Abstract

Macropinocytosis, an evolutionarily conserved endocytic mechanism that mediates non-specific fluid-phase uptake, is potently upregulated by various oncogenic pathways. It is now well appreciated that high macropinocytic activity is a hallmark of many human tumors, which use this adaptation to scavenge extracellular nutrients for fueling cell growth. In the context of the nutrient-scarce tumor microenvironment, this process provides tumor cells with metabolic flexibility. However, dependence on this scavenging mechanism also illuminates a potential metabolic vulnerability. As such, there is a great deal of interest in understanding the molecular underpinnings of macropinocytosis. In this review we will discuss the most recent advances in characterizing macropinocytosis: the pathways that regulate it, its contribution to the metabolic fitness of cancer cells, and its therapeutic potential.

Keywords: macropinocytosis, membrane ruffling, metabolic fitness, nutrient scavenging, RAS

Macropinocytosis: from cell drinking to metabolic fitness.

Macropinocytosis was described as a ‘cell drinking’ phenomenon in 1931 by Warren H. Lewis [1]. Using live time-lapse imaging of mouse macrophages and sarcoma cells, he observed wave structures at the cell periphery, which coincided with the formation of intracellular vesicles. Subsequent studies have established that macropinocytosis is a mode of clathrin and caveolin-independent endocytosis that is mediated by F-actin remodeling which in turn drives the formation of plasma membrane ruffles, leading to the generation of heterogeneously sized vesicles called macropinosomes (Box 1). In the process of their formation, macropinosomes engulf extracellular fluids and solutes affording a mechanism of non-selective, fluid-phase uptake.

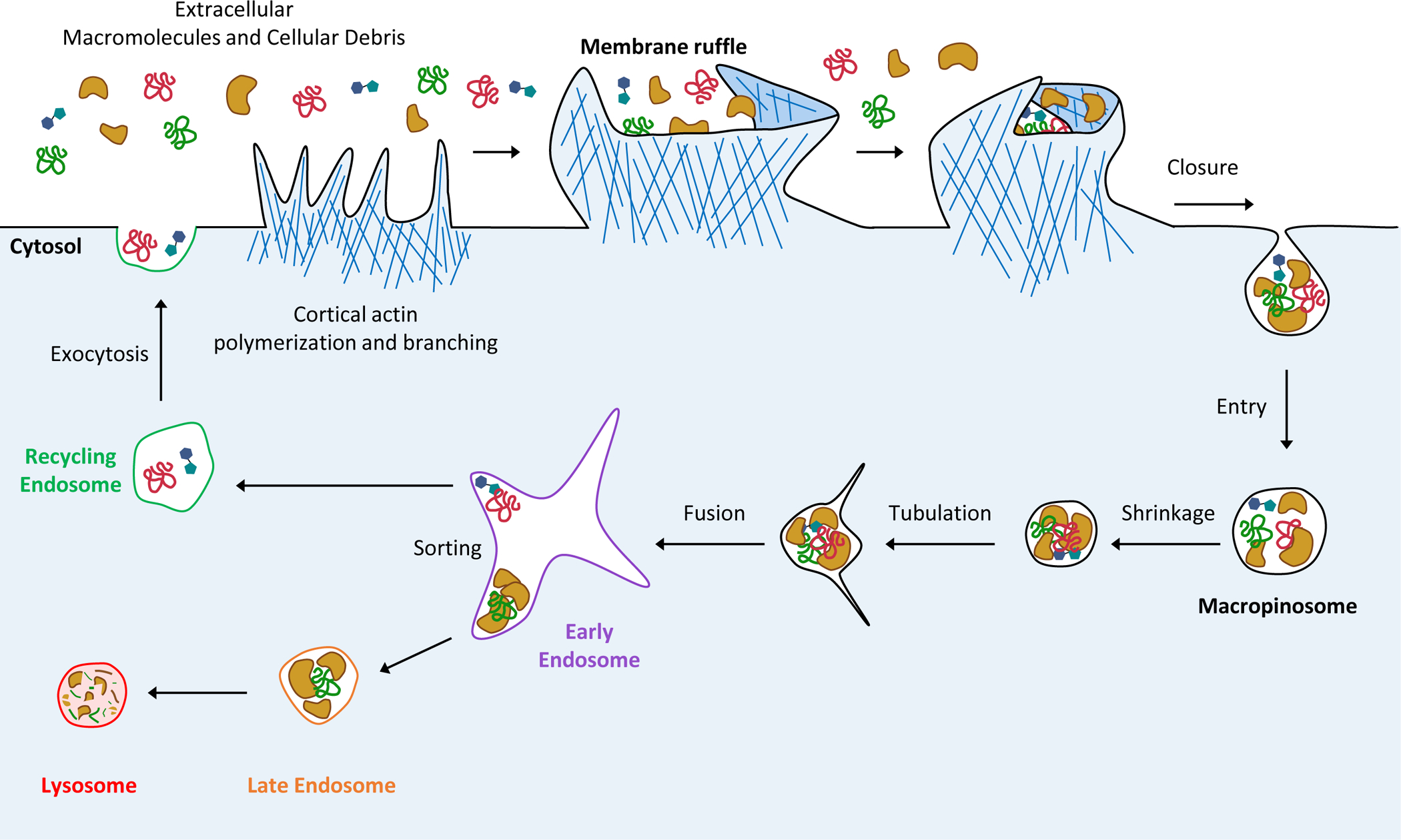

Box 1. Macropinosome formation, maturation and trafficking.

Macropinosomes are large, endocytic vesicles ranging in size from 0.2–5 μm [81]. Their formation is initiated at actin-rich, membrane protrusions called membrane ruffles, which are formed by the protrusive forces generated by the polymerization and branching of sub-membranous cortical actin (Figure I) [82]. These protrusions extend out from the cell surface and fold back on themselves, encapsulating extracellular fluid [82]. Upon entry into the cytosol, nascent macropinosomes undergo extensive remodeling that is mediated by the two-pore channel (TPCs)-dependent sodium ion efflux, causing subsequent luminal fluid loss by osmosis [83, 84]. This reduction in luminal hydrostatic pressure then promotes the recruitment of BAR domain proteins, such as members of the sorting nexin family that orchestrate membrane deformation and tubulation. [83–85]. Tubules are physically separated from macropinosomes by membrane scission and are subsequently sorted and delivered to specific intracellular compartments via microtubule-dependent transport [84, 85]. Hence, macropinosome tubulation is important for facilitating compartmentalization and sorting of macropinosome membranes and cargoes. These trafficking events are coordinated by Rab GTPase family proteins, which are sequentially recruited to macropinosomes as they progress through the endocytic pathway [82]. Following their multistep maturation and fusion with early endosomes [84], macropinosomes contents proceed down one of two pathways: the degradative pathway or the recycling pathway. The degradative pathway culminates with the fusion of macropinosomes and the lysosome network where their cargoes are degraded by hydrolytic enzymes [5]. Conversely, the recycling pathway facilitates the exocytosis of macropinosome cargoes and the return of endocytic membrane material to the plasma membrane [86]. This pathway is important for replenishing plasma membrane lipids, regulation of cell volume and potentially plays a role in the trafficking and distribution of cell surface proteins. The exact mechanisms that determine the choice between these itineraries and ultimately the fate of macropinosome cargo remains elusive. A mechanistic description of these processes will be important in order to gain a better understanding of how macropinocytosis mediates its diverse functions in nutrient supply, immunity and signaling.

Figure I (associated with Box 1). Macropinosome formation, maturation and trafficking.

The construction of membrane ruffles requires the coordinated polymerization and branching of the cortical actin cytoskeleton. The protrusive forces generated by these rearrangements leads to formation of membrane extensions that fold back onto the plasma membrane and encapsulate extracellular fluid. Scission from the plasma membrane allows endocytic vesicles called macropinosomes to enter the cytosol where they undergo remodeling (shrinkage and tubulation), facilitating their sorting and trafficking. Macropinosome cargoes are sorted in early endosome compartments to one of two pathways: the degradative pathway, which culminates in fusion with the lysosomal network and the subsequent hydrolysis of cargoes; or the recycling pathway where macropinosomes are delivered back to the plasma membrane via the exocytosis of recycling endosomes.

RAS proto-oncogenes (HRAS, NRAS and KRAS) are among the most frequently mutated genes in human cancers [2]. The cycling of RAS proteins between their active (GTP-bound) and inactive (GDP-bound) conformations is regulated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) which catalyze GTP exchange and hydrolysis, respectively [2]. Oncogenic mutations in RAS proteins that interfere with GTP hydrolysis favor GTP binding, thereby rendering them constitutively active leading to aberrant survival and proliferation [2]. Oncogenic RAS is also a direct stimulator of macropinocytosis, a phenotype first reported over thirty years ago [3]. However, the functional implications of this oncogene-driven response only began to be recognized over the past decade as a result of major advances in our understanding of the metabolic dependencies of tumor cells. In particular, studies in cancer metabolism have revealed that tumor cells are critically reliant on the uptake of extracellular nutrients such as glutamine and glucose via membrane transporters for the generation of biomass necessary to sustain rapid cell growth and proliferation [4]. However, in the context of solid tumors, the capacity of cells to exploit these nutrient import mechanisms is severely compromised due to limited availability of nutrients imposed by poor vascularization [4]. In search for adaptations that allow tumor cells to grow in nutrient poor environment, Commisso et al. posited that macropinocytosis of extracellular protein could serve as an alternative nutrient acquisition route [5]. This notion was confirmed by demonstrating that the uptake of extracellular proteins by macropinocytosis and their subsequent lysosomal degradation was sufficient to support proliferation under conditions of amino acid deprivation [5]. It is now recognized that the metabolic flexibility imparted by macropinocytic scavenging of macromolecules represents an important determinant of tumor cell fitness and a potentially targetable vulnerability. In this review, we will discuss the most recent insights into the regulation of macropinocytosis, its contributions to cancer cell metabolism and how targeting macropinocytosis may provide potential therapeutic opportunities.

Macropinocytic cargoes and nutrient scavenging.

Unlike phagocytosis and receptor-mediated endocytosis, which rely on specific receptor-cargo interactions, macropinocytosis is non-selective in terms of its internalization capabilities [6]. Cancer cells capitalize on this promiscuous uptake mechanism to scavenge a diverse range of extracellular macromolecules that are typically not accessible to non-transformed cells with low macropinocytic activity. In this section, we will discuss the key studies delineating the macromolecules and other smaller cargoes that cancer cells can internalize by macropinocytosis and the impact of their acquisition on tumor cell fitness.

Extracellular proteins.

The concept that the degradation products of macropinocytosed extracellular protein could support cancer cell metabolism was initially tested using albumin, the most abundant serum protein. Indeed, albumin internalized by macropinocytosis was shown to be catabolized in the lysosome to yield amino acids that could support proliferation under conditions of glutamine and essential amino acid deprivation [5, 7]. Metabolomics analysis of human and mouse pancreatic tumors provided further evidence of macropinocytosis-dependent uptake and catabolism of albumin in vivo [8, 9].

Given that the lysosomal degradation of albumin is a strict prerequisite for its utilization as a nutrient source, factors that influence this process ultimately affect the efficacy of macropinocytosis as a nutrient supply route. For example, the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn), which binds albumin, is a recycling receptor that is responsible for extending the half-life of albumin in the circulation by rescuing it from lysosomal degradation and releasing it into the blood [10, 11]. Accordingly, knockdown of FcRn in tumor cell lines results in a significant increase in intracellular albumin and glutamate as well as enhancement of tumor growth [12, 13].

In addition to albumin, extracellular matrix (ECM) components can provide a rich source of extracellular protein for scavenging. A prevalent histological feature of several types of solid human tumors is a fibrotic tumor microenvironment (TME) composed of dense, collagen-rich stroma that is deposited by cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) [14]. During the remodeling and hydrolysis of the ECM, fragments of abundant proteins like collagen and fibronectin may gain access to macropinosomes and could provide another potential source of amino acids [9, 15]. ECM-derived collagen has specifically been shown to provide a reservoir of proline. As such, under conditions of glucose and glutamine depletion, proline supplied from the macropinocytosis of extracellular collagen could support the proliferation of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells [15]. Furthermore, the utilization of internalized collagen by PDAC cells can be facilitated by the overexpression of the proline catabolizing enzyme, proline oxidase (PRODH1), which provides intermediates for glutamine synthesis that subsequently fuel the TCA cycle [15]. These findings demonstrate another direct mechanism by which macropinocytosis-dependent protein scavenging can promote metabolic flexibility by accessing alternative nutrient sources.

Necrotic cell debris (necrocytosis).

Cellular debris in the TME and in necrotic regions of tumors can also be internalized via a macropinocytosis-dependent process termed necrocytosis [16, 17]. This mechanism of nutrient scavenging contributes to amino acid and lipid pools and can support proliferation in prostate, breast and pancreatic cancer cell lines under nutrient-limiting conditions [16, 17]. Scavenging of cellular debris (or apoptotic bodies) could in principle supply saccharides, lipids, amino acids and nucleotides and therefore represents a rich and diverse nutrient source that can fuel multiple metabolic pathways simultaneously. Indeed, under certain nutrient limiting conditions, necrotic cell debris uptake appears to offer a greater anabolic value compared to albumin [16]. Necrocytosis may also be of particular utility in areas of tumors where necrotic debris is more abundant (such as in hypoxic areas) where it would potentially confer regional survival benefits to metabolically stressed tumor cells.

Nucleotides.

In addition to extracellular macromolecules, macropinocytosis has also been shown to mediate the scavenging of smaller biomolecules such as amino acids, copper, and nucleotides [18–21]. The uptake of extracellular ATP by macropinocytosis has been shown to enrich intracellular ATP pools, thereby sustaining cellular bioenergetics [20]. It has also been implicated in promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transitions (EMT) and conferring drug resistance to agents targeting nucleotide biosynthesis [17, 20, 22]. Interestingly, there is evidence to suggest that extracellular ATP levels are higher in the interstitium of tumor tissue compared to non-malignant tissues [23]. Macropinocytic tumor cells may also capitalize on elevated extracellular ATP concentrations in the TME and exploit it to increase intracellular ATP pools. By affording access to diverse sources of nutrients, macropinocytosis is emerging as a metabolic adaptation that contributes to multiple fitness determinants. There is also evidence to suggest that macropinocytosis is sensitive to nutrient availability [16, 24, 25]. These important observations invoke the idea that tumor cells can selectively tune macropinocytic activity to modulate nutrient scavenging according to their metabolic needs, further reinforcing the connection between macropinocytosis and metabolic fitness. In addition, a detailed understanding of the context-dependent utilization of macropinocytic cargoes in vivo will be critical for the identification of tumor-specific vulnerabilities that are engendered by this process. Another important area that warrants further investigation is understanding the nature and specificity of the relationship between macropinocytosis and autophagy, a self-degradation recycling mechanism that delivers intracellular components to the lysosome [26]. Recent insight into this comes from a study demonstrating that inhibition of autophagy leads to an NRF2-dependent upregulation of macropinocytosis and dual blockage of these processes synergistically inhibits PDAC tumor growth [27]. These findings and work from other studies demonstrating that key regulators of autophagy can also control macropinocytosis (e.g. mTORC1 and AMPK) [7, 16] have highlighted the possibility that these two adaptive processes may functionally and mechanistically interact. Future studies exploring this connection will be essential to gain a more complete understanding of the metabolic adaptations that drive cell transformation and facilitate the development of strategies to leverage their therapeutic potential.

Oncogenic drivers of macropinocytosis

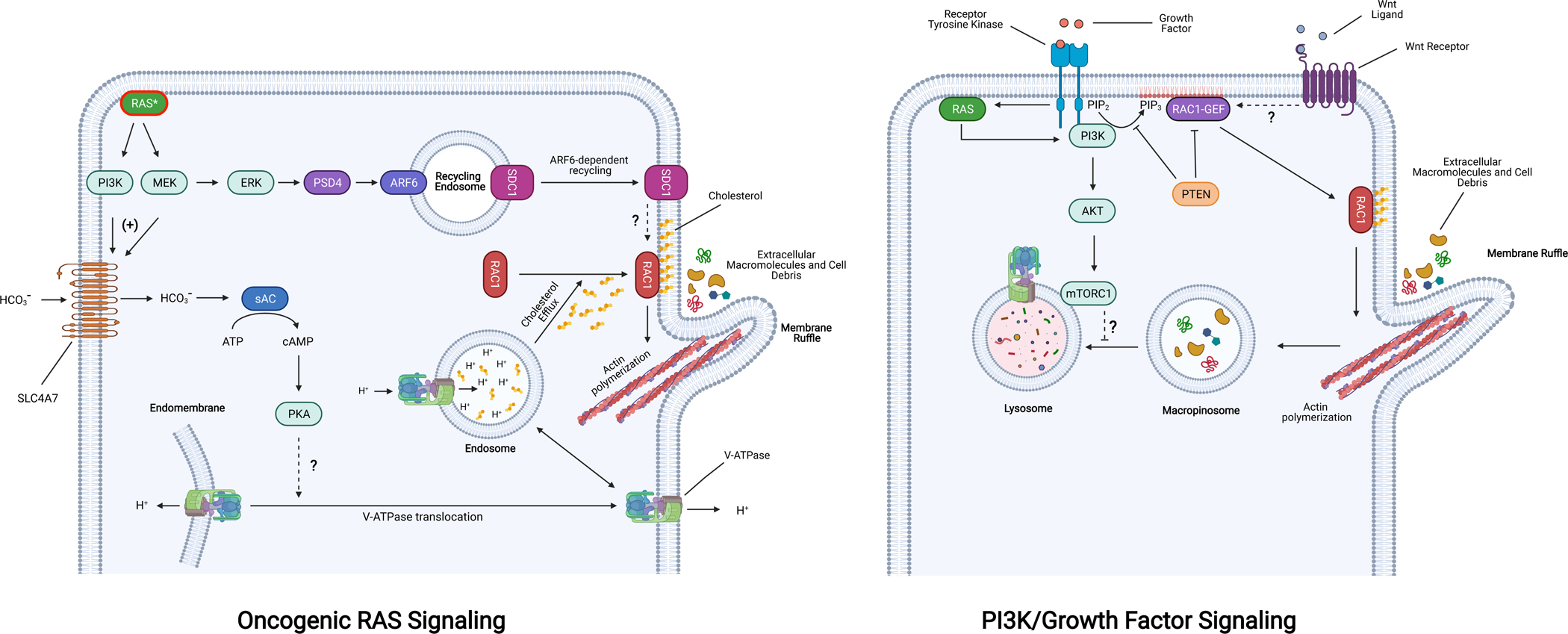

A pre-requisite for macropinosome formation, the initial rate-limiting step of macropinocytosis, is the activation of plasma membrane associated-Rac1 and the subsequent remodeling of the cortical actin cytoskeleton [28]. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that oncogenic signaling pathways that drive macropinocytosis converge on the regulation of Rac1 activity and localization (Fig. 1). In this section, we will review recent advances in our understanding of the molecular attributes of these signaling axes.

Figure 1. Regulation of macropinocytosis by oncogenic signaling.

Oncogenic RAS (RAS*) stimulates macropinocytosis through the activation of downstream effectors that converge on the activation of Rac1 at the plasma membrane, which in turn coordinates the regulation of actin remodeling complexes. Two kinases that are activated by oncogenic RAS, MEK and PI3K, promote the transcriptional upregulation (+) of the sodium-coupled bicarbonate transporter (SLC4A7). Intracellular bicarbonate stimulates sAC-mediated cAMP production and subsequent PKA activation, which triggers the translocation of the V-ATPase from endomembranes to the plasma membrane by an unknown mechanism. This translocation event is required for cholesterol efflux from endosomes to the plasma membrane, a prerequisite for the plasma membrane association of Rac1. Activation of MAP kinase signaling via oncogenic RAS also leads to the ARF6-dependent recycling of SDC1-containing endosomes via PSD4, resulting in localization of SDC1 to the plasma membrane where it activates Rac1 through an unknown mechanism. In the context of wild type RAS, PI3K activity (by growth factor signaling or mutational activation) promotes PIP3 accumulation in the plasma membrane and the activation of Rac1-GEFs, both of which are counteracted by the phosphatase PTEN. Activation of mTORC1 downstream of PI3K/AKT negatively regulates macropinosome-lysosome fusion. Stimulation of canonical Wnt signaling also promotes macropinocytosis through an undetermined mechanism that likely depends on activation of specific Rac1 GEFs that are transcriptional targets. Abbreviations: PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinases; SDC1, syndecan-1; V-ATPase, vacuolar ATPase; sAC, soluble adenylate cyclase; ARF6, ADP ribosylation Factor 6; PSD4, pleckstrin and SEC7 domain-containing 4; PKA, protein kinase A; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; mTORC1, mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1. Figure was created with BioRender.com.

Oncogenic RAS signaling.

Despite the well-established role of Rac1 as an effector of oncogenic RAS-induced macropinocytosis, the finer mechanistic details of this effector pathway have only recently emerged. A whole-genome siRNA screen for regulators of oncogenic RAS-induced macropinocytosis identified an essential role for the vacuolar-type H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) [29]. Investigation of the mechanistic basis for this requirement led to the delineation of a previously unrecognized pathway linking oncogenic RAS to the activation of Rac1 and the induction of macropinocytosis. This pathway is initiated by oncogenic RAS-dependent upregulation of the sodium-coupled bicarbonate transporter (encoded by SLC4A7), leading to an increase in bicarbonate influx, and the sequential activation of bicarbonate-dependent soluble adenylate cyclase (sAC) and cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) [29] (Fig. 1). The activation of PKA results in, by a mechanism yet to be defined, the re-localization of the V-ATPase from endomembranes to the plasma membrane. This translocation event facilitates the efflux of cholesterol from endosomes to the plasma membrane where its presence is required for Rac1 localization and signaling [30]. Another recent study using in vivo proteomic surfaceome screening identified the proteoglycan syndecan-1 (SDC1) as an essential mediator of oncogenic RAS-induced macropinocytosis via Rac1 activation [31]. Oncogenic KRAS was shown to upregulate expression of the ARF6-specific GEF, pleckstrin and SEC7 domain-containing 4 (PSD4) through the MAPK pathway, leading to ARF6-dependent recycling of SDC1 to the plasma membrane, where it activates Rac1 by an unknown mechanism [31] (Fig. 1). Both SDC1 and SLC4A7 were shown to be required for pancreatic tumorigenesis, underscoring the essential role of macropinocytosis in promoting tumor growth [29,31].

PI3K/PTEN pathway.

Class I phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3K) catalyze the phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) leading to generation of the second messenger phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) [32]. PIP3 accumulation in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane is required for the activation of a number of Rac1-specific GEFs, such as Vav, Tiam-1, Swap-70, and Sos-1 [33–38]. These GEFs contain Dbl homology (DH) and pleckstrin homology (PH) domains, which represent the catalytic core and a phosphoinositide-binding surface, respectively. Binding of PIP3 to the PH domain leads to their activation by relieving an intramolecular inhibitory conformation [36, 37, 39] or by promoting membrane localization [34, 40]. In addition to its requirement for the formation of membrane ruffles via Rac1, PIP3 is also involved in macropinosome closure [41, 42]. The requirement of PI3K signaling for oncogenic RAS-induced macropinocytosis is well-established [43, 44]. In these settings, the activation of PI3K is elicited by the direct interaction of its catalytic subunit p110α (encoded by PIK3CA) with oncogenic RAS [32]. More recently, evidence for oncogenic RAS-independent role of PI3K signaling in promoting macropinocytic nutrient scavenging has been emerging. Cancer-associated hyperactivation of PI3K signaling occurs principally by two mechanisms: acquisition of activating mutations in PIK3CA, or loss of PTEN, the PIP3 phosphatase that counteracts PI3K signaling [32]. Accordingly, breast cancer cell lines carrying PI3K hotspot mutations (H1047R and E545K) and PTEN-deficient prostate cancer cells display constitutive macropinocytosis [16, 17]. PTEN has also been shown to bind to and inhibit the activity of the Rac1 GEF, P-REX2 [45]. Therefore, in addition to augmenting PI3K-signalling, loss-of-PTEN can lead to the activation of Rac1 independently of its PIP3 phosphatase activity. Other modes of oncogenic RAS-independent stimulation of macropinocytosis via PI3K have been proposed as well. For example, the atypical KRASG12R mutation impairs the ability of KRAS to bind to and activate the p110α catalytic subunit of PI3K [46]. Despite this defect, the macropinocytic capacity of KRASG12R-harboring pancreatic cancer cells is retained through an adaptive mechanism involving the upregulation of an alternative PI3K isoform, p110γ [46]. In addition, a recent study revealed that, through the upregulation of their transcriptional target AXL, (an RTK that activates PI3K), YAP1 and TAZ, the co-transcriptional regulator downstream of the Hippo pathway, are required for macropinocytosis in PDAC cells [47]. Since tumors that relapse upon shutdown of oncogenic RAS expression in a PDAC mouse model display a compensatory activation of YAP1, the link between YAP1/TAZ and macropinocytosis might allow pancreatic tumor cells to bypass their dependency on RAS signaling for this nutrient uptake process [48].

While hyperactivation of PI3K signaling can be sufficient to impart constitutive macropinocytosis, in some cells the anabolic benefits of the upregulation of this axis are contextually dependent on nutrient availability. For example, under amino-acid replete conditions, the PI3K effector pathway AKT/mTORC1, suppresses the lysosomal degradation of internalized albumin resulting in the inhibition of albumin-dependent cell proliferation [7]. This inhibitory effect can be overcome by starving cells of amino acids, which leads to the inhibition of mTORC1. Thus, in cells harboring dysregulated PI3K signaling, the utilization of extracellular protein scavenging to support proliferation might depend on the levels of intracellular amino acids.

Canonical Wnt signaling.

Aberrant Wnt signaling has been implicated in the initiation and progression of several malignancies, most notably gastrointestinal cancers, leukemia, and breast cancer [49]. The pathway that has been studied in most detail is the canonical Wnt pathway, which controls the expression of specific target genes through the effector protein β-catenin [50, 51]. In the absence of active Wnt signaling, β-catenin is targeted for degradation by a destruction complex that consists of the scaffold protein AXIN, the tumor suppressor gene product APC, and the kinases CK1 and GSK3β [51]. Binding of Wnt to the receptors Frizzled and LRP6 leads to inhibition of β-catenin degradation through a mechanism that involves the cytoplasmic protein Dishevelled and recruitment of AXIN to LRP6 at the plasma membrane [51]. Subsequently, stabilized β-catenin translocates to the nucleus, where it interacts with members of the TCF/Lef1 family of HMG-box containing transcription factors to co-activate target gene transcription [50]. In colorectal cancer cells, activation of canonical Wnt signaling, either by exposure to soluble Wnt ligands or through loss of function of negative regulators of the pathway (APC, AXIN and GSK3), leads to the stimulation of macropinocytosis [52–54]. While the Rac1/PAK1 axis has been shown to be required for Wnt-driven macropinocytosis [52, 54], the precise mechanisms by which activation of the Wnt pathway is linked to Rac1-dependnent macropinocytosis is not fully understood. A plausible connection is offered by the observation that the Rac1 GEF, TIAM1, is a transcriptional target of canonical Wnt signaling [55]. However, the findings that Wnt stimulation and loss of AXIN rapidly induce membrane ruffling and macropinocytosis independently of de novo protein synthesis suggest the existence of additional, yet to be identified, molecular mediators of Wnt-dependent macropinocytosis [53]. These efforts are warranted in light of the reported contribution of Wnt signaling to macropinocytosis in mutant RAS-driven cancers [54]. Therefore, interference with Wnt-driven macropinocytosis might offer new strategies to target this nutrient supply process in RAS-mutant cancers even in the absence of Wnt pathway activating mutations.

Exploiting macropinocytosis for therapeutic benefit

Renewed interest in tumor metabolism has propelled recent research initiatives towards testing the translational potential of targeting the unique anabolic requirements of cancer cells [56]. Indeed, advances in understanding the metabolic reprogramming of the cancer cell have led to the identification of new, targetable vulnerabilities that could potentially be exploited for therapeutic intervention. However, leveraging of these dependencies has been hampered by the inherent plasticity of cellular metabolism and the associated compensatory pathways that confer metabolic fitness. As a non-specific mode of import for diverse anabolic substrates, macropinocytosis represents a key metabolic liability [17]. In light of this, efforts to develop strategies to target macropinocytosis as well as harness it for selective drug delivery have been on the rise. Below, we highlight some of the most promising, current approaches being used to achieve these goals.

Inhibition of macropinocytosis.

At present, the validation of macropinocytosis as a therapeutic target is based on studies demonstrating that pharmacological or genetic inhibition of the process can inhibit tumor growth. Amiloride-derivatives, such as 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl) amiloride (EIPA), have long been the gold standard experimental tool for preferential inhibition of macropinocytosis over other endocytic mechanisms in cell culture studies [57, 58]. By inhibiting Na+/H+ exchangers, EIPA lowers sub-membranous pH, thereby preventing Rac1 activation and inhibiting macropinosome formation [59]. In vivo studies employing systemic administration of EIPA have demonstrated significant inhibitory effects on tumor growth [5, 16]. Sensitivity to EIPA was displayed specifically by macropinocytosis-proficient tumors and was accompanied by the reduction of macropinocytosis in vivo, consistent with the observed inhibitory effects being, at least in part, the result of target engagement. The opportunity to apply genetic approaches to identify selective targeting strategies for macropinocytosis has recently emerged in the context of the characterization of the sodium-coupled bicarbonate transporter (encoded by SLC4A7) as an essential mediator of oncogenic RAS-induced macropinocytosis [29]. Accordingly, knockdown of SLC4A7 significantly impaired the growth of mutant KRAS, but not wild type KRAS pancreatic cancer xenografts [29]. Finally, recent work has highlighted SDC1 as key regulator of pancreatic tumor growth, likely through its ability to positively regulate macropinocytosis [31]. SDC1 is a particularly attractive potential target, due to its cell surface location and its potential amenability to monoclonal antibody treatment, an approach which is currently being explored in the context of multiple myeloma [60].

While targeting macropinocytosis as a primary means to limiting cancer growth may offer therapeutic benefits, there is also emerging evidence that inhibiting macropinocytosis may potentiate the effects of other anti-cancer drug treatments. A striking example of this concept comes from a study investigating drug resistance in macropinocytic pancreatic and breast cancer cells. Here, they show that the uptake of nucleotide precursors and fatty acids by necrocytosis was able to confer resistance to nucleotide analogs (5-fluorouracil and gemcitabine) and fatty acid synthesis inhibition (FASN inhibitor), respectively [17]. Importantly, inhibition of macropinocytosis in this setting was sufficient to re-sensitize cells to these treatments [17]. In another study, KRAS-mutated colorectal cancer cells have been shown to leverage macropinocytosis for copper uptake [18]. Blockade of macropinocytosis in these cells decreased levels of intracellular copper, a critical metal ion for enhancing the activity of MEK1, a downstream effector of canonical RAS signaling [18, 61]. These data suggest that targeting macropinocytosis could be used to sensitize RAS-mutant cancer cells to copper chelation [18]. In certain scenarios, inhibiting regulators of macropinocytosis may also have corollary knock-on effects that can improve drug treatment. For example, inhibiting the plasma membrane-associated V-ATPase would not only negatively affect macropinocytosis, but would also contribute to decreasing acid flux into the extracellular environment, improving the uptake of weakly basic chemotherapies (e.g. anthracyclines) [62].

Targeted drug delivery.

Currently, one of the major bottlenecks to improving effective drug administration for the treatment of cancer is achieving targeted intracellular delivery of cytotoxic payloads, which would enhance therapeutic efficacy by limiting systemic toxicities. The heightened macropinocytic capacity of some tumor types offers an intriguing opportunity to achieve selective drug delivery using nanoparticle technology. Interfaces between the fields of cancer biology and nanotechnology have led to exciting developments in nanoparticle formulations with therapeutic applications. As such, the conjugation of nanoparticles to cytotoxic compounds has led to a diverse range of nanoparticle formations for the selective delivery of peptides, small molecules, and nucleic acids to tumor cells [63]. The specific size and types of cargoes taken up by macropinocytosis allows for the thoughtful design of nanoparticle formulations that will be preferentially delivered through this mechanism.

One promising approach features the use of protein-based nanoparticle conjugates to promote delivery and accumulation in macropinocytic cells. Among the most commonly used protein-based drug carriers is albumin, chiefly due to its slow clearance rate and its favorable biodistribution among multiple organs [64]. While initial theories stipulated that albumin-drug conjugates would dissociate prior to cellular delivery, it was later appreciated that macropinocytosis-dependent uptake of albumin-drug conjugates as intact complexes could be a primary mechanism of material delivery [65]. As such, using macropinocytosis to improve nanomaterial-based drug delivery is being actively explored. In a recent study, using both genetic and pharmacological tools, cross-linked albumin nanoparticles were shown to be specifically internalized by oncogenic KRAS-driven macropinocytosis [66]. The potential clinical relevance of this mode of drug delivery was recently validated using IGFR1 inhibitors to enhance macropinocytosis, improving delivery and efficacy of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel, Abraxane) [67]. Furthermore, the relative ease by which the physiochemical properties of such nanoparticles can be tailored offers the possibility of constructing conjugates with different toxic payloads for selective delivery to macropinocytic cancer cells.

Macropinocytosis has also been shown to offer an opportunity to achieve tumor-specific delivery of therapeutic nucleic acids (see [68] for a comprehensive review) and peptides. Indeed, targeted delivery of antisense oligonucleotides complexed with polyethylene glycol (PEG)-conjugated nanoparticles have also been documented to occur through macropinocytosis [69]. Lack of colocalization with markers of clathrin-mediated endocytosis and inhibition of uptake with EIPA indicated that cell entry was dependent on macropinocytosis [69]. A similar approach could be leveraged to achieve more specific delivery of peptides, as well. Cell lines with higher macropinocytic activity exhibit enhanced uptake of peptides and peptide mimetics, which can be used to interfere with crucial protein-protein interactions in cancer cells [70]. Lastly, macropinocytosis has proven useful for the delivery of larger biotherapies, including therapeutic bacteria. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), the commonly administered bacteria for turberculosis vaccines, is used in the treatment of superficial bladder cancer — uptake and response in this setting are dictated by productive macropinocytic uptake of the bacterium [71].

While using macropinocytosis as a means of drug delivery shows promise, many hurdles remain. The precise physicochemical properties that optimize nanoparticle uptake preferentially by macropinocytosis (and not other endocytic mechanisms) remain to be determined. Furthermore, particles must be able to enter the cell through macropinocytosis, and then escape into the cytoplasm to interact with their targets, thereby avoiding the common problem of endocytic entrapment. Finally, focusing on ways to potentiate the delivery of compounds by stimulation of macropinocytosis may be an intriguing approach to enhance drug delivery, but will require improved pharmacological tools to selectively manipulate macropinocytosis.

Induction of methuosis.

Alternative approaches for manipulating macropinocytosis for therapeutic intervention involve pharmacological agents that augment macropinocytosis in cancer cells. The rationale for this concept is the induction of methuosis, a form of non-apoptotic cell death characterized by catastrophic vacuolization [72–76]. For example, given that high macropinocytic activity represents a cancer specific adaptation, further enhancing fluid-phase uptake in this setting could be selectively cytotoxic by overwhelming the endocytic system in cancer cells. Multiple genetic and pharmacological approaches have been reported to exacerbate macropinocytosis and stimulate methuosis [77]. Recent research has shown that drug- and genetic-based modulation of a key glycolytic enzyme, PFKB3, in mesothelioma cells can cause stress-induced macropinocytosis, triggering cell death by methuosis [78]. Other work recently showed that indolyl-pyrinidyl-propenones, a family of compounds known to induce methuosis, achieve a similar effect in colorectal cancer cells through inhibition of the class III phosphoinositide kinase, PIKFYVE [79]. While many other compounds are known to induce methuosis [80], more work is needed to understand how key regulators of macropinocytosis may be leveraged to overstimulate this system to achieve therapeutic effects.

Concluding Remarks

Over the past decade, technological and conceptual advances across multiple disciplines have drastically transformed our understanding of the molecular and functional attributes of macropinocytosis. Macropinocytosis is now appreciated as an adaptive cellular process utilized by tumor cells to acquire anabolic substrates under conditions of nutrient scarcity. However, the observation that in mammalian cells, oncogenes and growth factor signaling stimulate macropinocytosis (an energetically expensive process), even in nutrient replete conditions, raises an important question: does macropinocytosis serve specific pro-oncogenic, biological purposes other than nutrient supply (see Outstanding Questions)? Elucidating these additional capabilities of macropinocytosis will not only advance our understanding of how this ancient feeding process contributes more broadly to the transformed phenotype but will also facilitate the development of strategies to leverage its therapeutic potential.

Outstanding Questions.

What are the molecular mechanisms that govern the trafficking itineraries of macropinosomes, and as a consequence, the fate of internalized cargoes?

Is there molecular and/or functional cross talk between macropinocytosis and autophagy?

What determines the relative utilization and anabolic benefits of different macropinocytic cargoes?

What genetic and pharmacological tools can be developed to improve in vivo studies of macropinocytosis?

Does macropinocytosis support cell fitness through functions other than nutrient supply, such as regulation of plasma membrane lipid and protein composition and distribution?

Highlights.

By delivering vital metabolic substrates to cancer cells, macropinocytosis presents an attractive and targetable vulnerability in tumors.

Macropinocytosis facilitates the uptake of a wide assortment of extracellular macromolecules and metabolites, in addition to protein.

Emerging evidence illustrates that many different tumor types engage in macropinocytosis through multiple oncogenic drivers.

The delivery of therapeutic agents via macropinocytosis offers an alternative approach for selective targeting of tumor cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute Grant CA210263 (D.B.S). J.P. was supported by a fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) CJ Martin Biomedical Fellowship (APP1106545). M.B. was supported by a fellowship from NIH/NCI (T32CA009161). The authors apologize to any colleagues whose work could not be cited due to space restrictions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lewis WH (1931) Pinocytosis. Bull. Johns Hopkins Hosp 49, 17–27 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simanshu DK, et al. (2017) RAS Proteins and Their Regulators in Human Disease. Cell 170, 17–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bar-Sagi D and Feramisco JR (1986) Induction of membrane ruffling and fluid-phase pinocytosis in quiescent fibroblasts by ras proteins. Science 233, 1061–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeBerardinis RJ and Chandel NS (2016) Fundamentals of cancer metabolism. Sci Adv 2, e1600200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Commisso C, et al. (2013) Macropinocytosis of protein is an amino acid supply route in Ras-transformed cells. Nature 497, 633–637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thottacherry JJ, et al. (2019) Spoiled for Choice: Diverse Endocytic Pathways Function at the Cell Surface. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 35, 55–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palm W, et al. (2015) The Utilization of Extracellular Proteins as Nutrients Is Suppressed by mTORC1. Cell 162, 259–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamphorst JJ, et al. (2015) Human pancreatic cancer tumors are nutrient poor and tumor cells actively scavenge extracellular protein. Cancer Res 75, 544–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davidson SM, et al. (2017) Direct evidence for cancer-cell-autonomous extracellular protein catabolism in pancreatic tumors. Nat Med 23, 235–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toh WH, et al. (2019) FcRn mediates fast recycling of endocytosed albumin and IgG from early macropinosomes in primary macrophages. J Cell Sci 133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaudhury C, et al. (2003) The major histocompatibility complex-related Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn) binds albumin and prolongs its lifespan. J Exp Med 197, 315–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swiercz R, et al. (2017) Loss of expression of the recycling receptor, FcRn, promotes tumor cell growth by increasing albumin consumption. Oncotarget 8, 3528–3541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsen MT, et al. (2020) FcRn overexpression in human cancer drives albumin recycling and cell growth; a mechanistic basis for exploitation in targeted albumin-drug designs. J Control Release 322, 53–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valkenburg KC, et al. (2018) Targeting the tumour stroma to improve cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 15, 366–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olivares O, et al. (2017) Collagen-derived proline promotes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell survival under nutrient limited conditions. Nat Commun 8, 16031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SM, et al. (2018) PTEN Deficiency and AMPK Activation Promote Nutrient Scavenging and Anabolism in Prostate Cancer Cells. Cancer Discov 8, 866–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jayashankar V and Edinger AL (2020) Macropinocytosis confers resistance to therapies targeting cancer anabolism. Nat Commun 11, 1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aubert L, et al. (2020) Copper bioavailability is a KRAS-specific vulnerability in colorectal cancer. Nat Commun 11, 3701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshida S, et al. (2015) Growth factor signaling to mTORC1 by amino acid-laden macropinosomes. J Cell Biol 211, 159–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao Y, et al. (2019) Extracellular and macropinocytosis internalized ATP work together to induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition and other early metastatic activities in lung cancer. Cancer Cell Int 19, 254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charpentier JC, et al. (2020) Macropinocytosis drives T cell growth by sustaining the activation of mTORC1. Nat Commun 11, 180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qian Y, et al. (2014) Extracellular ATP is internalized by macropinocytosis and induces intracellular ATP increase and drug resistance in cancer cells. Cancer Lett 351, 242–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pellegatti P, et al. (2008) Increased level of extracellular ATP at tumor sites: in vivo imaging with plasma membrane luciferase. PLoS One 3, e2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SW, et al. (2019) EGFR-Pak Signaling Selectively Regulates Glutamine Deprivation-Induced Macropinocytosis. Dev Cell 50, 381–392 e385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, et al. (2021) Macropinocytosis in Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts is Dependent on CaMKK2/ARHGEF2 Signaling and Functions to Support Tumor and Stromal Cell Fitness. Cancer Discov 11, 1808–1825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizushima N and Levine B (2020) Autophagy in Human Diseases. N Engl J Med 383, 1564–1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su H, et al. (2021) Cancer cells escape autophagy inhibition via NRF2-induced macropinocytosis. Cancer Cell 39, 678–693 e611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ridley AJ, et al. (1992) The small GTP-binding protein rac regulates growth factor-induced membrane ruffling. Cell 70, 401–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramirez C, et al. (2019) Plasma membrane V-ATPase controls oncogenic RAS-induced macropinocytosis. Nature 576, 477–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grimmer S, et al. (2002) Membrane ruffling and macropinocytosis in A431 cells require cholesterol. J Cell Sci 115, 2953–2962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yao W, et al. (2019) Syndecan 1 is a critical mediator of macropinocytosis in pancreatic cancer. Nature 568, 410–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoxhaj G and Manning BD (2020) The PI3K-AKT network at the interface of oncogenic signalling and cancer metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer 20, 74–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Welch HC, et al. (2002) P-Rex1, a PtdIns(3,4,5)P3- and Gbetagamma-regulated guanine-nucleotide exchange factor for Rac. Cell 108, 809–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shinohara M, et al. (2002) SWAP-70 is a guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor that mediates signalling of membrane ruffling. Nature 416, 759–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soisson SM, et al. (1998) Crystal structure of the Dbl and pleckstrin homology domains from the human Son of sevenless protein. Cell 95, 259–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han J, et al. (1998) Role of substrates and products of PI 3-kinase in regulating activation of Rac-related guanosine triphosphatases by Vav. Science 279, 558–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nimnual AS, et al. (1998) Coupling of Ras and Rac guanosine triphosphatases through the Ras exchanger Sos. Science 279, 560–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fleming IN, et al. (2000) Regulation of the Rac1-specific exchange factor Tiam1 involves both phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent and -independent components. Biochem J 351, 173–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Das B, et al. (2000) Control of intramolecular interactions between the pleckstrin homology and Dbl homology domains of Vav and Sos1 regulates Rac binding. J Biol Chem 275, 15074–15081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stam JC, et al. (1997) Targeting of Tiam1 to the plasma membrane requires the cooperative function of the N-terminal pleckstrin homology domain and an adjacent protein interaction domain. J Biol Chem 272, 28447–28454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshida S, et al. (2009) Sequential signaling in plasma-membrane domains during macropinosome formation in macrophages. J Cell Sci 122, 3250–3261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshida S, et al. (2015) Differential signaling during macropinocytosis in response to M-CSF and PMA in macrophages. Front Physiol 6, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amyere M, et al. (2000) Constitutive macropinocytosis in oncogene-transformed fibroblasts depends on sequential permanent activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase and phospholipase C. Mol Biol Cell 11, 3453–3467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodriguez-Viciana P, et al. (1997) Role of phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase in cell transformation and control of the actin cytoskeleton by Ras. Cell 89, 457–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mense SM, et al. (2015) PTEN inhibits PREX2-catalyzed activation of RAC1 to restrain tumor cell invasion. Sci Signal 8, ra32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hobbs GA, et al. (2020) Atypical KRAS(G12R) Mutant Is Impaired in PI3K Signaling and Macropinocytosis in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov 10, 104–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.King B, et al. (2020) Yap/Taz promote the scavenging of extracellular nutrients through macropinocytosis. Genes Dev 34, 1345–1358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kapoor A, et al. (2014) Yap1 Activation Enables Bypass of Oncogenic Kras Addiction in Pancreatic Cancer. Cell 158, 185–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhan T, et al. (2017) Wnt signaling in cancer. Oncogene 36, 1461–1473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Angers S and Moon RT (2009) Proximal events in Wnt signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10, 468–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clevers H and Nusse R (2012) Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell 149, 1192–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Albrecht LV, et al. (2020) GSK3 Inhibits Macropinocytosis and Lysosomal Activity through the Wnt Destruction Complex Machinery. Cell Rep 32, 107973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tejeda-Munoz N, et al. (2019) Wnt canonical pathway activates macropinocytosis and lysosomal degradation of extracellular proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 10402–10411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Redelman-Sidi G, et al. (2018) The Canonical Wnt Pathway Drives Macropinocytosis in Cancer. Cancer Res 78, 4658–4670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malliri A, et al. (2006) The rac activator Tiam1 is a Wnt-responsive gene that modifies intestinal tumor development. J Biol Chem 281, 543–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vander Heiden MG and DeBerardinis RJ (2017) Understanding the Intersections between Metabolism and Cancer Biology. Cell 168, 657–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.West MA, et al. (1989) Distinct endocytotic pathways in epidermal growth factor-stimulated human carcinoma A431 cells. J Cell Biol 109, 2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Masereel B, et al. (2003) An overview of inhibitors of Na(+)/H(+) exchanger. Eur J Med Chem 38, 547–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koivusalo M, et al. (2010) Amiloride inhibits macropinocytosis by lowering submembranous pH and preventing Rac1 and Cdc42 signaling. J Cell Biol 188, 547–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lonial S, et al. (2016) Monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of multiple myeloma: current status and future perspectives. Leukemia 30, 526–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Turski ML, et al. (2012) A novel role for copper in Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. Mol Cell Biol 32, 1284–1295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gerweck LE, et al. (2006) Tumor pH controls the in vivo efficacy of weak acid and base chemotherapeutics. Mol Cancer Ther 5, 1275–1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Navya PN, et al. (2019) Current trends and challenges in cancer management and therapy using designer nanomaterials. Nano Converg 6, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levitt DG and Levitt MD (2016) Human serum albumin homeostasis: a new look at the roles of synthesis, catabolism, renal and gastrointestinal excretion, and the clinical value of serum albumin measurements. Int J Gen Med 9, 229–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kratz F (2008) Albumin as a drug carrier: design of prodrugs, drug conjugates and nanoparticles. J Control Release 132, 171–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu X and Ghosh D (2019) Intracellular nanoparticle delivery by oncogenic KRAS-mediated macropinocytosis. Int J Nanomedicine 14, 6589–6600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li R, et al. (2021) Therapeutically reprogrammed nutrient signalling enhances nanoparticulate albumin bound drug uptake and efficacy in KRAS-mutant cancer. Nat Nanotechnol 16, 830–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Desai AS, et al. (2019) Using macropinocytosis for intracellular delivery of therapeutic nucleic acids to tumour cells. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 374, 20180156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Walsh M, et al. (2006) Evaluation of cellular uptake and gene transfer efficiency of pegylated poly-L-lysine compacted DNA: implications for cancer gene therapy. Mol Pharm 3, 644–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yoo DY, et al. (2020) Macropinocytosis as a Key Determinant of Peptidomimetic Uptake in Cancer Cells. J Am Chem Soc 142, 14461–14471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Redelman-Sidi G, et al. (2013) Oncogenic activation of Pak1-dependent pathway of macropinocytosis determines BCG entry into bladder cancer cells. Cancer Res 73, 1156–1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Overmeyer JH, et al. (2011) A chalcone-related small molecule that induces methuosis, a novel form of non-apoptotic cell death, in glioblastoma cells. Mol Cancer 10, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li C, et al. (2010) Nerve growth factor activation of the TrkA receptor induces cell death, by macropinocytosis, in medulloblastoma Daoy cells. J Neurochem 112, 882–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Overmeyer JH, et al. (2008) Active ras triggers death in glioblastoma cells through hyperstimulation of macropinocytosis. Mol Cancer Res 6, 965–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Srivastava RK, et al. (2019) Combined mTORC1/mTORC2 inhibition blocks growth and induces catastrophic macropinocytosis in cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 24583–24592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maltese WA and Overmeyer JH (2015) Non-apoptotic cell death associated with perturbations of macropinocytosis. Front Physiol 6, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Maltese WA and Overmeyer JH (2014) Methuosis: nonapoptotic cell death associated with vacuolization of macropinosome and endosome compartments. Am J Pathol 184, 1630–1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sarkar Bhattacharya S, et al. (2019) PFKFB3 inhibition reprograms malignant pleural mesothelioma to nutrient stress-induced macropinocytosis and ER stress as independent binary adaptive responses. Cell Death Dis 10, 725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cho H, et al. (2018) Indolyl-Pyridinyl-Propenone-Induced Methuosis through the Inhibition of PIKFYVE. ACS Omega 3, 6097–6103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Song S, et al. (2020) The Dual Role of Macropinocytosis in Cancers: Promoting Growth and Inducing Methuosis to Participate in Anticancer Therapies as Targets. Front Oncol 10, 570108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Swanson JA (2008) Shaping cups into phagosomes and macropinosomes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9, 639–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Buckley CM and King JS (2017) Drinking problems: mechanisms of macropinosome formation and maturation. FEBS J 284, 3778–3790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Freeman SA, et al. (2020) Lipid-gated monovalent ion fluxes regulate endocytic traffic and support immune surveillance. Science 367, 301–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kerr MC, et al. (2006) Visualisation of macropinosome maturation by the recruitment of sorting nexins. J Cell Sci 119, 3967–3980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang JT, et al. (2010) The SNX-PX-BAR family in macropinocytosis: the regulation of macropinosome formation by SNX-PX-BAR proteins. PLoS One 5, e13763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Donaldson JG (2019) Macropinosome formation, maturation and membrane recycling: lessons from clathrin-independent endosomal membrane systems. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 374, 20180148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]