Summary

Background

Multi-country studies assessing the quality of maternal and newborn care (QMNC) during the COVID-19 pandemic, as defined by WHO Standards, are lacking.

Methods

Women who gave birth in 12 countries of the WHO European Region from March 1, 2020 - March 15, 2021 answered an online questionnaire, including 40 WHO Standard-based Quality Measures.

Findings

21,027 mothers were included in the analysis. Among those who experienced labour (N=18,063), 41·8% (26·1%- 63·5%) experienced difficulties in accessing antenatal care, 62% (12·6%-99·0%) were not allowed a companion of choice, 31·1% (16·5%-56·9%) received inadequate breastfeeding support, 34·4% (5·2%-64·8%) reported that health workers were not always using protective personal equipment, and 31·8% (17·8%-53·1%) rated the health workers’ number as “insufficient”. Episiotomy was performed in 20·1% (6·1%-66·0%) of spontaneous vaginal births and fundal pressure applied in 41·2% (11·5% -100%) of instrumental vaginal births. In addition, 23·9% women felt they were not treated with dignity (12·8%-59·8%), 12·5% (7·0%-23·4%) suffered abuse, and 2·4% (0·1%-26·2%) made informal payments. Most findings were significantly worse among women with prelabour caesarean birth (N=2,964). Multivariate analyses confirmed significant differences among countries, with Croatia, Romania, Serbia showing significant lower QMNC Indexes and Luxemburg showing a significantly higher QMNC Index than the total sample. Younger women and those with operative births also reported significantly lower QMNC Indexes.

Interpretation

Mothers reports revealed large inequities in QMNC across countries of the WHO European Region. Quality improvement initiatives to reduce these inequities and promote evidence-based, patient-centred respectful care for all mothers and newborns during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond are urgently needed.

Funding

The study was financially supported by the Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste, Italy.

Study registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04847336

Keywords: COVID-19, European Region, maternal, newborn, facility, quality of care, questionnaire, respectful maternity care, survey, WHO

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched Medline on September 6, 2021 with no language nor date restrictions using the string ("Quality of Health Care"[Mesh] OR “quality of care” OR survey) AND ("COVID-19"[Mesh] OR "SARS-CoV-2"[Mesh] OR “COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2”) AND ("Maternal Health Services"[Mesh] OR “maternal health services” OR “maternity care” OR “newborn health services” OR “neonatal health services” OR “maternal health” OR “newborn health”). Despite the importance of quality of care for improving maternal and neonatal health, there is a lack of multicountry studies investigating with a comprehensive set of indicators the quality of maternal and newborn care (QMNC) during the COVID-19 pandemic, from the perspective of mothers, as key service users. Previously published studies were either single country, or had relatively small samples, or explored only specific aspects such as utilization of health services, mental health, breastfeeding practices, clinical manifestations of COVID-19-, or focused on specific populations such as small and sick newborns, or stillborn infants.

Added value of this study

This study reports the results of a multicountry online survey on the QMNC in 12 countries of the WHO European Region, based on the perspective of 21,027 mothers who gave birth during the COVID-19 pandemic. The QMNC was evaluated comprehensively, by collecting 40 WHO Standard-based Quality Measures, divided in four domains as per the WHO framework: provision of care; experience of care; availability of human and physical resources; and organisational changes due to COVID-19. Mothers reported significant gaps in the QMNC, with large inequalities across countries of the WHO European Region, with countries such as Croatia, Serbia, and Romania consistently showing a worse QMNC -as identified by the 40 indicators and by the QMNC Index- than other countries. However, no country was free from reported gaps in QMNC. Measures of patient-centred respectful care and availability of resources were reported as substandard in most countries.

Implications of all the available evidence

This study highlights that there is a pressing need to implement adequate health policies to reduce inequities in the QMNC across countries of the WHO European Region. Quality improvement initiatives are urgently needed at all levels of the health systems, to ensure that all women have access to and receive high-quality, evidence-based, equitable, and patient-centred respectful care, during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

The COVID‑19 pandemic has increased the existing challenges of all health systems, and the quality of maternal and newborn care (QMNC) worldwide has been particularly affected.1,2 During the pandemic, even among high income countries of the World Health Organisation (WHO) European Region, multiple studies, including a systematic review1,3, 4, 5 have documented a deterioration in key indicators, such as: reduced utilisation of maternal and newborn health services, increased number of stillbirths, increased medicalization of care (more caesarean sections and induction of labours), reduced family involvement, low support and uptake of breastfeeding, and amplified maternal anxiety and stress.

The ability of the healthcare system to withstand the COVID-19 pandemic has differed between countries and within countries over time.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Many institutions, organizations and agencies quickly reacted and recognised the importance of following appropriate procedures of maternal and newborn care, and called for action to support respectful family-centered care during the COVID-19 pandemic.6, 7, 8 Nevertheless, especially in the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, inappropriate protocols for the management of pregnancy, birth and postnatal care were applied in many settings, and violations of human rights were documented, such as unnecessary separation of the baby from the mother. 8,9 However, there is a lack of multicountry studies documenting the impact of the pandemic on different domains of the QMNC around the time of childbirth.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, evidence from large national surveys and other sources had highlighted gaps in the QMNC in countries of the WHO European Region.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 According to recent reports, while maternal mortality is increasingly rare in the WHO European Region, up to half of such deaths are associated with substandard care, and therefore preventable.10 Similarly, mistreatment of women during and after facility-based childbirth had been documented before the COVID-19 pandemic.15, 16, 17

Inappropriate case management and poor quality of care may be harmful to women and their newborns, violate women's and newborns’ rights, deter women from seeking future health care, and may have implications for the mental and physical health of mothers and newborns.18 In 2016, the WHO developed a list of Standards for improving the QMNC.19 A questionnaire based on the WHO Standards19 to measure QMNC from the perspective of key service users (mothers) at health facility level was recently developed and validated.20 The use of a standardized method to measure service users’ perspectives on the QMNC allows for comparisons of data across settings and over time. This study aimed at analysing maternal perspectives on the QMNC around the time of childbirth at facility level during the COVID-19 pandemic, and at comparing findings across countries of the WHO European Region. We also assessed how individual factors (ie, clinical or socio-demographic characteristics) were independently associated with the QMNC Index through multivariable regression models.

Methods

Study design and participants

This is a cross-sectional study, and is reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies (STROBE) in Epidemiology guidelines for cross-sectional studies.21 The STROBE Checklist is included as Supplementary Table 1.

Women ≥18 years-of-age who gave birth from March 1, 2020 up to the end of the data collection period (March 15, 2021) were invited to participate in an anonymous online survey. Women who did not match the inclusion criteria, or who did not give birth in a facility in the WHO European Region were excluded.

The online survey was made available in 16 languages. Women were invited to participate in the study in their preferred language regardless of which country they gave birth in. The survey was actively promoted by project partners in 12 countries of the WHO European Region, through a predefined dissemination plan, which included as main approaches social media, organizational websites, and local networks including mothers’ groups and Non-Governmental Organizations (details on the data collection periods by each country team are reported in Supplementary Table 2).

Data collection tool

Data were collected using a structured online questionnaire, based on the WHO standards,19 and recorded using REDCap 8.5.21 - © 2021 Vanderbilt University, via a centralized platform. The questionnaire included 40 questions on one key indicator each, equally distributed in four domains: the three domains of the WHO Standards19- provision of care, experience of care and availability of human and physical resources- and the additional domain on key organisational changes related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Questions on the individual characteristics of the participants (eg, clinical and socio-economic background) were also included.

The process of questionnaire development, validation, and previous use has been reported elsewhere.20,22,23 During the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the questionnaire was further optimized throughout a Delphi including 26 experts from 11 countries of the WHO European Region and adapted for an online survey. Details on the questionnaire development, validation and adaptation for the online survey are reported in Supplementary Figure 1. Briefly, the questionnaire was reduced in length (ie, including only 40 Quality Measures) and wording was adapted to an online survey; it was translated and back-translated in each language following guidance of The Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation Principles of Good Practice.24

Two tailored versions of the questionnaire were conceived at time of questionnaire development, one for women who underwent labour and one for those who had a prelabour caesarean section (CS), differing only by few questions, as appropriate (for example, women who did not experience labour were not asked about pain relief during labour). In the questionnaire, women were provided with the case definition of labour recommended by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines.25 Additionally, indicators were tailored to take into account different modes of birth (spontaneous vaginal, instrumental vaginal, and elective or emergency CS). Each version included a total of 40 key Quality Measures.

The 40 key indicators contributed to a composite QMNC Index, which was developed drawing on previous examples of other quality indexes,26 as a complementary synthetic measure of QMNC, with higher scores indicating higher adherence to WHO Standards.

Statistical analyses

A minimum required sample size of 300 women for each country was calculated, based on preliminary data from other studies15,20 on the hypothesis of an average QMNC Index (our primary outcome and dependent variable) of 75% ±7·5% (300 ±30 points, out of 400) and confidence level of 99·5%. This sample was also adequate to detect a minimum expected frequency on each quality measure of 3% ± 3%, with a confidence level of 99·5%. Since this was not an intervention study, and there was no risk for the enrolled cases, the upper limit of the sample was not predefined.

We performed a descriptive analysis, calculating absolute frequencies and percentages for socio-demographic variables and each of the 40 key Quality Measures. Since Quality Measures differed between the two groups of women, those who underwent labour and those who had a prelabour CS, findings are presented separately; differences in characteristics of two groups were tested with a chi square or a Fisher exact test as appropriate. Women were grouped in these two categories as follows: mothers with vaginal birth were considered as having experienced labour; women with emergency CS were categorised based on their report of having undergone labour or not, which was informed by the NICE definition of labour25 provided to them in the questionnaire. Odds ratios (OR) were calculated to assess differences in the 40 key Quality Measures between the two groups adjusting for all socio-demographic variables, type of professionals assisting the birth, newborn admission in neonatal intensive or semi-intensive care unit, mother admission in intensive care unit and multiple birth.

For the primary analysis, duplicates and cases missing 20% or more answers on 45 key variables (including the 40 key Quality Measures and five key socio-demographic variables: date of birth, age, education, parity, whether the women gave birth in the same country where she was born) were excluded. To further assess robustness of findings, two sensitivity analyses were conducted: 1) in the first scenario, we included women who answered 100% of the 40 key Quality Measures (N=15,399); 2) in the second scenario, we included women with up to 90% missing answers on 45 key variables (N=22,130) as performed by other authors.27

The QMNC Index was calculated based on the predefined criteria for all women providing an answer on all the 40 key Quality Measures. A predefined score (eg, 0-5-10 points) was attributed to each possible answer of each of the 40 questions on Quality Measures, with higher scores indicating higher adherence to WHO Standards. The QMNC Index was calculated for each domain as the sum of all points in that domain, and could range from 0 to 100, while the total QMNC Index was calculated as the sum of all points and could range from 0 top 400 (for more details see Supplementary Table 3). The QMNC Indexes were presented as median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) since they were not normally distributed. For countries with sample size over 300, a subgroup analysis was performed to analyse differences in the QMNC Indexes among countries.

Additionally, we performed multivariable regression models with the QMNC Index as the dependent variable and included all socio-demographic variables, birth mode, and type of professionals assisting the woman during birth as independent variables, to account for potential confounders. Given that the QMNC Index was a continuous variable not normally distributed, we conducted a multivariable quantile regression with robust standard errors (SEs).28 Quantile regression is an extension of linear regression used when the conditions of linear regression are not met; it allows modelling at different quantiles of the outcome where associations between exposure and outcome can differ.28 We modelled the median, the 0·25th and 0·75th quantile. We chose this modelling approach given statistical evidence of heteroskedasticity28 for parity, country where the women gave birth, education, year women gave birth, mode of birth, and presence of a midwife in the team who assisted the birth (Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test p<0·001, H0: no heteroskedasticity). A graphical representation (kernel density) of the QMNC Index was plotted for each independent variable. The categories with the highest frequency were used as reference.

A two tailed p-value <0·05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata/SE version 14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethical aspects

The anonymous online survey was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the coordinating centre: the IRCCS Burlo Garofolo Trieste (IRB-BURLO 05/2020 15.07.2020), and by the ethical committees of three other countries: Portugal (Instituto de Saúde Pública da Universidade do Porto, CE20159); Norway (Norwegian Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics, 2020/213047) and Germany (Bielefeld University ethics committee, 2020-176). Since this was an online survey that mother could decide to join on a voluntary basis, and no data elements that could disclose maternal identity were collected, a formal approval was waived by the ethical committee of the other countries. The survey was conducted according to General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) regulations. Prior to participation, women were informed of the objectives and methods of the study, including their rights in declining participation, and each provided consent before responding to the questionnaires. Anonymity in data collection during the survey phase was ensured by not collecting any information that could disclose participants’ identity. Data transmission and storage were secured by encryption.

Role of the funding source

This research was funded by the Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste, Italy. The funding source had no role on study design, data analysis, data interpretation, and reporting.

Results

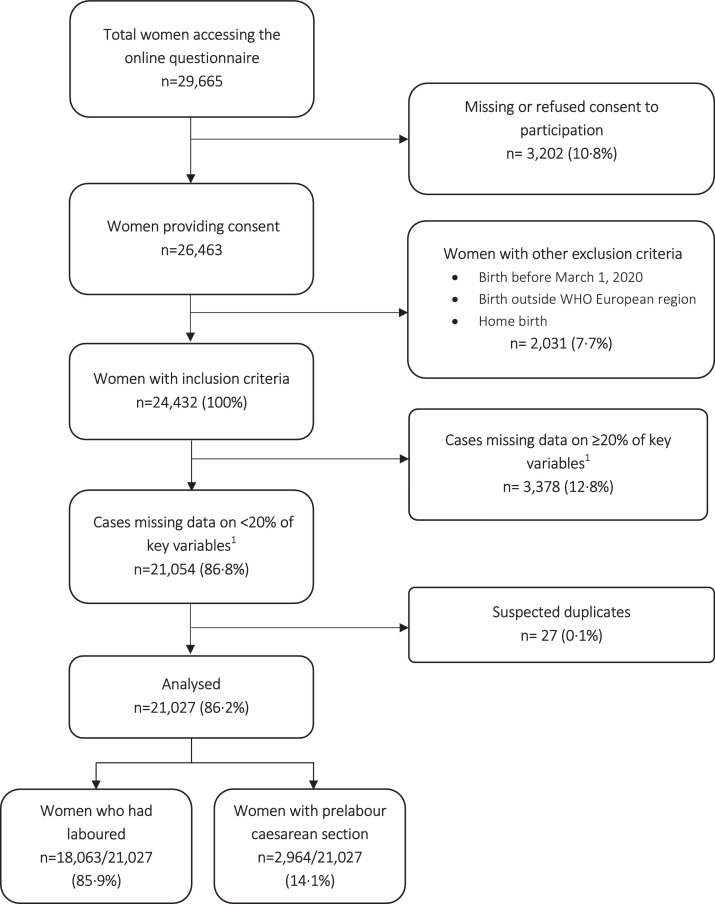

Out of 29,665 women accessing the online questionnaire, 26,463 (89·2%) provided consent to participate. Among the 24,432 women who met the inclusion criteria, 21,027 (86·2%) were included in the analysis after exclusion of cases missing 20% or more key variables and suspected duplicates (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram - Note:1 We used 45 key variables (40 key Quality Measures and five key socio-demographic questions).

The absolute number of women responding to the survey varied among the 12 countries, with Italy (4,813 women), Sweden (4,800), Norway (3,220), Slovenia (2,092), and Portugal (1,685) being the countries with the largest samples (Table 1). When the sample collected in each country was compared to the estimated total births during the study period, it accounted for at least 1% of the total expected births in eight countries. (Supplementary Table 4). A total of 345 cases were collected from another 24 countries (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondents

| N=21,027 n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Country | ||

| Italy | 4,813 | 22·9 |

| Sweden | 4,800 | 22·8 |

| Norway | 3,220 | 15·3 |

| Slovenia | 2,092 | 9·9 |

| Portugal | 1,685 | 8·0 |

| Germany | 1,081 | 5·1 |

| Serbia | 630 | 3·0 |

| Romania | 571 | 2·7 |

| France | 544 | 2·6 |

| Croatia | 458 | 2·2 |

| Luxembourg | 441 | 2·1 |

| Spain | 347 | 1·7 |

| Other countries1 | 345 | 1·6 |

| Year of giving birth | ||

| 2020 | 11,458 | 54·5 |

| 2021 | 8,752 | 41·6 |

| Missing | 817 | 3·9 |

| Gave birth in the same country where were born | ||

| Yes | 19,021 | 90·5 |

| No | 1,523 | 7·2 |

| Missing | 483 | 2·3 |

| Age range | ||

| 18-24 | 949 | 4·5 |

| 25-30 | 7,323 | 34·8 |

| 31-35 | 8,213 | 39·1 |

| 36-39 | 3,070 | 14·6 |

| ≥40 | 992 | 4·7 |

| Missing | 480 | 2·3 |

| Educational level2 | ||

| None | 8 | 0·1 |

| Elementary school | 46 | 0·2 |

| Junior High school | 1,100 | 5·2 |

| High School | 5,152 | 24·5 |

| University degree | 8,725 | 41·5 |

| Postgraduate degree / Master's /Doctorate or higher | 5,515 | 26·2 |

| Missing | 481 | 2·3 |

| Parity | ||

| 1 | 12,554 | 59·7 |

| >1 | 7,992 | 38·0 |

| Missing | 481 | 2·3 |

| Mode of birth | ||

| Vaginal spontaneous | 14,110 | 67·1 |

| Instrumental vaginal | 1,928 | 9·2 |

| Caesarean section | 4,989 | 23·7 |

| Elective caesarean section | 1,995 | 9·5 |

| Emergency caesarean section during labour | 2,025 | 9·6 |

| Emergency caesarean section prelabour | 969 | 4·6 |

| Type of facility | ||

| Public | 19,160 | 91·1 |

| Private | 1,387 | 6·6 |

| Missing | 480 | 2·3 |

| Type of healthcare providers who directly assisted the birth3 | ||

| Midwife | 18,153 | 86·3 |

| Nurse | 8,068 | 38·4 |

| A student (ie, before graduation) | 3,450 | 16·4 |

| Obstetrics registrar / medical resident (under post-graduate training) | 3,780 | 18·0 |

| Obstetrician-gynaecologist doctor | 10,876 | 51·7 |

| I don't know (healthcare providers did not introduce themselves) | 1,802 | 8·6 |

| Other | 3,029 | 14·4 |

| Other characteristics | ||

| Newborn admitted in neonatal intensive or semi-intensive care unit | 1,740 | 8·3 |

| Mother admitted in intensive care unit | 347 | 1·7 |

| Multiple birth | 260 | 1·2 |

Notes:

Other countries: Belgium (n=122); Austria (n=41); UK (n=36); Finland (n=28); Bosnia Herzegovina (n=27); Switzerland (n=21); Denmark (n=15); Greece, Ireland, Netherlands, Ukraine, Andorra, Montenegro, Russian Federation, Lithuania, Iceland, Poland, Turkey, Hungary, Albania, Cyprus, Latvia, Macedonia, and Czech Republic (each fewer than 10 cases).

Wording on education levels agreed among partners during the Delphi; questionnaire translated and back translated according to ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation Principles of Good Practice.

More than one possible answer.

Most (88·5%) women were 25 to 39 years old; about two thirds (67·7%) had either a university degree or a postgraduate degree while about one quarter (24·5%) a high school education; around one third (38·0%) had a previous birth. Most women (91·1%) gave birth in a public hospital, and about half (51·7%) were assisted by an obstetrician-gynaecologist doctor during birth. Overall, 4,989 (23·7%) women had a CS birth, while 1,928 (9·2%) had an instrumental vaginal birth.

Key differences in the characteristics of women who had prelabour CS compared to those who laboured (Supplementary Table 5) included: older age (29·7% vs 17·6% of mothers older than 35 years, p<0·001), giving birth in a private facility (13·5% vs 5·5%, p<0·001), more frequently being assisted by a doctor during birth (81·2% vs 46·9% p<0·001), presenting a higher frequency of multiple births (4·1% vs 0·8% p<0·001), newborns admitted in neonatal intensive or semi-intensive care unit (14·5% vs 7·3%, p<0·001), and mothers admitted to intensive care unit (4·9% vs 1·1%, p<0·001).

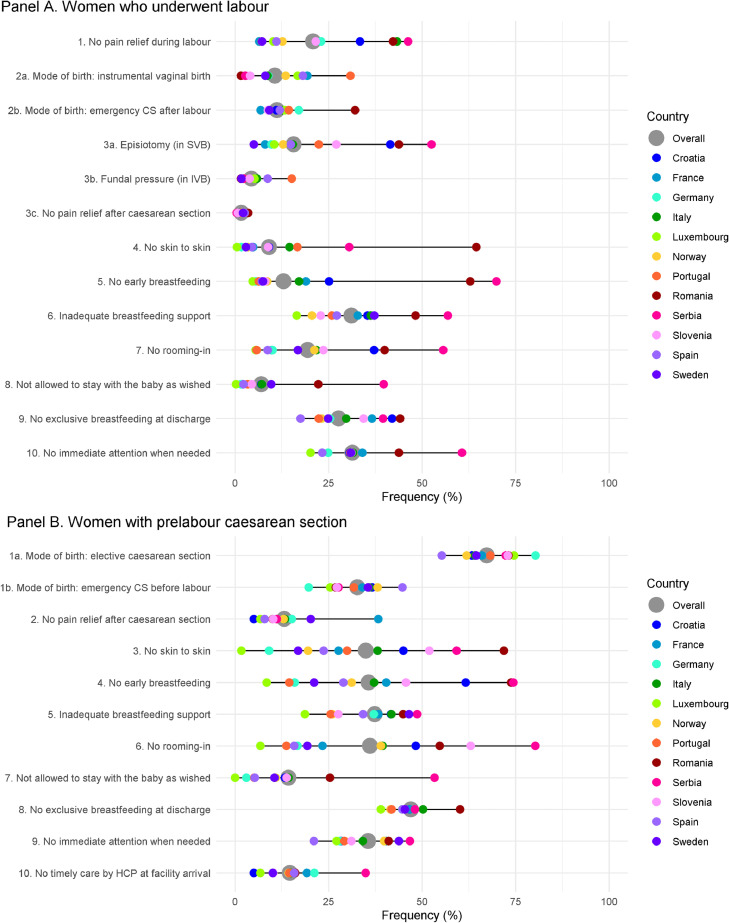

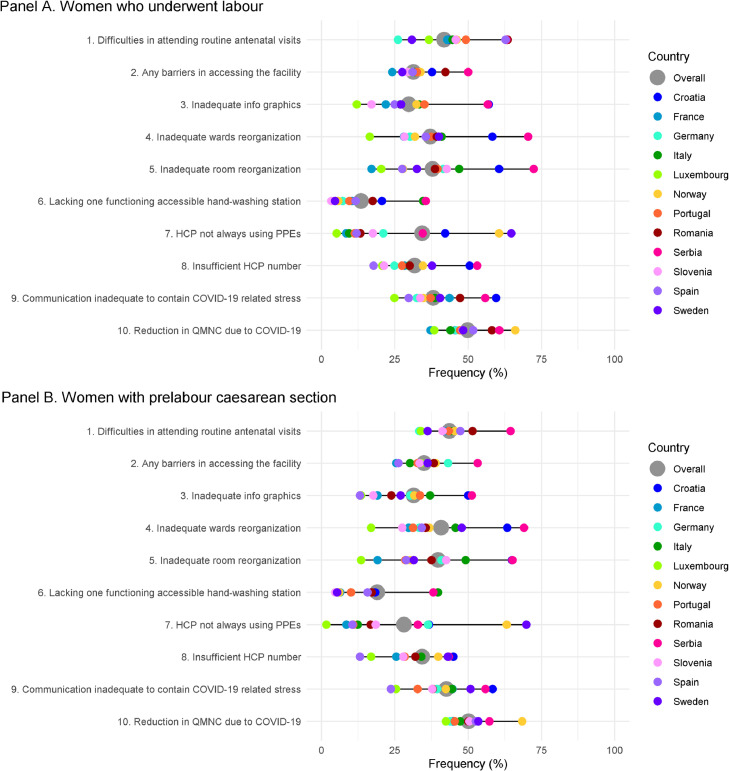

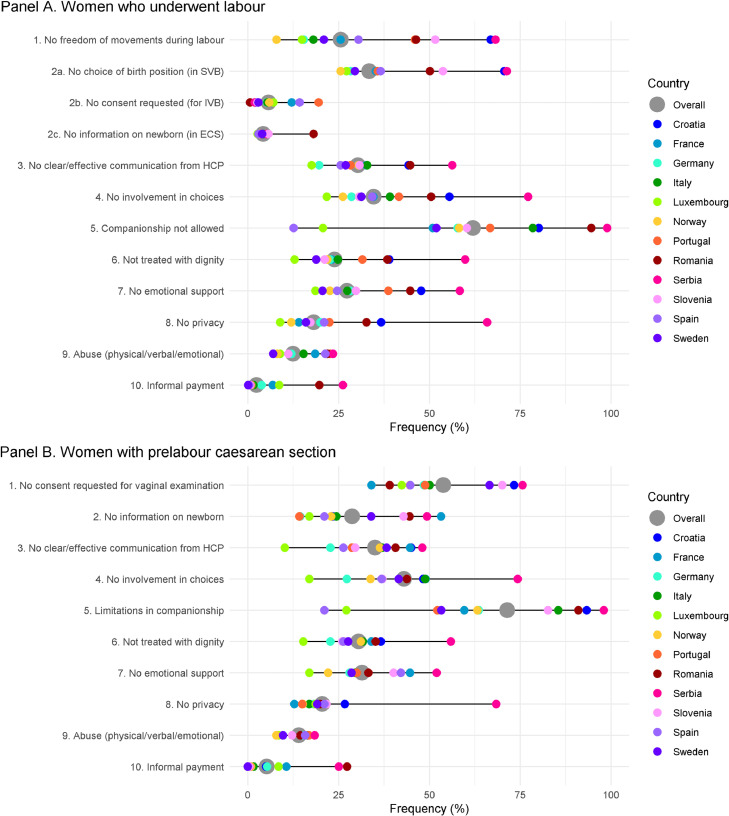

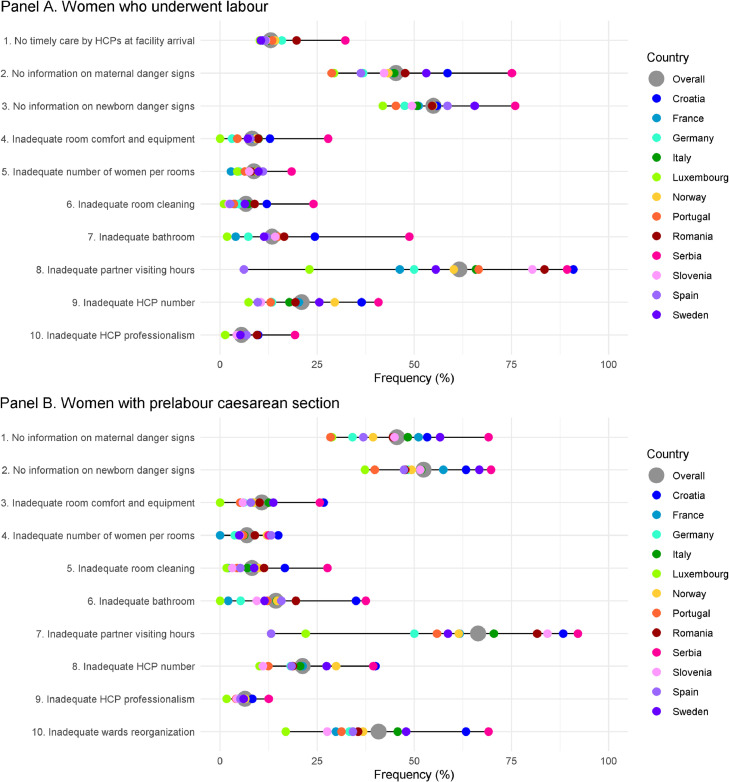

Figures 2to5 show findings on each of 40 key Quality Measures, in the groups of women who underwent labour (Panel a) and for those with prelabour CS (Panel b). Data are reported as median frequency on the total sample (grey dot) and as median frequency on the sample of women giving birth in each country (coloured dots). More detailed data are reported in Supplementary Tables 6-9.

Figure 2.

Provision of care – Notes: Data are reported as median frequency on the total sample (grey dot) and as median frequency on the sample of women giving birth in each country (coloured dots); horizontal grey line represents the range of the median frequencies. All the indicators in the domain of provision of care are directly based on WHO standards. Indicators identified with letters (eg, 3a, 3b) were tailored to take into account different mode of birth (ie, spontaneous vaginal, instrumental vaginal, and caesarean section). These were calculated on subsamples (eg, 3a was calculated on spontaneous vaginal births; 3b was calculated on instrumental vaginal births). Abbreviations: CS = caesarean section; HCP = health care provider; IVB= instrumental vaginal birth; SVB = spontaneous vaginal birth.

Figure 5.

Reorganizational changes due to COVID-19 – Notes: Data are reported as median frequency on the total sample (grey dot) and as median frequency on the sample of women giving birth in each country (coloured dots); horizontal grey line represents the range of the median frequencies. Indicator 6 in both panels was defined as: at least one functioning and accessible hand-washing station (near or inside the room where the mother was hospitalised) supplied with water and soap or with disinfectant alcohol solution. Abbreviations: HCP = health care provider; PPE = personal protective equipment; QMNC = quality of maternal and newborn care.

In the domain of provision of care (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 6), out of the total number of women who underwent labour (N=18,063), 1,642 (9·1%) women did not have skin-to-skin with their newborn, 2,339 (12·9%) did not breastfeed within the first hour, 5,630 (31·1%) received inadequate breastfeeding support, 3,505 (19·4%) did not have continuous rooming-in, and 5,673 (31·4%) did not receive immediate attention when needed. For most Quality Measures there were wide variations between countries, with a tendency among women giving birth in the same country to report similar findings on different Quality Measures: lack of skin-to-skin ranged from 0·5% Luxemburg to 64·4% in Romania; lack of early breastfeeding, inadequate breastfeeding support, lack of rooming-in, and lack of attention when needed were consistently lower than the total sample in Luxemburg (4·7%, 16·5%, 5·5%, 20·2% respectively) and higher in Serbia (69·9%, 56·9%, 55·6%, 60·7%). Similarly, other measures of provision of care varied largely across countries: 3,764 (20·8%) women did not receive any pain relief method during labour, and this frequency varied in between 6·4% in France to 46·2% in Serbia. Episiotomy was performed in 2,832 (20·1%) of women with spontaneous vaginal birth (6·1% in Sweden to 66·0% in Romania), and fundal pressure applied in 41·2% (11·5%in France to 100% in Romania) of instrumental vaginal births.

Large variations were observed on all Quality Measures of experience of care (Figure 3, Supplementary Table 7). Overall, 11,198 (62·0%) women had limitations imposed regarding the presence of a companion of choice (12·6% in Spain to 99·0% in Serbia); 6,039 (42·8%) of those with spontaneous vaginal birth could not choose their birth position (32·4% in Italy to 81·9% in Croatia); 1,033 (53·6%) did not provide consent for an instrumental vaginal birth (35·9% in Sweden to 81·8% in Croatia); 5,473 (30·3%) did not experience clear communication from health workers (17·5% in Luxemburg to 56·3% in Serbia); 6,259 (34·7%) did not feel involved in choice related to the medical interventions they received (21·7% in Luxemburg to 77·2% in Serbia); 4,315 (23·9%) felt they were not always treated with dignity (12·8% in Luxemburg to 59·8% in Serbia); 2,256 (12·5%) reported abuses (7·0% in Sweden to 23·4% in Serbia), and 2·4% (0·1% in Sweden to 26·2% in Serbia) made informal payments.

Figure 3.

Experience of care – Notes: Data are reported as median frequency on the total sample (grey dot) and as median frequency on the sample of women giving birth in each country (coloured dots); horizontal grey line represents the range of the median frequencies. All the indicators in the domain of experience of care are directly based on WHO standards. Indicators identified with letters (eg, 2a, 2b) were tailored to take into account different mode of birth (ie, spontaneous vaginal, instrumental vaginal, and caesarean section). These were calculated on subsamples (eg, 2a was calculated on spontaneous vaginal births; 2b was calculated on instrumental vaginal births). Abbreviations: ECS = emergency caesarean section; HCP = health care provider; IVB= instrumental vaginal birth; SVB = spontaneous vaginal birth.

Findings in the domain of availability of physical and human resources (Figure 4, Supplementary Table 8) also showed large variations in frequencies between countries, with a tendency among women giving birth in the same country to rate QMNC consistently across different Quality Measures: 1,202 (6·7%) women reported insufficient/very bad room cleaning (1·0% in Luxemburg to 24·1% in Serbia); 2,421 (13·4%) reported insufficient/very bad bathroom facilities (1·8% in Luxemburg to 48·7% in Serbia); 3,798 (21·0%) women rated as insufficient/very bad the number of health care professionals compared to the workload (7·3% in in Luxemburg to 40·8% in Serbia). Overall, 11,132 (61·6%) women (23·0% in in Luxemburg to 89·3% in Serbia) felt that the visiting hours for partners/relatives was insufficient/very bad.

Figure 4.

Availability of physical and human resources – Notes: Data are reported as median frequency on the total sample (grey dot) and as median frequency on the sample of women giving birth in each country (coloured dots); horizontal grey line represents the range of the median frequencies. All the indicators in the domain of resources are directly based on WHO standards. Abbreviations: HCP = health care provider.

Key findings in the domain related to organisational changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 5, Supplementary Table 9) revealed that 9008 (49·9%) women perceived a reduction in QMNC due to the COVID-19 pandemic (38·5% in Luxemburg to 60·7% in Serbia). Difficulties in attending routine antenatal visits due to the COVID-19 pandemic were experienced by 7,556 (41·8%) women, (26·1% in Germany to 63·5% in Romania). Overall, 2,454 (13·6%) women reported the lack of at least one functioning and easily accessible hand washing station near or inside the room where the mother was hospitalised (4·7% in Luxemburg to 35·6% in Serbia) while 6,218 (34·4%) reported that health workers were not always using personal protective equipment (PPE) (5·2% in Luxemburg to 64·8% in Sweden).

Among the group of women who had a prelabour CS, general gaps in the QMNC were more frequent, compared to the group of women who did experience labour (Supplementary Table 10), when adjusted for all socio-demographic variables, type of professionals assisting the woman, newborn admission in neonatal intensive or semi-intensive care unit, mother admission in intensive care unit and multiple birth. Key significant differences include: no skin-to-skin (35·0% in those who did not experienced labour vs 9·1% in those who did, adjusted OR 3·39 95%CI 3·02-3·81); no early breastfeeding (35·7% vs 12·9%, adjusted OR 2·95 95%CI 2·63-3·30), no rooming-in (36·1% vs 19·4%, adjusted OR 1·68 95%CI 1·50-1·89), not allowed to stay with the baby as wished (14·3% vs 7·0%, adjusted OR 1·35 95%CI 1·15-1·58), no exclusive breastfeeding at discharge (47·0% vs 27·7%, adjusted OR 1·76 95%CI 1·60-1·94), limitations imposed regarding the presence of a companion of choice (71·5% vs 62·0%, adjusted OR 1·25 95%CI 1·13; 1·39), and health care provider not always using PPEs (28·2% vs 34·4%, adjusted OR 1·17 95%CI 1·04; 1·31). Few Quality Measures highlighted better practices in the group of women with prelabour CS who reported lower OR for: lack of emotional support (adjusted OR 0·88 95%CI 0·80-0·98); lack of privacy (adjusted OR 0·84 95%CI 0·75-0·95); abuses (adjusted OR 0·86 95%CI 0·76; 0·98); and inadequate number of women per rooms (adjusted OR 0·81 95%CI 0·67-0·96).

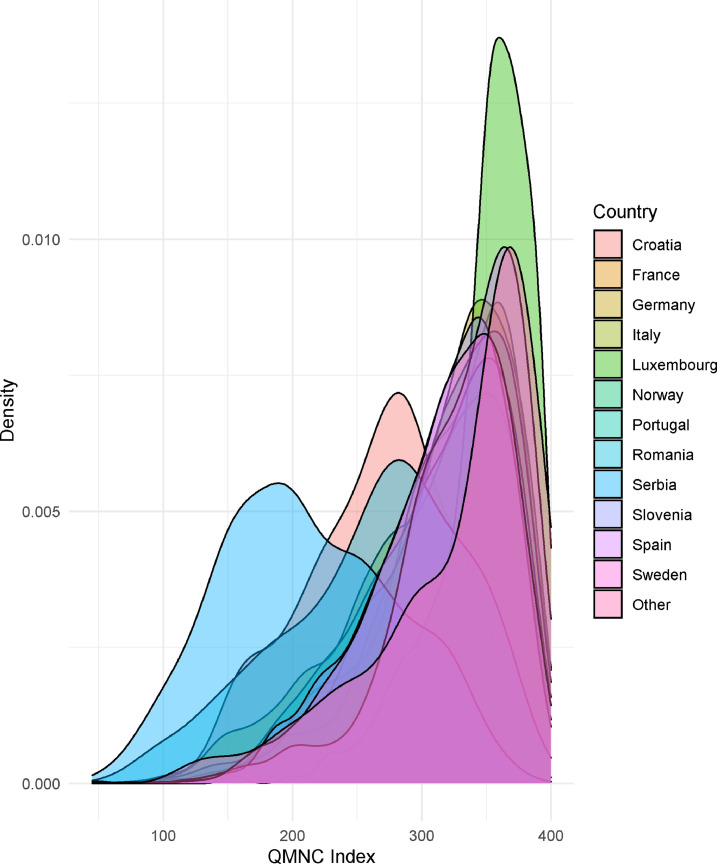

The QMNC Index (Supplementary Figure 2) varied between countries, with Luxemburg, Spain, Germany, France, Norway, and Sweden presenting a significantly higher median QMNC Index than the total samples (p<0·001 in all comparison except Sweden p=0·003). Italy, Romania, Croatia, and Serbia had a lower median value than the whole sample (p<0·001 on all comparisons). The median QMNC Indexes of Slovenia and Portugal were not significantly different from those of the overall sample (Supplementary Table 11).

Sensitivity and multivariate analyses

Findings of the sensitivity analyses were similar to findings of the primary analysis (Supplementary Figures 3-4, Supplementary Tables 12-15).

In the multivariate analysis (Supplementary Table 16, Figure 6), when adjusted for other variables, compared to the reference country (Italy), women who gave birth in Croatia, Romania, and Serbia reported significantly lower median QMNC Index while women who gave birth in other countries had significantly higher QMNC Index, either for all or at some of the QMNC Index quantiles analysed. The largest QMNC Index variations were rated by women who gave birth in Serbia and Luxembourg (coefficient variation at the 0·25th, 0·50th and 0·75th quantile respectively for Serbia: -100, -105, -90; Luxemburg: +55·0, +35·5, +20).

Figure 6.

QMNC Index by country of giving birth - Abbreviations: QMNC = quality of maternal and newborn care.

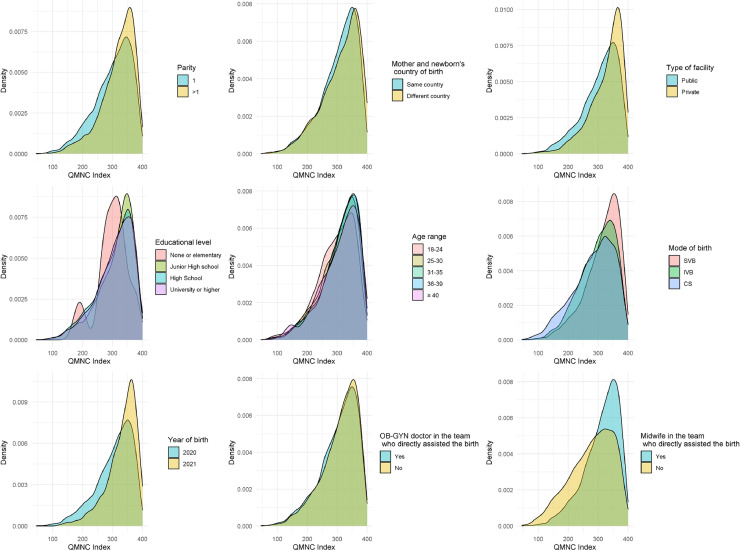

When corrected for other variables (Supplementary Table 16, Figure 7), a significant higher median QMNC Index with increasing larger coefficients at lower quantiles was found in multiparous women, women who gave birth in a private facility, in year 2021, and women who were assisted either by a midwife or an obstetrics and gynaecology doctor (coefficient variation at the 0·25th, 0·50th and 0·75th quantile:+20·0, +13·2, +10·0 for multiparous women; +28·3, +28·6, +20·0 for private hospital; +21·7, +16·8, +10·0 for women who gave birth in 2021; +31·7, +24·5, +15·0 for women with a midwife who assisted the birth; +10·0, +6·4, +0·0 for women with an obstetrics and gynaecology doctor who assisted the birth). Coefficients of all quantiles were statistically significant except for women with an obstetrics and gynaecology doctor who assisted the birth.

Figure 7.

QMNC Index by other variables used in quantile regression analysis - Abbreviations: CS = caesarean section; IVB = instrumental vaginal birth; OB-GYN = obstetrics and gynaecology; QMNC = quality of maternal and newborn care; SVB = spontaneous vaginal birth.

Young mothers aged 18-24 years, instrumental vaginal births and CS had a significant lower QMNC Index and coefficients becoming increasingly larger at lower quantiles (-11·7, -10·9, -5·0 for 18-24 years-old mothers; -23·3, -20·5, -15·0 and -28·3, -21·8, -15·3 for instrumental VB and CS respectively).

Discussion

This is the first multicountry study investigating women's perceptions of the quality of health care around the time of childbirth at health facilities across the WHO European region during the COVID-19 pandemic, using a comprehensive set of WHO Standards-based Quality Measures. The study collected data primarily from 12 countries of the WHO European Region and highlighted that even in rich countries in the WHO European Region, during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, many aspects of the QMNC - especially those related to patient-centred respectful care and availability of resources- were reported as substandard from mothers’ perspectives. Notably, but not unexpectedly, large inequalities between countries of the WHO European Region were observed. These inequalities were systematic in their distribution and being potentially preventable, they should be called “inequities”. 29

Notably, very good examples of QMNC were also reported. However, even among countries with the higher observed QMNC Indexes, participant mothers reported some gaps. For example, in Luxemburg, 31·3% of women reported to have been subjected to fundal pressure in instrumental vaginal birth, 42·2% were not asked for consent before vaginal examinations, 12·8% reported that they were not treated with dignity, and 38·5% reported a reduction in the QMNC due to COVID-19 (Supplementary Tables 5-8). The study also pointed out specific gaps. For example (Supplementary Table 7), Swedish mothers reported the highest rate of healthcare workers not wearing PPEs among all countries (64·8%). General shortages in the availability of PPE during the beginning of the pandemic along with varying regional recommendations and stringent efforts to reserve PPEs for suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19 make these findings plausible.30,31

Results of this study are in line with previous reports, showing substantial inequities in key maternal and newborn health care indicators, such as maternal deaths, number of stillbirths, caesarean section and exclusive breastfeeding rates, across countries of the WHO European Region, even before the COVID-19 pandemic.10,13 Previous national reports and surveys have also documented over-use of medical interventions (including episiotomies, labour induction, and fundal pressure), low use of appropriate procedures for pain control, mistreatment of women, shortages of adequate physical and human resources, and high out-of-pocket payments, with large heterogeneity of practices between countries and between institutions in the same country.11, 12, 13, 14, 15,32, 33, 34, 35

The COVID-19 pandemic was of unprecedented magnitude, and the world was largely unprepared to face it. Our study did not aim at comparing data before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, since comparable data are lacking for most countries. Rather, this study aimed at providing a description of the QMNC during the pandemic, using a comprehensive list of 40 WHO Standard-based Quality Measures, which may allow for comparison over time. Future studies should further explore to what extent gaps in the QMNC reported in this study were due to the COVID-19 pandemic, or if they will persist beyond it. Standardized systems to routinely measure and compare all domains relevant to QMNC over time and across countries, especially variables related to the experience of care and respectful maternal care, are still lacking and data on QMNC are often not readily available to inform policy and practice in a timely manner.33, 34, 35, 36, 37 Systems to monitor QMNC across countries and over time are urgently needed, even in the WHO European Region. Such systems should aim to link Quality Measures to the individual sample characteristics, since, as shown in this study, Quality Measures may be affected by patient characteristics.

A strength of the study was the use of a standardized validated questionnaire, which allowed for the first time a comparison between countries, on a set of 40 prioritized Quality Measures based on the WHO Standards.19 The questionnaire explored all domains of the WHO QMNC framework,19 including several measures of respectful maternal care36 and the additional domain of organizational changes due to COVID-19. The sample collected accounted for a considerable proportion of the total number of births expected during the study period, at least for eight countries. The study aimed at collecting the perspective of key service users (ie, mothers), in line with what is recommended to countries by WHO as a crucial strategy to monitor the QMNC.35

A limitation of this study is that the overall sample of women participating in the survey had a relatively high level of education compared to the expected in the overall general population, but it is difficult to estimate how this selection may have affected study findings. Higher women’ s education15,17,24,38 has been reported as associated with receiving better QMNC (and in this scenario our data could overestimate the actual QMNC), but it is also possible that mothers with higher education were more empowered to freely express their views, and were more critical toward the health system thereby under-estimating the QMNC.15,17

Similarly, we cannot exclude that, this being a voluntary survey, the sample was self-selected toward women with a higher interest in participating. However, again it is difficult to estimate how this may have affected results: both mothers with either a positive or a negative experience of care may have had a special interest in reporting their experience. Overall, 89.2% of women who accessed our survey online provided consent to participate, suggesting that many women are willing to provide their perspective, when invited to. Certainly, digital poverty may have reduced access to the survey. In the future other complementary methods of participation which do not rely exclusively on internet access, may be necessary for a more comprehensive sample.

We also acknowledge that this online survey lacked important information on the sample, such as more information on maternal and newborn characteristics and outcomes. When questions for the online survey were prioritized, the study network considered it critical not to overload respondents with too many questions, which may drastically reduce the response rate and the overall data completeness.

We acknowledge that reporting national averages may mask intra-country heterogeneity in findings, while different dissemination periods among countries may also have affected results. This is the first paper produced by the IMAgiNE study network, and more detailed results by country and regions, as well as per periods of the COVID-19 pandemic will be the subject of extensive upcoming publications.

Most of the 40 key Quality Measures included in this survey were primarily binary measures which are relatively easy to recall (eg, early breastfeeding yes/no, informal payments yes/no, etc), which increase reliability and comparability of data. However, as for many other surveys on QMNC, some of the measures (eg, those of respectful maternal care such as respect and dignity, and the question on the overall quality of care in respect to the COVID-19 pandemic) were open to women's subjective judgment. Comparison between countries for subjective measures should be interpreted with caution, acknowledging that individual women's perceptions may be affected by individual and national culture, norms, and expectations.17,38 Evidence has shown that mistreatment of women, including disrespect and abuse, may be normalized and therefore under-reported in some settings,17,38 while in other settings where the population is more empowered and has higher expectations for QMNC, women may be more critical of the health system. For example, data from Spain, one of the three countries with the highest proportion of women reporting having suffered abuses (20·8%), should be interpreted both considering recent large studies reporting high rates (38·3%) of obstetric violence, and co-existing major efforts from many agencies and bodies during the last 15 years in promoting the concept of respectful maternal care.39 Overall, most indicators of QMNC lack robust validation and many are open to subjectivity or recall bias.17,18,34

Overall, this study adds to previous evidence1,10,13,31, 32, 33, 34,37, 38, 39, 40 suggesting that health care around the time of childbirth needs to be driven by evidence-based practices, programmes, and policies, to achieve sustainable maternal and newborn health and wellbeing worldwide. The WHO Standards should be monitored and upheld, including during times of crisis such as the current global pandemic.19,35 Further implementation research is needed to evaluate how to better incorporate service users’ perspective on the QMNC in routine data collection systems, and how to triangulate these data with other indicators such as health outcomes. However, existing evidence should be translated now into appropriate health policies and plans to improve QMNC and reduce inequities in QMNC across the WHO European Region. Policymakers at all levels (individual facility, national, regional, global level) in the health sector and in other related sectors (eg, education and others) need to ensure that all women receive high-quality, evidence-based, equitable, and patient-centred respectful care during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

Contributors

ML conceived the study, with major inputs from EPV, BC and additional input from all other authors.

All authors promoted the surveys and supported the process of data collection.

IM analysed data, with major inputs from ML.

ML wrote the first draft, with major inputs from all authors.

All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

IMAgiNE EURO Study Group

Italy: Giuseppa Verardi,1 Beatrice Zanin,1 Sandra Morano2

Israel: Ilana Chertok,3,4 Rada Artzi-Medvedik5

Latvia: Elizabete Pumpure,6 Dace Rezeberga,6 Agnija Vaska,6 Dārta Jakovicka,7 Paula Rudzīte,7 Elīna Ērmane,8 Katrīna Paula Vilcāne student8

Portugal: Carina Rodrigues9,10, Heloísa Dias11

Russia: Ekaterina Yarotskaya12

Sweden: Verena Sengpiel13

-

1

Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste, Italy

-

2

Medical School and Midwifery School, Genoa University, Genoa, Italy

-

3

Ohio University, School of Nursing, Athens, Ohio, USA

-

4

Ruppin Academic Center, Department of Nursing, Emek Hefer, Israel

-

5

Department of Nursing, The Recanati School for Community Health Professions, Faculty of Health Sciences at Ben-Gurion University (BGU) of the Negev, Israel

-

6

Riga Stradins University Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Rīga, Latvia

-

7

Riga Stradins University Faculty of Medicine, Rīga, Latvia

-

8

Riga Stradins University, Rīga, Latvia

-

9

EPIUnit, Institute of Public Health, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

-

10

Laboratory for Integrative and Translational Research in Population Health (ITR), Porto, Portugal

-

11

Administração Regional de Saúde do Algarve, Algarve, Portugal

-

12

Department of International Cooperation National Medical Research Center for Obs., Gyn. & Perinatology, Moscow, Russia

-

13

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Institute of Clinical Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, Gothenburg University, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all project partners and volunteer mothers who helped in the development of the questionnaire and all women who took their time to respond to this survey despite the burden of the COVID-19 pandemic. We also would like to thank a number of colleagues who volunteered in helping different aspects of the project, as follows:

-

•

Valbona Nushi-Stavileci who helped with survey translation into Albanian.

-

•

Aleksandra Wilk-Przybysz and Małgorzata (Meg) Mielczarek who helped with survey translation into Polish.

-

•

France: Marie-Laure Trudel, Sarah Féron, Gilles Garrouste who helped with the survey dissemination

-

•

Germany: Antonia Leiße, who helped with the survey translation into German and dissemination.

-

•

Italy: Rebecca Lundin for back translation of Italian questionnaires; Elisabetta Danielli from Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo for her technical support on upload and maintenance of questionnaire links on institutional webpage; Michele Bava from Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo for the IT support.

-

•

Portugal: Associação Portuguesa pelos Direitos da Mulher na Gravidez e Parto (APDMGP) for support on survey dissemination.

-

•

Norway: Marit Kongslien for back translation of Norwegian questionnaire.

-

•

Romania: Sinziana Ionita-Ciurez, Ana Maita, Cristina Biciila, Raluca Dumitrescu (members of SAMAS Association) for their commitment on the translation and on the Romanian questionnaire's dissemination.

-

•

Spain: Observatorio de la violencia obstetrica (OVO) - Spain, Medical Anthropology Research Center (MARC, URV) and Institut Català d'Antropologia (ICA) for support on survey dissemination.

-

•

Sweden: David Loum Skantz for his help in survey dissemination.

Funding

This research was funded by the Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste Italy.

Declaration of interests

Céline Miani's position as a post-doctoral researcher is funded by Bielefeld University.

Catarina Barata had a PhD grant FCT/FSE (SFRH/BD/128600/2017) while she was voluntarily writing this article. She is board member, unpaid collaboration, of Associação Portuguesa pelos Direitos da Mulher na Gravidez e Parto (APDMGP).

Daniela Drandić received a salary during the time she was volunteer-writing this article was from a grant from the Erasmus+ programme of the European Commission, regarding a project on parenting support and from a grant from the UNICEF Croatia, regarding a project on online education for pregnant women during COVID. She is a board member of an NGO called Human Rights in Childbirth, and has been for the entire time she worked on this paper.

Dr Emma Sacks has received research funding from the World Health Organization related to the mistreatment of women and newborns in health facilities. The project has no impact on the present manuscript outside of similar topics. She is the former co-chair of the Newborn Health Working Group of the Global Respectful Maternity Care Council.

Other authors have none to declare.

Availability of data

Data can be made available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Disclaimer

The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100268.

Contributor Information

Marzia Lazzerini, Email: marzia.lazzerini@burlo.trieste.it.

Benedetta Covi, Email: benedetta.covi@burlo.trieste.it.

Ilaria Mariani, Email: ilaria.mariani@burlo.trieste.it.

Zalka Drglin, Email: zalka.drglin@nijz.si.

Maryse Arendt, Email: maryse.arendt@pt.lu.

Ingvild Hersoug Nedberg, Email: ingvild.h.nedberg@uit.no.

Helen Elden, Email: helen.elden@gu.se.

Raquel Costa, Email: rqlcosta@gmail.com.

Daniela Drandić, Email: daniela@roda.hr.

Jelena Radetić, Email: jelena.radetic@centarzamame.rs.

Marina Ruxandra Otelea, Email: marina.otelea@umfcd.ro.

Céline Miani, Email: celine.miani@uni-bielefeld.de.

Serena Brigidi, Email: serena.brigidi1@urv.cat.

Virginie Rozée, Email: virginie.rozee@ined.fr.

Barbara Mihevc Ponikvar, Email: barbara.mihevc@nijz.si.

Barbara Tasch, Email: barbara@goubet.eu.

Sigrun Kongslien, Email: sigrun.kongslien@uit.no.

Karolina Linden, Email: karolina.linden@gu.se.

Catarina Barata, Email: acfbarata@gmail.com.

Magdalena Kurbanović, Email: magdakurbi@gmail.com.

Jovana Ružičić, Email: jovana@centarzamame.rs.

Stephanie Batram-Zantvoort, Email: stephanie.zantvoort@uni-bielefeld.de.

Lara Martín Castañeda, Email: laramartin.bcn.ics@gencat.cat.

Elise de La Rochebrochard, Email: roche@ined.fr.

Anja Bohinec, Email: anja.bohinec@nijz.si.

Eline Skirnisdottir Vik, Email: eline.skirnisdottir.vik@hvl.no.

Mehreen Zaigham, Email: mehreen.zaigham@med.lu.se.

Teresa Santos, Email: teresa.santos@universidadeeuropeia.pt.

Lisa Wandschneider, Email: lisa.wandschneider@uni-bielefeld.de.

Ana Canales Viver, Email: acanalvi7@alumnes.ub.edu.

Amira Ćerimagić, Email: cerimagic.a@hotmail.com.

Emma Sacks, Email: esacks@jhsph.edu.

Emanuelle Pessa Valente, Email: emanuelle.pessavalente@burlo.trieste.it.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Chmielewska B, Barratt I, Townsend R, Kalafat E, van der Meulen J, Gurol-Urganci I, O'Brien P, Morris E, Draycott T, Thangaratinam S, Le Doare K, Ladhani S, von Dadelszen P, Magee L, Khalil A. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00079-6. S2214-109X(21)00079-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kc A, Gurung R, Kinney MV, Sunny AK, Moinuddin M, Basnet O, Paudel P, Bhattarai P, Subedi K, Shrestha MP, Lawn JE, Målqvist M. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic response on intrapartum care, stillbirth, and neonatal mortality outcomes in Nepal: a prospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(10):e1273–e1281. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30345-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ceulemans M, Verbakel JY, Van Calsteren K, Eerdekens A, Allegaert K, Foulon V. SARS-CoV-2 Infections and Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Pregnancy and Breastfeeding: Results from an Observational Study in Primary Care in Belgium. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6766. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravaldi C, Wilson A, Ricca V, Homer C, Vannacci A. Pregnant women voice their concerns and birth expectations during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Women Birth. 2020 Jul 13 doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.07.002. S1871-5192(20)30280-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naurin E, Markstedt E, Stolle D, Enström D, Wallin A, Andreasson I, Attebo B, Eriksson O, Martinsson K, Elden H, Linden K, Sengpiel V. Pregnant under the pressure of a pandemic: a large-scale longitudinal survey before and during the COVID-19 outbreak. Eur J Public Health. 2021;31(1):7–13. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckaa223. 6000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Regional office for Europe . World Health Organization; 2020. COVID-19 and breastfeeding Position paper.https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/437788/breastfeeding-COVID-19.pdf Available at. (accessed April 16, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2020. Maintaining essential health services: operational guidance for the COVID-19 context.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-essential-health-services-2020.1 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Confederation of Midwives Women's Rights in Childbirth Must be Upheld During the Coronavirus Pandemic. Available at https://www.internationalmidwives.org/assets/files/news-files/2020/03/icm-statement_upholding-womens-rights-during-covid19-5e83ae2ebfe59.pdf accessed Jan 19, 2021

- 9.Human Rights Violations in Pregnancy, Birth and Postpartum During the COVID-19 Pandemic. (2020, San Francisco: Human Rights in Childbirth).

- 10.Euro-Peristat Project. European Perinatal Health Report. Core indicators of the health and care of pregnant women and babies in Europe in 2015. Available at https://www.europeristat.com/images/EPHR2015_web_hyperlinked_Euro-Peristat.pdf (accessed Jan 19, 2020)

- 11.Harrison S, Alderdice F, Henderson J, Quigley MA. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford; Oxford: 2020. You and Your Baby: A national survey of health and care. ISBN: 978-0-9956854-5-1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Direzione Generale della digitalizzazione, del Sistema Informativo Sanitario e della Statistica. Ufficio di Statistica. Certificato di assistenza al parto (CeDAP). Analisi dell'evento nascita -Anno 2017. Roma, 2020. Available at http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2931_allegato.pdf (accessed Dic 12, 2020)

- 13.Babies Born Better (BB) Improving childbirth experience, http://www.babiesbornbetter.org/surveyportal/

- 14.World Health Organization Regional office for Europe . World Health Organization; 2020. Assessments of sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health in the context of universal health coverage in six countries in the WHO European Region. A synthesis of findings from the country reports.https://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/assessments-of-sexual,-reproductive,-maternal,-newborn,-child-and-adolescent-health-in-the-context-of-universal-health-coverage-in-six-countries-in-the-who-european-region-a-synthesis-of-findings-from-the-country-reports-2020 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazzerini M, Valente EP, Covi B, et al. Use of WHO standards to improve quality of maternal and newborn hospital care: a study collecting both mothers’ and staff perspective in a tertiary care hospital in Italy. BMJ Open Quality. 2019;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scambia G, Viora E, Colacurci N, Longhi C. Patient-reported experience of delivery: A national survey in Italy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;224:196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, Lutsiv O, Makh SK, Souza JP, Aguiar C, Saraiva Coneglian F, Diniz AL, Tuncalp O, et al. The Mistreatment of Women during Childbirth in Health Facilities Globally: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. PLoS Med. 2015;12(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847. discussion e1001847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khosla R, Zampas C, Vogel JP, Bohren MA, Roseman M, Erdman JN. International Human Rights and the Mistreatment of Women During Childbirth. Health Hum Rights. 2016;18(2):131–143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities; 2016. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/improving-mnh-health-facilities/en/

- 20.Lazzerini et al. Validation of a questionnaire based on WHO Standards to measure women's view on the quality of maternal and newborn care at facility level in the WHO European Region. BMJ Open [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazzerini M, Mariani I, Semenzato C, Valente EP. Association between maternal satisfaction and other indicators of quality of care at childbirth: a cross-sectional study based on the WHO standards. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lazzerini M, Semenzato C, Kaur J, Covi B, Argentini G. Women's suggestions on how to improve the quality of maternal and newborn hospital care: a qualitative study in Italy using the WHO standards as framework for the analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):200. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-02893-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, et al. Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8(2):94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Intrapartum care for healthy women and babies. (NICE clinical guideline 190). Published: 01/12/2014. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg190/resources/intrapartum-care-for-healthy-women-and-babies-pdf-35109866447557.

- 26.Afulani PA, Phillips B, Aborigo RA, Moyer CA. Person-centred maternity care in low-income and middle-income countries: analysis of data from Kenya, Ghana, and India. Lancet Glob Health. 2019 Jan;7(1):e96–e109. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30403-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Semaan A, Audet C, Huysmans E, Afolabi B, Assarag B, Banke-Thomas A, Blencowe H, Caluwaerts S, Campbell OMR, Cavallaro FL, Chavane L, Day LT, Delamou A, Delvaux T, Graham WJ, Gon G, Kascak P, Matsui M, Moxon S, Nakimuli A, Pembe A, Radovich E, van den Akker T, Benova L. Voices from the frontline: findings from a thematic analysis of a rapid online global survey of maternal and newborn health professionals facing the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Glob Health. 2020 Jun;5(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koenker R. Quantile Regression. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arcaya MC, Arcaya AL, Subramanian SV. Inequalities in health: definitions, concepts, and theories. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:27106. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.27106. Published 2015 Jun 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ribeiro, S. Emergency efforts are needed otherwise Covid healthcare can be stopped (Article in Swedish). Dagens Nyheter [Internet]. 2020 Mar 20 [cited 2021 May 4]. Available from: https://www.dn.se/debatt/akuta-insatser-kravs-annars-kan-coronavard-stoppas/

- 31.Ludvigsson, JF. The first eight months of Sweden's COVID-19 strategy and the key actions and actors that were involved. Acta Paediatr [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.OECD/European Union . OECD Publishing; Paris: 2020. Health at a Glance: Europe 2020: State of Health in the EU Cycle. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller S, Abalos E, Chamillard M, Ciapponi A, Colaci D, Comandé D, Diaz V, Geller S, Hanson C, Langer A, Manuelli V, Millar K, Morhason-Bello I, Castro CP, Pileggi VN, Robinson N, Skaer M, Souza JP, Vogel JP, Althabe F. Beyond too little, too late and too much, too soon: a pathway towards evidence-based, respectful maternity care worldwide. Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2176–2192. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31472-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larson E, Sharma J, Nasiri K, Bohren MA, Tunçalp Ö. Measuring experiences of facility-based care for pregnant women and newborns: a scoping review. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(11) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaw D, Guise JM, Shah N, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Joseph KS, Levy B, Wong F, Woodd S, Main EK. Drivers of maternity care in high-income countries: can health systems support woman-centred care? Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2282–2295. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31527-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescents' Health, 2016-2030. Geneva; 2015. http://www.who.int/life-course/partners/global-strategy/global-strategy-2016-2030/en/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Afulani PA, Buback L, McNally B, Mbuyita S, Mwanyika-Sando M, Peca E. A Rapid Review of Available Evidence to Inform Indicators for Routine Monitoring and Evaluation of Respectful Maternity Care. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2020;8(1):125–135. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rishard M, Fahmy FF, Senanayake H, Ranaweera AKP, Armocida B, Mariani I, Lazzerini M. Correlation among experience of person-centered maternity care, provision of care and women's satisfaction: Cross sectional study in Colombo, Sri Lanka. PLoS One. 2021;16(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mena-Tudela D, Iglesias-Casás S, González-Chordá VM, Cervera-Gasch Á, Andreu-Pejó L, Valero-Chilleron MJ. Obstetric Violence in Spain (Part I): Women's Perception and Interterritorial Differences. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):7726. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ceschia A, Horton R. Maternal health: time for a radical reappraisal. Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2064–2066. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31534-3. Epub 2016 Sep 16. PMID: 27642025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.