Abstract

Background

In rituximab-treated patients with rheumatoid arthritis, humoral and cellular immune responses after two or three doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are not well characterised. We aimed to address this knowledge gap.

Methods

This prospective, cohort study (Nor-vaC) was done at two hospitals in Norway. For this sub-study, we enrolled patients with rheumatoid arthritis on rituximab treatment and healthy controls who received SARS-CoV-2 vaccines according to the Norwegian national vaccination programme. Patients with insufficient serological responses to two doses (antibody to the receptor-binding domain [RBD] of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein concentration <100 arbitrary units [AU]/mL) were allotted a third vaccine dose. Antibodies to the RBD of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein were measured in serum 2–4 weeks after the second and third doses. Vaccine-elicited T-cell responses were assessed in vitro using blood samples taken before and 7–10 days after the second dose and 3 weeks after the third dose from a subset of patients by stimulating cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells with spike protein peptides. The main outcomes were the proportions of participants with serological responses (anti-RBD antibody concentrations of ≥70 AU/mL) and T-cell responses to spike peptides following two and three doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT04798625, and is ongoing.

Findings

Between Feb 9, 2021, and May 27, 2021, 90 patients were enrolled, 87 of whom donated serum and were included in our analyses (69 [79·3%] women and 18 [20·7%] men). 1114 healthy controls were included (854 [76·7%] women and 260 [23·3%] men). 49 patients were allotted a third vaccine dose. 19 (21·8%) of 87 patients, compared with 1096 (98·4%) of 1114 healthy controls, had a serological response after two doses (p<0·0001). Time since last rituximab infusion (median 267 days [IQR 222–324] in responders vs 107 days [80–152] in non-responders) and vaccine type (mRNA-1273 vs BNT162b2) were significantly associated with serological response (adjusting for age and sex). After two doses, 10 (53%) of 19 patients had CD4+ T-cell responses and 14 (74%) had CD8+ T-cell responses. A third vaccine dose induced serological responses in eight (16·3%) of 49 patients, but induced CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses in all patients assessed (n=12), including responses to the SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2). Adverse events were reported in 32 (48%) of 67 patients and in 191 (78%) of 244 healthy controls after two doses, with the frequency not increasing after the third dose. There were no serious adverse events or deaths.

Interpretation

This study provides important insight into the divergent humoral and cellular responses to two and three doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in rituximab-treated patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A third vaccine dose given 6–9 months after a rituximab infusion might not induce a serological response, but could be considered to boost the cellular immune response.

Funding

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, Research Council of Norway Covid, the KG Jebsen Foundation, Oslo University Hospital, the University of Oslo, the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority, Dr Trygve Gythfeldt og frues forskningsfond, the Karin Fossum Foundation, and the Research Foundation at Diakonhjemmet Hospital.

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 vaccines have proven efficient and safe in the general population,1, 2 but a good vaccine response depends on a functional immune system that includes concerted B-cell and T-cell responses. Immunosuppressive medications, and particularly rituximab, an anti-CD20 B-cell-depleting therapy, are known to impair the immunogenicity of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines.3 Patients with rheumatoid arthritis on rituximab therapy have been reported to be at increased risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19,4, 5, 6, 7 and it is crucially important to evaluate their response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Observational data in small cohorts of patients with rheumatoid arthritis have indicated that rituximab impairs serological SARS-CoV-2 vaccine responses.8, 9, 10, 11 Previous reports have suggested that T cells are necessary for protection against severe COVID-19 in settings of low antibody titres,12 for rapid and efficient resolution of COVID-1913 and for protection against fatal outcomes in patients treated with anti-CD20 therapies for haematological malignancies.14 To date, sparse data exist regarding cellular responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in rituximab-treated patients with rheumatoid arthritis.11, 15 In the absence of a normal serological response, cellular immunity is of crucial interest in this patient group.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed for studies published in English between Jan 1, 2020, and Sept 29, 2021, using different combinations of the search terms, “Rheumatoid arthritis”, “vaccination”, “SARS-CoV-2”, “COVID-19”, “rituximab”, and “response”. Previous observational studies on vaccine responses in patients with rheumatoid arthritis were generally small, but indicated that rituximab impairs serological responses to vaccines, including SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Sparse information exists on T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and no data exist on three-dose SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in rituximab-treated patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Added value of this study

In this cohort of 87 patients with rheumatoid arthritis on rituximab treatment, only 19 (21·8%), compared with 1096 (98·4%) of 1114 healthy controls, had a serological response after two vaccine doses. Time between the last rituximab infusion and the first vaccine dose was significantly associated with vaccine response, with a median interval of about 9 months in responders. Cellular immune responses were present in more than half of patients after two doses. A third vaccine dose given to patients with insufficient serological responses to two doses was safe and elicited a robust T-cell response in all patients tested, despite inducing serological responses in only a small proportion of patients.

Implications of all the available evidence

If possible, patients should be vaccinated against COVID-19 before the initiation of rituximab therapy. For an optimal response, the interval between rituximab infusion and vaccination should be as long as possible, preferably at least 9 months. In rituximab-treated patients with rheumatoid arthritis, a cellular immune response might be present after vaccination in the absence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. A third vaccine dose given 6–9 months after a rituximab infusion might not induce a serological response but could be considered to boost the cellular immune response. The clinical significance of the cellular immune response in the absence of virus-specific antibodies remains to be elucidated. Alternative anti-rheumatic therapies might be considered in individual patients if repeated rituximab infusions preclude the development of protective anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

The utility of a third vaccine dose in immunocompromised patients, and in the general population, is an urgent question in the global medical community and for policy makers.16, 17 Whether patients with B-cell depletion who do not serologically respond to two vaccine doses will benefit from a third dose is unclear. A case series on rituximab-treated patients indicated limited benefit from a third dose.18

We therefore aimed to assess humoral and cellular responses and adverse events following two doses and three doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with rituximab.

Methods

Study design and participants

Nor-vaC is an ongoing, longitudinal, prospective, cohort study being conducted at two Norwegian hospitals with large specialist clinics: the Division of Rheumatology and Research at Diakonhjemmet Hospital, Oslo, and the Department of Gastroenterology at Akershus University Hospital, Oslo. Eligibility criteria are presented in the appendix (p 2). Eligible patients identified by hospital records received an invitation to participate in the study on Feb 15, 2021, before initiation of the national vaccination programme. This analysis includes rituximab-treated patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Healthy controls were blood donors and health-care workers from collaborating hospitals (Diakonhjemmet Hospital, Akershus University Hospital, and Oslo University Hospital) in Oslo, Norway. The study was approved by an independent ethics committee (Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics South East; reference numbers 235424, 135924, and 204104) and by appropriate institutional review boards. All patients and healthy controls provided written informed consent.

Procedures

All participants received SARS-CoV-2 vaccines according to the Norwegian national vaccination programme. Three SARS-CoV-2 vaccines were available: BNT162b2 (Pfizer–BioNtech), mRNA-1273 (Moderna), and ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AstraZeneca). The two mRNA vaccines were given with an interval of 3–6 weeks between the two doses. The ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine was withdrawn from the Norwegian vaccination programme on March 11, 2021, and all people who had received one dose of this vaccine received one of the mRNA vaccines as the second dose. The vaccines were administered to participants following a priority list given by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. According to the programme, people who had recovered from COVID-19 received one vaccine dose only. During the conduct of this study, patients with concentrations of antibodies against the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2 of less than 100 arbitrary units (AU)/mL after two vaccine doses were recruited into a separate study (EudraCT number 2021–003618–37) and allotted a third vaccine dose in July–August, 2021. Patients receiving a third dose were asked to pause their concomitant disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment 1 week before until 2 weeks after vaccination.

Informed consent forms and questionnaires were collected through the Services for Sensitive Data platform at the University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway. At baseline and approximately 14 days after the first, second, and third vaccine doses, participating patients were asked to complete questionnaires regarding: demographic data (eg, diagnosis, age, sex, weight, height, and smoking status); medication use; patient-reported disease activity; COVID-19-related questions (ie, symptoms, test results, and hospitalisation); pausing of medication at the time of vaccination; and adverse events after all doses. The date of the last rituximab infusion, the total number of rituximab infusions, disease duration, rituximab treatment duration, co-medications, and number of previous DMARDs were obtained from medical records by investigators at baseline. Disease activity (disease activity score in 28 joints, patient global assessment, and physician global assessment) was assessed 2–4 weeks after the second vaccine dose by investigators. Information about vaccination dates and vaccine types was obtained from the Norwegian Immunisation Registry, SYSVAK by investigators.19 Information regarding patients testing positive for COVID-19 before and during the study period was obtained from the Norwegian Surveillance System for Communicable Diseases by investigators.20 For 868 healthy controls, only information on vaccine date and type, sex, and age were collected. 246 controls (health-care workers at Diakonhjemmet Hospital and Akershus University Hospital) additionally answered detailed questionnaires on demographic data and adverse events at baseline and 14 days after each vaccine dose.

Antibodies to the full-length spike protein and the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 were measured 2–4 weeks after the second vaccine dose and 2–4 weeks after the third dose by use of an in-house bead-based method (appendix pp 3–4).21 We defined antibody concentrations higher than the second percentile of those from healthy individuals vaccinated with two doses, corresponding to concentrations of 70 AU/mL or more, as response.22 Concentrations of less than 5 AU/mL were defined as no response and concentrations of 5–69 AU/mL were defined as weak response. Calibration to the WHO international standard showed that 70 AU/mL corresponds to approximately 40 binding antibody units per mL.

Before the first vaccine dose, a subset of patients (n=20) and controls (n=20) were asked to provide blood samples for cellular analysis before and 7–10 days after the second vaccine dose. The number was based on the feasibility of conducting complex cellular analyses and the previous experience of the researchers conducting them. 12 of 20 patients were recipients of a third dose and additionally donated blood for cellular analyses 3 weeks after the third dose. Thawed peripheral blood mononuclear cells were stimulated with SARS-CoV-2 PepTivator spike protein peptides (Miltenyi Biotec; Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) of the wild-type or delta variant (B.1.617.2), which consisted of 15-mer sequences with 11 amino acids overlap covering the immunodominant parts of the spike protein, in the presence of costimulatory antibodies against CD28 and CD49d (0·5 μg/mL for both; BD Biosciences; Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and Brefeldin A (10 μg/mL; MilliporeSigma; Burlington, MA, USA). SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells were identified by dual expression of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and CD40-L (CD154) for CD4+ T cells and by single or dual intracellular expression of interferon-γ (IFNγ) and TNF for CD8+ T cells. All samples were acquired on an Attune NxT (Thermofischer; Waltham, MA, USA) flow cytometer and analysed by use of FlowJo software (version 10). For a detailed description of the methodology regarding T cells, please see the appendix (pp 5–6).

Objectives and outcomes

The two main objectives of this study were to assess (1) humoral and T-cell responses to two doses and three doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with rheumatoid arthritis on rituximab therapy compared with healthy controls and (2) changes in humoral and T-cell responses after a third vaccine dose given to patients with insufficent serological responses (anti-RBD <100 AU/mL) to two doses. Other objectives were to assess the safety of two-dose and three-dose vaccination and to identify predictors of serological response in patients.

The outcomes were: the proportions of participants with serological responses (anti-RBD antibody concentrations of >70 AU/mL) and T-cell responses to spike peptides following two and three doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines; the change in concentrations of anti-RBD antibodies and T-cell responses to spike peptides after the third dose; adverse events; and predictors of serological responses to two-dose and three-dose vaccination.

Statistical analysis

A formal sample size calculation was not done and all eligible patients willing to participate were included. Demographic data, adverse events, and serological responses were summarised by use of descriptive statistics. Comparisons of serological response between patients and controls were done by logistic regression. Adjustments were made for sex, age, and vaccine type. Comparison between pre-vaccination and post-vaccination samples in patients receiving a third vaccine dose was done by a Wilcoxon paired samples test. GraphPad Prism paired analysis and the Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test were used to compare the frequencies of antigen-specific T cells. Comparisons of potential risk factors between response groups were done by Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous variables and Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables. To assess predictors of serological response to vaccine doses, univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were done. Relevant variables were chosen by the investigators after a review of the existing literature. For multivariable model building, all factors with p values of less than 0·15 from univariable analyses, age, and sex were included. The final model was obtained with significant variables only by backward elimination of the least significant variable. Spearman correlation tests were used to compare T-cell responses versus age and the time since last rituximab infusion, to compare T-cell responses to wild-type spike protein versus delta spike protein, and to compare specific responses of CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells. All tests were two-sided and done at the 0·05 significance level. Analyses were done using Stata (version 16), GraphPad Prism (version 9), and R (version 3.4.4). The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT04798625.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

Between Feb 9, 2021, and May 27, 2021, 90 patients with rheumatoid arthritis being treated with rituximab were enrolled, 87 of whom (median age 60 years [IQR 55–67]; 69 [79·3%] women and 18 [20·7%] men) donated serum at a median of 16 days (IQR 12–21) after the second vaccine dose and were included in our analyses (table 1 ). In addition, control samples from 1114 healthy health-care providers and blood donors (median age 43 years [IQR 32–55]; 854 [76·7%] women and 260 [23·3%] men) were included. 56 (64·4%) of 87 patients used a conventional systemic DMARD concomitantly: methotrexate (n=42), leflunomide (n=9), sulfasalazine (n=4), or hydroxychloroquine (n=1). 14 (16·1%) patients used prednisolone as co-medication, all of whom took a dose of less than 10 mg/day. Most patients were either vaccinated with two doses of BNT162b2 (63 [72·4%]) or mRNA1273 (21 [24·1%]); three patients had had COVID-19 before vaccination and received only one vaccine dose (table 1). No patients developed COVID-19 after two-dose or three-dose vaccination.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Patients receiving at least two doses (n=87) | Patients receiving third dose (n=49) | Healthy controls receiving two doses (n=1114) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 60 (55–67) | 62 (56–67) | 43 (32–55) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 69 (79·3%) | 43 (87·8%) | 854 (76·7%) | |

| Male | 18 (20·7%) | 6 (12·2%) | 260 (23·3%) | |

| Body-mass index, kg/m2 | 25 (23–29) | 25 (22–28) | .. | |

| Current smoker* | 11 (12·6%) | 7 (14·3%) | 0 | |

| Vaccines | ||||

| Two doses of BNT162b2 | 63 (72·4%) | 39 (79·6%) | 625 (56·1%) | |

| Two doses of mRNA-1273 | 21 (24·1%) | 8 (16·3%) | 246 (22·1%) | |

| BNT162b2 plus mRNA-1273 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0·2%) | |

| ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 plus BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273 | 0 | 0 | 241 (21·6%) | |

| SARS-CoV-2 infection plus BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273* | 3 (3·4%) | 2 (4·1%) | 0 | |

| Rituximab monotherapy | 31 (35·6%) | 16 (32·7%) | .. | |

| Prednisolone use | 14 (16·1%) | 5 (10·2%) | .. | |

| Dose of prednisolone, mg/day | 5 (1) | 5 (2) | .. | |

| Methotrexate use | 42 (48·3%) | 22 (44·9%) | .. | |

| Dose of methotrexate, mg/week | 15 (6) | 14 (6) | .. | |

| Duration of rituximab therapy, years | 6 (3–9) | 6 (3–9) | .. | |

| Number of rituximab infusions | 9 (3–15) | 11 (4–16) | .. | |

| Number of previous DMARDs | 5 (3–7) | 5 (3–6) | .. | |

| CD19+ B cell count†‡, cells per μL | 28·9 (67·4) | 9·7 (20·7) | .. | |

| C-reactive protein concentration†§, mg/L | 3·8 (5·0) | 3·3 (4·5) | .. | |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate†§, mm/h | 11·5 (9·5) | 9·7 (5·7) | .. | |

| DAS28†¶ | 2·4 (1·1) | 2·1 (0·8) | .. | |

| Time between rituximab and first vaccine dose, days | 140 (87–224) | 100 (74–147) | .. | |

Data are median (IQR), n (%), or mean (SD). DAS28=disease activity score in 28 joints. DMARDs=disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

Available data only on health-care workers at Diakonhjemmet Hospital and Akershus University Hospital.

Assessments done after the second dose.

Data available for 58 patients receiving at least two doses and 40 patients receiving a third dose.

Data available for 66 patients receiving at least two doses and 40 patients receiving a third dose.

Data available for 65 patients receiving at least two doses and 39 patients receiving a third dose.

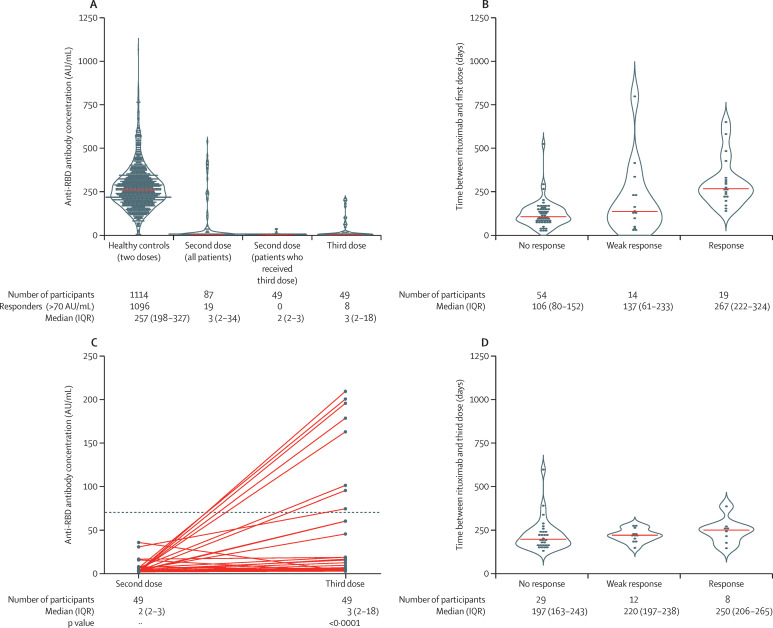

19 (21·8%) of 87 patients, compared with 1096 (98·4%) of 1114 healthy controls, had a serological response after two doses (p<0·0001; table 2 ). After two doses, 14 (16·1%) patients and 14 (1·3%) controls had a weak response, and 54 (62·1%) patients and four (0·4%) controls had no response (table 2; figure 1A ). The median time between the last rituximab infusion and the first vaccine dose was significantly longer in responders than in patients with a weak response or no response (table 3 ; figure 1B). Univariable logistic regression identified the interval between the last rituximab infusion and the first vaccine dose (per 100 days), CD19+ cell count, and vaccine type (mRNA-1273 compared with BNT162b2) to be significantly associated with humoral response after two doses (appendix p 8). In the multivariable logistic regression model, the interval between the last rituximab infusion and the first vaccine dose (per 100 days) and vaccine type (mRNA-1273 compared with BNT162b2) were significantly associated with serological response when adjusted for age and sex (appendix p 8).

Table 2.

Serological response to two and three vaccine doses in patients and healthy controls

| Healthy controls receiving two doses (n=1114) | Patients receiving at least two doses (n=87) | Patients receiving third dose (n=49) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No response* | 4 (0·4%) | 54 (62·1%) | 29 (59·2%) |

| Weak response* | 14 (1·3%) | 14 (16·1%) | 12 (24·5%) |

| Response* | 1096 (98·4%) | 19 (21·8%) | 8 (16·3%) |

| Anti-RBD antibody titre, AU/mL | 257 (198–327) | 3 (2–34) | 3 (2–18) |

Data are n (%) or median (IQR). AU=arbitrary units. RBD=receptor-binding domain.

Anti-RBD antibody concentrations of less than 5 AU/mL defined no response, of 5–69 AU/mL defined weak response, and of 70 AU/mL or more defined response.

Figure 1.

Humoral response to two and three vaccine doses

(A) Anti-RBD antibody concentrations in controls, patients who had received at least two doses, patients who had received two doses and would later receive a third, and patients who had received three doses. The violin illustrates the kernel probability density and the orange line indicates the median. Dots denote individual patients. (B) Time between last rituximab infusion and first vaccine dose according to response status in all patients after their second vaccine dose. The violin illustrates the kernel probability density and the orange line indicates the median. Dots denote individual patients. (C) Anti-RBD antibody concentrations after the second and third doses. Solid lines connect patients' two samples (circles). The horizontal dotted line indicates the cutoff for positivity (70 AU/mL). (D) Time between the last rituximab infusion and anti-RBD response after the third vaccine dose. AU=arbitrary units. RBD=receptor-binding domain.

Table 3.

Baseline factors according to response to two vaccine doses in patients

| No response*(n=54) | Weak response*(n=14) | Response*(n=19) | p value† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| ≤30 years | 2 (4%) | 0 | 1 (5%) | 0·10 | |

| 31–65 years | 30 (56%) | 12 (86%) | 15 (79%) | .. | |

| >65 years | 22 (41%) | 2 (14%) | 3 (16%) | .. | |

| Body-mass index, kg/m2 | 25 (22–28) | 26 (24–28) | 27 (23–31) | 0·47 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 45 (83%) | 9 (64%) | 15 (79%) | 0·26 | |

| Male | 9 (17%) | 5 (36%) | 4 (21%) | .. | |

| Current smoker | 6 (11%) | 1 (7%) | 4 (21%) | 0·47 | |

| Co-medication with DMARDs‡ | 34 (63%) | 10 (71%) | 12 (63%) | 0·90 | |

| Number of previous DMARDs | 4 (2–6) | 5 (3–7) | 5 (3–7) | 0·62 | |

| Number of rituximab infusions | 11 (4–16) | 5 (2–14) | 9 (6–13) | 0·44 | |

| CD19+ B cell count§, cells per μL | 6·5 (17·3) | 48·5 (95·2) | 121·0 (103·3) | <0·0001 | |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, mm/h | 11·2 (7·5) | 8·3 (6·2) | 15·1 (14·7) | 0·45 | |

| C-reactive protein concentration, mg/L | 4·2 (5·9) | 2·2 (1·7) | 4·2 (4·0) | 0·33 | |

| DAS28 | 2·3 (0·9) | 2·1 (1·1) | 2·9 (1·5) | 0·13 | |

| Time between rituximab and first vaccine dose, days | 107 (80–152) | 137 (61–233) | 267 (222–324) | <0·0001 | |

| Vaccines | |||||

| SARS-CoV-2 infection plus BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273 | 0 | 2 (14%) | 1 (5%) | 0·016 | |

| Two doses of BNT162b2 | 44 (81%) | 9 (64%) | 10 (53%) | .. | |

| Two doses of mRNA-1273 | 10 (19%) | 3 (21%) | 8 (42%) | .. | |

Data are n/N (%), n (%), median (IQR), or mean (SD). AU=arbitrary units. DAS28=disease activity score in 28 joints. DMARDs=disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. RBD=receptor-binding domain.

Anti-RBD antibody concentrations of less than 5 AU/mL defined no response, of 5–69 AU/mL defined weak response, and of 70 AU/mL or more defined response.

p values correspond to comparisons of categories across response groups using Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous variables and Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables.

Includes methotrexate, leflunomide, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine.

Five patients received rituximab between having their second dose and donating blood for CD19+ B cell count measurement and are not included here.

49 patients (median age 62 years [IQR 56–67]; 43 [87·8%] women and six [12·2%] men) with insufficent serological responses (<100 AU/mL) to two doses were allotted a third vaccine dose at a median of 70 days (IQR 49–104) after the second vaccine dose. In these patients, median anti-RBD antibody concentrations were 2 AU/mL (IQR 2–3) after the second dose and 3 AU/mL (2–18) after the third dose (figure 1A, C). Comparison between anti-RBD antibody concentrations in samples after the second dose and samples after the third dose showed a median change of 0·96 AU/mL (IQR 0·05–27·38; p<0·0001). Eight (16·3%) of 49 patients had a serological response after the third dose, with a median interval between the last rituximab infusion and the third dose of 250 days (IQR 206–265; table 2; figure 1C, D; appendix p 7). Two patients who had initially received one vaccine dose because they had a history of previous COVID-19, and later received their second dose with inclusion in this group, did not develop a serological response. No significant associations between the investigated factors and serological response after the third dose were found in a multivariable regression analysis (appendix p 8), possibly due to the low number of patients with a response (n=8).

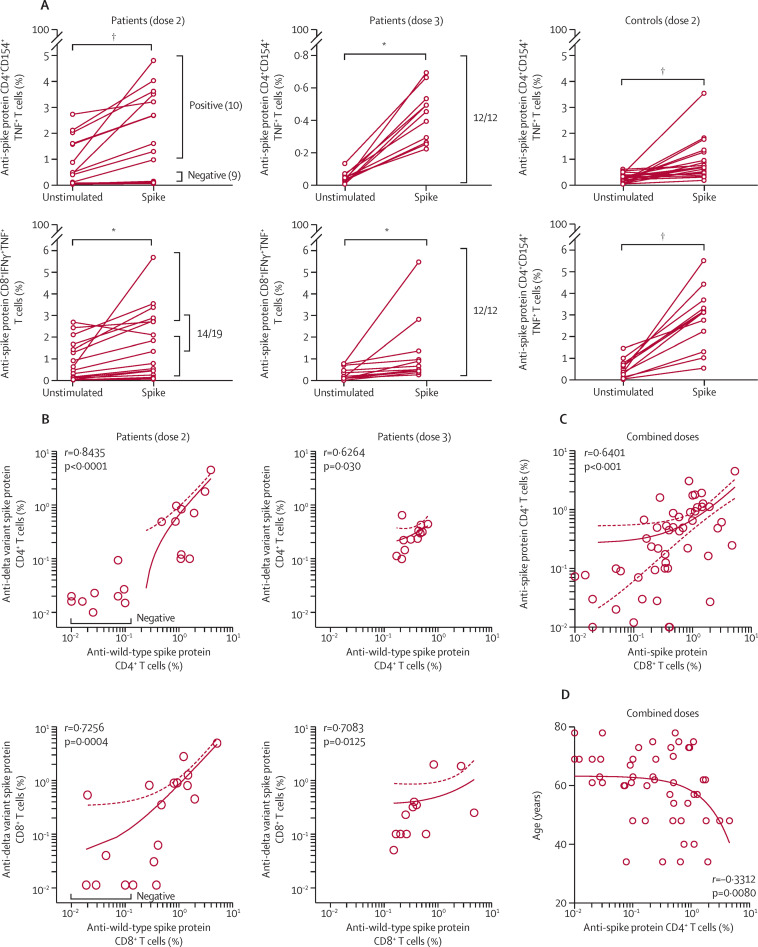

T-cell responses were analysed in 19 of 20 invited patients after the second vaccine dose. 12 of these 19 patients were allotted a third vaccine dose and provided blood samples for T-cell response assessment after the third dose. After two doses, 10 (53%) of 19 patients had SARS-CoV-2 wild-type-specific CD4+ T-cell responses and 14 (74%) had SARS-CoV-2 wild-type-specific CD8+ T-cell responses (figure 2A ; appendix p 6). The patients without anti-spike protein CD8+ T-cell responses (five [26%]) also did not have detectable anti-spike protein CD4+ T cells. Time since the last rituximab infusion was not correlated with T-cell response (data not shown). T-cell responses were detected in all vaccinated healthy donors (n=20) after their second vaccine dose, with response magnitudes similar to those seen in patients (figure 2A). The reduced T-cell responsiveness to the vaccine in patients versus controls could not directly be explained by the regimen of immunosuppressive drugs (rituximab monotherapy or rituximab combined with conventional synthetic DMARDs) because the activation induced by polyclonal stimulation of the T-cell receptor (with Cytostim) was similar between patients and controls, indicating normal functional responses (data not shown). After the third dose, all 12 patients had detectable anti-wild-type spike protein CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses, including five patients who did not have T-cell responses after the second dose (figure 2A).

Figure 2.

T-cell responses after two and three vaccine doses

(A) Anti-wild-type spike protein-specific T-cell responses in patients after two and three doses and in healthy controls after two doses. CD4+ T-cell responses and CD8+ T-cell responses are shown for all unstimulated and stimulated pairs. The p values from Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank tests are shown, with * indicating p<0·001 and †indicating p<0·0001. Patients with a response (positive) and patients without a response (negative) are indicated. (B) Analysis of T-cell responses directed against wild-type and delta variant SARS-CoV-2 spike peptides in patients after two and three doses (Spearman correlation). Solid lines show simple linear regression of correlation and dotted lines represent 95% CIs. (C) Percentage of anti-spike protein CD4+ T cells versus anti-spike protein CD8+ T cells in patient responders to wild-type and delta variant spike peptides using combined data of the second and third doses. Spearman correlation is shown. (D) Percentage of anti-spike protein CD4+ T cells versus age in patient responders to wild-type and delta variant spike peptides using combined data of the second and third doses. Spearman correlation is shown. See the appendix (p 5) for supplementary data for gating and controls.

To evaluate the potential of vaccines to induce a cross-protection against currently circulating viral strains, we extended the T-cell analysis, challenging peripheral blood mononuclear cells from vaccinated patients with spike peptides derived from the SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2). The magnitude of T-cell responses to the delta variant spike protein correlated with the magnitude of responses towards wild-type spike protein for both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses after the second and third dose (figure 2B). Combined anti-spike protein T-cell responses directed against wild-type and delta SARS-CoV-2 spike peptides are shown in figure 2C. The positive correlation between CD4+ T-cell responses and CD8+ T-cell responses (Spearman r=0·6401; p<0·001) suggested that the vaccine elicited concerted T-cell immunity. Patient age negatively correlated with the number of anti-spike protein CD4+ T cells (figure 2D).

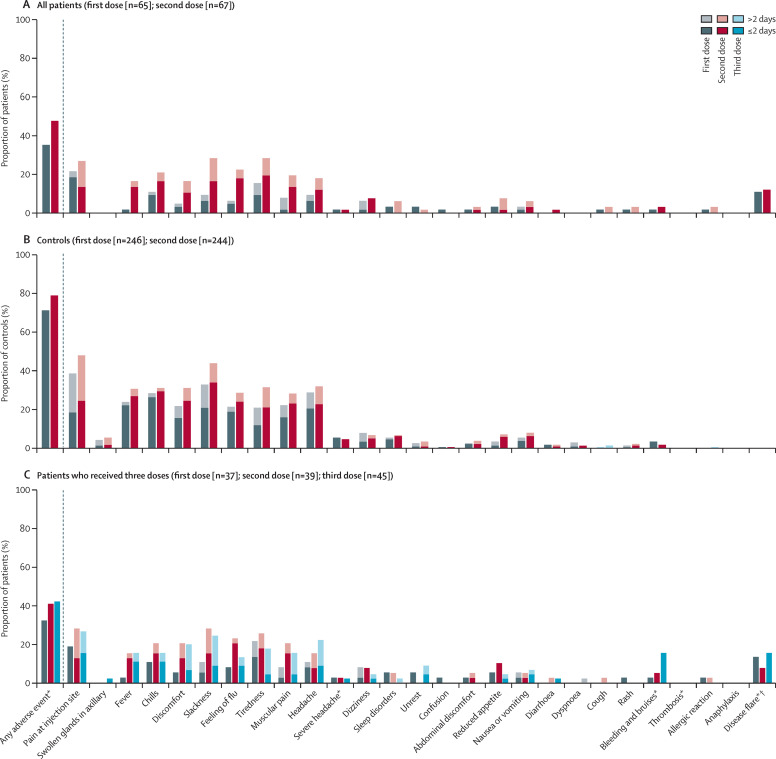

After two doses, adverse events were reported in 32 (48%) of 67 patients and in 191 (78%) of 244 healthy controls (figure 3 ; appendix p 9). 19 (42%) of 45 patients receiving a third dose reported an adverse event (figure 3; appendix p 9). For patients who received a third dose, the numbers of adverse events were similar after the second dose and after the third dose, with the exception of bleeding and bruises, which were more frequently reported after the third dose (seven [16%] of 45 patients) than after the second dose (two [5%] of 39 patients; appendix p 9). Among patients who received a third dose, five (14%) of 37, three (8%) of 39, and seven (16%) of 45 reported disease flares after the first, second, or third doses, respectively (appendix p 9). No serious adverse events were reported and there were no deaths during the study period.

Figure 3.

Adverse events following two or three vaccine doses in patients and controls

(A) All patients. (B) Controls. (C) Patients who received three vaccine doses. Adverse events were reported for all patients and a subset (n=246) of healthy controls (health-care workers at Diakonhjemmet Hospital and Akershus University Hospital, Oslo, Norway). *Duration not measured. †No patients were hospitalised due to disease flares after vaccination.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this large observational study is the first to report on the immunogenicity and safety of two and three doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in rituximab-treated patients with rheumatoid arthritis. After two doses, only 21·8% of patients, compared with 98·4% of healthy controls, developed a humoral response. We found that, despite these severely attenuated humoral responses and the absence of CD19+ B cells, CD8+ T-cell responses were present in 74% of rituximab-treated patients after two doses and in all patients after three doses. T-cell responses to wild-type spike peptides correlated with those seen towards the delta variant spike peptides, showing that the vaccine also elicited immunity to this variant. Both the standard two-dose regimen and the third dose were safe in terms of patient-reported adverse events. To date, this study is the largest to combine sensitive measurements of humoral and cellular immunity with a description of adverse events after two doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with rituximab.

Previous studies have shown a positive correlation between the concentrations of neutralising antibodies and protection from symptomatic COVID-19.23, 24 However, serological responses decay with time after vaccination.25 By contrast, SARS-CoV T-cell memory is long-lasting and was found 17 years post-infection.26 A study in rhesus macaques showed that SARS-CoV-2-specific T-cell immune responses contributed to protection when antibody responses were low,12 bridging insufficient humoral immunity. CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells counteract viral infections by producing effector cytokines, such as IFNγ and TNF, and by exerting cytotoxic activity against virus-infected cells. Early and robust SARS-CoV-2-specific T-cell responses were associated with lower severity of COVID-19 in otherwise healthy patients.13 Robust CD8+ T-cell responses were also associated with improved survival in patients with COVID-19 and haematological malignancies, including patients on anti-CD20 therapies,14 underlining the importance of T-cell immunity in patients with impaired B cells.

We found that 53% of patients had CD4+ T-cell responses and 74% had CD8+ T-cell responses after two vaccine doses. These findings are in line with a study of rituximab-treated patients with various rheumatic diseases (IgG4-related disease, connective tissue diseases, vasculitis, and rheumatoid arthritis), which found that 26 (58%) of 45 patients had detectable IFNγ-secreting SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells and 14 (54%) of 26 did not have a serological response;9 however, this study did not discriminate between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. In our study, fewer patients had CD4+ T-cell responses, which are required for optimal B-cell responses, than CD8+ T-cell responses after two vaccine doses.

In patients with insufficient serological responses to two vaccine doses, we found that only a few patients mounted a serological response after a third dose. By contrast, the third dose induced anti-spike protein CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in all patients tested, regardless of humoral responses. The coordinated development of helper and cytotoxic T-cell responses might constitute protective immunity against future infections by SARS-CoV-2 and its variants. Our results suggest that the third dose enables robust T-cell immunity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with rituximab, potentially improving protection in this patient group.

Our multivariable analyses show that the time since last rituximab infusion was significantly associated with serological response to two SARS-CoV-2 vaccine doses, with responders having a median interval of about 9 months between their last rituximab infusion and their first vaccine dose. This finding supports those found in a study by Furer and colleagues10 and observational data11 from smaller cohorts showing that the seroconversion rate in patients treated with rituximab increased from 20% to 50% when the interval between rituximab and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination increased from 6 months to 12 months. CD19+ cell count was also associated with serological response to two doses in univariable logistic regression analyses. This result indicates that CD19+ cell counts could be used as a surrogate measure for B-cell function when timing vaccinations. Vaccination with mRNA-1273, as compared with BNT162b2, was significantly associated with serological response to two vaccine doses. This finding is in line with previous findings of higher humoral immunogenicity to mRNA-1273 compared with BNT162b2 in healthy participants.27

Both two and three vaccine doses were safe with respect to patient-reported adverse events, with no serious adverse events being reported. Numerically, patients reported fewer adverse events than healthy controls. This result could be due to the younger age of healthy controls compared with patients,1, 2 although we cannot rule out an association between adverse events and humoral response in which immunosuppressive medication reduces side-effects from, and the immunogenicity of, SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. More patients reported bleeding and bruises after the third dose than after the second dose, but the sample size was small and the current results on adverse events should be interpreted with caution.

The strengths of this study include: the broad inclusion criteria, with all rituximab-treated patients receiving a personal invitation, which increase the generalisability of our findings; close follow-up, including an assessment of adverse events; and the broad assessment of vaccine response—both humoral and cellular—to two and three vaccine doses.

This study also has some limitations. First, the patients were older (median 60 years) than the healthy controls (median 43 years), which might interfere with the comparability of results. The difference in serological response, however, was greater than what can be explained by age alone,28, 29 and we adjusted for age in the analyses. Second, the number of included patients was too low to draw definite conclusions regarding safety, but our data on the safety of three vaccine doses in immunocompromised patients with insufficient responses to two doses are reassuring. Third, for feasibility reasons, only 12 patients had T-cell assessments after the third dose. However, patients chosen for T-cell analyses were randomly selected before the first dose, and our findings were consistent across all patients tested. Finally, only patients were offered a third dose; hence, patient response after a third dose could not be compared with healthy controls.

Rituximab-treated patients with rheumatoid arthritis are at risk of severe COVID-19,4, 7 and are in particular need of protection by vaccination. In terms of serological responses, our data suggest that a prolonged interval between the last rituximab infusion and vaccination (>9 months) could be beneficial. Most rituximab-treated patients did not have serological responses to two or three vaccine doses, but did have T-cell responses and few adverse events upon receiving a third dose. Further studies are needed to assess the clinical protection provided by a cellular response in the absence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, but our results raise the possibility that patients on regular rituximab infusions might rely on cellular immunity alone. This study supports the provision of three-dose vaccination to patients with rituximab-treated rheumatoid arthritis to help protect this clinically vulnerable group from COVID-19, informing patients, health-care providers, and decision makers on the optimal vaccination strategy.

Data sharing

A deidentified patient dataset and the protocol can be made available to researchers upon reasonable request after we have published all data on our predefined research objectives. The data will only be made available after submission of a project plan outlining the reason for the request and any proposed analyses, and will have to be approved by the Nor-vaC steering group. Project proposals can be submitted to the corresponding author (ingrid.jyssum@gmail.com). Data sharing will have to follow appropriate regulations.

Declaration of interests

KKJ reports speakers bureaus from Roche and BMS and advisory board participation for Celltrion and Norgine. JJ reports grants from Abbvie, Pharmacosmos, and Ferring; consulting fees from Abbvie, Boerhinger Ingelheim, BMS, Celltrion, Ferring, Glihead, Janssen Cilag, MSD, Napp Pharma, Novartis, Orion Pharma, Pfeizer, Pharmacosmos, Takeda, Sandoz, and Unimedic Pharma; and speakers bureaus from Abbvie, Astro Pharma, Boerhinger Ingelheim, BMS, Celltrion, Ferring, Glihead, Hikma, Janssen Cilag, Meda, MSD, Napp Pharma, Novartis, Oriuon Pharma, Pfeizer, Pharmacosmos, Roche, Takeda, and Sandoz. TKK reports grants from AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB; consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Mylan, Novartis, Pfizer, Sandoz, and Sanofi; speakers bureaus from Amgen, Celltrion, Egis, Evapharma, Ewopharma, Hikma, Oktal, Sandoz, and Sanofi; and participation on a data safety monitoring board for AbbVie. LAM reports funding from the KG Jebsen foundation; support for infrastructure and biobanking from the University of Oslo and Oslo University Hospital; grants from the Coalition of Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI); and speakers bureaus from Novartis and Cellgene. GG reports consulting fees from the Norwegian System of Compensation to Patients and AstraZeneca, and speakers bureaus from Bayer, Sanofi Pasteur, and Thermo Fisher. JTV reports grant from the CEPI. FL-J reports grants from the CEPI and the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority. GLG reports funding from the Karin Fossum foundation, Diakonhjemmet Hospital, Oslo University Hospital, Akershus University Hospital, the Dr Trygve Gydtfeldt og frues Foundation, and the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority; consulting fees from AbbVie and Pfizer; speakers fees from AbbVie, Pfizer, Sandoz, Orion Pharma, Novartis, and UCB; and advisory board participation for Pfizer and AbbVie. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Nor-vaC was an investigator-initiated study with no initial funding. We later received funding from the CEPI, Research Council of Norway Covid (number 312693), the KG Jebsen Foundation (grant 19), Oslo University Hospital, the University of Oslo, the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority, Dr Trygve Gythfeldt og frues forskningsfond, the Karin Fossum Foundation, and the Research Foundation at Diakonhjemmet Hospital. We thank the patients participating in our study; we are very grateful for the time and effort they have invested in the project. We thank the patient representative in the study group, Kristin Isabella Espe. We acknowledge Ingrid Egner and Katrine Persgård Lund for organising the cellular biobank, and personnel at the Department of Immunology, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway, for collection of control samples at Oslo University Hospital. We thank Amin Alirezaylavasani, Julie Røkke Osen, and Victoriia Chaban for their technical assistance. We thank all study personnel involved at the Division of Rheumatology and Research at Diakonhjemmet Hospital, Oslo, Norway, especially Kjetil Bergsmark, Ruth Hilde Laursen, and May-Britt Solem.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final submitted version, and take responsibility for the completeness and accuracy of the data and analyses. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. IJ, HK, GLG, SWS, ATT, FL-J, LAM, and JS accessed and verified the underlying data. IJ, GLG, SWS, KKJ, FL-J, LAM, and JTV conceived and designed the study. GLG, SWS, KKJ, FL-J, LAM, ATT, SAP, and IJ oversaw the implementation of the study. GLG, SWS, SAP, KKJ, ATT, and IJ collected the data. IJ, HK, GLG, SWS, FL-J, LAM, JS, ATT, and SAP interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. FL-J developed the assay used for serological assessment. FL-J, EBV, and TTT did the serological analysis. HK, SM, and LAM did the T-cell analysis. JS was the study statistician. ATT, DJW, TKK, EAH, SM, GG, GBK, and JJ contributed to study conception and design. L-SHN-M and AMA contributed to data collection.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman MA, Curtis JR, Winthrop KL. Impact of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs on vaccine immunogenicity in patients with inflammatory rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:1255–1265. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avouac J, Drumez E, Hachulla E, et al. COVID-19 outcomes in patients with inflammatory rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases treated with rituximab: a cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3:e419–e426. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00059-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagni F, Simon D, Tascilar K, et al. COVID-19 and immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: effect of disease and treatment on COVID-19 outcomes and vaccine responses. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3:e724–e736. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00247-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raiker R, DeYoung C, Pakhchanian H, et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a multicenter research network study in the United States. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021;51:1057–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2021.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersen KM, Bates BA, Rashidi ES, et al. Long-term use of immunosuppressive medicines and in-hospital COVID-19 outcomes: a retrospective cohort study using data from the National COVID Cohort Collaborative. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00325-8. published online Nov 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jena A, Mishra S, Deepak P, et al. Response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in immune mediated inflammatory diseases: systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2021.102927. published online Aug 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mrak D, Tobudic S, Koblischke M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in rituximab-treated patients: B cells promote humoral immune responses in the presence of T-cell-mediated immunity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:1345–1350. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furer V, Eviatar T, Zisman D, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in adult patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases and in the general population: a multicentre study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:1330–1338. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moor MB, Suter-Riniker F, Horn MP, et al. Humoral and cellular responses to mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with a history of CD20 B-cell-depleting therapy (RituxiVac): an investigator-initiated, single-centre, open-label study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3:e789–e797. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00251-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMahan K, Yu J, Mercado NB, et al. Correlates of protection against SARS-CoV-2 in rhesus macaques. Nature. 2021;590:630–634. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03041-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rydyznski Moderbacher C, Ramirez SI, Dan JM, et al. Antigen-specific adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in acute COVID-19 and associations with age and disease severity. Cell. 2020;183:996–1012.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bange EM, Han NA, Wileyto P, et al. CD8+ T cells contribute to survival in patients with COVID-19 and hematologic cancer. Nat Med. 2021;27:1280–1289. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01386-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonelli MM, Mrak D, Perkmann T, Haslacher H, Aletaha D. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in rituximab-treated patients: evidence for impaired humoral but inducible cellular immune response. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:1355–1356. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexander JL, Selinger CP, Powell N. Third doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in immunosuppressed patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:987–988. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00374-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bar-On YM, Goldberg Y, Mandel M, et al. Protection of BNT162b2 vaccine booster against Covid-19 in Israel. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1393–1400. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2114255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felten R, Gallais F, Schleiss C, et al. Cellular and humoral immunity after the third dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in patients treated with rituximab. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00351-9. published online Nov 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norwegian Institute of Public Health Norwegian Immunisation Registry SYSVAK. https://www.fhi.no/en/hn/health-registries/norwegian-immunisation-registry-sysvak/

- 20.Norwegian Institute of Public Health Norwegian Surveillance System for Communicable Diseases (MSIS) https://www.fhi.no/en/hn/health-registries/msis/

- 21.Holter JC, Pischke SE, de Boer E, et al. Systemic complement activation is associated with respiratory failure in COVID-19 hospitalized patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:25018–25025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010540117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.König M, Lorentzen ÅR, Torgauten HM, et al. Humoral immunity to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in multiple sclerosis: the relevance of time since last rituximab infusion and first experience from sporadic revaccinations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2021-327612. published online Oct 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27:1205–1211. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergwerk M, Gonen T, Lustig Y, et al. Covid-19 breakthrough infections in vaccinated health care workers. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1474–1484. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2109072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chia WN, Zhu F, Ong SWX, et al. Dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibody responses and duration of immunity: a longitudinal study. Lancet Microbe. 2021;2:e240–e249. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00025-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Bert N, Tan AT, Kunasegaran K, et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell immunity in cases of COVID-19 and SARS, and uninfected controls. Nature. 2020;584:457–462. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2550-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steensels D, Pierlet N, Penders J, Mesotten D, Heylen L. Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 antibody response following vaccination with BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273. JAMA. 2021;326:1533–1535. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.15125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collier DA, Ferreira IATM, Kotagiri P, et al. Age-related immune response heterogeneity to SARS-CoV-2 vaccine BNT162b2. Nature. 2021;596:417–422. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03739-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richards NE, Keshavarz B, Workman LJ, Nelson MR, Platts-Mills TAE, Wilson JM. Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 antibody response by age among recipients of the BNT162b2 vs the mRNA-1273 vaccine. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.24331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

A deidentified patient dataset and the protocol can be made available to researchers upon reasonable request after we have published all data on our predefined research objectives. The data will only be made available after submission of a project plan outlining the reason for the request and any proposed analyses, and will have to be approved by the Nor-vaC steering group. Project proposals can be submitted to the corresponding author (ingrid.jyssum@gmail.com). Data sharing will have to follow appropriate regulations.