Abstract

Background:

Cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD) is a common neurological disease under the effect of multiple factors. Although some literature analyzes and summarizes the risk factors of CSVD, the conclusions are controversial. To determine the risk factors of CSVD, we conducted this meta-analysis.

Methods:

Five authoritative databases of PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, CNKI, and Wan Fang were searched to find related studies published before November 30, 2020. The literature was screened according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We used RevMan 5.4 software to analyze the data after extraction.

Results:

A total of 29 studies involving 16,587 participants were included. The meta-analysis showed that hypertension (odds ratio [OR] 3.16, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.22-4.49), diabetes (OR 2.15, 95% CI 1.59-2.90), hyperlipidemia (OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.11-2.40), smoking (OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.15-1.89) were significantly related to the risk of lacune, while drinking (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.87-1.23) was not. And hypertension (OR 3.31, 95% CI 2.65-4.14), diabetes (OR 1.66, 95% CI 2.65-1.84), hyperlipidemia (OR 1.88, 95% CI 1.08-3.25), smoking (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.07-2.04) were significantly related to the risk of white matter hyperintensity, while drinking (OR 1.41, 95% CI 0.97-2.05) was not.

Conclusions:

This study suggested that hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking are risk factors of CSVD, and we should take measures to control these risk factors for the purpose of preventing CSVD.

Keywords: cerebral small vessel diseases, lacune, meta-analysis, risk factors, white matter hyperintensity

1. Introduction

Cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD) refers to a series of clinical, imaging, and pathological syndromes resulting from various causes affecting the perforating arterioles, arterioles, capillaries, venules, and venules in the brain.[1] CSVD, which causes about 25% of ischemic strokes and most hemorrhagic strokes, is the most common cause of vascular dementia. And it is usually associated with Alzheimer disease and exacerbates the resulting cognitive impairment, leading to about 50% of dementias worldwide.[2] In China, lacunar infarction caused by cerebral microvascular disease accounts for 25% to 50% of ischemic stroke, which is higher than that in western countries.[3] The prevalence of white matter hyperintensity (WMH) ranges from 50% to 95% between 45 and 80 years old. Cognitive impairment caused by CSVD can account for 36% to 67% of vascular dementia.[4] It can be predicted that CSVD will be a major disease that will affect the quality of life of the elderly in the future.

In the early stage of CSVD, there can be no symptoms, only imaging changes,[5] which makes the diagnosis and treatment not so timely. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most common and accurate method to detect subtle changes in the brain of patients with CSVD. The imaging standards of CSVD were established in 2013 and widely recognized as WMH, lacune, recent subcortical small infarction, perivascular space, cerebral microbleed, and brain atrophy, with WMH and lacunar being the most common. WMH is manifested on MRI as extensive or fused abnormal signal, which is particularly evident in T2-weighted image and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences, presenting as high signal. Lacune appears as round or ovoid subcortical fluid-filled (signal similar to cerebrospinal fluid) cavities on MRI and are most typical on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences, appearing as a central low signal with a ring of high signal at the edges. This study will analyze from these 2 aspects. Although some progress has been made, it is clear that our understanding of CSVD is not enough. At present, the treatment is mainly to control hypertension, symptomatic treatment, and cognitive dysfunction treatment.[6] But we all know that the best response should be to prevent CSVD from occurring, so it is important to identify the risk factors of CSVD. There are a number of studies on risk factors for CSVD, but they are often limited to a particular region or hospital, and the number of subjects included is not large enough, sometimes leading to opposite conclusions.[7] Therefore, we conducted a review and meta-analysis of the existing literature aiming to more accurately identify risk factors for CSVD and provide evidence for the prevention of CSVD.

2. Methods

This study was designed and completed under the guidance of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses statement. Since this is a meta-analysis of previous studies, no ethical approval is required.

2.1. Search strategy

We conducted a search of the following databases: PubMed, Cochrane library, Embase, CNKI, and Wan Fang. Databases were searched from the earliest data to 30 November 2020 with the search terms: “Cerebral Small Vessel Diseases”, “Recent small subcortical infarct”, “Lacune”, “White matter hyperintensity”, “Perivascular space”, “Cerebral microbleed”, “Brain atrophy”, “Risk factor∗”, “Case control” and their entry term.

2.2. Selection criteria

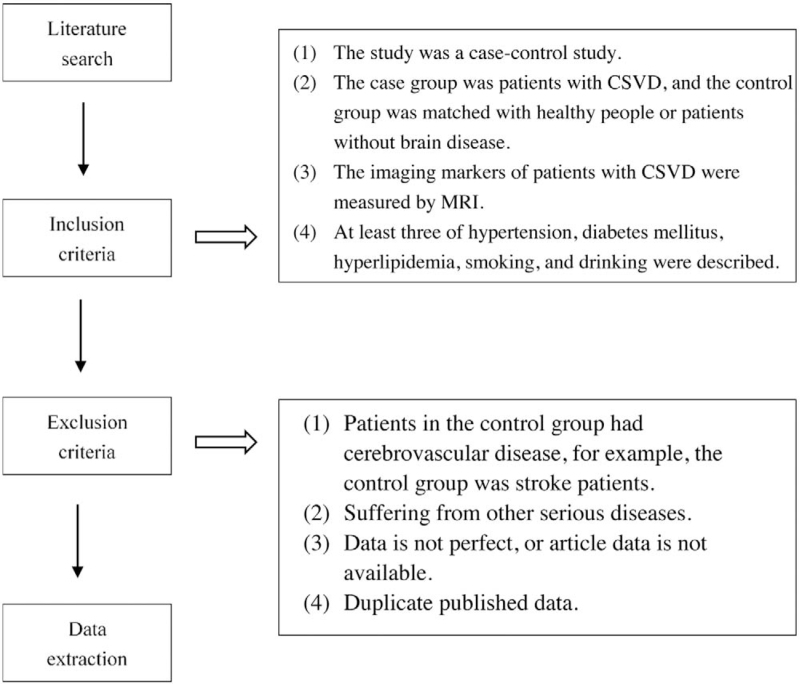

Inclusion criteria:

The study was a case-control study.

The case group was patients with CSVD, and the control group was matched with healthy people or patients without brain disease.

The imaging markers of patients with CSVD were measured by MRI.

At least 3 of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, smoking, and drinking were described.

Exclusion criteria:

Patients in the control group had cerebrovascular disease, for example, the control group was stroke patients.

Suffering from other serious diseases.

Data is not perfect, or article data is not available.

Duplicate published data.

2.3. Study selection

We import the documents retrieved from the 5 databases according to the search strategy into Endnote. First of all, use the software to remove the repeated literature, then browse the title and abstract, exclude the irrelevant literature, and finally read the full text, according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria to eliminate the literature that does not meet the requirements. The work above is done independently and blindly by the 2 researchers. If any disagreement arises, it will be resolved through mutual consultation. When consensus could not be reached, consult a third expert. The literature screening and data extraction protocol is shown in Figure 1

Figure 1.

The process of literature screening and data extraction.

2.4. Data extraction and assessment of the risk of bias

From the included studies, the name of the first author, the year of publication, the total sample size, and the number of cases and controls were extracted. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to evaluate the quality of the included literature, which was divided into a total of 8 items, with the highest score of 2 given to the item of comparability and the highest score of 1 given to the others, for a total score of 9. A score of 0 to 3 was assigned to low-quality literature, 4 to 6 to moderate-quality literature, and 7 to 9 to high-quality literature. The evaluation of literature quality was performed by 2 researchers independently and blinded to each other. If 2 evaluators gave different scores, they need to discuss and negotiate the solution, and if necessary, they could consult a third party.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Extracted data were analyzed using RevMan 5.4 (https://training.cochrane.org/) for meta-analysis, and the count data were expressed using the odds ratio (OR) and their 95% confidence interval (CI). Heterogeneity of all included studies was assessed and quantified using the Cochrane Q statistic and the I2 statistic, respectively. When I2 ≥ 50, the heterogeneity is significant, and the random effect model is used for analysis. The fixed effect model is used for analysis when I2 < 50%, which means the heterogeneity is not significant. Publication bias for the studies in the text was assessed using visual funnel plots. If the funnel chart is symmetrically distributed, there is no publication bias, if on the contrary, it indicates that there is publication bias. The sensitivity analysis was carried out by eliminating the study one by one, which was used to determine the stability and reliability of the conclusions.

3. Results

3.1. Literature retrieval results and basic characteristics

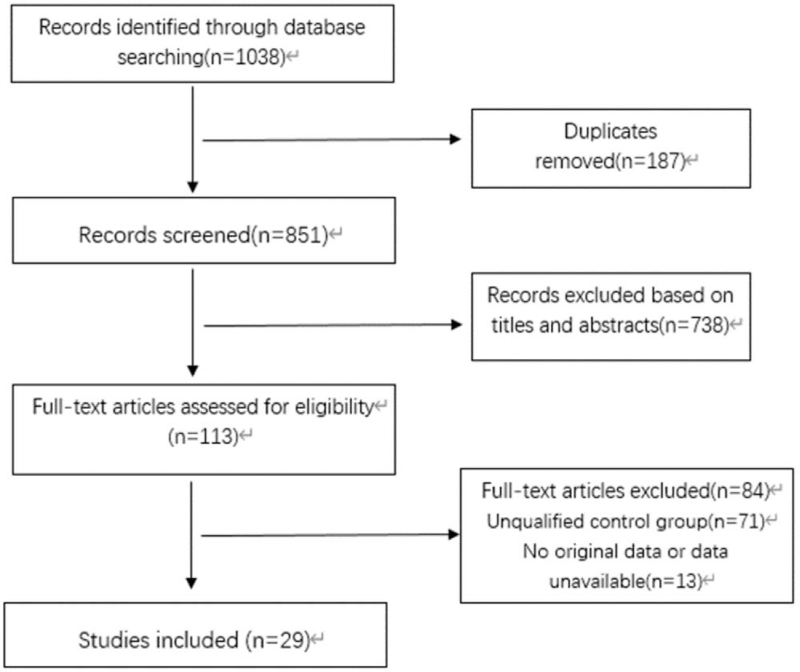

After the literature search process, 1652 potentially eligible articles were initially identified. After eliminating 187 duplicates, the titles and abstracts of the remaining 1465 studies were browsed, and 1352 irrelevant studies were removed. Finally, the full text was read, and the literatures that did not meet the requirements were excluded according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 29 literatures that met the criteria were obtained. The screening process is shown in Figure 2. We divided the included literatures into lacune group, control group and WMH group, control group. There were 12 articles related to lacune, a total of 6944 people, and 17 articles related to WMH, a total of 9643 people. The basic characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1, and the research factors are divided into hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, smoking, drinking 5 aspects, with the number of events as the outcome index.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of the systematic search process.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all included studies in our meta-analysis.

| Hypertension | Diabetes | Hyperlipidemia | Smoking | Drinking | |||

| First author, year | Group (number) | Yes/no | Yes/no | Yes/no | Yes/no | Yes/no | Mean age |

| Chen Liang 2018 | Lacune (n = 406) | 258/148 | 131/275 | 122/284 | 129/277 | 52/354 | N |

| Control (n = 452) | 196/256 | 52/400 | 119/333 | 114/338 | 45/407 | ||

| Christian Kukla 1998 | Lacune (n = 61) | 32/29 | 8/53 | N | 18/43 | N | ≥65 |

| Control (n = 57) | 15/42 | 7/50 | N | 11/46 | N | ||

| Fei Li 2019 | Lacune (n = 702) | 433/269 | 281/421 | N | 149/553 | 148/554 | <65 |

| Control (n = 234) | 131/103 | 77/157 | N | 43/191 | 44/190 | ||

| Ki-Woong Nam 2018 | Lacune (n = 260) | 92/168 | 59/201 | 70/190 | 34/226 | 119/141 | <65 |

| Control (n = 2885) | 616/2269 | 377/2508 | 733/2152 | 452/2433 | 1406/1479 | ||

| Vasileios-Arsenios Lioutas 2017 | Lacune (n = 118) | 100/18 | 39/79 | N | 25/93 | N | ≥65 |

| Control (n = 354) | 219/135 | 35/319 | N | 35/319 | N | ||

| Y. Leira 2016 | Lacune (n = 62) | 33/29 | 15/47 | 26/36 | 28/34 | 15/47 | ≥65 |

| Control (n = 60) | 20/40 | 6/54 | 11/49 | 11/49 | 6/52 | ||

| Yoshitomo Notsu 1999 | Lacune (n = 147) | 108/39 | 16/131 | N | 57/90 | N | ≥65 |

| Control (n = 214) | 52/162 | 22/192 | N | 73/141 | N | ||

| Xin Cui 2011 | Lacune (n = 50) | 28/22 | 17/33 | N | 24/26 | N | <65 |

| Control (n = 42) | 10/32 | 4/38 | N | 16/26 | N | ||

| Zhijing Liang 2010 | Lacune (n = 65) | 55/10 | 29/36 | 18/47 | 20/45 | 16/49 | <65 |

| Control (n = 60) | 38/22 | 16/44 | 7/53 | 9/51 | 11/49 | ||

| Hongjin Wang 2003 | Lacune (n = 52) | 44/8 | 13/39 | N | 17/35 | N | <65 |

| Control (n = 30) | 8/22 | 6/24 | N | 4/26 | N | ||

| Huiyun Yu 2012 | Lacune (n = 106) | 75/31 | 36/70 | 42/64 | N | N | <65 |

| Control (n = 100) | 52/48 | 20/80 | 23/77 | N | N | ||

| Ke Deng 2007 | Lacune (n = 105) | 76/29 | 12/93 | N | 44/61 | 20/83 | <65 |

| Control (n = 322) | 119/203 | 19/303 | N | 129/193 | 81/241 | ||

| Haiqiang Jin 2020 | WMH (n = 240) | 77/163 | 13/227 | 63/177 | 48/192 | 56/184 | <65 |

| Control (n = 61) | 0/61 | 0/61 | 9/52 | 12/49 | 13/48 | ||

| Qing Lin 2017 | WMH (n = 2732) | 1505/1227 | 763/1969 | N | 847/1885 | 211/2521 | <65 |

| Control (n = 1951) | 607/1344 | 339/1612 | N | 398/1553 | 165/1786 | ||

| Xueying Yu 2018 | WMH (n = 379) | 245/134 | 39/340 | N | 90/289 | N | <65 |

| Control (n = 384) | 162/222 | 30/354 | N | 108/276 | N | ||

| B. Censori 2007 | WMH (n = 61) | 45/16 | 9/52 | 12/49 | 7/54 | N | ≥65 |

| Control (n = 117) | 52/65 | 13/104 | 21/96 | 29/88 | N | ||

| Dirk Sander 2000 | WMH (n = 82) | 48/34 | 10/72 | N | N | N | ≥65 |

| Control (n = 145) | 52/93 | 18/127 | N | N | N | ||

| Hongliang Feng 2017 | WMH (n = 193) | 155/38 | 43/150 | N | 13/180 | N | <65 |

| Control (n = 415) | 167/248 | 57/358 | N | 36/379 | N | ||

| Dinghua Zeng 2013 | WMH (n = 113) | 81/32 | 15/98 | N | 94/19 | N | ≥65 |

| Control (n = 28) | 15/13 | 2/26 | N | 4/24 | N | ||

| Xiujun Meng 2011 | WMH (n = 509) | 377/132 | 142/367 | N | 213/296 | 150/359 | ≥65 |

| Control (n = 509) | 301/208 | 126/383 | N | 176/333 | 119/390 | ||

| Fang Du 2019 | WMH (n = 65) | 50/15 | N | N | 19/46 | N | ≥65 |

| Control (n = 30) | 13/17 | N | N | 8/22 | N | ||

| Yinong Chen 2015 | WMH (n = 106) | 74/32 | 12/94 | N | 14/92 | N | ≥65 |

| Control (n = 31) | 7/24 | 3/28 | N | 5/26 | N | ||

| Hongli Yi 2008 | WMH (n = 158) | 89/69 | 43/115 | 76/82 | N | N | ≥65 |

| Control (n = 158) | 52/106 | 38/120 | 68/90 | N | N | ||

| Xinmin Huang 2005 | WMH (n = 144) | 113/31 | 53/91 | 86/58 | 79/65 | 48/96 | ≥65 |

| Control (n = 102) | 22/80 | 15/87 | 14/88 | 26/76 | 9/93 | ||

| Qinghua Li 2002 | WMH (n = 69) | 41/28 | 20/49 | 22/47 | 16/53 | N | ≥65 |

| Control (n = 69) | 25/44 | 13/56 | 17/52 | 14/55 | N | ||

| Ling Chen 2014 | WMH (n = 102) | 71/31 | 50/52 | 58/44 | 40/62 | 34/68 | ≥65 |

| Control (n = 61) | 25/36 | 18/43 | 24/37 | 8/53 | 15/46 | ||

| Liwei Sun 2016 | WMH (n = 241) | 130/111 | 50/191 | 119/122 | 41/200 | 35/206 | <65 |

| Control (n = 104) | 35/69 | 13/91 | 54/50 | 24/80 | 18/86 | ||

| Pan Tang 2014 | WMH (n = 36) | 27/9 | 11/25 | N | 25/11 | 23/13 | ≥65 |

| Control (n = 36) | 14/22 | 13/23 | N | 14/22 | 16/20 | ||

| Fei Wang 2001 | WMH (n = 106) | 59/47 | 28/78 | 36/70 | 41/65 | N | <65 |

| Control (n = 106) | 36/70 | 24/82 | 27/79 | 32/74 | N |

N = not available, WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

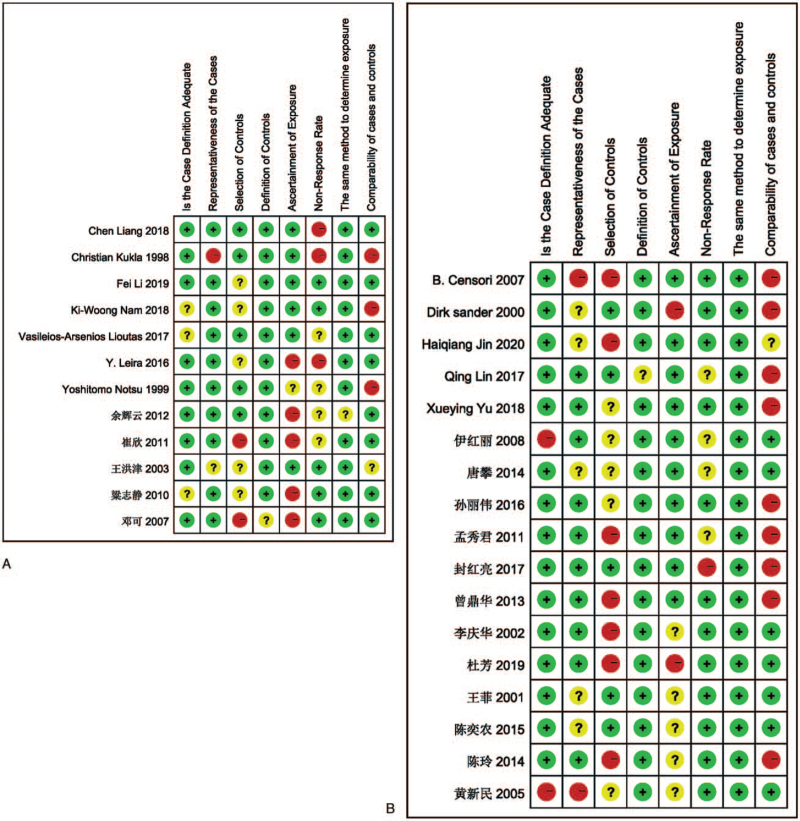

3.2. Quality assessment

The NOS scale is a commonly used scale for quality assessment of case-control studies, and its reliability and validity have been confirmed in long-term use. This meta-analysis also used the NOS scale for quality evaluation, and the green color in the figure indicates the score, and it can be seen that the included studies all scored above 5. The specific quality evaluation is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

(A) Quality evaluation about risk factors of the lacune. (B) Quality evaluation about risk factors of the WMH.

3.3. Risk factors

Effectiveness indicators were expressed as combined ORs with 95% CI, and forest plots were used to visually depict each test and the combined results with weights.

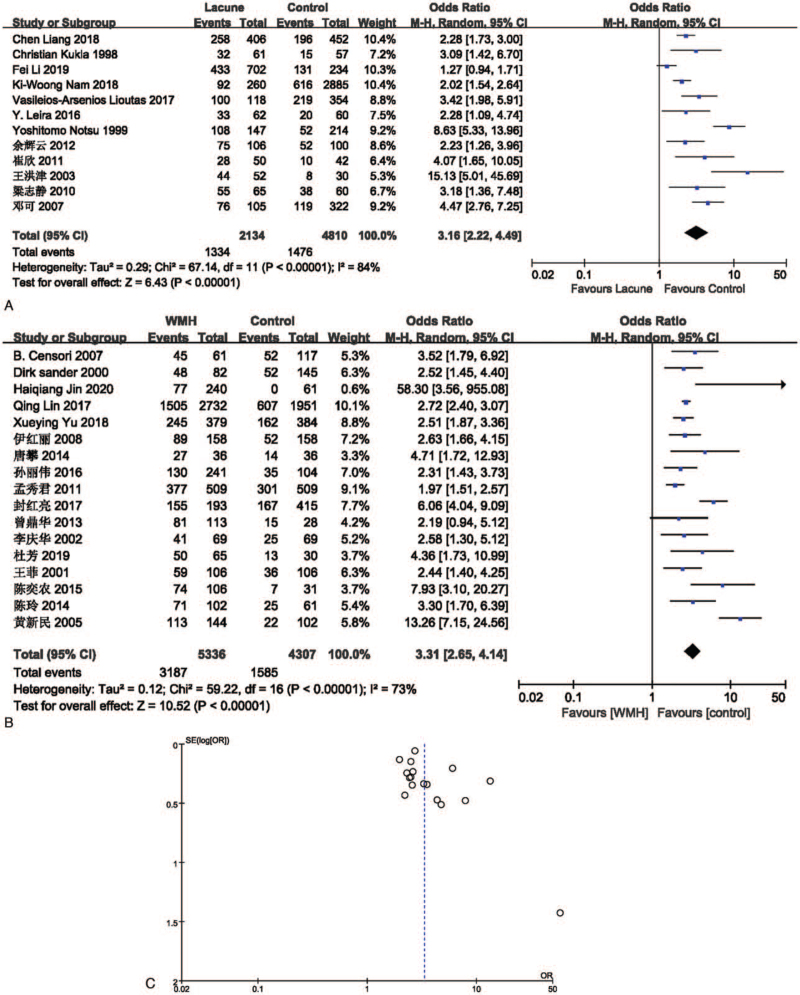

3.3.1. Hypertension

The effect of hypertension on lacune was analyzed in 12 studies involving 2134 in the lacune group and 4810 in the control group. The pooled results of these studies indicated that people with hypertension are more likely to get CSVD (OR = 3.16; 95% CI 2.22-4.49; P < .00001; I2 = 84%). The effect of hypertension on WMH was analyzed in 17 studies involving 5336 in the WMH group and 4307 in the control group. The pooled results of these studies indicated that people with hypertension are more likely to get CSVD (OR = 3.31; 95% CI 2.65-4.14; P < .00001; I2 = 73%). The funnel plot is roughly symmetrical, suggesting that publication bias may be small (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

(A) Forest plot showing the relationship between hypertension and lacune. (B) Forest plot showing the relationship between hypertension and WMH. (C) Funnel plot of hypertension on WMH. CI = confidence interval, WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

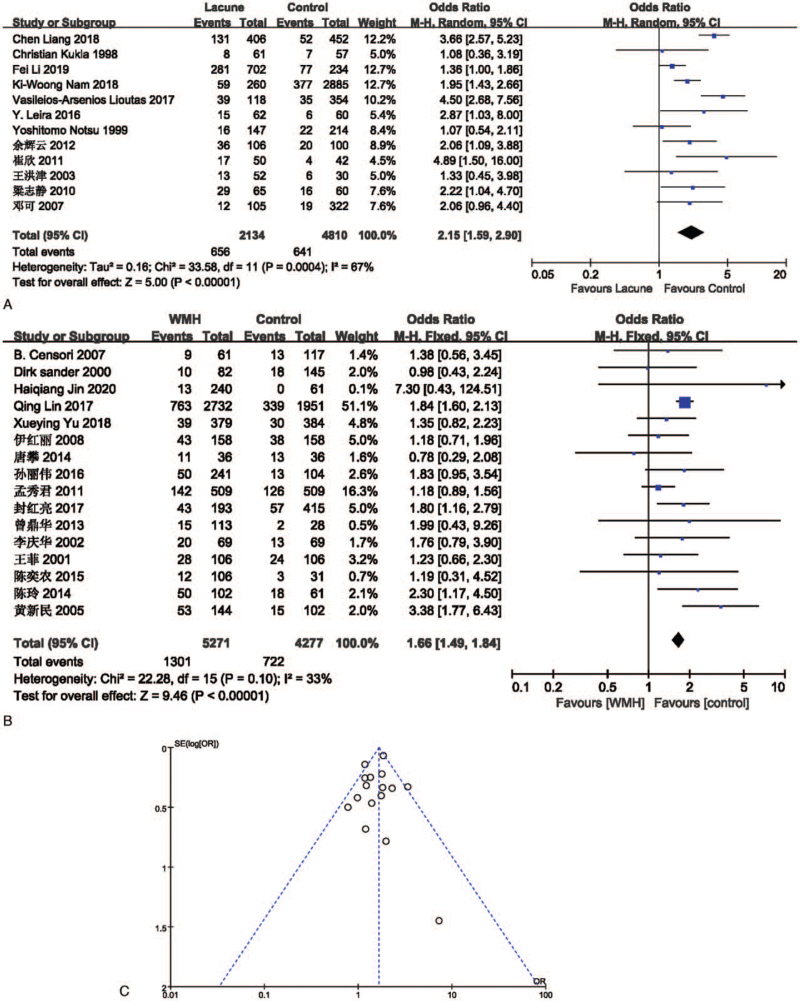

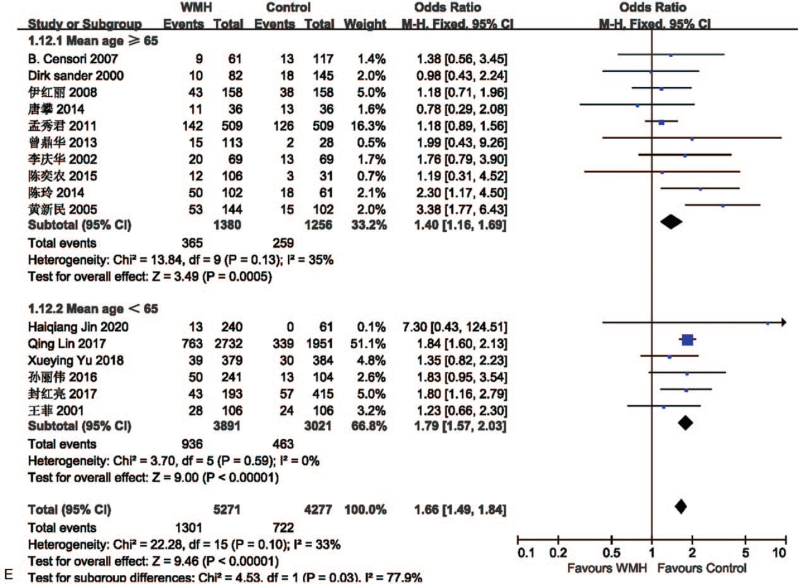

3.3.2. Diabetes

The effect of hypertension on lacune was analyzed in 12 studies involving 2134 in the lacune group and 4810 in the control group. The pooled results of these studies indicated that people with diabetes are more likely to get CSVD (OR = 2.15; 95% CI 1.59-2.90; P < .00001; I2 = 67%). The effect of diabetes on WMH was analyzed in 16 studies involving 5271 in the WMH group and 4277 in the control group. The pooled results of these studies indicated that people with diabetes are more likely to get CSVD (OR = 1.66; 95% CI 1.49-1.84; P < .00001; I2 = 33%). The funnel plot is roughly symmetrical, suggesting that publication bias may be small (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

(A) Forest plot showing the relationship between diabetes and lacune. (B) Forest plot showing the relationship between diabetes and WMH. (C) Funnel plot of diabetes on WMH. CI = confidence interval, WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

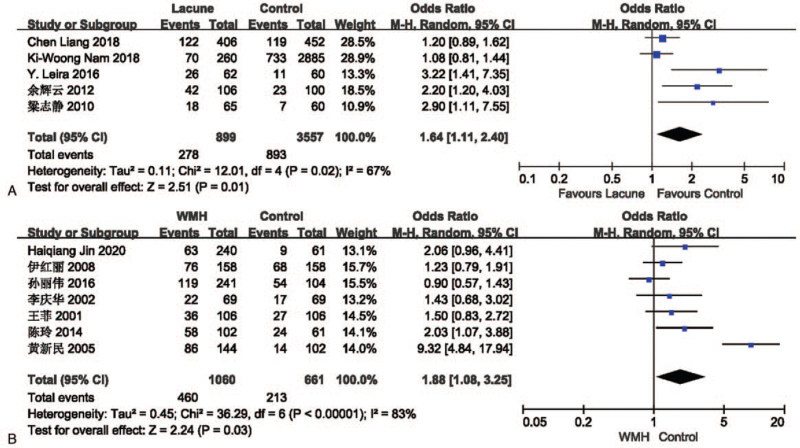

3.3.3. Hyperlipidemia

The effect of hyperlipidemia on lacune was analyzed in 5 studies involving 899 in the lacune group and 3557 in the control group. The pooled results of these studies indicated that people with hyperlipidemia are more likely to get CSVD (OR = 1.64; 95% CI 1.11-2.40; P = .01; I2 = 67%). The effect of hyperlipidemia on WMH was analyzed in 7 studies involving 1060 in the WMH group and 661 in the control group. The pooled results of these studies indicated that people with hyperlipidemia are more likely to get CSVD (OR = 1.88; 95% CI 1.08-3.25; P = .03; I2 = 83%) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

(A) Forest plot showing the relationship between hyperlipidemia and lacune. (B) Forest plot showing the relationship between hyperlipidemia and WMH. CI = confidence interval, WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

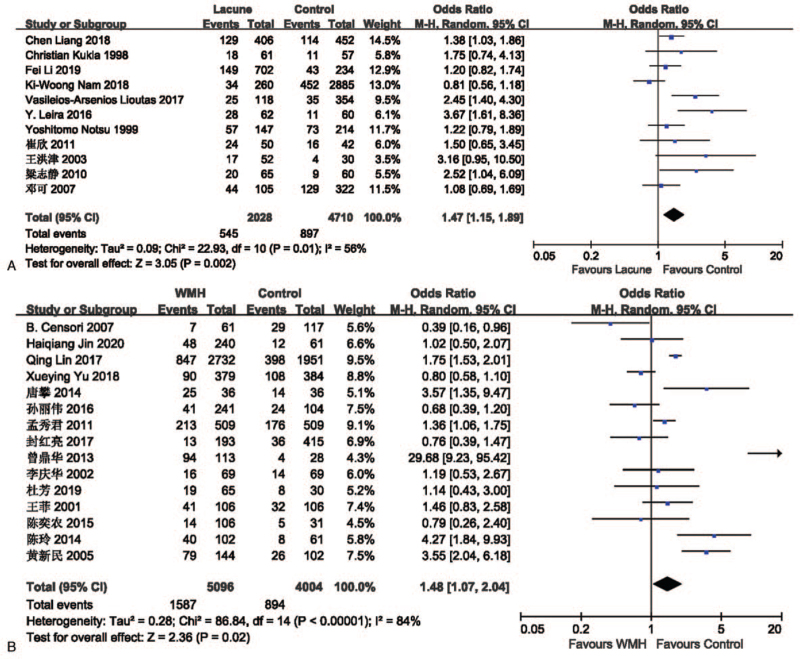

3.3.4. Smoking

The effect of smoking on lacune was analyzed in 11 studies involving 2028 in the lacune group and 4710 in the control group. The pooled results of these studies indicated that people who smoke are more likely to get CSVD (OR = 1.47; 95% CI 1.15-1.89; P = .002; I2 = 56%). The effect of smoking on WMH was analyzed in 15 studies involving 5096 in the WMH group and 4004 in the control group. The pooled results of these studies indicated that people who smoke are more likely to get CSVD (OR = 1.48; 95% CI 1.07-2.04; P = .02; I2 = 84%) (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

(A) Forest plot showing the relationship between smoking and lacune. (B) Forest plot showing the relationship between smoking and WMH. CI = confidence interval, WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

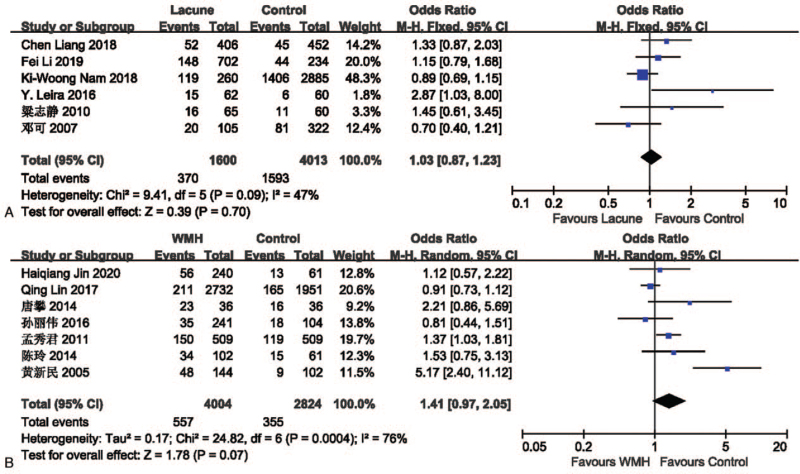

3.3.5. Drinking

The effect of drinking on lacune was analyzed in 6 studies involving 1600 in the lacune group and 4013 in the control group. The pooled results of these studies indicated that people who drink are more likely to get CSVD (OR = 1.03; 95% CI 0.87-1.23; P = .70; I2 = 47%), but it is not statistically significant. The effect of drinking on WMH was analyzed in 7 studies involving 4004 in the WMH group and 2824 in the control group. The pooled results of these studies indicated that people who drink are more likely to get CSVD (OR = 1.41; 95% CI 0.97-2.05; P = .07; I2 = 76%) (Fig. 8), but it is not statistically significant.

Figure 8.

(A) Forest plot showing the relationship between drinking and lacune. (B) Forest plot showing the relationship between drinking and WMH. CI = confidence interval, WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

3.4. Sensitivity analysis and publication bias evaluation

Excluding studies one by one for sensitivity analysis, and the conclusion is stable. When the number of studies included is greater than or equal to 15, the funnel chart is drawn (Figs. 4 and 5). The funnel chart is basically symmetrical, suggesting that the publication bias may be small.

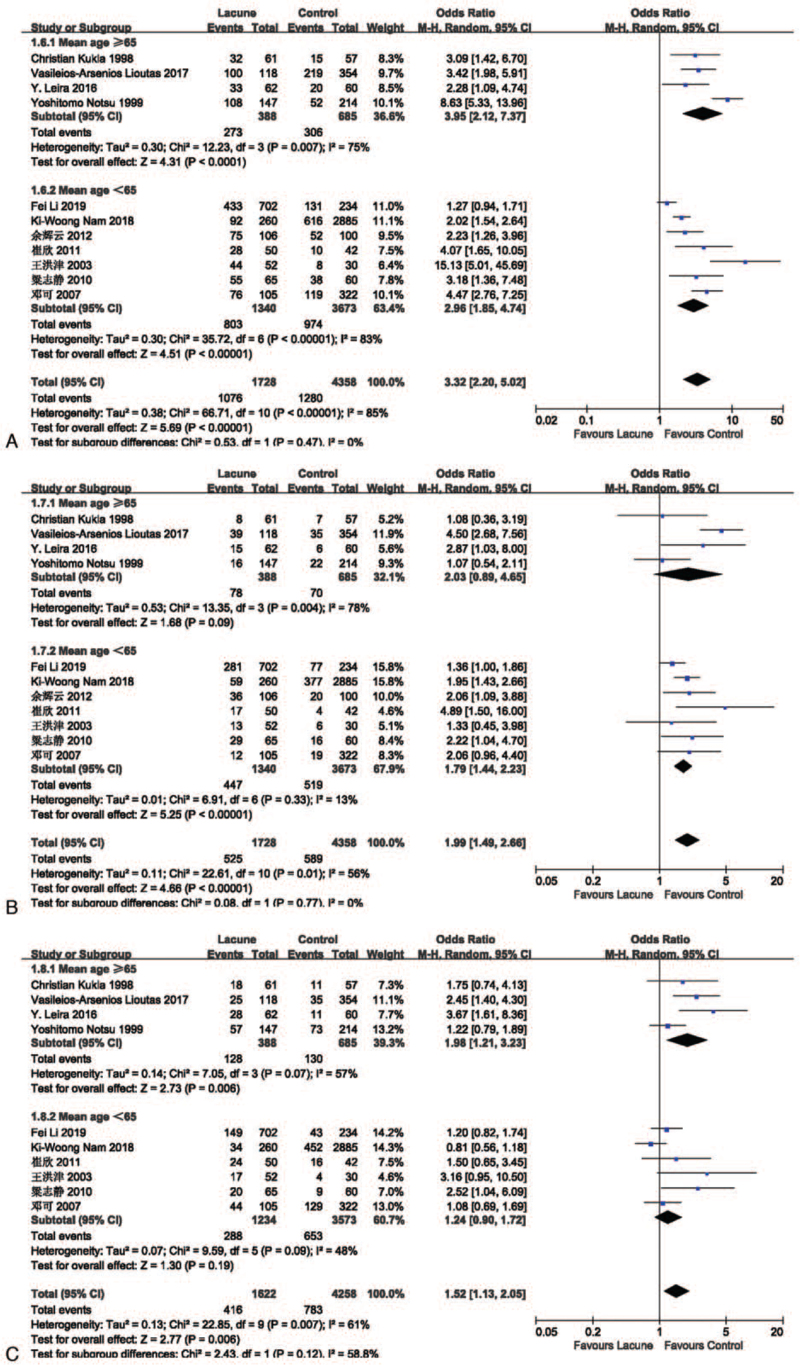

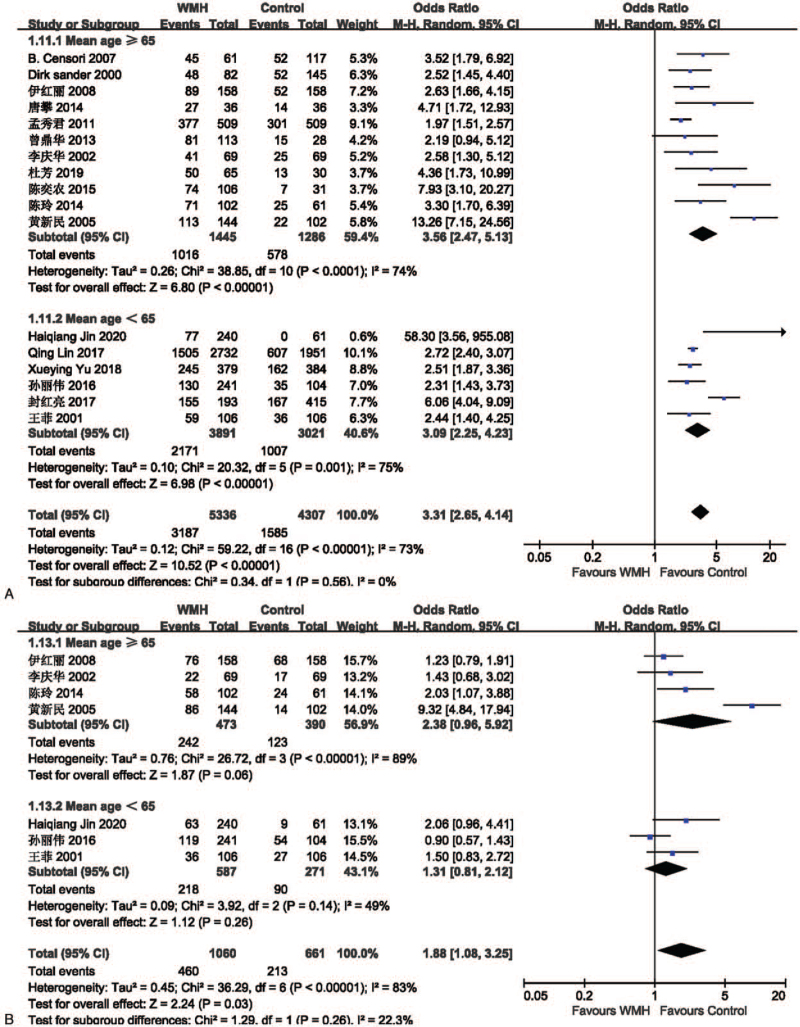

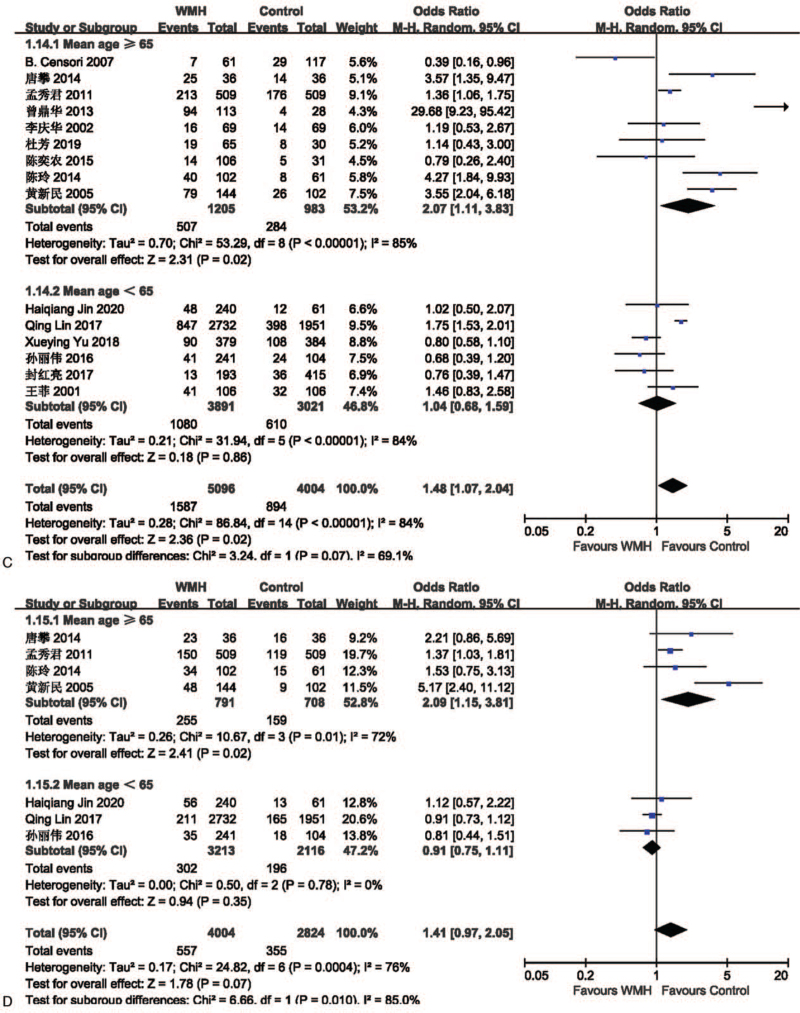

3.5. Subgroup analysis

We performed a subgroup analysis based on the mean age of each study. The studies were divided by mean age into an elderly group (mean age of the included population ≥65) and a non-elderly group (mean age of the included population <65). In the lacune-related subgroup analysis, the OR values of hypertension, diabetes, and smoking in the elderly group were higher than those in the non-elderly group (Fig. 9), in which hyperlipidemia and drinking were not included because of insufficient literature. The results showed that hypertension, diabetes, and smoking were more closely associated with lacune in the elderly group compared to the non-elderly group, which implies that age is an important influencing factor for lacune. In the subgroup analysis of WMH, the OR values of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking, and drinking in the elderly group were higher than those in the non-elderly group (Fig. 10 A-D), while the OR value of diabetes in the elderly group was lower than that in the non-elderly group (Fig. 10 E). The results showed that hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking, and drinking were more closely associated with WMH in the elderly group compared to the non-elderly group. This subgroup analysis proves that the older the age, the stronger the effect of each risk factor on CSVD, so we should take measures to control it at an early stage.

Figure 9.

(A) Forest plots showing the relationship between hypertension and lacune in different mean age groups. (B) Forest plot showing the relationship between diabetes and lacune in different mean age. (C) Forest plot showing the relationship between smoking and lacune in different mean age. CI = confidence interval.

Figure 10.

(A) Forest plots showing the relationship between hypertension and WMH in different mean age groups. (B) Forest plot showing the relationship between hyperlipidemia and WMH in different mean age. (C) Forest plots showing the relationship between smoking and WMH in different mean age groups. (D) Forest plot showing the relationship between drinking and WMH in different mean age. (E) Forest plots showing the relationship between diabetes and WMH in different mean age groups. CI = confidence interval, WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

Figure 10 (Continued).

(A) Forest plots showing the relationship between hypertension and WMH in different mean age groups. (B) Forest plot showing the relationship between hyperlipidemia and WMH in different mean age. (C) Forest plots showing the relationship between smoking and WMH in different mean age groups. (D) Forest plot showing the relationship between drinking and WMH in different mean age. (E) Forest plots showing the relationship between diabetes and WMH in different mean age groups. CI = confidence interval, WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

Figure 10 (Continued).

(A) Forest plots showing the relationship between hypertension and WMH in different mean age groups. (B) Forest plot showing the relationship between hyperlipidemia and WMH in different mean age. (C) Forest plots showing the relationship between smoking and WMH in different mean age groups. (D) Forest plot showing the relationship between drinking and WMH in different mean age. (E) Forest plots showing the relationship between diabetes and WMH in different mean age groups. CI = confidence interval, WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

4. Discussion

CSVD is a kind of neurodegenerative disease, which refers to brain parenchymal damage related to pathological changes in the distal pia mater and cerebral blood vessels. Epidemiology shows that about a quarter of ischemic strokes are caused by cerebral small vessel disease, which accounts for 83.8% of all cerebrovascular diseases.[8] CSVD is an important contributor to stroke, dyskinesia, cognitive, and affective disorders, but its onset is insidious, mostly in a resting state, and has not been paid attention to in clinical practice, with a poor prognosis.[9] Previously, some studies have reported that CSVD is related to many risk factors, such as age, cardiovascular risk factors, inflammation, kidney disease, infection and so on,[10–13] but the results are not entirely consistent. We chose 5 common factors from them and proved that hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking are the risk factors of lacune and WMH while drinking is not. At present, the pathogenesis of CSVD is still unclear, and there is a lack of unified and effective treatment plan. Some studies reported that patients with moderate or severe WMH are highly likely to continue to progress, whereas patients with milder baseline CSVD showed slight progress in 9 years,[14] which also shows from the side the importance of prevention. Regular examination and timely correction of the 4 risk factors of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking in healthy people can prevent the occurrence of CSVD. Traditionally, the progress of CSVD is regarded as a continuous and gradual process, but recent studies have shown that the progress of CSVD is nonlinear, accelerated with the passage of time,[15] and is a highly dynamic procedure.[16] Therefore, for patients with CSVD, we should control the risk factors at an early stage in time to slow down the development of CVSD. For now, antihypertensive therapy is one of the most effective methods to alleviate CSVD,[17] while anticoagulation, antiplatelet therapy, and lipid-regulating therapy are currently lacking sufficient evidence to support them. Our results also support this view that there is a great correlation between hypertension and CSVD. Besides, in our study, hyperlipidemia is also a risk factor for CSVD, which provides evidence for lipid-modifying therapy.

Epidemiological investigations show that the older the age, the higher the incidence of CSVD.[4] In the subgroup analysis stratified by mean age, the OR value of the elderly group is basically higher than that of the non-elderly group, indicating that the older people are more likely to suffer from CSVD under the same exposure factors, which supports the above view. One exception to this is that in the meta-analysis related to WMH, the OR of diabetic patients in the elderly group was smaller than in the non-elderly group. For this result, we have 2 speculations: The insufficient number or quality of included studies. In one of the studies among the non-elderly group, no one in the control group had diabetes, which made its OR value much larger than any other study, thus pulling up the OR of the non-elderly group. There may be some unknown association between age, WMH, and diabetes. From an overall perspective, drinking cannot be considered as a risk factor for CSVD, because their P values are all greater than .05, which is not statistically significant. However, subgroup analysis showed that in the elderly group, drinking is a risk factor for WMH (OR = 2.09; 95% CI 1.15-3.81; P = .02). The pathways by which drinking leads to CSVD may be that ethanol directly stimulates the blood vessel wall, causing it to lose elasticity, making it inelastic, and the intermediate metabolite of ethanol in the body, acetaldehyde, has a strong lipid peroxidation reaction and toxicity, which can damage the vascular endothelial system.[18] As alcohol consumption and drinking years increase, its destructive effect enhances, which may partly explain the results of the subgroup analysis. Therefore, further studies are needed to determine whether drinking is a risk factor for CSVD.

4.1. Advantages and limitations

Most studies on risk factors for CSVD use the method of case-control study to specifically assess the relationship between a factor and CSVD through multifactorial regression analysis.[19] For the first time, we choose the method of meta-analysis to analyze the risk factors of CSVD, which can synthesize the existing research and draw a more reasonable conclusion.[20] Secondly, we included multiple studies with a total of 16,587 participants to illustrate the relationship between hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, smoking, alcohol consumption, and CSVD, which is impossible in a single-center study. Finally, in the course of our research, we discovered some new questions (such as what is the target blood pressure for antihypertensive treatment? Is diabetic retinopathy related to CSVD? Is drinking years related to CSVD?), which pointed out the direction for further research. Yet, this meta-analysis also has some limitations. Clear definitions of smoking and drinking were not given in the respective studies, which may lead to inaccurate OR. Although we used a random effects model to try to avoid the effect of heterogeneity,[21] there was still significant heterogeneity and no obvious source of heterogeneity was found. In addition, most of the included studies are in China, but the prevalence of CSVD in China is higher than average. A survey in 4 Chinese cities reported that lacune accounted for 42.3% of ischemic strokes, higher than the 25% to 30% reported in many international studies.[22] Because of the large proportion of Chinese studies, the overall OR will be large and closer to the level of the Chinese population. The included studies are all retrospective studies, and causality cannot be determined, large prospective studies are needed to prove our conclusions.

5. Conclusion

Our study proves that hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking are risk factors for CSVD. We should pay attention to these factors and control them early, which has a positive effect on delaying the development of CSVD.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Kai Zheng, Zheng Wang.

Data curation: Zheng Wang, Jiajie Chen.

Formal analysis: Zheng Wang, Qin Chen.

Investigation: Jiajie Chen, Ni Yang.

Methodology: Qin Chen, Jiajie Chen, Ni Yang.

Software: Zheng Wang, Jiajie Chen

Writing – original draft: Zheng Wang.

Writing – review & editing: Kai Zheng, Zheng Wang.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval, CSVD = cerebral small vessel disease, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, NOS = Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, OR = odds ratio.

How to cite this article: Wang Z, Chen Q, Chen J, Yang N, Zheng K. Risk factors of cerebral small vessel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2021;100:51(e28229).

The study was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (item number: 2019kfyXKJC055).

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are publicly available.

References

- [1].Li Q, Yang Y, Reis C, et al. Cerebral small vessel disease. Cell Transplant 2018;27:1711–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hilal S, Mok V, Youn YC, Wong A, Ikram MK, Chen CL. Prevalence, risk factors and consequences of cerebral small vessel diseases: data from three Asian countries. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2017;88:669–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tsai CF, Thomas B, Sudlow CL. Epidemiology of stroke and its subtypes in Chinese vs white populations: a systematic review. Neurology 2013;81:264–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cannistraro RJ, Badi M, Eidelman BH, Dickson DW, Middlebrooks EH, Meschia JF. CNS small vessel disease: a clinical review. Neurology 2019;92:1146–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Smith EE, Beaudin AE. New insights into cerebral small vessel disease and vascular cognitive impairment from MRI. Curr Opin Neurol 2018;31:36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wardlaw JM, Smith C, Dichgans M. Small vessel disease: mechanisms and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol 2019;18:684–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cheung MW, Vijayakumar R. A guide to conducting a meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev 2016;26:121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Moran C, Phan TG, Srikanth VK. Cerebral small vessel disease: a review of clinical, radiological, and histopathological phenotypes. Int J Stroke 2012;7:36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pantoni L. Cerebral small vessel disease: from pathogenesis and clinical characteristics to therapeutic challenges. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:689–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Han F, Zhai FF, Wang Q, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of cerebral small vessel disease in a Chinese population-based sample. J Stroke 2018;20:239–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Low A, Mak E, Rowe JB, Markus HS, O’Brien JT. Inflammation and cerebral small vessel disease: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev 2019;53:100916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Toyoda K. Cerebral small vessel disease and chronic kidney disease. J Stroke 2015;17:31–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Aarabi G, Thomalla G, Heydecke G, Seedorf U. Chronic oral infection: an emerging risk factor of cerebral small vessel disease. Oral Dis 2019;25:710–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].van Leijsen EMC, de Leeuw FE, Tuladhar AM. Disease progression and regression in sporadic small vessel disease-insights from neuroimaging. Clin Sci (Lond) 2017;131:1191–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Arba F, Leigh R, Inzitari D, Warach SJ, Luby M, Lees KR. STIR/VISTA Imaging Collaboration. Blood-brain barrier leakage increases with small vessel disease in acute ischemic stroke. Neurology 2017;89:2143–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].van Leijsen EMC, van Uden IWM, Ghafoorian M, et al. Nonlinear temporal dynamics of cerebral small vessel disease: The RUN DMC study. Neurology 2017;89:1569–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].van Middelaar T, Argillander TE, Schreuder FHBM, Deinum J, Richard E, Klijn CJM. Effect of antihypertensive medication on cerebral small vessel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2018;49:1531–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cuadrado-Godia E, Dwivedi P, Sharma S, et al. Cerebral small vessel disease: a review focusing on pathophysiology, biomarkers, and machine learning strategies. J Stroke 2018;20:302–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhou LW, Panenka WJ, Al-Momen G, et al. Cerebral small vessel disease, risk factors, and cognition in tenants of precarious housing. Stroke 2020;51:3271–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Haase SC. Systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;127:955–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Das AS, Regenhardt RW, Vernooij MW, Blacker D, Charidimou A, Viswanathan A. Asymptomatic cerebral small vessel disease: insights from population-based studies. J Stroke 2019;21:121–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]