Abstract

Glycoalkaloids have been widely demonstrated as potential anticancer agents. However, the chemosensitizing effect of these compounds with traditional chemotherapeutic agents has not been explored yet. In a quest for novel effective therapies to treat bladder cancer (BC), we evaluated the chemosensitizing potential of glycoalkaloidic extract (GE) with cisplatin (cDDP) in RT4 and PDX cells using 2D and 3D cell culture models. Additionally, we also investigated the underlying molecular mechanism behind this effect in RT4 cells. Herein, we observed that PDX cells were highly resistant to cisplatin when compared to RT4 cells. IC50 values showed at least 2.16-folds and 1.4-folds higher in 3D cultures when compared to 2D monolayers in RT4 cells and PDX cells, respectively. GE + cDDP inhibited colony formation (40%) and migration (28.38%) and induced apoptosis (57%) in RT4 cells. Combination therapy induced apoptosis by down-regulating the expression of Bcl-2 (p < 0.001), Bcl-xL (p < 0.001) and survivin (p < 0.01), and activating the caspase cascade in RT4 cells. Moreover, decreased expression of MMP-2 and 9 (p < 0.01) were observed with combination therapy, implying its effect on cell invasion/migration. Furthermore, we used 3D bioprinting to grow RT4 spheroids using sodium alginate-gelatin as a bioink and evaluated the effect of GE + cDDP on this system. Cell viability assay showed the chemosensitizing effect of GE with cDDP on bio-printed spheroids. In summary, we showed the cytotoxicity effect of GE on BC cells and also demonstrated that GE could sensitize BC cells to chemotherapy.

Keywords: Solanum lycocarpum, 3D model, Bioprinting, Patient derived xenografts, Drug susceptibility, Bladder cancer

1. Introduction

Bladder cancer (BC), especially urothelial carcinoma, is the most prevalent tumor in the patients of the urological field. It is the fourth most common cancer in men and overall the fifth most common cancer worldwide [1]. Standard therapy to the patients with non-muscle-invasive BC includes transurethral tumor resection followed by an intravesical chemotherapy (i.e., with cisplatin and/or doxorubicin, paclitaxel, docetaxel either through systemic or intravesical) or immunotherapy (with Bacillus Calmette-Guerin - BCG) [2,3]. However, several side effects and the recurrence rate limit the therapeutic usage of chemotherapy and BCG [4–6]. Over 60% of patients will have disease recurrence at 2 years [7].

There has been no major breakthrough in treating advanced urothelial BC beyond chemotherapy and surgery in the past 30 years until recently when immunotherapy and one targeted therapy targeting fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration [8]. However, immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors has a response rate of approximately 20%, and less than 20% of advanced bladder cancers harbor FGFR alterations and can be treated with the FGFR inhibitor [9,10]. Moreover, the tumor heterogeneity and acquired resistance may cause therapy failure [11,12]. Because of these facts and limited efficiency of traditional treatments to BC, alternative therapies have been constantly proposed [13,14].

Recently, scientists have been exploring combination approaches for cancer treatment, in which other therapeutic agents are usually coadministered with chemotherapeutic drugs. Such efforts are motivated by their chemosensitizer, synergetic/additive effects against malignant tumors [13]. On this context, bioactive compounds from natural products have been explored to act as potent chemosensitizers in combination with conventional chemotherapeutic drugs [15,16]. This strategy can offer several benefits by overcoming the limitations of existing chemotherapeutic regimes, reducing the dosage required and consequently the side effects.

Cancer therapeutics have benefited from numerous drug classes derived from natural product sources [17–19]. The fruits of Solanum lycocarpum A. St.-Hil (Solanaceae) have steroidal glycoalkaloids, mainly solamargine (SM) and solasonine (SS) (Fig. 1) [20]. Biological investigations of SM and SS showed significant cytotoxicity against several human cancer cell lines, including bladder cancer and skin tumors [21–29].

Fig. 1.

Structure of solamargine and solasonine.

The 3-dimensional (3D) spheroid cancer cell model represents an important tool to mimic the in vivo tumor growth. Mimicking the complexity of the in vivo tumor for drug screening assays is considered as a major challenge in drug development process. Traditionally, in vitro cell-based assays are carried out using cells cultured as a monolayer in a bi-dimensional (2D) format [30,31]. However, most of the tumor cells in the organism, as wells as healthy cells in normal tissue are in a three-dimensional (3D) physiological microenvironment. The 3D microenvironment is important because the individual phenotype and function of cells are strongly dependent on their interactions with proteins from the extracellular matrix (ECM) and with neighboring cells [32,33]. Cells cultured in 2D have significant reductions in cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions, thereby limiting their ability to mimic the in vitro natural cellular responses [34]. However, cells cultured in 3D systems can recover some characteristics, which are crucial for physiological relevant cell-based assays [35,36].

3D bioprinting is gaining major attention, especially in cancer research. This technology enables the direct assembly of cells and extracellular matrix materials to form an in vitro 3D cellular model. Moreover, it allows creation of 3D constructs in a layer-by-layer of desired shapes using bioink, such as hydrogels to facilitate hetero-cellular interactions which are present in native tissues and organs [37–39].

It has been difficult to propagate cells in vitro that are derived directly from human tumors or healthy tissue. However, in vitro pre-clinical models are essential tools for the study of basic cancer biology, including drug discovery [40]. Patient Derived Xenografts (PDX) are developed from uncultured patient cancer cells engrafted into immunodeficient mice [41]. In this work we cultivated PDX cancer cells in 2D and 3D models, which represents an important need for the field of cancer medicine.

In this study, we investigated the role of glycoalkaloidic extract (GE) alone as cytotoxic agent and its chemosensitizing effect with cisplatin (cDDP) in BC. We evaluated these effects in 2D and 3D models using RT4 human bladder cancer and PDX cells. Furthermore, we investigated the molecular mechanisms involved behind these in RT4 cells and reported a method of 3D bioprinting using gelatin/alginate hydrogel to grow bladder tumor cells in 3D printed model.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Preparation of glycoalkaloidic extract (GE)

The GE was prepared according to our previously published method [42]. The extraction was selective by furnishing 47.96% ± 0.34 of SM and 42.86% ± 0.83 of SS quantified by LC-MS/MS (Shimadzu®) [28].

2.2. Cell line and cell culture

RT4 human bladder cancer cell line was kindly gifted from Dr. Chong-Xian Pan, Department of Internal Medicine, University of California Davis/Comprehensive Cancer Center. These cells were cultured in McCoy 5A medium (Caisson Lab®) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) from Invitrogen® and 1% of mixture of the penicillin (5000 U/mL) and streptomycin (0.1 mg/mL), neomycin (0.2 mg/mL) (Sigma Aldrich®) and maintained in a controlled humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 37 °C.

2.3. Patient derived xenografts (PDX)

The PDX tumor was also obtained from Dr. Chong-Xian Pan’s lab. The PDX BL0808 came from The Jackson Laboratory Cancer Center (JAXCC, Sacramento, USA, reference J000101121) from advanced bladder cancer of a patient previously treated (5 months before sample collection) with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (4 cycles Gemcitabine/Cisplatin). The animal protocol was approved by the Florida A&M University Animal Care and Use Committee. The tumor sample was reduced to small pieces and filtered using strainer of 70 μm. The filtered cells were centrifuged at 0.8 rpm for 4 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in 50 μL of medium and 50 μL of Matrigel (Corning®) and injected subcutaneously into the flanks of 4–5-week-old nu/nu athymic nude mice. The mice were monitored for tumor growth for around 4 weeks. After this, the tumor was removed, reduced to small pieces and filtered using 70 μm strainer. The filtered bladder PDX cells were cultured in 75 cm2 flask using DMEM and F-12 media in 1:1 ratio supplemented with 20% FBS, 1% of penicillin/streptomycin and hormones of hydrocortisone, EGF, FGF and TGF-beta.

2.4. Cell viability to RT4 and PDX cells in monolayer model

RT4 and PDX cells were seeded in 96-well plate (Corning®) at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well and kept in the incubator for 24 h before the treatment. We evaluated the cytotoxicity effects of GE and cDDP in RT4 cells using concentrations ranging from 0.625 to 40 μg/mL and 1.04 to 66.7 μM, respectively. PDX cells were treated with GE and cDDP at the concentrations ranging from 12.5 to 100 μg/mL and 17 to 133 μM, respectively for 48 h. To study the possible effect of DMSO on cells, it was used at highest concentration of 0.1%.

After 48 h, the cytotoxicity activity was evaluated using crystal violet dye (Sigma®). The absorbances were measured using microplate reader (Tecan®) at 570 nm. The IC50 values were calculated by non-linear regression equation, using GraphPad Prism®.

For the chemosensitizer effect, the RT4 cells were treated with 5 μg/ mL of GE (25% of inhibitory concentration (IC25)) for 24 h. After the incubation time, the medium containing GE was removed, and the cells were washed with PBS and were exposed to concentrations of 1.04 to 66.7 μM of cDDP for an additional 24 h. In PDX cells, pre-treatment was with 19 μg/mL of GE (IC25), for 24 h. Then, the cells were washed with PBS and treated with serial dilutions of cDDP (17 to 133 μM) for another 24 h.

In order to analyze and qualify the interaction of GE and cDDP, combination index (CI) were determined by CompuSyn software [43]. Synergy was quantified by CI with CI < 1 indicating synergism, CI > 1 indicating antagonism, and CI = 1 indicating additivity.

2.5. Preparation of RT4 and PDX spheroids culture and cytotoxicity assay

3D spheroids of RT4 cells were generated using 96-well microhoneycomb (MH) plate (NanoCulture plate MH pattern high-binding, Organogenix®) and for PDX cells, we used 96-well low attachment plates (LIPIDURE® COAT, AMS Biotechnology, United Kingdom). RT4 cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells/well with 2% of Matrigel (Culturex®) in McCoy 5A complete medium. PDX cells were seeded at 3.9 × 104 cells/well, without Matrigel, to generate 3D spheroids using DMEM:F-12 (50:50) enriched media as described in the Section 2.3. The working volume in both the plates was 100 μL of culture medium per well.

After 72 h, 3D spheroids were formed. To compare the cytotoxicity and chemosensitizer effects in 3D and 2D models, the 3D spheroids were treated with the same groups and concentrations as described above (Section 2.4). Afterwards, the cells were incubated by 48 h.

For the chemosensitizing effects, the RT4 spheroids we treated with 11 μg/mL of GE (IC25 of GE against RT4 cells in 3D model) and PDX spheroids with 27 μg/mL of GE and, both cell lines were incubated for 24 h. Then, the pre-treated spheroids were exposed to a serial dilution of cDDP for additional 24 h.

After the treatments, the spheroids were analyzed by ATP-based cell viability assays using CellTiter-Glo 3D (Promega®). The luminescence was recorded using a Synergy™ 2 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek®). The IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism®. The combination index was also determined for the treatments in 3D model.

2.6. Clonogenic assay

RT4 cells were seeded in a 6-well plate (Corning®) at a density of 3 × 105 cells/well and incubated for 24 h. Then, the cells were treated with GE (5 μg/mL), cDDP (8.4 μM) or combination of GE + cDDP following the treatment protocol and incubation times as described in the monolayer model. After the treatments, cells were trypsinized, counted to 1000 cells/well and then seeded in 6-well plates. The plates were further incubated for 14 days to allow colony formation. The media was changed every alternative day. The colonies grown in each well were fixed with glutaraldehyde and stained with crystal violet. Number of colonies were counted using an Olympus optical microscope (IX 71) and representative images were captured.

2.7. Scratch assay

In vitro scratch assay was performed to analyze the percent inhibition of bridging of migration area by GE and cDDP alone and also with combination. The assay was performed by following the protocol as described by Godugu et al. [44]. Briefly, RT4 cells (1.25 × 105 cells/ well) were seeded in a 24-well plate and incubated overnight. In each well, at the middle portion, cells were scratched using a sterile micropipette tip to make a gap. The wells were then washed twice with PBS to remove the scratched cells. Then, the cells were treated with GE (5 μg/mL), cDDP (8.4 μM) or combination. After 48 h, the cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet. An optical microscope (Olympus IX71) was used to take images of the scratch area. The gaps (scratch) area were calculated using ImageJ software.

2.8. Apoptosis analysis by cell staining and fluorescent microscopy

RT4 cells were seeded at a density of 3 × 105 cells/well in a 6-well plate and kept for 24 h in the incubator. The cells were then treated with GE (5 μg/mL), cDDP (8.4 μM) or combination. Untreated cells were considered as control group. Post-incubation, the cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% formaldehyde (Sigma®) for 30 min at 37 °C. The cells were then washed twice with PBS before the addition of 0.1% of Triton X100 (Fisher Chemical®) for permeabilization. After 30 min of incubation at 37 °C, cells were washed again with PBS twice. Finally, NucBlue was added (Hoechst 33342) (Invitrogen®) and the images were taken using an Olympus BX40 fluorescence microscope at 20 x magnification with the blue filter (460 nm). Apoptotic cells were identified by morphology and by condensation/fragmentation of their nuclei. The percentage of apoptotic cells were calculated as the ratio of apoptotic cells to total cells counted. The cells were counted using ImageJ.

2.9. Western blot

Western blotting was carried out in RT4 cells cultured in mono-layers treated with GE (5 μg/mL), cDDP (8.4 μM) or combination for the following biomarkers: Survivin, Bcl-2, Bax, PARP, Caspase 3, Cleaved Caspase 3, Caspase 9, Cleaved Caspase 9, MMP-2 and MMP-9. Briefly, after incubation with the treatments, the cells were scraped, centrifuged, washed twice with PBS and incubated in RIPA buffer ((50 nM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, with 150 nM Sodium Chloride, 1.0% Igepal CA-630 (NP-40), 0.5% Sodium Deoxychloate, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) and protease inhibitor (500 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Protein concentrations were determined by the BCA assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol and the standard plot was generated by using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard. For this quantification, 50 μg of protein from the control and all the different treatment samples were denatured by boiling at 100 °C for 5 min in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer and subsequently electrophoresed in 10% SDS-PAGE gel and then transferred for nitrocellulose membranes followed by blocking with 5% BSA in tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (10 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.5% Tween), and then probed with primary antibodies against Survivin, Bcl-2, Bax, PARP, Caspase 3, Cleaved Caspase 3, Caspase 9, Cleaved Caspase 9, MMP-2 and MMP-9 at 1:750 dilution. Protein expressions were then detected with HRP conjugated secondary antibodies by using Super Signal West pico chemiluminescent solution (Pierce®). Densitometric analysis of the bands was performed as per our previous methods using Chemi-Doc XRS+ Imaging system (Bio-Rad®). Results were expressed as percentage ratios of expression of altered proteins to beta-actin (set to 100%) and plotted against the relative intensity in comparison to the control (β-actin).

2.10. 3D bioprinting

2.10.1. Preparation of the bioink

The sodium alginate-gelatin (Alg-Gel) hydrogel was prepared using the method previously described by our group. Briefly, 2 g of gelatin (4%) was dissolved in 50 mL of a saline solution (0.0045 g/mL) at 37 °C using a water bath and constant stirring at 500 rpm. Then, 1.625 g of sodium alginate (3.25%) was added into the gelatin solution and dissolved using stirring at 500 rpm for 1 h at room temperature. To remove the bubbles of the gel after the complete solubilization of the sodium alginate, the gel was kept for 30 min in the water bath (37 °C) without stirring.

2.10.2. Bioprinting of cell-encapsulated scaffolds

In our work, we used Alg-Gel hydrogel to form scaffolds and bioprint RT4 cells. For this purpose, the RT4 cells were trypsinized, counted to 10 × 106 cells/mL and then re-suspended in 20 μL of McCoy 5A medium. The cell suspension was manually transferred by pipette into the middle of the hydrogel (1.20 g) and then mixed with the bioink (the bio-printable material used in bioprinting process; Alg-Gel) by using a autoclaved spatula to create a homogeneous mixture. The mixed hydrogel with RT4 cells was then loaded into a sterile cartridge and finally printed using 27G nozzle.

Inkredible (Cellink®, Sweden) bioprinter was used to print the scaffolds. The cells were printed at room temperature in a biosafety hood.

Square scaffolds (0.5 mm thick, 10.5 mm long and 10.5 mm wide) were printed in Petri dishes. Immediately after printing, 1 mL of 100 mM CaCl2 was added onto the scaffold within 2 min for cross-linking. Then, the scaffold was washed in Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) (Corning®) to remove excess calcium ions and transferred to a 24-well plate containing complete McCoy 5A medium supplemented with of EGF (10 mg/mL), FGF (10 ng/mL), and antibiotics (penicillin (5000 U/mL), streptomycin (0.1 mg/mL) and neomycin (0.2 mg/mL). The plate was kept in the incubator at 37 °C, 5% of CO2 and the culture media was changed every 3 days.

To determine the cellular morphology of the spheroids (formed after 7 days), they were stained with Actin green (Invitrogen®, Eugene, OR, USA) and NucBlue. The spheroids were fixed and permeabilizated as described in Section 2.8. Then, 2 drops/mL of Actin green was added in McCoy media (without FBS) into each well and incubated for 30 min. After this, NucBlue (2 drops/mL) was also added and the plate was incubated for extra 30 min before observing through fluorescent microscopy.

2.10.3. Live/dead assay

We used the viability assay kit (Biotium®) to provide green or red fluorescent staining for live or dead cells, respectively. The assay employed two probes that detect intracellular esterase activity in live cells and compromised plasma membrane integrity in dead cells. The esterase substrate, calcein AM, stains live cells green, while the membrane-impermeable DNA dye Ethidium homodimer III (EthD-III) stains dead cells red.

We immersed printed scaffolds in a dye solution containing calcein AM and EthD-III in McCoy 5A medium without FBS in a 24-well plate and kept for 30 min at 37 °C. Then, the detection was done using fluorescence microscopy (Olympus IX 71). We examined the fluorescence images from five different fields of each bio-printed scaffold or just the hydrogel mixed with cells (before and after printing). Three independent samples were counted. We counted the number of live (green) and dead cells (red) in each field using a cell counting tool (ImageJ). The percent cell viability was calculated with the following equation:

| (1) |

2.10.4. Cell viability analysis

We evaluated the viability of the spheroids in the scaffolds treated with the IC50 concentrations of each single treatment on RT4 3D model plate: GE (22 μg/mL), cDDP (48 μM) or combination of these values following the same incubation times as previously described. We used viability assay kit (Calcein AM and EthD-III) and MTT (3-4.5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2.5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) method [46,47].

After 7 days’ incubation, and the complete formation of spheroids in the scaffolds, they were treated with the different groups as described above (quadruplicate). After the incubation time with the drugs, the culture medium was removed, and the scaffolds were incubated with 1 mL of McCoy 5A medium (without FBS) containing 0.66 mg/mL of MTT (Sigma-Aldrich®) during 4 h at 37 °C. After incubation, 500 μL of DMSO was added into the wells and then the scaffolds were gently mixed for 10 min to ensure complete dissolution of the formed formazan crystals. 100 μL aliquots from each sample were pipetted into a 96-well plate and optical density (OD) was measured at 570 nm through a microplate reader (Tecan®). The values obtained were expressed as the percentage of viable cells according to Eq. (2):

| (2) |

2.11. Statistical analysis

The data was presented as mean ± SD (standard deviation) for at least three independent experiments. The statistical analysis was performed using one-way Anova followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons by GraphPad Prism version 5.0. Differences were considered statistically significant when p values were lower than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Glycoalkaloidic extract enhances the sensitivity of cisplatin in RT4 cell lines

3.1.1. Cytotoxicity and chemosensitizing effect of GE

Cytotoxicity with glycoalkaloidic extract (GE), cisplatin (cDDP) and GE+cDDP was assessed in 2D and 3D cultures of RT4 and PDX bladder cells and their sensitivity was determined by comparing their IC50 values.

In RT4 cells (i.e., 2D monolayer model), the IC50 values were observed to be 10.12 ± 0.23 μg/mL for GE and 18.13 ± 0.37 μM for cDDP and 8.43 ± 0.23 μM for the combination of cDDP with GE (5 μg/mL) was (Table 1).

Table 1.

IC50 to 2D and 3D model.

| Cell line | RT4 | PDX | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Treatments | 2D | 3D | 2D | 3D |

| Glycoalkaloidic extract (GE) (μg/mL) | 10.12 ± 0.23 | 21.81 ± 6.67* | 38.21 ± 9.67 | 54.43 ± 16.22** |

| Cisplatin (cDDP) (μM) | 18.13 ± 0.37 | 47.76 ± 10.4 *** | 40.22 ± 11.73 | 60.16 ± 13.32*** |

| GE (IC25) + cDDP (μM) | 8.43 ± 0.23 | 28.06 ± 6.89** | 32.65 ± 9.33 | 48.43 ± 8.33** |

Each data point was represented as mean ± SD (n = 4).

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001 versus respective 2D groups.

3D RT4 cultures treated with GE and cDDP showed increased IC50 values of around 2.16 and 2.63-fold respectively in comparison to those observed in 2D cultures. 3D RT4 cultures treated with GE + cDDP showed superior disintegration of the spheroids when compared to individual drug treatments. Moreover, GE (5 μg/mL) + cDDP increased the IC50 value around 3.33-fold higher in 3D RT4 cultures when compared to 2D monolayer cells.

In the 2D cultures of PDX cells, IC50 values were found to be 38.21 ± 9.67 μg/mL for GE, 40.22 ± 11.73 μM for cDDP, and 32.65 ± 9.33 μM for GE (19 μg/mL) + cDDP (Table 1). The IC50 values for GE, cDDP, and GE (27 μg/mL) + cDDP were observed to be 54.43 ± 16.22 μg/mL, 60.16 ± 13.32 μM and 48.43 ± 8.33 μM, respectively, in 3D cultures of PDX cells. IC50 values increased in 3D culture of PDX cells by least 1.4-fold in comparison to 2D cultures.

Increased IC50 values revealed decreased sensitivity of GE, cDDP and GE + cDDP in 3D spheroid cultures of RT4 and PDX cells when compared to 2D cultures. PDX cells showed higher IC50 values than RT4 cells in both 2D and 3D cultures, suggesting superior resistance of PDX cells to chemotherapy. IC50 values in 2D cultures treated with GE, cDDP, and GE + cDDP were 3.77, 2.21 and 3.87-fold, respectively, higher in PDX cells when compared to RT4 cells. Moreover, IC50 values in 3D cultures treated with GE, cDDP, and GE + cDDP were 2.49, 1.26 and 1.73- fold, respectively, higher in PDX cells when compared to RT4 cells, indicating the resistance of PDX cells.

The combined treatment showed CI < 1 for all cell lines tested in both models, indicating synergistic effects. GE inhibited the growth of RT4 and PDX cells and when combined with cDDP, GE acted as a chemosensitizer/synergistic and hence we observed superior cytotoxicity effects with GE + cDDP when compared to GE and cDDP alone.

3.1.2. Clonogenic assay

GE + cDDP significantly decreased the colonies formation and their size in RT4 cells (Fig. 2). The number of colonies formed by untreated RT cells (control), GE, cDDP and GE + cDDP treated RT4 cells were observed to be 25 ± 6, 19 ± 7, 17 ± 4 and 10 ± 3, respectively.

Fig. 2.

The combined treatment of GE (5 μg/mL) with cDDP (8.4 μM) suppressed colony formation (A) and reduced their size in RT4 cells. (B) Control (C) combined treatment. Values were compared with control (*p < 0.05). Bar scale: 50 μm.

As shown in Fig. 2, the colony formation from RT4 cells was significantly reduced by the combination treatment, indicating that GE + cDDP could significantly inhibit the growth and proliferation of RT4 cells.

3.1.3. GE chemosensitized RT4 cells to cDDP and inhibited the migration

GE (5 μg/mL) and cDDP (8.4 μM) alone inhibited cell migration by 16.53 ± 1.2% and 15.31 ± 1.6%, respectively, in RT4 cells. The combination group of GE + cDDP inhibited migration by 28.38 ± 1.23% while the control cells inhibited migration by only 12.6 ± 1.2%. The observed increased percentage of gap in GE + cDDP group indicated that GE sensitized RT4 cells more to cDDP and thereby significantly decreased the migration in comparison to control (Fig. 3). Fig. 4 shows the representative microscopic images of scratch assay using RT4 cells after the treatments for all groups.

Fig. 3.

The migration of RT4 cells was quantified by measuring percentage of gap widths. Migrated cells were expressed relative to the whole area. ***p < 0.001 compared with control group.

Fig. 4.

The pictures represent cell migration after incubation with the treatments: Control (untreated), cDDP (cisplatin), GE (glycoalkaloidic extract) and combination (GE + cDDP). Bar scale: 200 μm.

3.1.4. GE + cDDP induced-apoptosis is associated with morphological changes in cell nuclei in RT4 cells

To assess whether the growth inhibitory effects of glycoalkaloidic extract on RT4 cells were associated with apoptosis, bladder cancer cells were stained with NucBlue and then observed using a fluorescent microscope (Fig 5). Nuclear chromatin condensation and fragmented punctuate blue nuclear fluorescence were observed in the combination treatment, while the control cells displayed normal and intact nuclei. These observations suggest that GE + cDDP could kill the RT4 cells by apoptosis.

Fig. 5.

Glycoalkaloidic extract (GE) induced the apoptosis in RT4 cells. The morphology of the cell nucleus in bladder cancer cells treated with GE, cisplatin and combination was observed after NucBlue staining (10×). Bar scale: 100 μm.

Nuclear staining demonstrated that combination treatment of GE (5 μg/mL) and cDDP (8.4 μM) significantly induces apoptosis (57 ± 5%) in comparison to individual treatments of GE and cDDP (8 ± 3% and 11 ± 5% respectively; Fig. 6) in RT4 cells. The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined as the ratio of apoptotic cells to total number of cells counted.

Fig. 6.

Percentage of apoptotic for each treated group. ***p < 0.001 comparing with control group. Control (no treated), cDDP (cisplatin = 8.4 μM), GE (glycoalkaloidic extract = 5 μg/mL) and combination (GE + cDDP).

3.2. GE and cDDP killed cancer cells through apoptosis

GE in combination with cDDP significantly down regulated the protein expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, PARP, survivin and up-regulated the expression of Bax, suggesting that GE sensitized RT4 cells to cDDP and thereby induced significant cell death and the mechanism through which the cell death occurs was inferred to be apoptosis (Fig. 7A through F).

Fig. 7.

A, B and C: Western blot analysis of different proteins in RT4 cancer cells treated with cisplatin (cDDP), glycoalkaloid extract (GE) and its combination (GE + cDDP). D, E and F: Densitometric analysis of Western blot using β-actin as housekeeping protein. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 difference compared with control.

Bax/Bcl2 ratio was involved in regulating the mitochondria-associated apoptotic pathway. Herein, we observed that the ratio of Bax/Bcl2 in RT4 cells treated with GE + cDDP was increased (Fig. 8), suggesting that the combination might induce apoptosis through the mitochondria-associated apoptotic pathway in RT4 cells.

Fig. 8.

Ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 in the treated groups. ***p < 0.001 comparing with control group.

Our data also showed that cleaved caspase-3 and −9 expressions were increased by GE + cDDP in RT4 cells. This suggests that combination could also activate caspase associated apoptosis pathway (Fig.7B and E). In addition, GE + cDDP decreased the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9, indicating the inhibitory effects of the combination on migration/invasion of RT4 cells (Fig. 7 C and F).

3.3. 3D bioprinting

3.3.1. Cell viability of RT4 cells with sodium alginate-gelatin bioink

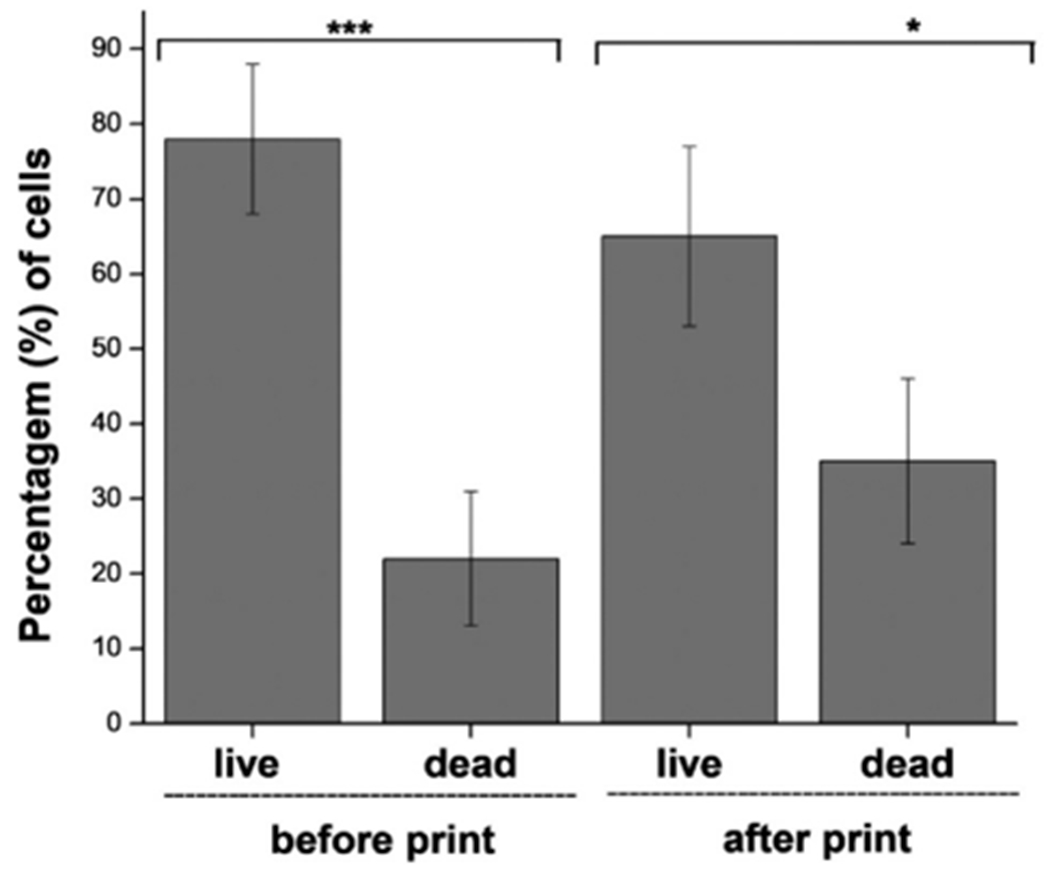

To assess the effect of bioprinting process on cell survival, live/dead assay was performed on cells mixed with Alg-Gel before printing, cells with hydrogel immediately after print, spheroids after 7 days of printing, and spheroids after 15 days of printing (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

3D bio-printed sodium alginate-gelatin (Alg-Gel) hydrogel containing RT4 cells. Live/dead cell staining was performed for assessing cell viability during which live cells are stained in green whereas dead cells in red color. (A) Before printing. (B) RT4 cells printed with hydrogel immediately after bioprinting. (C) RT4 cells grown as spheroids after 7 days of culturing. (D) After 15 days, few viable cells were observed. Bar scale: Picture A and B 100 μm; Pictures C and D 50 μm. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

As shown in Fig. 9 A and B, most of the cells remained viable (i.e., green color) and a small number of dead cells (i.e., red color) were observed. The cell viability tested with the cells mixed with the hydrogel before printing was observed to be around 92%. The viability of the live cells decreased to 89% after the bioprinting process with a pressure of around 45 kPa. Both the samples (before and after print) containing cells were exposed to crosslinking solution (CaCl2) for less than 2 min. The addition of Ca2+ ions and applied pressure did not induce any discernible impact on the viability of RT4 cells (Fig. 10). We did not observe any significant differences in the viability of the cells before and after printing (p < 0.05) using one-way Anova followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons by GraphPad Prism version 5.0.

Fig. 10.

Live and dead cell assay before and after bioprinting process. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

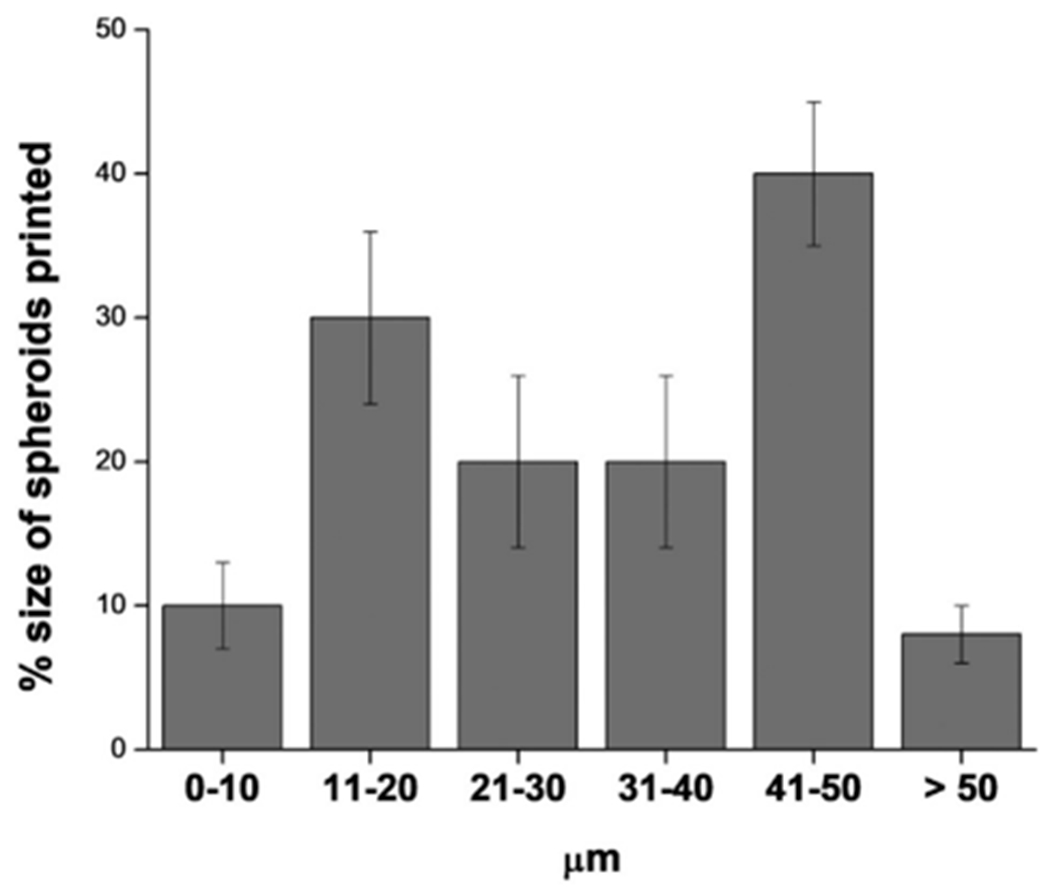

When cultured in vitro, 3D bioprinted RT4 cells dispersed within the scaffold proliferated and grew as spheroids after 7 days. After 7 days, spheroids attained size of diameter ranging from 41 to 50 μm and most of them were prevalently viable (Fig 9C).

The size distribution of the spheroids printed after 7 days are represented in the Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Population size distribution of the spheroids printed after 7 days.

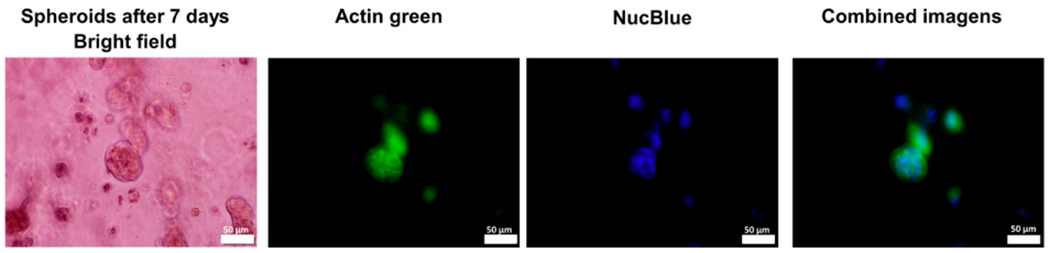

Staining with Actin green and NucBlue dyes showed the structure of cytoplasm and nucleus of the spheroids after 7 days of printing (Fig. 12). After 15 days, staining with Ethidium homodimer III showed the presence of dead cells (Fig. 9). Therefore, 7 days was considered as treatment initiation point for our studies.

Fig. 12.

RT4 spheroids stained with actin green and NucBlue after 7 days of bioprinting process. Bar scale: 50 μm.

3.3.2. Cytotoxicity in 3D bioprinter spheroids

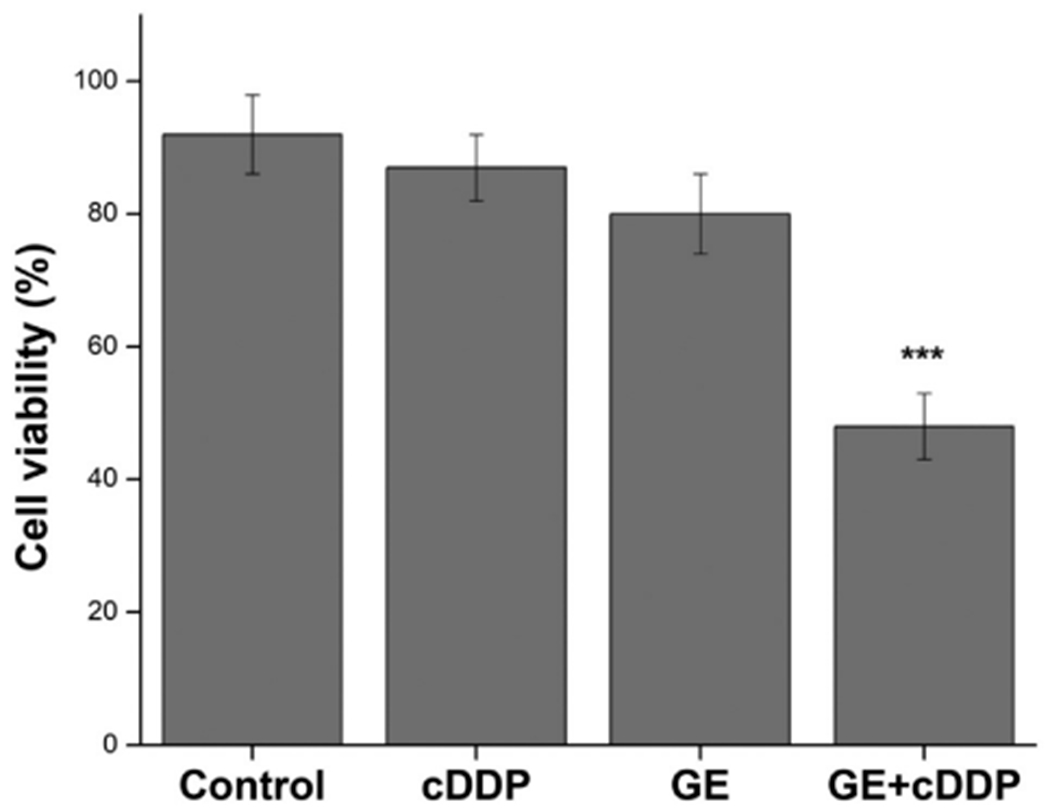

GE (22 μg/mL), cDDP (48 μM) and combination (GE + cDDP) were used to treat the spheroids after 7 days of growth. The effect of the samples on the spheroids was assessed by live/dead and MTT assay.

Images from the live/dead assay showed many dead cells in GE + cDDP treated group in comparison to control and individual groups of GE and cDDP (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13.

Live/dead assay to RT4 spheroids on scaffolds treated with glycoalkaloidic extract (GE) (22 μg/mL), cisplatin (cDDP) (48 μM), or combination of GE + cDDP. Bar scale: 100 μm.

Cell viability of the spheroids in scaffolds was determined by MTT method. Fig. 14 shows that GE + cDDP group significantly decreased cell proliferation when compared to control (***p < 0.001). The viability in control, cDDP, GE and GE + cDDP treated RT4 cells were found to be 92 ± 7% 87 ± 6%, 80 ± 9% and 48 ± 5%, respectively.

Fig. 14.

Cell viability study by MTT assay on spheroids in scaffolds treated with different groups: Control (untreated), GE (glycoalkaloidic extract = 22 μg/mL), cDDP (cisplatin = 48 μM) and GE + cDDP (combination). ***p < 0.001 difference compared with control.

4. Discussion

Chemosensitizers at much lower doses could serve as one of the potential options for increasing the therapeutic efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs. Till date, various natural compounds have been explored and some are identified as potent chemosensitizers in combination with conventional chemotherapeutic drugs [15,16,48]. Glycoalkaloids, derived from solanum genus, have been widely reported to induce cytotoxicity effects against a broad spectrum of cancers [22,24,25,49,50]. GE has also been earlier reported as cytotoxic against RT4 cells showing selectivity for cancer cell lines [25,26,28,29,51,52]. Although several studies have investigated the cytotoxicity of glycoalkaloids, the chemosensitizing effects of these compounds with anticancer drugs have not been extensively explored on tumor cells. To the best of our knowledge, only one report has shown the role of an isolated glycoalkaloid, solamargine, as a potent chemosensitizer agent for cisplatin in breast cancer cells [53]. However, no such studies have been reported till date with bladder cancer cells.

Matsui et al. [54] showed that RT4 cells are more susceptible to cDDP when pre-treated with a diterpenoid triepoxide (triptolide). Pretreatment with triptolide (40 nM) showed IC50 value of 46.9 ± 0.8 μM with cDDP in RT4 cells. Further, a quinoid diterpene (cryptotanshinone) was shown to sensitize ovarian cancer cells (A2780) to cisplatin [55]. However, all these results were performed using 2D monolayer cultures.

In our study, the IC50 values in 2D and 3D cultures of RT4 and PDX cells were significantly lower for the combination (GE + cDDP) group than the single treatments, suggesting the advantages of combination for improving the cytotoxicity effect. Furthermore, we observed increased IC50 values in GE, cDDP, and GE + cDDP treated 3D spheroids in comparison to those in 2D cell monolayers (Table 1). 3D cultured cells can recover some characteristics, which are critical for physiologically relevant cell-based assays and can also affect the sensitivity of cells to various compounds [36]. The chemoresistance in 3D system could be explained by the poor penetration of the chemotherapeutic drugs into the in vitro tumor spheroids, which is similar to the microenvironment of in vivo tumors [56]. Another possible explanation is that cell-cell interaction in 3D cultures assists cell in resisting cytotoxic treatment.

We also compared the cytotoxicity and chemosensitizing effect of these compounds in 2D and 3D cultures of RT4 and PDX cells. The results showed that the PDX cells used in this study were more resistant to compounds in comparison to RT4 cells in both the models.

The anti-proliferative effect of GE + cDDP on RT4 cells was further confirmed by clonogenic assay. The inhibition of colony formation was significantly enhanced by GE treatment in combination with cDDP in RT4 cancer cells. These results suggest that the combination treatment prevents the growth of bladder cancer cells and cause cell death.

Apoptosis plays a vital role in eliminating mutated or cancer cells [57,58]. Various natural compounds, including glycoalkaloids, prevent the growth of tumor cells through apoptosis induction [28,29,55,59]. Earlier studies have shown that solamargine induced-cell death by apoptosis in osteosarcoma, breast, human hepatoma, lung, and bladder cancer cells [28,29,53,60–63]. Our data demonstrated that bladder cancer cells treated with GE + cDDP displayed specific apoptotic morphological changes. Further, the induction of apoptosis is often related to the suppression of anti-apoptotic proteins and up-regulation of pro-apoptotic proteins [64]. Bax and Bcl-2 proteins are well known to be involved in mitochondria-associated apoptotic pathway [65]. Increased ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 can decrease the mitochondrial membrane potential and lead to a series of apoptotic events, such as the activation of caspase-9/3 [55]. Western blot analysis revealed that the combination of GE + cDDP activated caspases. Further, our results showed that GE acted as a chemosensitizer in combination with cDDP and increased the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 and the levels of cleaved caspase-3 and 9 in RT4 cells. Thus, GE + cDDP might induce apoptosis through the mitochondria-associated apoptotic pathway in bladder cancer cells. In addition, we also showed that RT4 cells treated with combination group downregulated the expression of survivin (cell survival marker), suggesting the activation of apoptosis. To the best of our knowledge, we hereby report for the first time of this data in bladder cells upon GE pre-treatment.

GE + cDDP suppressed the migration of bladder cancer cells. Since MMP-2 and MMP-9 plays an important role in cancer migration/invasion, we further investigated the underlying possible molecular mechanisms behind the observed migration inhibitory properties of GE + cDDP. Interestingly, we also observed decreased protein expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 after combination treatment. Thus, antimigration activity of the combination group in the scratch assay could be due to the downregulation of MMP-2/9 expression.

Several reports have demonstrated down-regulation of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, up-regulation of Bax, caspase-3/9 activities, decreased expression of MMP-2/9 in several cancer cells upon treatment with solamargine (one of the major compounds of GE) alone [49,53,60,62,66]. However, there is no report on the apoptosis mechanism of GE and its chemosensitizing effect with cisplatin in bladder cancer cells, which is the novelty of this work.

3D bioprinting is an ideal method to produce complex 3D biological structures through layer by layer printing of tumor cells in hydrogel based scaffolds. [67]. We also used one-step bio-fabrication method as earlier reported, in which tumor cells are mixed with the hydrogels and are printed directly to produce the in-vitro tumor model [68]. In the current study, we optimized the cell number, rheological conditions, temperature and pressure required to produce in-vitro tumor spheroids of RT4 cells using 3D bioprinter and also modified porous alginate/ gelatin hydrogel to mimic the extracellular matrix. Based on the size of spheroids and live/dead assay, we demonstrate that growth was observed till 7 days. So, treatment with various drugs was initiated after 7th day in our study. Zhao et al. demonstrate similar growth behavior for the bio-printed Hela cells with gelatin/alginate/fibrinogen hydrogels, where the spheroids have shown growth till 8th day [69].

Hydrogels are porous materials, having the advantages of high permeability for the diffusion of oxygen and nutrients. Sodium alginate hydrogel is a popular biologically inert material, which is widely used in 3D extrusion-based printing [70,71]. Gelatin is a mixture of peptide sequences, derived from partially hydrolyzed collagen and has been used widely in extrusion bioprinting because of its melting temperature in between 30 °C and 35 °C and porous nature, where the cells can accumulate and grow as spheroids [72]. The combination of alginate and gelatin is advantageous because of their chemical similarity to ECM, as alginate hydrogels covalently crosslinked with gelatin could attribute to high cell adhesion, migration and proliferation [73,74]. Similar material composition has been used as a matrix to 3D bioprint cervical cancer and glioma tumors, where they observed that the cells in 3D environment had a higher proliferation rate, formed cellular spheroids and most importantly they are found to be more resistant to chemotherapeutic tested, when compared to cells grown in 2D systems [69,71].

Chemo resistance to anti-cancer drugs represents an important characteristic feature of enhanced tumor malignancy [75]. Using MTT assay, we observed 48% viability in 3D printed RT4 spheroids after treatment with GE + cDDP (22 μg/mL and 48 μM, respectively). Further, treatments with GE or cDDP alone showed more than 50% viability. RT4 spheroids developed in 3D plates showed 50% viability (IC50) when treated with 5 μg/mL of GE and 28.06 μM of cDDP, indicating that the spheroids obtained by 3D printing technology have higher chemoresistance.

The chemosensitizing effect of GE in combination with cDDP resulted in increased cytotoxicity when compared to the single treatments in 2D and 3D cultures, suggesting the effectiveness of GE + cDDP in BC therapy.

5. Conclusion

In nutshell, we evaluated the chemosensitizing potential of glycoalkaloidic extract (GE) in combination with cisplatin (cDDP) on RT4 and PDX human bladder cancer cells using 2D and 3D models. A synergistic effect was observed when both cells were treated with the combination GE + cDDP (CI < 1). The 3D plate model showed higher IC50 values with GE + cDDP in both the cells tested when compared to the 2D systems. Higher IC50 values in PDX cells indicated their natural resistance to chemotherapeutic agents. GE + cDDP induced apoptosis, inhibited growth, colony formation and migration in RT4 cells. The combination of the extract with cDDP down-regulated the protein expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, PARP, survivin, caspases 3/9 and up-regulated Bax, indicating that the main mechanism through which the cell death occurs was by apoptosis. Additionally, western blotting analysis showed decreased MMP-2/9 expression, indicating the inhibitory effect of the GE + cDDP on cell invasion/migration. In addition, we used 3D bioprinting technology to grow RT4 spheroids by using Alg-Gel as a bioink and evaluated the chemosensitizing effect of GE + cDDP on this system. The cytotoxicity assay in bioprinted spheroids showed more chemoresistance to these structures when compared to those in 3D plate model. The extract (GE) showed chemosensitizer effects with cisplatin in bladder cancer cells. This can open the possibility of reduction of the dose of cisplatin and new therapeutic options to treat bladder cancer.

Funding

Miranda, M.A. acknowledges grant #2017/09025-7 from São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP). The authors also acknowledge the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of National Institutes of Health (RCMI) 2454MD007582-34A1 grant and NSF-CREST Center for Complex Materials Design for Multidimensional Additive Processing (CoManD) award # 1735968.

Abbreviations:

- Alg-Gel

alginate-gelatin

- BC

bladder cancer

- cDDP

cisplatin

- CI

combination index

- GA

glycoalkaloids

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- GE

glycoalkaloidic extract

- SM

solamargine

- SS

solasonine

- PDX

Patient Derived Xenografts

- 3D

three-dimensional

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Miranda M.A.: Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing original draft preparation, Reviewing and editing. Mondal, M., Chowdhury, N., Gebeyehu, A., Surapaneni, S.K., Amaral R.: Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis. Bentley, M.V.L.B.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resource. Pan, C-X: Resource. Marcato P.D., Singh, M.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing-Reviewing and Editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A, Cancer statistics, 2017, CA Cancer J. Clin. 67 (2017) 7–30, 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Shelley MD, Mason MD, Kynaston H, Intravesical therapy for superficial bladder cancer: a systematic review of randomised trials and meta-analyses, Cancer Treat. Rev. 36 (2010) 195–205, 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kolawole OM, Lau WM, Mostafid H, Khutoryanskiy VV, Advances in intravesical drug delivery systems to treat bladder cancer, Int. J. Pharm. 532 (2017) 105–117, 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.08.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Milowsky MI, Bryan Rumble R, Booth CM, Gilligan T, Eapen LJ, Hauke RJ, Boumansour P, Lee CT, Guideline on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer (European Association of Urology guideline): American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline endorsement, J. Clin. Oncol. 34 (2016) 1945–1952, 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.9797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Faba OR, Palou J, Breda A, Villavicencio H, High-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: update for a better identification and treatment, World J. Urol. 30 (2012) 833–840, 10.1007/s00345-012-0967-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Antoni S, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Znaor A, Jemal A, Bray F, Bladder cancer incidence and mortality: a global overview and recent trends, Eur. Urol. 71 (2017) 96–108, 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chamie K, Litwin MS, Bassett JC, Daskivich TJ, Lai J, Hanley JM, Konety BR, Saigal CS, Recurrence of high-risk bladder cancer: a population-based analysis, Cancer. 119 (2013) 3219–3227, 10.1002/cncr.28147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Huang CP, Chen CC, Shyr CR, The anti-tumor effect of intravesical administration of normal urothelial cells on bladder cancer, Cytotherapy. 19 (2017) 1233–1245, 10.1016/j.jcyt.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Davarpanah NN, Yuno A, Trepel JB, Apolo AB, Immunotherapy: a new treatment paradigm in bladder cancer, Curr. Opin. Oncol. 29 (2017) 184–195, 10.1097/CC0.0000000000000366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Loriot Y, Necchi A, Park SH, Garcia-Donas J, Huddart R, Burgess E, Fleming M, Rezazadeh A, Mellado B, Varlamov S, Joshi M, Duran I, Tagawa ST, Zakharia Y, Zhong B, Stuyckens K, Santiago-Walker A, De Porre P, O’Hagan A, Avadhani A, Siefker-Radtke AO, Erdafitinib in locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma, N. Engl. J. Med. 381 (2019) 338–348, 10.1056/nejmoal817323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Knowles MA, Hurst CD, Molecular biology of bladder cancer: new insights into pathogenesis and clinical diversity, Nat. Rev. Cancer 15 (2015) 25–41, 10.1038/nrc3817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Weinstein JN, Akbani R, Broom BM, Wang W, Verhaak RGW, McConkey D, Lerner S, Morgan M, Eley G, Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma, Nature. 507 (2014) 315–322, 10.1038/naturel2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Qin S, Cheng Y, Lei Q, Zhang A, Zhang X, Combinational strategy for high-performance cancer chemotherapy, Biomaterials (2018), 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cheng ML, Iyer G, Novel biomarkers in bladder cancer, Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 36 (2018) 115–119, 10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Doddapaneni R, Patel K, Chowdhury N, Singh M, Noscapine chemosensitization enhances docetaxel anticancer activity and nanocarrier uptake in triple negative breast cancer, Exp. Cell Res. 346 (2016) 65–73, 10.1016/j.yexcr.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Qi Q, Liu X, Li S, Joshi HC, Ye K, Synergistic suppression of noscapine and conventional chemotherapeutics on human glioblastoma cell growth, Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 34 (2013) 930–938, 10.1038/aps.2013.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].LI J, Larregieu CA, Benet LZ, Classification of natural products as sources of drugs according to the biopharmaceutics drug disposition classification system (BDDCS), Chin. J. Nat. Med. 14 (2016) 888–897, 10.1016/S1875-5364(17)30013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Newman DJ, Cragg GM, Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010, J. Nat. Prod. 75 (2012) 311–335, 10.1021/np200906s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Aljuffali IA, Fang C, Chen C, Fang J, Nano medicine as a Strategy for Natural Compound Delivery to Prevent and Treat Cancers, (2016), pp. 4219–4231, 10.2174/13816128226661606200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Milner SE, Brunton NP, Jones PW, O’Brien NM, Collins SG, Maguire AR, Bioactivities of glycoalkaloids and their aglycones from solanum species, J. Agric. Food Chem. 59 (2011) 3454–3484, 10.1021/jf200439q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lee KR, Kozukue N, Han JS, Park JH, Chang EY, Baek EJ, Chang JS, Friedman M, Glycoalkaloids and metabolites inhibit the growth of human colon (HT29) and liver (HepG2) cancer cells, J. Agric. Food Chem. 52 (2004) 2832–2839, 10.1021/jfO30526d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ikeda T, Tsumagari H, Honbu T, Nohara T, Cytotoxic activity of steroidal glycosides from solanum plants, Biol. Pharm. Bull. 26 (2003) 1198–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kuo K-W, Hsu S-H, Li Y-P, Lin W-L, Liu L-F, Chang L-C, Lin C-C, Lin C-N, Sheu H-M, Anticancer activity evaluation of the Solanum glycoalkaloid solamargine, Biochem. Pharmacol. 60 (2000) 1865–1873, 10.1016/S0006-2952(00)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Daunter B, Cham BE, Solasodine glycosides. In vitro preferential cytotoxicity for human cancer cells, Cancer Lett. 55 (1990) 209–220, 10.1016/0304-3835(90)90121-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Munari CC, De Oliveira PF, Campos JCL, Martins SDPL, Da Costa JC, Bastos JK, Tavares DC, Antiproliferative activity of Solanum lycocarpum alkaloidic extract and their constituents, solamargine and solasonine, in tumor cell lines, J. Nat. Med. 68 (2014) 236–241, 10.1007/s11418-013-0757-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Cham BE, Daunter B, Solasodine glycosides. Selective cytotoxicity for cancer cells and inhibition of cytotoxicity by rhamnose in mice with sarcoma 180, Cancer Lett. 55 (1990) 221–225, 10.1016/0304-3835(90)90122-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cham BE, Daunter B, Evans RA, Topical treatment of malignant and premalignant skin lesions by very low concentrations of a standard mixture (BEC) of solasodine glycosides, Cancer Lett. 59 (1991) 183–192, 10.1016/0304-3835(91)90140-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Carvalho IPS, Miranda MA, Silva LB, Chrysostomo-massaro TN, Paschoal JAR, In vitro anticancer activity and physicochemical properties of Solanum lycocarpum alkaloidic extract loaded in natural lipid-based nanoparticles, 28 (2019) 5–14, 10.1016/j.colcom.2018.ll.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Miranda MA, Marcato PD, Carvalho IPS, Assessing the Cytotoxic Potential of Glycoalkaloidic Extract in Nanoparticles Against Bladder Cancer Cells, (2019), pp. 1–12, 10.1111/jphp.13145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Edmondson R, Broglie JJ, Adcock AF, Yang L, Three-dimensional cell culture systems and their applications in drug discovery and cell-based biosensors, Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 12 (2014) 207–218, 10.1089/adt.2014.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jamieson LE, Harrison DJ, Campbell CJ, Chemical analysis of multicellular tumour spheroids, Analyst. 140 (2015) 3910–3920, 10.1039/C5AN00524H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Abbott A, Biology’s new dimension, Nature. 424 (2003) 870–872, 10.1038/424870a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fitzgerald KA, Malhotra M, Curtin CM, O’Brien FJ, O’Driscoll CM, Life in 3D is never flat: 3D models to optimise drug delivery, J. Control. Release 215 (2015) 39–54, 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lee J, Lilly D, Doty C, Podsiadlo P, Kotov N, In vitro toxicity testing of nanoparticles in 3D cell culture, Small. 5 (2009) 1213–1221, 10.1002/smll.200801788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Baker BM, Chen CS, Deconstructing the third dimension – how 3D culture microenvironments alter cellular cues, J. Cell Sci. 125 (2012) 3015–3024, 10.1242/jcs.079509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Quail D, Joyce J, Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis, Nat. Med. 19 (2013) 1423–1437, 10.1038/nm.3394.Microenvironmental. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ozbolat IT, Moncal KK, Gudapati H, Evaluation of bioprinter technologies, Addit. Manuf. 13 (2017) 179–200, 10.1016/j.addma.2016.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zhu W, Holmes B, Glazer RI, Zhang LG, 3D printed nanocomposite matrix for the study of breast cancer bone metastasis, Nanomedicine Nanotechnology, Biol. Med. 12 (2016) 69–79, 10.1016/j.nano.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Casey D, Using C, Booking G, Programming CMI, Jacobs T, Guest Editorial 13 (2014) 341–342, 10.1057/rpm.2014.28. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Liu X, Krawczyk E, Suprynowicz FA, Palechor-Ceron N, Yuan H, Dakic A, Simic V, Zheng YL, Sripadhan P, Chen C, Lu J, Hou TW, Choudhury S, Kallakury B, Tang D, Darling T, Thangapazham R, Timofeeva O, Dritschilo A, Randell SH, Albanese C, Agarwal S, Schlegel R, Conditional reprogramming and long-term expansion of normal and tumor cells from human biospecimens, Nat. Protoc. 12 (2017) 439–451, 10.1038/nprot.2016.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gheibi P, Zeng S, Son KJ, Vu T, Ma AH, Dall’Era MA, Yap SA, De Vere White RW, Pan CX, Revzin A, Microchamber cultures of bladder cancer: a platform for characterizing drug responsiveness and resistance in PDX and primary cancer cells, Sci. Rep. 7 (2017) 1–10, 10.1038/s41598-017-12543-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Miranda MA, Magalhães LG, Fabiane R, Tiossi J, Kuehn CC, Evaluation of the Schistosomicidal Activity of the Steroidal Alkaloids From Solanum lycocarpum Fruits, (2012), pp. 257–262, 10.1007/s00436-012-2827-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Chou T, Theoretical Basis, Experimental Design, and Computerized Simulation of Synergism and Antagonism in Drug Combination Studies, (2007), 10.1124/pr.58.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Godugu C, Doddapaneni R, Singh M, Honokiol nanomicellar formulation produced increased oral bioavailability and anticancer effects in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 153 (2017) 208–219, 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Vashisth P, Bellare JR, Development of hybrid scaffold with biomimetic 3D architecture for bone regeneration, Nanomedicine Nanotechnology, Biol. Med. 14 (2018) 1325–1336, 10.1016/j.nano.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Medeiros Borsagli FGL, Carvalho IC, Mansur HS, Amino acid-grafted and Nacylated chitosan thiomers: construction of 3D bio-scaffolds for potential cartilage repair applications, Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 114 (2018) 270–282, 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.03.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Godugu C, Patel AR, Desai U, Andey T, Sams A, Singh M, AlgiMatrix™ based 3D cell culture system as an in-vitro tumor model for anticancer studies, PLoS One 8 (2013), 10.1371/journal.pone.0053708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Sani IK, Marashi SH, Kalalinia F, Solamargine inhibits migration and invasion of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells through down-regulation of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 expression and activity, Toxicol. in Vitro 29 (2015) 893–900, 10.1016/j.tiv.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Cham BE, Drug therapy: Solamargine and other solasodine rhamnosyl glycosides as anticancer agents, Mod. Chemother. 2 (2013) 33–49, 10.4236/me.2013.22005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Miranda MA, Silva LB, Carvalho IPS, Amaral R, de Paula MH, Swiech K, Bastos JK, Paschoal JAR, Emery FS, dos Reis RB, Bentley MVLB, Marcato PD, Targeted uptake of folic acid-functionalized polymeric nanoparticles loading glycoalkaloidic extract in vitro and in vivo assays, Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 192 (2020) 111106, 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.111106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Al Sinani SS, Eltayeb EA, Coomber BL, Adham SA, Solamargine triggers cellular necrosis selectively in different types of human melanoma cancer cells through extrinsic lysosomal mitochondrial death pathway, Cancer Cell Int. 16 (2016) 11, 10.1186/sl2935-016-0287-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Shiu LY, Chang LC, Liang CH, Huang YS, Sheu HM, Kuo KW, Solamargine induces apoptosis and sensitizes breast cancer cells to cisplatin, Food Chem. Toxicol. 45 (2007) 2155–2164, 10.1016/j.fct.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Matsui Y, Watanabe J, Ikegawa M, Kamoto T, Ogawa O, Nishiyama H, Cancer-specific enhancement of cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity with triptolide through an interaction of inactivated glycogen synthase kinase-3β with p53, Oncogene. 27 (2008) 4603–4614, 10.1038/onc.2008.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Jiang G, Liu J, Ren B, Zhang L, Owusu L, Liu L, Zhang J, Tang Y, Li W, Anti-tumor and chemosensitization effects of Cryptotanshinone extracted from Salvia miltiorrhiza Bge. on ovarian cancer cells in vitro, J. Ethnopharmacol. 205 (2017) 33–40, 10.1016/j.jep.2017.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kyle AH, Huxham LA, Yeoman DM, Minchinton AI, Cancer therapy: preclinical limited tissue penetration of taxanes: a mechanism for resistance in solid tumors, 13 (2007) 2804–2811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Zhang YF, Zhang M, Huang XL, Fu YJ, Jiang YH, Bao LL, Maimaitiyiming Y, Zhang GJ, Wang QQ, Naranmandura H, The combination of arsenic and cryptotanshinone induces apoptosis through induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress-reactive oxygen species in breast cancer cells, Metallomics. 7 (2015) 165–173, 10.1039/c4mt00263f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Zhang ZW, Xiao J, Luo W, Wang BH, Chen JM, Caffeine suppresses apoptosis of bladder cancer RT4 cells in response to ionizing radiation by inhibiting ataxia telangiectasia mutated-Chk2-p53 axis, Chin. Med. J. 128 (2015) 2938–2945, 10.4103/0366-6999.168065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Laurenzana I, Caivano A, Trino S, De Luca L, La Rocca F, Simeon V, Tintori C, D’Alessio F, Teramo A, Zambello R, Traficante A, Maietti M, Semenzato G, Schenone S, Botta M, Musto P, Del Vecchio L, A Pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine compound inhibits Fyn phosphorylation and induces apoptosis in natural killer cell leukemia, Oncotarget 7 (2016), 10.18632/oncotarget.11496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Ding X, Zhu F-S, Li M, Gao S-G, Induction of apoptosis in human hepatoma SMMC-7721 cells by solamargine from Solanum nigrum L, J. Ethnopharmacol. 139 (2012) 599–604, 10.1016/j.jep.2011.ll.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Li X, Zhao Y, Wu WKK, Liu S, Cui M, Lou H, Solamargine induces apoptosis associated with p53 transcription-dependent and transcription-independent pathways in human osteosarcoma U2OS cells, Life Sci. 88 (2011) 314–321, 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Xie X, Zhu H, Yang H, Huang W, Wu Y, Wang Y, Luo Y, Wang D, Shao G, Solamargine triggers hepatoma cell death through apoptosis, Oncol. Lett. 10 (2015) 168–174, 10.3892/ol.2015.3194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Liang C, Liu L, Shiu L, Huang Y, Chang L, Kuo K, Action of solamargine on TNFs and cisplatin-resistant human lung cancer cells, 322 (2004) 751–758, 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Konopleva M, Konoplev S, Hu W, Zaritskey AY, Afanasiev BV, Andreeff M, Stromal cells prevent apoptosis of AML cells by up-regulation of anti-apoptotic proteins, Leukemia. 16 (2002) 1713–1724, 10.1038/sj.leu.2402608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Hu J, Xu M, Dai Y, Ding X, Xiao C, Ji H, Xu Y, Exploration of Bcl-2 family and caspases-dependent apoptotic signaling pathway in Zearalenone-treated mouse endometrial stromal cells, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 476 (2016) 553–559, 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.05.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Sun L, Zhao Y, Li X, Yuan H, Cheng A, Lou H, A lysosomal-mitochondrial death pathway is induced by solamargine in human K562 leukemia cells, Toxicol. Vitr. 24 (2010) 1504–1511, 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Knowlton S, Onal S, Yu CH, Zhao JJ, Tasoglu S, Bioprinting for cancer research, Trends Biotechnol. 33 (2015) 504–513, 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Samavedi S, Joy N, 3D printing for the development of in vitro cancer models, Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2 (2017) 35–42, 10.1016/j.cobme.2017.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Zhao Y, Yao R, Ouyang L, Ding H, Zhang T, Zhang K, Cheng S, Sun W, Three-dimensional printing of Hela cells for cervical tumor model in vitro, Biofabrication 6 (2014), 10.1088/1758-5082/6/3/035001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Stanton MM, Samitier J, Sánchez S, Bioprinting of 3D hydrogels, Lab Chip 15 (2015) 3111–3115, 10.1039/c51c90069g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Dai X, Ma C, Lan Q, Xu T, 3D bioprinted glioma stem cells for brain tumor model and applications of drug susceptibility, Biofabrication. 8 (2016) 45005, 10.1088/1758-5090/8/4/045005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Skardal A, Atala A, Biomaterials for integration with 3-D bioprinting, Ann. Biomed. Eng. 43 (2015) 730–746, 10.1007/s10439-014-1207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Sarker B, Rompf J, Silva R, Lang N, Detsch R, Kaschta J, Fabry B, Boccaccini AR, Alginate-based hydrogels with improved adhesive properties for cell encapsulation, Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 78 (2015) 72–78, 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Zehnder T, Sarker B, Boccaccini AR, Detsch R, Evaluation of an alginate-gelatine crosslinked hydrogel for bioplotting, Biofabrication 7 (2015), 10.1088/1758-5090/7/2/025001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Jang SH, Wientjes MG, Lu D, Au JLS, Drug delivery and transport to solid tumors, Pharm. Res. 20 (2003) 1337–1350, 10.1023/A:1025785505977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]