Abstract

Introduction:

In 2018, the Baltimore City Health Department launched a mobile clinic called Healthcare on The Spot, which offers low-threshold buprenorphine services integrated with health care services to meet the needs of people who use drugs. In addition to buprenorphine management, The Spot offers testing and treatment for hepatitis C, sexually transmitted infections, and HIV, as well as pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV, wound care, vaccinations, naloxone distribution, and case management.

Methods and Materials:

This cohort analysis includes clinical service data from the first 15 months of The Spot mobile clinic, from September 4, 2018, to November 23, 2019. The Spot co-located with the Baltimore syringe services program in five locations across the city. Descriptive data are provided for patient demographics and services provided, as well as percent of patients retained in buprenorphine treatment at one and three months. Logistic regression identified factors associated with retention at three months.

Results:

The Spot mobile clinic provided services to 569 individuals from September 4, 2018, to November 23, 2019, including prescribing buprenorphine to 73.8% and testing to more than 70% for at least one infectious disease. Patients receiving a prescription for buprenorphine were more likely to be tested for HIV, hepatitis C, and sexually transmitted infections, as well as receive treatment for hepatitis C and preventive services including vaccination and naloxone distribution. The Spot initiated HIV treatment for four patients and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for twelve patients. More than 32% of patients had hepatitis C; nineteen of these patients initiated treatment for hepatitis C with eight having a documented cure. Buprenorphine treatment retention was 56.0% at one month and 26.2% at three months. Patients who were Black or receiving treatment for hepatitis C were more likely to be retained in buprenorphine treatment at three months.

Conclusions:

Increasing access to integrated medical services and drug treatment through low-threshold, community-based models of care can be an effective tool for addressing the effects of drug use.

Keywords: Opioid use disorder, Low-threshold, Buprenorphine, Mobile, Hepatitis C, Integrated care

1. Introduction

The opioid epidemic is a public health crisis requiring treatment providers to continuously innovate and develop effective strategies to reduce morbidity and mortality. In 2018, 2,143 individuals died from an opioid-related overdose in Maryland, four times the number in 2008 (Maryland Department of Health, 2019). Baltimore City has the ninth highest overdose rate of any jurisdiction in the United States and had 814 opioid-related overdose deaths in 2018 (Maryland Department of Health, 2019). In addition to overdose risk, people living with opioid use disorder (OUD)1 are at high risk for infectious diseases related to drug use, including HIV and hepatitis C (HCV). Approximately 10% of new HIV infections are attributed to injection drug use in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020b), and prevalence of HCV among people who use drugs (PWUD) is estimated to be 50–80%, compared to 1.1% in the general U.S. population (Degenhardt et al., 2017; Denniston et al., 2014; Shepard et al., 2005; Beetham et al., 2019; Sulkowski & Thomas, 2005). The syndemic of opioid use disorder, HIV, and HCV requires coordinated efforts to reduce overdose death and to achieve national goals for the elimination of HIV and HCV (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020a; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017).

Medications for OUD (MOUD), including methadone and buprenorphine, decrease overdose mortality (Krawczyk et al., 2020; Sordo et al., 2017; Wakeman et al., 2020), but access to treatment remains challenging (Beetham et al., 2019). In 2017, only one-third of adults with OUD engaged in treatment (Wilkerson et al., 2016), and research has shown delays in treatment initiation to increase risk of opioid-related mortality (Peles et al., 2013), which indicates a need for increased access to care.

Compared to more traditional treatment programs, research has shown low-threshold buprenorphine programs to increase patient engagement in treatment (Bhatraju et al., 2017; Kourounis et al., 2016; Payne et al., 2019). Low-threshold programs are easily accessible, flexible, and remove barriers by offering individualized treatment plans, home medication induction and administration, less frequent visits; they do not require adjuvant psychological treatment and allow for relapses (Kourounis et al., 2016). Low-threshold buprenorphine can be provided in primary care clinics, but research has also shown it to be successful through a mobile clinic model, with or without additional co-located services (Gibson et al., 2017; Krawczyk et al., 2019). Despite the availability of 28 opioid treatment programs in Baltimore (Maryland Department of Health, 2020), a mobile clinic that provides buprenorphine treatment outside of Baltimore’s correctional building has had significant engagement in their low-threshold model (Krawczyk et al., 2019).

Models of care with integrated services to address the unique medical and behavioral needs of people living with OUD may facilitate engagement and retention in services. Research has indicated that co-located treatment, including MOUD and antiretroviral therapy (ART), can increase ART engagement, adherence, and reduce HIV transmission (Fanucchi et al., 2019; Low et al., 2016). PWUD have reported that low-barrier HCV care in locations such as mobile clinics and drug treatment programs would remove barriers they face in accessing HCV treatment (Ward et al., 2020). Numerous studies have shown that when given access to treatment, PWUD can have HCV cure rates comparable to the general population (Cachay et al., 2015; Caven et al., 2019; Gayam et al., 2019; Hajarizadeh et al., 2018; Latham et al., 2019), and retention in OUD treatment is associated with a higher likelihood of HCV cure (Norton et al., 2016; Rosenthal et al., 2020).

In response to the needs of people living with OUD in Baltimore City, the Baltimore City Health Department’s (BCHD) Sexual Health and Wellness Clinics launched a mobile clinic called Healthcare on the Spot (The Spot) in 2018. The Spot co-locates with BCHD’s mobile Syringe Services Program (SSP) to offer free, low-threshold, integrated buprenorphine treatment and health care services in areas with high rates of overdose across Baltimore City.

To determine whether The Spot intervention reduces risk of death and overdose, and increases uptake of evidence-based services among people who inject drugs (PWID), a comparative effectiveness, two-arm, matched-pair cluster randomized trial is being conducted in 12 neighborhood sites where the BCHD offers mobile SSP services [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03567174]. The study recruits PWID at each site prior to randomization, and in each site pair, the study team assigns one site to the control condition and the other site to The Spot intervention. The RCT is ongoing and results will be available in 2022.

This cohort analysis includes clinical service data from the first 15 months of The Spot mobile clinic, from September 4, 2018, to November 23, 2019. The aims are to 1) describe The Spot program, 2) characterize the population accessing care and services that they received, 3) determine retention rates for buprenorphine treatment at one and three months, and 4) assess factors associated with retention in buprenorphine treatment at three months. Trial outcomes, which are forthcoming, will be assessed in prospectively enrolled cohorts followed in intervention (Spot) and control neighborhoods.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. The Spot mobile clinic model

The Spot mobile clinic parks at five distinct locations for one clinical session (9am-2pm) per week, five days per week. BCHD has a well-established SSP that delivers syringe services to more than 3,000 clients per year at more than a dozen locations across the city that are selected due to high overdose rates. The Spot mobile clinic program began by co-locating at one SSP location, and expanded to five locations over the course of the first year, with specific sites selected from established SSP sites via matched-pair cluster randomization. At some locations, the two vans are parked next to each other to facilitate direct referrals, and at others, the vans are separated by time or space depending on the logistics and the surrounding community’s request. Advertising is limited and consists of fliers describing all Spot services distributed on SSP vans, and most new patients are referred through word-of-mouth in the community. Most patients accessing care come to a consistent location, though they may transfer locations if needed.

The mobile clinic is a 36-foot recreational vehicle that is outfitted with two exam rooms, a space for phlebotomy, a bathroom, and waiting area for patients. Each session is staffed by a multidisciplinary team made up of two providers (physicians and/or nurse practitioners), one case manager, and one community health worker, who drives the van and is a certified phlebotomist and point-of-care tester. All providers are waivered to prescribe buprenorphine and are trained in STIs, PrEP, and HCV treatment. Some providers are also HIV specialists and/or have wound care certification.

Services are free of charge, and patients do not need identification, health insurance, or other legal documentation to receive services. Maryland does not require identification to pick up controlled substances, and grant funds are available to cover the cost of medication for uninsured or underinsured patients at participating pharmacies. Patients may present for any service offered, but most often present requesting buprenorphine services. All patients are encouraged to utilize testing services on their first visit. Patients are seen on a first-come, first-served basis and no appointments are scheduled. However, patients expected for follow up buprenorphine visits are always seen if they arrive before closing time, and two or more slots are reserved each day for new patients presenting to engage in buprenorphine treatment.

Case managers perform a social needs assessment for all new patients and assist patients with medical insurance enrollment, connection to primary care and mental health services, housing referrals, obtaining identification cards or other documentation, and transportation, including bus tokens. Follow up on these items occurs by phone between weekly visits.

The Spot encourages all patients to utilize rapid HIV and HCV testing, as well as testing for STIs including gonorrhea/chlamydia (urine) and syphilis (blood). Patients presenting for buprenorphine services give urine samples or oral swabs for toxicology screening. STI testing samples are sent to the BCHD lab, and results are generally available by the patient’s next visit. Toxicology samples are sent to a commercial lab and billed to the patient’s insurance. Rapid HIV and HCV results are available within 20 minutes, usually by the time the patient is seeing the provider. If a rapid HIV or HCV test is positive, labs are then drawn for evaluation and treatment and sent to a commercial lab with results available by the next visit. If individuals report that they have HIV or HCV and are not in care, they are offered lab work to engage in care.

After testing, new patients see a provider who performs a medical history and physical exam as indicated. Clinicians discuss all services available on the first visit to gauge patients’ interest and engage in patient-centered decision-making around initiation of other services such as HCV treatment or PrEP. No limitations exist to who or when someone can engage in particular services, and buprenorphine adherence is not a factor in initiating any other service. For patients with OUD, providers routinely prescribe a seven-day prescription for buprenorphine at the initial visit, unless a contraindication is present such as recent methadone use. Providers review program structure and buprenorphine home induction instructions and distribute naloxone to any patient who does not have a supply. Counseling services are not available on The Spot, but patients are given information about local meetings or linked to counseling services if desired.

Providers adjust buprenorphine dosing as needed at weekly visits. After the first month, patients reporting significant reduction or cessation of illicit opioids, improvement in achievement of recovery goals, and/or absence of illicit opioids on toxicology screening are considered for spacing of appointments up to four weeks. If a pattern of having buprenorphine-negative or methadone-positive toxicology screening continues, patients are discharged and offered referral to another treatment program. After a few weeks from program discharge, patients may return with an opportunity to re-engage in treatment. The Spot does not discharge patients for continued illicit substance use as long as they are taking buprenorphine appropriately and engaging in the program. Patients who wish to transfer buprenorphine treatment to their primary care provider or another program may do so, but almost all patients choose to continue their buprenorphine treatment on The Spot.

At the time of intake, providers assess the need for additional services including vaccination for hepatitis A and influenza, as well as wound care services including incision and drainage and specialty wound care supplies. For patients wishing to engage in PrEP for HIV prevention, labs can be drawn and medication prescribed the same day, provided the rapid HIV test is negative and no contraindication is present. For newly diagnosed or out-of-care HIV-positive patients in need of treatment, providers offer rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy if no contraindication is present, utilizing medication starter packs or same-day prescriptions. Case managers can also link patients to other HIV clinics of their choice.

Providers counsel patients about HCV transmission risk reduction and treatment availability at the first visit, and complete an evaluation for patients with active HCV when lab work has returned by the following week. When additional testing is needed, such as liver elastography or abdominal ultrasound, case managers assist with scheduling and follow-up. If patients have evidence of decompensated cirrhosis, providers refer them to a partnering specialty clinic. Once evaluation is complete, the provider prescribes HCV medication and submits prior authorization to insurance through a partnering specialty pharmacy. If approved, the medication is delivered to The Spot team, and the patient picks up the medication at their next appointment. Providers track progress on HCV treatment (eight or twelve weeks) at regular appointments, and they document HCV sustained virologic response (SVR) indicating cure with blood work obtained twelve weeks after completion of treatment showing undetectable HCV RNA.

2.2. Study design

This cohort study includes all patients accessing services on The Spot from September 4, 2018, to November 23, 2019. This study period followed patients initiating buprenorphine for three months (106 days) through March 8, 2020, when in-person services on The Spot were paused due to COVID-19, to ascertain treatment outcomes. Johns Hopkins institutional review board determined this study to be quality improvement and exempt from human subjects research.

2.3. Data management and variable definitions

The electronic medical record (INSIGHT) captured demographic, behavioral, and clinical data as part of routine clinical care. The study defined utilization for each service as the patient accessing that service at least once during the study period.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics delineate patients’ characteristics and service delivery. Pearson’s χ2 tests compared demographic and service utilization characteristics between those initiating buprenorphine treatment and those not initiating buprenorphine treatment on The Spot. The HCV care continuum represents the percentage of HCV antibody positive patients at each step.

Because most patients access buprenorphine prescriptions on The Spot mobile clinic on a weekly basis, the study assessed retention in treatment at three months (91 days) including a 2-week grace period. The study considered individuals to be retained at three months if they received a buprenorphine prescription between 91 days and 106 days, regardless of prior lapses in treatment of any length. Retention as defined does not reflect uninterrupted buprenorphine treatment for all patients, but allows for patients to have lapses in care and re-engage over the analysis period. The study defined disengagement and re-engagement as having a lapse in buprenorphine prescription for five weeks or longer, but returning to care and receiving a buprenorphine prescription during the study period. Univariate and multivariate logistic regressions identified factors associated with retention in buprenorphine treatment at three months.

3. Results

3.1. Study population

The Spot mobile clinic provided services to 569 individuals from September 4, 2018, to November 23, 2019. Table 1 has detailed characteristics of all patients served and stratified by buprenorphine initiation. The majority of patients served on The Spot were male (65.6%) and Black (76.6%). The largest age category was between ages 30 and 49 years old (42.2%). Slightly more than 6 percent (6.2%) of patients were HIV positive; 32.2% were HCV antibody positive; and 7.6% had lab positivity for syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia. Comparing patients who received a prescription for buprenorphine to those who did not, the former were more likely to be male (69.8% vs 53.7%, p<0.001) and HCV positive (34.5% vs 25.5%, p=0.043).

Table 1:

Demographic characteristics and service utilization of patients initiating care on The Spot mobile clinic from September 4, 2018 to November 23, 2019, by buprenorphine initiation status.

| Characteristics and Service Utilization |

Total (N = 569) |

Not prescribed buprenorphi ne (N=149) |

Prescribed buprenorphin e (N = 420) |

p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Age | <30 years | 70 (12.3%) | 20 (13.4%) | 50 (11.9%) | 0.366 |

| 30-49 years | 240 (42.2%) | 66 (44.3%) | 174 (41.4%) | ||

| 50-59 years | 214 (37.6%) | 48 (32.2%) | 166 (39.5%) | ||

| >=60 years | 45 (7.9%) | 15 (10.1%) | 30 (7.1%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 373 (65.6%) | 80 (53.7%) | 293 (69.8%) | **<0.001 |

| Female | 196 (34.4%) | 69 (46.3%) | 127 (30.2%) | ||

| Race | Black | 436 (76.6%) | 118 (79.2%) | 318 (75.7%) | 0.689 |

| White | 120 (21.1%) | 28 (18.8%) | 92 (21.9%) | ||

| Other | 13 (2.3%) | 3 (2.0%) | 10 (2.4%) | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 5 (0.9%) | 1 (0.7%) | 4 (1.0%) | 0.752 |

| Not Hispanic | 564 (99.1%) | 148 (99.3%) | 416 (99.0%) | ||

| Visits Attended | 1-2 visits | 269 (47.3%) | 142 (95.3%) | 127 (30.2%) | **<0.001 |

| 3-8 visits | 199 (35.0%) | 7 (4.7%) | 192 (45.7%) | ||

| >8 visits | 101 (17.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 101 (24.1%) | ||

| HIV | Tested - rapid 4th generation | 439 (77.2%) | 98 (65.8%) | 341 (81.2%) | **<0.001 |

| HIV positive | 35 (6.2%) | 6 (4.0%) | 29 (6.9%) | 0.209 | |

| Newly diagnosed on Spot | 3 (0.5%) | 1 (0.7%) | 2 (0.5) | 0.778 | |

| Self-reported previously diagnosed | 32 (5.6%) | 5 (3.4%) | 27 (6.4%) | 0.162 | |

| Treated on The Spot van | 4 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (1.0%) | 0.232 | |

| Hepatitis C (HCV) | Tested – rapid antibody | 403 (70.8%) | 94 (63.1%) | 309 (73.6%) | *0.016 |

| HCV antibody positive | 183 (32.2%) | 38 (25.5%) | 145 (34.5%) | *0.043 | |

| Newly diagnosed on Spot | 93 (16.3%) | 19 (12.8%) | 74 (17.6%) | 0.167 | |

| Self-reported previously diagnosed | 90 (15.8%) | 19 (12.8%) | 71 (16.9%) | 0.233 | |

| HCV RNA test performed | 81 (14.2%) | 12 (8.1%) | 69 (16.4%) | *0.012 | |

| HCV RNA positive | 58 (10.2%) | 9 (6.0%) | 49 (11.7%) | 0.051 | |

| Treated on The Spot van | 19 (3.3%) | 1 (0.7%) | 18 (4.3%) | *0.035 | |

| STI (syphilis or GC/CT) | Tested | 462 (81.2%) | 87 (58.4%) | 375 (89.3%) | **<0.001 |

| Positive | 43 (7.6%) | 7 (4.7%) | 36 (8.6%) | 0.124 | |

| Treated on The Spot van | 22 (3.9%) | 2 (1.3%) | 20 (4.8%) | 0.063 | |

| Preventive Care | Hepatitis A vaccine | 41 (7.2%) | 4 (2.7%) | 37 (8.8%) | *0.013 |

| PrEP prescribed | 12 (2.1%) | 2 (1.3%) | 10 (2.4%) | 0.448 | |

| Naloxone distributed | 266 (46.8%) | 25 (16.8%) | 241 (57.4%) | **<0.001 | |

| Wound Care | Wound Care | 23 (4.0%) | 9 (6.0%) | 14 (3.3%) | 0.149 |

p-values calculated using Pearson’s c2, compares prescribed vs. not prescribed in each category

Statistically significant p-value <0.05

Statistically significant p-value <0.01

3.2. Services delivered

Table 1 shows services delivered. Slightly more than seventy percent (73.8%) of patients received at least one prescription for buprenorphine. Providers distributed naloxone to 46.8% of patients, and provided wound care to 4.0% patients, including 9 patients who did not receive a buprenorphine prescription. Patients initiating buprenorphine completed a mean of 6.5 visits on The Spot (median=4, range=1 to 45) compared to 1.2 visits among those not initiating buprenorphine (median=1, range=1 to 6).

Providers tested the majority of patients for HIV (77.2%) and patients receiving a buprenorphine prescription were more likely to get tested compared to those who did not receive a prescription (81.2% vs 65.8%, p<0.001). A total of 35 HIV-positive patients received care, including three who were newly diagnosed through testing on The Spot. Of the 35 HIV-positive patients, 23 were already in care and on antiretroviral therapy. Of the remaining twelve needing treatment, four engaged in HIV care on The Spot and initiated antiretroviral therapy, two were linked to care at an outside clinic per their choice, and six either declined care or were lost to follow-up.

Twelve HIV-negative patients initiated PrEP for HIV prevention. Providers engaged all patients receiving HIV treatment or PrEP in the buprenorphine treatment program.

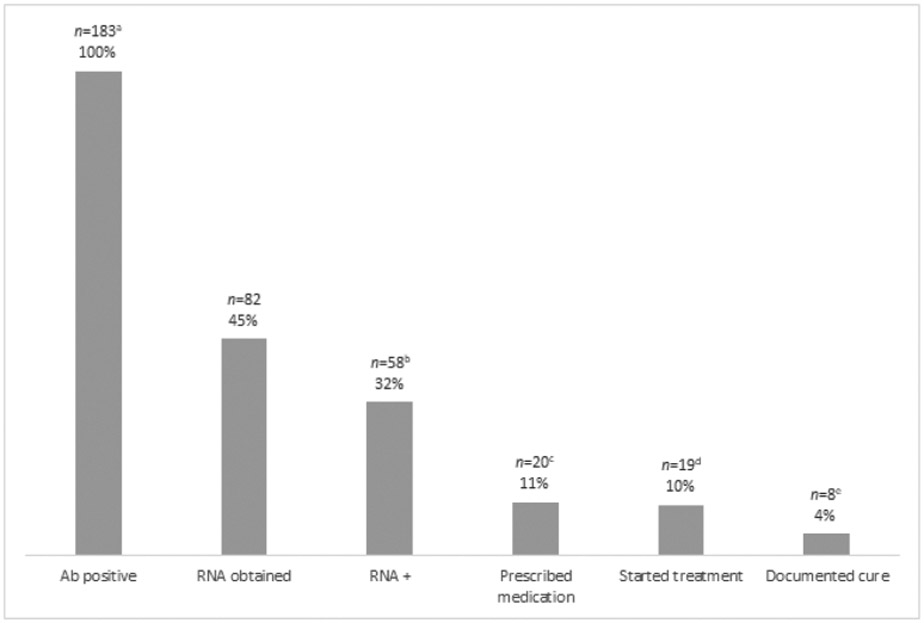

Providers tested a total of 70.8% patients for HCV with a rapid antibody test. Patients receiving a prescription for buprenorphine were more likely to get tested compared to those who did not (73.6% vs 63.1%, p=0.016). Ninety-three patients had a positive rapid antibody test, and an additional 90 self-reported previously positive antibody tests and providers did not retest, of which 19 reported being previously cured or in treatment elsewhere. Figure 1 describes the HCV treatment cascade. Eighty-two patients completed HCV RNA testing to confirm active infection, 24 of whom had an undetected HCV viral load, indicating previously resolved or cured infection. The remaining 58 individuals had detectable RNA, indicating active infection needing treatment. Of those, providers prescribed treatment for 20 and referred one to specialty care due to decompensated cirrhosis. One of the patients prescribed treatment was denied medication by their insurance company. Only one patient prescribed treatment was not enrolled in the buprenorphine program. Nineteen patients started HCV treatment and eight of those had a documented SVR indicating cure, with 11 lost to follow-up before SVR labs could be drawn. Most individuals completed screening for syphilis and/or gonorrhea/chlamydia (81.2%). Patients receiving a prescription for buprenorphine were more likely to be tested for a sexually transmitted infection (89.3% vs. 58.4%, p<0.001), and 3.9% of patients received treatment for at least one of these infections. Providers provided hepatitis A vaccination to 7.2% of patients, and patients receiving a prescription for buprenorphine were more likely to get this vaccination (8.8% vs. 2.7%, p=0.013).

Figure 1: Hepatitis C care continuum for patients with positive HCV antibody on The Spot mobile clinic from September 4, 2018 to November 23, 2019.

a 93 patients had positive rapid HCV antibody test, 90 self-reported prior diagnosis, and 19 of these reported being previously cured or in treatment elsewhere.

b 24 patients had an undetectable HCV RNA, indicating previously resolved or cured infection.

c 1 patient was referred to specialty care due to decompensated cirrhosis.

d 1 patient was denied treatment by their insurance company.

e 11 patients were lost to follow up before labs could be drawn 12 weeks after treatment.

3.3. Retention in opioid use disorder treatment

Of the 420 patients receiving at least one prescription for buprenorphine, 56.0% were retained in care at one month and 26.9% were retained in care at three months. Among the 110 patients retained in care at three months, 28 of them had lapses of 5 weeks or longer and returned to care before the end of the study period. Among those not retained in care at three months, providers discharged 97 from the program. Reasons for discharge included having methadone in urine toxicology (indicating enrollment in a methadone program), a pattern of urine toxicology indicating buprenorphine is not being taken appropriately (negative buprenorphine or norbuprenorphine/buprenorphine ratio indicating adulteration), or an excessive number of missed visits. The remaining 213 individuals not retained in care at three months were lost to follow-up. In univariable analysis, white patients were less likely than Black patients to be retained at three months (OR=0.31, 95% CI=0.16–0.61), and this remained significant in multivariable analysis (AOR=0.32, 95% CI=0.16–0.61) (Table 2). Patients receiving HCV treatment were approximately five times more likely to be retained at three months compared to those not in HCV treatment in both univariable and multivariable analysis (OR=4.81, 95% CI=1.82–12.74; AOR=5.51, 95% CI=1.99–15.27).

Table 2:

Logistic regression of factors associated with 3-month treatment retention for patients initiating buprenorphine on The Spot mobile clinic from September 4, 2018 to November 23, 2019.

| Characteristics | Retained at 3 months (N= 110) n (%) |

Not retained at 3 months (N=310) n (%) |

Odds Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval for OR |

Adjustedc Odds Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval for Adj OR |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <30 years | 15 (13.6%) | 35 (11.3%) | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| 30-49 years | 36 (32.7%) | 138 (44.5%) | 0.61 | (0.30 - 1.23) | 0.56 | (0.27 - 1.17) | |

| 50-59 years | 49 (44.6%) | 117 (37.7%) | 0.98 | (0.49 - 1.95) | 0.68 | (0.33 - 1.42) | |

| >=60 years | 10 (9.1%) | 20 (6.5%) | 1.17 | (0.44 - 3.08) | 0.77 | (0.28 - 2.09) | |

| Gender | Male | 83 (75.5%) | 210 (67.7%) | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Female | 27 (24.5%) | 100 (33.3%) | 0.68 | (0.42 - 1.12) | 0.72 | (0.43 - 1.20) | |

| Race | Black/AA | 97 (88.2%) | 221 (71.3%) | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| White | 11 (10.0%) | 81 (26.1%) | **0.31 | (0.16 - 0.61) | **0.32 | (0.16 - 0.65) | |

| Other | 2 (1.8%) | 8 (2.6%) | 0.57 | (0.12 - 2.73) | 0.51 | (0.11 - 2.47) | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (1.3%) | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Not Hispanic | 110 (100.0%) | 306 (98.7%) | |||||

| Comorbidity | HCV positive | 33 (30.0%) | 112 (36.1%) | 0.76a | (0.47 - 1.21) | 1.03 a | (0.62 - 1.71) |

| HIV positive | 5 (4.6%) | 24 (7.7%) | 0.57a | (0.21 - 1.53) | 0.56a | (0.20 - 1.53) | |

| Co-located care | HCV treatment | 11 (10.0%) | 7 (2.3%) | **4.81b | (1.82 - 12.74) | **5.51b | (1.99 - 15.27) |

| HIV treatment | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (1.3%) | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| PrEP | 2 (1.8%) | 8 (2.6%) | 0.70b | (0.15 - 3.34) | 0.89b | (0.17 - 4.56) | |

| Wound Care | 1 (1.0%) | 13 (4.2%) | 0.21b | (0.03 - 1.62) | 0.29b | (0.04 - 2.37) | |

Reference values for odds ratios are HCV negative and HIV negative, respectively.

Reference values for odds ratios are no HCV treatment, no PrEP, no wound care, respectively.

Adjusted for age, gender and race.

Statistically significant p-value <0.05

Statistically significant p-value <0.01

4. Discussion

The Spot has shown that a mobile, low-threshold, integrated care model is feasible for engaging and retaining PWUD in buprenorphine treatment and health care services. Almost 75% of patients accessing care on The Spot received a prescription for buprenorphine, and 27% of those remained in treatment at three months. Though retention after the first few weeks remains a challenge, our retention rate was comparable to another mobile buprenorphine program (Krawczyk et al., 2019). Patients receiving a buprenorphine prescription were more likely to be tested for infectious diseases, engage in HCV treatment, and receive preventive services. The ability to diagnose and treat infectious diseases associated with substance use on site reduces barriers to access, and facilitates an environment of whole-person care.

Patients’ demand for buprenorphine services was higher than we had initially anticipated. Despite the availability of other services, most patients came for buprenorphine treatment. Once the program was established, word-of-mouth referrals became the norm, and nearly every day providers turned away patients due to limited availability. Though qualitative data have not been formally collected, Spot patients have reported preferring this model of care because it is easily accessible, in their neighborhood, and offers same-day start of medication. However, providers discharged 23% of patients treated with buprenorphine from care, and over half ultimately fell out of care. Though these data do not have the breakdown of discharge reasons, in practice, almost all discharges were due to evidence of methadone use or repeated evidence of not taking buprenorphine. The Spot practice is to re-engage patients when they return requesting treatment, and this is supported by the 25% of patients retained in care at three months who were noted to have had a lapse in care of five weeks or longer during those three months. Anecdotally, many patients who were initially discharged or lost to follow-up had returned and were successfully engaged for several months on their second or third attempt at engagement. Notably, patients retained in treatment were more likely to be Black, though reasons for this are unclear. The high utilization of mobile low-threshold buprenorphine treatment speaks to a likely pent-up demand for this service model, and more research is needed to understand reasons for engagement with The Spot and factors associated with both retention and attrition.

Several factors contributed to limited engagement in HCV treatment. First, the overall prevalence of HCV was 32.2%, which is lower than expected for PWUD, a population that has an estimated prevalence of 50–80% compared to 1.1% in the general population (Degenhardt et al., 2017; Denniston et al., 2014; Sulkowski & Thomas, 2005). Though we did not systematically collect data, our clinical experience suggested that Spot patients reported more intranasal drug use rather than injection drug use, which research has been to have a lower HCV risk (Des Jarlais et al., 2018). Second, more than 70% of patients were discharged or lost to follow-up within the first three months of buprenorphine treatment, making HCV evaluation and treatment challenging. Not surprisingly, the data showed that patients who were retained in buprenorphine treatment were more likely to have initiated HCV treatment on The Spot. Efforts made over the course of the study period reduced time from care initiation to HCV treatment prescription, but several factors limited HCV treatment engagement. Most people accessed our services for buprenorphine, and HCV was a secondary priority so they deferred blood draws or treatment discussions. Additionally, many people had difficult venous access, which delayed the blood work required for clinical evaluation and medication authorization by insurance.

Several areas of programmatic and system-level changes could improve HCV treatment engagement. First, offering syringe exchange services on The Spot could engage more PWID not interested in buprenorphine. Second, co-locating The Spot with outpatient drug treatment programs or drop-in centers serving PWUD may help to expand access to HCV treatment. Finally, removing the requirement for insurance prior authorization would facilitate HCV treatment initiation before patients are lost to follow-up, particularly in the era of simple, oral, pan-genotypic HCV regimens. Creating models of care that target PWUD and reduce barriers to HCV treatment and cure are critical to achieve national goals for HCV elimination (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017).

HIV testing and treatment services were well utilized among patients, though PrEP uptake was limited. About two-thirds of HIV+ individuals receiving Spot services were already engaged in care and on ART. Many of those individuals received HIV care in clinics that also offer buprenorphine services, indicating that community-based mobile buprenorphine treatment may provide a model of care that serves individuals who otherwise would not engage in co-located services in a traditional clinic. Of the twelve HIV-positive patients who were not already engaged in HIV care, only half initiated ART on The Spot or were linked to an outside program, and the other half declined care or were lost to follow-up before engaging in treatment, often after only one visit. National goals for Ending the HIV Epidemic aim for 95% of individuals being linked to care and achieve viral load suppression, though current national data show only about 63% are virally suppressed (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Likewise, current PrEP coverage rates are only about 12% of eligible individuals nationwide (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020), and PrEP uptake among PWID is particularly low at 0–3% in a systematic review (Mistler et al., 2020). Despite lowering barriers to HIV treatment and prevention services by offering community-based co-located services and same-day medication start, efforts should continue to identify barriers to engagement in this population.

This study has limitations. First, data collected for clinical purposes may be incomplete. Second, many variables that may be of interest in characterizing the study population, such as housing status or drug use patterns, were not collected systematically in the EMR and therefore could not be compiled and reported here.

5. Conclusions

Increasing access to integrated medical services and drug treatment through low-threshold, community-based models of care can be an effective tool as communities struggle with the effects of drug use. Data from the first 15 months of the program show this model is feasible with high rates of engagement of individuals seeking care for stigmatizing conditions. Further evaluation is needed to show long-term engagement and potential impact of this type of program on indicators such as overdose rate and HCV incidence.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the staff of The Spot mobile clinic and all of the patients that have entrusted us with their care. We would like to thank the Baltimore City Health Commissioner and Deputy Commissioner of Population Health and Disease Prevention for believing in and supporting the team. The BCHD Sexual Health and Wellness Clinics, Syringe Services Program, and Opioid Intervention Team have provided essential ongoing collaboration and support. Finally, many external partners have contributed to this project including Johns Hopkins University Division of Infectious Diseases, Caremax Pharmacy, Health Care for the Homeless, IBR REACH Health Services, and Johns Hopkins Bayview Wound Care.

Role of the funding source

Funding for The Spot services is provided by grants from Maryland’s Opioid Operations Command Center, the Maryland Department of Health, the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA045556, K24 DA035684). Susan Sherman receives funding from the Johns Hopkins Center for AIDS Research and the Bloomberg American Health Initiative. The funding sources had no contribution to the study design, analysis or interpretation of data, or writing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

None

Abbreviations: OUD = opioid use disorder, PWUD = people who use drugs, PWID = people who inject drugs, BCHD = Baltimore City Health Department, SSP = Syringe services program, HIV = human immunodeficiency virus, HCV = hepatitis C virus, PrEP = pre-exposure prophylaxis, STI = sexually transmitted infection, GC = gonorrhea, CT = chlamydia, SVR = sustained virologic response

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Beetham T, Saloner B, Wakeman SE, Gaye M, & Barnett ML (2019). Access to Office-Based Buprenorphine Treatment in Areas With High Rates of Opioid-Related Mortality: An Audit Study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 171(1), 1–9. 10.7326/M18-3457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatraju EP, Grossman E, Tofighi B, McNeely J, DiRocco D, Flannery M, Garment A, Goldfeld K, Gourevitch MN, & Lee JD (2017). Public sector low threshold office-based buprenorphine treatment: outcomes at year 7. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 12(1), 7. 10.1186/s13722-017-0072-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a). Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America. https://www.cdc.gov/endhiv/docs/ending-HIV-epidemic-overview-508.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b). HIV Surveillance Report, 2018 (Updated) ; vol.31. (). http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Peacock A, Colledge S, Leung J, Grebely J, Vickerman P, Stone J, Cunningham EB, Trickey A, Dumchev K, Lynskey M, Griffiths P, Mattick RP, Hickman M, & Larney S (2017). Global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: a multistage systematic review. The Lancet Global Health, 5(12), e1192–e1207. 10.1016/s2214-109x(17)30375-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denniston MM, Jiles RB, Drobeniuc J, Klevens RM, Ward JW, McQuillan GM, & Holmberg SD (2014). Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 to 2010. Annals of Internal Medicine, 160(5), 293–300. 10.7326/m13-1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Arasteh K, Feelemyer J, McKnight C, Barnes DM, Perlman DC, Uuskula A, Cooper HLF, & Tross S (2018). Hepatitis C virus prevalence and estimated incidence among new injectors during the opioid epidemic in New York City, 2000–2017: Protective effects of non-injecting drug use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 192, 74–79. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.07.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanucchi L, Springer S, & Korthuis P (2019). Medications for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder among Persons Living with HIV. Current HIV AIDS Reports, 16(1), 1–6. 10.1007/s11904-019-00436-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson BA, Morano JP, Walton MR, Marcus R, Zelenev A, Bruce RD, & Altice FL (2017). Innovative Program Delivery and Determinants of Frequent Visitation to a Mobile Medical Clinic in an Urban Setting. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 28(2), 643–662. 10.1353/hpu.2017.0065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourounis G, Richards BDW, Kyprianou E, Symeonidou E, Malliori M, & Samartzis L (2016). Opioid substitution therapy: Lowering the treatment thresholds. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 161, 1–8. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk N, Mojtabai R, Stuart EA, Fingerhood M, Agus D, Lyons BC, Weiner JP, & Saloner B (2020). Opioid agonist treatment and fatal overdose risk in a state-wide US population receiving opioid use disorder services. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 10.1111/add.14991 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk N, Buresh M, Gordon MS, Blue TR, Fingerhood MI, & Agus D (2019). Expanding low-threshold buprenorphine to justice-involved individuals through mobile treatment: Addressing a critical care gap. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 103, 1–8. 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low AJ, Mburu G, Welton NJ, May MT, Davies CF, French C, Turner KM, Looker KJ, Christensen H, McLean S, Rhodes T, Platt L, Hickman M, Guise A, & Vickerman P (2016). Impact of Opioid Substitution Therapy on Antiretroviral Therapy Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 63(8), 1094–1104. 10.1093/cid/ciw416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryland Department of Health. (2019). Unintentional Drug- and Alcohol-Related Intoxication Deaths in Maryland, 2018. (). https://health.maryland.gov/vsa/Documents/Overdose/Annual_2018_Drug_Intox_Report.pdf

- Maryland Department of Health. (2020). Opioid Treatment Programs. https://bha.health.maryland.gov/Documents/OTP%20Program%20Brief_Rv2.13.20.pdf.

- Mistler CB, Copenhaver MM, & Shrestha R (2020). The Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Care Cascade in People Who Inject Drugs: A Systematic Review. AIDS and Behavior, 10.1007/s10461-020-02988-x [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). A national strategy for the elimination of hepatitis B and C. (). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton BL, Beitin A, Glenn M, DeLuca J, Litwin AH, & Cunningham CO (2016). Retention in buprenorphine treatment is associated with improved HCV care outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 75, 38–42. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne BE, Klein JW, Simon CB, James JR, Jackson SL, Merrill JO, Zhuang R, & Tsui JI (2019). Effect of lowering initiation thresholds in a primary care-based buprenorphine treatment program. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 200, 71–77. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal ES, Silk R, Mathur P, Gross C, Eyasu R, Nussdorf L, Hill K, Brokus C, D'Amore A, Sidique N, Bijole P, Jones M, Kier R, McCullough D, Sternberg D, Stafford K, Sun J, Masur H, Kottilil S, & Kattakuzhy S (2020). Concurrent Initiation of Hepatitis C and Opioid Use Disorder Treatment in People Who Inject Drugs. Clinical Infectious Diseases : An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 10.1093/cid/ciaa105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, Indave BI, Degenhardt L, Wiessing L, Ferri M, & Pastor-Barriuso R (2017). Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 357, j1550. 10.1136/bmj.j1550 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulkowski MS, & Thomas DL (2005). Epidemiology and natural history of hepatitis C virus infection in injection drug users: implications for treatment. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 40(8), S263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. AHEAD: America's HIV Epidemic Analysis Dashboard. (2020). https://ahead.hiv.gov/indicators/

- Wakeman SE, Larochelle MR, Ameli O, Chaisson CE, McPheeters JT, Crown WH, Azocar F, & Sanghavi DM (2020). Comparative Effectiveness of Different Treatment Pathways for Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA Network Open, 3(2), e1920622. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward KM, McCormick SD, Sulkowski M, Latkin C, Chander G, & Falade-Nwulia O (2020). Perceptions of Network Based Recruitment for Hepatitis C Testing and Treatment among Persons Who Inject Drugs: a Qualitative Exploration. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 88, 103019. S0955-3959(20)30357-1 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson RG, Kim HK, Windsor TA, & Mareiniss DP (2016). The Opioid Epidemic in the United States. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America, 34(2), e1–e23. 10.1016/j.emc.2015.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]