Abstract

Background:

Limited space and resources are potential obstacles to infection prevention and control (IPAC) measures in in-centre hemodialysis units. We aimed to assess IPAC measures implemented in Quebec’s hemodialysis units during the spring of 2020, describe the characteristics of these units and document the cumulative infection rates during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods:

For this cross-sectional survey, we invited leaders from 54 hemodialysis units in Quebec to report information on the physical characteristics of the unit and their perceptions of crowdedness, which IPAC measures were implemented from Mar. 1 to June 30, 2020, and adherence to and feasibility of appropriate IPAC measures. Participating units were contacted again in March 2021 to collect information on the number of COVID-19 cases in order to derive the cumulative infection rate of each unit.

Results:

Data were obtained from 38 of the 54 units contacted (70% response rate), which provided care to 4485 patients at the time of survey completion. Fourteen units (37%) had implemented appropriate IPAC measures by 3 weeks after Mar. 1, and all 38 units had implemented them by 6 weeks after. One-third of units were perceived as crowded. General measures, masks and screening questionnaires were used in more than 80% of units, and various distancing measures in 55%–71%; reduction in dialysis frequency was rare. Data on cumulative infection rates were obtained from 27 units providing care to 4227 patients. The cumulative infection rate varied from 0% to 50% (median 11.3%, interquartile range 5.2%–20.2%) and was higher than the reported cumulative infection rate in the corresponding region in 23 (85%) of the 27 units.

Interpretation:

Rates of COVID-19 infection among hemodialysis recipients in Quebec were elevated compared to the general population during the first year of the pandemic, and although hemodialysis units throughout the province implemented appropriate IPAC measures rapidly in the spring of 2020, many units were crowded and could not maintain physical distancing. Future hemodialysis units should be designed to minimize airborne and droplet transmission of infection.

Since March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has completely disrupted the lives of Canadians; for the 24 000 vulnerable Canadians receiving in-centre hemodialysis, 1 its effects are especially grave. Case-fatality rates from COVID-19 are reported at 20%–30% in patients receiving hemodialysis — 10 times that in the general population. 2–8 Yet self-isolation to avoid exposure is impossible. Most patients must leave their homes 3 times a week to receive their life-saving treatments. Each treatment is typically performed for 3–5 hours in an open space shared with several other patients9 and involves frequent contact with health care workers. Exposure to SARS-CoV-2 may also occur during transport and in the waiting area before and after dialysis.

Outbreaks of COVID-19 within hemodialysis units can have disastrous consequences.10,11 Although the risk of outbreaks in dialysis units was recognized early on during the pandemic,10 implementation of strict infection prevention and control (IPAC) measures in hemodialysis units is challenging. Most North American installations were not designed to prevent respiratory virus transmission. Many are crowded, with minimal distance between treatment stations and few, if any, single-patient rooms.

Quebec was the first Canadian province to experience intense community transmission of SARS-CoV-2.12 Although several expert panels issued recommendations for outbreak prevention strategies for hemodialysis units,9,13–15 to what extent and how rapidly these could be implemented is unclear.

The primary objective of the present study was to describe the type and timing of IPAC measures deployed in hemodialysis units in Quebec during the spring of 2020. Secondary objectives were to present information about the units’ physical characteristics and to report the cumulative infection rates during the first year of the pandemic among patients attending hemodialysis units in the province.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional survey on IPAC measures implemented in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic within hemodialysis units in Quebec, Canada’s second-largest province. The survey was aimed at hemodialysis directors and nurse managers involved in pandemic preparedness efforts from March to July 2020. The WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic on Mar. 11.16 The first patient in Quebec was identified on Feb. 27, the province declared a state of emergency on Mar. 13, and Montréal declared a state of emergency on Mar. 27.17

The results are reported in accordance with the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES).18

Setting and population

We identified hemodialysis unit directors through direct communication within the Quebec Renal Network and searches on the ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux website (https://www.msss.gouv.qc.ca/). There were 55 hemodialysis units in the province, 24 main hospital-based units and 31 affiliated satellite units. Satellite centres usually provide care to a small number of patients (< 30) and are served and managed by nephrologists from larger centres.

We contacted the directors of each of the main units and invited them to be a coinvestigator in the Quebec Renal Network COVID-19 Study or to suggest someone else. Thirty-two nephrologists representing 54 hemodialysis units agreed to be coinvestigators. The directors were responsible for identifying the person most qualified to complete the questionnaire on the basis of their involvement in pandemic preparedness efforts.

On July 15, 2020, we invited nurse managers or hemodialysis unit directors from the 54 hemodialysis units to complete a 30-minute electronic questionnaire regarding specific IPAC measures deployed at their institutions since Mar. 1, 2021, to prevent the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Based on estimates from the participating investigators, there were about 4800 patients undergoing hemodialysis in the 54 units at that time.

The survey was closed, and 1 entry per unit was allowed. No incentive was offered. Up to 2 email reminders were sent to units that did not respond initially. Clarification was sought in cases of incomplete answers or major data discrepancies. Data collection was considered complete by Aug. 31, 2020. No personal information was collected about the respondents or patient characteristics.

Data sources

Survey questionnaire

A questionnaire was developed by 3 nephrologists (W.B.-S., A.-C.N.-F, R.S.S.) directly involved in outbreak prevention efforts at their institutions after a careful review of the emerging literature on COVID-19 pandemic preparedness as well as expert consensus on appropriate IPAC measures related to hemodialysis units.9,13–15 Information sought included the physical characteristics of the unit, which IPAC measures were implemented from Mar. 1 to June 30, 2020, provider perception of crowdedness and adherence to IPAC measures.

We divided IPAC measures into 4 themes: screening procedures, physical distancing measures, use of personal protective equipment and other, general measures (e.g., restriction of visitors, mask and hand hygiene for patients). We asked which measures were applied to all patients, to patients at high risk (residents of long-term care facilities and other group-living situations, returning travellers and people with a hospital stay in the previous 14 d) and to patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19. Our definition of high risk was based on consensus among the authors and participating centres. Respondents were also asked about the perceived feasibility of physical distancing and appropriate use of personal protective equipment within their units.

The questionnaire was arranged in sections, with each section being followed by a free-text section where respondents could communicate additional details. The survey was composed of 70 items, with a variable number of items on each page. It was tested for clarity and face validity iteratively by its creators and 2 research coordinators. Items considered unclear by at least 1 reviewer were revised, and the questionnaire was retested until all reviewers agreed it was adequate. The questionnaire was also piloted with the help of a nurse manager to identify any ambiguities in the questions. Reliability was not tested during survey development. The final data collection tool is presented in Appendix 1 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/4/E1232/suppl/DC1).

We collected and managed study data using REDCap electronic data-capture tools hosted at the coordinating centre. 19,20 A manual completeness check was performed for each entry. In the case of missing values not explained in the free-text box, further clarification was sought through direct communication with the respondent.

Follow-up collection of infection rate data

In April 2021, we contacted units by email to collect information about the total number of infections documented by polymerase chain reaction testing from Mar. 1, 2020, to Mar. 31, 2021, and the current number of patients undergoing in-centre hemodialysis in their units. At least 2 contact attempts were made.

We collected cumulative infection rates up to Mar. 31, 2021, in the general population in each of Quebec’s health regions from publicly available Institut national de santé publique du Québec data.12

Statistical analysis

We did not perform any sample size calculations since we aimed to include most Quebec hemodialysis units. Categoric variables were reported as numbers (percentages), and continuous variables as median (interquartile range [IQR]). Because the aim of this study was descriptive, unit characteristics, IPAC measures and cumulative infection rates are presented without any form of statistical inference. No exploratory statistical tests are presented owing to the small sample. All analyses were performed in SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp.).

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (file 20.429).

Results

The managers of 38 units (70% response rate) completed the survey. The 38 units provided care to 4485 patients with chronic kidney disease at the time of survey completion.

There was wide variation in the number of patients treated (median 86, IQR 32–138) and the number of treatment stations in the units (median 19, IQR 10–27) (Table 1). Thirteen units (34%) were operating at more than 90% capacity. Most units (35 [92%]) had at least 1 isolation room (median 2, IQR 1–4); however, in only 12 units (32%) were any of these rooms equipped with negative-pressure ventilation.

Table 1:

Characteristics of the responding Quebec hemodialysis units

| Characteristic | No. (%) of units* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All n = 38 |

Distance between stations < 2 m n = 15 |

Distance between stations ≥ 2 m n = 23 |

|

| Respondent role | |||

| Staff nephrologist | 31 (82) | 13 (87) | 18 (78) |

| Chief nurse | 7 (18) | 2 (13) | 5 (22) |

| Type of unit | |||

| University-based | 7 (18) | 3 (20) | 4 (17) |

| Community-based | 31 (82) | 12 (80) | 19 (83) |

| No. of patients treated per week, median (IQR) | 86 (32–138) | 60 (24–137) | 86 (32–212) |

| No. of dialysis treatment stations, median (IQR) | 19 (10–27) | 14 (10–26) | 20 (10–40) |

| At > 90% capacity† | 13 (34) | 4 (27) | 9 (39) |

| Patient-to-nurse ratio, median (IQR) | 3 (3–4) | 3 (3–4) | 3 (3–4) |

| Patient-to-PSW ratio, median (IQR) | 9 (7–10) | 8 (6–11) | 10 (8–10) |

| No. of isolation rooms, median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (2–4) |

| % of rooms that were isolation, median (IQR) | 12 (9–17) | 11 (3–14) | 13 (10–25) |

| No. of negative-pressure ventilation rooms, median (IQR) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–2) |

| Nursing station > 2 m from dialysis stations | 35 (92) | 13 (87) | 22 (96) |

| Treatment area perceived as crowded‡ | 12 (32) | 10 (67) | 2 (9) |

Note: IQR = interquartile range, PSW = personal support worker.

Except where noted otherwise.

Calculated as number of patients divided by 6 times the number of stations, as each dialysis station can accommodate 6 patients per week on thrice-weekly schedule.

”Crowdedness” was as perceived by the person who completed the survey.

Fifteen units (39%) reported that the average distance between hemodialysis stations was less than 2 m, and 3 units (8%) reported a distance less than 2 m between dialysis stations and nurses’ workstations. The units’ characteristics in relation to the distance between hemodialysis stations are presented in Table 1. Compared to units with 2 m or more between stations, those with less than 2 m between stations tended to provide treatment to fewer patients (median 60, IQR 24–137 v. 86, IQR 32–212]) and were less likely to be at more than 90% capacity (4 [27%] v. 9 [39%]). Respondents more frequently perceived the treatment room as crowded in units where the distance between hemodialysis stations was less than 2 m (10 [67%] v. 5 [22%]).

Two units (5%) reported that they did not have a waiting room where patients can congregate before treatment. Two-thirds (24/36 [67%]) of units with waiting rooms reported a distance of less than 2 m between chairs in the waiting room, and a greater proportion of respondents from these units than from other units perceived the waiting room as crowded (12/24 [50%] v. 2/11 [18%]). One unit (3%) reported that patients were asked to wait in their vehicle to avoid proximity inside the waiting room.

Infection prevention and control measures

Frequency of specific measures

The frequency of specific IPAC measures by May 31, 2020, is given in Table 2. Strict screening procedures, including a symptom questionnaire and measuring patients’ temperature on arrival, were implemented almost universally (37 units [97%] and 36 units [95%], respectively). The majority of units (28 [74%]) had set up a separate triage post for this purpose. Although most units (31 [82%]) encouraged patients to inform the dialysis unit in advance if they were experiencing symptoms, few units (14 [37%]) routinely called patients before their arrival. Only 3 units (8%) performed regular surveillance testing for SARS-CoV-2 by nasopharyngeal swab for all patients, but many units (24 [63%]) did so for patients at high risk. Only 7 units (18%) reported having decreased dialysis frequency for selected patients to reduce the risk of virus transmission. This was implemented more frequently in units with less than 2 m between stations than in those with 2 m or more between stations (4 [27%] v. 3 [13%]).

Table 2:

Infection prevention and control measures implemented by May 31, 2020

| Measure | No. (%) of units | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All | Distance between stations < 2 m | Distance between stations ≥ 2 m | |

| General measures | |||

| Restriction of visitors | 38 (100) | 15 (100) | 23 (100) |

| Mandatory hand hygiene for patients at entrance | 35 (92) | 15 (100) | 20 (87) |

| Signs for hand hygiene | 32 (84) | 13 (87) | 19 (83) |

| Routine disinfection of all surfaces | 32 (84) | 14 (93) | 18 (78) |

| Mask for patients at all times | 30 (79) | 13 (87) | 17 (74) |

| Screening and triage | |||

| Screening questionnaire on patient arrival | 37 (97) | 15 (100) | 22 (96) |

| Patient temperature measured on arrival | 36 (95) | 14 (93) | 22 (96) |

| All symptomatic patients tested with swabs | 36 (95) | 14 (93) | 22 (96) |

| Patients requested to call ahead if symptomatic | 31 (82) | 13 (87) | 18 (78) |

| Triage post before entry into unit | 28 (74) | 10 (67) | 18 (78) |

| Surveillance swab for asymptomatic patients at high risk* | 24 (63) | 10 (67) | 14 (61) |

| Telephone call the day before to check for symptoms | 14 (37) | 5 (33) | 9 (39) |

| Surveillance swab of all asymptomatic patients | 3 (8) | 1 (7) | 2 (9) |

| Surveillance swab of asymptomatic staff | 3 (8) | 2 (13) | 1 (4) |

| Physical distancing measures | |||

| Plexiglas or other barrier between dialysis stations | 27 (71) | 11 (73) | 16 (70) |

| Separate schedule or location for patients at high risk* | 24 (63) | 8 (53) | 16 (70) |

| Reorganization of stations to maintain physical distance | 21 (55) | 6 (40) | 15 (65) |

| Decrease in hemodialysis frequency for selected patients | 7 (18) | 4 (27) | 3 (13) |

| Personal protective equipment | |||

| Mask for staff at all times while in unit | 38 (100) | 15 (100) | 23 (100) |

| Personal protective equipment teaching sessions | 31 (82) | 12 (80) | 19 (83) |

| Full contact precautions when treating patients at high risk* | 29 (76) | 12 (80) | 17 (74) |

| Ocular protection | |||

| At all times within unit | 13 (34) | 7 (47) | 6 (26) |

| When distance from patient < 2 m | 6 (16) | 1 (7) | 5 (22) |

| Only when caring for patients | 16 (42) | 6 (40) | 10 (43) |

| No policy | 3 (8) | 1 (7) | 2 (9) |

| Measures for patients with symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 | |||

| Mask | 38 (100) | 15 (100) | 23 (100) |

| Ocular protection for staff | 38 (100) | 15 (100) | 23 (100) |

| Dialysis in isolation room | 37 (97) | 15 (100) | 22 (96) |

| Physical distancing in waiting room | 36 (95) | 14 (93) | 22 (96) |

| Creation of specific zones in unit | 34 (89) | 13 (87) | 21 (91) |

| COVID-19-specific transportation | 31 (82) | 12 (80) | 19 (83) |

| Measures for patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection | |||

| Separate dialysis schedule | 23 (60) | 11 (73) | 12 (52) |

| Reduction in personnel-to-patient ratio | 19 (50) | 8 (53) | 11 (48) |

| Dialysis in negative-pressure ventilation room | 15 (39) | 5 (33) | 10 (43) |

| Transfer to another unit for dialysis | 14 (37) | 7 (47) | 7 (30) |

Includes residents of long-term care facilities and other group-living situations, returning travellers and people with a hospital stay in the previous 14 days.

The majority of units (27 [71%]) installed Plexiglas or other types of physical barriers between dialysis stations. Although more than half of units (21 [55%]) reorganized dialysis stations to create more space between them, only 6 (40%) of the units with less than 2 m between dialysis chairs were able to do so. All units reported that patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 would be isolated in some manner, with most (37 [97%]) providing dialysis to these patients in single-patient rooms. Some smaller satellite centres (14 [37%]) reported that they transferred patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection to the main centre, which was better equipped. This was done more frequently by units with less than 2 m between dialysis stations than by those with 2 m or more between stations (7 [47%] v. 7 [30%]).

Procedure masks were worn at all times by staff in all units. In the majority of units (30 [79%]), patients were asked to wear a procedure mask continuously while receiving their treatment. About three-quarters of units (29 [76%]) implemented full droplet and contact procedures, including isolation gowns and ocular protection, when treating patients at high risk, even if asymptomatic. This was done more frequently in units located in the Greater Montréal region than elsewhere in the province (12/12 [100%] v. 17/26 [65%]). All units located in the Greater Montréal region also implemented dedicated zones or shifts for patients at high risk, compared to 12 (46%) of the other units. The use of systematic polymerase chain reaction testing for SARS-CoV-2 in patients at high risk did not differ markedly between the Greater Montréal region and the rest of the province (5 [42%] v. 9 [35%]).

All units implemented a policy to restrict access to visitors, and most (35 [92%]) implemented mandatory hand hygiene. Only 30 units (79%) implemented mandatory mask wearing for all patients during the first few months of the pandemic.

Perceived feasibility of measures

Three units (8%) reported that they were unable to implement measures for physical distancing between patients. Twenty-seven units (71%) and 8 units (21%) reported that physical distancing could be maintained all or part of the time, respectively. Most units reported adequate access to personal protective equipment at all times (33 [87%]) and adequate use of personal protective equipment by the medical staff (35 [92%]).

Timing of measures

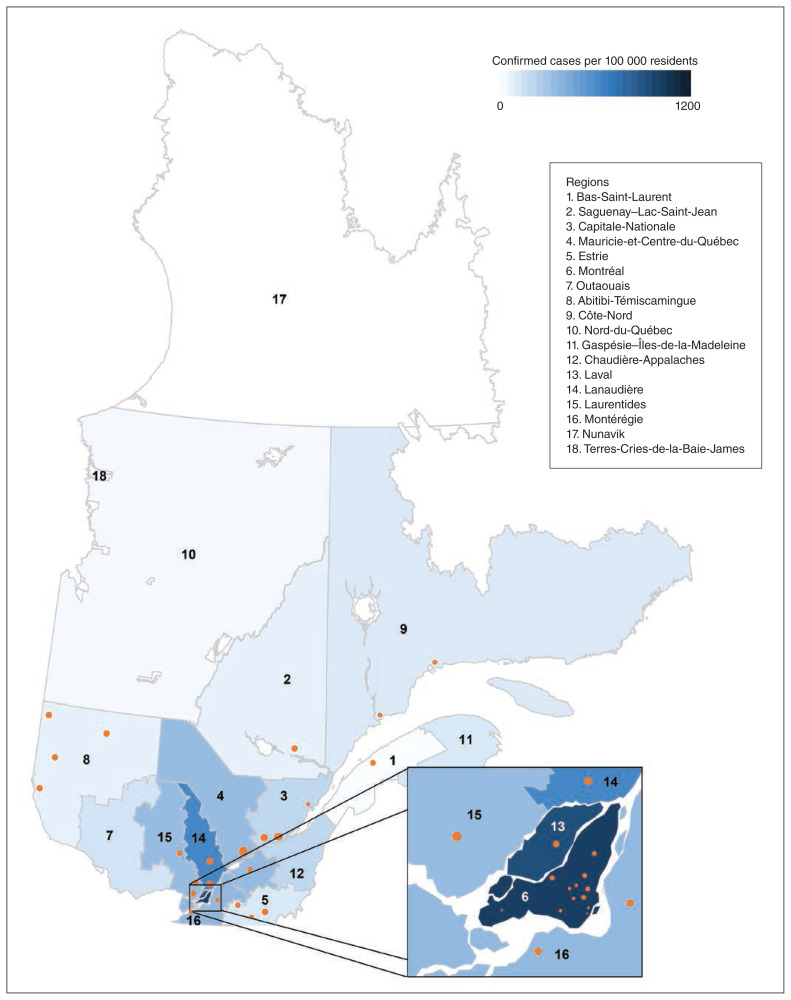

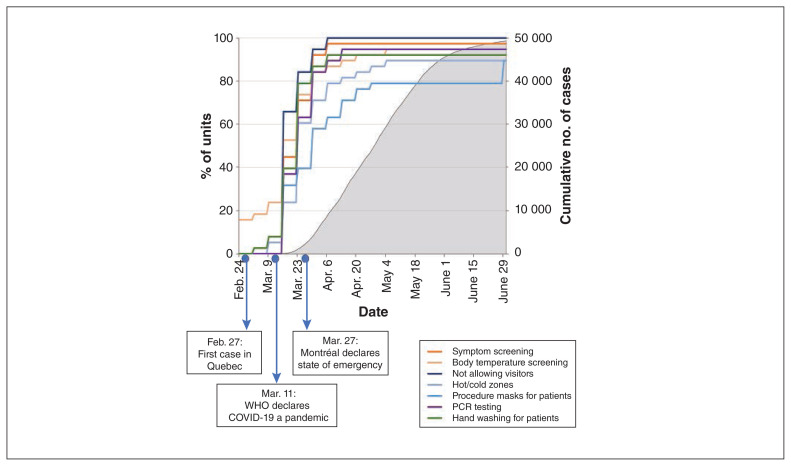

By July 15, 2020, the Greater Montréal region had the highest rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the province of Quebec (Figure 1). The most common IPAC measures (> 85% of units) were implemented in all hemodialysis units within 6 weeks of Mar. 1 (Figure 2). Fourteen units (37%) had implemented these measures by 3 weeks, when a rapid increase in COVID-19 cases in the Greater Montréal region was observed.

Figure 1:

Location of participating hemodialysis units and number of confirmed cases per capita in 9 Quebec health regions as of June 1, 2020.19

Figure 2:

Timing of implementation of the most common infection prevention and control measures in hemodialysis units in relation to important COVID-19 events in Quebec during the first 4 months of the COVID-19 pandemic (March–June 2020), and cumulative number of COVID-19 cases. Note: PCR = polymerase chain reaction, WHO = World Health Organization.

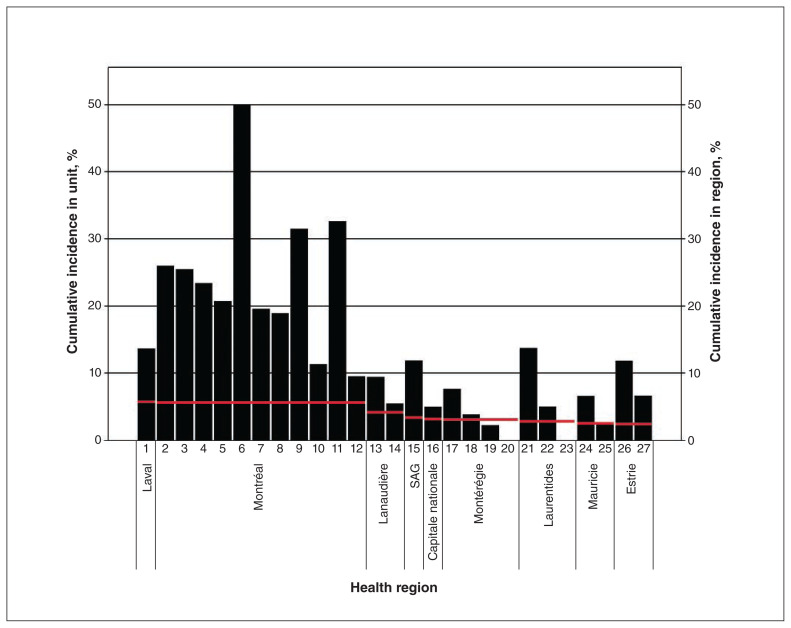

Cumulative infection rate

As of Mar. 31, 2021, follow-up data had been obtained from 27 units providing care to 4227 patients in 9 different health regions. The documented cumulative infection rate varied from 0% to 50% (median 11.3%, interquartile range 5.2%–20.2%) and was higher than the reported cumulative infection rate in the corresponding region in 23 (85%) of the 27 units (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Cumulative infection rate in 27 hemodialysis units and in the corresponding health region18 (red line) as of Mar. 31 2021. Note: SAG = Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean.

Interpretation

This report offers an overall view of IPAC strategies implemented in multiple centres in a single health care jurisdiction, the province of Quebec, early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on estimates from the participating investigators, data were obtained from units representing about 90% of patients receiving dialysis in the province. All types of dialysis units are represented, including academic and community, urban and rural, large and small. We found that local leaders in hemodialysis units were able to rapidly implement recommended IPAC measures: most measures were implemented within 3 weeks after the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 pandemic;16 the remaining measures were implemented by 6 weeks after. Despite rapid and universal adoption of IPAC measures, the cumulative infection rate was high among patients receiving care in most units 1 year after the onset of the pandemic.

In a recent study in the United Kingdom, both the dialysis area per station (in square metres) and the distance between stations were associated with a lower risk of a positive test result or hospital admission for SARS-CoV-2 infection, although this association was not observed in multivariable analysis.21 Early during the pandemic, expert groups published recommendations on how to avoid outbreaks in hemodialysis units.9,13–15 However, it was highly uncertain whether these strict screening, physical distancing and isolation measures could feasibly be implemented in crowded units at full capacity with limited space and resources, and the fear of outbreaks was high. This is compounded by uncertainties related to vaccine efficacy in this population. Recent studies on humoral response suggest that only multiple vaccine doses will succeed in conferring an adequate immunologic response in most dialysis recipients.22,23 Before April 2021, almost no dialysis recipients had been vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, and the few who had had received only 1 dose.22

We found that implementation of hand hygiene, disinfection of surfaces and mask use was universal. Dialysis units were able to implement physical distancing measures, whether the unit was perceived as crowded or not. Space restrictions and other limitations may have prompted the use of alternative solutions such as the installation of physical barriers and modification to the dialysis schedule. Similar adaptations have been reported in centres outside Quebec.24 Major changes in the model of care such as reducing dialysis frequency, a strategy reported in other countries,25 were rarely needed in Quebec. However, patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection infrequently received dialysis in negative-pressure isolation rooms, as has been recommended, 26 since only a minority of units were equipped with such rooms.

Screening and triage measures were universally deployed to identify infected patients, and most units in the Greater Montréal region, where community prevalence was high, implemented special measures for patients at high risk (e.g., those living in long-term care facilities or other group-living situations). Conversely, regular nasopharyngeal testing for SARS-CoV-2 in all asymptomatic patients at high risk was not commonly implemented during the first months of the pandemic, although it may have been more frequent after a recommendation from the Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux in July 2020.27 This surveillance testing approach may be important to curb spread during outbreaks.11

It remains unknown whether the high cumulative infection rates were related to transmission occurring in the units or in the patients’ living environments. Although the majority of infections were likely acquired in the community, outbreaks were suspected in some units (hemodialysis unit directors: personal communication, 2020). In a recent report of outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection in long-term dialysis recipients in Ontario between Mar. 12 and Aug. 20, 2020, individual risk factors for infection included residence in long-term care facilities, residence in the Greater Toronto area, Black ethnicity, Indian subcontinent ethnicity, other nonwhite ethnicities and lower income quintiles.8 A cumulative infection rate of 1.5% was reported, compared to 0.28% for the general Ontario population for the same period.28

Limitations

Data collection relied on administrative records and testimony of local leaders responsible for IPAC measures at their respective units. A substantial proportion of hemodialysis centres declined or did not respond to our invitation; however, the units for which we had data represent about 90% of the patients receiving hemodialysis in the province. Although we did not systematically collect the reasons for nonparticipation, some directors and managers reported that the additional workload involved in providing details on the deployment of each IPAC measure was substantial in the context of the important strain on human resources resulting from the pandemic.

We obtained cumulative infection rates from only a subset of participating centres, although they accounted for the majority of hemodialysis recipients in Quebec. Similarly, proceeding with local data collection was not possible since most community sites do not have on-site research staff. Consequently, because the unit of the survey was related to dialysis centres as a whole and not to individual patients, it was not possible to determine risk factors for infection. In addition, direct comparison with regional cumulative infection rates is likely to be misleading since the hemodialysis population differs in many ways from the general population, including, but not limited to, age distribution, proportion in assisted-living situations, and medical comorbidities requiring other health care encounters and increasing the risk of symptomatic COVID-19 after infection with SARS-CoV-2.

Most important, it was not possible to determine the proportion of cases related to outbreaks inside hemodialysis units. This would have required a standardized method to determine whether each case was linked to an outbreak, which was not feasible. In this regard, a high cumulative infection rate within a unit may not be representative of in-unit transmission but, rather, may be due to unrelated characteristics such as outbreaks in long-term care facilities located in the catchment area of a given unit or other sociodemographic determinants. For example, material deprivation was recently identified as an independent risk factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection among patients receiving hemodialysis in the Greater London region, UK.21 Furthermore, frequent visits to the hemodialysis unit are opportunities for screening, which would potentially increase the rate of detection compared to the general population.

Finally, we did not consult infectious disease specialists in the design of the questionnaire, and the reliability of the questionnaire was not tested formally during development.

Conclusion

Hemodialysis units throughout Quebec were able to implement IPAC measures rapidly during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite these measures, the cumulative infection rate was high among patients receiving care in most units. We suggest that IPAC measures continue until it is shown that vaccination protects hemodialysis recipients optimally against SARS-CoV-2 infection. We also suggest that future dialysis units be designed to minimize the transmission of viral respiratory illnesses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors thank all the nursing managers and dialysis unit directors who provided data for this study.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: William Beaubien-Souligny, Annie-Claire Nadeau-Fredette and Rita Suri conceived and designed the study. Marie-Noel Nguyen, Norka Rios, Marie-Line Caron and Alexander Tom acquired the data. William Beaubien-Souligny analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. William Beaubien-Souligny, Annie-Claire Nadeau-Fredette, Rita Suri and Marie-Noel Nguyen interpreted the data. All of the authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Quebec Renal Network COVID-19 Study Investigators: Dr. Mohsen Agharazii, CHU de Québec; Dr. Raman Agnihotram, McGill University, Montréal; Dr. Damien Belisle, CIUSSS duSaguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean; Dr. Daniel Blum, Jewish General Hospital, Montréal; Dr. Guillaume Bollée, CHU de Montréal; Dr. Jean-François Cailhier, CHU de Montréal; Dr. Pierre Cartier, Saint-Jérôme, Rivière-Rouge, CHSLD Lucien-G. Rolland, Saint-Jérôme; Dr. Anne-Marie Côté, Université de Sherbrooke; Dr. Serge Cournoyer, Centre intégré de santé et de services sociaux de la Montérégie-Centre, Greenfield Park; Dr. Dominique Dupuis, Hôpital Anna-Laberge, Châteauguay; Dr. Ahmed El-Geneidy, McGill University, Montréal; Dr. Marie-Chantal Fortin, CHU de Montréal; Dr. Charles H. Frenette, McGill University, Montréal; Dr. Aïcha Gafsi, Bas-Saint-Laurent; Dr. Marc Ghannoum, Verdun; Dr. Mélanie Godin, Magog, Granby; Dr. Rémi Goupil, Hôpital du Sacré-Cœur de Montréal; Dr. Jean-Philippe Lafrance, Centre de recherche de l’hôpital Maisonneuve-Rosemont, Montréal; Dr. Caroline Lamarche, Centre de recherche de l’hôpital Maisonneuve-Rosemont, Montréal; Dr. Louis-Philippe Laurin, Centre de recherche de l’hôpital Maisonneuve-Rosemont, Montréal; Dr. Fabrice Mac-Way, CHU de Québec, Portneuf, Baie-Comeau, Baie-Saint-Paul, Sept-Îles; Dr. François Madore, Université de Montréal; Dr. Alexis Payette, Centre hospitalier de Lanaudière, Saint-Charles-Borromée, Centre hospitalier Pierre-Le Gardeur, Terrebonne; Dr. Laura Pilozzi-Edmonds, St. Mary’s Hospital, Montréal; Dr. Soham Rej, Jewish General Hospital, Montréal; Dr. Louise Roy, Hôpital du Suroît, Valleyfield, CHU de Montréal; Dr. François Tashereau, Ville-Maire, La Sarre, Val-d’Or; Dr. Karine Turcotte, Victoriaville; Dr. Murray Vasilevsky, McGill University, Montréal. Dr. Thi Hai Van Vo, Hôpital de Verdun; Dr. Shiu Hoi Ying, Hôpital général du Lakeshore, Pointe-Claire. Collaborators: Dr. Maral Bessette, Hôpital de Trois-Rivières; Dr. Soraya Diallo, Hôpital Honoré-Mercier, Saint-Hyacinthe; Dr. Rami El Fishawy, Hôpital Hôtel-Dieu de Sorel; Dr. Andrea Palumbo, Hôpital de Verdun; Dr. Jerome Pinault-Lepage, Hôpital de Chicoutimi; Dr. Sandrine Rauscher, Cité-de-la-Santé, Laval; Dr. Martine Raymond, Cité-de-la-Santé, Laval; Dr. Philippe Yale, Hôpital du Haut-Richelieu, Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu.

Funding: This study was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research COVID-19 Rapid Research Funding Opportunity grant (447760). Rita Suri and Annie-Claire Nadeau-Fredette are supported by Fonds de recherche du Quebec – Santé Clinician-Researcher awards. William Beaubien-Souligny is supported by a KRESCENT New Investigator Award.

Data sharing: The data that support the findings of this study are available from one of the corresponding authors, William Beaubien-Souligny, on reasonable request.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/4/E1232/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Annual statistics on organ replacement in Canada: dialysis, transplantation and donation, 2008 to 2017. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell S, Campbell J, McDonald J, et al. Scottish Renal Registry. COVID-19 in patients undergoing chronic kidney replacement therapy and kidney transplant recipients in Scotland: findings and experience from the Scottish renal registry. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21:419. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-02061-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Meester J, De Bacquer D, Naesens M, et al. NBVN Kidney Registry Group. Incidence, characteristics, and outcome of COVID-19 in adults on kidney replacement therapy: a regionwide registry study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32:385–96. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020060875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jager KJ, Kramer A, Chesnaye NC, et al. Results from the ERA-EDTA Registry indicate a high mortality due to COVID-19 in dialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients across Europe. Kidney Int. 2020;98:1540–8. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keller N, Chantrel F, Krummel T, et al. Impact of first-wave COronaVIrus disease 2019 infection in patients on haemoDIALysis in Alsace: the observational COVIDIAL study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35:1338–411. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tortonese S, Scriabine I, Anjou L, et al. AP-HP/Universities/Inserm COVID-19 Research Collaboration. COVID-19 in patients on maintenance dialysis in the Paris region. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:1535–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss S, Bhat P, Del Pilar Fernandez M, et al. COVID-19 infection in ESKD: findings from a prospective disease surveillance program at dialysis facilities in New York City and Long Island. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:2517–21. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020070932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taji L, Thomas D, Oliver MJ, et al. COVID-19 in patients undergoing long-term dialysis in Ontario. CMAJ. 2021;193:E278–84. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.202601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kliger AS, Silberzweig J. Mitigating risk of COVID-19 in dialysis facilities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15:707–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03340320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazzoleni L, Ghafari C, Mestrez F, et al. COVID-19 outbreak in a hemodialysis center: a retrospective monocentric case series. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2020;7:2054358120944298. doi: 10.1177/2054358120944298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yau K, Muller MP, Lin M, et al. COVID-19 outbreak in an urban hemodialysis unit. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76:690–5e1. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Données COVID-19 par région sociosanitaire. Québec: Institut national de santé publique du Québec; [accessed 2020 Dec. 17]. Available: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/donnees/par-region. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suri RS, Antonsen JE, Banks CA, et al. Management of outpatient hemodialysis during the COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations from the Canadian Society of Nephrology COVID-19 Rapid Response Team. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2020;7:2054358120938564. doi: 10.1177/2054358120938564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moura-Neto JA, Abreu AP, Delfino VDA, et al. Good practice recommendations from the Brazilian Society of Nephrology to dialysis units concerning the pandemic of the new coronavirus (COVID-19) J Bras Nefrol. 2020;42(Suppl 1):15–7. doi: 10.1590/2175-8239-JBN-2020-S105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roper T, Kumar N, Lewis-Morris T, et al. Delivering dialysis during the COVID-19 outbreak: strategies and outcomes. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:1090–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. Geneva: World Health Organization; Mar 11, 2020. 2020. [accessed 2021 Nov. 24]. Available https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le gouvernement du Québec déclare l’état d’urgence sanitaire, interdit les visites dans les centres hospitaliers et les CHSLD et prend des mesures spéciales pour offrir des services de santé à distance. Québec: Cabinet du premier ministre; mars 14, 2020. [accessed 2021 Nov. 24]. Available: https://www.quebec.ca/nouvelles/actualites/details/le-gouvernement-du-quebec-declare-l-etat-d-urgence-sanitaire-interdit-les-visites-dans-les-centres-hospitaliers-et-les-chsld-et-prend-des-mesures-speciales-pour-offrir-des-services-de-sante-a-distance. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-Dr.iven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. REDCap Consortium. The REDCap Consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caplin B, Ashby D, McCafferty K, et al. Risk of COVID-19 disease, dialysis unit attributes, and infection control strategy among London in-center hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16:1237–46. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03180321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goupil R, Benlarbi M, Beaubien-Souligny W, et al. Réseau Rénal Québécois (Quebec Renal Network) COVID-19 Study Investigators. Short-term antibody response after 1 dose of BNT162b2 vaccine in patients receiving hemodialysis. CMAJ. 2021;193:E793–800. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.210673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grupper A, Sharon N, Finn T, et al. Humoral response to the Pfizer BNT162b2 vaccine in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16:1037–42. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03500321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ibernon M, Bueno I, RoDríguez-Farré N, et al. The impact of COVID-19 in hemodialysis patients: experience in a hospital dialysis unit. Hemodial Int. 2021;25:205–13. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lodge MDS, Abeygunaratne T, Alderson H, et al. Safely reducing haemodialysis frequency during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21:532. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-02172-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basile C, Combe C, Pizzarelli F, et al. Recommendations for the prevention, mitigation and containment of the emerging SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic in haemodialysis centres. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35:737–41. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Directive sur l’utilisation des tests selon le palier d’alerte. Directive ministérielle DGSP-001. Québec: Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux; [accessed 2021 Nov. 24]. updated 2020 Aug. 10. Available: https://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/document-002853/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.COVID-19 Epidemiologic summaries from Public Health Ontario. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Health; [accessed 2021 May 10]. Available: https://covid-19.ontario.ca/covid-19-epidemiologic-summaries-public-health-ontario. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.