Abstract

Few community-based behavioral health clinicians are trained in evidence-based practices (EBPs). The Cascading Model (CM), a training model in which expert-trained clinicians train others at their agency, may help increase the number of EBP-trained clinicians. This study is one of the first to describe CM training methods and to examine differences between clinicians trained by an expert, and those trained through a within agency training (WAT) by a fellow clinician. Results indicate that 56% of the 38 eligible clinicians chose to become trainers and 50% of the 56% conducted WATs to train others. This represents a 50% increase in EBP-trained clinicians within the study timeframe. Clinicians trained by an expert reported higher knowledge and training satisfaction than those trained through a WAT. Of note, clinicians trained through a WAT reported increases in EBP knowledge and were more diverse (race/ethnicity, employment status), suggesting that the CM may improve access to EBPs.

Keywords: evidence-based practice, implementation, training methods, cascading model

Introduction

The field of implementation science, which focuses on studying methods to promote the uptake and integration of evidence-based practices (EBPs) into routine care, emerged amid calls to increase consumer access to effective behavioral health treatment.1–3 Implementation barriers are complex and exist across individual-, organizational-, and system-levels.4 Clinician training is one such barrier that has been identified by stakeholder groups as both considerable and modifiable,5 marking it as an important point of intervention to facilitate implementation efforts.

Though training alone is not sufficient to promote successful EBP implementation,6–8 it is a crucial factor in the early adoption5 and long-term sustainability9 of EBPs. As such, there have been efforts to better understand specific components of effective training methods to produce the most favorable training outcomes. Research on traditional didactic strategies that are common in EBP training (e.g., workshops, review of written materials)6,10 has shown that these strategies increase clinician knowledge and improve clinician attitudes toward EBPs; however, no consistent changes in clinician behavior or client outcomes have been noted.11,12 Subsequent research has indicated that the addition of ongoing support (i.e., expert consultation) following the initial training period fosters changes in clinician behavior8,10 and improved client outcomes.13 This body of research has yielded recommendations that EBP trainings include components that encourage active participation as well as some form of ongoing support.10,14,15

Identifying specific training components and strategies that produce the best outcomes is an important first step in developing a competent and effective behavioral health workforce. Unfortunately, barriers exist to conducting effective trainings that are interactive and include ongoing support. The primary barrier is that the provision of such trainings is both costly and time consuming.16,17 This is further compounded by the current shortage of behavioral health clinicians in general,18,19 as well as a shortage of qualified trainers and consultants.20,21 Given these barriers, it is important to develop and test innovative strategies for effectively training clinicians in EBPs.

Cascading model

One training method with the potential to address some of the barriers noted above is the Cascading Model (CM),22 which has also been referred to as the train-the-trainer model23 or pyramidal training.24 In a CM training, experts train an initial cohort of clinicians, referred to as Generation 1 (G1), in a specific EBP. These G1 clinicians also receive additional training on how to train other clinicians (referred to as Generation 2 [G2]) in the EBP and are then able to provide training to others within their organization. Throughout this paper, trainings provided by G1 clinicians to G2 clinicians are referred to as within-agency training (WAT), as they are conducted within one specific agency by a trainer-clinician from that agency, rather than by an external expert trainer.

Although CM training requires more initial training for G1 clinicians compared with traditional training methods, this model is theorized to provide several benefits to promote successful implementation and sustainability of a new EBP.25 For example, training provided by an in-house (G1) trainer may be more cost effective over the long term than the cost associated with repeated use of an external expert trainer. Not only can this aspect of the CM help to alleviate the aforementioned shortage of qualified trainers,20,21 but it is also particularly advantageous in addressing the turnover of trained staff26 by providing an in-house system through which new hires can be trained in as part of their on-boarding process. Further, an in-house trainer provides expertise and knowledge of the local system, which can help foster an organizational climate and structure that will sustain the practice.

Given these theorized benefits, CM trainings have been used for a variety of populations. For instance, participants in a group-based body image program facilitated by CM-trained undergraduate peer leaders showed significant reductions in risk factors associated with eating disorders.27 Similarly, clients treated by CM-trained clinicians in the Veterans Administration showed reductions in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder symptoms equivalent to clients treated by expert-trained clinicians.28 Additionally, a review of 14 papers that examined CM trainings for clinicians working with individuals with intellectual disabilities noted considerable variability in the description of training provided across the papers, but did report consistent improvement in client behavior.24 Specifically, all five papers that examined client outcomes reported reduced problem behaviors (e.g., spitting, aggression) and increased adaptive behaviors (e.g., pedestrian safety, hair brushing).24 Although results are promising, few studies both provide a thorough description of training content/activities, and assess a variety of key outcomes.

One recent example29 did include a thorough description of training preparation and activities for a CM focusing on EBPs for a variety of common childhood mental and behavioral health concerns. In contrast to earlier studies that focused on client outcomes, outcomes included in this study focused primarily on training effectiveness and characteristics of trainings and trainers that have been shown to influence training effectiveness.29 Results largely supported the effectiveness of the CM for increasing the number of local clinicians trained in EBPs.29 With its focus on trainee perceptions and training effectiveness, this study marks an important development in the types of outcomes included in literature on the CM, which warrant additional consideration.

Outcome types

The provision of training in an EBP is complex as it involves teaching new information and skills to clinicians with the goal of changing not only their own behavior, but also the behavior of their clients. As such, research on training often includes both clinician-level training outcomes such as change in knowledge and skills,30 and client-level outcomes such as symptom improvement. A more thorough understanding of clinician-level outcomes would allow for a stronger evaluation of the CM, as clinician behavior is essential to understanding whether changes in client outcomes are attributable to the treatment that was delivered, or to other factors such as social learning or previous clinical experience.

While clinician knowledge and skill are critical training outcomes to assess across various training models, there are some training outcomes unique to the CM. Specifically, training equivalence (i.e., do G1 led trainings include the same content and process as expert-led trainings)31 and training maintenance (i.e., is the G1 clinician able to continuing delivering WATs)31 are particularly important within the CM, as they provide data to understand the extent to which the CM is sustainable. WAT that is not performed to the standard of expert-led training may suggest that there is insufficient capacity to sustain, or it may indicate that the CM is an inadequate training approach for that specific intervention or service setting. Alternatively, evidence that WAT is consistent with expert-led training may support the overall effectiveness and value of the CM. In either case, the study of WAT can provide insights into how the model may be adapted to optimize future implementation initiatives.

Current study

The goal of the current study was to address this gap in the training literature by closely examining the CM in the context of a statewide implementation of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT),32 an evidence-based behavioral parent training program. Although the CM has been endorsed as the preferred training method by PCIT International,33 an organization designed to function as an interface between PCIT research and practice, no published study to date has empirically examined clinician-level training outcomes of the CM for PCIT. At the time of this study, training guidelines published by PCIT International provided substantial flexibility regarding the portion of training designed to teach G1 clinicians how to conduct their own WAT. As a result of this flexibility, in conjunction with the aforementioned lack of published detail regarding essential components of CM trainings, the CM within the current study was operationalized using a thorough process that included expert informant interviews34 and a thorough review of the adult learning literature.6 The current study seeks to improve present understanding of CM trainings by pursuing three primary objectives: (a) describe content covered and procedures used by G1 clinicians in conducting WAT to understand training equivalence; (b) understand barriers to conducting WAT; and (c) compare G1 and G2 clinicians on key training outcomes, including PCIT knowledge, PCIT use, and training satisfaction.

Methods

Recruitment

Participants were recruited as part of a larger implementation trial (NIMH R01 MH095750, PI: Herschell). A study protocol has been published which describes all recruitment and enrollment procedures in detail.25 Recruitment efforts targeted all eligible licensed outpatient community behavioral health clinics across Pennsylvania. Eligible clinics had to: (a) treat young children; (b) have no prior PCIT training experience; (c) be capable of covering site preparation costs; (d) be willing to participate in PCIT training; and (e) agree to participate in research. Each eligible clinic selected one administrator, one supervisor, and two clinicians, who were contacted by research staff to hear a description of study procedures and provide informed consent. Eligible clinicians had to: (a) hold a master’s or doctorate degree; (b) be licensed or license-eligible in his/her field; (c) have a caseload of families appropriate for PCIT; (d) have no previous PCIT training; and (e) be willing to complete study tasks (e.g., video-recording sessions, study assessments).

Procedures

PCIT model.

All participants were trained in PCIT, which is a manualized EBP for children 2.5- to 7-years-old with disruptive behavior disorders32,35 and/or a history of child maltreatment.36 PCIT is a highly-structured treatment in which caregivers receive in vivo coaching by a therapist through an earpiece while they interact with their child. PCIT includes two phases: Child-Directed Interaction, which focuses on strengthening the caregiver-child relationship, and Parent-Directed Interaction, which targets reducing child noncompliance through effective discipline strategies.

Training conditions.

The larger implementation trial included three different training conditions (i.e., Cascading Model, Distance Education, and Learning Collaborative). Clinics were randomized to one training condition at the county-level and were balanced on population size and poverty level. Trainings were conducted in four waves across Pennsylvania from 2012–2015. Incentives to encourage study participation and retention included a $1000 stipend to cover PCIT equipment costs and PCIT training at no cost for participating clinics. In addition to free training, clinicians were also able to receive continuing education units and payment for completion of study measures. Study procedures were approved by the [REDACTED FOR BLIND REVIEW] Institutional Review Board. Given the aim of the current study, the remainder of this paper focuses exclusively on the CM condition of the larger trial.

Cascading model.

Care was taken to ensure that CM procedures in this study were consistent with the most recent PCIT International guidelines at the time of study development37 and PCIT Master Trainer standards.34,38 The initial didactic portion of the CM training consisted of seven training days (54 training hours) during which trainees learned the PCIT model and practiced PCIT skills. This portion was broken down into an initial five-day expert-led workshop, followed by a two-day advanced training six months later. Trainers led 24 bi-weekly 1-hour consultation calls with trainees after the initial didactic training had been completed. All training activities and consultation calls were led by certified PCIT trainers with expertise in disruptive behavior disorders. Training fidelity checklists were completed by independent observers either present at or conducting a video review of each training to monitor consistency across training waves.

Following initial training and consultation, interested participants could elect to complete a second round of training focused on preparing them to train others in PCIT. Again, efforts were taken to ensure that this additional training component was consistent with PCIT International guidelines. At the time of study development, the current PCIT International guidelines37 focused more on the content that should be covered, with less specific guidance pertaining to training processes or formats that should be used. As such, expert interviews provided additional details on the most common training methods and content emphasized by individual PCIT Master Trainers.34 Based on this information and a thorough review of the adult learning literature,39 this additional training consisted of a 3-hour web course which covered the following topics: an overview of training expectations; strategies for identifying individuals to train; use of a didactic vs. co-therapy model; managing trainee-trainer relationships; conducting/documenting mastery checkouts; providing feedback for skill development; supervision tools and activities; use of coach coding tools; and program growth and sustainability. Given the flexibility in PCIT International training guidelines, participants were informed about both didactic and co-therapy models for delivering WAT. However, emphasis was placed on the use of a co-therapy model as it is more consistent with the active training methods shown to produce the greatest change in therapist skill.10,14,15 Upon completion of the web course, participants could conduct WAT with interested clinicians, and were supported with an additional six months of consultation (one call per month). Video review of supervision sessions also was offered to WAT trainers to support their efforts in conducting WAT. In sum, the portion of training designed to prepare clinicians to delivery WAT involved 3 hours of web-based training, 6 hours of consultation calls, and additional expert feedback for trainers who elected to submit videos of training sessions.

Measures

All participants (i.e., both G1 and G2 clinicians) completed a battery of measures at baseline (pre-training), 6-months, 12-months, and 24-months (follow-up). For the purposes of the current study, only baseline and 24-month assessment data was used. In addition to the battery of assessments, G1 clinicians were invited to complete a phone interview regarding their experiences in conducting WAT, and to obtain more information regarding the CM and the sustainability of PCIT at their agencies. These phone interviews took place throughout 2016 and 2017, after the 24-month assessment timepoint for all participants. Any participant (G1 or G2) who left their organization during the study was still eligible to complete study assessments, consistent with an intent-to-train approach.

Clinician Background Form.

The Clinician Background Form contains 25 items to collect participant demographics, contact information, education and professional background, and current employment. Information collected on the Clinician Background Form was used to understand study participants’ characteristics and to assess for differences between G1 and G2 clinicians. All participants completed this measure at baseline.

Within Agency Training and Sustainability Interview.

The Within Agency Training and Sustainability Interview Guide was developed based on a similar interview guide used in prior studies examining the sustainability of EBPs.40 Interview questions were included to assess the sustainability of PCIT within participating agencies and to obtain information regarding WATs provided by G1 clinicians. Question relevant to the current study included: (a) did you choose to participate in the additional training to become a WAT trainer? (b) if not, what influenced your decision? (c) did you conduct any WAT? (d) how many clinicians did you train through WAT? and (e) how much time did you spend preparing for and conducting WAT? Participants were also asked to rate the following on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = Never, 2 = Rarely, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = A Lot, 5 = Almost Always): (a) how often they covered a variety of topics typically included in expert-led trainings (e.g., coaching strategies, parental engagement); (b) how often they used a variety of training techniques (e.g., didactics, observation of live sessions, co-therapy); and (c) how often they encountered specific barriers when attempting to conduct WAT. Information collected through the interview was used within the current study to assess for WAT equivalence with expert-led training and barriers to conducting WAT.

Your Experience – Treatment.

Both G1 and G2 clinicians completed a 9-item questionnaire regarding their experience delivering PCIT. The following questions were used to assess PCIT use as a training outcome in the current study: (a) how many families have you provided PCIT to in the past 6-months? (b) how many families have you provided PCIT to since beginning training? (c) how many families have you graduated? (i.e., how many have successfully completed treatment according to PCIT graduation criteria); (d) how often did you modify/adapt the treatment to better meet families’ needs? (1 = Never, 2 = Rarely, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = A Lot, 5 = Almost Always); and (e) how much of the standard PCIT protocol are you still using (1 = I’m not using it any longer, 2 = Parts of it, 3 = Full protocol).

PCIT Coaches Quiz.

Both G1 and G2 clinicians completed the PCIT Coaches Quiz, which is a 25-item measure that includes a mix of multiple choice and short answer questions. Questions are designed to assess general PCIT knowledge, as well as more specific knowledge pertaining to the PCIT protocol, clinical scenarios, and interpretation of clinical assessment data. A total score is derived by summing the number of correct answers (range = 0 to 25).41

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to understand training equivalence in terms of the content and procedures of WAT, as well as barriers to WAT. Chi-square tests of independence were used to assess for differences between G1 and G2 for all categorical variables. Due to violations in parametric assumptions (e.g., normality, equal groups), the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was conducted to assess for between-generation differences in interval or ratio variables. All analyses were conducted in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS).42

Results

Participants

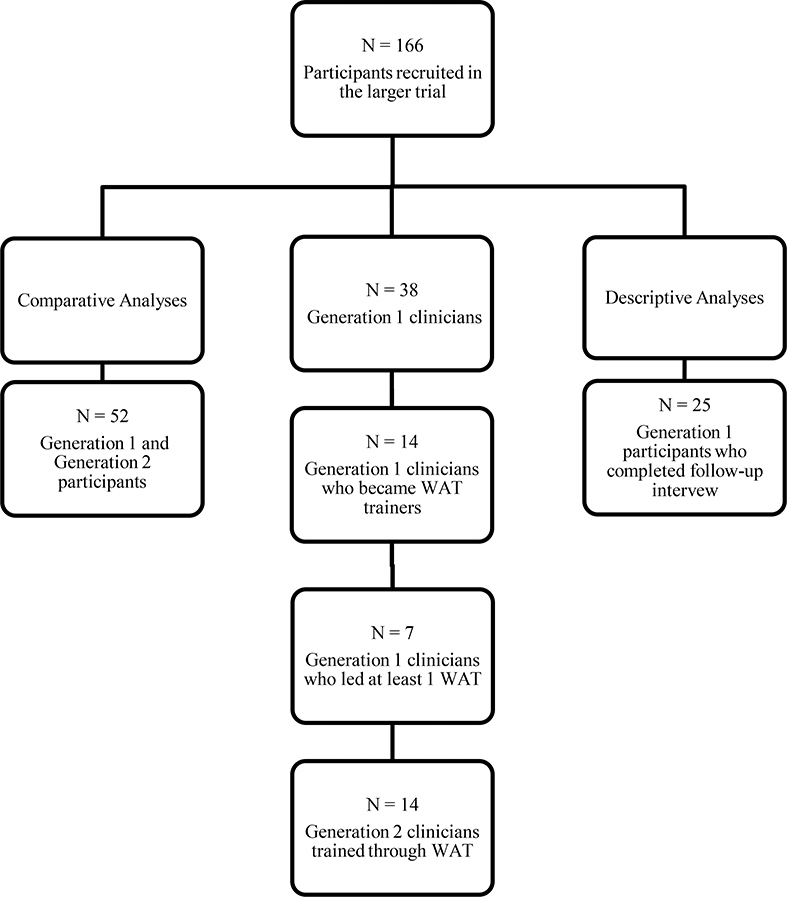

Participants in the current study included 38 G1 clinicians (i.e., they received expert-led training in PCIT and were eligible to train others within their agency) and 14 G2 clinicians (i.e., they were trained by a G1 clinician through WAT). Of the 38 G1 participants, a total of 28 participants (74%) completed the follow-up phone interview. See Table 1 for demographic breakdown of interview completers and noncompleters and Figure 1 for a visual breakdown of the total sample and subsamples.

Table 1.

Demographics of Interview Completers and Non-Completers

| Interview Completers N = 28 | Interview Non-Completers N = 10 | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Demographic Variables | N(%) or M(SD) | N(%) or M(SD) |

| Age | 39.79 (10.42) | 41.79 (9.40) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 25 (89.3%) | 8 (80.0%) |

| Male | 3 (10.7%) | 2 (20.0%) |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| African American | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Caucasian | 27 (96.4%) | 10 (100.0%) |

| Native American/ Alaska Native | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Native Hawaiian/ Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Multiracial | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Not Reported | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino/a | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latina/a | 27 (96.4%) | 10 (100.0%) |

| Level of Education | ||

| Masters degree | 28 (100.0%) | 10 (100.0%) |

| Doctoral degree | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Professional Licensure | ||

| Yes | 9 (32.1%) | 5 (50.0%) |

| No | 19 (67.9%) | 5 (50.0%) |

| Job Type | ||

| Part Time | 6 (21.4%) | 2 (20.0%) |

| Full Time | 22 (78.6%) | 8 (80.0%) |

| Years Experience | 12.04 (9.42) | 13.20 (9.64) |

| Years at Organization | 4.11 (4.21) | 6.60 (9.08) |

Figure 1:

Flow diagram outlining the two different samples used within the current study.

A series of chi-square tests of independence and Mann-Whitney U tests were calculated to assess for demographic differences between G1 and G2 participants. No statistical differences were noted in age (z = −1.05, p = .29), gender (χ2[1, 52] = .01, p = .91), level of education (χ2[1, 48] = 3.88, p = .05), professional license status (χ2[1, 48] = 1.01, p = .32), or license type (χ2[3, 15] = 4.62, p = .20). Additionally, no statistical differences were noted in the average years of experience (z = −1.68, p = .10) or years at the current organization (z = −1.92, p = .06).

There were statistically significantly differences in the race (χ2[2, 52] = 17.85, p < .001) and ethnicity (χ2[1, 48] = 4.08, p = .04) of G1 and G2 participants. Overall, the G2 sample reported more racial and ethnic diversity than the G1 sample. More specifically, a greater percentage of G2 participants did not report their race (37.8%) or were African American (14.3%) and were Hispanic or Latino/a (20.0%) compared with G1 participants (2.6% not reported, 0% African American, 2.6% Hispanic or Latino/a). In addition, a smaller proportion of G2 (50.0%) participants were Caucasian compared with G1 participants (97.4%). A statistically significant difference was also noted in the percentages of G1 and G2 participants who were part- vs. full-time employees (χ2[1, 48] = 8.83, p = .003). A greater percentage of G2 participants were employed part-time (70.0%), while a greater percentage of G1 participants were employed full-time (90.9%). See Table 1 for all demographic information.

Training descriptives

Of the 25 G1 participants who completed the follow-up interview, 14 (56%) participated in the additional training to become WAT trainers. Seven of the 14 (50%) G1 participants who were trained to be trainers reported that they completed at least one WAT and trained between 1 and 5 additional clinicians (M = 1.73, SD = 1.49). WAT trainers invested an average of 59.38 hours (SD = 21.83) in all WAT-related activity, including training, consultation/supervision meetings, and co-therapy. G1 participants who declined to become WAT trainers reported on factors that influenced their decision. The most common factors included insufficient staff (i.e., not enough staff to provide client coverage; n = 5), lack of appropriate referrals (n = 4), lack of staff (i.e., no clinicians eligible for PCIT certification; n = 3), startup challenges (n = 3), and leaving the organization and/or field (n = 3).

Conducting WAT

The seven participants who completed at least one WAT rated the frequency with which they covered various topics corresponding to information covered in trainings led by PCIT experts. Topics that were most frequently covered included Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System (DPICS) coding, coaching strategies, parental engagement, homework completion, and session attendance. Topics that were covered less frequently included corporal punishment, referrals, PCIT research, room setup, and seclusion and restraint (Figure 2). Participants also reported on the frequency with which they used various training strategies, shown in Figure 3. The most frequently used strategies included didactics, competency checklists, and skills practice, while strategies that were used less frequently included reviewing recorded sessions, collaborating with other agencies, and using web-based resources. Finally, participants also rated the severity of a variety of barriers they faced in conducting WAT. The most common barriers endorsed were lack of trainer time, lack of PCIT referrals, and concerns for loss of productivity (Figure 4).

Figure 2:

Topics Covered During WAT

Figure 3:

Training Strategies used in WAT

Figure 4:

Barriers to Conducting WAT

Training outcomes

In addition to general descriptive information, various training outcomes were compared between G1 clinicians who were trained in PCIT by an expert trainer versus G2 clinicians who were trained by a G1-led WAT. These comparisons were evaluated to obtain greater understanding of the equivalence of trainings led by experts versus WAT led by G1clinicians.

PCIT knowledge.

At baseline, there were no statistical differences in average PCIT knowledge scores of G1 and G2 clinicians (z = −0.53, p = .61). Both G1 (z = −4.44, p < .001) and G2 (z = −1.96, p = .05) demonstrated statistically significant improvements in knowledge scores from baseline to 23-month follow-up. However, there was a statistically significant difference between the post-training knowledge scores (z = −2.35, p = .02), such that G1 clinicians (M = 69.19% correct, SD = 17.43) scored significantly higher than G2 clinicians (M = 53.71% correct, SD = 16.31) at the 24-month follow-up (Figure 5).

Figure 5:

Change in PCIT Knowledge Scores

PCIT use.

There were no statistically significant differences in the percentage of G1 (70.4%) versus G2 participants (42.9%) who reported providing any PCIT in the past 6 months (χ2[1] = 11.22, p = .18). Similarly, there were no statistically significant differences in the average number of families treated by G1 and G2 clinicians (z = −1.24, p = .23) or the average number of families who met graduation criteria for each generation (z = −1.26, p = .21; Table 2). Finally, no statistical differences were noted in the frequency with which G1 and G2 clinicians reported modifying PCIT to better meet the needs of their families (χ2[4] = 2.84, p = .59), or the amount of the full standard PCIT protocol they reported still using (χ2[2] = 2.81, p = .35).

Table 2.

Demographics of Generation 1 vs. Generation 2

| Generation 1 N = 38 | Generation 2 N = 14 | |||

|

| ||||

| Demographic Variables | N(%) or M(SD) | N(%) or M(SD) | χ2 or z | p |

|

| ||||

| Age | 40.32 (10.01) | 36.75 (9.71) | −1.05 | .29 |

| Gender | 0.01 | .92 | ||

| Female | 33 (86.8%) | 12 (85.7%) | ||

| Male | 5 (13.2%) | 2 (14.3%) | ||

| Race | 17.85 | .001 | ||

| Asian | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| African American | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (14.3%)+ | ||

| Caucasian | 37 (97.4%)+ | 7 (50.0%) | ||

| Native American/ Alaska Native | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Native Hawaiian/ Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Multiracial | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Not Reported | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (35.7%)+ | ||

| Ethnicity | 4.08 | .04 | ||

| Hispanic or Latino/a | 1 (2.6%) | 2 (20.0%)* | ||

| Not Hispanic or Latina/a | 37 (97.4%) | 8 (80.0%) | ||

| Level of Education | 3.88 | .05 | ||

| Masters degree | 38 (100.0%) | 8 (90.0%) | ||

| Doctoral degree | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | ||

| Professional Licensure | 1.01 | .32 | ||

| Yes | 14 (36.8%) | 2 (20.0%) | ||

| No | 24 (63.2%) | 8 (80.0%) | ||

| Job Type | 8.83 | .003 | ||

| Part Time | 8 (21.1%) | 7 (70.0%)** | ||

| Full Time | 30 (78.9%)** | 3 (30.0%) | ||

| Years Experience | 12.34 (9.36) | 8.30 (9.88) | −1.68 | .10 |

| Years at Organization | 4.76 (5.85) | 2.00 (2.94) | −1.92 | .06 |

|

| ||||

| Outcome Variables | N(%) or M(SD) | N(%) or M(SD) | χ2 or z | p |

|

| ||||

| Pre-Training Knowledge Score (% Correct) | 40.22 (10.42) | 38.22 (9.40) | −0.53 | .61 |

| Post-Training PCIT Knowledge Score (% Correct) | 69.19 (17.42)* | 53.71 (16.30) | −2.35 | .02 |

| Number of Families Treated | 9.29 (9.64) | 5.00 (5.68) | −1.24 | .23 |

| Number of Families Graduated | 1.32 (1.62) | 2.75 (2.50) | −1.26 | .21 |

significantly greater at the α = .05 level.

significantly greater at the α = .01 level.

significantly greater at the α = .001 level.

Training satisfaction.

Overall, G1 clinicians were significantly more satisfied with their training experience than G2 clinicians (χ2[4] = 13.91, p = .008). Specifically, 42.9% of G2 clinicians were neutral or somewhat dissatisfied with their training experience compared with 0.0% of G1 clinicians. Conversely, 71.4% of G1 clinicians were very satisfied with their training experience compared with 28.6% of G2 clinicians.

To obtain more detailed information, a series of chi-square tests of independence were computed to assess for differences in how helpful each generation of clinicians perceived various training components. Statistically significant differences were noted in how helpful G1 and G2 clinicians rated trainings in general (χ2[2] = 11.22, p = .004), with a greater percentage of G1 clinicians (64.3%) than G2 clinicians (14.3%) rating training as very helpful, and a greater percentage of G2 clinicians (28.6%) than G1 clinicians (0%) rating the training as providing very little help. Similarly, G1 clinicians had a more favorable perception of training materials. A significantly greater percentage of G1 clinicians (64.3%) than G2 clinicians (14.3%) rated training materials as very helpful. A greater percentage of G2 clinicians (28.6%) selected somewhat or very little when rating how helpful training materials were, whereas no G1 clinicians selected these responses (χ2[4] = 11.22, p = .02). In keeping with this trend, a greater percentage of G1 clinicians (71.4% vs. 14.3% G2) rated their trainers as very helpful, while a greater percentage of G2 clinicians (28.6% vs. 0.0% G1) selected somewhat or very little to indicate how helpful their trainers were (χ2[3] = 12.38, p = .006).

Discussion

The current study represents one of the first to examine, in detail, the use of the CM to train behavioral health clinicians in an EBP. While the CM is used frequently within behavioral health and across similar health service fields, its effectiveness in training subsequent generations of clinicians has not been adequately explored. To address this gap, the current study provided a detailed description of the training process and content used by G1 participants to train a second generation (G2) of clinicians, and compared G1 and G2 training outcomes.

Slightly more than half (56%) of G1 participants chose to become within-agency trainers, and half (50%) of those trained (i.e., 28% of the full sample) conducted at least one WAT. This amounts to roughly one-third of G1 clinicians who ultimately trained at least one G2 clinician in PCIT. In total, an additional 19 clinicians were trained through a G1-led WAT, expanding the size of the CM clinician sample by 50%. While it is important to more thoroughly understand strategies that could foster greater delivery of WATs by a larger percentage of G1 clinicians, these preliminary results are encouraging and lend support to the claim that CM trainings may help to alleviate some concerns related to limited training resources.21

Significant differences in two demographic variables were found between G1 and G2. When considering these demographic differences, it is important to keep in mind that participants within both groups were not randomly selected, but rather self-selected or were nominated to participate by agency leadership. First, the G2 group reported greater racial and ethnic diversity compared to the G1 group. While it is possible that non-White clinicians were less likely to express interest in attending expert-led trainings, it is important to consider that perhaps agencies were more likely to select White, non-Hispanic clinicians for these trainings. Second, G2 included a larger percentage of part-time employees than G1. One possible explanation for this finding is that full-time employees had greater flexibility in their schedules to commit to the dedicated time associated with workshop-based expert-led trainings, while part-time employees chose to capitalize on the opportunity to participate in a workplace-based WAT. It is also possible that employers were more likely to select full-time employees for expert-led trainings, regardless of part-time employee interest.

It is important to note that across the entire sample, non-White clinicians were more likely to be employed part-time (83.3%) than full-time (16.7%), while White clinicians were more likely to be employed full-time (75.3%) than part-time (24.4%; χ2[1] = 8.37, p = .004). This conflation between minority status and employment status within the current sample muddles the hypothesized rationales for the finding that WAT were more likely to target minority and part-time clinicians. As such, it is clear that additional research is needed to replicate and more fully understand this finding, though it does suggest that one possible and previously unreported benefit of the CM is the ability to increase the diversity of clinicians providing EBPs by affording training through a WAT to clinicians who may be overlooked for or unable to attend more intensive expert-led workshop trainings.

The success rate for adding generations of trained individuals through WAT could be even greater if identified barriers are addressed. Participants reported on barriers to becoming a trainer and barriers to completing WAT. Although some differences exist, one common barrier reported by both participants who declined to become trainers and those who became trainers but experienced difficulties in conducting WATs was a lack of staff and/or staff time. In the context of participants becoming trainers, this barrier likely takes the form of inadequate staff coverage for the participant to complete the additional training. In the case of trainers attempting to deliver WATs, this barrier is more related to having no available clinicians to train or insufficient time in which to train them. Despite these differences, this barrier ultimately boils down to workforce shortage concerns that have been noted across the behavioral health field.21,43 While solutions to overcoming this workforce concern are neither simple nor quick, this problem is well-recognized and workforce development has been an ongoing focus.10,44,45

Perhaps more important to address are the barriers unique to each group. Notably, concerns raised by participants who declined to become trainers appear to be related to lack of agency or organizational support. Conversely, participants who did become trainers were less likely to report that lack of agency support hindered their efforts to deliver WAT relative to other barriers. Taken together, this suggests organizational support is influential in whether clinicians pursue building capacity at the agency level through WAT. Accordingly, understanding staff perceptions of organizational support prior to training might be a useful strategy to identify agencies with high levels of support that would be able to use the CM and WAT most effectively. Similarly, it could help to identify agencies that may benefit from an organizational intervention46 to promote agency-wide changes to increase the likelihood of successful training and implementation efforts. Along these lines, researchers and trainers should carefully attend to contextual factors such as organizational support when selecting a training method.

Though the current study did not include any formal interventions to modify these barriers, anecdotal strategies to improve perceived organizational support were described by participants. Such strategies included changing the job titles of G1 clinician-trainers to signify a promotional shift in their job roles, and paying participants for their time spent in training (particularly in fee-for-service models, where time spent in training would have resulted in a diminished salary. Future research should consider investigating more widespread use of such strategies as a means of improving organizational support and fostering greater provision of WATs.

In addition to assessing success of the CM by examining the number of new G2 clinicians, it is also important to consider the extent to which WATs delivered by G1 clinicians were similar to expert-led training. Understanding the structure and content of WAT is crucial to ensuring that G2 clinicians received quality training. To that end, participants in the current study reported on both the content covered and the specific training strategies they used most frequently during their WAT.

In general, G1 clinicians reported covering the majority of topics included in expert-led trainings at least some of the time. Exceptions included corporal punishment and seclusion and restraint, which were reported by G1s to be never or rarely covered in training, although these are among the 24 topics routinely covered by expert trainers. Given that these are two very sensitive topics, often with legal ramifications stipulated through statewide policies, it is possible that agencies include these topics in their onboarding training for new employees, precluding the need to include them in WAT. However, it is also possible that G1 clinicians either assumed that these topics were covered elsewhere or felt as though they were not adequately prepared to discuss them during WAT. Regardless of the reason, these are important topics and it is crucial to ensure that clinicians practicing PCIT receive adequate training surrounding these issues.

While there was consistency across G1 clinicians in terms of the content included in WAT, there appeared to be more variability in their use of training strategies. The use of didactics was the one training strategy which all G1 clinicians reported using a lot or almost always. This is promising, as PCIT expert trainers recommend a didactic component followed by more active and engaging strategies such as roleplays or video demonstrations.34 However, the frequency with which G1 clinicians reported using these more active strategies varied. Notably, the use of a co-therapy model, which is one such active training strategy recommended by PCIT expert trainers, was used less frequently than might be expected particularly given the emphasis on a co-therapy model during the training of G1 clinicians. Because participants reported on more global barriers rather than on barriers specific to different training strategies, uncertainty remains regarding the relatively infrequent use of co-therapy. However, one possible explanation is that billing and scheduling restrictions may have limited the use of co-therapy within specific agencies, as only one clinician would be able to bill for a co-therapy session. In a similar vein, it is important to consider that participants tailored their use of more active training strategies to their unique agencies, which would account for some of the variability noted in the use of these strategies. For instance, if group supervision is built into agency structure, it may be more feasible to incorporate training exercises into that existing component. Unfortunately, no information was collected regarding rationales for the selection of training strategies. An important future direction would be to collect such information in order to understand why certain strategies were favored and to develop recommendations for training strategies best suited to different treatment settings.

Another novel feature of the current study was the comparison of training outcomes between G1 and G2 clinicians. Importantly, while both groups demonstrated statistically significant improvements in PCIT knowledge over time, G1 clinicians had, on average, significantly greater PCIT knowledge scores at the follow-up assessment timepoint than G2 clinicians. As similar content appears to have been covered between expert trainings and WATs, this specific finding may indicate that the training strategies used during WAT did not foster the same depth of learning as the training strategies used by experts. Although the current study did not allow for a direct examination of why G2 clinicians did not demonstrate equivalent gains in knowledge to G1 clinicians, the hypothetical explanation offered above is supported by training satisfaction findings, in which G2 clinicians were less satisfied with their training experience than G1 clinicians. As the main difference between the expert-led training and WAT appeared to be the training strategies used, it is possible that both lower follow-up knowledge and lower satisfaction rates were driven by less effective training strategies.

It is also notable that, despite the emphasis on the use of a co-therapy model within training provided to G1 clinicians, didactic training was more frequently endorsed by G1 clinicians who conducted WAT. Although the emphasis on a co-therapy model was driven by information provided by PCIT experts in an effort to foster more active learning for G2 clinicians, a different approach may need to be considered if co-therapy models remain challenging to incorporate into community behavioral health settings. Specifically, it is important to note that PCIT Master Trainers tend to be doctoral-level individuals with some background in teaching or training through academic medical centers or graduate training programs.34 As such, they have likely honed their didactic teaching skills through a variety of experiences, and have been able to apply these skills and experiences to foster effective didactic instruction when conducing PCIT trainings. Given that current findings suggest G1 clinicians are more likely to be Masters-level clinicians without a background in teaching and training, perhaps they would benefit from explicit instruction of effective communication during didactic instruction.

It is particularly important for future research to continue comparing these training outcomes. The current study is one of the first to directly compare training outcomes for different generations trained in the CM. Given this study’s small sample size, additional research is needed to replicate this finding and to understand if this dilution of training is common across different types of participants, interventions, and treatment settings. Also, the goal of the CM is to be self-sustainable, ideally with G1 clinicians delivering multiple waves of WAT to subsequent generations. It would be important to examine if G1 clinicians are able to adjust their training styles over time to improve outcomes for later waves. If G1 clinicians are unable to self-adjust, it may indicate the need for improved initial training or for an audit and feedback process.47 Finally, the current study examined clinician knowledge but not skill. As research has shown that knowledge does not always translate into active skill use,6 it is possible that results may differ when clinician skill is the target training outcome rather than knowledge.

Limitations

While the current study addresses a gap in the training literature and has several strengths, there are also limitations to consider. First, a small sample size and unequal groups resulted in limited power for analyses and comparative findings should be considered with caution. In addition to offering greater power, a larger sample size would have allowed for more sophisticated analyses to provide a nuanced understanding of the multitude of factors that may have influenced training outcomes. Despite the small sample size, the current study provides information on a relatively novel area of study. It is crucial for future research to examine the CM with larger samples to obtain greater understanding of the potential utility of CM in broadening the workforce.

It is important to note that the current study was part of a larger RCT designed to compare three training methods, including the CM. While this provided a unique opportunity to more closely examine the CM, the focus in the larger study design was to compare outcomes across each training method, with the emphasis for the CM on G1 outcomes and not necessarily WAT outcomes. Future research focused exclusively on the CM would allow for greater control in the selection of outcome variables and assessment measures. Relatedly, the parent study included family outcomes, which were not examined in the current study. As the best indicator of well-trained clinicians is their ability to promote improved client outcomes, future research may consider comparing client outcomes for those treated by G1 and G2 clinicians.

An additional limitation related to the parent study was the reliance on study-developed measures. Many implementation trials are similarly limited by the lack of psychometrically-sound measures of relevant training outcomes, and the development of such measures has been identified as a priority for the field.48 Compounding this issue was the reliance in the current study on clinician self-report. While attempts were made to obtain videos from both G1 and G2 clinicians, a limited percentage of clinicians submitted videos for review. Findings may have been different if direct observation of clinician skill had been used, as research has indicated that clinician self-report often overestimates use of and fidelity to EBPs.49 Future research should consider the use of live observation or video review, and may need to develop creative solutions to overcome barriers associated with direct skill observation in community-based research.

The current sample and intervention have specific characteristics which may limit generalizability. First, the clinician sample consisted primarily of individuals who were female and Caucasian. While this is generally representative of the U.S. behavioral health workforce50 and therefore not necessarily a limitation, findings may not generalize to specific geographic locations with a more culturally diverse workforce, or to different cultures outside of the U.S. Second, the EBP used in the current study was a highly manualized intervention with a unique in vivo coaching component. Coaching is often a focus of training, differentiating PCIT training from training for other EBPs. As such, it is possible that the current findings are unique to PCIT and would not be found if the CM was used to train providers in a different EBP. In a similar vein, eligibility requirements included that participants have no prior training in PCIT; however, no information was collected regarding more general clinical training, or training in other behavioral parent training models. It is possible that clinicians with more prior experience with different behavioral parent training models would be better suited to participate inWAT to learn PCIT, as they could focus more on coaching technique without also having to learn more general behavioral parenting principles. As such, an interesting direction for future research would be to compare individuals with different levels of expertise and prior training in various EBPs.

Finally, care was taken to balance PCIT International training guidelines37 with the realities of the grant timeline and resources. However, the WAT procedures included in this study were planned before (2012) new within agency trainer guidelines were approved (03/02/2013). Therefore, the process described above and used within the current study differs from PCIT International training guidelines.

Implications for Behavioral Health

Concerns regarding the research to practice gap in behavioral health interventions have resulted in several creative and innovative strategies to increase the availability of EBPs in the community. The CM represents one such innovation that many have hypothesized would facilitate greater adoption and sustainment of EBPs, but that has been understudied in the literature. The current study provided mixed evidence regarding the use of the CM to train clinicians in PCIT. While results indicated that the use of the CM increased the number of clinicians by 50% and reached a more diverse group of clinicians, uncertainty remains regarding the quality of training that G2 clinicians received and the extent to which their training resulted in sufficient gains in knowledge. Future research is needed to continue extensively examining this promising training strategy and to understand if a large number of adequately-trained clinicians is more beneficial to consumers than a small number of exceptionally-trained clinicians.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest Statement

This study was funded by a grant provided by the National Institute of Mental Health: R01 MH095750; A Statewide Trial to Compare Three Training Models for Implementing an EBT; PI: Herschell; 9/18/12-12/31/17.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.American Psychological Association. Task Force on Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures; 1993.

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services. President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Achiev Promise Transform Ment Heal Care Am Exec Summ. 2003.

- 3.National Institute of Mental Health. Bridging Science and Service: A Report by the National Advisory Mental Health Council’s Clinical Treatment and Services Work Group. Rockville, MD; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(50):40–55. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aarons GA, Wells RS, Zagursky K, et al. Implementing evidence-based practice in community mental health agencies: A multiple stakeholder analysis. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(11):2087–2095. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, et al. The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: A review and critique with recommendations. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(4):448–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2010;17(1):1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beidas RS, Edmunds JM, Marcus SC, et al. Training and consultation to promote implementation of an empirically supported treatment: a randomized trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(7):660–665. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stirman SW, Kimberly J, Cook N, et al. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyon AR, Stirman SW, Kerns SEU, et al. Developing the mental health workforce: Review and application of training approaches from multiple disciplines. Adm Policy Ment Heal Ment Heal Serv Res. 2011;38(4):238–253. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0331-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sholomskas DE, Syracuse-Siewart G, Rounsaville BJ, et al. We don’t train in vain: A dissemination trial of three strategies of training clinicans in Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(1):106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.02.002.A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez MA, Osterberg LD, Jensen-Doss A, et al. Effects of workshop training for providers under mandated use of an evidence-based practice. Adm Policy Ment Heal Ment Heal Serv Res. 2011;38(4):301–312. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0326-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Funderburk B, Chaffin M, Bard E, et al. Comparing client outcomes for two evidence-based treatment consultation strategies. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;44(5):730–741. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.910790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruns EJ, Hoagwood KE, Rivard JC, et al. State implementation of evidence-based practice for youths, Part II: Recommendations for research and policy. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(5):499–504. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181684557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyde PS, Falls K, Morris JA, et al. Turning knowledge into practice: A manual for behavioral health administrators and practitioners about understanding and implementing evidence-based practices. MA Tech Assist Collab. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldfine ME, Wagner SM, Branstetter SA, et al. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy: An examination of cost-effectiveness. J Early Intensive Behav Interv. 2008;5(1):119–141. doi: 10.1037/h0100414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dopp AR, Hanson RF, Saunders BE, et al. Community-based implementation of trauma-focused interventions for youth: Economic impact of the learning collaborative model. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):57–65. doi: 10.1037/ser0000131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoge MA, Stuart GW, Morris JA, et al. Behavioral health workforce development in the United States. In: Substance Abuse and Addiction: Breakthroughs in Research and Practice. Hershey, PA: Information Resources Management Association; 2019:433–455. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olfson M Building the mental health workforce capacity needed to treat adults with serious mental illnesses. Health Aff. 2016;35(6):983–990. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fairburn CG, Patel V. The global dissemination of psychological treatments: A road map for research and practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(5):495–498. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13111546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stuart S, Schultz J, Ashen C. A new community-based model for training in evidence-based psychotherapy practice. Community Ment Health J. 2018;0(0):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10597-017-0220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayes D Cascade training and teachers’ professional development. ELT J. 2000;54(April):135–145. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shire SY, Kasari C. Train the trainer effectiveness trials of behavioral intervention for individuals with autism: A systematic review. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2014;119(5):436–451. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-119.5.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andzik N, Cannella-Malone HI. A review of the pyramidal training approach for practitioners working with individuals with disabilities. Behav Modif. 2017;41(4):558–580. doi: 10.1177/0145445517692952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Scudder AT, et al. Protocol for a statewide randomized controlled trial to compare three training models for implementing an evidence-based treatment. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):133. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0324-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brabson LA, Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, et al. Associations among job role, training type, and staff turnover in a large-scale implementation initiative. J Behav Heal Serv Res. 2019:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s11414-018-09645-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greif R, Becker CB, Hildebrandt T. Reducing eating disorder risk factors: A pilot effectiveness trial of a train-the-trainer approach to dissemination and implementation. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(8):1122–1131. doi: 10.1002/eat.22442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith TL, Landes SJ, Lester-Williams K, et al. Developing alternative training delivery methods to improve psychotherapy implementation in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Train Educ Prof Psychol. 2017;11(4):266–275. doi: 10.1037/tep0000156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Triplett NS, Sedlar G, Berliner L, et al. Evaluating a train-the-trainer approach for increasing EBP training capacity in community mental health. J Behav Heal Serv Res. 2020;1(11). doi: 10.1007/s11414-019-09676-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baldwin TT, Ford JK. Transfer of training: a review and directions for future research. Pers Psychol. 1988;41(1):63–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1988.tb00632.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraiger K, Ford JK, Salas E. Application of cognitive, skill-based, and affective theories of learning outcomes to new methods of training evaluation. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78(2):311–328. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.2.311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eyberg SM, Funderburk BW. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy Protocol. Gainesville, FL: PCIT International; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.PCIT International Inc. Get certified by PCIT International. http://www.pcit.org/pcit-certification.html. Accessed December 5, 2016.

- 34.Scudder AT, Herschell AD. Building an evidence-base for the training of evidence-based treatments in community settings: Use of an expert-informed approach. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2015;55:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McNeil CB, Hembree-Kigin TL. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chadwick Center for Children and Families. Closing the Quality Chasm in Child Abuse Treatment: Identifying and Disseminating Best Practices. San Diego, CA; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37.PCIT International Inc. Training Guidelines for Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.PCIT International Inc. Certified PCIT Master Trainers. http://www.pcit.org/mastertrainers.html. Accessed May 9, 2020.

- 39.Krathwohl DR, Anderson LW. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives; 2009.

- 40.Swain K, Whitley R, McHugo GJ, et al. The Sustainability of Evidence-Based Practices in Routine Mental Health Agencies. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46:119–129. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9202-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Funderburk B, Nelson M. PCIT Coaches Quiz. 2014.

- 42.IBM Corp. IBP SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. 2017.

- 43.Thomas KC, Ellis AR, Konrad TR, et al. County-level estimates of mental health professional shortage in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(10):3–8. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.10.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dailey WF, Morris JA, Hoge MA. Workforce development innovations with direct care workers: better jobs, better services, better business. Community Ment Health J. 2015;51(6):647–653. doi: 10.1007/s10597-014-9798-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoge MA Morris JA, Stuart GW, et al. A national action plan for workforce development in behavioral health. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(7):883–887. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.7.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glisson C, Schoenwald SK. The ARC organizational and community intervention strategy for implementing evidence-based children’s mental health treatments. Ment Health Serv Res. 2005;7(4):243–259. doi: 10.1007/s11020-005-7456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stuart GW, Tondora JS, Hoge MA. Evidence-based teaching practice: Implications for behavioral health. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2004;32(2):107–130. doi: 10.1023/B:APIH.0000042743.11286.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martinez RG, Lewis CC, Weiner BJ. Instrumentation issues in implementation science. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0118-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hogue A, Dauber S, Lichvar E, et al. Validity of Therapist Self-Report Ratings of Fidelity to Evidence-Based Practices for Adolescent Behavior Problems: Correspondence between Therapists and Observers. Adm Policy Ment Heal Ment Heal Serv Res. 2014;42:229–243. doi: 10.1007/s10488-014-0548-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.American Psychological Association. Demographics of the U.S. Psychology Workforce: Findings from the 2007–2016 American Community Survey. Washington, D.C.; 2018. [Google Scholar]