The surge in background checks in March 2020 suggested an acceleration in U.S. firearm purchases. This survey-based study estimates the number of and describes characteristics of firearm purchasers over a period spanning time before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Visual Abstract. Firearm Purchasing During the COVID-19 Pandemic.

The surge in background checks in March 2020 suggested an acceleration in U.S. firearm purchases. This survey-based study estimates the number of and describes characteristics of firearm purchasers over a period spanning time before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Abstract

Background:

The surge in background checks beginning in March 2020 suggested an acceleration in firearm purchases. Little was known about the people who bought these guns.

Objective:

To estimate the number and describe characteristics of firearm purchasers over a period spanning prepandemic and pandemic time, characterize new gun owners, and estimate the number of persons newly exposed to household firearms.

Design:

Probability-based online survey conducted in April 2021. Survey weights generated nationally representative estimates.

Setting:

United States, 1 January 2019 to 26 April 2021.

Participants:

19 049 of 29 985 (64%) English-speaking adults responded to the survey invitation; 5932 owned firearms, including 1933 who had purchased firearms since 2019, of whom 447 had become new gun owners.

Measurements:

The estimated number and characteristics of adults who, since 2019, have purchased firearms, distinguishing those who became new gun owners from those who did not, and the estimated number of household members newly exposed to firearms.

Results:

An estimated 2.9% of U.S. adults (7.5 million) became new gun owners from 1 January 2019 to 26 April 2021. Most (5.4 million) had lived in homes without guns, collectively exposing, in addition to themselves, over 11 million persons to household firearms, including more than 5 million children. Approximately half of all new gun owners were female (50% in 2019 and 47% in 2020 to 2021), 20% were Black (21% in 2019 and in 2020–2021), and 20% were Hispanic (20% in 2019 and 19% in 2020–2021). By contrast, other recent purchasers who were not new gun owners were predominantly male (70%) and White (74%), as were gun owners overall (63% male, 73% White).

Limitations:

Retrospective assessment of when respondents purchased firearms. National estimates about new gun owners were based on 447 respondents.

Conclusion:

Efforts to reduce firearm injury should consider the recent acceleration in firearm purchasing and the characteristics of new gun owners.

Primary Funding Source:

The Joyce Foundation.

The United States does not track gun sales to civilians. However, since 1998 it has tracked the number of background checks performed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation's (FBI) National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS), a metric that has since served as a rough but not validated proxy for firearm sales (1).

The large increase in the number of NICS checks beginning in March 2020 sent journalists searching for stories, most of which were conceived with reference to the developing COVID-19 pandemic (1). A salient narrative emerged that focused on a putative surge in new gun owners, especially among racial minorities and women (2). News reports often cited the only source of COVID-19–era gun sales available early in the pandemic: a small, nonrepresentative survey of 175 firearm retailers that estimated 40% of firearm purchasers since the pandemic began were first-time gun owners (3).

Public health researchers also sought to understand the surge in NICS checks. To date, however, only 2 peer-reviewed, probability-based surveys have estimated the proportion of recent firearm purchasers who were “new gun owners.” Like journalistic accounts, neither compared new gun ownership in 2020 with new gun ownership in earlier years. Like NICS data, neither presented demographic information about new gun owners. The first study, fielded in July 2020 (n = 2870), focused on concerns that California adults had about violent victimization during the pandemic. An incidental finding was that 10 adults reported that they had purchased a firearm “in response to the pandemic” and, of these, 4 had not owned a gun previously (4). The second study, a nationally representative survey (n = 1377) that used NORC's AmeriSpeak Panel and was fielded in mid-July 2020, estimated that 6% of U.S. adults had “bought one or more guns since the COVID-19 pandemic began in the U.S. in March 2020.” Of those purchasing a gun ( n = 77), 34% reported never having owned a firearm previously (95% CI, 22% to 48%) (5).

The primary purpose of this study was to estimate the number of U.S. adults who purchased firearms between January 2019 and April 2021, the number who became new gun owners as a result, the proportion of new gun owners who had been living in a gun-free household, and of these, how many other people they exposed to household guns. We also describe the demographic and firearm-related characteristics of recent purchasers, differentiating those who became new gun owners from those who did not, and juxtaposing these 2 groups with gun owners who had not recently purchased firearms and with gun owners as a whole.

Methods

Design and Sampling

Data were extracted from the 2021 National Firearms Survey, a probability-based online survey of U.S. adults conducted 15 April 2021 to 26 April 2021, and from a follow-up survey in May 2021 to ascertain whether 482 respondents in the April survey who had not been asked whether they were new gun owners, were, in fact, new gun owners. The survey was conducted by the research firm Ipsos, with respondents drawn from an online sampling frame (KnowledgePanel) comprised of approximately 55 000 U.S. adults recruited using address-based sampling methods.

The institutional review boards at Northeastern University and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health determined that the survey did not require review under federal regulations.

Measures

Respondents were invited to participate in a survey “about items you may have purchased over the past two years.” Once a respondent accepted the invitation, they were screened with questions about household gun ownership, with introductory text that specified that the survey was about working firearms. These were defined as any firearm that could be fired but explicitly excluded air guns, BB guns, starter pistols, and paintball guns. The gun ownership questions were “Do you personally own a working gun?” (yes/no) and “Does anyone ELSE in your household own a working gun?” (yes/no/don't know).

Timing of Firearm Purchases and Identifying New Gun Owners

All respondents who reported that they personally owned guns were asked whether they had purchased any firearms during each of the 5 periods: before 1 January 2016, 2016 to 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021.

To determine whether respondents who indicated that they had purchased firearms in 2019, 2020, or 2021 had become new gun owners as a result of their earliest purchase since January 2019, we asked respondents to enumerate in which of the 28 months since January 2019 they had purchased firearms and, for the earliest month, whether they had already owned firearms at that time: “AT THAT TIME did you already personally own any working guns?” To determine whether new gun owners were new to household firearm ownership, we asked them, with respect to their earliest purchase month, whether anyone else in their household owned firearms at that time: “AT THAT TIME did anyone else IN YOUR HOUSEHOLD own any working guns?”

An error in the survey skip pattern resulted in our not asking 482 respondents who had purchased firearms in calendar year 2019 about the months in 2019 they had purchased guns. This error affected approximately half (482 of 934) of the respondents who had purchased firearms in 2019. The 482 for whom we do not have monthly 2019 purchase data are those who had purchased firearms in 2019 and in 2020 and/or 2021. To ascertain whether these 482 recent purchasers were new gun owners at the time of their earliest purchase (in 2019), we invited all 482 to answer a short supplemental survey, fielded from 6 May 2021 to 16 May 2021. A total of 438 respondents accepted this invitation and were asked, “In the survey you filled out two weeks ago, you indicated that you had bought at least one working firearm in 2019. Thinking about the earliest date in 2019 when you bought a firearm, 1) AT THAT TIME did you already personally own any working guns? and 2) AT THAT TIME did anyone else IN YOUR HOUSEHOLD own any working guns?”

Number and Types of Firearms Purchased, 2020–2021

For all respondents, including the 482 mentioned earlier, we collected monthly purchase data for 2020 and 2021. Thus, for all respondents we know the number of people who purchased in each calendar year, whether they became new gun owners, and if so, whether they were also new to household firearm ownership. For all respondents we also determined the number and types of guns they purchased (see below). But we have complete monthly purchase data only for 2020 and 2021.

Respondents who reported having purchased firearms in 4 or fewer months during 2020 were asked separately for each month in which they had bought firearms how many handguns, rifles, and shotguns they had purchased and whether they had been subject to a background check at the time of that month's purchase. For those who reported having purchased firearms in more than 4 months in 2020, 4 purchase months were chosen at random.

Number and Types of Firearms Owned

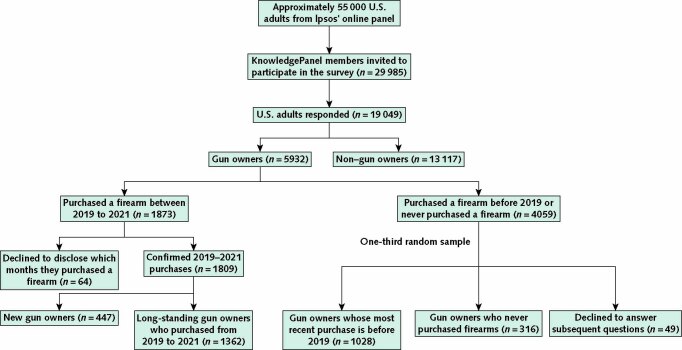

To reduce survey costs, we randomly sampled 1 of every 3 respondents who reported owning a firearm but not purchasing any guns from 2019 to 2021 (Figure 1). This one-third random sample plus all recent purchasers were asked questions about the firearms they owned, such as the number and types owned.

Figure 1. Summary of sample derivation steps.

Respondent demographics for all survey respondents (including non–gun owners) were provided by Ipsos using data elements collected by Ipsos annually, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, U.S. census region, household size, and the presence and number of children younger than 18 years in the household.

Weighting and Analysis

To calculate the number of firearms that were purchased from 2020 to April 2021, we summed the number of guns respondents reported having purchased each month, overall, and by gun type for the time specified. For the few respondents who reported having purchased guns in more than 4 months in 2020, the average number of guns purchased in the 4 months we assessed, overall and by gun type, was assigned to each of the remaining months the respondent reported having purchased firearms.

Extrapolations to the U.S. population used population data from the 2020 U.S. Census. Study-specific poststratification weights adjusted for nonresponse, under- or overcoverage from study-specific sampling, and benchmark demographic distributions (from the U.S. Census Current Population Survey or American Community Survey) so that descriptive statistics are representative of the U.S. adult population. All analyses were conducted using the statistical software Stata 16 (StataCorp).

Role of the Funding Source

Funding for this study was provided by the Joyce Foundation, which had no role in the design, conduct, and analysis of the study or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

Of the 29 985 KnowledgePanel members invited to participate in the survey, 19 701 started and 19 049 completed the survey, for a survey completion rate of 64%. Of these, 5932 personally owned firearms and 1933 had purchased firearms since 2019. Among gun owners who had purchased firearms since 2019, 447 became new gun owners (Figure 1). In the May follow-up survey, 438 of 482 eligible participants responded (89%).

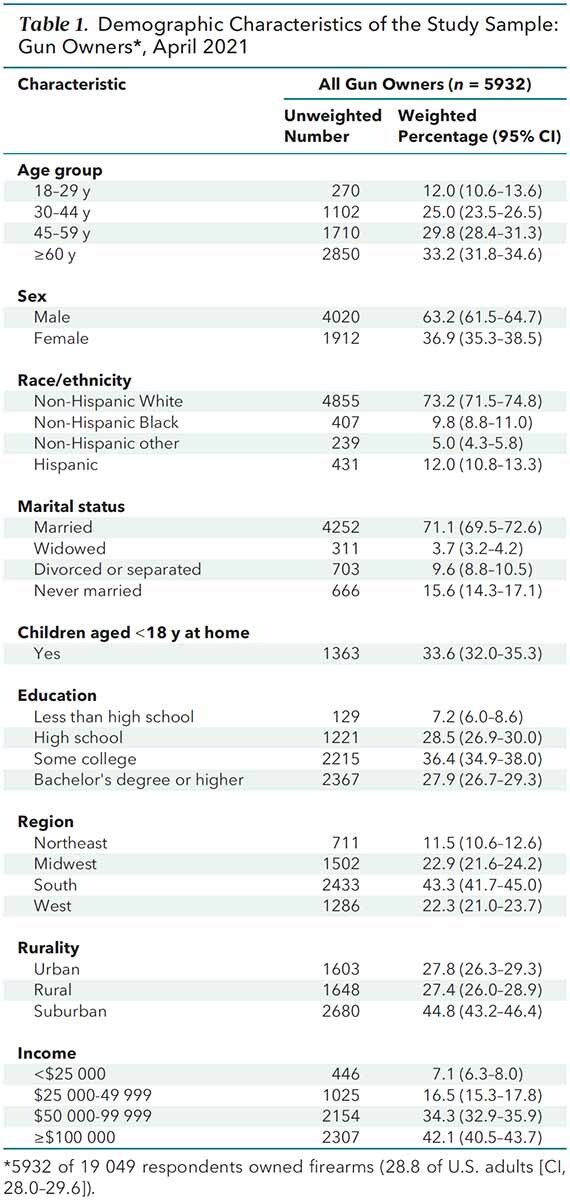

Demographic Characteristics of Study Sample (U.S. Gun Owners)

An estimated 28.8% of U.S. adults personally owned firearms (Table 1), representing approximately 75 million people. An additional 10.4% (CI, 9.8% to 11.0%) were estimated to live in households with firearms but did not personally own guns. Most firearm owners were male, White, and married and lived in a rural or suburban area (Table 1). One third lived in a household with children.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Sample: Gun Owners*, April 2021

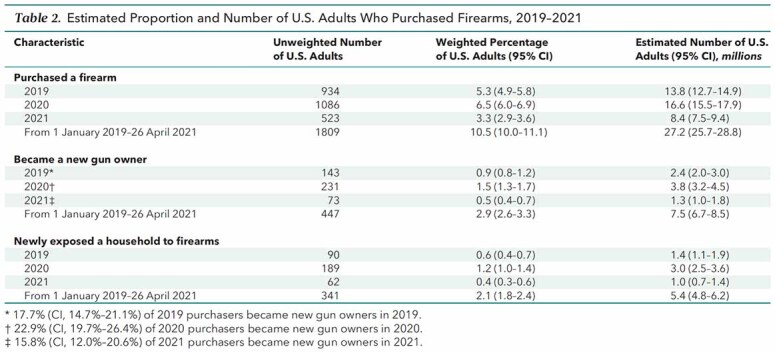

U.S. Adults Who Purchased Firearms, 2019–2021, by Year, Prior Ownership, and Whether They Newly Exposed Their Household to Firearms

We estimate that nearly 3 million more U.S. adults purchased firearms in 2020 (16.6 million) than in 2019 (13.8 million) (Table 2). As a result, even though the proportion of gun purchasers who were new to gun ownership in each of the 3 calendar years we examined hovered around 20%, without notable differences in this proportion prior to versus during the COVID-19 pandemic, the estimated absolute number of new gun owners increased. In 2019, for example, approximately 2.4 million U.S. adults became new gun owners (0.9% of U.S. adults); in 2020, 3.8 million did (1.5% of U.S. adults). Overall, an estimated 2.9% of U.S. adults (7.5 million people) became new gun owners over the 28 months before the survey, equal to 10% of all U.S. adults who personally owned firearms as of April 2021.

Table 2.

Estimated Proportion and Number of U.S. Adults Who Purchased Firearms, 2019–2021

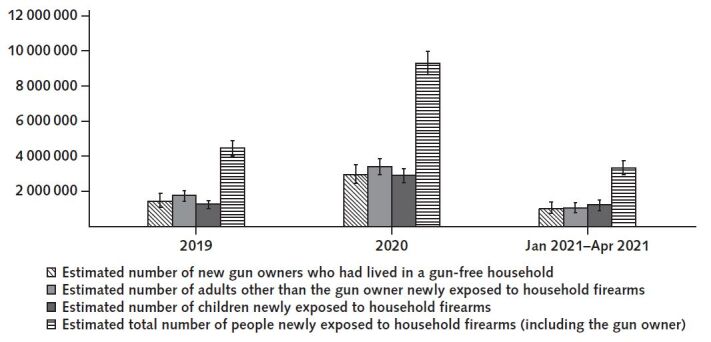

For each calendar year, we estimate that approximately two thirds to four fifths of new gun owners brought firearms into households without firearms (Table 2). Over the 28 months before the survey, an estimated 5.4 million U.S. adults brought firearms into households without guns (Table 2), newly exposing, on average, 2.2 other people to household firearms (1.0 children and 1.2 other adults, Figure 2). Figure 2 depicts the number of people newly exposed to household firearms, assuming static household composition since first purchase between 2019 and 2021. In 2020, for example, an estimated 9.3 million people were newly exposed to household firearms (3 million children and 6 million adults, including the gun owner). Over the 28 months, we estimate that approximately 17 million people were newly exposed to firearms in their home, including more than 5 million children.

Figure 2. Estimated number of persons newly exposed to household firearms, 2019, 2020, and January to April 2021.

The figure depicts the number of people newly exposed to household firearms, assuming a static household composition since first purchase between 2019 and 2021.

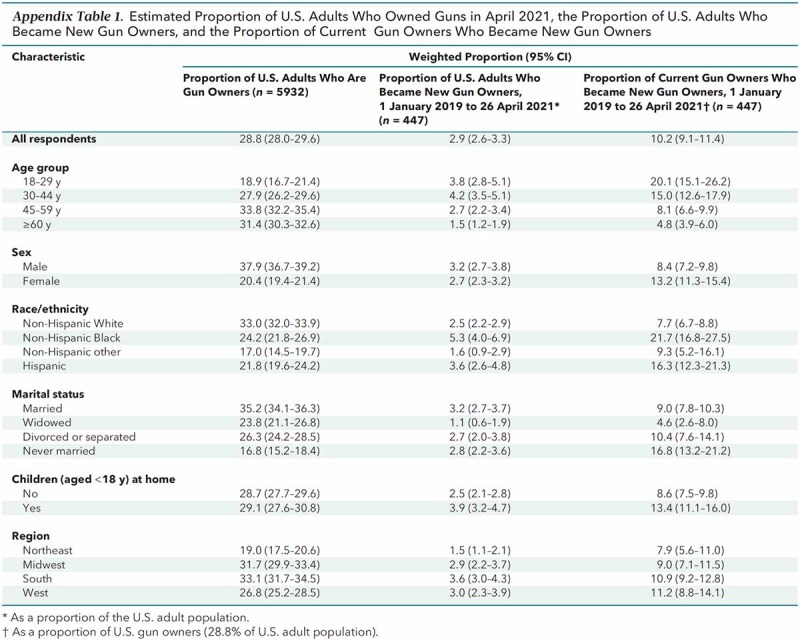

Appendix Table 1 presents summary estimates of firearm purchasing over the 28-month period before the survey. We estimate that approximately 3% of men and women became new gun owners over the 28 months assessed, as did 5% of Black U.S. adults, and 4% of U.S. adults living with children. By May 2021, an estimated 22% of Black gun owners and 16% of Hispanic gun owners had become new gun owners over the prior 28 months, as had 8% of non-Hispanic White gun owners, 8% of male gun owners, and 13% of female gun owners.

Appendix Table 1.

Estimated Proportion of U.S. Adults Who Owned Guns in April 2021, the Proportion of U.S. Adults Who Became New Gun Owners, and the Proportion of Current Gun Owners Who Became New Gun Owners

Characteristics of U.S. Gun Owners Overall and by Purchase History

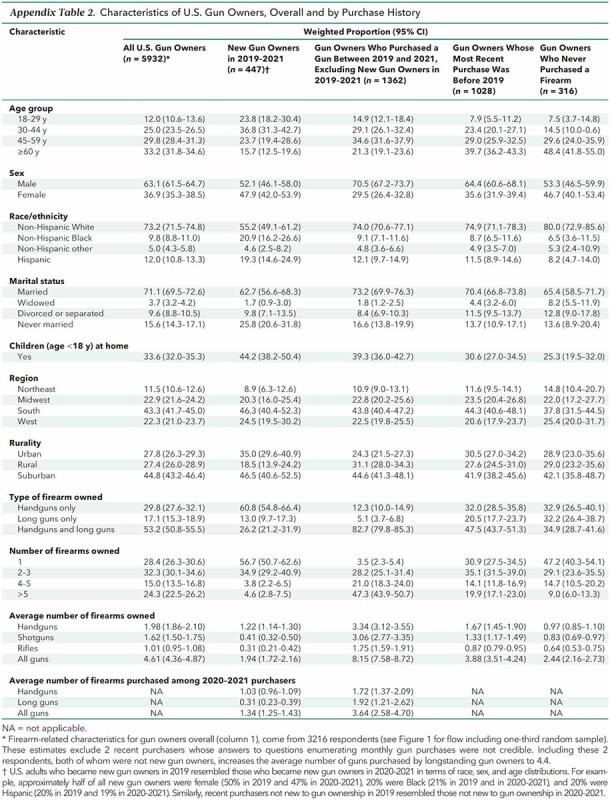

U.S. adults who became new gun owners in 2019 resembled those who became new gun owners in 2020–2021 in terms of race, sex, and age distributions; likewise, recent purchasers not new to gun ownership in 2019 resembled those in 2020–2021 (Appendix Table 2). For example, in 2019, as in 2020–2021, we estimate that approximately half of all new gun owners were female (50% in 2019 and 47% in 2020–2021), 20% were Black (21% in 2019 and in 2020–2021), and 20% were Hispanic (20% in 2019 and 19% in 2020–2021). To maximize recent purchaser subgroup size, we pooled estimates from 2019 to 2021 for new gun owners and, separately, for recent purchasers who are not new to gun ownership (Appendix Table 2).

Appendix Table 2.

Characteristics of U.S. Gun Owners, Overall and by Purchase History

We estimate that approximately 10% of gun owners as of May 2021 had become new gun owners over the prior 28 months. Slightly more than half of these new gun owners were male and non-Hispanic White; one fifth were Black and one fifth were Hispanic. One quarter were younger than 30 years. On average, new gun owners owned 1.9 firearms, 1.2 of which were handguns. In the 16 months before the survey, these purchasers bought on average 1.3 firearms, approximately three quarters of which were handguns.

We estimate that 27% of gun owners had recently purchased firearms but were not new to gun ownership, more than 70% of whom were male, were White, and lived in nonurban areas. On average they owned 8.2 guns, 3.3 of which were handguns. In the 16 months before the survey, these purchasers bought 3.6 firearms, approximately half of which (1.7 firearms) were handguns. Gun owners who purchased firearms before 2019, but not after, comprised nearly half of surveyed gun owners and were predominantly non-Hispanic White (75%) and male (64%). On average they owned 3.9 firearms, of which 1.7 were handguns. An estimated 15% of current gun owners had never purchased firearms; approximately half were female and four fifths were non-Hispanic White.

Overall, more than half of surveyed gun owners owned both handguns and long guns. Slightly less than one third owned 1 firearm, whereas half owned more than 3 firearms. On average, gun owners owned approximately 4.6 firearms, 2 of which were handguns. On the basis on these figures, we estimate that approximately 345 million firearms are in civilian hands (4.6 × 75 million).

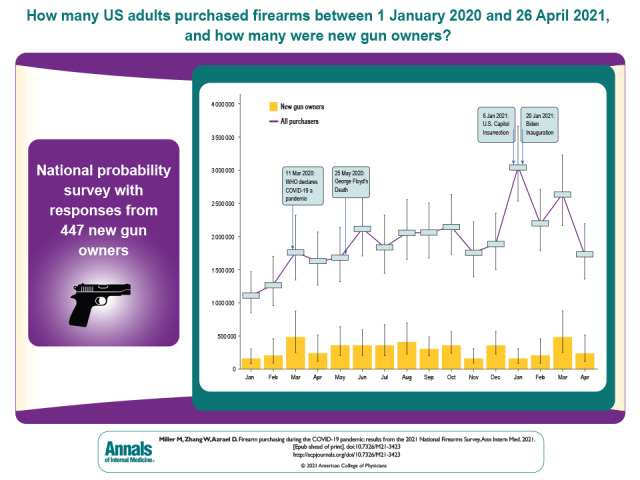

Estimates of the Number of U.S. Adults Purchasing Firearms Monthly, 1 January 2020 to 26 April 2021

On average, in a given month between January 2020 and April 2021, we estimate that approximately 1.9 million people bought firearms, 300 000 of whom were new to gun ownership when they purchased their gun. Figure 3 shows that the largest estimated increase in number of people who purchased firearms over the study period occurred in January 2021, the month in which the U.S. Capitol insurrection and President Biden's inauguration occurred. The next largest increase occurred in June 2020, the month after George Floyd's murder.

Figure 3. Estimates of the number of U.S. adults purchasing firearms per month, overall, and by those new to gun ownership, 1 January 2020 to 26 April 2021.

Discussion

Our survey suggests that the surge in NICS checks starting in early 2020, an increase superimposed on an upward trend apparent since 2005, was accompanied by a substantial increase in the number of U.S. adults who purchased firearms and the number of new gun owners created by those purchases, compared with 2019 statistics. The acceleration in firearm purchasing resulted from a general increase in the number of U.S. adults who bought guns, the great majority of whom in any given year already owned firearms. Nonetheless, the number of new gun owners created, 1 January 2019 to 26 April 2021, was sufficiently large (an estimated 7.5 million) and diverse (approximately half were female and almost half were people of color) to have a modest effect on the prevalence of firearm ownership and on the demographic profile of current gun owners. Overall, as of April 2021, approximately 10% of gun owners had become new gun owners over the previous 28 months, of whom an estimated 5.4 million (72%) brought their newly acquired firearms into gun-free homes, exposing an additional 11.7 million people, including more than 5 million children, to the risks of living in a household with firearms.

Our estimate of the number of new gun owners created in 2020 is substantially lower than was recently reported by the only other nationally representative survey to assess this statistic (5). For example, we found that 1.5% of U.S. adults became new gun owners in 2020 (approximately 3.8 million adults), an increase of 1.4 million compared with the 0.9% of U.S. adults who did so in 2019. These estimates accord well with the approximate 3% change in the percentage of U.S. adults who reported personally owning firearms in 2018 versus 2020 in the General Social Surveys from NORC (6). By contrast, the study by Crifasi and colleagues estimated that 6.5 million U.S. adults (3.2 million to 9.7 million) became new gun owners over a 4.5-month period; 3 times as many as we estimated (5). Chance alone cannot explain the 3-fold difference, nor is it accounted for by the particular 4.5 months they assessed (our direct estimate for March through July 2020 found that 1.8 million new gun owners were created; data not shown). One possibility is differential susceptibility to telescoping—reporting events that occurred outside a time frame as occurring in it. To minimize telescoping, we first asked respondents about a full range of years in which they might have purchased firearms and only subsequently about in which months (in the relevant year) they purchased. By contrast, Crifasi and colleagues asked respondents whether they bought any firearms over the past 4.5 months.

Despite the discrepancies between our and this previous study, both estimate that several million U.S. adults became new gun owners over the past few years. The only other reference point with which to compare current estimates is a national survey conducted in 2015 by Wertz and colleagues that found approximately 1 million adults became new gun owners annually between 2010 and 2015 (7). Our data suggest that 5 years later the annual number of adults who became new gun owners had quadrupled.

New gun owners in 2019 resembled new gun owners in 2020, suggesting that demographic shifts in new gun ownership preceded the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, to whatever extent the volume of firearm purchases may have been affected by events since March 2020 (see Figure 3), such as the civil unrest after George Floyd's murder in the spring of 2020 and the storming of the U.S. Capitol on 6 January 2021, by 2019, new gun owners were already considerably less likely to be White and male and were younger than other gun owners. New gun owners described by Wertz and colleagues in 2015 looked less like today's new gun owners and more like today's other recent purchasers (7).

Our findings should be interpreted with additional considerations in mind. First, although the probability-based sampling methods used in the current survey are designed to minimize sampling bias, sampling bias may nevertheless have affected our findings. Second, recall bias, specifically telescoping bias, may have affected respondents' retrospective assessment of when they purchased firearms. We attempted to minimize this distortion by asking respondents about the full range of years in which they purchased firearms and only subsequently about the months (in the relevant years) that they had purchased. Third, panel members who chose not to participate in our survey could have differed in important ways from participants. However, our survey completion rate (64%) is higher than those of typical nonprobability, opt-in, online surveys, which have completion rates of 2% to 16%; higher than that of previously published random-digit dial telephone surveys that included questions about firearm ownership; and similar to or higher than prior online probability-based surveys of firearm owners (8–13).

Deciding whether to own a gun involves balancing potential benefits and risks. On balance, when an adult brings firearms into his or her household, the risk for death from suicide, homicide, and unintentional firearm injury increases substantially, not only for the gun owner but also for all of the other people with whom the gun owner lives (14–22). As such, the health consequences of the recent surge in personal and household gun ownership will be borne not only by the U.S. adults who have recently become new gun owners but also by the millions of others who live with them, including an estimated 5 million children who have been newly exposed to household firearms since 2019.

Appendix: Detailed Survey Methods

Study Design

Ipsos (formerly GfK; www.gfk.com) was contracted by Northeastern University (principal investigator, M. Miller) to conduct the 2021 National Firearms Survey, which aimed to examine firearm ownership and purchasing over the 28 months before the survey in the United States. The survey was conducted in a sample from KnowledgePanel, an online research panel of more than 55 000 people who are representative of the entire U.S. population.

KnowledgePanel Details

Panel members are randomly recruited through probability-based sampling, and households are provided with access to the internet and hardware if needed. Ipsos recruits panel members by using address-based sampling methods. After initially accepting the invitation to join the panel, participants are asked to complete a short demographic survey (the initial profile survey), answers to which allow efficient panel sampling and weighting for future surveys. Completion of the profile survey allows participants to become panel members, and as in the past, all respondents are provided the same privacy terms and confidentiality protections.

Once household members are recruited for the panel and assigned to a study sample, they are notified by email for survey taking, or panelists can visit their online member page for survey taking (instead of being contacted by telephone or postal mail). To assist panel members with their survey taking, a personalized “home page” lists all of the surveys that were assigned to them and have yet to be completed.

Additional documentation regarding KnowledgePanel sampling, data collection procedures, weighting, and issues relating to institutional review board approval are available at www.ipsos.com/en-us/solutions/public-affairs/knowledgepanel and www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ipsosknowledgepanelmethodology.pdf.

Sampling

For this study, the target population comprised adults aged 18 years or older who were gun owners, with a particular focus on those who had purchased firearms since 2019. The survey had 2 stages consisting of an initial screening for gun ownership from a random sample of nearly 30 000 of the 55 000 KnowledgePanel members and a main survey of eligible panel members aged 18 years or older who were not currently serving on active duty in the U.S. Armed Forces.

Data Collection

Survey pretesting occurred in March 2021, with administration of the final survey in April 2021. Potentially eligible panel members received a notification e-mail letting them know that a new survey was available for them to take. This e-mail notification contained a link that sent them to the survey questionnaire. No login name or password was required. After 3 days, automatic e-mail reminders were sent to all nonresponding panel members in the sample. Specifically, participants were invited to take the survey via e-mail, with reminder e-mails sent to nonresponders on days 3, 6, 9, and 12. Ipsos has a modest point-based incentive program through which participants accrue points to redeem for cash, merchandise, or sweepstakes participation.

KnowledgePanel Sample Weighting

Ipsos structures recruitment for the KnowledgePanel with the goal of having the resulting panel represent the adult population of the United States with respect to a broad set of geodemographic distributions as well as particular subgroups of hard-to-reach adults (for example, those without a landline telephone or those who primarily speak Spanish). Consequently, the raw distribution of KnowledgePanel mirrors that of U.S. adults closely, except for occasional disparities that may emerge for certain subgroups owing to differential attrition rates among recruited panel members.

For selection of general population samples from KnowledgePanel, Ipsos uses an equal probability of selection method design by weighting the entire KnowledgePanel to benchmarks from the latest March supplement of the U.S. Census Current Population Survey (www.census.gov/cps/data/). The geodemographic dimensions used for weighting the entire KnowledgePanel typically include sex, age, race, ethnicity, education, census region, household income, home ownership status, metropolitan area, and internet access.

Using these weights as the measure of size for each panel member, a probability proportional-to-size procedure is used to select study-specific samples. Application of the proportional-to-size procedure method with the measure of size values produces fully self-weighting samples from KnowledgePanel, for which each sample member can carry a design weight of unity.

The geodemographic benchmarks used to weight the active panel members for computation of size measures include:

Gender (male, female)

Age (18 to 29, 30 to 44, 45to 59, ≥60 years)

Race/Hispanic ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic other, non-Hispanic ≥2 races, Hispanic)

Education (less than high school, high school, some college, Bachelor's degree or higher)

Census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West)

Household income (<$10 000, $10 000 to <$25 000, $25 000 to <$50 000, $50 000 to <$75 000, $75 000 to <$100 000, $100 000 to <$150 000, ≥$150 000)

Home ownership status (own, rent, other)

Metropolitan area (yes, no)

Hispanic origin (Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, other, non-Hispanic)

Study-Specific Poststratification Weights

Once all survey data have been collected and processed, design weights are adjusted to account for any differential nonresponse that may have occurred. For this purpose, an iterative proportional fitting (raking) procedure is used to produce the final weights. In the final step, calculated weights are examined to identify and, if necessary, trim outliers at the extreme upper and lower tails of the weight distribution. The resulting weights are then scaled to aggregate to the total sample size of all eligible respondents.

For this study, the weighting process included the following steps:

Step 1: Design weights for all KnowledgePanel assignees were computed to reflect their selection probabilities.

Step 2: The above design weights for KnowledgePanel respondents—before any screening—were raked to the following geodemographic distributions of the population aged 18 years or older. The needed benchmarks were obtained from the 2019 American Community Survey (ACS), except for metropolitan status within census region, which is not available from the 1-year ACS and was obtained from the 2020 March Supplement of the Current Population Survey (CPS).

Gender (male, female) by age (18 to 29, 30 to 44, 45 to 59, 60 to 69, ≥70 years)

Race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic other, non-Hispanic ≥2 races, Hispanic)

Census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West) by metropolitan status (metropolitan, nonmetropolitan)

Education (less than high school, high school, some college, Bachelor's degree or higher)

Household income (<$25 000, $25 000 to $49 999, $50 000 to $74 999, $75 000 to $99 999, $100 000 to $149 999, ≥$150 000)

Household size (1, 2, 3, ≥4)

Presence of children aged 0 to 17 years (yes, no)

The resulting weights were trimmed and scaled to sum to the unweighted sample size of the following groups:

Total screened respondents (19 049 cases).

Total gun owners (5932 cases).

Total recent purchasing gun owners (1806 cases).

Step 3: The screener weights were used to develop benchmarks based on all gun owners.

Step 4: Gun owners who purchased guns in 2019–2021 plus a random sample of one third of gun owners who did not (3217 cases) carried over their screener weights as the starting weights and were raked to the following geodemographic distributions of all owners with finer adjustments within gun owners who have and have not purchased a working gun since 2019.

Gender (male, female) by age (18 to 29, 30 to 44, 45 to 59, 60 to 69, ≥70 years) by gun owner (have purchased gun since 2019, have not purchased gun since 2019)

Race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic other, non-Hispanic ≥2 races, Hispanic) by gun owner (have purchased gun since 2019, have not purchased gun since 2019)

Census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West) by metropolitan status (metropolitan, nonmetropolitan) by gun owner (have purchased gun since 2019, have not purchased gun since 2019)

Education (less than high school, high school, some college, Bachelor's degree or higher) by gun owner (have purchased gun since 2019, have not purchased gun since 2019)

Household income (<$25 000, $25 000 to $49 999, $50 000 to $74 999, $75 000 to $99 999, $100 000 to $149 999, ≥$150 000) by gun owner (have purchased gun since 2019, have not purchased gun since 2019)

Household size (1, 2, 3, ≥4) by gun owner (have purchased gun since 2019, have not purchased gun since 2019)

Presence of children aged 0 to 17 years (yes, no) by gun owner (have purchased gun since 2019, have not purchased gun since 2019)

The resulting weights were trimmed and scaled to add up to the unweighted sample size of section 2-gun owner respondents. These final weights were labeled as weight 4 with 3217 cases.

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 21 December 2021.

References

- 1.NICS Firearm Checks: Month/Year. Federal Bureau of Investigation; 2021. Accessed at www.fbi.gov/file-repository/nics_firearm_checks_-_month_year.pdf/view on 30 November 2021.

- 2. Fisher M, Green M, Glass K, Eger A. ‘Fear on top of fear’: why antigun Americans joined the wave of new gun owners. The Washington Post. 10 July 2021. Accessed at www.washingtonpost.com/nation/interactive/2021/anti-gun-gun-owners/ on 30 November 2021.

- 3. Curcuruto J. Millions of First-Time Gun Buyers During COVID-19. National Shooting Sports Foundation: National Shooting Sports Foundation; 2020. Accessed at www.nssf.org/articles/millions-of-first-time-gun-buyers-during-COVID-19/ on 30 November 2021.

- 4. Kravitz-Wirtz N , Aubel A , Schleimer J , et al. Public concern about violence, firearms, and the COVID-19 pandemic in California. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2033484. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crifasi CK , Ward JA , McGinty EE , et al. Gun purchasing behaviours during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, March to mid-July 2020. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2021:1-5. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1080/09540261.2021.1901669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smith TW, Davern M, Freese J, et al. General Social Surveys, 1972-2018 [machine-readable data file]. Chicago: NORC at the University of Chicago; 2018. Accessed at gssdataexplorer.norc.org on 30 November 2021.

- 7. Wertz J , Azrael D , Hemenway D , et al. Differences between new and long-standing US gun owners: results from a national survey. Am J Public Health. 2018;108:871-877. [PMID: ] doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Callegaro M, DiSogra C. Computing response metrics for online panels. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2009;72:1008-32. doi:10.1093/poq/nfn065

- 9.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Second Injury Control and Risk Survey (ICARIS-2) [Computer File]. OMB Number 200-1996-00599. Atlanta, GA. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/icaris2-publicuse-dataset-documentation.doc at XXX.

- 10. Betz ME , Barber C , Miller M . Suicidal behavior and firearm access: results from the second injury control and risk survey. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2011;41:384-91. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00036.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller M , Hepburn L , Azrael D . Firearm acquisition without background checks: results of a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:233-239. [PMID: ] doi: 10.7326/M16-1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Conner A , Azrael D , Miller M . Firearm safety discussions between clinicians and U.S. adults living in households with firearms: results from a 2019 national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:725-728. [PMID: ] doi: 10.7326/M20-6314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hepburn L , Miller M , Azrael D , et al. The US gun stock: results from the 2004 National Firearms Survey. Inj Prev. 2007;13:15-9. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Studdert DM , Zhang Y , Swanson SA , et al. Handgun ownership and suicide in California. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2220-2229. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1916744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wiebe DJ . Firearms in US homes as a risk factor for unintentional gunshot fatality. Accid Anal Prev. 2003;35:711-6. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miller M , Barber C , White RA , et al. Firearms and suicide in the United States: is risk independent of underlying suicidal behavior. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:946-55. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kellermann AL , Rivara FP , Somes G , et al. Suicide in the home in relation to gun ownership. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:467-72. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Anglemyer A , Horvath T , Rutherford G . The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:101-10. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cummings P , Koepsell TD , Grossman DC , et al. The association between the purchase of a handgun and homicide or suicide. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:974-8. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brent DA , Perper JA , Moritz G , et al. Firearms and adolescent suicide. A community case-control study. Am J Dis Child. 1993;147:1066-71. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miller M , Swanson SA , Azrael D . Are we missing something pertinent? A bias analysis of unmeasured confounding in the firearm-suicide literature. Epidemiol Rev. 2016;38:62-9. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxv011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Swanson SA , Eyllon M , Sheu YH , et al. Firearm access and adolescent suicide risk: toward a clearer understanding of effect size. Inj Prev. 2020. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]