Abstract

Objectives

Informal caregivers often experience a restriction in occupational balance. The self-reported questionnaire on Occupational Balance in Informal Caregivers (OBI-Care) is a measurement instrument to assess occupational balance in informal caregivers. Measurement properties of the German version of the OBI-Care had previously been assessed in parents of preterm infants exclusively. Thus, the aim of this study was to examine the measurement properties of the questionnaire in a mixed population of informal caregivers.

Methods

A psychometric study was conducted, applying a multicenter cross-sectional design. Measurement properties (construct validity, internal consistency, and interpretability) of each subscale of the German version of the OBI-Care were examined. Construct validity was explored by assessing dimensionality, item fit and overall fit to the Rasch model, and threshold ordering. Internal consistency was examined with inter-item correlations, item-total correlations, Cronbach’s alpha, and person separation index. Interpretability was assessed by inspecting floor and ceiling effects.

Results

A total of 196 informal caregivers, 171 (87.2%) female and 25 (12.8%) male participated in this study. Mean age of participants was 52.27 (±12.6) years. Subscale 1 was multidimensional, subscale 2 and subscale 3 were unidimensional. All items demonstrated item fit and overall fit to the Rasch model and displayed ordered thresholds. Cronbach’s Alpha and person separation index values were excellent for each subscale. There was no evidence of ceiling or floor effects.

Conclusions

We identified satisfying construct validity, internal consistency, and interpretability. Thus, the findings of this study support the application of the German version of the OBI-Care to assess occupational balance in informal caregivers.

Introduction

Persons with an impairment or a disease, such as preterm infants or persons with dementia, rely on the support and care of informal caregivers. Informal caregivers are defined as close family members, relatives or friends that provide unpaid care [1, 2]. Informal caregivers often experience physical and psychological burden, stress, and discomfort [1, 3–7]. Moreover, informal caregiving leads to a restriction of meaningful activities for oneself which affects one’s occupational balance [5, 8, 9].

Occupational balance is defined as a subjective balance between meaningful activities in different life areas, such as self-care, leisure time or productivity. Meaningful activities are characterized by having a specific purpose to a person and include activities a person does, wants to or has to do [10].Occupational balance is of high importance due to its association with health and well-being [11–14]. Its direct and indirect effects on health and quality of life could recently be confirmed [14]. Previous studies identified restricted occupational balance in informal caregivers [5, 8, 9, 15–20] and the need for interventions to improve their occupational balance [5, 8, 9]. Additionally, maintaining or improving informal caregivers’ occupational balance might have positive effects on their health and well-being [9, 20–22]. For example, a study reported an association between parents’ occupational balance and health and well-being of the child they cared for [22].

Therefore, it is important to address and assess occupational balance in informal caregivers. Due to subjectivity of occupational balance, a self-evaluation of one’s occupational balance is needed [23, 24]. Self-reported outcome measures, such as caregiver-reported questionnaires are required for self-evaluation [25]. These outcome measures consider the perspectives of the persons concerned and thus generate outcomes that are meaningful to them [25–28]. Additionally, self-reported outcome measures can be completed regardless of location and without the assistance of health professionals and are therefore inexpensive [29].

Reliable and valid outcome measures are prerequisites to assess deviations of occupational balance of informal caregivers, to set occupational balance interventions and to measure the effectiveness of these interventions [25]. However, self-reported outcome measures must comply with defined measurement properties, such as construct validity, internal consistency, and interpretability, to generate reliable and valid measurement outcomes [25, 30, 31]. Construct validity ensures accordance among scores of the outcome measure and existing knowledge or hypothesis, internal consistency ensures interrelatedness among a scale’s items and interpretability ensures assignment of qualitative meaning in clinical practice [25, 30].

Traditionally, examination of measurement properties has been guided by classical test theory (CTT). However, CTT methods to examine measurement properties have limitations. Item response theory approaches, such as analyses with a Rasch model, have been found to show advantages over CCT [32–35]. The Rasch model defines the probability that a person will answer an item correctly, given a specified person ability and item difficulty. Thus, the Rasch model provides a powerful approach to determine the coherence between the construct to be measured, and the outcome measure [32–34, 36].

Measurement instruments on occupational balance exist. However, these measurement instruments were not specifically developed with and validated in a sample population of informal caregivers [37, 38]. The self-reported questionnaire on Occupational Balance in Informal Caregivers (OBI-Care [37]) is a generic measurement instrument to assess occupational balance in informal caregivers [37]. It was specifically developed with parents of preterm infants, who are considered to be informal caregivers. A German version of the OBI-Care was developed first and subsequently translated into English, only the German version is validated. Previous analyses of the measurement properties of the German version in a sample of parents of preterm infants demonstrated construct validity and internal consistency [37]. However, measurement properties of the German version of the OBI-Care have not been examined in a mixed population of informal caregivers, such as caregivers of persons of different ages and diagnoses [37]. The exploration of its measurement properties in a mixed population of informal caregivers is required to ensure its generic applicability to assess occupational balance in a wider range of informal caregivers.

Thus, the aim of this study was to examine construct validity, internal consistency, and interpretability of the German version of the OBI-Care in a mixed population of informal caregivers.

Methods

Design

We conducted a psychometric study, applying a multicenter cross-sectional study design. Measurement properties of the German version of the OBI-Care were analyzed. Specifically, construct validity, internal consistency and interpretability were addressed. This study was part of a larger study, the Occupational Balance Project of Informal caregivers (TOPIC).

Data collection

From September 2016 to July 2020, numerous strategies were applied to recruit informal caregivers for this multicenter study in Austria. These were personal recruitment in participating centers and self-help groups as well as electronic recruitment through posts on social media (Table 1).

Table 1. Recruitment process.

| Recruitment type | Participating centers and self-help groups |

|---|---|

| Personal recruitment (paper survey) | University Hospital Krems, University Hospital St. Pölten, University Hospital Tulln, Hospital Amstetten, Hospital Mistelbach, Hospital Wiener Neustadt, Hospital Zwettl, Rehabilitationcenter Kids Chance Bad Radkersburg, Niederösterreichisches Hilfswerk, self-help groups for informal caregivers of Dachverband für Selbsthilfegruppen Österreich |

| Online recruitment (electronic survey) | Self-help groups for informal caregivers of Dachverband für Selbsthilfegruppen Österreich |

Informal caregivers of persons treated in one of the participating centers and informal caregivers of participating self-help groups were informed about study procedures verbally and in writing by the principal investigator, study assistants, health professionals, including therapists and nurses and self-help group leaders. Subsequently, potential participants were asked to participate in this study and to fill in the paper survey (personal recruitment).

Additionally, informal caregivers were invited electronically to participate in this study. Therefore, the principal investigator, study assistants and self-help group leaders shared written information and a video about study procedures as well as the electronic survey on social media and on the homepages of their institutions (electronic recruitment).

Inclusion criteria were informal caregivers i) who provided informal care for family members, relatives, or friends at the time of participation and ii) with sufficient German reading and writing skills. Exclusion criteria were underaged (≤ 18 years old) informal caregivers. No action was taken to recruit a sample that is representative of the population of informal caregivers in Austria.

Sample size was defined according to recommendations for Rasch analyses, were ten observations (cases) for each item in each category are required, whereby observations do not have to be individual cases [39].

Data collection instruments

Participants filled in the paper (personal recruitment) or the electronic (electronic recruitment) survey, digitalized with the program Enterprise Feedback Suite Survey [40], of a set of self-reported questionnaires [41–46] including the German version of the OBI-Care and the following sociodemographic data relevant for this study: informal caregivers’ sex, age, caring effort, caring activities and the number of persons to be cared for as well as sex and age of the persons to be cared for. The OBI-Care consists of 22 items. Each item has a five-choice response scale, ranging from 1, very satisfied to 5, very dissatisfied. Items are summarized in three subscales. Subscale 1 (occupational areas) asks for the satisfaction with the extent of one’s activities. Subscale 2 (occupational characteristics) asks for the characteristics and effects of one’s activities. Subscale 3 (occupational resilience) asks for the adaptability of one’s activities (Table 2). The subscales represent multidimensionality and recently identified dimensions of occupational balance. Sumscores are calculated for each subscale by summating according raw item values [37].

Table 2. Subscales and items of the OBI-Care [37].

| Subscale 1 | Satisfaction with … |

| Item_1a | household |

| Item_1b | caring for others |

| Item_1c | life management |

| Item_1d | physical activity / sports |

| Item_1e | social contacts |

| Item_1f | health and well-being |

| Item_1g | leisure |

| Item_1h | sleep |

| Item_1i | job, further education and training |

| Subscale 2 | Satisfaction with … |

| Item_2a | occupations you do on your own initiative and those you do because of others |

| Item_2b | usual and unusual daily routines |

| Item_2c | predictable and unpredictable occupations |

| Item_2d | important and less important occupations |

| Item_2e | physically demanding and less physically demanding occupations |

| Item_2f | mentally demanding and less mentally demanding occupations |

| Item_2g | indoor and outdoor occupations |

| Subscale 3 | Satisfaction with … |

| Item_3a | options to change the order of your occupations |

| Item_3b | options to spend more time on some occupations and less time on others |

| Item_3c | options to gather required information to perform new occupations |

| Item_3d | options to develop required skills to perform new occupations |

| Item_3e | options to continue to pursue occupations that are meaningful to you |

| Item_3f | options to find new occupations that are meaningful to you |

Abbreviations: OBI-Care = Occupational Balance in Informal Caregivers Questionnaire

Data analyses

Data was entered in a data file and analyzed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS [47]) and Rasch Unidimensional Measurement Model 2030 (RUMM 2030 [48]). SPSS was used for factor and correlation analyses, RUMM 2030 for analyses with a Rasch Model. Participants who did not fill in the OBI-Care completely were excluded from analyses. Analyses were conducted for each subscale of the OBI-Care. Alpha’s (α) level of significance was set at 0.05. For multiple testing, Bonferroni adjustment was applied [49, 50].

Descriptive analyses

Descriptive analyses were carried out to describe sociodemographic data of informal caregivers and persons to be cared. Descriptive analyses included the calculation of means and standard deviations for normal distributed data and medians and interquartile ranges for non-distributed data as well as frequencies and percentages.

Examination of psychometric properties

Dimensionality testing and different analyses with a Rasch model were conducted to assess construct validity [34, 51–57]. Dimensionality was examined by factor analyses. Therefore, principal component analysis was applied to extract components and their eigenvalues. Components with eigenvalues ≥ 1 were interpreted as an independent factor. One identified factor was interpreted as unidimensionality of a scale, factors ≥ 2 as multidimensionality. Subscales should be unidimensional to guarantee that the included items measure the same construct [25, 52]. Furthermore, item fit residual statistics and item-trait interaction chi-square statistics were analyzed to determine item fit and overall fit to the Rasch model. Non-significant item fit residuals (-2.5 to 2.5) and a mean item fit residual close to zero with a standard deviation close to one demonstrate an item fit. Non-significant chi-square values with a total chi-square probability value greater than 0.05 indicate overall fit [34, 49, 51, 56, 58, 59]. Moreover, threshold ordering, and the representation of response categories were examined by exploring threshold maps and threshold probability curves. Ordered thresholds indicate that the item’s response categories operate appropriately [34, 49, 51, 56].

Correlation analyses were conducted to assess internal consistency. These were inter-item correlations, item-total correlations, Cronbach’s α and the person separation index (PSI [25, 50]). Inter-item correlations between 0.2 and 0.5 and Cronbach’s α between 0.70 and 0.90 display that items measure the same construct and their appropriate allocation to the scale. Inter-item correlations > 0.7 indicate that the items measure almost the same and one of them might be deleted. Item-total correlations of ≥ 0.3 and a PSI ≥ 0.7 imply that the items discriminate between persons with different abilities [25, 50].

Interpretability was examined by the inspection of floor and ceiling effects [25]. Floor and ceiling effects are displayed when a high proportion (determined as 15%) of the sample population achieves the lowest (nine points for subscale 1, seven points for subscale 2 and six points for subscale 3) or highest score (45 points for subscale 1, 35 points for subscale 2 and 30 points for subscale 3) of an outcome measure. Floor and ceiling effects pose a problem in clinical practice, since persons that already achieved the lowest or highest score at baseline, cannot show any deterioration or improvement at follow up [25, 60].

Ethical considerations

The current study was approved by the ethics committee of Lower Austria. Participants confirmed their voluntarily participation by returning the paper survey or completing the electronic survey.

Results

Participants

In total, 217 informal caregivers participated in this study. Twenty-one participants were excluded due to missing data. Finally, data of 196 informal caregivers were included for analyses, extracted from 107 (55%) electronic surveys and 89 (45%) paper surveys. Sociodemographic data of informal caregivers and persons to be cared for are presented in Table 3. Persons to be cared for had different health conditions and diagnoses, such as cerebral palsy, dementia, cancer, or diabetes.

Table 3. Sociodemographic data.

| Informal caregivers | Female | Male | Total |

| Sex | 171 (87.2%) | 25 (12.8%) | 196 (100%) |

| Mean age in years (±SD) | 51.5 (±12.0) | 57.7 (±15.3) | 52.3 (±12.6) |

| Caring activities for more than one person n (%) | 80 (46.8%) | 12 (48.0%) | 92 (46.9) |

| Caring effort n (%) a | |||

| low | 35 (20.5%) | 7 (28.0%) | 42 (21.4%) |

| high | 135 (78.9%) | 18 (72.0%) | 153 (78.1%) |

| not specified | 1 (0.6%) | - | 1 (0.5%) |

| Caring activities n (%) b | |||

| body care and hygiene | 138 (80.7%) | 17 (68.0%) | 155 (79.1%) |

| household activities | 153 (89.5%) | 24 (96.0%) | 177 (90.3%) |

| cooking | 139 (81.3%) | 15 (60.0%) | 154 (78.6%) |

| feeding activities | 117 (68.4%) | 13 (52.0%) | 130 (66.3%) |

| participation in society, contact with relatives and friends | 126 (73.7%) | 15 (60.0%) | 141 (71.9%) |

| further activities | 83 (48.5%) | 15 (60.0%) | 98 (50.0%) |

| Persons to be cared for | Female | Male | Total |

| Sex | 104 (52.3%) | 90 (47.7%) | 194 (99.0%) |

| Median age in years (IQR) | 77.0 (76) | 62.0 (61) | 68.0 (68) |

Abbreviations

a = single answer

b = multiple answers; n = frequency; SD = Standard deviation

Construct validity

Overall, all subscales of the OBI-Care demonstrated good construct validity. Factor analyses showed that subscale 1 consists of two factors with eigenvalues ≥ 1. Thus, subscale 1 did not satisfy unidimensionality. Subscale 2 and subscale 3 consisted of one component with an eigenvalue ≥ 1 each and therefore complied with unidimensionality (Table 4).

Table 4. Dimensionality.

| Subscale 1 | Subscale 2 | Subscale 3 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Eigenvaluea | Ca | Item | Eigenvalue | C | Item | Eigenvalue | C | |||||||

| total | % of VA | CUM % | 1 | 2 | total | % of VA | CUM % | 1 | total | % of VA | CUM % | 1 | |||

| Item_1a | 4.438 | 49.313 | 49.313 | 0.610 | 0.636 | Item_2a | 3.976 | 56.796 | 56.796 | 0.769 | Item_3a | 3.995 | 66.582 | 66.582 | 0.779 |

| Item_1b | 1.164 | 12.933 | 62.246 | 0.590 | 0.626 | Item_2b | 0.796 | 11.366 | 68.162 | 0.777 | Item_3b | 0.710 | 11.836 | 78.418 | 0.813 |

| Item_1c | 0.799 | 8.874 | 71.12 | 0.681 | 0.263 | Item_2c | 0.589 | 8.409 | 76.571 | 0.694 | Item_3c | 0.532 | 8.875 | 87.293 | 0.812 |

| Item_1d | 0.610 | 6.776 | 77.896 | 0.709 | -0.276 | Item_2d | 0.497 | 7.093 | 83.664 | 0.788 | Item_3d | 0.278 | 4.628 | 91.921 | 0.809 |

| Item_1e | 0.477 | 5.301 | 83.197 | 0.783 | -0.26 | Item_2e | 0.447 | 6.388 | 90.052 | 0.756 | Item_3e | 0.264 | 4.400 | 96.321 | 0.841 |

| Item_1f | 0.455 | 5.060 | 88.258 | 0.771 | -0.229 | Item_2f | 0.370 | 5.279 | 95.330 | 0.717 | Item_3f | 0.221 | 3.679 | 100 | 0.840 |

| Item_1g | 0.375 | 4.172 | 92.430 | 0.743 | -0.082 | Item_2g | 0.327 | 4.670 | 100 | 0.769 | |||||

| Item_1h | 0.368 | 4.085 | 96.515 | 0.707 | -0.163 | ||||||||||

| Item_1i | 0.314 | 3.485 | 100 | 0.701 | -0.263 | ||||||||||

Abbreviations

a = extraction method: principal component analysis; C = components; CUM = cumulative; VA = Variance

For all subscales, item fit residuals ranged between -2.5 and +2.5 and mean item fit residuals were close to zero with a standard deviation close to one. Chi square probability values for each subscale were greater than 0.05. Therefore, all values indicated item fit and overall fit to the Rasch model. Detailed results of Rasch analyses are provided in Table 5.

Table 5. Rasch analyses.

| Subscale 1 | mean item fit 0.267 (± 0.997) | chi-square probability 0.383 | |||

| item statistics a | fit statistics a | ||||

| Items | location | SE | residual* | chi-square b** | f-statistics b |

| Item_1a | 0.682 | 0.097 | 0.861 | 0.965 | 0.457 |

| Item_1b | 0.704 | 0.091 | 1.993 | 3.432 | 1.584 |

| Item_1c | 0.441 | 0.082 | 0.263 | 1.377 | 0.541 |

| Item_1d | -0.345 | 0.083 | 0.194 | 1.569 | 0.773 |

| Item_1e | -0.163 | 0.081 | -1.188 | 4.036 | 3.002 |

| Item_1f | -0.687 | 0.082 | -1.062 | 4.586 | 3.286 |

| Item_1g | -0.445 | 0.083 | -0.173 | 2.328 | 1.240 |

| Item_1h | -0.048 | 0.076 | 0.638 | 0.146 | 0.080 |

| Item_1i | -0.140 | 0.079 | 0.904 | 0.702 | 0.287 |

| Subscale 2 | mean item fit 0.406 (± 0.792) | chi-square probability 0.517 | |||

| item statistics a | fit statistics a | ||||

| Items | location | SE | residual* | chi-square c** | f-statistics c |

| Item_2a | -0.361 | 0.098 | 0.483 | 2.592 | 1.406 |

| Item_2b | -0.049 | 0.106 | -0.56 | 3.584 | 2.332 |

| Item_2c | -0.245 | 0.102 | 1.315 | 1.223 | 0.603 |

| Item_2d | -0.419 | 0.105 | -0.028 | 1.653 | 1.060 |

| Item_2e | 0.200 | 0.098 | 0.184 | 0.855 | 0.452 |

| Item_2f | 0.495 | 0.097 | 1.608 | 2.265 | 1.098 |

| Item_2g | 0.379 | 0.099 | -0.161 | 0.946 | 0.537 |

| Subscale 3 | mean item fit 0.076 (± 0.615) | chi-square probability 0.707 | |||

| item statistics a | fit statistics a | ||||

| Items | location | SE | residual* | chi-square d** | f-statistics d |

| Item_3a | 0.054 | 0.104 | 1.068 | 1.656 | 0.710 |

| Item_3b | -0.191 | 0.111 | 0.166 | 0.242 | 0.173 |

| Item_3c | 0.401 | 0.103 | 0.242 | 1.676 | 0.797 |

| Item_3d | 0.212 | 0.102 | 0.139 | 0.248 | 0.145 |

| Item_3e | -0.010 | 0.102 | -0.491 | 1.602 | 1.027 |

| Item_3f | -0.466 | 0.097 | -0.664 | 3.517 | 2.422 |

Abbreviations

a = rounded to three decimals

b = Bonferroni adjusted probability level = 0.001111

c = Bonferroni adjusted probability level = = 0.007143

d = Bonferroni adjusted probability level = 0.001667

* = Deviations from the recommended range of -2.5 to +2.5 indicating item misfit are bold

** = Bonferroni adjusted statistically significant deviations indicating overall misfit are bold; p = probability; SE = Standard error

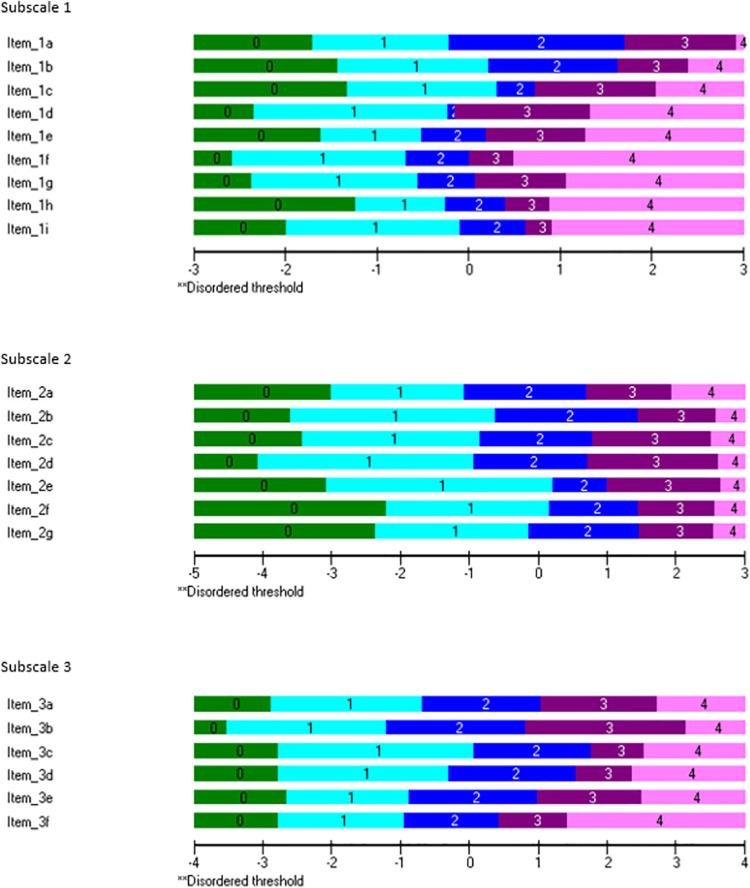

All items of each subscale showed ordered thresholds. Additionally, all response categories were represented (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Ordered thresholds indicate that the item’s response categories operate appropriate.

Internal consistency

Except for three item pairs of subscale 3, all items satisfied criteria for inter-item correlations (< 0.70). Inter-item correlations for item 3a and item 3b, item 3c and item 3d as well as for item 3e and item 3f indicated redundancy among the items (> 0.70). However, these items were only statically redundant but not related to their content. Additionally, all items showed good item-total correlations (> 0.3), Cronbach’s α (0.7 to 0.9) and person separation indices (> 0.7). Thus, all subscales demonstrated internal consistency. Detailed results are presented in Table 6.

Table 6. Correlation analyses, PSI and Cronbach’s α.

| Sub-scale 1 | Inter-Item Correlation * | PSI | Cronbach‘s α | ||||||||

| 0.861 | 0.868 | ||||||||||

| Item | Item_1a | Item_1b | Item_1c | Item_1d | Item_1e | Item_1f | Item_1g | Item_1h | Item_1i | Total-Item Correlation | Cronbach’s α if item deleted |

| Item_1a | 1.000 | 0.559 | 0.486 | 0.306 | 0.309 | 0.305 | 0.368 | 0.356 | 0.291 | 0.515 | 0.861 |

| Item_1b | 0.559 | 1.000 | 0.430 | 0.232 | 0.338 | 0.307 | 0.314 | 0.302 | 0.262 | 0.467 | 0.865 |

| Item_1c | 0.486 | 0.430 | 1.000 | 0.450 | 0.482 | 0.415 | 0.354 | 0.325 | 0.419 | 0.589 | 0.855 |

| Item_1d | 0.306 | 0.232 | 0.450 | 1.000 | 0.615 | 0.551 | 0.452 | 0.400 | 0.388 | 0.613 | 0.852 |

| Item_1e | 0.309 | 0.338 | 0.482 | 0.615 | 1.000 | 0.597 | 0.468 | 0.457 | 0.539 | 0.695 | 0.844 |

| Item_1f | 0.305 | 0.307 | 0.415 | 0.551 | 0.597 | 1.000 | 0.580 | 0.485 | 0.483 | 0.680 | 0.846 |

| Item_1g | 0.368 | 0.314 | 0.354 | 0.452 | 0.468 | 0.580 | 1.000 | 0.535 | 0.435 | 0.633 | 0.850 |

| Item_1h | 0.356 | 0.302 | 0.325 | 0.400 | 0.457 | 0.485 | 0.535 | 1.000 | 0.519 | 0.606 | 0.854 |

| Item_1i | 0.291 | 0.262 | 0.419 | 0.388 | 0.539 | 0.483 | 0.435 | 0.519 | 1.000 | 0.603 | 0.853 |

Abbreviations

* = inter-item correlations > 0.7 showing redundancy are bold; α = Alpha; PSI = person separation index

Interpretability

Exploration of floor and ceiling effects indicated interpretability. No significant floor and ceiling effects were found. For subscale 1, one (0.6%) person of the sample population achieved the lowest score (9) and the highest score (45). For subscale 2, none (0.0%) of the participants reached the lowest score (7) and two (1.1%) reached the highest score (35). For subscale 3, two (1.1%) persons scored the lowest score (6) and three (1.7%) the highest score (30).

Discussion

Within this study we examined psychometric properties of the German version of the OBI-Care in a sample population of informal caregivers.

Construct validity and internal consistency of the German version of the OBI-Care have already been examined in one of our previous studies [37]. However, the results of both studies differ partly and to our knowledge this is the first time that measurement properties of the OBI-Care have been examined in another population of informal caregivers.

As part of construct validity, we identified multidimensionality of subscale 1. This result does not comply with results of our previous studies, where subscale 1 displayed to be unidimensional [37]. However, it should be pointed out that we interpreted components with eigenvalues ≥ 1 as an independent factor. There is no uniform definition as to which value the eigenvalue has to exceed to be defined as a factor [25]. In other studies eigenvalues are defined as an independent factor from ≥ 3 onwards [55, 61]. Taking this definition into account, subscale 1 would consist of only one factor and be unidimensional. Additionally, to our knowledge the OBI-Care is the first occupational balance measure that considers multidimensionality of occupational balance in terms of measurement properties by using subscales [24, 37]. Thus, further analyses on the subscales of the OBI-Care are warranted.

Examination of internal consistency indicated that item 3a on changed chronology and item 3b on adapted time expenditure as well as item 3e on perpetuating occupations and item 3f on finding new occupations were statistically redundant. This result differs from our previous study [37]. It is possible that it is not important for informal caregivers which kind of meaningful occupations and in which order or amount of time they are performed, as long as the performance is possible. Inter-item correlations for item 3c on knowledge gathering and item 3d on skills acquisition indicated redundancy as well. Within our previous study we came to the same conclusion [37]. Thus, we believe that participants do not differ between knowledge gathering and skills acquisition. Supplementing these items with an example might enhance comprehensibility of the items.

Since occupational balance is a latent construct, it cannot be assessed directly [23]. Additionally, there is no consent how to assess occupational balance. In line with other existing occupational balance measures [62, 63], items of the OBI-Care ask for satisfaction with manifest components of occupational balance. Another occupational balance measure asks for the ability to perform manifest components of occupational balance [23]. Lack of consensus on the conceptualization and dimensions of occupational balance [24, 64] leads to inconsistent occupational balance measures and uncertainty how to measure occupational balance. Therefore, further studies on the conceptualization and dimensions of occupational balance are required.

The examination of interpretability of the OBI-Care is novel and thus provides new findings on the application of the OBI-Care in clinical practice. However, by calculating floor and ceiling values we determined the OBI-Care’s capability to measure the full range of occupational balance exclusively. Further explorations on interpretability, such as cut off values and minimal important change are recommended [25, 37].

Previous studies indicate that caregivers’ occupational balance and the engagement in meaningful activities might have an impact on caregivers’ subjective health and wellbeing as well as on subjective health and well-being of the persons to be cared for [5, 8, 9, 20, 21]. Thus, it is recommended that health professionals, such as occupational therapists, support informal caregivers’ engagement in meaningful activities and thereby strengthen their occupational balance.

Strengths and limitations

This study shows several strengths and limitations. Construct validity, internal consistency, and interpretability present essential components of psychometric properties. However, further studies are warranted to examine other psychometric properties, such as responsiveness [25]. The examination of psychometric properties using analyses with a Rasch model facilitates the identification of measurement inadequacies that might not be detected by classical test theory and thus provides a powerful alternative [32–34].

We examined psychometric properties in a mixed sample population of informal caregivers to ensure applicability independent of the caregivers. The examination of measurement properties might be replicated in diverse populations characterized by informal caregivers of people with specific diagnoses, such as dementia. We examined psychometric properties of the German version of the OBI-Care exclusively. Therefore, an examination of the existing English version of the OBI-Care [37] is required.

Additionally, the multicenter design and numerous recruitment strategies led to a high diversity of persons to be cared for. However, it should be noted that 87.2% of informal caregivers included in this study were female. Analyses within a sample with more male informal caregivers might differ. Differences in the burden perceived by female and male informal caregivers have been identified previously [65]. Additionally, occupational balance has been found to differ in women and men [66, 67]. Moreover, our study supports findings of previous studies that informal care is still mainly provided by women [68, 69] and thus indicate the consideration of gender specific research on informal caregivers. Furthermore, it has to be considered that the application of numerous recruitment strategies (personal and online recruitment) may have led to potential bias [70].

Conclusion

The German version of the OBI-Care demonstrates construct validity, internal consistency, and interpretability. Thus, the OBI-Care can be applied to measure occupational balance in informal caregivers and to assess effectiveness of occupational balance interventions for informal caregivers.

Acknowledgments

We thank participants for their important contribution to this study. Additionally, we gratefully acknowledge the support of data collection by health professionals of participating centers and members of participating self-help groups for informal caregivers. We also thank our collaboration partners Niederösterreichische Gesundheitsagentur, Karl Landsteiner University of Health Sciences, niederösterreichisches Hilfswerk, Kids Chance Neurorehabilitation Bad Radkersburg and Dachverband für Selbsthilfegruppen Österreich. Moreover, the and language editing by Karin Simpson-Parker is gratefully acknowledged.

Data Availability

Participants did not give consent on data sharing. Therefore, in accordance with the European General Data Protection Regulation and the competent ethics committee, only blinded data are available from the Ethics Committee of lower Austria or the IMC University of Applied Sciences Krems, upon reasonable request. Contact information for requests on data sharing are the following: Ethics Committee of lower Austria, Amt der NÖ Landesregierung, Abteilung Gesundheitswesen, Landhausplatz 1, Haus 15B, 3109 St. Pölten, Austria; E-Mail: post.ethikkommission@noel.gv.at IMC University of Applied Sciences Krems, Forschungsservice, Piaristengasse 1, 3500 Krems, Austria; E-Mail: forschungsservices@fh-krems.ac.at.

Funding Statement

The project was partly funded by Niederösterreichischer Gesundheits- und Sozialfonds. Url of the funder's website: https://www.noegus.at/. Niederösterreichischer Gesundheits- und Sozialfonds had no influence on the study design and manuscript content. Funding was received by MD. A part of the salary of two authors (MD and CW) was covered by the project costs. There was no additional external funding received for this study.

References

- 1.Zwar L, König H-H, Hajek A. Psychosocial consequences of transitioning into informal caregiving in male and female caregivers: Findings from a population-based panel study. Social Science & Medicine. 2020;264:113281. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denham AMJ, Wynne O, Baker AL, Spratt NJ, Turner A, Magin P, et al. An online survey of informal caregivers’ unmet needs and associated factors. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0243502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dam AEH, van Boxtel MPJ, Rozendaal N, Verhey FRJ, de Vugt ME. Development and feasibility of Inlife: A pilot study of an online social support intervention for informal caregivers of people with dementia. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(9):e0183386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen AP, Buckley MM, Cryan JF, Ní Chorcoráin A, Dinan TG, Kearney PM, et al. Informal caregiving for dementia patients: the contribution of patient characteristics and behaviours to caregiver burden. Age and Ageing. 2020;49(1):52–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afz128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nissmark S, Fänge A. Occupational balance among family members of people in palliative care. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2018:1–7. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2017.1329344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thorley EM, Iyer RG, Wicks P, Curran C, Gandhi SK, Abler V, et al. Understanding How Chorea Affects Health-Related Quality of Life in Huntington Disease: An Online Survey of Patients and Caregivers in the United States. The Patient—Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. 2018;11(5):547–59. doi: 10.1007/s40271-018-0312-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dür M, Brückner V, Oberleitner-Leeb C, Fuiko R, Matter B, Berger A. Clinical relevance of activities meaningful to parents of preterm infants with very low birth weight: A focus group study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGuire BK, Crowe TK, Law M, Vanleit B. Mothers of Children with Disabilities: Occupational Concerns and Solutions. OTJR Occupation, Participation and Health. 2004;24:54–63. doi: 10.1177/153944920402400203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mthembu TG, Brown Z, Cupido A, Razack G, Wassung D. Family caregivers’ perceptions and experiences regarding caring for older adults with chronic diseases. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016;46:83–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans KA. Definition of occupation as the core concept of occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther. 1987;41(10):627–8. Epub 1987/10/01. doi: 10.5014/ajot.41.10.627 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dür M, Steiner G, Stoffer MA, Fialka-Moser V, Kautzky-Willer A, Dejaco C, et al. Initial evidence for the link between activities and health: Associations between a balance of activities, functioning and serum levels of cytokines and C-reactive protein. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;65:138–48. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.12.015 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eakman AM. Relationships between Meaningful Activity, Basic Psychological Needs, and Meaning in Life: Test of the Meaningful Activity and Life Meaning Model. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health. 2013;33(2):100–9. doi: 10.3928/15394492-20130222-02 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eklund M, Orban K, Argentzell E, Bejerholm U, Tjörnstrand C, Erlandsson L-K, et al. The linkage between patterns of daily occupations and occupational balance: Applications within occupational science and occupational therapy practice. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017;24(1):41–56. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2016.1224271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park S, Lee HJ, Jeon B-J, Yoo E-Y, Kim J-B, Park J-H. Effects of occupational balance on subjective health, quality of life, and health-related variables in community-dwelling older adults: A structural equation modeling approach. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0246887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergstrom AL, Eriksson G, von Koch L, Tham K. Combined life satisfaction of persons with stroke and their caregivers: associations with caregiver burden and the impact of stroke. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-1 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3024212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crowe TK, Florez SI. Time use of mothers with school-age children: a continuing impact of a child’s disability. The American journal of occupational therapy: official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association. 2006;60(2):194–203. doi: 10.5014/ajot.60.2.194 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodgetts S, McConnell D, Zwaigenbaum L, Nicholas D. The impact of autism services on mothers’ occupational balance and participation. OTJR: occupation, participation and health. 2014;34(2):81–92. doi: 10.3928/15394492-20130109-01 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hornea J, Corrb S, Earlec S. Becoming a Mother: Occupational Change in First Time Motherhood. J Occup Sci. 2005;12(3):176–83. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2005.9686561 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagman P, Håkansson C. Occupational balance from the interpersonal perspective: A scoping review. Journal of Occupational Science. 2018:1–9. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2018.1512007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watford P, Jewell V, Atler K. Increasing Meaningful Occupation for Women Who Provide Care for Their Spouse: A Pilot Study. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health. 2019;39:153944921982984. doi: 10.1177/1539449219829849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SY, Grantham CH, Shelton S, Meaney-Delman D. Does activity matter: an exploratory study among mothers with preterm infants? Archives of women’s mental health. 2012;15(3):185–92. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0275-1 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3369538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orban K, Edberg A-K, Thorngren-Jerneck K, Önnerfält J, Erlandsson L-K. Changes in Parents’ Time Use and Its Relationship to Child Obesity. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2014;34(1):44–61. doi: 10.3109/01942638.2013.792311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dür M, Steiner G, Fialka-Moser V, Kautzky-Willer A, Dejaco C, Prodinger B, et al. Development of a new occupational balance-questionnaire: incorporating the perspectives of patients and healthy people in the design of a self-reported occupational balance outcome instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:45. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-12-45 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4005851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dür M, Unger J, Stoffer M, Dragoi R, Kautzky-Willer A, Fialka-Moser V, et al. Definitions of occupational balance and their coverage by instruments. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015;78(1):4–15. doi: 10.1177/0308022614561235 WOS:000351699100002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Vet HC, Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL. Measurement in Medicine: A Practical Guide. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stover AM, Haverman L, van Oers HA, Greenhalgh J, Potter CM, Ahmed S, et al. Using an implementation science approach to implement and evaluate patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) initiatives in routine care settings. Quality of Life Research. 2020. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02564-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiering B, de Boer D, Delnoij D. Patient involvement in the development of patient-reported outcome measures: a scoping review. Health Expectations. 2017;20(1):11–23. doi: 10.1111/hex.12442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gondivkar SM, Gadbail AR, Sarode SC, Gondivkar RS, Yuwanati M, Sarode GS, et al. Measurement properties of oral health related patient reported outcome measures in patients with oral cancer: A systematic review using COSMIN checklist. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(6):e0218833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gondivkar SM, Bhowate RR, Gadbail AR, Gondivkar RS, Sarode SC, Saode GS. Comparison of generic and condition-specific oral health-related quality of life instruments in patients with oral submucous fibrosis. Quality of Life Research. 2019;28(8):2281–8. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02176-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2010;63(7):737–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kartschmit N, Mikolajczyk R, Schubert T, Lacruz ME. Measuring Cognitive Reserve (CR)–A systematic review of measurement properties of CR questionnaires for the adult population. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(8):e0219851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Håkansson C, Wagman P, Hagell P. Construct validity of a revised version of the Occupational Balance Questionnaire. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2019:1–9. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2019.1660801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nguyen TH, Han H-R, Kim MT, Chan KS. An Introduction to Item Response Theory for Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement. The Patient—Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. 2014;7(1):23–35. doi: 10.1007/s40271-013-0041-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pallant JF, Tennant A. An introduction to the Rasch measurement model: An example using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;46(1):1–18. doi: 10.1348/014466506x96931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGrory S, Shenkin SD, Austin EJ, Starr JM. Lawton IADL scale in dementia: can item response theory make it more informative? Age and Ageing. 2014;43(4):491–5. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tennant A, McKenna SP, Hagell P. Application of Rasch Analysis in the Development and Application of Quality of Life Instruments. Value in Health. 2004;7:S22–S6. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.7s106.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dür M, Röschel A, Oberleitner-Leeb C, Herrmanns V, Pichler-Stachl E, Matter B, et al. Development and Validation of a Self-Reported Questionnaire to Assess Occupational Balance in Parents of Preterm Infants. PLoS ONE 16(11): e0259648. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0259648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dür M, Unger J, Stoffer M, Drăgoi R, Kautzky-Willer A, Fialka-Moser V, et al. Definitions of occupational balance and their coverage by instruments. London, England 2015. p. 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andrich D. An Expanded Derivation of the Threshold Structure of the Polytomous Rasch Model That Dispels Any “Threshold Disorder Controversy”. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2013;73:78–124. doi: 10.1177/0013164412450877 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Questback. Enterprise Feedback Suite Survey (EFS) 2018.

- 41.Fydrich T, Sommer G, Tydecks S, Brähler E. Fragebogen zur sozialen Unterstützung (F-SozU): Normierung der Kurzform (K-14). Z Med Psychol. 2009;18:43–8. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gräßel E Häusliche Pflegeskala. Deutschland: Vless; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kallus KW. Erholungs-Belastungs Fragebogen. Göttingen, Deutschland: Hogrefe; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laux L, Glanzmann P, Schaffner P, Spielberger CD. State-Trait-Angst-Depressions-Inventar. Deutschland, Weinheim: Beltz Test GmbH; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tröster H. Eltern-Belastungs-Inventar (EBI). Deutsche Version des Parenting Stress Index (PSI). Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ware JE Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical care. 1992;30(6):473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.IBM Corporation. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.00. Armonk, NY; 20192019.

- 48.Rumm-Laboratory. RUMM2030. Released in January 2010. License Restructure from January 2020. Australia, Duncraig; 20122010.

- 49.Andrich D, Marais I. A course in Rasch measurement theory: measuring in the educational, social and health sciences: Singapore: Springer; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dzingina M, Higginson IJ, McCrone P, Murtagh FEM. Development of a Patient-Reported Palliative Care-Specific Health Classification System: The POS-E. The Patient—Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. 2017;10(3):353–65. doi: 10.1007/s40271-017-0224-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tennant A, Conaghan PG. The Rasch measurement model in rheumatology: What is it and why use it? When should it be applied, and what should one look for in a Rasch paper? Arthritis Care & Research. 2007;57(8):1358–62. doi: 10.1002/art.23108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tennant A, Pallant J. Unidimensionality matters! (A tale of two Smiths?) 2006. 1048–51 p. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andrich D. Rating scales and Rasch measurement. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research. 2011;11(5):571–85. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bond TG, Fox CM. Applying the Rasch Model. Fundamental Measurement in the Human Science. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates,Inc.; 2007. 1–340 p. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang Y-J, Chen C-T, Lin G-H, Wu T-Y, Chen S-S, Lin L-F, et al. Evaluating the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire in Patients with Stroke: A Latent Trait Analysis Using Rasch Modeling. The Patient—Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. 2018;11(1):83–96. doi: 10.1007/s40271-017-0267-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rumm-Laboratory. Extenting the RUMM2030 Analysis. RUMM2030 Rasch Unidimensional Measurement Model. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hadžibajramović E, Schaufeli W, De Witte H. A Rasch analysis of the Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT). PLOS ONE. 2020;15(11):e0242241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Apon I, van Leeuwen N, Allori AC, Rogers-Vizena CR, Koudstaal MJ, Wolvius EB, et al. Rasch Analysis of Patient- and Parent-Reported Outcome Measures in the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) Standard Set for Cleft Lip and Palate. Value in Health. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2020.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ningrum E, Evans S, Soh S-E. Validation of the Indonesian version of the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: A Rasch analysis. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(4):e0215128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Franklin M, Mukuria C, Mulhern B, Tran I, Brazier J, Watson S. Measuring the Burden of Schizophrenia Using Clinician and Patient-Reported Measures: An Exploratory Analysis of Construct Validity. The Patient—Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. 2019;12(4):405–17. doi: 10.1007/s40271-019-00358-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Linacre J. A user’s quide to WINSTEP. Chicago: MESA Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Forhan M, Backman C. Exploring Occupational Balance in Adults with Rheumatoid Arthritis. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health. 2010;30(3):133–41. doi: 10.3928/15394492-20090625-01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wagman P, Håkansson C. Introducing the Occupational Balance Questionnaire (OBQ). Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy. 2014;21. doi: 10.3109/11038128.2014.900571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anaby DR, Backman CL, Jarus T. Measuring Occupational Balance: A Theoretical Exploration of Two Approaches. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2010;77(5):280–8. doi: 10.2182/cjot.2010.77.5.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Swinkels J, Tilburg Tv, Verbakel E, Broese van Groenou M. Explaining the Gender Gap in the Caregiving Burden of Partner Caregivers. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2017;74(2):309–17. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wagman P, Hakansson C. Exploring occupational balance in adults in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014;21(6):415–20. doi: 10.3109/11038128.2014.934917 WOS:000344362000002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Håkansson C, Ahlborg G. Perceptions of employment, domestic work, and leisure as predictors of health among women and men. Journal of Occupational Science. 2010;17(3):150–7. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2010.9686689 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nagl-Cupal M, Kolland F, Zartler U, Mayer H, Bittner M, Koller M, et al. Angehörigenpflege in Österreich. Einsicht in die Situation pflegender Angehöriger und in die Entwicklung informeller Pflegenetzwerke. Universität Wien: Bundesministerium für Soziales, Gesundheit, Pflege und Konsumentenschutz; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lopez Hartmann M, De Almeida Mello J, Anthierens S, Declercq A, Van Durme T, Cès S, et al. Caring for a frail older person: the association between informal caregiver burden and being unsatisfied with support from family and friends. Age and Ageing. 2019;48(5):658–64. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afz054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nayak M, K A N. Strengths and Weakness of Online Surveys. 2019;24:31–8. doi: 10.9790/0837-2405053138 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Participants did not give consent on data sharing. Therefore, in accordance with the European General Data Protection Regulation and the competent ethics committee, only blinded data are available from the Ethics Committee of lower Austria or the IMC University of Applied Sciences Krems, upon reasonable request. Contact information for requests on data sharing are the following: Ethics Committee of lower Austria, Amt der NÖ Landesregierung, Abteilung Gesundheitswesen, Landhausplatz 1, Haus 15B, 3109 St. Pölten, Austria; E-Mail: post.ethikkommission@noel.gv.at IMC University of Applied Sciences Krems, Forschungsservice, Piaristengasse 1, 3500 Krems, Austria; E-Mail: forschungsservices@fh-krems.ac.at.