Abstract

Purpose

Speech-language pathologists are responsible for providing culturally and linguistically responsive early language intervention services for legal, ethical, and economic reasons. Yet, speech-language pathologists face challenges in meeting this directive when children are from racial, ethnic, or linguistic backgrounds that differ from their own. Guidance is needed to support adaptation of evidence-based interventions to account for children's home culture(s) and language(s). This review article (a) describes a systematic review of the adaptation processes applied in early language interventions delivered to culturally and linguistically diverse populations in the current literature and (b) offers a robust example of an adaptation of an early language intervention for families of Spanish-speaking Mexican immigrant origin.

Method

Thirty-three studies of early language interventions adapted for culturally and linguistically diverse children ages 6 years and younger were reviewed. Codes were applied to describe to what extent studies document the purpose of the adaptation, the adaptation process, the adapted components, and the evaluation of the adapted intervention.

Results

Most studies specified the purpose of adaptations to the intervention evaluation, content, or delivery, which typically addressed children's language(s) but not culture. Study authors provided limited information about who made the adaptations, how, and when. Few studies detailed translation processes or included pilot testing. Only one used a comprehensive framework to guide adaptation. A case study extensively documents the adaptation process of the Language and Play Every Day en español program.

Conclusions

Future early language intervention adaptations should focus on both linguistic and cultural factors and include detailed descriptions of intervention development, evaluation, and replication. The case study presented here may serve as an example. Increased access to such information can support research on early language interventions for diverse populations and, ultimately, responsive service provision.

Many young children who speak a language or language variety other than standardized American English and/or whose family members identify with a minority ethnic or cultural heritage are currently served in early intervention (EI) and early childhood special education (ECSE), and the numbers are growing. According to the National Center for Educational Statistics (2018), the percentage of 3- to 5-year-old children enrolled in Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) Part B services who were not White rose from nearly 38%–48% between the years 2000 and 2018. In 2019, most of these children were identified as Hispanic/Latinx (52.1%), followed by Black/African American (27.6%), multiracial (9.0%), Asian (8.5%), American Indian/Alaskan Native (2.3%), and Pacific Islander (0.5%). Similarly, children ages birth to 3 years who were not White made up approximately 48% of children served by IDEA Part C in 2017 (U.S. Department of Education, 2020). Thus, the field of speech-language pathology must be prepared to deliver evidence-based interventions that support the needs of young culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) children in EI/ECSE.

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) are responsible for delivering early communication interventions that are culturally and linguistically responsive to children and families from any background (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association [ASHA], 2008). Such interventions incorporate families' beliefs, values, practices, and context, as informed by their cultural background(s), as well as support the development of families' home language(s) and/or language varieties in addition to standardized American English. Emerging research suggests that early language and literacy interventions that are culturally and linguistically responsive result in more promising child outcomes than interventions that are not (Durán, Hartzheim, et al., 2016; Larson et al., 2020). Yet, Larson et al. (2020) found that less than a quarter (n = 12) of language interventions delivered to CLD children between birth and age 6 years over the previous 4 decades were both culturally and linguistically responsive. The paucity of information on responsive interventions may contribute to the challenges SLPs report in serving individuals whose culture, race, or language differ from their own, especially individuals who speak languages other than English (Caesar, 2013; D'Souza et al., 2012; Guiberson & Atkins, 2012; Kritikos, 2003; Teoh et al., 2017; Williams & McLeod, 2012). Therefore, this review article provides details on adaptations to early language interventions for CLD children in the current literature. We also provide a detailed example of a rigorous cultural and linguistic adaptation process to enhance an early language intervention for families of Spanish-speaking Mexican immigrant background. Together, this information will support researchers' ability to adapt interventions and thereby advance the evidence base so clinicians can improve responsive practice with CLD populations.

Rationale for Cultural and Linguistic Adaptation

There are specific legal, ethical, and economic arguments for creating culturally and linguistically responsive early language and literacy interventions. Federal law in the United States mandates that service provision to young children should minimize cultural and linguistic biases and be individualized to meet the needs of the family and child (IDEA, 2004). This requires that we do not take a “one size fits all” approach and, instead, adapt and tailor our interventions to the language and cultural context of the child and family. To be clear, this individualization should be done for all children, including those whose language, race, ethnicity, and/or culture matches the population with whom the intervention was originally developed and especially those whose do not. In addition, we are bound by ethical principles outlined by our governing agencies to consider cultural and linguistic adaptations that ensure equitable and respectful service provision for people of all backgrounds (ASHA, 2016; DEC Code of Ethics, 2009). For example, ASHA is clear that clinicians “shall not discriminate in the delivery of professional services or in the conduct of research and scholarly activities on the basis of race, ethnicity, sex, gender identity/gender expression, sexual orientation, age, religion, national origin, disability, culture, language, or dialect” (ASHA, 2016). Finally, ensuring that our interventions are not only effective but also culturally and linguistically responsive to the needs of children and families will, over time, require less economic resources to execute than interventions that are not. Well-adapted interventions may enhance adherence to the treatment program, engagement, family satisfaction, and retention (e.g., Bailey et al., 1999; García Coll et al., 2002; Holden et al., 1990; Kumpfer et al., 2002) while also promoting child outcomes in all developing languages (Durán, Hartzheim, et al., 2016; Larson et al., 2020). Families' perceptions of the appropriateness of early language interventions have been shown to influence fidelity of implementation and, resultantly, the degree to which the intervention enhances child language skills (Dunst et al., 2016). Thus, implementing early language and literacy interventions that are adapted to the cultures and languages of children and their families meets our professional directives and promotes healthy child development.

Describing Cultural and Linguistic Adaptations

Despite the need to conduct adaptations, there is no published guidance to date that offers language and literacy researchers a well-specified process for adapting interventions or documenting the adaptation process. Adaptation frameworks available in the public and mental health literature specify key features of adaptation processes with broad applicability (Escoffery et al., 2019). These include assessing community needs and existing evidence-based interventions, selecting an intervention to meet community needs, consulting with stakeholders, developing adaptations systematically and collaboratively, training staff on the adapted intervention, pilot testing the adapted intervention to generate additional modifications, and evaluating the fully adapted intervention. When researchers document these important details about the intervention adaptation process, it supports further development, replication, and evaluation of adapted interventions and, relatedly, implementation by practicing SLPs (e.g., Chambers & Norton, 2016; Escoffery et al., 2018). Sharing specific adaptations made for particular populations and their success facilitates our understanding of which adaptations are relevant and which should be avoided (Stirman et al., 2013). In particular, studies published on intervention adaptations should record the reason for adaptation, who made the adaptations, the timing of the adaptation (i.e., before, during, after the intervention), and what was adapted (i.e., intervention content, context, and/or training and evaluation) at each level of delivery (e.g., individual patient level, system level; Escoffery et al., 2018; J. E. Moore et al., 2013; Stirman et al., 2013). Describing how the intervention was translated into non–English languages (if applicable) and evaluated (e.g., pilot testing for social validity, outcomes) may also support further research. To date, a systematic review of the documented application of the key features of adaptation to early language interventions has not been available to support researchers and clinicians undertaking this critical work. This study meets this need.

Purpose of the Study

Given many reasons for careful adaptations of language and literacy interventions for young children from CLD backgrounds, the field may benefit from knowing how adaptations to early language interventions have been developed and documented in the past. To serve this purpose, this systematic literature review was designed to answer the following research question: To what extent do published studies on early language and/or literacy interventions delivered to CLD populations document the purpose of the adaptation, the adaptation process (i.e., who adapted, when, what, and how), and the evaluation of the adapted intervention (i.e., pilot testing)? Following the results of our review, we present a case study that documents the application of a rigorous multiphase adaptation process to an evidence-based early language intervention. Specifically, we focus on the adaptation of a caregiver-implemented naturalistic communication intervention (CI-NCI) for young children with language delays and their caregivers from Spanish-speaking Mexican immigrant backgrounds. Although these interventions are a common evidence-based approach for young children with communication needs, the vast majority of research on CI-NCIs has not been conducted with CLD populations (Akamoglu & Meadan, 2018; Larson et al., 2020). As such, we sought to adapt the intervention and share the details of our process to support research on intervention development. Clinicians engaged in direct service provision may find this example helpful for providing general guidance on what to consider when individualizing interventions for particular families.

Method

Identification of Studies for the Systematic Review

A total of 127 articles were initially identified for consideration via a four-step process. First, references were gathered from recent systematic research syntheses that comprehensively reviewed the published literature on early language and/or literacy interventions provided to children from CLD backgrounds with and without language disorders under the age of 6 years (Durán, Hartzheim, et al., 2016; Guiberson & Ferris, 2019; Hur et al., 2020; Larson et al., 2020). Collectively, these syntheses focused on studies published in English in peer-reviewed journals between 1971 and 2018. This returned a total of 38 articles. Second, we conducted an updated electronic search with bibliographic databases and Google Scholar. We searched Academic Search Premier, PsycNet, and ERIC for articles published in 2019 and 2020 in English in peer-reviewed journals using search terms from Durán, Hartzheim, et al. (2016) with minor adaptations: (child* or preschool* or “early childhood”) in combination with (bilingual* or multilingual* or “dual language learn*” or “Spanish speak*” or “home language” or “English language learn*”), (“language impair*” or “language delay” or “language disorder*” or “at-risk”), and (“early interv*” or strateg* or intervene* or "language interv*" or "literacy interv*”). Once duplicates were eliminated, we reviewed titles and abstracts for relevancy. This search yielded 20 additional articles. Four additional articles were identified from a title and abstract review of 24 citations returned by Google Scholar (Advanced Scholar Search option). For this search, we restricted the year of publication to 2019 and 2020 and used terms that conformed with Google Scholar's search settings by title and relevance: intervention OR “language intervention” OR “literacy intervention” AND child OR preschool OR “early childhood” OR bilingual OR multilingual OR “dual language learner” OR “Spanish speaker” OR “home language” OR “English language learner.” One article was added by author recommendation (i.e., Durán, Gorman, et al., 2016).

Third, the first and second authors independently reviewed the full text of these 63 articles for inclusion. Studies were included if the intervention was (a) focused on impacting the language and/or literacy of children from CLD backgrounds with or without language disorders between birth and age 6 years (i.e., studies testing how children acquired language and/or literacy were excluded), (b) adapted from an existing evidence-based intervention or included evidence-based intervention strategies (i.e., not a new untested intervention created for the target population), and (c) delivered in individual or small group formats (i.e., comparisons of classroom curricula were excluded). As defined by Bernal et al. (2009), cultural adaptation “is the systematic modification of an evidence-based treatment or intervention protocol to consider language, culture, and context in such a way that it is compatible with the client's cultural patterns, meanings, and values” (p. 362). Therefore, sufficient evidence of linguistic and/or cultural adaptation was required for a study to be included such that we excluded studies for which the only adaptations described were direct translation of the original intervention and/or accommodations to test in the non–English language. Agreement on eligibility was achieved by consensus. Based on these criteria, 28 articles were excluded. Five additional studies were excluded because the authors described a re-analysis of data from studies already included in the review (i.e., Farver et al., 2009; Matera & Gerber, 2008; Méndez et al., 2015; van Tuijl et al., 2001) or a replication study of an intervention (Magaña et al., 2017). This resulted in a total of 30 studies that qualified for this systematic review.

Our fourth and final step for identifying articles to review entailed an ancestral hand search of the reference lists of each of the 30 aforementioned studies for studies that potentially met our inclusionary criteria. This returned 64 studies for consideration once duplicates were eliminated. We used the title and abstract to determine if the cited study met our inclusionary criteria (as described above), and two authors reviewed the full text of the article when the title and abstract provided insufficient information to determine inclusion by consensus. Sixty-one studies were eliminated while three met inclusionary criteria. In total, we reviewed 33 studies for this study. See Table 1 for a description of each of the studies reviewed.

Table 1.

Description of intervention studies reviewed (N = 33) and adaptation type.

| Study | Intervention | Targeted participants | Adaptation type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binger et al. (2008) | Caregiver instructional program to support child use of AAC | English-speaking Latino/a caregivers of children who used AAC | Cultural |

| Boyce et al. (2010) | Storytelling for the Home Enrichment of Language and Literacy Skills (SHELLS) | Spanish-speaking immigrant families with children in Migrant Head Start | Cultural and linguistic |

| Collins (2010) | Book reading with embedded vocabulary instruction | Portuguese-speaking preschool-aged children with TLD | Cultural and linguistic |

| Cooke et al. (2009) | Audio prompting to support parents to teach English vocabulary | Spanish-speaking immigrant families with preschool-aged children with TLD | Linguistic |

| Durán, Gorman, et al. (2016) | Read It Again Dual Language and Literacy Curriculum (RIA-DL) | Spanish–English bilingual children in Head Start and Migrant Head Start | Cultural and linguistic |

| Farver et al. (2009) | Literacy Express Preschool Curriculum | Spanish-speaking children in Head Start who did not have support for speech/language | Linguistic |

| Gutiérrez-Clellen et al. (2012) | Academic enrichment program focused on academic readiness | Spanish-speaking Latino children with specific language impairment in preschool | Linguistic |

| Hammer & Sawyer (2016) | Parent-implemented interactive book reading | Spanish-speaking Latina mothers of children in Head Start | Cultural and linguistic |

| Huennekens & Xu (2010) | Dialogic reading with parent support | 4-year-old English language learners in Head Start | Linguistic |

| Ijalba (2015) | Parent-implemented interactive book reading with specific language facilitating strategies | Spanish-speaking mothers of children with language delays in preschool | Cultural and linguistic |

| Johnson et al. (2012) | Israeli Home Instructional Program for Preschool Youngsters (HIPPY) | Families of young children from communities with a variety of risk factors | Cultural and linguistic |

| Leacox & Jackson (2014) | Technology-enhanced vocabulary instruction in shared book readings | Preschool- and kindergarten-aged English language learners in migrant education program | Linguistic |

| Lim & Cole (2002) | Parent-implemented interactive book reading using specific language facilitation techniques | Korean-speaking mothers and their 2- to 4-year-old children with TLD | Cultural and linguistic |

| Lugo-Neris et al. (2010) | Vocabulary instruction in shared storybook reading | Spanish-speaking children with TLD and limited English in migrant education program | Linguistic |

| Magaña et al. (2017) | Psychoeducational parent training program | Spanish-speaking Latina immigrant mothers of children with ASD | Cultural and linguistic |

| Matera & Gerber (2008) | Project WRITE! literacy curriculum with a focus on writing | Spanish-speaking children in Head Start | Cultural and linguistic |

| McDaniel et al. (2019) | Storybook reading with embedded vocabulary instruction | Spanish- and English-speaking children with hearing loss in specialized preschool | Linguistic |

| Meadan et al. (2020) | Caregiver-implemented communication intervention | Spanish-speaking families with young children with ASD and developmental disabilities | Cultural and linguistic |

| Méndez et al. (2015) | Vocabulary instruction in shared booked reading | Spanish-speaking children with typical vocabulary development in Head Start | Cultural and linguistic |

| Mesa & Restrepo (2019) | Family Reading Intervention for Language and Literacy in Spanish (FRILLS) | Spanish-speaking Latino families of children without identified developmental concerns in Head Start | Cultural and linguistic |

| Peredo et al. (2017) | Enhanced Milieu Teaching en Español | Spanish-speaking families of 30- to 43-month-old children with language impairment from low-income homes | Cultural and linguistic |

| Pollard-Durodola et al. (2016) | Project Words of Oral Reading and Language Development (WORLD) | Spanish-speaking children with limited English in dual language preschools | Linguistic |

| Pratt et al. (2015) | ¡Leamos Juntos!: parent–child shared book reading with print referencing | Monolingual Spanish-speaking Mexican mothers and their 42- to 84-month-old children (M age = 5;11 [years;months]) with primary language impairment | Linguistic |

| Restrepo et al. (2010) | Supplemental instruction for oral language and preliteracy skills | Spanish-speaking children without developmental concerns in English-only preschool | Linguistic |

| Restrepo et al. (2013) | Vocabulary instruction in dialogic book reading | Spanish-speaking children with TLD and with language impairment in preschool | Linguistic |

| Roberts (2008) | Storybook reading with parent support | Spanish- or Hmong-speaking families from low-income backgrounds with children in preschool | Linguistic |

| Saracho (2010) | Multifaceted literacy intervention literacy with parent and teacher support | Hispanic fathers of 5-year-olds in public kindergarten and kindergarten teachers | Cultural and linguistic |

| Spencer et al. (2013) | Story Champs | Children with disabilities from non-White backgrounds in preschool | Linguistic |

| Spencer et al. (2019) | Story Champs | Spanish-speaking children in Head Start | Linguistic |

| Spencer et al. (2020) | Puente de Cuentos: multitiered narrative intervention | Spanish-speaking children at risk for poor narrative development in Head Start | Linguistic |

| Thordardottir et al. (1997) | Targeted vocabulary instruction | Icelandic- and English-speaking toddler with language delay | Linguistic |

| Tsybina & Eriks-Brophy (2010) | Dialogic book reading with parent support | Spanish–English bilingual preschool-aged children with expressive vocabulary delays and their mothers | Cultural and linguistic |

| van Tuijl et al. (2001) | Israeli Home Instructional Program for Preschool Youngsters (HIPPY) | Turkish and Moroccan immigrant families with low parental education and 4- to 5-year old children | Cultural and linguistic |

Note. TLD = typical language development; ASD = autism spectrum disorder; AAC = augmentative and alternative communication.

Coding Approach

These 33 studies were coded to provide descriptive information on the general purpose of the study: the characteristics of the original intervention (i.e., description of the intervention program or intervention strategies to be adapted, target participants), and the authors' description of the adaptation process. Specific to the description of the adaptation process, a coding scheme was developed based on existing classification schemes for cultural and linguistic adaptations to evidence-based interventions (Escoffery et al., 2018; J. E. Moore et al., 2013; Stirman et al., 2013). See Table 2 for an overview of elements coded to describe the adaptation process. Note that, in applying the codes, we recognized that authors may have applied key adaptation features to develop their interventions but did not report all relevant details in the published study.

Table 2.

Results of coding for documenting adaptations.

| Study | Adaptation purpose? | Adaptation framework? | Adaptation timing? | Who adapted? | How adaptations were determined? | What components were adapted? | How was translation completed? | Was pilot testing completed? | If yes, how pilot testing informed intervention development? | Were social validity data collected? | Were outcomes data collected? | Access to intervention materials? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binger et al. (2008) | + | + | + | + | N/A | N/A | + | + | ||||

| Boyce et al. (2010) | + | N/A | + | + | ||||||||

| Collins (2010) | + | + | N/A | N/A | + | + | ||||||

| Cooke et al. (2009) | + | N/A | N/A | + | + | |||||||

| Durán, Gorman, et al. (2016) | Somewhat | + | + | Somewhat | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Farver et al. (2009) | + | + | N/A | + | ||||||||

| Gutiérrez-Clellen et al. (2012) | + | + | N/A | + | + | |||||||

| Hammer & Sawyer (2016) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| Huennekens & Xu (2010) | + | + | + | N/A | + | + | Somewhat | |||||

| Ijalba (2015) | + | + | + | + | + | N/A | + | + | + | |||

| Johnson et al. (2012) | + | N/A | + | |||||||||

| Leacox & Jackson (2014) | + | Somewhat | + | + | + | |||||||

| Lim & Cole (2002) | + | + | N/A | + | + | + | ||||||

| Lugo-Neris et al. (2010) | + | + | N/A | + | + | |||||||

| Magaña et al. (2017) | + | + | + | + | + | + | Somewhat | + | + | + | ||

| Matera & Gerber (2008) | + | + | N/A | + | + | |||||||

| McDaniel et al. (2019) | + | + | N/A | + | + | |||||||

| Meadan et al. (2020) | + | Somewhat | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Méndez et al. (2015) | + | + | + | + | N/A | + | + | |||||

| Mesa & Restrepo (2019) | + | + | N/A | + | + | + | ||||||

| Peredo et al. (2017) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Pollard-Durodola et al. (2016) | + | N/A | + | |||||||||

| Pratt et al. (2015) | + | N/A | + | + | ||||||||

| Restrepo et al. (2010) | + | N/A | + | |||||||||

| Restrepo et al. (2013) | + | + | N/A | + | + | |||||||

| Roberts (2008) | + | + | N/A | + | + | |||||||

| Saracho (2010) | + | N/A | + | |||||||||

| Spencer et al. (2013) | + | N/A | + | + | + | |||||||

| Spencer et al. (2019) | + | + | N/A | + | ||||||||

| Spencer et al. (2020) | + | + | N/A | + | ||||||||

| Thordardottir et al. (1997) | + | + | N/A | + | + | |||||||

| Tsybina & Eriks-Brophy (2010) | + | + | N/A | + | + | + | ||||||

| van Tuijl et al. (2001) | + | + | + | + | N/A | + | + |

Note. + indicates that authors provided this information explicitly; N/A = not applicable.

We coded whether the study authors explicitly stated why adaptations were made (i.e., adaptation purpose), which adaptation framework guided the adaptations, when the adaptations were made (i.e., adaptation timing), by whom the adaptations were made, how the adaptations were determined, what components of the intervention were adapted, how translation was completed (if applicable), and whether the adapted intervention was pilot tested with representative stakeholders and data on social validity and/or outcomes of the adapted intervention were collected. When social validity data were collected, we recorded who provided these data using which methods at what time point of intervention delivery (i.e., before, during, after). We also coded whether intervention materials were provided in the article (e.g., target word lists for vocabulary interventions, book lists for dialogic reading interventions), as access to materials is likely to increase clinical implementation. In cases where the authors documented consultation on the adaptation, we recorded who specifically consulted on the adaptation (i.e., intervention providers, community members) to characterize the nature of consultation within the research base. We further categorized any description of the intervention components that were adapted, using definitions modified from Stirman et al. (2013): content (i.e., materials, targets, content), delivery (i.e., how the intervention is delivered), context (i.e., format, setting, or personnel), training (i.e., how intervention implementers are trained), and evaluation (i.e., how the outcomes of the intervention are evaluated). Additional details are found in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 3.

Description of intervention consultants described by study authors.

| Study | Consultants |

|---|---|

| Binger et al. (2008) | 2 Latino SLP professors, 1 AAC expert, 1 Latino father of child who used AAC |

| Hammer & Sawyer (2016) | 17 Latina mothers from the community where the research took place |

| Ijalba (2015) | Spanish-speaking Mexican and Dominican mothers who participated in the intervention |

| Magaña et al. (2017) | Staff from community-based organization, 1 educational consultant, Latino parents of children with ASD |

| Méndez et al. (2015) | Native Spanish speakers of Mexican origin from low-income backgrounds |

| Mesa & Restrepo (2019) | Mothers who participated in the intervention |

| Peredo et al. (2017) | 4 Spanish–English bilingual providers (3 of whom were Hispanic), Spanish-speaking Mexican mothers who participated in the intervention |

| Thordardottir et al. (1997) | Child's parents from Iceland who spoke Icelandic |

| Tsybina & Eriks-Brophy (2010) | Mothers who participated in the intervention |

Note. The terms authors used to describe consultants are used here. SLP = speech-language pathology; AAC = augmentative and alternative communication; ASD = autism spectrum disorder.

Table 4.

Descriptions of the intervention components that were adapted.

| Study | Content | Delivery | Training | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binger et al. (2008) | (a) Related program to Latino cultural values and educational success; (b) selected books with everyday themes; (c) changed expectations for delivery of language facilitation strategies | — | Relabeled training program as “instructional program” | — |

| Boyce et al. (2010) | (a) No requirement for particular cultural narrative style; (b) formal literacy skills not required to participate | (a) Activities could be delivered in any language; (b) home visitors spoke Spanish | — | (a) Maternal measures available in Spanish; (b) Spanish-speaking assessors read forms aloud to mothers; (c) children assessed in Spanish or English |

| Collins (2010) | Selected culturally relevant books | — | — | Measured child vocabulary in Portuguese and English |

| Cooke et al. (2009) | (a) Developed target words in Spanish and English; (b) audio prompting provided in Spanish and English | — | Training with mothers facilitated with support of Spanish–English interpreter | (a) Measured child vocabulary in both languages; (b) parent interviews supported by Spanish–English interpreter |

| Durán, Gorman, et al. (2016) | (a) Spanish and English lessons linked; (b) selected culturally relevant books and similar vocabulary targets in Spanish and English; (c) embedded intentional strategies to support vocabulary acquisition in both languages | (a) Intervention could be delivered in Spanish or English; (b) some bilingual Spanish–English teachers delivered the intervention | Training included information on bilingual language and literacy development | (a) Fidelity measure adapted to account for the language of intervention; (b) usability measure available in Spanish |

| Farver et al. (2009) | Developed small group activities in Spanish to parallel English curriculum | Bilingual graduate assistants delivered small group activities in Spanish | — | Child language and literacy assessed in Spanish and English by bilingual assessors |

| Gutiérrez-Clellen et al. (2012) | Selected parallel intervention books in Spanish and English | Bilingual teachers provided academic enrichment sessions in Spanish (to the intervention group), alternating with English sessions | — | Child language predictors assessed in Spanish and English (outcomes only measured in English) |

| Hammer and Sawyer (2016) | (a) Developed books with culturally relevant themes; (b) books available in English and Spanish | (a) Parents read books in Spanish to their children; (b) Spanish-speaking home visitors provided support | Home visitors trained to coach parents with soft script lesson | Child language assessed in Spanish and English by bilingual assessors |

| Huennekens & Xu (2010) | Storybooks provided in Spanish | Parents read books in Spanish to their children | Spanish–English interpreter facilitated training with mothers | |

| Ijalba (2015) | (a) Tailored content of the picture books based on the themes mothers described; (b) provided books in Spanish | — | Provided parent education meetings | Child language assessed in Spanish and English |

| Johnson et al. (2012) | — | (a) Home visitors were members of the community and similar in background; (b) sessions conducted in language preferred by parents | — | Teachers assessed children's language in English and/or Spanish if enrolled in bilingual programs |

| Leacox & Jackson (2014) | Added Spanish word definitions for intervention group | Native Spanish speaker prerecorded word definitions in Spanish for e-books | — | Children's vocabulary assessed in both languages |

| Lim & Cole (2002) | — | Mothers delivered language facilitation in Korean | Provided handout to mothers in Korean with description of language facilitation strategies | Appeared to assess child language in the language of the mother–child interaction |

| Lugo-Neris et al. (2010) | Provided vocabulary expansions in Spanish | Intervention provided by bilingual Spanish–English interventionist | — | Children's vocabulary assessed in both languages by bilingual assessors |

| Magaña et al. (2017)a | (a) Intervention materials available in Spanish and English; (b) incorporated common Spanish sayings and cultural values into manual; (c) goals were specific to the context of participants; (d) recruitment through Spanish-speaking support group of parents of children with ASD | (a) Intervention provided by Spanish speakers from similar communities who had children with ASD; (b) focused on relationship building with mothers of the families | Training for the interventionists took place near Latino neighborhood in location resourced with bilingual staff | Caregiver-focused measures available in Spanish |

| Matera & Gerber (2008) | Selected stories to be culturally and linguistically responsive | Delivered intervention sessions in Spanish and English | — | Child language assessed in Spanish and English |

| McDaniel et al. (2019) | Developed target word sets in English and Spanish | Intervention sessions with SLP provided in English or Spanish | — | Child language assessed in Spanish and English |

| Meadan et al. (2020) | Child care, transportation, and family incentives provided for each session | Bilingual interventionists with experience working in Spanish delivered sessions | — | Caregiver questionnaires and interviews completed in Spanish |

| Méndez et al. (2015) | Selected books and props selected to be culturally relevant | Intervention sessions delivered in Spanish and English (intervention group only) | — | Child language assessed in Spanish and English |

| Mesa & Restrepo (2019) | (a) Included information on bilingual language development; (b) collaborated with participating mothers to develop relevant strategies; (c) selected bilingual and Spanish language books | — | (a) Training incorporated families' existing practices and beliefs; (b) training delivered in Spanish by Spanish-speaking SLP | Child language and caregiver communication assessed in Spanish |

| Peredo et al. (2017) | Made several linguistic and cultural adaptations to language-facilitating strategies, targets, and expectations | Bilingual interventionists delivered sessions in Spanish | (a) Training materials translated to Spanish; (b) video examples created in Spanish for training | Child language and caregiver communication assessed in Spanish |

| Pollard-Durodola et al. (2016) | Target vocabulary included Spanish/English cognates | Spanish–English bilingual teachers delivered intervention with support of bilingual paraprofessionals | — | Child language assessed by Spanish–English bilingual assessors |

| Pratt et al. (2015) | Selected Spanish language books | Bilingual Spanish–English intervention staff | Training provided to parents in Spanish | Child language and literacy assessed in Spanish by native speakers of children's Spanish dialect |

| Restrepo et al. (2010) | — | (a) Provided supplementary instruction in Spanish (intervention group only); (b) instruction delivered by Spanish-speaking SLP | — | Bilingual assessors tested children's Spanish language |

| Restrepo et al. (2013) | (a) Selected books in Spanish and/or bilingual Spanish–English; (b) selected Spanish–English translation equivalents as targets | Bilingual interventionist delivered sessions in Spanish and English | — | Child language assessed in Spanish and English |

| Roberts (2008) | Made books developed in Spanish and Hmong available to families | Sent books in the home language home to be read by caregivers | (a) Provided training to caregivers for storybook reading in home languages; (b) provided child care during training | (a) Spanish-speaking children's vocabulary assessed in Spanish and English; (b) bilingual assessors from the same community as parents administered caregiver surveys |

| Saracho (2010) | (a) Selected books determined to be appropriate for children's language and culture; (b) developed culturally relevant activities to accompany the books; (c) families wrote stories in their preferred language | Fathers delivered intervention in Spanish and/or English | (a) Training included how to incorporate children's language and culture to promote literacy; (b) trainer matched families' linguistic and cultural background | — |

| Spencer et al. (2013) | Included instructions in Spanish and English for the take-home activities | — | — | Made social validity questionnaire available in Spanish |

| Spencer et al. (2019) | Developed comparable Spanish and English lessons and take-home activities | Bilingual teachers and interventionists delivered intervention in Spanish and English | — | (a) Demographic survey offered to parents in preferred language; (b) child language assessed in Spanish and English |

| Spencer et al. (2020) | (a) Created narratives in Spanish; (b) developed take-home activities in Spanish and English | Bilingual teachers and interventionists delivered intervention sessions in Spanish and English | — | Child language assessed in Spanish and English |

| Thordardottir et al. (1997) | Developed target word sets in Icelandic and English | Bilingual interventionist delivered sessions in Icelandic and English | — | Child language assessed in Icelandic and English |

| Tsybina & Eriks-Brophy (2010) | (a) Selected culturally relevant vocabulary targets in Spanish and English; (b) selected books in both languages | Delivered intervention in Spanish and English | (a) Maternal training involved practice with intervention strategies in Spanish; (b) handout provided in Spanish on strategies | Child language assessed in Spanish and English |

| van Tuijl et al. (2001) | (a) Focused on parents as children's instructors; (b) provided support and made materials accessible to parents with low literacy | (a) Recruited paraprofessional interventionists from the target communities who spoke the same languages; (b) added group meetings; (c) made program available in Dutch, Turkish, and Arabic | — | Bilingual assessors assessed child cognition and language in Dutch and home language(s) |

Note. Adaptation to content include modifications to materials, content, and/or procedures. Delivery adaptations are changes to mode, medium, or delivery of the intervention. Adaptations to training are modifications made to training interventionists. Evaluation adaptations are changes to how the intervention was evaluated. ASD = autism spectrum disorder; SLP = speech-language pathologist.

Only study to specify context adaptations (e.g., change to the intervention setting).

Finally, studies were coded for whether they represented a cultural and/or linguistic adaptation using definitions from Larson et al. (2020). Cultural adaptations were defined as efforts to incorporate “values, beliefs, practices, experiences, and materials relevant to the cultural backgrounds of the individuals receiving the interventions” (p. 158). Linguistic adaptations were defined as modifications specifically intended to support growth in children's home language(s) and/or language varieties (e.g., delivering the intervention in the home language, selecting English targets that share linguistic features with the home language).

The first author assigned codes to all studies. The second and third authors then reviewed the coding for all studies and provided feedback in the event that they disagreed. We agreed on 99% of codes and resolved disagreements through consensus. Twenty percent of studies (n = 7) were also coded independently by a reliability coder who did not code the study originally. A comparison of the codes assigned by the original coder and the reliability coder resulted in 87.9% agreement. Disagreements noted during the reliability coding process were resolved by consensus. The final codes were then summarized to provide numerical values that represent the frequency with which study authors detailed each intervention adaptation feature.

Results

See Table 2 for an overview of the coding results. Half of the 33 studies reviewed included only linguistic adaptations to the intervention (n = 16). Sixteen included cultural and linguistic adaptations, while one study was a cultural adaptation only (Binger et al., 2008). In general, interventions were adapted for preschool-aged children who spoke Spanish and/or identified as Latinx/Hispanic and were from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. One intervention each was adapted for children and/or their caregivers whose families were from Brazil, Portugal, or the Azores and spoke Portuguese (Collins, 2010), who were from Iceland and spoke Icelandic (Thordardottir et al., 1997), who were from Turkey or Morocco and spoke Turkish or Arabic (van Tuijl et al., 2001), respectively, and who spoke Korean (Lim & Cole, 2002) or Hmong (Roberts, 2008; country of origin or ethnicity unspecified). Other studies were adapted for English-speaking children from minority backgrounds in the United States (Binger et al., 2008; Spencer et al., 2013) or for children from communities considered at risk (Johnson et al., 2012). The adapted interventions primarily consisted of interactive book reading, targeted vocabulary instruction, and supplementary language and/or literacy instruction.

Purpose of Adaptation

Out of 33 studies, 22 studies specified the purpose of linguistic and/or cultural adaptation. Most commonly (n = 11), study authors explained that adaptations were needed to investigate intervention effects when delivered in the home language or to compare intervention conditions that varied by language of instruction. Other authors justified adaptation for the purposes of enhancing the fit of the intervention to the target population (n = 6), supporting children's home language development (n = 4), or examining cross-linguistic transfer (n = 1).

Adaptation Process

Only one study specified using a formal process or overarching framework to guide their adaptations (Magaña et al., 2017). Durán, Gorman, et al. (2016) documented the use of a specific framework for adapting instructional strategies, in particular, for children from dual language backgrounds. Of the 30 studies for which intervention materials were clearly translated from English into another language, only one study included a full description of the translation procedures (Roberts, 2008) while two provided a partial description (Durán, Gorman, et al., 2016; Magaña et al., 2017). Most studies did not specify when adaptations were made to the intervention (n = 27). Six studies indicated that adaptations were made prior to the intervention, whereas one study made adaptations before and during the intervention (Hammer & Sawyer, 2016).

Six studies explicitly stated who made the adaptations, typically one or more of the authors of the study. The developer(s) of the original intervention were involved in the adaptation in five studies (as generally determined by authorship on the publication). The authors of eight studies consulted with individuals who spoke the same language and/or identified with similar cultural backgrounds as anticipated intervention participants regarding the adaptations. These individuals included, for example, bilingual SLPs, university professors and educational consultants, and parents of children with and without disabilities. In some cases, participants in the intervention advised on the adaptations (e.g., mothers participating in Tsybina & Eriks-Brophy, 2010, supported selection of vocabulary targets). See Table 3 for a description of adaptation consultants.

Seven studies provided details on how authors determined which specific components of the intervention required adaptation and which adaptations were appropriate. The specified sources of information on adaptations included consultation (Binger et al., 2008; Hammer & Sawyer, 2016; Ijalba, 2015; Magaña et al., 2017; Peredo et al., 2017), literature reviews (Durán, Gorman, et al., 2016; Peredo et al., 2017), and analysis of previous intervention implementation efforts (van Tuijl et al., 2001).

Adapted Components

Studies were reviewed for information on which specific components of the intervention were modified, including content, context, delivery, training, and evaluation. Table 4 provides a description of these adaptations. Most studies (n = 31) described adaptations to the content of the intervention. Predominantly, content adaptations focused on developing intervention materials in the home language. For example, Spencer et al. (2020) created narratives in Spanish to teach children narrative structure while Gutiérrez-Clellen et al. (2012) selected the same books in Spanish and English to promote children's academic readiness. Some authors also enhanced the cultural relevance of materials, such as selecting or creating books that reflected common cultural experiences or values (e.g., Hammer & Sawyer, 2016; Méndez et al., 2015). A small number of studies developed intervention targets in the home language (e.g., Restrepo et al., 2013) or modified intervention strategies specifically to account for families' cultural values or practices (Binger et al., 2008; Boyce et al., 2010; Magaña et al., 2017; Mesa & Restrepo, 2019; Peredo et al., 2017) or to support development in both languages (Durán, Gorman, et al., 2016). Magaña et al. (2017) were the only authors to specify adaptation of the intervention context per our definition, implementing the intervention in the home (rather than an outside location) to avoid the need for transportation and child care. Twenty-seven studies modified the delivery of the intervention, generally by providing the full intervention or some intervention sessions in families' home language(s) via bilingual interventionists or having children's parents implement the intervention (in the home or preferred language). Fourteen studies adapted the intervention training, such as using an interpreter to support parent training (e.g., Cooke et al., 2009), creating new materials in the families' home language (e.g., Peredo et al., 2017), or incorporating family values in training (Mesa & Restrepo, 2019). Twenty studies include examples of or access to the adapted intervention materials. Thirty studies specified adaptations to the evaluation of the intervention. Typically, these adaptations involved measuring outcomes in the home language (as well as in English in some cases) via assessors who spoke the target language(s).

Evaluation of the Success of the Adapted Intervention

Four studies included details about pilot testing of the fully adapted intervention with representatives of the target population (Durán, Gorman, et al., 2016; Hammer & Sawyer, 2016; Magaña et al., 2017; Peredo et al., 2017). The authors of one study specified that field testing was used to finalize the word list used in the adapted intervention (Leacox & Jackson, 2014), and Meadan et al. (2020) described their study as a preliminary evaluation. All of the studies cited above except Magaña et al. (2017) discussed how the outcomes of this testing were used to further develop the adapted intervention. Sixteen studies provided data collected on the perceived social validity of the adapted intervention. Social validity data were chiefly obtained from children's caregivers (n = 11). Other respondents included participating children (n = 1), spouses of participating parents (n = 1), and early childhood education and special education personnel involved in delivery of the intervention (n = 4). Most often, social validity data were collected via a survey (n = 11) or interview (n = 5) at postintervention. Social validity data focused on reported satisfaction or perceived benefits (n = 11), use of intervention strategies and/or perceptions of strategy effectiveness (n = 8), perception of fit with cultural beliefs and/or family needs (n = 3), and recommendations for improvement (n = 2). All studies measured outcomes of the adapted intervention, including child language and literacy outcomes in one or more languages using researcher-designed probes, language samples, and standardized assessments. Caregiver outcomes were also assessed in some studies.

Interim Summary: Systematic Review Findings

The systematic literature review revealed strengths and areas of growth for the field of speech-language pathology in providing details about the adaptations of early language and literacy interventions for CLD populations. We reiterate that adaptation procedures may have been present in the studies reviewed but not reported. Studies showed a notable strength in linguistic responsivity, as the majority of adapted intervention procedures incorporated children's home language(s). Yet, clear areas of continued growth in our application and documentation of adaptation processes include improving reporting standards for cultural and linguistic adaptations, consulting more closely with the CLD populations for whom the intervention is being adapted, and increasing attention to adaptations that account for children's cultures (in addition to their languages). These findings suggest that the field currently has limited access to details on how early language and literacy interventions have been adapted. Given the relative lack of published work outlining explicit adaptation procedures, the following case study provides a robust example of the application of an adaptation process to support both stronger procedures and reporting standards. We will return to the pattern of findings from the literature review in greater detail in the discussion.

Case Study

In the following sections, we describe our process for adapting an early language intervention undertaken to support families of Spanish-speaking Mexican immigrant descent. We document why, when, and how we made adaptations; which framework guided our adaptations; who was involved in adapting; and what was adapted in accordance with guidelines for describing intervention adaptations (Escoffery et al., 2018; J. E. Moore et al., 2013; Stirman et al., 2013). We also share details on our translation process and pilot test of the adapted intervention, which provided information on the social validity and outcomes of the adapted intervention. This detailed example is intended to support researchers involved in adapting interventions and evaluating their success. Clinicians may find this example helpful to identify the varied components of any existing intervention that may require adaptation for a particular family.

Original Intervention

The Language and Play Every Day (LAPE) program (H. W. Moore et al., 2014) was the intervention targeted for adaptation. LAPE is a CI-NCI designed to coach caregivers of young children with language delays to use evidence-based language-facilitating strategies that promote child communication within families' existing routines. In particular, caregivers learn to (a) set up successful home routines for supporting child communication, (b) arrange and manage the environment to encourage child communication (e.g., placing materials in view but out of reach, providing materials piece by piece), (c) wait for child initiation and respond contingently, and (d) expand child verbal and nonverbal communication with an appropriate verbal model. While their children participate in a play group, caregivers meet weekly in a group setting for approximately 3 months to learn all of the LAPE strategies. Graduate students in Communication Disorders and Sciences and Early Intervention implement the intervention while supervised by nationally certified SLPs. Caregivers are encouraged to apply the strategies that work best for their child.

Purpose of Adaptation and Target Participants

LAPE had been delivered to over 75 families from primarily English-speaking, White backgrounds for over 8 years. As the number of families from Mexican immigrant homes grew in our community, so too did our need to develop a culturally and linguistically appropriate intervention. Because LAPE emphasizes naturally occurring family routines and encourages flexibility in strategy application, this intervention was considered highly adaptable to diverse contexts. Moreover, prior research on similar interventions implemented with Spanish-speaking and Mexican-origin families suggested that LAPE (with appropriate adaptation) could support child and caregiver outcomes (Ijalba, 2015; Peredo et al., 2017; Tsybina & Eriks-Brophy, 2010).

Adaptation Process of LAPE-e

Adaptation Framework

We adapted LAPE using the Cultural Adaptation Process (CAP) model developed by Domenech Rodríguez and Weiling (2004). Originally developed for the field of counseling psychology, the CAP model is a process-oriented, iterative, dynamic, and collaborative approach to adapt existing evidence-based interventions. It includes all of the key components recommended for a rigorous adaptation (Escoffery et al., 2019) and has a history of success in adapting caregiver-focused interventions for Latinx families, including those of Mexican origin and those with children with disabilities (e.g., Baumann et al., 2014; Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2011; Hurwich-Reiss et al., 2014; Kuhn et al., 2019). Moreover, the CAP model prioritizes the voices of the intervention stakeholders in the adaptation process rather than relying only on static literature reviews or expert opinion. Therefore, this approach appeared to be sufficiently rigorous, appropriate for our population of interest, and well aligned with our goal to center the voices of children and families in our work.

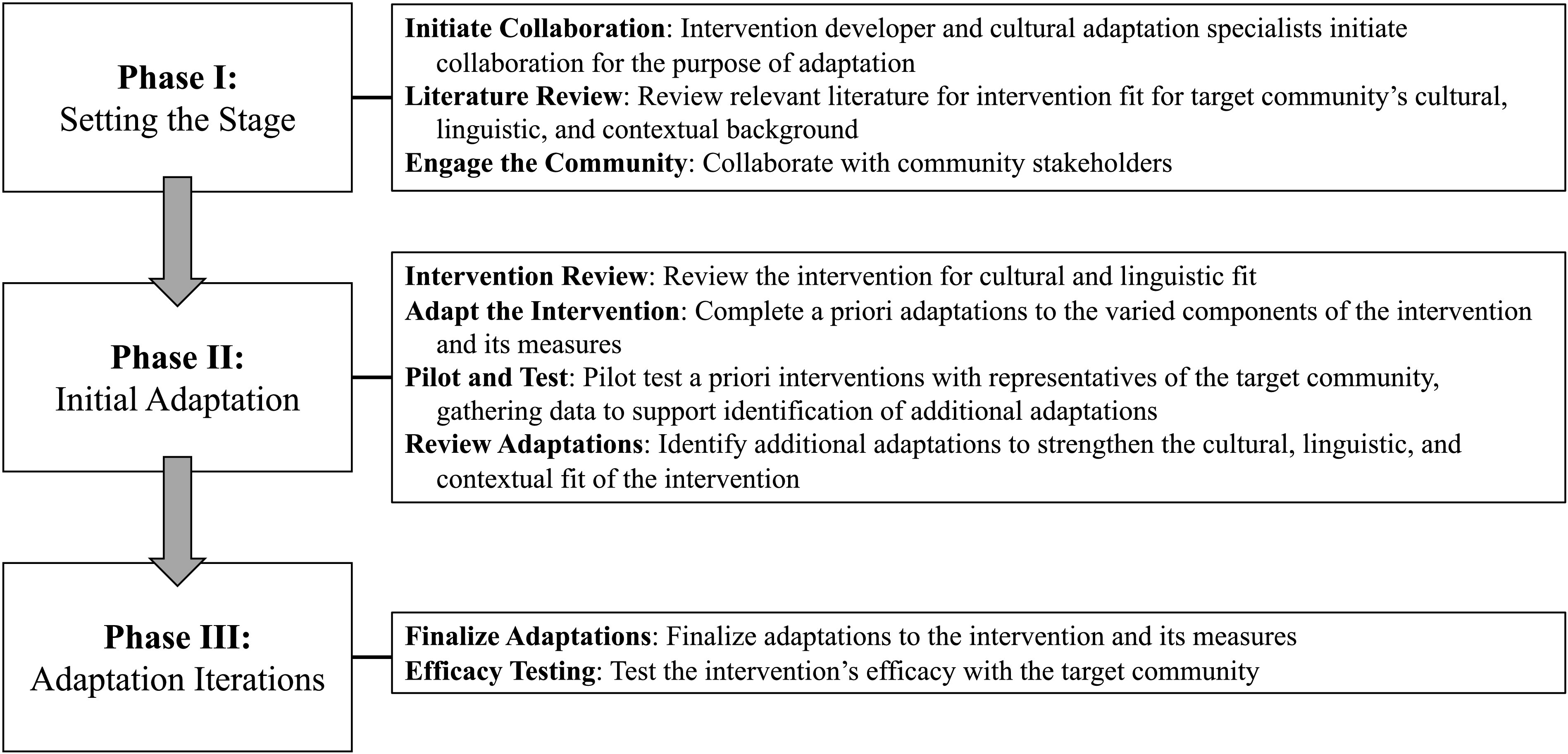

The CAP specifies three phases of adaptation that each entail certain steps and activities (Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2011). See Figure 1 for an overview. The first phase is preparatory and includes establishing the adaptation team and reviewing the intervention for cultural fit. The second phase entails making initial adaptations to the intervention and its measures as guided by the Ecological Validity Framework, originally developed to support intervention adaptations for Latinx populations specifically (Bernal et al., 1995; Bernal & Sáez-Santiago, 2006). The second phase also includes pilot testing the adapted intervention with representatives of the target population in order to determine additional cultural and linguistic considerations. The third phase requires additional adaptations to the intervention based on knowledge gained from the pilot test, concluding with efficacy testing of the fully adapted intervention with new participants. We describe the first and second adaptation phases in this review article.

Figure 1.

Overview of the Cultural Adaptation Process model (Domenech Rodríguez & Weiling, 2004).

Adaptation Timing

In accordance with the CAP model, adaptations were made prior to intervention delivery and following pilot testing. Six months were devoted to focusing on initial adaptations to the intervention. Our review of the results of the pilot testing and further adaptation to prepare LAPE en español (LAPE-e) for further efficacy testing lasted approximately 3 months.

Adaptation Consultants

The CAP model requires collaboration between the developer of the intervention and the cultural adaptation specialist(s) and key stakeholders who can provide input on community needs. The developer of LAPE (third author) and the cultural adaptation specialists (first, second, and fourth authors), all of whom are SLPs with experience in EI, collaborated. The intervention developer had supervised LAPE for 8 years in the local community. The cultural adaptation specialists spoke Spanish and shared over 45 years of expertise related to early Spanish–English language development and disorders as well as dual language assessment and intervention in Mexican immigrant contexts. Two of the cultural adaptation specialists (second and fourth authors) identify as Latina of Mexican origin while the remaining collaborators identify as Anglo European (first and third authors). This team then collaborated with local EI/ECSE specialists, SLPs, a Spanish-speaking EI/ECSE interpreter, and Spanish-speaking caregivers of young children with disabilities. These consultants believed a group intervention focused on language development for children from Spanish-speaking backgrounds was needed and offered specific suggestions on recruitment, scheduling, and location.

Development of the Adaptations

The CAP model specifies that a priori adaptations are determined by compiling the expertise of the adaptation team and community stakeholders (as described above) and the findings from a review of literature of the intervention's applicability for the target population. Thus, prior to intervention delivery, our team carefully reviewed the goals, procedures, and intended outcomes of LAPE in light of existing literature on (a) cultural perspectives on child rearing in Latinx and Mexican immigrant homes (e.g., Caldera & Lindsey, 2015; Harwood et al., 2002), (b) Latinx and Mexican perspectives on language development and disorder (e.g., Cycyk & Hammer, 2020; García et al., 2000; Méndez Pérez, 2000; Rodriguez & Olswang, 2003), and (c) studies and reviews of existing early language interventions delivered to Latinx and Mexican families (e.g., Cycyk & Huerta, 2020; Cycyk & Iglesias, 2015; Ijalba, 2015; Kummerer et al., 2007; Peredo et al., 2017; Tsybina & Eriks-Brophy, 2010; van Kleeck, 1994). These efforts supported identification of initial cultural and linguistic adaptations hypothesized to better support families from Spanish-speaking Mexican immigrant backgrounds, as described next. Importantly, the literature reviewed highlighted variability across Mexican immigrant families in terms of beliefs, values, and practices toward early language development and disorders. Although these studies provided important cultural characteristics specific to working with this population, we anticipated high variability within this cultural group as well. As such, while we selected a priori adaptations based on (a) the most current and seminal work with Spanish-speaking Mexican immigrant families of young children specifically and (b) advice from consultants representing our community, the subsequent pilot test was designed to determine whether these adaptations were indeed appropriate for the diverse families we served.

Adapted Components

In accordance with the CAP model and the Ecological Validity Framework (Bernal et al., 1995; Bernal & Sáez-Santiago, 2006; Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2011), we modified specific aspects of the intervention content, delivery, context, training, and evaluation. Some elements of LAPE were not adapted.

Content. Content adaptations include changes to intervention content, procedures, or materials (Stirman et al., 2013). We considered LAPE's theoretical approach, the intervention goals and strategies, the metaphors used during the intervention, and the intervention materials.

Bernal and Sáez-Santiago (2006) recommend that the underlying theoretical constructs of the intervention match how the participants view the presenting problem and its remediation. In LAPE, the presenting problem is early language disorder while the primary construct for remediation is caregivers' facilitation of child communication skills in natural environments. Because Mexican immigrant families may view themselves as responsible for facilitating early language development in explicit and implicit ways (Cycyk & Hammer, 2020; Cycyk & Huerta, 2020), the adaptation team determined that this theoretical approach was appropriate. Moreover, the parents who we consulted indicated that language development was a concern for their children that warranted intervention, suggesting a view shared by the intervention team. Note that some parents from Mexican immigrant backgrounds do not view themselves as teachers of early language or literacy skills in particular (e.g., Cycyk & Hammer, 2020) and may not believe that their child has a language disorder warranting intervention before age 3 years (Méndez Pérez, 2000). LAPE's theoretical premise may not be aligned with the perspectives of these families.

The goals of the intervention should also be congruent with the perspectives of the target population (Bernal & Sáez-Santiago, 2006). While families of Mexican immigrant origin may hold several priorities for development in early childhood (e.g., physical development), support for communication development has been noted by some families as a critical goal for children's early years (Cycyk & Hammer, 2020; Cycyk & Huerta, 2020). Thus, the primary goal of LAPE specific to advancing young children's communication was determined to be appropriate. Coaches work with parents to choose (a) goals appropriate to their children's communicative needs, including increasing communication rate, rate of initiations, vocabulary size, and sentence length and complexity and (b) targeted caregiver skills, including successful execution of routines that support child communication and increased use of specific strategies within those routines. To our knowledge, no existing literature provides guidance on how Mexican immigrant families might perceive these goals; however, these targets are ubiquitous in CI-NCIs and supported by a wide body of literature for improving the communication abilities of children and their caregivers from varied backgrounds (e.g., Akamoglu & Meadan, 2018; Heidlage et al., 2020). While it is possible that some families from this background may value quiet and obedient young children over verbose children who initiate talk with adults and prioritize peer-to-peer over adult–child interaction (van Kleeck, 1994), we chose to retain these evidenced-based discrete goals and examine their appropriateness in pilot testing. We also maintained LAPE's focus on identifying communicative routines regularly shared by adults and children to support adult use of language-facilitating strategies.

Families' cultural values, beliefs, and practices should further be reflected in the intervention approach (Bernal & Sáez-Santiago, 2006). Previous research has indicated that a focus on child autonomy and, relatedly, following the child's lead or allowing the child to make choices are not always appropriate for Mexican immigrant families who may prioritize adult-directed activities (Cycyk & Huerta, 2020; Peredo et al., 2017; van Kleeck, 1994). Therefore, LAPE lessons related to following the child's lead and providing choices were adapted to ensure that families retained control of the activities and limited children's independence when appropriate. For example, we deemphasized giving children autonomy to select preferred food items during meals (Cycyk & Huerta, 2020) in favor of suggesting the child be offered a choice of which color plate or cup to use for the food items that the adult had made available. In addition, we expanded the definition of the strategy of expansion to include not only content and function words but also articles in Spanish (e.g., el, la), which are obligatory grammatical features to refer to objects in the environment (Peredo et al., 2017).

Metaphors incorporated in the intervention should also be relevant to participants' cultural background (Bernal & Sáez-Santiago, 2006). The LAPE team identified one specific metaphor for adaptation. When helping caregivers to develop empathy for the child's communication difficulties, the interventionists share a skill that was difficult to learn and describe what helped them to learn that skill (e.g., learning to ride a bike, mathematics). This example was changed to making mole, a traditional Mexican dish with a complex recipe often unique to a region and family. Cooking is an everyday routine that can be salient in transmitting Latinx immigrants' cultural values, beliefs, and strong sense of family obligation (Tsai et al., 2015). Two additional metaphors used in the intervention, one that likened early vocabulary learning to the process of building a house or a road and another that helped caregivers to envision characteristics of supportive communication teachers via an imaginary trip to a foreign country with an unknown language, were thought to be accessible to families and left unchanged.

Moreover, using the language(s) that is comprehensible to the participants is a critical component of responsive interventions (Bernal & Sáez-Santiago, 2006). Use of Spanish is common among families of Mexican immigrant descent (Crosnoe, 2006), and families from varied Latinx backgrounds have discussed the importance of using Spanish in early language interventions (Cycyk & Huerta, 2020). Thus, all LAPE written materials were translated into Spanish using a collaborative translation process (Douglas & Craig, 2007). Native Spanish speakers completed the initial translation, which was then reviewed for accuracy by all three of the cultural adaptation specialists. Mexican dialect was prioritized. Because families from this background may also use English, the original English documents remained available. We also provided families with bilingual Spanish–English progress reports following the intervention.

Delivery and context. Adaptations to the delivery and context involve changes to the format, setting, or personnel of the intervention (Stirman et al., 2013). Regarding the format and setting, LAPE has traditionally been delivered in a group once a week in locations outside of the home with a limited number of sessions taking place in the home. While some literature has suggested that families from Mexican immigrant backgrounds prefer the combination of group and individual formats and weekly meetings for EI/ECSE services (Powell et al., 1990), more recent research with Latinx families indicates varied preferences on whether early language interventions should occur in the home or in outside settings (Cycyk & Huerta, 2020). Given this variability, we relied on consultation from the local EI/ECSE staff to understand the preferences of our community. The EI/ECSE staff reported that Spanish-speaking Latinx families of young children with disabilities regularly attended support groups outside of the home and were accustomed to hosting EI/ECSE home visitors. Thus, these consultants believed that caregivers would be comfortable attending a group outside of the home and participating in home visits. Further pointing to the adequacy of the group format, Mexican immigrant families have reported that participating in groups with other caregivers of children with disabilities promotes access to information and emotional supports (Mueller et al., 2009). As such, we did not make major changes to the setting or the format of providing the intervention in a group.

However, we did make changes to LAPE's delivery to provide the caregiver sessions in Spanish and to use both Spanish and English in the child play group to meet children's individual needs. We also considered how the social, political, and economic contexts of families affect intervention participation (Bernal & Sáez-Santiago, 2006). Because lack of transportation among Latinx families can challenge participation in parenting interventions (Harachi et al., 1997), we provided free transportation for any family who expressed this need. In addition, some families from Mexican immigrant backgrounds may not be documented residents of the United States, which may lead to hesitation to participate in formal training programs. Therefore, none of the data collected in LAPE asked families about immigration status and participation did not require legal identification (Cycyk & Durán, 2020). Finally, families from Mexican backgrounds often live with extended family members who provide child care (Sarkisian et al., 2007) and have indicated a preference for including multiple family members in intervention programs (Cycyk & Huerta, 2020; Powell et al., 1990). As such, prior to the start of the intervention, we extended an invitation to all adult caregivers in the home (e.g., fathers, grandparents, adult siblings) and other children (e.g., cousins, siblings) to attend the caregiver or child play sessions. Throughout delivery of the intervention, we also explicitly encouraged caregivers who attended to share the information, activities, and written materials with caregivers who were unable to attend.

Regarding personnel, cultural relevance may be enhanced when there is a match between the background of the interventionists and the participants and when the format is one that participants prefer (Bernal & Sáez-Santiago, 2006). Efforts were made to ensure that the interventionists represented similar backgrounds as our participants. Recruitment was undertaken by one of the adaptation specialists who was Spanish speaking and Latina of Mexican descent. Graduate student interventionists who spoke Spanish and/or identified as Latina/o were also recruited to deliver the intervention. 1

Training. Training adaptations are specific to how the interventionists are trained to deliver the intervention (Stirman et al., 2013). In LAPE, students deliver the curriculum and caregivers are training to be the interventionist for their children. The students who delivered the adapted intervention received specific training in Spanish–English dual language development and culturally and linguistically responsive assessment and service delivery. In addition, the two cultural adaptation specialists who identified as Latina and of Mexican heritage attended all sessions. One supervised the caregiver group, and the other supervised the child play group.

In addition, caregiver training within LAPE is supported by general adult learning principles, such as active engagement, repeated exposure to material, multiple opportunities for practice, and individualized supports (e.g., Trivette et al., 2009). It was hypothesized that these adult learning principles would be applicable to adults from Mexican immigrant backgrounds, and no advanced adaptations were made. However, the team updated the supporting educational materials by adding videos of Spanish-speaking Latinx families.

Evaluation. Adaptations to evaluation consist of changes to how or what type of data are collected to evaluate intervention outcomes to enhance appropriateness for the target population (Domenech Rodríguez & Weiling, 2004; Stirman et al., 2013). Five methods of assessment have traditionally been used in LAPE. First, families videotape caregiver–child interactions during routine home activities to measure caregiver and child communication skill. Because families select relevant routines (rather than those prescribed by the interventionists) and are loaned video recorders, this method appeared ecologically valid and did not require adaptations. Second, caregivers complete a checklist of the words their child understands and says. Because many children from Spanish-speaking homes are exposed to varying degrees of Spanish and English (e.g., Place & Hoff, 2011), the adaptation team included word checklists in Spanish and English as the most valid method for assessing vocabulary in this population (Peña et al., 2016). These checklists were based on the Spanish and English MacArthur Communicative Developmental Inventories (Fenson et al., 1993; Jackson-Maldonado et al., 2003), which have been validated for use with toddlers exposed to Spanish and English (e.g., Marchman & Martínez-Sussmann, 2002). To lessen the burden on families to fill out two separate questionnaires while also capturing knowledge of words in Spanish, English, and both languages (i.e., translation equivalents), the Spanish and English checklists were combined so that all words across forms appeared as translation equivalents (De Anda et al., 2019). Third, caregivers participate in pre- and postintervention interviews to review their goals as well as their knowledge and use of LAPE's language-facilitating strategies. Fourth, caregivers complete a survey before and after LAPE to report on their self-efficacy in supporting their children's communication. Finally, caregivers complete a postintervention survey about their satisfaction with LAPE as a traditional measure of social validity. These interviews and surveys were translated into Mexican Spanish dialect, using the collaborative translation process described previously. Questions were added to address the how the intervention aligned with families' linguistic and cultural background. For example, caregivers were asked to rate their agreement with the following statements: “The strategies taught in LAPE matched my beliefs, values, and priorities for raising my child” and “The LAPE program took into account the needs and strengths of my family.”

In addition, we added two measures to supplement analysis of outcomes in this particular linguistic context. First, because interpretation of the vocabulary size of children exposed to two languages is aided by understanding their language input (e.g., Pearson et al., 1997), we included the Language Exposure Assessment Tool (De Anda et al., 2016) to measure children's exposure to Spanish, English, and other language(s) (e.g., indigenous languages of Mexico). The Language Exposure Assessment Tool was previously validated with young children from Spanish-speaking backgrounds. Second, the team added an all-day recording of the home to provide a naturalistic measure of child language as facilitated by the Language ENvironment Analysis (LENA ProSystem, 2012), which has also been validated in Spanish-speaking contexts (Weisleder & Fernald, 2013).

Pilot Testing

Once the a priori adaptations were finalized, in accordance with the CAP model, the adapted LAPE (entitled LAPE-e) was tested for feasibility with six families of Spanish-speaking Mexican immigrant backgrounds who had a total of eight children with early language delay (i.e., two sets of twins). The children had an average age of 35.1 months at the time of the intervention and produced an average of 240 words combined across Spanish and English. See Cycyk et al. (2020) for a full description of the participants, procedures, and outcomes of the LAPE-e feasibility testing. In brief, feasibility testing entailed (a) multiple measures of social validity throughout the course of LAPE-e to assess caregivers' perceptions of the goals, procedures, and outcomes (including a postintervention focus group and anonymous satisfaction survey) and (b) preliminary assessment of change in child and caregiver communication skills from pre- to postintervention. The triangulated findings indicated promise for LAPE-e supporting children and families from Spanish-speaking Mexican immigrant households. In general, families expressed satisfaction with the adapted intervention and felt it was congruent with their linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Moreover, several child and caregiver communication skills increased following LAPE-e, including child rate of communication and vocabulary as well as caregiver strategy use and self-efficacy.

Furthermore, the findings helped the intervention team determine additional areas of LAPE-e in need of adaptation to strengthen the intervention prior to efficacy testing. Specific to the content of the intervention, the data provided evidence that families held some goals that were not congruent with the intervention's explicit purpose. While families agreed that supporting language development was a goal for LAPE-e, as anticipated, families also expressed their interest in supporting child socialization and behavior. The emphasis placed on these skills aligns with previous research with Mexican immigrant mothers of young children, as likely related to the cultural value of raising children with a sense of familismo and respeto (Cycyk & Hammer, 2020). In addition, the findings suggested that the intervention delivery could be improved. Several families infrequently arrived on time to the afternoon sessions and had to reschedule sessions because the timing of LAPE-e interfered with other obligations, such as picking older children up from school. Differences in punctuality may be related to cultural concepts of time, while scheduling difficulties were simply related to families' life contexts. Still, families expressed their dissatisfaction in the length of the intervention, discussing their desire for more training and opportunities for practice. Related to the evaluation of LAPE-e, the use of the video equipment appeared to challenge families, perhaps due to the fact that smartphones are a much more common video-recording instrument than video cameras among Latinx adults (Perrin, 2017). Lastly, our outcome data indicated wide individual variability in change in child and caregiver outcomes following the intervention. We hypothesized that this variability may be due to differences in initial child and caregiver skill and/or limited opportunities to comprehensively coach families on the language-facilitating strategies over the short duration of LAPE-e.