Abstract

WC–Co based alloys are widely applied cemented carbide materials due to unique and outstanding properties. In this study, a series of WC–6Co cemented carbides are quickly prepared via SPS and the effects of Zr2O3-7 wt% Y2O3(YSZ) on the properties of the as-prepared samples are also investigated. The results show that with the increase of the YSZ amount, the density, flexural strength and fracture toughness of the samples were particularly improved to a certain extent, but the Vickers hardness was slightly reduced. Combined with the evolution of microstructure and analysis of property changes, it can be speculated that the mechanism of YSZ additive promoting sintering can be attributed to the formation of solid solution and subsequent activation sintering process. Consequently, YSZ was preliminarily proved to be a potential enhancer for the WC–Co based cemented carbides.

WC–Co based alloys are widely applied cemented carbide materials due to unique and outstanding properties.

1. Introduction

In the field of cemented carbides, WC-based cemented carbides have attracted much attention due to excellent mechanical properties, outstanding friction properties, stable high-temperature behaviour, and good corrosion resistance.1–3 The WC-based cemented carbides, at the same time, are also the most intensively studied and most widely used type of cemented carbide and has been successfully applied in the fields of cutting tools, automobiles, civil engineering, and machinery, etc.4–8 WC is a refractory alloy, which requires an ultrahigh sintering temperature to achieve sintering and densification process, so a certain amount of binder phase is usually added to promote the sintering process. Basically, based on the difference of the binding phase, WC-based cemented carbides are mainly divided into several categories of WC–Co, WC–Ni, WC–Co/Ni–TiC, WC–Co/Ni–Fe.9–14 Among them, the WC–Co cemented carbide is the most popular and best-developed ones. Although in recent years, Ni, Fe and other binder phases have gradually received attention, they still have some shortcomings that are currently difficult to overcome. For example, when Ni is used as the binder phase, it is very difficult to grind the powders fully uniformly during the ball milling process, resulting in nickel-pool defects on the sample surfaces after sintering. In addition, when Fe is used as the binder phase, a certain amount of brittle intermetallic will form, which seriously affects the mechanical properties of the material. Moreover, when adding the same amount of binder phase, the sample with Co added has the highest degree of bond strengthening and the best overall performance.11,15 So, the WC–Co cemented carbide is still one of the mainstream choices on the laboratory and market until now.

However, although the presence of the binder phase can effectively reduce the sintering temperature of WC, due to its generally low melting point, the mechanical properties of the final prepared sample are relatively poor. Furthermore, when the addition amount of binder phase is too high, the thermal and mechanical properties of the final prepared sample will be seriously influenced. Therefore, the current research to improve the performance of WC–Co cemented carbide mainly focuses on two aspects. One is to choose more advanced preparation methods, such as vacuum sintering, hot pressing sintering, microwave sintering, hot isostatic pressing sintering (HIP), spark plasma sintering (SPS).5,10,11,16 Among them, the most promising is SPS. Compared with the traditional sintering process, SPS can obtain higher density at a lower sintering temperature, and the soaking time is greatly reduced, which only needs a few minutes during the densification stage.17,18 The other is to inhibit the abnormal growth of WC grains by adding a second phase, or to form a second reinforced phase to achieve the dispersion strengthening effect. For instance, adding a small amount of rare earth elements triggers the solid solution strengthening effect.19 Or adding some carbides effectively inhibits the abnormal growth of WC grains.20 As an effective toughening approach, yttria stabilized zirconia (YSZ) is widely used to toughen alumina and other refractory ceramics, and greatly improve the toughness of the material.21,22 A large number of related references have fully confirmed the effectiveness of YSZ as a toughening phase, such as high melting point, good corrosion resistance, and unique transformation toughening effect.23,24 However, up to now, there have been few research papers on the modifying WC–Co cemented carbide by YSZ transformation toughening.

In this work, in order to solve the existing disadvantages of the WC–Co cemented carbides, such as poor efficiency and underdeveloped preparation technology, and further improve the overall performance of WC–Co cemented carbides, a series of WC–6Co cemented carbides have been successfully prepared using WC–6Co and YSZ separately as the main raw material and additive by SPS technology. In addition, the effects of YSZ addition on the microstructure, density and mechanical properties of the prepared WC–6Co cemented carbide were studied in detail.

2. Experimental

2.1. Raw materials and preparation process

In this work, the tungsten carbide powder (WC, D90 = 2 μm, purity ≥ 99.5%, BGRIMM Technology Group, China), cobalt powder (Co, D90 = 2 μm, purity ≥ 99.5%, BGRIMM Technology Group, China), and yttria-stabilized zirconia powder (YSZ, zirconia with 3 mol% yttria, D50 = 2 μm, purity ≥ 99.0%, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China) were chose as the starting materials.

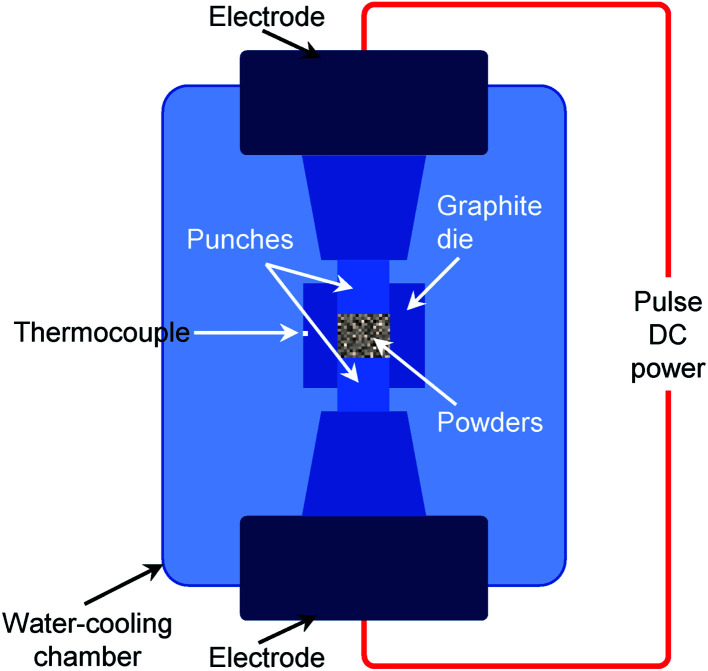

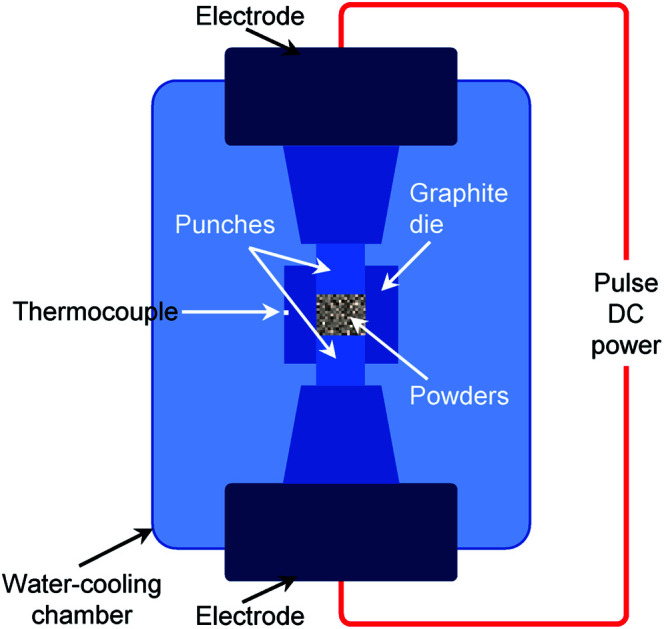

The improved WC–6Co cemented carbides were prepared with the following steps. Firstly, the starting powders were weighed according to Table 1 and seriatim put into a cemented carbide jar. The ethyl alcohol was chosen as the ball mill medium. Secondly, with the 4-to-1 of the ratio of ball-to-powder, the powders were mixed fully in a high-energy planetary ball mill (QM-3SP4, Nanjing NanDa Instrument Plant, China) for 10 h. Thirdly, the uniformly mixed powders were fully dried at 120 °C for 24 h in a drying oven to remove the ethyl alcohol. Finally, the as-prepared powders were poured into standard graphite die with an inner diameter of 15 mm, and put into an SPS furnace, and applied a sintering pressure with 50 MPa. When vacuum degree came up to 1 Pa, the powders were sintered at 1400 °C for soaking 5 min, and then cooling with the furnace to obtain the final products. Fig. 1 presents the sketch diagram of the SPS equipment.

Formulas of the specimens.

| Sample no. | WC | Co | YSZ (extra addition) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S0 | 94 | 6 | 0 |

| S1 | 94 | 6 | +3 |

| S2 | 94 | 6 | +6 |

| S3 | 94 | 6 | +9 |

| S4 | 94 | 6 | +12 |

Fig. 1. Sketch diagram of the SPS equipment.

2.2. Testing and characterization

According to China National Standard GB/T 25995-2010, the bulk density and relative density of the sample were measured by Archimedes method. The theoretical density of each batch samples was calculated based on the formulas (WC, 15.63 g cm−3; Co, 8.9 g cm−3; YSZ 6.05 g cm−3). The calculation formula of theoretical density of the composite is as follow.

| ρ = V1 × ρ1 + V2 × ρ2 + V3 × ρ3 + …… + Vxρx | 1 |

where ρ is the theoretical density, g cm−3; Vx is the volume fraction of each component and ρx is corresponding density, g cm−3.

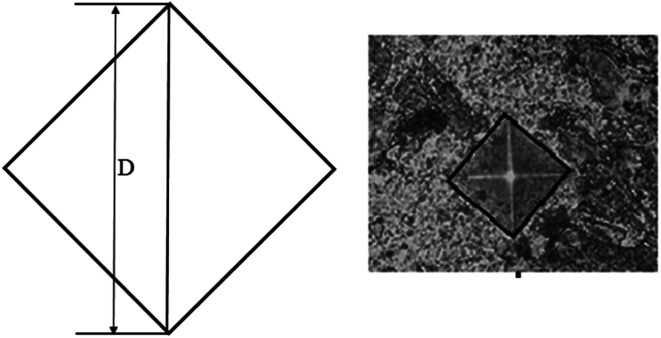

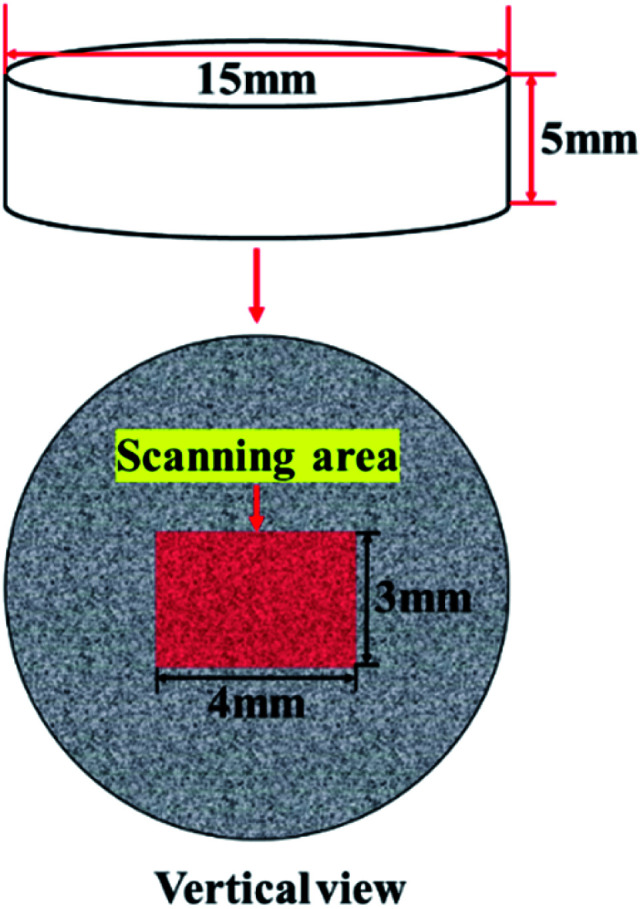

An X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Bruker D8 Advance) was used to analyze the phase composition of the samples, with a scanning angle range of 20–100° and a scanning speed of 4°·min−1. A scanning electron microscope (SEM, HTACHI SU5000) was used to observe and record the micromorphology of the sintered samples (XRD and SEM sample size shown in Fig. 2). The voltage of the scanning electron microscope is set to 15 kV, autofocus and astigmatism are eliminated, and the secondary electron or backscatter image can be observed. A universal testing machine was used to carry out the three-point bending test and to measure the flexural strength of the samples. The Vickers hardness of the samples was measured using a 402MVA™ microhardness tester with a load of 1000 gf (9.8 N) for 10 s. Select at least 5 points for each sample to carry out the test and took the average value as the final experimental value after removing the abnormal data. The calculation formula of the Vickers hardness is as follow.

| HV = 1.8544P/D2 | 2 |

where HV is Vickers hardness, kg mm−2; P is the imposed load during the test, kg; D is the length of the diagonal of indentations, mm (shown in Fig. 3).25

Fig. 2. Sample size.

Fig. 3. Vickers hardness impresses.

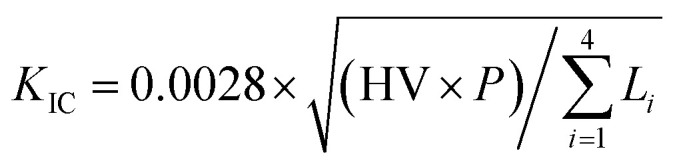

In addition, according to the international standard ISO 28079-2009, the indentation method was used to measure and calculate the fracture toughness of the samples. The calculation formula of the fracture toughness is as follow.

|

3 |

where KIC is the fracture toughness of the samples, MPa mm1/2; HV is the Vickers hardness of the samples, kg mm−2; P is imposed load during the test, N; Li is the crack length in each direction, mm.26

3. Results and discussion

3.1. XRD and SEM analyses

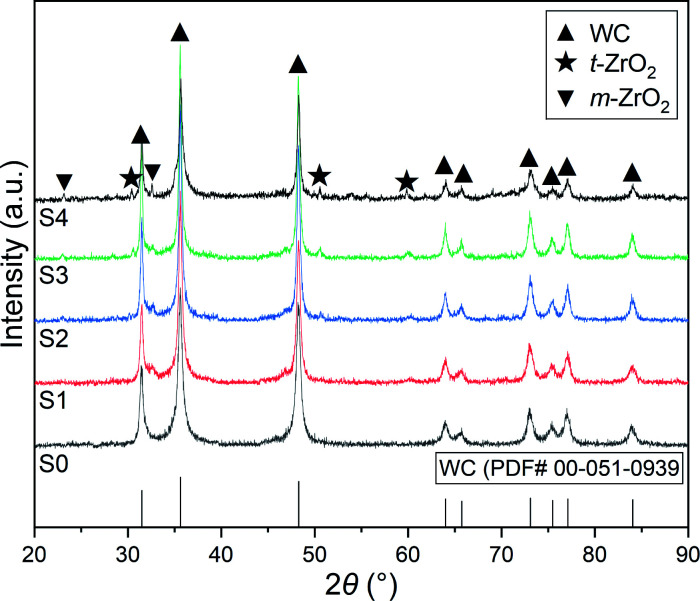

Fig. 4 shows the XRD patterns of the prepared samples with different content of YSZ. It can be seen that the sample S0 without YSZ is only detected the diffraction peaks of the WC (PDF# 00-051-0939). For the samples adding YSZ, besides the WC main phase, the diffraction peaks of the t-ZrO2 (tetragonal system, PDF# 00-017-0923) and m-ZrO2 (monoclinic system, PDF# 00-007-0343) are also detected, which shows that most of the zirconia grains still retain the tetragonal structure. Apart from this, no other impurity phases are found in the XRD patterns.

Fig. 4. XRD patterns of the prepared samples.

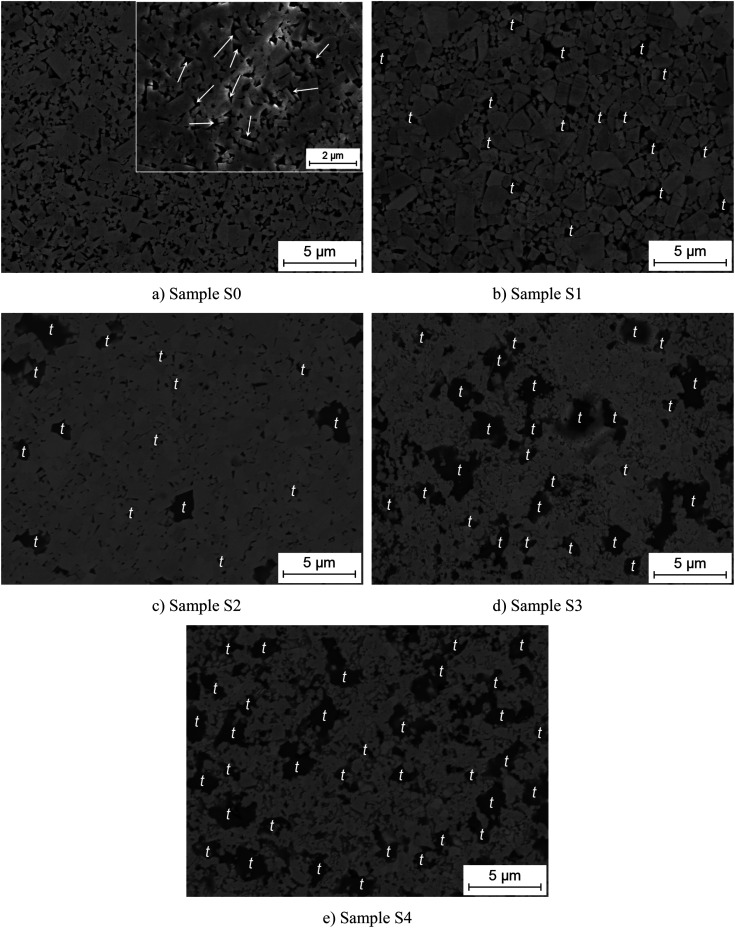

Fig. 5 presents the microstructure of the sintered samples. For the sample S0, the surface of the sample has a lot of pore defects (marked with white arrows), and the bonding between WC grains is loose; as a whole, the micromorphology of the sample without YSZ is poor. On the contrary, as the amount of YSZ added increases, the pores between WC grains gradually become smaller until they disappear. And the same time, the microstructure of samples is refined because the YSZ particles (marked with letter t) can effectively disperse and fill among the matrix grains. In addition, a trend can be seen that, from Fig. 5a (S0) to Fig. 5e (S4), the grain size of the samples decreases gradually. Overall, this result shows that on the one hand, the presence of YSZ effectively promotes the sintering process of the samples; on the other hand, it proves that the YSZ particles can trigger the pinning effect by being distributed at the grains boundaries of WC matrix, thereby inhibiting the growth of the WC grains.

Fig. 5. Microstructure images of the prepared samples.

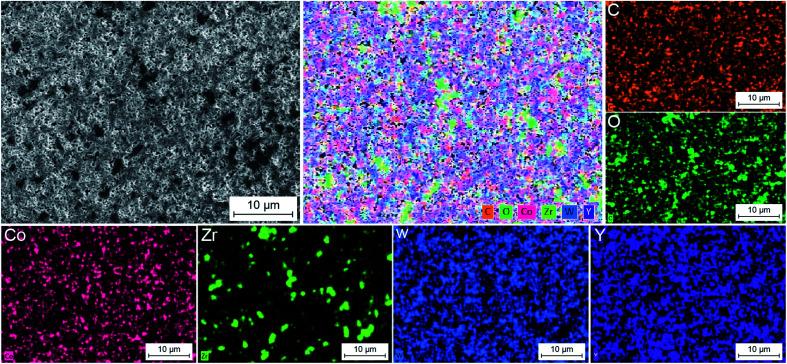

EDS systems are integrated into SEM instrument. When performing the EDS operation, the actual working distance of the sample needs to be adjusted to 10 mm, and the voltage is 15 kV. After the setting is completed, move the energy spectrum probe in to start the surface scan or dot operation. The normalized result should be close to 100%. The scanning range is 2 × 2 mm in the center of the sample, repeat three times, and analyze the result that matches the actual result. Moreover, an EDS mapping of the sample S2 is presented in Fig. 6 to demonstrate the dispersity of YSZ additive. Obviously, when 6 wt% YSZ is added, all elements (WC: W, C; YSZ: Zr, Y, O) within the samples is, uniformly dispersed, rather than forming agglomeration in partial region. This result also more intuitively proves that the degree of sintering of the samples with YSZ is much better than that of the samples without YSZ.

Fig. 6. EDS mapping of the sample S2.

3.2. Sintering characters

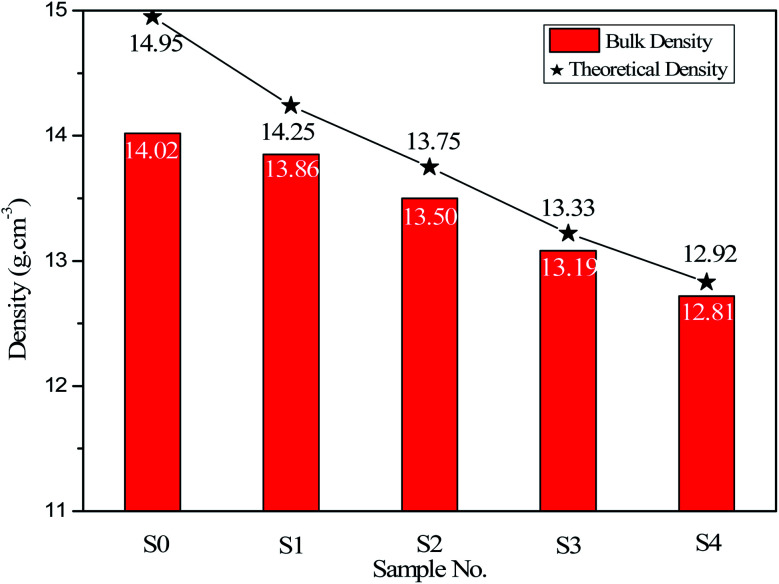

Fig. 7 shows the measured bulk density and correspondingly calculated theoretical density of the sintered samples with different YSZ contents. As the addition amount of YSZ increases, the bulk density of the samples decrease relatively, and the samples S1 (3 wt%) and S4 (12 wt%) achieve the maximum 14.25 g cm−3and minimum 12.92 g cm−3respectively. But this does not mean that the density of the samples with lower bulk density is reduced, because it can be seen that the theoretical density of the samples decreases with the increasing of the additive amount of YSZ.

Fig. 7. Bulk density and theoretical density of the prepared samples.

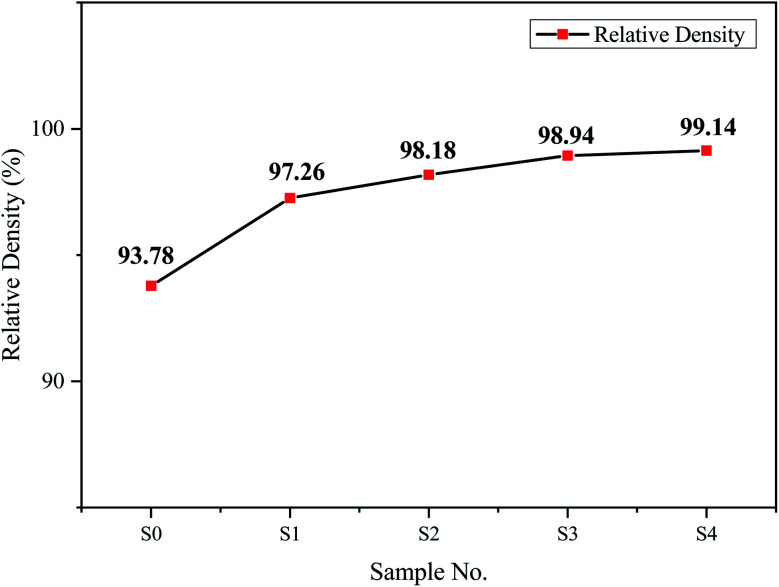

Then, the relative density of the sintered samples is measured and presented in Fig. 8 to represent the densification of different samples. Contrary with the tendency of theoretical density, the relative density of the samples is progressively increased. The relative density of the sample S0 without YSZ additive is just 93.78%, whereas the relative density samples S3 with 9 wt% and S4 with 12 wt% increases severally to 98.94% and 99.14%. When the added YSZ is 12%, the relative density of the sample reaches the maximum, indicating that the density of the test is the highest under this condition. This can be verified from Fig. 5. The surface pores of the sample S4 are the least, and the grains are combined the closest. The result is consistent with the ahead observed result of microstructure evolution of the samples. Solid solution formed by WC and second phases is believed to be the reason why the densification of WC cemented carbides is improved.27,28

Fig. 8. Relative density of the prepared samples.

3.3. Mechanical properties

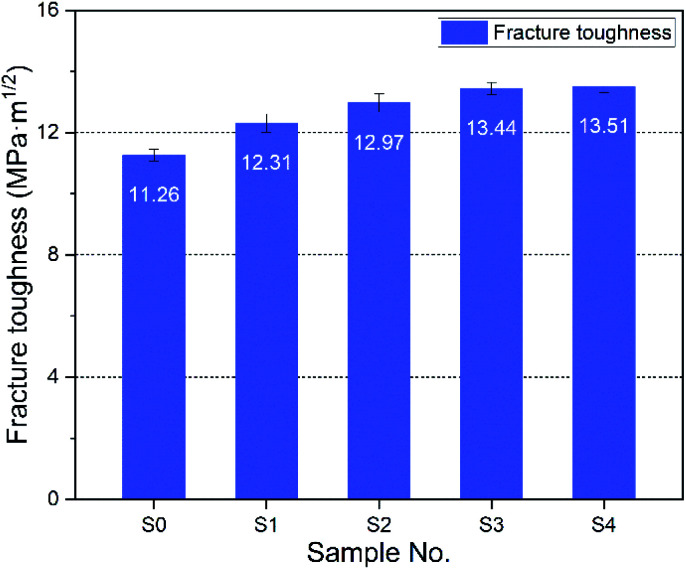

To further investigate the effects of YSZ additive on the key mechanical properties of the samples, the fracture toughness, flexural strength, and Vickers hardness of the prepared samples were tested with corresponding standards. When calculating, take the diagonal length of the indentation after S0–S4 into the formula (2) to obtain the Vickers hardness of each sample. Subsequently, the crack length Li of each vertex angle of the sample is brought into formula (3) to obtain the fracture toughness of each sample. The fracture toughness of the sintered samples is shown in Fig. 9. With adding of YSZ, the fracture toughness of the samples is obviously improved. When separately adding of 3, 6, and 9 wt% YSZ, the fracture toughness of the samples respectively increases to 12.31, 12.97, and 13.44 MPa mm1/2, while the fracture toughness of the sample S4 is just slightly increased. An approved theory is described that the fracture toughness of the matrix material enhanced by ZrO2 have a linear relationship with the number of ZrO2 particles that undergo phase transition (from t-ZrO2 to m-ZrO2) during fracture process.29 However, during the cooling process, the unsuccessfully stabilized t-ZrO2 particles will transform to m-ZrO2 with volume expansion, resulting in micro-cracks inside the matrix material. With the increase of these unstabilized particles, the number of resulting micro-cracks gradually increases as well. When the number of these micro-cracks increases to a certain extent, these micro-cracks will combine to each other to form larger cracks, and eventually lead to a decrease to the fracture toughness of the material.30 Based on the above two factors, it can be considered that when the content of YSZ exceeds 9 wt%, the fracture toughness of the prepared samples will not be further improved.

Fig. 9. Fracture toughness of the prepared samples.

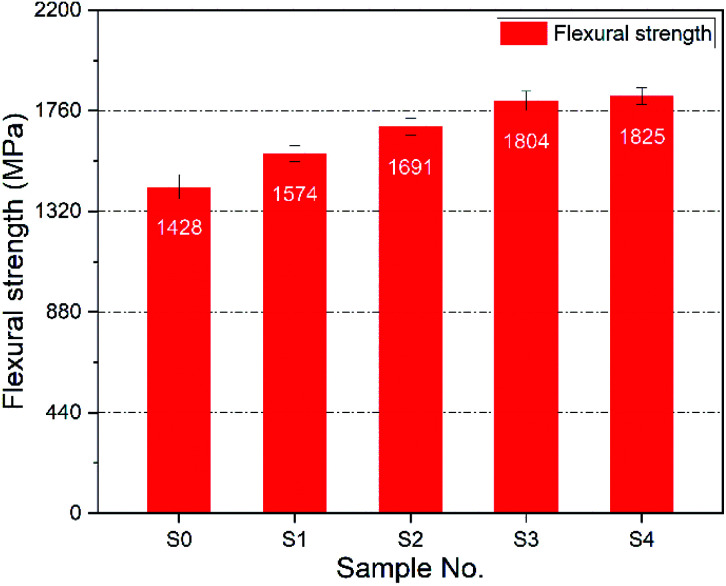

The flexural strength of the specimens showed almost the same trend as the fracture toughness. As shown in Fig. 10, the flexural strength of the samples continuously increased from 1428 to 1825 MPa. Among them, the samples S3 and S4 show higher growth rate, reaching 26.33% and 27.81% respectively. As mentioned above, the improvement of the mechanical properties of the samples should be attributed to the promotion of the YSZ additive to the sintering process of the samples. Generally, the process of material densification and grain growth is mainly controlled by the diffusion process, which means that the addition of YSZ promotes the atomic diffusion process of WC matrix.31 This also shows that the addition of YSZ will reduce the activation energy of the atomic diffusion of the material, and according to the Arrhenius diffusion equation,32 the reduction of the activation energy of diffusion will lead to the increase of the diffusion coefficient, that is, the diffusion is accelerated. In addition, it is well known that the rapid grain growth process is usually completed by grain boundary migration and occurs in the final stage of sintering.33 According to the previous analysis of the microstructure of the samples (S0–S4, shown in Fig. 5), the YSZ particles are mainly distributed at the WC grain boundaries, and the pinning effect of the YSZ particles inhibits the migration of the WC grain boundary, thereby avoiding the abnormal growth of the WC grains.

Fig. 10. Flexural strength of the prepared samples.

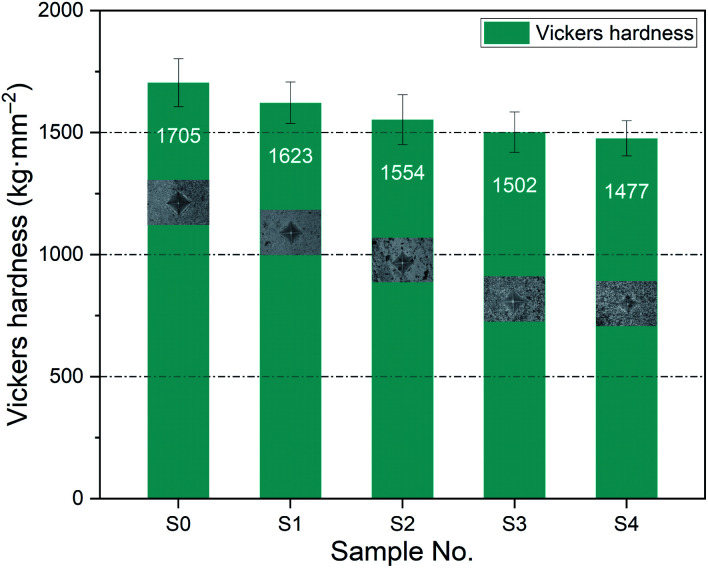

On the contrary, the Vickers hardness of the samples shows a continuous downward trend as the amount of additive added increased (shown in Fig. 11). According to Fig. 5, With the increase of YSZ content, it can be clearly seen that the proportion of YSZ phase in the micro morphology increases. The Vickers hardness of the sample S0 without YSZ is 1705 kg mm−2, while the Vickers hardness of the sample S4 adding 12 wt% YSZ is only 1477 kg mm−2. This is mainly because the intrinsic hardness of the YSZ is lower than that of the WC matrix, and the combined effect causes reduction on the hardness of the prepared samples.

Fig. 11. Vickers hardness of the prepared samples.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, in order to improve the overall performance of WC–Co cemented carbides, the YSZ content is used as a variable to conduct basic research on the micro-morphology, mechanical properties, and mechanical properties of cemented carbide.

(1) Using YSZ as an additive, a series of WC–6Co cemented carbides with good microstructure and excellent mechanical properties can be reasonably prepared by using SPS technology at 1400 °C for 5 min.

(2) As the amount of YSZ added increases (3–12%), the density, flexural strength and fracture toughness of the samples increase, but the hardness decreases slightly. The reason for the change in properties of the samples can be attributed to the addition of YSZ. Specifically, the YSZ additive can activate the sintering process by forming a solid solution with the WC matrix, resulting in improvement in the density and mechanical properties of the samples.

(3) When adding 9 wt% YSZ, the sample obtained the optimal comprehensive performance with the relative density of 98.93%, the flexural strength of 1804 MPa, the fracture toughness of 13.44 MPa mm1/2, and the Vickers hardness 1520 kg mm−2, the performance of the sample is the best at this content.

In future research, YSZ (Zr2O3-7 wt% Y2O3)was preliminarily proved to be a potential enhancer for the WC–Co based cemented carbides.

Funding

This research is financially supported by National Key R&D Program of China (No: 2017YFB0306100).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

References

- Garcia J. Cipres V. C. Blomqvist A. Bartek K. Cemented carbide microstructures: A review. Int. J. Refract. Met. H. 2019;80:40–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2018.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. W. Song X. Y. Wang H. B. Liu X. M. Tang F. W. Lu H. Complexions in WC-Co cemented carbides. Acta Mater. 2018;149:164–178. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2018.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poetschke J. Richter V. Michaelis A. Fundamentals of sintering nanoscaled binderless hardmetals. Int. J. Refract. Met. H. 2015;49:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2014.04.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Konyashin I. Farag S. Ries B. Roebuck B. WC-Co-Re cemented carbides: Structure, properties and potential applications. Int. J. Refract. Met. H. 2019;78:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2018.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yousfi M. A. Norgren S. Andrén H. O. Falk L. K. L. Chromium segregation at phase boundaries in Cr-doped WC-Co cemented carbides. Mater. Charact. 2018;144:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.matchar.2018.06.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q. M. Yang J. G. Wen Y. Zhang Q. Y. Chen L. Y. Chen H. A novel route for the synthesis of ultrafine WC-15 wt% Co cemented carbides. J. Alloys Compd. 2018;748:577–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.03.197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. R. Tan D. Q. Zhu H. B. Wen O. Y. Chun Z. Effect mechanism of arsenic on the growth of ultrafine tungsten carbide powder. Adv. Powder Technol. 2018;29:1348–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.apt.2018.02.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. Lu Z. C. Zeng M. Q. Zhu M. Achieving combination of high hardness and toughness for WC-8Co hardmetals by creating dual scale structured plate-like WC. Ceram. Int. 2018;44:2668–2675. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.10.190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Z. Linder D. Hedstrm P. Borgenstam A. Holmstrm E. Strm V. Effect of carbon content on the Curie temperature of WC-NiFe cemented carbides. Int. J. Refract. Met. H. 2019;78:27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2018.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garbiec D. Siwak P. Microstructural evolution and development of mechanical properties of spark plasma sintered WC–Co cemented carbides for machine parts and engineering tools. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2019;19:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.acme.2018.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y. Luo B. H. He K. J. Jing H. B. Bai Z. H. Chen W. Zhang W. W. Mechanical properties and microstructure of WC-Fe-Ni-Co cemented carbides prepared by vacuum sintering. Vacuum. 2017;143:271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.vacuum.2017.06.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balbino N. A. N. Correa E. O. de Carvalho Valeriano L. Assis D. Microstructure and mechanical properties of 90WC-8Ni-2Mo2C cemented carbide developed by conventional powder metallurgy. Int. J. Refract. Met. H. 2017;68:49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2017.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarragó J. M. Roa J. J. Valle V. Marshall J. M. Llanes L. Fracture and fatigue behavior of WC–Co and WC–CoNi cemented carbides. Int. J. Refract. Met. H. 2015;49:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2014.07.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchegger C. Lengauer W. Bernardi J. Gruber J. Ntaflos T. Kiraly K. Langlade J. Diffusion parameters of grain-growth inhibitors in WC based hardmetals with Co, Fe/Ni and Fe/Co/Ni binder alloys. Int. J. Refract. Met. H. 2015;49:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2014.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aristizabal M. Sanchez J. M. Rodriguez N. Ibarreta F. Martinez R. Comparison of the oxidation behaviour of WC–Co and WC–Ni–Co–Cr cemented carbides. Corros. Sci. 2011;53:2754–2760. doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2011.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q. M. Yang J. G. Yang H. L. Ni G. H. Ruan J. M. Synthesis of ultrafine WC-10Co composite powders with carbon boat added and densification by sinter-HIP. Int. J. Refract. Met. H. 2017;62:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2016.06.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z. Ren X. R. Liu M. X. Xu C. Zhang X. H. Guo S. D. Chen H. Effect of Cu on the microstructures and properties of WC-6Co cemented carbides fabricated by SPS. Int. J. Refract. Met. H. 2017;62:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2016.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radajewski M. Schimpf C. Krüger L. Study of processing routes for WC-MgO composites with varying MgO contents consolidated by FAST/SPS. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2017;37:2031–2037. doi: 10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2017.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X. Y. Peng Z. J. Wang C. B. Miao H. Z. Influence of nano-sized La2O3 addition on the sintering behavior and mechanical properties of WC–La2O3 composites. Ceram. Int. 2015;41:14811–14818. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2015.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. C. Chang S. H. Tang T. P. Peng K. Y. Chang W. C. Study on the properties of WC-10Co alloys adding Cr3C2 powder via various vacuum sintering temperatures. J. Alloys Compd. 2016;686:810–815. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.06.221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. Liu C. X. Zhang J. Deng S. J. Ye D. Oxidation and hot corrosion behavior of Al2O3/YSZ coatings prepared by cathode plasma electrolytic deposition. Corros. Sci. 2016;109:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2016.03.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ren C. He Y. D. Wang D. R. Cyclic oxidation behavior and thermal barrier effect of YSZ–(Al2O3/YAG) double-layer TBCs prepared by the composite sol–gel method. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011;206:1461–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2011.09.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mamivand M. Zaeem M. A. El Kadiri H. Phase field modeling of stress-induced tetragonal-to-monoclinic transformation in zirconia and its effect on transformation toughening. Acta Mater. 2014;64:208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2013.10.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song M. He S. Y. Du K. Huang Z. Y. Transformation induced crack deflection in a metastable titanium alloy and implications on transformation toughening. Acta Mater. 2016;118:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2016.07.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su W. Sun Y. X. Liu J. Feng J. Ruan J. M. Effects of Ni on the microstructures and properties of WC–6Co cemented carbides fabricated by WC–6 (Co, Ni) composite powders. Ceram. Int. 2015;41:3169–3177. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2014.10.165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rumman R. Xie Z. Hong S. Ghomashchi R. Effect of spark plasma sintering pressure on mechanical properties of WC–7.5 wt% Nano Co. Mater. Des. 2015;68:221–227. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. C. Kim D. K. Woo K. D. Ko I. Y. Shon I. J. Consolidation of binderless WC–TiC by high frequency induction heating sintering. Int. J. Refract. Met. H. 2008;26:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2007.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Imasato S. Tokumoto K. Kitada T. Sakaguchi S. Properties of ultra-fine grain binderless cemented carbide ‘RCCFN’. Int. J. Refract. Met. H. 1995;13:305–312. doi: 10.1016/0263-4368(95)92676-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. Stevens R. Zirconia-toughened alumina (ZTA) ceramics. J. Mater. Sci. 1989;24:3421–3440. doi: 10.1007/BF02385721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hannink R. H. J. Kelly P. M. Muddle B. C. Transformation toughening in zirconia-containing ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2000;83:461–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1151-2916.2000.tb01221.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garay J. E. Current-activated, pressure-assisted densification of materials. Annu. Rev. Materials Research. 2010;40:445–468. doi: 10.1146/annurev-matsci-070909-104433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ijaz M. Yousaf M. El Shafey A. M. Arrhenius activation energy and Joule heating for Walter-B fluid with Cattaneo–Christov double-diffusion model. J. Therm. Anal. Calori. 2020:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chen I. W. Wang X. H. Sintering dense nanocrystalline ceramics without final-stage grain growth. Nature. 2000;404:168–171. doi: 10.1038/35004548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]