Abstract

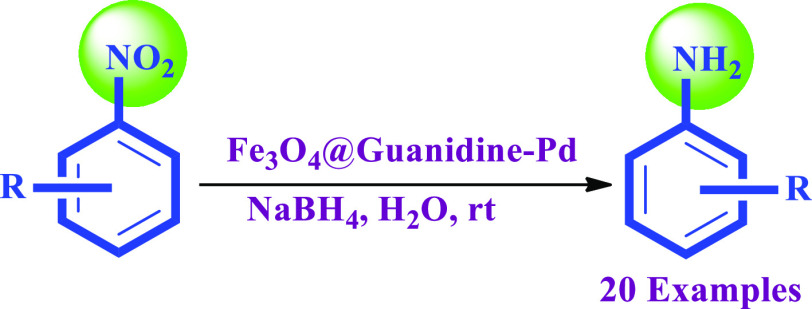

This paper presents guanidine-functionalized Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticle-supported palladium (II) (Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd) as an effective catalyst for Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling of aryl halides using phenylboronic acids and also for selective reduction of nitroarenes to their corresponding amines. Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd synthesized is well characterized using FT-IR spectroscopy, XRD, SEM, TEM, EDX, thermal gravimetric analysis, XPS, inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy, and vibrating sample magnetometry analysis. The prepared Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd showed effective catalytic performance in the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reactions by converting aryl halides to their corresponding biaryl derivatives in an aqueous environment in a shorter reaction time and with a meagerly small amount of catalyst (0.22 mol %). Also, the prepared Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd effectively reduced nitroarenes to their corresponding amino derivatives in aqueous media at room temperature with a high turnover number and turnover frequency with the least amount of catalyst (0.13 mol %). The most prominent feature of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd as a catalyst is the ease of separation of the catalyst from the reaction mixture after the reaction with the help of an external magnet with good recovery yield and also reuse of the recovered catalyst for a few cycles without significant loss in its catalytic activity.

1. Introduction

Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions have been developed as an essential process for achieving the composition of carbon–carbon (C–C) bonds in synthetic organic chemistry.1,2 These C–C bond-forming reactions play a vital role in synthesizing pharmaceuticals, polymers, advanced materials, and naturally derived products.3,4 Because of the intensive use of Pd-based catalysts for the development of C–C bonds, they are continually attracting attention of the researchers and for industrial applications. In addition, nitroarenes are discovered as one of the major classes of organic pollutants released by various industries, which are hazardous to aqueous systems and poisonous to the environment particularly for human beings, animals, and plants.5 These nitroarenes are low-cost and abundant building blocks for the production of several synthetic compounds, which can be effortlessly reduced to amines in reductive environments with the help of a catalyst.6 Researchers are now focusing on the development of highly efficient, recoverable, and reusable catalysts, which can be used for environmentally friendly industrial purposes.7,8 With regard to this, there were various pieces of evidence in the literature regarding the synthesis of various homogeneous and heterogeneous metal-based catalysts and the study of their catalytic activity toward the Suzuki coupling reaction and reduction of nitroarenes.9−12 Even though homogeneous catalysts have excellent catalytic performance toward organic reactions, they are not favored due to their less recovery and recyclability performance.9,12 Due to which, heterogeneous catalysts with palladium supported as a substrate are majorly employed in the organic reactions, as they could be isolated from the reaction medium using conventional separation procedures such as filtration or centrifugation.13 However, these separation methods are also not effective as they are time-consuming, and as the catalyst particle size is minimal, catalyst loss is inevitable, which strongly affects its recoverability and recyclability. To solve these difficulties with filtration/centrifugation techniques, the design and development of magnetic substrate-supported catalysts have gained importance as they ease the work-up procedure during separation and reduce the loss of catalysts to a remarkable extent. This makes the catalyst more economical and enables industrial commercialization, thereby making it advantageous.14

The utilization of appropriate supported ligands and the immobilization of ligands on heterogenized metals give a steady and sustainable catalyst framework, resulting in minimal leaching and metal aggregation issues.15,16 Of such ligands, nitrogen-containing ligands and their derivatives have been considerably used as potent ligands, such as Schiff bases,17−19 N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHC),20−22 NNN-pincer ligands,23 pyrazoles,24 pyridines,25 DABCO,26 N-containing dendrimers,27 and thiols.28 Guanidine is a significant class of generally occurring compounds frequently used in natural science and is extensively exploited as catalysts.29 In particular, guanidine is a suitable N-donor ligand owing to its capacity to shift the positive charge to a guanidine moiety, a behavior that leads to strongly basic and highly nucleophilic compounds with an increased ability to coordinate with metal ions. As a result, guanidine-type ligands have been specifically used to prepare highly active homogeneous/heterogeneous catalysts with transition metals that can catalyze various organic reactions.30−32 Although guanidine-based catalysts show remarkable catalytic activity, they lack in recovery and reusability.32,33 To ease the recovery of the catalyst, deprived of any considerable loss, and increase the reusability of the catalyst, we have tethered the guanidine ligand to a magnetic substrate and immobilized Pd on magnetic substrate-supported guanidine.34,35

Considering the above facts and research interest in developing novel catalyst systems and methods for various reactions and applications,36−38 we have prepared novel Pd-based guanidine-conjugated iron oxide nanoparticles as a highly effective magnetically separable catalyst. Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd catalytic activity was subsequently investigated toward Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling and selective reduction of nitroarenes in an aqueous medium.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd

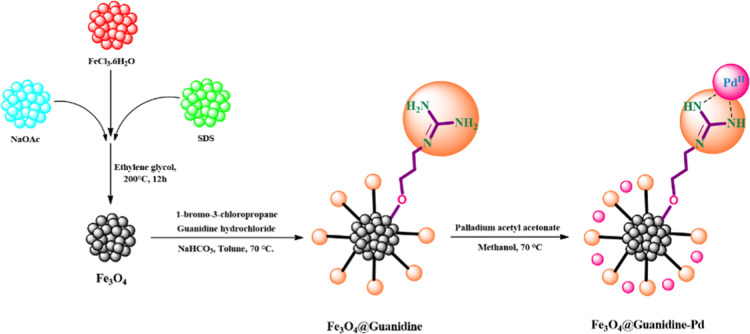

Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd as a novel heterogeneous catalyst was prepared based on the pathway shown in Scheme 1. Core–shell Fe3O4 nanoparticles were conjugated to 1-bromo-3-chloropropane by nucleophilic substitution with a guanidine ligand to prepare the catalyst. Fe3O4@Guanidine was combined with a solution of palladium acetylacetonate with reflux for 6 h to incorporate palladium ions.

Scheme 1. Schematic Diagram Showing the Synthesis of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd.

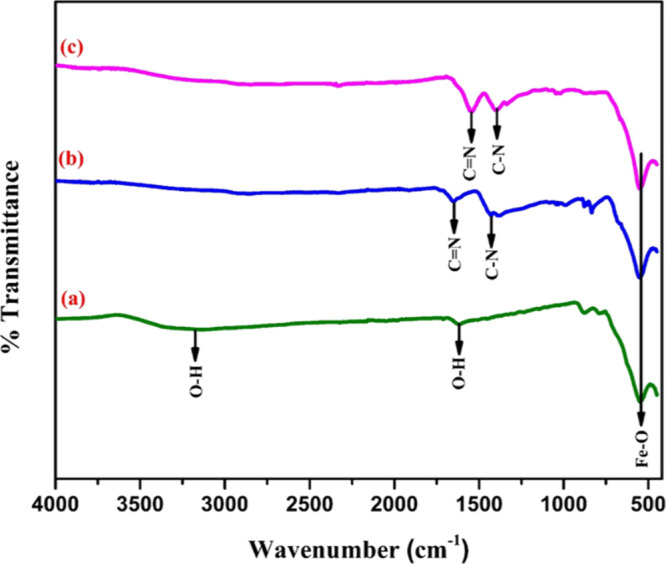

To investigate the structure along with the elemental composition of the prepared Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd catalyst, FTIR spectroscopy, XRD measurements, EDX, and XPS analysis were carried out. The size distribution with the surface morphology of the nanoparticles was examined using SEM and TEM. Furthermore, to explore the magnetic property, thermal stability, and metal ion concentration of the synthesized samples, vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM) thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA), and inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) were used. As observed in Figure 1, the bands around 550 cm–1 (in all the spectra displayed) were because of the Fe–O bond stretching vibrations and confirmed the presence of Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles.39 The peaks near 1652, 1427, and 830 cm–1 (Figure 1b) were related to C=N, C–N, and −NH2 bonds that confirmed the existence of guanidine molecules on top of the magnetic nanoparticles.40 It is intriguing to observe, particularly when metalized using palladium ions, the shift of the absorption peak at 1652 cm–1 corresponding to (C=N) bond in Figure 1b to 1545 cm–1 as in Figure 1c, proving the coordination of the metal with a ligand molecule.41

Figure 1.

FTIR spectra of (a) Fe3O4 nanoparticles showing an absorption peak at 550 cm–1corresponding to the Fe–O bond, (b) Fe3O4@Guanidine showing absorption peaks at 1652, 1427, and 830 cm–1 corresponding to (C=N), (C–N), and (−NH2) bonds, and (c) Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd showing an absorption peak at 1545 cm–1 (shifted peak) corresponding to (C=N) confirms the coordination of the metal with a ligand molecule.

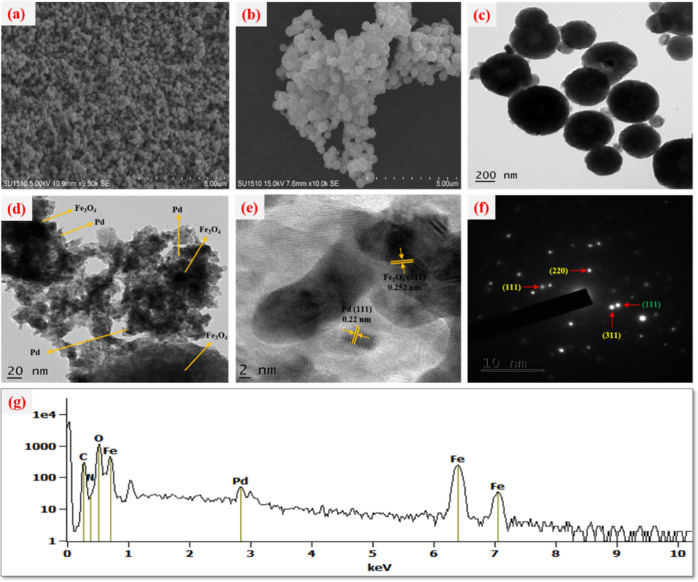

The prepared catalyst surface morphology, uniformity, and particle size were determined by recording the SEM and TEM images, as shown in Figure 2. It can be noticed in Figure 2a,b that the catalyst particles have a spherical morphology with the particle size determined on the nanoscale. Nevertheless, there was some aggregation of Fe3O4 nanoparticles due to the magnetostatic interaction of the particles. The TEM images of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd in Figure 2c,d confirmed the core–shell appearance of Fe3O4 nanoparticles, which were successfully immobilized on the surface of guanidine. As seen in Figure 2c,d, Pd nanoparticles were relatively homogeneously dispersed on the magnetic guanidine surface and their average particle size was determined to be in the range of 40–60 nm. A clear lattice fringe spacing of about 0.25 nm is attributed to the (311) plane of the face-centered cubic (fcc) inverse spinel structured magnetite along with the lattice fringes with a spacing of about 0.22 nm, which are from the (111) fcc-structured Pd nanoparticles as observed in (Figure 2e). The SAED pattern of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd showed a regular diffraction sequence, which corresponds to the (hkl) values of diffraction of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd (Figure 2f), and d-spacings calculated from SAED are similar to the obtained dhkl values from the XRD analysis.

Figure 2.

(a) FE-SEM picture of Fe3O4 confirms the spherical structure of Fe3O4, (b) SEM picture of Fe3O4@guanidine-Pd confirms the spherical form of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd, (c–e) TEM images of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd confirm the layer on core–shell structure of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles and the immobilized guanidine layer on the surface, (f) SAED pattern of the Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd, and (g) EDX spectra of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd confirming the presence of C, O, Fe, Cu, and N.

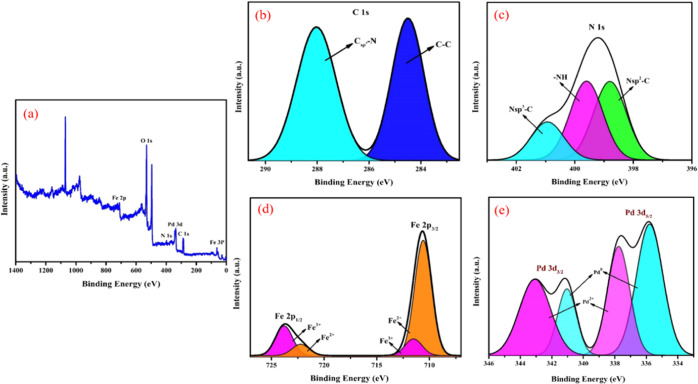

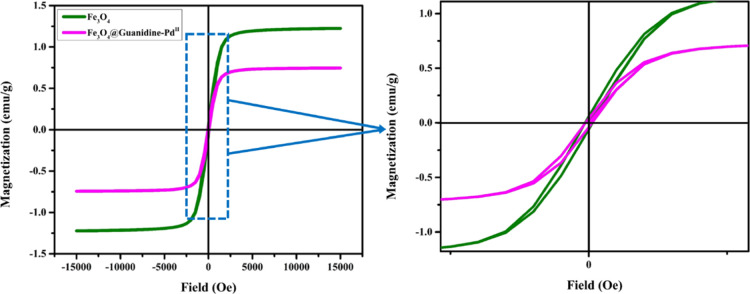

The spectrum observed from EDX analysis proved the existence of C, N, Fe, O, and Pd elements in the Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd catalyst. In addition, the occurrence of nitrogen in elemental analysis shows that the guanidine ligand is successfully conjugated on the surface of Fe3O4. Thus, it can be confirmed that the new catalyst is completely synthesized. Moreover, Figure 3a shows the overall XPS patterns of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd, which contain the peaks relating to the C, N, Fe, and Pd elements. Figure 3b indicates the XPS pattern of C1s, which could be deconvoluted into two significant peaks at 284.5 and 288.05 eV that correspond to C–C and Csp3–N bonds. Figure 3c shows the XPS spectra of N 1s; it revealed that the prominent peak at 399.9 eV is associated with −NH and additional two more peaks at 401 and 399 eV correspond to the N–sp3C and N–sp2C bonds.42Figure 3d reveals the XPS Fe 2p spectra, the deconvolution of the Fe (2p1/2) (2p3/2) spectrum showed major peaks at 723.9, 711.87 eV (Fe3+) and 722.16, 710.3 eV (Fe2+), these revealed that the position of the Fe (2p1/2) (2p3/2) peaks corresponds to Fe3O4.43 It can be observed in Figure 3e that the bands around 335.71(3d5/2) and 341(3d3/2) correspond to Pd in the 0 oxidation state. The bands near 337.7 (3d5/2) and 343 (3d3/2) signify a minute fragment of Pd in the II oxidation state. The Pd (0) ratio is higher than the Pd (II) ratio, implying that Pd species in the catalyst would primarily remain in the zero-valent system. This result also confirmed the presence of Pd2+ and Pd0.44 Also, ICP-OES examinations were utilized to verify the exact concentration of Pd. The ICP-OES analysis indicates that 0.11 mmoles of Pd was held at 1g of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd. The magnetic features of Fe3O4 and Fe3O4-Guanidine-Pd were analyzed using VSM at normal temperature, as shown in Figure 4. The saturation magnetization (Ms) value of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd (0.74431 emu) is less than that of Fe3O4 (1.2238 emu) nanoparticles, which is due to the organic layer and copper complex above the Fe3O4 nanoparticles. These magnetization data displayed a weak hysteresis loop at normal temperature, indicating the existence of the ferromagnetic behavior in all Fe3O4 core and Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd samples, respectively. The resulting magnetic nanoparticles have a typical ferromagnetic behavior, which are attracted to small magnets.

Figure 3.

(a) Overall XPS patterns of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd confirming the presence of O, C, N, Fe, and Pd elements, (b) C 1s, showing peaks at 284.5 and 288.05 eV corresponding to C–C and Csp3–N bonds, (c) N 1s, showing the peaks at 399.9, 399, and 401 eV corresponding to the −NH, N–sp2C, and N–sp3C bonds, (d) Fe 2p, showing major peaks at 723.9, 711.87 eV (Fe3+), and 722.16, 710.3 eV (Fe2+) corresponding to Fe3O4, and (e) Pd 3d, showing the peaks at 335.7 (3d5/2) and 341 (3d3/2) corresponding to Pd in the zero oxidation state.

Figure 4.

Fe3O4 and Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd magnetization curves showing the weak hysteresis loop indicating the prepared material’s ferromagnetic behavior.

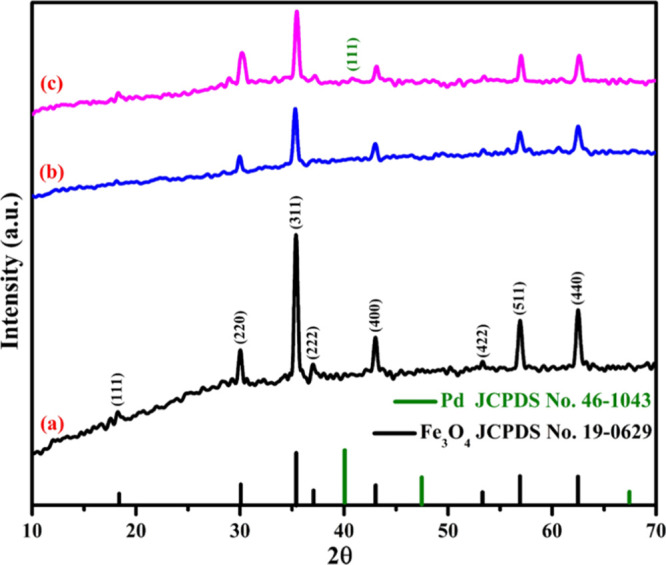

The composition and crystallinity of the synthesized Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd catalyst were investigated with XRD measurements, as shown in Figure 5. In the spectra, 5a–c, the crystalline peaks at 18.3, 30.1, 35.4, 43.1, 53.4, 56.9, and 62.5° represent the structure of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles (fcc inverse spinel of magnetite) and were confirmed using their Miller indices (JCPDS no. 19-0629).45 From the XRD results, the characteristic peak at 40.02° corresponds to the (111) plane of the fcc structure of Pd (JCPDS no. 46-1043).46 The XRD pattern of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd showed that the magnetite crystal appearance of the Fe3O4 core was retained even after conjugation. Therefore, these results confirmed that the guanidine ligand is well bound to the surface of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles.47

Figure 5.

XRD analysis of (a) Fe3O4, (b) Fe3O4@Guanidine, and (c) Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd showing the peaks at 18.3° (111), 30.1° (220), 35.4° (311), 43.1° (400), 53.4° (422), 56.9° (511), and 62.5° (440) corresponding to the fcc inverse spinel structure of Fe3O4.

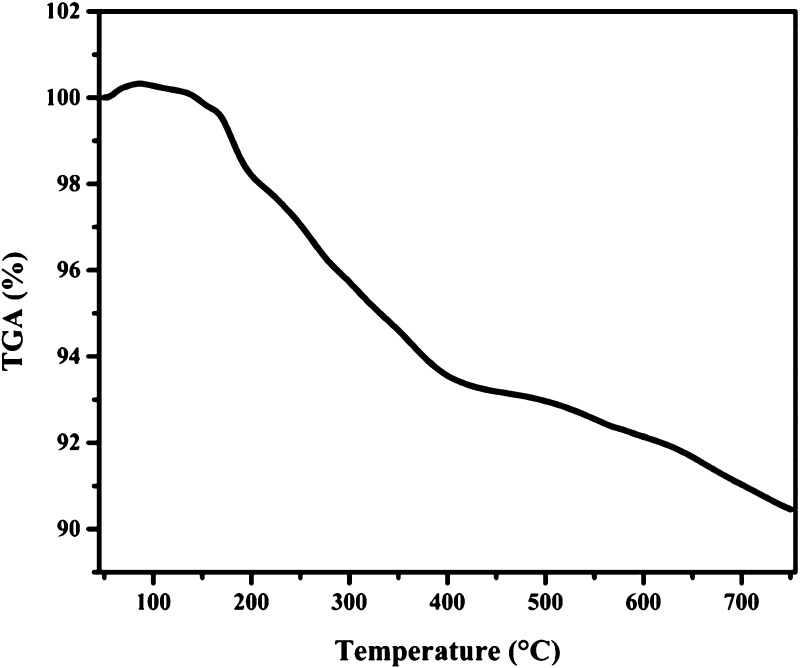

For further examination of the thermal stability of the Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd catalyst, the thermogravimetric TGA analysis was carried out in the thermal range of 50–750 °C (Figure 6). This process also delivers information relating to the mixture of Fe3O4 nanoparticles with the guanidine molecules via examining the decomposition procedure. TGA analysis of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd showed a weight loss of 1.8% at 200 °C because of the decomposition of water and ethanol from the catalyst surface. The organic functional group has been found to decompose above 200 °C.48 A weight loss of 7.88% at 200–750 °C is observed due to the breakdown of organic ligands conjugated on the magnetic nanoparticle surface. Hence, this analysis revealed that the guanidine molecule was successfully conjugated with magnetic nanoparticles.49

Figure 6.

TGA diagram of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd showing a weight loss of around 7.88% at 200 to 750 °C, indicating the decomposition of organic ligands conjugated on the surface of magnetic nanoparticles.

2.2. Catalytic Studies

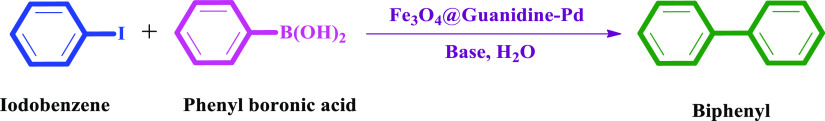

2.2.1. Suzuki–Miyaura Cross-Coupling Reaction

After characterization of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd, its catalytic feature was examined for the preparation of biphenyl byproducts using the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction. The reaction parameter was further enhanced during the initial evaluation by changing the solvent, base, and catalyst concentrations with a model process between phenylboronic acid and iodobenzene, as indicated in Table 1. However, a blank experiment performed without catalyst in an aqueous medium at 70 °C temperature using a 1:1.5 mole ratio resulted in only a negligible quantity of the product despite a prolonged time (Table 1, entry 1). Furthermore, when the catalyst is separated from the reaction mixture in the midst of the process, that is, at 50% conversion, no transformations were noticed after the removal, which indicates their significant role in the conversion. From this point of view, the vital role of the Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd catalyst in the process of such a Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction is highlighted. As displayed in Table 1 (entry 4), the use of 0.22 mol % of the Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd catalyst is adequate to carry out the reaction in 20 min with the appearance of 1:1.5 mmol iodobenzene/K2CO3 in water medium at 70 °C. The next step is to investigate the effects of the solvents, including H2O, EtOH, EtOH–H2O (1:1), DMF, DMF-H2O (1:1), and toluene, which were scrutinized under the same conditions in the presence of 0.22 mol % of the catalyst. These procedures led us to conclude that environmentally friendly aqueous media was superior to all the examined solvents. To evaluate the base effect in the reaction rate, a series of accessible inorganic bases is studied, such as K2CO3 and NaHCO3. As a result, K2CO3 is found to be the most suitable base, as shown in Table 1, and this could be because of the high solubility of an inorganic base in aqueous media. Thus, K2CO3 was validated adequately as the most suitable alternative in both economic and reaction development viewpoints (Table 1). During the optimization analysis, the immediate output of utilizing a different molar ratio of K2CO3 was also investigated. As observed, a decrease in the reaction rate was noticed by reducing K2CO3 to 1.2 mmol. When the amount of K2CO3 was increased to 1.8 mmol, no improvement was observed (Table 1).

Table 1. Optimization Table for the Suzuki–Miyaura Cross-Coupling Reaction.

| entrya | catalyst (mol %) | iodobenzene/base (mmol) | base | solvent | temp. (°C) | time (min) | isolated yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | without catalyst | 1:1.5 | K2CO3 | H2O | 100 | 1440 | trace |

| 2 | 0.13 | 1:1.5 | K2CO3 | H2O | 70 | 90 | 82 |

| 3 | 0.17 | 1:1.5 | K2CO3 | H2O | 70 | 50 | 92 |

| 4 | 0.22 | 1:1.5 | K2CO3 | H2O | 70 | 20 | 96 |

| 5 | 0.26 | 1:1.5 | K2CO3 | H2O | 70 | 30 | 96 |

| 6 | 0.22 | 1:1.2 | K2CO3 | H2O | 70 | 120 | 79 |

| 7 | 0.22 | 1:1.8 | K2CO3 | H2O | 70 | 60 | 96 |

| 8 | 0.22 | 1:1.5 | K2CO3 | EtOH | reflux | 60 | 80 |

| 9 | 0.22 | 1:1.5 | K2CO3 | EtOH/H2O (1:1) | reflux | 50 | 86 |

| 10 | 0.22 | 1:1.5 | K2CO3 | DMF | 100 | 360 | 82 |

| 11 | 0.22 | 1:1.5 | K2CO3 | DMF/H2O (1:1) | 100 | 120 | 89 |

| 12 | 0.22 | 1:1.5 | K2CO3 | toluene | reflux | 720 | 42 |

| 13 | 0.22 | 1:1.5 | NaHCO3 | H2O | 70 | 120 | 76 |

| 14 | 0.22 | 1:1.5 | K2CO3 | H2O | 50 | 120 | 72 |

| 15 | 0.22 | 1:1.5 | K2CO3 | H2O | 100 | 20 | 90 |

Reaction conditions: iodobenzene(1 mmol), phenylboronic acid (1.2 mmol), base (1.5 mmol), solvent (2 mL), and the Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd (0.22 mol %) catalyst was agitated at 70 °C for 20 min.

The effect of temperature on the reaction effectiveness was also confirmed. Surprisingly, increasing the temperature from 50 °C to elevated temperatures (70 and 100 °C) resulted in the maximum yield (96%), and 70 °C was found to be the optimum temperature (Table 1). As we continued our attempts to find maximized conditions, the value of the catalytic amount was examined. The different amounts of supported palladium catalysts were determined in coupling reactions of iodobenzene and phenylboronic acid. We have described in Table 1 that an excellent output was acquired with 0.22 mol % of catalyst. Thus, a 1:1.5 ratio of iodobenzene and K2CO3 at a temperature of 70 °C in the presence of 0.22 mol % catalyst in aqueous media was found to be excellent optimized conditions (Table 1, entry 4).

Under these optimized conditions, the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction’s scope is continued to numerous aryl halides accompanying phenylboronic acids, as shown in Table 2. The catalyst gave a high biphenyl yield in reactions of substrates with aryl iodide and aryl bromide. The highest biphenyl yields were obtained from the reaction of phenylboronic acid with aryl halides (iodide and bromide); 96 and 90%, respectively. Electron-releasing groups such as −CH3, −NH2, −OCH3, and −OH gave a high product yield. For example, phenylboronic acids with p-OH, p-CH2Br, and o-OCH3 gave biphenyl yields of 94, 88, and 85%, respectively. Aryl iodides with para-substituted −CH3 and −NH2 gave high biphenyl yields, 90% and 88%, respectively. A relatively low biphenyl yield was achieved in the reaction with the electron-withdrawing group (−NO2). The catalyst found to be more effective in the reaction of substrates with electron-releasing groups. A yield of 20–96% was achieved with a reaction time of 25 min to 24 h and also with a high turnover number (TON) and turnover frequency (TOF), as shown in Table 2. The formed products were confirmed by recording the 1H NMR spectra, checking their melting point (m.p.)/boiling point (b.p), and comparing them with the literature. Representative spectra are presented in the Supporting Information.

Table 2. Reaction Time, Isolated Yield, and the Melting Point of the Acquired Products in the Suzuki–Miyaura Cross-Coupling Reactiona.

| melting

point (C) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aEntry | R | X | R1 | time (min) | yield (%) | TON | TOF (h–1) | observed | literature | ref. |

| 01 | H | I | 20 | 96 | 427 | 1295 | 69–72 | 69–71 | (51) | |

| 02 | p-OH | I | 25 | 94 | 419 | 1006 | 163–165 | 164–166 | (52) | |

| 03 | o-OCH3 | I | 45 | 85 | 378 | 505 | 87–90 | 87–89 | (52) | |

| 04 | p-CH2Br | I | 40 | 88 | 392 | 594 | 82–84 | 83–86 | (53) | |

| 05 | H | Br | 30 | 90 | 401 | 801 | 69–72 | 69–71 | (51) | |

| 06 | p-OH | Br | 45 | 91 | 405 | 540 | 163–165 | 160–166 | (52) | |

| 07 | o-OCH3 | Br | 40 | 80 | 356 | 540 | 87–90 | 87–89 | (52) | |

| 08 | p-CH2Br | Br | 45 | 82 | 365 | 487 | 82–84 | 83–86 | (53) | |

| 09 | H | Cl | 720 | 74 | 329 | 27 | 69–72 | 69–71 | (51) | |

| 10 | p-OH | Cl | 720 | 65 | 289 | 24 | 82–84 | 164–166 | (52) | |

| 11 | o-OCH3 | Cl | 720 | 65 | 289 | 24 | 87–90 | 87–89 | (52) | |

| 12 | p-CH2Br | Cl | 720 | 70 | 312 | 26 | 82–84 | 83–86 | (53) | |

| 13 | H | I | p-CH3 | 35 | 90 | 401 | 687 | 41–44 | 42–44 | (54) |

| 14 | H | I | p-NH2 | 40 | 88 | 392 | 588 | 50–53 | 51 | (55) |

| 15 | H | Br | p-CH3 | 45 | 85 | 378 | 505 | 41–44 | 42–44 | (54) |

| 16 | H | Br | p-NH2 | 50 | 84 | 374 | 449 | 50–53 | 51 | (55) |

Reaction conditions: aryl halides (1 mmol), phenylboronic acids (1.2 mmol), K2CO3 (1.5 mmol), H2O (2 mL), and the Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd (0.22 mol %) catalyst was agitated at 70 °C for 20–720 min.

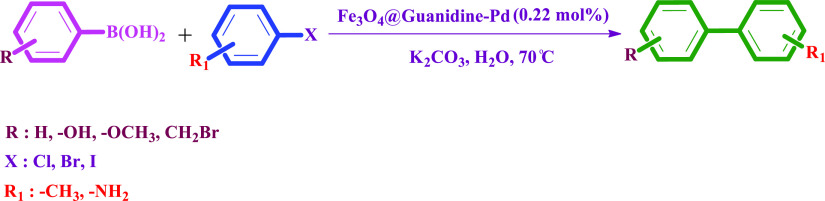

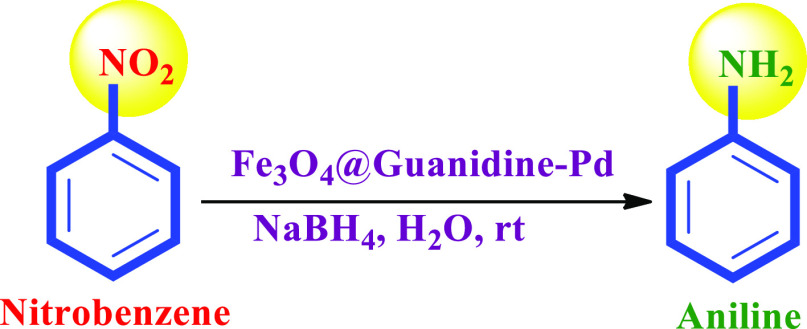

2.2.2. Selective Reduction of Nitroarenes

After characterizing the Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd catalyst, the catalytic features were examined to synthesize less-toxic amino compounds by reducing nitroarenes. With this concern, the reaction of nitrobenzene (1 mmol) and NaBH4 (2 mmol) in water at room temperature was picked out as the model reaction to enhance the reaction conditions. A blank experiment was conducted without catalyst for a preliminary evaluation, in which a small product was formed despite an extended time (Table 3, entry 1). Furthermore, the catalyst was separated from the reaction mixture in the middle of the process, that is, at 50% conversion, and we observed no transformation after removing the catalyst, indicating the catalyst’s significant role in the conversion. At first, the influence of the catalyst quantity on the reaction results was examined. As shown in Table 3 (entry 4), 0.13 mol % of the Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd catalyst is enough to complete the reaction in 10 min in the presence of 1:2 mmol nitrobenzene/sodium borohydride in water medium at normal temperature. We further observed the effects of several influential parameters on the model reaction (Table 3) and the accomplishment of the process was examined by thin-layer chromatography (TLC).

Table 3. Optimization of the Reaction Conditions for Reduction of Nitrobenzene to Aniline.

| entrya | catalyst (mol %) | nitrobenzene/hydrogen source (mmol) | hydrogen source | solvent | time (min) | isolated yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | without catalyst | 1:2 | NaBH4 | H2O | 1440 | no reaction |

| 2 | 0.08 | 1:2 | NaBH4 | H2O | 40 | 85 |

| 3 | 0.11 | 1:2 | NaBH4 | H2O | 30 | 92 |

| 4 | 0.13 | 1:2 | NaBH4 | H2O | 10 | 99 |

| 5 | 0.15 | 1:2 | NaBH4 | H2O | 15 | 99 |

| 6 | 0.13 | 1:1 | NaBH4 | H2O | 45 | 82 |

| 7 | 0.13 | 1:3 | NaBH4 | H2O | 20 | 99 |

| 8 | 0.13 | 1:2 | N2H4·H2O | H2O | 30 | 82 |

| 9 | 0.13 | 1:2 | NaBH4 | EtOH | 40 | 89 |

| 10 | 0.13 | 1:2 | NaBH4 | EtOH/H2O (1:1) | 30 | 93 |

| 11 | 0.13 | 1:2 | NaBH4 | methanol | 60 | 86 |

Optimized reaction conditions: nitrobenzene (1 mmol), NaBH4 (2 mmol), and the Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd (0.13 mol %) catalyst was agitated at room temperature for 10 min.

Moreover, to examine the opportunity and abstraction of the explained method, the enhanced reaction parameters were implemented for the reduction of various nitroarenes along with a high TON and TOF, as mentioned in Table 4. In all instances, the reduction was finished by 40 min resulting in tremendous yields (Table 4). Nitroarenes with o-chloro, m-chloro, 3-bromo, 4-bromo, and p-fluoro (Table 4) are completely scaled down to similar amines devoid of any dehalogenation. Electron-donating groups (such as −OCH3 and −CH3) (Table 4) and electron-withdrawing groups (such as −C=OR and −COOH) are selectively scaled down to similar amines with good yields. Reduction of o-nitrophenol, m-nitrophenol, p-nitrophenol, and 2-chloro-p-nitrophenol with sodium borohydride selectively gave the corresponding amino compounds as a single product (Table 4) within 10–30 min without disturbing the −OH group. After completing the reaction, pure products were achieved by simple workup, including magnetic separation and column chromatography.

Table 4. Reaction Time, Isolated Yield, and the Melting Point of the Obtained Products in the Selective Reduction of Electronically Diversified Nitroarenesa.

| melting

point (°C) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aentry | substrate | time (min) | yield (%) | TON | TOF (h–1) | observed | literature | ref. |

| 01 | nitrobenzene | 10 | 99 | 762 | 4760 | 184b | 184.1b | (56) |

| 02 | o-nitrophenol | 20 | 94 | 723 | 2191 | 170–173 | 170–175 | (57) |

| 03 | m-nitrophenol | 15 | 96 | 738 | 2954 | 119–122 | 120–124 | (57) |

| 04 | p-nitrophenol | 10 | 99 | 762 | 4760 | 186–189 | 185–189 | (57) |

| 05 | 2-chloro-p-nitrophenol | 30 | 92 | 708 | 1415 | 150–152 | 151.5 | (57) |

| 06 | m-nitroacetophenone | 20 | 97 | 747 | 2261 | 96–98 | 97 | (57) |

| 07 | p-nitroacetophenone | 15 | 98 | 754 | 3015 | 105–107 | 106 | (57) |

| 08 | p-nitroaniline | 40 | 96 | 738 | 1119 | 139–142 | 140 | (57) |

| 09 | m-chloronitrobenzene | 30 | 96 | 738 | 1477 | 94–96b | 95–96b | (57) |

| 10 | 3,4-dichloronitrobenzene | 30 | 92 | 708 | 1415 | 70–72 | 69–71 | (57) |

| 11 | 5-chloro-o-nitroaniline | 25 | 97 | 746 | 1794 | 68–70 | 68.5 | (57) |

| 12 | p-bromonitrobenzene | 30 | 90 | 692 | 1385 | 66–66.5 | 66 | (57) |

| 13 | 3-bromo-p-methoxynitrobenzene | 40 | 92 | 708 | 1072 | 61–62 | 62 | (58) |

| 14 | o-bitrothiophenol | 30 | 87 | 669 | 1338 | 17–21 | 19 | (57) |

| 15 | 2,3-dimethyl-6-nitroaniline | 25 | 88 | 677 | 1627 | 87–89 | 86–90 | (59) |

| 16 | p-methoxy-2,3-dimethylnitrobenzene | 40 | 92 | 708 | 1072 | 269b | 265.4 ± 35b | (60) |

| 17 | o-nitro benzoic acid | 30 | 88 | 677 | 1354 | 142–145 | 144–148 | (57) |

| 18 | m-nitro benzoic acid | 20 | 92 | 708 | 2145 | 178–180 | 178–180 | (57) |

| 19 | p-nitro benzoic acid | 15 | 96 | 738 | 2954 | 186–188 | 189 | (57) |

| 20 | 3-methoxy-o-nitrobenzoic acid | 40 | 86 | 662 | 1002 | 169–170 | 169–170 | (57) |

Optimized reaction conditions: nitrobenzene (1 mmol), NaBH4 (2 mmol), and the Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd (0.13 mol %) catalyst was stirred at room temperature for 10–40 min.

Liquid (boiling point).

The formed products were confirmed by recording the 1H NMR spectra, checking their m.p./b.p., and comparing them with the previously obtained data.

2.3. Comparative Study

To illustrate the benefits of present catalytic systems over the Pd-related catalytic process described in the Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling and selective reduction of nitroarenes, the related efficiency outcomes are discussed in Table 5. It is observed that the existing catalysts outperform almost all previously mentioned catalysts in terms of accessible reaction parameters, limited reaction durations, a higher reaction performance, and a lower catalyst loading, as well as magnetic catalyst retrieval with acceptable reuse. These results prove the existing catalytic system’s superiority in preserving time and energy, acquiring high reaction yields.

Table 5. Comparative Study of the Catalytic Ability of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd with Earlier Reported Catalysts for the Suzuki–Miyaura Cross-Coupling Reaction and Selective Reduction of Nitroarenes.

| catalyst (mol %) | reaction conditions | time (min) | yield (%) | reusability | ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd–CoFe2O4 MNPs (1.6) | ArB(OH)2 (0.75 mmol), ArX (0.5 mmol), Na2CO3, ethanol, reflux | 720 | 81 | 4 | (61) |

| Fe3O4@C–Pd@mSiO (1.5) | ArB(OH)2 (1.5 equiv), ArX (1.0 equiv), K2CO3, iPrOH, 70 °C | 360 | 99 | 6 | (62) |

| Fe3O4@Pd-OA (1.5) | ArB(OH)2 (1.2 equiv), ArX (1.0 equiv), K3PO4, DMF, 115 °C | 300 | 94 | 4 | (63) |

| Fe3O4@EDTA-PdCl2 (20 mg) | ArB(OH)2 (1.1 mmol), ArX (1 mmol), K2CO3, TBAB, H2O, 80 °C | 180 | 94 | 5 | (64) |

| Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd (0.22) | ArB(OH)2(1.2 mmol),ArX(1.0 mmol),K2CO3, H2O,70 °C | 20 | 96 | 5 | present worka |

| Mag-IL-Pd (0.5) | Ar-NO2 (0.25 mmol), HCO2NH4 (4 equiv), H2O, 90 °C | 900 | 99 | 8 | (65) |

| Pd-GO/CNT–Fe3O4 (1) | Ar-NO2 (0.5 mmol), H2 (1 atm), H2O, 60 °C | 180 | 90 | 4 | (66) |

| Fe3O4@C–Pd (40 mg) | Ar-NO2 (1 mmol), NaBH4 (3 mmol), EtOH, 25 °C | 60 | 99 | 6 | (67) |

| C–Pd–Fe3O4 (20 mg) | Ar-NO2 (1 mmol), NaBH4 (3 mmol), EtOH, 25 °C | 30 | 99 | 7 | (68) |

| Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd (0.13) | Ar-NO2 (1 mmol),NaBH4(3 mmol)H2O, rt | 10 | 99 | 8 | present workb |

Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction.

Reduction of nitroarenes.

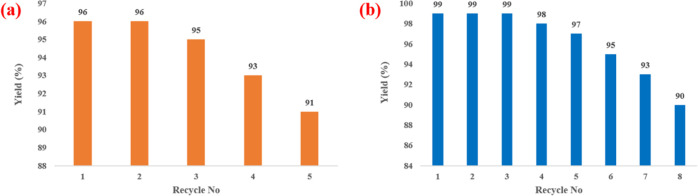

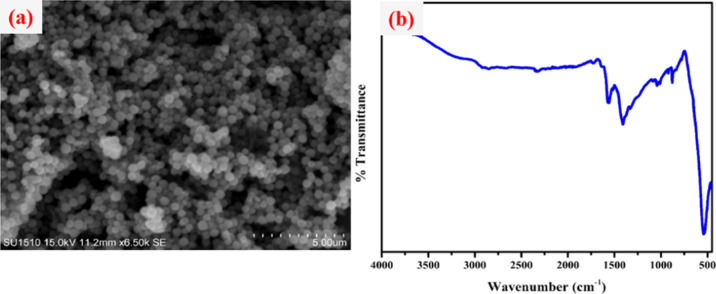

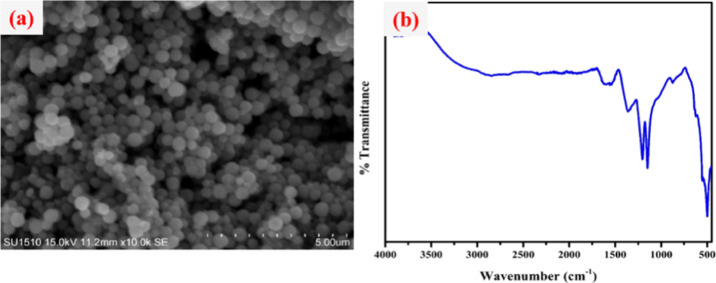

2.4. Reusability Study

The recovery and recyclability of the Fe3O4@guanidine-Pd catalyst were examined for the Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction and selective reduction nitroarene reactions and it was noticed that the catalyst had admirable recyclability. Subsequently, the catalyst was easily separated from the mixture using an external magnet, and purified several times using ethanol. The round-bottomed flask was later charged with a fresh reaction mixture of each catalytic system for the next cycle. It was observed that catalysts could be recycled up to eight times, devoid of considerable loss in weight and performance, as shown in Figure 7. Besides, the SEM image and the FT-IR spectra of the recycled catalysts after eight cycles indicated that they had retained their morphology and possessed very high stability (Figures 8 and 9).

Figure 7.

Reusability of the Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd catalyst in (a) Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction and (b) selective reduction of nitroarenes under optimized conditions.

Figure 8.

(a) SEM image and (b) FTIR spectra of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd for the Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction after eight cycles.

Figure 9.

(a) SEM image and (b) FTIR spectra of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd for the selective reduction of nitroarenes after eight cycles.

2.5. Heterogeneity Test

The hot filtration and leaching test were used to confirm the heterogeneous characteristics of the synthesized material, regardless of whether any catalyst particles were leached in the filtrate solution. The Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction was carried out on a nanocatalyst for 10 min under optimal reaction conditions, after which the solution mixture was divided into two-halves. The catalyst was removed from one part of the reaction mixture using a magnetic field source and the reaction of both parts was carried out for an additional 10 min. Similarly, the nitrobenzene reduction reaction was performed employing a nanocatalyst under optimal conditions for 5 min, followed by division of solutions into two equal parts. As mentioned before, the catalyst in one part was recovered using a magnetic field and then each of the reactions allowed to proceed for a further 5 min. It was found that in a non-catalytic environment, no conversion was observed, while the other portion that led to the completion of the reaction is shown in the Supporting Information (Figure S1). This also suggests that virtually no leaching of Pd(II) occurred in the reaction mixture, which confirms its factual heterogeneity.

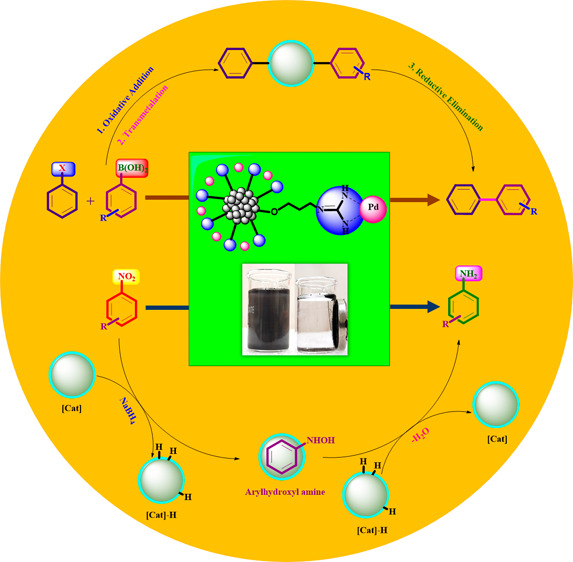

2.6. Proposed Plausible Catalytic Mechanism for the Suzuki–Miyaura Cross-Coupling Reaction

According to previous reports,15 the following plausible mechanism of the Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction can be observed (Figure S3). This mechanism includes three consecutive stages: oxidative addition, transmetalation, and reduction withdrawal. At the oxidative addition stage, Pd(0) undergoes oxidative inclusion by an aryl halide (Ar1-X) to result a σ-aryl complex of Pd(II) (Ar1-Pd(II)-X) (I). Then, at the stage of transmetalation, the aryl group of stimulated aryl boronic acid (Ar2-M-OH) (II) is exchanged using halide of the σ-aryl complex (Ar1-Pd(II)-X) (I) to form a biphenyl complex Pd(II) (Ar1-Pd(II)-Ar2) (III). Finally, the reductive elimination of Ar1-Pd(II)-Ar2 (III), offering the Pd(0) complex by the liberation of the corresponding biphenyl compound (Ar1-Ar2) (IV).

2.7. Proposed Plausible Catalytic Mechanism for Selective Reduction of Nitroarenes

From the previous reports,50 the following plausible mechanism for the reduction of nitroarenes can be proposed, as shown in Figure S4. At first, NaBH4 ionizes in an aqueous medium presented by the formation of borohydride ions [BH4]− that occupy on the surface of the palladium catalyst causing the formation of a palladium hydride complex (Pd–H). Then, the nitro compound (C6H5–NO2) is present on the surface of the Pd–hydride complex, and both processes are reversible, that is, adsorption and desorption. If each substrate is chemisorbed on the catalyst surface, hydrogen will be transferred from the Pd–hydride complex to the corresponding amines (C6H5–NH2).

3. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the preparation of Pd immobilized on guanidine-conjugated Fe3O4 nanoparticles (Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd) as immensely effectual magnetically recoverable and as a recyclable heterogeneous catalyst, designed in favor of preparing some biaryl compounds by Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reactions and also reduction of nitroarenes to corresponding less-toxic amines. The prepared Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd catalyst resulted a potent yield (of about 96%) even with a small quantity of the catalyst (0.22 mol %) in an aqueous medium with a limited reaction duration (20 min) by a convenient work-up process for all Suzuki coupling reactions. Furthermore, Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd was utilized as a novel heterogeneous catalyst for reducing nitroarenes employing NaBH4 as a derivative of hydrogen in aqueous media at room temperature. This catalyst effectively reduced substituted nitroarenes to the corresponding amines in a limited reaction duration of 10–40 min in excellent yields (0.13 mol %, 99%). Additionally, reproducibility tests showed that the Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd catalyst was an effective recoverable material that could be reused for several cycles without compromising the activity in the Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction and selective reduction of nitroarenes. The practical reusability and convenient recoverability of the developed catalysts are significant parameters that improve their potential for commercial and industrial applications. Moreover, all biphenyl and amine derivatives were distinguished by a high TON and TOF, demonstrating the increased efficiency and selectivity of the Fe3O4@guanidine-Pd catalyst in the Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction and the selective reduction of nitroarenes. Thus, we conclude that applying these effective catalysts for reducing toxic dyes and chemicals will reduce the pollution and cost of producing beneficial compounds.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials and Methods

All the chemicals and solvents utilized in this experiment were obtained from Merck and Sigma-Aldrich. They were utilized during synthesis to prevent additional treatment. The sterility of the resulting products in addition to their advancement of organic reactions was evaluated with TLC on Silica gel 60 F254 Plates. The prepared catalyst materials were examined for their crystal structure using a Rigaku X-ray diffractometer. The catalyst’s surface morphology and particle size were analyzed utilizing a scanning electron microscope (HITACHI SU15010) and high-resolution transmission electron microscope (JEOL/JEM 2100). The functional group analysis was accomplished using (FT-IR) spectroscopy (Perkin Elmer Spectrum Two). The TG-DTA was performed by employing Perkin Elmer STA 8000. The catalyst’s elemental composition and oxidation states were analyzed using a X-ray photoelectron spectrometer from ULVAC-PHI Japan. The metal ion concentration was determined employing inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer from Perkin Elmer Optima 5300DV. The catalyst’s magnetic property was scrutinized using a vibrating sample magnetometer maintained at room temperature utilizing Lakeshore VSM7410.

4.2. Preparation of Guanidine-Conjugated Fe3O4 Nanoparticles

In a round-bottomed flask, the as-prepared Fe3O4 nanoparticles (1 g) (prepared via a solvothermal method according to the previous report45) and 1-bromo-3-chloropropane (4.31 mmol) were sonicated for 10 min in ethanol (10 mL), and later the formed solution is agitated for 6 h at normal temperature. After the alkylation of OH groups on Fe3O4, the substance was removed by utilizing an external magnet and purified using ethanol (EtOH) (5 × 5 mL) and dried. The dried powder (0.254 g) was then distributed in dry toluene, followed by sonication for 10 min. Then, guanidine hydrochloride (10.09 mmol/g) and sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) (11.91 mmol/g) were combined to the above mixture and then refluxed for 12 h. On the subsequent accomplishment of this reaction, the resultant was isolated with the help of a magnet and washed using dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) (3 × 5 mL) and EtOH (2 × 5 mL). The obtained product was dehydrated at room temperature for 6 h and preserved.

4.3. Immobilization of Pd on Guanidine-Conjugated Fe3O4 Nanoparticles

In a round-bottomed flask, Fe3O4@Guanidine (0.35 g) and palladium acetylacetonate (4.8611 mmol/g) were sonicated in methanol (10 mL) for a duration of 30 min and the substances were refluxed for as long as 6 h. The resulting product was obtained with the help of an external magnet, purified with DI H2O (5 × 5 mL) and EtOH (3 × 5 mL), and evaporated at 60 °C for 6 h using a hot air oven to obtain Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd.

4.4. General Method for C–C Cross-Coupling Reactions

In a round-bottomed flask, the Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd catalyst (0.22 mol %) was added to the mixture of aryl halide (1 mmol) and phenylboronic acid (1.2 mmol), along with potassium carbonate (K2CO3) (1.5 mmol) in water (2 mL) medium, which was boiled up to 70 °C and subsequently stirred for an appropriate time (Table 1). The progress of the experiment was observed by TLC. After the completion of the process, the catalysts were isolated utilizing an external magnet, and then the reaction composite was retrieved using ethyl acetate (EtOAc) (5 × 3 mL). The dissolvent was withdrawn at decreased pressure to acquire the crude biphenyls; later, they were isolated using column chromatography on silica gel with n-hexane/EtOAc (7:3).

4.5. General Method for Selective Reduction of Nitroarenes

In a round-bottomed flask, nitro compound (1 mmol) and sodium borohydride (NaBH4) (3 mmol) were dissolved in water (2 mL). The obtained compound was agitated for 5 min at normal temperature to get a clear solution. Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd (0.13 mol %) was included in the solution mixture that was agitated at a suitable time (Table 3) at normal temperature. The progress of the experiment was examined by TLC. Then, the catalyst was isolated with an external magnet, after which the solution mixture was obtained using EtOAc (2 × 5 mL). The organic compound extracted from ethyl acetate was evaporated to obtain the crude amines, which were then isolated using column chromatography on silica gel with n-hexane/EtOAc (4:1).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Department of Science and Technology (DST), Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India for financial assistance through Junior Research Fellowship to Guddappa Halligudra under Innovation in Science Pursuit for Inspired Research (INSPIRE) scheme (sanction no. DST/INSPIRE/03/2015/003933 registration no: IF160537).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c04528.

Hot filtration and leaching test of Fe3O4@Guanidine-Pd for Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling and nitroarene reduction reactions; photograph of the separation of the catalyst using an external magnet; plausible mechanism for the Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling and nitroarene reduction reactions; and 1H NMR spectra of the selected products (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Baran T.; Sargın İ.; Kaya M.; Mulerčikas P.; Kazlauskaitė S.; Menteş A. Production of Magnetically Recoverable, Thermally Stable, Bio-Based Catalyst: Remarkable Turnover Frequency and Reusability in Suzuki Coupling Reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 331, 102–113. 10.1016/j.cej.2017.08.104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baran T. Biosynthesis of Highly Retrievable Magnetic Palladium Nanoparticles Stabilized on Bio-Composite for Production of Various Biaryl Compounds and Catalytic Reduction of 4-Nitrophenol. Catal. Lett. 2019, 149, 1721–1729. 10.1007/s10562-019-02753-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baran T.; Nasrollahzadeh M. Facile Fabrication of Magnetically Separable Palladium Nanoparticles Supported on Modified Kaolin as a Highly Active Heterogeneous Catalyst for Suzuki Coupling Reactions. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2020, 146, 109566. 10.1016/j.jpcs.2020.109566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmati S.; Mehrazin L.; Pirhayati M.; Veisi H. Immobilization of Palladium Nanoparticles on Metformin-Functionalized Graphene Oxide as a Heterogeneous and Recyclable Nanocatalyst for Suzuki Coupling Reactions and Reduction of 4-Nitrophenol. Polyhedron 2019, 158, 414–422. 10.1016/j.poly.2018.11.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma C.; Srivastava A. K.; Soni A.; Kumari S.; Joshi R. K. CO-free, aqueous mediated, instant and selective reduction of nitrobenzene via robustly stable chalcogen stabilised iron carbonyl clusters (Fe3E2(CO)9, E = S, Se, Te). RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 32516–32521. 10.1039/d0ra04491a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikkanayakanahalli Paramesh C.; Halligudra G.; Gangaraju V.; Sriramoju J. B.; Shastri M.; Kachigere B H.; Habbanakuppe D P.; Rangappa D.; Kanchugarakoppal Subbegowda R.; Doddakunche Shivaramu P. Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized Using Saponin Extract of Simarouba Glauca Oil Seed Meal as Effective, Recoverable and Reusable Catalyst for Reduction of Organic Dyes. Results in Surfaces and Interfaces 2021, 3, 100005. 10.1016/j.rsurfi.2021.100005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrollahzadeh M.; Bidgoli N. S. S.; Issaabadi Z.; Ghavamifar Z.; Baran T.; Luque R. Hibiscus Rosasinensis L. aqueous extract-assisted valorization of lignin: Preparation of magnetically reusable Pd NPs@Fe3O4-lignin for Cr(VI) reduction and Suzuki-Miyaura reaction in eco-friendly media. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 148, 265–275. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A. K.; Ali M.; Siangwata S.; Satrawala N.; Smith G. S.; Joshi R. K. Multitasking FeOCN Composite as an Economic, Heterogeneous Catalyst for 1-Octene Hydroformylation and Hydration Reactions. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2020, 9, 377–384. 10.1002/ajoc.201900649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luconi L.; Gafurov Z.; Rossin A.; Tuci G.; Sinyashin O.; Yakhvarov D.; Giambastiani G. Palladium(II) pyrazolyl-pyridyl complexes containing a sterically hindered N-heterocyclic carbene moiety for the Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2018, 470, 100–105. 10.1016/j.ica.2017.03.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y.; Wu X.; Chen X.; Wei Y. N-Methylimidazole Functionalized Carboxymethycellulose-Supported Pd Catalyst and Its Applications in Suzuki Cross-Coupling Reaction. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 160, 106–114. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshminarayana B.; Satyanarayana G.; Subrahmanyam C. Bimetallic Pd-Au/TiO2 Nanoparticles: An Efficient and Sustainable Heterogeneous Catalyst for Rapid Catalytic Hydrogen Transfer Reduction of Nitroarenes. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 13065–13072. 10.1021/acsomega.8b02064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee T. K.; Sen D. Homogeneous Reduction of Aromatic Nitrocompounds by a Triphenylphosphine Complex of Palladium. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 1981, 31, 676–682. 10.1002/jctb.280310190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kandathil V.; Kulkarni B.; Siddiqa A.; Kempasiddaiah M.; Sasidhar B. S.; Patil S. A.; Patil S. A. Immobilized N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Palladium(II) Complex on Graphene Oxide as Efficient and Recyclable Catalyst for Suzuki-Miyaura Cross-Coupling and Reduction of Nitroarenes. Catal. Lett. 2020, 150, 384–403. 10.1007/s10562-019-03083-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duan X.; Liu J.; Hao J.; Wu L.; He B.; Qiu Y.; Zhang J.; He Z.; Xi J.; Wang S. Magnetically Recyclable Nanocatalyst with Synergetic Catalytic Effect and Its Application for 4-Nitrophenol Reduction and Suzuki Coupling Reactions. Carbon 2018, 130, 806–813. 10.1016/j.carbon.2018.01.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jahanshahi R.; Akhlaghinia B. Thiophene Methanimine-Palladium Schiff Base Complex Anchored on Magnetic Nanoparticles: A Novel, Highly Efficient and Recoverable Nanocatalyst for Cross-Coupling Reactions in Mild and Aqueous Media. Catal. Lett. 2017, 147, 2640–2655. 10.1007/s10562-017-2170-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. W. On the Stability and Recyclability of Supported Metal–Ligand Complex Catalysts: Myths, Misconceptions and Critical Research Needs. Top. Catal. 2010, 53, 942–952. 10.1007/s11244-010-9513-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sajjadi M.; Baran N. Y.; Baran T.; Nasrollahzadeh M.; Tahsili M. R.; Shokouhimehr M. Palladium Nanoparticles Stabilized on a Novel Schiff Base Modified Unye Bentonite: Highly Stable, Reusable and Efficient Nanocatalyst for Treating Wastewater Contaminants and Inactivating Pathogenic Microbes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 237, 116383. 10.1016/j.seppur.2019.116383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baran N. Y.; Baran T.; Nasrollahzadeh M.; Varma R. S. Pd Nanoparticles Stabilized on the Schiff Base-Modified Boehmite: Catalytic Role in Suzuki Coupling Reaction and Reduction of Nitroarenes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2019, 900, 120916. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2019.120916. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baran T.; Açıksöz E.; Menteş A. Carboxymethyl chitosan Schiff base supported heterogeneous palladium(II) catalysts for Suzuki cross-coupling reaction. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2015, 407, 47–52. 10.1016/j.molcata.2015.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khandaka H.; Sharma K. N.; Joshi R. K. Aerobic Cu and amine free Sonogashira and Stille couplings of aryl bromides/chlorides with a magnetically recoverable Fe3O4@SiO2 immobilized Pd(II)-thioether containing NHC. Tetrahedron Lett. 2021, 67, 152844. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2021.152844. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomar V.; Upadhyay Y.; Srivastava A. K.; Nemiwal M.; Joshi R. K.; Mathur P. Selenated NHC-Pd(II) catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of ferrocene substituted β-chloro-cinnamaldehydes, acrylonitriles and malononitriles for the synthesis of novel ferrocene derivatives and their solvatochromic studies. J. Organomet. Chem. 2021, 940, 121752. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2021.121752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nayan Sharma K.; Satrawala N.; Kumar Joshi R. Thioether-NHC-Ligated Pd II Complex for Crafting a Filtration-Free Magnetically Retrievable Catalyst for Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling in Water. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 1743–1751. 10.1002/ejic.201800209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hollas A. M.; Gu W.; Bhuvanesh N.; Ozerov O. V. Synthesis and Characterization of Pd Complexes of a Carbazolyl/Bis(Imine) NNN Pincer Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 3673–3679. 10.1021/ic200026p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma C.; Srivastava A. K.; Sharma K. N.; Joshi R. K. Half-sandwich (η5-Cp*)Rh(iii) complexes of pyrazolated organo-sulfur/selenium/tellurium ligands: efficient catalysts for base/solvent free C-N coupling of chloroarenes under aerobic conditions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 3599–3606. 10.1039/d0ob00538j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veisi H.; Hamelian M.; Hemmati S. Palladium anchored to SBA-15 functionalized with melamine-pyridine groups as a novel and efficient heterogeneous nanocatalyst for Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reactions. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2014, 395, 25–33. 10.1016/j.molcata.2014.07.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sobhani S.; Pakdin-parizi Z. Palladium-DABCO complex supported on γ-Fe2O3 magnetic nanoparticles: A new catalyst for CC bond formation via Mizoroki-Heck cross-coupling reaction. Appl. Catal., A 2014, 479, 112–120. 10.1016/j.apcata.2014.04.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ratheesh Kumar V. K.; Gopidas K. R. Palladium nanoparticle-cored G1-dendrimer stabilized by carbon-Pd bonds: synthesis, characterization and use as chemoselective, room temperature hydrogenation catalyst. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 3102–3105. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X.; Yan M.; Zhang T.; Liu Y.; Bao M. Preparation and Application of SBA-15-Supported Palladium Catalyst for Suzuki Reaction in Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 1758–1766. 10.1039/c004250a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morita A.; Misaki T.; Sugimura T. 1,6-Addition Reaction of 5H-Oxazol-4-ones to Conjugated Dienones Catalyzed by Chiral Guanidines. Chem. Lett. 2014, 43, 1826–1828. 10.1246/cl.140713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q.; Tang Y.; Huang T.; Liu X.; Lin L.; Feng X. Copper/Guanidine-Catalyzed Asymmetric Alkynylation of Isatins. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 5286–5289. 10.1002/anie.201600711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y.; Cui X. Y.; Tan S. M.; Jiang H.; Ren J.; Lee N.; Lee R.; Tan C. H. Guanidine-Copper Complex Catalyzed Allylic Borylation for the Enantioconvergent Synthesis of Tertiary Cyclic Allylboronates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 2382–2386. 10.1002/anie.201813490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaabani A.; Hezarkhani Z.; Nejad M. K. AuCu and AgCu bimetallic nanoparticles supported on guanidine-modified reduced graphene oxide nanosheets as catalysts in the reduction of nitroarenes: tandem synthesis of benzo[b][1,4]diazepine derivatives. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 30247–30257. 10.1039/c6ra03132c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qin S.-S.; Wang Z.-K.; Hu L.; Du X.-H.; Wu Z.; Strømme M.; Zhang Q.-F.; Xu C. Dual-Functional Ionic Porous Organic Framework for Palladium Scavenging and Heterogeneous Catalysis. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 3967–3973. 10.1039/d1nr00172h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil S.; Tandon R.; Tandon N. A current research on silica coated ferrite nanoparticle and their application: Review. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 4, 100063. 10.1016/j.crgsc.2021.100063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W.; Cheng Q.; Ma D. Recent Reports on Magnetic Nanoparticles Supported Metallic Catalysts: Synthesis of Heterocycles. Synth. Commun. 2021, 51, 1321–1339. 10.1080/00397911.2021.1884882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vinaya K.; Shivaramu P. D.; Chandrashekara G. K.; Chandrappa S.; Rangappa K. S. T3P -DMSO Mediated One-pot Tandem Approach for the Synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones/thiones from Alcohols. Lett. Org. Chem. 2018, 15, 241–245. 10.2174/1570178614666170720115044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vinaya K.; Chandrashekara G. K.; Shivaramu P. D. One-Pot Synthesis of 3,5-Diaryl Substituted-1,2,4-Oxadiazoles Using Gem-Dibromomethylarenes. Can. J. Chem. 2019, 97, 690–696. 10.1139/cjc-2018-0333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrappa S.; Prasanna T. S. R.; Vinaya K.; Prasanna D. S.; Rangappa K. S. PCC-Promoted Dehydration of Aldoximes: A Convenient Access to Aromatic, Heteroaromatic, and Aliphatic Nitriles. Synth. Commun. 2013, 43, 2756–2762. 10.1080/00397911.2012.738459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikary J.; Datta A.; Dasgupta S.; Chakraborty A.; Menéndez M. I.; Chattopadhyay T. Development of an Efficient Magnetically Separable Nanocatalyst: Theoretical Approach on the Role of the Ligand Backbone on Epoxidation Capability. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 92634–92647. 10.1039/c5ra17484h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atashkar B.; Rostami A.; Tahmasbi B. Magnetic Nanoparticle-Supported Guanidine as a Highly Recyclable and Efficient Nanocatalyst for the Cyanosilylation of Carbonyl Compounds. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 2140–2146. 10.1039/c3cy00190c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani Firuzabadi F.; Asadi Z.; Panahi F. Immobilized NNN Pd-complex on magnetic nanoparticles: efficient and reusable catalyst for Heck and Sonogashira coupling reactions. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 101061–101070. 10.1039/c6ra22535g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Yang X.; Yu J. A Polysalen Based on Polyacylamide Stabilized Palladium Nanoparticle Catalyst for Efficient Carbonylative Sonogashira Reaction in Aqueous Media. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 31850–31857. 10.1039/c7ra04910b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grosvenor A. P.; Kobe B. A.; Biesinger M. C.; McIntyre N. S. Investigation of Multiplet Splitting of Fe 2p XPS Spectra and Bonding in Iron Compounds. Surf. Interface Anal. 2004, 36, 1564–1574. 10.1002/sia.1984. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sobhani S.; Chahkamali F. O.; Sansano J. M. A new bifunctional heterogeneous nanocatalyst for one-pot reduction-Schiff base condensation and reduction-carbonylation of nitroarenes. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 1362–1372. 10.1039/c8ra10212k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Yang J.; Li X.; Wei B.; Wang D.; Song H.; Zhai H.; Li X. Synthesis of Fe3O4@SiO2@ZnO-Ag core-shell microspheres for the repeated photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B under UV irradiation. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2015, 406, 97–105. 10.1016/j.molcata.2015.05.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qi B.; Di L.; Xu W.; Zhang X. Dry Plasma Reduction to Prepare a High Performance Pd/C Catalyst at Atmospheric Pressure for CO Oxidation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 11885–11890. 10.1039/c4ta02155j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrollahzadeh M.; Sajjadi M.; Khonakdar H. A. Synthesis and characterization of novel Cu(II) complex coated Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles for catalytic performance. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1161, 453–463. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.02.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kassaee M. Z.; Masrouri H.; Movahedi F. Sulfamic Acid-Functionalized Magnetic Fe3O4 Nanoparticles as an Efficient and Reusable Catalyst for One-Pot Synthesis of α-Amino Nitriles in Water. Appl. Catal., A 2011, 395, 28–33. 10.1016/j.apcata.2011.01.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santos E. C. S.; dos Santos T. C.; Guimarães R. B.; Ishida L.; Freitas R. S.; Ronconi C. M. Guanidine-functionalized Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles as basic recyclable catalysts for biodiesel production. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 48031–48038. 10.1039/c5ra07331f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R. K.; Monga Y.; Puri A. Magnetically separable silica@Fe3O4 core-shell supported nano-structured copper(II) composites as a versatile catalyst for the reduction of nitroarenes in aqueous medium at room temperature. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2014, 393, 84–95. 10.1016/j.molcata.2014.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savanur H. M.; Kalkhambkar R. G.; Laali K. K. Pd(OAc)2 catalyzed homocoupling of arenediazonium salts in ionic liquids: synthesis of symmetrical biaryls. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 663–667. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.12.108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fareghi-Alamdari R.; Golestanzadeh M.; Bagheri O. meso-Tetrakis[4-(methoxycarbonyl)phenyl]porphyrinatopalladium(ii) supported on graphene oxide nanosheets (Pd(ii)-TMCPP-GO): synthesis and catalytic activity. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 108755–108767. 10.1039/c6ra21223a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information . PubChem Compound Summary for CID 257716, 4-Bromomethylbiphenyl, 2020. Https://Pubchem.Ncbi.Nlm.Nih.Gov/Compound/4-Bromomethylbiphenyl. Accessed 3 October 2021.

- Yafele R. S.; Mabasa T. F.; Vatsha B.; Makhubela B. C. E.; Kinfe H. H. New Symmetrical N̂N̂N Palladium(II) Pincer Complexes: Synthesis, Characterization and Catalytic Evaluation in the Suzuki-Miyaura Cross-Coupling Reaction. Arkivoc 2020, 2020, 103–119. 10.24820/ark.5550190.p011.199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes W. M.CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics; CRC Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sobhani S.; Chahkamali F. O.; Sansano J. M. A New Bifunctional Heterogeneous Nanocatalyst for One-Pot Reduction-Schiff Base Condensation and Reduction-Carbonylation of Nitroarenes. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 1362–1372. 10.1039/c8ra10212k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley J.-C.; Lang A.; Williams A.. Jean-Claude Bradley Double Plus Good (Highly Curated and Validated) Melting Point Dataset; Figshare Dataset, 2014.

- Emokpae T. A.; Eguavoen O.; Khalil-Ur-Rahman; Hirst J. The kinetics of the reactions of picryl chloride with some substituted anilines. Part 6. 4-Substituted and 3,4-disubstituted anilines. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1980, 832–834. 10.1039/p29800000832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K.; Kidawara M.; Iseki M.; Umegaki C.; Kishi T. A Simple Fluorometric Determination of Vitamin C. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1998, 46, 1474–1476. 10.1248/cpb.46.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sako M.; Ichinose K.; Takizawa S.; Sasai H. Short Syntheses of 4-Deoxycarbazomycin B, Sorazolon E, and (+)-Sorazolon E2. Chem.—Asian J. 2017, 12, 1305–1308. 10.1002/asia.201700471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senapati K. K.; Roy S.; Borgohain C.; Phukan P. Palladium Nanoparticle Supported on Cobalt Ferrite: An Efficient Magnetically Separable Catalyst for Ligand Free Suzuki Coupling. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2012, 352, 128–134. 10.1016/j.molcata.2011.10.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z.; Yang J.; Wang J.; Li W.; Kaliaguine S.; Hou X.; Deng Y.; Zhao D. A versatile designed synthesis of magnetically separable nano-catalysts with well-defined core-shell nanostructures. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 6071–6074. 10.1039/c3ta14046f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelletti A. L.; Uberman P. M.; Martín S. E.; Saleta M. E.; Troiani H. E.; Sánchez R. D.; Carbonio R. E.; Strumia M. C. Synthesis, Characterization, and Nanocatalysis Application of Core-Shell Superparamagnetic Nanoparticles of Fe3O4@Pd. Aust. J. Chem. 2015, 68, 1492–1501. 10.1071/ch14722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azizi K.; Ghonchepour E.; Karimi M.; Heydari A. Encapsulation of Pd(II) into superparamagnetic nanoparticles grafted with EDTA and their catalytic activity towards reduction of nitroarenes and Suzuki-Miyaura coupling. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2015, 29, 187–194. 10.1002/aoc.3258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi B.; Mansouri F.; Vali H. A Highly Water-Dispersible/Magnetically Separable Palladium Catalyst: Selective Transfer Hydrogenation or Direct Reductive N-Formylation of Nitroarenes in Water. Chempluschem 2015, 80, 1750–1759. 10.1002/cplu.201500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F.; Feng A.; Wang C.; Dong S.; Chi C.; Jia X.; Zhang L.; Li Y. Graphene oxide/carbon nanotubes-Fe3O4 supported Pd nanoparticles for hydrogenation of nitroarenes and C-H activation. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 16911–16916. 10.1039/c5ra25842a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mei N.; Liu B. Pd nanoparticles supported on Fe3O4@C: An effective heterogeneous catalyst for the transfer hydrogenation of nitro compounds into amines. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 17960–17966. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.07.229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P.; Li D.; Jin S.; Chen S.; Zhang Z. Catalytic Transfer Hydrogenation of Nitro Compounds into Amines over Magnetic Graphene Oxide Supported Pd Nanoparticles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 15218–15224. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.06.257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.