Abstract

Stimulus-responsive supramolecular organogels have been broadly studied, but the assembly of a liquid crystalline organogel with a thermoreversible response remains a challenge. This could be attributed to the difficulty of designing organogelators with liquid crystalline properties. Nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) has been utilized to produce a diversity of pentafluorobenzene-containing aromatics, which are very regioselective to para positions. Those pentafluorobenzene-functionalized aromatics have been ideal compounds for the preparation of calamitic liquid crystals. In this context, novel fluoroterphenyl-containing main-chain polyether (FTP@PE) was synthesized using in situ SNAr polymerization as a convenient and effective synthetic strategy toward the development of fluorescent liquid crystals bearing fluoroterphenyl and ether groups. The fluoroterphenyl unit was synthesized by Cu(I)-supported decarboxylation cross-coupling of potassium pentafluorobenzoate and 1,4-diiodobenzene. The chemical structures of FTP@PE were studied with 1H/13C/19F nuclear magnetic resonance and infrared spectra. The liquid crystal mesophases were determined with differential scanning calorimetry and polarizing optical microscopy. Ultraviolet–visible absorbance and emission spectral profiles showed solvatochromic activity. The nanofibrous morphologies were studied with a scanning electron microscope. The organogels of FTP@PE were developed in a number of solvents via van der Waals attraction forces of aliphatic moieties and π stacking of fluoroterphenyl groups. They demonstrated thermoreversible responsiveness.

1. Introduction

Stimulus-responsive supramolecular organogels are attractive materials with an ability to interact with one or more external triggers, such as heat, light, and solvent polarity.1−3 Among those external stimuli, light is an attractive trigger as it is can be localized in space and exactly adjusted without direct contact.4−6 Organofluorinated materials have been employed for a diversity of products, such as pesticides, reagents for catalysis, surfactants, water-repellent commodities, refrigerants, liquid crystal displays, and pharmaceuticals. With a low friction coefficient, liquid-based fluorinated polymers have been employed as lubricants. Nafion is the polymer form of triflic acid, which is a solid-state acid that has been employed as a membrane in low-temperature fuel cells.7−9 The inclusion of fluorine atoms in mesogenic compounds can stimulate special features compared to nonfluorinated terphenyls. These special properties can be ascribed to the higher size of fluorine relative to hydrogen leading to a remarkable steric hinderance.10 For example, fluorine-substituted liquid crystalline compounds typically exhibit a wide collection of nematic mesogenic phases distinguished with low conductivity, poor rotational viscosity, and high dielectric anisotropic activity. Those improved properties provide a novel generation of liquid crystalline compounds for a variety of applications, such as active antiferroelectric, surface-stabilized ferroelectric, and twisted nematic liquid crystalline electronic displays.11 High-birefringence nematic liquid crystalline compounds were reported recently from fluorinated terphenyls demonstrating a gradual decrement in the birefringence with the increase of fluorine atoms on the phenyl cycle.12 Perfluorinated aryls are distinguished with high reactivity toward cross-coupling reactions. Recently, the synthesis of perfluoroaryls was reported via Cu(I)-supported decarboxylation cross-coupling of fluorobenzoates with aromatic iodides. This synthetic strategy is characterized with less sensitive catalytic compounds, only CO2 generated as a byproduct, low cost, and high selectivity.13,14 Therefore, it can be applied to replace former traditional, costly, and highly sensitive organopalladium catalytic compounds.15 Extensive research was reported on the use of organopalladium catalysis in cross-coupling chemistry for the synthesis of fluoroaryls. However, it still suffers disadvantages, such as low selectivity, side reactions, low yield, and substantial quantities of byproducts leading to extra purification cost.13−15 SNAr is a vital synthesis method in which a nucleophilic substance substitutes a good departing group, such as fluorine, located on an aryl ring. SNAr of fluorine by different nucleophiles has been investigated for aryl moieties substituted with electron-deficient moieties, such as polyhalogens and sulfonyl, cyano, and nitro groups.16−18 Those electron-deficient groups facilitate faster SNAr providing higher yields. SNAr typically occurs in aprotic solvents, like dimethylformamide, hexametapol, and dimethylacetamide. SNAr typically occurs under the temperature range of 0–100 °C depending on the energy required to activate the aryl moiety.19,20

Fluorination has been applied onto a variety of organic compounds to provide liquid crystals with improved physical properties.21,22 Nonetheless, the utilizations of SNAr for the synthesis of fluorine-substituted aromatics have been mostly overlooked as an efficient strategy for the synthesis of fluorine-substituted mesogenic compounds. Organogels are attractive materials due to their thermal reversibility, chemical sensitivity, and diversity of their micro(nano) supramolecular assembled scaffolds. Thus, they have been applied to manufacturing various commodities, such as pharmaceuticals, sensors, foodstuffs, and cosmetics.23−25 Only, very limited studies were reported on the development of fluorinated gelators. Surprisingly, no studies were reported on the preparation of perfluorinated terphenyl-containing fluorescent polyethers despite their important role in a diversity of recent optoelectronic advances. Herein, we report the synthesis of novel fluorescent liquid crystalline polymer organogels composed of a rigid fluoroterphenyl connected to flexible aliphatic chains via an ether bond. Cu-assisted decarboxylative cross-coupling was applied between potassium pentafluorobenzoate and 1,4-diiodobenzene. Regioselective SNAr was applied as an efficient synthetic strategy to provide fluorine-substituted terphenyls in excellent yields polymerized via ether bonds with different aliphatic diols. These consequent synthetic tactics were meant to reduce side reactions and cost and increase the purity of the produced liquid crystals. The produced polyethers and related intermediates were studied by 1H/13C/19F NMR and infrared spectra. Different aliphatic diols were also employed to identify the length of the aliphatic chain for better liquid crystalline properties. The developed polymeric liquid crystals displayed fluorescence in the ultraviolet spectrum range. Smart materials are identified as materials, like liquid crystalline polymers, with a characteristic color and fluorescence variations upon exposure to a certain stimulus. Hence, the current liquid crystalline fluorescent polymers can be applied as proper materials for less energy consumption display. This is highly valuable for portable displays.26,27 Moreover, the prepared polyethers showed solvatochromic properties. The gelation properties of the prepared polyethers were tested in some organic solvents demonstrating the formation of intertwined fibrous textures with the ability to immobilize solvents. The supramolecular self-assembly of the prepared polyethers via van der Waals attraction forces of the aliphatic units and π stacks of fluoroterphenyls to provide nanofibers was studied by SEM. In this context, there are various potential applications that can be proposed for this new generation of polyether organogels, such as thermoresponsive robust actuators, electro-optical devices, drug release systems, and self-healing organogels.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

Materials and solvents (spectroscopic grade) were purchased from Frontier Scientific, Fluka, and Merck (Egypt). Silica-gel based TLC was employed to monitor the progress of reactions. The intermediate 1 was synthesized according to a previous method28 from potassium pentafluorobenzoate and 1,4-diiodobenzene (Merck, Egypt).

2.2. Methods

Melting points and liquid crystalline phases were reported on a DSC 2920 (TA Instruments). A Bruker Vectra 33 was employed to study the infrared spectra. NMR spectra were explored by a BRUKER AVANCE 400. To inspect the mesophases of the newly synthesized polyethers, an OLYMPUS POM (BX51) was employed in association with a SPOT CCD camera (USA), ITO unaligned cells with a thickness of 3.9 μm, and a Mettler hot stage (FP-82-HT) connected to a temperature control system (FP-90) with a cooling rate of 2 °C/min. UV–vis absorption spectra were studied by an HP-8453, whereas fluorescence spectral profiles and quantum yields (Φ) were studied on a VARIAN CARY ECLIPSE. Rhodamine 6G (Φr = 0.95) and Rhodamine 101 (Φr = 0.96) solutions in absolute ethanol were used as quantum yield reference standards. SEM images of the produced organogel in n-pentanol were studied on a Hitachi S2600N. The organogel was cast on a glass substrate and dried under ambient conditions to afford a xerogel, which was subjected to annealing overnight at 45 °C and coated with a thin film of gold (∼10 nm). The molecular weight of the prepared polyether PE1 was evaluated by gel permeation chromatography (GPC, Hewlett Packard 1100) using chloroform as a mobile phase and polystyrene as a standard.

2.3. Gelation Study

The formation of organogels was performed by dissolving the synthesized polyethers (PE1–PE4) in different solvents under heating toward the boiling point. The produced solutions were left to cool and settle down to generate organogels in 15–35 min depending on the concentration of the organogelator. The reversibility between the sol and the gel was investigated by heating the reverted vial containing the gel. The temperature at which the organogel first collapsed was reported as the organogel melting temperature. This procedure was repeated for a number of cycles to confirm strong reversibility.

2.4. Synthetic Strategies

2.4.1. Synthesis of 2,2″,3,3″,4,4″,5,5″,6,6″-Decafluoro-1,1′:4′,1″-terphenyl (1)

An admixture of 1,4-diiodobenzene (1.65 g, 5 mmol), potassium pentafluorobenzoate (5.5 g, 21.85 mmol), and a solvent (bis(2-methoxyethyl) ether; 25 mL) was exposed to heating at 100 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere. CuI (193 mg, 1 mmol) was added to the reaction system, which was subjected to reflux at 140 °C. Following completion of the reaction, the solvent was removed by a rotary evaporator. The remaining residue was subjected to heating in iso-octane containing traces of silica gel/montmorillonite. After filtration under vacuum, the solid was subjected to crystallization from iso-octane to provide a white crystalline solid (0.635 g, 31%); mp 113–115 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 7.61 (s, 4 H); 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 145.48, 142.98, 141.98, 139.21, 139.32, 136.68, 130.52, 127.52; 19F NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): −142.92 (q, 4 F), −154.39 (t, 2 F), – 161.59 (m, 4 F); IR (cm–1): 3010, 2977, 2924, 1731.

2.4.2. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Polyethers (PE1, PE2, PE3, and PE4)

The above prepared 2,2″,3,3″,4,4″,5,5″,6,6″-decafluoro-1,1′:4′,1″-terphenyl was dissolved in anhydrous dimethylformamide and then subjected to heating to achieve complete dissolution under a nitrogen atmosphere. The diol was added, and then, 2 equiv of tBuOK was added. Following reaction completion, dimethylformamide was isolated by rotary evaporation, and the produced residue was subjected to washing with diethyl ether (5 × 10 mL) for purification. The product was dried overnight at 50 °C.

2.4.3. Synthesis of 1,5-Pentanediol-Based Polyether (PE1)

This polyether was composed of 4,4″-dipentyloxy-(2,2″,3,3″,5,5″,6,6″-octafluoro)-1,1′:4′,1″-terphenyl as a monomer. PE1 was synthesized from compound 1 (200 mg, 0.5 mmol), dimethylformamide (15 mL), 1,5-pentanediol (5 mL), and tBuOK (0.1125, 1 mmol); yield of 81%; mp 202–203 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): 7.58 (s, 4 H), 4.39 (q, 4 H), 1.82 (m, 2 H), 1.70 (m, 2 H), 1.55 (m, 2H); 19F NMR (400 MHz,DMSO-d6, TMS): −145.10 (q, 4 F), −157.18 (q, 4 F); IR (cm–1): 2989, 2941, 1476, 979.

2.4.4. Synthesis of 1,8-Octanediol-Based Polyether (PE2)

This polyether was composed of 4,4″-dioctyloxy-(2,2″,3,3″,5,5″,6,6″-octafluoro)-1,1′:4′,1″-terphenyl as a monomer. PE2 was synthesized from compound 1 (200 mg, 0.5 mmol), dimethylformamide (15 mL), 1,8-octanediol (5 mL), and tBuOK (0.1125, 1 mmol); yield of 75%; mp 192 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): 7.57 (s, 4 H), 4.28 (q, 4 H), 1.88 (m, 2 H), 1.74 (m, 8 H), 1.50 (m, 2H); 19F NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): −145.20 (q, 4 F), −157.25 (q, 4 F); IR (cm–1): 2925, 2877, 1476, 980.

2.4.5. Synthesis of 1,12-Dodecanediol-Based Polyether (PE3)

This polyether was composed of 4,4″-didodecyloxy-(2,2″,3,3″,5,5″,6,6″-octafluoro)-1,1′:4′,1″-terphenyls as a monomer. PE3 was synthesized from compound 1 (200 mg, 0.5 mmol), dimethylformamide (15 mL), 1,12-dodecanediol (5 mL), and tBuOK (0.1125, 1 mmol); yield of 67%; mp 137 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): 7.53 (s, 4 H), 4.31 (q, 4 H), 1.82 (m, 14 H), 1.73 (m, 4 H), 1.55 (m, 2H); 19F NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): −145.18 (q, 4 F), −157.20 (q, 4 F); IR (cm–1): 2931, 2872, 1482, 973.

2.4.6. Synthesis of 1,16-Hexadecanediol-Based Polyether (PE4)

This polyether was composed of 4,4″-didodecyloxy-(2,2″,3,3″,5,5″,6,6″-octafluoro)-1,1′:4′,1″-terphenyls as a monomer. PE4 was synthesized from compound 1 (200 mg, 0.5 mmol), dimethylformamide (15 mL), 1,16-hexadecanediol (5 mL), and tBuOK (0.1125, 1 mmol); yield of 62%; mp 117 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): 7.50 (s, 4 H), 4.31 (d, 4 H), 1.86 (m, 22 H) 1.53 (m, 4 H), 1.37 (m, 2 H); 19F NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): −145.18 (q, 4 F), −157.19 (q, 4 F); IR (cm–1): 2915, 2849, 1481, 975.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and Chemistry

Commercially available 1,4-diiodobenzene was utilized as a starting compound in the preparation of targeted polyethers. The synthetic procedure of symmetrical para-terphenyl with two terminal fluoroaryl rings polymerized with different aliphatic diols of different chain lengths is illustrated in Scheme 1. Copper(I)-assisted decarboxylation cross-coupling was employed to introduce fluorine-substituted terphenyls in high yields from pentafluorobenzoate and 1,4-diiodobenzene utilizing diglyme as a solvent. Bis(2-methoxyethyl) ether (diglyme) can generate a coordinative bond with potassium cations to facilitate the complex formation between Cu(I) cations and pentafluorobenzoate ions. This is a very efficient reaction providing high-quality yields.29 It has been known that the higher number of fluorines on a phenyl ring results in increasing the reactivity of this aryl moiety toward decarboxylative cross-coupling reactions. On the other hand, decreasing the number of fluorine atoms results in lower reactivity, which requires solvent replacement and extra catalysis, such as dimethyl acetamide as a solvent and Cu(I)/phenanthroline as a catalytic mixture.30 The application of SNAr on those activated perfluorinated aryls and alcoholates demonstrated an improved performance under mild conditions.31 Perfluorinated aryls are robust commercial chemicals. The insertion of alkoxy terminal chains to perfluorinated aryl rings was tested by SNAr. The application of SNAr on the terminal perfluorinated aryl rings was monitored to be highly para-specific. Hence, it has been idealistic for the synthesis of rod-like (calamitic) molecular structures. The synthesized perfluorinated symmetrical para-terphenyl was exposed to in situ SNAr polymerization with a range of alcoholates of different chain lengths utilizing tBuOK as a catalyst and anhydrous dimethylformamide as a solvent. The reactivity of fluorines at the para active sites of the terminal perfluorinated phenyl rings makes them good leaving groups in SNAr. This could be ascribed to the high number of activating fluorines at meta/ortho sites of the terminal phenyl rings. Therefore, a higher regioselective SNAr can be accomplished only at the para active sites of the external phenyls by replacing the para-fluorine atoms to provide perfluoroaryls polymerized with aliphatic diols. The chemical structures of the prepared polyethers were verified with 1H/13C/19F NMR and infrared spectroscopy. The polymer yields were monitored to decrease with increasing the alkyl diol length as PE1, PE2, PE3, and PE4 exhibited yields of 81, 75, 67, and 62%, respectively. Similarly, the polymers’ relatively high melting points were monitored to decrease with increasing the alkyl diol length. The FT-IR spectra of the developed polyethers were almost similar as no differences were detected with increasing the alkyl chain length. The stretching vibrations of both aromatic and aliphatic groups were monitored at 2931 and 2872 cm–1, respectively. The 19F NMR spectra proved the presence of fluorine in the polymer structure demonstrating the quartet signals around −145 (4F) and −157 (4F) ppm assigned to the terminal fluorinated aromatic rings. The 1H NMR spectra also proved the polymer structures indicating the presence of a singlet signal around ∼7.5 ppm assigned to the nonfluorinated central aromatic 4H.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Polyethers Comprising Symmetrical Perfluorinated para-Terphenyl as a Rigid Unit and Aliphatic Diol as a Flexible Alkoxy Unita.

m is the number of carbon atoms in the aliphatic diol [m = 5 (PE1), 8 (PE2), 12 (PE3), or 16 (PE4)] and is the number of monomer units.

The molecular weight of PE1 was monitored to increase as a function of time. The most fitting molecular weight was obtained at 4300 g/mol after a period of 45 min. The average molecular weight (Mw) of PE1 was also studied by GPC and controlled in the range of 2700–4300 by adjusting the reaction time in the range of 30–45 min as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1. Mw of PE1 as a Function of Time.

| time (min) | MW (×103) |

|---|---|

| 15 | 1.6 |

| 30 | 2.7 |

| 45 | 4.3 |

| 60 | 6.2 |

| 75 | 10.1 |

3.2. Photophysical Properties

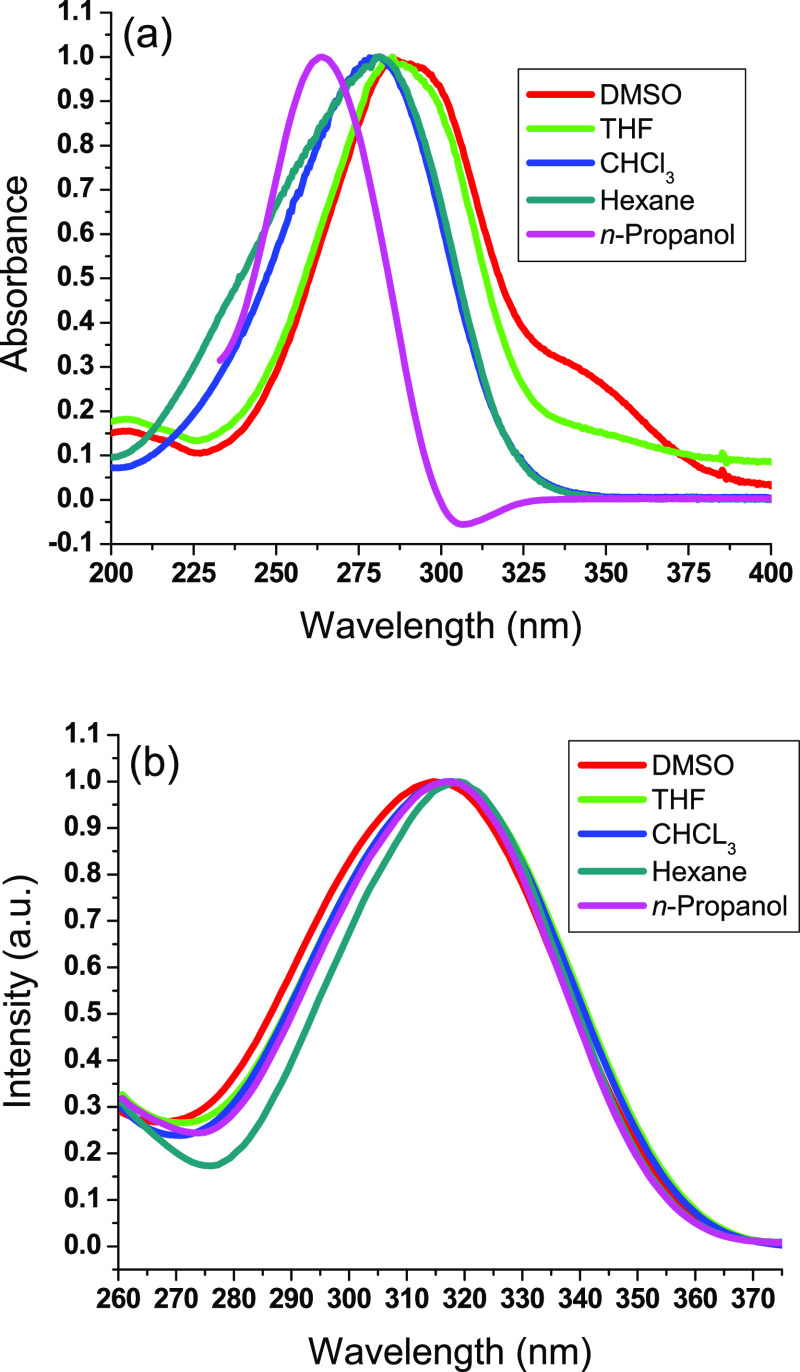

Stimulus-responsive optical polymers can be employed to produce smart commodities able to change their absorbance and/or emissive spectra due to external stimuli.2,32−38 Ultraviolet–visible absorption, fluorescence spectral curves, and quantum yields (Φ) were studied in various solvents as illustrated in Figure 1 and Table 2. The prepared polyethers were observed to absorb in the ultraviolet range due to the π–π* transition. The length of the aliphatic chain was found to influence the optical performance of the developed polyethers. The prepared polyethers with aliphatic diols of higher chain length showed an absorbance wavelength higher than those of lower chain length. Thus, a bathochromic shift was monitored in the absorbance wavelength with increasing the aliphatic length. Similarly, a bathochromic shift was monitored in the emission wavelength with increasing the aliphatic chain length. This could be ascribed to the decreased excited state of polyethers with increasing the aliphatic chain length. Thus, the aliphatic diols of higher chain length possessed strong ICT and a relaxation conformation. The higher emission wavelength of polyethers with aliphatic diols of higher chain length could be attributed to the higher dissolution ability driven by the increased aliphatic chain. On the other hand, the current polyethers comprise perfluorinated para-terphenyls with a higher emission wavelength compared to the corresponding nonfluorinated terphenyls. This can be ascribed to the twisting nature of the fluorine-substituted phenyls, which require a lower energy for the excitation state. This twisting activity was driven by the fluorine atoms at the bay positions between the core phenyl ring and the terminal perfluorinated phenyl rings. On the other hand, the planar nature of the more stable nonfluorinated para-terphenyls requires a higher energy for the excitation state. Thus, the fluorine substitution was monitored to considerably enhance the intramolecular charge transfer (ICT).29 The prepared polyethers composed of an electron-withdrawing fluoroaryl conjugate core moiety bonded to electron-donating terminal aliphatic groups. The electron-withdrawing effect of the fluoroaryl conjugate core was improved with the multiple fluorine substitution on the phenyl rings. Hence, ICT is susceptible to demonstrating solvatochromism and solvatofluorochromism properties. The absorption and fluorescence maxima were found to increase with increasing the polar activity of solvents to designate positive solvatochromism. Hence, the ground state possessed a lesser polar activity compared to the excitation one; thus, the perfluoroaryl constituent in the developed polyethers can be highly stabilized by a highly polar solvent. As shown in Table 2, the synthesized polyethers demonstrated relatively high quantum yields. However, those quantum yields were monitored to decrease with increasing the alkyl chain length, which could be attributed to the high solvation of the generated polyethers with increasing the alkyl chain length.

Figure 1.

Normalized absorbance (a) and fluorescence (b) spectral curves of PE3.

Table 2. Absorption (abs) and Fluorescence (fl) Maximum Wavelengths (nm) as well as Quantum Yields (Φ) of Polyethers.

| hexane |

propanol |

THF |

DMSO |

CHCl3 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| polyether | abs | fl (Φ) | abs | fl (Φ) | abs | fl (Φ) | abs | fl (Φ) | abs | fl (Φ) |

| PE1 | 274 | 310 (0.30) | 260 | 307 (0.58) | 280 | 312 (0.37) | 278 | 305 (0.61) | 271 | 306 (0.35) |

| PE2 | 277 | 312 (0.22) | 264 | 311 (0.50) | 281 | 315 (0.31) | 281 | 315 (0.55) | 274 | 312 (26) |

| PE3 | 280 | 319 (0.19) | 263 | 317 (0.44) | 285 | 317 (0.24) | 286 | 314 (0.45) | 281 | 318 (0.17) |

| PE4 | 284 | 322 (0.10) | 265 | 324 (0.38) | 286 | 321 (0.16) | 288 | 319 (0.32) | 286 | 324 (0.11) |

3.3. Mesogenic Phases

Hydrogen can be replaced with fluorine on a variety of aromatic moieties to show mesogenic phases without too much steric interferences. The high electronegativity of fluorine imparts the carbon–fluorine bond a higher dipole moment compared to that of a carbon–hydrogen bond.29 The mesogenic phases were studied by DSC and POM. Changing the length of the aliphatic diol chain was recognized as a major factor in changing the liquid crystalline mesogenic phases. The prepared fluorinated polyethers showed an interesting liquid crystalline behavior. Figure 2 shows DSC thermograms of PE1 and PE2. Upon heating, PE1 showed crystal phases at 94, 96, and 125 °C. Upon subsequent cooling, PE1 showed isotropic to the first mesogenic phase at 122 °C and another mesogenic phase at 77 °C. Upon heating, PE2 showed crystal phases at 108 and 125 °C. Upon subsequent cooling, PE2 showed isotropic to the first mesogenic phase at 123 and 124 °C and another mesogenic phase at 92 °C.

Figure 2.

DSC thermograms of PE1 (a) and PE2 (b) demonstrating the temperatures of the transition phases.

Upon cooling, the optical textures of PE2 explored by POM showed an isotropic mesophase (Iso)39 and schlieren textures with strong directing fluctuation ideal of a nematic (N) mesophase monitored at 108 °C. This confirmed a phase transition of Iso–N.40 The textures then switched to homeotropic and stayed within the nematic mesophase (Figure 3). PE4 displayed a smectic mesophase with a regular bâtonnet separated out from the isotropic mesophase at 125 °C demonstrating a mesophase transition of Iso–SmA. Beneath the mesophase transition, the bâtonnet was more coalescing forming focal-cone fan textures. As shown in Table 3, a number of mesophases were monitored, including smectic A and nematic phases.

Figure 3.

Optical textures (total magnification of 200×) of PE1 demonstrating a nematic phase (a) and PE2 demonstrating a smectic phase (b).

Table 3. Fluorinated Polyethers with Different Lengths of Aliphatic-Chain Diol Demonstrating Different Mesogenic Phases.

| polyether | diol | phase transition (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| PE1 | 1,5-pentanediol | Iso 122 N 77 Cr |

| PE2 | 1,8-octanediol | Iso 123 SmA 93 Cr |

| PE3 | 1,12-dodecanediol | |

| PE4 | 1,16-hexadecanediol |

3.4. Gelation Study

Nanofibrous bundles were formed by self-assembly of alkoxy-substituted perfluorinated para-terphenyl as a major repetitive unit of the produced polyethers. The synthesized polyethers consisted of two main units. The first unit consisted of a rigid perfluorinated para-terphenyl, whereas the second unit was composed of flexible aliphatic chains of different lengths. Both units are connected by an ether bond formed via an in situ SNAr polymerization reaction. The polymer chain exhibited ether aliphatic groups separated by perfluorinated para-terphenyl. The rigid fluoroaryl moiety was liable for π–π stacking, whereas the flexible alkyl moiety was liable for van der Waals attraction forces. Regarding the self-assembly of the polymer gelators, macromolecular aggregations were generated from the dissolution of the prepared polyethers introducing three-dimensional nanofibrous networks. These nanofibrous entanglements can be controlled by the opposed parameters monitored by dissolution and crystal formation. The developed polyethers, PE2, PE3, and PE4, demonstrated a high solubility in various solvents only upon heating to high temperatures. On the other hand, PE1 showed a very poor solubility in various organic solvents. Thus, it can be concluded that the solubility of the produced polyethers was established to improve with the increase in the aliphatic chain length. By dissolving the polyether gelator under mild heating and then cooling back to ambient temperature, an organogel was produced as illustrated in Figure 4. The gel formation was evaluated in various solvents. The critical gel concentrations (CGC) for PE3 in various solvents were detected in the range of 1.48–6.02 mM. PE3 showed strong gelation of various solvents, such as dimethylsulfoxide (1.81 mM), n-octanol (2.15 mM), n-pentanol (1.48 mM), and acetonitrile (6.02 mM). However, PE3 exhibited partial gelation in acetone, toluene, n-propanol, and tetrahydrofuran. Moreover, it exhibited no gelation in chloroform, ethanol, benzene, and dichloromethane due to its poor solubility in those solvents. The gelation studies of the prepared polyethers are summarized in Table 4. Generally, the produced organogels demonstrated a colorless appearance. The sol–gel switching process was monitored to be completely thermally reversible with high efficiency. The generated gels of the developed polyethers showed photophysical spectra comparable to those in diluted solutions. Moreover, the gels generated from PE3 in n-pentanol, n-octanol, and dimethylsulfoxide showed high stability extended for a few weeks. On the other side, the gel produced from PE3 in CH3CN was stable for some days.

Figure 4.

Thermal reversibility of the fluorescent gel PE3 in n-pentanol.

Table 4. Formation of Gels from the Produced Fluorinated Polyethers in Various Solventsa.

| solvent | PE2 | PE3 | PE4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ethylacetate | sol | sol | sol |

| chloroform | Ppt | Ppt | Ppt |

| dichloromethane | Ppt | Ppt | Ppt |

| toluene | Ppt | PG | PG |

| benzene | Ppt | Ppt | Ppt |

| tetrahydrofuran | Ppt | PG | PG |

| dimethylsulfoxide | PG | gel (1.81 mM) | sol |

| ethanol | Ppt | Ppt | Ppt |

| n-propanol | Ppt | PG | sol |

| n-pentanol | PG | gel (1.46 mM) | sol |

| n-octanol | PG | gel (2.15 mM) | gel (4.79 mM) |

| acetonitrile | Ppt | gel (5.28 mM) | PG |

| acetone | Ppt | PG | PG |

Ppt: precipitate; PG: partial gel; CGC (mM) inserted between parentheses.

The increase in the aliphatic chain length was found to improve the ability of the gel formation. However, the 1,12-dodecyloxy-based polyether PE3 showed a better ability of gel formation than the 1,12-hexadecyloxy-based polyether PE4. This can be attributed to the higher dissolution of PE4 in various solvents. This high solubility of PE4 was driven by the longer hexadecyloxy moiety. The sort of self-assembly was determined by emission spectra to indicate H-aggregates that was verified by a hypsochromic shift of the fluorescence maxima upon switching from a gel (313 nm) to a sol (317 nm) of PE3 in n-pentanol as depicted in Figure 5. In the assembly of H-aggregates, each macromolecule interacts with the adjacent macromolecules via van der Waals interactions of aliphatic chains and π stacks of fluoroaryls to indicate macromolecular propensity to two-dimensional nanofibrous aggregation.41

Figure 5.

Normalized emission spectral profiles of PE3 in gel and solution phases (2.44 × 10–5 mol/L) in n-pentanol.

3.5. Morphological Study

The morphological study of the solid xerogel produced from the organogel of PE3 in n-pentanol was investigated with SEM to demonstrate three-dimensional strong and porous nanofibrous entanglements with diameters of 150–350 nm as illustrated in Figure 6. The assembly of PE3 displayed nanofiber-like bundles showing a good capability to gelate solvents. The existence of aliphatic groups of higher length can be reported as a significant factor increasing the stability of the self-assembled nanofibers. Furthermore, the inclusion of fluorines on the phenyl cyclic moiety could stimulate and enhance the stability of the developed supramolecular architectures.

Figure 6.

SEM images of the xerogel produced from the organogel of PE3 in n-pentanol.

3.6. Thermal Properties

The thermal stability was explored by studying the gel melting temperature of PE3 as illustrated in Figure 7. The organogel melting point was found to increase from 44 to 59 °C with increasing the polymer concentration in the range of 1.46–7.45 mmol L–1. The thermal stability was monitored to increase due to increasing the number of the polymer macromolecules in the nanofibrous medium. However, the organogel melting point was observed to decrease with further increasing the polymer ratio > 7.45 mM. This increment in the gel-to-sol melting temperature can be ascribed to the expanded nanofiber aggregates resulting in higher flexibility and better fibrous entanglements leading to a higher transition temperature.

Figure 7.

Gel-to-sol melting point versus concentration of the polymer gelator for PE3 in n-pentanol.

To inspect the thermal reversibility of PE3, the polymer solution was subjected to boiling (∼140 °C for n-pentanol) until reaching a transparent fluid. The produced fluid was then left to cool to generate the corresponding gel as verified by the “stable to inversion” approach. The generated gel was then heated again to monitor the temperature at which the gel collapses. The above procedure was carried out for several cycles to designate no changes in the gel⃗sol melting point proving high reversibility without deformation (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Temperature-dependent reversibility of PE3.

4. Conclusions

New fluorescent fluorinated polyethers comprising aliphatic diols of different chain lengths were synthesized via in situ SNAr polymerization with symmetrical perfluorinated terphenyls. Both gelation properties and mesogenic phases of the prepared polyethers were investigated. The symmetrically fluorinated para-terphenyl unit was synthesized by Cu(I)-assisted decarboxylative cross-coupling of potassium pentafluorobenzoate with 1,4-diiodobenzene. A suitable synthetic method of fluorinated polymers comprising ether bonds was presented in excellent yields employing SNAr. The chemical formulae of the prepared polyethers were verified with 1H/13C/19F NMR and infrared spectroscopy. Both absorption and fluorescence properties showed solvatochromic and solvatofluorochromic activities. Relatively high quantum yields were monitored to improve with increasing the aliphatic chain length. Van der Waals attraction forces of aliphatic moieties as well as π stacks of conjugated perfluoroaryls showed the capability to create fiber-like assemblies (150–350 nm) as verified by SEM images. The prepared fluorinated polyethers exhibited different mesophases as determined by the optical textures taken by POM microscopy. The temperature transitions of the developed mesophases monitored by POM were found to corroborate well with DSC. The current strategy opens a way for the development of main-chain liquid crystalline polymer organogels for a variety of promising applications, such as electro-optical devices, self-healing organogels, drug release systems, and thermoresponsive robust actuators.

Acknowledgments

The Taif University Researchers Supporting Project (number TURSP-2020/23), Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia is acknowledged.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

All relevant data are within the manuscript and available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- Abdelrahman M. S.; Khattab T. A.; Kamel S. Hydrazone-Based Supramolecular Organogel for Selective Chromogenic Detection of Organophosphorus Nerve Agent Mimic. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6, 2002–2009. 10.1002/slct.202004850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.; Zhang Q.; Li X.; Serpe M. J. Stimuli-responsive polymers for sensing and actuation. Mater. Horiz. 2019, 6, 1774–1793. 10.1039/C9MH00490D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khattab T. A. Synthesis and Self-assembly of Novels-Tetrazine-based Gelator. Helv. Chim. Acta 2018, 101, e1800009 10.1002/hlca.201800009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Lv M.-Z.; Song N.; Liu Z.-J.; Wang C.; Yang Y.-W. Dual-stimuli-responsive fluorescent supramolecular polymer based on a diselenium-bridged pillar [5] arene dimer and an AIE-active tetraphenylethylene guest. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 5759–5766. 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b01010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abumelha H. M.; Hameed A.; Alkhamis K. M.; Alkabli J.; Aljuhani E.; Shah R.; El-Metwaly N. M. Development of Mechanically Reliable and Transparent Photochromic Film Using Solution Blowing Spinning Technology for Anti-Counterfeiting Applications. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 27315–27324. 10.1021/acsomega.1c04127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhameed M. M.; Attia Y. A.; Abdelrahman M. S.; Khattab T. A. Photochromic and fluorescent ink using photoluminescent strontium aluminate pigment and screen printing towards anticounterfeiting documents. Luminescence 2021, 36, 865–874. 10.1002/bio.3987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.; Chen X.; Chen C.; Hu J.; Zhou C.; Cai X.; Wang W.; Zheng C.; Zhang P.; Cheng J.; Guo Z.; Liu H. Durably antibacterial and bacterially antiadhesive cotton fabrics coated by cationic fluorinated polymers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 6124–6136. 10.1021/acsami.7b16235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso V.; Correia D.; Ribeiro C.; Fernandes M.; Lanceros-Méndez S. Fluorinated polymers as smart materials for advanced biomedical applications. Polymer 2018, 10, 161. 10.3390/polym10020161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouharras F. E.; Raihane M.; Ameduri B. Recent progress on core-shell structured BaTiO3@ polymer/fluorinated polymers nanocomposites for high energy storage: Synthesis, dielectric properties and applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2020, 113, 100670. 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2020.100670. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saccone M.; Spengler M.; Pfletscher M.; Kuntze K.; Virkki M.; Wölper C.; Gehrke R.; Jansen G.; Metrangolo P.; Priimagi A.; Giese M. Photoresponsive halogen-bonded liquid crystals: the role of aromatic fluorine substitution. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 462–470. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b04197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Cao H.; Chen M.; Zhang L.; Jiang T.; Chen H.; Li F.; Zhu S.; Yang H. Effects of the fluorinated liquid crystal molecules on the electro-optical properties of polymer dispersed liquid crystal films. Liq. Cryst. 2017, 44, 2301–2310. 10.1080/02678292.2017.1376715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada S.; Hashishita S.; Asai T.; Ishihara T.; Konno T. Design, synthesis and evaluation of new fluorinated liquid crystals bearing a CF 2 CF 2 fragment with negative dielectric anisotropy. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 1495–1509. 10.1039/C6OB02431A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao S.-y.; Li L.-X.; Dong D.-Q.; Wang Z.-L.; Yu X.-Y. Synthesis of coumarins derivatives via decarboxylative cross-coupling of coumarin-3-carboxylic acid with benzylic C (sp3)-H bond. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 4073–4075. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2018.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. T.; Hase H.; Taylor S.; Salzmann I.; Forgione P. Approaching the Integer-Charge Transfer Regime in Molecularly Doped Oligothiophenes by Efficient Decarboxylative Cross-Coupling. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 7146–7153. 10.1002/anie.201914458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy D.; Uozumi Y. Recent Advances in Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions at ppm to ppb Molar Catalyst Loadings. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 602–625. 10.1002/adsc.201700810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kikushima K.; Grellier M.; Ohashi M.; Ogoshi S. Transition-Metal-Free Catalytic Hydrodefluorination of Polyfluoroarenes by Concerted Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution with a Hydrosilicate. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 16191–16196. 10.1002/anie.201708003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park N. H.; dos Passos Gomes G.; Fevre M.; Jones G. O.; Alabugin I. V.; Hedrick J. L. Organocatalyzed synthesis of fluorinated poly (aryl thioethers). Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–7. 10.1038/s41467-017-00186-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuita D.; Guberman-Pfeffer M. J.; Brückner C. SNAr Reaction toward the Synthesis of Fluorinated Quinolino [2, 3, 4-at] porphyrins. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 2021, 318–323. 10.1002/ejoc.202001347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mallick S.; Xu P.; Würthwein E.-U.; Studer A. Silyldefluorination of fluoroarenes by concerted nucleophilic aromatic substitution. Am. Ethnol. 2019, 131, 289–293. 10.1002/ange.201808646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistritto V. A.; Schutzbach-Horton M. E.; Nicewicz D. A. Nucleophilic aromatic substitution of unactivated fluoroarenes enabled by organic photoredox catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 17187–17194. 10.1021/jacs.0c09296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed H. A.; Hagar M.; Alhaddad O. A. Mesomorphic and geometrical orientation study of the relative position of fluorine atom in some thermotropic liquid crystal systems. Liq. Cryst. 2020, 47, 404–413. 10.1080/02678292.2019.1655809. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alaasar M.; Prehm M.; Poppe S.; Tschierske C. Development of Polar Order by Liquid-Crystal Self-Assembly of Weakly Bent Molecules. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 5541–5556. 10.1002/chem.201606035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito C. L.; Kirilov P.; Gaëlle Roullin V. Organogels, promising drug delivery systems: an update of state-of-the-art and recent applications. J. Controlled Release 2018, 271, 1–20. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staicu T.; Iliş M.; Cîrcu V.; Micutz M. Influence of hydrocarbon moieties of partially fluorinated N-benzoyl thiourea compounds on their gelation properties. A detailed rheological study of complex viscoelastic behavior of decanol/N-benzoyl thiourea mixtures. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 255, 297–312. 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.01.162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Debnath S.; Kaushal S.; Mandal S.; Ojha U. Solvent processable and recyclable covalent adaptable organogels based on dynamic trans-esterification chemistry: separation of toluene from azeotropic mixtures. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 1471–1480. 10.1039/C9PY01807G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R. K.; Sudhakar A. A. Perylene-based liquid crystals as materials for organic electronics applications. Langmuir 2018, 35, 2455–2479. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b01081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X.; Zhang C.; Shi L.; Zhang Q.; Zhu H. Highly stretchable, recyclable, notch-insensitive, and conductive polyacrylonitrile-derived organogel. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 0346–20353. 10.1039/D0TA08168J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altoom N. G. Synthesis and characterization of novel fluoroterphenyls: self-assembly of low-molecular-weight fluorescent organogel. Luminescence 2021, 36, 1285–1299. 10.1002/bio.4055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q.; Wu A.; Qin S.; Zeng M.; Le Z.; Yan Z.; Zhang H. Ni-Catalyzed Decarboxylative Cross-Coupling of Potassium Polyfluorobenzoates with Unactivated Phenol and Phenylmethanol Derivatives. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 3239–3244. 10.1002/adsc.201800729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour M.; Giacovazzi R.; Ouali A.; Taillefer M.; Jutand A. Activation of aryl halides by Cu 0/1, 10-phenanthroline: Cu 0 as precursor of Cu I catalyst in cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Commun. 2008, 45, 6051–6053. 10.1039/B814364A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTiernan C. D.; Leblanc X.; Scaiano J. C. Heterogeneous titania-photoredox/nickel dual catalysis: decarboxylative cross-coupling of carboxylic acids with aryl iodides. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 2171–2175. 10.1021/acscatal.6b03687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verkoyen P.; Frey H. Amino-functional polyethers: versatile, stimuli-responsive polymers. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 3940–3950. 10.1039/D0PY00466A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Wang L.; Yu H.; Khan R. U.; Haroon M. Ferrocene-based redox-responsive polymer gels: Synthesis, structures and applications. J. Organomet. Chem. 2017, 828, 38–51. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2016.10.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.-U.; Vandenbrande J.; Goetz A. E.; Ganter M. A.; Storti D. W.; Boydston A. J. Room temperature extrusion 3D printing of polyether ether ketone using a stimuli-responsive binder. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 28, 430–438. 10.1016/j.addma.2019.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khattab T. A.; El-Naggar M. E.; Abdelrahman M. S.; Aldalbahi A.; Hatshan M. R. Simple Development of Novel Reversible Colorimetric Thermometer Using Urea Organogel Embedded with Thermochromic Hydrazone Chromophore. Chemosensors 2020, 8, 132. 10.3390/chemosensors8040132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed H.; Khattab T. A.; Mashaly H. M.; El-Halwagy A. A.; Rehan M. Plasma activation toward multi-stimuli responsive cotton fabric via in situ development of polyaniline derivatives and silver nanoparticles. Cellulose 2020, 27, 2913–2926. 10.1007/s10570-020-02980-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H.; Kabb C. P.; Sims M. B.; Sumerlin B. S. Architecture-transformable polymers: Reshaping the future of stimuli-responsive polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2019, 89, 61–75. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2018.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nour H. F.; El Malah T.; Khattab T. A.; Olson M. A. Template-assisted hydrogelation of a dynamic covalent polyviologen-based supramolecular architecture via donor-acceptor interactions. Mater. Today Chem. 2020, 17, 100289. 10.1016/j.mtchem.2020.100289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dierking I.Textures of liquid crystals; John Wiley & Sons, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. Ed., Liquid crystals and biological structures; Elsevier, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Khattab T. A.; Tiu B. D. B.; Adas S.; Bunge S. D.; Advincula R. C. pH triggered smart organogel from DCDHF-Hydrazone molecular switch. Dyes Pigm. 2016, 130, 327–336. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2016.03.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]