Abstract

Context

Advances in systemic agents have increased overall survival for men diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer. Additional cytoreductive prostate treatments and metastasis-directed therapies are under evaluation. These confer toxicity but may offer incremental survival benefits. Thus, an understanding of patients’ values and treatment preferences is important for counselling, decision-making, and guideline development.

Objective

To perform a systematic review of patients’ values, preferences, and expectations regarding treatment of metastatic prostate cancer.

Evidence acquisition

The MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL databases were systematically searched for qualitative and preference elucidation studies reporting on patients’ preferences for treatment of metastatic prostate cancer. Certainty of evidence was assessed using Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) or GRADE Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research (CERQual). The protocol was registered on PROSPERO as CRD42020201420.

Evidence synthesis

A total of 1491 participants from 15 studies met the prespecified eligibility for inclusion. The study designs included were discrete choice experiments (n = 5), mixed methods (n = 3), and qualitative methods (n = 7). Disease states reported per study were: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in nine studies (60.0%), metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer in two studies (13.3%), and a mixed cohort in four studies (26.6%). In quantitative preference elicitation studies, patients consistently valued treatment effectiveness and delay in time to symptoms as the two top-ranked treatment attributes (low or very low certainty). Patients were willing to trade off treatment-related toxicity for potential oncological benefits (low certainty). In qualitative studies, thematic analysis revealed cancer progression and/or survival, pain, and fatigue as key components in treatment decisions (low or very low certainty). Patients continue to value oncological benefits in making decisions on treatments under qualitative assessment.

Conclusions

There is limited understanding of how patients make treatment and trade-off decisions following a diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer. For appropriate investment in emerging cytoreductive local tumour and metastasis-directed therapies, we should seek to better understand how this cohort weighs the oncological benefits against the risks.

Patient summary

We looked at how men with advanced (metastatic) prostate cancer make treatment decisions. We found that little is known about patients’ preferences for current and proposed new treatments. Further studies are required to understand how patients make decisions to help guide the integration of new treatments into the standard of care.

Keywords: Metastatic prostate cancer, Metastasis-directed therapy, Oligometastatic, Discrete choice experiment, Choice behaviour, Cytoreductive, Stereotactic ablative radiation therapy, Stereotactic radiotherapy

Take Home Message

A systematic review of patients’ values, preferences, and expectations for treatment of metastatic prostate cancer revealed that treatment effectiveness and delay in time to symptoms were consistently valued as the two most important attributes in quantitative studies (low or very low certainty). In qualitative studies, patients identified cancer progression and/or survival, pain, and fatigue as key (low or very low certainty). Greater understanding of how patients make trade-off decisions is needed for appropriate investment in emerging cytoreductive local tumour and metastasis-directed therapies.

1. Introduction

In contrast to localised prostate cancer, patients with metastatic prostate cancer have distant spread of disease that is not curable [1]. This disease state has primarily been managed using androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) via medical or surgical castration [1]. In isolation, this intervention can lead to disease progression from metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC) to the androgen-independent state of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) within 11–18 mo, limiting overall survival (OS) [2], [3].

Recent advances in systemic therapy (eg, docetaxel, abiraterone acetate, enzalutamide, and apalutamide) have resulted in a dramatic improvement in median OS for patients with mHSPC at 4.8 yr [4], [5], [6], [7]. To gain a further oncological benefit, there has been a move to explore local cytoreductive treatments of the primary prostate tumour and its metastases in both mHSPC and mCRPC [1], [8], [9]. Research is particularly focused on patients with a limited number of metastases, or oligometastatic disease [10]. Local prostate interventions include cytoreductive external beam radiotherapy, cytoreductive radical prostatectomy, and cytoreductive minimally invasive ablative therapies [1], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. In addition, metastasis-directed interventions include stereotactic ablative radiation therapy (SABR), lutetium-177 prostate-specific membrane antigen ligands, radium-223, and metastasectomy [8], [16], [17].

These novel interventions offer significant oncological promise for patients with metastatic prostate cancer [1]. Furthermore, secondary benefits may also arise from the avoidance or delay of second- and third-line systemic agents and their associated toxicity [16], [18]. However, each specific treatment is not without its own treatment-related risk (eg, death) and significant side effects may occur (eg, urinary incontinence, fatigue) [18]. Thus, an understanding of patients’ values and preferences for management is important for patient counselling, decision-making, and guideline development.

This systematic review synthesises the evidence from quantitative preference elicitation studies and qualitative studies reporting on patients’ values, preferences, and expectations in the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer.

2. Evidence acquisition

This prospectively registered (PROSPERO, CRD42020201420) systematic review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines [19], [20].

2.1. Search strategy

A systematic search of the MEDLINE, CINAHL, and Embase databases was carried out, with searches of reference lists of eligible studies to capture additional relevant articles that met our inclusion and exclusion criteria. In brief, the search key terms included “prostate neoplasm/adenocarcinoma” and “metastasis/oligmetastasis/advanced/stage IV/metastatic” and “preference elicitation/discrete choice experiment/stated preference/part-worth utility/functional measurement/paired comparison/pairwise choice/conjoint analysis/conjoint measurement/best-worst scale/contingent valuation/standard gable/time-tradeoff/willingness-to-pay/willingness-to-accept”. The detailed search strategy is provided in the Supplementary material. Search results were limited to the English language and from database inception until November 1, 2020. Review articles, letters, and conference abstracts were excluded at this stage.

The titles and abstracts were reviewed independently by three authors (D.B., M.G.G., V.W.) and adjudicated by a fourth author (M.J.C.). The eligibility criteria were then applied. Any disparities that arose were discussed with the co-authors until agreement was reached. Agreement was verified by a fifth author (H.U.A.) where required. The full text of the remaining articles was reviewed independently by four authors (D.B., M.G.G., V.W., M.J.C.).

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included quantitative preference elicitation studies (ie, discrete choice experiments [DCEs], time trade-off [TTO], and standard gamble) and qualitative studies (ie, interviews, focus groups) reporting on patient preferences for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer. Studies were excluded if they involved (1) nonmetastatic disease or (2) a mixed cohort of disease states (ie, localised and metastatic) or mixed primary cancers if study outcomes were not presented separately by disease state.

2.3. Data extraction

The following data were extracted from all the studies included: reference, authors, publishing journal, year of publication, disease state of the patient population, study size, age, study design or methodology, treatment evaluated, main topic in relation to the study purpose, primary results, and conclusions.

2.4. Assessment of methodological quality

For quantitative studies, methodological quality was assessed using the Purpose, Respondents, Explanation, Findings, and Significance (PREFS) quality assessment checklist, which was developed to assess the quality of studies in systematic reviews of patient preference literature (Supplementary Table 1) [21]. For qualitative studies, methodological quality was assessed using the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) criteria (Supplementary Table 4) [22].

2.5. Risk of bias

For quantitative studies, risk of bias (RoB) was assessed using an RoB tool covering (1) sample selection, (2) response (or attrition) rate, (3) choice and administration of the methodology, (4) outcome (or health state) presentation, and (5) respondent understanding and data analysis (Supplementary Table 2). In accordance with previous systematic reviews, high RoB was assigned when the measurement instrument was not valid. If the measurement instrument was valid, RoB was designated as low if there were no individual items marked as high RoB and as moderate if not more than two items had moderate RoB [23]. For qualitative studies, RoB was assessed using the SRQR criteria (Supplementary Table 4) [22]. Studies with a total score of less than 20 were deemed to have high methodological limitation (RoB).

2.6. Assessment of certainty of evidence

The certainty of evidence presented was assessed using Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) and GRADE Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research (CERQual) for quantitative and qualitative studies, respectively [24], [25].

2.7. Data analysis

A narrative synthesis (quantitative studies) and a thematic analysis (qualitative studies) of the collected data were undertaken with presentation of an interpretation of major findings in the context of the current field [26]. All discrete data points were analysed using SPSS version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A meta-analysis of quantitative studies was not performed given the heterogeneous pool of study populations, designs, and outcomes reported.

3. Evidence synthesis

3.1. Quantity of evidence and characteristics of the studies included

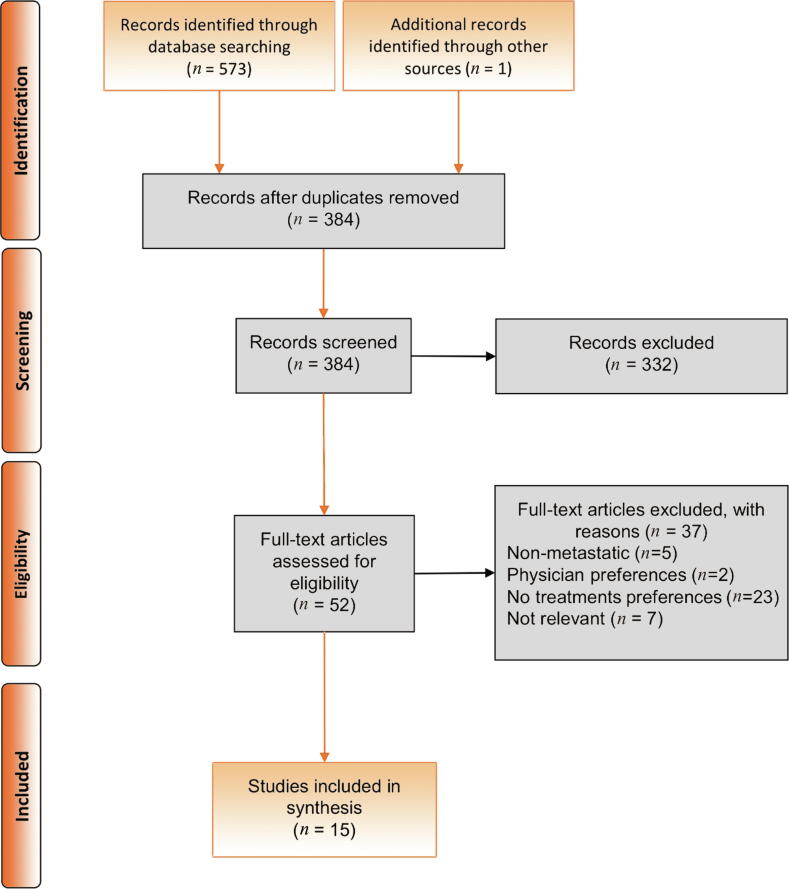

Of the 573 articles identified, 15 studies with a total of 1491 participants met the prespecified eligibility for inclusion in this systematic review, as outlined in the PRISMA-P flow diagram (Fig. 1) [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41]. The mean number of participants per study was 99 (standard deviation [SD] 117.14). The study designs reported for the articles included were DCEs (n = 5), mixed methods (n = 3), and qualitative methods (n = 7; Table 1). The mean age reported for participants ranged from 69.1 to 75.4 yr. The disease state of the participants was mCRPC in nine studies (60.0%), mHSPC in two studies (13.3%), and a mixed mCRPC/mHSPC cohort in four studies (26.6%).

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flowchart.

Table 1.

Characteristics and design of the studies included

| No. | Study | Analysis | Design | Setting | Sample size (n) | Mean age, yr (SD) | Disease state | Primary focus | Treatment(s) evaluated | Funding | PREFS/ SRQR score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | de Freitas 2019 [27] | Quantitative | DCE | Hospital | 152 (45 a) |

69.1 (7.7) | mHSPC | Patient perceptions of the risks and benefits of systemic treatments | Docetaxel or AA | C | Janssen | PREFS 4 |

| 2 | Eliasson 2017 [28] | Quantitative | DCE | Hospital | 285 | 70.7 (NR) | mCRPC | Patient perceptions of the risks and benefits of CTx | CTx | C | Janssen | PREFS 4 |

| 3 | Nakayama 2018 [29] | Quantitative | DCE | Hospital | 103 (37 a) |

NR | mCRPC | Investigating the concordance of treatment preferences between patients and physicians | All treatment options | C | Janssen | PREFS 4 |

| 4 | Uemura 2016 [30] | Quantitative | DCE | Hospital | 133 | 75.4 (7.4) | mCRPC | Patient preferences for treatments, subanalysis of symptomatic and asymptomatic patients | Docetaxel, Radium 223, AA | C | Bayer Yakuhin | PREFS 4 |

| 5 | Hauber 2014 [31] | Quantitative | DCE + TTO | Hospital | 401 | UK: 71.6 (NR) Sweden: 71.5 (NR) |

Mixed | Quantify how patients value hypothetical treatments that may delay bone metastasis vs specific bone-targeted treatment risks (eg, ONJ) | Bone-targeted agents | C | Amgen | PREFS 4 |

| 6 | Clark 1997 [32] | Quantitative + qualitative | MMS | Hospital | 201 | NR | Mixed | Identifying and measuring dimensions of QoL following initiation of treatment for advanced prostate cancer | Hormone therapy | A | VA Health Services Research | SRQR 15 |

| 7 | Ito 2018 [34] | Quantitative + qualitative | MMS | Community | 31 | NR | mHSPC | Exploring the perspectives of men and carers of men with mHSPC who had received docetaxel | Docetaxel | C | Janssen | SRQR 17 |

| 8 | Clark 2001 [33] | Quantitative + qualitative | MMS | Hospital | 201b | NR | Mixed | Understanding patients’ experiences of regret regarding their treatment choices and closely examining factors associated with regret | Bone-targeted agents | A | VA Health Services Research | SRQR 13 |

| 9 | Burbridge 2020 [35] | Qualitative | SSI | Hospital | 25 | 72.2 (7.01) | mCRPC | Exploring the symptomatic experience of diagnosis of mCRPC, and the emotional response to this diagnosis | Bone-targeted agent | C | Janssen | SRQR 22 |

| 10 | Catt 2019 [36] | Qualitative | SI | Hospital | 37 | 70.8 (6.81) | mCRPC | Exploring experiences of treatment decisions, information provision, perceived benefits and harms of treatment on patients and partners | Systemic therapy, radiotherapy | A | Brighton & Sussex Medical School | SRQR 19 |

| 11 | Dearden 2019 [37] | Qualitative | SSI | Community | 38 | NR | mCRPC | Understanding and quantifying the experience of living in patients receiving AA or enzalutamide in pre‐CTx and post‐CTx settings | AA or enzalutamide | C | Janssen | SRQR 14 |

| 12 | Grunfeld 2012 [38] | Qualitative | SSI | Hospital | 21 | 78 (NR) | Mixed | Interviews exploring the experience and impact of andropause symptoms | Hormone therapy | – | Not funded | SRQR 20 |

| 13 | Iacorossi 2019 [39] | Qualitative | SSI | Hospital | 13 | NR | mCRPC | Exploring adherence to oral hormone treatment in patients with mCRPC and the factors that may influence adherence | Hormone therapy | – | Not funded | SRQR 22 |

| 14 | Jones 2018 [40] | Qualitative | SSI | Hospital | 35 | NR | mCRPC | Examining the experiences of patients with advanced prostate cancer and their decision partners | CTx | A | NCI + Robert Wood Johnson Foundation | SRQR 22 |

| 15 | Doveson 2020 [41] | Qualitative | SSI | Hospital | 16 | NR | mCRPC | Exploring the perspectives of men when facing life-prolonging treatment for mCRPC | CTx, AA, enzalutamide, hormone therapy | A | Sophiahemmet Foundation + Kamprad Family Foundation | SRQR 20 |

NR = not reported; SD = standard deviation; A = academic; C = commercial; M – Mixed; TTO = time trade-off; DCE = discrete choice experiment; MMS = mixed-methods study; SSI = semi-structured interview; SI = structured interview; mHSPC = metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer; mCRPC = metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; ONJ = osteonecrosis of the jaw; CTx = chemotherapy; AA = abiraterone acetate; VA = Veterans Affairs; NCI = National Cancer Institute; SRQR = Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research; PREFS = Purpose, Respondents, Explanation, Findings, and Significance for preference and qualitative studies.

Metastatic subgroup cohort.

Treatments evaluated in the studies included chemotherapy (n = 3; 20.0%), abiraterone acetate (n = 4; 26.7%), enzalutamide (n = 2; 13.3%), radium-223 (n = 1; 6.7%), radiotherapy (n = 1; 6.7%), any systemic therapy (n = 1; 6.7%), any hormonal therapy (n = 4; 26.7%), and any bone-targeted agent (n = 3; 20.0%). In total, eight out of 15 studies (53.3%) were commercially funded (Table 1). Author groups from the UK accounted for the largest number of studies (37%; Supplementary Fig. 1).

3.2. Methodological quality and RoB

Methodological validity assessments for each study are listed in Supplementary Tables 1–4. Of the five quantitative studies, four (80%) reported a high response rate, one (20%) tested participant understanding, and all studies analysed the data correctly (Supplementary Table 2). For the quantitative studies, the mean PREFS quality score was 4 (SD 0). In terms of validity assessment, none of the studies justified their forced-choice study design; three studies (60%) did not report details of their experimental design. All studies piloted the data collection tool with the target population before implementing the main survey. Two (40%) met most of the analysis criteria. The mean SRQR quality score for the qualitative studies was 18.4 (SD 3.4; Supplementary Table 4). A single quantitative preference study was deemed to have high RoB (n = 1; 20%). Five qualitative studies were deemed to have high RoB (n = 5; 50%).

3.3. Results

3.3.1. Quantitative treatment preference studies

A summary of the demographics and study design of the quantitative preference studies (n = 5) is presented in Table 1 [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]. In all studies, participants were asked to choose between two treatment alternatives and were not given the option to report that they would not be treated. None of the studies justified this study design. The number of treatment attributes evaluated ranged from two to seven (mean 5, SD 2). Overall, treatment effectiveness, delay in time to symptoms, and fatigue emerged as the predominant treatment-related preferences that patients valued (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of major of findings for patient preferences and values in quantitative studies

| Patient preference category for values and preferences | Estimates of outcome importance (range across studies) | Participants | Studies | Certainty of evidence | Interpretation of findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment effectiveness (forced choice) | Two studies ranked treatment effectiveness as the most important attribute ○RAI 7.25 [27] ○RI 32% [29] One study used terminology for treatment impact on overall survival, reporting RI of 19.2% [30] |

388 | [27], [29], [30] | ⊕⊕○○ Low |

Patients consistently consider the effectiveness of a treatment above other treatment-related attributes |

| Delay in time to symptoms (forced choice/ proportions) | Four studies reported on time to appearance of symptoms: ○One study reported pain as the second most important attribute (RAI 6.26) [27] ○In one study there was a strong preference for treatment that fully controls bone pain (OR 12.069) [28] ○In one study, 80% of the patients would trade at least 3 mo of survival to avoid bone complications [31] |

838 | [27], [28], [31] | ⊕⊕○○ Low |

Patients consistently consider treatment impact on the time until they may develop symptoms of metastatic prostate cancer above other treatment-related attributes |

| Fatigue (forced choice) | Three studies reported fatigue as a major patient preference: ○Fatigue reported as the most important attribute (RI 24.9%) [30] ○OR 1.365 for treatments that lower the risk of fatigue [28] ○Fourth most important attribute (RAI 3.17) [27] |

570 | [27], [28], [30] | ⊕○○○ Very low |

The relationship between fatigue and treatment choice may be important |

RAI = relative attribute importance; RI = relative importance; OR = odds ratio.

3.3.1.1. mHSPC

de Freitas and colleagues [27] explored how 152 patients with mHSPC perceived the risks and benefits of hypothetical abiraterone acetate and docetaxel treatment in three European countries. The study included six treatment attributes: mode of administration, tiredness and fatigue, treatment effectiveness, bone pain, nausea and vomiting, and risk of infection. The authors reported that treatment effectiveness was the main objective for patients, and that patients wanted to avoid uncontrolled pain. In terms of relative attribute importance (RAI), the treatment attribute ranking was treatment effectiveness (RAI 7.25) followed by pain (RAI 6.26), risk of nausea (RAI 4.12), vomiting (RAI 3.17), risk of fatigue (RAI 2.24), and mode of administration (RAI 2.09) [27].

3.3.1.2. mCRPC

In the mCRPC setting, Eliasson and colleagues [28] explored hypothetical treatment options for 285 patients across the UK and Europe. The study included seven treatment attributes: effectiveness (delay in months before chemotherapy), steroid use, possible drug interactions (additional hospital visits for monitoring), cognitive impairment described as “fogginess” (effects on cognition and memory), fatigue, food restrictions, and bone pain. The findings were presented in terms of odds ratios (ORs) and the results suggest that patients prefer treatments that fully control bone pain (OR 12.06, 95% confidence interval [CI] 10.55–13.80) and those that delay chemotherapy (OR 1.72, 95% CI 1.54–1.92). In addition, patients seem to prefer treatments with a lower risk of “fogginess” (OR 2.11, 95% CI 1.84–2.42), a lower risk of fatigue (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.21–1.52), and fewer additional hospital visits (OR 1.24, 95% CI 1.11–1.39) [28].

The concordance of treatment preferences between patients and physicians in mCRPC was explored in a study of 103 patients in Japan [29]. The study included four attributes: quality of life, effectiveness, side effects, and accessibility. In terms of the relative importance (RI) of attributes, the preference ranking among patients was effectiveness (RI 32%) followed by accessibility of treatment (RI 26%), quality of life (RI 23%), and side effects (RI 19%).

With regard to bone-targeted and systemic agents in the mCRPC setting, Uemura et al [30] explored preferences associated with various treatments (radium-223, abiraterone acetate, and docetaxel) for 133 patients in Japan. The study included six attributes: OS length, time to a symptomatic skeletal event (SSE), administration method, reduction in the risk of bone pain, treatment-associated risk of fatigue, and lost workdays. Patients ranked their preferences as fatigue (RI 24.9%) followed by reduction in the risk of bone pain (RI 23.2%) and OS length (RI 19.2%). The authors compared preferences across symptomatic and asymptomatic patients and found that symptomatic patients placed significantly more importance on delaying an SSE. The authors concluded that patients with CRPC were more concerned about reduced quality of life from side effects of treatment than extension of survival.

Hauber et al [31] explored preferences for bone-targeted agents among 401 patients with mixed disease states in the UK and Sweden. The study used two TTO questions to assess patients’ trade-offs between avoiding metastasis-induced bone complications and longer survival. The results showed that patients were willing to trade up to 5 mo of survival to prevent bone complications.

3.3.2. Qualitative studies

A summary of the demographics and study design of the qualitative studies is presented in Table 1 [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41]. A complete list of all findings by study is available in Supplementary Table 7. Thematic analysis revealed the following key themes: cancer progression and/or survival; pain; fatigue; and other symptoms (sexual dysfunction, bothersome lower urinary tract symptoms [LUTS]; Table 3) [26].

Table 3.

Summary of major findings for patient preferences and values in qualitative studies

| Patient preference or value | Key themes defied | Participants | Studies | Confidence of evidence | Interpretation of key themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer progression or survival | Patients reported that they were willing to accept a range of side effects for potential benefits in cancer progression and/or survival | 148 | [35], [36], [37], [39], [40] | ⊕⊕○○ Low |

Patients with metastatic disease may be willing to trade side effects for potential oncological benefits |

| Fatigue | Fatigue emerged as a prominent treatment-related symptom, significantly impacting patients’ QoL | 315 | [32], [34], [35], [36], [38] | ⊕⊕○○ Low |

Fatigue has a large impact on QoL for this group of patients and risks for fatigue should be considered in relation to any treatment proposed |

| Pain | For patients with symptomatic metastatic prostate cancer, pain was consistently the most troublesome symptom | 62 | [35], [36] | ⊕○○○ Very low |

In symptomatic metastatic disease, avoidance or relief of pain appears to be paramount |

| Other symptoms: sexual dysfunction, bothersome LUTS | Erectile dysfunction and bothersome LUTS were both frequently reported by patients as negatively impacting their QoL and relationships | 263 | [32], [35], [38], [41] | ⊕○○○ Very low |

Local symptoms may have a significant negative impact on patient QoL. Treatments that alleviate local symptoms may lead to secondary benefits |

LUTS = lower urinary tract symptoms; QoL = quality of life.

Cancer progression and/or OS benefits related to treatment were a key theme extracted from five of the studies [35], [36], [37], [38], [39]. Dearden et al [37] undertook semistructured interviews with 38 patients with mCRPC who were receiving a novel antiandrogen therapy (abiraterone acetate or enzalutamide). Patients were satisfied with these therapies, specifically with reductions in prostate-specific antigen levels and the extended survival quality.

Burbridge et al [35] carried out semistructured interviews with 25 patients diagnosed with mCRPC. Of these patients, 83.3% said they would have taken a medication to delay (metastasis) progression if one had been available, irrespective of side effects. Ito et al [34] conducted semistructured interviews with 31 patients with mHSPC across Europe and the UK who were receiving docetaxel. They found that at the beginning of therapy, men were willing to take docetaxel to prolong their life, despite being fearful of the potential side effects and impact on their daily lives.

Fatigue was a key theme related to treatments identified in five of the studies [32], [34], [35], [36], [38]. Catt et al [36] undertook structured interviews with 37 patients with mCRPC, exploring experiences of treatment decisions, perceived benefits and harms of treatment, and the effects on patients’ lives. At 3 mo after starting a systemic therapy, 42% of patients said that fatigue was the worst treatment‐related side effect. Burbridge et al [35] also found that more than 75% of men with mCRPC reported fatigue or extreme tiredness (“Whatever [I do] is exhausting”). In the study by Ito et al [34], fatigue was a significant treatment-related side-effect reported by up to 60.9% of the patients interviewed.

Pain was identified as a theme in two studies [35], [36]. Burbridge et al [35] found that pain was one of the most frequent symptoms reported by more than 75% of patients (“I had a lot of pain”; “The pain comes and goes and I usually feel it somewhere in my back”). Catt et al [36] also found that pain was the worst symptom reported by most patients (46%), although nearly one-fifth (19%) made comments attributing the pain to causes other than prostate cancer (“I think the pain in my hip could be rheumatic”; “My pain in the lower back and shoulder are due to degeneration”).

Other symptoms related to treatments and local disease were sexual dysfunction and bothersome LUTS, reported in four studies [32], [35], [38], [41]. It is known from earlier work in the era before docetaxel that andropause symptoms (including sexual dysfunction) related to ADT administration were a significant consideration for patients in deciding on whether to commence treatment and a source of treatment regret [32], [33], [38]. Burbridge et al [35] found that bothersome LUTS were reported by more than 75% of men. Patients were willing to consider supportive treatment to alleviate these symptoms, probably caused by progression of an untreated local tumour.

Grunfeld et al [38] found that most patients reported hot flashes and night sweats, gynaecomastia, cognitive decline, and changes in sexual dysfunction (“That the erection is rather painful is somewhat of a disincentive to trying it too often”) as the most frequent adverse effects, affecting everyday functioning. Some patients felt that there was no need for treatment as they were older and single, whereas other reported a belief that the negative aspects outweighed the benefits.

3.4. Discussion

3.4.1. Principal findings

This systematic review addresses the evidence from both quantitative and qualitative studies reporting on patients’ values, preferences, and expectations in relation to their treatment for metastatic prostate cancer. In quantitative preference elicitation studies, patients consistently valued treatment effectiveness and delay in time to symptoms as the two most highly ranked treatment attributes (low to very low certainty; Table 2). Patients were willing to trade treatment-related toxicity for potential oncological benefits (low certainty). With rapidly emerging local tumour treatments and metastasis-directed therapies now available to patients, these findings are an important consideration for patients and their clinicians.

Qualitative thematic analysis revealed cancer progression or survival, pain, and fatigue as key to treatment decisions (low to very low certainty; Table 3). Patients continue to value oncological benefits in making decisions regarding treatments. However, in the subgroup of symptomatic patients, treatments that could alleviate pain were highly valued even at the expense of survival benefits (very low certainty).

Furthermore, treatment inducing fatigue had a significant negative impact on remaining quality of life (very low certainty). The fact that ionising radiation directed to metastases may secondarily exacerbate or induce fatigue highlights just one example of the difficult decision-making balance that patients and clinicians face [42].

3.4.2. Comparison with prior reviews and guidelines

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to evaluate patients’ preference and values for treatments following a diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer. Prior systematic reviews of patients’ preferences involved patients with localised prostate cancer, in which the marginal gains in absolute survival advantage (up to 5% over 10–15 yr) and side effects associated with radical prostate treatment remain the predominant issues [43], [44]. In the noncurative setting, it can be assumed that patients’ treatment preferences are entirely different.

The landmark STAMPEDE (arm H) study of 2061 men with newly diagnosed metastatic prostate cancer receiving additional local prostate radiotherapy compared to those receiving systemic therapy alone demonstrated a significant OS advantage for patients with low-volume disease in the radiotherapy arm (3-yr OS: 81% vs 73%; hazard ratio 0.68, 95% CI 0.52–0.90; p = 0.007) [11].

Against this background, international prostate cancer guidelines have incorporated radiotherapy into the standard of care [45], [46]. However, some guidelines recommend dose and fractionation schedules (eg, 36 Gy in 6 fraction) that specifically reduce hospital attendances on the basis that patients would value such an approach in the decision-making process [45]. However, there is no robust evidence detailing how patients balance the risks against the benefits of new treatments applied to this setting to support such a recommendation [18].

3.4.3. Strength and limitations

This is the first study to use an expert panel of urologists, oncologists, and health economists to develop a priori criteria for conducting a systematic review on this topic. This methodological rigour enabled us to summarise the key findings and rate the certainty of the evidence presented using the GRADE and GRADE CERQual criteria, respectively.

Unfortunately, the varied study designs and outcomes reported in the quantitative preference studies precluded a meta-analysis. Furthermore, the diverse qualitative studies reported are likely to reflect the heterogeneous pool of patients included in interviews (varied disease states, metastatic burden, asymptomatic vs symptomatic disease).

Finally, although bone-targeted agents were evaluated in this systematic review, the majority of studies focused on existing systemic therapies. No studies specifically reported on cytoreductive radical prostatectomy, minimally invasive ablative therapies, metastasectomy, or SABR. We are thus unable to report on patient preferences and values with regard to these treatments.

3.4.4. Unanswered questions and future research

This systematic review has predominantly highlighted patient preferences in the context of being offered established systemic therapy options and a limited number of bone-targeted agents. Therefore, our overall understanding of how novel surgical and radiotherapy treatment options are valued by patients remains limited.

However, results support a number of these treatment options continue to be published following robust trial evaluation [8], [16], [17]. We therefore propose that a reappraisal of patient preferences is now required to permit integration of new treatments into existing standard-of-care pathways. This could take the form of a prospective stand-alone study or indeed could be integrated into ongoing studies during longitudinal follow-up (eg, NCT01751438, NCT03456843, NCT02454543, NCT03988686, NCT02742675, ISRCTN15704862, NCT03655886, NCT03678025, and NCT03763253).

The IP5-MATTER study (NCT04590976) is a multicentre discrete-choice experiment, currently in its accrual phase, evaluating 300 patients with de novo synchronous mHSPC [47]. This trial is designed to evaluate novel treatments (cytoreductive radical prostatectomy, external beam radiotherapy, minimally invasive ablative therapy, and SABR) in addition to systemic therapy for the first time. The study is collecting data on patient characteristics (eg, age, comorbidities) and will offer an insight into whether these also have an impact on patient preferences [48].

It can be hypothesised that the results from studies can then be combined with the effect sizes from future reported interventional randomised trials to determine if, on average, patients are willing to accept the potential effect sizes that are reported in these studies [12], [14].

Finally, research on patients’ values, preferences, and expectations for treatment should be cognisant of an emerging theme of treatment regret that has been reported for localised disease [49]. One option for mitigating such levels of treatment regret is to assist in the informed decision-making process. It is possible that once novel treatment pathways are established for metastatic prostate cancer, the findings from patient preference elucidation studies (such as DCEs) may be integrated into further work towards the creation of decision treatment aids (DTAs). While residual uncertainty regarding the role of DCEs in the development of such DTAs remains, the methodology is currently being validated in localised prostate cancer and other studies on benign surgical strategies. If proven, this approach may offer utility in the development of any future DTAs for this specific cohort of patients [50], [51], [52].

4. Conclusions

There is currently limited understanding of patients’ preferences for treatment, and thus trade-off decisions, following a new diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer. For appropriate investment in emerging cytoreductive prostate and metastasis-directed treatment options that are most acceptable to patients, attempts to formalise our understanding of the trade-offs between oncological benefits and risks in this cohort should be performed.

Author contributions: Martin J. Connor had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the data integrity and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Connor, Genie, Burns.

Acquisition of data: Connor, Genie.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Connor, Genie.

Drafting of the manuscript: Connor, Genie.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Connor, Burns, Genie, Bass, Winkler, Khoo, Ahmed, Watson, Dudderidge, Sarwar, Gonzalez, Mangar, Falconer.

Statistical analysis: Connor, Genie.

Obtaining funding: None.

Administrative, technical, or material support: None.

Supervision: Ahmed, Winkler, Khoo, Watson.

Other: None.

Financial disclosures: Martin J. Connor certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: Martin J. Connor receives grant funding from the Wellcome Trust and University College London Hospitals Charity. Vincent Khoo is supported by personal fees and nonfinancial support from Accuray, Astellas, Bayer, Janssen, and Boston Scientific. Hashim U. Ahmed is supported by core funding from the UK National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Imperial Biomedical Research Centre and funding from the Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council (UK), Prostate Cancer UK, Cancer Research UK, The BMA Foundation, The Urology Foundation, The Imperial Health Charity, Sonacare, Trod Medical, and Sophiris Biocorp for trials and studies in prostate cancer; is a paid medical consultant for Sophiris Biocorp, Sonacare, and BTG/Galil; and is a paid proctor for high-intensity focused ultrasound, cryotherapy, and Rezūm water vapour therapy. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: None.

Associate Editor: Guillaume Ploussard

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euros.2021.10.003.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Connor M.J., Shah T.T., Horan G., Bevan C.L., Winkler M., Ahmed H.U. Cytoreductive treatment strategies for de novo metastatic prostate cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17:168–182. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0284-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyake H., Matsushita Y., Watanabe H., et al. Prognostic significance of time to castration resistance in patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Anticancer Res. 2019;39:1391–1396. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karantanos T., Corn P.G., Thompson T.C. Prostate cancer progression after androgen deprivation therapy: mechanisms of castrate resistance and novel therapeutic approaches. Oncogene. 2013;32:5501–5511. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sweeney C.J., Chen Y., Carducci M., et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:737–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis I.D., Martin A.J., Stockler M.R., et al. Enzalutamide with standard first-line therapy in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:121–131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James N.D., Sydes M.R., Clarke N.W., et al. Addition of docetaxel, zoledronic acid, or both to first-line long-term hormone therapy in prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): survival results from an adaptive, multiarm, multistage, platform randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1163–1177. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chi K.N., Agarwal N., Bjartell A., et al. Apalutamide for metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:13–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connor M.J., Smith A., Miah S., et al. Targeting oligometastasis with stereotactic ablative radiation therapy or surgery in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: a systematic review of prospective clinical trials. Eur Urol Oncol. 2020;3:582–593. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2020.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Bruycker A., Tran P.T., Achtman A.H., Ost P. Clinical perspectives from ongoing trials in oligometastatic or oligorecurrent prostate cancer: an analysis of clinical trials registries. World J Urol. 2021;39:317–326. doi: 10.1007/s00345-019-03063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weichselbaum R.R., Hellman S. Oligometastases revisited. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:378. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parker C.C., James N.D., Brawley C.D., et al. Radiotherapy to the primary tumour for newly diagnosed, metastatic prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;392:2353–2366. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32486-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oxford University. Testing radical prostatectomy in men with oligometastatic prostate cancer that has spread to the bone (TRoMbone). https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN15704862

- 13.M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Best systemic therapy or best systemic therapy (BST) plus definitive treatment (radiation or surgery). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01751438

- 14.Connor M.J., Shah T.T., Smigielska K., et al. Additional treatments to the local tumour for metastatic prostate cancer-assessment of novel treatment algorithms (IP2-ATLANTA): protocol for a multicentre, phase II randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye Y., Deng M., Zhao D., et al. Prostate cryoablation combined with androgen deprivation therapy for newly diagnosed metastatic prostate cancer: a propensity score-based study. Prostate Cancer Prostat Dis. 2021;24:837–844. doi: 10.1038/s41391-021-00335-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofman M.S., Emmett L., Sandhu S., et al. [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 versus cabazitaxel in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (TheraP): a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:797–804. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker C., Nilsson S., Heinrich D., et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:213–223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connor M.J., Khoo V., Watson V., Ahmed H.U. Radical treatment without cure: decision-making in oligometastatic prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2021;79:558–560. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2021.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M., et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burns D, Connor MJ, Genie MG, Watson V, Ahmed HU. CRD42020201420. A systematic review of patients’ preferences in the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer. PROSPERO; 2020. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020201420.

- 21.Joy S.M., Little E., Maruthur N.M., Purnell T.S., Bridges J.F. Patient preferences for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a scoping review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31:877–892. doi: 10.1007/s40273-013-0089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Brien B.C., Harris I.B., Beckman T.J., Reed D.A., Cook D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89:1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malde S., Umbach R., Wheeler J.R., et al. A systematic review of patients’ values, preferences, and expectations for the diagnosis and treatment of male lower urinary tract symptoms. Eur Urol. 2021;79:796–809. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y., Coello P.A., Guyatt G.H., et al. GRADE guidelines: 20. Assessing the certainty of evidence in the importance of outcomes or values and preferences—inconsistency, imprecision, and other domains. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;111:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewin S., Bohren M., Rashidian A., et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings—paper 2: how to make an overall CERQual assessment of confidence and create a summary of qualitative findings table. Implement Sci. 2018;13:11–23. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0689-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Freitas H.M., Ito T., Hadi M., et al. Patient preferences for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer treatments: a discrete choice experiment among men in three European countries. Adv Ther. 2019;36:318–332. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0861-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eliasson L., de Freitas H.M., Dearden L., Calimlim B., Lloyd A.J. Patients’ preferences for the treatment of metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer: a discrete choice experiment. Clin Ther. 2017;39:723–737. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakayama M., Kobayashi H., Okazaki M., Imanaka K., Yoshizawa K., Mahlich J. Patient preferences and urologist judgments on prostate cancer therapy in Japan. Am J Men’s Health. 2018;12:1094–1101. doi: 10.1177/1557988318776123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uemura H., Matsubara N., Kimura G., et al. Patient preferences for treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer in Japan: a discrete-choice experiment. BMC Urol. 2016;16:63. doi: 10.1186/s12894-016-0182-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hauber A.B., Arellano J., Qian Y., et al. Patient preferences for treatments to delay bone metastases. Prostate. 2014;74:1488–1497. doi: 10.1002/pros.22865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark J.A., Wray N., Brody B., Ashton C., Giesler B., Watkins H. Dimensions of quality of life expressed by men treated for metastatic prostate cancer. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:1299–1309. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark J.A., Wray N.P., Ashton C.M. Living with treatment decisions: regrets and quality of life among men treated for metastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:72–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ito T., Grant L., Duckham B.R., Ribbands A.J., Gater A. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of patient and carer experience of chemotherapy (docetaxel) in combination with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for the treatment of metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC) Adv Ther. 2018;35:2186–2200. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0825-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burbridge C., Randall J.A., Lawson J., et al. Understanding symptomatic experience, impact, and emotional response in recently diagnosed metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:3093–3101. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Catt S., Matthews L., May S., Payne H., Mason M., Jenkins V. Patients’ and partners’ views of care and treatment provided for metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer in the UK. Eur J Cancer Care. 2019;28 doi: 10.1111/ecc.13140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dearden L., Shalet N., Artenie C., et al. Fatigue, treatment satisfaction and health-related quality of life among patients receiving novel drugs suppressing androgen signalling for the treatment of metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2019;28 doi: 10.1111/ecc.12949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grunfeld E.A., Halliday A., Martin P., Drudge-Coates L. Andropause syndrome in men treated for metastatic prostate cancer: a qualitative study of the impact of symptoms. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35:63–69. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318211fa92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iacorossi L., Gambalunga F., De Domenico R., Serra V., Marzo C., Carlini P. Qualitative study of patients with metastatic prostate cancer to adherence of hormone therapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2019;38:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones R.A., Hollen P.J., Wenzel J., et al. Understanding advanced prostate cancer decision-making utilizing an interactive decision aid. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41:2. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doveson S., Holm M., Axelsson L., Fransson P., Wennman-Larsen A. Facing life-prolonging treatment: the perspectives of men with advanced metastatic prostate cancer–An interview study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;49 doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen H., Louie A.V., Boldt R.G., Rodrigues G.B., Palma D.A., Senan S. Quality of life after stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for early-stage lung cancer: a systematic review. Clin Lung Cancer. 2016;17:e141–e149. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Showalter T.N., Mishra M.V., Bridges J.F. Factors that influence patient preferences for prostate cancer management options: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:899. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S83333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bill-Axelson A., Holmberg L., Garmo H., et al. Radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting in prostate cancer—29-year follow-up. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2319–2329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1807801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.NHS England Clinical Commissioning . NHS England; London, UK: 2020. External beam radiotherapy for patients presenting with hormone sensitive, low volume metastatic prostate cancer at the time of diagnosis [P200802P] (URN: 1901) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mottet N., Cornford P., Van den Bergh R., et al. European Association of Urology; Arnhem, The Netherlands: 2020. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Connor MJ, Genie MG, Gonzalez M, et al. Metastatic prostate cancer men’s attitudes towards treatment of the local tumour and metastasis evaluative research (IP5-MATTER): protocol for a prospective, multicentre discrete choice experiment study. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e048996. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-048996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Connor M.J., Genie M.G., Gonzalez M., et al. P0869 - Metastatic prostate cancer patients’ attitudes towards treatment of the local tumour and metastasis evaluative research (IP5-MATTER): a multicentre, discrete choice experiment trial-in-progress. Eur Urol. 2021;79(Suppl 1):S1217–S1218. doi: 10.1016/S0302-2838(21)01243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lindsay J., Uribe S., Moschonas D., et al. Patient satisfaction and regret after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: a decision regret analysis. Urology. 2021;149:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dowsey M.M., Scott A., Nelson E.A., et al. Using discrete choice experiments as a decision aid in total knee arthroplasty: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1536-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.National Cancer Research Institute . NCRI Prostate Group annual report 2019–20. National Cancer Research Institute; London, UK: 2020. Putting men’s preferences at the center of the doctor-patient relationship: the Prostate Cancer Treatment Preferences (PARTNER) test. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Genie M.G., Nicoló A., Pasini G. The role of heterogeneity of patients’ preferences in kidney transplantation. J Health Econ. 2020;72:102331. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2020.102331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.