Learning objectives.

By reading this article, you should be able to:

-

•

Describe affinity, potency and efficacy.

-

•

Draw graphs to illustrate drug potency and efficacy.

-

•

Explain how the response of a partial agonist drug can vary between tissues with different receptor reserves and why this could be important.

-

•

Discuss the potential therapeutic benefits of mixed and biased agonists using opioids as examples.

Key points.

-

•

There are four main classes of receptors: (i) G-protein-coupled receptors; (ii) ligand-gated ion channels; (iii) intracellular receptors; and (iv) tyrosine kinase-coupled receptors.

-

•

Drug-receptor interactions are characterised by affinity, potency and efficacy.

-

•

Drugs with different efficacies (full agonist, partial agonist, antagonist) offer broad treatment options.

-

•

Using opioids as exemplars, drugs that target multiple members of the receptor family or show bias towards different parts of the signalling pathway have potential advantages in terms of their analgesic effects.

This article reviews the basics of drug–receptor interactions: affinity, potency and efficacy. We provide a fresh focus on drug efficacy for current and future therapeutics using opioids as examples. Shifts in drug design have led to some new and noteworthy pharmacology concepts including inverse and biased agonism. In addition, the old concept of selectivity is being reconsidered. The design of novel opioids, for example is moving away from developing highly selective ligands for a single opioid receptor towards drugs targeting multiple opioid receptor sites (i.e. mixed opioids). Drugs such as cebranopadol are the result of such new design strategies, which result in a drug that targets multiple opioid receptors to provide robust analgesia with an improved profile of adverse effects. The development of biased agonists is another interesting area, with application in cardiovascular disease and a possible but controversial application in pain medicine.1, 2, 3 Innovative, developmental and non-receptor approaches in drug development are also discussed.

Drug targets

The four principle protein targets for drug action are4:

-

1.

Enzymes such as cyclooxygenase on which NSAIDS act to produce analgesia and anti-inflammatory actions, phosphodiesterases (PDEs) on which inhibitors such as sildenafil and tadalafil act to treat erectile dysfunction (PDE-5 inhibitors), and acetylcholinesterase on which neostigmine acts to reverse neuromuscular block.

-

2.

Ion channels such as voltage-gated Ca2+ channels that are blocked by calcium channel blockers such as amlodipine.

-

3.

Cell membrane carrier proteins, for example monoamine reuptake transporters where inhibition increases the concentration of one, or more, of three major monoamine neurotransmitters: serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine), noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and dopamine.

-

4.

Receptors, which will be the focus of the remainder of this article.

Receptors

Receptors are target proteins responding to the binding of chemical messenger(s) to modify a cellular response. They are able to respond to various messengers and facilitate complex and coordinated communications within the body. These various messengers include neurotransmitters, hormones, chemokines and exogenous therapeutic drugs. Receptors can be targeted by drugs, which either mimic or antagonise endogenous mediators.

Receptors are located on the cell membrane, except for steroid receptors, which are located in the cytosol and translocate to the nucleus. Receptors typically do not have specificity for one ligand but selectivity. There are several types of receptors: ligand-gated ion channels, tyrosine kinase-coupled, steroid receptors and G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Images and facts for the different receptor types regarding how they function to produce changes in cellular activity. GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid type A; MOP, mu opioid receptor; CNS, central nervous system.

G-protein coupled receptors

G-protein coupled receptors represent the largest class of membrane proteins in the human genome. Around half of GPCRs have a sensory function and facilitate pheromone signalling, light perception, olfaction and taste. The remaining GPCRs are non-sensory and bind ligands such as peptides, larger proteins and small molecules, including drugs. The majority of clinical drugs target GPCRs. Notable exceptions in anaesthesia involve drugs that interact with ligand-gated ion channels, for example neuromuscular blocking drugs (NMBDs) with nicotinic cholinergic receptors (ligand-gated Na+ channels) and general anaesthetic agents with gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) (ligand-gated Cl– channels) and NMDA (glutamate-gated channels) receptors. Opioid receptors represent an example of a GPCR, a group of receptors that are targeted by opioid analgesics used in clinical practice.

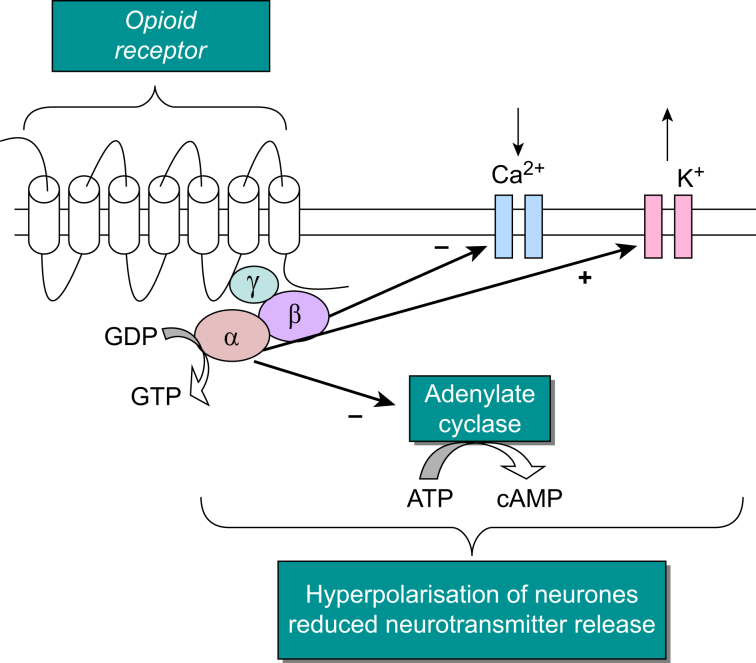

All GPCRs have a common structure; an extracellular N terminus, an intracellular C terminus and seven transmembrane domains joined by intracellular and extracellular loops. The binding of a ligand to a GPCR results in structural changes to the receptor that enable it to interact with the intracellular G-protein, which is formed of α, β and γ subunits. After this interaction between receptor and G-protein, the G-protein separates into subunits, a Gα-subunit and βγ complex, both of which interact with second messenger pathways (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Depiction of the intracellular responses and pathways after the binding of an opioid agonist to a G-protein-coupled opioid receptor, for example morphine binding the (μ)MOP receptor. Image adapted from McDonald and Lambert.5 ATP, adenosine triphosphate; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; GDP, guanosine diphosphate; GPCR, G-protein coupled receptor; GTP, guanosine-5′-triphosphate; MOP, mu opioid receptor.

After ligand binding and heterotrimeric G-protein interaction, this interaction relays an extracellular message into the cell modulating cellular function.5 This process is possible as the heterotrimeric G-protein, to which the receptor couples, is able to interact with a number intracellular processes or targets such as inhibiting or stimulating enzymes, for example adenylyl cyclase or modulating the gating of ion channels. The first messenger is the endogenous/exogenous mediator (hormone, neurotransmitter or drug) whereas downstream intracellular signalling molecules are referred to as second messengers (e.g. cyclic adenosine monophosphate [cAMP], calcium, diacylglycerol [DAG]).1,4,5 Opioid receptors further couple to mitogen-activated protein kinases, including extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1 and 2, p38 and Jun N-terminal kinase, through both G-protein-dependent pathways and G-protein-independent β-arrestin pathways.

Drug–receptor interactions

The interaction of a drug with a particular receptor is described by the terms affinity, potency and efficacy. As well as for G-protein coupled receptors these terms are relevant to other receptor classes such as ligand-gated channels, tyrosine kinase-linked receptors and nuclear receptors, although each has particular features. For example ligand-gated ion channels are allosteric membrane proteins that change between closed and open conformations; drugs influence the gating equilibrium constant between closed-open through having a difference in affinity for these two shapes (closed and open). Here we describe these terms in relation to the opioid family (G-protein coupled receptors) as the main examples. There are several similarities between the modelling for drug–receptor action and substrate–enzyme interaction, but there are also several important differences.

Affinity

The initial phase of receptor interaction is the binding of the drug to the receptor, which can be modelled and described by a number of terms. A drug's affinity (strength of binding) for a given receptor is the product of its association with receptor together with the rate of dissociation of drug–receptor complex. Affinity is described by KD, the equilibrium dissociation constant, which is the concentration of drug needed to occupy 50% of the available receptors. High affinity drugs only need a low concentration to reach 50% occupancy of the available receptors; growth factors are an example of this. Conversely, low affinity drugs would require higher concentrations in order to achieve 50% occupancy of the total number of receptors. The nature by which some drugs and ligands bind is so strong that it is essentially irreversible and there is either no dissociation or very little; the endogenous cyclic peptide urotensin II, a vasoactive peptide, binds to the urotensin II receptor in a way that is essentially irreversible.4,6

Radioligand binding experiments are most often used to characterise receptor binding and make measurements of KD. In these experiments, a fixed concentration of receptors is incubated with increasing concentrations of a radiolabelled form of the drug and the amount of binding measured.

Binding of a drug or ligand with a receptor does not always result in activation of the receptor; when a drug or ligand has affinity without efficacy, it is called an antagonist. Antagonists still cause a response, although this is through blocking the actions of agonists. Antagonists bind with a range of affinities, and binding can be either reversible or irreversible in nature. Consider the opioid antagonist naloxone. This drug has high affinity at all three classical opioid receptors, MOP (μ), DOP (δ), KOP (κ), and is used to reverse the effects of opioid overdose.7 Naloxone does not have binding affinity for the nociception/orphanin FQ (NOP) receptor, and therefore is unable to antagonise this receptor.

Agonists, potency and efficacy

Agonists bind to receptors to induce conformational changes within the receptor and a cascade of functional biological responses. The ability of a drug to stimulate this process, to turn receptor binding into biological response, is termed efficacy. The efficacy of a drug is the response generated per unit drug–receptor complex. An example of this would be fentanyl binding to the MOP receptor, leading to inhibition of nerve transmission along the pain pathway and analgesia.

As drug concentration increases, the number of occupied receptors increases along with response until 100% occupancy and a maximal response is reached. The concentration range or dose range over which a drug produces a response is termed potency, measured using a concentration or dose-response curve and expressed as the EC50 or ED50, the effective concentration or dose to cause 50% of the maximal response. It is important to highlight the distinction between dose and concentration, with dose being the mass of a drug, that is the mass of drug given to a patient (typically in milligrams or micrograms) and concentration being a mass of drug in a given volume (i.e. nanomolar or micromolar). In clinical practice, dose is the most frequently used, so in modelling ED50 is most appropriate.

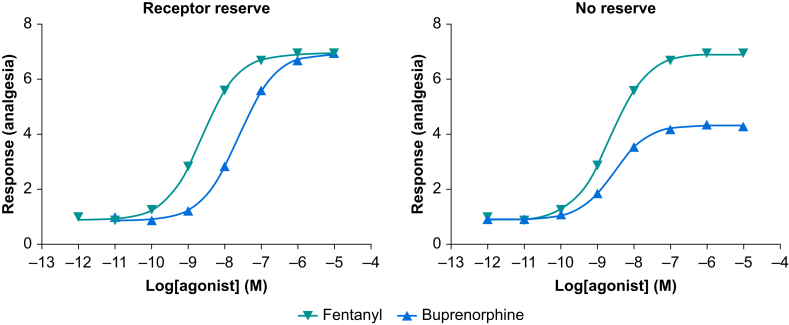

Agonists that produce the maximal tissue response are termed a full agonist whereas those that elicit less than the maximal response are termed partial agonists. Some drugs produce the opposite effect to a classical agonist and reduce certain cellular processes below a standard resting state or tone; these drugs are termed inverse agonists. Most inverse agonists are experimental drugs, and there are inverse agonists relevant to anaesthesia such as the beta-carbolines that act at benzodiazepine receptors but are anxiogenic rather than anxiolytic. The action of an inverse agonist can be inhibited (shift the response curve to the right) by a simple competitive antagonist. In terms of opioid drugs, fentanyl is a full agonist and buprenorphine would be considered a partial agonist.8,9 However, drug efficacy is more complicated than this, and it is typically not possible to determine drug efficacy directly by measuring the maximum response of the drug. Indeed, it would not be correct to use a drug's maximal tissue response as a measure of efficacy (in this article we will model ‘whole human’ clinically relevant responses). For example if a series of different drugs all returned a maximum response in a given tissue, they may not all have the same efficacy or necessarily be full agonists. In order to appreciate how this could be, it is important to realise that in many receptor systems a full agonist would not need to reach 100% occupancy of the available receptors to generate a maximal response, meaning that this particular system would have a receptor reserve or spare receptors. Returning to the MOP receptor and the full and partial agonists fentanyl and buprenorphine, in a system with a receptor reserve both would be able to return the maximal tissue response, albeit at different fractional receptor occupancies. However, if conditions changed and the receptor number was reduced, or the drugs were used in a different system lacking a receptor reserve, the full agonist would continue to return a maximal response whereas the full tissue response for the partial agonist would be less (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Hypothetical concentration response curves for the full MOP agonist fentanyl and the partial MOP agonist buprenorphine in a tissue preparation (receptor system) containing a receptor reserve (i.e. a high density of receptors, not all of which need to be occupied to give a maximal tissue response) and a tissue preparation where there is no receptor reserve (i.e. 100% occupancy of receptors is needed to generate a maximal tissue response). The functional response of the lower efficacy partial agonist buprenorphine is susceptible to the change in receptor density between tissues whereas the higher efficacy of the full agonist fentanyl results in a maximal functional response in both tissues. MOP, μ-opioid receptor.

Another important pharmacological phenomenon related to drug efficacy is the fact that partial agonists can antagonise the actions of full agonists. Again, using buprenorphine and fentanyl as examples, in a receptor system with no reserve, when given separately fentanyl would return the system's maximum response whereas buprenorphine would not. If fentanyl was given in the presence of buprenorphine the response to fentanyl would be diminished, as a proportion of the receptors would be occupied by the lower efficacy drug. In this case, a higher dose of fentanyl would be needed in order to restore the maximal drug response.

Overall affinity is a measure of the ability of a drug to bind to a receptor, efficacy is the ability of the drug–receptor interaction to produce a response and potency represents a combination of these two characteristics although it is not necessarily directly proportional to affinity or efficacy.

Antagonists

Antagonists have affinity for receptors but no efficacy and therefore do not activate second messenger pathways. Antagonists block the action of agonists and therefore prevent agonist action. Antagonists can be competitive such that the binding is reversible and surmountable, or non-competitive when the binding is irreversible and insurmountable.

Naloxone is a competitive opioid antagonist and has high affinity at MOP receptors. As such it can block the actions of MOP agonists, such as diamorphine, and is used to treat opioid overdose in this manner.10 Competitive antagonists bind to the same site on the receptor as agonists. This blockade can be overcome by increasing the concentration of agonist, to outcompete the antagonist. The concentration of agonist needed to outcompete an antagonist will, in part, relate to antagonist affinity.

Flumazenil is an example of a selective and competitive antagonist of GABAA receptors (an inhibitory ligand-gated ion channel). This drug can be used in treatment of benzodiazepine overdose where it acts by competitive inhibition at the GABAA receptor benzodiazepine binding site.

For non-competitive antagonists, increasing the concentration of agonist does not restore the original response as the binding sites of the two ligands are different. Ketamine is a non-competitive antagonist of NMDA receptors, an ionotropic glutamate receptor. Ketamine antagonism is through blockage of the channel, whereas the agonist binding site for the NMDA receptor is located on the extracellular surface (the agonist and antagonist bind at different sites).

An innovative, non-receptor-mediated mechanism developed for reversing drug action is seen with sugammadex, which is able to reverse and terminate the action of the NMBD rocuronium by encapsulating the drug.

Ligand bias

There is much interest in ligand bias, which goes by a variety of names including functional selectivity. As stated, when receptors are activated by a drug they engage a variety of signalling events, the second messenger pathways; some of these pathways (G-protein) lead to desirable responses such as analgesia for opioid drugs, whereas others are responsible for adverse effects such as tolerance.1,3 It is possible through gene targeting techniques to produce mutant mice deficient for specific genes, for example strains of mice lacking a gene (knockout) that would encode a specific opioid receptor or parts of its signal cascade. In experimental animals in which the arrestin signalling molecule has been genetically knocked out or removed, morphine produces analgesia with reduced adverse effects. Therefore opioid drugs that are biased to G-protein signalling and do not activate arrestin signalling should produce a more favourable behavioural response (Fig. 4). The existence of bias at opioid receptors is controversial and has been questioned.

Fig 4.

Response profiles for unbiased and biased agonists acting at the MOP receptor. (a) An unbiased agonist would have efficacy for both the G–protein pathway (green) and beta–arrestin pathway (red) leading to analgesia and adverse effects. (b) A drug with bias for the G-protein signalling pathway, would lead to analgesia but with reduced adverse effects. (c) A drug with a bias for the β-arrestin pathway would lead a higher incidence of adverse effects and reduced analgesic efficacy, taken from Azzam and colleagues.1 MOP, μ-opioid receptor.

The novel opioid oliceridine (Olinvyk) is an example of a putative biased agonist. In laboratory experiments this ligand activates G-protein signalling pathways over arrestin pathways and therefore oliceridine differs from morphine in receptor phosphorylation, receptor internalisation and arrestin recruitment, and as such has an improved adverse effect profile.11 In clinical studies oliceridine has been shown to produce analgesia with improved respiratory and GI safety profile leading to recent Food and Drug Administration approval.12 However, in a series of carefully conducted laboratory experiments, oliceridine has been shown to exhibit partial agonist activity.13 This could manifest as high efficacy at the G-protein (producing analgesia) and low efficacy at the arrestin pathway (potentially supporting adverse effects); this is partial agonism rather than bias.

Multifunctional opioids

Buprenorphine is a multifunctional opioid analgesic also used in the treatment of opioid dependency.8,9 Its pharmacology is that of a mixed opioid with partial agonism at MOP and NOP, and low partial agonist activity at DOP and KOP. In clinical practice, buprenorphine acts with high analgesic efficacy, providing analgesia on a par with full MOP agonists and importanly with no upper limit of effect. Although this suggests that buprenorphine is a full agonist, a ceiling effect of buprenorphine is seen regarding respiratory suppression. This indicates that buprenorphine is actually a high-efficacy partial agonist, or there is a large receptor density or reserve in pain pathways leading to analgesia.

Opioid receptor coactivation has also been shown to reduce many of those adverse effects experienced with opioids used in clinical practice that solely target MOP receptors. This is especially the case for coactivation of the MOP and NOP receptor. Recent drug development has led to the production of the mixed opioid/NOP drug, cebranopadol, which has efficacy in both nociceptive and importantly in neuropathic animal models of pain.14 Significantly when tested in animal models, the development of tolerance, relative to morphine, is substantially reduced. Furthermore, there is little evidence to show that cebranopadol leads to respiratory depression in animals and in humans. Clinical evaluation of cebranopadol indicates efficacy in diabetic polyneuropathy, chronic lower back pain and cancer with a reduced adverse effect profile.15,16

Returning to buprenorphine, this mixed action, variable efficacy opioid has further implications regarding activation of reward pathways and abuse liability. At higher doses buprenorphine attenuated alcohol consumption through activation of the NOP receptor and the inhibitory action this has on the reward pathways.

Summary

Therapeutic drug interaction is mainly described by ligand–receptor interactions, although there are high profile examples of ligand–enzyme interaction in anaesthesia such as cholinesterase inhibitors. In addition, sugammadex, the neuromuscular blocking agent reversal drug, reverses neuromuscular block by encapsulation of rocuronium and vecuronium. Ligand–receptor interaction is defined by affinity (strength of interaction), and the consequences of that interaction is described by potency (dose range over which the effect is produced) and efficacy (effectively the size of the response). Agonists and antagonists have affinity, but agonists produce a functional response that can be ‘standard’ or inverse. Antagonists reverse the effects of agonists in a competitive or non-competitive (also irreversible) manner, and there are examples of all classes in drugs used in anaesthesia and pain medicine.

MCQs

The associated MCQs (to support CME/CPD activity) will be accessible at www.bjaed.org/cme/home by subscribers to BJA Education.

Declaration of interests

DGL is chair of the board of the British Journal of Anaesthesia, He is also a non-executive director of Cellomatics and has previously has held consultancy and received funding from Grunenthal. JM declares no conflicts of interest.

Biographies

DavidLambert BSc (Hons), PhD, SFHEA, FBPhS, FRCA is professor of anaesthetic pharmacology and dean of the Doctoral College at the University of Leicester. His research interests predominantly relate to peptides and their receptors, with emphasis on opioids, pain, immune function and angiogenesis.

John McDonald BSc (Hons), PGDip, PhD, FHEA, works as an experimental officer at the University of Leicester. His current research interests include the role of mixed opioids in pain and the non-classical opioid receptor nociceptin/orphanin FQ.

Matrix codes: 1A02, 2E03, 3E00

References

- 1.Azzam A.A.H., McDonald J., Lambert D.G. Hot topics in opioid pharmacology: mixed and biased opioids. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:e136–e145. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanczyk M.A., Kandasamy R. Biased agonism: the quest for the analgesic holy grail. PAIN Rep. 2018;3 doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wootten D., Christopoulos A., Marti-Solano M., et al. Mechanisms of signalling and biased agonism in G protein-coupled receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19:638–653. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambert D.G. Drugs and receptors. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2006;4:181–184. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonald J., Lambert D.G. Opioid receptors. BJA Educ. 2015;15:219–224. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pacifico S., Kerckhoffs A., Fallow A.J., et al. Urotensin-II peptidomimetic incorporating a non-reducible 1,5-triazole disulfide bond reveals a pseudo-irreversible covalent binding mechanism to the urotensin G-protein coupled receptor. Org Biomol Chem. 2017;15:4704–4710. doi: 10.1039/c7ob00959c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietis N., Rowbotham D.J., Lambert D.G. Opioid receptor subtypes: fact or artifact? Br J Anaesth. 2011;107:8–18. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cowan A. In: Buprenorphine: combating drug abuse with a unique opioid. Lewis J., Cowan A., editors. Wiley; New York: 1995. Update of the general pharmacology of buprenorphine; pp. 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gudin J., Fudin J. A Narrative pharmacological review of buprenorphine: a unique opioid for the treatment of chronic pain. Pain Ther. 2020;9:41–54. doi: 10.1007/s40122-019-00143-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans L.E.J., Roscoe P., Swainson C.P., et al. Treatment of drug overdosage with naloxone, a specific narcotic antagonist. Lancet. 1973;I:452–455. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)91879-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azevedo Neto J., Costanzini A., De Giorgio R., Lambert D.G., Ruzza C., Calò G. Biased versus partial agonism in the search for safer opioid analgesics. Molecules. 2020;25:3870. doi: 10.3390/molecules25173870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert D.G., Calo G. Approval of oliceridine (TRV130) for intravenous use in moderate to severe pain in adults. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:E473–E474. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillis A., Gondin A.B., Kliewer A., et al. Low intrinsic efficacy for G protein activation can explain the improved adverse effect profiles of new opioid agonists. Sci Signal. 2020;13 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaz3140. eaaz3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calo G., Lambert D.G. Nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor ligands and translational challenges: focus on cebranopadol as an innovative analgesic. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:1105–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christoph A., Eerdekens M.-H., Kok M., Volkers G., Freynhagen R. Cebranopadol, a novel first-in-class analgesic drug candidate: first experience in patients with chronic low back pain in a randomized clinical trial. Pain. 2017;158:1813–1824. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koch E.D., Kapanadze S., Eerdekens M.-H., et al. Cebranopadol, a novel first-in-class analgesic drug candidate: first experience with cancer-related pain for up to 26 weeks. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58(3):390–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional general reading

- 1.Rang H.P., Ritter J.M., Flower R.J., Henderson G., editors. Rang and dales pharmacology. 8th Edn. Elsevier; 2015. [Google Scholar]