Key Points

Question

Are there differences in survival among patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) who are members of racial and ethnic minority groups, and what are the sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors associated with stage of presentation among these patients?

Findings

In this cohort study of 21 966 patients with HNC who belong to racial and ethnic minority groups, Black individuals had poorer outcomes than Asian Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Hispanic individuals. Race, sex, health insurance, marital status, and socioeconomic status were significantly associated with HNC-specific survival and stage of presentation.

Meaning

These study findings can potentially inform the development of interventions aimed at ameliorating cancer health disparities among patients with HNC belong to racial and ethnic minority groups.

Abstract

Importance

Approximately 1 in 5 new patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) in the US belong to racial and ethnic minority groups, but their survival rates are worse than White individuals. However, because most studies compare Black vs White patients, little is known about survival differences among members of racial and ethnic minority groups.

Objective

To describe differential survival and identify nonclinical factors associated with stage of presentation among patients with HNC belonging to racial and ethnic minority groups.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based retrospective cohort study used data from the 2007 to 2016 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database and included non-Hispanic Black, Asian Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Hispanic patients with HNC. The data were analyzed from December 2020 to May 2021.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Outcomes were time to event measures: (HNC-specific and all-cause mortality) and stage of presentation. Covariates included nonclinical (age at diagnosis, sex, race and ethnicity, insurance status, marital status, and a composite socioeconomic status [SES]) and clinical factors (stage, cancer site, chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery). A Cox regression model was used to adjust associations of covariates with the hazard of all-cause death, and a Fine and Gray competing risks proportional hazards model was used to estimate associations of covariates with the hazard of HNC-specific death. A proportional log odds ordinal logistic regression identified which nonclinical factors were associated with stage of presentation.

Results

There were 21 966 patients with HNC included in the study (mean [SD] age, 56.02 [11.16] years; 6072 women [27.6%]; 9229 [42.0%] non-Hispanic Black, 6893 [31.4%] Hispanic, 5342 [24.3%] Asian/Pacific Islander, and 502 [2.3%] American Indian/Alaska Native individuals). Black patients had highest proportion with very low SES (3482 [37.7%]) and the lowest crude 5-year overall survival (46%). After adjusting for covariates, Hispanic individuals had an 11% lower subdistribution hazard ratio (sdHR) of HNC-specific mortality (sdHR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.83-0.95), 15% lower risk for Asian/Pacific Islander individuals (sdHR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.78-0.93), and a trending lower risk for American Indian/Alaska Native individuals (sdHR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.71-1.01), compared with non-Hispanic Black individuals. Race, sex, insurance, marital status, and SES were consistently associated with all-cause mortality, HNC-specific mortality, and stage of presentation, with non-Hispanic Black individuals faring worse compared with individuals of other racial and ethnic minority groups.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study that included only patients with HNC who were members of racial and ethnic minority groups, Black patients had significantly worse outcomes that were not completely explained by stage of presentation. There may be unexplored multilevel factors that are associated with social determinants of health and disparities in HNC outcomes.

This cohort study examines differential survival and identifies nonclinical factors associated with stage of presentation among patients with head and neck cancer who belong to racial and ethnic minority groups.

Introduction

In the US, head and neck cancer (HNC) comprises 3.5% of newly diagnosed cancers, with an estimated 66 000 new cases in 2020.1 Patients from racial and ethnic minority groups comprise only 12% to 20% of these new cases2,3,4; however, they also have a substantially greater mortality. For example, the laryngeal cancer mortality rate in White patients is 1.7 per 100 000, but this is double for Black male patients (3.2 per 100 000). Similarly, the mortality rate for oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer is 4.0 per 100 000 for White men vs 4.8 per 100 000 for Black men.1 Only 2 other cancer sites have a worse Black vs White patient relative survival gap than HNC.1

Studies investigating outcomes in HNC5,6,7,8,9,10 have shown that an advanced stage of presentation is strongly associated with outcomes, with Black patients more likely to receive a diagnosis of an advanced-stage disease than White patients.5,6,10,11 Additionally, Black patients are more likely to receive inadequate care, experience greater delays in receipt of guideline-driven care, and have a greater comorbidity burden.6,12,13 However, most studies that describe the racial disparity in HNC have focused almost exclusively on Black vs White differences.5,6,7,8,9,10,14,15,16 To our knowledge, little is known about the factors that are associated with late stage of presentation among survivors of HNC belonging to racial and ethnic minority groups, a heterogeneous subpopulation that is disparately affected by social determinants of health.

We hypothesized that significant disparities exist among patients with HNC belonging to racial and ethnic minority groups based on their stage of presentation and outcomes. To test this hypothesis, we aimed to (1) identify nonclinical factors associated with late stage of presentation, (2) estimate survival differences, and (3) analyze clinical, sociodemographic, and socioeconomic status (SES) factors contributing to the differences in outcomes among survivors of HNC belonging to racial and ethnic minority groups.

Methods

Data Source

We used publicly available, deidentified data from the 2007 to 2016 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database of the National Cancer Institute, which were abstracted on December 2, 2020. The study received institutional review board approval from Duke University, which determined that the study did not require additional review as data were deidentified and publicly available. The study cohort included patients 18 years or older at diagnosis who belonged to a racial and ethnic minority group and had received a diagnosis of a malignant primary HNC using the primary site labeled variable in the SEER database matching the values nasopharynx; nose, nasal cavity and middle ear; oropharynx; other oral cavity and pharynx; salivary gland; tongue; tonsil; floor of mouth; gum and other mouth; hypopharynx; larynx; and lip. We excluded patients if the only documentation of cancer was from a death certificate, autopsy, if the cause of death was unknown, or there was missing survival time while listed as alive. We abstracted data using SEER*Stat, version 8.3.5 (National Cancer Institute).17

Outcome and Study Variables

There were 3 outcome variables of interest: death due to primary HNC using SEER’s cause-specific death classification variable (HNC-specific mortality),18 death of all causes (all-cause mortality), and the other tumor stage of presentation as defined by SEER summary stages (localized, regional, or distant). We obtained demographic variables, including age at diagnosis, sex, race, ethnicity, insurance status, and marital status. Race and ethnicity were combined into a single variable. Further, we created a composite index of SES using a principal components analysis following Yost et al.19 Six county-level variables were used in developing the composite index, including 2 measures of education (percentage with less than a high school education, American Community Survey [ACS] 2013-2017; percentage with at least bachelor degree, ACS 2013-2017), 2 measures of income and poverty level (percentage of persons with incomes less than 200% of the poverty line, ACS 2013-2017; median household income in tens of thousands, ACS 2013-2017), a measure of occupation (percentage unemployed, ACS 2013-2017), and 1 measure of living costs (normalized cost-of-living index, 2004). We extracted the first axis of the principal components analysis, which accounted for approximately 68% of variance, to represent SES. This composite index included SES indicators that were loaded20 as the percentage of people with a bachelor’s degree (−0.44), percentage of persons with an income less than 200% of the poverty line (0.45), percentage of those with less than a high school education (0.34), percentage of people unemployed (0.36), normalized cost-of-living index in 2004 (−0.39), and median household income (−0.46). The negative loads indicated an inverse association to the SES index, and larger component scores on the SES index indicated a lower SES level. We further categorized the SES index into quartiles (very low, low, medium, or high SES). Other variables included year of diagnosis, cancer site (eg, oropharynx, larynx, hypopharynx, and oral cavity) and treatment modality (surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy).

Statistical Analysis

Patient baseline characteristics were compared across race and ethnicity using the Pearson χ2 test for categorical variables and 1-way analysis of variance for continuous variables. Kaplan-Meier curves estimated the crude association between all-cause mortality and race and ethnicity. Further, we used a Cox regression model to assess adjusted associations of covariates (nonclinical [age at diagnosis, sex, race and ethnicity, insurance status, marital status, and SES] and clinical [stage, cancer site, chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery]) with the hazard of death (all-cause mortality) and right-censoring patients who were alive or lost to follow-up, with a time of 0 being the date of HNC diagnosis. Next, a Fine and Gray competing risks proportional hazards model19 adjusted the association of covariates of interest with the hazard of HNC-specific death. We considered death of other causes as a competing event, and those who were alive or lost to follow-up by the study end date were right censored. We ran the Cox model using package survival,21 Fine and Gray model using package cmprsk,22 and packages ggplot2,23 and survminer24 for visualizing these models.

Lastly, we used a proportional log odds ordinal logistic regression to identify which sociodemographic factors were associated with stage of presentation in people of racial and ethnic minority groups. Because stage of presentation was the outcome of interest for this aim, we excluded patients with unknown or unstaged disease (10 597 [48.2%]). A proportional log odds regression was used to identify factors associated with stage of presentation because of its ordinal nature.25 We used the function clm in package ordinal in R26 to run a model that included the main effects for all variables. We report goodness of fit tests for proportional odds (Brant test) and proportional hazards assumptions (Schoenfeld residual test), but recognize that these tests can be sensitive to mild deviations in cases in which sample sizes are large. All statistical analyses were performed using R, version 4.0.2 (R Foundation), and statistical significance was set at P < .05.27

Results

Patient Characteristics

There were 21 966 patients with HNC included in the study cohort (eFigure in the Supplement). Table 1 presents patient baseline characteristics, including demographic, disease, and treatment characteristics of patients. Non-Hispanic Black patients comprised 9229 (42.0%) of the study cohort, Hispanic patients 6893 (31.4%), Asian/Pacific Islander patients 5342 (24.3%), and American Indian/American Native patients 502 (2.3%). The study included 15 894 men (72.4%), 10 879 married individuals (49.5%), and 14 258 individuals (64.9%) with private insurance. The mean (SD) age of diagnosis was 56.02 (11.16) years. The highest proportions of non-Hispanic Black patients (3482 [37.7%]) had a very low SES, the highest proportions of Hispanic patients had a low SES (2196 [31.9%]), most American Indian/Alaska Native individuals had a medium SES (2225 [44.8%]), and most Asian/Pacific Islander individuals had a high SES (2822 [52.8%]). Based on regions, more than half the patients in the study cohort resided in the West (12 538 [57.1%]), whereas 5261 (24.0%) were in the South, 2737 (12.5%) in the Northeast, and 1430 (6.5%) in the Midwest. There were substantially more oral cavity (8957 [40.8%]) HNC cases than all other cancer sites. Stage of presentation was localized for 4909 (22.3%), regional for 3963 (18.0%), and distant for 2497 (11.4%); 10 597 patients (48.2%) were in the unknown or unstaged category. Treatment involved surgery for 10 078 (45.9%) of the study cohort, radiotherapy for 15 264 (69.5%), and chemotherapy for 11 100 (50.5%).

Table 1. Patient Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Non-Hispanic Black | Hispanic | Asian/Pacific Islander | American Indian/Alaska Native | |

| No. | 21 966 | 9229 | 6893 | 5342 | 502 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 56.02 (11.16) | 57.07 (9.87) | 55.70 (11.84) | 54.52 (12.23) | 57.16 (9.88) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 6072 (27.6) | 2438 (26.4) | 1851 (26.9) | 1667 (31.2) | 116 (23.1) |

| Male | 15 894 (72.4) | 6791 (73.6) | 5042 (73.1) | 3675 (68.8) | 386 (76.9) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 10 879 (49.5) | 3026 (32.8) | 3780 (54.8) | 3833 (71.8) | 240 (47.8) |

| Unmarried | 11 087 (50.5) | 6203 (67.2) | 3113 (45.2) | 1509 (28.2) | 262 (52.2) |

| Insurance | |||||

| Private insurance | 14 258 (64.9) | 5531 (59.9) | 4394 (63.7) | 4028 (75.4) | 305 (60.8) |

| Medicaid | 6104 (27.8) | 2892 (31.3) | 1932 (28.0) | 1096 (20.5) | 184 (36.7) |

| Uninsured | 1604 (7.3) | 806 (8.7) | 567 (8.2) | 218 (4.1) | 13 (2.6) |

| SES | |||||

| High | 5458 (24.8) | 1139 (12.3) | 1427 (20.7) | 2822 (52.8) | 70 (13.9) |

| Medium | 5452 (24.8) | 2698 (29.2) | 1615 (23.4) | 914 (17.1) | 225 (44.8) |

| Low | 5337 (24.3) | 1910 (20.7) | 2196 (31.9) | 1156 (21.6) | 75 (14.9) |

| Very low | 5719 (26.0) | 3482 (37.7) | 1655 (24.0) | 450 (8.4) | 132 (26.3) |

| US region | |||||

| South | 5261 (24.0) | 4596 (49.8) | 363 (5.3) | 269 (5.0) | 33 (6.6) |

| West | 12 538 (57.1) | 2188 (23.7) | 5424 (78.7) | 4489 (84.0) | 437 (87.1) |

| Northeast | 2737 (12.5) | 1253 (13.6) | 987 (14.3) | 486 (9.1) | 11 (2.2) |

| Midwest | 1430 (6.5) | 1192 (12.9) | 119 (1.7) | 98 (1.8) | 21 (4.2) |

| Cancer site | |||||

| Oropharynx | 3362 (15.3) | 1597 (17.3) | 1225 (17.8) | 449 (8.4) | 91 (18.1) |

| Larynx | 4882 (22.2) | 2882 (31.2) | 1410 (20.5) | 501 (9.4) | 89 (17.7) |

| Hypopharynx | 1056 (4.8) | 601 (6.5) | 265 (3.8) | 158 (3.0) | 32 (6.4) |

| Oral cavity | 8957 (40.8) | 3304 (35.8) | 3179 (46.1) | 2261 (42.3) | 213 (42.4) |

| Other | 3709 (16.9) | 845 (9.2) | 814 (11.8) | 1973 (36.9) | 77 (15.3) |

| Stage | |||||

| Localized | 4909 (22.3) | 1921 (20.8) | 1782 (25.9) | 1121 (21.0) | 85 (16.9) |

| Regional | 3963 (18.0) | 1876 (20.3) | 1307 (19.0) | 671 (12.6) | 109 (21.7) |

| Distant | 2497 (11.4) | 1402 (15.2) | 708 (10.3) | 336 (6.3) | 51 (10.2) |

| Unknown/unstaged | 10 597 (48.2) | 4030 (43.7) | 3096 (44.9) | 3214 (60.2) | 257 (51.2) |

| Radiation | |||||

| Yes | 15 264 (69.5) | 6640 (71.9) | 4542 (65.9) | 3707 (69.4) | 375 (74.7) |

| No | 6702 (30.5) | 2589 (28.1) | 2351 (34.1) | 1635 (30.6) | 127 (25.3) |

| Surgery | |||||

| Yes | 10 078 (45.9) | 3519 (38.1) | 3706 (53.8) | 2633 (49.3) | 220 (43.8) |

| No | 11 888 (54.1) | 5710 (61.9) | 3187 (46.2) | 2709 (50.7) | 282 (56.2) |

| Chemotherapy | |||||

| Yes | 11 100 (50.5) | 4814 (52.2) | 3209 (46.6) | 2793 (52.3) | 284 (56.6) |

| No | 10 866 (49.5) | 4415 (47.8) | 3684 (53.4) | 2549 (47.7) | 218 (43.4) |

Abbreviation: SES, socioeconomic status.

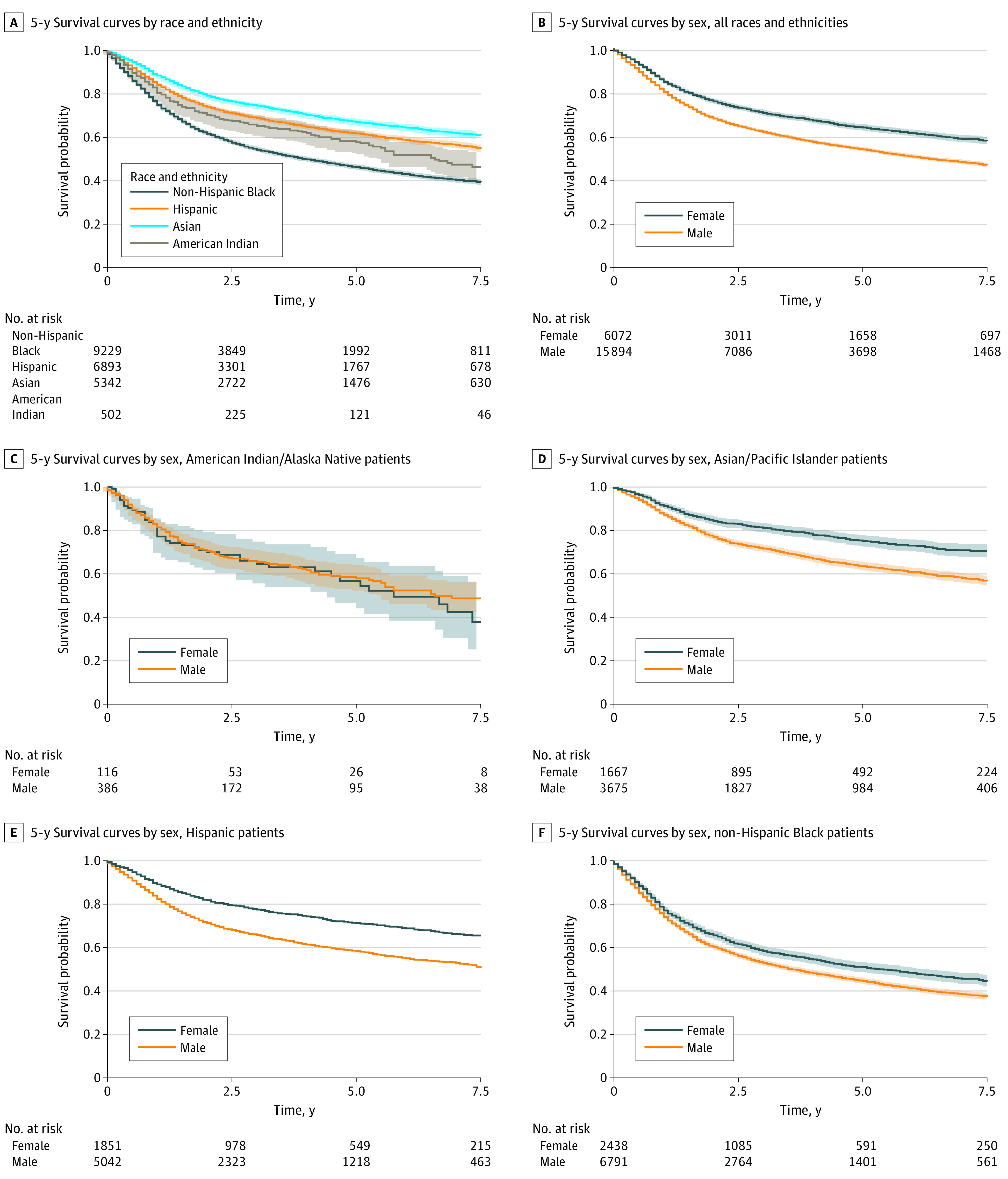

Unadjusted Overall Survival

Unadjusted 5-year overall survival in patients with HNC significantly differed across categories for all study variables of interest. Five-year overall survival was lowest among non-Hispanic Black individuals (46%; 95% CI, 45%-47%), differing significantly from 3 racial and ethnic minority groups: Hispanic (62%; 95% CI, 60%-63%), Asian/Pacific Islander (67%; 95% CI, 66%-69%), and American Indian/Alaska Native individuals (58%; 95% CI, 53%-63%). Women with HNC had much better overall survival (64%; 95% CI, 62%-65%) compared with men (53%; 95% CI, 53%-54%). Patients with HNC with private insurance had the highest overall survival (63%; 95% CI, 62%-64%), with much lower survival for patients with HNC with Medicaid (42%; 95% CI, 41%-44%) and uninsured patients with HNC (49%; 95% CI, 46%-52%). Married patients (65%; 95% CI, 64%-66%) had the highest overall survival, whereas unmarried patients with HNC had poorer survival over time (49%; 95% CI, 47%-49%). Patients with HNC with a high SES (65%; 95% CI, 64%-67%) had the highest overall survival compared with patients in the other groups, particularly those with a very low SES with the lowest survival (50%; 95% CI, 48%-51%). For US geographic regions, patients in the West (62%; 95% CI, 61%-63%) had the highest overall survival compared with patients in the South (46%; 95% CI, 45%-48%), Northeast (55%; 95% CI, 53%-58%), and Midwest (47%; 95% CI, 44%-50%). Overall survival was moderately high for patients with HNC in the oral cavity (60%; 95% CI, 59%-61%), other sites (60%; 95% CI, 58%-62%), oropharynx (57%; 95% CI, 55%-59%), and larynx (54%; 95% CI, 52%-55%), but dramatically low for HNC in the hypopharynx (27%; 95% CI, 24%-30%). Overall survival was highest for localized stage of presentation (78%; 95% CI, 77%-79%) and lower for regional (51%; 95% CI, 50%-53%), with the lowest rates for tumors that presented at distant stages (31%; 95% CI, 29%-33%). Survival curves by race and ethnicity and sex are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Five-Year Survival Curves in Patients With Head and Neck Cancer by Race and Ethnicity and by Sex.

Five-year survival curves in patients with head and neck cancer by race and ethnicity (A), for all race and ethnicity minority groups combined (B), and for each race and ethnicity minority group separately (C-F). Censoring not shown.

Multivariable Adjusted Survival

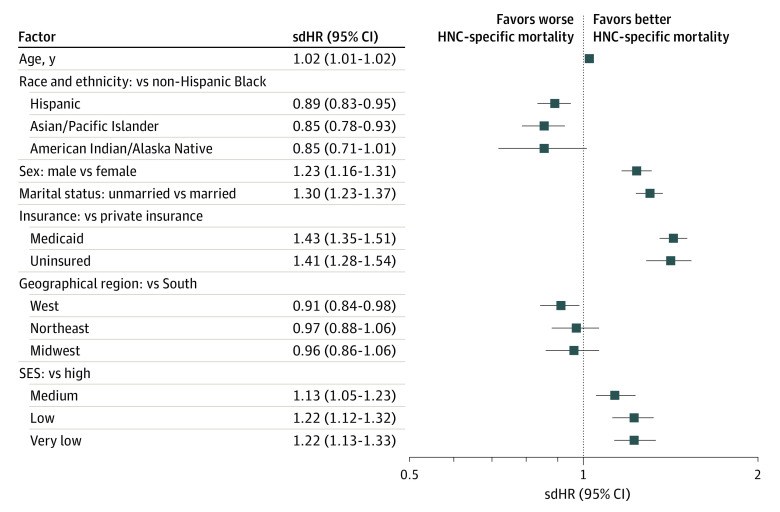

Similar associations were observed for multivariable adjusted all-cause mortality (Figure 2) and HNC-specific mortality outcomes (using the Fine and Gray model; Figure 3). In the fully adjusted Fine and Gray model, non-Hispanic Black patients differed from all other racial and ethnic minority groups in the subdistribution hazard for HNC-specific mortality. Compared with non-Hispanic Black patients, Hispanic patients had an 11% lower subdistribution hazard ratio (sdHR) of HNC-specific mortality (sdHR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.83-0.95) and Asian/Pacific Islander individuals a 15% lower risk (sdHR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.78-0.93), while American Indian/Alaska Native individuals trended toward lower risk (sdHR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.71-1.01). Men had a 21% increase in risk of HNC-specific mortality compared with women (sdHR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.16-1.31). Compared with privately insured patients, Medicaid-insured (sdHR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.35-1.51) and uninsured patients (sdHR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.28-1.54) were similarly worse off, with a more than 40% increase in risk of HNC-specific mortality. Unmarried patients with HNC (sdHR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.23-1.37) had their risk of HNC-specific mortality increased by 30% compared with married patients with HNC. Compared with patients with a high SES, there was a significantly higher risk for HNC-specific mortality in patients with a medium (sdHR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.05-1.23), low (sdHR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.12-1.32), and very low SES (sdHR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.13-1.33). Also, for US geographical regions, compared with the South, patients in the West had a 9% decrease in sdHR for HNC-specific mortality, while there were no significant differences for patients in the Northeast (sdHR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.88-1.06) and Midwest (sdHR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.86-1.06).

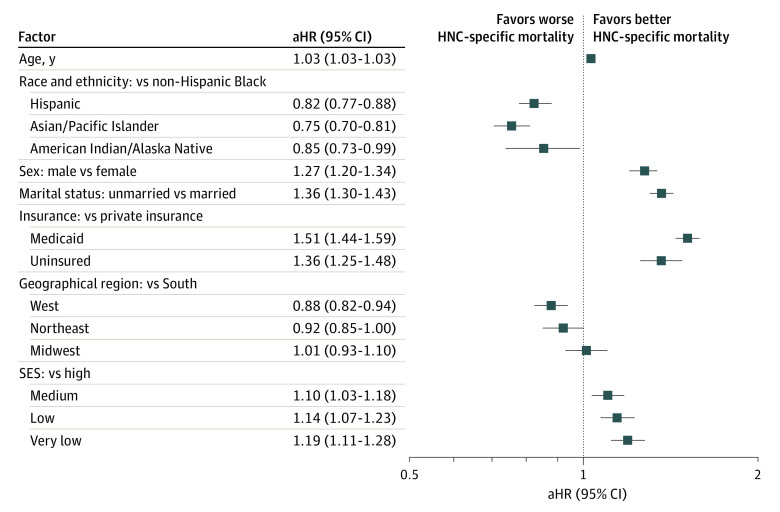

Figure 2. Factors Associated With Overall Survival in Patients With Head and Neck Cancer (HNC).

Cox regression model was adjusted for cancer site (oropharynx vs larynx, hypopharynx, oral cavity, and other), cancer stage (localized, regional, distant, and unknown/unstaged), and treatment regimen, including chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. aHR indicates adjusted hazard ratio; SES, socioeconomic status.

Figure 3. Factors Associated With Head and Neck Cancer (HNC)–Specific Survival.

Fine and Gray Cox regression model was adjusted for cancer site and treatment regimen, including chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery (not shown). sdHR indicates subdistribution hazard ratio; SES, socioeconomic status.

The associations for multivariable-adjusted all-cause mortality were similar to those described previously for HNC-specific mortality with 2 exceptions: first, American Indian/Alaska Native patients had a 15% decreased mortality risk compared with non-Hispanic Black patients (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.85; 95% CI, 0.73-0.99), and second, Medicaid-insured patients (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.44-1.59) seemed to fare worse than privately insured patients by a larger magnitude than the difference for uninsured patients compared with those with private insurance (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.25-1.48) (Figure 3). In general, the survival models on which the reported results were based did not satisfy the proportional hazards assumption (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Thus, the results (hazard ratios as well as sdHRs) should be interpreted as time averaged associations with covariates.

Factors Associated With Stage of Presentation

There were 11 369 patients with stage of presentation information. Results from the adjusted proportional odds logistic regression model showed that all 6 sociodemographic variables in the model had significant main associations with the odds of stage of presentation (Table 2). Hispanic patients had 23% lower odds (aOR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.7-0.85) and Asian patients had 27% lower odds (aOR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.65-0.82) of presenting at a later stage (distant vs regional or localized) compared with non-Hispanic Black patients, whereas American Indian/Alaska Native patients did not differ from non-Hispanic Black patients (aOR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.83-1.35). Similarly, men had 41% higher odds (aOR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.30-1.52) of presenting at a later stage than women. Also, patients with a very low SES had a 21% increase in odds of presenting at a later stage compared with patients with a high SES (aOR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.08-1.35). Medicaid-insured patients showed 60% higher odds (aOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.48-1.74) and uninsured patients (aOR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.48-1.95) showed 70% higher odds of presenting at a distant stage vs regional or localized stage compared with privately insured patients. Also, unmarried patients had 37% higher odds of presenting at a later stage compared with married patients (aOR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.27-1.48). Odds of presentation did not differ significantly by age as well as between each region compared with the South (Table 2). The proportional odds assumption was not satisfied for age and region at the P < .05 threshold (eTable 3 in the Supplement), which was consistent with mild violations that are typical of a large sample size.26

Table 2. Factors Associated With Stage of Presentation Using Proportional Log Odds Model.

| Factors | aOR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|

| Age | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1.06 (0.83-1.35) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.73 (0.65-0.82) |

| Hispanic | 0.77 (0.70-0.85) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1 [Reference] |

| Sex | |

| Female | 1 [Reference] |

| Male | 1.41 (1.30-1.52) |

| Insurance | |

| Private insurance | 1 [Reference] |

| Medicaid | 1.60 (1.48-1.74) |

| Uninsured | 1.70 (1.48-1.95) |

| US region | |

| South | 1 [Reference] |

| West | 0.95 (0.85-1.06) |

| Northeast | 0.96 (0.84-1.10) |

| Midwest | 1.14 (0.99-1.33) |

| Socioeconomic status | |

| High | 1 [Reference] |

| Medium | 1.05 (0.95-1.17) |

| Low | 1.01 (0.90-1.12) |

| Very low | 1.21 (1.08-1.35) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 1 [Reference] |

| Unmarried | 1.37 (1.27-1.48) |

Abbreviation: aOR, adjusted odds ratio.

aOR indicates the increment or decrease in odds of presenting at a distant vs regional or localized stage in 1 category compared with the reference (eg, in men compared with women).

Discussion

This study adds to the literature on survival disparity among patients with HNC. While prior studies have shown disparate outcomes between Black vs White patients with HNC,5,6,7,8,9,10 this study suggests that racial and ethnic disparities persist in a cohort composed solely of members of racial and ethnic minority groups, with non-Hispanic Black patients having poorer survival outcomes than Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Hispanic patients. Also, the study demonstrated an association of nonclinical factors with stage of presentation, as well as differences based on race. Thus, the results from this study suggest that disparities in HNC outcomes extend beyond common contrasts between Black vs White individuals and persist among other racial and ethnic minority groups.

Racial disparity in HNC outcomes has been identified as early as 90 days and up to 25 years postdiagnosis.6,28,29,30,31,32 Previous studies have shown that there is an up to 31% increased mortality risk among Black vs White patients after controlling for known clinical risk factors and sociodemographic factors.28 However, most of these studies involved White patients vs patients from racial and ethnic minority groups, or comparisons between Black vs White patients. This study’s results suggest that after adjusting for clinical, sociodemographic, and SES factors, Black patients fared worse than all other racial and ethnic minority groups. Further studies are needed to understand what underlies this persistent disparity in outcomes among Black patients, including investigating the population-level effect of tumor biology as well as the role of social determinants of health in the incidence and outcomes of HNC based on race and ethnicity.

We found that women had significantly better survival outcomes than men and had significantly greater odds of earlier stage presentation than men. Previous studies have reported similar results.29,33,34 In addition, this study found better survival outcomes among married patients with HNC vs those who were unmarried. Prior studies have described differential survival outcomes for patients with HNC based on marital status and sex, and patients who have never been married, widowed, or divorced have been shown to have greater likelihood of presenting with an advanced-stage HNC and overall poorer outcomes, especially unmarried men.9,33,35,36 Generally, spousal relationships, social networks, relationships, and support systems are important factors for coping and improving quality of life for patients with HNC and may have significant benefits in survival among this cohort of patients. Marital support may facilitate an earlier stage of presentation, which can translate to better survival. Future studies should further explore differences in social support between racial and ethnic minority groups, especially as cultural differences and sex/gender roles in relationships and support systems may be different based on race and ethnicity.

Previous studies have indicated that Black patients are more likely to receive care at low-quality hospitals.37,38 This might be an issue of health care access, which is associated with health insurance status, as shown in this study. We found that Black patients had the highest proportion of being uninsured or having Medicaid, both of which are associated with poorer quality of care.39 While the significant survival difference between privately insured patients with HNC and those with Medicaid has been extensively described in the literature, the results from this study highlight that patients belonging to racial and ethnic minority groups with Medicaid are also as likely, if not more likely, to die of HNC compared with individuals of other fellow racial and ethnic minority groups who are uninsured. Thus, this study’s results support a recently published study describing a health insurance paradox among survivors of HNC survivors in which patients listed as insured through Medicaid do not have any significant survival advantage vs those who are uninsured.40 Medicaid eligibility is based on income relative to federal poverty levels, so the results of this study may be confounded by SES associations with survival. The data also do not allow us to capture temporality in Medicaid status; however, it has been previously documented that some patients with HNC who have payer information listed as Medicaid may have been uninsured when they first presented at the emergency department and received their cancer diagnosis.36,40 Typically, because of factors associated with social determinants of health, patients with a low SES and those without adequate insurance are more likely to put off preventive care and an early visit to the hospital, which partially explains the disparate number of advanced-stage disease cases at presentation seen among these individuals.7,41,42,43,44,45 Perhaps, patients who are eventually provided Medicaid coverage after receiving a diagnosis and being admitted for HNC form most of those classified as insured through Medicaid, potentially masking the benefits of Medicaid insurance compared with being uninsured.36,46 Future longitudinal studies describing patients’ transition from uninsured to insured status through Medicaid might distinguish outcomes for previously uninsured but newly qualified Medicaid patients compared with patients with Medicaid insurance before HNC diagnosis.

Clinical and Public Health Implications

There are currently half a million survivors of HNC in the US,47 and among those belonging to racial and ethnic minority groups, this study suggests that survival among Black patients is significantly lower than all racial and ethnic minority groups after accounting for clinical and nonclinical factors. As research on social determinants of health grows, it is important that the biological basis of health disparities in HNC is adequately understood and described, because access to health care may not fully explain disparities in outcomes, as suggested in this study composed entirely of a cohort of patients with HNC belonging to racial and ethnic minority groups. Understanding the complex interplay between biology and population-level factors might help mitigate disparities and social determinants of health in HNC.

Strengths and Limitations

The results presented in this study should be interpreted within the context of limitations. The SEER data analysis only covered the years 2007 through 2016. As such, recent changes in the effect of insurance status during the past several years were not examined. Also, variables that were missing from the SEER database, such as comorbidities, treatment facility, and alcohol and tobacco use, prevented us from examining the associations of such factors with outcomes of interest among racial and ethnic minority groups; these are factors that may disproportionately affect Black patients compared with White patients. In addition, we were unable to access all social determinant of health factors, such as social and community context and wait times in the medical system for low-income individuals. Assessing their association with outcomes for patients in other racial and ethnic minority groups would yield valuable insights. Finally, SES information in this study was based on the county level, which may inadequately account for individual-level variation in SES. Nevertheless, this study makes valuable contributions to what is known on survival differences among patients with HNC who belong to racial and ethnic minority groups.

Conclusions

The results of this cohort study suggest that significant disparities exist in HNC survival and stage of presentation among patients belonging to racial and ethnic minority groups. These findings could inform interventions aimed at ameliorating health disparities among patients with HNC belonging to racial and ethnic groups.

eTable 1. Test of Proportional Hazards Assumption Using Schoenfield Residual Test on Multivariable Overall Survival Model

eTable 2. Test of Proportional Hazards Assumption Using Schoenfield Residual Test on Fine and Gray Model

eTable 3. Test of Proportional Odds Assumption Using Brant Test in R (package brant; function brant)

Proportional odds assumption violated when P < .05.

eFigure. Consort Diagram for HNC Study Cohort as Abstracted From SEER 18 Database From 2007 Through 2016

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7-30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osazuwa-Peters N, Massa ST, Christopher KM, Walker RJ, Varvares MA. Race and sex disparities in long-term survival of oral and oropharyngeal cancer in the United States. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142(2):521-528. doi: 10.1007/s00432-015-2061-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massa ST, Osazuwa-Peters N, Christopher KM, et al. Competing causes of death in the head and neck cancer population. Oral Oncol. 2017;65:8-15. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cline BJ, Simpson MC, Gropler M, et al. Change in age at diagnosis of oropharyngeal cancer in the United States, 1975-2016. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(11):E3191. doi: 10.3390/cancers12113191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carvalho AL, Nishimoto IN, Califano JA, Kowalski LP. Trends in incidence and prognosis for head and neck cancer in the United States: a site-specific analysis of the SEER database. Int J Cancer. 2005;114(5):806-816. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gourin CG, Podolsky RH. Racial disparities in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(7):1093-1106. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000224939.61503.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graboyes EM, Hughes-Halbert C. Delivering timely head and neck cancer care to an underserved urban population-better late than never, but never late is better. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(11):1010-1011. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.2432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ragin CC, Langevin SM, Marzouk M, Grandis J, Taioli E. Determinants of head and neck cancer survival by race. Head Neck. 2011;33(8):1092-1098. doi: 10.1002/hed.21584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osazuwa-Peters N, Adjei Boakye E, Chen BY, Tobo BB, Varvares MA. Association between head and neck squamous cell carcinoma survival, smoking at diagnosis, and marital status. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(1):43-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zandberg DP, Liu S, Goloubeva O, et al. Oropharyngeal cancer as a driver of racial outcome disparities in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: 10-year experience at the University of Maryland Greenebaum Cancer Center. Head Neck. 2016;38(4):564-572. doi: 10.1002/hed.23933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pulte D, Brenner H. Changes in survival in head and neck cancers in the late 20th and early 21st century: a period analysis. Oncologist. 2010;15(9):994-1001. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodwin WJ, Thomas GR, Parker DF, et al. Unequal burden of head and neck cancer in the United States. Head Neck. 2008;30(3):358-371. doi: 10.1002/hed.20710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee K, Strauss M. Head and neck cancer in blacks. J Natl Med Assoc. 1994;86(7):530-534. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomar SL, Loree M, Logan H. Racial differences in oral and pharyngeal cancer treatment and survival in Florida. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15(6):601-609. doi: 10.1023/B:CACO.0000036166.21056.f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chernock RD, Zhang Q, El-Mofty SK, Thorstad WL, Lewis JS Jr. Human papillomavirus-related squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: a comparative study in whites and African Americans. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137(2):163-169. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jassal JS, Cramer JD. Explaining racial disparities in surgically treated head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(5):1053-1059. doi: 10.1002/lary.29197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Cancer Institute . Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Accessed April 20, 2021. http://www.seer.cancer.gov

- 18.National Cancer Institute . SEER cause-specific death classification. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://seer.cancer.gov/causespecific/

- 19.Yost K, Perkins C, Cohen R, Morris C, Wright W. Socioeconomic status and breast cancer incidence in California for different race/ethnic groups. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12(8):703-711. doi: 10.1023/A:1011240019516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jolliffe IT, Cadima J. Principal component analysis: a review and recent developments. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2016;374(2065):20150202. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2015.0202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.R Foundation for Statistical Computing . A package for survival analysis in R [computer program]. Accessed December 13, 2020. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survival/vignettes/survival.pdf

- 22.Gray B. Package ‘cmprsk’. Accessed January 5, 2021. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/cmprsk/cmprsk.pdf

- 23.Wickham H, Chang W, Henry L, et al. Package ‘ggplot2’. Accessed January 11, 2021. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html

- 24.Kassambara A, Kosinski M, Biecek P, Fabian S. survminer: drawing survival curves using ’ggplot2’. Accessed January 11, 2021.

- 25.Campbell RT, Li X, Dolecek TA, Barrett RE, Weaver KE, Warnecke RB. Economic, racial and ethnic disparities in breast cancer in the US: towards a more comprehensive model. Health Place. 2009;15(3):855-864. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christensen RHB. Analysis of ordinal data with cumulative link models—estimation with the R-package ordinal. Accessed January 11, 2021. http://people.vcu.edu/~dbandyop/BIOS625/CLM_R.pdf

- 27.R Foundation for Statistical Computing . R: A language and environment for statistical computing [computer program]. Accessed December 13, 2020. https://www.r-project.org/

- 28.Hayes DN, Peng G, Pennella E, et al. An exploratory subgroup analysis of race and gender in squamous cancer of the head and neck: inferior outcomes for African American males in the LORHAN database. Oral Oncol. 2014;50(6):605-610. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeSantis CE, Siegel RL, Sauer AG, et al. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2016: Progress and opportunities in reducing racial disparities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(4):290-308. doi: 10.3322/caac.21340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterson CE, Khosla S, Chen LF, et al. Racial differences in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas among non-Hispanic black and white males identified through the National Cancer Database (1998-2012). J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142(8):1715-1726. doi: 10.1007/s00432-016-2182-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaubatz ME, Bukatko AR, Simpson MC, et al. Racial and socioeconomic disparities associated with 90-day mortality among patients with head and neck cancer in the United States. Oral Oncol. 2019;89:95-101. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bukatko AR, Patel PB, Kakarla V, et al. All-cause 30-day mortality after surgical treatment for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in the United States. Am J Clin Oncol. 2019;42(7):596-601. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panth N, Simpson MC, Sethi RKV, Varvares MA, Osazuwa-Peters N. Insurance status, stage of presentation, and survival among female patients with head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(2):385-391. doi: 10.1002/lary.27929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simpson MC, Challapalli SD, Cass LM, et al. Impact of gender on the association between marital status and head and neck cancer outcomes. Oral Oncol. 2019;89:48-55. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inverso G, Mahal BA, Aizer AA, Donoff RB, Chau NG, Haddad RI. Marital status and head and neck cancer outcomes. Cancer. 2015;121(8):1273-1278. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osazuwa-Peters N, Christopher KM, Hussaini AS, Behera A, Walker RJ, Varvares MA. Predictors of stage at presentation and outcomes of head and neck cancers in a university hospital setting. Head Neck. 2016;38(suppl 1):E1826-E1832. doi: 10.1002/hed.24327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shukla N, Ma Y, Megwalu UC. The role of insurance status as a mediator of racial disparities in oropharyngeal cancer outcomes. Head Neck. 2021;43(10):3116-3124. doi: 10.1002/hed.26807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Megwalu UC, Ma Y. Racial/ethnic disparities in use of high-quality hospitals among thyroid cancer patients. Cancer Invest. 2021;39(6-7):482-488. doi: 10.1080/07357907.2021.1938108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta A, Sonis ST, Schneider EB, Villa A. Impact of the insurance type of head and neck cancer patients on their hospitalization utilization patterns. Cancer. 2018;124(4):760-768. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pannu JS, Simpson MC, Adjei Boakye E, et al. Survival outcomes for head and neck patients with Medicaid: a health insurance paradox. Head Neck. 2021;43(7):2136-2147. doi: 10.1002/hed.26682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adjei Boakye E, Johnston KJ, Moulin TA, et al. Factors associated with head and neck cancer hospitalization cost and length of stay-a national study. Am J Clin Oncol. 2019;42(2):172-178. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Massa ST, Osazuwa-Peters N, Adjei Boakye E, Walker RJ, Ward GM. Comparison of the financial burden of survivors of head and neck cancer with other cancer survivors. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(3):239-249. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.3982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graboyes EM, Kompelli AR, Neskey DM, et al. Association of treatment delays with survival for patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(2):166-177. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.2716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Subramanian S, Chen A. Treatment patterns and survival among low-income Medicaid patients with head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139(5):489-495. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.2549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Challapalli SD, Simpson MC, Adjei Boakye E, Pannu JS, Costa DJ, Osazuwa-Peters N. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in adolescents and young adults: survivorship patterns and disparities. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2018;7(4):472-479. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2018.0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bergmark RW, Sedaghat AR. Disparities in health in the United States: an overview of the social determinants of health for otolaryngologists. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2017;2(4):187-193. doi: 10.1002/lio2.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(4):271-289. doi: 10.3322/caac.21349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Test of Proportional Hazards Assumption Using Schoenfield Residual Test on Multivariable Overall Survival Model

eTable 2. Test of Proportional Hazards Assumption Using Schoenfield Residual Test on Fine and Gray Model

eTable 3. Test of Proportional Odds Assumption Using Brant Test in R (package brant; function brant)

Proportional odds assumption violated when P < .05.

eFigure. Consort Diagram for HNC Study Cohort as Abstracted From SEER 18 Database From 2007 Through 2016