Abstract

In Osaka City, Japan, between April 1996 and March 1999, a total of 350 fecal specimens from 64 outbreaks of acute nonbacterial gastroenteritis were examined to investigate infection by “Norwalk-like viruses” (NLVs). By reverse transcription (RT)-PCR, 182 samples (52.0%) from 47 outbreaks (73.4%) were NLV positive. During those three years, the incidence of NLV-associated outbreaks showed seasonality, being higher during January to March (winter to early spring). The ingestion of contaminated oysters was the most common transmission mode (42.6%). The amplicons of the 47 outbreak strains that were NLV positive by RT-PCR were tested using Southern hybridization with four probe sets (Ando et al., J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:64–71, 1995). Forty of the outbreak strains were classified as 4 probe 1-A (P1-A) strains, 6 P1-B strains, 10 P2-A strains, 17 P2-B strains, and 3 untypeable strains, and the other 7 outbreaks were determined to be mixed-probe-type strains. Probe typing and partial sequence analysis of the outbreak strains indicated that a predominant probe type of NLVs in Osaka City had drastically changed; P2-B strains (77.8%) with multiple genetic clusters were observed during the 1996–97 season, the P2-A common strain (81.3%) related to the Toronto virus cluster was observed during the 1997–98 season, and P1-B strains (75.0%) with a genetic similarity were observed during the 1998–99 season. For the three untypeable outbreak strains (96065, 97024, and 98026), the 98026 outbreak strain had Southampton virus (SOV)-like sequences, and each of the other outbreak strains had a unique 81-nucleotide sequence. Newly designed probes (SOV probe for the 98026 outbreak strain and the 96065 probe for the 96065 and 97024 outbreak strains) were hybridized with relative strains and without other probe type strains. The prevalent NLV probe types in Osaka City during those three years were classified in six phylogenetic groups: P1-A, P1-B, P2-A, P2-B, SOV, and 96065 probe types.

“Norwalk-like viruses” (NLVs), also called small round-structured viruses, are single-stranded-RNA viruses that were recently assigned to the family Caliciviridae (13, 15). NLVs are a major cause of acute nonbacterial gastroenteritis in children and adults, especially important cases of food-borne gastroenteritis associated with the ingestion of contaminated water (17, 19), food (26, 31), and oysters (6, 30, 36), and are thus a concern in the field of public health (34, 16). NLV infections, including outbreaks and sporadic cases, have been reported in the United States (3, 8), United Kingdom (5, 29), The Netherlands (38, 39), Japan (23, 25, 34), Australia (11, 42), South Africa (37, 41), and other countries (7, 21, 35).

Diagnosis of NLV infections has been difficult because they cannot be grown in animals and cell culture. Electron microscopy (EM) and immune electron microscopy (IEM) have been used for diagnosis of NLV infections (4, 34) but have a low sensitivity. Recently, the cloning and sequencing of the complete genomes of Norwalk virus (13, 15) and Southampton virus (SOV) (18) enabled the diagnosis of NLVs by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (2, 9, 14, 20, 24). In addition, NLVs were classified into two genogroups, genogroup 1 (G1) and G2, on the basis of their sequences in the RNA polymerase region (1, 40). The use of RT-PCR for some detection methods for NLVs has been reported, and the higher sensitivity of RT-PCR compared with that of EM and IEM has been demonstrated. However, many of the primer sets of RT-PCR detect only a narrow range of NLV strains, owing to the considerable genomic diversity among strains.

A broadly reactive RT-PCR using G1 and G2 primer sets combined with Southern hybridization was described by Ando et al. (2). Their detection method for NLVs is not only broadly reactive to NLVs but also useful for easy analysis of the molecular epidemiology of NLVs, which can be classified into four probe types, P1-A, P1-B, P2-A, and P2-B, using Southern hybridization (2, 21). However, little is known about the prevalent changes in NLV strains causing outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis, because novel molecular methods for characterizing strains have only recently been developed.

In the present study, we investigated the incidence of NLVs associated with outbreaks of acute nonbacterial gastroenteritis in Osaka City, Japan, during three years, between April 1996 and March 1999. Analyzing the epidemiology of NLVs by the probe typing method using Southern hybridization and the partial sequence characterizations of NLVs gave us understanding of the role of NLVs in outbreaks of nonbacterial gastroenteritis and the change in predominant NLV strains over time.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Outbreaks and specimens.

The fecal specimens were collected from 64 outbreaks of acute nonbacterial gastroenteritis, including 22 outbreaks associated with oysters, in Osaka City, Japan, between April 1996 and March 1999. A total of 350 fecal specimens from patients with acute gastroenteritis were examined using RT-PCR.

RNA extraction.

Viral RNA was extracted from 10 to 20% stool suspension in Eagle's minimal essential medium (MEM) by the Ultraspec-3 RNA isolation system (BIOTECX Laboratories, Inc., Houston, Tex.).

One hundred to two hundred microliters of stool suspension was added to 1 ml of Ultraspec-3 reagent and mixed thoroughly. The mixture was added to 200 μl of chloroform, mixed, and placed on ice for 5 min. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min, the aqueous-phase mixture was transferred to a fresh tube and then precipitated with an equal volume of isopropanol. The pellet was suspended in 30 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water and kept at −80°C until used in RT-PCR.

RT-PCR.

Ando et al.'s (2) two primer sets (G1 and G2) amplifying a 123-bp polymerase region were used.

RT and PCR were carried out sequentially in a single tube. RNA from each sample was tested by RT-PCR, using primer sets G1 (SR33, SR48, SR50, and SR52) and G2 (SR33 and SR46) simultaneously in separate reactions. RT-PCR was performed with 50 μl of reaction mixture containing 1 μl of purified viral RNA (heated at 65°C for 5 min and cooled on ice), 10 μl of Ampdirect-A (Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan) (for human blood), 0.2 μM (each) G1 or G2 primer sets, 200 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 2 mM dithiothreitol, 3 units of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase XL (Life Science Inc., St. Petersburg, Fla.), 20 U of ribonuclease inhibitor (TaKaRa Shuzo Co., Ltd., Otsu, Japan), and 2.5 U of recombinant Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa Shuzo Co., Ltd.). The thermocycle format on the thermal cycler (Gene Amp PCR System 9700; Perkin-Elmer Co., Foster City, Calif.) used in the RT-PCR was as follows: RT at 50°C for 30 min, followed by heat at 94°C for 3 min; 40 amplification cycles with denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 50°C for 30 s, and extension at 60°C for 30 s; and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. Amplification products were analyzed using 3.0% NuSieve 3:1 agarose gel (FMC Bio Products, Rockland, Maine) electrophoresis, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized with UV illumination. Further genetic analysis of NLV strains identified by RT-PCR using G1 and G2 primer sets was done by amplifying a 322-bp sequence of the capsid region, using two additional primers, mon381 and mon383 (27).

Probe typing of NLVs.

The RT-PCR products were confirmed by Southern hybridization and classified into the four probe types, P1-A, P1-B, P2-A, and P2-B (P1-A type probes, SR63d, SR65d, and SR69d; P1-B type probe, SR67d; P2-A type probe, SR61d; P2-B type probe, SR47d), of Ando et al. (2). Hybridization and chemiluminescence detection were carried out using a digoxigenin luminescence detection kit for nucleic acids according to the recommended protocols (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany).

Sequencing of NLVs.

The RT-PCR products were gel purified using a Qiaex II gel extraction kit (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.). Nucleotide sequencing of both strands of the products was performed using an ABI PRISM dRhodamine Terminator Cycle Sequencing FS Ready Reaction kit (Perkin-Elmer Co.) on an automated sequencer (ABI PRISM 310 model; Perkin-Elmer Co.).

The nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the NLV strains were aligned using the Clustal-X Multiple Sequence Alignment program (version 1.63b; December 1997). A phylogram was created using the neighbor joining method (33). The nucleotide sequences were compared with those of our collection of 54 outbreak strains, 13 reference strains from the GenBank, and the 6 previously published strains (2, 3, 27) to identify some similarities.

RESULTS

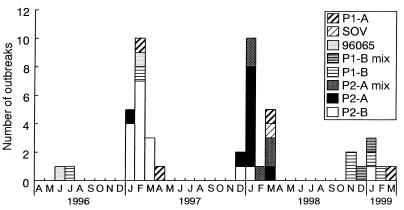

A total of 182 fecal specimens (52.0%) from 47 outbreaks (73.4%) were NLV positive by RT-PCR. An outbreak strain, 98248, that was NLV negative by RT-PCR using G1 and G2 primer sets and positive by EM could be identified by RT-PCR using the primer pair SR33 and SM82 (32). For outbreak 97051, in one fecal specimen a rotavirus was detected by EM and NLV was detected by RT-PCR. In fecal specimens from 17 outbreaks for which NLV was not detected, other etiologic agents also were not detected. A description of the NLV-positive outbreaks and some epidemiological findings are given in Table 1. The 47 NLV-positive outbreaks occurred in different settings: restaurants, homes, hotels, schools, nursing homes, and an institute for mentally challenged people. For the reported transmission modes of these outbreaks, ingestion of contaminated oysters was the most common (42.6%), followed by food-borne spread (14.9%) and person-to-person contact (2.1%); the specific transmission mode for many outbreaks could not be determined (40.4%). The major symptoms were nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. NLV-associated gastroenteritis outbreaks in Osaka City tended to occur more frequently during January to March in these three years (83.0%) (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Descriptions of outbreaks in which NLVs were detected in Osaka City, Japan, between April 1996 and March 1999a

| Outbreak no. | Mo/yr | Place | Source | Attack rate (ill/risk) | No. of fecal specimens tested | Number of RT-PCR-positive specimens (G1 or G2) | Probe type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 96065 | Jun/96 | Elementary school | UK | 35/UK | 18 | 10 (G2) | 96065 |

| 96086 | Jul/96 | UK | UK | 2/UK | 1 | 1 (G2) | P1-B |

| 97005 | Jan/97 | Restaurant | Oyster | 11/18 | 8 | 3 (G2) | P2-A |

| 97007 | Jan/97 | Restaurant | UK | 6/UK | 3 | 2 (G2) | P2-B |

| 97014 | Jan/97 | Home | UK | 2/2 | 2 | 2 (G2) | P2-B |

| 97015 | Jan/97 | Home | UK | 1/2 | 1 | 1 (G2) | P2-B |

| 97022 | Jan/97 | Restaurant | Oyster | 15/UK | 5 | 3 (G2) | P2-B |

| 97024 | Feb/97 | Elementary school | UK | 26/UK | 11 | 7 (G2) | 96065 |

| 97026 | Feb/97 | Restaurant | UK | 4/6 | 2 | 1 (G2) | P1-B |

| 97030 | Feb/97 | Restaurant | Oyster | 20/50 | 12 | 4 (G2) | P2-B |

| 97037 | Feb/97 | Nursing home | UK | 19/UK | 20 | 9 (G1) | P1-A |

| 97038 | Feb/97 | Hotel | Oyster | 17/27 | 3 | 1 (G2) | P2-B |

| 97039 | Feb/97 | Restaurant | UK | 3/4 | 1 | 1 (G2) | P2-B |

| 97040 | Feb/97 | Restaurant | Oyster | 4/UK | 1 | 1 (G2) | P2-B |

| 97041 | Feb/97 | Restaurant | UK | 2/2 | 2 | 2 (G2) | P2-B |

| 97043 | Feb/97 | Restaurant | Oyster | 6/19 | 3 | 3 (G2) | P2-B |

| 97044 | Feb/97 | Institute for mentally challenged people | PP | 93/UK | 10 | 4 (G2) | P2-B |

| 97045 | Mar/97 | Restaurant | Oyster | 2/2 | 2 | 1 (G2) | P2-B |

| 97049 | Mar/97 | Restaurant | UK | 3/4 | 1 | 1 (G2) | P2-B |

| 97051b | Mar/97 | Hotel | Food | 22/112 | 0 | 2 (G2) | P2-B |

| 97071 | Apr/97 | UK | UK | 5/UK | 2 | 2 (G1) | P1-A |

| 97290 | Dec/97 | Restaurant | Food | 55/158 | 19 | 12 (G2) | P2-A |

| 97299 | Dec/97 | Cramming school | Food | 82/190 | 6 | 6 (G2) | P2-B |

| 98004 | Jan/98 | UK | Oyster | 8/UK | 7 | 5 (G2) | P2-B, P2-A |

| 98006 | Jan/98 | UK | Oyster | 8/UK | 6 | 3 (G2) | P2-A |

| 98008 | Jan/98 | UK | UK | 20/UK | 10 | 10 (G2) | P2-A |

| 98010 | Jan/98 | UK | Oyster | 9/UK | 2 | 1 (G2) | P2-A |

| 98011 | Jan/98 | Restaurant | Food | 7/10 | 3 | 3 (G2) | P2-A |

| 98012 | Jan/98 | Home | Oyster | 28/77 | 4 | 2 (G2) | P1-B, P2-A, P2-B |

| 98013 | Jan/98 | Restaurant | Food | 32/UK | 1 | 1 (G2) | P2-B |

| 98014 | Jan/98 | UK | Oyster | 11/UK | 9 | 5 (G2) | P2-A |

| 98015 | Jan/98 | UK | Oyster | 4/UK | 2 | 2 (G2) | P2-A |

| 98016 | Jan/98 | UK | Oyster | 19/UK | 13 | 6 (G2) | P2-A |

| 98018 | Feb/98 | UK | Oyster | 4/UK | 4 | 4 (G1, G2) | P1-A, P1-B, P2-A, P-2B |

| 98020 | Mar/98 | Restaurant | Oyster | 18/26 | 12 | 8 (G1, G2) | P1-A, P2-A, P2-B |

| 98021 | Mar/98 | Restaurant | Oyster | 14/25 | 5 | 1 (G1) | P1-A |

| 98023 | Mar/98 | UK | Oyster | 4/UK | 1 | 1 (G2) | P2-A |

| 98024 | Mar/98 | Restaurant | Food | 8/13 | 4 | 3 (G1, G2) | P1-A, P2-A |

| 98026 | Mar/98 | UK | UK | 16/UK | 11 | 11 (G1) | SOV |

| 98248 | Nov/98 | Restaurant | Food | 33/53 | 2 | 2c | P1-B |

| 98249 | Nov/98 | UK | UK | 2/UK | 2 | 1 (G2) | P1-B |

| 98256 | Dec/98 | UK | UK | 3/UK | 2 | 2 (G2) | P1-B, P2-A, P2-B |

| 99001 | Jan/99 | UK | UK | 2/UK | 2 | 1 (G2) | P2-B |

| 99005 | Jan/99 | Restaurant | Oyster | 3/3 | 3 | 3 (G1, G2) | P1-A, P1-B, P2-A |

| 99006 | Jan/99 | Restaurant | Oyster | 57/96 | 26 | 24 (G2) | P1-B |

| 99024 | Feb/99 | UK | UK | 3/UK | 3 | 1 (G2) | P1-B |

| 99030 | Mar/99 | Elementary school | UK | 14/UK | 3 | 3 (G1) | P1-A |

| Total | 274 | 182 |

Abbreviations: UK, unknown; PP, person to person.

Rotavirus detected in one sample.

Detected with primer pair SR33 and SM82.

FIG. 1.

Monthly distribution of the 47 NLV-associated outbreaks by the probe typing method in Osaka City, Japan, over three years between April 1996 and March 1999. Single-probe-type strains were identified from 40 outbreaks. Mixed-probe-type strains were identified from seven outbreaks (P2-A mix, P2-A and the other probe type strains; P1-B mix, P1-B and the other probe type strains). SOV and 96065 are newly designed probes used in this study (SOV, probe for SOV in G1; 96065, probe for untypeable outbreak strains 96065 and 97024 in G2). Single letters indicate the first letters of the names of months.

All the NLV-positive RT-PCR products were tested by Southern hybridization with the four probe sets. Forty outbreak strains were classified as 4 P1-A strains, 6 P1-B strains, 10 P2-A strains, 17 P2-B strains, and 3 untypeable strains. For the seven other outbreaks, mixed-probe-type strains were detected. In the mixed probe type of NLV infections, P2-A strains from five outbreaks were dominant during the 1997–98 season (P2-A mix), and P1-B strains from two outbreaks were dominant during the 1998–99 season (P1-B mix) (Fig. 1). P2-B strains were detected in 14 of 19 outbreaks (73.7%) during the 1996–97 season. P2-A strains including P2-A mix were detected in 14 of 18 outbreaks (77.8%) during the 1997–98 season. P1-B strains including P1-B mix were detected in six of eight outbreaks (75.0%) during the 1998–99 season.

The 81-bp region (excluding the two primer regions) of the polymerase gene of 54 strains from 47 NLV-positive outbreaks and the 277-bp region (excluding the two primer regions) of the capsid gene of 16 P2-A outbreak strains were sequenced (except for the 98012/2A strains). For the 98248 strain, the 334-bp region of the amplicon was sequenced, which was analyzed in the same 81-bp region as the other strains. For the 81-nucleotide sequence data, each outbreak strain sequence was segregated into 6 different P1-A sequences, 3 different P1-B sequences, a common P2-A sequence, and 12 different P2-B sequences. The 3 untypeable outbreak strains (96065, 97024, and 98026) were each of different sequences. In the four probe type groups, pairwise comparison of the alignments of the 81-nucleotide sequence indicated similarities of 81.5 to 100% for amino acid sequences and 67.9 to 100% for nucleotide sequences within individual probe type groups and 55.6 to 85.2% for amino acid sequences and 55.6 to 77.8% for nucleotide sequences between the probe type groups (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Nucleotide and amino acid similarities of NLV strains among six probe types in the polymerase regiona

| Probe type | % Similarity in G1 probe type:

|

% Similarity in G2 probe type:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1-A | SOV | P1-B | P2-A | P2-B | 96065 | ||

| G1 | P1-A | 67.9–100.0; 81.5–100.0 | 66.7–86.4 | 59.3–74.0 | 55.6–71.6 | 59.3–70.4 | 64.2–76.5 |

| SOV | 85.2–92.6 | 93.8; 100.0 | 65.4–70.4 | 67.9–71.6 | 61.7–72.8 | 64.2–72.8 | |

| G2 | P1-B | 63.0–74.1 | 63.0–70.4 | 75.3–100.0; 88.9–100.0 | 58.0–65.4 | 55.6–69.1 | 64.2–72.8 |

| P2-A | 63.0–74.1 | 74.1 | 59.3–63.0 | 96.3–100.0; 100.0 | 66.7–77.8 | 66.7–70.4 | |

| P2-B | 63.0–77.8 | 70.4–77.8 | 55.6–66.7 | 77.8–85.2 | 75.3–100.0; 85.2–100.0 | 60.5–77.8 | |

| 96065 | 66.7–81.5 | 74.1–77.8 | 70.4–77.8 | 70.4–74.1 | 70.4–85.2 | 77.8; 92.6 | |

The numbers in boldface correspond to the percentages of nucleotide similarity, and those in lightface correspond to the percentages of amino acid similarity.

All P2-A outbreak strains at the polymerase region and 14 of 16 P2-A outbreak strains at the capsid region had identical nucleotide sequences. Only one P2-A outbreak strain, 97005, detected during the 1996–97 season, had 97.8% amino acid sequence similarity and 90.6% nucleotide sequence similarity at the capsid region with the P2-A common strains (Table 3). The 98014 strain had one base sequence at the capsid region different from that of the P2-A common strain. The 98012/2A strain was not amplified with primer pairs mon381 and mon383.

TABLE 3.

Nucleotide and amino acid sequence identities of P2-A strains at the capsid region

| Reference | % Identity of P2-A straina:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 98014

|

97005

|

TV

|

Mexico virus

|

OTH25

|

||||||

| Nt | Aa | Nt | Aa | Nt | Aa | Nt | Aa | Nt | Aa | |

| P2-A common strain | 99.6 | 100.0 | 90.6 | 97.8 | 91.3 | 98.9 | 91.7 | 97.8 | 91.0 | 96.7 |

Nt, nucleotide; Aa, amino acid.

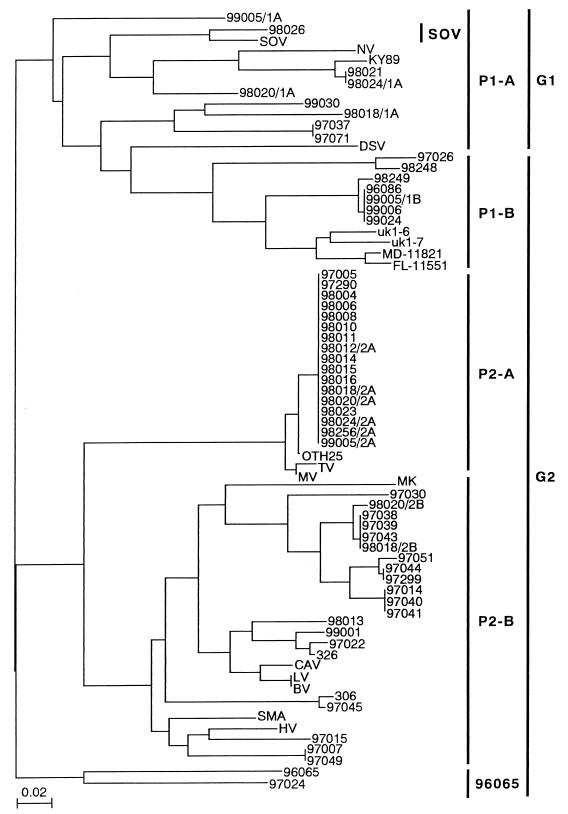

The phylogram based on the 81-nucleotide sequences from a total of 54 outbreak strains clearly segregated them into two phylogenetically distinct genogroups, 1 and 2 (Fig. 2). P1-B strains detected with the G2 primer set were related to G1 strains in the 81-nucleotide sequence analysis. Noel et al. (27) placed the P1-B strains in G2 on the basis of the capsid analysis, although those strains were placed in G1 on the basis of the polymerase analysis of the small region. Therefore, the P1-B group, including the seven outbreak strains, was classified in G2.

FIG. 2.

Phylogram of the 54 outbreak strains, 13 reference strains from the GenBank, and 6 previously published strains: two uk strains (2); MD-11821 and FL-11551 of Ando et al. (3); 306 and 326 of Noel et al. (27), based on 81 nucleotide sequences of the RNA polymerase region constructed using the neighbor joining method. SOV, P1-A, P1-B, P2-A, P2-B, and 96065 are genetic groups classified using the probe typing method of Ando et al. (2). GenBank accession numbers for reference strains used in this analysis: Bristol virus (BV), X76716; Camberwell virus (CAV), U46500; Desert Shield virus (DSV), U04469; Hawaii virus (HV), U07611; KY89, L23828; Lordsdale virus (LV), X86557; Melksham virus (MK), X81879; Mexico virus (MV), U22498; Norwalk virus (NV), M87611; OTH25, L23830; Snow Mountain agent (SMA), L23831; SOV, L07418; TV, U02030.

In G1, there were nine outbreak strains (16.7%), including the eight P1-A outbreak strains and the one untypeable outbreak strain (98026). The 98026 outbreak strain had 100% amino acid sequence similarity and 93.8% nucleotide sequence similarity with SOV (Table 2). In G2, there were 45 outbreak strains (83.3%), including the 7 P1-B outbreak strains, 17 P2-A outbreak strains, 19 P2-B outbreak strains, and 2 untypeable outbreak strains (96065 and 97024). The 96065 and 97024 outbreak strains each had a unique 81-nucleotide sequence. These two outbreak strains had 92.6% amino acid sequence similarity and 77.8% nucleotide sequence similarity to each other, and 66.7 to 85.2% of amino acid sequences and 60.5 to 77.8% of nucleotide sequences were similar to those of other NLV strains (Table 2). In the P2-B group with multiple genetic clusters, 11 of 19 P2-B outbreak strains (57.9%) were very closely related to each other (100% amino acid sequence similarity and 91.4 to 100% nucleotide sequence similarity). NLVs in the P2-A group had high similarities of 100% for amino acid sequences and 96.3 to 100% for nucleotide sequences and formed one genetic cluster, the Toronto virus (TV) cluster. Four of five P1-B outbreak strains (80.0%) detected during the 1998–99 season had genetically similar 81-nucleotide sequences.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of NLV infection has recently been improved by the development of the RT-PCR method (2, 14, 20). The genetic diversity of these viruses has been reported in connection with the studies of NLV-associated outbreaks of acute nonbacterial gastroenteritis with RT-PCR (8, 10, 29, 39).

In the present study, we analyzed NLVs from outbreaks in Osaka City, Japan, and their epidemiology using RT-PCR, the probe typing method, and partial sequence characterization. NLVs were detected in 52.0% of all fecal specimens (66.4% of fecal specimens from NLV-positive outbreaks) and for 73.4% of all outbreaks, using RT-PCR. These findings show that NLVs are the most important agents of outbreaks of acute nonbacterial gastroenteritis. In the case of the outbreak strain 98248, which was detected by the primer pair SR33 and SM82, it was thought that five different nucleotide sequences at the annealing region with SR46 prevented amplification with the G2 primer set (SR33 and SR46). Since the NLVs have genetic diversity, it is important to broadly detect NLVs using RT-PCR with some primers, EM, or both methods.

The present investigation of NLV-associated outbreaks in Osaka City showed, as epidemiological features, that (i) the incidence of outbreaks tended to increase during January to March (winter to early spring), (ii) the most important transmission mode was ingestion of contaminated oyster, and (iii) genogroup 2 of multiple genetic NLV strains was prevalent. Our findings were similar to those of previous studies in Japan (12, 34, 43).

Probe typing and partial sequence characterization of outbreak strains indicated that the predominant probe type of NLVs prevailing in Osaka City had drastically changed: the P2-B strains with multiple genetic strains were observed during the 1996–97 season, the P2-A common strain with TV cluster was seen during the 1997–98 season, and the P1-B strains with genetic similarity were prominent during the 1998–99 season (Fig. 1). During the 1996–97 season, 8 of 14 P2-B outbreak strains (57.1%) formed one cluster and were considered a dominant NLV type. These findings suggested that the genetic type of the NLV outbreak strains changed every season. In Canada, Levett et al. (21) showed a change in the predominant probe type of NLVs in circulation between 1991 and 1995 by using Ando's probe typing method. Vinje et al. (39) suggested the shift of a predominant NLV strain in The Netherlands. In the United Kingdom, a change has been reported in the predominant virus from Bristol-like virus to Grimsby-like virus in G2 (10, 22). To understand the outbreaks caused by NLV infection, further research is required to clarify if this change of predominant or dominant NLV strains occurred over the whole of Japan or only in a local area, Osaka City, and if these predominant strains detected in Osaka City were associated with the NLV strain detected in other geographical locations.

For three outbreak strains (96065, 97024, and 98026) which did not hybridize with four probe sets, the 98026 outbreak strain had SOV-like sequences, and the other outbreak strains had each a unique 81-nucleotide sequence. We designed two oligonucleotide probes labeled at the 5′ end with digoxigenin based on the sequence of SOV (SOV probe: 5′-ACG TCT GGC GAC AGG CCA GT-3′) or the 96065 outbreak strain (96065 probe: 5′-ACA TCG GGT GAC AAT CCA GA-3′) at the same location as the other probes. Newly designed probes (the SOV probe for the 98026 outbreak strain and the 96065 probe for the 96065 and 97024 outbreak strains) were hybridized with relative strains and without the other probe type strains (data not shown). The 96065 and 97024 outbreak strains, for which there is no reference strain, are considered a new genetic type of NLVs (Fig. 2). These two outbreak strains are needed to analyze the other gene regions of the polymerase or the capsid gene. Results of probe typing suggested that at least six probe types of NLVs circulated in Osaka City during the three years when testing was done.

During the 1997–98 season, we observed the sudden emergence and spread of the P2-A common strain. Interestingly, 71.4% of the outbreaks, for which the P2-A common strains were detected, were associated with oysters. The ingestion of oysters contaminated with the P2-A common strain was considered an important factor in this prevalence. However, the source of the common strain is unknown. Before the prevalence of the common strain, only one P2-A outbreak strain (97005) was detected during the 1996–97 season, which had the same polymerase sequence and a different capsid sequence. So the outbreak strain 97005 did not circulate and spread in the next season. In the United States, a predominant common strain (95/96-US) within the Lordsdale virus cluster was identified from outbreaks in 15 geographically dispersed states (8). The 95/96-US strain was identified in seven other countries on five continents during the same period by sequence comparisons, and this suggested that a single NLV strain was also circulating globally (28). In a small geographical location in the United Kingdom, a common strain similar to Grimsby virus was associated with the majority of NLV-associated outbreaks during the 1996–97 season (22). The findings about the emergence and spread of the common strain in these outbreaks were unclear. Noel et al. (28) suggested that the circulation of the 95/96-US strain might involve patterns of transmission not previously considered and proposed the establishment of the international surveillance network with sequence data using a standard diagnostic method to understand the global circulation of NLVs. Further investigation of NLVs in sporadic cases is needed to understand the emergence, spread, and circulation of NLVs. The role of NLVs in sporadic cases and whether these cases are linked to outbreaks will be investigated in future studies.

The present findings showed that this RT-PCR and probe typing method was useful for routine diagnosis of NLV infection and was the first application to enhance our understanding of the molecular epidemiology of NLVs. Routine monitoring of the NLV-associated outbreak using this detection method will potentially be predictive of the prevalence of the NLV probe types.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tamie Ando, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for technical advice and Teruo Kimura for helpful advice.

This work was supported by a grant from the Daido Seimei Social Welfare Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ando T, Mulders M N, Lewis D C, Estes M K, Monroe S S, Glass R I. Comparison of the polymerase region of small round structured virus strains previously classified in three antigenic types by solid-phase immune electron microscopy. Arch Virol. 1994;135:217–226. doi: 10.1007/BF01309781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ando T, Monroe S S, Gentsch J R, Jin Q, Lewis D C, Glass R I. Detection and differentiation of antigenically distinct small round-structured viruses (Norwalk-like viruses) by reverse transcription-PCR and Southern hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:64–71. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.64-71.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ando T, Jin Q, Gentsch J R, Monroe S S, Noel J S, Dowell S F, Cicirello H G, Kohn M A, Glass R I. Epidemiologic applications of novel molecular methods to detect and differentiate small round structured viruses (Norwalk-like viruses) J Med Virol. 1995;47:145–152. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890470207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caul E O, Appleton H. The electron microscopical and physical characteristics of small round human fecal viruses: an interim scheme for classification. J Med Virol. 1982;9:257–265. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890090403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dedman D, Laurichesse H, Caul E O, Wall P G. Surveillance of small round structured virus (SRSV) infection in England and Wales, 1990–5. Epidemiol Infect. 1998;121:139–149. doi: 10.1017/s0950268898001095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowell S F, Groves C, Kirkland K B, Cicirello H G, Ando T, Jin Q, Gentsch J R, Monroe S S, Humphrey C D, Slemp C, Dwyer D M, Meriwether R A, Glass R I. A multistate outbreak of oyster-associated gastroenteritis: implication for interstate tracing of contaminated shellfish. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1497–1503. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falzon D. SRSV-1 gastroenteritis in Malta—1995. Eurosurveillance. 1996;1:17–19. doi: 10.2807/esm.01.03.00198-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fankhauser R L, Noel J S, Monroe S S, Ando T, Glass R I. Molecular epidemiology of “Norwalk-like viruses” in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in the United States. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1571–1578. doi: 10.1086/314525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green J, Gallimore C I, Norcott J P, Lewis D, Brown D W G. Broadly reactive reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of SRSV-associated gastroenteritis. J Med Virol. 1995;47:392–398. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890470416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green S M, Lambden P R, Caul E O, Clarke I N. Capsid sequence diversity in small round structured viruses from recent UK outbreaks of gastroenteritis. J Med Virol. 1997;52:14–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grohmann G S, Greenberg H B, Welch B M, Murphy A M. Oyster associated gastroenteritis in Australia: the detection of Norwalk virus and its antibody by immune electron microscopy and radioimmunoassay. J Med Virol. 1980;6:11–19. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890060103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haruki K, Seto Y, Murakami T, Kimura T. Pattern of shedding of small, round-structured virus particles in stools of patients of outbreaks of food-poisoning from raw oysters. Microbiol Immunol. 1991;35:83–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1991.tb01536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang X, Graham D Y, Wang K, Estes M K. Norwalk virus genome cloning and characterization. Science. 1990;250:1580–1583. doi: 10.1126/science.2177224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang X, Wang J, Graham D Y, Estes M K. Detection of Norwalk virus in stool by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2529–2534. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.10.2529-2534.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang X, Wang M, Wang K, Estes M K. Sequence and genomic organization of Norwalk virus. Virology. 1993;195:51–61. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapikian A, Estes M, Chanock M. Norwalk group viruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe B N, Howley P M, Chanock R M, Melnick J L, Monath T P, Roizman B, Straus S E, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 783–810. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan J E, Goodman R A, Schonberger L B, Lippy E C, Gary G W. Gastroenteritis due to Norwalk virus: an outbreak associated with a municipal water system. J Infect Dis. 1982;146:190–197. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lambden P R, Caul E O, Ashley C R, Clarke I N. Sequence and genomic organization of a human small round-structured (Norwalk-like) virus. Science. 1993;259:516–519. doi: 10.1126/science.8380940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawson H W, Braun M M, Glass R I, Stine S E, Monroe S S, Atrash H K, Lee L E, Englender S J. Waterborne outbreak of Norwalk virus gastroenteritis at a southwest US resort: role of geological formations in contamination of well water. Lancet. 1991;337:1200–1204. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92868-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leon R D, Matsui S M, Baric R S, Herrmann J E, Blacklow N R, Greenberg H B, Sobsey M D. Detection of Norwalk virus in stool specimens by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction and nonradioactive oligoprobes. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:3151–3157. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.12.3151-3157.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levett P N, Gu M, Luan B, Fearon M, Stubberfield J, Jamieson F, Petric M. Longitudinal study of molecular epidemiology of small round-structured viruses in a pediatric population. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1497–1501. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1497-1501.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maguire A J, Green J, Brown D W G, Desselberger U, Gray J J. Molecular epidemiology of outbreaks of gastroenteritis associated with small round-structured viruses in East Anglia, United Kingdom, during the 1996–1997 season. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:81–89. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.1.81-89.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuno S, Sawada R, Kimura K, Suzuki H, Yamanishi S, Shinozaki K, Sugieda M, Hasegawa A. Sequence analysis of NLV in fecal specimens from an epidemic of infantile gastroenteritis, October to December 1995, Japan. J Med Virol. 1997;52:377–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moe C L, Gentsch J, Ando T, Grohmann G, Monroe S S, Jiang X, Wang J, Estes M K, Seto Y, Humphrey C, Stine S, Glass R I. Application of PCR to detect Norwalk virus in fecal specimens from outbreaks of gastroenteritis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:642–648. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.642-648.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakayama M, Ueda Y, Kawamoto H, Han-Jun Y, Saito K, Hishio O, Ushijima H. Detection and sequencing of Norwalk-like viruses from stool samples in Japan using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction amplification. Microbiol Immunol. 1996;40:317–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1996.tb03343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson M, Wright T L, Case M A, Martin D R, Glass R I, Sangal S P. A protracted outbreak of foodborne viral gastroenteritis caused by Norwalk or Norwalk-like agent. J Environ Health. 1992;54:50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noel J S, Ando T, Leite J P, Green K Y, Dingle K E, Estes M K, Seto Y, Monroe S S, Glass R I. Correlation of the patient immune responses with genetically characterized small round-structured viruses involved in outbreaks of nonbacterial acute gastroenteritis in the United States, 1990 to 1995. J Med Virol. 1997;53:372–383. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199712)53:4<372::aid-jmv10>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noel J S, Fankhauser R L, Ando T, Monroe S S, Glass R I. Identification of a distinct common strain of “Norwalk-like viruses” having a global distribution. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1334–1344. doi: 10.1086/314783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Norcott J P, Green J, Lewis D, Estes M K, Barlow K L, Brown D W G. Genomic diversity of small round structured viruses in the United Kingdom. J Med Virol. 1994;44:280–286. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890440312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Otsu R. Outbreaks of gastroenteritis caused by SRSVs from 1987 to 1992 in Kyushu, Japan: four outbreaks associated with oyster consumption. Eur J Epidemiol. 1999;15:175–180. doi: 10.1023/a:1007543924543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parashar U D, Dow L, Fankhauser R L, Humphrey C D, Miller J, Ando T, Williams K S, Eddy C R, Noel J S, Ingram T, Bresee J S, Monroe S S, Glass R I. An outbreak of viral gastroenteritis associated with consumption of sandwiches: implication for the control of transmission by food handlers. Epidemiol Infect. 1998;121:615–621. doi: 10.1017/s0950268898001150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saito H, Saito S, Kamada K, Harata S, Sato H, Morita M, Miyajima Y. Application of RT-PCR designed from the sequence of the local SRSV strain to the screening in viral gastroenteritis outbreaks. Microbiol Immunol. 1998;42:439–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1998.tb02307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sekine S, Okada S, Hayashi Y, Ando T, Terayama T, Yabuuchi K, Miki T, Ohashi M. Prevalence of small round structured virus infections in acute gastroenteritis outbreaks in Tokyo. Microbiol Immunol. 1989;33:207–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1989.tb01514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stene-Johansen K, Grinde B. Sensitive detection of human caliciviridae by RT-PCR. J Med Virol. 1996;50:207–213. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199611)50:3<207::AID-JMV1>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugieda M, Nakajima K, Nakajima S. Outbreaks of Norwalk-like virus-associated gastroenteritis traced to shellfish: coexistence of two genotypes in one specimen. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;116:339–346. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800052663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor M B, Schildhauer C I, Parker S, Grabow W O K, Jiang X, Estes M K, Cubitt W D. Two successive outbreaks of SRSV associated gastroenteritis in South Africa. J Med Virol. 1993;41:18–23. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890410105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vinje J, Koopmans M P G. Molecular detection and epidemiology of small round-structured viruses in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in the Netherlands. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:610–615. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.3.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vinje J, Altena S A, Koopmans M P G. The incidence and genetic variability of small round-structured viruses in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in the Netherlands. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1374–1378. doi: 10.1086/517325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang J, Jiang X, Madore H P, Gray J, Desselberger U, Ando T, Seto Y, Oishi I, Lew J F, Green K Y, Estes M K. Sequence diversity of small, round-structured viruses in the Norwalk virus group. J Virol. 1994;68:5982–5990. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5982-5990.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolfaardt M, Taylor M B, Grabow W O K, Cubitt W D, Jiang X. Molecular characterisation of small round structured viruses associated with gastroenteritis in South Africa. J Med Virol. 1995;47:386–391. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890470415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wright P J, Gunesekere I C, Doultree J C, Marshall J A. Small round-structured (Norwalk-like) viruses and classical human caliciviruses in southeastern Australia, 1980–1996. J Med Virol. 1998;55:312–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamazaki K, Oseto M, Seto Y, Utagawa E, Kimoto T, Minekawa Y, Inouye S, Yamazaki S, Okuno Y, Oishi I. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction detection and sequence analysis of small round-structured viruses in Japan. Arch Virol. 1996;12:271–276. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6553-9_29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]