Abstract

It has been shown previously that some immortalized human cells maintain their telomeres in the absence of significant levels of telomerase activity by a mechanism referred to as alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT). Cells utilizing ALT have telomeres of very heterogeneous length, ranging from very short to very long. Here we report the effect of telomerase expression in the ALT cell line GM847. Expression of exogenous hTERT in GM847 (GM847/hTERT) cells resulted in lengthening of the shortest telomeres; this is the first evidence that expression of hTERT in ALT cells can induce telomerase that is active at the telomere. However, rapid fluctuation in telomere length still occurred in the GM847/hTERT cells after more than 100 population doublings. Very long telomeres and ALT-associated promyelocytic leukemia (PML) bodies continued to be generated, indicating that telomerase activity induced by exogenous hTERT did not abolish the ALT mechanism. In contrast, when the GM847 cell line was fused with two different telomerase-positive tumor cell lines, the ALT phenotype was repressed in each case. These hybrid cells were telomerase positive, and the telomeres decreased in length, very rapidly at first and then at the rate seen in telomerase-negative normal cells. Additionally, ALT-associated PML bodies disappeared. After the telomeres had shortened sufficiently, they were maintained at a stable length by telomerase. Together these data indicate that the telomerase-positive cells contain a factor that represses the ALT mechanism but that this factor is unlikely to be telomerase. Further, the transfection data indicate that ALT and telomerase can coexist in the same cells.

Telomeres are specialized structures consisting, in human cells, of TTAGGG repeat sequences (4, 33) which, together with specific binding proteins (5), form caps at the ends of chromosomes that are essential for chromosome stability (11, 17). Telomeres shorten with each round of cell division (1, 2, 18, 21, 28, 34) due, at least in part, to the “end replication problem” (26, 44). It is hypothesized that critically shortened telomeres can trigger growth arrest and senescence (19) and that this is a key factor in cellular aging and control of cell division potential (reviewed in reference 36). There may be additional factors, however, that also act as a mitotic clock and cause a permanent exit from the cell cycle (37). All immortalized human cell lines and most tumors that have been studied to date have an active telomere maintenance mechanism, which strongly suggests that prevention of telomere shortening is necessary for the unlimited proliferative potential of these cells (9).

The telomere maintenance mechanism in most immortalized cells and tumor cells utilizes the ribonucleoprotein enzyme telomerase, which compensates for sequential telomere shortening at each cell division by catalyzing the addition of repeat sequences (15). Telomerase is either absent or present at low levels in most normal human somatic cells (3, 24). Previous studies, however, have shown that a number of in vitro immortalized human cell lines (8), tumor-derived cell lines, and tumors (6) maintain their telomeres in the absence of detectable telomerase activity by one or more mechanisms, referred to as alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) (9). Telomere lengths in cells utilizing ALT range in size from almost undetectable to greater than 50 kb; this phenotype is not present in these cells prior to immortalization (8). Recently it has been shown that ALT involves telomere-telomere recombination (14).

In this study we demonstrate that induction of telomerase activity in the ALT cell line GM847, by expression of the telomerase catalytic subunit hTERT, significantly lengthens the shortest telomeres. This is the first report demonstrating such an effect by exogenous expression of hTERT in ALT cells and suggests that sufficient levels of other components of the telomerase complex required for telomere lengthening are present in these cells. Very long heterogeneous telomeres and other hallmarks of ALT are still present in these cells, suggesting that ALT is not repressed by and is able to coexist with telomerase. To determine the effect of endogenous telomerase on GM847 telomeres, we analyzed telomerase-positive somatic cell hybrids generated by fusion of GM847 with the telomerase-positive cell lines HT-1080 and T24. Previously it was reported that there was continuing telomere shortening in these hybrid cells despite the presence of telomerase activity and that ALT was repressed (35). We now show that the telomeres in the hybrids eventually reach a stable length and undergo no further shortening at later population doublings (PDs). The data from the hTERT transfection experiments indicate that telomerase is unlikely to cause the complete repression of ALT that was seen in the somatic cell hybrids. In addition, telomerase did not prevent shortening of long telomeres in the hybrid cells. These findings have implications for our understanding of how telomere maintenance mechanisms are controlled in human cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid expression vectors.

A cDNA insert encoding the human telomerase catalytic subunit hTERT (23) was subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pCIneo (Promega, Madison, Wis.). The construct was verified by DNA sequence analysis. A pIRESneo construct (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) containing a dominant-negative hTERT insert (3-1) was kindly provided by Murray O. Robinson, Amgen Corporation, and has been described previously (20).

Transfection of GM847 cells with plasmid vectors.

GM847DM cells were seeded at a density of 106 cells/10-cm dish and incubated overnight. Cells were transfected the following day with 5 μg of plasmid DNA using 30 μl of Fugene-6 transfection reagent (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and 1 ml of OPTI-MEM reduced serum medium (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.) for 2 h at 37°C, after which time Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium plus 10% fetal bovine serum was added. Cells were harvested 18 to 24 h later with trypsin-EDTA and seeded at a concentration of 104 cells/10-cm dish in medium containing 300 μg of Geneticin (G418 sulfate; Roche) per ml. Individual colonies were isolated after 2 weeks of selection, using 4-mm sterile, trypsin-soaked filter paper discs, and then were passaged continuously in medium containing Geneticin.

Cell culture and photomicrography.

All cells used in this study were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 50 μg of gentamicin per ml and placed at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. Cells were photographed at a magnification of ×15 on a phase-contrast microscope.

TRAP assay.

Cell lysates were prepared using the 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) detergent lysis method, and 2 μg of total protein was used in each assay. The protein concentration of lysates was measured using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay kit (Hercules, Calif.). The PCR-based telomere repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) assay for telomerase activity was performed essentially as described earlier (24). Amplification products were separated on a 10% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel, stained with SYBR-green I (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) and visualized using a Storm 860 imager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.). A 150-bp rat myogenin cDNA fragment containing TRAP primer flanking sequences was added to a number of reactions as a PCR internal control and has been previously described (46). The intensity of this internal control band is inversely proportional to the level of telomerase activity.

Terminal restriction fragment (TRF) analysis.

Genomic DNA was prepared from the parental and hybrid cultures, and 40 μg was digested with restriction enzymes HinfI and RsaI, which cut throughout the genome but not within telomeres. Quantitated samples (1 μg) were loaded onto a 1% agarose gel in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer and separated using a CHEF-DR II pulsed-field electrophoresis apparatus (Bio-Rad) in recirculating 0.5× TBE buffer at 14°C with a ramped pulse speed of 1 to 6 s at 200 V for 14 h. The gels were dried, denatured, hybridized to a [γ-32P]dATP 5′-end labeled telomeric oligonucleotide probe, (TTAGGG)3, and exposed to Kodak XAR film at −80°C for 18 h.

FISH analysis and immunocytochemistry.

Chromosome preparations from colcemid (Roche)-arrested cells were obtained according to standard cytogenetic methods. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with a Cy3-conjugated telomere-specific peptide-nucleic acid probe (PE Biosystems, Framingham, Mass.) was essentially performed according to the guidelines of Lansdorp et al. (25).

Briefly, slides were treated with RNase A (100 μg/ml in 2× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate]) at 37°C for 60 min, rinsed in 2× SSC, equilibrated in 10 mM HCl (pH 2.0), and digested with pepsin (0.01% [wt/vol] in 10 mM HCl) at 37°C for 10 min. This was followed by three washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and postfixation in 1% formaldehyde–PBS for 10 min at 25°C. Dehydrated slides were denatured and probed with Cy3-conjugated (C3TA2)3 peptide-nucleic acid (0.6 μg/ml in 70% formamide, 1% blocking reagent [Roche], and 10 mM Tris, pH 7.2) at 80°C for 3 min on a heating block, followed by hybridization at 25°C for 2 h. After hybridization, slides were washed at 25°C with 70% formamide–10 mM Tris (pH 7.2) and 0.05 M Tris–0.15 M NaCl (pH 7.5) containing 0.05% Tween 20. Slides were counterstained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (0.6 μg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and mounted with antifade-mounting medium (2.33% [wt/vol] DABCO [Sigma] in 90% glycerol–20 mM Tris, pH 8.0). Metaphases were evaluated on a Leica DMLB fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets, and DAPI and Cy3 images were captured on a cooled CCD camera (SPOT2; Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, Mich.), merged, and further processed for illustrative purposes with Adobe Photoshop 6.0.

Quantitative histogram analysis of fluorescence intensities was performed with ImagePro Plus 4.0 software (MediaCybernetics, Silver Spring, Md.) on 24-bit RGB images captured with exposure times of 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 s with no gamma adjustment. Image bitmap pixel values ranged from 0 (black) to 255 (full scale) following a linear function of a measured intensity with increasing exposure time. Typically, four intensity values were recorded for the maximum intensities of the short (p) and the long (q) arm of the Y chromosome with the four different exposure times. The ratio of p arm intensity to q arm intensity was plotted as a bar chart on a logarithmic scale.

ALT-associated promyelocytic leukemia (PML) bodies (APBs) (47) were detected and visualized either by telomere FISH to interphase nuclei or by immunostaining methanol-fixed cells on chamber slides with a mouse monoclonal hTRF2 antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, N.Y.) for 60 min at 25°C followed by a rabbit anti-mouse fluorescein isothiocyanate secondary antibody for 30 min. Images were captured as described above.

Somatic cell hybridization.

A universal hybridizer ALT cell line, GM847DM (double mutant, simian virus 40 [SV40]-immortalized human fibroblasts), was obtained from O. Pereira-Smith, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex. HT-1080 (fibrosarcoma) and T24 (bladder carcinoma) telomerase-positive cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.). Cell fusion was performed as previously described (35).

Estimation of telomere shortening rate.

TRF gel lanes were scanned by a computing densitometer (Molecular Dynamics). Discrete telomere band sizes were calculated by plotting the relative position on a linear curve generated by regression analysis of molecular weight marker positions. Rates of shortening were calculated by reduction in band sizes over specific PD ranges.

RESULTS

Exogenous expression of telomerase in GM847 cells lengthens the shortest telomeres.

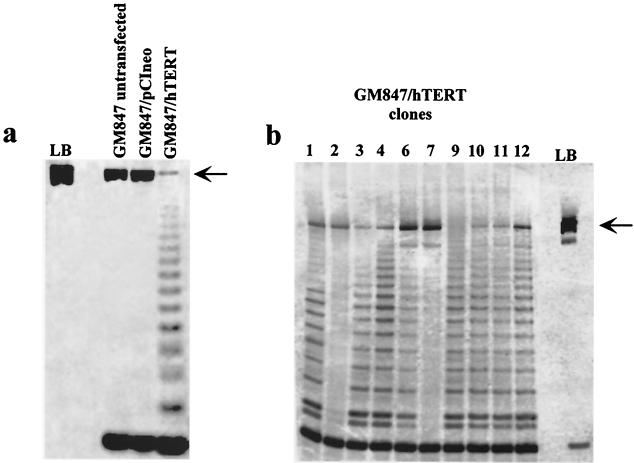

We transiently expressed the telomerase catalytic subunit hTERT in the ALT cell line GM847 and found, using TRAP, that this reconstituted telomerase activity which was absent in vector control and untransfected cells (Fig. 1a). This finding was consistent with other reports showing activation of telomerase in GM847 cells by both transient (45) and stable (13) transfection of hTERT alone. To assess the impact of exogenous telomerase activity upon ALT, we generated 10 stable clones of GM847 cells by transfection of hTERT (GM847/hTERT) and found 8 out of 10 to be telomerase positive (Fig. 1b). The GM847/hTERT stable clones and vector control clones were analyzed, at the earliest time points possible, by TRF to measure telomere lengths. Telomere lengths of each clone, however, appeared heterogeneous and characteristic of ALT whether or not telomerase activity was detectable (data not shown). Thus, by TRF analysis the ALT telomere phenotype appeared to be unaffected by exogenous telomerase activity in GM847 cells.

FIG. 1.

TRAP analysis of GM847 cells containing both transient and stable expression of hTERT. An internal control (rat myogenin) for the PCR is indicated by an arrow. LB, lysis buffer negative control. (a) Transient transfection of exogenous hTERT into GM847 cells (GM847/hTERT) is compared to untransfected GM847 or pCIneo vector controls. (b) Stable clones of GM847 transfected with hTERT.

Twelve subclones were generated by limiting dilution of two telomerase-positive clones at late passage, GM847/hTERT-3 (PD 115) and GM847/hTERT-6 (PD 143). TRAP analysis showed that all of the subclones were telomerase positive (data not shown). The telomere lengths of GM847/hTERT-3 and -6 clones and their subclones were then compared with those of untransfected GM847 cells by telomere FISH with a fluorochrome-labeled telomere probe (Fig. 2). GM847 cells show heterogeneous telomere FISH signals ranging from undetectable to very large (Fig. 2a), and this pattern was apparent in 50 out of 50 metaphase spreads (Table 1). There were similar numbers of undetectable telomeres present in each of the nuclei examined amounting to approximately 6% of the total (Table 1). This telomere FISH pattern is consistent with the telomere length heterogeneity in GM847 cells documented by TRF analysis (8, 35).

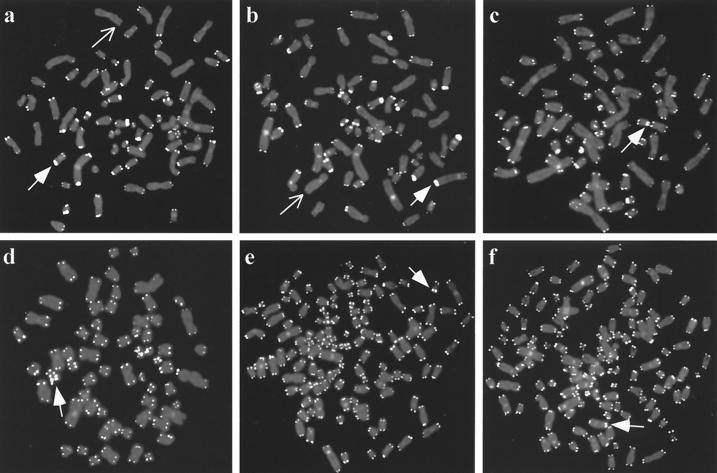

FIG. 2.

Telomere length analysis by FISH on individual metaphase chromosomes using a peptide-nucleic acid telomere probe. Examples of very intense telomere signals (corresponding to very long telomeres) are indicated by arrows with filled heads and chromosome ends with undetectable or almost undetectable telomere signals are indicated by arrows. (a) Untransfected GM847 cells showing widely varying signal intensities indicative of ALT telomere length heterogeneity. (b) A metaphase from the GM847/hTERT-3 parental mass culture that has ALT-like heterogeneous telomere lengths. (c and d) GM847/hTERT-3 parental cell metaphases showing a detectable FISH signal at each chromosome. GM847/hTERT-3 subclone 9 (e) and GM847/hTERT-6 subclone 11 (f) also show detectable FISH signals at each chromosome end.

TABLE 1.

Telomere FISH analyses of GM847 and GM847/hTERT cells

| Cell type | Metaphases with at least one undetectable telomere (%)a | No. of undetectable telomeres (%)b |

|---|---|---|

| GM847 untransfected | 50/50 (100) | 41/704 (6) |

| GM847/hTERT-3 (PD 42) | 12/50 (24) | |

| GM847/hTERT-3 (PD 106) | 9/50 (18) | 8/690 (1) |

| GM847/hTERT-3 (PD 138) | 13/50 (26) | |

| GM847/hTERT-6 (PD 46) | 13/55 (23) | |

| GM847/hTERT-6 (PD 82) | 15/50 (30) | 1/894 (0.1) |

| GM847/hTERT-6 (PD 150) | 13/52 (25) | |

| GM847/hTERT-3 subclone 9 | 1/50 (2) | 2/1,232 (0.2) |

| GM847/hTERT-6 subclone 11 | 0/50 (0) | 2/1,210 (0.2) |

Metaphases were scored as containing at least one chromosome end without a detectable telomere FISH signal.

Number of undetectable telomeres relative to the total number of chromosome ends analyzed by scoring every chromosome end in five additional (i.e., different) metaphases.

Analysis of GM847/hTERT-3 cells, however, revealed detectable telomere FISH signals at almost every chromosome end (Fig. 2c and d) in the majority of nuclei at both early and late passage. This suggested that the shortest telomeres had been lengthened in the majority of cells within the population. Chromosome ends without a detectable telomere FISH signal were present in only 12 out of 50 GM847/hTERT-3 metaphase nuclei at an early passage and 13 out of 50 nuclei at a later passage (Table 1). Approximately one quarter of the GM847/hTERT-3 metaphases examined, therefore, still had the very heterogeneous telomere FISH signals characteristic of untransfected GM847 cells (Fig. 2b), and this subpopulation persisted with passage in culture (Table 1). Although no telomerase-negative subclones of GM847/hTERT-3 were detected, it is possible that hTERT expression had been downregulated in a proportion of cells and this resulted in retention of, or reversion to, a characteristic ALT telomere phenotype.

Similar results were obtained for the GM847/hTERT-6 clone, in which most of the short telomeres had also been lengthened. Approximately one quarter (23 to 30%) of the GM847/hTERT-6 clone cells contained a subpopulation of cells with at least one undetectable telomere signal (Table 1). However, it is likely that even in this subpopulation some of the very short telomeres had been lengthened by telomerase activity, because the number of undetectable telomeres was reduced by much more than one quarter compared to that of the untransfected GM847 cells. It is noteworthy that some very large signals were still evident in nuclei that had no undetectable telomere signals (Fig. 2). This indicated that although the number of very short telomeres was reduced in these clones, very long telomeres were still present.

FISH analysis of GM847/hTERT-3 subclone 9 (Fig. 2e) and GM847/hTERT-6 subclone 11 (Fig. 2f) revealed detectable telomeric signals on every chromosome examined in 49 out of 50 and 50 out of 50 metaphases, respectively (Table 1). It is interesting that although cells with undetectable telomeres were present within the GM847/hTERT-3 and -6 populations and persisted at later passages, this phenotype was very rare in the GM847/hTERT-3 and -6 subclones. A reason for this outcome may be that cells within the GM847/hTERT populations that have lengthened the shortest telomeres might have a selective growth advantage during cloning by limiting dilution.

These FISH data therefore show that the shortest telomeres have been lengthened in most of the GM847 cells that express exogenous hTERT. The effect was most noticeable after subcloning, and this may have been due to the additional population doublings that the cells undergo during the subcloning process, during which time telomere lengthening by telomerase would have progressed. Every metaphase of untransfected GM847 cells that was examined, without exception, had several chromosome ends with an undetectable telomere FISH signal (Table 1). This indicates that the lengthening of the short telomeres seen in GM847/hTERT cells is due to telomerase rather than random selection of putative preexisting cells within the untransfected GM847 population that happened to have no short telomeres. The data were confirmed by FISH examination of additional GM847/hTERT clones, which showed in five of five clones that the shortest telomeres had clearly been lengthened; this phenotype was detected in zero of five GM847 untransfected subclones and in zero of two vector control clones (data not shown).

The ALT mechanism remains active in GM847/hTERT cells.

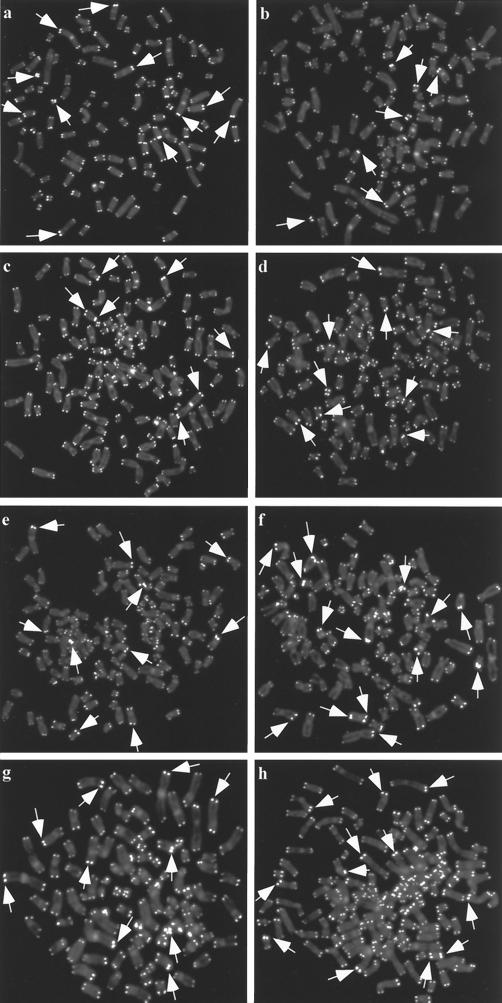

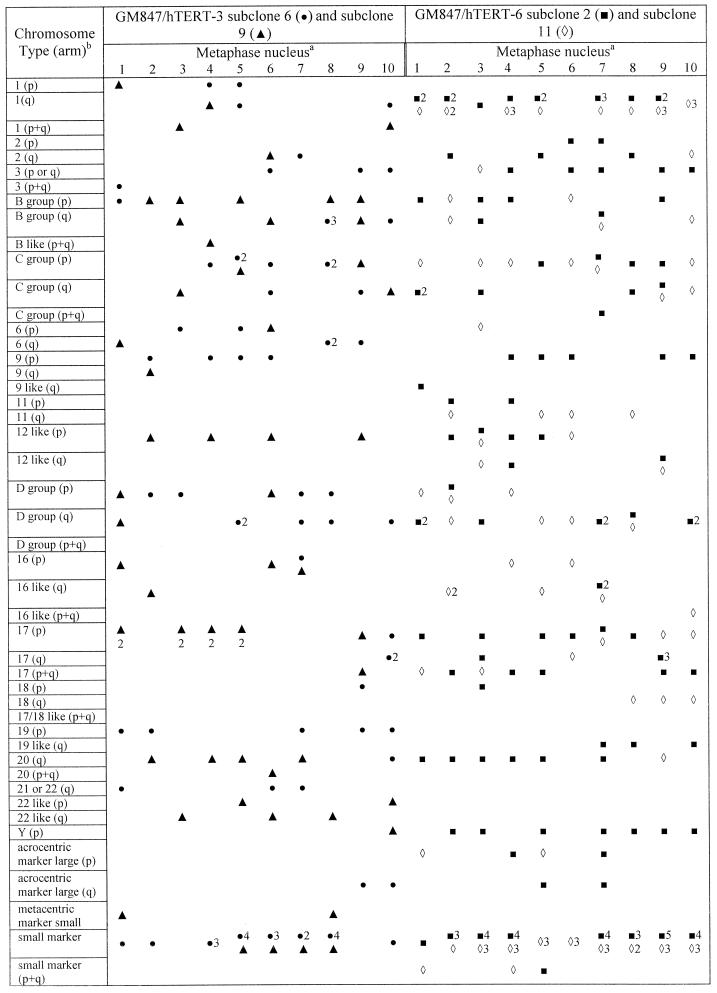

FISH analysis of early- and late-passage GM847/hTERT-3 and GM847/hTERT-6 cells and subclones derived from them showed that these cells retained the very large telomere FISH signals characteristic of ALT cells (Fig. 2). This suggested that ALT was still active in these cells, but to confirm that this was the case, additional telomere FISH analyses were performed on GM847/hTERT-3 subclones 6 and 9 and GM847/hTERT-6 subclones 2 and 11 that had been obtained by limiting dilution at late-passage levels (PD 115 and PD 143, respectively). Very large FISH signals corresponding to long telomeres were detectable in every metaphase examined (Fig. 3), indicating that ALT telomere maintenance was still operating in these cells. Further cytogenetic analysis of metaphase nuclei within each subclone revealed a striking heterogeneity in the chromosomal location of the long telomeres (Fig. 4). This pattern was also seen in untransfected GM847 cells but not in telomerase-positive cells (data not shown). This is consistent with previous data indicating that GM847 cells maintain their telomeres by telomere-telomere recombination and copy switching (14). As the subclones were derived from single cells, this heterogeneity must have been generated subsequent to subcloning, indicating that ALT was still active for more than 115 or 143 PD (in GM847/hTERT-3 or GM847/hTERT-6 cells, respectively) after initial transfection with hTERT.

FIG. 3.

Telomere FISH analysis, using a peptide-nucleic acid telomere probe, on individual metaphase nuclei from subclones of GM847/hTERT-3 and GM847/hTERT-6 (all at PD 25 after subcloning of late-passage cells). Examples of very intense telomere signals (corresponding to very long telomeres) are indicated by arrows. Representative images are shown. (a and b) GM847/hTERT-3 subclone 6; (c and d) GM847/hTERT-3 subclone 9; (e and f) GM847/hTERT-6 subclone 2; (g and h) GM847/hTERT-6 subclone 11.

FIG. 4.

Detection of long telomeres on specific chromosomes in metaphase spreads of GM847/hTERT subclones. Footnote a, ten metaphase nuclei were examined for each subclone. Numbers represent the number of instances of long telomeres on the same chromosome within a single metaphase. Footnote b, chromosomes that could not be identified exactly were assigned to groups based on their size and arm index. Group number (chromosomes): A (1 through 3); B (4 and 5); C (6 through 12, X); D (13 through 15); E (16 through 18); F (19 and 20); G (21, 22, Y).

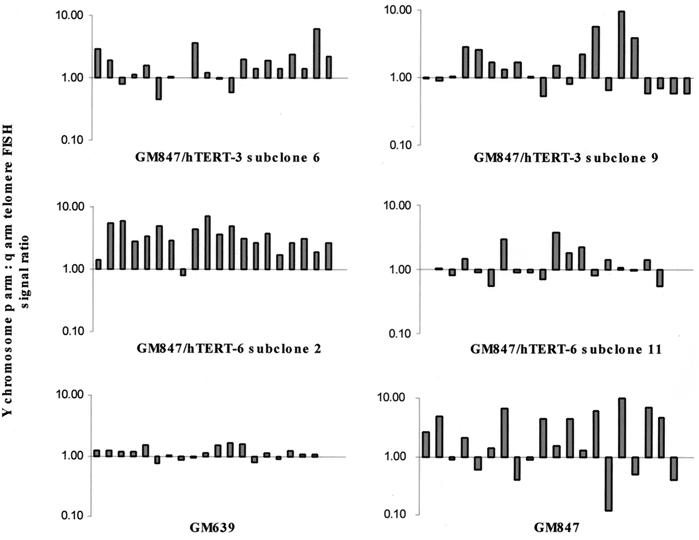

We then compared the telomere FISH signals of the p and q arms of the Y chromosome, which was present in single copy in subclones of GM847/hTERT-3 and GM847/hTERT-6. It was found that within each GM847/hTERT subclone there was dramatic variation in the ratio of these signals, consistent with the GM847 untransfected control, which was not seen in the telomerase-positive cell line, GM639 (SV40-immortalized skin fibroblasts) (Fig. 5). This marked fluctuation in p:q ratio must have occurred subsequent to subcloning, consistent with the presence of continuing ALT activity in these cells.

FIG. 5.

Ratio of p arm to q arm telomere lengths on the Y chromosome from 20 metaphase spreads of each GM847/hTERT subclone indicated, including a GM847 (ALT) and GM639 (telomerase-positive) control. Each bar represents the ratio for an individual metaphase. The ratio was calculated using the Y chromosome mean telomere fluorescence signal intensities from captured images of each metaphase nucleus at exposure times of 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 s.

We examined the GM847/hTERT cells for the presence of APBs. APBs are PML bodies containing low-molecular-weight telomeric DNA and telomere-associated proteins and are present in all ALT cell lines examined to date (including GM847) but not in telomerase-positive or mortal cells (47), and they can be readily detected in interphase nuclei from metaphase preparations by telomere FISH. In exponentially growing cultures of ALT cells, APBs are present in approximately 5% of the population. Their occurrence has a close temporal correlation with activation of ALT in cell lines immortalized in vitro (47). They are thus an excellent marker of ALT activity, although the role of APBs in the mechanism of ALT is unknown. APBs were detectable by telomere FISH at all PD levels examined for GM847/hTERT-3 and GM847/hTERT-6 cells and in subclones of these cells (Fig. 6). The proportion of cells with detectable APBs was maintained within the range characteristic of untransfected GM847 cells (Table 2) (47). These data suggest that ALT can still operate in the presence of exogenous hTERT, and it coexists with telomerase activity as a telomere maintenance mechanism in GM847/hTERT cells.

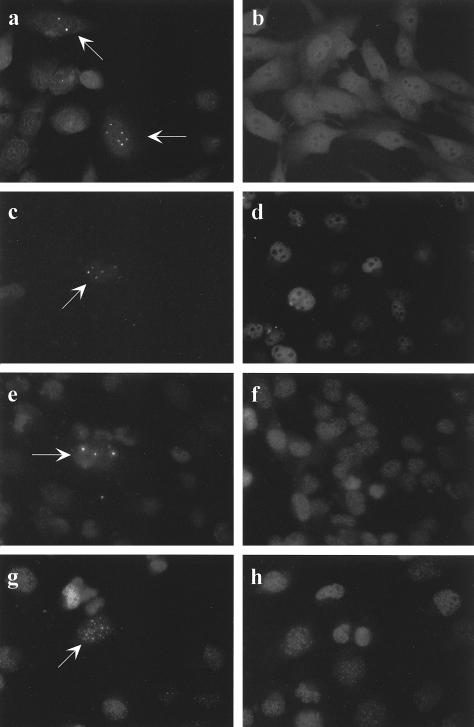

FIG. 6.

Detection of APBs in interphase nuclei of GM847/hTERT cells by telomere FISH. Representative images are shown (magnification, ×100). (a) Untransfected GM847; (b) GM847/hTERT-3 (PD 42); (c) GM847/hTERT-3 (PD 138); (d) GM847/hTERT-3 subclone 9 (PD 25); (e) GM847/hTERT-6 (PD 150); (f) GM847/hTERT-6 subclone 11 (PD 25).

TABLE 2.

Detection of APBs in GM847/hTERT cells by telomere FISH using a peptide-nucleic acid probe

| Cell type | Nuclei with detectable APBs (%)a |

|---|---|

| GM847 untransfected | 3 |

| GM847/hTERT-3 (PD 42) | 4 |

| GM847/hTERT-3 (PD 106) | 3 |

| GM847/hTERT-3 (PD 138) | 4 |

| GM847/hTERT-6 (PD 46) | 5 |

| GM847/hTERT-6 (PD 82) | 4 |

| GM847/hTERT-6 (PD 150) | 5 |

| GM847/hTERT-3 subclone 6 (PD25) | 4 |

| GM847/hTERT-3 subclone 9 (PD25) | 2 |

| GM847/hTERT-6 subclone 2 (PD25) | 5 |

| GM847/hTERT-6 subclone 11 (PD25) | 3 |

Five hundred interphase nuclei were scored for each cell type.

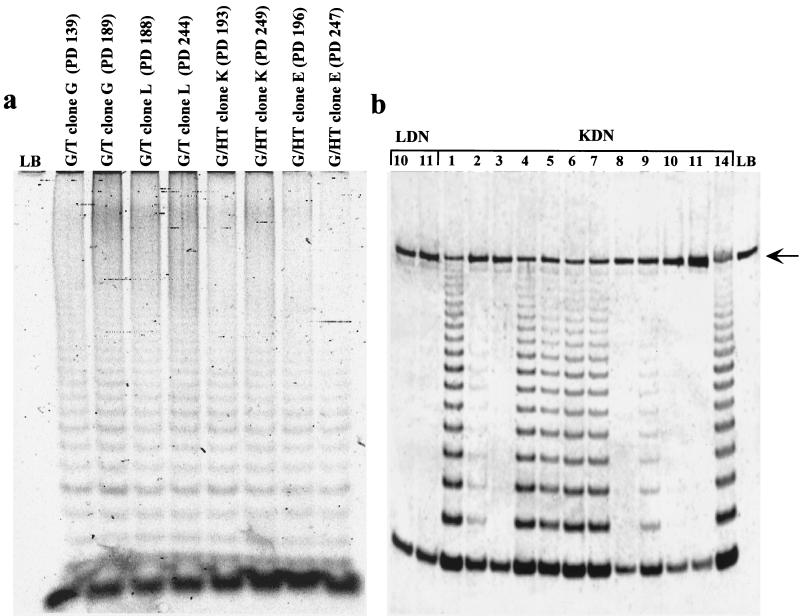

Endogenous telomerase is required for the immortal phenotype in somatic cell hybrids of ALT cells and telomerase-positive cells.

The coexistence of telomerase and ALT was further investigated by utilizing somatic cell hybrids of ALT and telomerase-positive cells. We previously generated such hybrids by fusion of GM847 cells with both HT-1080 and T24 telomerase-positive cells and showed that the resulting hybrid clones were telomerase positive (35). Investigation of telomere dynamics in these cells revealed an initial rapid deletion of large telomeric tracts, indicating repression of ALT, followed by a normal rate of telomere shortening which suggested that telomerase was unable to maintain the telomeres (35). DNA fingerprinting and immunostaining for SV40 T-antigen expression at both early and late PDs indicated that the clones were indeed hybrids, containing genetic material from both parental cells (data not shown). A number of these hybrid clones were continuously passaged to determine the effect of endogenous telomerase on the ALT phenotype.

Four hybrid clones, GM847 × HT-1080 (G/HT) clones E and K and GM847 × T24 (G/T) clones G and L, were passaged for approximately 300 PDs with no occurrence of growth arrest or senescence. These cells were positive in the TRAP assay at each PD level tested, indicating that they retained in vitro telomerase activity throughout this period of growth (Fig. 7a). To determine whether telomerase was actually required for continuing growth of the hybrid cells, we transfected clones G/HT K and G/T L with a dominant-negative hTERT (dn hTERT) expression plasmid. This plasmid expresses an hTERT protein which contains an amino acid substitution within the catalytic core and which has been characterized previously as an inhibitor of telomerase activity. It has also been shown to cause telomere shortening and can induce apoptosis (48) or senescence (10) following transfection into telomerase-positive human cell lines.

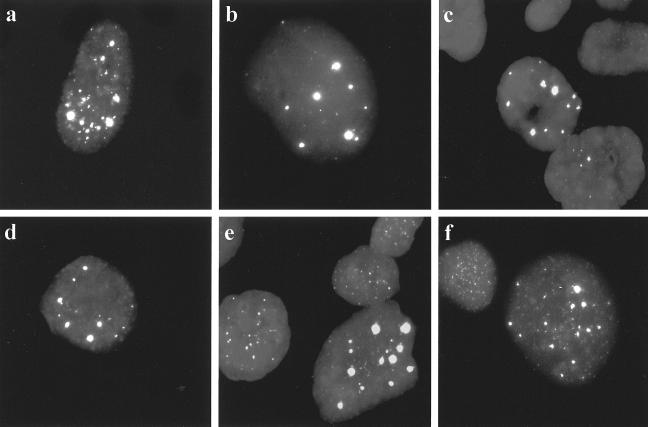

FIG. 7.

(a) TRAP analysis of G/T clones G and L and G/HT clones E and K at the PD timepoints indicated. (b) TRAP analysis of hybrid clones G/HT K (KDN) and G/T L (LDN) expressing dn hTERT. LB, lysis buffer negative control. An internal control (rat myogenin) for the PCR is indicated by an arrow.

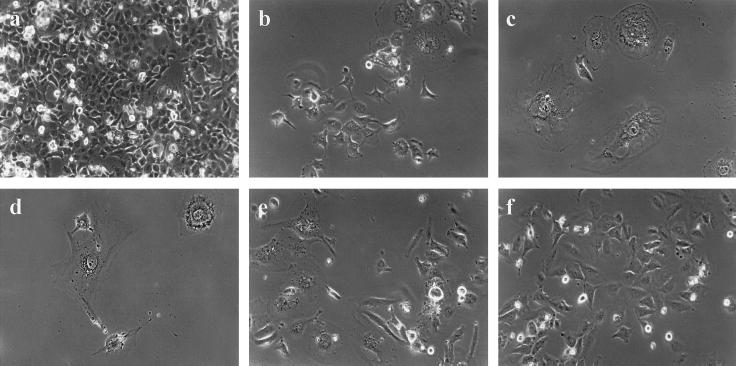

Fifteen colonies were isolated from the G/HT K (KDN) and 19 from the G/T L (LDN) dn hTERT transfections. At early PDs, before the colonies had expanded sufficiently to permit harvesting of cells for analysis, 3 KDN clones and 17 LDN clones ceased dividing, with the cells displaying the large, flat morphology characteristic of senescence. Twelve KDN clones and only two LDN clones underwent sufficient PDs to allow analysis of telomerase activity by TRAP (Fig. 7b). KDN clones 3, 8, 10, and 11 showed complete inhibition of telomerase activity, with weak activity detectable in clones 2 and 9. All other KDN clones that could be analyzed were telomerase positive, which was consistent with previous studies utilizing this same dn hTERT construct that reported the emergence of telomerase-positive revertants (10, 20). LDN clones 10 and 11 also showed complete inhibition of telomerase activity (Fig. 7b). TRF analyses of a subset of KDN and LDN clones showed telomere shortening in the absence of telomerase and stabilization or lengthening in clones that retained telomerase activity (data not shown). The inhibition of telomerase in these clones correlated with the appearance of a senescent phenotype. In contrast, the clones that were telomerase positive continued to divide, with no onset of growth arrest. Representative cell morphologies for both senescent and proliferating clones are shown in Fig. 8. KDN 7 cells (Fig. 8a), which are telomerase positive, divide rapidly, grow at high densities, and have detectable mitotic cells, which is also characteristic of the other telomerase-positive KDN clones. In contrast, KDN 10 and KDN 11 cells, which are telomerase inhibited, no longer divide, and many have become enlarged (Fig. 8b and c), which was also apparent in LDN clones 10 and 11 (Fig. 8e and f). Most LDN clones stopped dividing at very early PD levels (when they had formed small colonies), and the few surviving cells also appeared enlarged and senescent (Fig. 8d). Telomerase is therefore required for continued cell growth in these hybrids.

FIG. 8.

Phase-contrast photomicrographs of dn hTERT transfected subclones of G/HT hybrid clone K (KDN) and G/T hybrid clone L (LDN). Magnification, ×15. Representative images are shown. (a) KDN clone 7; (b) KDN clone 10; (c) KDN clone 11; (d) an LDN colony; (e) LDN clone 11; (f) LDN clone 10.

It has been reported previously that expression of dn hTERT in GM847 cells has no effect on proliferation or telomere lengths of GM847 cells (16). Consistent with this finding, we recently established stable clones of GM847 expressing dn hTERT, and there was no evidence of proliferation arrest at early PD levels (data not shown). These results support the conclusion that telomerase is the sole telomere maintenance mechanism in the hybrid cells.

APBs are lost from the somatic cell hybrids.

As further evidence that there was no ALT activity in the hybrid cells, we tested each of the four hybrid clones for APBs. Hybrid clones at early and late PDs were immunostained with anti-hTRF2 antibodies to visualize APBs (Fig. 9). At the earlier PDs, in each case there were rare nuclei (1 out of 1,000 to 2,000) that had detectable APBs (Fig. 9c, e, and g), but most had the punctate staining pattern that is characteristic of telomerase-positive cells (Fig. 9b). Thus, 0.05 to 0.1% of the hybrid cells had APBs at early time points, which is at least a 30-fold reduction from the level in untransfected GM847 cells (47). At later PDs there were no APBs detected in any nuclei examined (Fig. 9d, f, and h). In contrast, analysis of GM847/hTERT subclones showed no loss of APBs at later time points (Table 2 and Fig. 6). These data provide further evidence that ALT is fully repressed in the hybrid clones but is still functional in GM847/hTERT clones.

FIG. 9.

Detection of APBs by immunostaining with antibodies to hTRF2. Representative cells (magnification, ×40) are shown. (a) GM847 ALT control. APBs are detectable in 1 to 5% of nuclei (arrow). (b) GM639 (SV40-immortalized fibroblasts) telomerase-positive control. No APBs are visible in any nucleus. (c through h) Somatic cell hybrid clones at different PD levels. Left panels indicate rare individual nuclei (arrow) at earlier PDs in which APBs could be detected. Right panels are indicative of all nuclei examined at later PDs for each hybrid in which only the punctate pattern of staining characteristic of ALT-negative human cells (47) was seen. (c) G/HT K (PD 43); (d) G/HT K (PD 134); (e) G/T L (PD 58); (f) G/T L (PD 148); (g) G/HT E (PD 23); (h) G/HT E (PD 62).

Endogenous telomerase eventually stabilizes and maintains telomeres in the ALT-repressed hybrids.

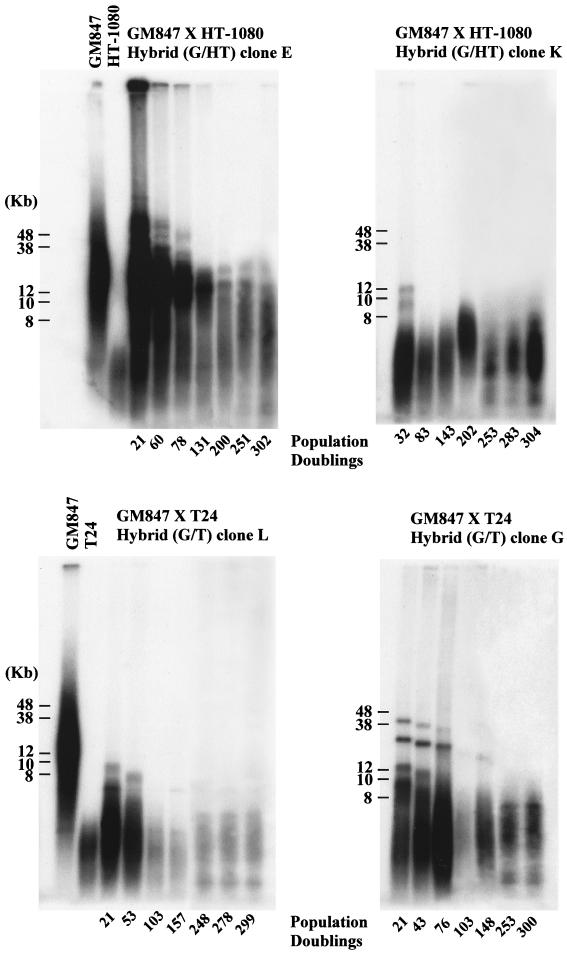

The results from the dn hTERT transfection experiment implied that telomerase activity was important for the survival of the hybrid clones, presumably through its role in telomere maintenance. This further implied that the telomeres of these hybrids would eventually stop shortening. To test this, TRF analysis of hybrid clones G/HT E and K and G/T G and L (Fig. 10) was performed. As observed previously (35), the long telomeres contributed by GM847 cells were not maintained at early PDs and indeed were lost from clones K, L, and G at a much faster rate than that observed in normal telomerase-negative cells. In clone K, which lost the large TRFs most rapidly, the telomere length then fluctuated around a mean length below 8 kb, while clones E, G, and L entered a phase in which the telomeres continued to shorten but at a less rapid rate (Fig. 10). The telomere length dynamics in clone K suggest that there may be some dysregulation of factors that stabilize telomeres which was not apparent in the other clones (Fig. 10). Other studies have shown that telomere length can vary in the presence of telomerase (7, 22, 39) and that there may be fluctuation around a mean telomere length (39).

FIG. 10.

TRF analysis of hybrid clones G/HT E and K and G/T L and G at the PD levels indicated. The analysis was performed using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis as described in Materials and Methods. Parental cell TRFs are shown in the left-hand panels.

The presence of discrete TRF bands allowed us to more accurately measure the rate of shortening for clones E, G, and L (175, 67, and 44 bp/PD, respectively), and these were consistent with the rates of telomere shortening (50 to 200 bp/PD) that had been previously reported for mortal cells (11, 18, 21). These results therefore show that telomerase did not maintain the long telomeres on the chromosomes contributed to the hybrids by the ALT cells. The second phase of shortening in three of the four clones (G/HT E and G/T L and G) occurred at a rate characteristic of normal cells which have no telomerase activity. At later PD levels, however, the TRF lengths stabilized, indicating telomere maintenance by telomerase.

DISCUSSION

We report that exogenous expression of hTERT in GM847 ALT cells lengthens the shortest telomeres. Although transfection of hTERT into ALT cells has been shown to induce in vitro TRAP activity (13, 45), it has not been demonstrated previously that this telomerase activity has any effect on the telomeres in vivo. In other circumstances it has been shown clearly that TRAP activity is not synonymous with in vivo enzyme activity: hTERT that was modified at the carboxyl terminus induced TRAP activity when expressed in telomerase-negative mortal cells but was not able to maintain the telomeres (12). We have demonstrated in this study that hTERT expression results in telomerase activity that acts on some of the telomeres of GM847 cells, as detected by telomere FISH. This effect was most apparent after subcloning and continued passaging, most likely because the telomere lengthening was a gradual process that did not occur equally in all cells within the population. Within the untransfected GM847 population every metaphase nucleus examined had chromosome ends without a detectable telomere FISH signal. This indicates that the telomere lengthening was due to hTERT expression and not due to random clonal selection of preexisting cells within the population in which telomere lengthening had already occurred. As a corollary, the data indicate that the GM847 cells express sufficient levels of whatever factors, other than hTERT, are required for telomerase-mediated lengthening of telomeres.

Although telomerase is active in the GM847/hTERT cells, these cells retain hallmarks of ALT activity, that is, persistence of heterogeneous telomeres and of APBs. Additionally, the very long telomeres were present on different chromosomes in clonal populations of late-passage GM847/hTERT cells, which is consistent with ALT involving a telomere-telomere recombination mechanism (14). This indicates that telomerase and ALT are both active in the GM847/hTERT cells. In contrast, when ALT was repressed in somatic cell hybrids of GM847 with a telomerase-positive cell line, the telomeres rapidly decreased in length and the APBs disappeared. We previously found that some human tumors exhibit both telomere maintenance mechanisms (6). The present lack of assays suitable for analysis of individual cells within tumors means that it is currently not possible to determine whether these tumors contain subpopulations with one or other telomere maintenance mechanisms, or whether there are tumor cells utilizing more than one mechanism. The results reported here do not answer this question regarding tumors, but they do show that it is possible for more than one mechanism to be active in the same cell.

It has been demonstrated previously in yeast that cells lacking telomerase utilize a recombination pathway to maintain telomeres and continue proliferating (29, 32). It has been suggested that this mechanism in yeast, which is dependent on RAD52, may be a general alternative pathway for telomere maintenance in eukaryotes (32). Some telomerase-negative Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells survive by a mechanism that closely resembles that in human ALT cells: type II survivors have telomeres with extremely heterogeneous lengths (29, 42). The type II mechanism in yeast and ALT in human cells both involve recombination (14, 41). The data presented here, however, suggest that the ALT mechanism in human cells may differ somewhat from that in yeast. In yeast type II survivors, telomere lengthening only occurs on very short telomeres (41), and it has been shown that reconstitution of telomerase activity in S. cerevisiae inhibits this ALT-like mechanism and returns the telomeres to wild-type lengths over a number of PDs (42). In GM847/hTERT cells, however, the hallmarks of ALT activity persist even when the shortest telomeres have been lengthened by telomerase.

We also report that in somatic cell hybrid clones, generated by fusion of GM847 cells with each of two telomerase-positive cell lines (ALT × telomerase), ALT is repressed and the telomeres are maintained by endogenous telomerase activity. Features of ALT disappeared, i.e., the abnormally long telomeres (35) and APBs. Transfection of the ALT × telomerase hybrid cells with dn hTERT demonstrated that their continued survival was dependent on telomerase activity, which is consistent with the other data indicating that ALT was repressed. The factor(s) responsible for ALT repression in these hybrids has yet to be identified, but the lack of ALT repression in the hTERT-transfected GM847 cells also suggests that it is unlikely to be telomerase. It is possible that telomerase activity induced by overexpression of hTERT in ALT cells is not entirely comparable to the endogenous telomerase activity in the hybrids. Further, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that ALT repression in the hybrids is mediated via telomerase, maybe indirectly, in concert with some other factor which is lacking in the GM847/hTERT cells and which is contributed along with telomerase activity to the hybrid by the telomerase-positive cells. However, it has been previously shown that ALT is repressed in ALT × normal somatic cell hybrids (35); in these hybrids repression of ALT was clearly not due to telomerase, as neither the normal cells nor the hybrids expressed any telomerase activity.

Interestingly, in both the ALT × telomerase-positive hybrids and in the ALT × normal fibroblast hybrids (35) there was an initial rapid loss of telomeric tracts, suggesting that an active mechanism was involved. Rapid telomere loss has also been reported in yeast, where cleavage of long telomeres to a wild-type size could occur within a single cell division (27).

Candidate ALT repressors include telomere-associated proteins contributed to the hybrids by the telomerase cells. It is very possible that more than one repressor of ALT exists in these cells, which would greatly reduce the probability of ALT revertants if telomerase activity was abrogated. Previous studies have shown that human telomere binding proteins hTRF1 (38, 43) and hTRF2 (38) play a direct role in regulation of telomere elongation by telomerase and prevent overextension of telomere tracts. In yeast it has been shown that the telomere binding protein Rap1p tightly regulates telomere lengths (31) and that Rap1p binding proteins, Rif1 and Rif2, inhibit both telomerase and type II recombination mechanisms (41). While it remains entirely possible that proteins that regulate both telomerase and ALT in human cells will be found, our somatic cell hybrid data show that ALT and telomerase can be controlled separately.

Telomere shortening occurs at normal rates in the hybrid cells despite the presence of telomerase, but this is eventually followed at later PDs by telomere length stabilization at lengths characteristic of telomerase-positive cells. This indicates, consistent with our findings in GM847/hTERT cells, that short telomeres are lengthened by telomerase. However, unlike ALT, there appears to be a control mechanism in telomerase-positive cells that prevents maintenance by telomerase of telomeres above a certain length. There is strong evidence for the existence of such a regulatory mechanism in yeast (30, 31). Studies on telomerase-positive human immortalized cells have also found evidence for telomere length control and have suggested the existence of an equilibrium mean length for individual telomeres, above which shortening can occur in the presence of telomerase activity (39). In some cases, telomeres can be maintained by telomerase at subsenescent lengths (11, 40, 49).

The data presented here provide new insights into the regulation of telomerase and ALT in human cells and also suggest some possible differences between ALT and the mechanism in yeast type II survivors. In view of the current interest in developing anticancer therapeutics directed against telomerase, it will be of particular interest to determine whether ALT and telomerase sometimes coexist in individual tumor cells. An understanding of the mechanisms whereby ALT is normally repressed may also identify useful therapeutic targets.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Peter Rowe for his comments on the manuscript and Murray Robinson, Amgen Corporation, for providing the dominant-negative hTERT construct.

These studies were supported by a project grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the Carcinogenesis Fellowship of the New South Wales Cancer Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allsopp R C, Harley C B. Evidence for a critical telomere length in senescent human fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 1995;219:130–136. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allsopp R C, Vaziri H, Patterson C, Goldstein S, Younglai E V, Futcher A B, Greider C W, Harley C B. Telomere length predicts replicative capacity of human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10114–10118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bacchetti S, Counter C M. Telomeres and telomerase in human cancer. Int J Oncol. 1995;7:423–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackburn E H. Structure and function of telomeres. Nature. 1991;350:569–573. doi: 10.1038/350569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broccoli D, Smogorzewska A, Chong L, de Lange T. Human telomeres contain two distinct Myb-related proteins, TRF1 and TRF2. Nat Genet. 1997;17:231–235. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryan T M, Englezou A, Dalla-Pozza L, Dunham M A, Reddel R R. Evidence for an alternative mechanism for maintaining telomere length in human tumors and tumor-derived cell lines. Nat Med. 1997;3:1271–1274. doi: 10.1038/nm1197-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryan T M, Englezou A, Dunham M A, Reddel R R. Telomere length dynamics in telomerase-positive immortal human cell populations. Exp Cell Res. 1998;239:370–378. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryan T M, Englezou A, Gupta J, Bacchetti S, Reddel R R. Telomere elongation in immortal human cells without detectable telomerase activity. EMBO J. 1995;14:4240–4248. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00098.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryan T M, Reddel R R. Telomere dynamics and telomerase activity in in vitro immortalised human cells. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:767–773. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colgin L M, Wilkinson C, Englezou A, Kilian A, Robinson M O, Reddel R R. The hTERTα splice variant is a dominant negative inhibitor of telomerase activity. Neoplasia. 2000;2:426–432. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Counter C M, Avilion A A, LeFeuvre C E, Stewart N G, Greider C W, Harley C B, Bacchetti S. Telomere shortening associated with chromosome instability is arrested in immortal cells which express telomerase activity. EMBO J. 1992;11:1921–1929. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Counter C M, Hahn W C, Wei W, Dickinson Caddle S, Beijersbergen R L, Lansdorp P M, Sedivy J M, Weinberg R A. Dissociation among in vitro telomerase activity, telomere maintenance, and cellular immortalization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14723–14728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Counter C M, Meyerson M, Eaton E N, Ellisen L W, Dickinson Caddle S, Haber D A, Weinberg R A. Telomerase activity is restored in human cells by ectopic expression of hTERT (hEST2), the catalytic subunit of telomerase. Oncogene. 1998;16:1217–1222. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunham M A, Neumann A A, Fasching C L, Reddel R R. Telomere maintenance by recombination in human cells. Nat Genet. 2000;26:447–450. doi: 10.1038/82586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greider C W, Blackburn E H. Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in Tetrahymena extracts. Cell. 1985;43:405–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hahn W C, Stewart S A, Brooks M W, York S G, Eaton E, Kurachi A, Beijersbergen R L, Knoll J H M, Meyerson M, Weinberg R A. Inhibition of telomerase limits the growth of human cancer cells. Nat Med. 1999;5:1164–1170. doi: 10.1038/13495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hande M P, Samper E, Lansdorp P, Blasco M A. Telomere length dynamics and chromosomal instability in cells derived from telomerase null mice. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:589–601. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.4.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harley C B, Futcher A B, Greider C W. Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature. 1990;345:458–460. doi: 10.1038/345458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harley C B, Vaziri H, Counter C M, Allsopp R C. The telomere hypothesis of cellular aging. Exp Gerontol. 1992;27:375–382. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(92)90068-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrington L, Zhou W, McPhail T, Oulton R, Yeung D S K, Mar V, Bass M B, Robinson M O. Human telomerase contains evolutionarily conserved catalytic and structural subunits. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3109–3115. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.23.3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hastie N D, Dempster M, Dunlop M G, Thompson A M, Green D K, Allshire R C. Telomere reduction in human colorectal carcinoma and with ageing. Nature. 1990;346:866–868. doi: 10.1038/346866a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones C J, Soley A, Skinner J W, Gupta J, Haughton M F, Wyllie F S, Schlumberger M, Bacchetti S, Wynford-Thomas D. Dissociation of telomere dynamics from telomerase activity in human thyroid cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 1998;240:333–339. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.3944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kilian A, Bowtell D D L, Abud H E, Hime G R, Venter D J, Keese P K, Duncan E L, Reddel R R, Jefferson R A. Isolation of a candidate human telomerase catalytic subunit gene, which reveals complex splicing patterns in different cell types. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:2011–2019. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.12.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim N W, Piatyszek M A, Prowse K R, Harley C B, West M D, Ho P L C, Coviello G M, Wright W E, Weinrich S L, Shay J W. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science. 1994;266:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.7605428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lansdorp P M, Verwoerd N P, Van de Rijke F M, Dragowska V, Little M-T, Dirks R W, Raap A K, Tanke H J. Heterogeneity in telomere length of human chromosomes. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:685–691. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.5.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy M Z, Allsopp R C, Futcher A B, Greider C W, Harley C B. Telomere end-replication problem and cell aging. J Mol Biol. 1992;225:951–960. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li B, Lustig A J. A novel mechanism for telomere size control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1310–1326. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.11.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindsey J, McGill N I, Lindsey L A, Green D K, Cooke H J. In vivo loss of telomeric repeats with age in humans. Mutat Res. 1991;256:45–48. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(91)90032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundblad V, Blackburn E H. An alternative pathway for yeast telomere maintenance rescues est1− senescence. Cell. 1993;73:347–360. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90234-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcand S, Brevet V, Gilson E. Progressive cis-inhibition of telomerase upon telomere elongation. EMBO J. 1999;18:3509–3519. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.12.3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marcand S, Gilson E, Shore D. A protein-counting mechanism for telomere length regulation in yeast. Science. 1997;275:986–990. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McEachern M J, Blackburn E H. Cap-prevented recombination between terminal telomeric repeat arrays (telomere CPR) maintains telomeres in Kluyveromyces lactis lacking telomerase. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1822–1834. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.14.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moyzis R K, Buckingham J M, Cram L S, Dani M, Deaven L L, Jones M D, Meyne J, Ratliff R L, Wu J-R. A highly conserved repetitive DNA sequence, (TTAGGG)n, present at the telomeres of human chromosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6622–6626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olovnikov A M. Principle of marginotomy in template synthesis of polynucleotides. Dokl Akad Nauk SSSR. 1971;201:1496–1499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perrem K, Bryan T M, Englezou A, Hackl T, Moy E L, Reddel R R. Repression of an alternative mechanism for lengthening of telomeres in somatic cell hybrids. Oncogene. 1999;18:3383–3390. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perrem K, Reddel R R. Telomeres and cell division potential. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2000;24:173–189. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-06227-2_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reddel R. A reassessment of the telomere hypothesis of senescence. Bioessays. 1998;20:977–984. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199812)20:12<977::AID-BIES3>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smogorzewska A, van Steensel B, Bianchi A, Oelmann S, Schaefer M R, Schnapp G, de Lange T. Control of human telomere length by TRF1 and TRF2. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1659–1668. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1659-1668.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sprung C N, Sabatier L, Murnane J P. Telomere dynamics in a human cancer cell line. Exp Cell Res. 1999;247:29–37. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steinert S, Shay J W, Wright W E. Transient expression of human telomerase extends the life span of normal human fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;273:1095–1098. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teng S-C, Chang J, McCowan B, Zakian V A. Telomerase-independent lengthening of yeast telomeres occurs by an abrupt Rad50p-dependent, Rif-inhibited recombinational process. Mol Cell. 2000;6:947–952. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(05)00094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teng S-C, Zakian V A. Telomere-telomere recombination is an efficient bypass pathway for telomere maintenance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:8083–8093. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Steensel B, de Lange T. Control of telomere length by the human telomeric protein TRF1. Nature. 1997;385:740–743. doi: 10.1038/385740a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watson J D. Origin of concatemeric T7 DNA. Nat New Biol. 1972;239:197–201. doi: 10.1038/newbio239197a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wen J, Cong Y-S, Bacchetti S. Reconstitution of wild-type or mutant telomerase activity in telomerase negative immortal human cells. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1137–1141. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.7.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wright W E, Shay J W, Piatyszek M A. Modifications of a telomeric repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) result in increased reliability, linearity and sensitivity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3794–3795. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.18.3794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yeager T R, Neumann A A, Englezou A, Huschtscha L I, Noble J R, Reddel R R. Telomerase-negative immortalized human cells contain a novel type of promyelocytic leukemia (PML) body. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4175–4179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang X, Mar V, Zhou W, Harrington L, Robinson M O. Telomere shortening and apoptosis in telomerase-inhibited human tumor cells. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2388–2399. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu J, Wang H, Bishop J M, Blackburn E H. Telomerase extends the lifespan of virus-transformed human cells without net telomere lengthening. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3723–3728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]