Abstract

Background

Physicians from many different specialties see patients suffering from acute pulmonary embolism (PE), which has an incidence of 39–115 cases per 100 000 persons per year. Because PE can be life-threatening, a rapid, targeted response is essential.

Methods

This review is based on pertinent publications retrieved by a selective literature search of international databases, with particular attention to current guidelines and expert opinions.

Results

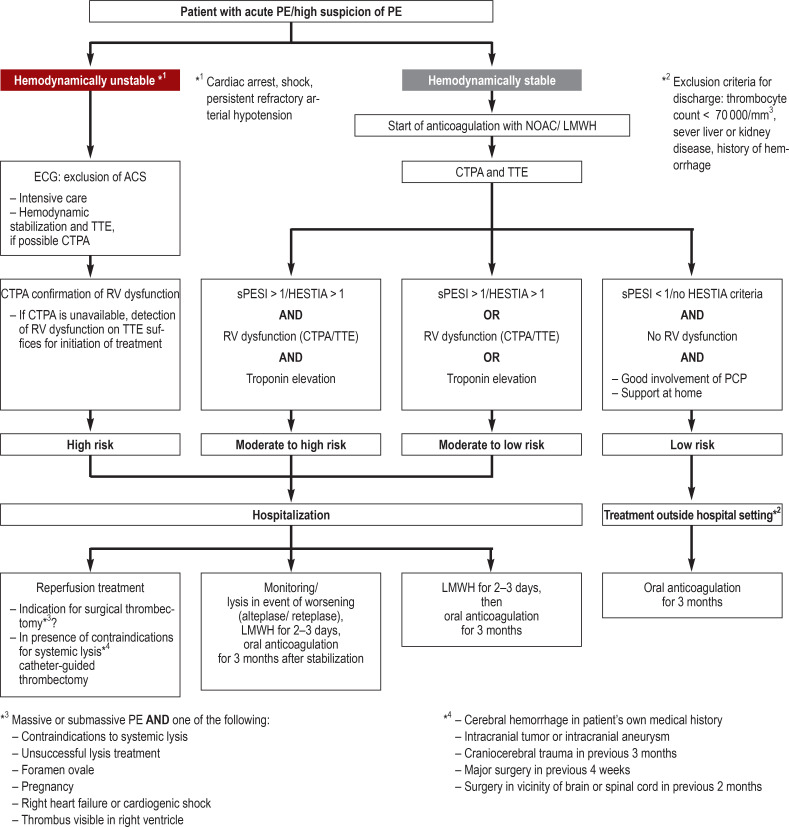

Whenever PE is suspected, clinical assessment tools must be applied for risk stratification and diagnostic evaluation. The PERC (Pulmonary Embolism Rule-out Criteria) and the YEARS algorithm lead to more effective diagnosis. For hemodynamically unstable patients, bedside echocardiography is of high value and enables risk stratification. New oral anticoagulants have fewer hemorrhagic complications than vitamin K antagonists and are not inferior to them with respect to the risk of recurrent PE (hazard ratio 0.84–1.09). The duration of anticoagulation is set according to the risk of recurrence. Systemic thrombolysis is recommended for patients with a high-risk PE, in whom it significantly reduces mortality (odds ratio 0.53, number needed to treat 59). Surgical or interventional techniques can be considered if thrombolysis is contraindicated or unsuccessful.

Conclusion

Newly introduced diagnostic aids and algorithms simplify the diagnosis and treatment of acute PE while continuing to assure a high degree of patient safety.

The symptoms of acute pulmonary embolism (PE) are unspecific, and physicians from a wide range of disciplines may be confronted with the identification and treatment of this potentially life-threatening illness. PE is ranked as the third most common cause of death worldwide (e1), although the mortality has been lowered in recent years by more sensitive diagnostic tests and by treatment according to the prevailing guidelines (1).

Acute pulmonary embolism.

The potentially life-threatening nature of an acute pulmonary embolism demands swift, targeted action.

The incidence of PE is reported as 39–115 cases per 100 000 population, and those over 80 years of age are 8 times more likely to be affected than 40- to 50-year-olds (2, 3). The age-related annual incidence is higher in men, at 130 cases per 100 000, than in women (110 cases per 100 000) (e2). In the age group 16–44 years, however, PE occurs more frequently in women than in men (4, e2). The annual recurrence rate after the end of therapeutic coagulation is 2.5–4.3%, depending on the risk profile (5). The hospital mortality has been reported as 57.4–71.4% after massive PE with cardiac arrest, 5.8–11.2% for submassive PE with right ventricular dysfunction, and 0.4–0.9% for low-risk PE (6). In around 60% of cases the correct diagnosis is made post mortem (e3).

This review summarizes and discusses important new aspects of the diagnosis and treatment of PE, illustrated by a fictive case.

Incidence.

The incidence of PE is reported as 39–115 cases per 100 000 population, and those over 80 years of age are affected eight times more often than 40- to 50-year-olds.

Learning goals

After studying this article, the reader should be able to:

Enumerate the commonly occurring constellations of symptoms and the current treatment recommendations for PE

Describe methods of risk stratification and assess the risk incurred by patients with PE

Discuss critically the central treatment options, depending on the severity of the PE, and the options for follow-up care.

Methods

A selective review of the literature available in international databases (PubMed, Google Scholar, Uptodate), in due consideration of the current guidelines (European Society of Cardiology, American College of Chest Physicians, German Society of Angiology [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Angiologie], Institute for Primary Care [Institut für Hausarztmedizin] at the University of Zurich, Switzerland) and of expert opinion (review articles, Medscape).

Case report: part 1

A 27-year-old woman of normal weight attends an emergency department reporting dyspnea and respiration-dependent right thoracic pain (numeric rating scale [NRS] 5/10), starting in the morning of the day of presentation.

Healthcare epidemiology, initial diagnostic considerations (primary care physician)

Acute dyspnea is a frequently occurring but unspecific symptom, reported by around 1–4% of patients visiting primary care physicians and around 7% of those attending emergency rooms (e4). PE is just one among many differential diagnoses for acute breathlessness (7).

Owing to the unspecific nature of the manifestations, PE can be neither definitively diagnosed nor excluded by clinical examination: symptoms such as dyspnea, thoracic pain, syncope/near-syncope, and hemoptysis are sensitive, but not very specific. They occur with equal frequency in patients with dyspnea and PE and in those in whom PE is suspected initially but then excluded (8).

Verification of clinical suspicion (emergency physician)

Diagnosis.

Owing to the unspecific nature of the manifestations, PE can be neither definitively diagnosed nor excluded by clinical examination: symptoms such as dyspnea, thoracic pain, syncope/near-syncope, and hemoptysis are sensitive, but not very specific.

The suspicion of PE arises from pattern recognition (clinical judgment), the quality of which depends on the individual physician’s clinical experience and has not been reproducibly “defined” in studies. In a patient with suspected PE, the next step is assessment of the clinical probability by means of structured clinical instruments (for example the Wells score and the Geneva score; eTable 1; [5, 9]).

eTable 1. Scoring system for assessment of pre-test probability of a PE*1.

| System | Scoring |

| Wells score (simplified version) | |

| – Clinical signs of DVT *2 | 1 |

| – Alternative diagnosis unlikely | 1 |

| – Operation or fracture in previous month | 1 |

| – History of DVT or PE | 1 |

| – Heart rate ≥ 100/min | 1 |

| – Hemoptysis | 1 |

| – Active neoplasia | 1 |

| Revised Geneva score (simplified version) | |

| – Heart rate >75–94/min | 1 |

| – Heart rate ≥ 95/min | 2 |

| – Pain on palpation of deep leg veins and unilateral lower limb edema | 1 |

| – Unilateral lower limb pain | 1 |

| – History of DVT or PE | 1 |

| – Hemoptysis | 1 |

| – Operation or fracture in previous month | 1 |

| – Active neoplasia | 1 |

| – Age > 65 years | 1 |

| Wells score: ≥ 2 points = probable, 0–1 points = improbable Geneva score: ≥ 2 points = probable, 0–1 points = improbable | |

*1 Simplified Wells score, simplified revised Geneva score

*2 Any swelling and pain on palpation of any segment of the deep leg veins

DVT, Deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism

The ensuing diagnostic testing is determined on the basis of the calculated risk constellation (eTable 1, eBox 2) and the clinical picture (10– 12). Although nicotine consumption is not listed as a risk factor in the current guidelines, various studies have demonstrated that it is in fact an independent risk factor (relative risk [RR] 1.41, 95% confidence interval [1.17; 1.7]) (e5).

eBOX 1. HESTIA criteria (modified from [27]).

HESTIA criteria for exclusion of out-of-hospital care of a patient with PE. If one or more of these criteria are fulfilled, treatment outside the hospital setting is not recommended.

Hemodynamic instability

Necessity of thrombolysis or thrombectomy

Presence of active bleeding or high risk of bleeding

Need for oxygen therapy ≥ 24 h, SpO2 ≤ 90 %

Diagnosis of PE during ongoing anticoagulation treatment

Need for intravenous pain treatment ≥ 24 h

Hospitalization indicated on medical/social grounds

Creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min

Severe liver dysfunction

Pregnancy

History of HIT (heparin-induced thrombocytopenia)

PE, Pulmonary embolism; SpO2, oxygen saturation

D-dimer determination is performed only if the pre-test clinical probability is judged as low or moderate (5). Depending on the D-dimer result, either PE is excluded or another diagnostic procedure is ordered, usually computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA).

An alternative to the Wells score followed by D-dimer determination, developed in 2016, is the YEARS algorithm. This is a simpler and more effective means of diagnosis.

Conventional chest radiography usually yields no specific diagnostic signs of PE, but may uncover alternative reasons for the patient’s symptoms (13). The presence of hypoxemia, hypocapnia, or pathological changes in vital signs may point to PE. In over 40% of patients with PE, however, blood gas analysis shows no abnormalities (14). ECG is normal in 10–25% of patients with PE (e6). The most important ECG parameter for PE is sinus tachycardia or incomplete right bundle block (15). A meta-analysis by Shopp et al. showed that pathological findings such as tachycardia, an S1Q3T3 pattern, complete right bundle block, T-wave negativity in V1–V4, and/or atrial fibrillation are correlated with right ventricular overload and associated with severe disease and elevated mortality (16, e6).

Role of D-dimers (hemostaseologist)

A D-dimer result below a prospectively validated cut-off reduces the likelihood that the patient has thrombosis or pulmonary embolism (17). When using point-of-care assays, one must ensure that these are properly validated and sufficiently accurate (5). The specificity and positive predictive value of a D-dimer result over the cut-off are low. False positives are found in situations with activation of coagulation or fibrinolysis, such as malignant or inflammatory disease, pregnancy, status post trauma, or a long stay in hospital (18).

For patients over 50, an age-adapted interpretation of the D-dimer level is recommended (age in years × 10 ng/mL) (19, 20). A recent innovation is the use of uniform thresholds when employing the YEARS algorithm (21).

Radiography.

Conventional chest radiography usually yields no specific diagnostic signs of PE, but may uncover alternative reasons for the patient’s symptoms.

Note: The YEARS algorithm

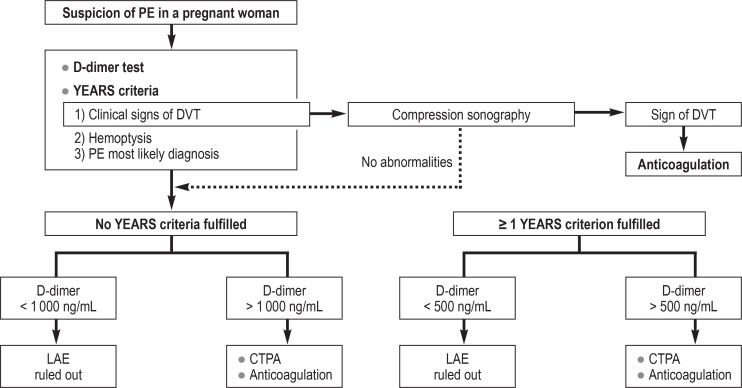

The YEARS algorithm simplifies the initial diagnosis process and reduces the number of CTPA carried out (21). The fixed cut-off of the D-dimer test is replaced by a threshold dependent on one of three clinical parameters, above which CTPA is recommended as the next step. The D-dimer result is thus always assessed in the context of these so-called YEARS criteria (Table 1; [21]). Age-adapted interpretation of the D-dimer level in elderly patients becomes unnecessary. A modified form of the algorithm can also be used in pregnant women (efigure 2) (22).

Table 1. The YEARS algorithm: diagnostic procedure in the event of suspicion of PE (9).

|

YEARS criteria: – Clinical signs of DVT – Hemoptysis – PE most likely diagnosis (treating physician’s judgment) | |||

| No criteria fulfilled | ≥ 1 criteria fulfilled | ||

| D-dimers <1000 ng/ml | D-dimers >1000 ng/mL | D-dimers <500 ng/ml | D-dimers >500 ng/mL |

| PE excluded | CTPA | PE excluded | CTPA |

CTPA, Computer tomography pulmonary angiography; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism

eFigure 2.

YEARS algorithm for diagnosis of pulmonary embolism in pregnant women CTPA, CT pulmonary angiography; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria

The pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) rule was developed for constellations with low PE prevalence (e.g., the primary care setting) (23). PE can be ruled out clinically, with no resort to laboratory tests or diagnostic imaging, if all PERC criteria are satisfied (age <50 years, SpO2 >94%, heart rate <100/min, no history of deep vein thrombosis or PE, no surgery/trauma in the past 4 weeks, no estrogen intake, no unilateral leg swelling). The risk of the combined endpoint death or PE within 3 months was under 0.5% (23), thus not differing from examination by technical means (D-dimer test and/or CTPA; [e7]). However, these study results are to be interpreted with caution: the prevalence of PE was very low in the patient cohorts studied to date. The PERC procedure has not been validated for pregnant women (e7).

Case report: part 2

Pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC).

PE can be ruled out clinically, with no resort to laboratory tests or diagnostic imaging, if all PERC criteria are satisfied.

On questioning, the patient describes amelioration of her symptoms (NRS 2/10). She has been taking an oral contraceptive for the past 2 months. Physical examination shows no abnormality (vital parameters: respiration 15/min, heart rate 102/min, blood pressure 110/60 mm Hg, SpO2 98%, temperature 36.5 °C; blood gas analysis: PaO2 83 mm Hg [11.1 kPa], PaCO2 35 mm Hg [4.7 kPa]). No individual or familial risk of thromboembolism is known.

Emergency physician (case-related statement)

The medical history, physical examination, and risk profile do not indicate a high-risk situation. Conspicuous findings are the persisting sinus tachycardia and moderate hypoxemia. PE therefore cannot be excluded using the PERC algorithm. Oral contraceptive intake is associated with a two- to sixfold risk of PE occurrence. A French cohort study reported an absolute risk of 0.033% for PE in women taking a combined oral contraceptive (RR 2.16 [1.93; 2.41]) (e8– 9).

Case report: part 3

The diagnostic work-up proceeds to ECG, chest radiography, and, given the low pre-test probability, laboratory determination of D-dimers.

With the exception of slight leukocytosis, the patient’s blood tests reveal no pathological findings. The result of D-dimer analysis is 1150 ng/mL (cut-off: <500 ng/mL). CTPA is ordered and shows a right-sided segmental pulmonary embolism. The patient continues to be hemodynamically stable and has no pain at rest.

Note: Imaging procedures in suspected LAE (radiologist)

In the event of high clinical suspicion of PE, or alternatively moderate or low pre-test probability and a positive D-dimer test, the first-line emergency diagnostic procedure is CTPA, which detects PE down to the subsegmental dimension (24). If the pre-test probability of PE was high, a negative CTPA result must be followed by further-reaching risk stratification (5). Modern computed tomography permits dose reduction with no loss of image quality, so pregnant and breast-feeding women do not have to fear radiation-induced damage to their radiosensitive mammary tissue (dose circa 3–10 mSv) (24). Direct fetal impairment is very unlikely. The intrauterine doses of 0.05–0.5 mSv are below the levels at which damage may occur (50–100 mSv) (5). The risk of stochastic radiation damage after prenatal exposure is negligible (25).

PERC and pregnancy.

Use of the PERC algorithm as a diagnostic procedure has not been validated for pregnant women.

Alternative diagnostic procedures play a minor role due to their lack of widespread availability, but may be useful in selected cases. Pulmonary scintigraphy can be carried out in patients with severe renal failure or allergy to contrast medium, and also in pregnant or young women (e10). Magnetic resonance imaging for exclusion of PE is not recommended owing to its low sensitivity and often limited availability.

In the case of relative contraindications for diagnostic computed tomography (e.g., chronic kidney disease, eGFR <30 mL/min, contrast medium allergy, or investigation of a child), one can consider starting with compression sonography of the proximal deep leg veins (sensitivity 41%, specificity 96%) (26). If no difference is found in calf diameter (diameter >2 cm greater than other leg, measured 1 cm below the tibial tuberosity), there is little point in performing duplex sonography, because the likelihood of detecting a thrombus is extremely low. Clinical suspicion and positive compression sonography suffice to confirm the diagnosis of PE (5).

Out-of-hospital care (primary care physician)

The HESTIA criteria (ebox 1) and the (Simplified) Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (sPESI) (table 2) are used to determine whether the patient can be cared for outside the hospital setting. A hemodynamically stable patient whose risk is assessed as low (no HESTIA criteria fulfilled or sPESI ≤ 1) and who has no right ventricular overload can be discharged to their home (27). Further conditions are reliable compliance on the part of the patient, psychosocial stability, and good general health. Furthermore, the patient should be informed about the potential complications of the disease and its treatment. The primary care physician should perform a follow-up examination within a week after discharge (e11).

Table 2. Criteria of the simplified Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (sPESI), which enables estimation of the risk of 30-day mortality after diagnosis of PE (5).

| Parameter | Score |

| – Age (if >80 years) | 1 |

| – Active tumor disease | 1 |

| – Chronic cardiopulmonary disease | 1 |

| – Heart rate >100/min | 1 |

| – Systolic blood pressure <100 mm hg | 1 |

| – SaO2 <90% | 1 |

| 0 points = low (30-day mortality 1%) ≥ 1 point = high (30-day mortality 10.9%) | |

SaO2, Arterial oxygen saturation

In the event of hemodynamic instability (emergency physician)

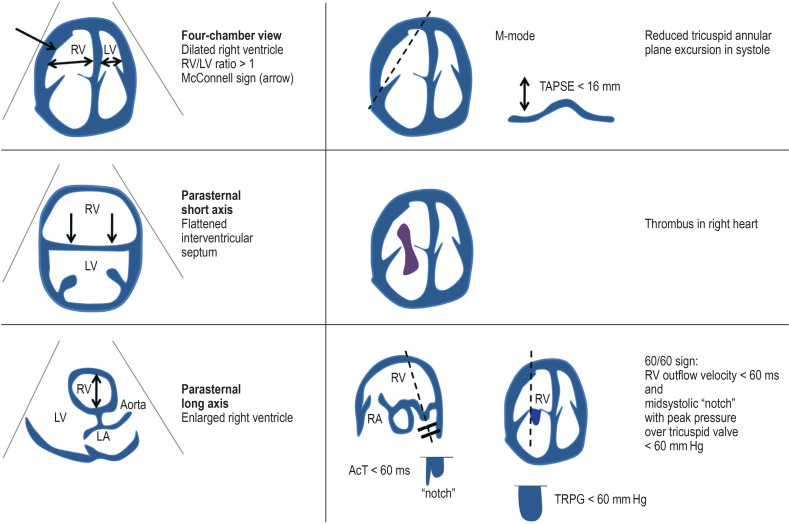

If a patient with suspected PE is hemodynamically unstable, hemodynamic stabilization should be accompanied by transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) to look for signs of right ventricular overload (McConnell sign = akinesia of midsection of right ventricular wall with preserved function of apex; 60/60 sign = RV outflow velocity <60 ms and systolic peak pressure gradient over tricuspid valve <60 mm Hg; thrombi in the right ventricle) or other pathologies (eFigure 1, eTable 2). If hemodynamic instability hinders confirmation of the diagnosis by means of CTPA, the patient should be treated as though they have LE and systemic thrombolysis should be carried out (figure) (5).

eFigure 1.

Echocardiographic signs (transthoracic) of right cardiac overload

AcT, Acceleration time; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; TRPG, tricuspid regurgitation peak gradient

eTable 2. Indicative echocardiographic parameters in suspicion of “high risk”.

| Parameter | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

| Right ventricular overload | 81 | 45 |

| TAPSE < 15.2 mm | 53 | 100 |

|

McConnell sign Akinesia of midsection of right ventricular wall with preserved function of apex |

19 | 100 |

| Right ventricular thrombi | n.d. | n.d. |

|

60/60 sign RV outflow velocity <60 ms and systolic peak pressure gradient over tricuspid valve <60 mm hg |

25 | 94 |

TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; n.d., no data

Figure.

Treatment algorithm in the event of suspicion of PE (modified from [5, 29, 33])

ACS, Acute coronary syndrome; CTPA, computer tomography pulmonary angiography; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparins;

NOAC, new oral anticoagulants; PCP, primary care physician; PE, pulmonary embolism; RV, right ventricular; sPESI, simplified Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography

Supplementary diagnostic imaging.

In the case of relative contraindications for diagnostic computed tomography, one can consider starting with compression sonography of the proximal deep leg veins.

The importance of cardiac function, evidence of right heart overload, and the role of biomarkers (cardiologist)

Standardized clinical risk assessment by means of the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (table 2) should be supplemented by echocardiography (28).

Echocardiography should also be carried out in a situation of hemodynamic stability, for purposes of risk stratification (assessment of right ventricular dysfunction, presence of free floating intracardiac thrombi, etc.). Alternatively, the right ventricular (RV) load can be assessed on the CT scans (RV >LV). If the sPESI is ≤ 1 and there are no contraindications (comorbidity, home care problematic), patients with no RV overload can be discharged early and followed up outside the hospital setting (5, e12). In contrast, RV overload and dysfunction, and an elevated troponin concentration, are associated with increased mortality and require risk-adjusted inpatient treatment including hemodynamic monitoring (5).

Case report: part 4

Procedure in presence of hemodynamic instability.

If a patient with suspected PE is hemodynamically unstable, hemodynamic stabilization should be accompanied by transthoracic echocardiography to look for signs of right ventricular overload.

In the absence of signs of right ventricular overload, the hemodynamically stable patient was sent home with a prescription for 3 months of oral anticoagulants (rivaroxaban 2 × 15 mg/day for 3 weeks, then 20 mg 1 × daily). None of the HESTIA criteria was present, and the sPESI score was 0. The patient was informed that the intake of a combined oral contraceptive can provoke venous thromboembolisms (VTE) and advised to talk to her gynecologist about switching to a non-hormonal method of contraception 4–6 weeks before the end of anticoagulation. Abrupt discontinuation of oral contraceptives is not recommended owing to the risk of hypermenorrhea.

Treatment of PE

The three cornerstones of PE treatment are: hemodynamic stabilization of the patient, initiation of systemic anticoagulation, and pulmonary artery reperfusion (29).

Anticoagulation in PE (hemostaseologist)

In the event of high pre-test probability, anticoagulation (non-vitamin K-dependent anticoagulants [NOAC] or low-molecular-weight heparin [LWMH]) must be started immediately, without waiting for confirmation of the diagnosis. Randomized controlled trials have shown that NOAC are not inferior to vitamin K antagonists regarding the risk of recurrence (HR 0.84–1.09) and are associated with a significantly reduced prevalence of bleeding events (HR 0.31–0.84) (30). The duration of anticoagulant intake is decided individually, based on the risk of recurrence, the bleeding risk (Table 3; eTable 3), and the extent of the VTE, but should not be less than 3–6 months (table 3) (31).

Table 3. Duration of anticoagulation following VTE (modified from [33]).

| Recommended duration of oral anticoagulation after PE | ||

| VTE event | Bleeding risk not elevated | High risk of bleeding*3 |

| Distal DVT, provoked or unprovoked | 3 months | 6–12 weeks |

| Proximal DVT/PE, severe transient RF | 3–6 months | 3 months |

| Proximal DVT/PE, slight transient RF | Indefinite, reduced dose*1; if necessary, limited to 3–6 months*2 | 3 (–6) months |

| Proximal DVT/PE, slight longer-term RF | Indefinite, reduced dose*1 | 3 (–6) months; in individual cases, indefinite at reduced dose*2 |

| Unprovoked proximal DVT/PE | Indefinite | 3 (–6) months; in individual cases, indefinite at reduced dose*2 |

| Recurrent VTE | Indefinite | 3 (–6) months; in individual cases, indefinite at reduced dose*2 |

*1 Dose reduction of apixaban and rivaroxaban possible after 6–12 months

*2 Individual risk/benefit assessment with regard to further risk factors and the patient’s wishes; possible risk stratification for women according to the “Men Continue and HERDOO2” rule: 0–1 points, consider limited anticoagulation; ≥2 points, continuous treatment (criteria, 1 point each: hyperpigmentation, edema, redness of lower limb, persistent D-dimer elevation ≥ 250 ng/mL, BMI ≥ 30 kg/cm2, age ≥ 65 years)

*3 Risk factors for severe bleeding during anticoagulation: arterial hypertension, liver/kidney function impairment, history of stroke or relevant hemorrhage, INR difficult to adjust, age > 65 years, alcohol abuse, thrombocyte aggregation inhibitors, non-steroidal antirheumatics, tumor disease, thrombocytopenia, anemia, diabetes mellitus, reduced functional activity, prone to falling, recent surgery (33)

DVT, Deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; RF, risk factor; VTE, venous thromboembolism

Echocardiography.

Echocardiography should also be carried out in a situation of hemodynamic stability, for purposes of risk stratification.

PESI.

If the sPESI is ≤ 1 and there are no contraindications (comorbidity, home care problematic), patients with no RV overload can be discharged early and followed up outside the hospital setting.

Risk assessment.

RV overload and dysfunction, and an elevated troponin concentration, are associated with increased mortality.

Contraindications to systemic lysis.

Cerebral hemorrhage in patient’s own medical history; intracranial tumor or intracranial aneurysm; craniocerebral trauma in previous 3 months; major surgery in previous 4 weeks; surgery in vicinity of brain or spinal cord in previous 2 months

The central question in evaluating the risk of recurrence is whether the initial event occurred with or without provocation (eTable 3; [e13]). For initial events associated with a transient risk factor (e.g., postoperative immobilization), the annual rate of recurrence is 2.5%. If no risk factor is specified, the annual recurrence rate is 4.5% (5). In the absence of risk factors and provocation, and also in patients with permanent coagulopathy (e.g., factor V Leiden mutation), indefinite anticoagulation is recommended (e13). In these cases, reduction of the NOAC dosage after 6–12 months decreases the bleeding risk while keeping the risk of recurrence low (32). Antiphospholipid syndrome represents an exception here, because an accumulation of thromboembolic events occurred during treatment with rivaroxaban. Therefore, indefinite anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists is preferable in patients with a lupus anticoagulant-associated antiphospholipid syndrome or triple-positive serology (lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, and anti-beta-2-glycoprotein I antibodies) (30). If a VTE occurs after a major operation or after trauma, for example, anticoagulation for 3 months suffices (33). If long-term anticoagulation is indicated, the primary care physician should conduct annual reevaluation of the benefit/risk ratio with regard to the bleeding risk and the danger of PE recurrence, including a blood count and testing of liver and kidney function (34).

eTable 3. Risk of recurrence of VTE (modified from [34, e13]).

| Mild provoking factor | Severe provoking factor | Unprovoked PE | ||

| Transient | Persistent | Transient | Persistent | |

| Annual recurrence rate | ||||

| 4.2% | 10.7% | 1% | 20% | 10% |

| – Hospitalization/immobilization – Estrogens – Pregnancy/postpartal – Trauma of lower extremities with transient immobility – Journey >8 h |

– Chronic inflammatory bowel disease – Lower extremity paresis – Cardiac insufficiency – Obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) – Renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance < 50 ml/min) – Positive family history of VTE – Thrombophilia (confirmed by laboratory tests) |

– Major surgery – Severe trauma – Cesarean section |

– E.g., active tumor disease | – No risk/provocation factor present |

VTE, Venous thromboembolism

Emergency physician: high-risk pulmonary embolism

If the acute PE leads to hemodynamic instability (cardiac arrest, obstructive shock, persistent arterial hypertension, fall in systolic arterial pressure to >40 mm Hg), then it can be assumed that a massive arterial occlusion is present. The immediate steps to take are hemodynamic stabilization of the patient (primarily with 500 mL crystalloid intravenous fluid, noradrenaline, and, if required, dobutamine), initiation of anticoagulation, and systemic thrombolysis (strong recommendation) (5, e14). The lysis treatment greatly lowers the acute mortality in patients with high-risk PE (odds ratio [OR] 0.15 [0.03; 0.78]) (e14) and reduces overall mortality in PE patients as a whole (OR 0.53, number needed to treat [NNT] 59). Because the lysis-associated risk of severe bleeding events is very high, systemic lysis is recommended only for patients with high-risk PE and for those with moderate- to high-risk PE who develop hemodynamic instability (35, e15).

Lysis treatment is most effective in the first 48 h after onset of the embolic event. If an initially stable patient becomes unstable, however, thrombolysis can be carried out up to 14 days after symptoms are first noted. Both in high-risk PE and in the case of unsuccessful lysis, early consideration should be given to surgical thrombectomy (strong recommendation) and, in the presence of refractory hemodynamic instability, to venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO; weak recommendation) (e16). Should there be contraindications, catheter-guided procedures can be used (weak recommendation) (5). The overall mortality after surgical thrombectomy is reported in the literature as 27.2%, varying according to the hemodynamic situation beforehand (cardiac arrest: 44.4%, shock: 23.7%, no shock: 7.9%). Surgical procedures lowered mortality by 30–70% between 1960 and 2000 (e16).

Note: Pulmonary embolism in a pregnant woman

Risk of recurrence.

Randomized controlled trials have shown that NOAC are not inferior to vitamin K antagonists regarding the risk of recurrence and are associated with a significantly reduced prevalence of bleeding events (HR 0.84–1.09).

PE is one the leading causes of death in pregnant women. It is difficult to discern whether dyspnea results from a physiological adaptation process or might be a symptom associated with PE. The standard diagnostic algorithm has to be modified (efigure 2) (22) to take account of the pregnancy-associated elevation of D-dimers (e17). If the patient shows signs of DVT, investigation should begin with compression sonography. If a thrombus is detected, anticoagulation is started and no further diagnostic tests are conducted (22).

LWMH are recommended as the initial treatment, because they do not cross the placenta. Vitamin K antagonists are, formally, contraindicated only in the first trimester, but are now hardly ever used at any stage of pregnancy. NOAC are contraindicated during the entire pregnancy. Anticoagulation should be continued for a period of 6 months until after parturition (5, 22).

Note: Pulmonary embolism in cancer patients

The risk of VTE is 4–7 times higher in patients with cancer than in the normal population (36). PE is the first sign of cancer in some cases (37) and is often associated with more aggressive tumor biology (e18). In the case of low pre-test probability, it may be possible to exclude PE by D-dimer determination alone. However, most cancer patients have tumor-related elevation of D-dimers. Hitherto, LWMH have been recommended as “anticoagulants of choice” for the first 3–6 months, but new research has shown that the NOAC edoxaban and rivaroxaban are effective and safe alternatives (38, 39, e19). A recently published large randomized double-blind study showed that apixaban compared with LWMH followed by vitamin K antagonists, was beneficial in terms of efficacy (VTE recurrence or VTE-associated death: 2.3% vs. 2.7%) and safety (VTE recurrence 3.7% vs. 6.4%, severe bleeding complication 0.6% vs. 1.8%) (e16). The risk of bleeding was higher in patients with esophageal or gastric cancer (36, 38). Treatment should be continued indefinitely or until recovery from cancer (5).

Discovery of a PE should prompt tumor screening, comprising history taking, physical examination, blood tests (complete blood count, creatinine, liver function tests; if required, calcium dehydrogenase and lactate dehydrogenase), chest radiography, and age- and sex-specific cancer-detection measures (37, 40). An additional recommendation for patients under 50 years of age with an unprovoked event is coagulation testing, particularly with antiphospholipid syndrome in mind (30).

Efficacy of lysis treatment.

Lysis treatment is most effective in the first 48 h after onset of the embolic event. If an initially stable patient becomes unstable, however, thrombolysis can be carried out up to 14 days after symptoms are first noted.

If antiphospholipid syndrome is detected, the treatment of choice is vitamin K antagonists. General screening for hereditary thrombophilias is controversial, because their detection does not change the treatment regimen. This screening is recommended solely for patients with an unprovoked event and should be carried out with the patient’s consent after conclusion of the initial treatment (30).

Case report: part 5

The patient was informed in detail about her disease, its treatment, and the associated adverse effects and was instructed to visit her primary care physician within a week as well as consulting a gynecologist in the near future. Thrombophilia screening is not urgently indicated in this case, but can be carried out if the patient so wishes.

Pulmonary embolism.

PE is one the leading causes of death in pregnant women. It is difficult to discern whether dyspnea results from a physiological adaptation process or might be a symptom associated with PE.

Procedure following a VTE.

Discovery of a PE should prompt tumor screening, comprising history taking, physical examination, blood tests, chest radiography, and age- and sex-specific cancer-detection measures.

Further information on CME.

-

Participation in the CME certification program is possible only via the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de.

This unit can be accessed until 16 September 2022. Submissions by letter, e-mail, or fax cannot be considered.

The completion time for all newly started CME units is 12 months. The results can be accessed 4 weeks following the start of the CME unit. Please note the respective submission deadline at: cme.aerzteblatt.de.

-

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Continuing Medical Education. CME points can be managed using the ““uniform CME number”” (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN).

The EFN must be stated during registration on www.aerzteblatt.de (““Mein DÄ””) or entered in ““Meine Daten,”” and consent must be given for results to be communicated. The 15-digit EFN can be found on the CME card (8027XXXXXXXXXXX).

CME credit for this unit can be obtained via cme.aerzteblatt.de until 16 September 2022. Only one answer is possible per question. Please choose the most appropriate answer.

Question 1

How high is the incidence of pulmonary embolism in patients over 80 years of age compared with 40- to 50-year-olds?

Twofold

Fourfold

Sixfold

Eightfold

Tenfold

Question 2

The pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) were developed to exclude pulmonary embolism without the need for supplementary technical diagnostic procedures in patients with low pre-test probability (e.g., in the primary care setting). According to the PERC, which of the following criteria would speak against continued out-of-hospital care of a hemodynamically stable patient without further diagnostic work-up?

Age 49 years

SpO2 95% and HF 90/min

Total knee replacement 3 weeks ago

No history of thrombosis or PE

Bilateral low-grade varicosis of the lower leg

Question 3

Which of the following correction factors should be applied when interpreting the D-dimer concentration in patients over 50 years of age?

Age in years × 5 ng/mL

If BMI > 30 kg/m2: plus 500 ng/mL

Age in years/BMI plus 400 ng/mL

Age in years × 10 ng/mL

If BMI > 40 kg/m2: plus 500 ng/mL

Question 4

According to the criteria of the YEARS algorithm, in which of the following situations should computed tomography pulmonary angiography be carried out?

None of the YEARS criteria satisfied, D-dimer concentration >1 000 ng/mL

Two of the YEARS criteria satisfied, D-dimer concentration <500 ng/mL

None of the YEARS criteria satisfied, D-dimer concentration <1000 ng/mL

Three of the YEARS criteria satisfied, D-dimer concentration <500 ng/mL

None of the YEARS criteria satisfied, D-dimer concentration >500 ng/mL

Question 5

A hemodynamically unstable patient (heart rate 145/min, blood pressure 75/50mm Hg) is brought to the emergency room by ambulance with suspected pulmonary embolism. Which of the following applies?

f echocardiography shows signs of acute right ventricular overload, a 12-lead ECG must be performed before systemic thrombolysis.

Cardiac catheterization should be performed to exclude potentially relevant coronary heart disease, with optional insertion of a left ventricular support system in the presence of obstructive shock.

The patient should initially undergo hemodynamic stabilization by means of a kidney-adapted dose of dopamine and administration of crystalloid fluid.

Following hemodynamic stabilization with volume replacement, the patient should be treated on a normal ward.

Even in a patient with confirmed pulmonary embolism, no lysis treatment should be conducted if there is a history of craniocerebral trauma during the previous 3 months.

Question 6

A 40-year-old man comes to the emergency room with a 2-day history of worsening dyspnea and right-sided thoracic pain on inspiration. Physical examination reveals no abnormalities. Investigation of vital signs reveals tachycardia (118/min), while the blood pressure is in the lower part of the normal range (105/65 mm Hg). Three weeks earlier, the patient was involved in a road traffic accident and hospitalized for 10 days for spinal stabilization. The D-dimer level at presentation is 830 ng/mL. What treatment would you recommend? On what criteria?

According to the criteria of the PERC algorithm, the patient can be discharged and any further diagnostic work-up or treatment can take place outside the hospital setting.

The tachycardia and hypotension necessitate initiation of systemic lysis treatment and urgent continuation of the diagnostic work-up.

In the event of high pre-test probability of the presence of pulmonary embolism, therapeutic anticoagulation, e.g., with low-molecular-weight heparin, should take place before proceeding to further diagnostic work-up and diagnostic CTPA should be carried out.

According to the YEARS algorithm, a D-dimer level <1000 ng/mL means that PE can be ruled out without any further diagnostic tests. The patient can be discharged to out-of-hospital care.

In this situation the age-adapted YEARS algorithm is used in a 40-year-old patient. Because the measured D-dimer level of 820 ng/mL exceeds the age-adjusted cut-off of 600 ng/mL (1000 ng/mL - [40 years × 10]), supplementary diagnostic imaging should be ordered.

Question 7

In which of the following situations can a primary care physician tell the patient that no further treatment is required?

None of the HESTIA criteria is satisfied and the residual right ventricular overload is only moderate.

The sPESI is ≤ 1 and good compliance on the part of the patient can be anticipated.

None of the HESTIA criteria is satisfied and hypertension not exceeding 150/100 mm Hg was diagnosed.

No exacerbation of the patient’s existing COPD is to be anticipated and fulfillment of one HESTIA criterion was demonstrated.

None of the HESTIA criteria is satisfied and the sPESI is ≥ 1.

Question 8

How long should anticoagulation be continued after occurrence of a deep vein thrombosis in a patient with no elevated risk of bleeding?

One month

Two months

Three months

Four months

Five months

Question 9

What should be carried out before computed tomography pulmonary angiography in a hemodynamically stable patient with strong suspicion of a pulmonary embolism?

Initiation of anticoagulation

Troponin determination

Determination of the Simplified Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (sPESI)

Exclusion of right ventricular dysfunction

Stress echocardiography

Question 10

What is used as the initial anticoagulant medication in a woman in the first trimester of pregnancy who has a pulmonary embolism?

Edoxaban

Rivaroxaban

Phenprocoumon

Vitamin K antagonists

Low-molecular-weight heparins

►Participation is possible only via the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de

eBOX 2. Risk factors for occurrence of pulmonary embolism (5).

Certain risk factors increase the probability of the presence of a pulmonary embolism. Persisting risk factors are also relevant for the treatment regimen, in that they necessitate permanent anticoagulation.

-

Severe risk factors (OR > 10)

Fractures of the lower extremity

Hospitalization within the previous 3 months due to cardiac failure/atrial fibrillation

Knee or hip joint replacement

Myocardial infarction (within the previous 3 months)

History of venous thromboembolism

Spinal column injury

-

Moderate risk factors (OR 2–9)

Surgery in the region of the knee

Autoimmune diseases

Indwelling (central) venous catheter

Cardiac insufficiency, respiratory insufficiency

Chemotherapy

Hormone replacement therapy

Oral contraceptive treatment

Postpartal period

Infections (pneumonia, HIV, urinary tract infection)

Cancer

Thrombophilia

Stroke

-

Slight risk factors (OR < 2)

Bed rest> 3 days

Diabetes mellitus

Arterial hypertension

Long flight or road trip

Advanced age

Laparoscopy

Obesity

Pregnancy

Primary varicosis

OR, Odds ratio

Acknowledgments

Received on 31 December 2020, revised version accepted on 28 April 2021

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Agarwal S, Clark D, Sud K, Jaber WA, Cho L, Menon V. Gender disparities in outcomes and resource utilization for acute pulmonary embolism hospitalizations in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:1270–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keller K, Hobohm L, Ebner M, et al. Trends in thrombolytic treatment and outcomes of acute pulmonary embolism in Germany. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:522–529. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wendelboe AM, Raskob GE. Global burden of thrombosis: epidemiologic aspects. Circ Res. 2016;118:1340–1347. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engbers MJ, van Hylckama Vlieg A, Rosendaal FR. Venous thrombosis in the elderly: incidence, risk factors and risk groups. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2105–2112. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS) Eur Heart J. 2020;41:543–603. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marshall PS, Mathews KS, Siegel MD. Diagnosis and management of life-threatening pulmonary embolism. J Intensive Care Med. 2011;26:275–294. doi: 10.1177/0885066610392658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berliner D, Schneider N, Welte T, Bauersachs J. The differential diagnosis of dyspnoea. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:834–845. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollack CV, Schreiber D, Goldhaber SZ, et al. Clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes of patients diagnosed with acute pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: initial report of EMPEROR (Multicenter Emergency Medicine Pulmonary Embolism in the Real World Registry) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:700–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Pol LM, Dronkers CEA, van der Hulle T, et al. The YEARS algorithm for suspected pulmonary embolism: shorter visit time and reduced costs at the emergency department. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16:725–733. doi: 10.1111/jth.13972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Derivation of a simple clinical model to categorize patients probability of pulmonary embolism: increasing the models utility with the SimpliRED D-dimer. Thromb Haemost. 2000;83:416–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers MA, Levine DA, Blumberg N, Flanders SA, Chopra V, Langa KM. Triggers of hospitalization for venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2012;125:2092–2099. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.084467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson FA. Jr, Spencer FA. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107:I9–l16. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078469.07362.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott CG, Goldhaber SZ, Visani L, DeRosa M. Chest radiographs in acute pulmonary embolism. Results from the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry. Chest. 2000;118:33–38. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodger MA, Carrier M, Jones GN, et al. Diagnostic value of arterial blood gas measurement in suspected pulmonary embolism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:2105–2108. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.2004204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodger M, Makropoulos D, Turek M, et al. Diagnostic value of the electrocardiogram in suspected pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:807–809. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01090-0. A10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shopp JD, Stewart LK, Emmett TW, Kline JA. Findings from 12-lead electrocardiography that predict circulatory shock from pulmonary embolism: systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22:1127–1137. doi: 10.1111/acem.12769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Righini M, Le Gal G, De Lucia S, et al. Clinical usefulness of D-dimer testing in cancer patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:715–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crawford F, Andras A, Welch K, Sheares K, Keeling D, Chappell FM. D-dimer test for excluding the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010864.pub2. CD010864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Righini M, Van Es J, Den Exter PL, et al. Age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff levels to rule out pulmonary embolism: the ADJUST-PE study. Jama. 2014;311:1117–1124. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Pooter N, Brionne-François M, Smahi M, Abecassis L, Toulon P. Age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off levels to rule-out venous thromboembolism in patients with non-high pre-test probability. Clinical performance and cost-effectiveness analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19:1271–1282. doi: 10.1111/jth.15278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Hulle T, Cheung WY, Kooij S, et al. Simplified diagnostic management of suspected pulmonary embolism (the YEARS study): a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet. 2017;390:289–297. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30885-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Pol LM, Tromeur C, Bistervels IM, et al. Pregnancy-adapted YEARS algorithm for diagnosis of suspected pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1139–1149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penaloza A, Soulie C, Moumneh T, et al. Pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) rule in European patients with low implicit clinical probability (PERCEPIC): a multicentre, prospective, observational study. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4:e615–e621. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel S, Kazerooni EA, Cascade PN. Pulmonary embolism: optimization of small pulmonary artery visualization at multi-detector row CT. Radiology. 2003;227:455–460. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2272011139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bundesministerium für Gesundheit und Frauen. Schwangerschaft und Röntgenuntersuchungen. www.strahlenschutz.org/web/images/docs/2017/Schwangerschaft_und_Roentgenuntersuchungen.pdf (last accessed on 1 July 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Da CostaRodrigues J, Alzuphar S, Combescure C, Le Gal G, Perrier A. Diagnostic characteristics of lower limb venous compression ultrasonography in suspected pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14:1765–1772. doi: 10.1111/jth.13407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zondag W, Mos IC, Creemers-Schild D, et al. Outpatient treatment in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: the Hestia Study. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1500–1507. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barco S, Mahmoudpour SH, Planquette B, Sanchez O, Konstantinides SV, Meyer G. Prognostic value of right ventricular dysfunction or elevated cardiac biomarkers in patients with low-risk pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:902–910. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez Licha CR, McCurdy CM, Maldonado SM, Lee LS. Current management of acute pulmonary embolism. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;26:65–71. doi: 10.5761/atcs.ra.19-00158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duffett L, Castellucci LA, Forgie MA. Pulmonary embolism: update on management and controversies. BMJ. 2020;370 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2177. m2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazzolai L, Aboyans V, Ageno W, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute deep vein thrombosis: a joint consensus document from the European Society of Cardiology working groups of aorta and peripheral vascular diseases and pulmonary circulation and right ventricular function. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:4208–4218. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vasanthamohan L, Boonyawat K, Chai-Adisaksopha C, Crowther M. Reduced-dose direct oral anticoagulants in the extended treatment of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16:1288–1295. doi: 10.1111/jth.14156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2016;149:315–352. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kearon C, Akl EA. Duration of anticoagulant therapy for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Blood. 2014;123:1794–1801. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-512681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyer G, Vicaut E, Danays T, et al. Fibrinolysis for patients with intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1402–1411. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beyer-Westendorf J, Klamroth R, Kreher S, Langer F, Matzdorff A, Riess H. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOAC) as an alternative treatment option in tumor-related venous thromboembolism. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116:31–38. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carrier M, Lazo-Langner A, Shivakumar S, et al. Screening for occult cancer in unprovoked venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:697–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young AM, Marshall A, Thirlwall J, et al. Comparison of an oral factor Xa inhibitor with low molecular weight heparin in patients with cancer with venous thromboembolism: results of a randomized trial (SELECT-D) J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2017–2023. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.8034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raskob GE, van Es N, Verhamme P, et al. Edoxaban for the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:615–624. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1711948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Es N, Le Gal G, Otten HM, et al. Screening for occult cancer in patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:410–417. doi: 10.7326/M17-0868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Raskob GE, Angchaisuksiri P, Blanco AN, et al. Thrombosis: a major contributor to global disease burden. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:2363–2371. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Heit JA. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12:464–474. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Cohen AT, Agnelli G, Anderson FA, et al. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) in Europe. The number of VTE events and associated morbidity and mortality. Thromb Haemost. 2007;98:756–764. doi: 10.1160/TH07-03-0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Mockel M, Searle J, Muller R, et al. Chief complaints in medical emergencies: do they relate to underlying disease and outcome? The Charité Emergency Medicine Study (CHARITEM). Eur J Emerg Med. 2013;20:103–108. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328351e609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Banks E, Joshy G, Korda RJ, et al. Tobacco smoking and risk of 36 cardiovascular disease subtypes: fatal and non-fatal outcomes in a large prospective Australian study. BMC medicine. 2019;17 doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1351-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Boey E, Teo SG, Poh KK. Electrocardiographic findings in pulmonary embolism. Singapore Med J. 2015;56:533–537. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2015147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Freund Y, Cachanado M, Aubry A, et al. Effect of the pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria on subsequent thromboembolic events among low-risk emergency department patients: The PROPER randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2018;319:559–566. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.van Hylckama Vlieg A, Middeldorp S. Hormone therapies and venous thromboembolism: where are we now? J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:257–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Weill A, Dalichampt M, Raguideau F, et al. Low dose oestrogen combined oral contraception and risk of pulmonary embolism, stroke, and myocardial infarction in five million French women: cohort study. BMJ. 2016;353 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2002. i2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Reid JH, Coche EE, Inoue T, et al. Is the lung scan alive and well? Facts and controversies in defining the role of lung scintigraphy for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism in the era of MDCT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:505–521. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-1014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Vinson DR, Aujesky D, Geersing GJ, Roy PM. Comprehensive outpatient management of low-risk pulmonary embolism: can primary care do this? A narrative review. Perm J. 2020;24 doi: 10.7812/TPP/19.163. 19.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Coutance G, Cauderlier E, Ehtisham J, Hamon M, Hamon M. The prognostic value of markers of right ventricular dysfunction in pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2011;15 doi: 10.1186/cc10119. R103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Prins MH, Lensing AWA, Prandoni P, et al. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism according to baseline risk factor profiles. Blood Adv. 2018;2:788–796. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018017160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Marti C, John G, Konstantinides S, et al. Systemic thrombolytic therapy for acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:605–614. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Chatterjee S, Chakraborty A, Weinberg I, et al. Thrombolysis for pulmonary embolism and risk of all-cause mortality, major bleeding, and intracranial hemorrhage: a meta-analysis. Jama. 2014;311:2414–2421. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: results from the AMPLIFY trial. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:2187–2191. doi: 10.1111/jth.13153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Murphy N, Broadhurst DI, Khashan AS, Gilligan O, Kenny LC, O‘Donoghue K. Gestation-specific D-dimer reference ranges: a cross-sectional study. BJOG. 2015;122:395–400. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Ma L, Wen Z. Risk factors and prognosis of pulmonary embolism in patients with lung cancer. Medicine. 2017;96 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006638. e6638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Khorana AA, Noble S, Lee AYY, et al. Role of direct oral anticoagulants in the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16:1891–1894. doi: 10.1111/jth.14219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]