Key Points

Question

How often and for how long do children and their caregivers miss school or work after critical care hospitalization for acute respiratory failure?

Findings

In this secondary analysis of the Randomized Evaluation of Sedation Titration for Respiratory Failure clinical trial, more than two-thirds of children missed school after discharge for a median of 9.1 days. Among primary caregivers, more than half missed work after their child’s hospitalization for a median of 2 days.

Meaning

These findings suggest that children and their caregivers often miss school or work after critical care hospitalization for acute respiratory failure; these children may be at increased risk of lower educational achievement, economic hardship, and poor health outcomes in adulthood.

This secondary analysis of a cluster randomized trial measures the rate and duration of school and work absence among children who survived hospitalization for acute respiratory failure and their caregivers, respectively.

Abstract

Importance

Patients who survive pediatric critical illness and their caregivers commonly experience physical, emotional, and cognitive sequelae. However, the rate and duration of school absence among patients and work absence among their caregivers are unknown.

Objective

To determine the rates and duration of school absence among children who survived hospitalization with acute respiratory failure and work absence among their caregivers.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The Randomized Evaluation of Sedation Titration for Respiratory Failure (RESTORE) cluster randomized trial included 2449 children from 31 sites to protocolized sedation (intervention) vs usual care (control) from June 6, 2009, to December 2, 2013. In total, 1360 children survived hospitalization and were selected for follow-up at 6 months after pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) discharge, which was completed from January 12, 2010, to April 13, 2015. This secondary analysis was conducted from July 1, 2020, to September 30, 2021.

Exposures

PICU hospitalization for acute respiratory failure, including invasive mechanical ventilation.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Postdischarge assessments with caregivers of eligible participants at 6 months after PICU discharge, including questions about school and work absence. Risk factors associated with longer absence from school and work were identified.

Results

Postdischarge assessments were completed for 960 children who survived treatment for acute respiratory failure, of whom 443 (46.1%) were girls and 517 (53.9%) were boys; 509 of 957 (53.2%) were non-Hispanic White. Median age was 1.8 years (IQR, 0.4-7.9 years). In total, 399 children (41.6%) were enrolled in school, of whom 279 (69.9%) missed school after discharge. Median duration of postdischarge absence was 9.1 days (IQR, 0-27.9 days) among all children enrolled in school and 16.9 days (IQR, 7.9-43.9 days) among the 279 children with postdischarge absence. Among 960 primary caregivers, 506 (52.7%) were employed outside the home, of whom 277 (54.7%) missed work. Median duration of postdischarge work absence was 2 days (IQR, 0-10 days) among all employed primary caregivers, and 8 days (IQR, 4-20 days) among the 277 caregivers who missed work after discharge. The odds of postdischarge school absence and greater duration of absence increased for children 5 years or older (compared with 0-4 years, odds ratios [ORs] for 5-8 years, 3.20 [95% CI, 1.69-6.05] and 2.09 [95% CI, 1.30-3.37], respectively; ORs for 9-12 years, 2.49 [95% CI, 1.17-5.27] and 2.32 [95% CI, 1.30-4.14], respectively; and ORs for 13-18 years, 2.37 [95% CI, 1.20-4.66] and 1.89 [95% CI, 1.11-3.24], respectively) and those with a preexisting comorbidity (ORs, 1.90 [95% CI, 1.10-3.29] and 1.76 [95% CI, 1.14-2.69], respectively).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this secondary analysis of a cluster randomized trial, 2 in 3 children hospitalized for acute respiratory failure missed school after discharge, for a median duration of nearly 2 weeks. In addition, more than half of primary caregivers missed work after discharge. The magnitude of school absenteeism suggests that children may be at increased risk for lower educational achievement, economic hardship, and poor health outcomes in adulthood.

Introduction

Survivors of critical illness and their families commonly experience physical, emotional, and cognitive problems after hospitalization. These sequelae—termed postintensive care syndrome, or PICS1—have been increasingly recognized in survivors of pediatric critical illness.2,3 Because child and family health are closely entwined, deterioration in a child’s health has spillover effects onto the family, further impeding the child’s recovery and worsening their long-term health.2,4 Owing to the reciprocal relationship between child and family health, it is important to examine outcomes after critical illness not only among children, but also in their caregivers and siblings.3,4

Children and their families may also experience financial effects after critical illness, including inability of caregivers to return to work.5,6 Indeed, a recent meta-analysis found only 1 in 3 adults who survived critical illness was able to return to work within 3 months of discharge, and inability to return to work was associated with worse psychological outcomes.7 Similarly, children and their caregivers may have prolonged absence from school and work. However, the rate and duration of school and work absence after pediatric critical illness are unknown.

Thus, among participants in the Randomized Evaluation of Sedation Titration for Respiratory Failure (RESTORE) trial,8,9 we measured the rate and duration of school and work absence among children who survived pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) hospitalization for acute respiratory failure and their caregivers, respectively. In addition, we identified patient, family, and hospitalization characteristics associated with prolonged school or work absence.

Methods

Patients

RESTORE, a 31-center cluster randomized trial,8 enrolled 2459 patients aged 2 weeks to 17 years from June 6, 2009, to December 2, 2013; consent was withdrawn for 10, leaving 2449 patients. Inclusion criteria included invasive mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Each site obtained institutional review board approval and written informed consent from the legal guardians of patient participants. Parents and guardians provided consent during acute hospitalization for follow-up at 6 months after PICU discharge. Telephone follow-up assessments were conducted on a sample of participants stratified by age and site. In total, 1360 patients survived hospitalization and were selected for follow-up.10,11 Thirty patients died before follow-up, leaving 1330 patients eligible for follow-up at 6 months, completed from January 12, 2010, to April 13, 2015. This secondary analysis was conducted from July 1, 2020, to September 30, 2021. Our study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

Primary Outcomes

During the 6-month postdischarge survey, caregivers were asked about school enrollment, school absence, employment, and work absences among children, siblings, and primary and secondary caregivers (Table 1 and eMethods 1 in Supplement 1). The primary outcomes of this study were school and work absences in the 6 months after discharge among patients who survived pediatric respiratory failure and their primary caregivers. Specifically, we measured (1) the rate and duration of absence from school, preschool, or day care (herein referred to as school) during the 6 months after discharge among patients who were enrolled in school before the hospitalization and (2) the rate and duration of work absence during the 6 months after discharge among primary caregivers who reported full-time or part-time employment outside of the home.

Table 1. Rate and Duration of School and Work Absences.

| Participant | Rate and durationa |

|---|---|

| Child | |

| Postdischarge school days | |

| Any missed days, No./total No. (%) | 279/399 (69.9) |

| No. of missed days, median (IQR) | 9.1 (0-27.9) |

| Primary caregiver | |

| Postdischarge work days | |

| Any missed days, No./total No. (%) | 277/506 (54.7) |

| No. of missed days, median (IQR) | 2 (0-10) |

| During hospitalization work days | |

| Any missed days, No./total No. (%) | 426/506 (84.2) |

| No. of missed days, median (IQR) | 10 (4-20) |

| Secondary caregiver | |

| Postdischarge work days | |

| Any missed days, No./total No. (%) | 193/614 (31.4) |

| No. of missed days, median (IQR) | 0 (0-2) |

| During hospitalization work days | |

| Any missed days, No./total No. (%) | 484/614 (78.8) |

| No. of missed days, median (IQR) | 5.5 (2-10) |

Rate and duration of school or work missed were determined through the following survey questions: (1) Has your child missed any days of day care, preschool, or school since being admitted to the hospital roughly 6 months ago? (2) How many days of day care, preschool, or school has your child missed? (3) Since your child was discharged from the hospital, how many days have you had to stay home from work to be with him or her when you have been planning to work? and (4) Since your child was discharged from the hospital, how many days has another person who had been planning to work had to stay home from work to be with him or her?

We hypothesized that the rate and duration of school absence would be associated with the duration of hospitalization, so we focused our primary outcomes on absenteeism after discharge. Because the follow-up survey asked about total duration of school absence (inclusive of school missed during hospitalization), we calculated the rate and duration of postdischarge school absence among patients discharged during the school year (which we defined as September through June) by subtracting the estimated number of weekdays missed during hospitalization (5 weekdays per 7 days of hospitalization, described further in eMethods 2 in Supplement 1) from the total number of school days reported as missed.

Secondary Outcomes

Secondary outcomes included the rate of chronic absenteeism after discharge (defined as missing >15 days of school)12,13 among patients who survived pediatric respiratory failure; the rate and duration of any school absence (either during hospitalization or after discharge); the rate and duration of work absence during hospitalization among primary caregivers; the rate and duration of work absence among secondary caregivers during hospitalization and after discharge; and the rate and duration of school absence among siblings during hospitalization and after discharge. As with the primary outcomes, the secondary outcomes were measured among at-risk individuals (ie, children enrolled in school and caregivers employed before hospitalization).

Subgroup Analyses

We completed several subgroup analyses to better characterize the burden of school absence. First, to evaluate the association of acute respiratory failure with elementary, middle, and high school absence vs day care or preschool absence, we measured the rate and duration of postdischarge school absence among children 5 years or older and among children 4 years or younger. In addition, to estimate the association with part-time day care or preschool enrollment, we measured the rate and duration of postdischarge school absence assuming a planned attendance of 2 days per week for children 4 years or younger. To differentiate the association of acute hospitalization from baseline health, we measured the rate and duration of school absence among children by preexisting comorbidity status. Finally, to understand how a child’s age is associated with work absence, we evaluated rate and duration of postdischarge primary caregiver work absence by child age group (0-4, 5-9, 10-12, and 13-18 years).

Statistical Analysis

To identify risk factors associated with school and work absenteeism, we completed several analyses. First, we evaluated whether the following characteristics differed across 4 groups defined by duration of absenteeism (no missed school/work and tertiles of missed school/work): patient characteristics (age, sex, race and ethnicity, preadmission functional status [Pediatric Overall Performance Category],14 and comorbidities); family characteristics (primary caregiver educational level and daily activity, secondary caregiver daily activity, median household income of zip code of residence); hospitalization characteristics (severity of illness [measured by Pediatric Risk of Mortality III],15 primary diagnosis, and PICU and hospital lengths of stay); and posthospitalization characteristics (hospital readmission, emergency department use after discharge). We evaluated trends in characteristics across these 4 groups using the χ2 test for trend or the nonparametric test for trend (Jonckheere-Terpstra test).16

Second, we fit a multivariable ordinal logistic (proportional odds) regression model for cumulative categories of duration of school absence (eg, longer or medium absence vs short or no absence), which included the following characteristics as risk factors associated with outcomes: age group (0-4, 5-9, 10-12, and 13-18 years), race and ethnicity, baseline functional impairment, prior comorbidity, admission diagnosis, and primary caregiver’s daily activity (full-time employment, part-time employment, homemaker, and other [ie, student, retired, or disabled]). In addition, we fit logistic regression models (yes or no absence) using the above risk factors.

We fit additional multivariable models including a dichotomous variable for the presence of a secondary caregiver and a count variable for the number of siblings to understand their impact on postdischarge school absence. Finally, to understand the association of the RESTORE intervention (protocolized sedation) with outcomes, we compared rates and duration of absence between the intervention and usual care arms by χ2 and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Because RESTORE was a cluster randomized trial, we also explored multilevel models (patients nested within sites) in preliminary analyses but found no appreciable site effect, so we present results without adjustment for site for simplicity.

The caregivers of 7 children did not recall whether they missed school, and a caregiver of 1 child did not respond to this question. For these children, we assumed no school was missed. In addition, caregivers of 10 children reported missed school but did not quantify the numbers of days missed. These children were excluded from analyses of postdischarge school absence. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata software, version 15 (StataCorp LLC). Two-sided P < .05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

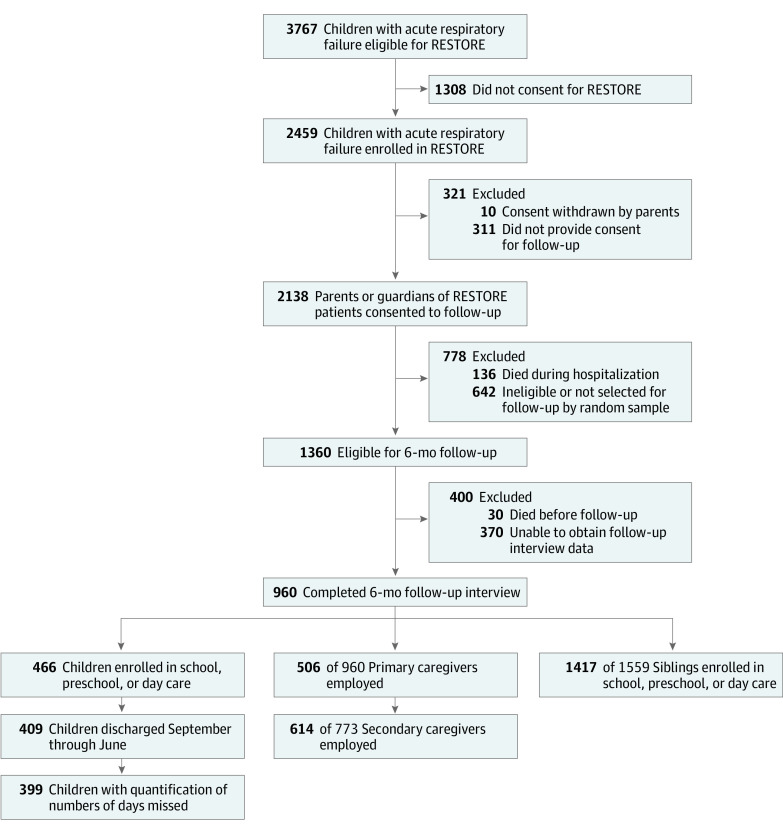

Of 1330 patients enrolled in RESTORE and eligible and selected for 6-month postdischarge follow-up, 370 (27.8%) did not complete follow-up interviews (including 263 [19.8%] lost to follow-up) and 960 (72.2%) had a follow-up interview completed by a parent or guardian at a median of 6.9 months (IQR, 5.7-8.5 months) after discharge (Figure 1) and were included in this study. Demographic information was previously reported.10 Briefly, the cohort included 443 girls (46.1%) and 517 boys (53.9%). Race and ethnicity data were obtained from the medical record when available; if not available, research staff were instructed to ask families directly. In total, 33 of 957 patients (3.4%) with available data were Asian; 167 (17.5%), Black; 208 (21.7%), Hispanic/Latinx; 509 (53.2%), non-Hispanic White; and 40 (4.2%), other (American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and multiracial or >1 race and ethnicity).12,17,18 Median age was 1.8 years (IQR, 0.4-7.9 years).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Study Participants.

RESTORE indicates Randomized Evaluation of Sedation Titration for Respiratory Failure.

Child School Absence

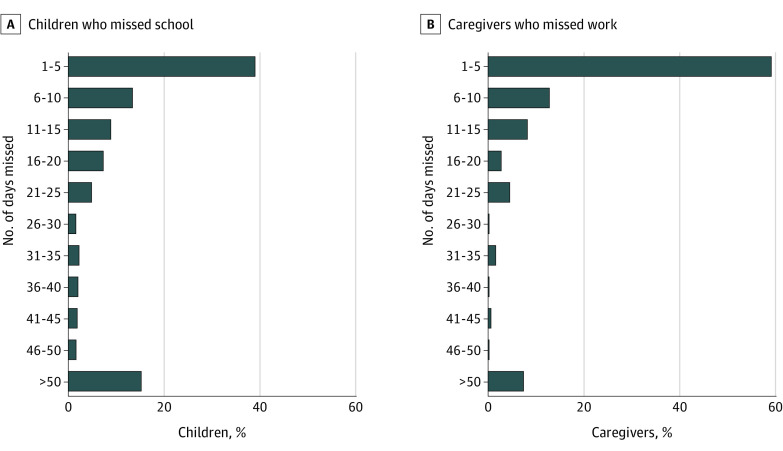

In total, 399 children (41.6%) were enrolled in school (defined as day care, preschool, or school) before hospitalization and discharged between September and June, of whom 279 (69.9%) missed school after discharge. Median duration of postdischarge school absence was 9.1 days (IQR, 0-27.9 days) among all children enrolled in school and 16.9 days (IQR, 7.9-43.9 days) among the 279 with any postdischarge absence (Table 1 and Figure 2). In total, 153 of 399 children (38.3%) met criteria for chronic absenteeism after discharge, missing more than 15 days of school. Among the 279 children with any postdischarge absence, 153 (54.8%) met criteria for chronic absenteeism.

Figure 2. School and Work Days Absent in the 6 Months After Child’s Hospital Discharge.

Includes 399 children with quantification of days missed and 506 primary caregivers employed outside the home.

Patient characteristics including older age, preexisting functional impairment, and preexisting comorbidity were more common among children with longer duration of postdischarge school absence (Table 2). Children with a longer median PICU length of stay had a significantly longer duration of postdischarge school absence (9.7 days [IQR, 6.0-16.5 days] for no absence vs 12.7 days [IQR, 6.8-19.3 days] for long absence; P = .04 for trend).

Table 2. Patient, Family, and Hospitalization Characteristics Across Duration of Postdischarge School Absence Category (N = 399).

| Characteristic | School absence categorya | P valueb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No absence | Short absence (n = 94) | Medium absence (n = 92) | Long absence (n = 93) | ||

| Duration of school absence, median (IQR) [range], d | 0 (0-0) [0-0] | 5.7 (2.9-7.9) [0.3-10.0] | 17.0 (13.6-22.1) [10.7-30.7] | 64.3 (43.8-96.3) [31.7-219.8] | <.001 |

| Patient characteristics | |||||

| Age at PICU admission, median (IQR), y | 3.4 (0.6-10.1) | 6.7 (4.4-10.9) | 6.5 (3.4-12.3) | 9.0 (5.8-12.5) | <.001 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 52 (43.3) | 37 (39.4) | 43 (46.7) | 42 (45.2) | .59 |

| Male | 68 (56.7) | 57 (60.6) | 49 (53.3) | 51 (54.8) | |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||

| Asian | 7 (5.8) | 4 (4.3) | 1 (1.1) | 0 | .93 |

| Black | 22 (18.3) | 18 (19.1) | 21 (22.8) | 17 (18.5) | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 16 (13.3) | 12 (12.8) | 11 (12.0) | 13 (14.1) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 67 (55.8) | 55 (58.5) | 59 (64.1) | 61 (66.3) | |

| Otherc | 8 (6.7) | 5 (5.3) | 0 | 1 (1.1) | |

| Missing, No. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Functional impairment (POPC >1) at baselined | 28 (23.3) | 21 (22.3) | 33 (35.9) | 42 (45.2) | <.001 |

| Preexisting comorbidity | |||||

| Asthma | 13 (10.8) | 34 (36.2) | 21 (22.8) | 11 (11.8) | .89 |

| Cancer | 6 (5.0) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | 19 (20.4) | <.001 |

| Chromosomal abnormality | 4 (3.3) | 3 (3.2) | 6 (6.5) | 10 (10.7) | .02 |

| Prematurity | 12 (10.0) | 8 (8.5) | 9 (9.8) | 10 (10.7) | .82 |

| Neurological/neuromuscular disorder | 10 (8.3) | 7 (7.4) | 6 (6.5) | 18 (19.3) | .02 |

| Seizure disorder | 7 (5.8) | 11 (11.7) | 14 (15.2) | 17 (18.3) | .004 |

| No known comorbidity | 73 (60.8) | 51 (54.3) | 43 (46.7) | 56 (60.2) | .009 |

| Family characteristics | |||||

| Primary caregiver educational level | |||||

| Some high school | 5 (5.5) | 8 (11.3) | 9 (13.6) | 3 (4.8) | .77 |

| High school graduate | 18 (19.8) | 17 (23.9) | 18 (27.3) | 14 (22.6) | |

| Some college or technical school | 35 (38.5) | 15 (21.1) | 12 (18.2) | 22 (35.5) | |

| College graduate/postgraduate | 33 (36.3) | 31 (43.7) | 27 (40.9) | 23 (37.1) | |

| Missing, No. | 29 | 23 | 26 | 31 | |

| Primary caregiver main daily activities | |||||

| Working | .47 | ||||

| Full-time | 48 (40.3) | 52 (55.9) | 48 (53.3) | 43 (46.7) | |

| Part-time | 16 (13.4) | 17 (18.3) | 18 (20.0) | 14 (15.2) | |

| Keeping house/raising children | 42 (35.3) | 17 (18.3) | 17 (18.9) | 27 (29.3) | |

| Other (ie, student, retired, disabled) | 13 (10.9) | 7 (7.5) | 7 (7.8) | 8 (8.7) | |

| Missing, No. | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| Secondary caregiver main daily activities | |||||

| Working | .13 | ||||

| Full-time | 74 (77.9) | 52 (72.2) | 58 (89.2) | 61 (82.4) | |

| Part-time | 7 (7.4) | 8 (11.1) | 2 (3.1) | 4 (5.4) | |

| Keeping house/raising children | 4 (4.2) | 5 (6.9) | 5 (7.7) | 3 (4.1) | |

| Other (ie, student, retired, disabled) | 10 (10.5) | 7 (9.7) | 0 | 6 (8.1) | |

| Missing, No. | 25 | 22 | 27 | 19 | |

| Household income of zip code of residence, median (IQR), $ | 55 521 (43 215-73 490) | 62 691 (45 813-82 069) | 56 315 (45 603-75 406) | 63 571 (47 485-83 564) | .14 |

| Income category of zip code of residence | |||||

| <$40 000 | 24 (20.0) | 16 (17.0) | 12 (13.0) | 11 (11.8) | .13 |

| $40 000-$79 999 | 70 (58.3) | 51 (54.3) | 59 (64.1) | 56 (60.2) | |

| ≥$80 000 | 26 (21.7) | 27 (28.7) | 21 (22.8) | 26 (28.0) | |

| Duration of missed work of primary caregiver, median (IQR), d | |||||

| During hospitalization | 8 (2-14) | 8 (5-15) | 15 (8-20) | 20 (10-30) | <.001 |

| After hospitalization | 0 (0-5) | 2 (0-5) | 5 (0-10) | 10 (0-39) | <.001 |

| Hospitalization characteristics | |||||

| PRISM III-12 score, median (IQR)e | 7.5 (5-11) | 8 (4-13) | 7 (3-14) | 10 (5-16) | .10 |

| Primary diagnosis category | |||||

| Bronchiolitis or asthma | 38 (31.7) | 32 (34.0) | 22 (23.9) | 6 (6.4) | <.001 |

| Pneumonia or aspiration pneumonia | 60 (50.0) | 46 (48.9) | 47 (51.1) | 52 (55.9) | |

| Acute respiratory failure related to sepsis | 13 (10.8) | 11 (11.7) | 12 (13.0) | 22 (23.7) | |

| Otherf | 9 (7.5) | 5 (5.3) | 11 (11.9) | 13 (14.0) | |

| Randomized to RESTORE sedation protocol | 58 (48.3) | 49 (52.1) | 41 (44.6) | 46 (49.5) | .87 |

| PICU length of stay, median (IQR), d | 9.7 (6.0-16.5) | 7.3 (4.6-10.9) | 10.4 (7.0-14.4) | 12.7 (6.8-19.3) | .04 |

| Functional impairment (POPC >1) at discharged | 39 (32.5) | 26 (27.7) | 48 (52.2) | 54 (58.1) | <.001 |

| Posthospitalization outcomes in 6 mo after discharge | |||||

| Emergency department use | 44 (36.7) | 24 (25.5) | 30 (32.6) | 42 (45.2) | .20 |

| Hospital readmission | 31 (25.8) | 13 (13.8) | 27 (29.3) | 41 (44.1) | .002 |

Abbreviations: PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; POPC, Pediatric Overall Performance Category; PRISM III-12, Pediatric Risk of Mortality III score from first 12 hours in the PICU; RESTORE, Randomized Evaluation of Sedation Titration for Respiratory Failure.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as number (%) of patients. Percentages have been rounded and may not total 100.

Calculated for comparisons across categories using the χ2 test for trend or the nonparametric test for trend (Jonckheere-Terpstra test) for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

Other includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and multiracial or more than 1 race and ethnicity.

Disability was determined using the POPC. A score of 1 indicates a good functional status, whereas a score of 2 or greater represents at least mild disability.

Uses physiologic and laboratory variables from the first 12 hours of PICU admission to calculate the overall risk of mortality. Scores range from 0 to 74, with higher scores representing a higher risk of mortality.

Includes pulmonary edema or hemorrhage, pulmonary hypertension, laryngotracheobronchitis, thoracic trauma, pneumothorax, acute chest syndrome, pertussis, exacerbation of lung disease (cystic fibrosis or bronchopulmonary dysplasia), acute respiratory failure related to blood transfusions, acute respiratory failure after bone marrow transplantation, and other.

In multivariable models, the odds of postdischarge school absence and greater duration of absence increased for children 5 years or older (compared to 0-4 years, odds ratios [ORs] for 5-8 years, 3.20 [95% CI, 1.69-6.05] and 2.09 [95% CI, 1.30-3.37], respectively; ORs for 9-12 years, 2.49 [95% CI, 1.17-5.27] and 2.32 [95% CI, 1.30-4.14], respectively; and ORs for 13-18 years, 2.37 [95% CI, 1.20-4.66] and 1.89 [95% CI, 1.11-3.24], respectively) and those with a preexisting comorbidity (ORs, 1.90 [95% CI, 1.10-3.29] and 1.76 [95% CI, 1.14-2.69], respectively) (Table 3). In the ordinal logistic regression model, baseline functional impairment was also associated with increased odds of longer durations of school absence (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.05-2.60) (Table 3). Respiratory failure due to bronchiolitis or asthma was associated with lower odds of longer durations of school absence compared to respiratory failure due to pneumonia (OR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.34-0.87) (Table 3). The presence of a secondary caregiver and number of siblings were not associated with rate of postdischarge school absence (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). The rates of postdischarge school absence (136 of 194 [70.1%] vs 143 of 205 [69.7%]; P = .94) and duration of postdischarge school absence (median, 8.9 days [IQR, 0-26.4 days] vs 9.3 days [IQR, 0-27.9 days]; P = .87) were similar among children randomized to protocolized sedation vs usual care (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

Table 3. Multivariable Models of Risk Factors Associated With Rate and Duration of School Absence After Hospital Discharge.

| Variable | OR (95% CI)a | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Risk factors associated with rate of school absence (n = 392)b | ||

| Age group, y | ||

| 0-4 | 1 [Reference] | .001 |

| 5-8 | 3.20 (1.69-6.05) | |

| 9-12 | 2.49 (1.17-5.27) | |

| 13-18 | 2.37 (1.20-4.66) | |

| Minority race or ethnicity | 0.92 (0.56-1.51) | .74 |

| Functional impairment (POPC >1) at baselinec | 1.53 (0.83-2.80) | .17 |

| Preexisting comorbidity | 1.90 (1.10-3.29) | .02 |

| Primary diagnosis category | ||

| Pneumonia | 1 [Reference] | .34 |

| Bronchiolitis or asthma | 0.80 (0.45-1.42) | |

| Acute respiratory failure related to sepsis | 1.28 (0.61-2.71) | |

| Other | 1.91 (0.77-4.74) | |

| Primary caregiver main daily activities | ||

| Working full-time | 1 [Reference] | .001 |

| Keeping house/raising children | 0.30 (0.17-0.55) | |

| Working part-time | 0.79 (0.39-1.58) | |

| Other (student, retired, disabled) | 0.47 (0.20-1.09) | |

| Risk factors associated with category of duration of school absence (n = 392)d | ||

| Age group, y | ||

| 0-4 | 1 [Reference] | .005d |

| 5-8 | 2.09 (1.30-3.37) | |

| 9-12 | 2.32 (1.30-4.14) | |

| 13-18 | 1.89 (1.11-3.24) | |

| Minority race or ethnicity | 0.80 (0.54-1.18) | .26 |

| Functional impairment (POPC >1) at baselinec | 1.65 (1.05-2.60) | .03 |

| Preexisting comorbidity | 1.76 (1.14-2.69) | .01 |

| Primary diagnosis category | ||

| Pneumonia | 1 [Reference] | <.001 |

| Bronchiolitis or asthma | 0.54 (0.34-0.87) | |

| Acute respiratory failure related to sepsis | 1.58 (0.89-2.78) | |

| Other | 2.29 (1.14-4.63) | |

| Primary caregiver main daily activities | ||

| Working full-time | 1 [Reference] | .12 |

| Keeping house/raising children | 0.57 (0.35-0.91) | |

| Working part-time | 0.89 (0.53-1.47) | |

| Other (student, retired, disabled) | 0.68 (0.33-1.37) | |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; POPC, Pediatric Overall Performance Category.

The largest group within each variable was chosen as the reference category.

An OR of greater than 1.0 indicates higher odds of missed school during hospital admission to 6 months after discharge. Odds ratios were calculated using logistic regression.

Disability was determined using the POPC. A score of 1 indicates a good functional status, while a score of 2 or greater represents at least mild disability.

An OR of greater than 1.0 indicates higher odds of missed school during hospital admission to 6 months after discharge. The OR describes the change in odds of increasing categories of duration of school absence, calculated using ordinal logistic (proportional odds) regression.

Of the 466 children enrolled in school (regardless of month of discharge), 384 (82.4%) missed school during hospitalization and/or after discharge, for a median of 20 days (IQR, 4-45 days). Among children who missed school, the median time missed during hospitalization and/or after discharge was 25 days (IQR, 12-60 days). Older age (median, 9.1 years [IQR, 5.9-12.5 years]), functional impairment (55 of 118 children [46.6%]), and preexisting comorbidity (eg, neurological/neuromuscular disorder, 22 of 118 children [18.6%]) were more common among children with longer duration of during-hospitalization and/or postdischarge school absence (eTable 3 in Supplement 1).

Primary Caregiver Work Absence

Of 960 primary caregivers, 506 (52.7%) were employed before the hospitalization, of whom 277 (54.7%) missed work after discharge. Median duration of postdischarge work absence was 2 days (IQR, 0-10 days) among all employed primary caregivers and 8 days (IQR, 4-20 days) among the 277 who missed work after discharge.

A child’s preexisting comorbidity (eg, cancer, 13 of 84 [15.5%]), functional disability at hospital admission (32 of 84 [38.1%]) and discharge (48 of 84 [57.1%]), and longer PICU length of stay (median, 12.3 days [IQR, 7.3-19.1 days]) were more common among primary caregivers with longer duration of postdischarge work absence (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). Duration of postdischarge work absence among primary caregivers was associated with duration of postdischarge school absence. Among children with no school absence after discharge, their primary caregivers missed work for a median of 0 days (IQR, 0-5 days) after discharge, compared with a median of 10 days (IQR, 0-39 days) for primary caregivers of children who missed the most days of school (P < .001 for trend) (Table 2).

Rate of primary caregiver postdischarge work absence (142 of 269 [52.8%] vs 135 of 237 [57.0%]; P = .35) and duration of postdischarge work absence (median, 2 days [IQR, 0-10 days] vs 2 days [IQR, 0-10 days]; P = .61) were similar between caregivers of children in the sedation protocol vs usual care group (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). In total, 426 primary caregivers (84.2%) missed work during their child’s hospitalization. Median duration of during-hospital work absence was 10 days (IQR, 4-20 days) among all previously employed primary caregivers, and 10 days (IQR, 6-20 days) among the 426 with any during-hospital absence.

Secondary Caregiver Work Absence

Among 773 secondary caregivers, 614 (79.4%) were employed before the hospitalization, of whom 193 (31.4%) missed work after discharge. Median duration of postdischarge work absence was 2 days (IQR, 0-2 days) among all employed secondary caregivers and 4 days (IQR, 2-8 days) among the 193 who missed work after discharge. Child functional impairment at admission (28 of 58 [48.3%]) and discharge (29 of 58 [50.0%]) were more common among secondary caregivers with longer duration of postdischarge work absence (eTable 5 in Supplement 1).

In total, 484 secondary caregivers (78.8%) missed work during hospitalization. Median duration of during-hospital work absence was 6 days (IQR, 2-10 days) among all employed secondary caregivers and 8 days (IQR, 5-14 days) among the 484 who missed work during hospitalization.

Sibling School Absence

Of 960 children with acute respiratory failure, 790 (82.3%) had a total of 1559 siblings, of whom 1417 (90.9%) were enrolled in school. Only 66 (4.7%) of the school-enrolled siblings missed school after discharge. The median duration of school absence after discharge was 0 days (IQR, 0-0 days) and 2 days (IQR, 4-10 days) for those with postdischarge school absence. In total, 282 siblings (19.9%) missed school during hospitalization. The median duration of school absence during hospitalization was 0 days (IQR, 0-0 days) among all siblings enrolled in school and 3 days (IQR, 2-6 days) for children with during-hospital school absence.

Subgroup Analyses

Of the 399 children enrolled in school, 247 (61.9%) were 5 years or older, of whom 196 (79.4%) missed school after discharge. Median duration of postdischarge school absence was 13.3 days (IQR, 1.6-42.1 days) among all children 5 years or older enrolled in school and 19.6 days (IQR, 8.6-55.0 days) among the 196 with any postdischarge absence (eTable 6 in Supplement 1). In total, 152 children enrolled in school were 4 years or younger, of whom 83 (54.6%) missed school after hospital discharge. Median duration of postdischarge school absence was 3.6 days (IQR, 0-14.6 days) among all children 4 years or younger enrolled in school and 12.9 days (IQR, 7.1-22.9 days) among the 152 with any postdischarge absence (eTable 6 in Supplement 1). In our analysis examining a 2-day school week for children 4 years and younger, 98 (64.5%) missed school. Median duration of postdischarge school absence was 9.3 days (IQR, 0-21.9 days) among all children 4 years or younger enrolled in school and 17.0 days (IQR, 9.3-27.6 days) among the 98 with any postdischarge absence.

Among 202 school-enrolled children without preexisting comorbidity, 129 (63.9%) missed school after discharge. Median duration of postdischarge school absence was 6.5 days (IQR, 0-20.7 days) overall and 16.4 days (IQR, 7.9-34.3 days) among the 129 with any postdischarge absence. Among 197 school-enrolled children with preexisting comorbidity, 150 (76.1%) missed school after discharge. Median duration of postdischarge school absence was 10.7 days (IQR 1.0-40.9 days) overall and 17.1 days (IQR, 7.9-57.9 days) among the 150 with any postdischarge absence. Rates of postdischarge work absenteeism among primary caregivers did not differ by child age category (eTable 7 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

In this longitudinal follow-up of the RESTORE trial cohort, 69.9% of patients who survived pediatric acute respiratory failure missed school (broadly defined as school, preschool, or day care) after discharge. Furthermore, 54.7% of primary caregivers missed work after their child’s hospitalization. Importantly, the durations of school and work absenteeism were substantial—a median of nearly 2 five-day school weeks (9.1 days) of postdischarge school absence for children and a median of 1.5 five-day work weeks (8 days) of postdischarge work absence for primary caregivers who missed work. For children 5 years or older, the median duration was even longer (13.3 days). Among children who missed school, the duration of school absenteeism commonly exceeded the threshold for chronic absenteeism (>15 days missed), which is known to be associated with increased risk for a number of negative outcomes, including reduced academic achievement, economic hardship, and poor health outcomes in adulthood.12 These findings suggest that patients who survive pediatric respiratory failure are at increased risk for long-term sequelae not only due to their acute illness but also as a result of school missed during and after hospitalization.

Our study also examined school and work absence among siblings and secondary caregivers, respectively. Only 1 in 5 siblings missed school during the hospitalization, and the duration of absence was modest (median, 3 days). Furthermore, absence after hospitalization was rarer (occurring in only 4.7% of siblings). The rate and duration of absence among secondary caregivers, however, were nearly as high as those among primary caregivers.

As would be expected, worse child health status (eg, preexisting comorbidity, functional impairment) was associated with a greater burden of school and work absence. However, even among children without preexisting comorbidity, almost 63.9% missed school for a median duration of 6.5 days. Unlike prior studies,19,20 we did not find an association between neighborhood income and missed school or work among children or caregivers.

Consistent with prior studies, we found that rates of postdischarge absence differed by hospital diagnosis. Respiratory failure due to asthma or bronchiolitis was associated with a lower burden of school absence than respiratory failure due to pneumonia, sepsis, or other causes. Previous studies have shown that hospitalization for acute medical conditions,21 including infections,22 burns,23 transplant,24 and diabetes,25 are associated with subsequent absenteeism and lower academic achievement. Similarly, chronic health conditions and special health care needs (eg, prescription medications, specialized medical care, or educational services) are associated with school absence.26,27,28

Although it is not surprising that children would miss school during critical illness, the duration of school absence experienced by some children in our study is sufficient to result in long-term academic impairment. School absence in childhood has been associated with worse long-term socioeconomic and health outcomes, including school dropout, depression, substance abuse, and economic hardships in adulthood.12,29,30 The importance of school attendance begins before elementary school, because absence from preschool has been associated with lower levels of kindergarten readiness and increased risk of needing reading intervention by second grade.31 A recent analysis estimated that 5.5 million years of life were potentially lost owing to COVID-19–related school closures during 2020 alone, underscoring the importance of school attendance on health outcomes in adulthood.32 Importantly, the longer the duration of school absence, the greater the risk of impaired academic achievement. Chronic absenteeism (missing >15 days of school)13 is an important threshold associated with lower academic achievement and higher participation in risky health behaviors.12 More than half of the children in our study who missed school after discharge met criteria for chronic absenteeism.

Our study suggests that post-PICU school absenteeism is an important target for future interventions. Although school absenteeism is common after hospitalization and consistently associated with a multitude of negative outcomes, a recent study33 suggested that pediatricians ask about school absence in fewer than half of visits after hospitalization. Future work is needed to understand the barriers to school participation, to develop interventions to mitigate absenteeism, and to help children catch up on missed school.

Consistent with prior studies,4,34,35,36 and not unexpectedly given continued recovery after discharge, caregivers in our study commonly missed work after their child’s hospitalization. Notably, however, our study does not account for changes in informal caregiving practices at home, nor does it quantify the financial cost of missed work. In our cohort, work absence occurred during and after hospitalization and was strongly associated with the duration of child school absence, creating the potential for additive or multiplicative stress on families. Prior studies show 1 in 3 parents worry about job loss or reduced wages when taking time off to care for a sick child37 and that child health conditions are associated with lower parental employment.38,39 Even with employer-based sick leave, paid time off, and federal family leave programs, parents commonly report being unable to miss work for child illness.40 Indeed, only 56% of US employees are eligible for Family Medical Leave Act protections, which guarantee employment protection but do not guarantee wages.41 Parents with access to leave or paid benefits were more likely to miss work when needed by their child, suggesting awareness and access to family leave benefits may decrease this stressful conflict.40 Thus, given the magnitude of missed work found in our study and the hardships described by parents in prior studies, there is a great need for programs and policies to support families during and after pediatric hospitalization.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, follow-up data were not available for all eligible children, creating a potential for bias. However, loss to follow-up was modest (19.8%), and patient characteristics were similar between families completing vs not completing follow-up.10 Second, because follow-up surveys occurred 6 months after PICU discharge, recall bias is possible. However, questions prompted respondents to recall both whether any days were missed and the overall number—thus, data were captured even if caregivers could not recall the exact duration of absence. Third, we assumed the school year to occur from September through June. However, this assumption may underestimate the number of school days missed, especially in children older than 5 years. Fourth, surveys did not differentiate school absence during vs after hospitalization, but we were able to estimate postdischarge absence based on length of hospitalization and total school absence. Fifth, data on prehospitalization school and work absence were not available. However, the rate and duration of school absence in children without preexisting comorbidity were only slightly less than the overall cohort rate and duration, suggesting much of the absence observed was attributable to the hospitalization for respiratory failure.10

Conclusions

In this cohort study, nearly 70% of children hospitalized with acute respiratory failure missed school after discharge, for a median duration of nearly 2 school weeks. Similarly, half of primary caregivers missed work after their child’s hospital discharge. The magnitude of school absenteeism suggests a risk for negative downstream educational, financial, and health outcomes.

eMethods 1. Follow-up Survey Questions

eMethods 2. Measurements

eTable 1. Multivariable Models of Risk Factors to Predict Rate and Duration of School Absence After Hospital Discharge

eTable 2. School and Work Absence According to RESTORE Treatment Group

eTable 3. Patient, Family, and Hospitalization Characteristics Across Duration of School Absence Category During and After Hospitalization (n = 454)

eTable 4. Parent, Family, and Hospitalization Characteristics Across Quartiles of Duration of Postdischarge Work Absence Category in Primary Caregivers (n = 506)

eTable 5. Patient, Family, and Hospitalization Characteristics Across Quartiles of Duration of Postdischarge Work Absence Category Among Secondary Caregivers (n = 614)

eTable 6. Postdischarge School Absenteeism by Age Group

eTable 7. Postdischarge Employment and Work Absenteeism by Age Group

Nonauthor Collaborators of the RESTORE Study

References

- 1.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):502-509. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manning JC, Pinto NP, Rennick JE, Colville G, Curley MAQ. Conceptualizing post intensive care syndrome in children—the PICS-p Framework. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(4):298-300. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson RS, Choong K, Colville G, et al. Life after critical illness in children-toward an understanding of pediatric post-intensive care syndrome. J Pediatr. 2018;198:16-24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.12.084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shudy M, de Almeida ML, Ly S, et al. Impact of pediatric critical illness and injury on families: a systematic literature review. Pediatrics. 2006;118(suppl 3):S203-S218. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0951B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamdar BB, Sepulveda KA, Chong A, et al. Return to work and lost earnings after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a 5-year prospective, longitudinal study of long-term survivors. Thorax. 2018;73(2):125-133. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodgson CL, Haines KJ, Bailey M, et al. ; ICU-Recovery Investigators . Predictors of return to work in survivors of critical illness. J Crit Care. 2018;48:21-25. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McPeake J, Mikkelsen ME, Quasim T, et al. Return to employment after critical illness and its association with psychosocial outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(10):1304-1311. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201903-248OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curley MAQ, Wypij D, Watson RS, et al. ; RESTORE Study Investigators and the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators Network . Protocolized sedation vs usual care in pediatric patients mechanically ventilated for acute respiratory failure: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(4):379-389. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.18399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ClinicalTrials.gov . Sedation Management in Pediatric Patients With Acute Respiratory Failure (the RESTORE Study). NCT00814099. Accessed November 15, 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00814099

- 10.Watson RS, Asaro LA, Hertzog JH, et al. ; RESTORE Study Investigators and the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network . Long-term outcomes after protocolized sedation versus usual care in ventilated pediatric patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(11):1457-1467. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201708-1768OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson RS, Asaro LA, Hutchins L, et al. Risk factors for functional decline and impaired quality of life after pediatric respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(7):900-909. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201810-1881OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allison MA, Attisha E; Council on School Health. The link between school attendance and good health. Pediatrics. 2019;143(2):e20183648. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Department of Education. Chronic Absenteeism in the Nation’s Schools. Updated January 2019. Accessed September 20, 2020. https://www2.ed.gov/datastory/chronicabsenteeism.html

- 14.Fiser DH. Assessing the outcome of pediatric intensive care. J Pediatr. 1992;121(1):68-74. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)82544-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollack MMM, Patel KMP, Ruttimann UEP. PRISM III: an updated Pediatric Risk of Mortality score. Crit Care Med. 1996;24(5):743-752. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199605000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonckheere AR. A distribution-free k-sample test against ordered alternatives. Biometrika. 1954;41(1/2):133-145. doi: 10.2307/2333011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Natale JE, Lebet R, Joseph JG, et al. ; Randomized Evaluation of Sedation Titration for Respiratory Failure (RESTORE) Study Investigators . Racial and ethnic disparities in parental refusal of consent in a large, multisite pediatric critical care clinical trial. J Pediatr. 2017;184:204-208.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Natale JE, Asaro LA, Joseph JG, et al. ; RESTORE Study Investigators . Association of race and ethnicity with sedation management in pediatric intensive care. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(1):93-102. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201912-872OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gottfried MA. Can neighbor attributes predict school absences? Urban Educ. 2014;49(2):216-250. doi: 10.1177/0042085913475634 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrissey TW, Hutchison L, Winsler A. Family income, school attendance, and academic achievement in elementary school. Dev Psychol. 2014;50(3):741-753. doi: 10.1037/a0033848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bortes C, Strandh M, Nilsson K. Health problems during childhood and school achievement: exploring associations between hospitalization exposures, gender, timing, and compulsory school grades. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Köhler-Forsberg O, Sørensen HJ, Nordentoft M, McGrath JJ, Benros ME, Petersen L. Childhood infections and subsequent school achievement among 598 553 Danish children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37(8):731-737. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azzam N, Oei J-L, Adams S, et al. Influence of early childhood burns on school performance: an Australian population study. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(5):444-451. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilmour SM, Sorensen LG, Anand R, Yin W, Alonso EM; SPLIT Research Consortium . School outcomes in children registered in the Studies for Pediatric Liver Transplant (SPLIT) consortium. Liver Transpl. 2010;16(9):1041-1048. doi: 10.1002/lt.22120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCarthy AM, Lindgren S, Mengeling MA, Tsalikian E, Engvall J. Factors associated with academic achievement in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(1):112-117. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.1.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forrest CB, Bevans KB, Riley AW, Crespo R, Louis TA. School outcomes of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2011;128(2):303-312. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reuben CA, Pastor PN. The effect of special health care needs and health status on school functioning. Disabil Health J. 2013;6(4):325-332. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bethell C, Forrest CB, Stumbo S, Gombojav N, Carle A, Irwin CE. Factors promoting or potentially impeding school success: disparities and state variations for children with special health care needs. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(suppl 1):S35-S43. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-0993-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schoeneberger JA. Longitudinal attendance patterns: developing high school dropouts. Clearing House. 2012;85(1):7-14. doi: 10.1080/00098655.2011.603766 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ansari A, Hofkens TL, Pianta RC. Absenteeism in the first decade of education forecasts civic engagement and educational and socioeconomic prospects in young adulthood. J Youth Adolesc. 2020;49(9):1835-1848. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01272-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ehrlich SB, Gwynne JA, Allensworth EM. Pre-kindergarten attendance matters: early chronic absence patterns and relationships to learning outcomes. Early Child Res Q. 2018;44:136-151. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.02.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christakis DA, Van Cleve W, Zimmerman FJ. Estimation of US children’s educational attainment and years of life lost associated with primary school closures during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2028786. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.28786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kastner K, Pinto N, Msall ME, Sobotka S. PICU follow-up: the impact of missed school in a cohort of children following PICU admission. Crit Care Explor. 2019;1(8):e0033-e0034. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mumford V, Baysari MT, Kalinin D, et al. Measuring the financial and productivity burden of paediatric hospitalisation on the wider family network. J Paediatr Child Health. 2018;54(9):987-996. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leader S, Jacobson P, Marcin J, Vardis R, Sorrentino M, Murray D. A method for identifying the financial burden of hospitalized infants on families. Value Health. 2002;5(1):55-59. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2002.51076.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clark ME, Cummings BM, Kuhlthau K, Frassica N, Noviski N. Impact of pediatric intensive care unit admission on family financial status and productivity: a pilot study. J Intensive Care Med. 2019;34(11-12):973-977. doi: 10.1177/0885066617723278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.CS Mott Children’s Hospital. Mott poll report: sick kids, struggling parent. October 22, 2012. Accessed September 20, 2020. https://mottpoll.org/reports-surveys/sick-kids-struggling-parents

- 38.Kuhlthau KA, Perrin JM. Child health status and parental employment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(12):1346-1350. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.12.1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hope S, Pearce A, Whitehead M, Law C. Effects of child long-term illness on maternal employment: longitudinal findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27(1):48-52. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckw132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chung PJ, Garfield CF, Elliott MN, Carey C, Eriksson C, Schuster MA. Need for and use of family leave among parents of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5):e1047-e1055. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown S, Herr J, Roy R, Klerman JA. Employee and worksite perspectives of the FMLA: who is eligible? July 2020. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/evaluation/pdf/WHD_FMLA2018PB1WhoIsEligible_StudyBrief_Aug2020.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. Follow-up Survey Questions

eMethods 2. Measurements

eTable 1. Multivariable Models of Risk Factors to Predict Rate and Duration of School Absence After Hospital Discharge

eTable 2. School and Work Absence According to RESTORE Treatment Group

eTable 3. Patient, Family, and Hospitalization Characteristics Across Duration of School Absence Category During and After Hospitalization (n = 454)

eTable 4. Parent, Family, and Hospitalization Characteristics Across Quartiles of Duration of Postdischarge Work Absence Category in Primary Caregivers (n = 506)

eTable 5. Patient, Family, and Hospitalization Characteristics Across Quartiles of Duration of Postdischarge Work Absence Category Among Secondary Caregivers (n = 614)

eTable 6. Postdischarge School Absenteeism by Age Group

eTable 7. Postdischarge Employment and Work Absenteeism by Age Group

Nonauthor Collaborators of the RESTORE Study