Abstract

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted training. Gastroenterology higher specialty training is soon to be reduced from 5 years to 4. The British Society of Gastroenterology Trainees Section biennial survey aims to delineate the impact of COVID-19 on training and the opinions on changes to training.

Methods

An electronic survey allowing for anonymised responses at the point of completion was distributed to all gastroenterology trainees from September to November 2020.

Results

During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, 71.0% of the respondents stated that more than 50% of their clinical time was mostly within general internal medicine. Trainees reported a significant impact on all aspects of their gastroenterology training due to lost training opportunities and increasing service commitments. During the first wave, 88.5% of the respondents reported no access to endoscopy training lists. Since this time, 66.2% of the respondents stated that their endoscopy training lists had restarted. This has resulted in fewer respondents achieving endoscopy accreditation. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused 42.2% of the respondents to consider extending their training to obtain the skills required to complete training. Furthermore, 10.0% of the respondents reported concerns of a delay to completion of training. The majority of respondents (84.2%) reported that they would not feel ready to be a consultant after 4 years of training.

Conclusions

Reductions in all aspects of gastroenterology training were reported. This is mirrored in anticipated concerns about completion of training in a shorter training programme as proposed in the new curriculum. Work is now required to ensure training is restored following the pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, endoscopy, endoscopic procedures

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this topic

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected training opportunities in gastroenterology internationally.

There were concerns reported by trainees in 2018 about the new Shape of Training programme.

What this study adds

All aspects of gastroenterology training were significantly disrupted during the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Trainees are concerned that a reduction in higher specialty training time will make competency achievement difficult without significant improvements and support for post-COVID-19 recovery.

10% of trainees may experience delays to completion of training as a consequence of the pandemic.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future

Emphasis must be placed on supporting the recovery of training for those who have worked through the COVID-19 pandemic to prevent the need for extending training time.

Further consideration must be given to workforce planning amid potential delays to completion of training.

As higher speciality training moves to a 4-year programme, significant changes must be made to training delivery to ensure delays to certificate of completion of training are attenuated; examples may include protected endoscopy training, immersion training and blocks of specialty-specific work.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a dramatic effect on all UK National Health Service (NHS) services and staff. Changes in institutional policies and redeployment to high-priority clinical areas have caused significant disruption to gastroenterology services and training.1 During the first UK wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, endoscopic activity fell to 5% of normal levels.2 While there is ongoing work to safely restore clinical services, the impact on training may be more difficult to resolve. Internationally, cross-sectional data have shown that endoscopy training came to a near-complete standstill.3 While this highlights the global challenge, it is difficult to draw conclusions for UK trainees from this study and in particular understand the impact on training. Similarly, the majority (97%) of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) outpatient clinics were changed from face-to-face (F2F) to virtual or telephone-based services, likely leading to challenges in supervision and trainee access.4

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the demands of general internal medicine (GIM) training were already highlighted as a significant barrier to gastroenterology training. Given the service demands during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is likely that this further increased and compounded the problem. Previously, 63.8% of trainees stated GIM had a negative impact on their training.5 Training prior to the COVID-19 pandemic remained challenging; only half (51.1%) of trainees in training reported completing colonoscopy certification by specialty training year 7 (ST7) in a survey.5

The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) workforce report suggests that increasing demand for gastroenterology services and retirements will lead to a requirement of 200 new gastroenterology trainees to be recruited per year.6 Currently there is funding for 100 posts, with no plans for additional funding at the time of writing. This does not take into consideration the potential effects of training delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Training in the UK is soon to change to the new Shape of Training (SoT) programme and there are concerns as to how effective this will be at preparing trainees.5 These include shortening higher specialty training (HST) from 5 to 4 years, earlier decisions on subspecialty interests and proportion of time spent on GIM.3

It is unclear how much the COVID-19 pandemic has affected trainee experience. It is important to acknowledge that many of these changes are driven by the appropriate prioritisation of ensuring safe medical care for all. However, as the COVID-19 pandemic improves, the resulting effects on training must be measured. In doing so, plans can be made to restore lost training opportunities to ensure future consultants are able to provide the best care and, given the potential for delays to training, the workforce is staffed correctly.

We present data assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on all aspects of training for gastroenterology trainees in the UK and on their current career plans. Furthermore, views on SoT were also sought to help guide policy making to ensure safe, highly skilled future consultant gastroenterologists.

Methods

The BSG Trainees Section (TS) undertakes a biennial survey of higher specialty trainees in the UK (HST). The survey questions are a combination of recurring questions intended to monitor training outcomes and new questions specific to current priorities. Priorities for the TS include measuring the impact of the current COVID-19 pandemic on gastroenterology training (including both endoscopic and non-endoscopic skills), SoT changes and ongoing workforce challenges facing gastroenterology. Questions were written by the authors based on previous iterations of the survey. Additional input was then sought from former BSG TS members who work closely with the Specialist Advisory Committee and from the BSG workforce lead.

The questionnaire was disseminated using a web-based survey tool (SurveyMonkey) to all gastroenterology HST.6 The survey was accessible to respondents from September to November 2020. Comparisons were made with 2018 survey data.5

The survey timeline was divided into three phases: pre, first wave and post first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (prior to March 2020, March 2020–June 2020 and post June 2020, respectively). This was based on government data on the COVID-19 pandemic.7

Results

In total, 51% (349 of 687) of HST completed the survey with representation across all training grades and regions of the UK. This represents an increase in the number of responses from the 2018 survey (47.8% response rate). The majority of the respondents were male (57.6%) and worked full time (88.0%) (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data of survey respondents

| Respondents, n (%) | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 201 (57.6) |

| Female | 136 (39.0) |

| Prefer not to say | 12 (3.4) |

| LTFT | |

| Yes | 37 (10.6) |

| No | 307 (88.0) |

| Prefer not to say | 5 (1.4) |

| Training grade | |

| ST3 | 53 (15.2) |

| ST4 | 79 (22.6) |

| ST5 | 61 (17.5) |

| ST6 | 76 (21.8) |

| ST7 | 44 (12.6) |

| Other* | 36 (10.3) |

| Academic training | |

| Yes | 27 (7.7) |

| No | 322 (92.3) |

*Includes academic clinical fellows, academic clinical lectures, research fellows and locum appointments.

LTFT, less than full time; ST, specialty training year.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

Training

During the COVID-19 pandemic, 3.6% of the respondents reported being able to achieve the competences set out by themselves in their personal development plan. During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, 206 of 290 (71.0%) respondents stated that more than 50% of their time was undertaken within GIM. Of those undertaking more than 50% GIM, 39.7% undertook only GIM. During the same time period, 6.9% of the respondents covered only inpatient gastroenterology with no GIM commitments.

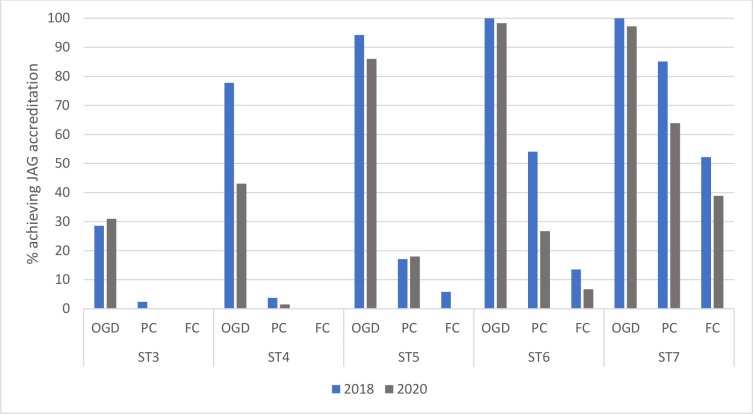

Trainees reported a significant impact on all aspects of their gastroenterology training due to the COVID-19 pandemic (figure 1). There was a reduction in access to outpatient clinics due to their GIM commitments or a reduction in available clinics (48.4% and 26.6% of the respondents, respectively). A decrease in gastroenterology referrals and specialty ward rounds was also reported, and once again in the majority these training opportunities were limited by GIM commitments (42.4% and 44.7%, respectively). After June 2020, trainees reported a recovery in training activity but not yet at the same levels seen prior to the start of the pandemic. There was no difference in recovery across different regions.

Figure 1.

Number of training opportunities pre-COVID-19 (prior to March 2020), during the first wave (March–June 2020) and following the first wave (after June 2020).

Endoscopy

During the first wave, 88.5% of the respondents reported no access to endoscopy training lists. Since this time period, 66.2% of the respondents stated that their endoscopy training lists had restarted, yet several barriers to accessing lists were still reported. These included limited or no availability of appropriate endoscopy training lists at their hospital, continued secondment to an emergency rota covering GIM and a lack of personal protection equipment (62.0%, 27.9%, 20.5% and 11.6%, respectively).

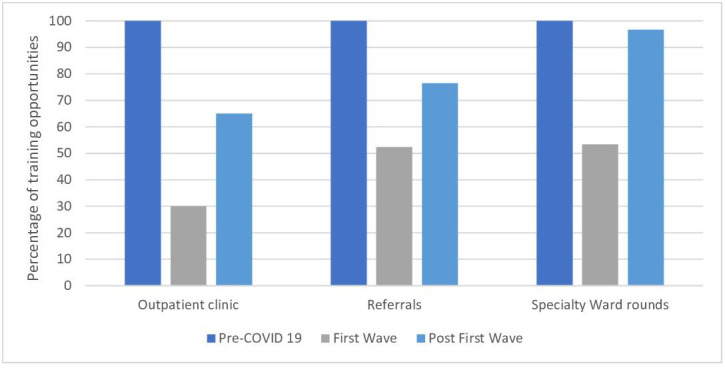

When compared with data from the 2018 BSG TS survey, the number of respondents achieving Joint Advisory Group (JAG) on gastrointestinal endoscopy accreditation in oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD), provisional colonoscopy and full colonoscopy has reduced at every stage of training (figure 2). The number achieving accreditation in OGD in ST4, provisional colonoscopy in ST6 and provisional colonoscopy in ST7 was significantly higher in 2018 compared with 2020 (78% vs 43% (p<0.005), 37% vs 27% (p=0.006), and 85% vs 64% (p=0.025), respectively).5

Figure 2.

Percentage of trainees who have achieved Joint Advisory Group (JAG) accreditation in oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD), provisional colonoscopy (PC) and full colonoscopy (FC) divided by specialty training year (ST).

Teaching

The majority of respondents reported alternative methods of teaching during this time period, with 75.7% stating that virtual teaching via online platforms had been arranged by their deanery. A further 45.1% stated that they had been directed to online training events, conferences and webinars, and 23.2% of the respondents had identified alternative methods of teaching via the use of social media. In total, 91.0% of the respondents found the teaching offered to be valuable.

Out-of-programme trainees

At the start of the pandemic, 20.1% of the trainees were out of programme (OOP), with the majority in a research post (57.7%). Excluding those on parental leave, 87.7% of those who were OOP at the start of the pandemic had their research or subspecialty work interrupted, with 63.2% reporting this clinical work would not count towards their training programme. The pandemic was reported to affect the ability to complete studies or higher degrees for 85.7% of the respondents. For 20% of trainees, funding for their post has also been affected.

Future workforce planning

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused 42.2% of trainees to consider extending their training to obtain the skills required to complete training. Furthermore, 26 respondents reported a delay in the date to obtain their certificate of completion of training (CCT).

The majority of the respondents continue to consider hepatology (50.0%) or IBD (48.8%) as their preferred subspecialty, although they have multiple areas of interest (table 2). To develop this specialist knowledge, trainees are considering post-CCT fellowships, advanced training programmes and OOP experiences (50.8%, 48.4% and 30.2%, respectively). Just over half (51.8%) of the respondents are planning to do research to support the development of their subspecialist interest. While 49% of the respondents are considering these opportunities at the current time, a further 32.6% of the respondents would consider these in the future. Despite this, only 55.6% of the respondents were confident that they would be able to develop the required expertise within their subspecialist interest. Of the respondents, 22% would be prepared to cease training in colonoscopy to allow greater focus on their subspecialty interest.

Table 2.

Percentage of trainees considering different subspecialty areas

| Subspecialty | Would consider undertaking as a consultant (%) |

| Hepatology | 50.0 |

| IBD | 48.8 |

| Nutrition | 19.5 |

| Advanced endoscopy (ERCP) | 27.2 |

| Advanced endoscopy (EUS) | 18.7 |

| Advanced endoscopy (upper GI) | 25.6 |

| Advanced endoscopy (lower GI/complex polyps) | 25.6 |

| Advanced endoscopy (enteroscopy) | 6.1 |

| Upper GI | 16.7 |

| Pancreas | 9.4 |

| Small bowel | 8.5 |

| Lower GI/BCSP | 16.3 |

| Functional bowel disorders | 6.9 |

| Pancreas/biliary tree | 15.9 |

BCSP, Bowel Cancer Screening Programme; ERCP, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS, Endoscopic ultrasound; GI, gastrointestinal; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

As consultants, 64.8% of the respondents would prefer to work full time and 32.0% less than full time (>60%). The majority (90.0%) are still aiming for a substantiative NHS consultant post. However, only 44.5% of the respondents were either very or somewhat confident that they would be able to obtain their desired job by the end of their HST.

Trainees’ views on SoT

The majority of the respondents (84.2%) reported that they would not feel ready to be a consultant after 4 years of HST in the current model. Additionally, half of the respondents (54.6%) stated that they would not be confident in selecting a subspecialty after 18 months of HST as is currently proposed. The majority of the respondents (64.3%) agreed that the third year of specialist training would be the most reasonable time point for this decision to occur.

The majority of the respondents (97.7%) continue to dual-accredit with GIM, but 65.8% stated that GIM training currently has a negative impact on their specialist training, with 46.7% of respondents stating that they would stop GIM training if given the opportunity. A quarter (25.7%) of the respondents still plan to pursue a consultant post with a GIM component. Of the respondents, 68% supported the idea of blocks of GIM to protect their gastroenterology training. Within a 4-year training programme, respondents felt less than 20% of their time should be GIM to allow for gastroenterology training objectives to be achieved.

Almost all respondents (96.8%) stated that gastroenterology HST should have at least 1-year experience on an out-of-hours upper gastrointestinal bleed rota. At present, 86% of trainees reported opportunities to perform endoscopy for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB). Of these, only 21.3% were part of an upper gastrointestinal bleed rota and 7.7% reported not having adequate supervision when performing endoscopy for UGIB.

Discussion

This is the largest survey of UK gastroenterology trainees examining all aspects of training. The increased level of response to previous years could suggest a greater desire by trainees to have their thoughts on training matters heard, which may indicate higher levels of concern. During the first wave of the pandemic there was a global loss of training time in endoscopy, clinics, referrals and specialty ward rounds. This was primarily due to the necessary clinical commitments in GIM to ensure safe clinical practice and patient safety were maintained. There remains a deficit in training opportunities when compared with prior to the COVID-19 pandemic; however, this appears to be gradually improving in the early stages.

The most significant concern to gastroenterology training remains gaining competence in endoscopic modalities, which is likely a multifactorial problem. The impact of the reduced training opportunities is most evident in the significant drop in ST4 trainees who are JAG-accredited in OGD. This is leading many trainees to consider post-CCT training prior to obtaining a consultant post, highlighting the importance of protecting trainee presence at endoscopy. Immersive training blocks, ‘tailored to the trainee’ endoscopy lists and ad hoc ‘buffer’ lists, have been shown to increase the number of endoscopies completed by trainees, without compromising patient safety.8 These measures could therefore help minimise delays to training. Furthermore, the quality of training can be improved by enhancing feedback, which is valued by trainees.9

Of the trainees, 10% have reported a delay to their CCT date and 32% plan to work less than full time as consultants. This will have significant ramifications to workforce planning and within a gastroenterology workforce which is already facing significant shortages.6 Retaining trainees is therefore crucial. The 2020 national training survey found 23% of all trainees felt burnt out and 40% found the work emotionally exhausting.10 Consultants in gastroenterology are also at the highest risk of burnout and further highlights the need for improvement.11 Heavy quantitative workloads and subjective time pressures are key predictors of burnout and therefore highlight potential targets for intervention to retain the workforce.12 Mentorship schemes within gastroenterology have also been shown to improve retention and recruitment and must therefore continue throughout and beyond the pandemic.13

Online teaching has been well received and has allowed more trainees to access teaching sessions. While there remain benefits to F2F teaching, such as greater interactions, online teaching increases the opportunity for individuals to attend teaching courses.14 The implementation of blended learning should be considered before the transition back to more traditional F2F teaching sessions. To continue the recovery of training, other measures such as the use of simulation training, alternative delivery of non-technical skills such as local endoscopy multi-disciplinary teams, JAG flexibility where possible with precertification periods, greater involvement in UGIB rotas and virtual subspecialty exposure should also be considered.8 9 15

UK research among trainees is in decline and is likely to be further negatively impacted by the effects of the UK withdrawal from the European Union.16 17 Our data have shown that the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the majority (87%) of trainees undertaking research. While offering their support to clinical services, in many cases (63%) this has not counted towards their training. To minimise these effects research time should be built into training or extensions considered for those OOP and trainee networks encouraged to easily allow involvement.18 Trainees are also at risk of losing research funding and therefore research councils will need to consider methods of supporting current and future trainees to maintain the standards of research within the UK.

Our data show that the vast majority of respondents (84%) do not feel 4 years is enough time to train to be a consultant, a viewpoint that has been consistently shown in previous surveys.5 As a result of the pandemic, 42% of the respondents reported that they would consider extending training due to the loss of training time. Interestingly, with this lost training time, the current programme would be of a similar length to the new SoT proposal. This challenge may be further compounded with the required GIM commitments. Given many issues predated COVID-19, an overhaul is needed to ensure high-quality training. The new SoT programme presents an opportunity to address these concerns raised by trainees.

Conclusion

Gastroenterology training has been significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic primarily due to loss of gastroenterology training opportunities and GIM demands. There remain concerns with the new SoT programme. Recovery of training should be prioritised to ensure trainees are able to reach their potential and support the understaffed consultant workforce. At this key moment, innovation will be necessary to overcome these challenges which predated the pandemic. This offers an opportunity to change the way training is organised and be innovative in solutions to support those impacted by COVID-19 to recover and create a novel and effective training programme in the new curriculum.

Footnotes

Collaborators: British Sciety of Gastroenterology Trainees Section: Abdullah Abbasi, Ruridh Allen, Aaron S Bancil, Fraser C Brown, Radha Gadhok, James Gulliver, Yazan Haddadin, Andreas Hadjinicolaou, Arif Hussenbux, Michael Johnston, lisa McNeill, Adnan Rahman, Uma Selvarajah, Elizabeth Sweeney.

Contributors: All authors helped design, complete and write the study. SR is acting as the guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

British Society of Gastroenterology Trainees Section:

Abdullah Abbasi, Ruridh Allen, Aaron S Bancil, Fraser C Brown, Radha Gadhok, James Gulliver, Yazan Haddadin, Andreas V Hadjinicolaou, Arif Hussenbux, Michael P Johnston, Lisa McNeill, Adnan Ur Rahman, Uma Selvarajah, and Elizabeth Sweeney

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Siau K, Iacucci M, Dunckley P, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on gastrointestinal endoscopy training in the United Kingdom. Gastroenterology 2020;159:1582–5. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rees CJ, East JE, Oppong K, et al. Restarting gastrointestinal endoscopy in the deceleration and early recovery phases of COVID-19 pandemic: guidance from the British Society of gastroenterology. Clin Med 2020;20:352–8. 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pawlak KM, Kral J, Khan R, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on endoscopy trainees: an international survey. Gastrointest Endosc 2020;92:925–35. 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kennedy NA, Hansen R, Younge L, et al. Organisational changes and challenges for inflammatory bowel disease services in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5. Clough J, FitzPatrick M, Harvey P, et al. Shape of training review: an impact assessment for UK gastroenterology trainees. Frontline Gastroenterol 2019;10:356–63. 10.1136/flgastro-2018-101168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gastroenterology BSo . British Society of gastroenterology workforce report 2021. Available: bsg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/British-Society-of-Gastroenterology-Workforce-Report-2019-.pdf

- 7. Official UK Coronavirus Dashboard: @PHE_uk, 2021. Available: https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/cases

- 8. Adu-Tei S, Raju SA, Marks LJS, et al. Letter: enhancing training opportunities for upper GI bleeding in Sheffield-a UK transferable model? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2021;53:1241–2. 10.1111/apt.16354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ratcliffe E, Subramaniam S, Ngu WS, et al. Endoscopy training in the UK pre-COVID-19 environment: a multidisciplinary survey of endoscopy training and the experience of reciprocal feedback. Frontline Gastroenterol 2022;13:39–44. 10.1136/flgastro-2020-101734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Trainig survey 2020. Available: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/nts-results-2020-summary-report_pdf-84390984.pdf

- 11. Rutter C. British Society of gastroenterology workforce report may 2021.

- 12. Kleiner S, Wallace JE. Oncologist burnout and compassion fatigue: investigating time pressure at work as a predictor and the mediating role of work-family conflict. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:639. 10.1186/s12913-017-2581-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smith KH, Hallett RJ, Wilkinson-Smith V, et al. Results of the British Society of gastroenterology supporting women in gastroenterology mentoring scheme pilot. Frontline Gastroenterol 2019;10:50–5. 10.1136/flgastro-2018-100971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hang S, Xiaoqing G. Determining the differences between online and face-to-face student–group interactions in a blended learning course. Internet and Higher Education 2021;39:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 15. FitzPatrick M, Clough J, Harvey P, et al. How can gastroenterology training thrive in a post-COVID world? Frontline Gastroenterol 2021;12:338–41. 10.1136/flgastro-2020-101601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McCay L. How will Brexit affect patient care and medical research? BMJ 2020;371:m4380. 10.1136/bmj.m4380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kurien M, Hopper AD, Barker J, et al. Is research declining amongst gastroenterology trainees in the United Kingdom? Clin Med 2013;13:118.2–9. 10.7861/clinmedicine.13-1-118a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Segal J, Widlak M, Ingram RJM, Brookes M, et al. What next for gastroenterology and hepatology trainee networks? lessons from our surgical colleagues. Frontline Gastroenterol 2022;13:82–5. 10.1136/flgastro-2021-101784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.