Abstract

Introduction:

Fever and thrombocytopenia, often presenting features of malaria, are also the hallmarks of dengue infections. This study examines the degree and duration of thrombocytopenia in imported malaria infections in Sri Lanka and the extent to which this could provide a false trail in favor of a dengue diagnosis.

Methods:

The data of all confirmed malaria cases reported in Sri Lanka from 2017 to 2019 were extracted from the national malaria database. These included detailed histories, the time to malaria diagnosis, platelet counts, and in 2019, the trail of diagnostic procedures.

Results:

Over the 3 years, 158 malaria cases (157 imported and one introduced) were reported. Platelet counts were available in 90.5% (n = 143) of patients among whom 86% (n = 123) showed a thrombocytopenia (<150,000 cells/μl) and in nearly a third (n = 52) a severe thrombocytopenia (<50,000 cells/μl). Only 30% of patients (n = 48) were diagnosed with malaria within 3 days of the onset of symptoms, while in 37% (n = 58) it took 7 or more days. Platelet counts where significantly higher in patients who had symptoms for 7 days or more compared to those who had symptoms for <7 days (χ2 = 6.888, P = 0.009). Dengue fever was suspected first in 30% (n = 16) of the total malaria patients reported in 2019.

Conclusions:

Low platelet counts could delay suspecting and testing for malaria. Eliciting a history of travel to a malaria-endemic country could provide an important and discerning clue to suspect and test for malaria in such patients.

Keywords: Delayed diagnosis, dengue, imported malaria, thrombocytopaenia

INTRODUCTION

Sri Lanka has reported zero indigenous malaria cases since November 2012. Since 2016 when the country received WHO certification of malaria elimination, Sri Lanka has reported around 50 imported malaria cases annually. The presence of Anopheles species of mosquitoes that are primary and secondary vectors, in rising densities in Sri Lanka makes it a highly receptive environment for the re-introduction of malaria to the country. Hence, sustaining this status of malaria elimination is a continuing challenge for the health system.

Early diagnosis and treatment of imported malaria patients and an active case and entomology surveillance and response system have been the mainstay of preventing the re-introduction of malaria to Sri Lanka.[1] Malaria microscopy services which is mainly performed by Public Health Laboratory Technicians (PHLTs) and Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) are widely available in public sector health institutes throughout the country. Malaria RDTs are also available at public sector hospitals and health institutes where PHLTs are not available.[2] The government of Sri Lanka provides free health care services through an extensive network of curative care institutions ranging from Teaching Hospitals with specialized consultative services to smaller Primary Health Care Units which provide only outpatients services. In addition, there are a large number of private-sector health institutions distributed throughout the country providing services from general practice consultation chambers to specialized institutions providing tertiary care services where malaria diagnosis is available. Passive case detection (PCD) is the main method of diagnosing malaria infections, with 48/53 (90.5%) imported malaria cases diagnosed by PCD in 2019 and 100% (n = 48) of cases diagnosed in 2018. Medical practitioners in Sri Lanka are trained in eight state Universities and the Kotelawala Defence University academy and recruited by the Ministry of Health or Tri-Forces to be deployed across the island. With a low number of imported malaria cases being diagnosed in the country, most young clinicians have only a textbook knowledge of the disease, not having seen a malaria patient either during or after their training.

Delay in the diagnosis of malaria has been one of the main challenges in keeping the country malaria-free.[3,4] Despite there being excellent diagnosis and curative facilities for malaria in the country, the disease is rarely included in the initial differential diagnosis of a patient presenting with fever owing to its very low incidence. It has been the experience of the Anti Malaria Campaign (AMC) that most malaria patients in the country after malaria elimination have been investigated for dengue and to a lesser extent for other febrile illnesses more prevalent in the country before suspecting and testing for malaria, this being a principal reason for delays in diagnosis of malaria. Thrombocytopaenia which when combined with fever is a cardinal feature of dengue is also a common accompaniment of malaria and this has aggravated the problem by luring clinicians to investigate malaria patients for dengue infection, overlooking malaria as a possible alternative, for several days.

This study aimed to describe the occurrence of thrombocytopenia in the imported malaria cases treated in Sri Lanka by retrospectively analyzing the case data reported between 2017 and 2019. Information on the diagnostic path of patients reported in 2019, was used to demonstrate how and why a false trail of dengue have delayed the detection of some malaria infections.

METHODS

Secondary analysis of the total Malaria cases reported between 2017 and 2019 extracted from the malaria case database maintained at the AMC Headquarters was performed. Malaria diagnosis of all these patients was confirmed by quality-assured microscopy carried out at the central laboratory of the AMC and RDTs. Platelet counts were measured during the 1st day or 2 of a patient presenting for health care and assessed as a component of full blood counts (FBCs) in quality certified laboratories. Thrombocytopenia is defined as platelets <150,000/μL. Three levels of severity thrombocytopenia are described as less than 50,000/μL, 50,001/μL– 100,00/μL, 100,001/μL- 150,000/μL, and the normal range of platelet count as more than 150,001/μl.[5,6]

The case data were analyzed in relation to patients' demographics, type of malaria species, country of origin, and severity of cases. The relationship between thrombocytopenia of <150,000/μl with the type of species, delay in diagnosing of malaria over 7 days were assessed using Pearson's Chi-square and t-tests. A P < 0.05 was considered as significant to interpret the findings. How primarily suspecting dengue fever had delayed the diagnosis of malaria was described using case data of only the year 2019 with descriptive statistics. Analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 365- Microsoft Corporation Inc. Redmond, Washington USA. Version 2019SPSS - SPSS Inc. IBM Corp. Armonk, New York, USA Version 21.

RESULTS

General characteristics of malaria patients

A total of 158 malaria cases were detected in Sri Lanka over the period 2017–2019 out of which, 157 were imported and one was an introduced case reported in December 2019.[7] A majority were males (90.5%, n = 143). A description of the demographics is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample 2017–2019 (n=158)

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age categories (years) | |

| 0-20 | 5 (3.1) |

| 21-40 | 84 (53.2) |

| 41-60 | 57 (36.1) |

| 61-80 | 12 (7.6) |

| Risk category | |

| Gem traders | 25 (15.8) |

| Armed forces and police | 17 (10.7) |

| Pilgrims to India | 11 (7.0) |

| Construction workers | 11 (7.0) |

| Seamen | 5 (3.2) |

| Other different categories | 89 (56.3) |

| Country/region of origin of malaria | |

| Africa | 88 (55.7) |

| India | 56 (35.4) |

| Other South East Asia countries | 8 (5.1) |

| Other | 5 (3.1) |

| Nationality | |

| Sri Lankans | 113 (71.5) |

| Indians | 15 (9.5) |

| Other nationalities | 30 (19.0) |

| Plasmodium species | |

| P. vivax | 81 (51.3) |

| P. falciparum | 64 (40.5) |

| P. ovale | 9 (5.7) |

| P. malariae | 4 (2.5) |

| Clinical severity | |

| Uncomplicated | 148 (93.6) |

| Severe | 8 (5.0) |

| Treatment failure | 2 (1.2) |

P. falciparum: Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax: Plasmodium vivax, P. ovale: Plasmodium ovale, P. malariae: Plasmodium malariae

Imported malaria patients were mainly adult males (89.3%, n = 141) in the 21–60-year age group. The most commonly infected risk categories were gem traders who frequently visit African nations and armed forces personnel who return from United Nations peacekeeping missions. Fifty-five per cent of imported infections originated from countries in the African continent and 35% from India. Infections originating from India were mainly in-migrant laborers employed in Sri Lanka in large-scale development projects, and Sri Lankan pilgrims and traders arriving from India. Plasmodium vivax infection was diagnosed in 51.3% (n = 81) of patients and Plasmodium falciparum in 40.5% (n = 64).

Clinical picture and the prevalence of thrombocytopaenia

All the cases diagnosed with malaria were reported to the health system with fever as the presenting symptom. Records of the platelet count were available in 90.5% (n = 143) of patients. Among these patients, 86% showed thrombocytopenia of <150,000 cells/μl. A severe thrombocytopenia of <50,000 cells/μl was found in nearly a third (n = 52) of patients with malaria [Table 2].

Table 2.

Platelet count in patients according to Plasmodia species

| Platelet count (/µL) | Total cases (n=143), n (%) | P. falciparum (n=56), n (%) | P. vivax (n=75), n (%) | P. ovale (n=9), n (%) | P. malariae (n=3), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-50,000 | 26 (18.2) | 9 (16.1) | 12 (16.0) | 0 | 0 |

| 50,001-100,000 | 69 (48.3) | 24 (42.9) | 33 (44.0) | 5 (55.6) | 1 (33.3) |

| 100,001-150,000 | 28 (19.6) | 13 (23.2) | 20 (26.6) | 3 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) |

| >150,001 (normal range) | 20 (14.0) | 10 (17.8) | 10 (13.4) | 1 (11.1) | 0 |

| Total | 143 (100) | 56 (100) | 75 (100) | 9 (100) | 3 (100) |

There was no significant difference in the presence of thrombocytopenia <150,000 cells/µl between P. falciparum and P. vivax malaria (χ2=0.448, P=0.5). P. falciparum: Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax: Plasmodium vivax, P. ovale: Plasmodium ovale, P. malariae: Plasmodium malariae

There was no significant difference in the presence of thrombocytopenia <150,000 cells//μl between P. falciparum and P. vivax malaria (χ2 = 0.448, P = 0.5).

Time to a malaria diagnosis and platelet counts in relation to the duration of malaria illness

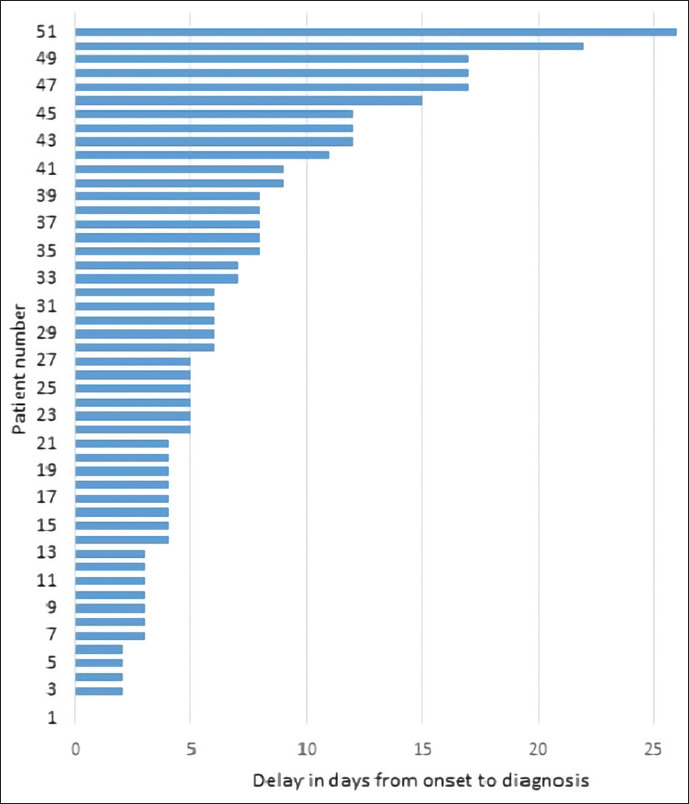

The time taken from the onset of symptoms to a malaria diagnosis in 157 patients varied from 0 (being on the day of onset of symptoms) to 66 days [Figure 1]. One outlier with a history of symptoms for 107 days in whom the long duration of symptoms was thought to have been due to other confounding comorbidities were excluded from this Figure. Only about a third of the patients were diagnosed within 3 days of the onset of symptoms. In nearly 37% of patients, it took seven or more days from the onset of symptoms to be diagnosed with malaria.

Figure 1.

Time to diagnosis in malaria patients reported in Sri Lanka 2017–2019

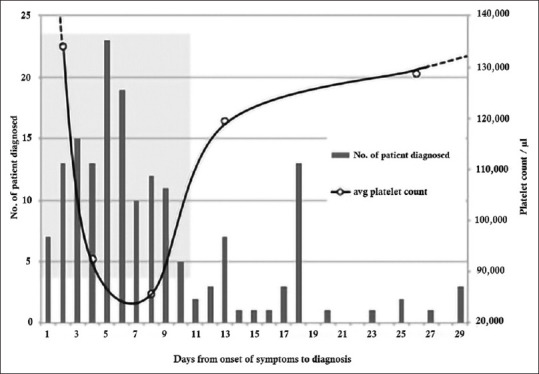

The platelet counts of patients were analyzed in relation to the time from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis, which was taken to represent the duration of the malaria illness [Table 3 and Figure 2]. Platelet counts were lowest in patients who had symptoms for 6–8 days and were significantly higher in patients who had symptoms for 10 days or more than they were in those who had symptoms for <7 days (P = 0.009). Eighty-eight per cent of patients who had symptoms for 7 days or less (n = 119) had a thrombocytopaenia (average platelet count = 95,531/ul) compared 71% of those who had symptoms for more than 10 days (n = 21); their average platelet count being 124,714/ul).

Table 3.

Platelet counts of malaria patients in relation to the duration of illness

| Number of days of symptoms | Number of patients | Average platelet count (/ul) |

|---|---|---|

| 0-2 | 29 | 134,034.5 |

| 3-5 | 53 | 92,579.2 |

| 6-8 | 32 | 85,756.2 |

| 9-12 | 15 | 119,366.7 |

| 13-66 | 13 | 128,769.2 |

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of platelet counts and high clinical suspicion of dengue overlaid on a timeline of malaria diagnosis of imported malaria infections 2017–2019

The clinical overlap of malaria with dengue

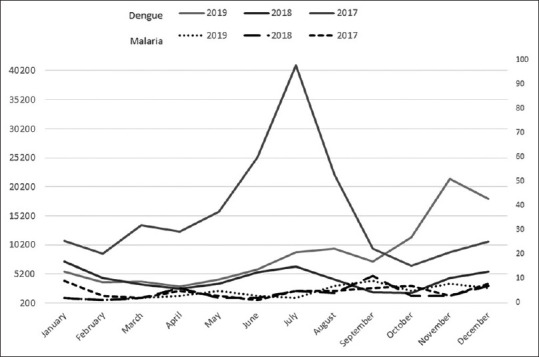

Dengue has been highly endemic in Sri Lanka for the past several years with a yearly reported incidence ranging from 51,659 to 186,101 from 2017 to 2019 [Figure 3] during which period it was by far the most major cause of febrile illness in the country.[8] Imported malaria cases on the other hand have been very few in number ranging from 48 to 57 cases per year during the same period [Figure 3]. It has been the experience of the AMC which fully investigates every case of malaria in the country, that several cases of malaria have been first investigated for a dengue infection when they sought health care, before suspecting malaria and testing for it, leading, in many, to delays in the diagnosis of malaria. The data reported in 2019 in whom detailed diagnostic history was available, are presented here in support of this.

Figure 3.

Incidence of dengue and (imported) malaria in Sri Lanka 2017–2019. The monthly incidence of dengue and malaria 2017–2019, with malaria plotted on a scale 40 times lower

In 2019, 48 malaria patients (all imported) were detected in Sri Lanka by PCD. All these patients gave a clear history of recent travel overseas. In 16 of these patients, there was documented evidence showing that clinicians had first suspected and investigated the patients for dengue. In all 16 patients, a FBC was performed on day 3, presumably with a diagnosis of dengue in mind, with no request being made for a malaria test. Based on the low platelet counts which the reports of all 16 patients showed (average platelet count = 93,763) they were all admitted to the hospital on suspicion of dengue infection and were tested for NS1 dengue antigen, which reported negative in all. It was only thereafter that a malaria diagnosis was pursued and made, either because the medical laboratory technician (MLT) detected malaria parasites in the blood smear while conducting the FBC, or based on the results of a malaria test which was subsequently requested by the attending physician or a member of the clinical team. In the rest of the 34 patients, there were no explicit records of the trail of diagnosis; and it was not that a dengue diagnosis was not pursued before testing for malaria.

DISCUSSION

Thrombocytopenia has been widely reported as a frequent accompaniment of malaria infections.[5,9,10] Of the 143 malaria patients reported here, 86% had low platelet counts (<150,0000/μl) and a third of them had severe thrombocytopenia (>50,000/ul). As has been reported previously[9] the degree of thrombocytopenia did not differ by malaria species. As the reconstruction shows, the platelet counts appear to drop very early during the clinical course of malaria infection and remain low for about a week. After the 1st week, the counts appear to rise slowly even without the infection being treated. As late as the 20th day of untreated malaria infections platelet counts were higher but had still not reached normal levels.

The pathophysiological basis of thrombocytopenia in malaria has not being clearly defined. Plausible theories include penetration of platelets by parasites similar to red blood cells, sequestration in the spleen and antibody-mediated destruction of platelets, and oxidative stress causing free radicals to destroy platelets.[9] Any or all of these pathophysiological mechanisms may underlie the thrombocytopenia spanning day 0 to more than 20 days of malaria infections.

The analysis and reporting presented here was undertaken because the diagnosis of imported malaria is being frequently delayed on account of clinicians pursuing a dengue diagnosis, at the cost of not requesting a malaria test. Given that epidemics of dengue have swept through the country in the past few years, with 186,101 cases of dengue infections being reported in 2017 alone,[11] dengue has been the principal cause, by far, of febrile illnesses in Sri Lanka. Thus, with malaria being an extremely rare disease, dengue will naturally receive high priority in the differential diagnosis of fever. Furthermore, as has been demonstrated here, low platelet counts accompanying malarial fever, which are also the best-known clinical hallmarks of dengue are likely to reinforce the false diagnostic trial in patients toward dengue, leading to further delays in malaria diagnosis. Thrombocytopenia (platelet count <150,000 cells/ul) in a febrile patient with headache and myalgia are criteria for suspecting dengue and indications for hospitalization for further management.[5] In pursuing a dengue diagnosis, clinicians often wait for a second platelet count at least 24 h after the first, to see if the counts drop, as an additional lead to a diagnosis of dengue, which delays, even further, the testing for alternative diseases such as malaria. The diagnostic history in the 16 patients described here to illustrate these unfortunate occurrences.

Delays in the diagnosis of imported malaria in malaria nonendemic countries are not uncommon owing to it being a rare disease and physicians not being familiar with malaria[4,12,13,14,15] with some obvious and potentially grave consequences: (1) increasing morbidity with a greater risk of infections progressing to severe complicated disease, and therefore also a higher risk of mortality, and (2) an increased likelihood of transmitting these untreated infections if the patient travels to areas where malaria vectors are prevalent, increasing the risk of re-introducing malaria to the country.

Under these circumstances, a reliable and discerning clue to a malaria diagnosis in Sri Lanka would be a history of recent travel to an endemic country. Such a history was, in fact, given by all but one patient with malaria reported in the past 3 years in Sri Lanka. In the past few years, the AMC has gone to great lengths to remind the medical profession of the need to seek a history of travel overseas to ensure early testing for malaria. Yet, there continue to be many instances where travel histories have not been sought from febrile patients and a malaria diagnosis either missed or delayed. Whenever there is a significant delay in the diagnosis of a malaria patient, senior staff of the AMC visits the health institution to conduct a clinician awareness program on malaria and provide the necessary training on the early diagnosis of malaria. The PHLTs of government hospitals are regularly trained to sustain their skills in diagnosing malaria by microscopy and RDTs because these skills may rapidly wane in the absence of a high disease burden. Training programs free-of-charge is also provided to MLT s in the private sector. Thus, good access to high-quality malaria testing is being made available in the country. Yet, given that less than a third of malaria were diagnosed within 3 days of the onset of symptoms, further efforts may be needed to shorten the time to diagnosis of malaria.

Febrile diseases other than dengue and malaria that lead to thrombocytopenia include atypical viral fever, leptospirosis, leishmaniasis, and viral hepatitis.[16] The combination of fever and thrombocytopenia can therefore be a red herring in delaying the diagnosis, not only of malaria but several other febrile conditions. A recent report from Singapore does in fact highlight how the presence of thrombocytopaenia led to delays in diagnosing two patients with SARS-CoV-2 because of repeated investigations for dengue; in both cases, the diagnosis was even further confounded by false-positive NS1 Test results for dengue.[17] Thus, in the wake of several other emerging infectious diseases, seeking a history of travel in febrile patients ought now to be routine in clinical practice anywhere in the world.

CONCLUSIONS

Thrombocytopenia, in some individuals of a severe degree, accompanying malaria can lead to a false trail of diagnosis in situations in situations where dengue is more prevalent than malaria. This is because the combination of fever and thrombocytopaenia are considered hallmarks of dengue illness. Repeated investigation for dengue in malaria patients presenting with thrombocytopaenia has led to delays in suspecting and testing for malaria. A delay in the diagnosis of imported malaria increases the chances of transmitting malaria to the vector mosquitoes and thereby of re-introducing malaria to the country. In post elimination situations, a history of travel to a malaria-endemic country could provide an important and discerning clue to suspect and test for malaria when patients present with fever and thrombocytopenia as malaria patients usually do.

Declarations

Availability of data and material

The data and material are available with the Director of the AMC, Sri Lanka.

Research quality and ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board University of Colombo (ERC18-084). The authors followed applicable EQUATOR Network (“http://www.equator-network.org/) guidelines during the conduct of this research project.

Financial support and sponsorship

Financial assistance from the University of Colombo is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anti-Malaria Campaign. National Malaria Strategic Plan for Elimination and Prevention of Reintroduction. Sri Lanka, 2014-2018. Sri Lanka: Ministry of Health, Nutrition and Indigenous Medicine; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ministry of Health, Nutrition and Indigenous Medicine. Malaria Elimination in Sri Lanka. National Report for WHO Certification. Sri Lanka: Ministry of Health, Nutrition and Indigenous Medicine; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Premaratne R, Ortega L, Janakan N, Mendis KN. Malaria elimination in Sri Lanka: What it would take to reach the goal. WHO South East Asia J Public Health. 2014;3:85–9. doi: 10.4103/2224-3151.206892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Premaratne R, Wickremasinghe R, Ranaweera D, Gunasekera WM, Hevawitharana M, Pieris L, et al. Technical and operational underpinnings of malaria elimination from Sri Lanka. Malar J. 2019;18:256. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-2886-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health. National Guidelines on the Management of Dengue Fever and Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever in Adults. collaboration with the Ceylon College of Physicians. 2012. [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 21]. Available from: http://www.epid.gov.lk/web/images/pdf/Publication/guidelines_for_the_management_of_df_and_dhf_in_adults.pdf .

- 6.Bhandary N, Vikram GS, Shetty H. Thrombocytopenia in malaria: A clinical study. Biomed Res. 2011;22:489–91. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karunasena VM, Marasinghe M, Koo C, Amarasinghe S, Senaratne AS, Hasantha R, et al. The first introduced malaria case reported from Sri Lanka after elimination: Implications for preventing the re-introduction of malaria in recently eliminated countries. Malar J. 2019;18:210. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-2843-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epidemiology Unit, Ministry of Health, Nutrition and Indigenous Medicine. Distribution of Notification (H399) Dengue Cases by Month, 2019. Ministry of Health, Sri Lanka. [Last accessed on 2020 Dec 20]. Available from: http://www.epid.gov.lk/web/index.php?option=com_casesanddeaths&Itemid=448&lang=en# .

- 9.Lacerda MV, Mourão MP, Coelho HC, Santos JB. Thrombocytopenia in malaria: Who cares? Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2011;106(Suppl 1):52–63. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762011000900007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gill MK, Makkar M, Bhat S, Kaur T, Jain K, Dhir G. Thrombocytopenia in malaria and its with different types of malaria. Ann Trop Med Public Health. 2013;6:197–200. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tissera HA, Jayamanne BD, Raut R, Janaki SM, Tozan Y, Samaraweera PC, et al. Severe dengue epidemic, Sri Lanka, 2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:682–91. doi: 10.3201/eid2604.190435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kain KC, Harrington MA, Tennyson S, Keystone JS. Imported malaria: Prospective analysis of problems in diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:142–9. doi: 10.1086/514616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg AE, Lobel HO. Mortality from Plasmodium falciparum malaria in travelers from the United States, 1959 to 1987. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:326–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-4-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorsey G, Gandhi M, Oyugi JH, Rosenthal PJ. Difficulties in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of imported malaria. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2505–10. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.16.2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernando SD, Ainan S, Premaratne RG, Rodrigo C, Jayanetti SR, Rajapakse S. Challenges to malaria surveillance following elimination of indigenous transmission: Findings from a hospital-based study in rural Sri Lanka. Int Health. 2015;7:317–23. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihv046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longmore JM. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan G, Lee CK, Lam LT, Yan B, Chua YX, Lim AY, et al. Covert COVID-19 and false-positive dengue serology in Singapore. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:5–P526. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30158-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data and material are available with the Director of the AMC, Sri Lanka.