantages, they too struggle, with many cards stacked against them. The strong relational stakes and implications of these struggles further remind us that flourishing is far more than just a solo psychological concern.

8. Discussion

As critical social scientists of health, we are struck by the degree to which human flourishing has garnered scholarly attention, and we are enthusiastic about possibilities for interdisciplinary dialogue about what flourishing means, how it can be investigated, and how it can be promoted at the individual and community levels. Such interdisciplinary discussion is especially timely now, as interest in flourishing gains traction in public and policy conversations—and as it attracts levels of research investment that suggest it will figure centrally in discussions of mental health, and health more generally, for the foreseeable future. The parallel rise in focus on “well-being” (Diener, 2009; Plough, 2018; Plough, 2020; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018; Yetton et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2021)—and, importantly, the persistent slippage between the two terms (Willen, 2022)—only heighten the importance of “Scrutinizing the terms we use” (Fassin & Das, 2021: 6) and carving out space for robust interdisciplinary dialogue.

It is with these goals and challenges in mind that we have sought in this paper to interrogate the old-new concept of flourishing and foreground blind spots in the current research landscape—blind spots whose implications become evident through analysis of our mixed-methods findings. First, our findings provide clear evidence that people facing disadvantage—especially disadvantages associated with income, educational attainment, and race/ethnicity—report lower levels of flourishing than those who do not. Furthermore, our diverse sample of Midwestern U.S. interviewees helps us see, in vivid detail, how opportunities to flourish are indeed “profoundly influenced by the surrounding contexts of people's lives” (Ryff & Singer, 2008: 14)—including structural and material factors such as a stable income and access to the social determinants of good health that are almost entirely absent from most leading approaches to flourishing.

Additionally, our findings show how relational dynamics can have a powerful impact on the capacity to flourish, especially when structural, material, or political constraints make it difficult or even impossible to follow through on defining moral obligations and interpersonal commitments. This complexity is evident, for instance, among Black interviewees with successful careers who describe how substantive advantages such as higher education, high income, and professional success have nonetheless failed to protect them from the negative impact of institutional, interpersonal, and even internalized racism.

Given all we now know about the manifold health effects of inequity and injustice, these detrimental consequences for individual and collective opportunities to flourish come as no surprise. What is surprising—and what we want to emphasize here—is the persistent, and problematic, inattention to these issues in most research on flourishing. From a population health standpoint, there is no doubt that leading approaches to flourishing play an important role in facilitating comparison across large groups, with significant clinical and policy effects. But what do we learn—and what do we miss—when we draw comparisons in the aggregate using indexes that may miss vital aspects of what real people, in real-world settings, view as necessary to flourish? Whose flourishing are existing indexes designed to measure, improve and advance—and whose might be less well captured, or not captured at all?

By raising these questions, we are not proposing the wholesale replacement of quantitative measures with qualitative approaches. Neither do we mean to suggest that flourishing depends solely on the structural, material, or political circumstances of people's lives to the exclusion of psychological factors. Rather, we aim to carve out space for interdisciplinary dialogue that can span divergent epistemological assumptions, methodological approaches, and practical goals and, ultimately, that can bring us closer to an understanding of flourishing that can help “reframe and reimagine traditional concepts of health”—specifically, in a way that bends toward justice.

9. Limitations

For various reasons, we must exercise caution in interpreting the findings reported here. Despite the internal diversity within our sample, all of our interviewees live within a single metro area in the Midwestern U.S. Given the design of our larger study, individuals with higher incomes and education are overrepresented in the qualitative findings. Still, the patterns described here provide valuable insight into everyday, vernacular understandings of flourishing.

10. Conclusion

Whether one is motivated principally by the goal of improving mental health care; replacing deficit-oriented frameworks with assets-based or salutogenic approaches (Antonovsky, 1996); or conceiving new strategies for global health promotion, the critiques presented here merit serious consideration from all researchers, clinicians, policymakers, and funders who are interested in human flourishing.

While a focus on flourishing may indeed “open a national conversation” around “traditional concepts of health” (VanderWeele et al., 2019), we caution against simply rallying behind current efforts to promote flourishing because of the term's positive, holistic associations and widespread appeal. Before we can lift up flourishing as the answer, we must first clarify the question by subjecting the concept itself to deeper comparative scrutiny—and, moreover, by having a robust interdisciplinary conversation about what is wrong with “traditional concepts of health” in the first place.

This proposal brings us back full circle to the New York Times series on flourishing that appeared near an early peak in the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. Given the vast structural inequities in health and, arguably, flourishing that have only deepened during the pandemic, it is now clearer than ever that the problems with “traditional concepts of health” are not primarily in our minds. While simple “do-it-yourself” flourishing exercises may help some people in a limited way, as a society-wide strategy for promoting human flourishing, they clearly will not do. If flourishing is fundamentally a matter of being able to realize one's potential, as Aristotle among others have argued (Garland-Thomson, 2019, Ryan & Deci, 2001, Ryff, 1989, Willen, 2022), then we cannot ignore the fact that people are—and inevitably will be—hard-pressed to reach their potential in environments of scarcity or risk, oppression, misrecognition, or violence. Without confronting these critical insights head-on, efforts to promote flourishing will inevitably miss the mark.

Funding

Support for this research was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Grant No. 74898). The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation.

Declaration of interests

☒ The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

☐The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply grateful to our research participants; to the ARCHES Advisory Board; to the leadership of Health Improvement Partnership-Cuyahoga (HIP-Cuyahoga), especially Gregory Brown, Heidi Gullett, Martha Halko, and Marilyn Burns; to ARCHES research team members Heide Castañeda, Erica N. Chambers, Ronnie Dunn, Katherine Mason, and Ruqaiijah Yearby; to Richard Sosis; and to Emily Mendenhall. We also are indebted to research assistants Aditi Deshmukh, Isabella Dresser, Yuliya Faryna, Jolee Fernandez, Anne Kohler, John Lawson, Anneke Nyary Levine, Noor Malik, Olivia Painchaud, Brenda Piedras, Julia Tempesta, Serena Thadani, Shayna Thomas, Mary Tursi, Lucy Pereira, and Brooke Williams.

Footnotes

At the time of submission, Hone and colleagues' 2014 paper had been cited 365 times according to Google Scholar. Of the four models they compare, the paper by Keyes had accumulated 4,304 cites; Huppert and So 1,427 cites; Diener et al. 3,105 cites; and Seligman 8,468 cites. Of the two models we add to theirs in Table 1, Ryff and Singer's paper has 3,220 cites, and the more recent VanderWeele piece from 2017 just 249 — although it bears mention that he is a PI of the Global Flourishing Study, a US$43 million, 22-country initiative that aspires to include 240,000 participants (Institute for the Study of Religion, Baylor University, 2021).

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100057.

Appendices A and B. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Interview Guide for ARCHES | the AmeRicans’ Conceptions of Health Equity Study.

Multivariate Regression Results.

References

- Agenor C., Conner N., Aroian K. Flourishing: An evolutionary concept analysis. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2017;38(11):915–923. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2017.1355945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promotion International. 1996;11(1):11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey Z.D., Krieger N., Agénor M., Graves J., Linos N., Bassett M.T. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. The Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfer E.A., et al. Health justice: A framework (and call to action) for the elimination of health inequity and social injustice. Am Univ Law Rev. 2015;65(2):275–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfer E.A., Mohapatra S., Wiley L.F., Yearby R. Social Science Research Network; Rochester, NY: 2020. Health Justice Strategies to Combat the Pandemic: Eliminating Discrimination, Poverty, and Health Inequity During and After COVID-19.https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3636975 Report No.: ID 3636975. [Google Scholar]

- Bethell C.D., Gombojav N., Whitaker R.C. Family resilience and connection promote flourishing among US children. Even Amid Adversity. Health Affairs. 2019;38(5):729–737. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum D. New York Times. May 4; 2021. The Other Side of Languishing Is Flourishing. Here’s How to Get There.https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/04/well/mind/flourishing-languishing.html [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. We’re not all in this together: On COVID-19, intersectionality, and structural inequality. American Journal of Public Health. 2020;110(7):917. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd R.W. Police violence and the built harm of structural racism. The Lancet. 2018;392(10144):258–259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31374-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P.A., Kumanyika S., Fielding J., LaVeist T., Borrell L.N., Manderscheid R., et al. Health disparities and health equity: The issue is justice. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(S1):S149–S155. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks F., Kendall S. Making sense of assets: What can an assets based approach offer public health? Critical Public Health. 2013;23(2):127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Burke N.J., Hellman J.L., Scott B.G., Weems C.F., Carrion V.G. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on an urban pediatric population. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2011;35(6):408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cele L., Willen S.S., Dhanuka M., Mendenhall E. Ukuphumelela: Flourishing and the pursuit of a good life, and good health in Soweto, South Africa. SSM–Mental Health. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Kubzansky L.D., VanderWeele T.J. Parental warmth and flourishing in mid-life. Social Science & Medicine. 2019;220:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commission on the Social Determinants of Health . Final report of the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1 [Google Scholar]

- Deterding N.M., Waters M.C. Flexible coding of in-depth interviews: A twenty-first-century approach. Sociological Methods & Research. 2018;50(2):708–739. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. In: Social indicators research series. Michalos A.C., editor. Vol. 37. Springer Netherlands; Dordrecht: 2009. The science of well-being.http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-90-481-2350-6 [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Wirtz D., Tov W., Kim-Prieto C., Choi D., Oishi S., et al. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research. 2010;97(2):143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Fassin D., Das V. In: Words and worlds: A lexicon for dark times. Das V., Fassin D., editors. Duke University Press; Durham: 2021. Introduction: From words to worlds. [Google Scholar]

- Garland-Thomson R. In: Human flourishing in an age of gene editing. Parens E., Johnston J., editors. Oxford University Press; New York: 2019. Welcoming the unexpected. [Google Scholar]

- Geeraert J. Sick and vulnerable migrants in French public hospitals. The administrative and budgetary dimension of un/deservingness. Social Policy and Society. 2021;20(3):487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus A.T., Hicken M., Keene D., Bound J. “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(5):826–833. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant A. New York Times. Apr 19; 2021. There’s a Name for the Blah You’re Feeling: It’s Called Languishing.https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/19/well/mind/covid-mental-health-languishing.html [Google Scholar]

- Halko M., Brown G. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine; Washington, DC: 2016. Session 1: Halko & Brown. Health and Medicine Division.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TdlB1PcFJmc&t=944s [Google Scholar]

- Healthy Northeast Ohio . Sharing Knowledge to Create Healthier Communities. 2021. http://www.healthyneo.org/indicators/index/indicatorsearch?doSearch=1&grouping=1&subgrouping=1&ordering=1&resultsPerPage=150&l=2112&showSubgroups=0&showOnlySelectedSubgroups=1&primaryTopicOnly=0&sortcomp=0&sortcompIncludeMissing=0&showOnlySelectedComparis [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt J. Just healthcare and human flourishing: Why resource allocation is not just enough. Nursing Ethics. 2019;26(2):405–417. doi: 10.1177/0969733017707010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicken M.T., Kravitz-Wirz N., Durkee M., Jackson J.S. Racial inequalities in health: Framing future research. Social Science & Medicine. 2018;199:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E.A., O'Connor R.C., Perry V.H., Tracey I., Wessely S., Arseneault L., et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes S.M., Castañeda E., Geeraert J., Castaneda H., Probst U., Zeldes N., et al. Deservingness: Migration and health in social context. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(Suppl 1) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hone L., Jarden A., Schofield G.M. Psychometric properties of the Flourishing Scale in a New Zealand sample. Social Indicators Research. 2014;119(2):1031–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Hone L., Jarden A., Schofield G.M., Duncan S. Measuring flourishing: The impact of operational definitions on the prevalence of high levels of wellbeing. Intnl J Wellbeing. 2014;4(1) [Google Scholar]

- Huppert F.A., So T.T.C. Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Social Indicators Research. 2013;110(3):837–861. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9966-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huschke S. Performing deservingness: Humanitarian health care provision for migrants in Germany. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;120:352–359. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for the Study of Religion, Baylor University . Baylor University; 2021. Global Flourishing Study Launch.https://www.baylorisr.org/programs-research/global-flourishing-study/ [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M., Lee Williams J. COVID-19 mitigation policies and psychological distress in young adults. SSM - Mental Health. 2021:100027. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings B. In: Human flourishing in an age of gene editing. Parens E., Johnston J., editors. Oxford University Press; New York: 2019. Bioethics contra biopower: Ecological humanism and flourishing life. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes C.L.M. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43(2):207–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kickbusch I. The political determinants of health--10 years on. BMJ. 2015;350(2):h81. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h81. h81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]