Abstract

There are many reasons that push Yemenis not to take the Corona vaccine, as the deteriorating health and living reality as a result of the war and the destruction that afflicted the country created a state of ignorance and backwardness and prevented the arrival of awareness and education campaigns regarding the importance, effectiveness and safety of taking the vaccine, all of which put the Yemeni people in a state of hesitation, fear and Ignorance about the risks of not taking the vaccine.

Keywords: Indigenous people, Yemen, COVID-19 vaccine, Vaccine hesitancy

Dear editor:

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 pandemic has been ongoing for more than a year. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID 19) was initially reported by the World Health Organization (WHO) on December 31, 2019, and a global pandemic was proclaimed on March 11, 2020 [1].

The first COVID-19 case was recorded in Yemen in April 2020, and the WHO warned of a potentially catastrophic outbreak [2]. since the country is in the midst of a severe humanitarian catastrophe. Early epidemiological statistics revealed a significant death rate in those under the age of 60 [3].

Misdiagnoses and underestimating of new cases have resulted in variations in reported case counts due to a lack of well-equipped laboratories, infrastructure, and testing methods. Indeed, a recent geographic examination of burial activities in the governorate of Aden during the pandemic revealed that COVID-19 had a significant, under-reported impact, meaning that stated mortality figures are erroneous.) [4], the total number of recorded positive COVID19 cases as of March 17th, 2021 was ‘only’ 2973, all from southern governments [5].

Vaccine hesitancy is a word that describes a person's hesitation or reluctance to take immunization despite the fact that vaccination services are available [6]. The present acceptance of vaccine apprehension is a well-known phenomenon that has accompanied vaccination from its scientific origin [[7], [8], [9]].

In the case of the COVID-10 vaccine in Yemen, multiple barriers to vaccination exist, including vaccine apprehension as well as a lack of vaccine doses available to those in need and vaccine distribution that is limited in some jurisdictions and disrupted by the conflict.

Yemen has received 360 000 doses of AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccinations as the first batch under the COVAX programme, according to the WHO Yemen Situation Report for March 2021. The immunisation programme was launched on April 20th (covering 13 governorates). In Taiz, Marib, Aden, Shabwa, and Hadramawt, the vaccination was distributed [5].

Healthcare personnel, persons aged 55 and up, people with comorbidities, and social groups unable to adopt physical distance, such as internally displaced people and refugees, are priority groups during the first phase of the Yemen Covid-19 National Vaccination Plan [10]. However, as of May 29, 2021, little over 104 000 individuals have gotten at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, according to the OurWorldInData COVID-19 vaccinations dashboard, while many people in Yemen began to exhibit vaccine reluctance.

The second shipment arrived in August 2021, containing 151 000 doses of Johnson & Johnson's COVID-19 vaccine (JNJ.N). Yemen got its third batch of COVID-19 vaccine from the COVAX global vaccination exchange initiative on September 23 [10].

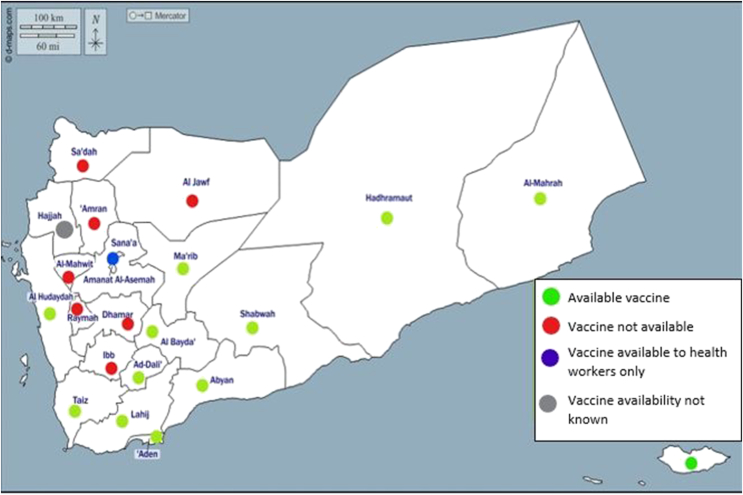

True, persistent violence, large-scale displacement, natural catastrophes, an overheated economy, and a frail, fragmented health system will amplify the effect of the COVID-19 epidemic at all levels. In a country where barely half of the health-care facilities are completely operational, Severe constraints in testing capacity and supplies — indicating substantial financing and logistical gaps as a result of the prolonged conflict and the closure of air and seaports – imply that vaccination coverage will be difficult to achieve in the future [11]. Following the 2011 uprising in Yemen, the nation was torn apart by a succession of political upheavals and cycles of violence [Fig. 1].

Fig. 1.

The map of Yemen that shows distribution the neglected regions which didn't receive any vaccine for covid-19 pandemic."We have got a permission to include this figure in the manuscripthttps://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car = 5196&lang = ar".

The plan calls for vaccinations to be delivered to the North's authorities for distribution in regions under their jurisdiction, including as Sanaa, Ibb Governorate, and Hodeida Governorate. North Korean officials have refused to allow any vaccinations to enter the country, claiming that the epidemic is an international plot. As a result, immunizations are limited to the southern states [10].

The Ministry of Health in Hadi-controlled regions was busy debunking reports about the vaccine's adverse effects, which were making many Yemenis hesitant to take it. Then, on May 20, Saudi Arabia declared that any Yemeni worker without a vaccination card would be denied admission. This prompted a stampede to vaccination clinics and pressure on the Ministry of Health to supply the required dosages so that the enormous number of Yemenis working abroad may resume their lives [12].

Furthermore, the international community should see Yemen differently in light of COVID-19, immunisation, and conflict for two reasons. To begin, at a worldwide basis, and particularly in high-income nations, the elderly and those with comorbidities were identified as the demographic most at danger from the pandemic. However, the relocation of almost 4 million people since the conflict began, many of whom have been uprooted several times, has had a negative impact on people's mental and physical health. Today, 20.7 million Yemenis, or two out of every three Yemenis, require humanitarian and security help. 12.1 million individuals are in desperate need. 34 The inhabitants of Yemen are highly vulnerable to COVID-19 and infectious illnesses since these locations frequently lack basic facilities, are congested, and have substandard housing conditions [13].

The public's ignorance and desire to get vaccinated against COVID 19 and its vaccine are crucial factors in vaccination.

Furthermore, concerns that COVID-19 vaccinations might cause infertility, restricting human population expansion, gained traction on social media [14,15]. Such unsubstantiated allegations have propagated on various social media platforms, and they can have a significant detrimental influence on the general public's perception of potential vaccinations [[16], [17], [18]]. Concerns about vaccination safety and adverse effects were among the factors that made people reluctant to be vaccinated. On the other side, a research conducted to analyses people's desire to get vaccinations found that many participants would accept the vaccine if it was given to them for free, but that vaccination acceptability declined if they had to pay for it [17,18,19].

Ethical approval

N\A.

Sources of funding

There is no any funding source.

Aisha Abdulaziz Almoughales: contributed in writing letter.

Sarya Swed: contributed in reviewing the letter.

Bisher Sawaf: contributed in reviewing the letter.

Hidar Alibrahim; contributed in writing letter and revising.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Sarya Swed.

Consent

N/A.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Reuben R.C., Danladi M.M.A., Saleh D.A., Ejembi P.E. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: an epidemiological survey in North-Central Nigeria. J. Community Health. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00881-1. [cited 17 Dec 2020] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghobari M. War-ravaged Yemen confirms first coronavirus case, braces for more. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-healthcoronavirus-yemen-case/war-ravaged-yemenconfirms-first-coronavirus-case-braces-formore-idUSKCN21S0EI April 10, 2020. June 3, 2021.

- 3.Al-Waleedi A.A., Naiene J.D., Thabet A.A.K., et al. The first 2 months of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in Yemen: analysis of the surveillance data. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koum Besson E.S., Norris A., Bin Ghouth A.S., et al. Excess mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic: a geospatial and statistical analysis in Aden governorate, Yemen. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO . 2021. WHO Yemen Update Situation report -Issue no.3 (March 2021)https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/who-yemenupdate-situation-report-issue-no3-march%202021https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/who-yemenupdate-situation-report-issue-no3-march2021https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/who-yemenupdate-situation-report-issue-no3-march2021 May 9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacDonald N.E. SAGE working group on vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33:4161–4164. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poland G.A., Jacobson R.M. The age-old struggle against the antivaccinationists. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:97–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1010594. ([CrossRef] [PubMed]) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliver J.E., Wood T. Medical conspiracy theories and health behaviors in the United States. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014;174:817–818. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.190. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salali G.D., Uysal M.S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is associated with beliefs on the origin of the novel coronavirus in the UK and Turkey. Psychol. Med. 2020;10:1–3. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720004067. ([CrossRef]) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yemen: Houthis Risk Civilians' Health in Covid-19, Human Right Watch, posted in 1 Jun 2021 Originally published in 1 Jun 2021, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-houthis-risk-civilians-health-covid-19. (accessed October 19, 2021).

- 11.WHO Universal health coverage in Yemen. 2020. https://apps.who.int/uhc/en/countries/yem/ [Internet] [cited 2020 Apr 19]. Available from: October 19, 2021.

- 12.In Search of a COVID-19 Vaccine in Yemen. Conspiracy Theories, Misinformation and Houthi Refusals to Vaccinate People in Areas under Their Control Mean that Yemenis Are Struggling to Get a Dose, Najm aldain Qasem, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/north-africa-west-asia/in-search-of-a-covid-19-vaccine-in-yemen/.

- 13.United Nations . 2019. Office for the Coordination of humanitarian Affairs, (OCHA), Yemen:https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-2019-humanitarian-needs-overview Humanitarian Needs Overview [Internet], 2019. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimmermann P., Curtis N. Coronavirus infections in children including COVID-19, Pediatr. Inf. Disp. J. 2020 Mar doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emergency Nutrition Network (ENN) A Briefing Note for Policy Makers and Programme Implementers; 2018. Child Wasting and Stunting: Time to Overcome the Separation. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romer D., Jamieson K.H. Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the US. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020;263:113356. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113356. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uscinski J.E., Enders A.M., Klofstad C., Seelig M., Funchion J., Everett C., Wuchty S., Premaratne K., Murthi M. Why do people believe COVID-19 conspiracy theories? Harv. Kennedy Sch. Misinf. Rev. 2020 https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/why-do-people-believe-covid-19-conspiracy-theories/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shahsavari S., Holur P., Wang T., Tangherlini T.R., Roychowdhury V. Conspiracy in the time of corona: automatic detection of emerging COVID-19 conspiracy theories in social media and the news. J. Comput Soc. Sci. 2020;3:1–39. doi: 10.1007/s42001-020-00086-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed W., Vidal-Alaball J., Downing J., Lopez Segui F. COVID-19 and the 5G conspiracy theory: social network analysis of Twitter data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22 doi: 10.2196/19458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]