Abstract

The recent outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has rampaged the world with more than 236 million confirmed cases and over 4.8 million deaths across the world reported by the world health organization (WHO) till Oct 5, 2021. Due to the advent of different variants of coronavirus, there is an urgent need to identify effective drugs and vaccines to combat rapidly spreading virus varieties across the globe. Ferrocene derivatives have attained immense interest as anticancer, antifungal, antibacterial, and antiparasitic drug candidates. However, the ability of ferrocene as anti-COVID-19 is not yet explored. Therefore, in the present work, we have synthesized four new ferrocene Schiff bases (L1-L4) to understand the active sites and biological activity of ferrocene derivatives by employing various molecular descriptors, frontier molecular orbitals (FMO), electron affinity, ionization potential, and molecular electrostatic potential (MEP). A theoretical insight on synthesized ferrocene Schiff bases was accomplished by molecular docking, frontier molecular orbitals energies, active sites, and molecular descriptors which were further compared with drugs being currently used against COVID-19, i.e., dexamethasone, hydroxychloroquine, favipiravir (FPV), and remdesivir (RDV). Moreover, through the molecular docking approach, we recorded the inhibitions of ferrocene derivatives on core protease (6LU7) protein of SARS-CoV-2 and the effect of substituents on the anti-COVID activity of these synthesized compounds. The computational outcome indicated that L1 has a powerful 6LU7 inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 compared to the currently used drugs. These results could be helpful to design new ferrocene compounds and explore their potential application in the prevention and treatment of SARS-CoV-2.

Keywords: Ferrocene derivatives, Anti-COVID19, Molecular docking, Molecular descriptors

1. Introduction

The outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Wuhan city of China in December 2019 was renamed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2) by the international committee on taxonomy [1]. Due to its rapid human-to-human transmission, the world health organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as a pandemic on 12 March 2020 [2]. According to WHO, SARS-CoV2 has rampaged the world with more than 236 million confirmed cases and over 4.8 million deaths across the world till Oct 5, 2021. In last week, the highest numbers of new cases were reported due to new variant of virus in India (70%) [3]. Public health has been affected the most because people do not have the opportunities to access a modern health system and medicine in developing countries of Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean [4,5]. Due to different variants of the coronavirus, there is an urgent need to identify effective drugs and vaccines to combat rapidly spreading virus varieties across the globe [6].

Ferrocene derivatives have attained immense interest as anticancer, antifungal, antibacterial, and antiparasitic drug candidates [7]. Ferrocene was used for the treatment of anemia in the former USSR because of its low toxicity [8]. The lipophilicity of ferrocenyl groups allows ferrocene, to be administered orally for the treatment of gum diseases which is not the case for simple Fe(II) salts [9]. Furthermore, the activity of ferrocene compounds towards cancer was first investigated in 1978. This early work involved the synthesis of new compounds bearing an antigen that binds strongly to nucleic acids [10]. A ferrocenyl group was chosen as the antigenic moiety, which demonstrated that ferrocenyl polypeptides elicit a strong antigenic response [11]. Thus the ferrocene-based drugs have a marked effect on molecular properties e.g. redox activation and lipophilicity. Moreover, ferrocene compounds containing alcohol substituents have proved to be versatile precursors for effective anticancer and antimalarial agents [12], [13], [14].

In the present work, we have synthesized ferrocene derivatives (L1-L4) and characterized them by NMR spectroscopy and Mass spectrometry. The compound L4 was further characterised by single-crystal diffraction. Moreover, we have demonstrated the inhibition impact of ferrocene derivatives over SARS-CoV-2, providing an essential base for the resistance of ferrocene compounds against prime protease (6LU7) proteins of SARS-CoV-2 through docking simulations. We further highlighted the molecular descriptors, ionization potential (IP), frontier molecular orbitals (FMO), electron affinity (EA), and molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) analysis to explore the biological and pharmacological activities. The electronic characteristics along with global reactivity descriptors including electrophilicity index (ω), electronegativity (χ), chemical potential (µ), softness (S) as well as chemical hardness (η) were carried out to understand the active sites of ferrocene derivatives. The outcome of the work demonstrated that the synthesized ferrocene derivatives have an appreciable ability to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 invasion within the human body.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Ferrocenecarboxaldehyde, 2-amino-4-chlorophenol, 2-amino-4-phenylphenol, 2-amino-4-nitrophenol, and 2-amino-4-sulfonylphenol were purchased from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium). All chemicals and solvents were of analytical grade and used as received. All reactions were carried out under aerobic conditions.

2.2. Instrumentation

The elemental analysis (C H N) was performed using an Elementar Vario EL analyzer. Fourier transform IR spectra were measured on a Perkin–Elmer Spectrum One spectrometer with samples prepared as KBr discs. UV–Vis absorption spectroscopy of synthesized samples was carried out by Varian Cary 500 Scan UV–VIS NIR Spectrophotometer. Solution NMR spectra were recorded with Bruker Avance instruments operating at 1H Larmor frequencies of 400 MHz, using DMSO‑d 6 as solvent and TMS as an internal standard for 13C and 1H nuclei.

2.3. X-ray crystallography

A single crystal of the L4 with dimensions of 0.24 × 0.2 × 0.03 mm was mounted in a glass capillary and data were collected on a Stoe StadiVari diffractometer. Intensity data were collected with graphite monochromated Ga Ka radiation (λ = 1.34143 nm) at 150 K. The structure was solved by direct methods using SHELXLS-2015 and refined against F2 by full matrix least squares using SHELXL-2015 [15]. A summary of pertinent crystal data, experimental details and refinement results are shown in Table 1 . Crystallographic data for complex have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, CCDC No. 2,081,830. Copies may be obtained free of charge from www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/conts/retrieving.html or from the CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge, CB2 1EZ, UK (email: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk).

Table 1.

Crystal data and refinement parameters of L4.

| Empirical formula | C17H14ClFeNO |

|---|---|

| Formula weight | 339.59 |

| Temperature/K | 150 |

| Crystal system | monoclinic |

| Space group | P21/n |

| a/Å | 13.1760(7) |

| b/Å | 17.2007(9) |

| c/Å | 13.4953(8) |

| α/° | 90 |

| β/° | 109.467(4) |

| γ/° | 90 |

| Volume/Å3 | 2883.7(3) |

| Z | 8 |

| ρcalcg/cm3 | 1.564 |

| μ/mm-1 | 6.752 |

| F(000) | 1392.0 |

| Crystal size/mm3 | 0.24 × 0.2 × 0.03 |

| Radiation | GaKα (λ = 1.34143) |

| 2Θ range for data collection/° | 7.066 to 128.536 |

| Index ranges | −17 ≤ h ≤ 15, -16 ≤ k ≤ 22, -17 ≤ l ≤ 14 |

| Reflections collected | 22,138 |

| Independent reflections | 7034 [Rint = 0.0555, Rsigma = 0.0923] |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 7034/0/381 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 0.924 |

| Final R indexes [I>=2σ (I)] | R1 = 0.0547, wR2 = 0.1271 |

| Final R indexes [all data] | R1 = 0.1183, wR2 = 0.1491 |

| Largest diff. peak/hole / e Å−3 | 0.57/−0.65 |

2.4. Synthesis of ferrocene derivatives

2.4.1. Synthesis of N-(2‑hydroxy-5-biphenyl) ferrocylideneamine (L1)

Ferrocencarboxaldehyde (1.07 g, 5 mmol) and 2-amino-4-phenylphenol (0.927 g, 5 mmol) were dissolved in 20 mL of ethanol (absolute) and the mixture was refluxed for 3 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and left overnight to afford brown precipitates. The product was further purified by recrystallization in dichloromethane. FT-IR (KBr cm−1) 3166, 3075 and 2969 (C–H str), 1596.34 (C = N str), 1101.60, 1080.43 (Ar–CH), 468.17, 488.77 cm−1 (Cp C–H). UV–Vis (CHCl3) λmax 238, 261, 358, and 460 nm. 1H NMR (DMSO‑d 6, 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 4.32 (s, 5H, Fc-unsubstituted ring), 4.69 (s, 2H, H-3, H-4, Fc-substituted ring), 4.82 (s, 2H, H-2, H-5, Fc-substituted ring), 6.45 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 6.54 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 6.70 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 6.89 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 7.24 (m, 1H, Ar-H), 7.37 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 7.50 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 8.49 (s, 1H, CH N), 9.31 (bs, 1H, Ar-OH).

13C NMR (DMSO‑d 6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 69.88 (C-2, C-5, Fc-substituted ring), 69.91 (C-5, Fc-unsubstituted ring), 73.53 (C-3, C-4, Fc-substituted ring), 80.02 (C-1, Fc-substituted ring), 112.96 (Ar-CH), 115.30 (Ar-CH), 122.62 (Ar-CH), 126.33 (Ar-C-Cl), 129.10 (Ar-CH), 130.89 (Ar-CH), 132.62 (Ar-CH), 133.21 (Ar-CH), 135.17 (Ar-CH), 138.97 (Ar-C-N), 148.57 (Ar-C-OH), 165.93 (CH N).

MS (EI) m/z: 381.09 (78.45%), 316.04 (47.55%), 289.04 (21.89%), 215.00 (66.72%), 214.00 (97.49%), 186.01 (100%), 170.06 (65.82%), 120.96 (96.71%).

2.4.2. Synthesis of N-(2‑hydroxy-5-nitrophenyl) ferrocylideneamine (L2)

2-amino-4-phenylphenol is replaced with 2-amino-4-nirophenol in the procedure given in 2.3.1. FT-IR (KBr cm−1) 3068 and 3023 (C–H str), 1592.88 (C = N str) 1104.97, 1073.68 (Ar–CH) 471.18, 493.18 cm−1 (Cp C–H). UV–Vis (CHCl3) λ max 237, 256, 299, 323 and 484 nm.

1H NMR (DMSO‑d 6, 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 4.30 (s, 5H, Fc-unsubstituted ring), 4.68 (s, 2H, H-3, H-4, Fc-substituted ring), 4.91 (s, 2H, H-2, H-5, Fc-substituted ring), 6.75 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.46 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 8.59 (s, 1H, CH N), 9.36 (bs, 1H, Ar-OH).

13C NMR (DMSO‑d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 69.77 (C-2, Fc-substituted ring), 69.87 (C-5, Fc-substituted ring), 69.90 (C-5, Fc-unsubstituted ring), 73.52 (C-3, C-4, Fc-substituted ring), 79.88 (C-1, Fc-substituted ring), 108.11 (Ar-CH), 113.51 (Ar-CH), 113.58 (Ar-CH), 136.06 (Ar-C-NO2), 140.04 (Ar-C-N), 151.13 (Ar-C-OH), 166.85 (CH N).

MS (EI) m/z: 351.06 (74.10%), 350.06 (100.00%), 348.05 (46.00%), 320.07 (34.91%), 285.00 (37.80%), 186.011 (56.12%), 120.96 (61.90%).

2.4.3. Synthesis of N-(2‑hydroxy-5-sulfonylphenyl) ferrocylideneamine (L3)

2-amino-4-phenylphenol is replaced with 2-amino-4-sulfonylphenol in the procedure given in 2.3.1. FT-IR (KBr cm−1) 3380 and 3094 (C–H str), 1639 (C = N str) 1102, 1071 (Ar–CH) 461, 566 cm−1 (Cp C–H). UV–Vis (CHCl3) λ max 237, 268, 337 and 451 nm.

1H NMR (DMSO‑d 6, 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 4.29 (s, 5H, Fc-unsubstituted ring), 4.47 (s, 2H, H-3, H-4, Fc-substituted ring), 4.67–480 (m, 2H, H-2, H-5, Fc-substituted ring), 6.88 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.40 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.53 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 8.61 (s, 1H, CH N), 9.34 (bs, 1H, Ar-OH).

13C NMR (DMSO‑d 6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 69.87 (C-2, Fc-substituted ring), 69.91 (C-5, Fc-substituted ring), 73.53 (C-5, Fc-unsubstituted ring), 73.61 (C-3, C-4, Fc-substituted ring), 79.87 (C-1, Fc-substituted ring), 115.43 (Ar-CH), 116.51 (Ar-CH), 119.21 (Ar-CH), 120.31 (Ar-CH), 140.8 (Ar-C-SO3H), 141.02 (Ar-C-N), 150.06 (Ar-C-OH), 163.83 (CH N).

MS (EI) m/z: 382.06 (35.13%), 322.66 (39.91%), 291.04 (41.81%), 213.95 (74.60%), 185.96 (57.57%), 120.94 (100%).

2.4.4. Synthesis of N-(2‑hydroxy-5-chlorophenyl) ferrocylideneamine (L4)

2-amino-4-phenylphenol is replaced with 2-amino-4-cholorophenol in the procedure given in 2.3.1. The characterization of the compound has been reported previously [16].

2.5. Computational details

In biological systems, the density functional theory (DFT) is a fascinating method to analyze numerous important properties [17], [18], [19], [20]. The DFT analysis has a significant contribution to the investigation of electronic characteristics of molecules [21], [22], [23], [24], [25] as well as optimize geometries within the ground state (S0) [26,27]. B3LYP is a coherent functional for the S0 geometries of numerous biologically active molecules. In current investigations regarding S0 geometries optimizations as well as electronic characteristics, we adopted B3LYP/6–31G**(LANL2DZ) within Gaussian16 software [28]. Furthermore, Autodock version 4.2 was endorsed through Autodock MGL tools for docking by employing the strategy of eliminating H2O followed by the addition of more polar hydrogen moiety. Autodock 4.2, the Autogrid resolute the native ligand location around the binding site by organizing the grid coordinates (X, Y, and Z-axis). The docking computations were executed with Autodock 4.2 along with Pymol version 1.7.4.5 Edu.

3. Results and discussion

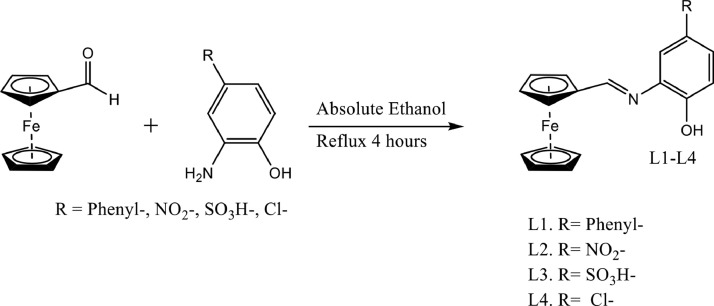

3.1. Synthesis of ferrocene derivatives (L1-L4)

Three new aromatic substituted ferrocene derivatives were synthesized (L1-L4) in a good yield by reacting an equimolar amount of the phenyl-, nitro, sulfonyl- and L4 with chloro‑ substituted aminophenol (0.5 mmol) and ferrocenecarboxaldehyde (0.5 mmol) using ethanol as a solvent as shown in Scheme. 1. The structure and composition of the ferrocene compounds were confirmed by 1HNMR, mass spectrometry, FT-IR and UV–Vis spectroscopy. The structure of compound L4 was also characterized by single-crystal x-ray diffraction.

Scheme 1.

Ferrocene Schiff base derivatives studied in the current work.

FT-IR spectra of L1-L4 were recorded in the frequency range of 4000–400 cm−1 which showed all expected characteristic peaks. Imine function (C = N sp2 stretching bands) of all compounds appeared as strong signals at 1596 (L1), 1592 (L2), 1639 (L3), and 1582 (L4) in the IR spectra.

The bands at 3100–2800 cm−1 can be attributed to aromatic ν(C − H). Band at 1101, 1080 cm−1 (L1), 1104, 1073cm−1 (L2), 1102, 1071 (L3) and 1105, 1084 cm−1 (L4) are observed for ferrocene moiety. A Cp ν(C–H) stretching vibration can be seen at 468, 488 cm−1 (L1), 471, 493.cm−1 (L2), 461, 566 cm−1(L3) and 471, 497 cm−1 (L4).

The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra of synthesized compounds (L1-L4) were recorded in DMSO‑d 6 at room temperature. In all the 1H NMR spectra of L1-L3, the characteristic singlet of the azomethine (CH N) proton that confirmed the formation of Schiff base has appeared at 8.49, 8.59, and 8.61 ppm respectively. Protons of the unsubstituted cyclopentadienyl ring η5‐C5H5 of L1-L3 has appeared at 4.32, 4.30, and 4.29 ppm respectively. The signals of the substituted cyclopentadienyl ring η4‐C5H4 were observed at 4.69 and 4.82 ppm in L1, 4.68 and 4.91 ppm in L2, and 4.47 and 4.80 ppm in case of L3. The signals of aromatic protons of L1 was seen as four singlets at 6.45, 6.54, 6.70, and 6.89 ppm whereas three multiplets for aromatic protons appeared at 7.24, 7.37 and 7.50 ppm. In the case of ligand L2, two doublets with coupling constant of 8.5 Hz were observed at 6.75, 7.37 ppm, and a singlet of one proton was recorded at 7.46 ppm. Protons of ligands L3 were seen as two doublets that appeared at 6.88 and 7.40 ppm with a coupling constant of 8.6 Hz and a singlet at 7.53 ppm. The broad singlets for the phenolic OH group proton in L1-L3 are at 9.31, 9.36 and 9.34 ppm respectively.

The 13C NMR spectrum of L1-L3 displayed signals for C-2 and C-5 at 69.88, 69.87, and 69.91 and 73.53, 73.52 and 73.61 ppm for C-3 and C-4 for substituted cyclopentadienyl ring η4‐C5H4. The signals at 69.91, 69.90, and 73.53 ppm were assigned for the unsubstituted cyclopentadienyl ring η5‐C5H5, whereas signals at 80.02, 79.88, and 79.87 ppm were assigned for C-1 of the substituted cyclopentadienyl ring η4‐C5H5 of L1-L3 respectively. In 13C NMR spectra of L1-L3, the signals appeared at 165.93, 166.85 and 163.83 ppm were assigned to C N respectively. The signals of the phenyl groups were found in the expected regions at 108.11 to 141.02. The signals of aromatic carbons of L1-L3 bearing OH groups were resonating at 148.57, 151.13, and 150.06 ppm respectively.

The ligands L1-L3 were further confirmed by mass spectrometry. The m/z ratios of the compounds L1-L3 measured are 381.09, 351.06, and 382.06 respectively which are in complete agreement with the theoretical structural formula of the Schiff bases.

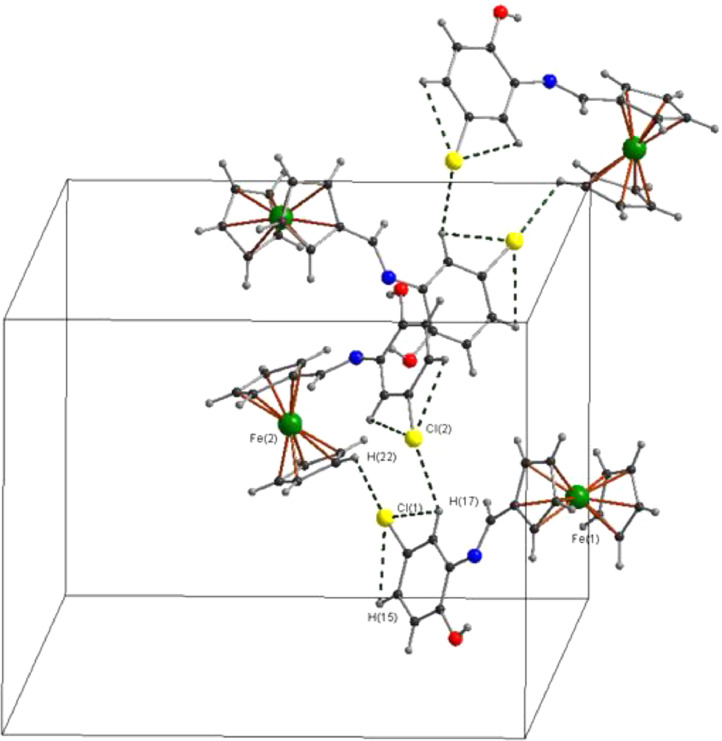

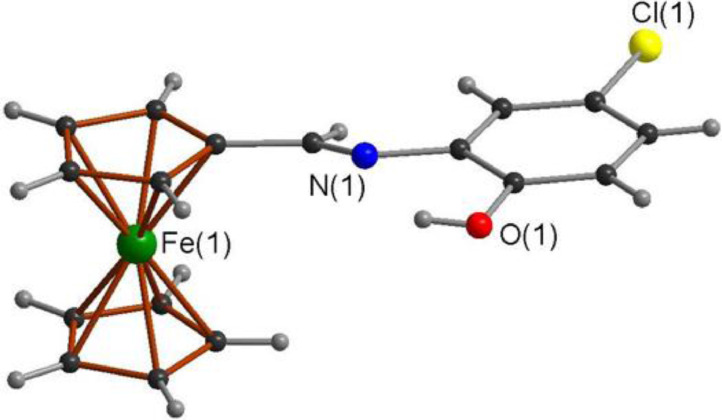

3.2. Crystal structure of L4

The structure of L4 was confirmed using single‐crystal X‐ray crystallography. The structure and labeling scheme is depicted in Fig. 1 . Selected bond lengths and angles are presented in Table 2 . L4 crystallized in the centrosymmetric P21/n space group. The —C N— bond length (1.275(6) Å) is consistent with the values reported for related ferrocene Schiff bases of general formula [(η5 ‐C2H5) Fe (η5‐C2H5CH N—C6H4(OH)] and [(η5‐C2H5) Fe (η5-C2H5C(R) N(C6H4–2‐OH)] (R = Me, C6H5) [29]. The other bond lengths and angles of the ferrocenyl moiety agree with those reported for most ferrocene derivatives [30] The value of the torsion angle C(6)–C(11)–N(1)–C(12) (177.2°) indicates that the imine adopts the anti‐(E) form which is good agreement with known Schiff bases derived from ferrocene [31]. Also, the advantage of the anti‐(E) form is to retain the co‐planarity between the donor and acceptor group which is important for the charge transfer process [32].

Fig. 2.

Compound L4 showing the formation of dimer C—H···Cl interactions.

Fig. 1.

Molecular structure of ferrocenyl schiff base (L4).

Table 2.

Selected bond distances and bond angles of L4.

| Bond length (Å) | Bond angles(°) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| C(6)-C(11) | 1.438(5) | C(6)-C(11)-N(1) | 123.8(4) |

| C(11)-N(1) | 1.275(5) | C(11)-N(1)-C(12) | 120.0(3) |

| C(12)-N(1) | 1.425(5) | N(1)-C(12)-C(17) | 124.8(3) |

| C(16)-Cl(1) | 1.731(5) | N(1)-C(12)-C(13) | 116.8(3) |

| C(13)-O(1) | 1.356(5) | O(1)-C(13)-C(12) | 122.7(3) |

| Fe-Ca | 1.382(6) | Cl(1)-C(16)-C(15) | 119.4(4) |

| C-Ca | 1.382(6) | Cl(1)-C(16)-C(17) | 119.7(3) |

3.3. Electronic properties

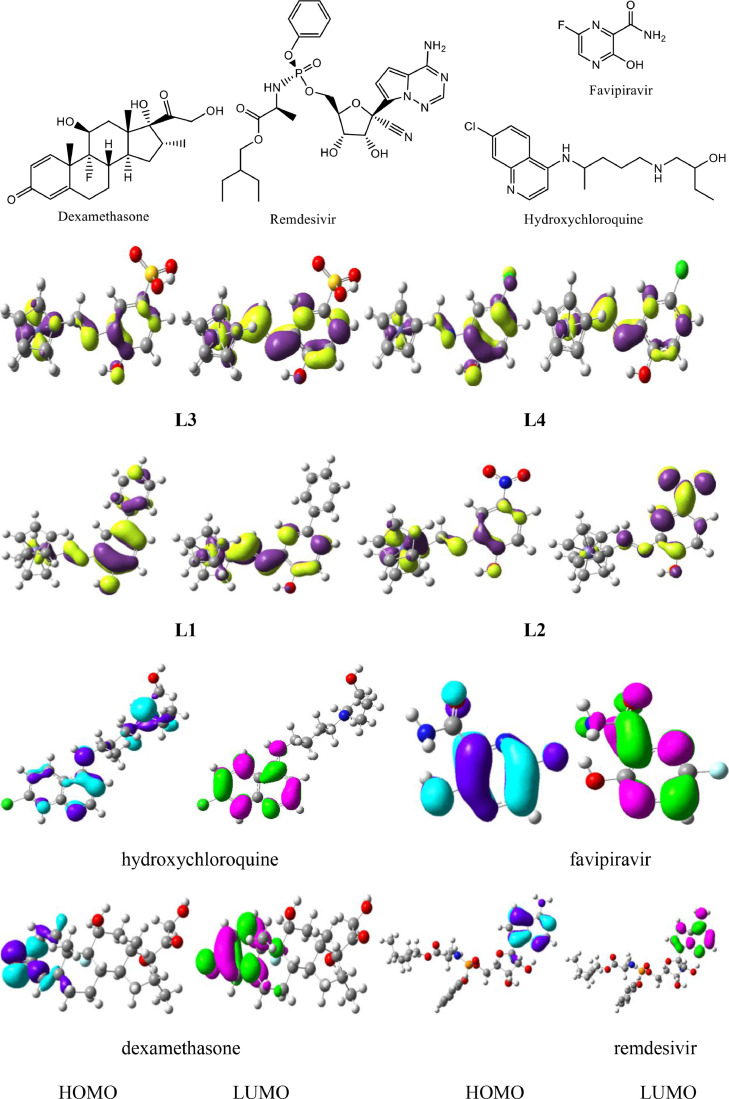

The highest occupied / lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (HOMOs / LUMOs) of studied compounds were probed at B3LYP/6–31G**(LANL2DZ) level (Fig. 3 ) and the optimized structure of L4 is given in figure S2. The spatial scattering of HOMO within dexamethasone was observed at C = O whereas LUMO over side ring of phenanthrene. The intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) was found for keto C = O (HOMO) to the side ring of phenanthrenee (LUMO). In remdesivir, the HOMO was at pyrrolotriazin unit whereas the LUMO at [1,2,4] triazin-7-yl aminopyrrolo [2,1-f] revealing the ICT from HOMO to LUMO. In hydroxychloroquine, ICT was also found from HOMO at amino group of (ethyl)amino]ethanol unit) to LUMO (quinolin) and HOMO → LUMO. In favipiravir, HOMO is primarily at 6-fluoro-3-hydroxypyrazine as well as oxygen of carboxamide moiety while the LUMO is pyrazine-2-carboxamide illuminating ICT from HOMO to LUMO. Similarly, in the synthesized ferrocene derivatives ICT was noticed from HOMOs to LUMOs. The activity of compounds was also strictly associated with the spatial distribution of occupied molecular orbitals enlightening the most credible locations in order that certainly attacked by reactive agents. The FMOs were superimposed considerably thus revealing the particularly reactive nature of the drugs. The energies of FMOs, for example, HOMO (EHOMO), LUMO (ELUMO), as well as HOMO-LUMO energy gaps (Egap) were significant parameters to probe molecular electronic characteristics. The EHOMO, ELUMO, and Egap of recently synthesized ferrocene derivatives along with reference drugs dexamethasone, remdesivir, hydroxychloroquine, and favipiravir are displayed in Table 3 . The molecular structures of the reference drugs are given below.

Fig. 3.

Ground state charge density of FMOs of Ferrocene derivatives and reference drugs used against COVID (contour value=0.035).

Table 3.

The frontier molecular orbitals (EHOMO and ELUMO), energy gaps (Egap), various molecular descriptors, electron injection energy (EIE), and hole injection energy (HIE) barriers of ferrocene derivatives calculated at B3LYP/6–31G**(LANL2DZ) level.

| Parameters | L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | dexamethasone | remdesivir | hydroxyl-chloroquine | Favipiravir |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EHOMO | −5.33 | −5.89 | −5.83 | −5.58 | −6.22 | −6.20 | −5.57 | −6.98 |

| ELUMO | −1.56 | −2.08 | −1.90 | −1.73 | −1.39 | −1.36 | −1.14 | −2.24 |

| Egap | 3.77 | 3.81 | 3.93 | 3.85 | 4.83 | 4.84 | 4.43 | 4.74 |

| IP | 5.33 | 5.89 | 5.83 | 5.58 | 6.22 | 6.20 | 5.57 | 6.98 |

| EA | 1.56 | 2.08 | 1.90 | 1.73 | 1.39 | 1.36 | 1.14 | 2.24 |

| η | 1.885 | 1.905 | 1.965 | 1.925 | 2.41 | 2.42 | 2.21 | 2.37 |

| µ | −3.445 | −3.985 | −3.865 | −3.655 | −3.80 | −3.78 | −3.35 | −4.61 |

| S | 1.414 | 1.546 | 1.483 | 1.449 | 1.29 | 1.28 | 1.26 | 1.47 |

| χ | 3.445 | 3.985 | 3.865 | 3.655 | 3.80 | 3.78 | 3.35 | 4.61 |

| ω | 3.148 | 4.168 | 3.801 | 3.470 | 4.428 | 4.604 | 4.363 | 4.609 |

| HIE (Au) | 0.23 | 0.79 | 0.73 | 0.48 | 1.12 | 1.10 | 0.47 | 1.88 |

| EIE (Au) | 2.15 | 1.72 | 1.82 | 3.37 | 3.71 | 3.74 | 3.96 | 2.86 |

| HIE (Al) | 1.25 | 1.81 | 1.75 | 1.50 | 2.14 | 2.12 | 1.49 | 2.90 |

| EIE (Al) | 2.52 | 2.00 | 2.18 | 2.35 | 2.69 | 2.72 | 2.94 | 1.84 |

The measurements of global chemical reactivity descriptors (GCRD) are essential considerations to figure out the activity. Herein, the large number of GCRD parameters were estimated including the electrophilicity index (ω), softness (S), electronegativity (χ), chemical potential (µ) as well as chemical hardness (η) with the help of HOMO/LUMO energies.

An approximation for absolute hardness η was developed [33], [34], [35] as given below:

| (1) |

where I is the vertical ionization energy and A is vertical electron affinity.

As per Koopmans theorem [36] the ionization energy and electron affinity can be specified through HOMO and LUMO orbital energies as:

| (2) |

| (3) |

Values of EA and IP of calculated are given in Table 3. The higher energy of HOMO is corresponding to the more reactive molecule in the reactions with electrophiles, while lower LUMO energy is essential for molecular reactions with nucleophiles [37].

Hence, the hardness of any materials corresponds to the gap between the HOMO and LUMO orbitals. If the energy gap of HOMO-LUMO is large then the molecule becomes harder [35].

| (4) |

The electronic chemical potential () of a molecule is calculated by:

| (5) |

The softness of a molecule is calculated by:

| (6) |

The electronegativity of the molecule is calculated by:

| (7) |

The electrophilicity index of the molecule is calculated by:

| (8) |

The η is interconnected to aromaticity and the value of ω represents the stabilization energy for saturated compound by electrons from the exterior environment [38,39]. The value of μ conveys the electronic tendency to run away based on its electronic cloud whereas the η value provides a degree of hindrance of electronic cloud toward deformation. We have previously reported that the better radical scavenging ability of a drug was a prerequisite to hinder viral infections [40]. The antioxidant compounds contribute an electron to the free radical and the resulting radical cation should be stable enough to demonstrate better radical scavenging ability in a one-electron transfer mechanism. In this way, the antioxidant ability can be evaluated by ionization potential (IP) and the physical parameter highlighting the electron transfer range can be estimated by IP= -EHOMO. It is anticipated that radical scavenging nature might be superior for those compounds which show smaller IP. The results in Table 3 revealed that L1 have the smallest IP value therefore, it might be a better radical scavenger having good antioxidant ability as compared to the reference drugs (dexamethasone, remdesivir, hydroxychloroquine, and favipiravir).

The hole and electron injection energies (HIE and EIE) of these synthesized ferrocene derivatives were calculated and compared to Al and Au electrodes having work function (W) 4.08 and 5.10 eV respectively. The EIE of ferrocene derivatives were estimated as (eV = − ELUMO − (−W)) and HIE as (eV = − W − (−EHOMO)), see Table 3. The hole and electron injection barriers of ferrocene derivatives were found to be smaller than most of the reference drugs.

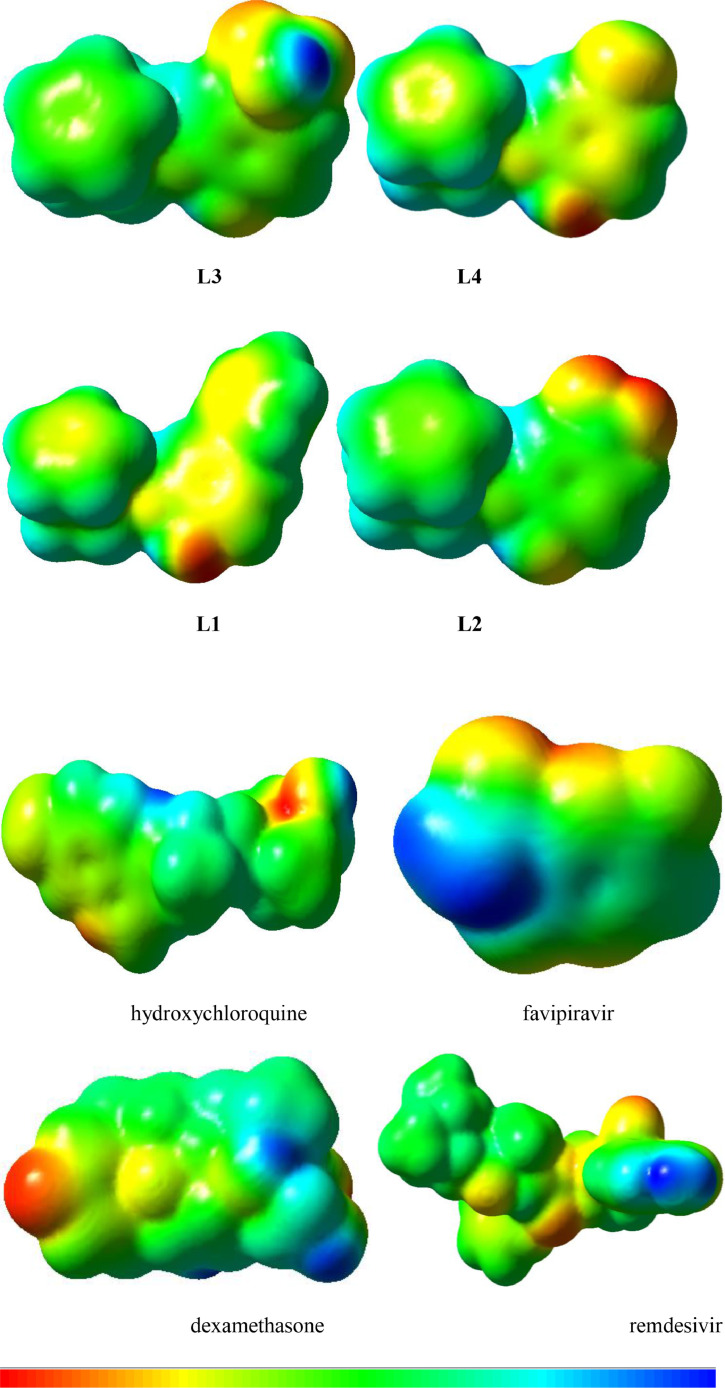

3.4. Molecular electrostatic potential

The molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) was measured experimentally by diffraction approaches and calculated computationally to explore the reactivity of various compounds and/or species [41,42]. The MEP is an important feature to understand the reactivity of various species [43]. The MEP mapped for ferrocene derivatives and reference drugs are illustrated in color visualizations in Fig. 3. The red color indicates the higher negative potential regions which are favorable for an electrophilic attack, whereas the blue color identifies the higher positive potential regions promising for nucleophilic attack. The MEP decreases in the order blue > green > yellow > orange > red. The maps of molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) were essential to visualize charged regions within the compounds. The MEP mapped with respect to ferrocene derivatives and reference drugs are shown in color displays in Fig. 4 . The red and blue color band identifies negative as well as positive potential areas that would be favorable for electrophilic as well as nucleophilic attack, respectively. In dexamethasone, the negative potential can be seen on O- atoms while positive potential is formed at the H atoms of hydroxyl groups. In remdesivir, negative potential can be seen on oxygen atoms while positive potential at hydrogen atoms of the amino group. In hydroxychloroquine, negative potential can be seen on the oxygen atom of quinolin and oxygen atom of ethanol group while positive potential at hydrogen atoms of hydroxyl and –NH. In favipiravir, negative potential can be seen on the oxygen atoms while positive potential at hydrogen atoms carboxamide moiety. The negative potential can be seen on the O- atom of -OH in L1, on the nitro group in L2, and oxygen atoms of –SO3H in L3. However, a positive potential is concentrated within hydrogen atoms. The negative potential (red region) on oxygen atoms indicated further the possible sites for the electrophilic attack. Whereas, blue color (positive potential) on hydrogen atoms revealed that these sites would be promising for nucleophilic attack.

Fig. 4.

Molecular electrostatic potential surfaces views of Ferrocene derivatives and reference drugs.

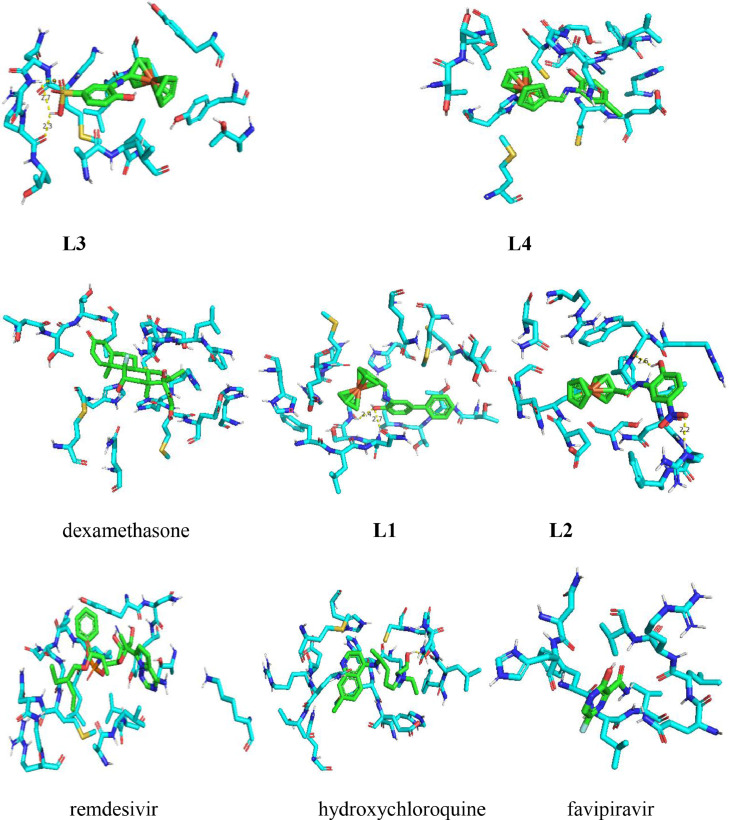

4. Molecular docking

The structure of the 6LU7 proteins of SARS-CoV-2 is deposited in the Worldwide Protein Data Bank. The virus core protease crystal structure in the complex (6LU7) without water molecules and inhibitor are shown in Fig. 5 . The 6LU7 protein structure was refined using Autodock and a model outlining the docking analysis of molecules along with standards drugs. The binding energy values between ligands and protein (active sites in the title compounds along with amino acids) are displayed in Table 4 and Fig. 5. The binding energy values between ligands and 6LU7 proteins of SARS-CoV-2 (active sites in the title compounds and 6LU7 proteins of the SARS-CoV-2) were given in Table 4 and Fig. 6 . In L1, the hydrogen bonding between H of ligand to O—H of CYS145 was found to be 2.40 Å, and H of GLY143 and O of ligand was 2.70 Å. Hydrogen bonding between keto O of TRP218 to H—O of ligand was found to be 2.60 Å and hydrogen bonding between H of ARG222 and O—N—O of ligand was found to be 2.20 Å in L2. In Compound L3, hydrogen bonding between keto O of ARG279 and HSO3 of ligand was found to be 2.70 Å, hydrogen bonding between keto O of GLY278 and HSO3 of ligand was found 2.30. The docking results for L1-L4 highlighted that the L1 might have better anti-oxidant and anti-COVID19 ability than other counterparts. The computation outcome indicates that L1 exhibit better inhibition against SARS-CoV-2 as compared to the reference drugs. This finding leads to further exploration of L1 and its potential application in the prevention and treatment of SARS-CoV-2.

Table 5.

Topological parameters of the title compounds for selected CPs.

| Compound | BCP | ρ(r) (a.u) |

∇2ρ(r) (a.u) |

V(r) (a.u) |

G (r) (a.u) |

H(r) (a.u) |

-G/V | ε |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | Fe1-C15 | 0.085 | 0.282 | −0.132 | 0.101 | −0.031 | 0.767 | 0.339 |

| Fe1-C20 | 0.084 | 0.272 | −0.127 | 0.097 | −0.029 | 0.768 | 0.349 | |

| Fe1-C18 | 0.085 | 0.271 | −0.128 | 0.098 | −0.030 | 0.765 | 0.310 | |

| N4-C26 | 0.261 | −0.423 | −0.375 | 0.135 | −0.241 | 0.359 | 0.033 | |

| C26-C33 | 0.294 | −0.850 | −0.423 | 0.105 | −0.318 | 0.249 | 0.180 | |

| C15-C22 | 0.267 | −0.716 | −0.119 | 0.102 | −0.016 | 0.862 | 0.154 | |

| O2-C27 | 0.266 | −0.306 | −0.432 | 0.178 | −0.254 | 0.411 | 0.007 | |

| C30-H31 | 0.267 | −0.790 | −0.285 | 0.044 | −0.241 | 0.153 | 0.004 | |

| Fe1-C13 | 0.084 | 0.265 | −0.124 | 0.095 | −0.029 | 0.767 | 0.353 | |

| H3-N4 | 0.035 | 0.109 | −0.035 | 0.031 | −0.004 | 0.894 | 0.228 | |

| O2-C27 | 0.266 | −0.306 | −0.432 | 0.178 | −0.254 | 0.411 | 0.020 | |

| L2 | Fe1-C15 | 0.085 | 0.285 | −0.133 | 0.102 | −0.031 | 0.768 | 0.337 |

| Fe1-C20 | 0.084 | 0.272 | −0.126 | 0.097 | −0.029 | 0.770 | 0.371 | |

| Fe1-C18 | 0.084 | 0.272 | −0.127 | 0.097 | −0.030 | 0.767 | 0.341 | |

| N4-C26 | 0.264 | −0.439 | −0.375 | 0.133 | −0.242 | 0.354 | 0.032 | |

| C26-C33 | 0.299 | −0.875 | −0.435 | 0.108 | −0.327 | 0.249 | 0.179 | |

| C15-C22 | 0.267 | −0.712 | −0.363 | 0.092 | −0.270 | 0.255 | 0.153 | |

| O2-C27 | 0.271 | −0.321 | −0.451 | 0.185 | −0.266 | 0.411 | 0.016 | |

| C30-H31 | 0.271 | −0.817 | −0.285 | 0.040 | −0.245 | 0.142 | 0.000 | |

| H3-N4 | 0.037 | 0.111 | −0.037 | 0.032 | −0.005 | 0.875 | 0.203 | |

| N35-O37 | 0.369 | −0.309 | −0.643 | 0.283 | −0.360 | 0.440 | 0.068 | |

| O2-H3 | 0.284 | −1.051 | −0.389 | 0.063 | −0.326 | 0.162 | 0.019 | |

| L3 | Fe1-C15 | 0.085 | 0.286 | −0.133 | 0.102 | −0.031 | 0.768 | 0.340 |

| Fe1-C20 | 0.084 | 0.272 | −0.126 | 0.097 | −0.029 | 0.770 | 0.367 | |

| Fe1-C18 | 0.084 | 0.271 | −0.127 | 0.097 | −0.030 | 0.767 | 0.337 | |

| Fe1-C13 | 0.083 | 0.264 | −0.123 | 0.095 | −0.029 | 0.768 | 0.371 | |

| N4-C26 | 0.264 | −0.442 | −0.377 | 0.133 | −0.243 | 0.353 | 0.035 | |

| C26-C33 | 0.296 | −0.862 | −0.429 | 0.107 | −0.322 | 0.249 | 0.180 | |

| C15-C22 | 0.267 | −0.713 | −0.363 | 0.092 | −0.271 | 0.255 | 0.153 | |

| O2-C27 | 0.270 | −0.321 | −0.446 | 0.183 | −0.263 | 0.410 | 0.012 | |

| S35-O38 | 0.157 | 0.056 | −0.173 | 0.094 | −0.080 | 0.540 | 0.083 | |

| C32-S35 | 0.165 | −0.196 | −0.157 | 0.054 | −0.103 | 0.343 | 0.064 | |

| S35-O37 | 0.217 | −0.242 | −0.320 | 0.130 | −0.190 | 0.405 | 0.008 | |

| C30-H31 | 0.269 | −0.806 | −0.282 | 0.040 | −0.242 | 0.143 | 0.003 | |

| H3-N4 | 0.037 | 0.110 | −0.036 | 0.032 | −0.004 | 0.882 | 0.212 | |

| S35-O38 | 0.157 | 0.056 | −0.173 | 0.094 | −0.080 | 0.540 | 0.083 | |

| O38-H39 | 0.294 | −1.007 | −0.380 | 0.064 | −0.316 | 0.169 | 0.026 | |

| O2-H3 | 0.285 | −1.061 | −0.391 | 0.063 | −0.328 | 0.161 | 0.019 | |

| L4 | Fe1-C15 | 0.085 | 0.283 | −0.132 | 0.102 | −0.031 | 0.768 | 0.339 |

| Fe1-C20 | 0.084 | 0.272 | −0.126 | 0.097 | −0.029 | 0.769 | 0.362 | |

| Fe1-C18 | 0.084 | 0.271 | −0.127 | 0.098 | −0.030 | 0.766 | 0.327 | |

| N4-C26 | 0.264 | −0.436 | −0.378 | 0.134 | −0.243 | 0.356 | 0.036 | |

| C26-C33 | 0.291 | −0.837 | −0.417 | 0.104 | −0.313 | 0.249 | 0.186 | |

| C15-C22 | 0.267 | −0.714 | −0.119 | 0.103 | −0.016 | 0.862 | 0.154 | |

| O2-C27 | 0.267 | −0.310 | −0.432 | 0.177 | −0.255 | 0.410 | 0.003 | |

| C30-H31 | 0.269 | −0.802 | −0.284 | 0.042 | −0.242 | 0.148 | 0.008 | |

| H3-N4 | 0.035 | 0.109 | 0.099 | 0.031 | 0.130 | −0.308 | 0.237 | |

| C32-Cl35 | 0.143 | −0.094 | −0.131 | 0.054 | −0.077 | 0.411 | 0.040 | |

| O2-C27 | 0.267 | −0.310 | −0.432 | 0.177 | −0.255 | 0.410 | 0.003 | |

| O2-H3 | 0.288 | −1.077 | −0.396 | 0.064 | −0.333 | 0.160 | 0.020 |

Fig. 5.

Crystal structure of the virus main protease in the complex (6LU7) (water molecules and inhibitor N3 are removed for clarity).

Table 4.

Docking simulation results with Docking Score Energy (DS), sequence between the referenced and ferrocene derivatives and 6LU7 Protein of SARS-CoV-2.

| Compounds | BE | Binding sequence |

|---|---|---|

| L1 | −6.00 | GLY143, CYS145 |

| L2 | −5.20 | TRP218, ARG222 |

| L3 | −4.64 | ARG222, GLY278, ARG279 |

| L4 | −5.01 | GLY143 |

| dexamethasone | −6.69 | THR26, ASN142, GLU166 |

| remdesivir | −1.43 | TYR237, MET276, ASN277, GLY278 |

| hydroxychloroquine | −5.07 | LEU141, SER144, HIS163, GLU166 |

| favipiravir | −3.77 | GLN74, LEU75, VAL77, VAL68, LEU67, PHE66 |

Fig. 6.

Docking simulation of the interaction between Ferrocene derivatives and reference drugs (green color) and 6LU7 protein.

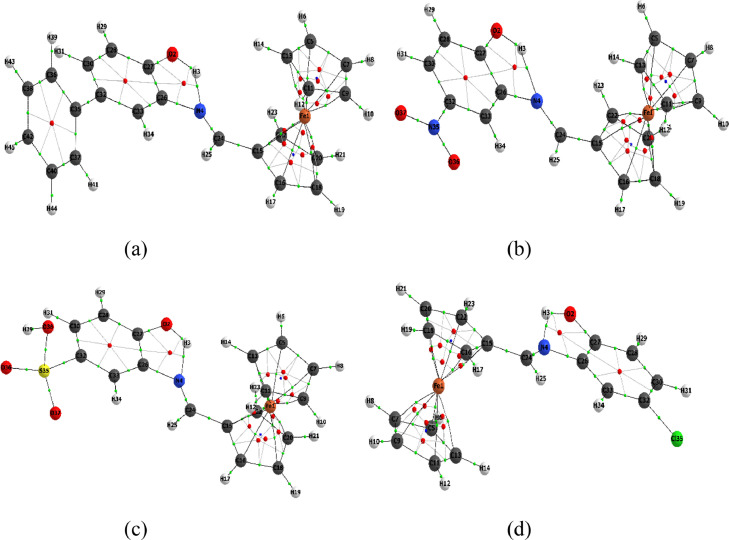

5. QTAIM analysis

In this present work, the electron density, the second derivative electron density of Laplacian electron density , potential energy density, local energy density , kinetic energy density the ratio of –(G/V) and ellipticity) [44,45] of the title compounds (L1-L4) for selected BCPs are listed in Table 4. The AIM molecular maps of the L1-L4 are shown in Fig. 7 (a), (b), (c) and (d) exhibit respectively. In the present case, BCPs at all Iron-Carbon (Fe-C) values for all compounds of and are indicates that closed-shell interactions. The highest (0.085a.u for all) values with corresponding positive (0.282, 0.285, 0.286 and 0.283 a.u) values were found at Fe1-C15 for L1-L4, respectively. Also, one intramolecular hydrogen bond at H3-N4 was confirmed in all selected compounds by the values of, and (e.g. L4, ) = 0.035 a.u, & = 0.109 a.u). In the Table 4, the computed value of 0.143 to 0.299 a.u., and corresponding negative values of , of BCPs, represent that the shared interactions of covalent bonds.

Fig. 7.

AIM Molecular graphs of title compounds: green small spheres (BCPs), small red sphere (RCBs), black lines (bond paths), and ash color solid lines (RCP to BCP ring path).

The asymmetry of electron density distribution is described by bond ellipticity () [46,47]. The highest values were found at Fe-C13, Fe1-C20, Fe1-C13 and Fe1-C20 of respective compounds (L1-L4), showing a highly asymmetric electron density at the BCPs.

6. Conclusion

Since COVID-19 has acquired pandemic status and new variants of corona require the attention of academicians to discover a possible safe and effective drug to ameliorate its effects worldwide. Due to various biological applications of ferrocene derivatives, their structural properties like lipophilicity of ferrocenyl groups, redox potential activation energy, low toxicity, strong antigenic response and oral administration make them potential candidates against COVID-19. In the present study, four new ferrocene derivatives were successfully synthesized and characterized by NMR spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, and single-crystal x-ray diffraction technique. A theoretical insight on synthesized ferrocene derivatives was accomplished by docking score, frontier molecular orbitals energies, active sites, and molecular descriptors which were further compared with drugs being currently used against COVID-19, i.e., dexamethasone, hydroxychloroquine, favipiravir, and remdesivir. Moreover, the inhibitions of ferrocene derivatives were recorded on the core protease (6LU7) protein of SARS-CoV-2 and the effect of substituents on the anti-COVID activity through the molecular docking approach. The docking results for L1-L4 highlighted that the L1 might have better anti-oxidant and anti-COVID19 ability than other currently used drugs. The computational outcome indicated that such compounds have powerful 6LU7 inhibition of SARS-CoV-2. These findings could be helpful for further exploration of new ferrocene derivatives and their potential applications in the prevention and treatment of SARS-CoV-2. The experimental investigation of biological and anti-Covid activity of these compounds is in progress and will be published separately.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ghulam Abbas: Conceptualization, Methodology, writing and reviewing Ahmad Irfan: Computational studies and reviewing, Ishtiaq Ahmed: spectroscopic analysis, Firas Khalil Al-Zeidaneen: Uv-Vis and Mass spectrometry. S. Muthu: Molecular docking, Olaf Fuhr: Single crystal X-ray diffraction and Renjith Thomas Molecular docking and reviewing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The author G Abbas acknowledge Prof Annie K. Powell for Providing lab. facilities at KIT Karlsruhe Germany and A. Irfan to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University, Saudi Arabia for funding through research groups program (R.G.P.1/110/42).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.132242.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Coronaviridae V. Study group of the international committee on taxonomy of, the species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Culp W.C.J. Coronavirus disease 2019: in-home isolation room construction. A&A Pract. 2020;14 doi: 10.1213/XAA.0000000000001218. e0121810.1213/xaa.0000000000001218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.W.H. Organization, COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update, 5 Oct. 2021, (2021)

- 4.Wang C., Horby P.W., Hayden F.G., Gao G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. The Lancet. 2020;395:470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lone S.A., Ahmad A. COVID-19 pandemic–an African perspective. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9:1300–1308. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1775132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellet J., Pepper M. A COVID-19 vaccine: big strides come with big challenges. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9:39. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010039. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patra M., Gasser G. The medicinal chemistry of ferrocene and its derivatives. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017;1:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41570-017-0066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeary R.A. Chronic toxicity of dicyclopentadienyliron (ferrocene) in dogs. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1969;15:666–676. doi: 10.1016/0041-008X(69)90067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaouen G. John Wiley & Sons; 2006. Bioorganometallics: Biomolecules, Labeling, Medicine. 3527607110. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiorina V.J., Dubois R.J., Brynes S. Ferrocenyl polyamines as agents for the chemoimmunotherapy of cancer. J. Med. Chem. 1978;21:393–395. doi: 10.1021/jm00202a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gill T., Mann L. Studies on synthetic polypeptide antigens: XV. the immunochemical properties of ferrocenyl-poly Glu58Lys36Tyr6 (No. 2) conjugates. J. Immunol. 1966;96:906–912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chadwick J., Mercer A.E., Park B.K., Cosstick R., O'Neill P.M. Synthesis and biological evaluation of extraordinarily potent C-10 carba artemisinin dimers against P. falciparum malaria parasites and HL-60 cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:1325–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.12.017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Posner G.H., McRiner A.J., Paik I.-.H., Sur S., Borstnik K., Xie S., Shapiro T.A., Alagbala A., Foster B. Anticancer and antimalarial efficacy and safety of artemisinin-derived trioxane dimers in rodents. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:1299–1301. doi: 10.1021/jm0303711. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm0303711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reiter C., Fröhlich T., Zeino M., Marschall M., Bahsi H., Leidenberger M., Friedrich O., Kappes B., Hampel F., Efferth T. New efficient artemisinin derived agents against human leukemia cells, human cytomegalovirus and Plasmodium falciparum: 2nd generation 1, 2, 4-trioxane-ferrocene hybrids. Eur J Med Chem. 2015;97:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheldrick G.M. SHELXT–Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallograph. Section A. 2015;71:3–8. doi: 10.1107/S2053273314026370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irfan A., Al-Zeidaneen F.K., Ahmed I., Al-Sehemi A.G., Assiri M.A., Ullah S., Abbas G. Synthesis, characterization and quantum chemical study of optoelectronic nature of ferrocene derivatives. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2020;43:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s12034-019-1992-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elsharkawy E.R., Almalki F., Hadda T.B., Rastija V., Lafridi H., Zgou H. DFT calculations and POM analyses of cytotoxicity of some flavonoids from aerial parts of Cupressus sempervirens: docking and identification of pharmacophore sites. Bioorg. Chem. 2020;100 doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Irfan A., Chaudhry A.R., Al-Sehemi A.G. Electron donating effect of amine groups on charge transfer and photophysical properties of 1, 3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazolo [3, 4-b] quinolone at molecular and solid state bulk levels. Optik (Stuttg) 2020;208 doi: 10.1016/j.ijleo.2019.164009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irfan A., Imran M., Al-Sehemi A.G., Assiri M.A., Hussain A., Khalid N., Ullah S., Abbas G. Quantum chemical, experimental exploration of biological activity and inhibitory potential of new cytotoxic kochiosides from Kochia prostrata (L.) Schrad. J. Theor. Comput. Chem. 2020;19 2050012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin R.-.Y., Tang T., Zhou S., Long X., Guo H., Zhou J., Yan H., Li Z., Zuo Z.-.Y., Xie H.-.L. Design, synthesis, antitumor activity and theoretical calculation of novel PI3Ka inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2020;98 doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demirtaş G., Dege N., Ağar E., Şahin S. The Crystallographic, Spectroscopic and Theoretical Studies on (E)-2-[((4-fluorophenyl) imino) methyl]-4-nitrophenol and (E)-2-[((3-fluorophenyl) imino) methyl]-4-nitrophenol Compounds. Iranian J. Chem. Chem. Eng. (IJCCE) 2018;37:55–65. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mikulski D., Eder K., Molski M. Quantum-chemical study on relationship between structure and antioxidant properties of hepatoprotective compounds occurring in Cynara scolymus and Silybum marianum. J. Theor. Comput. Chem. 2014;13 doi: 10.1142/S0219633614500047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Najafi M., Naqvi S.A.R. Theoretical study of the substituent effect on the hydrogen atom transfer mechanism of the irigenin derivatives antioxidant action. J. Theor. Comput. Chem. 2014;13 doi: 10.1142/S0219633614500102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sadasivam K., Jayaprakasam R., Kumaresan R. A DFT study on the role of different OH groups in the radical scavenging process. J. Theor. Comput. Chem. 2012;11:871–893. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219633612500599. [Google Scholar]

- 25.I. Warad, M. Al-Nuri, O. Ali, I.M. Abu-Reidah, A. Barakat, T. Ben Hadda, A. Zarrouk, S. Radi, R. Touzani, H. Elmsellem, Synthesis, physico-chemical, hirschfield surface and DFT/B3LYP calculation of two new hexahydropyrimidine heterocyclic compounds, (2019) http://hdl.handle.net/10576/14835

- 26.Irfan A. Comparison of mono-and di-substituted triphenylamine and carbazole based sensitizers@(TiO2) 38 cluster for dye-sensitized solar cells applications. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2019;1159:1–6. doi: 10.1142/S0219633620500121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahmood A., Irfan A. Effect of fluorination on exciton binding energy and electronic coupling in small molecule acceptors for organic solar cells. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2020;1179 doi: 10.1016/j.comptc.2020.112797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frisch M., Trucks G., Schlegel H., Scuseria G., Robb M., Cheeseman J., Scalmani G., Barone V., Petersson G., Nakatsuji H. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford, CT: 2016. Gaussian 16. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez C., Bosque R., Pérez S., Roig A., Molins E., Solans X., Font-Bardía M. Relationships between 57Fe NMR, Mössbauer parameters, electrochemical properties and the structures of ferrocenylketimines. J. Organomet. Chem. 2006;691:475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2005.09.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imrie C., Kleyi P., Nyamori V.O., Gerber T.I., Levendis D.C., Look J. Further solvent-free reactions of ferrocenylaldehydes: synthesis of 1, 1′-ferrocenyldiimines and ferrocenylacrylonitriles. J. Organomet. Chem. 2007;692:3443–3453. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2007.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benito M., López C., Solans X., Font-Bardía M. Palladium (II) compounds with planar chirality. X-Ray crystal structures of (+)-(R)-[{(η5-C5H4)–CH N–CH (Me)–C10H7} Fe (η5-C5H5)] and (+)-(Rp, R)-[Pd {[(Et–C C–Et) 2 (η5-C5H3)–CH N–CH (Me)–C10H7] Fe (η5-C5H5)} Cl] Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1998;9:4219–4238. doi: 10.1016/S0957-4166(98)00437-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Houlton A., Miller J.R., Silver J., Jassim N., Ahmet M.J., Axon T.L., Bloor D., Cross G.H. Molecular materials for non-linear optics. Second harmonic generation and the crystal and molecular structure of the 4-nitrophenylimine of ferrocenecarboxaldehyde. Inorganica Chim Acta. 1993;205:67–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-1693(00)87356-9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parr R.G., Chattaraj P.K. Principle of maximum hardness. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:1854–1855. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00005a072. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parr R.G., Pearson R.G. Absolute hardness: companion parameter to absolute electronegativity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:7512–7516. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00364a005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pearson R.G. Absolute electronegativity and absolute hardness of Lewis acids and bases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:6801–6806. doi: 10.1021/ja00310a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koopmans T. Ordering of wave functions and eigenenergies to the individual electrons of an atom. Physica. 1933;1:104–113. doi: 10.1016/S0031-8914(34)90011-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.A. Rauk, Orbital Interaction Theory of Organic Chemistry, John Wiley & Sons20040471461849.

- 38.Geerlings P., De Proft F., Langenaeker W. Conceptual density functional theory. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:1793–1874. doi: 10.1021/cr990029p. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr990029p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.A. Vektariene, G. Vektaris, J. Svoboda, A theoretical approach to the nucleophilic behavior of benzofused thieno [3, 2-b] furans using DFT and HF based reactivity descriptors, Arkivoc, (2009) http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/ark.5550190.0010.730

- 40.Akaike T. Role of free radicals in viral pathogenesis and mutation. Rev. Med. Virol. 2001;11:87–101. doi: 10.1002/rmv.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.P. Politzer, D.G. Truhlar, Chemical Applications of Atomic and Molecular Electrostatic potentials: reactivity, structure, scattering, and Energetics of organic, inorganic, and Biological Systems, Springer Science & Business Media2013147579634X.

- 42.Stewart R.F. On the mapping of electrostatic properties from Bragg diffraction data. Chem Phys Lett. 1979;65:335–342. doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(79)87077-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murray J.S., Politzer P. The electrostatic potential: an overview. Wiley Interdisc. Rev. 2011;1:153–163. doi: 10.1002/wcms.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sangeetha K., Rajina S., Marchewka M., Binoy J. The study of inter and intramolecular hydrogen bonds of NLO crystal melaminium hydrogen malonate using DFT simulation, AIM analysis and Hirshfeld surface analysis. Mater. Today. 2020;25:307–315. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srinivasan P., Asthana S., Pawar R.B., Kumaradhas P. A theoretical charge density study on nitrogen-rich 4, 4′, 5, 5′-tetranitro-2, 2′-bi-1H-imidazole (TNBI) energetic molecule. Struct. Chem., 2011;22:1213–1220. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neogi S.G., Das A., Chaudhury P. Investigation of plausible mechanistic pathways in hydrogenation of η 5-(C 5 H 5) 2 Ta (H)= CH 2: an analysis using DFT and AIM techniques. J. Mol. Model. 2014;20:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00894-014-2132-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.G.G. Sheeba, D. Usha, M. Amalanathan, M.S.M. Mary, Identification of structure activity relation of a synthetic drug 2, 6-pyridine dicarbonitrile using experimental and theoretical investigation, Volume XVI, Issue XI, November 2020, page 89-113.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.