Abstract

目的

探究有幽门螺杆菌(Helicobacter pylori, H. pylori)感染家族史,发生和未发生H. pylori感染的儿童胃部菌群特点。

方法

分别采集患儿胃体和胃窦的黏膜标本,通过标本DNA提取、16S核糖体DNA(ribosomal DNA,rDNA)V3-V4区域PCR扩增、高通量测序、数据处理等步骤后,得到胃部黏膜菌群分析结果,将结果中有H. pylori感染家族史的标本根据是否发生H. pylori感染分为感染组(n=18)和非感染组(n=24),比较两组间菌群的α和β多样性、菌群丰度变化等指标,找出差异菌群,并对菌群功能进行预测分析。

结果

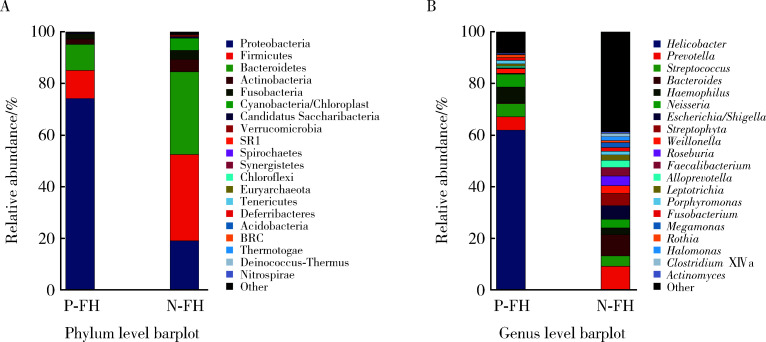

感染组与非感染组胃部菌群α多样性和β多样性之间差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05),感染组的菌群多样性要低于非感染组。菌群相对丰度方面,门水平占优势的主要有变形菌门(Proteobacteria)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)、拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)、放线菌门(Actinobacteria)和梭杆菌门(Fusobacteria); 属水平上,非感染组中拟杆菌(Bacteroides)、普雷沃氏菌(Prevotella)、链球菌(Streptococcus)和奈瑟菌(Neisseria)为优势菌种。差异物种方面,通过LEfSe分析,发现非感染组中属水平的拟杆菌属等的相对丰度显著高于感染组。功能预测发现,拟杆菌属与一些氨基酸和维生素代谢、丝裂原活化蛋白激酶(mitogen-activated protein kinase,MAPK)、哺乳动物雷帕霉素靶蛋白(mammalian target of rapamycin, mTOR)信号通路、安沙霉素(ansamycin)的合成相关通路均呈显著正相关。

结论

有H. pylori感染家族史的儿童中,发生H. pylori感染和未发生感染者的胃部菌群存在显著差异,拟杆菌可能与儿童是否发生H. pylori感染存在关联。

Keywords: 胃肠道微生物组, 儿童, 幽门螺杆菌, 病史记录

Abstract

Objective

To explore the characteristics of gastric microbiota in children with and without (Helicobacter pylori, H. pylori) infection who had family history of H. pylori infection.

Methods

Mucosal biopsy samples of the gastric corpus and gastric antrum were collected during the gastroscope. And the gastric mucosa flora's information of the two groups of children were obtained after sample DNA extraction, PCR amplification of the 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) V3-V4 region, high-throughput sequencing and data processing. All the samples with family history of H. pylori infection were divided into two groups, the H. pylori infection group (n=18) and the H. pylori non-infection group (n=24). Then the α-, β-diversity and bacteria abundance of the gastric microbiota were compared between the H. pylori infection and non-infection groups at different taxonomic levels. The differential microbiota was found out by LEfSe analysis, and then the function of microbiota predicted using phylogenetic investigation of communities by reconstruction of unobserved states (PICRUSt) method.

Results

There was statistically significant difference in α-diversity (P < 0.05) between the two groups, indicating that the H. pylori non-infection group had higher microbial richness than the H. pylori infection group. Moreover, the β-diversity was significantly different as well (P < 0.05), which meant that the microbiota composition of the two groups was different. At the phyla level, Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroides, Actinobacteria, and Fusobacteria were dominant in the two groups. At the genus level, Bacteroides, Prevotella, Streptococcus, and Neisseria, etc. were dominant in the H. pylori non-infected group. Meanwhile, Helicobacter and Haemophilus etc. were dominant in the H. pylori infected group. LEfSe analysis showed that the relative abundance of Bacteroides etc. at the genus level in the H. pylori non-infected group was significantly higher than that in the H. pylori infected group. Functional prediction showed that Bacteroides were positively correlated with amino acid and vitamin metabolism, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway and ansamycin synthesis pathway.

Conclusion

The gastric microbiota between H. pylori positive and H. pylori negative in children with family history of H. pylori infection is significant different. Some gastric microbiota, such as Bacteroides, may have a potential relationship with H. pylori infection in children.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal microbiome, Child, Helicobacter pylori, Medical history taking

幽门螺杆菌(Helicobacter pylori,H. pylori)感染目前已成为世界范围内亟待解决的健康问题之一,有研究指出,大多数H. pylori感染主要发生在儿童时期,所以儿童H. pylori感染问题正日益成为人们关注的焦点[1]。现代流行病学研究发现,儿童获得H. pylori感染的一个重要方式是家庭内传播,与H. pylori感染阳性的家庭成员共同生活的儿童发生H. pylori感染的概率将大大增加[2-3]。然而,结合临床观察我们发现,有些家庭成员中有明确H. pylori感染病史的儿童实际却并未发生感染,其原因可能是菌株、生活环境、个体基因、免疫状态等多种因素共同参与相互作用的结果[4-5]。近年来,随着现代分子生物学技术的快速发展,人体正常菌群对维护人类健康作用的相关研究也越来越深入,研究发现菌群紊乱对某些疾病的发生发展会产生重要作用。同样,胃部菌群作为胃肠道微生态系统的重要成员,其在胃肠道各种疾病发生发展中发挥的作用也逐渐被人们认识[6]。但是,关于有H. pylori感染家族史的儿童胃部菌群有何特点,目前还鲜有研究,解决这些问题有助于更深刻地认识H. pylori感染家族史对儿童H. pylori感染的影响。

本研究通过对儿童胃黏膜标本进行菌群16S核糖体DNA(ribosomal DNA,rDNA)测序分析,比较有H. pylori家族史的发生和未发生H. pylori感染的患儿胃部菌群构成特点及差异,对差异菌群的功能进行预测分析,旨在为探究儿童H. pylori感染的致病机制及儿童H. pylori相关疾病的微生态治疗及预防提供新的思路。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 研究对象

选取2019年3—7月就诊于北京大学第三医院儿科消化门诊的儿童,所有患儿均来自北京地区,家庭经济收入水平相近。入组标准: 1~16岁,因胃肠疾病就诊于儿科消化门诊,按正常计划需要进行胃镜检查,同时合并H. pylori感染家族史。排除标准: (1)4周内服用过质子泵抑制剂、H2受体拮抗剂、抑酸剂、抗生素、黏膜保护剂或益生菌等药物; (2)最终诊断为嗜酸性粒细胞胃肠炎或炎症性肠病等其他疾病; (3)无法耐受内镜检查。

最终共纳入42例患者,其中合并H. pylori感染者18例,年龄(11.0±1.6)岁; H. pylori非感染者24例,年龄(10.9±2.5)岁; 两组患儿年龄构成差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。本研究经过北京大学第三医院医学科学研究伦理委员会批准(M2019066)。

1.2. 标本采集

患儿均签署知情同意书,除正常胃镜取材送组织病理检查外,每位患儿在胃体和胃窦分别再取1份标本,保存于-80 ℃并尽快进行16S rDNA测序分析。H. pylori感染的诊断由下列任何一项检查的阳性结果确认: (1)细菌培养阳性,(2)组织病理学检查阳性。与患儿平日共餐的任何亲属有胃部症状并行胃镜检查确诊合并H. pylori感染则判定为H. pylori感染家族史阳性。

1.3. DNA提取和16S rRNA基因扩增测序

使用QIAamp® PowerFecal DNA试剂盒(Qiagen, Hilden, Germany)提取黏膜标本中的细菌总DNA,提取步骤按照说明书进行。利用特异性引物对细菌16S核糖体RNA基因的V3-V4区进行扩增。正向引物序列为(5′-3′): CCTACGGGRSGCAGCAG (341F),反向引物序列为(5′-3′): GGACTACVVGGGTATCTAATC (806R)。将基因组DNA稀释后进行PCR扩增,扩增预混液使用KAPA library HiFi Hotstart ReadyMix,确保PCR反应进行的准确性和高效性。扩增子经2%(质量分数)琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测,并由AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, U.S.)回收。用Nano-Drop 2000分光光度计(Thermo Scientific, MA, USA)检测总DNA品质,用Qubit® 2.0 (Invitrogen, U.S.)检测DNA总质量。建库后,扩增子在Illumina MiSeq平台(Illumina, CA, USA)上采用双末端(paired-end)测序法进行测序,并剔除低质量和错误的引物序列。利用Usearch软件去除嵌合体并进行聚类分析,即将所有序列按照丰度从高到低排序,然后以97%的相似性聚类成为操作分类单元(operational taxonomic units,OTU),记录每个样本匹配的OTU序列数量。为了减少不同样本测序数据大小所引起的偏倚,将OTU序列数据进行均一化处理,选取出现频率最高的OTU作为代表序列,根据RDP数据库(http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/)进行物种注释分析。

1.4. LEfSe分析和PICRUSt功能预测

LEfSe分析是采用线性判别分析(linear discri-minant analysis,LDA)来估算不同组间菌群丰度对差异影响的大小,PICRUSt软件(http://picrust.github.io/picrust)可以根据16S rDNA数据和基因组数据库对微生物群落进行宏基因组功能预测。首先将16S rDNA原始数据标准化,然后将数据映射到构建好的已测序基因组的功能基因构成表,从而得到功能预测结果, 最后,将LEfSe分析得到的差异菌群与预测的代谢途径进行关联,找出其对物种代谢通路的影响。

1.5. 统计学分析

微生物的α多样性可以用来反映物种的丰富程度,可用Shannon指数和Simpson指数描述。用柱状图表现各样本在不同分类情况下菌群的分布情况。采用t检验和Pearson’s卡方检验对定量和分类变量进行统计比较,使用SPSS (21.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA)统计软件,其中α多样性指数采用秩和检验计算(用R软件包中的wilcox. test函数进行两组之间的比较,kruskal. test函数进行两组以上的比较)。β多样性指数(Anosim)采用R软件包中R vegan软件(https://www.r-project.org)计算,以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1. α多样性和β多样性分析

对所有胃黏膜样本的微生物16S rDNA的V3-V4区进行测序,经过DNA提取、拼接、去除嵌合体后,共收集到3 885 201条有效序列,平均每个样本为35 002条(28 787~38 753条),有效序列的平均读长为416 bp (404~424 bp)。首先对两组标本的α多样性和β多样性进行比较(图 1),其中反映微生物α多样性的Shannon指数(图 1A)在两组间差异有统计学意义(P=0.000 71),Simpson指数(图 1B)在两组间差异也有统计学意义(P=0.000 33),提示在有H. pylori感染家族史的儿童中,非感染组胃部菌群的α多样性显著高于感染组,即非感染组胃部菌群的多样性和菌群的均一度要高于H. pylori感染组。进一步对两组标本间的β多样性指数进行分析,通过基于加权UniFrac的Anosim分析比较样本之间微生物群落构成的相似性(图 1C),发现两组之间β多样性差异也有统计学意义(P=0.003),提示两组之间胃部菌群的构成也有所不同。以上结果表明,有H. pylori感染家族史的儿童中,H. pylori非感染组和H. pylori感染组患儿胃部菌群的丰度和构成存在显著差异。

图 1.

家族史阳性的H. pylori感染组和非感染组的α多样性和β多样性比较

The alpha and beta diversity index of H. pylori positive and negative group with family history

A, Shannon index; B, Simpson index; C, Anosim index. In Shannon and Simpson index, each box plot represents the minimum value, interquartile range, median, and maximum value. In Anosim index, the abscissa represents different groups and the ordinate represents the rank. If the Between group is higher than other groups, it indicates that the intra-group difference is greater than the inter-group difference. If R>0, indicating that the intra-group difference is greater than the inter-group. If R < 0, indicates that intra-group difference is greater than inter-group. N-FH, H. pylori negative with family history; P-FH, H. pylori positive with family history.

2.2. 优势物种丰度比较

根据测序结果,选取每个样本在微生物门水平(图 2A)和属水平(图 2B)排名前20的物种,生成物种相对丰度的累加图(图 2),结果如表 1所示。

图 2.

家族史阳性的H. pylori感染组和非感染组物种相对丰度比较

Profiling histogram of H. pylori positive and negative group with family history at different classification levels

A, phylum level; B, genus level.

表 1.

家族史阳性的H. pylori感染组和非感染组菌群丰度情况

Microbiota abundance of H. pylori positive and negative group with family history

| Items | % | Items | % | |

| Phylum level | Genus level | |||

| Positive | Positive | |||

| Proteobacteria | 74.16 | Helicobacter | 61.89 | |

| Firmicutes | 10.89 | Haemophilus | 5.16 | |

| Bacteroidetes | 10.13 | Prevotella | 5.16 | |

| Actinobacteria | 2.05 | Neisseria | 5.11 | |

| Fusobacteria | 1.89 | Streptococcus | 5.10 | |

| Negative | Negative | |||

| Firmicutes | 33.46 | Bacteroides | 9.10 | |

| Bacteroidetes | 32.09 | Prevotella | 8.25 | |

| Proteobacteria | 18.99 | Escherichia | 5.33 | |

| Actinobacteria | 4.74 | Streptococcus | 4.00 | |

| Fusobacteria | 3.51 | Rothia | 3.75 |

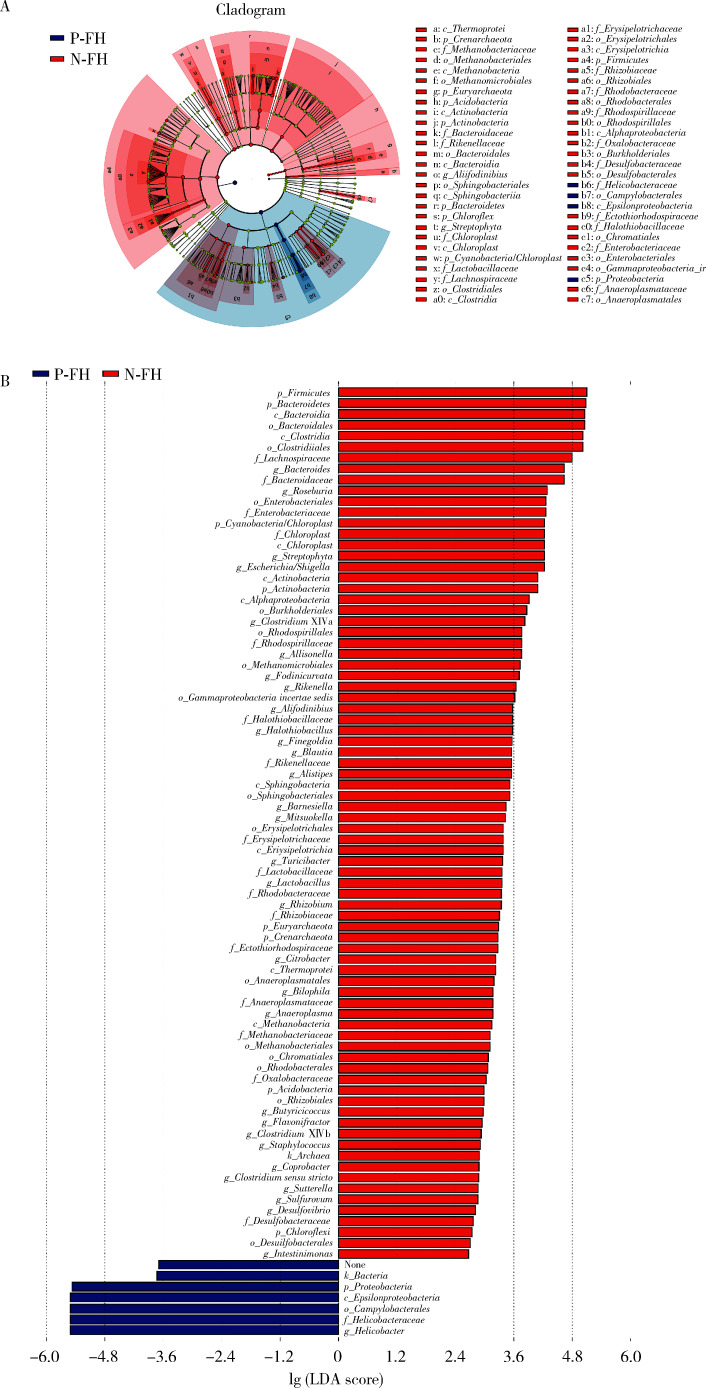

2.3. 组间物种差异分析

两组间菌群的构成有所差异,进一步对差异菌群进行分析。采用LEfSe分析法找出各组中差异有统计学意义的生物标识,首先绘制进化分支图(图 3A),从图中可以观察到不同组别中起重要作用的菌群,然后将LDA值设置为2.0,绘制LDA值柱状图(图 3B),在家族史阳性的H. pylori感染组中,H. pylori、空肠弯曲菌(Campylobacter)等物种相对丰度升高,而在H. pylori非感染组中,门水平的厚壁菌门(Firmicutes),纲和目水平的梭状芽孢杆菌(Clostridiales)和属水平的拟杆菌(Bacteroidetes)等的相对丰度显著升高。

图 3.

家族史阳性的H. pylori感染组和非感染组的差异菌群分析

Differential microbiota analysis of H. pylori positive and negative group with family history

A, cladogram for bacterial abundance. Nodes of different colors represent the microbiome that plays an important role in the group. Yellow nodes represent the non-important microbiome. B, histogram of the linear discriminant analysis (LDA) scores computed for differentially abundant bacterial taxa until class level. N-FH, H. pylori negative with family history; P-FH, H. pylori positive with family history.

2.4. 菌群功能预测

利用基于16S rRNA基因测序数据的PICRUSt方法对两组间胃黏膜微生物群的功能进行预测,H. pylori非感染组的细胞膜转运、转录、碳水化合物代谢等功能基因更为明显(图 4A),此外,通过关联差异菌群和KEGG(Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes)通路的影响,可见拟杆菌(Bacteroides)与一些氨基酸和维生素代谢、丝裂原活化蛋白激酶(mitogen-activated protein kinase,MAPK)、哺乳动物雷帕霉素靶蛋白(mammalian target of rapamycin,mTOR)信号通路、安沙霉素(ansamycin)的合成相关的通路均呈显著正相关(图 4B)。

图 4.

家族史阳性的H. pylori感染组和非感染组的菌群功能分析

Function analysis of H. pylori positive and negative group with family history

A, histogram of the linear discriminant analysis (LDA) scores for divergent gene functions between H. pylori positive and negative patients. B, correlations among metabolic pathways and various microbial taxa. The labels along the top of the figure outline the predicted metabolic pathways. Labels on the left show the different species. The bar on the right shows correlations, with red indicating a positive correlation and blue indicating a negative correlation. N-FH, H. pylori negative with family history; P-FH, H. pylori positive with family history. MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin.

3. 讨论

H. pylori感染与儿童慢性胃炎、消化性溃疡等疾病的发生有着十分密切的关系[7]。尽管关于H. pylori感染的传播方式目前尚无定论,但流行病学研究显示,儿童H. pylori感染呈现明显的家庭内聚集现象,说明H. pylori家庭内传播是儿童感染H. pylori的一个重要方式。然而在临床实践中,我们发现并非每一位有明确H. pylori家族史的儿童都发生H. pylori感染,本研究基于细菌16S rDNA测序,从儿童胃部菌群方面对有H. pylori家族史的感染情况不同的儿童进行了比较。

本研究结果显示,在有家族成员明确H. pylori感染病史的情况下,H. pylori感染组和非感染组儿童的胃部菌群α和β多样性都存在明显差异,即两者的菌群丰度和构成都各不相同,这与之前Llorca等[8]和彭贤慧等[9]的研究结果类似,但上述研究的对象主要集中在成人,且并未进一步对有无家族史进行分类分析。Bik等[10]对23名成人的胃黏膜菌群进行分析后发现,H. pylori感染组和非感染组的菌群构成无明显差异,这可能与不同研究所用检测方法不同以及不同地域人群菌群构成不同有关。本研究进一步对两组样本的差异物种进行LEfSe分析发现,在H. pylori非感染组中,属水平的拟杆菌、纲和目水平的梭状芽孢杆菌等处于明显优势地位,即这些菌群在有家族史的H. pylori阴性儿童胃部菌群中与H. pylori阳性儿童相比存在差异。

关于H. pylori感染与胃部菌群紊乱的关系,目前同样尚无定论。有研究显示,H. pylori可能会通过改变周围环境的pH值、释放尿素酶、破坏黏液层等方式对胃部其他菌群造成直接或间接的影响[11]。也有观点认为,胃部的其他菌群也会对H. pylori的感染、定植等产生影响,如Delgado等[12]分离了10株不同的乳酸杆菌(Lactobacillus spp.),发现某些种属的乳酸杆菌具有拮抗和消灭H. pylori的作用; Ascencio等[13]的研究表明,一些蓝杆藻菌属(Cyanothece spp.)的胞外多糖可以抑制H. pylori对胃上皮细胞的附着。

结合本研究结果我们推测,有些儿童之所以能够在有H. pylori感染的家庭中自己未发生感染,胃部菌群可能在其中也发挥了作用,如差异菌群拟杆菌就可能与H. pylori感染之间存在关联。有研究发现,拟杆菌的荚膜多糖可以通过激活人体CD4+T细胞分泌白细胞介素(interleukin, IL)-10,从而抑制肠道的炎症性疾病[14]。

本研究进一步对两组间的差异菌群进行了功能预测分析,从实验结果可以看到,差异菌群中的拟杆菌属在许多方面都发挥了重要作用: (1)拟杆菌可以增加组氨酸、酪氨酸、维生素B1和维生素B6代谢,而组氨酸和维生素是H. pylori生长、繁衍的必须营养物质[15],酪氨酸的磷酸化信号途径对于H. pylori粘附于胃上皮有重要的作用[16]; (2)拟杆菌在MAPK和mTOR信号通路上有正向作用,这些信号通路可以激活人体产生免疫细胞因子,抵抗H. pylori的入侵[17-18]; (3)拟杆菌可以促进合成安沙霉素,这是一类重要的抗生素,其代表成员利福平(rifampicin)可能更为大家所熟知,而这类合成的化合物可以直接杀伤H. pylori。当然,还需要更多的基础实验来支持上述这些结论。

本研究也存在一些不足,如研究入组的样本量尚少,需要更大的样本量和更多中心的研究来证明研究的结论; 本研究为横断面研究,若能够对患者发病前后多点进行采样研究菌群的变化,结果会更有说服力; 另外,若想进一步说明菌群之间的因果关系,还需进行无菌动物和相关细胞实验来提供更客观的证据。

综上所述,有H. pylori感染家族史的儿童中,发生H. pylori感染和未发生H. pylori感染的患儿胃部菌群有明显差异,一些胃部菌群(如拟杆菌)可能与H. pylori感染存在关联。探究儿童胃部微生态系统可能为进一步了解H. pylori感染的发病机制提供依据,也可能为儿童H. pylori感染的微生态治疗及预防提供新的思路。

Funding Statement

儿童示范性新药临床评价技术平台建设(2017ZX09304029)

Supported by the Construction of Technical Platform for Clinical Evaluation of Children's Demonstrative New Drugs(2017ZX09304029)

References

- 1.Misak Z, Hojsak I, Homan M. Review: Helicobacter pylori in pediatrics. Helicobacter. 2019;24(Suppl 1):e12639. doi: 10.1111/hel.12639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weyermann M, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H. Acquisition of Helicobacter pylori infection in early childhood: Independent contributions of infected mothers, fathers, and siblings. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(1):182–189. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ueno T, Suzuki H, Hirose M, et al. Influence of living environment during childhood on Helicobacter pylori infection in Japanese young adults. Digestion. 2020;101(6):779–784. doi: 10.1159/000502574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polk DB, Peek RM. Helicobacter Pylori: Gastric cancer and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(6):403–414. doi: 10.1038/nrc2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waskito LA, Salama NR, Yamaoka Y. Pathogenesis of Helicobac-ter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2018;23(Suppl 1):e12516. doi: 10.1111/hel.12516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan R, Guo Y, Gong Q, et al. Microbiological evidences for gastric cardiac microflora dysbiosis inducing the progression of inflammation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35(6):1032–1041. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.中华医学会儿科学分会消化学组, 《中华儿科杂志》编辑委员会 儿童幽门螺杆菌感染诊治专家共识. 中华儿科杂志. 2015;53(7):496–498. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2015.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llorca L, Pérez-Pérez G, Urruzuno P, et al. Characterization of the gastric microbiota in a pediatric population according to Helicobacter pylori status. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(2):173–178. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.彭 贤慧, 周 丽雅, 何 利华, et al. 幽门螺杆菌感染者胃内菌群特征分析. 胃肠病学和肝病学杂志. 2017;26(6):658–663. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-5709.2017.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bik EM, Eckburg PB, Gill SR, et al. Molecular analysis of the bacterial microbiota in the human stomach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(3):732–737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506655103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruno G, Rocco G, Zaccari P, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric dysbiosis: Can probiotics administration be useful to treat this condition? Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2018;2018:6237239. doi: 10.1155/2018/6237239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delgado S, Leite AM, Ruas-Madiedo P, et al. Probiotic and technological properties of Lactobacillus spp. strains from the human stomach in the search for potential candidates against gastric microbial dysbiosis. Front Microbiol. 2015;5:766. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ascencio F, Gama NL, Philippis RD, et al. Effectiveness of Cyanothece spp. and Cyanospira capsulata exocellular polysaccharides as antiadhesive agents for blocking attachment of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric cells. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2004;49(1):64–70. doi: 10.1007/BF02931648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorca GL, Wadstrom T, Valdez GF, et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus autolysins inhibit Helicobacter pylori in vitro. Curr Micro-biol. 2001;42(1):39–44. doi: 10.1007/s002840010175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nedenskov P. Nutritional requirements for growth of Helicobacter pylori. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60(9):3450–3453. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.9.3450-3453.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayashi S, Sugiyama T, Asaka M, et al. Modification of Helicobacter pylori adhesion to human gastric epithelial cells by antiadhesion agents. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(Suppl 9):56S–60S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunne C, Dolan B, Clyne M. Factors that mediate colonization of the human stomach by Helicobacter pylori. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(19):5610–5624. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i19.5610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slomiany BL, Slomiany A. Involvement of p38 MAPK-dependent activator protein (AP-1) activation in modulation of gastric mucosal inflammatory responses to Helicobacter pylori by ghrelin. Inflammopharmacology. 2013;21(1):67–78. doi: 10.1007/s10787-012-0141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]