Abstract

Background: The availability of comprehensive data on the ecology and molecular epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus/MRSA in wild animals is necessary to understand their relevance in the “One Health” domain. Objective: In this study, we determined the pooled prevalence of nasal, tracheal and/or oral (NTO) Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) carriage in wild animals, with a special focus on mecA and mecC genes as well as the frequency of MRSA and methicillin susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) of the lineages CC398 and CC130 in wild animals. Methodology: This systematic review was executed on cross-sectional studies that reported S. aureus and MRSA in the NTO cavities of wild animals distributed in four groups: non-human primates (NHP), wild mammals (WM, excluding rodents and NHP), wild birds (WB) and wild rodents (WR). Appropriate and eligible articles published (in English) between 1 January 2011 to 30 August 2021 were searched for from PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, SciElo and Web of Science. Results: Of the 33 eligible and analysed studies, the pooled prevalence of NTO S. aureus and MRSA carriage was 18.5% (range: 0–100%) and 2.1% (range: 0.0–63.9%), respectively. The pooled prevalence of S. aureus/MRSA in WM, NHP, WB and WR groups was 15.8/1.6, 32.9/2.0, 10.3/3.4 and 24.2/3.4%, respectively. The prevalence of mecC-MRSA among WM/NHP/WB/WR was 1.64/0.0/2.1/0.59%, respectively, representing 89.9/0.0/59.1/25.0% of total MRSA detected in these groups of animals.The MRSA-CC398 and MRSA-CC130 lineages were most prevalent in wild birds (0.64 and 2.07%, respectively); none of these lineages were reported in NHP studies. The MRSA-CC398 (mainly of spa-type t011, 53%), MRSA-CC130 (mainly of spa types t843 and t1535, 73%), MSSA-CC398 (spa-types t571, t1451, t6606 and t034) and MSSA-CC130 (spa types t843, t1535, t3625 and t3256) lineages were mostly reported. Conclusion: Although the global prevalence of MRSA is low in wild animals, mecC-mediated resistance was particularly prevalent among MRSA isolates, especially among WM and WB. Considering the genetic diversity of MRSA in wild animals, they need to be monitored for effective control of the spread of antimicrobial resistance.

Keywords: wild animals, MRSA-CC398, mecC-MRSA, livestock-associated MRSA, nasal carriage, bacterial zoonosis

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) constitutes one of the major global health challenges of the twenty-first century. The holistic approach, “One Health”, is being considered as an important tool to avoid the emergence and spread of multi-drug resistant bacteria and preserve the efficacy of existing antibiotics. “One Health” is a concept of global health that emphasised the inter-relation or inter-connection of the health of humans to that of animals (pets, livestock and wild) and the environment. Among bacterial pathogens, staphylococci have been used as suitable models for “One Health” studies, as certain species and clones have been shown to “jump” across the three ecosystems of concern.

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is generally a commensal and could be an opportunistic pathogen that causes a wide variety of infectious diseases in humans and animals. This microorganism has a high impact on the general ecosystem, public health and livestock production [1]. AMR, virulence and host adaptation systems in S. aureus are of crucial public health concern in livestock, pets and wild animals as they can act as intermittent carriers or reservoirs of zoonoses [1]. Since the last decade, there is an increasing interest but little information about the global prevalence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) isolates in wild animals, despite being considered as potential reservoirs or vehicles for transmission [2].

The inter-habitat traversing and the frequent contact between wild animals, livestock and the indirect contact with humans can increase bacterial transmission and often promote the risks of colonisation and infections in humans and animals [3,4,5]. Antimicrobial-resistant bacteria spread by anthropogenic sources, such as industrial and domestic wastewater effluents, agricultural runoff and garbage, have been suspected to be the primary link to wild animals [5,6]. Once certain bacteria get transferred to wild animals, they can be responsible for the spread of many AMR genes, epidemic clones and mobile genetic elements [5,6]. Consequently, these underscore the need for the implementation of control measures against the spread of bacteria across ecosystems to limit the global emergence of novel AMR traits in the future.

MRSA is often multi-drug resistant (MDR), especially to most of the beta-lactam antibiotics (except some new cephalosporins, such as ceftaroline and ceftobiprole) as a result of the synthesis of a modified penicillin-binding protein 2 (PBP2a/c), encoded by the mec genes included in the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) [7]. The SCCmec are considered mobile genetic elements that could harbour AMR genes other than the mec [7]. The mecA gene (encoding PBP2a) has been detected in most MRSA isolates of animals, humans and the environment [8]. However, the origin and reservoir host of the mecC gene (which encodes the PBP2c) in MRSA has not been fully determined. Initially, mecC was related with livestock associated (LA)-MRSA; however, it's continued and increased detection in wild animals indicates that mecC-MRSA is primarily associated with wildlife [9]. This suggests that mecC-MRSA could be considered as wildlife-associated MRSA (WA-MRSA) [8,9].

In addition to the ability of S. aureus to acquire antimicrobial resistance determinants, this species contains an extensive number of virulence factors, ranging from the bacterial cell wall components to different exoproteins (cytotoxins, hemolysins, pyrogenic toxin superantigens and exfoliatins). Among them, deserving special attention, the Panton-Valentine Leukocidin (encoded by luk-S/F-PV) that produce the destruction of leukocytes causing necrotising pneumonia, skin and soft tissue infections. Moreover, the toxin that has been associated with toxic shock syndrome (encoded by tst) and exfoliative toxins (encoded by eta, etb, etd and etd2) produce skin lesions, as they prevent cell adhesion between keratinocytes [10]. These virulence factors contribute to the ability of this S. aureus to establish and maintain infectious diseases in humans and animals.

It has been demonstrated that S. aureus can adapt to humans and different animal species. However, some genes can facilitate its adaptation to a specific host. Thus, it has been observed that the presence of some genes (scn, chp, sak, sea/sep) allows the bacterium to survive in humans through the ability to evade the human innate immune response. These groups of genes are collectively known as IEC (immune evasion cluster). Among them, the scn gene, which encodes the Staphylococcal Complement Inhibitor (SCIN) is present in all IEC types and considered a good marker for the presence of the IEC system [11].

The ability of S. aureus to colonise and adapt to various animal hosts makes it a well-studied pathogen. Moreover, the study of S. aureus molecular ecology has provided great insight into the ability of certain bacteria clones to exhibit “inter-species animal jump or spill-over”. While some clonal complexes (CCs) of MRSA appear to be associated with certain animal hosts (for instance, MRSA-CC398 in pigs or MRSA-CC5 in poultry), other CCs such as CC1 and CC130 seem to have a wide host spectrum [12]. Among them, the MRSA-CC130, which was first linked to bovine mastitis, is very relevant in animal health and animal products [13]; however, more recently, it has been found repeatedly in wild animals and very less frequently in humans and the environment (river water), and it is largely associated with the mecC mechanism of methicillin resistance [11]. These special clones of MRSA (such as CC398 and CC130) could be transmitted across different “One Health” domains, which requires monitoring and vigilance.

Wild animals could discharge nasal and oral (saliva) secretions [14] which may constitute important transient or persistent vectors of MRSA transmission to humans and other animal species [15], depending on the extent of urban or farmland proximity and interaction [16]. Anatomically, the nasal cavity of animals has a short connection route to the trachea, similarly, the oral (buccal) cavity to the pharynx [16]. Hence, it is expected that microbes in nasal and oral cavities readily have access to the trachea and pharynx [16].

In this study, we determined the pooled prevalence of nasal, tracheal and/or oral (NTO) carriage of S. aureus and MRSA in wild animals, with a special focus on the mechanisms of methicillin resistance (mecA/mecC) in MRSA isolates, as well as the frequency of MRSA and MSSA of the lineages CC398 and CC130. Furthermore, the genetic lineages of S. aureus isolates carrying relevant virulence genes (tst, eta, etb, lukS/F-PV and scn) from eligible studies were also systematically reviewed. This study aims to comprehensively summarise and consolidate the literature on the ecology and molecular epidemiology of NTO carriage of S. aureus and MRSA in wild animals.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design

Based on the guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) (http://prisma-statement.org/PRISMAstatement/checklist.aspx, accessed on 20 August 2021), this systematic review was developed and executed on cross-sectional studies that reported S. aureus, MRSA, MSSA in the nasal, tracheal and oral cavities of wild animals. Special focus was given to mecA- and mecC-MRSA in wild animals as well as to the prevalence of CC398 and CC130 among MRSA and MSSA isolates from tested wild animals.

2.2. Articles Search Strategy

Appropriate and eligible articles published (in English) between 1 January 2011 to 30 August 2021 were searched from bibliographic databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, SciElo and Web of Science.

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

Original articles and short communications articles that provided sufficient data about the prevalence of “S. aureus nasal, oral or tracheal carriage”, “MRSA carriage”, “MSSA carriage” and “molecular typing” in all categories of wild (free-living) animals were selected and extensively reviewed. Specifically, keywords were carefully selected from the Medical Subjects Headings (MeSH) of the US National Library of Medicine (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/, accessed on 20 August 2021). These included “wild animals”, “MRSA-CC398”, “mecC-MRSA”, “livestock-associated MRSA”, “nasal carriage” and “bacterial zoonosis”. For this systematic review, four groups of animals were established with the following considerations:

Wild mammals (WM) are comprised of wild boars, red deer, Iberian ibex, deer, lynx, wild rabbits, hedgehogs, European mouflons, red foxes, common genets, bats, shrews and mustelids (otters, European badgers, beech martens, American minks and least weasels), among others. Rodents and primates were excluded from this group. This category of wild mammals has almost absolute confinement to the wildlife. However, it is hypothesised that these animals could contract MRSA from the predation of infected rodents and, in turn, spread them to humans who hunt wild animals. This is particularly possible in geographical locations with abundant forests and poor or no wildlife anti-poaching laws.

Wild birds (WB) are comprised of storks, vultures and other birds that are naturally found in the wild.

Non-human primates (NHP) are comprised of chimpanzees, monkeys, gorillas, lemurs and apes. These mammals have significant physiological and microbiota similarities to those found in humans.

Wild rodents (WR) are comprised of mice and rats, both those confined to forests and those with proximity to human settlements and agricultural farms. These animals are also mammals (small) and originate from bushes or the wild. Importantly, it is expected that they could frequently relocate and transverse into human settlements, households, farms and vice versa. Hence, they are separated from other mammals.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

(i) Studies that contained duplicate data or were overlapping articles, (ii) reviews and conference abstracts, (iii) articles that included fewer than 10 animals, (iv) studies on animals in the zoo and captivity, (v) studies on dead animals before sample collection as the time and cause of death is not certain. Moreover, dead animals might undergo some level of putrefaction that could encourage bacterial growth; thus, (vi) studies on skin, faecal and other animal samples were excluded.

2.5. Data Extraction

The following information was extracted when possible: authors, study design, study setting or location, the number of S. aureus isolates and proportion of MRSA and/or MSSA isolates, type of specimen, laboratory method employed for detection, antimicrobial susceptibility phenotypes and corresponding genotypes and molecular types of the S. aureus isolates.

Finally, 33 full texts were included because they were the only available articles that directly focused on the distribution pattern of the S. aureus, MRSA, genetic lineages, AMR phenotypes and genotypes and/or virulence genes in NTO cavities of wild animals.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The pooled prevalence of NTO carriage of S. aureus, MRSA and MSSA were calculated. MetaXL Version 5.3 (EpiGear International, Queensland, Australia) was used for all statistical analyses. Pooled prevalence analysis was based on combining the results of multiple cross-sectional studies. Specifically, it involved dividing the mean of the sum population of wild animals with S. aureus or MRSA NTO carriage by the total studied population in a homogeneous (specific) animal group.

Where possible, an analysis of pooled prevalence was carried out using the random-effects model. Moreover, the pooled rates of nasal carriage by CC398, CC1, CC130 S. aureus isolates (MRSA or MSSA) were calculated using the articles in which molecular characterisation (typing) was performed. During the univariate logistic analysis, the choice for the wild mammals’ group as the referent for comparison with other groups was conducted arbitrarily.

3. Main Findings

3.1. The Pooled Prevalence of S. aureus and MRSA Isolates

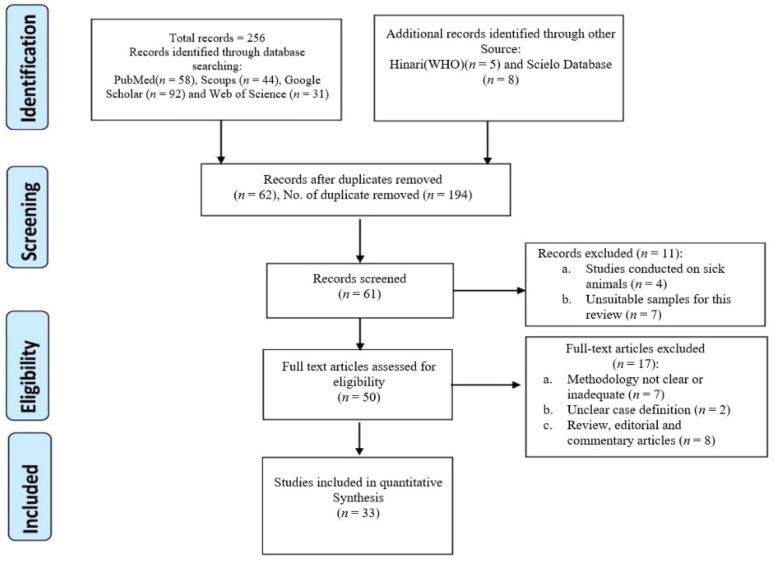

Of the 33 eligible and analysed studies (Figure 1), 6, 3, 2 and 22 were from Africa, America, Asia and Europe, respectively [5,12,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]; none were reported in Australia and the Pacific regions. Supplementary Table S1 shows the characteristics and data of the 33 eligible studies, with the indication of the country, type of animals (divided into four groups: wild mammals (WM), non-human primates (NHP), wild birds (WB) and wild rodents (WR)), number of animals tested, number of S. aureus and MRSA obtained and the AMR and virulence profiles. The pooled prevalence of NTO carriage of S. aureus and MRSA was 18.5% (range: 0–100%) and 2.1% (range: 0.0–63.9%), respectively (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Identification and selection flowchart of articles on NTO staphylococci carriage in wild animals.

Table 1.

(a) Summary of the pooled global prevalence of S. aureus and MRSA NTO carriages in the four studied wild animal groups. (b) Comparative prevalence of S. aureus and MRSA carriages between wild birds and other wild animals.

| (a) | |||||||||||||

| Study Groups | Number of S. aureus Studies Included | Total Number | Pooled S. aureus Carriage Rate (%) (Range) | OR (95% CI) | p Value | Number of MRSA Studies Included | Total Number | Pooled MRSA Carriage Rate (%) (Range) | OR (95% CI) | p Value | Total Number of Studies Included a | ||

| Animals | S. aureus | Animals | MRSA | ||||||||||

| Wild Mammals (excluding rodents and NHP) | 13 | 3031 | 479 | 15.8 (0.0–36.9) | Referent | Referent | 17 | 6110 | 99 | 1.6 (0.0–63.6) | Referent | Referent | 18 |

| Wild Rodents | 4 | 856 | 207 | 24.2 (15.3–41.0) | 1.69 (1.41–2.04) | <0.0001 | 5 | 1452 | 49 | 3.4 (0.3–4.7) | 2.12 (1.49–3.00) | <0.0001 | 5 |

| Non-human Primates | 7 | 403 | 158 | 39.2 (0.0–100.0) | 3.44 (2.78–4.29) | <0.0001 | 7 | 403 | 8 | 2.0 (0.0–26.7) | 1.23 (0.59–2.55) | 0.578 | 7 |

| Wild Birds | 5 | 586 | 60 | 10.3 (5.0–34.8) | 0.61 (0.46–0.81) | 0.0006 | 6 | 626 | 21 | 3.4 (0.0–4.0) | 2.11 (1.31–3.40) | 0.002 | 6 |

| Total Wild Animals | 29 | 4876 | 905 | 18.5 (0.0–100) | NA | NA | 35 a | 8601 | 177 | 2.1 (0.0–63.9) | NA | NA | 36 a |

| (b) | |||||||||||||

| Study Groups | Number of S. aureus Studies Included | Total Number | Pooled S. aureus Carriage Rate (%) (Range) | OR (95% CI) | p Value | Number of MRSA Studies Included | Total Number | Pooled MRSA Carriage Rate (%) (Range) | OR (95% CI) | p Value | Total Number of Studies Included a | ||

| Animals | S. aureus | Animals | MRSA | ||||||||||

| Wild Animals (excluding wild birds) | 24 | 4290 | 844 | 19.7 (0.0–100.0) | Referent | Referent | 29 | 7965 | 156 | 1.9 (0.0–63.6) | Referent | Referent | 30 |

| Wild Birds | 5 | 586 | 60 | 10.3 (5.0–34.8) | 0.46 (0.35–0.61) | <0.0001 | 6 | 626 | 21 | 3.4 (0.0–4.0) | 1.74 (1.09–2.76) | 0.019 | 6 |

a Studies that analyse either S. aureus, MRSA or both. Key: NA = not applicable; OR = odd ratio; CI = confidence interval; Significant association and effect size of S. aureus, MRSA and types of the wild animal groups determined by bivariate logistic regression (p < 0.05).

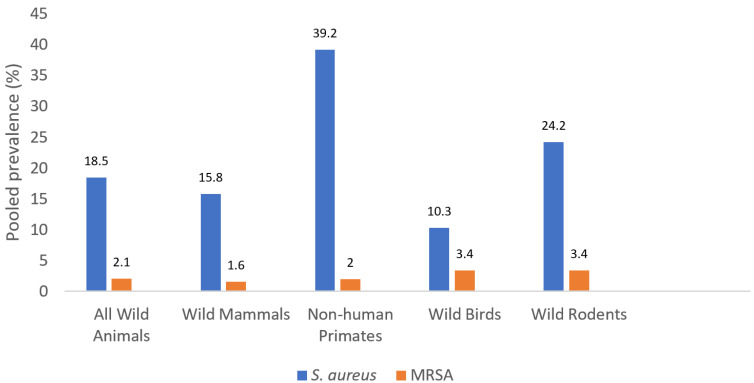

The pooled prevalence of S. aureus/MRSA in WM, NHP, WB and WR was: 15.8/1.6, 32.9/2.0, 10.3/3.4 and 24.2/3.4%, respectively (Figure 2, Table 1). There were significant associations between wild animal types and the prevalence of S. aureus and MRSA (p < 0.05), except in the case of MRSA in WM and NHP (p = 0.578) (Table 1). In this sense, the prevalence of MRSA among WB and WR was higher than the one of WM. Moreover, WB had a significantly higher prevalence of MRSA when compared to other wild animals put together (p = 0.019) (Table 1).

Figure 2.

The pooled prevalence of S. aureus and MRSA NTO carriage among wild animal groups.

3.2. Prevalence of mecC-MRSA Isolates and Specific Genetic Lineages (CC398, CC130) in the Four Groups of Wild Animals

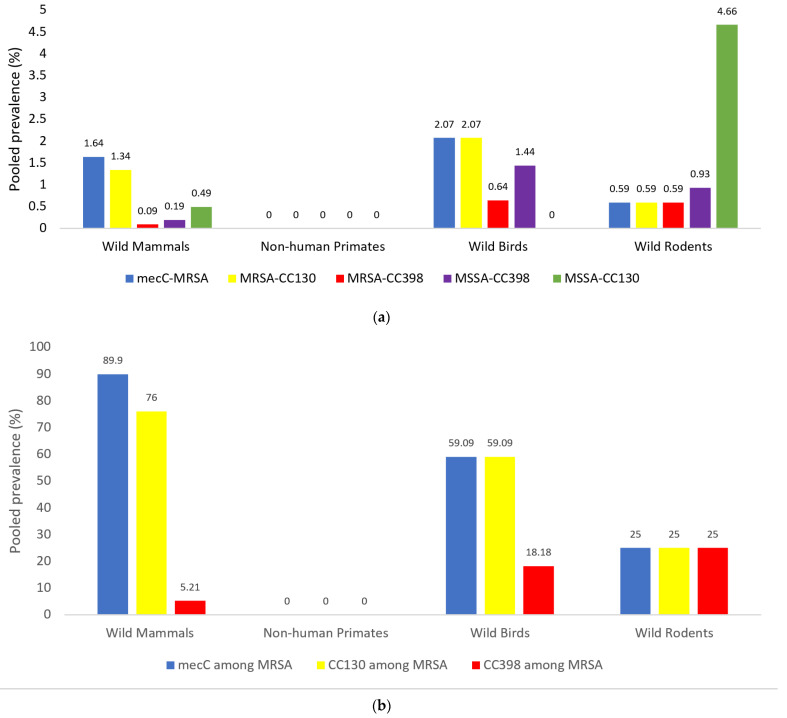

Figure 3a shows the pooled prevalence of mecC-MRSA, MRSA-CC398, MRSA-CC130, MSSA-CC130 and MSSA-CC398 in the four groups of wild animals analysed. In addition, Figure 3b shows the prevalence of the mecC gene as well as of CC398 and CC130 lineages among the MRSA isolates obtained from the four studied groups of wild animals (using the articles in which genetic lineages are studied). As it is shown, mecC-MRSA has been reported in WM, WB and WR in low percentages (1.64, 2.07 and 0.59%, respectively) (Figure 3a); nevertheless, the mechanism mecC is predominant among the MRSA isolates recovered from WM (89.9%) and WB (59.1%), with relatively lower pooled prevalence in WR (25.0%) (Figure 3b). The pooled prevalence of MRSA-CC130 among WM, WB and WR groups was 76.0, 59.1 and 25.0%, respectively (Figure 3b). These corresponded to data obtained for mecC-MRSA because most of the mecC-MRSA belonged to this genetic lineage (except for some mecC isolates of the WM group).

Figure 3.

(a) The pooled prevalence of mecC-MRSA, MRSA-CC130, MRSA-CC398, MSSA-CC398 and MSSA-CC130 among S. aureus (MRSA and MSSA) isolates in wild animals of the four studied groups analysed. (b) Pooled prevalence rates of mecC-positive, CC130 and CC398 isolates among MRSA isolates in wild animals from the four studied groups of wild animals. Note: The number of studies per group was as follows: wild mammals (10), non-human primates (4), wild birds (6), wild rodents (4). Some studies recruited more than one animal group.

The prevalence of MRSA-CC398 was higher in WB (0.64%) and WR (0.59%), in relation to WM (0.09%) (Figure 3a). If we consider the MRSA isolates of wild animals, the CC398 clone was detected in 25.0% of MRSA isolates of WR, 18.18% of WB and 5.21% of WM (Figure 3b).

In relation to MSSA-CC398 isolate, they were detected among WB (1.44%), WR (0.93%) and WM (0.19%), but not among NHP. Moreover, MSSA-CC130 was only reported in WR (4.66%) and WM (0.49%) (Figure 3a). MRSA-CC398 and MRSA-CC130 were mostly reported in wild animals of the European countries and China (Supplementary Figure S1).

3.3. Characteristics of mecC MRSA Isolates from NTO Cavities of Wild Animals

The mecC-MRSA isolates were detected in ten of the eligible studies related to NTO-carriage, with a total of 106 isolates (Table 2). The mecC-positive isolates were in most cases of the clonal complex CC130 (ST130, ST1945, ST3061, ST1583), although isolates of CC2361 and ST2620 lineages were also reported among wild hedgehogs and European otters, respectively [31,34] (Supplementary Table S2), The predominant spa-types among the mecC -positive isolates were t843 (55.5%) and t1535 (15.3%), both associated with CC130. However, 10 other spa-types were detected in the remaining mecC-positive isolates: (a) t3256, t10751, t10513, t10893 and t11015 associated with CC130, (b) t4335, associated with CC2620 and (c) t978, t3391, t9111 and t15312 associated with CC2361 (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 2.

Genetic lineages, AMR, virulence genes and IEC system in mecC-MRSA isolates detected in NTO S. aureus carriage studies in wild animals.

| Reference | Animal Species (Location) | No. of Animals Tested | No. of S. aureus | No. of mecC-MRSA (% Colonised Animals) | spa-type/ST/CC (Number of Isolates) | AMR Phenotype for Non-Beta-Lactams of mecC-MRSA | IEC-type in mecC-MRSA (Number Isolates, spa) | Other Virulence Genes in mecC-MRSA Isolates (Number Strains) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [12] | Wild free-living rodents (Germany) | 145 | 37 | 1 (0.7) | t843 (1)/CC130 (1) | Susceptible (all) | IEC-negative (1) | NT |

| [17] | Wild rodents (Portugal) | 204 | 38 | 3 (1.5) | t1525 (3)/ST1945 (3)/ CC130 (3) | Susceptible (all) | IEC-E (3, t1535) | Negative (for lukS/F-PV, hla, hlb, eta, etb, tst) (3) |

| [19] | Red deer (Spain) | 65 | 16 | 11 (16.9) | t843 (4), t1535 (7)/CC130 (11) | Susceptible (all) | IEC-E (11, t843, t1535) | etd2 (11) |

| [22] | Wild rodents and shrews (Germany, Czech and France) | 295 | 45 | 1 (0.3) | t843 (1)/CC130 (1) | Susceptible (all) | IEC-negative (1) | Negative (for lukS/F-PV, sea-seu, tst, eta, etd) (1) |

| [23] | European hedgehog, European rabbit, red deer, wild boar, European mouflon (Spain) | 103 | 23 | 3 (2.9) | t843 (3)/ST130 (3)/CC130 (3) | Susceptible (all) | IEC-negative (3) | seg (1), seh (1). Negative for lukS/F-PV, tst, eta, etb, and 18 enterotoxin genes |

| [29] | Rabbit and hare (Spain) | 363 | 70 | 34 (9.3) | ST1945 (33), ST5823 (1)/CC130 (34) | Susceptible (all) | IEC-negative (34) | NT |

| [31] | European brown hare, European otter, European hedgehog, Eurasian lynx (Germany) | 40 | 5 | 5 (12.5) | t843 (2), t10513 (1), t3256 (1), t4335 (1)/ST2620 (1). ST130 (4)/CC130 (5) | NT | NT | NT |

| [34] | Wild hedgehog (Sweden) | 55 | 35 | 35 (63.6) | t843 (17), t10751, t978 (3), t9111 (3), t15312 (4), t3391 (5), t10893 (1), t11015 (1)/CC130 (20), CC2361 (15) | CIP (5), CLI (6), ERY (5), GEN (7), KAN (5), TET (2) | NT | NT |

| [37] | Stork (Spain) | 92 | 32 | 1 (1.1) | t843 (1)/ST3061 (1)/CC130 (1) | Susceptible (all) | IEC-negative (1) | etd2 (1) |

| [38] | Cinereous vulture and magpie (Spain) | 324 | 15 | 12 (3.7) | t843 (11), t1535 (1)/CC130 (12) | Susceptible (all) | IEC-E (4, t843) IEC-negative (8, t843 and t1535) |

Negative (for lukS/F-PV, tst, eta, etb, and etd) (12) |

Key: NT: not tested; CLI: Clindamycin; CIP: Ciprofloxacin; ERY: Erythromycin; GEN: Gentamicin; KAN: Kanamycin; TET: Tetracycline.

Out of the 10 studies on mecC-MRSA, the IEC system was analysed in 8 studies with a total of 66 isolates included. Only 3 of these studies reported the presence of IEC-positive isolate, which corresponded to 18 isolates of the 66 tested (27.3%); they were of the spa-types t843 (n = 8) and t1535 (n = 10) (Table 2), and all were IEC-type E; they were obtained from red deer, vultures and magpies of Spain and wild rats of Portugal [17,19,38].

Besides the penicillin, oxacillin and cefoxitin resistance, most of the mecC-MRSA strains were susceptible to all the non-beta-lactam antimicrobials tested (101/106, 95.6%) (Table 2). Only one study reported the detection of a few mecC-MRSA isolates that were resistant to ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, clindamycin, gentamicin, tetracycline and/or kanamycin, although the mechanisms implicated were not evaluated [34] (Table 2). The etd2 was detected in the 12 mecC-MRSA isolates in which this gene was analysed (Table 2).

3.4. Characteristics of S. aureus-CC398 Isolates Detected from NTO Cavities of Wild Animals

The MRSA-CC398 isolates were detected in seven studies among NTO samples of wild animals (n = 14 isolates) and corresponded to the sequence types ST398 and ST1232 and the spa types t011 (60% of isolates), as well as to t899, t034, t1451, t4552 and t2582 (Supplementary Table S2 and Table 3). In the case of MSSA-CC398 (n = 19 isolate), the predominant spa-types were t571 and t1451 (68.2%), but t034, t6606 and t3625 were also reported.

Table 3.

Genetic lineages, AMR, virulence genes and IEC system in MRSA- and MSSA-CC398 isolates detected in NTO carriage studies in wild animals.

| Reference | Animal Species (Location) | No. of MRSA-CC398 | spa/ST of MRSA-CC398 (Number of Strains) | IEC-type (Number of Strains) in MRSA-CC398 | AMR Phenotypes/Genes (Number Strains) of MRSA-CC398 | Other Virulence Genes (Number Strains) of MRSA-CC398 | No. of MSSA-CC398 (%) | spa/ST of MSSA-CC398 (Number of Strains) | IEC-type (Number of Strains) in MSSA-CC398 | AMR Phenotypes/Genes (Number Strains) in MSSA-CC398 | Other Virulence Genes (Number Strains) in MSSA-CC398 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | Iberian ibex, red deer and wild boars (Spain) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3 | t034 (2), t571 (1)/ST398/CC398 | NT | TET (3) | NT |

| [17] | Wild rodents (Portugal) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 6 | t1451 (5), t571 (1)/ST398 (4), ST5926 (2) | IEC-C (2), IEC-negative (4) |

Susceptible (all) | hld (all) |

| [18] | Wild boars (Portugal) | 1 | t899/ST398 | IEC-B (1) | TET, PEN FOX, OXA, CIP/mecA | NT | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [21] a | Wild mammals (Spain) | 3 | t011 (2), t1451 (1)/ST398 (3) | NT | TET (3), CIP (2), ERY (1), CLI (1) | NT | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [21] a | Eurasian griffon vulture (Spain) | 2 | t011 (2)/ST398 (2) | NT | TET (2), CIP (1), ERY (1), CLI (1) | NT | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [25] | Wild boar (Spain) | 1 | t011/ST398 (1) | IEC-negative (1) | PEN- FOX- TET/blaZ, mecA, tet(M), tet(K) | Negative (for lukS/F-PV, tst, eta, and etb) (1) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [33] | Wild boar (Germany) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | t571 (1)/ST804 (1) | NT | AMP (1), ERY (1)/blaZ | Negative (for sea, seb, sec, sed, see, she, eta, etb, tst, luk-S/F-PV) (1) |

| [37] | Stork (Spain) | 1 | t011 (1)/ST398 (1) | IEC-negative (1) | PEN, OXA, FOX, TET/mecA, tetK, tetM | cna (1) | 9 | t571 (5), t6606 (3), t3625 (1)/ / ST398 (8), ST2377 (1) | IEC-C (9) | PEN (all), ERY (all), CLI (all)/ blaZ, erm(T) | cna (all) |

| [38] | Cinereous vulture (Spain) | 1 | t011 (1)/ST398 (1) | IEC-negative (1) | PEN, FOX, ERI, CLI, TET/mecA, blaZ, erm(C), vga(A), tetK, tetM | Negative (for lukS/F-PV, tst, eta, etb, and etd) (1) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [39] | Rodents (China) | 5 | t034 (1), t011 (1), t4552 (1), t2582 (2)/ST398 (4), ST1232 (1) | IEC-E (1), IEC-A (1) IEC-negative (3) |

TET (2), AZM (1), CLI (1) | lukS/F-PV (1, spa t034) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Key: NT = not tested; NA: not applicable; ST = sequence type; CC = clonal complex; AMP: Ampicillin; AZM: Azithromycin; CLI: Clindamycin; CIP: Ciprofloxacin;; ERY: Erythromycin; FOX: Cefoxitin; OXA: Oxacillin; PEN: Penicillin; TET: Tetracycline; a studies on more than one animal group.

Most of the MRSA-CC398 isolates characterised were IEC-negative (6/9, of spa-types t011, t2582 and t4652), although some IEC-positive isolates were also reported among wild boar (spa-type t899-IEC-type B) or rural rodents (spa-t011-IEC type A and spa-type t034-IEC-type E) (Table 3). In relation to MSSA-CC398, a total of 15 isolates were characterised for the IEC system and most of them were IEC-type C (11/15, of spa-types t571, t1535, t3625 and t6606), although some few IEC-negative isolates were also found in one study (t1451, t571) (Table 3).

Most MRSA-CC398 isolates showed tetracycline resistance (80%). Nevertheless, three MRSA-CC398 isolates obtained from wild rodents in China were tetracycline-susceptible (spa-types t4652 and t2582) and, interestingly, one isolate of this study carried the genes of the Panton-Valentine Leukocidin (spa-t034 and IEC-type E) [39]. In relation to the antibiotic resistance profile of the MSSA-CC398 isolates, this was determined in 16 of these isolates and erythromycin resistance was found in 10 isolates carrying the ermT gene in 9 of them. Phenotype of complete susceptibility to all the tested antibiotics was identified in 5 of the 16 MSSA-CC398 isolates (Table 3). The MSSA-CC398 isolates were detected in wild birds and rodents (Supplementary Table S2). None of the studies on NHP reported the detection of the mecC-MRSA, MRSA-CC130, or MRSA-CC398 (Figure 3a,b).

3.5. Characteristics of Other S. aureus Lineages Detected from NTO Cavities of Wild Animals

In addition to the MRSA-CC130 (and other mecC-MRSA isolates), MSSA-CC130 isolates (mostly of spa types t843 and t1535) were reported (Supplementary Table S2). In addition, other clonal complexes of MRSA, such as the CC5, CC88 and CC133, were found in NTO S. aureus isolated from various wild animals (Supplementary Table S2).

MRSA isolates of the genetic lineage CC1 were only reported among WM, although with a low pooled prevalence (0.04%), representing 2.1% of total MRSA isolates in this group of wild animals. Specifically, the MRSA-t127-CC1 clone was reported in two studies of wild mammals [21,23] with a pooled prevalence of 0.037%. Conversely, the MSSA-t127-CC1 was detected from four studies on WM and NHP [5,25,45,46] (Supplementary Table S2).

3.6. Antibiotic Resistance and Virulence Genes Detected from S. aureus of NTO Cavities of Wild Animals

Penicillin resistance and the blaZ gene were the most predominant traits of AMR in both MSSA and MRSA isolated from NTO cavities of wild animals (reported in 13 studies). Other antibiotic resistance genes (fexA, str, fosB, sdrM, aacC-aphD, erm(C), aph(30)-IIIa, tetM, tetK, and aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia) were reported in at least one of the studies which tested for these genes (Supplementary Table S1). Although two studies phenotypically detected resistance to linezolid [18,47], only one study reported the presence of a mutation [A29V] in L22 and an insertion [68KG69] in L4 ribosomal proteins as the molecular mechanism implicated; no linezolid transferable resistance genes were detected in these studies (Supplementary Table S1).

Genes associated with several virulence factors, including leukotoxins and enterotoxins, were reported in some of the reviewed and eligible studies (Table 4). The Panton-Valentine Leucocidin (PVL) gene, luk-S/F-PV, was detected in 4 of 33 studies of NHP and WR (5 isolates); PVL-positive isolates detected corresponded to the clonal complexes CC398 (1 MRSA), CC5 (1 MRSA) or CC22 (3 MRSA) (Table 4). Among all eligible studies, eight isolates (five MRSA and three MSSA, of lineages CC5, CC22, CC30 and CC522) were positive for the tst gene, encoding the toxic shock syndrome toxin (TSST), and they were obtained in all four studied groups of animals (Table 4). Moreover, several enterotoxin genes (sea, seb, sed, sec and sep) and exfoliative toxin genes (eta, etb, etd2) were detected in five studies. Some studies detected genes encoding other virulence factors, such as hla and hld (haemolysins).

Table 4.

(a) Studies in which the TSST-1, PVL and IEC encoding genes were analysed among S. aureus isolates. (b) Characteristics of S. aureus isolates carrying lukS/F-PV, tst or eta virulence genes.

| (a) | |||||||||

| Reference | Animal Species | No. of Animals Tested/S. aureus/MRSA | No. of tst (%) in MRSA | No. of tst (%) in MSSA | No. of lukS/F-PV (%) in MRSA | No. of lukS/F-PV (%) in MSSA | No. Strains with IEC (%) in MSSA | No. Strains with IEC (%) in MRSA | No. of S. aureus IEC-Negative (%) |

| [12] | Wild free-living rodents | 145/37/2 | 1 (50.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | IEC-E, 1 (50.0) | 36 (97.3) |

| [17] | Wild rodents | 208/38/6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | IEC-E, 1 (3.1) | IEC-E, 3 (50.0) | 31 (81.6) |

| IEC-C, 2 (6.2) | IEC-A, 1 (16.7) | ||||||||

| [18] | Wild boars | 45/15/1 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | IEC-B, 1 (100.0) | 14 (93.3) |

| [19] | Red deer | 65/16/11 | 0 | NT | 0 | NT | NT | IEC-E, 11 (100.0) | 5 (31.3) |

| [23] | Wild mammals | 103/23/4 | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 (100.0) |

| [37] | Storks | 92/32/3 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.9) | 0 | 0 | IEC-B, 6 (20.7) | 0 | 5 (15.6) |

| IEC-C, 11 (37.9) | |||||||||

| IEC-D, 1 (3.4) | |||||||||

| IEC-G, 9 (31.0) | |||||||||

| [38] | Wild birds | 324/15/13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | IEC-E, 1 (50.0) | IEC-E, 4 (30.8) | 10 (66.7) |

| [39] | Urban rodents | 212/87/11 | NT | NT | 2 (18.2%) | NT | NT | IEC-E, 1 (9.1), IEC-IEC-G, 1 (9.1) | NT |

| IEC-B, 1 (9.1) | |||||||||

| IEC-A, 2 (18.2) | |||||||||

| [42] | NHP | 132/15/0 | ND | Present but number not specified | Present but number not specified | 0 | 0 | NT | NT |

| [43] | NHP | 62/36/0 | NT | 0 | 0 | 10 (27.8) | NT | NT | NT |

| [46] | NHP | 95/58/0 | NT | 0 | 0 | 2 (3.4) | NT | NT | NT |

| [47] | NHP | 59/29/4 | 3 (75.0) | NT | 3 (75.0) | 0 | 0 | IEC-E, 3 (75.0) | 26 (89.7) |

| (b) | |||||||||

| Reference | Origin of Isolates | Spa-type/ST/CC of Positive Isolates (No. of Isolates) | Virulence Gene | Methicillin Resistance Phenotype | IEC-type (Number of Strains) | ||||

| [12] | Germany/Rodent/Nasal | t684/CC30 (1) | tst | MRSA | E (1) | ||||

| [23] | Spain/Wild boar/Nasal | t1534/CC522 (1) | tst | MSSA | IEC-negative | ||||

| [37] | Spain/Storks/Trachea | t012/CC30 (2) | tst | MSSA | D (1) | ||||

| [47] | Nepal/NHP/Oral | ST22 (3) | tst | MRSA | E (3) | ||||

| [37] | Spain/Stork/Trachea | t209/CC5 (1) | eta | MSSA | B (1) | ||||

| [39] | China/Wild Rodents/Nasal | t034/ST1232/CC398 (1) | luk-SF-PV | MRSA | G (1) | ||||

| t127/ST1/CC5 (1) | |||||||||

| [43] | Zambia and Uganda/NHP/Nasal | ST80 (9) | luk-SF-PV | MSSA | NT | ||||

| ST2178 (1) | |||||||||

| [46] | Gabon and Cote d’ Ivoire)/ NHP/Nasal | ST1855 (1) | luk-SF-PV | MSSA | NT | ||||

| ST 1928 (1) | |||||||||

| [47] | Nepal/NHP/Oral | ST22 (3) | luk-SF-PV | MRSA | E (3) | ||||

Key: NT = not tested; TSST-1 = toxic shock syndrome toxin-1; IEC = immune evasion cluster; PVL = Panton Valentine Leucocidin. (b) NT: not tested; ST: sequence type; CC: clonal complex. Note: In the IEC system, the presence of scn is found in all IEC types and frequently utilised as the determinant for IEC-positive S. aureus isolates. Essentially, the presence of ≥2 of the 5 genes associated with the IEC determines the IEC type of the S. aureus isolate. There are seven IEC types (A to G) depending on the combination of scn, chp, sak, sea/sep genes: IEC-type A (sea, sak, chp, scn), IEC-type B (sak, chp, scn), IEC-type C (chp, scn), IEC-type D (sea, sak, scn), IEC-type E (sak, scn), IEC-type F (sep, sak, chp, scn) and IEC-type G (sep, sak, scn).

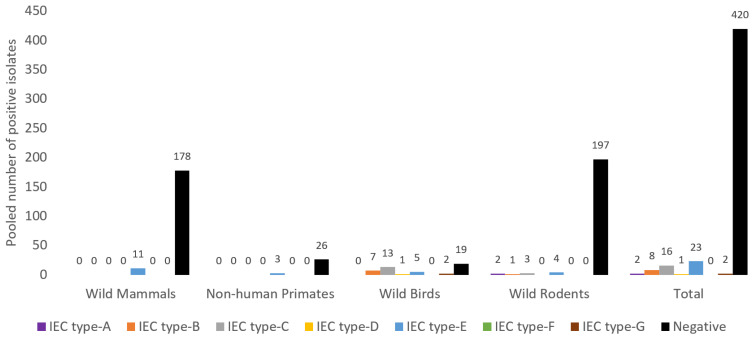

Out of the total of 472 S. aureus isolates from NTO cavities of wild animals tested for the IEC system, 52 were positive (11.0%) and the remaining were IEC-negative (n = 420, 89.0%) (Figure 4). Considering the different groups of animals, WB had the highest frequency of IEC-positive isolates (n = 28, 59.6%), then NHP (n = 3, 10.3%), WM (n = 11, 5.8%) and least in WR (n = 10, 4.8%). Moreover, the IEC-type E was the most frequently detected among the IEC-positive isolates (44.2%), representing 4.9% of the S. aureus IEC-tested isolates (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Immune evasion cluster (IEC) type distribution in S. aureus isolates from wild animal groups analysed in this study. Note: There were four studies from rodents, one from NHP, two from wild birds and six from wild mammals with IEC analysis (data extracted from Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4).

4. Discussion

The human-animal-environment interface (One Health) approach is very fundamental to addressing the threat of AMR, its dissemination and the risks to public health. Although “One Health” research is not yet a priority of many countries, it provides significant data to better understand the global health of humans, animals and their environment [48].

The nasal and oral microbiome ecology has attracted a lot of interest in understanding the scope of AMR, especially in migratory birds. Migratory birds are a type of wild bird that can move a very long distance across several countries. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive synthetic and systematic review on the NTO S. aureus and MRSA carriage in free-living wild animals. This article provides the NTO S. aureus carriage prevalence and pattern across the four major groups of wild animals throughout all the continents of the world. Previous work by Silva et al. [49] was a narrative review focused on the European continent and it dwelled on all types of animal samples (such as skin, faeces and rectal swabs that may have a significant risk of S. aureus infection instead of colonisation).

With a global pooled prevalence of 18.5% S. aureus NTO carriage in wild animals detected in our review, it can be inferred that this value is slightly higher than those reported in systematic reviews on healthy humans without occupational risk of colonisation (15.9%) and companion animals (17.5%) [50,51]. However, the prevalence of S. aureus NTO carriage greatly varies with the category of wild animals and the highest pooled S. aureus prevalence was obtained from NHP (32.9%) and least in wild birds (10.3%) (Table 1). The NHP are the closest to humans in respect of microbiota and other physiological compositions. As such, they are expected to have a relatively high rate of S. aureus NTO carriage.

Few eligible cross-sectional studies on S. aureus/MRSA NTO carriage in primates have been published [41,42,43,44,45,46,47], and most of them have been performed in the African continent. Some other studies were carried out on captive primates for research, breeding and zoological facilities, but these studies were excluded in this review due to the perceived eventual possibility of contracting S. aureus from humans as they interact with the primates during day-to-day feeding activities. Conversely, wild birds had the least prevalence of S. aureus NTO carriage (10.3%). This is relatively low when compared to other categories of wild animals. The reason for this low data has not been fully elucidated. However, it appeared that S. aureus is not often the staphylococcal species associated with the nasotracheal carriage in wild birds (excluding birds of prey) [52]. Moreover, it could be that most of the studied birds had a feeding lifestyle that seldom allows S. aureus carriage, as in the case of birds that feed in the natural or semi-natural environment as opposed to those that feed close to landfills [37].

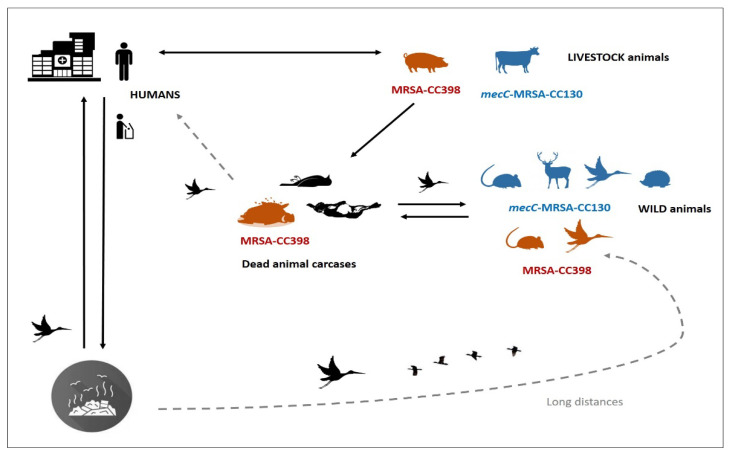

In the study of Ruiz-Ripa et al. [52], about 48.8% of storks showed S. sciuri tracheal carriage. However, Gómez et al. [37] reported as high as 34.8% S. aureus carriage in white stork nestlings exposed to human residues. So, human residue/garbage (that could be contaminated by S. aureus) serves as the major source of food for wild birds (mostly aerial and arboreal), especially migratory birds (such as storks). Conversely, birds of prey such as vultures have shown relatively lesser tracheal S. aureus carriage (4.6%) than storks [38]. This difference could be due to variation in feeding habits and food preferences by the birds at the time of sample collections. Moreover, some wild birds feed on dead animal carcases (such as wild boars) that could be colonised by certain S. aureus clones. This could be one of the reasons certain wild birds often carry S. aureus-CC398 (LA-MRSA) clones mainly adapted to pigs and wild boars [12,25]. Nevertheless, wild birds (especially the migratory ones) can carry pathogens over long distances, thus facilitating pathogen dissemination among human and animal populations [53].

Based on our systematic review of pooled data, pooled NTO MRSA carriage on wild animals was low (2.1%), although few differences were observed depending on the group of animals tested, with slightly higher rates detected in WB and WR (3.4% each) and lower in WM (1.6%) or NHP (2.0%) (Table 1). It is important to remark that there were few heterogeneous studies which make it difficult to reliably assess the statistical differences across the wild animal groups.

Considering the studies in which the mechanisms of methicillin resistance (mecA or mecC genes) or the genetic lineages of MRSA isolates were analysed, the mecC-MRSA was preferentially detected in WB (2.07% of animals tested) and in wild mammals (1.64%), with lower prevalence in wild rodents (0.59%) and no detection in NHP studies. Moreover, the MRSA-mecA-CC398 lineage was detected more frequently among wild birds and wild rodents (0.59–0.64%) and lower in wild mammals (0.09%), with no detection on NHP. Interestingly, most MRSA isolates of wild mammals (95%) and wild birds (77%) and 50% of those of wild rodents were typed as mecC-MRSA (mostly of lineage CC130) or MRSA-CC398. Put together, it seems that wild animals, especially wild mammals/birds, are natural reservoirs of mecC-MRSA-CC130 isolates (supporting its consideration as WA-MRSA) and wild rodents/birds are frequent carriers of the MRSA-CC398 clone (Figure 5). The very high prevalence of mecC-MRSA (63.6%) among wild hedgehogs reported in Sweden is of special relevance [34].

Figure 5.

Transmission cycle of special MRSA clones across humans, animals (livestock and wild) and the environment (such as landfills and hospitals). Note: In the silhouettes with colours, the animals in which MRSA-CC398 (red) and mecC-MRSA-CC130 (blue) isolates have been detected in high prevalence were illustrated.

Diverse spa-types have been detected among MRSA-CC398 isolates, although t011 was the predominant one (60%), highly associated with livestock farming [54]. This spa-type was the unique one among MRSA-CC398 in wild birds but was detected combined with other spa types in MRSA of wild mammals and wild rodents (Supplementary Table S2). It is interesting to remark that MSSA-CC398 was detected in wild birds, wild rodents and wild mammals (0.19–1.44%), of which spa types t571 and t1451 were predominant. However, t034, t6606 and t3625 were detected in lesser frequencies [5,17,37].

The spa types t843 and t1535 were the predominant ones among mecC-MRSA-isolates, although many other spa types were detected. These spa types were also the most frequently detected in food-producing animals or human mecC-MRSA infections [55]. Both lineages, t843/CC130 and t1535/CC130, have also been found among MSSA isolates of wild boar [23,25] and in free-living wild rats [12].

It has been suggested that there might be a mutual exchange of mecC-MRSA between livestock and wild animals since it was thought that CC130 originated in ruminants [56]. Most of the mecC-MRSA isolates of wild animals included in this review showed susceptibility for non-beta-lactam antibiotics, with a few exceptions (Table 2). This feature was also previously found in mecC-MRSA isolates obtained in human infections [55]. Resistance for non-beta-lactam antibiotics was detected in mecC-MRSA recovered from wild hedgehogs in Sweden [34].

Another aspect of interest is the presence of the IEC system (associated with human adaptation) in the mecC-MRSA isolates. The demonstration of scn gene in wild animals can represent S. aureus NTO carriage by a human-adapted strain and could suggest reverse-zoonosis (zooanthroponosis). However, the absence of the IEC gene (with the scn marker), can denote a non-human strain and represent a key evolutional event [11]. In this respect, most of the mecC-MRSA isolates (72.7%) were IEC-negative; nevertheless, 27.3% were IEC-type E positive. These strains presented the spa-types t843 and t1535 and were recovered of red deer, vultures, magpies and wild rodents in Spain and Portugal [17,19,38]. As indicated before, the detection of IEC genes often highlights possible human adaptation. However, it has been proposed that IEC-type E might be a conserved feature of ST1945-MRSA isolate as studies from Spain and Portugal reported IEC-type E in mecC-MRSA-ST1945 isolates [17,19,38]. In our systematic review, a pooled prevalence of 27.3% mecC-MRSA-IEC-type E positive strains was obtained from eight eligible studies on wild animals (Table 2). This value is relatively high and indicates that IEC-positive-mecC-MRSA in the general ecosystem deserves to closely be monitored.

Most of the available mecC-MRSA articles in which IEC genes were studied in human infections [55,57], livestock and milk samples [58], river water [59] and even other animals’ faecal and skin samples [60] were IEC-negative; nevertheless, the detection of mecC-MRSA-ST1945-IEC-positive strain of human origin, that was type E, has been reported [61]. Similarly, Gómez et al. [62] found mecC-MRSA-CC130-IEC-type E strains from rat faecal samples. Moreover, one scn-positive MSSA-CC130 isolate was reported by Silva et al. [17]. In all studies in which the etd2 was analysed in the mecC-MRSA isolates, this toxin gene was detected. This gene was found in the genome of all CC130 isolates (both mecC-MRSA and MSSA) analysed in one study which suggests that etd2 could be intrinsic for this genetic lineage [11].

As expected, most of the MSSA isolates from wild animals had low-level AMR. The great majority of the isolates were susceptible to all tested antibiotics (Supplementary Table S1). This low prevalence of AMR in wild animals could be because these animals do not directly encounter antibiotics and have no evolutionary selective pressure [33]. Although the presence of AMR in wild animals depends on the location where they are found and the category of animals, some studies have identified wild animals with apparently no contact with antibiotics to be colonised with S. aureus with certain AMR genes [37,38,47,60]; therefore, MRSA NTO carriage in wild animals may be considered a sentinel of AMR. The most frequently detected AMR in MSSA was for penicillin (Supplementary Table S1). As shown in Table 3, all MRSA-CC398 isolates included in this review showed tetracycline resistance and, when tested, carried the tetM gene (and, in many cases, also tetK). This phenotypic/genotypic characteristic has been proposed as a marker of the MRSA-CC398 clone in different studies [63,64].

Since its discovery in the early 2000s to date, MRSA-CC398 has consistently been detected in humans with contact with farm animals and in a wide variety of animals (especially in pigs) and their environments. However, lately, the MSSA-CC398 strains have also attracted interest for epidemiological and evolutionary purposes and because MSSA-CC398 strains could be implicated in emergent invasive human infections [65]. In this review, it appears that storks and rodents could be the major wild animal reservoirs of this MSSA genetic lineage (mainly with the spa type t571) [17,37]. It is worthy to remark that MSSA-CC398 isolates have been recovered from other animals, such as the aquatic ones [63,66]. From the phylogenetic and evolutionary point of view, the CC398 lineage of S. aureus was postulated to have two separate host sub-clades: (a) a livestock associated-clade in which S. aureus-CC398 carries the mecA and tetM genes and lacks the scn gene (associated to phage φ3-Sa) and (b) a human associated-clade (MSSA) carrying scn (human adaptation gene) but no tetM [64]. Various sub-clades have emerged and spread across different animals, animal products (e.g., meat) and countries and continents [54].

The detection of MRSA-CC1 in wild boars and rabbits shows that this clone has a clear potential of establishment and spread in the wild and perhaps transmission into livestock farms and the urban community. Aside from these genetic lineages, MSSA-CC425 was also detected in 13.7 and 24.4% of wild boars by Mama et al. [25] and Seinige et al. [33], respectively, and wild birds [38]. Similarly, MSSA-CC1 strains were often reported from the nasal cavities of NHP in sub-Saharan Africa [42,43,46]. ST425/CC425 is a genetic lineage with a pattern of transmission that has been attributed to wild animals NTO colonised through the ingestion of secretions from carnivorous animals (e.g., foxes) [67]. Thus, the report of MSSA-ST425 from the wildlife deserves to be monitored.

Aside from methicillin resistance, resistance to linezolid (one of the last resort antimicrobial agents) was reported in one MRSA-ST2328 isolate of wild boar [18] and two MRSA-ST22/ST88 isolates of monkeys [47]; although transferable linezolid resistance genes were not detected in these isolates, mutation and insertion in L22 and L4 ribosomal proteins, respectively, were detected [47] (Supplementary Table S1). The detection of linezolid-resistant S. aureus isolates carrying the ribosomal mutation, which confers a very high resistance level for linezolid, is relevant, although it has no capacity for horizontal transference [68].

The lukS/F-PV virulence gene was rarely reported in S. aureus of wild animals; however, five studies detected PVL-positive MRSA and MSSA isolates from NHP and WR [39,42,43,46,47]. Interestingly, most of the PVL-positive isolates were detected in MSSA or MRSA in NHP [42,43,46,47], although there is one study performed on urban rodents in China which detected the PVL-positive-MRSA-CC398-t034 isolate [39]. It is worthy to mention that MRSA strains in rats in contact with cattle can be colonised by LA-MRSA [12]. Moreover, the LA-MRSA-PVL positive strains deserve to be meticulously monitored. This suggests that PVL-carrying S. aureus derived from NTO cavities of NHP and rodents may play a role as maintenance hosts or vectors for MRSA, which is important to human health. PVL is a significant pore-forming toxin that is often associated with abscesses. S. aureus carrying PVL appears to be endemic in humans in sub-Saharan Africa [50]. However, its role in some wild animals (as NHP and urban rodents) needs to be studied in detail. Perhaps, these animals have different selection pressure for PVL-positive S. aureus isolates.

Similarly, the tst gene encodes the pyrogenic toxin superantigen TSST-1, one of the most important virulence proteins of S. aureus that produces limited or systemic infections. This gene is located on staphylococcal pathogenicity islands that facilitate S. aureus immunopathogenesis through the secretion of anti-inflammatory chemokines and induction of immunosuppression [69]. The TSST-1 is often mobilised and elaborated with the help of many bacteriophages [70]. The tst gene has been detected in MSSA or MRSA isolates in five studies of wild mammals, wild birds and NHP (Table 4).

Despite the comprehensiveness of this article in providing updated data on S. aureus and MRSA nasal, oral and tracheal carriage of wild animals, it is necessary to interpret these data with caution, as the pooled prevalence generated from the animal groups and continents may not be the absolute measure of the extent of the genetic lineages, AMR and virulence factors of S. aureus in these entities.

5. Conclusions

Although the global prevalence of MRSA is low in wild animals, the mecC-mediated mechanism was particularly prevalent among MRSA isolates (especially among those of wild mammals and birds). Moreover, the global prevalence of MRSA-CC398 lineage was low in wild animals but its prevalence among MRSA was relatively high, especially in wild birds. The NTO cavities of wild animals are potential vehicles of S. aureus/MRSA transmission, but the extent appears to vary according to the animal type and geographic location of studies. Findings from this systematic review showed that wild animals could carry AMR, virulence genes and genetic lineages of human, agricultural and epidemiological importance across the “One Health” domains. Particularly, the reports of lukS/F-PV, tst and linezolid resistant carrying MRSA are of great concern. Considering the genetic diversity of MRSA in wild animals, they need to be continuously monitored for effective prevention and control of AMR.

Acknowledgments

Part of this study has been presented as a poster at the VII Jornadas Doctorales de Campus Iberus (Spain).

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/antibiotics10121556/s1, Figure S1: Geographic distribution of MRSA-CC398 and mecC-MRSA isolates detected in NTO cavities of wild animals, Table S1: Study characteristics, antimicrobial resistance, and virulence genes of Staphylococcal aureus NTO carriages in wild animals, Table S2: Molecular typing reports of S. aureus isolated from the naso-tracheo-oral cavity of various free-living wild animals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: I.N.A. and C.T.; methodology: I.N.A. and C.T.; software analysis: I.N.A. validation: C.T., I.N.A., M.Z. and C.L.; formal analysis: C.T., I.N.A. and M.Z.; data curation: C.T., I.N.A., G.J.-F., S.M.-Á., P.E. and M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, I.N.A., C.T. and M.Z.; writing—review and editing: C.T., I.N.A., R.F.-F., M.Z., S.M.-Á., P.E. and C.L.; supervision: C.T. and C.L.; project administration: C.T.; funding acquisition: C.T., M.Z. and I.N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the project PID2019-106158RB-I00 of the MCIN/ AEI /10.13039/501100011033 of Spain. Also, it received funding from the European Union’s H2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 801586 (for Idris Nasir Abdullahi). R. Fernández-Fernández has a predoctoral contract from the Ministry of Spain (FPU18 /05438). G. Juarez-Fernandez has a contract associated with Project PID2019-106158RB-I00.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this systematic review and meta-analysis can be made available upon request through the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rossi C.C., Pereira M.F., Giambiagi-Demarval M. Underrated Staphylococcus species and their role in antimicrobial resistance spreading. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2020;43:e20190065. doi: 10.1590/1678-4685-gmb-2019-0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silveira D.R., De Moraes T.P., Kaefer K., Bach L.G., Barbosa A.D.O., Moretti V.D., De Menezes P.Q., De Medeiros U.S., Da Silva T.T., Bandarra P.M., et al. MRSA and enterobacteria of One Health concern in wild animals undergoing rehabilitation. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021;10:e34810111809. doi: 10.33448/rsd-v10i1.11809. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swift B.M., Bennett M., Waller K., Dodd C., Murray A., Gomes R.L., Humphreys B., Hobman J.L., Jones M.A., Whitlock S.E., et al. Anthropogenic environmental drivers of antimicrobial resistance in wildlife. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;649:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penna B., Silva M.B., Soares A.E.R., Vasconcelos A.T.R., Ramundo M.S., Ferreira F.A., Silva-Carvalho M.C., de Sousa V.S., Rabello R.F., Bandeira P.T., et al. Comparative genomics of MRSA strains from human and canine origins reveals similar virulence gene repertoire. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:4724. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83993-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porrero M.C., Mentaberre G., Sánchez S., Fernández-Llario P., Casas-Díaz E., Mateos A., Vidal M.D., Lavín S., Fernandez-Garayzabal J.F., Domínguez L. Carriage of Staphylococcus aureus by free-living wild animals in Spain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:4865–4870. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00647-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rousham E.K., Unicomb L., Islam M.A. Human, animal and environmental contributors to antibiotic resistance in low-resource settings: Integrating behavioural, epidemiological and One Health approaches. Proc. R. Soc. B Boil. Sci. 2018;285:20180332. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2018.0332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker K. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococci and Macrococci at the interface of human and animal health. Toxins. 2021;13:61. doi: 10.3390/toxins13010061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dube F., Söderlund R., Salomonsson M.L., Troell K., Börjesson S. Benzylpenicillin-producing Trichophyton erinacei and methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying the mecC gene on European hedgehogs—A pilot-study. BMC Microbiol. 2021;21:212. doi: 10.1186/s12866-021-02260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zarazaga M., Gómez P., Ceballos S., Torres C. Molecular epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus lineages in the animal-human interface. In: Fetsch A., editor. Staphylococcus aureus. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA, USA: 2018. pp. 189–214. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gómez-Sanz E., Benito D., Lozano C., Gómez P., Ceballos S., López-Vazquez M., Zarazaga M., Torres C. Factores de virulencia en Staphylococcus aureus. Tipos y caracterización genotípica. In: Velázquez Ordóñez V., editor. Producción y Calidad de la Leche. 2015. pp. 275–296. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gómez P., Ruiz-Ripa L., Fernández-Fernández R., Gharsa H., Ben S.K., Höfle U., Zarazaga M., Holmes M.A., Torres C. Genomic analysis of Staphylococcus aureus of the lineage CC130, including mecC-carrying MRSA and MSSA isolate recovered of animal, human, and environmental origins. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:e655994. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.655994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raafat D., Mrochen D.M., Al’Sholui F., Heuser E., Ryll R., Pritchett-Corning K.R., Jacob J., Walther B., Matuschka F.-R., Richter D., et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Methicillin-Susceptible and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Wild, Captive and Laboratory Rats: Effect of Habitat on the Nasal S. aureus Population. Toxins. 2020;12:80. doi: 10.3390/toxins12020080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.García-Álvarez L., Holden M., Lindsay H., Webb C., Brown D.F., Curran M.D., Walpole E., Brooks K., Pickard D.J., Teale C., et al. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with a novel mecA homologue in human and bovine populations in the UK and Denmark: A descriptive study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2011;11:595–603. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70126-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. A Brief Guide to Emerging Infectious Diseases and Zoonoses. [(accessed on 10 September 2021)]. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/909329/retrieve.

- 15.Rahman T., Sobur A., Islam S., Ievy S., Hossain J., El Zowalaty M.E., Rahman A.T., Ashour H.M. Zoonotic Diseases: Etiology, Impact, and Control. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1405. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8091405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morand S., McIntyre K.M., Baylis M. Domesticated animals and human infectious diseases of zoonotic origins: Domestication time matters. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014;24:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silva V., Gabriel S., Borrego S., Tejedor-Junco M., Manageiro V., Ferreira E., Reis L., Caniça M., Capelo J., Igrejas G., et al. Antimicrobial Resistance and Genetic Lineages of Staphylococcus aureus from Wild Rodents: First Report of mecC-Positive Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in Portugal. Animals. 2021;11:1537. doi: 10.3390/ani11061537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sousa M., Silva N., Manageiro V., Ramos S., Coelho A., Gonçalves D., Caniça M., Torres C., Igrejas G., Poeta P. First report on MRSA CC398 recovered from wild boars in the north of Portugal. Are we facing a problem? Sci. Total Environ. 2017;596–597:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gómez P., Lozano C., González-Barrio D., Zarazaga M., Ruiz-Fons F., Torres C. High prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) carrying the mecC gene in a semi-extensive red deer (Cervus elaphus hispanicus) farm in Southern Spain. Vet. Microbiol. 2015;177:326–331. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meemken D., Blaha T., Hotzel H., Strommenger B., Klein G., Ehricht R., Monecke S., Kehrenberg C. Genotypic and Phenotypic Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Wild Boars. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;79:1739–1742. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03189-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porrero M.C., Mentaberre G., Sánchez S., Fernández-Llario P., Gomez-Barrero S., Navarro-Gonzalez N., Serrano E., Casas-Díaz E., Marco I., Fernandez-Garayzabal J.F., et al. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) carriage in different free-living wild animal species in Spain. Vet. J. 2013;198:127–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mrochen D.M., Schulz D., Fischer S., Jeske K., El Gohary H., Reil D., Imholt C., Trübe P., Suchomel J., Tricaud E., et al. Wild rodents and shrews are natural hosts of Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2018;308:590–597. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruiz-Ripa L., Alcalá L., Simón C., Gómez P., Mama O.M., Rezusta A., Zarazaga M., Torres C. Diversity of Staphylococcus aureus clones in wild mammals in Aragon, Spain, with detection of MRSA ST130-mecC in wild rabbits. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019;127:284–291. doi: 10.1111/jam.14301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wardyn S.E., Kauffman L.K., Smith T.C. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Central Iowa Wildlife. J. Wildl. Dis. 2012;48:1069–1073. doi: 10.7589/2011-10-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mama O.M., Ruiz-Ripa L., Fernández-Fernández R., González-Barrio D., Ruiz-Fons F., Torres C. High frequency of coagulase-positive staphylococci carriage in healthy wild boar with detection of MRSA of lineage ST398-t011. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2019;366:fny292. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fny292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martínez L.S., Viana D., Arenas J.M.C. Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage could be a risk for development of clinical infections in rabbits. World Rabbit Sci. 2015;23:181. doi: 10.4995/wrs.2015.3960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.García L.A., Torres C., López A.R., Rodríguez C.O., Espinosa J.O., Valencia C.S. Staphylococcus spp. from wild mammals in Aragón (Spain): Antibiotic resistance status. J. Vet. Res. 2020;64:373–379. doi: 10.2478/jvetres-2020-0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plaza-Rodríguez C., Alt K., Grobbel M., Hammerl J.A., Irrgang A., Szabo I., Stingl K., Schuh E., Wiehle L., Pfefferkorn B., et al. Wildlife as Sentinels of Antimicrobial Resistance in Germany? Front. Vet. Sci. 2021;7:1251. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.627821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreno-Grúa E., Pérez-Fuentes S., Viana D., Cardells J., Lizana V., Aguiló J., Selva L., Corpa J.M. Marked Presence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Wild Lagomorphs in Valencia, Spain. Animals. 2020;10:1109. doi: 10.3390/ani10071109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pérez J.R., Rosa L.Z., Sánchez A.G., Salcedo J.H.D.M., Rodríguez J.A., Horrillo R.C., Zurita S., Gil Molino M. Multiple Antimicrobial Resistance in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus sciuri Group Isolates from Wild Ungulates in Spain. Antibiotics. 2021;10:920. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10080920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loncaric I., Kübber-Heiss A., Posautz A., Stalder G.L., Hoffmann D., Rosengarten R., Walzer C. Characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus spp. carrying the mecC gene, isolated from wildlife. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013;68:2222–2225. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sousa M., Silva V., Silva A., Silva N., Ribeiro J., Tejedor-Junco M.T., Capita R., Chenouf N.S., Alonso-Calleja C., Rodrigues T.M., et al. Staphylococci among Wild European Rabbits from the Azores: A Potential Zoonotic Issue? J. Food Prot. 2020;83:1110–1114. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-19-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seinige D., Von Altrock A., Kehrenberg C. Genetic diversity and antibiotic susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from wild boars. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017;54:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bengtsson B., Persson L., Ekström K., Unnerstad H.E., Uhlhorn H., Börjesson S. High occurrence of mecC -MRSA in wild hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus) in Sweden. Vet. Microbiol. 2017;207:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Held J., Gmeiner M., Mordmüller B., Matsiégui P.-B., Schaer J., Eckerle I., Weber N., Matuschewski K., Bletz S., Schaumburg F. Bats are rare reservoirs of Staphylococcus aureus complex in Gabon. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2017;47:118–120. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sousa M., Silva N., Igrejas G., Silva F., Sargo R., Alegria N., Benito D., Gómez P., Lozano C., Gómez-Sanz E., et al. Antimicrobial resistance determinants in Staphylococcus spp. recovered from birds of prey in Portugal. Vet. Microbiol. 2014;171:436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gómez P., Lozano C., Camacho M.C., Lima-Barbero J.-F., Hernández J.-M., Zarazaga M., Höfle U., Torres C. Detection of MRSA ST3061-t843-mecC and ST398-t011-mecA in white stork nestlings exposed to human residues: Table 1. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015;71:53–57. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruiz-Ripa L., Gómez P., Alonso C.A., Camacho M.C., De La Puente J., Fernández-Fernández R., Ramiro Y., Quevedo M.A., Blanco J.M., Zarazaga M., et al. Detection of MRSA of Lineages CC130-mecC and CC398-mecA and Staphylococcus delphini-lnu(A) in Magpies and Cinereous Vultures in Spain. Microb. Ecol. 2019;78:409–415. doi: 10.1007/s00248-019-01328-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ge J., Zhong X.-S., Xiong Y.-Q., Qiu M., Huo S.-T., Chen X.-J., Mo Y., Cheng M.-J., Chen Q. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among urban rodents, house shrews, and patients in Guangzhou, Southern China. BMC Vet. Res. 2019;15:260. doi: 10.1186/s12917-019-2012-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee M.J., Byers K., Donovan C.M., Zabek E., Stephen C., Patrick D.M., Himsworth C.G. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in urban Norway rat (Rattus norvegicus) populations: Epidemiology and the impacts of kill-trapping. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;66:343–348. doi: 10.1111/zph.12546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.John-Bosco K., Valeria N., Peter S. Nasal Carriage of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus among Sympatric Free Ranging Domestic Pigs and Wild Chlorocebus pygerythrus in a Rural African Setting. [(accessed on 10 September 2021)]. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-524223/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Schaumburg F., Pauly M., Anoh E., Mossoun A., Wiersma L., Schubert G., Flammen A., Alabi A.S., Muyembe-Tamfum J.-J., Grobusch M.P., et al. Staphylococcus aureus complex from animals and humans in three remote African regions. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015;21:345.e1–345.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaumburg F., Mugisha L., Peck B., Becker K., Gillespie T.R., Peters G., Leendertz F.H. Drug-Resistant Human Staphylococcus aureus in Sanctuary Apes Pose a Threat to Endangered Wild Ape Populations. Am. J. Primatol. 2012;74:1071–1075. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoefer A., Boyen F., Beierschmitt A., Moodley A., Roberts M., Butaye P. Methicillin-Resistant and Methicillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus from Vervet Monkeys (Chlorocebus sabaeus) in Saint Kitts. Antibiotics. 2021;10:290. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10030290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schaumburg F., Mugisha L., Kappeller P., Fichtel C., Köck R., Köndgen S., Becker K., Boesch C., Peters G., Leendertz F. Evaluation of Non-Invasive Biological Samples to Monitor Staphylococcus aureus Colonization in Great Apes and Lemurs. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78046. doi: 10.1371/annotation/c2148f4d-866d-479a-b0e6-97aa6ab931f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schaumburg F., Alabi A.S., Köck R., Mellmann A., Kremsner P.G., Boesch C., Becker K., Leendertz F.H., Peters G. Highly divergent Staphylococcus aureus isolates from African non-human primates. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2011;4:141–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2011.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roberts M.C., Joshi P.R., Greninger A.L., Melendez D., Paudel S., Acharya M., Bimali N.K., Koju N.P., No D., Chalise M., et al. The human clone ST22 SCCmec IV methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from swine herds and wild primates in Nepal: Is man the common source? FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018;94:fiy052. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiy052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gongal G. One Health Approach in the South East Asia Region: Opportunities and challenges. In: Mackenzie J.S., Jeggo M., Daszak P., Richt J.A., editors. One Health: The Human-Animal-Environment Interfaces in Emerging Infectious Diseases. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2013. pp. 113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silva V., Capelo J.L., Igrejas G., Poeta P. Molecular Epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus Lineages in Wild Animals in Europe: A Review. Antibiotics. 2020;9:122. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9030122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abdullahi I., Lozano C., Ruiz-Ripa L., Fernández-Fernández R., Zarazaga M., Torres C. Ecology and Genetic Lineages of Nasal Staphylococcus aureus and MRSA Carriage in Healthy Persons with or without Animal-Related Occupational Risks of Colonization: A Review of Global Reports. Pathogens. 2021;10:1000. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10081000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bierowiec K., Płoneczka-Janeczko K., Rypuła K. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Colonization with Staphylococcus aureus Healthy Pet Cats Kept in the City Households. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Colonization with Staphylococcus aureus Healthy Pet Cats Kept in the City Households. BioMed Res. Int. 2016;2016:3070524. doi: 10.1155/2016/3070524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ruiz-Ripa L., Gómez P., Alonso C.A., Camacho M.C., Ramiro Y., De La Puente J., Fernández-Fernández R., Quevedo M., Blanco J.M., Báguena G., et al. Frequency and Characterization of Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Genes of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci from Wild Birds in Spain. Detection of tst-Carrying S. sciuri Isolates. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1317. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8091317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jourdain E., Gauthier-Clerc M., Bicout D.J., Sabatier P. Bird Migration Routes and Risk for Pathogen Dispersion into Western Mediterranean Wetlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007;13:365–372. doi: 10.3201/eid1303.060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gómez-Sanz E., Torres C., Lozano C., Fernández-Pérez R., Aspiroz C., Larrea F.R., Zarazaga M. Detection, Molecular Characterization, and Clonal Diversity of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus CC398 and CC97 in Spanish Slaughter Pigs of Different Age Groups. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2010;7:1269–1277. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lozano C., Fernández-Fernández R., Ruiz-Ripa L., Gómez P., Zarazaga M., Torres C. Human mecC-Carrying MRSA: Clinical Implications and Risk Factors. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1615. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8101615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Loncaric I., Kübber-Heiss A., Posautz A., Stalder G.L., Hoffmann D., Rosengarten R., Walzer C. mecC- and mecA-positive meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolated from livestock sharing habitat with wildlife previously tested positive for mecC-positive MRSA. Vet. Dermatol. 2014;25:147–148. doi: 10.1111/vde.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Monecke S., Jatzwauk L., Müller E., Nitschke H., Pfohl K., Slickers P., Reissig A., Ruppelt-Lorz A., Ehricht R. Diversity of SCCmec Elements in Staphylococcus aureus as Observed in South-Eastern Germany. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0162654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aklilu E., Chia H.Y. First mecC and mecA Positive Livestock-Associated Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (mecC MRSA/LA-MRSA) from Dairy Cattle in Malaysia. Microorganisms. 2020;8:147. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8020147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Porrero M.C., Harrison E., Fernández-Garayzábal J.F., Paterson G.K., Díez-Guerrier A., Holmes M.A., Domínguez L. Detection of mecC-Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates in river water: A potential role for water in the environmental dissemination. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2014;6:705–708. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heaton C.J., Gerbig G.R., Sensius L.D., Patel V., Smith T.C. Staphylococcus aureus Epidemiology in Wildlife: A Systematic Review. Antibiotics. 2020;9:89. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9020089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harrison E.M., Coll F., Toleman M.S., Blane B., Brown N.M., Torok E., Parkhill J., Peacock S.J. Genomic surveillance reveals low prevalence of livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the East of England. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:7406. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07662-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gómez P., González-Barrio D., Benito D., García J.T., Viñuela J., Zarazaga M., Ruiz-Fons F., Torres C. Detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) carrying the mecC gene in wild small mammals in Spain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014;69:2061–2064. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ceballos S., Aspiroz C., Ruiz-Ripa L., Reynaga E., Azcona-Gutiérrez J.M., Rezusta A., Seral C., Antoñanzas F., Torres L., López A.R., et al. Epidemiology of MRSA CC398 in hospitals located in Spanish regions with different pig-farming densities: A multicentre study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019;74:2157–2161. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Price L.B., Stegger M., Hasman H., Aziz M., Larsen J., Andersen P.S., Pearson T., Waters A.E., Foster J., Schupp J., et al. Staphylococcus aureus CC398: Host Adaptation and Emergence of Methicillin Resistance in Livestock. mBio. 2012;3:e00305-11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00305-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mama O.M., Aspiroz C., Ruiz-Ripa L., Ceballos S., Iñiguez-Barrio M., Cercenado E., Azcona J.M., López-Cerero L., Seral C., López-Calleja A.I., et al. Prevalence and Genetic Characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus CC398 Isolates From Invasive Infections in Spanish Hospitals, Focusing on the Livestock-Independent CC398-MSSA Clade. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:623108. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.623108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Salgueiro V., Manageiro V., Bandarra N.M., Ferreira E., Clemente L., Caniça M. Genetic Relatedness and Diversity of Staphylococcus aureus from Different Reservoirs: Humans and Animals of Livestock, Poultry, Zoo, and Aquaculture. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1345. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8091345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Monecke S., Gavier-Widén D., Hotzel H., Peters M., Guenther S., Lazaris A., Loncaric I., Müller E., Reissig A., Ruppelt-Lorz A., et al. Diversity of Staphylococcus aureus Isolates in European Wildlife. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0168433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Michalik M., Kosecka-Strojek M., Wolska M., Samet A., Podbielska-Kubera A., Międzobrodzki J. First Case of Staphylococci Carrying Linezolid Resistance Genes from Laryngological Infections in Poland. Pathogens. 2021;10:335. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10030335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zheng Y., Qin C., Zhang X., Zhu Y., Li A., Wang M., Tang Y., Kreiswirth B.N., Chen L., Zhang H., et al. The tst gene associated Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity island facilitates its pathogenesis by promoting the secretion of inflammatory cytokines and inducing immune suppression. Microb. Pathog. 2019;138:103797. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Novick R.P., Ram G. Staphylococcal pathogenicity islands—Movers and shakers in the genomic firmament. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017;38:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this systematic review and meta-analysis can be made available upon request through the corresponding author.