Abstract

The activation of IκB kinase (IKK) is a key step in the nuclear translocation of the transcription factor NF-κB. IKK is a complex composed of three subunits: IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ (also called NEMO). In response to the proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF), IKK is activated after being recruited to the TNF receptor 1 (TNF-R1) complex via TNF receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2). We found that the IKKα and IKKβ catalytic subunits are required for IKK-TRAF2 interaction. This interaction occurs through the leucine zipper motif common to IKKα, IKKβ, and the RING finger domain of TRAF2, and either IKKα or IKKβ alone is sufficient for the recruitment of IKK to TNF-R1. Importantly, IKKγ is not essential for TNF-induced IKK recruitment to TNF-R1, as this occurs efficiently in IKKγ-deficient cells. Using TRAF2−/− cells, we demonstrated that the TNF-induced interaction between IKKγ and the death domain kinase RIP is TRAF2 dependent and that one possible function of this interaction is to stabilize the IKK complex when it interacts with TRAF2.

The transcription factor NF-κB plays a critical role in regulating the expression of many cytokines and immunoregulatory proteins (1, 2, 3). NF-κB is composed of homo- or heterodimers of Rel and NF-κB proteins (1). The transcription activity of NF-κB can be elevated by various stimuli, including the proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF) (24). When bound to their specific inhibitors, referred to as IκBs, NF-κB dimers are sequestered in the cytoplasm and are therefore inactive (1, 32). In response to various stimuli, IκBs are phosphorylated by the IκB kinase complex (IKK) and are then rapidly degraded by the proteasome after their polyubiquitination (1). The degradation of IκBs allows NF-κB to translocate into the nucleus and activate its target genes (1).

The three proteins IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ (also called NEMO) were identified as the components of the IKK complex (6, 23, 26, 29, 36, 37, 39, 40). IKKα and IKKβ are two related catalytic subunits sharing about 52% identity, both containing an N-terminal kinase domain, a leucine zipper, and C-terminal helix-loop-helix motifs (12). IKKα and IKKβ can form homo- or heterodimers via their leucine zipper motif, but the predominant IKK complex appears to contain mostly IKKα and IKKβ heterodimers (29). The recent generation of IKKα−/− and IKKβ−/− mice has established that IKKα and IKKβ are required for the activation of NF-κB, although the absence of IKKα has a much smaller effect due to a compensatory effect of IKKβ (11, 15, 17, 18, 34). In IKKα and IKKβ double-knockout cells, TNF-induced NF-κB activation is completely abolished (16). Interestingly, however, IKKα and IKKβ knockout mice exhibit completely different phenotypes (11, 15, 18, 34). It has also been suggested that IKKα plays a role in the activation of IKKβ (25). However, IKK activation by TNF or interleukin-1 is barely affected in IKKα−/− cells (11). Meanwhile, IKKγ is the regulatory subunit of the complex, and it binds to the C termini of IKKα and IKKβ (22, 29, 37). Studies with IKKγ-deficient cells have proven the essential role of IKKγ in the activation of IKK and NF-κB (30, 37). Heterozygous female mice with IKKγ deficiencies exhibit a dermatopathy similar to the human X-linked disorder incontinentia pigmenti (21, 31).

In response to TNF, IKK is quickly activated, which correlates with IKK recruitment to the TNF receptor complex (5, 42). Two components of the TNF receptor 1 (TNF-R1) signaling complex, TNF receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) and the death domain kinase receptor-interacting protein (RIP), were shown to be required for NF-κB and IKK activation (5, 13, 35, 38). Although over expression of either RIP or TRAF2 could lead to robust NF-κB and IKK activation, the absence of either protein results in decreased TNF-induced NF-κB and IKK activation (5, 13, 35, 38). Recently, it has been found that TRAF2 and RIP play distinct signaling roles: TRAF2 recruits IKK to TNF-R1, whereas RIP mediates IKK activation (5). Interestingly, a TNF-induced interaction between IKKγ and RIP which has been suggested to play a role in IKK recruitment to the TNF-R1 complex has also been observed (42).

In order to understand the mechanism underlying the interaction between TRAF2 and IKK, we investigated the respective role of each IKK subunit in this process. We also addressed the role of the interaction between RIP and IKKγ in IKK recruitment. We found that IKKα and IKKβ interact with TRAF2, but IKKγ does not. This interaction requires the leucine zipper motif of IKKα or IKKβ and the RING finger motif of TRAF2. Using IKKγ-deficient cells, we found that the regulatory subunit is dispensable for IKKα and IKKβ recruitment to the TNF-R1 complex. Although IKKγ interacts with RIP in response to TNF, this interaction is TRAF2 dependent.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and plasmids.

Anti-RIP antibody was purchased from Transduction Laboratories. Anti-TRAF2, anti-Xpress, anti-IKKα, anti-TNF-R1-associated death domain protein (anti-TRADD), and antihemagglutinin (anti-HA) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz. Anti-IKKγ and anti-Myc antibodies were from Pharmingen. The anti-IKKβ antibody was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology. The anti-Flag antibody was purchased from Sigma. The anti-TNF-R1 antibody was from R&D Systems. Human and mouse TNF-α (mTNF-α) were purchased from R&D Systems. The mammalian expression plasmids for Myc-RIP, Flag-TRAF2, HA-IKKα, HA-IKKβ, and IKKγ have been described previously (10, 20, 39). The constructs for different glutatnione S-transferase (GST)–TRAF2 fusion proteins were previously described (14). The constructs for in vitro-translated HA-IKKα, HA-IKKβ, and HA-IKKγ were generated by subcloning these genes into the pBluescript vector (Stratagene). The expression plasmids for different domains of IKKα and IKKβ were constructed by subcloning the different fragments (HindIII-XbaI for IKKα1–371, HindIII-EcoRV for IKKα1–500, EcoRV-NotI for IKKα500–745, HindIII-BglII for IKKβ1–399, BglII-XhoI for IKKβ399–577, and BglII-NotI for IKKβ399–756) of the IKKα and IKKβ genes into the pcDNA vector (Invitrogen).

Cell culture and transfection.

Wild-type (wt), IKKα−/−, and IKKβ−/− mouse fibroblast and HEK293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum or 10% calf serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/of penicillin/ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin/ml; wt and (IKKγ)-deficient (5R) rat fibroblast were also cultured in this medium. RIP−/− and TRAF2−/− cells were cultured in the same medium except that 0.3 mg/of G418/ml was included. Transfection experiments were performed with Lipofectamine PLUS reagent by following the instructions provided by the manufacturer (GIBCO/BRL).

Western blot analysis and coimmunoprecipitation.

For Western blotting, cells were treated with mTNF-α as described in the figure legends and then collected in M2 lysis buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7], 0.5% NP-40, 250 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 3 mM EGTA, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 20 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 1 μg of leupeptin/ml; 1 μg of aprotinin/ml, 1 μg of pepstatin/ml, and 10 mM pNpp). Fifty micrograms of the cell lysates were fractionated on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–4 to 20% polyacrylamide gels, and Western blottings were performed with the desired antibodies. The proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham).

For immunoprecipitation assays, 3 × 107 mTNF-α (40 ng/ml)-treated or untreated fibroblasts were collected in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.6], 250 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM pherylinethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg of leupeptin/ml, 1 μg of aprotinin/ml, and 1 μg of pepstatin/ml). The lysates were mixed and precipitated with the relevant antibody and protein A-Sepharose beads by incubation at 4°C for 4 h to overnight. The beads were washed four times with 1 ml of lysis buffer, and the bound proteins were resolved in SDS–10% polyacrylamide gels and detected by Western blot analysis. For immunoprecipitations with antibodies that were cross-linked to protein A-Sepharose beads as indicated in the figure legends, antibodies (100 μg of antibody/ml of wet beads) were coupled to the beads with dimethylpimelimidate as previously described (7).

For GST pull-down experiments with in vitro translated, 35S-labeled IKK subunits and different GST-TRAF2 proteins (14), 5 μg of each GST protein was combined with the in vitro translation lysate of each IKK subunit in 1 ml of lysis buffer (see above) and incubated at 4°C for 2 h. Glutathione-Sepharose beads were then added, and incubation was performed overnight. The beads were extensively washed with lysis buffer and the bound proteins were resolved in SDS–10% polyacrylamide gels. The GST-TRAF2 proteins were detected by Coomassie blue staining and the coprecipitated IKK proteins were visualized by autoradiography.

RESULTS

IKK is recruited to TNF-R1 through an interaction between IKKα or IKKβ and TRAF2.

In response to TNF binding to TNF-R1, a signaling complex is rapidly formed that includes TRADD, RIP, and TRAF2 (8, 9, 10, 19, 27, 28, 33). Recently, IKK was found to be recruited to the same TNF-R1 complex (5); moreover, its recruitment was found to be mediated by TRAF2 (5). The recruitment of IKK to the TNF-R1 signaling complex can be detected by immunoprecipitation experiments with anti-TNF-R1 antibody following TNF treatment. As shown in Fig. 1A, three IKK subunits, IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ were recruited to the TNF-R1 in wt mouse fibroblasts but not in TRAF2−/− fibroblasts. In RIP−/− fibroblasts, IKKα and IKKβ recruitment to TNF-R1 was similar to that in wt cells but the recruitment of IKKγ was notably decreased in comparison to what was observed in wt cells (Fig. 1A). The recruitment of TRAF2, TRADD, and RIP to TNF-R1 in wt, RIP−/−, and TRAF2−/− fibroblasts is shown in Fig. 1B. As was reported previously (5), TRAF2 plays an essential role in recruiting IKK to TNF-R1.

FIG. 1.

Recruitment of IKK to TNF-R1 requires TRAF2. (A) Cell extracts were prepared from wt, RIP−/− and TRAF2−/− fibroblasts either treated for 2 min. with 40 ng of mTNF-α/ml or left untreated. After normalization of protein content according to the protein assay, cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-TNF-R1 antibody overnight. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and Western blotting was performed with anti-IKKα, anti-IKKβ, and anti-IKKγ. Cell extract (1%) from each treated sample was used as a control for protein content (input). (B) Immunoprecipitates were also analyzed by Western blotting with anti-TRAF2, anti-TRADD, or anti-RIP. Numbers on the left are molecular masses in kilodaltons.

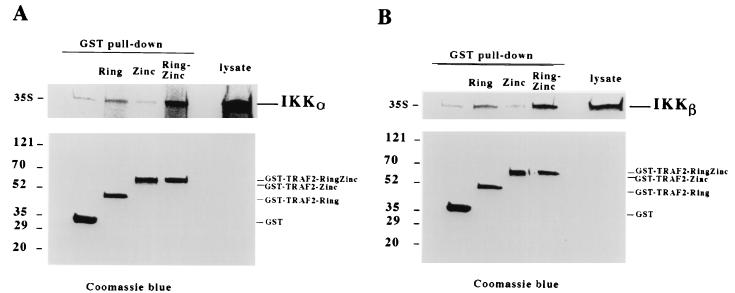

These immunoprecipitation experiments with cell extracts do not provide information about the biochemical basis for the interaction between IKK and TRAF2, although it has previously been shown that the RING domain of TRAF2 is essential for this interaction (5). It is important to know, for instance, whether IKK binds directly to TRAF2 and, if so, which IKK subunit mediates this interaction. To address these issues, we performed GST pull-down experiments using GST-TRAF2 fusion proteins and different IKK subunits. Since the TRAF domain of TRAF2 is dispensable for downstream signaling as long as the N-terminal domain is oligomerized (4), we used the GST fusion proteins containing the RING finger (amino acids 1 to 105), the zinc finger (76 to 282), and the RING and zinc fingers (1 to 225) of TRAF2, as described before (14). The three 35S-labeled IKK proteins were generated by in vitro translation with wheat germ lysate. In these experiments, GST alone was used as a negative control. As shown in Fig. 2A and B, both IKKα and IKKβ bound to the RING finger domain of TRAF2, whereas they did not interact with the zinc finger region. The presence of both the RING and zinc fingers strengthened the interaction between TRAF2 and IKKα or IKKβ (Fig. 2A and B). The amounts of the different GST-TRAF2 fusion proteins precipitated in these experiments are shown in Fig. 2A and B. In contrast, IKKγ did not show any considerable interaction with the different GST-TRAF2 proteins (Fig. 2C). These data suggested that either IKKα or IKKβ can bind directly to the RING domain of TRAF2.

FIG. 2.

IKKα and IKKβ interact with the RING domain of TRAF2. In vitro-translated IKKα (A), IKKβ (B), and IKKγ (C) were mixed with either GST or different GST-TRAF2 proteins (18), and then GST pull-down experiments were performed. Precipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE (top panels), and the coprecipitation of different IKK subunits was detected by autoradiography. The precipitation of different GST proteins was examined by Coomassie blue staining. The in vitro translation lysate for each subunit was used as a control. Numbers on the left are molecular masses in kilodaltons.

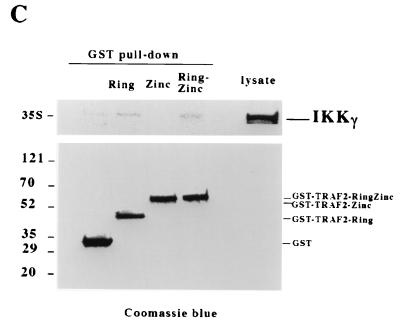

The leucine zipper domain of IKKα and IKKβ is essential for their interaction with TRAF2.

IKKα and IKKβ are related catalytic subunits with an overall identity of about 52% (12). Both contain an N-terminal kinase domain, a leucine zipper, and a C-terminal helix-loop-helix motif (12). In order to determine which region of these proteins was involved in their interaction with TRAF2, we generated expression constructs for different truncated IKKα and IKKβ proteins as shown in Fig. 3A and C. These constructs were then used to perform coimmunoprecipitation experiments. In these experiments, the different truncated IKKα or IKKβ proteins were ectopically expressed together with Flag-TRAF2 in HEK293 cells. After Flag-TRAF2 was immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag antibody, the immune complexes were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA or anti-Xpress antibody. As shown in Fig. 3B and D, the leucine zipper motif of IKKα or IKKβ is essential for interaction with TRAF2. The kinase domain and helix-loop-helix domain of IKKα or IKKβ failed to interact with TRAF2. These data indicate that IKKα and IKKβ interact with TRAF2 through their leucine zipper motifs. Alternatively, the interaction may require a dimer whose formation depends on the leucine zipper motif.

FIG. 3.

The leucine zipper domain of IKKα and IKKβ interacts with TRAF2. (A) Diagrams of different IKKα constructs used for the mapping of IKKα interaction with TRAF2. (B) HEK293 cells were cotransfected with 5 μg of Flag-TRAF2 and 5 μg of each of the IKKα expression plasmids [HA-IKKα, HA-IKKα(1–371), HA-IKKα(1–500), and Xpress-IKKα(500–745)]. Cells were collected 24 h after transfection, and cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag antibody overnight. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting was performed with anti-HA, anti-Xpress, or anti-Flag. Cell extract (4%) from each sample was used as a control (input). (C) Diagrams of different IKKβ constructs used for mapping IKKβ interaction with TRAF2. (D) HEK293 cells were cotransfected with 5 μg of Flag-TRAF2 and 5 μg of each of the IKKβ constructs [HA-IKKβ, HA-IKKβ(1–399), Xpress-IKKβ(399–577), and Xpress-IKKβ(399–756)]. Twenty four hours after transfection, immunoprecipitation experiments and Western blotting were performed as described for panel B. Numbers on the right are molecular masses in kilodaltons.

Either IKKα or IKKβ alone is sufficient to mediate the recruitment of IKK to the TNF-R1 complex in response to TNF.

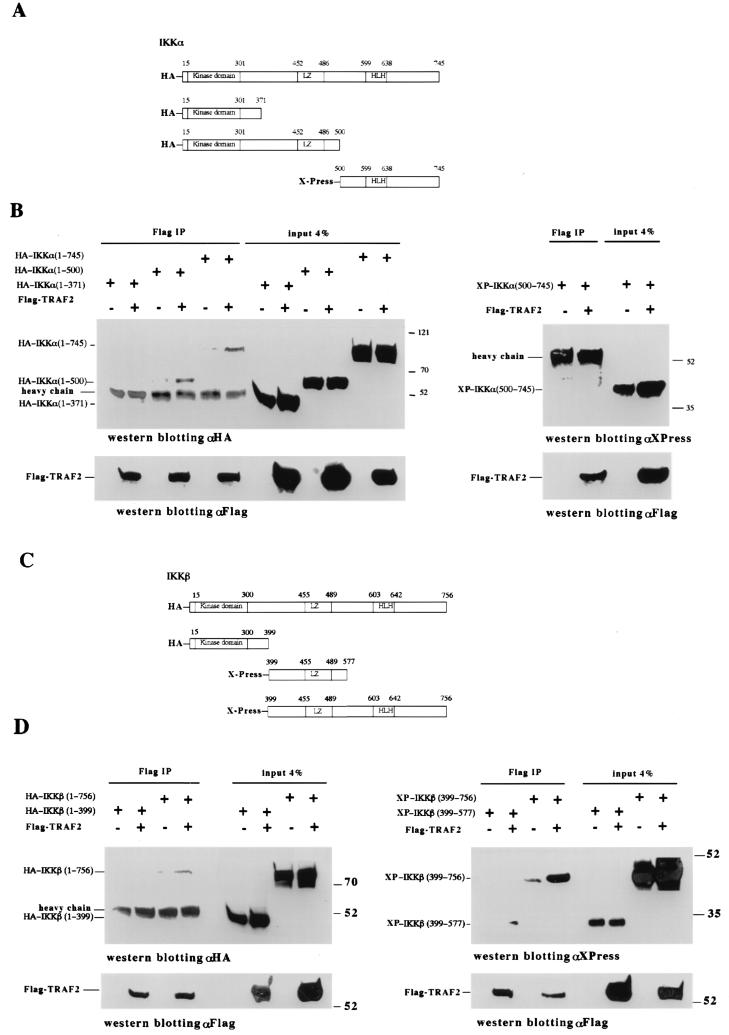

Since both IKKα and IKKβ can interact with TRAF2 efficiently, we next investigated which one of them is responsible for physiological IKK recruitment following TNF treatment. We addressed this question by performing TNF-R1 immunoprecipitation experiments with IKKα−/− and IKKβ−/− mouse fibroblasts (11, 18). As before, the immune complexes were analyzed by Western blotting sequentially with anti-IKKβ, anti-IKKγ, and anti-TRADD antibodies (Fig. 4A) or with anti-IKKα, anti-IKKγ, and anti-RIP (Fig. 4B). In the absence of either IKKα or IKKβ, IKK complexes containing IKKβ and IKKγ or IKKα and IKKγ, respectively, were still recruited to TNF-R1 upon TNF treatment with an efficiency similar to that in wt fibroblasts (Fig. 4A and B). As controls, the TNF-induced recruitment of TRADD and/or RIP to TNF-R1 in IKKα−/− and IKKβ−/− cells was also examined, and TRADD and RIP were found to be recruited to TNF-R1 normally (Fig. 4A and B). The protein expression levels of IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ in wt, IKKα−/−, and IKKβ−/− cells were measured by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 4C, the expression levels of each subunit, when present, are similar in all three types of cells.

FIG. 4.

IKKα or IKKβ alone is sufficient to mediate the interaction between IKK and TRAF2. (A) Cell extracts were prepared from wt and IKKα−/− fibroblasts either left untreated or treated with 40 ng of mTNF/ml. After normalization of protein content according to the protein assay, cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-TNF-R1 antibody overnight. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting was performed sequentially with anti-IKKα, anti-IKKβ, anti-IKKγ, anti-TRADD, and anti-RIP antibodies. Cell extract (1%) from each treated sample was used as a control for protein content (input). (B) Immunoprecipitation experiments were performed as described for panel A except that IKKβ−/−, instead of IKKα−/−, fibroblasts were used. Western blotting was performed sequentially with anti-IKKα, anti-IKKβ, anti-IKKγ, and anti-RIP. (C) The same amount of cell extract from wt, IKKα−/−, or IKKβ−/− cells was used for measuring the expression of IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ by Western blotting. (D) Cell extracts were prepared from IKKα−/− and IKKβ−/− fibroblasts either treated with 40 ng of mTNF/ml or left untreated. After normalization of protein content according to the protein assay, cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-IKKγ antibody overnight. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting was performed with anti-IKKβ in IKKα−/− cells and anti-IKKα in IKKβ−/− cells. Cell extract (1%) from each treated sample was used as a control for protein content (input). Numbers on the left are molecular masses in kilodaltons.

Since IKKγ is normally complexed with both IKKα and IKKβ in wt cells (18), we wanted to confirm that IKKγ still forms a complex with IKKβ or IKKα in IKKα−/− or IKKβ−/− cells, respectively. To accomplish this, we performed immunoprecipitation experiments with anti-IKKγ antibody in IKKα−/− and IKKβ−/− cells. As shown in Fig. 4D, IKKγ efficiently interacts with IKKβ in the absence of IKKα and with IKKα in the absence of IKKβ. TNF treatment had no effect on these interactions. These results suggest that either IKKα or IKKβ alone together with IKKγ is sufficient for recruitment to TNF-R1.

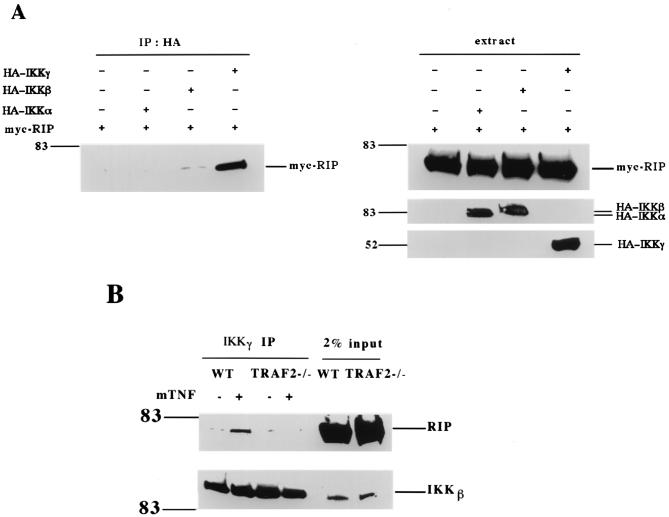

The TNF-induced interaction between RIP and IKKγ requires TRAF2.

Recently, IKKγ has been found to interact with RIP in response to TNF, therefore, it has been proposed that IKKγ mediates IKK recruitment to TNF-R1 (42). However, the results shown in Fig. 1 and previous studies (5) indicated that TRAF2, not RIP, is essential for bringing IKK to TNF-R1. Since the interaction between RIP and IKKγ was observed in the presence of TRAF2 (42), we investigated whether TRAF2 is required for this interaction. Consistent with a previous report (42), when RIP was overexpressed with either IKKα, IKKβ, or IKKγ it was coprecipitated only with IKKγ (Fig. 5A). To test whether RIP interacts with IKKγ in the absence of TRAF2 in response to TNF treatment, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments in wt and TRAF2−/− cells. As shown in Fig. 5B, RIP was coprecipitated with IKKγ in TNF-treated wt cells but not in TNF-treated TRAF2−/− cells. These results suggest that TRAF2 is necessary for the interaction of RIP with IKKγ under physiological conditions.

FIG. 5.

TRAF2 is required for the TNF-induced interaction between IKKγ and RIP. (A) HEK293 cells were cotransfected with 5 μg of Myc-RIP and 5 μg of each of the HA-tagged IKK subunits. Cells were collected 24 hours after transfection, and cell extracts were used for immunoprecipitation experiments with anti-HA antibody. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting was performed with anti-Myc and anti-HA. (B) Immunoprecipitation experiments were performed with cell extracts prepared from wt and TRAF2−/− fibroblasts with or-without mTNF (40 ng/ml) treatment. After normalization of protein content according to the protein assay, cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-IKKγ antibody overnight. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting was performed with anti-RIP or anti-IKKβ. Cell extract (2%) from each treated sample was used as a control for protein content (input). Numbers on the left are molecular masses in kilodaltons.

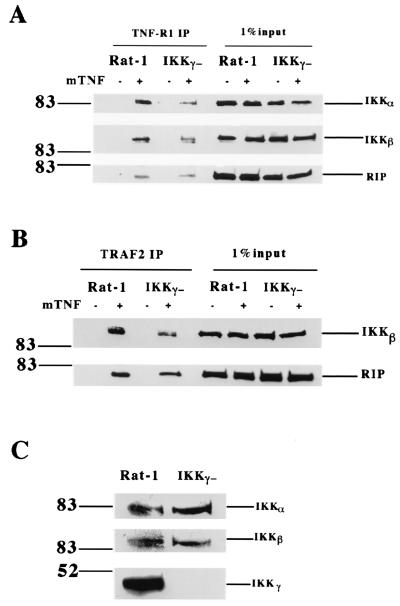

IKKγ is not essential for TNF-induced IKK recruitment to TNF-R1.

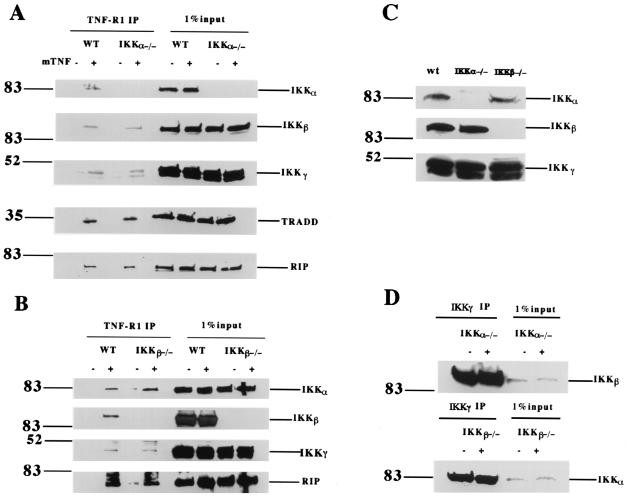

To further understand the role of IKKγ in IKK recruitment, we tested whether IKK can be recruited to TNF-R1 in the absence of IKKγ. To do so, we performed immunoprecipitation experiments with anti-TNF-R1 antibody in Rat-1 and 5R fibroblasts, the latter being IKKγ deficient (37). In these experiments TNF-R1 complexes were immunoprecipitated from either untreated or TNF-treated Rat-1 and 5R cells and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting sequentially with anti-IKKα, anti-IKKβ, and anti-RIP antibodies. As shown in Fig. 6A, both IKKα and IKKβ were efficiently recruited to TNF-R1 in 5R cells following TNF treatment. However, the levels of IKKα and IKKβ recruitment in 5R cells were slightly decreased compared to that in Rat-1 cells. As a control, the TNF-induced recruitment of RIP was examined and was found to be similar in both types of cells (Fig. 6A). These results indicated that IKKγ was dispensable for the TNF-induced recruitment of IKK to TNF-R1 although its presence enhances the efficiency of IKK recruitment. This conclusion was further confirmed by the immunoprecipitation experiments with anti-TRAF2 antibody (Fig. 6B). The expression levels of IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ in Rat-1 and 5R cells were examined by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 6C, IKKα and IKKβ were expressed similarly in both cell types. Thus, it is IKKα or IKKβ but not IKKγ that plays an essential role in the recruitment of IKK to the TNF-R1 signaling complex.

FIG. 6.

IKKγ is not essential for TNF-induced IKK recruitment to TNF-R1. (A) Immunoprecipitation experiments were performed with cell extracts prepared from wt Rat-1 and 5R cells with or without mTNF (40 ng/ml) treatment. After normalization of protein content according to the protein assay, cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-TNF-R1 antibody overnight. Immunoprecipitants were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting was performed sequentially with anti-IKKα, anti-IKKβ, and anti-RIP antibodies. Cell extract (1%) from each treated sample was used as a control for protein content (input). (B) Similar experiments were performed as described for panel A except that anti-TRAF2 antibody was used for immunoprecipitation. Western blotting was performed with anti-IKKβ and anti-RIP antibodies. (C) The same amount of cell extract from Rat-1 or 5R cells was applied to SDS-PAGE for Western blotting with anti-IKKα, anti-IKKβ, and anti-IKKγ antibodies. Numbers on the left are molecular masses in kilodaltons.

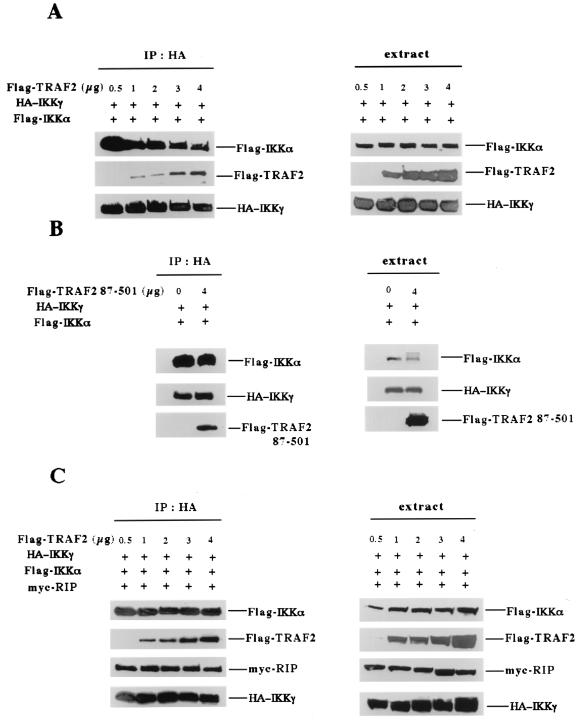

RIP plays a role in stabilizing IKK.

Since the RIP-IKKγ interaction is not essential for TNF-induced IKK recruitment, we next investigated the possible function of the RIP-IKKγ interaction in TNF-induced IKK activation. According to the results shown in Fig. 1A, the amount of recruited IKKγ, but not of IKKα or IKKβ, was decreased in RIP−/− cells in comparison with amounts in wt cells. Because IKKγ normally forms a complex with IKKα and IKKβ in RIP−/− cells (data not shown), one explanation for this observation is that the TNF-induced TRAF2-IKK interaction interfered with the binding of IKKγ to IKKα and IKKβ. To test this possibility, we examined whether the presence of TRAF2 disrupts the IKKα-IKKγ interaction. In these experiments, Flag-IKKα and HA-IKKγ were ectopically coexpressed with increasing amounts of Flag-TRAF2. After HA-IKKγ was immunoprecipitated, the precipitates were analyzed by Western blotting for Flag-IKKα, Flag-TRAF2, and HA-IKKγ. As shown in Fig. 7A, in the absence of TRAF2, IKKα and IKKγ interacted nicely, and this interaction was gradually disrupted as the expression level of TRAF2 was increased. Similar amounts of HA-IKKγ were immunoprecipitated in these experiments and some of the coexpressed Flag-TRAF2 was also detected. The expression levels of Flag-IKKα, Flag-TRAF2, and HA-IKKγ are shown in Fig. 7A. When Flag-TRAF2(87–501), which lacks the RING finger domain and is thus incapable of recruiting IKK to the TNF-R1 (5), was used in a similar experiment, it had no effect on the interaction between IKKα and IKKγ (Fig. 7B). The expression levels of Flag-IKKα, Flag-TRAF2(87–501), and IKKγ were examined as shown in Fig. 7B. These data indicate that the interaction of TRAF2 and IKKα had some interfering effect on the interaction between IKKα and IKKγ.

FIG. 7.

RIP is required to stabilize the interaction between IKKα and IKKγ when IKKα binds to TRAF2. (A) HEK293 cells were cotransfected with 3 μg of Flag-IKKα, 3 μg of HA-IKKγ, and increasing amounts of Flag-TRAF2 as shown. After 24 h, cell extracts were collected and used for immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting was performed with anti-Flag antibody and anti-HA. (B) HEK293 cells were cotransfected with 3 μg of Flag-IKKα, 3 μg of HA-IKKγ, and 0 or 4 μg of Flag-TRAF2(87–501) as shown. Then immunoprecipitation and Western blotting were performed as described for panel A. (C) HEK293 cells were cotransfected with 3 μg of Flag-IKKα, 2 μg of HA-IKKγ, 2 μg of Myc-RIP, and increasing amounts of Flag-TRAF2 as shown. Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting were performed as described for panel A except that anti-Myc antibody was used to detect Myc-RIP expression.

Because RIP can also interact with TRAF2 (10), when RIP is recruited to the TNF-R1 complex, RIP may stabilize the IKK complex by simultaneously interacting with both TRAF2 and IKKγ. If this is true, the presence of RIP will counteract the interfering effect of TRAF2 on the interaction between IKKα and IKKγ. To test this hypothesis, we performed the coimmunoprecipitation experiments as described in the legend to Fig. 7A except with the addition of RIP. As shown in Fig. 7C, the expression of RIP in these experiments completely prevented the disruptive effect of TRAF2 and restored the interaction of IKKα and IKKγ. The presence of Flag-TRAF2, Myc-RIP, and HA-IKKγ was also examined (Fig. 7C). The expression of IKKα, IKKγ, TRAF2, and RIP was detected by Western blotting (Fig. 7C). These results implied that one possible function of RIP in TNF-induced IKK activation is to stabilize IKK after its recruitment to the TNF-R1 complex.

DISCUSSION

The regulation of TNF-induced NF-κB activation is complex, and one of the key steps in this process is the activation of IKK (12). To be activated by TNF, IKK needs to be quickly recruited to the TNF-R1 complex following TNF treatment (5, 42). Recently it was reported that TRAF2 is essential for TNF-induced IKK recruitment (5). However, because RIP has been found to interact with IKKγ in response to TNF, it has been suggested that the RIP-IKKγ interaction is accountable for bringing IKK to TNF-R1 (42). In this study, we demonstrated that the two catalytic subunits of IKK, IKKα and IKKβ, interact with TRAF2 to mediate the TNF-induced IKK recruitment to TNF-R1 and that the regulatory subunit of IKK, IKKγ, is not essential for this recruiting process. Using TRAF2−/− fibroblasts, we also showed that the RIP-IKKγ interaction is TRAF2 dependent. Moreover, we proposed that one possible function of RIP in TNF-induced IKK activation is to stabilize the IKKγ subunit in the IKK complex.

IKKα and IKKβ are highly homologous and have the same structural features, including kinase, leucine zipper, and helix-loop-helix motifs (12). The helix-loop-helix motif of IKKα and IKKβ is thought to be involved in regulating their kinase activity, while the leucine zipper motif is essential for the dimerization of IKKα and IKKβ and their kinase activity (12). Although both IKKα and IKKβ are capable of phosphorylating IκB, IKKβ apparently plays a major role in TNF-induced NF-κB activation (11, 18, 26, 34, 36). In this study we identified another function of IKKα and IKKβ, the mediation of the interaction between IKK and TRAF2 in response to TNF. We found that IKKα and IKKβ bind to TRAF2 equally well. It appears that the interaction between IKK and TRAF2 requires the leucine zipper motif of IKKα or IKKβ and the RING finger domain of TRAF2. Therefore, besides being required for the dimerization of IKKα and IKKβ and for IKK kinase activity, the leucine zipper motif of IKKα and IKKβ is also essential for IKK to interact with its upstream effector TRAF2 in response to TNF. The studies with IKKα and IKKβ knockout mice indicated that IKKβ is the major kinase in TNF-induced NF-κB activation, since the deletion of IKKα had only a minor effect on this process (11, 15, 16, 18, 34). According to our results, either IKKα or IKKβ alone was capable of mediating TNF-induced IKK recruitment to TNF-R1 (Fig. 4). Because effector molecules, including TRADD, RIP, and TRAF2, were recruited to TNF-R1 normally in IKKα−/− and IKKβ−/− cells, it seems that the varied effects of the deletion of IKKα or IKKβ on TNF-induced NF-κB activation are due solely to the difference in the kinase activity of IKKα and IKKβ in terms of IκB phosphorylation.

The third component of IKK is IKKγ, a regulatory subunit (29, 37). It is known that IKKγ is required for elevating IKK activity by a variety of stimuli and that it binds to the C termini of IKKα and IKKβ to form the IKK complex (12). In response to TNF treatment, IKKγ interacts with RIP (42). In our study, we found that the interaction between IKKγ and RIP is not essential for IKK recruitment to TNF-R1, because IKKα and IKKβ were still recruited efficiently in RIP−/− cells. More importantly, the interaction between IKKγ and RIP is dependent on the recruitment of the IKK complex to TRAF2. Therefore, the critical role of IKKγ in TNF-induced IKK activation is not to mediate IKK recruitment. We also found that when IKK bound to TRAF2 in response to TNF, the interaction between IKK and TRAF2 destabilized the IKK complex by weakening the binding of IKKγ to the other two subunits. Although IKKγ and TRAF2 bind to different regions of IKKα and IKKβ, it appears that the binding of TRAF2 to IKKα and IKKβ interferes with the interaction between IKKγ and the two catalytic subunits. To completely retain IKKγ in the IKK complex after it is recruited to TNF-R1, IKKγ needs to interact wit RIP. The presence of RIP and IKKγ may enhance the recruitment of IKK to TNF-R1. But since both RIP and IKKγ are essential for TNF-induced IKK activation, their major function in this process must be to activate IKK, although the mechanism is still not clear. It is possible that the RIP-IKKγ interaction results in conformational changes in IKK and, in turn, leads to the autophosphorylation and subsequent activation of IKK. Another possibility is that RIP is required for recruiting the IKK kinase, most likely a mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase, and then the interaction between RIP and IKKγ primes the IKK kinase to activate IKK. Although the study of the kinetics of TNF-induced IKK activation favors the latter possibility (5), the identification of the putative IKK kinase is a critical step in fully understanding the mechanism of TNF-induced IKK activation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank W.-C. Yeh and T. W. Mak for TRAF2−/− fibroblasts, M. Kelliher for RIP−/− fibroblasts, and U. Siebenlist for GST-TRAF2 constructs. We are grateful to Joseph Lewis for his assistance in manuscript preparation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baeuerle P A, Baltimore D. NF-κB: ten years after. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldwin A S. The NF-κB and IκB proteins—new discoveries and insights. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:649–683. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes P J, Karin M. Nuclear factor-κB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1066–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baud V, Liu Z G, Bennett B, Suzuki N, Xia Y, Karin M. Signaling by proinflammatory cytokines: oligomerization of TRAF2 and TRAF6 is sufficient for JNK and IKK activation and target gene induction via an amino-terminal effector domain. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1297–1308. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devin A, Cook A, Lin Y, Rodriguez Y, Kelliher M, Liu Z G. The distinct roles of TRAF2 and RIP in IKK activation by TNF-R1: TRAF2 recruits IKK to TNF-R1 while RIP mediates IKK activation. Immunity. 2000;12:419–429. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiDonato J A, Hayakawa M, Rothwarf D M, Zandi E, Karin M. A cytokine-responsive IκB kinase that activates the transcription factor NF-κB. Nature. 1997;388:548–554. doi: 10.1038/41493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harlow E, Lane D. Using antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1999. pp. 323–325. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu H, Xiong J, Goeddel D V. The TNF receptor 1-associated protein TRADD signals cell death and NF-κB activation. Cell. 1995;81:495–504. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu H, Shu H B, Pan M P, Goeddel D V. TRADD-TRAF2 and TRADD-FADD interactions define two distinct TNF receptor-1 signal transduction pathways. Cell. 1996;84:299–308. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80984-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu H, Huang J, Shu H B, Baichwal V, Goeddel D V. TNF-dependent recruitment of the protein kinase RIP to the TNF receptor-1 signaling complex. Immunity. 1996;4:387–396. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu Y, Baud V, Delhase M, Zhang P, Deerinck T, Ellisman M, Johnson R, Karin M. Abnormal morphogenesis but intact IKK activation in mice lacking the IKK alpha subunit of IkappaB kinase. Science. 1999;284:316–320. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karin M. The beginning of the end: IκB kinase (IKK) and NF-κB activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27339–27342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelliher M A, Grimm S, Ishida Y, Kuo F, Stanger B Z, Leder P. The death domain kinase RIP mediates the TNF-induced NF-κB signal. Immunity. 1998;8:297–303. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80535-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leonardi A, Ellinger-Ziegelbauer H, Franzoso G, Brown K, Siebenlist U. Physical and functional interaction of filamin (actin-binding protein-280) and tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:271–278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Q, Van Antwerp D, Mercurio F, Lee K F, Verma I M. Severe liver degeneration in mice lacking the IkappaB kinase 2 gene. Science. 1999;284:321–325. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Q, Estepa G, Memet S, Israel A, Verma I M. Complete lack of NF-kappaB activity in IKK1 and IKK2 double-deficient mice: additional defect in neurulation. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1729–1733. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Q, Lu Q, Hwang J Y, Buscher D, Lee K F, Izpisua-Belmonte J C, Verma I M. IKK1-deficient mice exhibit abnormal development of skin and skeleton. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1322–1328. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Z W, Chu W, Hu Y, Delhase M, Deerinck T, Ellisman M, Johnson R, Karin M. The IKKbeta subunit of IκB kinase (IKK) is essential for nuclear factor κB activation and prevention of apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1839–1845. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin Y, Devin A, Rodriguez Y, Liu Z G. Cleavage of the death domain kinase RIP by caspase-8 prompts TNF-induced apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2514–2526. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Z G, Hsu H, Goeddel D V, Karin M. Dissection of TNF receptor 1 effector functions: JNK activation is not linked to apoptosis while NF-κB activation prevents cell death. Cell. 1996;87:565–576. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makris C, Godfrey V L, Krahn-Senftleben G, Takahashi T, Roberts J L, Schwarz T, Feng L, Johnson R S, Karin M. Female mice heterozygous for IKK gamma/NEMO deficiencies develop a dermatopathy similar to the human X-linked disorder incontinentia pigmenti. Mol Cell. 2000;5:969–979. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80262-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.May M J, D'Acquisto F, Madge L A, Glockner J, Pober J S, Ghosh S. Selective inhibition of NF-kappaB activation by a peptide that blocks the interaction of NEMO with the IkappaB kinase complex. Science. 2000;289:1550–1554. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mercurio F, Zhu H, Murray B W, Shevchenko A, Bennett B L, Li J, Young D B, Barbosa M, Mann M, Manning A, Rao A. IKK-1 and IKK-2: cytokine-activated IκB kinases essential for NF-κB activation. Science. 1997;278:860–866. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mercurio F, Manning A M. Multiple signals converging on NF-κB Curr. Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:226–232. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)80030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Mahony A, Lin X, Geleziunas R, Greene W C. Activation of the heterodimeric IκB kinase α (IKKα)-IKKβ complex is directional: IKKα regulates IKKβ under both basal and stimulated conditions. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1170–1178. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1170-1178.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Regnier C H, Song H Y, Gao X, Goeddel D V, Cao Z, Rothe M. Identification and characterization of an IkappaB kinase. Cell. 1997;90:373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80344-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothe M, Wong S C, Henzel W J, Goeddel D V. A novel family of putative signal transducers associated with the cytoplasmic domain of the 75 kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. Cell. 1994;78:681–692. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothe M, Sarma V, Dixit V M, Goeddel D V. TRAF2-mediated activation of NF-κB by TNF receptor 2 and CD40. Science. 1995;269:1424–1427. doi: 10.1126/science.7544915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rothwarf D M, Zandi E, Natoli G, Karin M. IKK-gamma is an essential regulatory subunit of the IκB kinase complex. Nature. 1998;395:297–300. doi: 10.1038/26261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudolph D, Yeh W C, Wakeham A, Rudolph B, Nallainathan D, Potter J, Elia A J, Mak T W. Severe liver degeneration and lack of NF-κB activation in NEMO/IKKgamma-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 2000;14:854–862. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt-Supprian M, Bloch W, Courtois G, Addicks K, Israel A, Rajewsky K, Pasparakis M. NEMO/IKK gamma-deficient mice model incontinentia pigmenti. Mol Cell. 2000;5:981–992. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siebenlist U, Franzoso G, Brown K. Structure, regulation and function of NF-κB. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1994;10:405–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.10.110194.002201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanger B Z, Leder P, Lee T H, Kim E, Seed B. RIP: a novel protein containing a death domain that interacts with Fas/APO-1 (CD95) in yeast and causes cell death. Cell. 1995;81:513–523. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka M, Fuentes M E, Yamaguchi K, Durnin M H, Dalrymple S A, Hardy K L, Goeddel D V. Embryonic lethality, liver degeneration, and impaired NF-κB activation in IKK-β-deficient mice. Immunity. 1999;10:421–429. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ting A T, Pimentel-Muinos F X, Seed B. RIP mediates tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 activation of NF-κB but not Fas/APO-1-initiated apoptosis. EMBO J. 1996;15:6189–6196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woronicz J D, Gao X, Cao Z, Rothe M, Goeddel D V. IkappaB kinase-beta: NF-kappaB activation and complex formation with IkappaB kinase-alpha and NIK. Science. 1997;278:866–869. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamaoka S, Courtois G, Bessia C, Whiteside S T, Weil R, Agou F, Kirk H E, Kay R J, Israel A. Complementation cloning of NEMO, a component of the IκB kinase complex essential for NF-κB activation. Cell. 1998;93:1231–1240. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81466-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yeh W C, Shahinian A, Speiser D, Kraunus J, Billia F, Wakeham A, de la Pompa J L, Ferrick D, Hum B, Iscove N, Ohashi P, Rothe M, Goeddel D V, Mak T W. Early lethality, functional NF-κB activation, and increased sensitivity to TNF-induced cell death in TRAF2-deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;7:715–725. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zandi E, Rothwarf D M, Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Karin M. The IκB kinase complex (IKK) contains two kinase subunits, IKKalpha and IKKbeta, necessary for IκB phosphorylation and NF-κB activation. Cell. 1997;91:243–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zandi E, Chen Y, Karin M. Direct phosphorylation of IkappaB by IKKalpha and IKKbeta: discrimination between free and NF-kappaB-bound substrate. Science. 1998;281:1360–1363. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zandi E, Karin M. Bridging the gap: composition, regulation, and physiological function of the IκB kinase complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4547–4551. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.4547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang S Q, Kovalenko A, Cantarella G, Wallach D. Recruitment of the IKK signalosome to the p55 TNF receptor: RIP and A20 bind to NEMO (IKKγ) upon receptor stimulation. Immunity. 2000;12:301–311. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80183-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]