Abstract

This case-control study evaluates the estimated vaccine effectiveness against infection changes over time to help inform public health policy and clinical practices.

Introduction

As of August 17, 2021, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 168.7 million people in the US, more than half of the US population, had received full doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.1 This study evaluates whether estimated vaccine effectiveness against infection changes over time to help inform public health policy and clinical practices.

Methods

This case-control study was approved by the Sterling institutional review board. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. Informed consent was waived by the institutional review board because of the use of limited retrospective data that was already collected.

Using a national SARS-CoV-2 test database, we evaluated the incidence of unique patients with symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections confirmed by positive polymerase chain reaction tests in US retail locations (May 1 to August 7, 2021). COVID-19–related symptoms per CDC definition, vaccination status, time, and the number of doses were self-reported in the screening questionnaire before nasal swab collections. We used the following vaccines for analysis: BNT162b2 (Pfizer), mRNA-1273 (Moderna), and JNJ-78436735 (Johnson & Johnson). We used a test-negative case-control design2,3 to estimate the effectiveness of vaccination against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection over time from the last vaccination, adjusting for age, region, and calendar month of test given the prominence of the Delta variant in July to August in the US (eMethods in the Supplement). All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Two-sided tests with a P value < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Our analysis included 1 237 097 unique symptomatic persons age 18 years or older who were tested at 4094 locations across the US (732 850 [59.2%] women; 503 303 [40.7%] men; 944 [0.1%] unknown). The median (IQR) age was 37 (28-51) years. The study included 88 178 (7.1%) Asian individuals; 168 639 (13.6%) Black or African American individuals; 221 521 (17.9%) Hispanic individuals; 661 459 (53.5%) White individuals; and 97 300 (7.9%) individuals identifying as Alaska Native, American Indian, Pacific Islander, unspecified, or unknown. A total of 645 604 persons (52.2%) were unvaccinated. Of the 591 493 vaccinated persons (47.8%), 335 341 (27.1%) received BNT162b2, 207 250 (16.8%) received mRNA-1273, and 48 902 (4.0%) received JNJ-78436735.

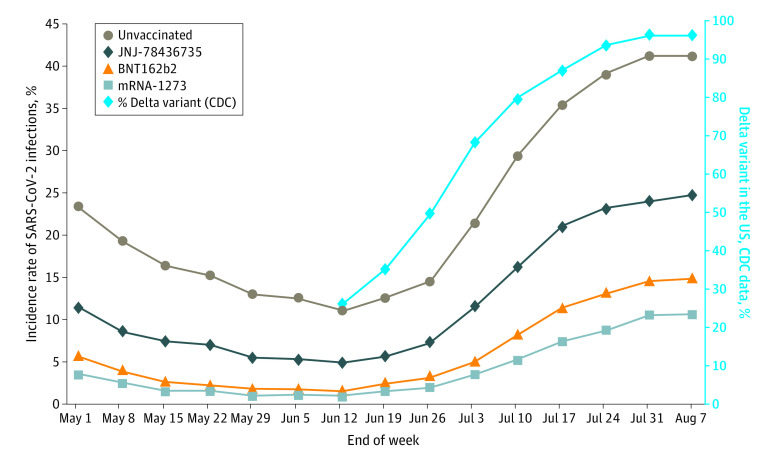

Vaccination status was associated with lower SARS-CoV-2 infection rates (Figure 1). Persons who received mRNA vaccines (BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273) had the lowest incidence rate at every point of the observational time, and unvaccinated persons in this cohort had the highest rate. Unvaccinated persons had 412%, 287%, and 159% more infections that people who received mRNA-1273, BNT162b2, or JNJ-78436735 vaccines, respectively. The observed incidence rate during the study period was 24.8% (unvaccinated), 15.6% (JNJ-78436735), 8.6% (BNT162b2), and 6.0% (mRNA-1273). The magnitude of SARS-CoV-2 risk for unvaccinated persons increased even more in July and August, parallel with the increasing prevalence of the Delta variant in the US. When restricted to fully vaccinated persons, the trend was nearly identical.

Figure 1. Weekly Incidence Rate of SARS-CoV-2 Infections (Unique Persons) by Vaccination Status.

Persons had at least 1 self-reported symptom per US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definition (fever, shortness of breath, cough, chills, nausea or vomiting, muscle pain, sore throat, loss of taste or smell, fatigue, headache, congestion, diarrhea). Vaccinated persons included all receiving any number of doses of any of the 3 vaccines (for mRNA vaccines, 99.9% of persons reported receiving 2 doses). Data on Delta virus proportions were obtained from the CDC website.

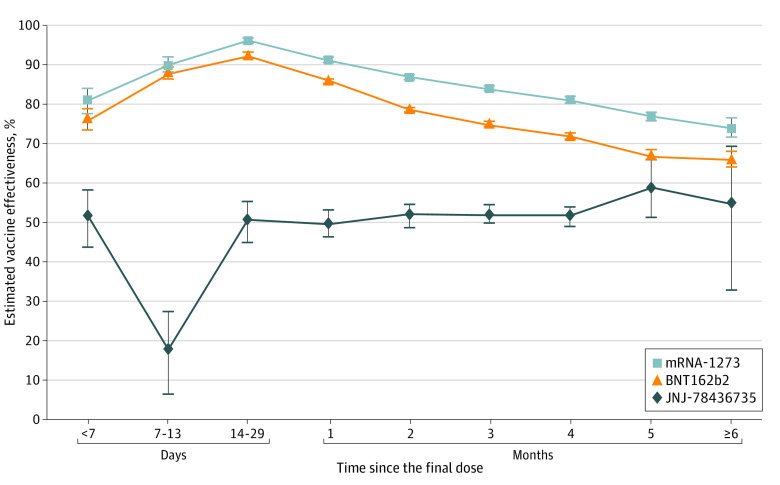

The adjusted estimated vaccine effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 infections for persons vaccinated with 2-dose mRNA vaccines peaked after 2 weeks (96.3% [95% CI, 95.6%-96.9%] for mRNA-1273 and 92.4% [95% CI, 91.7%-93.1%] for BNT162b2), then gradually fell to 86.8% (95% CI, 86.2%-87.4%) and 78.6% (95% CI, 78.0%-79.2%) at 2 to 3 months and 74.2% (95% CI, 71.6%-76.6%) and 66% (95% CI, 64.2%-68.0%), respectively, after 6 months in multivariable analyses (Figure 2). The adjusted estimated vaccine effectiveness for 1 dose of JNJ-78436735 remained greater than 50% after 2 weeks.

Figure 2. Multivariable Adjusted Estimated Vaccine Effectiveness Against SARS-CoV-2 Infection and 95% CIs.

Models were adjusted for age, geographic region, and calendar month of test. Estimated vaccine effectiveness over time since the final dose was calculated as (1 − multivariable adjusted odds ratio for infection) × 100. The final dose was defined as the only dose for JNJ-78436735 and the second dose for mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2 before August 7, 2021.

Discussion

Our analyses provide real-world evidence on the substantial risk of symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections in unvaccinated persons, who were up to 4 times more likely to be infected with SARS-CoV-2 between May and August 2021 than vaccinated individuals. Our findings are based on data from more than 1.2 million individuals in the CVS Health database, which is, to our knowledge, the largest national SARS-CoV-2 test data set in the US. Our findings are consistent with a study in which mRNA-1273–elicited antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants persisted but at a reduced level 6 months after the second dose,4 and with a case-control study reporting a 0.22 relative risk for SARS-CoV-2 infections in individuals vaccinated with 2-dose mRNA vaccines before the emergence of the Delta variant.5 This study was limited because vaccination statuses were self-reported, introducing recall errors and missing data. The issuance of vaccination cards likely minimized such recall errors; only 3.4% of vaccinated persons were excluded from vaccine effectiveness estimation because of missing vaccination dates. The viral vector-based vaccine became available later and accounted for just 4% of the study population; thus, more data are needed to estimate its vaccine effectiveness accurately. We acknowledge that all observational studies have limitations and may be subject to unmeasured confounding bias.2,3

It is also important to emphasize that our data were collected at retail settings and therefore likely represent less severe infections than those identified in inpatients. Literature to date consistently reports much higher vaccine effectiveness (more than 90%) against severe illness, hospitalization, and death.6 Although our data indicate that vaccine effectiveness gradually wanes over time, the 2-dose mRNA vaccines remained estimated 74% (mRNA-1273) and 66% (BNT162b2) effective against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections 6 months or longer after 2 doses during a period in which the Delta variant became the dominant strain.

eMethods.

References

- 1.COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations_vacc-people-onedose-percent-pop12

- 2.Young-Xu Y, Korves C, Roberts J, et al. Coverage and estimated effectiveness of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines among US veterans. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2128391. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dean NE, Hogan JW, Schnitzer ME. Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness and the test-negative design. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(15):1431-1433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2113151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pegu A, O’Connell SE, Schmidt SD, et al. ; mRNA-1273 Study Group . Durability of mRNA-1273 vaccine-induced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants. Science. 2021;373(6561):1372-1377. doi: 10.1126/science.abj4176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertollini R, Chemaitelly H, Yassine HM, Al-Thani MH, Al-Khal A, Abu-Raddad LJ. Associations of vaccination and of prior infection with positive PCR test results for SARS-CoV-2 in airline passengers arriving in Qatar. JAMA. 2021;326(2):185-188. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.9970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tenforde MW, Olson SM, Self WH, et al. Effectiveness of Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines against COVID-19 among hospitalized adults aged ≥65 Years—United States, January–March 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:674-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.